1. Introduction

Berberine hydrochloride, a quaternary isoquinolinium alkaloid [

1], is widely recognized for its pharmacological effects, particularly in the management of type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and microbial infections [

2]. It occurs naturally in several medicinal plants, most notably

Berberis aristata, Coptis chinensis, and Hydrastis canadensis, and has a longstanding history of use in both Eastern and Western herbal medicine traditions [

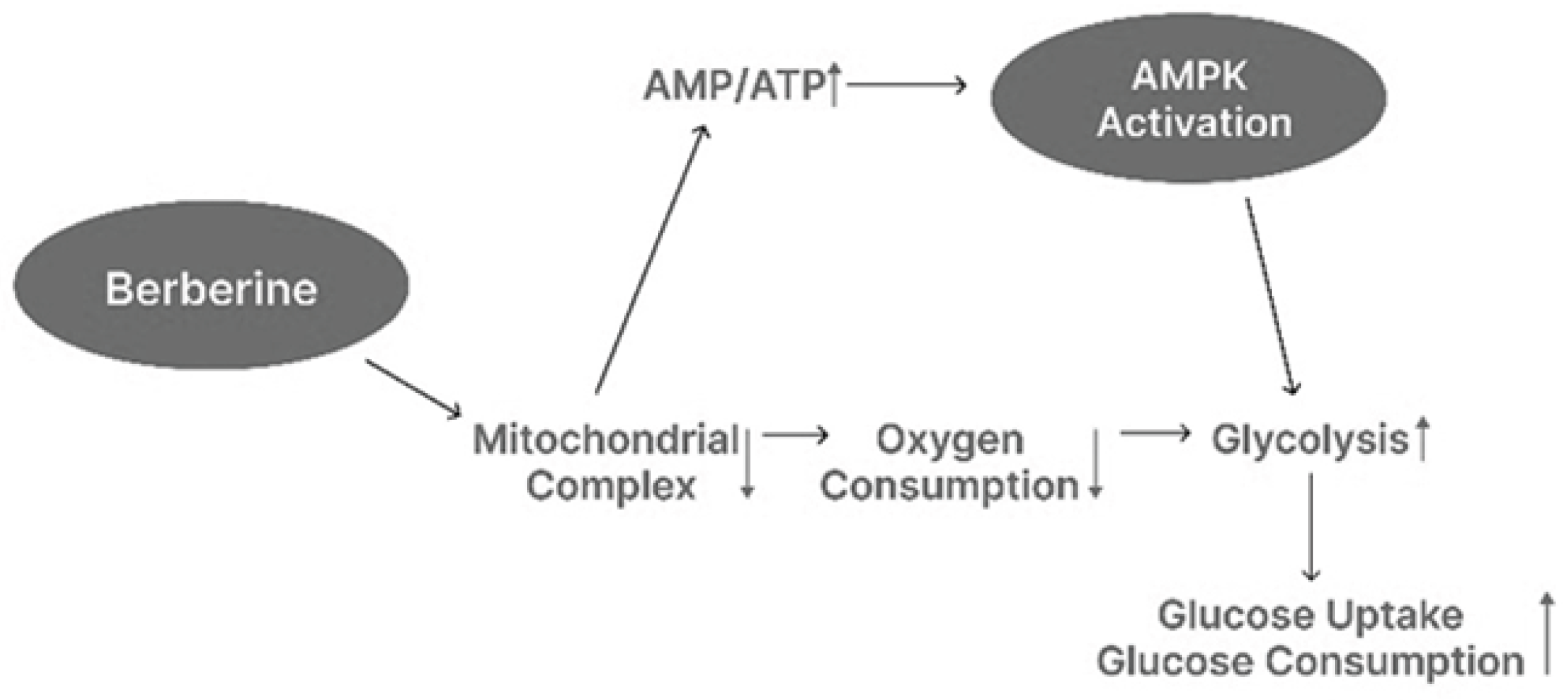

3]. Berberine’s anti-diabetic activity is primarily attributed to the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [

4], a central regulator of cellular energy homeostasis, as shown in

Figure 1. AMPK activation enhances glucose uptake, improves insulin sensitivity, and suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis. In addition to its direct effect on AMPK, berberine inhibits mitochondrial respiratory complex I, leading to reduced oxygen consumption and an elevated intracellular AMP/ATP ratio, which further stimulates AMPK activation [

5]. This cascade promotes increased glycolysis and facilitates glucose uptake and utilization in peripheral tissues [

6].

Figure 1.

Mechanism of Berberine-Induced AMPK Activation and Metabolic Effects.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of Berberine-Induced AMPK Activation and Metabolic Effects.

In recent years, growing concerns have emerged over the adulteration of “all-natural” dietary supplements with undisclosed synthetic compounds, particularly in categories like weight loss, sexual enhancement, and pain relief [

7]. This underscores the need for rigorous evaluation of product content and safety. In the case of berberine hydrochloride, synthetic production (i.e. using synthetic precursors and not plant material) offers several practical advantages, specifically, higher yields [

8] and therefore lower production costs, which make it attractive for meeting rising global demand. However, chemical synthesis of berberine raises important safety concerns, specifically the potential for unreacted intermediates.

Among the most serious concerns with synthetic berberine is the potential formation of nitrosamine intermediates. Nitrosamines are genotoxic in several animal models, and some have been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as probable or possible human carcinogens [

9]. The ICH M7(R2) guideline (Assessment and Control of DNA Reactive [Mutagenic] Impurities in Pharmaceuticals to Limit Potential Carcinogenic Risk, July 2023) includes nitrosamines in a group known as the “cohort of concern” [

10]. The guideline recommends that such impurities be controlled at levels low enough to pose negligible cancer risk in humans, reinforcing the importance of monitoring these compounds during synthesis. Nitrosamines typically form through the reaction of secondary amines with nitrosating agents in acidic environments [

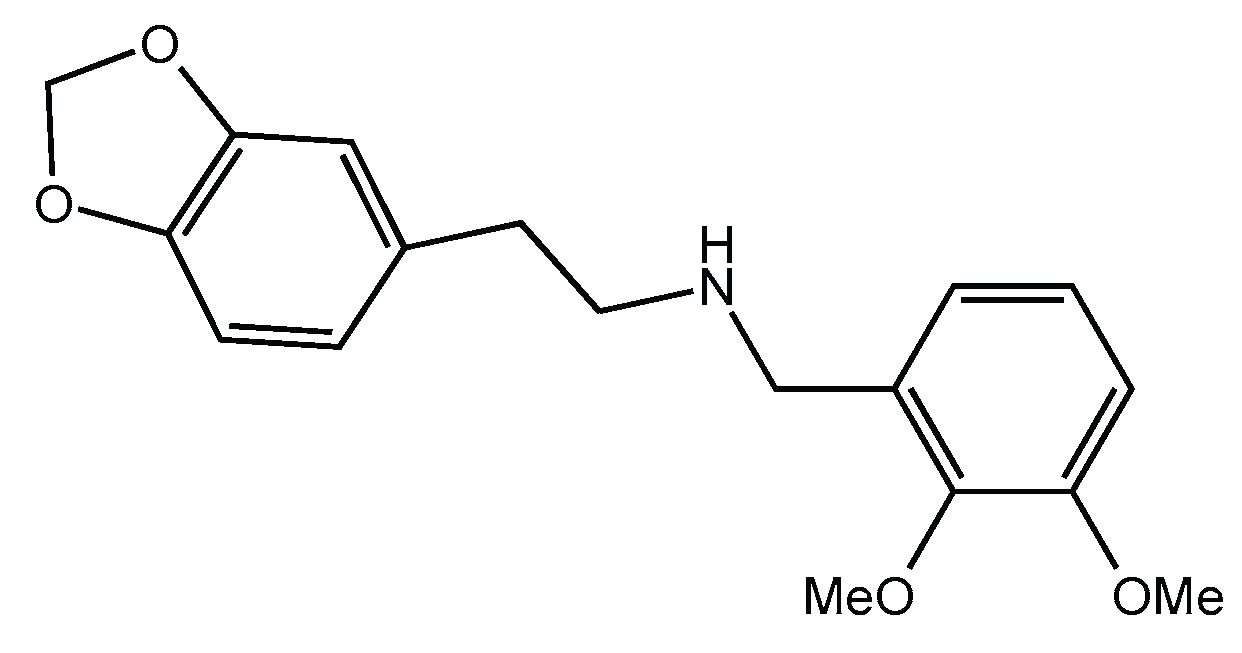

11]. Our review found that 10 out of 12 reported synthetic methods involved conditions conducive to nitrosamine formation. For example, synthetic routes described in patents such as CN106543171A and CN113735847A employ intermediates like homopiperonylamine and aromatic aldehydes in the presence of mineral acids (e.g., HCl) to produce 1-(2-methoxyphenoxy)-3-(2-methoxyphenylamino)propan-2-ol (

Figure 2), conditions that may be conducive to nitrosamine formation. [

12,

13,

14]

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of 1-(2-methoxyphenoxy)-3-(2-methoxyphenylamino)propan-2-ol.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of 1-(2-methoxyphenoxy)-3-(2-methoxyphenylamino)propan-2-ol.

