Submitted:

16 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Hartree-Fock Approximation

2.2. Role of Quantum and Thermal Fluctuations

3. Experimental Foundations

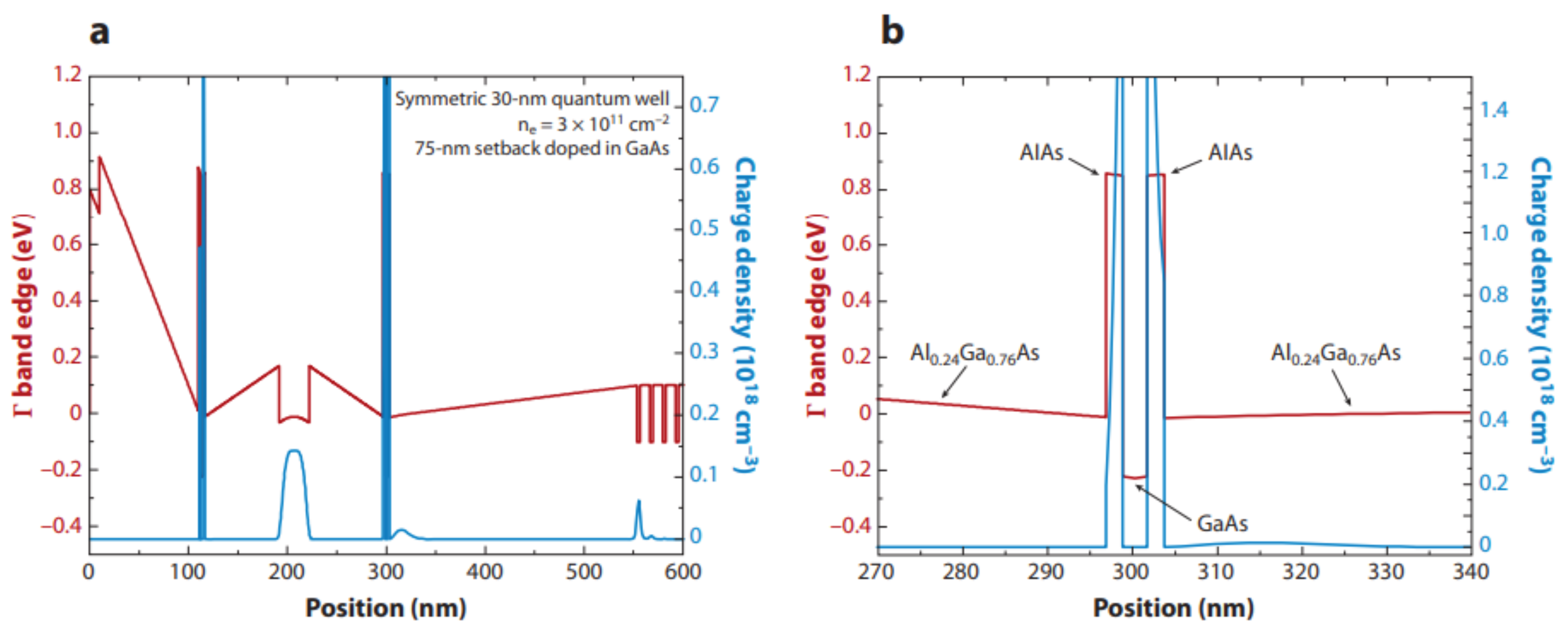

3.1. Two-Dimensional Electron Systems in GaAs/AlGaAs Heterostructures

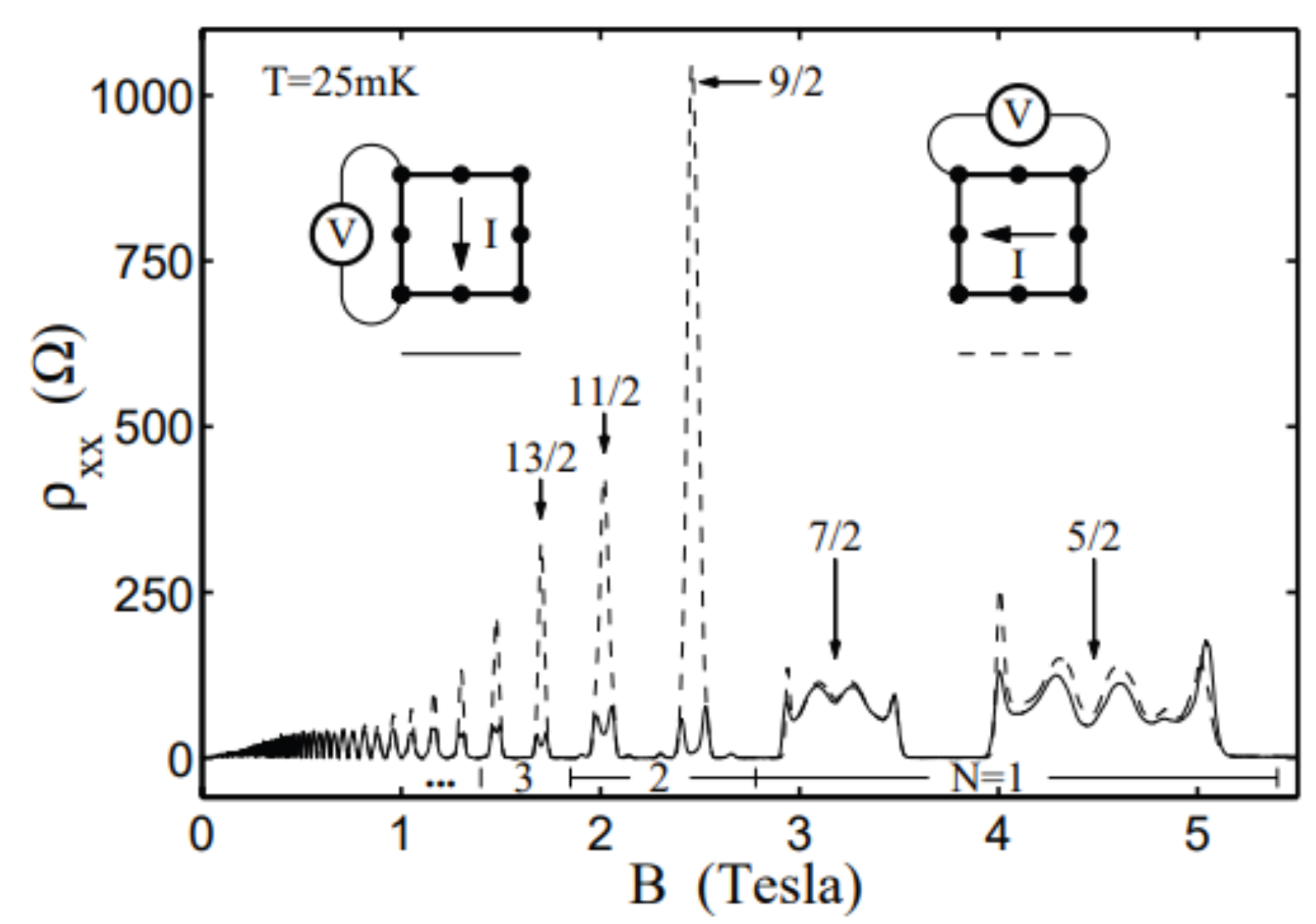

3.2. Stripe Phases and Transport Anisotropy

