Submitted:

14 June 2023

Posted:

25 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Extraction and Isolation

2.3. Cell Culture

2.4. Treatment of Cells with PM10

2.5. Cell Viability Assay

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.7. Assay for Cellular ROS Production

2.8. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

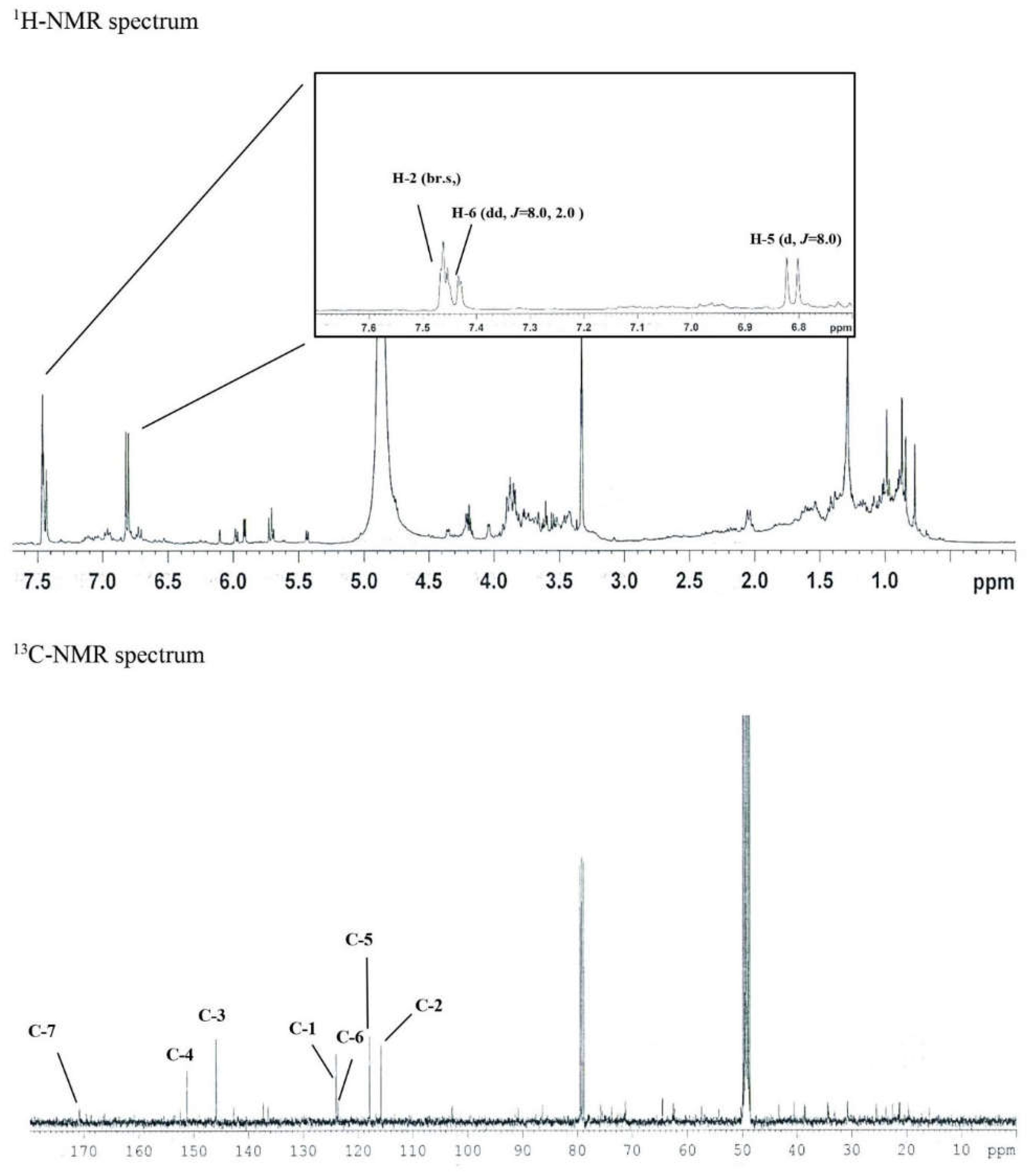

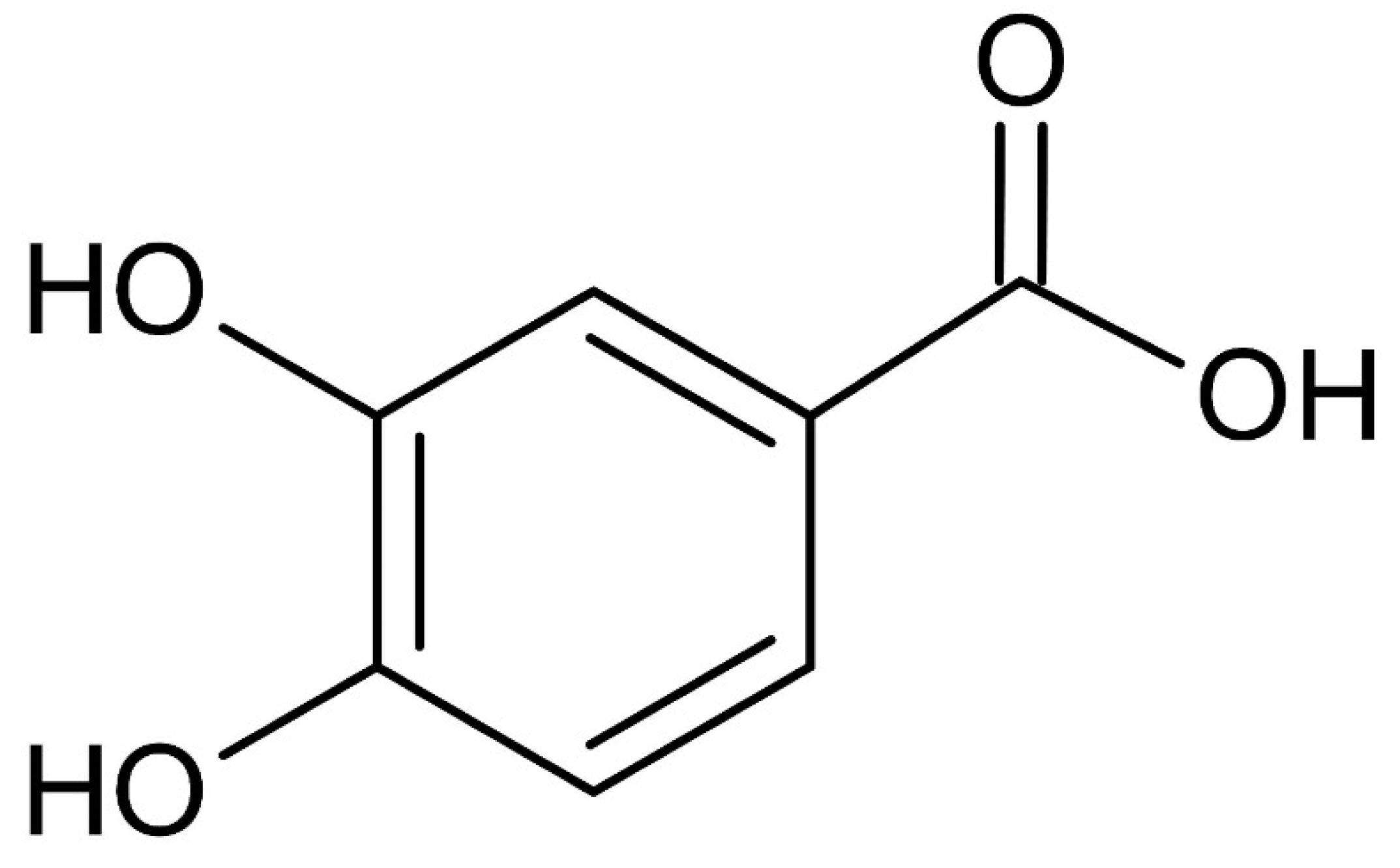

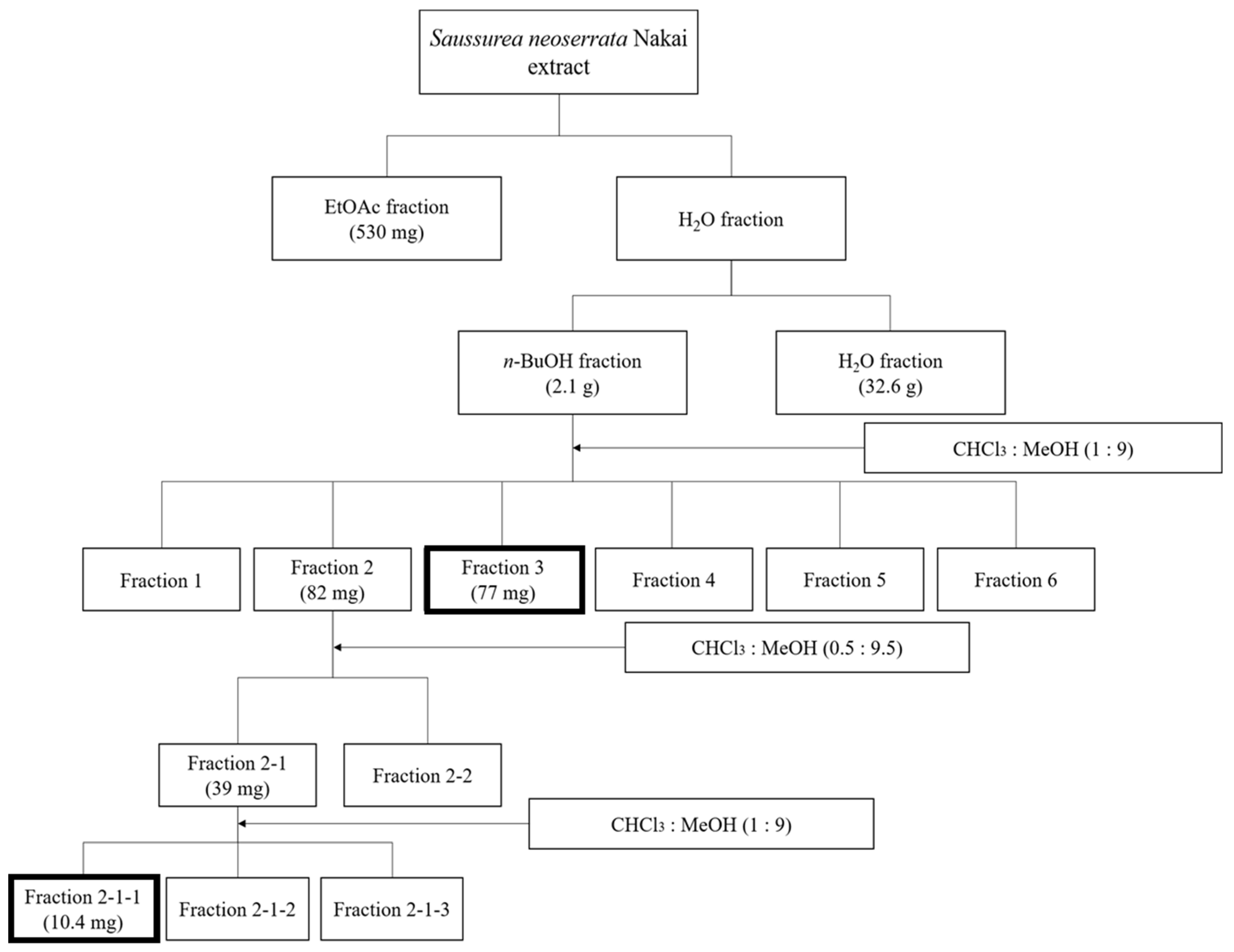