The broader relevance of this risk is underscored by recent discoveries of nitrosamine contamination in various pharmaceutical products, including Metformin, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which led to recalls and regulatory warnings [

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, nitrosamines have also been detected in dietary supplements including herbal formulations [

18,

19].

In addition to nitrosamines, residual solvents used in synthesis, purification, or crystallization, such as dichloromethane (DCM), benzene, methanol, and acetonitrile pose significant toxicological risks if not adequately removed. Benzene is classified as a Class 1 solvent (to be avoided), while methanol and DCM fall under Class 2 according to ICH Q3C(R8), each with strict permitted daily exposure (PDE) limits [

20,

21,

22]. Additional risks stem from the chemical reagents and catalysts used in berberine synthesis. For instance, some documented processes employ precursors such as catechol and methylene chloride, both of which have recognized carcinogenic potential [

25,

26,

27]. These not only pose consumer safety risks but also raise occupational health concerns for manufacturing personnel.

Synthetic ingredients in nutraceuticals, such as berberine, may possibly contain residual impurities like nitrosamines. Increasing awareness of this possibility can help both consumers and businesses make more informed choices. In contrast, berberine obtained through aqueous or organic solvent extraction of plant sources typically avoids the use of nitrosating agents and amine-based intermediates, offering a comparatively safer profile. Natural extracts also often retain a rich phytochemical profile mimicking more closely to that of the natural substance, which may serve as markers of botanical authenticity [

28]. Such markers when combined with radiocarbon (Carbon-14) analysis can help solidify natural origin claims and prevent synthetic products from being misrepresented as plant-derived [

29].

The goal of this review article is to inform key stakeholders including manufacturers, regulators, and consumers of the risks posed by synthetic routes, and to advocate for a safety-first approach in the production and labeling of berberine-containing supplements.

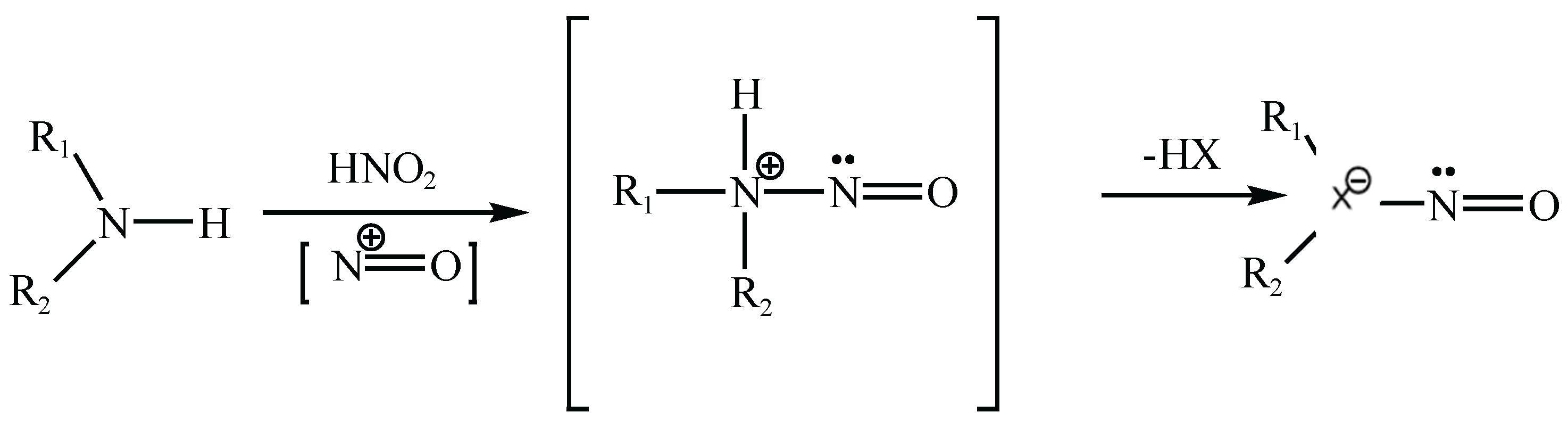

2. Molecular Basis of Nitrosamine Formation

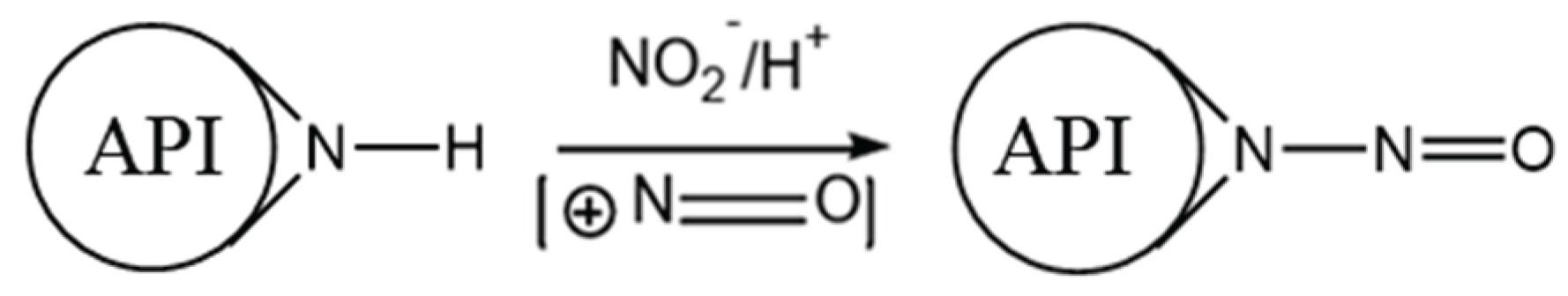

Nitrosamines are a class of chemical compounds characterized by the presence of a nitroso group (–N=O) bonded to a nitrogen atom, typically of a secondary or tertiary amine (general structure: R₁N(–R₂)–N=O). Their formation is primarily driven by nitrosating reactions involving amines and nitrosating agents such as nitrous acid (HNO₂), nitrosyl chloride (NOCl), dinitrogen trioxide (N₂O₃), and other NO⁺-releasing species, as shown in

Figure 3. Under acidic conditions, nitrite salts (e.g., NaNO₂) readily convert to nitrous acid, making them frequent contributors to nitrosamine formation [

30].

Figure 3.

Representative Reaction to Form Nitrosamines.

Figure 3.

Representative Reaction to Form Nitrosamines.

Secondary amines are the most common precursors for nitrosamine formation due to their ability to form stable N-nitroso compounds. In contrast, primary amines typically generate unstable diazonium salts, which rapidly decompose, and tertiary amines may only form nitrosamines through slower dealkylation processes [

10,

11].

The risk of nitrosamine impurities is a key concern in pharmaceutical and nutraceutical manufacturing, where conditions such as low pH (<5), high temperatures, and the presence of amines or trace nitrites can promote their formation [

10,

11]. The FDA’s 2024 guidance, Control of Nitrosamine Impurities in Human Drugs, highlights processes involving secondary or tertiary amines, acid catalysts, or nitrite-containing reagents as particularly high-risk for nitrosamine generation.