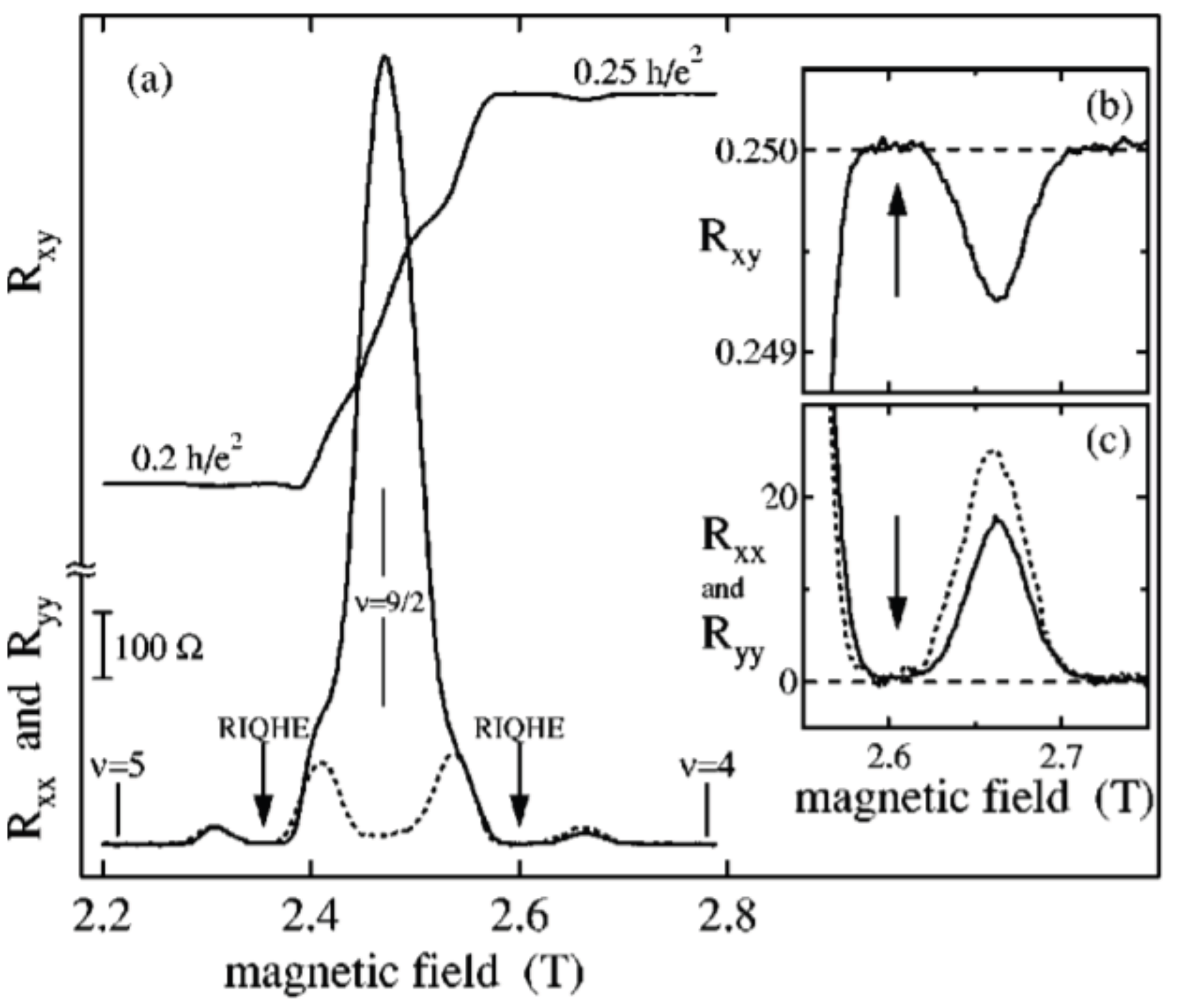

3.3. Reentrant Integer Quantum Hall Phases

4. Emerging Phenomena and Open Questions

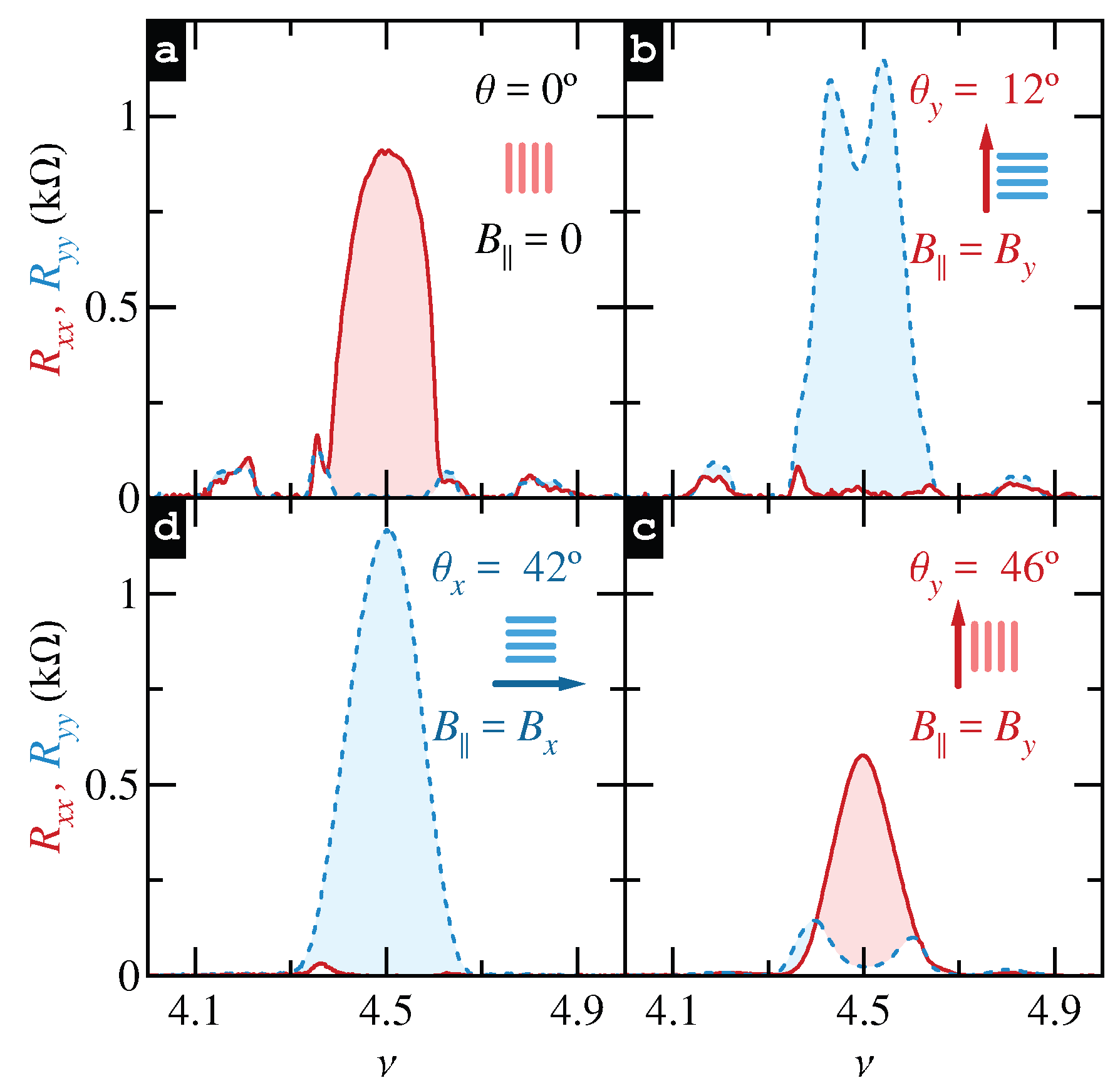