3.1. Purification of Protocatechuic Acid from S. neoserrata Nakai

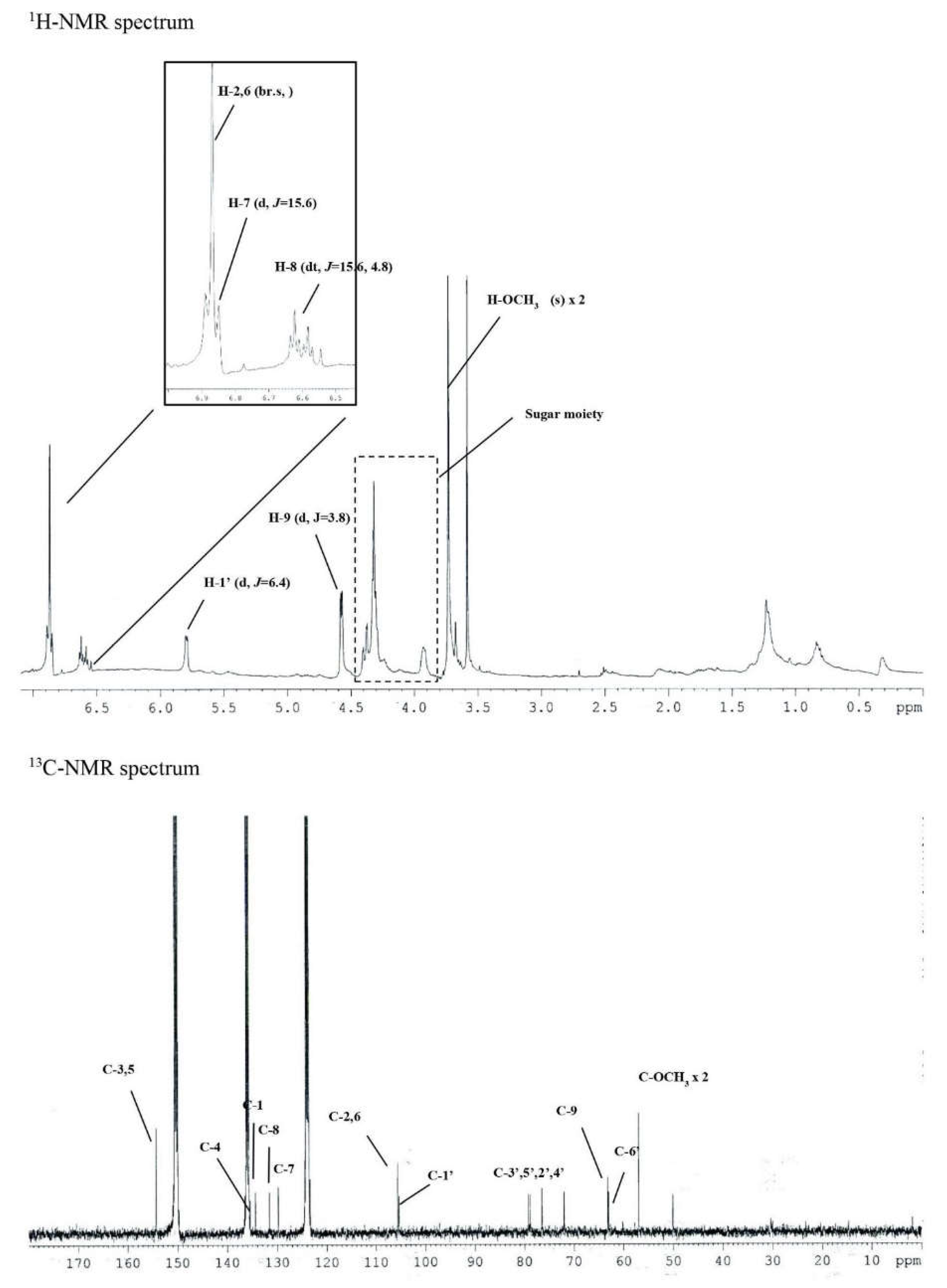

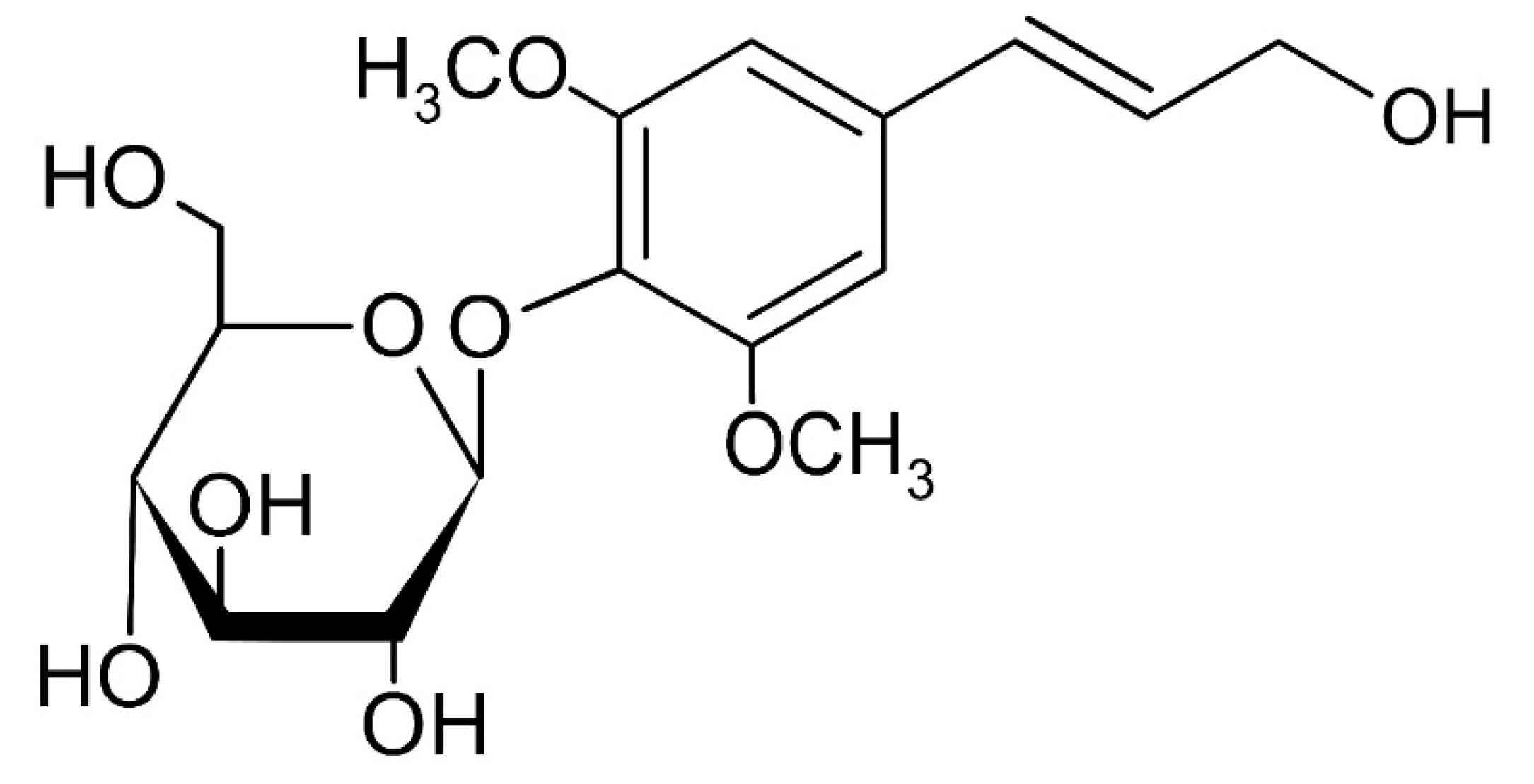

3.2. Purification of Syringin from S. neoserrata Nakai

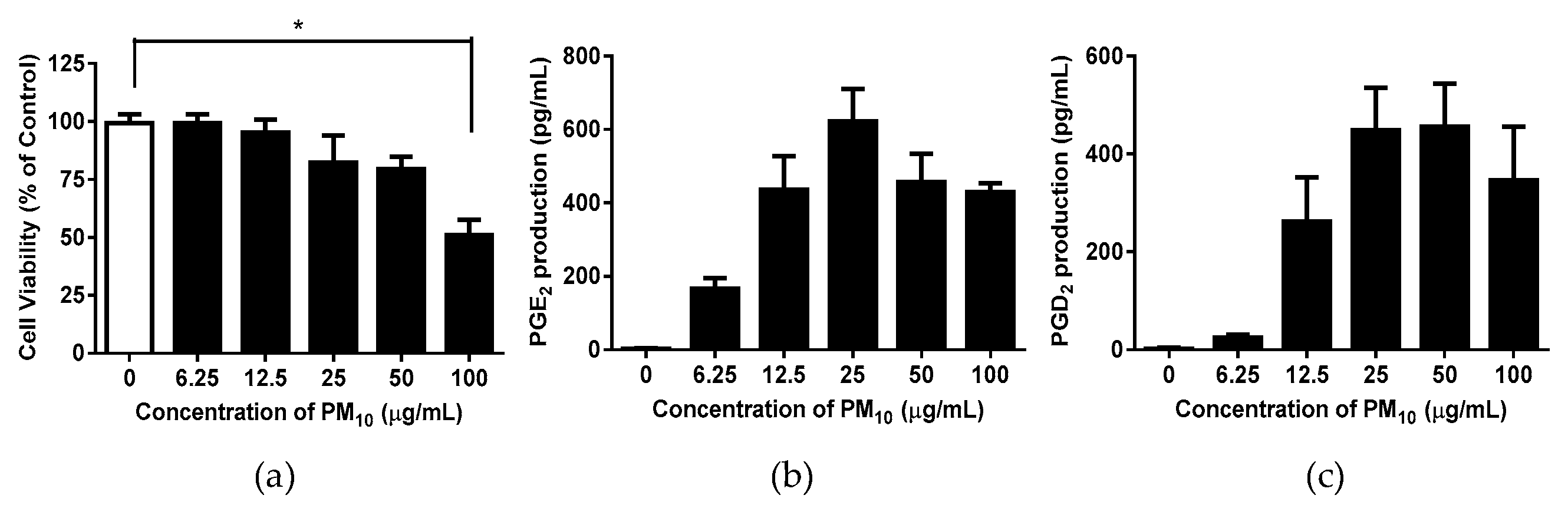