Many industrial-scale synthetic routes for berberine hydrochloride reviewed in this work exhibit such features: amino intermediates, use of mineral acids (e.g., HCl) and heating steps, all of which align with FDA-flagged risk factors. If not properly mitigated, these pathways may lead to the formation of nitrosamine impurities in the final product, posing a genotoxic and potentially carcinogenic risk to consumers.

Understanding the chemical mechanisms and identifying at-risk steps in synthetic routes is therefore critical. This includes proactive selection of low-nitrosamine-risk starting materials, controlling pH and temperature during processing, avoiding nitrite contamination, and implementing validated analytical methods for impurity detection.

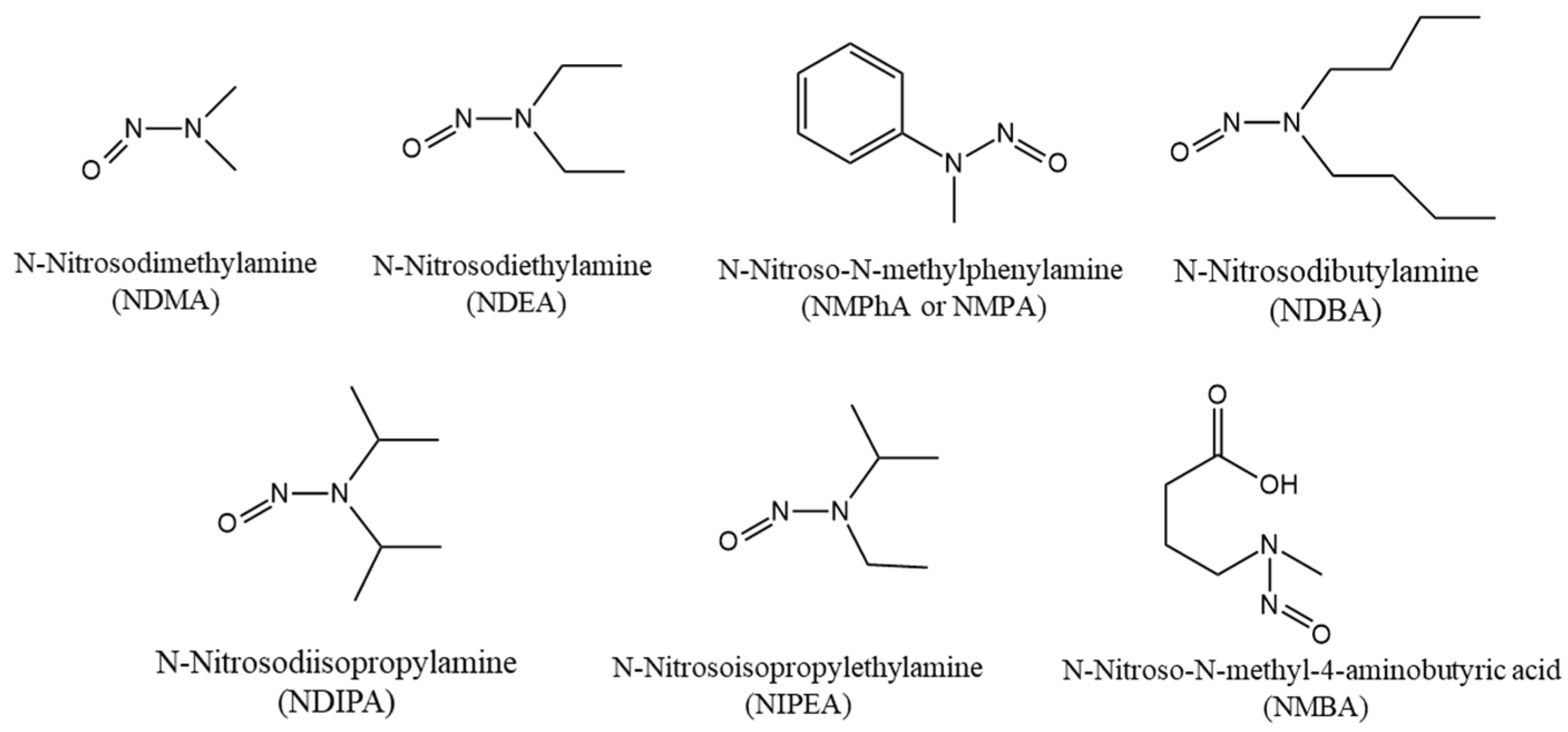

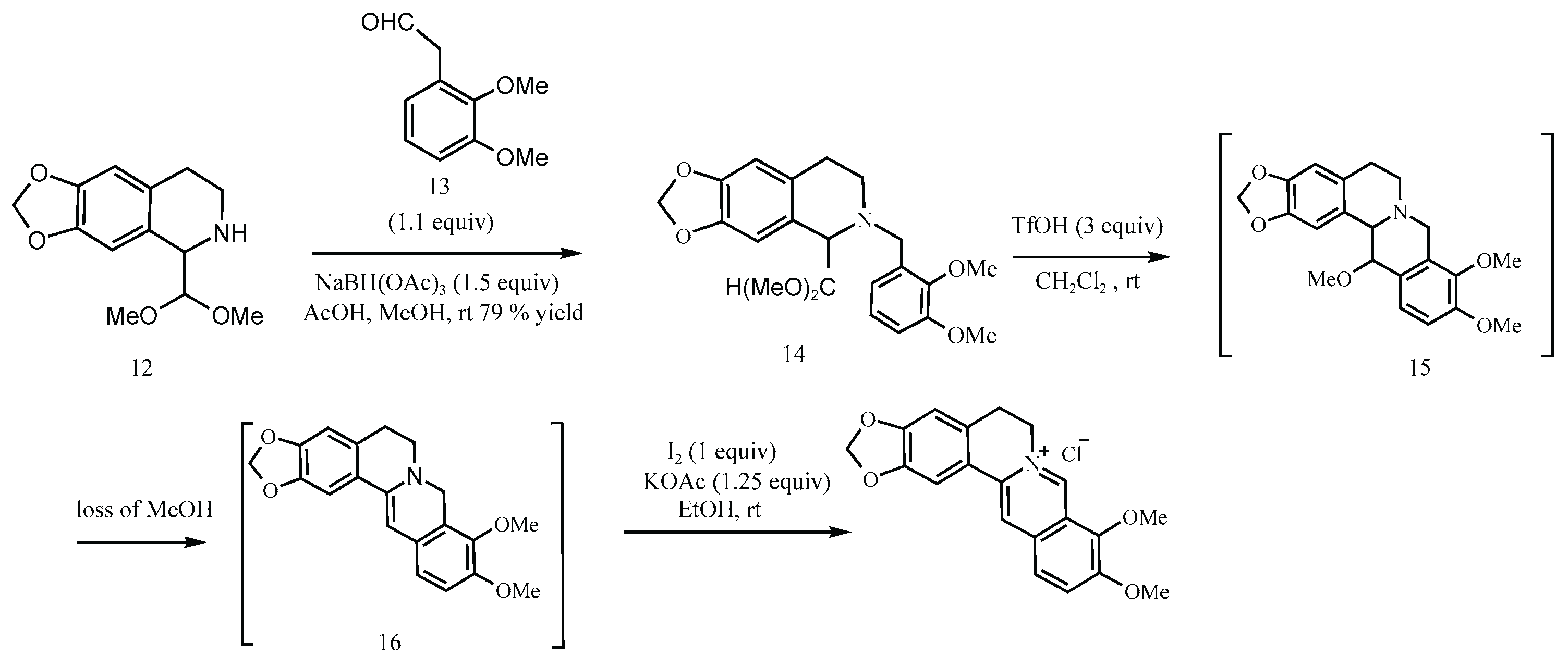

The FDA classifies nitrosamine impurities into two principal categories: small-molecule nitrosamines (as listed in

Figure 4) and nitrosamine drug substance-related impurities (NDSRIs) [

30]. Small-molecule nitrosamines, such as NDMA and NDEA, typically form when secondary amines react with nitrosating agents during chemical synthesis or manufacturing processes. In contrast, NDSRIs (illustrated in

Figure 5) are structurally linked to a specific active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), often incorporating part of the API within their molecular structure. These impurities arise when the drug substance itself, or a related intermediate, undergoes nitrosation—making them generally unique to each API.