4.1. Stripe Reorientation Under In-Plan Magnetic Field

4.2. Possible Electronic Liquid Crystalline States

4.3. Anomalous Nematic States

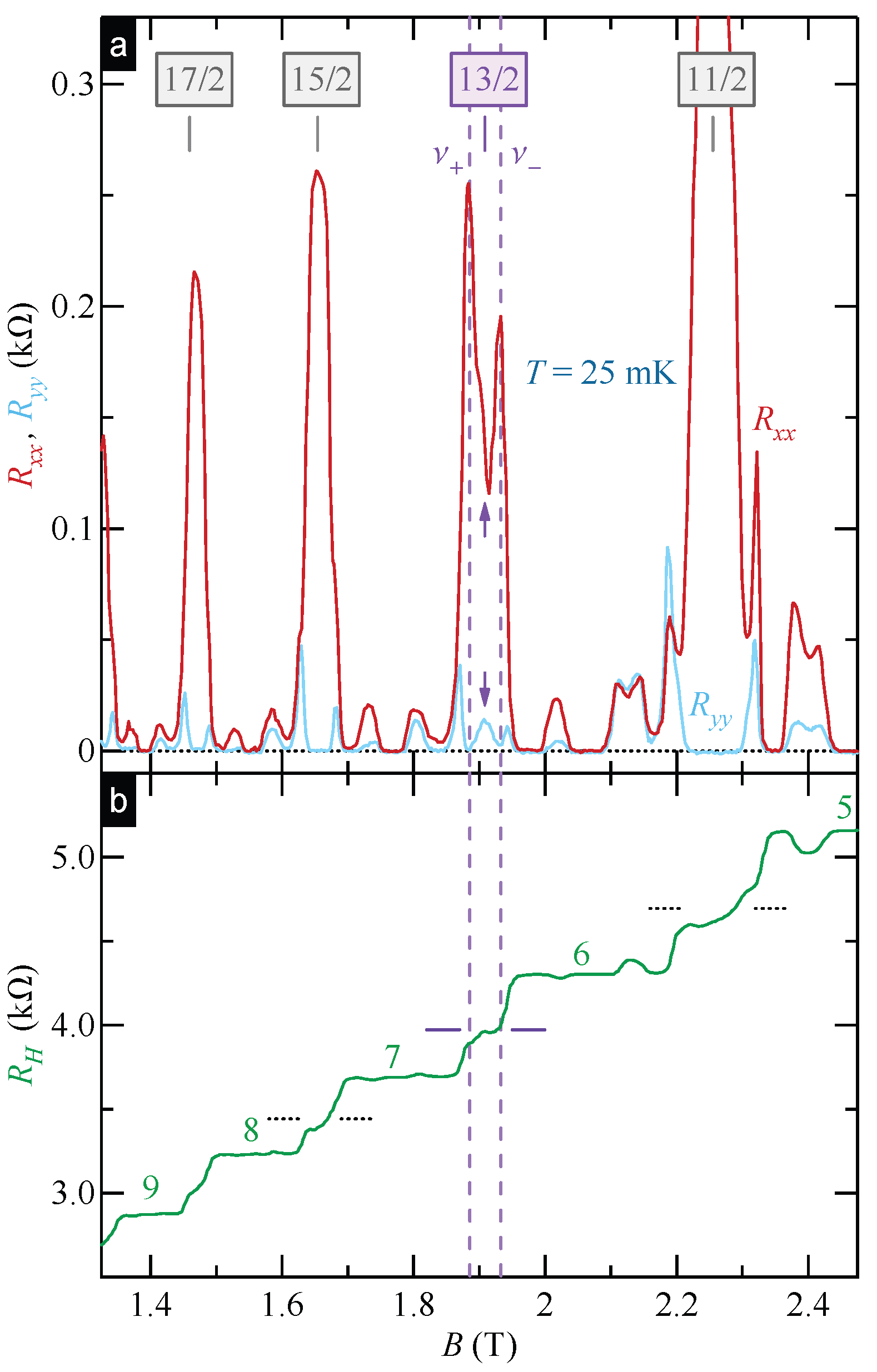