3.3. PM10 Induces Cytotoxicity in and PGE2 and PGD2 Release from Keratinocytes

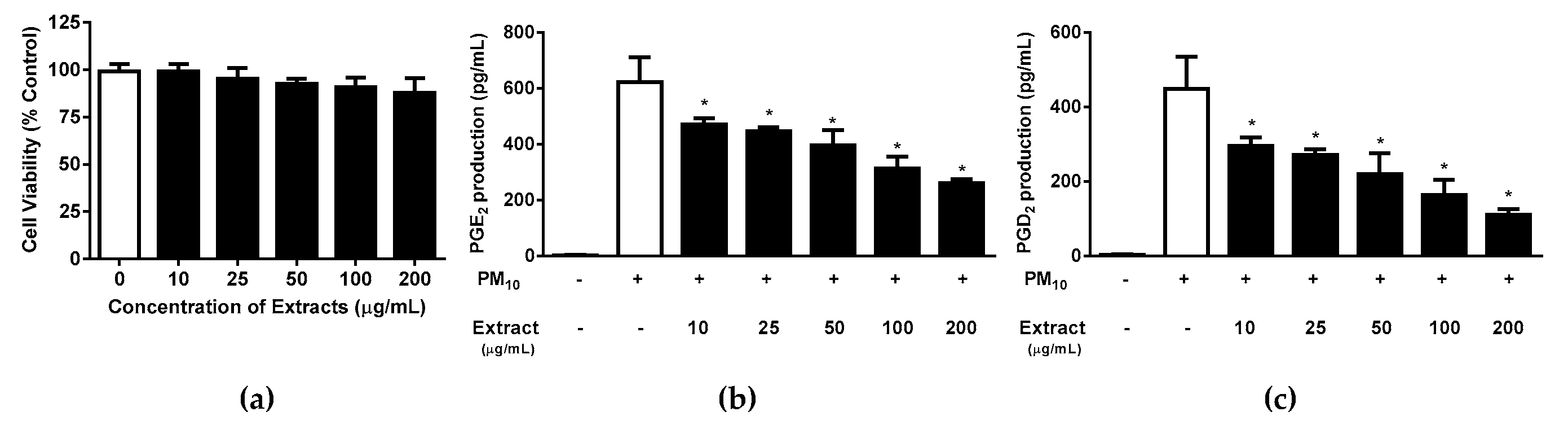

3.4. Effects of S. neoserrata Nakai Extracts on PM10-Induced Cytotoxicity and PGE2 and PGD2 Release

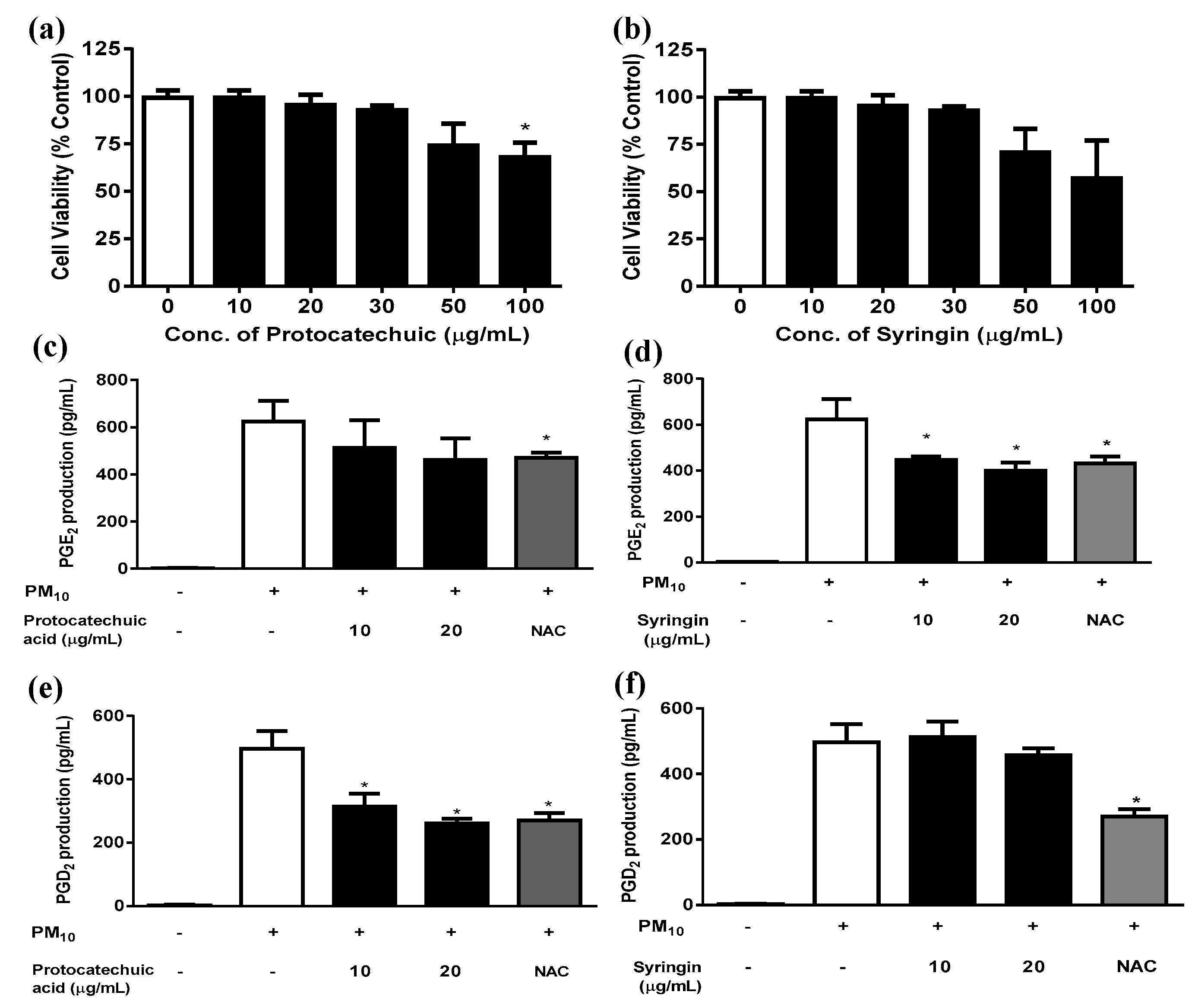

