1. Introduction

In 1911, MacMillan [

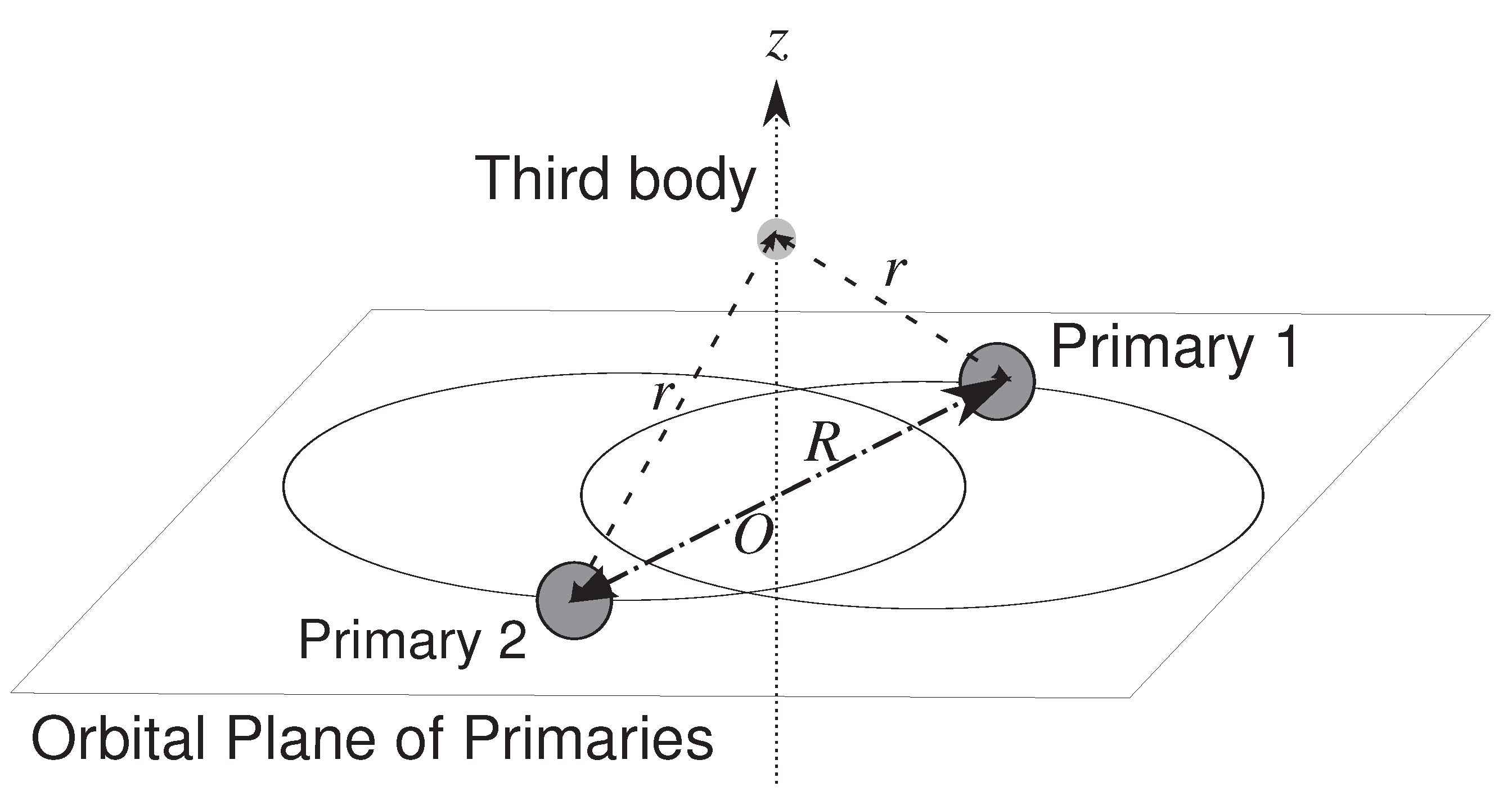

1] demonstrated the existence of a periodic solution to the Newtonian restricted three-body problem under the following configuration: the two central primaries (a binary system) have equal mass

m and revolve around their barycenter in circular orbits, while the third body is a test particle that moves along a trajectory perpendicular to the orbital plane of the binary and passes through their common barycenter, under the influence of Newtonian gravitational attraction. In 1961, within the same configuration, Sitnikov [

2] showed that a periodic solution also exists when the two primaries move along elliptical orbits, see

Figure 1. This type of Newtonian restricted three-body problem is often referred to as the “Sitnikov problem.”

Although the Sitnikov three-body problem is one of the simplest dynamical models, it is known to exhibit a wide range of chaotic behaviors. As a result, the Sitnikov problem has been extensively investigated both analytically and numerically; see, for example, [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] and references therein.

In many previous studies, the three-body problem, including the Sitnikov problem, has been investigated under Newtonian gravity. However, in recent years, with the successful detection of gravitational waves and increasing interest in black hole formation, general relativistic effect in the three-body problem have attracted growing attention.