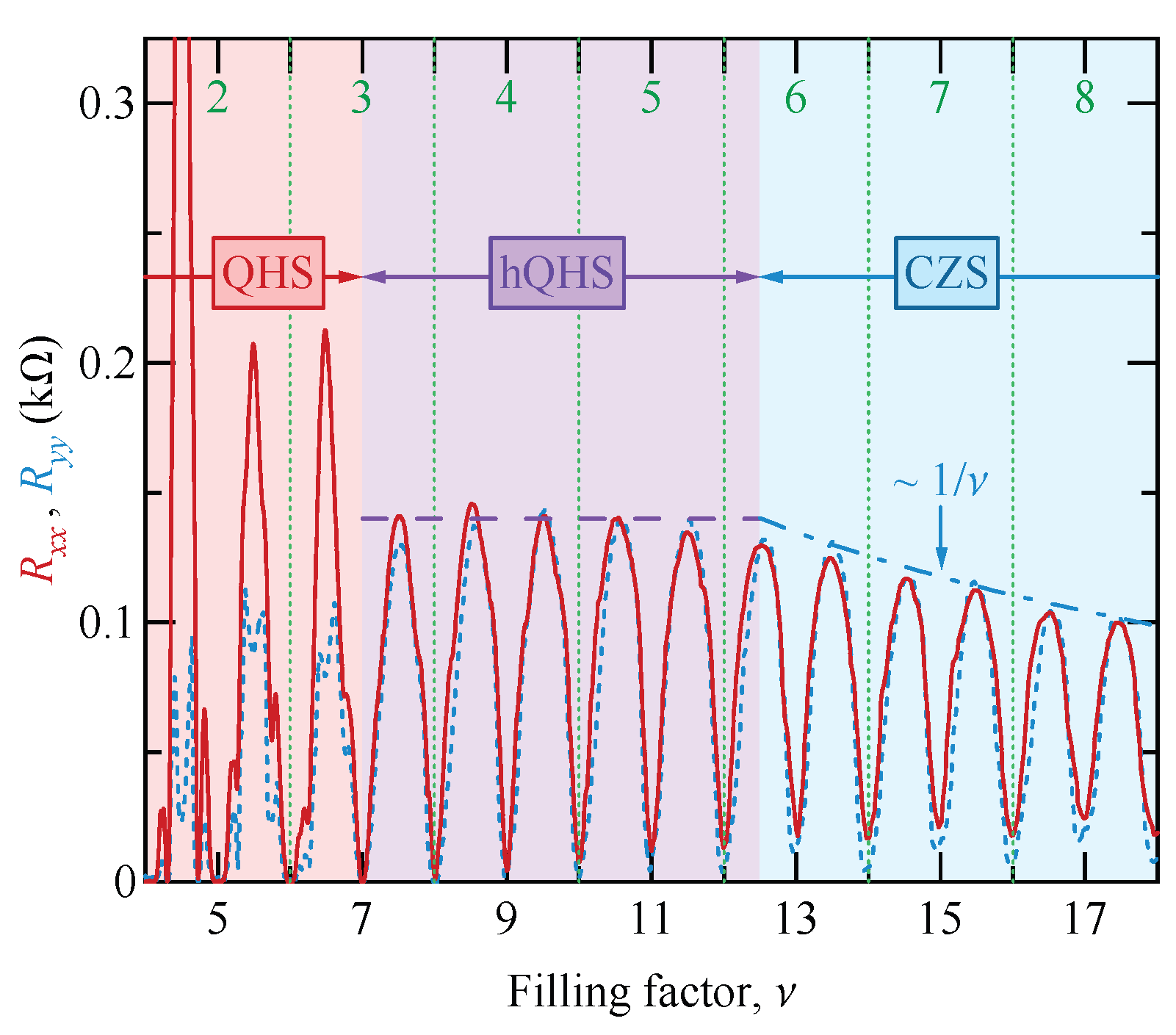

4.4. Hidden Quantum Hall Stripes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2DES | Two-dimensional electron systems |