3.5. Effects of Protocatechuic Acid and Syringin on PM10-Induced Keratinocyte Cytotoxicity and PGE2 and PGD2 Release

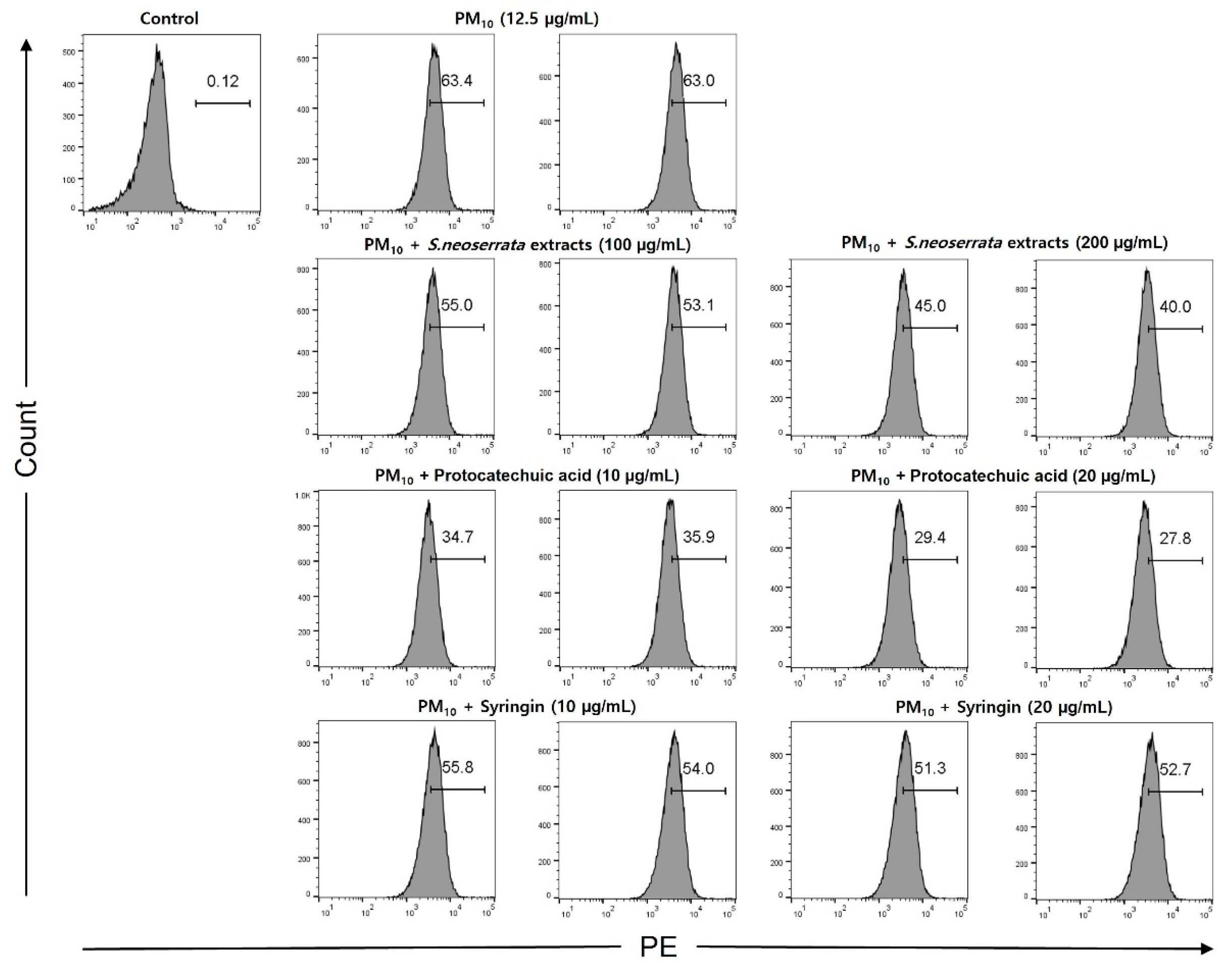

3.6. Effects of Protocatechuic Acid and Syringin on PM10-Induced ROS Production