While NDSRIs are highly relevant to pharmaceutical manufacturing, this article focuses on small-molecule nitrosamines that may form during the synthetic production of berberine hydrochloride.

Figure 4.

Chemical Structures of Potential Small-Molecule Nitrosamine Impurities.

Figure 4.

Chemical Structures of Potential Small-Molecule Nitrosamine Impurities.

Figure 5.

Representative Reaction of NDSRI Formation.

Figure 5.

Representative Reaction of NDSRI Formation.

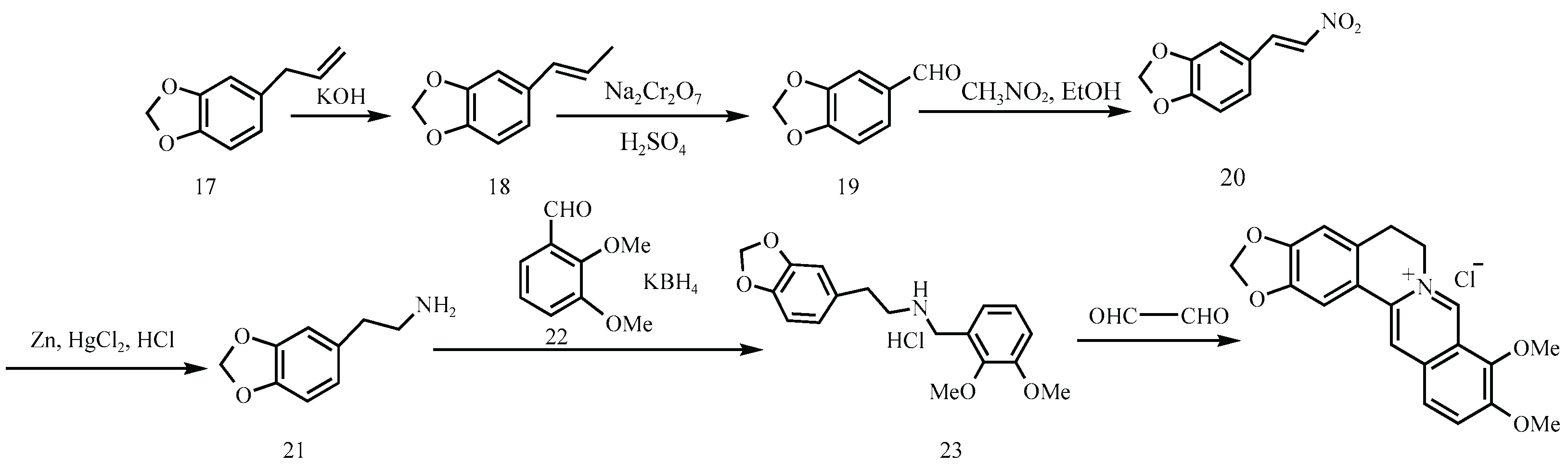

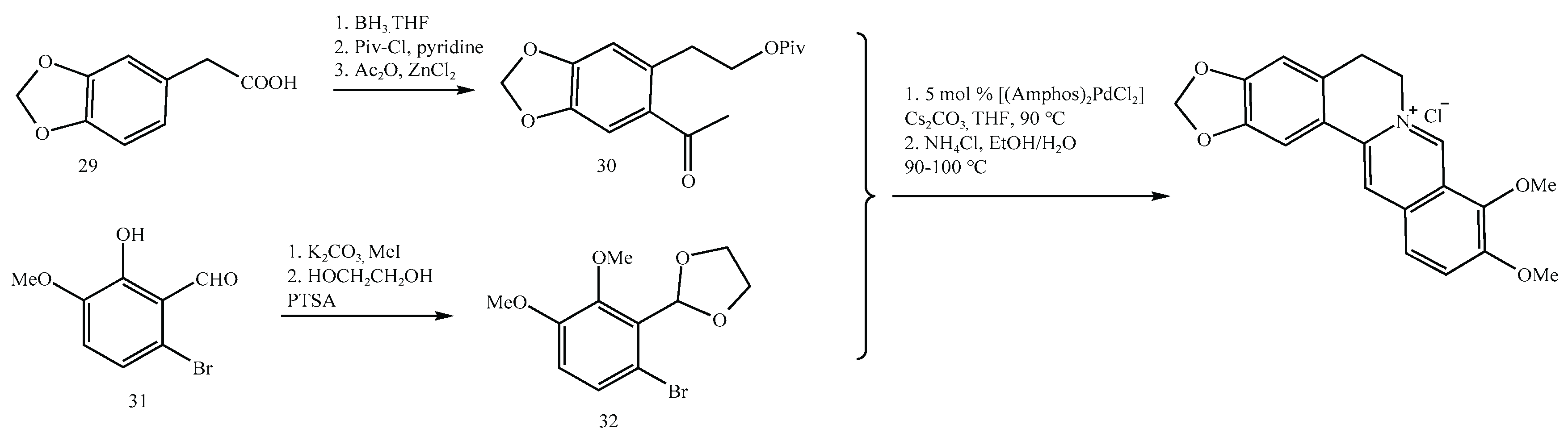

3. Nitrosamine Risk in Synthetic and Natural Berberine Hydrochloride: Routes, Inte Mediates, and Regulatory Implications

Over the past century, synthetic strategies for berberine hydrochloride have evolved significantly, from the foundational condensation reactions reported by Pictet and Gams in 1911 [