| QHS | Quantum Hall stripes |

| hQHS | Hidden quantum Hall stripes |

References

- von Klitzing, K.; Dorda, G.; Pepper, M. New Method for High-Accuracy Determination of the Fine-Structure Constant Based on Quantized Hall Resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, D.C.; Stormer, H.L.; Gossard, A.C. Two-Dimensional Magnetotransport in the Extreme Quantum Limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, M.P.; Cooper, K.B.; Eisenstein, J.P.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Evidence for an Anisotropic State of Two-Dimensional Electrons in High Landau Levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.R.; Tsui, D.C.; Stormer, H.L.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; Baldwin, K.W.; West, K.W. Strongly anisotropic transport in higher two-dimensional Landau levels. Solid State Commun. 1999, 109, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, J.P.; MacDonald, A.H. Bose–Einstein condensation of excitons in bilayer electron systems. Nature (London) 2004, 432, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradkin, E.; Kivelson, S.A.; Lawler, M.J.; Eisenstein, J.P.; Mackenzie, A.P. Nematic Fermi Fluids in Condensed Matter Physics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2010, 1, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, A.A.; Fogler, M.M.; Shklovskii, B.I. Charge density wave in two-dimensional electron liquid in weak magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 76, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogler, M.M.; Koulakov, A.A.; Shklovskii, B.I. Ground state of a two-dimensional electron liquid in a weak magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradkin, E.; Kivelson, S.A. Liquid-crystal phases of quantum Hall systems. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, C.; Dorsey, A.T. Disclination unbinding transition in quantum Hall liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 115312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, M.; Nayak, C.; Kachru, S. Isotropic to anisotropic transition in a fractional quantum Hall state. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 085102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertig, H.A. Unlocking Transition for Modulated Surfaces and Quantum Hall Stripes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 3693–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.M.; Ye, P.D.; Engel, L.W.; Tsui, D.C.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Microwave Resonance of the Bubble Phases in 1/4 and 3/4 Filled High Landau Levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 136804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lewis, R.M.; Engel, L.W.; Tsui, D.C.; Ye, P.D.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Microwave Resonance of the 2D Wigner Crystal around Integer Landau Fillings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 016801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samkharadze, N.; Schreiber, K.A.; Gardner, G.C.; Manfra, M.J.; Fradkin, E.; Csathy, G.A. Observation of a transition from a topologically ordered to a spontaneously broken symmetry phase. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koduvayur, S.P.; Lyanda-Geller, Y.; Khlebnikov, S.; Csathy, G.; Manfra, M.J.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W.; Rokhinson, L.P. Effect of Strain on Stripe Phases in the Quantum Hall Regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 016804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zudov, M.A.; Watson, J.D.; Gardner, G.C.; Manfra, M.J. Reorientation of quantum Hall stripes within a partially filled Landau level. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 121404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zudov, M.A.; Watson, J.D.; Gardner, G.C.; Manfra, M.J. Evidence for a new symmetry breaking mechanism reorienting quantum Hall nematics. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 121411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zudov, M.A.; Qian, Q.; Watson, G.C.; Manfra, M.J. Reorientation of stripe phases by in-plane magnetic fields in a tunable-density two-dimensional electron gas. submitted 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Q.; Nakamura, J.; Fallahi, S.; Gardner, G.C.; Manfra, M.J. Possible nematic to smectic phase transition in a two-dimensional electron gas at half-filling. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Shi, Q.; Zudov, M.A.; Gardner, G.C.; Watson, J.D.; Manfra, M.J.; Baldwin, K.W.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Anomalous Nematic States in High Half-Filled Landau Levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 067601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Huang, Y.; Shi, Q.; Shklovskii, B.I.; Zudov, M.A.; Gardner, G.C.; Manfra, M.J. Hidden Quantum Hall Stripes in AlxGa1-xAs/Al0.24Ga0.76As Quantum Wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 236803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Shi, Q.; Zudov, M.A.; Gardner, G.C.; Watson, J.D.; Manfra, M.J.; Baldwin, K.W.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Anomalous nematic state to stripe phase transition driven by in-plane magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, L081301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezayi, E.H.; Haldane, F.D.M.; Yang, K. Charge-Density-Wave Ordering in Half-Filled High Landau Levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, N.; Yoshioka, D. Ground-state phase diagram of two-dimensional electrons in higher Landau levels. Physical Review Letters 2001, 86, 5755–5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, N.; Yoshioka, D. Stripe and bubble phases in the quantum Hall regime. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 2003, 72, 664–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivelson, S.A.; Fradkin, E.; Emery, V.J. Electronic liquid-crystal phases of a doped Mott insulator. Nature 1998, 393, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metlitski, M.A.; Sachdev, S. Quantum phase transitions of metals in two spatial dimensions. I. Ising-nematic order. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 075127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Fregoso, B.M.; Lawler, M.J.; Fradkin, E. Fluctuating Stripes in Strongly Correlated Electron Systems and the Nematic–Smectic Quantum Phase Transition. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0805.3526 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogler, M.M.; Huse, D.A. Collective pinning of charge-density waves in high Landau levels. Physical Review B 2000, 62, 7553–7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandkishore, R.; Huse, D.A.; Sondhi, S.L. Rare region effects dominate weakly disordered three-dimensional Dirac points. Physical Review B 2012, 86, 045128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.H.; Fisher, M.P.A. Quantum theory of quantum Hall smectics. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 5724–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanin, D.A.; Levitov, L.S. Transport in strongly correlated two-dimensional electron fluids. Physical Review B 2010, 82, 035428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.B.; Lilly, M.P.; Eisenstein, J.P.; Jungwirth, T.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. An Investigation of Orientational Symmetry-Breaking Mechanisms in High Landau Levels. Solid State Commun. 2001, 119, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöll, E. Nonlinear spatio-temporal dynamics and chaos in semiconductors; Cambridge University: Cambridge, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fogler, M.M. Dynamics of disordered stripe phases in high Landau levels. Physical Review B 2002, 66, 153304. [Google Scholar]