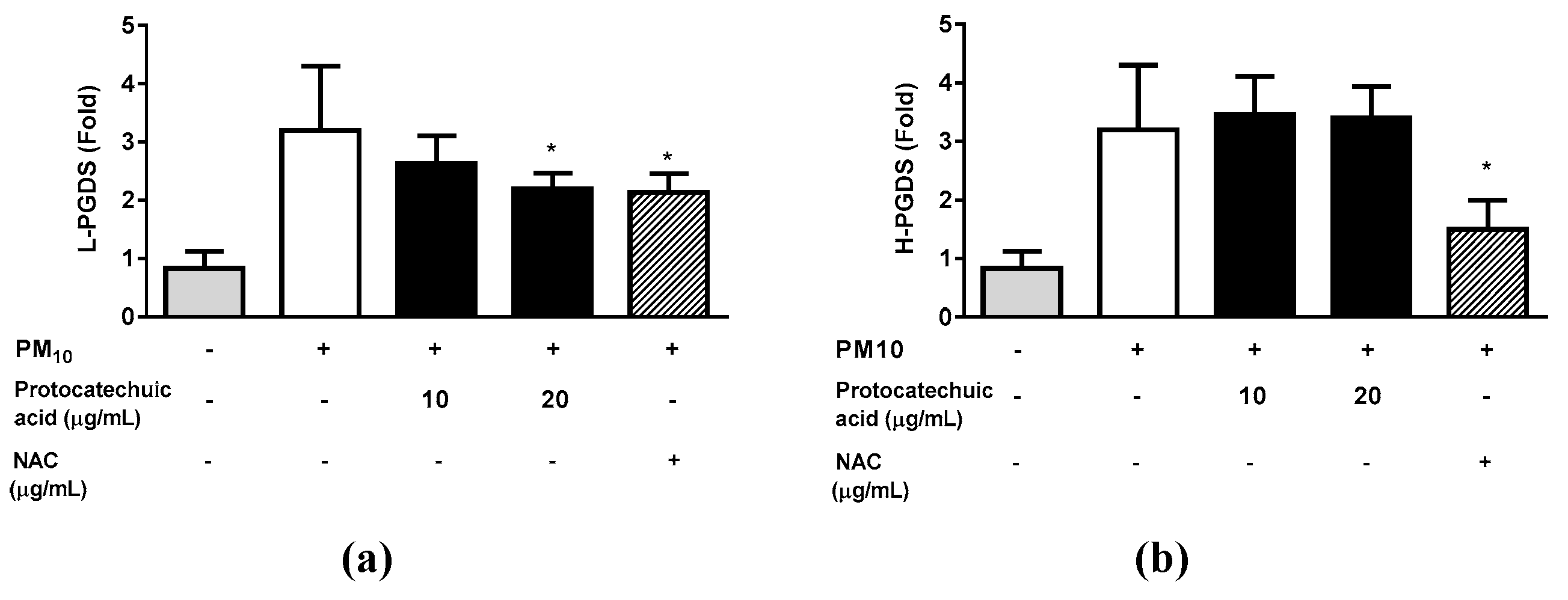

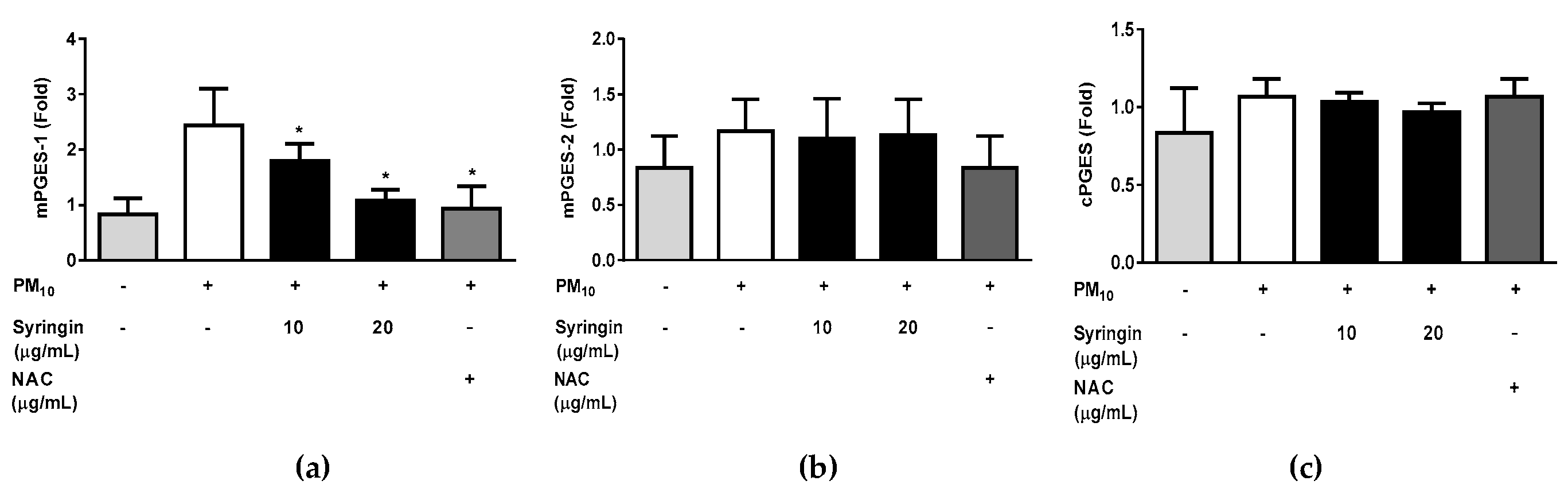

3.7. Effects of Protocatechuic Acid and Syringin on the PM10-Induced Gene Expression of the Enzymes Involved in the PGE2 and PGD2 Synthesis