The general relativistic effect on Euler’s collinear solution was investigated in [

15], and the papers e.g., [

16,

17] studied the contribution of general relativity to Lagrange’s triangle solution, and the stability of the Lagrange points

and

was examined through linear analysis by [

18]. Further, It has been shown that the figure-eight orbit of the three-body system, discovered by Moore [

19] under Newtonian gravity (see also [

20,

21,

22,

23]) exists under general relativistic gravity, see e.g., [

24,

25]. And, some papers such as [

26,

27,

28] considered gravitational wave emission in the three-body problem forming Lagrange’s triangular solution.

On the other hand, The discovery of PSR J0337+1715 has drawn increasing attention to test of general relativity in hierarchical triple systems [

29]. The effect of general relativity in hierarchical three-body systems has been actively discussed, for example, [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] and references therein.

The effect of general relativity on the Sitnikov problem has been considered by [

36,

37]. Kovács

et al. [

36] explore the Sitnikov three-body problem within the first post-Newtonian approximation to assess how relativistic corrections influence its chaotic phase-space structure. Their numerical analysis shows that increasing the dimensionless gravitational radius

leads to bifurcations in phase-space; altering chaotic regions and escape dynamics, and results in systematic changes to the chaotic saddle, including shifts in the positions of KAM islands and escape corridors. This work demonstrates that even weak relativistic effects can significantly impact chaotic scattering in the classical Sitnikov model.

While, Bernal

et al. [

37] investigate a relativistic Sitnikov problem using a first post-Newtonian approximation. They explore how the dimensionless gravitational radius

affects asymptotic behavior and chaotic scattering in the system. They identify (i) a metamorphosis of the KAM islands and associated escape regions as

increases, and (ii) two distinct inflection points in the unpredictability of the final state at

and

. These inflection features are quantified using basin entropy analysis, providing deeper insight into relativistic chaotic scattering in the Sitnikov framework.

In this paper, we numerically investigate the Sitnikov three-body problem within the framework of the first post-Newtonian approximation and present practical and physically concrete results, rather than focusing on chaotic behavior and phase-space perspectives mainly discussed by [

36,

37].

This paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we derive the general relativistic equations of motion used in this study from the Einstein-Infeld-Hoffmann equations. In

Section 3, we present the results of numerical integration of these equations of motion.

Section 4 is devoted to conclusions.

2. Equation of Motion

First, we derive the equations of motion used in this paper from the Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann (EIH) equations, which describe the motion of

N point masses within the first post-Newtonian approximation. The Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann equations are given by: see e.g., [

38,

39],

where

G is the Newtonian gravitational constant,

c is the speed of light in vacuum,

is the mass of body

i,

is the position vector of body

i in the barycentric coordinates system,

,

,

is the coordinate velocity of body

i (

t is the coordinate time), and

. From this equation, we derive the equations of motion for the central binary system and the third body.

2.1. Motion of primary bodies

In this paper, we assume that the third body has an infinitesimally small mass, setting

. Then, the motion of the central binary, consisting of two massive primary bodies (1 and 2), can be described by the relativistic two-body problem. We introduce the relative coordinate,

and from Eq. (

1), The equation of motion of the binary becomes,

in which

,

, and

. In the Sitnikov problem, the central binary stars have equal masses, and we set

, so that

and

. Thus, Eq. (

3) can be rewritten as

Here, we transform the coordinate time

t,

and

into a dimensionless variables

T,

and

as foloows,

where

a is the semi-major axis and

n is the mean motion of central binary. Further let us introduce dimensionless gravitational radius

as foloows,

Then,

corresponds to the Newtonian case. The value of

increases as the mass of the central bodies increases or as the two primary bodies come closer together, and represents the strength of relativistic effect.

Using Eqs. (

5) and (

6), Eq. (

4) is rewritten as,

Eq. (

7) is more suitable for numerical integration than Eq. (

4) since the variables

are of order

.

2.2. Motion of third body

Next, let us write down the equation of motion of the third body (test particle). In the Sitnikov problem, the test particle moves along a trajectory perpendicular to the orbital plane of the central binary and passes through the binary’s center of mass. We therefore assume that the motion of the primary bodies is confined to the

-plane. And because

, we set the positions and velocities of the primaries as follows:

Since, in this paper, we assume the third body is a test particle with

, we set the position and velocity of the third body as follows, respectively:

From Eq. (

1), the equation of motion of third body becomes,

where

As (

5), we use following transformations,

and using Eq. (

6), Eq. (

10) is replaced by,

The configuration of the dynamical system considered in this paper is shown in

Figure 1.

3. Numerical experiments

Let us present the results of the numerical integration of Eqs. (

7) and (

14). The setup of our numerical integration is summarized in

Table 1.

The initial condition of the central binary is chosen as follows:

where

e is the orbital eccentricity of the central binary, with

, varied in intervals of

. The initial values of the third body,

and

, are taken as

with intervals of

, and

. The range of the dimensionless gravitational radius

is

.