- Oganesyan, V.; Kivelson, S.A.; Fradkin, E. Quantum Theory of a Nematic Fermi Fluid. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 195109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, J.; et al. Asymptotic Pomeranchuk instability of Fermi liquids in half-filled Landau levels. Scientific Reports 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, K.J.; Hey, R.; Kostial, H.; Klann, R.; Ploog, K. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 4616. [CrossRef]

- Manfra, M.J. Molecular Beam Epitaxy of Ultra-High-Quality AlGaAs/GaAs Heterostructures: Enabling Physics in Low-Dimensional Electronic Systems. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2014, 5, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadi, D.J.; Chang, K.J. Energetics of DX-center formation in GaAs and AlxGa1-xAs alloys. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 39, 10063–10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambandamurthy, G.; Lewis, R.M.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.P.; Engel, L.W.; Tsui, D.C.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Observation of Pinning Mode of Stripe Phases of 2D Systems in High Landau Levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 256801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msall, M.E.; Dietsche, W. Acoustic measurements of the stripe and the bubble quantum Hall phase. New Journal of Physics 2015, 17, 043042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, B.; Peng, Y.; Rosenow, B.; von Oppen, F.; Umansky, V.; von Klitzing, K.; Smet, J.H. Negative permittivity in bubble and stripe phases. Nature Physics 2017, 13, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Pan, W.; Stormer, H.L.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Density-Induced Interchange of Anisotropy Axes at Half-Filled High Landau Levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 116803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollanen, J.; Cooper, K.B.; Brandsen, S.; Eisenstein, J.P.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Heterostructure symmetry and the orientation of the quantum Hall nematic phases. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 115410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Shi, Q.; Zudov, M.A.; Chung, Y.J.; Baldwin, K.W.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Quantum Hall stripes in high-density GaAs/AlGaAs quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 205418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodemann, I.; MacDonald, A.H. Theory of Native Orientational Pinning in Quantum Hall Nematics. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1307.5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.B.; Lilly, M.P.; Eisenstein, J.P.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Insulating phases of two-dimensional electrons in high Landau levels: Observation of sharp thresholds to conduction. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 11285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fu, H.; Du, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W.; Du, R.R.; Lin, X. Depinning transition of bubble phases in a high Landau level. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 115301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.M.; Chen, Y.; Engel, L.W.; Tsui, D.C.; Ye, P.D.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Evidence of a First-Order Phase Transition Between Wigner-Crystal and Bubble Phases of 2D Electrons in Higher Landau Levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 176808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Watson, J.D.; Rokhinson, L.P.; Manfra, M.J.; Csáthy, G.A. Contrasting energy scales of reentrant integer quantum Hall states. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 201301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas Rosales, K.A.; Singh, S.K.; Deng, H.; Chung, Y.J.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W.; Baldwin, K.W.; Shayegan, M. Melting phase diagram of bubble phases in high Landau levels. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, L121110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Shi, Q.; Zudov, M.A.; Gardner, G.C.; Watson, J.D.; Manfra, M.J. Two- and three-electron bubbles in AlxGa1-xAs/Al0.24Ga0.76As quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 161402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, D.; Myers, S.A.; Deng, N.; Watson, J.D.; Manfra, M.J.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W.; Csáthy, G.A. Stability of multielectron bubbles in high Landau levels. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 102, 115303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, M.P.; Cooper, K.B.; Eisenstein, J.P.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W. Anisotropic States of Two-Dimensional Electron Systems in High Landau Levels: Effect of an In-Plane Magnetic Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Du, R.R.; Stormer, H.L.; Tsui, D.C.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; Baldwin, K.W.; West, K.W. Strongly Anisotropic Electronic Transport at Landau Level Filling Factor under a Tilted Magnetic Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueed, M.A.; Hossain, M.S.