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krzyzanowski, M. WHO air quality guidelines for Europe. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 2008, 71, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.-Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, T. Toxicity research of PM2. 5 compositions in vitro. International journal of environmental research and public health 2017, 14, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momtazan, M.; Geravandi, S.; Rastegarimehr, B.; Valipour, A.; Ranjbarzadeh, A.; Yari, A.R.; Dobaradaran, S.; Bostan, H.; Farhadi, M.; Darabi, F. An investigation of particulate matter and relevant cardiovascular risks in Abadan and Khorramshahr in 2014–2016. Toxin reviews 2019, 38, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriyari, H.A.; Nikmanesh, Y.; Jalali, S.; Tahery, N.; Zhiani Fard, A.; Hatamzadeh, N.; Zarea, K.; Cheraghi, M.; Mohammadi, M.J. Air pollution and human health risks: mechanisms and clinical manifestations of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Toxin Reviews 2022, 41, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobaradaran, S.; Geravandi, S.; Goudarzi, G.; Idani, E.; Salmanzadeh, S.; Soltani, F.; Yari, A.R.; Mohammadi, M.J. Determination of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases caused by PM10 exposure in Bushehr, 2013. Journal of Mazandaran university of medical sciences 2016, 26, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bakke, J.V.; Wieslander, G.; Norback, D.; Moen, B.E. Eczema increases susceptibility to PM10 in office indoor environments. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health 2012, 67, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.-P.; Li, Z.; Choi, E.K.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.K.; Seo, E.Y.; Chung, J.H.; Cho, S. Urban particulate matter in air pollution penetrates into the barrier-disrupted skin and produces ROS-dependent cutaneous inflammatory response in vivo. Journal of dermatological science 2018, 91, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.-L.; Wang, P.-W.; Aljuffali, I.A.; Huang, C.-T.; Lee, C.-W.; Fang, J.-Y. The impact of urban particulate pollution on skin barrier function and the subsequent drug absorption. Journal of dermatological science 2015, 78, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, K. The role of air pollutants in atopic dermatitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2014, 134, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierkötter, A.; Schikowski, T.; Ranft, U.; Sugiri, D.; Matsui, M.; Krämer, U.; Krutmann, J. Airborne particle exposure and extrinsic skin aging. Journal of investigative dermatology 2010, 130, 2719–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.E. Pollution as a risk factor for the development of melasma and other skin disorders of facial hyperpigmentation-is there a case to be made? Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD 2015, 14, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martic, I.; Jansen-Dürr, P.; Cavinato, M. Effects of air pollution on cellular senescence and skin aging. Cells 2022, 11, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soeur, J.; Belaïdi, J.-P.; Chollet, C.; Denat, L.; Dimitrov, A.; Jones, C.; Perez, P.; Zanini, M.; Zobiri, O.; Mezzache, S. Photo-pollution stress in skin: Traces of pollutants (PAH and particulate matter) impair redox homeostasis in keratinocytes exposed to UVA1. Journal of dermatological science 2017, 86, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, D.; Jin, M.; Bai, C.; Song, Y. Urban particulate matter triggers lung inflammation via the ROS-MAPK-NF-κB signaling pathway. Journal of thoracic disease 2017, 9, 4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Kovochich, M.; Nel, A. The role of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in mediating particulate matter injury. Clin Occup Environ Med 2006, 5, 817–836. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.-Y.; Byun, E.J.; Lee, J.D.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.S. Air pollution, autophagy, and skin aging: impact of particulate matter (PM10) on human dermal fibroblasts. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Cervellati, C.; Muresan, X.M.; Belmonte, G.; Pecorelli, A.; Cervellati, F.; Benedusi, M.; Evelson, P.; Valacchi, G. Keratinocytes oxidative damage mechanisms related to airbone particle matter exposure. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2018, 172, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-W.; Lin, Z.-C.; Hu, S.C.-S.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Hsu, L.-F.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lee, I.-T.; Tsai, M.-H.; Fang, J.-Y. Urban particulate matter down-regulates filaggrin via COX2 expression/PGE2 production leading to skin barrier dysfunction. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 27995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, L.; Li, J. The inhibitory effect of resveratrol on COX-2 expression in human colorectal cancer: A promising therapeutic strategy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017, 21, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Cianciulli, A.; Calvello, R.; Cavallo, P.; Dragone, T.; Carofiglio, V.; Panaro, M.A. Modulation of NF-κB activation by resveratrol in LPS treated human intestinal cells results in downregulation of PGE2 production and COX-2 expression. Toxicology in Vitro 2012, 26, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-H.; Hsu, L.-F.; Lee, C.-W.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Lee, M.-H.; How, J.-M.; Wu, C.-M.; Huang, C.-L.; Lee, I.-T. Resveratrol inhibits urban particulate matter-induced COX-2/PGE2 release in human fibroblast-like synoviocytes via the inhibition of activation of NADPH oxidase/ROS/NF-κB. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2017, 88, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-W.; Lin, Z.-C.; Hsu, L.-F.; Fang, J.-Y.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Tsai, M.-H.; Lee, M.-H.; Li, S.-Y.; Hu, S.C.-S.; Lee, I.-T. Eupafolin ameliorates COX-2 expression and PGE2 production in particulate pollutants-exposed human keratinocytes through ROS/MAPKs pathways. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2016, 189, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.C. Can plant phenolic compounds protect the skin from airborne particulate matter? Antioxidants 2019, 8, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliano, C.; Magrini, G.A. Cosmetic functional ingredients from botanical sources for anti-pollution skincare products. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. Plant-derived antioxidants: Significance in skin health and the ageing process. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.K. Medicinal plants: Future source of new drugs. International journal of herbal medicine 2016, 4, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Süntar, I. Importance of ethnopharmacological studies in drug discovery: role of medicinal plants. Phytochemistry Reviews 2020, 19, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Li, S.