Numerical integration is performed using Gragg’s extrapolation method based on the Aitken–Neville algorithm, and the calculation time per orbit is set to a maximum of 1000 Keplerian periods for the central binary.

When the energy of the test particle,

E, becomes positive, the particle is considered to have escaped from the system;

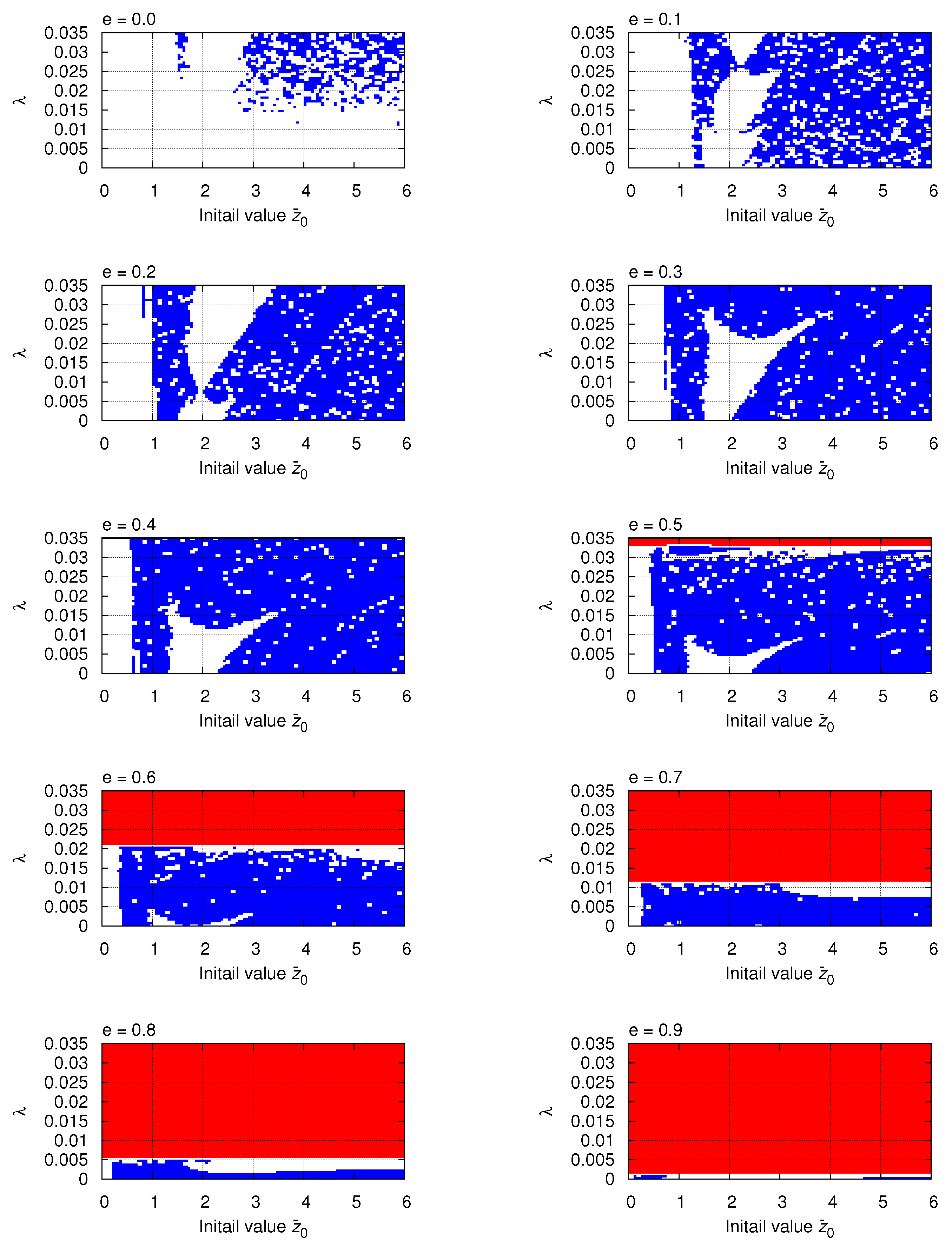

Figure 2 shows the parameter space of

, where blue indicates the parameter region where the test particle was ejected from the system, while red depicts the region where a collision with the central binary star occurred. The collision of the central binary is caused by large values of

as well as by the orbital eccentricity

e.

Through numerical experiments, it has been found that collisions between the primaries occur when the periastron distance of the binary becomes smaller than several tens of times the Schwarzschild radius.