31], to Kametani’s landmark total synthesis in 1969 [

32], and more recently to palladium-catalyzed and convergent approaches (

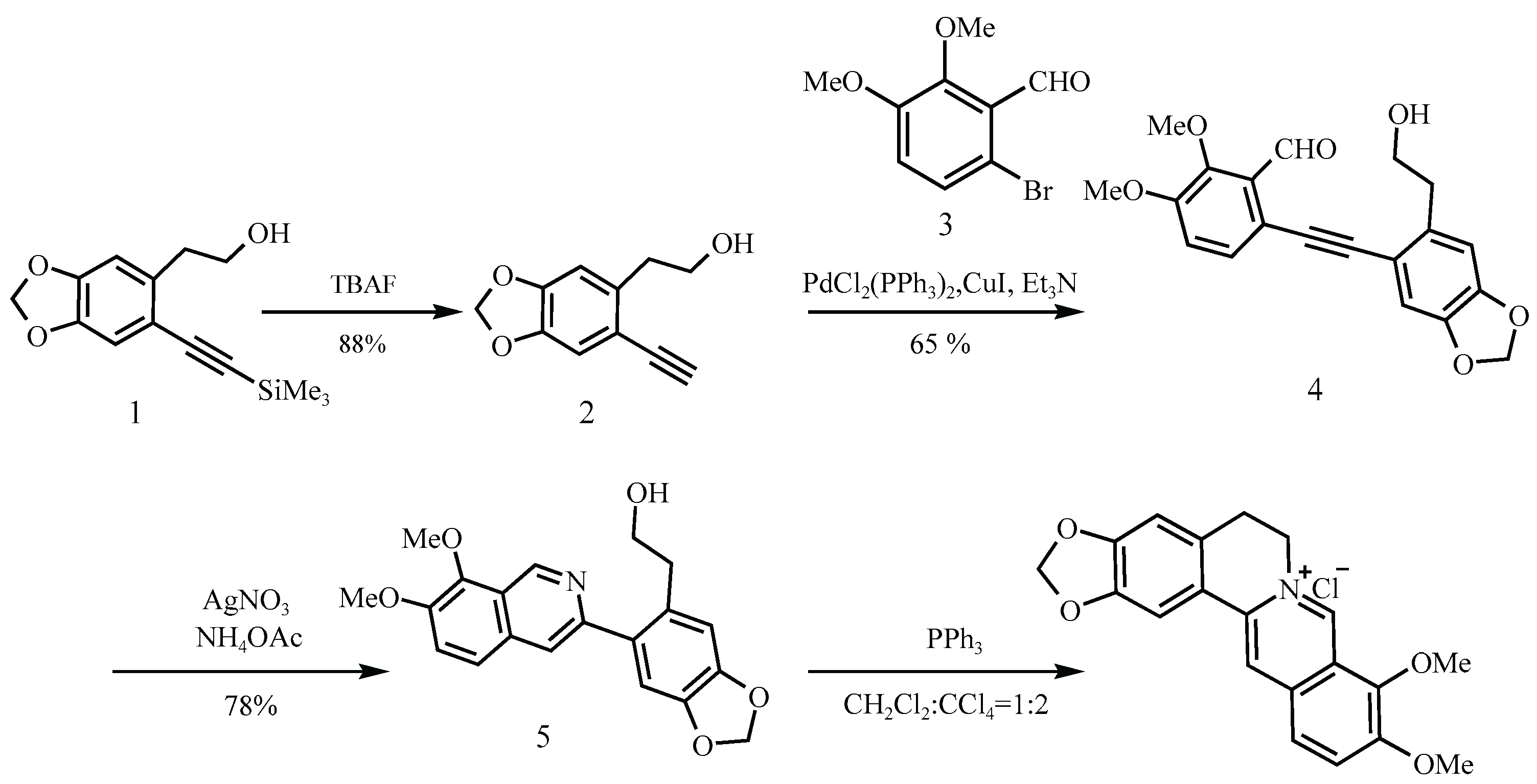

Figure 6 and Figure 7) [

33,

34]. While these advances have improved yield and efficiency many industrially favored routes continue to utilize reagents and conditions that especially raise safety concerns under current impurity control frameworks, such as ICH M7(R2) and the FDA’s 2024 guidance on nitrosamine impurities [

9,

15]. For example,

Figure 6 shows a synthesis scheme that employs DCM in the final step, a solvent associated with both environmental and human toxicity concerns, while

Figure 7 shows a scheme that involves secondary amine intermediate (Molecule 6), a moiety that can potentially facilitate nitrosamine formation under acidic conditions or in the presence of nitrites.

Figure 6.

Anand’s synthetic route [

33].

Figure 6.

Anand’s synthetic route [

33].

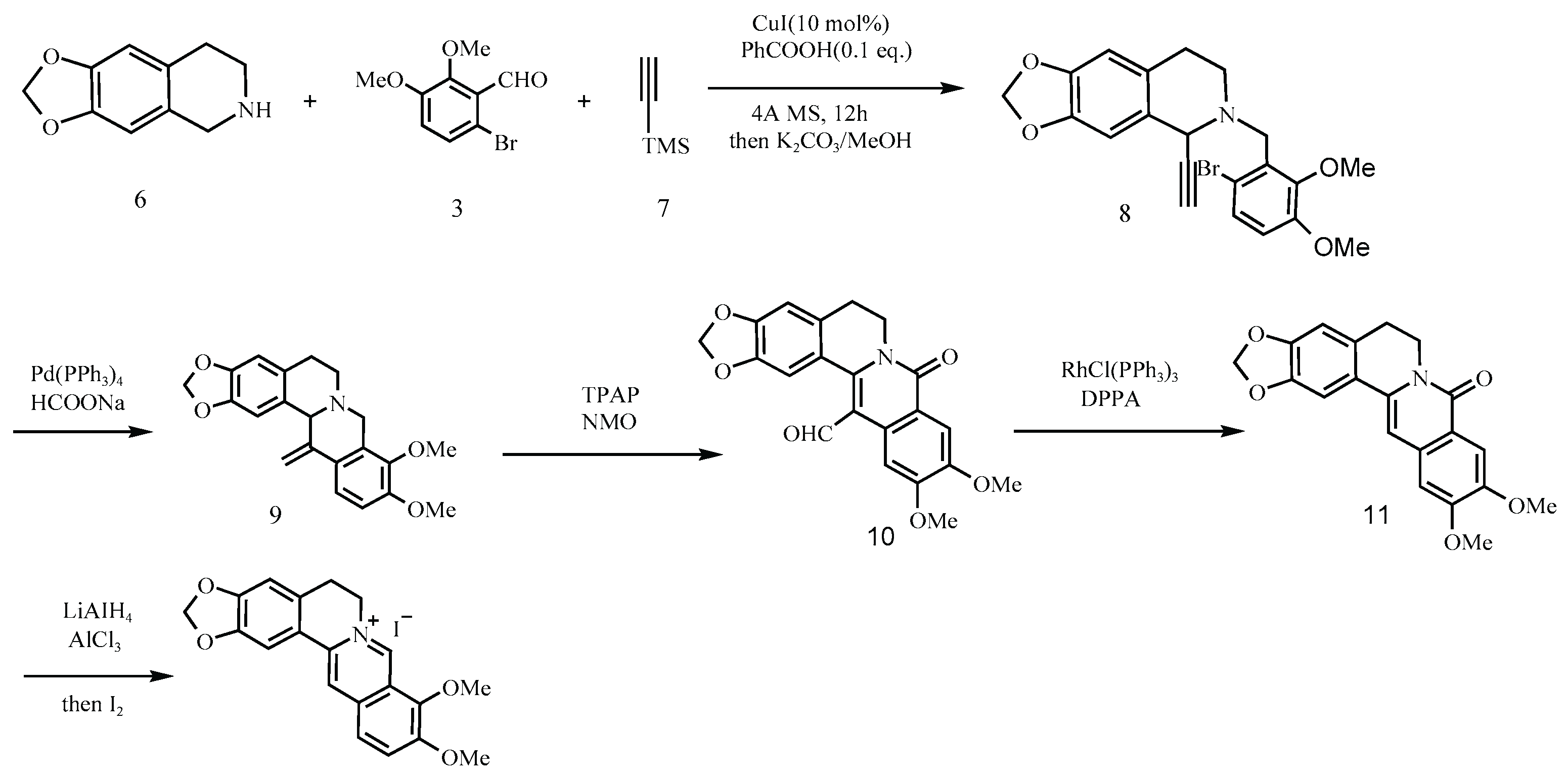

Figure 7.

Tong’s synthetic route [

34].

Figure 7.

Tong’s synthetic route [

34].

A cautionary precedent can be drawn from the cases of metformin and ranitidine, both recalled due to contamination with N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a probable human carcinogen [

15,

16,

35]. Investigations revealed that nitrosamines can form when amine-containing intermediates encounter trace nitrites under acidic conditions, commonly encountered during synthesis or storage. These nitrites may arise from contaminated solvents, acids, or excipients, illustrating that even tightly controlled processes are vulnerable to inadvertent nitrosation [

16].

Another representative scheme is shown in

Figure 8 [

8], where berberine hydrochloride is synthesized via a four-step process beginning with the reductive amination of a secondary amine (Molecule 12) and an aldehyde (13). Although this route avoids classical nitrosating agents and offers a decent yield (54%), the use of secondary amines in acidic environments remains a well-established risk factor.

Figure 8.

Clift’s synthetic route [

8].

Figure 8.

Clift’s synthetic route [

8].