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W.; Baldwin, K.W.; Shayegan, M. Reorientation of the Stripe Phase of 2D Electrons by a Minute Density Modulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 076803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kamburov, D.; Shayegan, M.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W.; Baldwin, K.W. Spin and charge distribution symmetry dependence of stripe phases in two-dimensional electron systems confined to wide quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 075314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gores, J.; Gamez, G.; Smet, J.H.; Pfeiffer, L.; West, K.; Yacoby, A.; Umansky, V.; von Klitzing, K. Current-Induced Anisotropy and Reordering of the Electron Liquid-Crystal Phases in a Two-Dimensional Electron System. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 246402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungwirth, T.; MacDonald, A.H.; Smrčka, L.; Girvin, S.M. Field-tilt anisotropy energy in quantum Hall stripe states. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 15574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanescu, T.D.; Martin, I.; Phillips, P. Finite-Temperature Density Instability at High Landau Level Occupancy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D.; Csáthy, G.A.; Manfra, M.J. Impact of Heterostructure Design on Transport Properties in the Second Landau Level of In Situ Back-Gated Two-Dimensional Electron Gases. Phys. Rev. Applied 2015, 3, 064004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradkin, E.; Kivelson, S.A. Liquid-crystal phases of quantum Hall systems. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 8065–8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradkin, E.; Kivelson, S.A.; Manousakis, E.; Nho, K. Nematic Phase of the Two-Dimensional Electron Gas in a Magnetic Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radzihovsky, L.; Dorsey, A.T. Theory of Quantum Hall Nematics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 216802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Fertig, H.A.; Côté, R. Stability of the Smectic Quantum Hall State: A Quantitative Study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 4156–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barci, D.G.; Fradkin, E.; Kivelson, S.A.; Oganesyan, V. Theory of the quantum Hall Smectic Phase. I. Low-energy properties of the quantum Hall smectic fixed point. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 245319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barci, D.G.; Fradkin, E. Theory of the quantum Hall Smectic Phase. II. Microscopic theory. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 245320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, M.J.; Fradkin, E. Quantum Hall smectics, sliding symmetry, and the renormalization group. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 70, 165310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, R.; Fertig, H.A. Collective modes of quantum Hall stripes. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, 1993–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettouhami, A.M.; Doiron, C.B.; Klironomos, F.D.; Côté, R.; Dorsey, A.T. Anisotropic States of Two-Dimensional Electrons in High Magnetic Fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 196802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, K.; Maeda, N.; Ishikawa, K. Anisotropic ground states of the quantum Hall system with currents. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 045334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Sammon, M.; Zudov, M.A.; Shklovskii, B.I. Isotropically conducting (hidden) quantum Hall stripe phases in a two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 161302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleridge, P.T.; Zawadzki, P.; Sachrajda, A.S. Peak values of resistivity in high-mobility quantum-Hall-effect samples. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 10798–10801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T. Theory of Quantum Transport in a Two-Dimensional Electron System under Magnetic Fields II. Single-Site Approximation under Strong Fields. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1974, 36, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daou, R.; Chang, J.; LeBoeuf, D.; Cyr-Choinière, O.; Laliberté, F.; Doiron-Leyraud, N.; Ramshaw, B.J.; Liang, R.; Bonn, D.A.; Hardy, W.N.; et al. Broken rotational symmetry in the pseudogap phase of a high-Tc superconductor. Nature 2010, 463, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.H.; Analytis, J.G.; Greve, K.D.; McMahon, P.L.; Islam, Z.; Yamamoto, Y.; Fisher, I.R. In-Plane Resistivity Anisotropy in an Underdoped Iron Arsenide Superconductor. Science 2010, 329, 824–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Tao, Z.; Li, T.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, S.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Hone, J.C.; et al. Stripe phases in WSe2/WS2 moirésuperlattices. Nature Materials 2021, 20, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Rodan-Legrain, D.; Park, J.M.; Yuan, N.F.Q.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Fernandes, R.M.; Fu, L.; Jarillo-Herrero, P. Nematicity and competing orders in superconducting magic-angle graphene. Science 2021, 372, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).