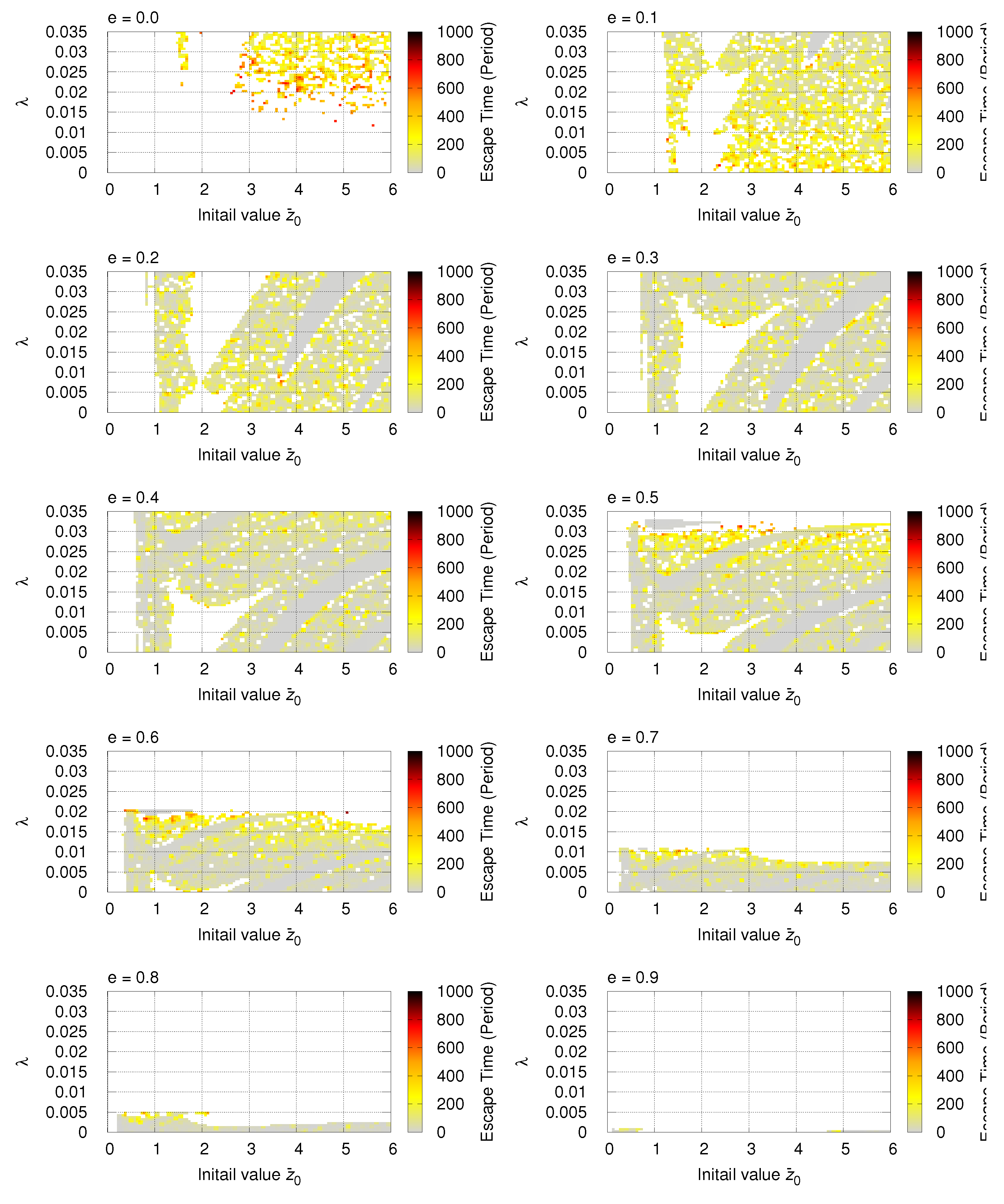

Figure 3 illustrates the escape time of the test particle from the system. In the case of

(i.e., the orbit of the primaries is circular), the escape time of the test particle is very long, and it can remain in the system for an extended period. As the dimensionless gravitational radius

and the eccentricity of the binary orbit

e increase, the tendency for the test particle to escape from the system becomes more pronounced.

As a general trend, when the orbital eccentricity of the central binary is small, it takes longer for the test particle to escape from the system. However, as the eccentricity increases, the particle escapes in a shorter time. An increase in the orbital eccentricity of the central binary leads to larger oscillations in the relative distance between the two bodies, and it is thought that the periodic variations in the relative distance affect the escape of the test particles.