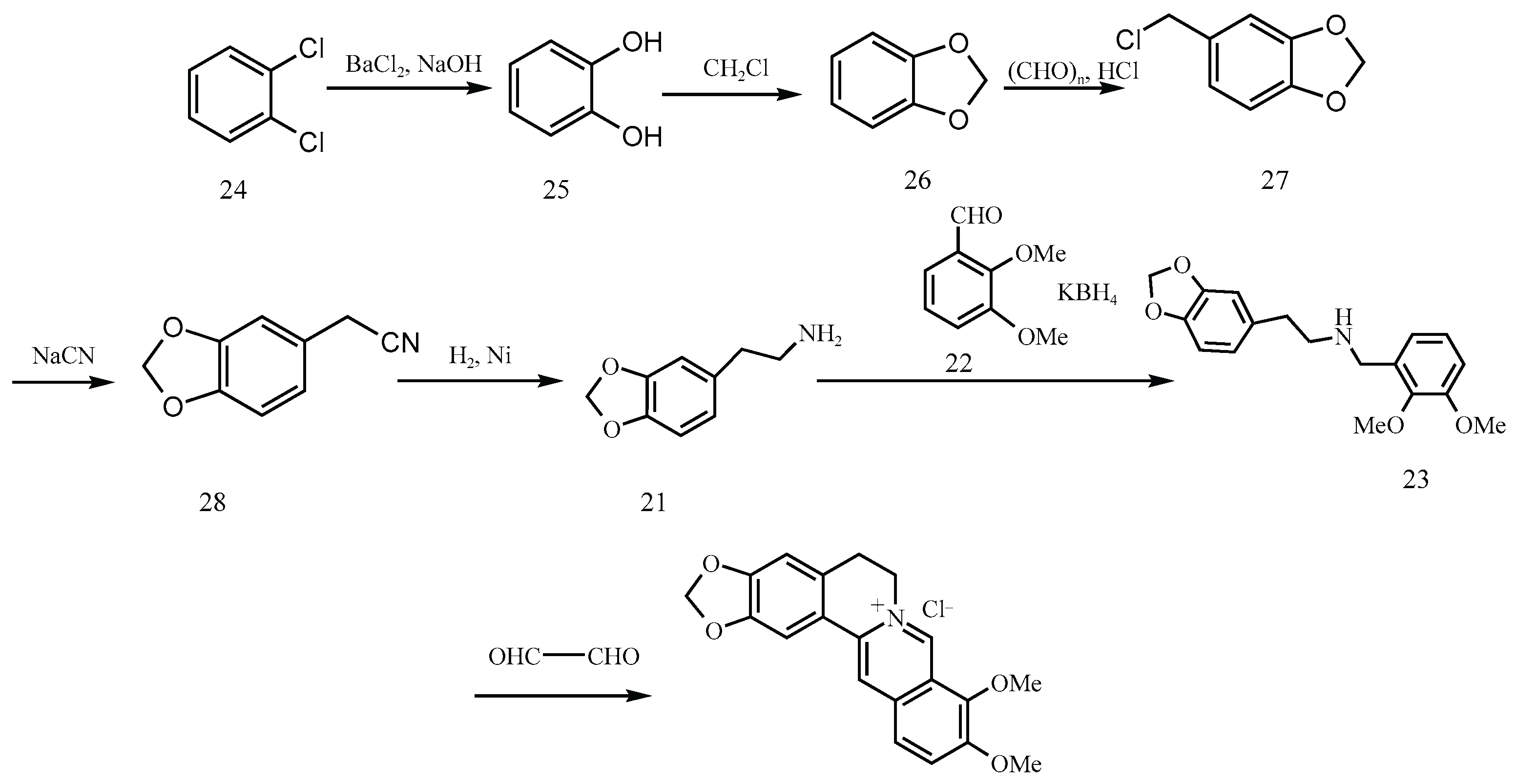

Several historical routes further exemplify this risk. For example, the 1973 Guangxi synthesis employs zinc amalgam reductions in acidic media (

Figure 9), conditions known to promote nitrosation in the presence of nitrite contaminants. Similarly, the Hangzhou First Pharmaceutical Factory’s route (

Figure 10) involves the formation of 3,4-methylenedioxyphenethylamine (Compound 21) via sodium cyanide (NaCN) substitution and subsequent hydrogenation. This compound undergoes condensation with aromatic aldehydes in the presence of Potassium Borohydride (KBH₄) to yield a β-amino alcohol intermediate, 1-(2-methoxyphenoxy)-3-(2-methoxyphenylamino)propan-2-ol (Molecule 23), a recurring secondary amine present in numerous synthetic schemes. If not fully reacted or purified, this intermediate poses a toxicity risk.

Figure 9.

Synthesis route of Guangxi Nanning pharmaceutical factory [

25].

Figure 9.

Synthesis route of Guangxi Nanning pharmaceutical factory [

25].

Figure 10.

Synthetic route of Hangzhou No. 1 pharmaceutical factory [

25].

Figure 10.

Synthetic route of Hangzhou No. 1 pharmaceutical factory [

25].

Intermediates such as Molecule 23, also reported in patents like CN106543171A, are structurally consistent with secondary amines and appear across multiple industrial routes. When exposed to acidic conditions particularly during HCl-mediated condensations or Clemensen-type reductions, such intermediates are vulnerable to nitrosation in the presence of trace nitrites.

According to FDA’s 2024 guidance, three factors facilitate nitrosamine formation: (1) a secondary or tertiary amine, (2) a nitrosating agent (e.g., trace nitrites), and (3) favorable conditions such as low pH and elevated temperature. Many berberine synthesis pathways satisfy at least two of these, even without intentionally added nitrosating agents [

30].

Given the synthesis workflow of any nutraceutical that is susceptible to nitrosamines, it becomes crucial to adopt risk-based assessments. High-sensitivity methods such as LC-MS/MS should be employed to ensure residual secondary amines and potential nitrosamines remain below regulatory thresholds (e.g., <96 ng/day for NDMA and <26.5 ng/day for NDEA, per ICH M7) [

9].

An analysis of 12 representative synthetic routes for berberine reveals that 10 involve secondary amines or reactive amine intermediates, posing an elevated risk of nitrosamine impurity formation under conditions such as low pH (<5), elevated temperatures, and the presence of trace nitrites, as outlined in the FDA’s 2024 guidance, Control of Nitrosamine Impurities in Human Drugs [

15].

Additionally, several routes involve hazardous reagents or challenging reaction conditions such as use of sodium cyanide, mercury amalgams, or pressurized hydrogenation, all of which introduce additional barriers related to consumer safety and environmental toxicity.

By contrast, newer synthetic strategies reported by Clift (

Figure 11) and Gatland (2014) utilize quaternary ammonium intermediates that are inherently resistant to nitrosation, thereby reducing risk by design. However, these methods depend on expensive palladium catalysts or non-commercial starting materials, which can limit their feasibility for large-scale manufacturing.

Figure 11.

Gatland’s synthetic route [

36].

Figure 11.

Gatland’s synthetic route [

36].

These observations underscore the need for route optimization, safer reagent selection, and the adoption of green chemistry principles.

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of key reagents, solvents, nitrosamine risk potential, and regulatory considerations across twelve commonly reported synthetic pathways for berberine.

Naturally extracted berberine from plant sources, such as

Berberis aristata or

Coptis chinensis, poses minimal risk of nitrosamine contamination because it does not involve synthetic chemical processes where nitrosating agents or amines are typically introduced [

45,

46,

47]. Unlike chemically synthesized pharmaceuticals, the extraction of berberine relies on aqueous or alcohol-based methods that are not conducive to nitrosamine formation. However, such extraction methods give a far less yield compared to synthetic methods.

4. Residual Solvent Risks in Synthetic Berberine Hydrochloride

Organic solvents play a central role in the chemical synthesis and downstream processing of berberine hydrochloride, particularly in steps such as condensation, crystallization, reduction, and purification. However, many of these solvents carry well-characterized toxicological profiles, and their presence in the final product, even in trace amounts poses significant risks to consumers. Under ICH Q3C(R8) guidelines, solvents are categorized by toxicity and acceptable daily intake [

44].

Table 2 summarizes the solvents used in major synthetic berberine routes, along with their classification and examples:

5. Natural vs. Synthetic Berberine

Berberine can be extracted from plant sources such as Berberis Aristata, Berberis Vulgaris as well as many other Berberis species using traditional methods such as water decoction, acidified water, lime milk treatment, and ethanol extraction, which are simple and inexpensive but often time-consuming and yield lower amounts of the compound [

45,

46]. Importantly, these traditional extraction approaches rely on physical and solvent-based processes rather than chemical synthesis, so they do not involve reactive intermediates such as secondary amines and therefore pose minimal risk for nitrosamine formation. This is exemplified by pressurized hot water extraction (PHWE), where plant material is extracted using only hot water under moderate pressure (around 140 °C and 50 bar) for a short period, avoiding any reactive chemical precursors or amine-based reagents [

47]. Because these methods, including PHWE, decoction, acidified water extraction, and ethanol-based extraction, are based on physical separation rather than synthetic chemistry, they inherently minimize the risk of nitrosamine contamination. However, some extraction processes particularly those using mixed or organic solvents like methanol can introduce a low-level risk related to residual solvents if purification is not rigorous, though this risk is generally far less than that associated with chemical synthesis. To improve efficiency, modern green extraction techniques have been developed, including microwave-assisted, ultrasonic-assisted, ultra-high pressure, supercritical fluid, pressurized liquid, enzymatic, and aqueous two-phase extraction [

45]. These advanced methods significantly enhance extraction yield, reduce time and solvent consumption, and help preserve the biological activity of berberine, although they require specialized equipment and higher setup costs. Ethanol and water extractions remain widely used in industry due to their simplicity, non-toxicity and food-grade nature, while newer technologies are increasingly being explored to achieve more sustainable and reproducible production.

Table 4.

Comparative Overview of Natural vs. Synthetic Berberine.

Table 4.

Comparative Overview of Natural vs. Synthetic Berberine.

| Parameter |

Natural Berberine (Plant-Derived) |

Synthetic Berberine (Chemically Synthesized) |

| Source |

Extracted from medicinal plants (Berberis, Coptis) with centuries of traditional use |

Produced via multistep chemical synthesis using petrochemical-derived precursors |

| Yield |

Low yield but derived from renewable, biogenic sources |

High yield but dependent on synthetic efficiency and raw material availability |

| Purity |

Requires purification, but typically free from synthetic byproducts |

High assay purity, but may harbor trace-level synthetic impurities such as nitrosamines |

| Toxic Impurity Risk |

Low risk; water/ethanol-based extraction avoids nitrosamine formation |

Elevated risk: nitrosamines, residual solvents, and unreacted intermediates can persist if not rigorously controlled |

| Nitrosamine Risk (FDA 2024 Guidance) |

Negligible under aqueous, alcoholic and acid-base extraction conditions |

Notable concern: many synthetic routes can lead to nitrosamine formation unless mitigated |

| Process Solvents |

Water, Ethanol, methanol, environmentally benign (Except methanol) and food-grade |

Involves organic solvents (e.g., dichloromethane, toluene), which may require stringent residue control |

| Consumer Perception |

Viewed as holistic, natural, and safer for long-term use |

Increasing concern over “lab-made” compounds and hidden risks among informed consumers |

| Environmental Impact |

Lower carbon and chemical footprint if sustainably harvested |

Higher impact unless green chemistry principles and solvent recovery are employed |

| Cost Efficiency |

Higher per-gram cost, but offset by holistic composition and perceived safety |

Lower cost per gram, but potential trade-offs in safety and public trust |

6. Discussion

The widespread use of berberine in nutraceuticals has brought growing attention to the differences between synthetic and natural sources, particularly regarding safety, regulatory oversight, and consumer perception. Synthetic berberine offers clear advantages in terms of cost efficiency, scalability, and process reproducibility, however, it is frequently associated with a range of safety risks stemming from the use of hazardous chemical intermediates and solvents. Many reported synthetic routes involve secondary or tertiary amines such as piperidine, that can react under acidic conditions to form potentially carcinogenic nitrosamines. Similarly, the use of solvents like benzene, dichloromethane, or methanol introduces the risk of residual solvent contamination if not properly removed.

In contrast, natural berberine which is typically extracted from roots of Berberine-containing plant species using solvents like water or ethanol, avoids nitrosamine-prone intermediates and tends to have none or much lower residual toxicity burdens. Additionally, natural extracts can preserve the broader phytochemical profile of the plant. Despite challenges such as lower yields, seasonal variability in plant biomass, and higher processing costs, natural extraction aligns more closely with consumer expectations for transparency, safety, and efficacy.

The debate between natural and synthetic sourcing in nutraceuticals is not unique to berberine. The curcumin industry has faced similar challenges, where synthetic curcumin, often derived from petrochemicals, has been fraudulently marketed as plant-derived [

48]. This has prompted the development of advanced authenticity tools, including carbon-14 radiocarbon dating, isotope ratio analysis, and metabolomic fingerprinting, to verify the botanical origin of curcumin. These tools not only protect consumers from misleading claims but can also help ensure that natural products retain the full spectrum of bioactive compounds. In the case of berberine, the same concerns apply; synthetic versions lack the complex chemical fingerprint of the plant matrix and may carry undetected impurities like nitrosamines or residual solvents.

As the industry moves forward, several key recommendations can help close these safety gaps. Manufacturers synthesizing nutraceuticals using chemical pathways that could be susceptible to nitrosamine formation should conduct formal nitrosamine risk assessments as per ICH M7, and regularly audit synthetic pathways to eliminate high-risk reagents or steps. Regulatory authorities should mandate clear labeling of berberine origin, synthetic or natural, to enhance consumer trust and enforce transparency.

In summary, while synthetic berberine is a cheaper alternative, it must meet rigorous impurity control standards to be considered safe for long-term human use. Natural berberine, though more costly, presents fewer safety concerns. By learning from cases like curcumin and adopting science-driven authentication and quality control, the nutraceutical sector can ensure that berberine products, regardless of source are safe, effective, and transparent to the end consumer.

7. Conclusion

The increasing use of synthetic bioactives in the nutraceutical sector, exemplified by the case of berberine highlights a critical gap in transparency and safety. While synthetic berberine hydrochloride offers advantages in scalability and cost, it presents significant concerns related to nitrosamine formation and residual solvent contamination.

In contrast, naturally extracted berberine from botanical sources aligns more closely with clean-label expectations and demonstrates a lower toxicological burden. Although its production is costlier, natural berberine provides a safer, more holistic alternative, especially important in a health-conscious consumer market increasingly demanding authenticity transparency and sustainability.

To ensure the long-term safety and credibility of berberine-containing products, the nutraceutical industry must adopt a more rigorous and science-driven approach. To support long term safety, synthetic manufacturing of nutraceuticals should proactively address the potential for toxic impurities, particularly nitrosamine contamination, by optimizing synthesis workflows and minimizing the use of high-risk reagents. Additionally, to support natural origin claims, manufacturers should implement advanced source verification methods such as radiocarbon dating. Lessons from the curcumin industry should serve as a cautionary framework: when synthetic analogs are introduced without adequate safeguards, consumer trust is compromised, and long-term risks may go unnoticed.

Author Contributions

AM, MK, and AZ jointly conceived the study, conducted the literature search, organized the content, drafted the manuscript, and performed proofreading. All authors contributed equally to all aspects of the work and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data availability Statement

No new data was created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grycová, L.; Dostál, J.; Marek, R. Quaternary Protoberberine Alkaloids. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 150–175. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zou, D.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Zhu, N.; Huo, L.; Wang, M.; Hong, J.; Wu, P.; Zhang, M. Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes and Dyslipidemia with the Natural Plant Alkaloid Berberine. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 2559–2565. [CrossRef]

- Imanshahidi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Pharmacological and Therapeutic Effects of Berberis spp. and Its Active Constituent, Berberine. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 999–1012. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Xing, H.; Ye, J. Efficacy of Berberine in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Metabolism 2008, 57, 712–717. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. S.; Kim, W. S.; Kim, K. H.; Yoon, M. J.; Cho, H. J.; Shen, Y.; Ye, J. M.; Lee, Y. L.; Kim, J. W.; Kim, J. B. Berberine, a Natural Plant Product, Activates AMP-Activated Protein Kinase with Beneficial Metabolic Effects in Diabetic and Insulin-Resistant States. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2256–2264. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, J.; Xue, R.; Wu, J. D.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z. Z.; Wang, S. K.; Zhou, Z. X.; Song, D. Q.; Wang, Y. M.; Pan, H. N.; Kong, W. J.; Jiang, J. D.; Zhou, D. S. Berberine Lowers Blood Glucose in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients through Increasing Insulin Receptor Expression. Metabolism 2010, 59, 285–292. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.; Fischer, T.; Upjohn, L.; Mazzera, D.; Kumar, M. Unapproved Pharmaceutical Ingredients Included in Dietary Supplements Associated with US Food and Drug Administration Warnings. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e183337. [CrossRef]