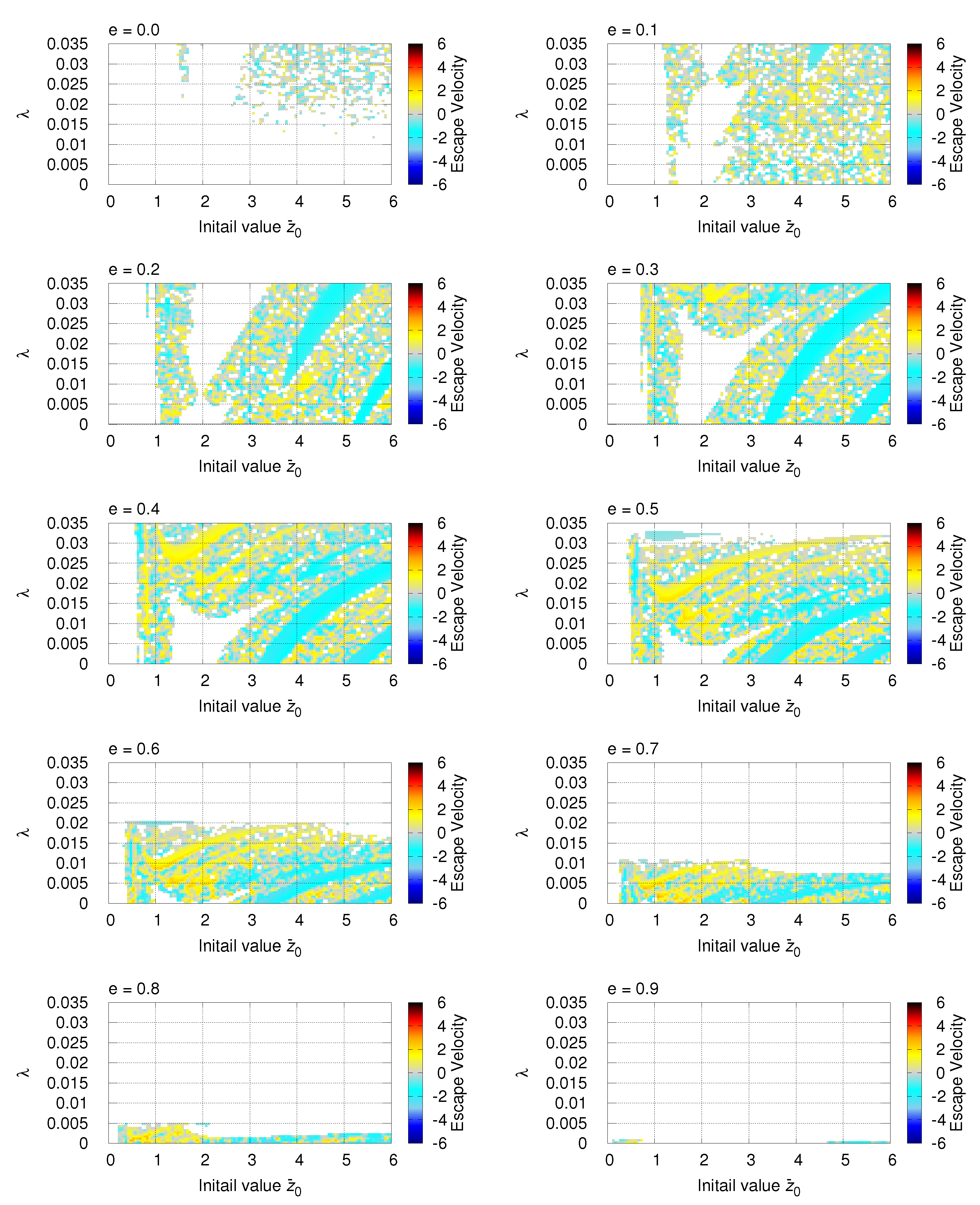

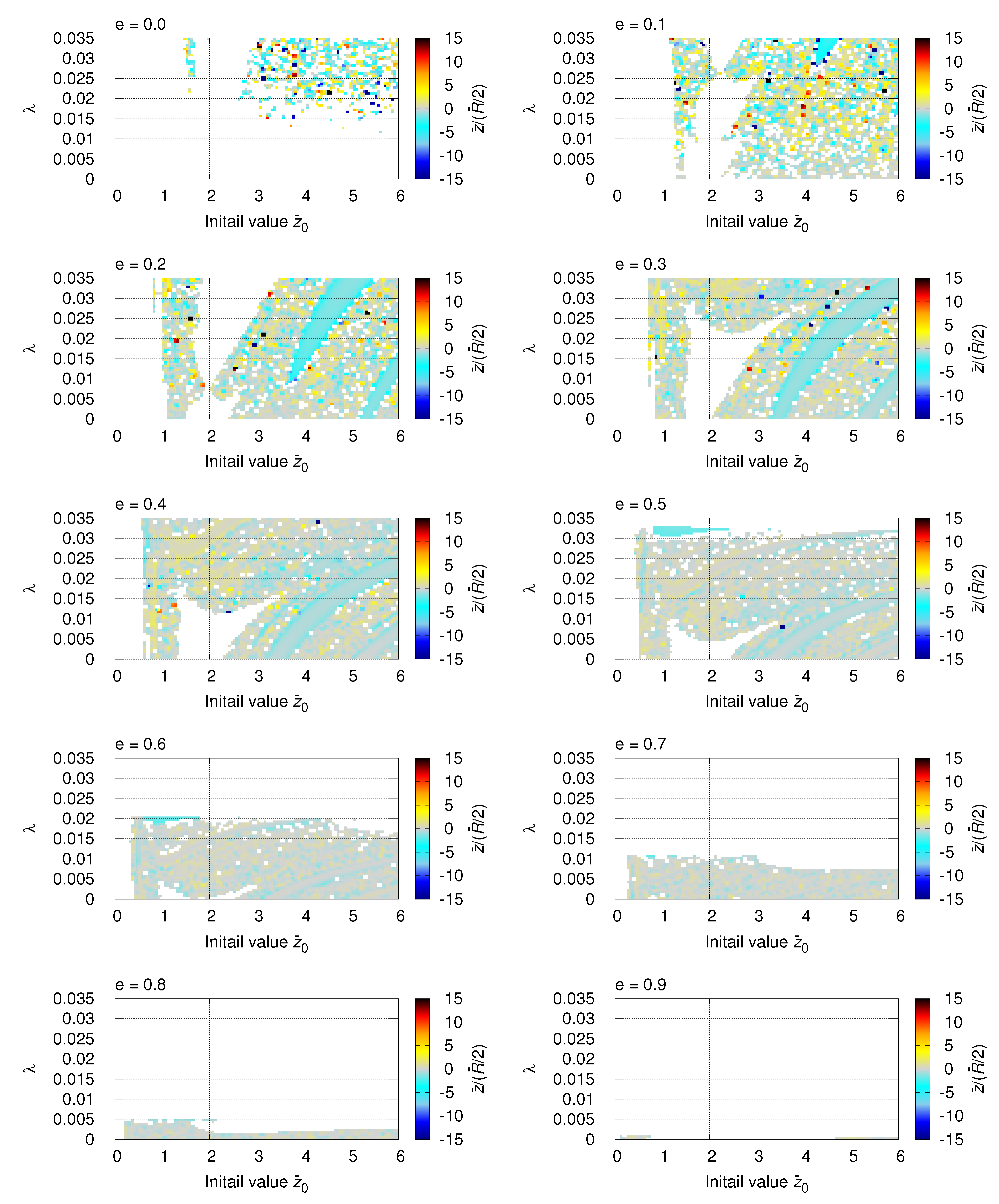

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the escape velocity and the

ratio of the test particle at the moment of escape from the system, respectively. Due to the orbital eccentricity of the binary, the distance between the two primaries is not constant but fluctuates; therefore, the ratio

is used, instead of

, to represent the spatial relationship between the test particle and the binary. A small value of this ratio indicates that the test particle escaped near the orbital plane of the binary, and in the case of a large value of the ratio, the test particle leaves the system at a location farther away from the binary.

From

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, it can be observed that when the eccentricity of the binary orbit is small, the escape velocity of the test particle tends to be relatively low, and the ratio

tends to be large — that is, the test particle is more likely to escape from a location far from the binary. On the other hand, as the eccentricity of the central binary increases, the test particle tends to escape at a higher velocity from a position closer to the orbital plane of the binary.

Figure 6 shows the acceleration acting on the test particle at the moment it escapes from the system. It can be observed that, as the eccentricity of the binary orbit increases, regions with higher acceleration (indicated in yellow or cyan) appear. However, the overall trend is that the acceleration acting on the test particle is nearly zero when it moves far away from the system.

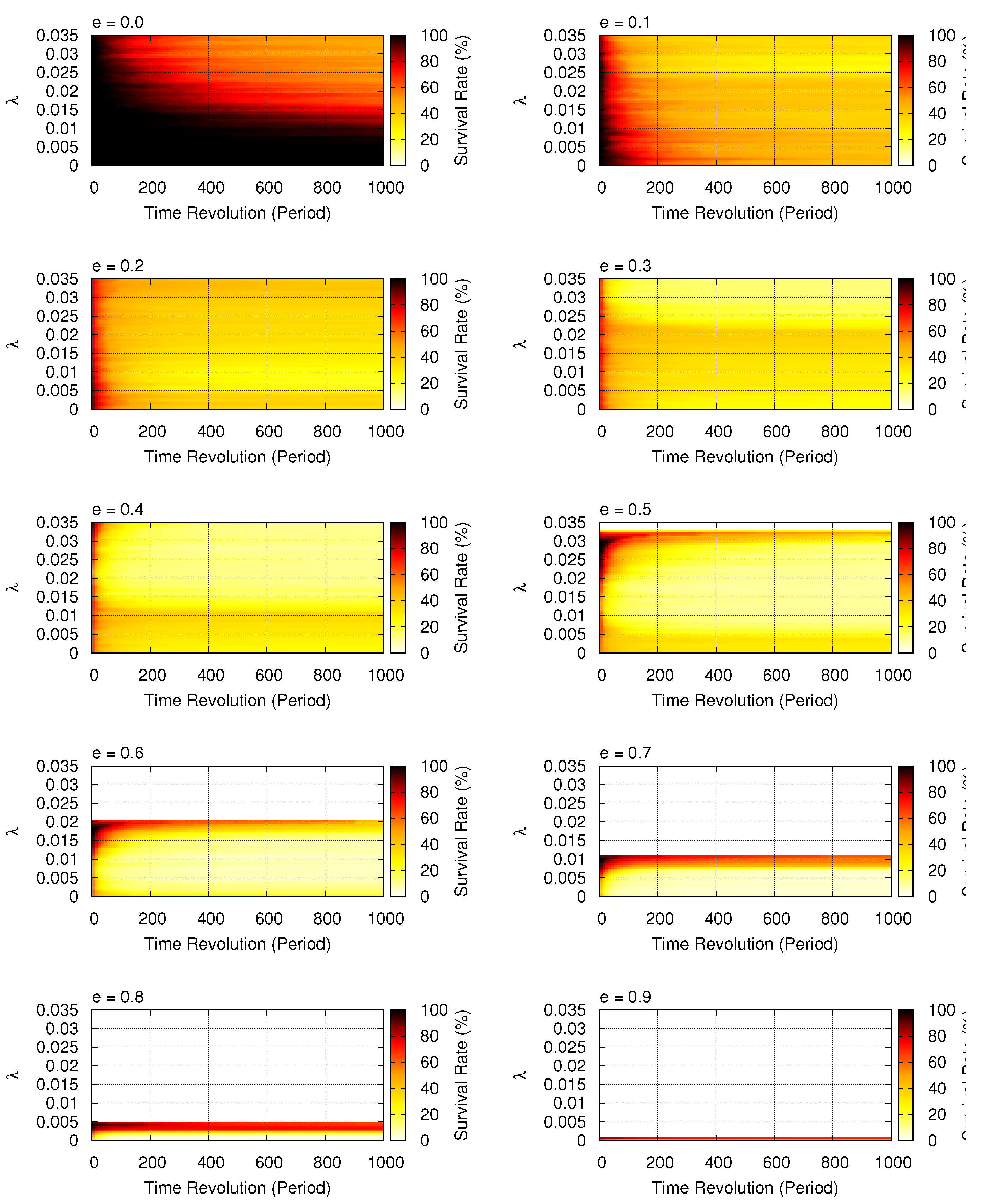

Figure 7 shows the survival rate of test particles that remain in the system up to 1000 orbital periods of the central binary. Given the eccentricity

e of the binary orbit and the dimensionless gravitational radius

, the number of initial values of

is

, since

varies from 0 to 6 in increments of 0.05. Therefore,

Figure 7 represents the ratio

as a function of orbital period of centrap binary,

P where

mewns the number of particles remaining in the system at period

P.

For the range

, the number of surviving test particles decreases with increasing values of both the dimensionless gravitational radius

and the orbital eccentricity of the binary

e. However,

, there exists a region where the number of s urviving test particles increases despite the increase in

; for example, see the dark-colored area around

in the upper left of

Figure 7, where

.

Looking at

Figure 2, the region where the number of surviving particles increases with increasing

is the region where there are many test particles remaining in the system. This region exists near the lower limit of the region where the central binary collision occurs.

Throughout the numerical experiments, it can be seen that general relativistic effect does not bind test particles to the system, but rather acts to eject them from the system. In addition, we can see that the increase in the eccentricity of the central binary orbit is also contributing to this tendency.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we investigated the effect of general relativity on the Sitnikov problem. To study the general relativistic contributions, we first derived the equations of motion for both the binary and the test particle based on the first post-Newtonian Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann equation, and integrated these equations numerically. We examine the behavior of the test particle (third body) as a function of the orbital eccentricity of the central binary e, the dimensionless gravitational radius , which characterizes the strength of general relativistic effect, and the initial position of the test particle .

Our numerical calculations revealed the following: (a) Due to general relativistic effect and increasing eccentricity of the central binary, the test particle is likely to be ejected from the system. (b) When the binary’s eccentricity is low, it takes longer for the test particle to be ejected from the system; however, as the eccentricity increases, the particle tends to be ejected more quickly. (c) The escape velocity of the test particle tends to increase with the binary’s eccentricity. (d) When the binary’s eccentricity is small, the test particle is ejected farther from the orbital plane of binary; as the eccentricity increases, the particle is likely to be ejected closer to the plane. And (e) although the acceleration acting on the test particle can be seen to increase as the eccentricity and dimensionless gravitational radius become larger, overall, the acceleration acting when the test particle escapes from the system is generally zero.

As mentioned at the end of

Section 3, in the Sitnikov three-body problem, the increase both in general relativistic effects and in the eccentricity of the central binary orbit contribute to the ejection of the test particle from the system rather than binding it to the system. Then, as one possible application of the Sitnikov problem, it may be conceivable to explain the mechanism of astrophysical jets, especially Relativistic jets.

The Blandford–Payne mechanism and the Blandford–Znajek mechanism have been proposed as leading theories for the formation of relativistic jets; however, a complete understanding has not yet been achieved. To resolve this issue, it is essential to determine which of the two mechanisms predominantly operates, or whether both do, and to provide detailed observational verification of the black hole spin and magnetic field structure. In addition, a coherent explanation of the continuous process by which the jet is formed, accelerated, and collimated (i.e., from formation to acceleration and stabilization) is required. If jets are emitted from a (nearly) equal-mass binary black hole system, then, as a consequence of the Sitnikov problem, particle motion in the z-direction (perpendicular to the binary orbital plane) may be enhanced. This could potentially contribute to a better understanding of the jet acceleration and collimation processes. This is because, as demonstrated by our numerical calculations, in the Sitnikov problem, relativistic effect and an increase in the orbital eccentricity of binary tend to expel test particles from the system. When ejected, the test particles either possess high velocities or experience nearly zero acceleration, indicating that they are not gravitationally bound.