- Mori-Quiroz, L. M.; Hedrick, S. L.; De Los Santos, A. R.; Clift, M. D. A Unified Strategy for the Syntheses of the Isoquinolinium Alkaloids Berberine, Coptisine, and Jatrorrhizine. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 4281–4284. [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Some N-Nitroso Compounds. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; IARC: Lyon, France, 1978; Volume 17. Available online: https://publications.iarc.fr/35 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). M7(R2): Assessment and Control of DNA Reactive (Mutagenic) Impurities in Pharmaceuticals to Limit Potential Carcinogenic Risk; ICH Harmonised Guideline: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.ich.org/page/multidisciplinary-guidelines (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Control of Nitrosamine Impurities in Human Drugs: Guidance for Industry; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/141720/download (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). Patent CN106543171A, 2017. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN106543171A/en (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). Patent CN113735847A, 2021. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN113735847A/en (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Mitch, W. A.; Sharp, J. O.; Trussell, R. R.; Valentine, R. L.; Alvarez-Cohen, L.; Sedlak, D. L. N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) as a Drinking Water Contaminant: A Review. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2003, 20, 389–404. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Information about Nitrosamine Impurities in Medications, 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/information-about-nitrosamine-impurities-medications (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Bharate, S. S. Critical Analysis of Drug Product Recalls Due to Nitrosamine Impurities. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 2923–2936. [CrossRef]

- Shephard EA, Nawarskas JJ. Nitrosamine Impurities in Angiotensin Receptor Blockers. Cardiol Rev. 2020 Sep/Oct;28(5):262-265. PMID: 32467427. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y, Teo J, Lim JQ, Hoi WK, Kee CL, Low MY, Ge X. Determination of N-nitroso folic acid in folic acid and multivitamin supplements by LC-MS/MS. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2024 Jan;41(1):1-8. Epub 2024 Jan 17. PMID: 38100531. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, J. S.; Thakur, R. Nitrosamine Impurities in Herbal Formulations: A Review of Risks and Mitigation Strategies. Drug Res. 2023, 73, 327–336. [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Questions and Answers on Nitrosamine Impurities in Herbal Medicinal Products, 2022. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/questions-answers-nitrosamine-impurities-herbal-medicinal-products_en.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Q3C(R8): Impurities: Guideline for Residual Solvents, 2021. Available online: https://www.ich.org/page/quality-guidelines (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Teasdale, A.; Elder, D.; Harvey, J. Residual Solvents in Pharmaceuticals: A Practical Guide to ICH Q3C. Pharm. Technol. 2018, 42, 28–34. Available online: https://www.pharmtech.com/view/residual-solvents-pharmaceuticals-practical-guide-ich-q3c (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, 1994. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements/dietary-supplement-health-and-education-act-1994 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Pawar, R. S.; Grundel, E. Overview of Regulation of Dietary Supplements in the USA and Issues of Adulteration with Phenethylamines (PEAs). Drug Test. Anal. 2017, 9, 500–517. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Summary of Total Synthesis of Berberine. Hans J. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2020, 10, 306–313. [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Some Chemicals Used as Solvents and in Polymer Manufacture. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; IARC: Lyon, France, 2016; Volume 110. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono110.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Kamendulis, L. M.; Klaunig, J. E. Species Differences in the Induction of Hepatocellular DNA Synthesis by Catechol. Toxicol. Sci. 2005, 87, 398–406. [CrossRef]

- He XG. On-line identification of phytochemical constituents in botanical extracts by combined high-performance liquid chromatographic-diode array detection-mass spectrometric techniques. J Chromatogr A. 2000 Jun 2;880(1-2):203-32. PMID: 10890521. [CrossRef]

- Beta Analytic. Turmeric Case Study: Verifying “Natural” Claims by Carbon-14 and HPLC Analyses. Beta Lab Services, 2021. Available online: https://www.betalabservices.com/turmeric-hplc-carbon-14-testing/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Control of Nitrosamine Impurities in Human Drugs: Guidance for Industry; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/141720/download (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Pictet, A.; Gams, A. Synthese des Berberins. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1911, 44, 2480–2485. [CrossRef]

- Kametani, T.; Noguchi, I. Studies on the Syntheses of Heterocyclic Compounds. Part CCCII. Alternative Total Syntheses of (±)-Nandinine, (±)-Canadine, and Berberine Iodide. J. Chem. Soc. C 1969, 15, 2036–2038. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.; Jadhav, A. S.; Anand, R. V. A Room-Temperature Protocol to Access Isoquinolines through Ag(I) Catalysed Annulation of O-(1-Alkynyl) Arylaldehydes and Ketones with NH4OAc: Elaboration to Berberine and Palmatine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 3732–3741. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Tong, R. A General, Concise Strategy That Enables Collective Total Syntheses of over 50 Protoberberine and Five Aporhoeadane Alkaloids within Four to Eight Steps. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 7084–7089. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Requests Removal of All Ranitidine Products (Zantac) from the Market, 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-requests-removal-all-ranitidine-products-zantac-market (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Gatland, A. E.; Pilgrim, B. S.; Procopiou, P. A.; Donohoe, T. J. Short and Efficient Syntheses of Protoberberine Alkaloids Using Palladium-Catalyzed Enolate Arylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14555–14558. [CrossRef]

- Kametani, T.; Noguchi, I. Studies on the Syntheses of Heterocyclic Compounds. Part CCCII. Alternative Total Syntheses of (±)-Nandinine, (±)-Canadine, and Berberine Iodide. J. Chem. Soc. C 1969, 15, 2036–2038. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Luo, Z.; Yang, H.; Feng, Y. Study on the Synthesis of Berberine Hydrochloride. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 36, 1426–1430.

- Chen, C.; Xu, M.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, C.; Yang, H.; Feng, Y. Convergent Synthesis of Berberine Hydrochloride. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 37, 503–507.

- Tajiri, M.; Yamada, R.; Hotsumi, M.; Makabe, K.; Konno, H. The Total Synthesis of Berberine and Selected Analogues, and Their Evaluation as Amyloid Beta Aggregation Inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 215, 113289. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, W.-D. Z. Concise Total Syntheses of Berberine and Its Analogues Enabled by Trifluoroacetic Anhydride-Promoted Decarbonylative-Elimination Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2023, 132, 154826. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lin, W.; Zang, J.; Liu, J.; Qi, S.; Zhang, L.; Song, G. Preparation of Berberine and Its Salts. Chinese Patent CN1164588C, 2004. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN1164588C/en (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). Patent CN101245064B. Available online: https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/1d/14/31/39193570566bee/CN101245064B.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). ICH Q3C(R8): Impurities: Guideline for Residual Solvents; ICH Harmonised Guideline: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q3C-R8-Guideline-Step4-2021-04-22.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Huang S, Huang G. A comprehensive review of recent advances in the extraction and therapeutic potential of berberine. RSC Adv. 2025 Jul 14;15(30):24596-24611. PMID: 40661201; PMCID: PMC12257298. [CrossRef]

- Neag MA, Mocan A, Echeverría J, Pop RM, Bocsan CI, Crişan G, Buzoianu AD. Berberine: Botanical Occurrence, Traditional Uses, Extraction Methods, and Relevance in Cardiovascular, Metabolic, Hepatic, and Renal Disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Aug 21;9:557. PMID: 30186157; PMCID: PMC6111450. [CrossRef]

- Mokgadi, J. , Turner, C. and Torto, N. (2013) Pressurized Hot Water Extraction of Alkaloids in Goldenseal. American Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 4, 398-403. [CrossRef]

- You H, Gershon H, Goren F, Xue F, Kantowski T, Monheit L. Analytical strategies to determine the labelling accuracy and economically-motivated adulteration of “natural” dietary supplements in the marketplace: Turmeric case study. Food Chem. 2022 Feb 15;370:131007. Epub 2021 Sep 1. PMID: 34507212. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).