In this paper, we have considered the third body as a test particle, but if we regard the third body as a massive particle, the central binary star will be affected by the gravity of this third body. Then, the behavior of the system will become more complex. Gravitational waves from such three-body system have not been studied so far, therefore it would be worthwhile to investigate them in the future.

Funding

This research was partially supported by Dean’s Grant for Specified Incentive Research, College of Engineering, Nihon University.

References

- W. D. MacMillan (1913), AJ, 27, iss. 625-626, 11.

- K. Sitnikov (1960), Dokl. Akad. Nauk. USSR, 133, 303.

- J. Alfaro, C. Chiralt (2005), CMDA, 55, 351.

- E. Belbruno, J. Llibre, M. Olle (1994), CMDA, 60, 99.

- M. Corbera, J. Llibre (2000), CMDA, 77, 273.

- R. Dvorak (1993), CMDA, 56, 71.

- R. Dvorak (2007), Publ. Astron. Dept Eötvös Univ., 19, 129.

- J. Hagel, Ch. Lhotka (2005), CMDA, 93, 201.

- M. A. Jalali, S. H. Pourtakdoust (1997), CMDA, 68, 151.

- J. Kallrath, R. Dvorak , J. Schlöder (1997), ’The Dynamical Behaviour of our Planetary System: Proceedings of the Rourth Alexander van Humboldt Colloquium on Celestial Mechanics’ (in Dvorak R., Henrard J., eds), Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dodrecht, p. 415.

- T. Kovács, B. Érdi (2007), AN, 328, 801.

- J. Liu, Y. S. Sun (1990), CMDA, 49, 285.

- E. Perdios, V. V. Markellos (1988), CMDA, 42, 187.

- K. Wodnar (1991), ’Predictability, Stability, and Chaos in N-body Dynamical Systems’, Plenum Press, New York.

- K. Yamada & H. Asada (2011), Phys. Rev. D, 82, 104019.

- T. Ichita, K. Yamada, & H. Asada (2011), Phys. Rev. D, 83, 084026 .

- K. Yamada & H. Asada (2012), Phys. Rev. D, 86, 124029.

- K. Yamada, T. Tsuchiya, & H. Asada (2015), Phys. Rev. D, 91, 124016.

- C. Moore (1993), Phys. Rev. Lett., 70, 3675.

- A. Chenciner & R. Montgomery (2009), Ann. Math., 152, 881.

- D. C. Heggie (2000), Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 318, L61.

- C. Simo (2002), Contemp. Math., 292, 209.

- T. Fujiwara, H. Fukuda, & H. Ozaki (2003), J. Phys. A., 36, 10.

- T. Imai, T. Chiba, & H. Asada (20070, Phys. Rev. Lett., 98, 201102.

- C. O. Lousto & H. Nakano (2007), Class. Quant. Grav., 25, 195019.

- Y . Torigoe, K. Hattori, & H. Asada (2009), Phys. Rev. Lett., 102, 251101.

- H. Asada (2009), Phys. Rev. D, 80, 064021.

- K. Yamada & H. Asada (2016), Phys. Rev. D, 93, 084027.

- S. M. Ransom, I. H. Stairs, A. M. Archibald, J. W. T. Hessels, D. L. Kaplan, M. H. van Kerkwijk, J. Boyles, A. T. Deller, S. Chatterjee, A. Schechtman-Rook, A. Berndsen, R. S. Lynch, D. R. Lorimer, C. Karako-Argaman, V. M. Kaspi, V. I. Kondratiev, M. A. McLaughlin, J. van Leeuwen, R. Rosen, M. S. E. Roberts & K. Stovall (2014), Nature, 505, 520.

- S. Naoz, B. Kocsis, A. Loeb, & N. Yunes (2013), Astrophys. J., 773, 187.

- C. M. Will (2014), Phys. Rev. D, 89, 044043.

- C. M. Will (2018), Phys. Rev. Lett., 120, 191101.

- B. Liu, D. Lai, & Y.-H. Wang, Astrophys. J., 883, L7.

- H. Lim & C. L. Rodriguez (2020), Phys. Rev. D, 102, 064033.

- H. Suzuki, P. Gupta, H. Okawa, & K. Maeda (2021), MNRAS, 500, 1645.

- T. Kovács, Gy. Bene,,T. Tél (2011), MNRAS, 414, 2275.

- Juan D. Bernal; Jesús M. Seoane; Juan C. Vallejo; Liang Huang; Miguel A. F. Sanjuán (2020), PRE, 102, id.042204.

- C. W. Misner, K. S. Thorne, J. A. Wheeler (1973), ’Gravitation’, W. H. Freeman.

- C. M. Will (2014), Living Rev. Relativ. 17, 4.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).