-J.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Zhang, M.-L.; Shi, Q.-W.; Gu, Y.-C.; Dong, M.; Kiyota, H. Chemical constituents from the genus Saussurea and their biological activities. Heterocyclic Communications 2017, 23, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.P.; Saklani, S.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Iriti, M.; Salehi, B.; Maurya, V.K.; Rauf, A.; Milella, L.; Rajabi, S.; Baghalpour, N. Antibacterial potential of Saussurea obvallata petroleum ether extract: A spiritually revered medicinal plant. Cellular and Molecular Biology 2018, 64, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.-Q.; Yue, J.-M. Biologically active phenols from Saussurea medusa. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 2003, 11, 703–708. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.T.; Im, H.T. Saussurea grandicapitula W. Lee et HT Im (Compositae), a new species from the Taebaek mountains, Korea. Korean Journal of Plant Taxonomy 2007, 37, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Li, Z. Blueberries inhibit cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 activity in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncology Letters 2017, 13, 4897–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wu, W.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L. Berberine alleviates amyloid β25-35-induced inflammatory response in human neuroblastoma cells by inhibiting proinflammatory factors. Experimental and therapeutic medicine 2018, 16, 4865–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molloy, E.; Morgan, M.; Doherty, G.; McDonnell, B.; O'Byrne, J.; Fitzgerald, D.; McCarthy, G. Microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase 1 expression in basic calcium phosphate crystal-stimulated fibroblasts: role of prostaglandin E2 and the EP4 receptor. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2009, 17, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, N.; Li, X.; Chabane, N.; Benderdour, M.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Pelletier, J.-P.; Duval, N.; Fahmi, H. Increased expression of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D 2 synthase in osteoarthritic cartilage. Arthritis research & therapy 2008, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-w.; Seok, J.K.; Boo, Y.C. Ecklonia cava extract and dieckol attenuate cellular lipid peroxidation in keratinocytes exposed to PM10. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, S.; Bais, S. A review on protocatechuic acid and its pharmacological potential. International Scholarly Research Notices 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.H. Potential synergy of phytochemicals in cancer prevention: mechanism of action. The Journal of nutrition 2004, 134, 3479S–3485S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, A.N.; Brenner, M.C.; Punessen, N.; Snodgrass, M.; Byars, C.; Arora, Y.; Linseman, D.A. Comparison of the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of the anthocyanin metabolites, protocatechuic acid and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, D.R. The lipocalin protein family: structure and function. Biochemical journal 1996, 318, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urade, Y.; Kitahama, K.; Ohishi, H.; Kaneko, T.; Mizuno, N.; Hayaishi, O. Dominant expression of mRNA for prostaglandin D synthase in leptomeninges, choroid plexus, and oligodendrocytes of the adult rat brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 9070–9074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Ogawa, K.; Sugamura, K.; Nakamura, M.; Takano, S.; Nagata, K. Cutting edge: differential production of prostaglandin D2 by human helper T cell subsets. The Journal of Immunology 2000, 164, 2277–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urade, Y.; Ujihara, M.; Horiguchi, Y.; Igarashi, M.; Nagata, A.; Ikai, K.; Hayaishi, O. Mast cells contain spleen-type prostaglandin D synthetase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1990, 265, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaoka, Y.; Urade, Y. Hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes and essential fatty acids 2003, 69, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettipher, R. The roles of the prostaglandin D2 receptors DP1 and CRTH2 in promoting allergic responses. British journal of pharmacology 2008, 153, S191–S199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Moroi, R.; Aritake, K.; Urade, Y.; Kanai, Y.; Sumi, K.; Yokozeki, H.; Hirai, H.; Nagata, K.; Hara, T. Prostaglandin D2 plays an essential role in chronic allergic inflammation of the skin via CRTH2 receptor. The Journal of Immunology 2006, 177, 2621–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, N.; Murakami, M.; Tanioka, T.; Fujimori, K.; Tanabe, T.; Urade, Y.; Kudo, I. Coupling between cyclooxygenase, terminal prostanoid synthase, and phospholipase A2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 34918–34927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidar, N.; Odar, K.; Glavac, D.; Jerse, M.; Zupanc, T.; Stajer, D. Cyclooxygenase in normal human tissues–is COX-1 really a constitutive isoform, and COX-2 an inducible isoform? Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2009, 13, 3753–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, S.; Tuominen, H.; Koivukangas, J.; Stenbäck, F. The terminal prostaglandin synthases mPGES-1, mPGES-2, and cPGES are all overexpressed in human gliomas. Neuropathology 2009, 29, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, M.; Gerboles, E.; ESCUDERO, J.R.; Anton, R.; Garcia-Moll, X.; Vila, L. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1, which is not coupled to a particular cyclooxygenase isoenzyme, is essential for prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2007, 5, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, M.-S.; Hyun, C.-K. Syringin attenuates insulin resistance via adiponectin-mediated suppression of low-grade chronic inflammation and ER stress in high-fat diet-fed mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2017, 488, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Huang, C.-W.; Chang, P.-C.; Shiau, J.-P.; Lin, I.-P.; Lin, M.-Y.; Lai, C.-C.; Chen, C.-Y. Reactive oxygen species mediate the chemopreventive effects of syringin in breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine 2019, 61, 152844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lall, N.; Kishore, N.; Binneman, B.; Twilley, D.; Van de Venter, M.; Plessis-Stoman, D.d.; Boukes, G.; Hussein, A. Cytotoxicity of syringin and 4-methoxycinnamyl alcohol isolated from Foeniculum vulgare on selected human cell lines. Natural product research 2015, 29, 1752–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Luo, J.; Meng, C.; Jiang, N.; Cao, J.; Zhao, J. Syringin exerts neuroprotective effects in a rat model of cerebral ischemia through the FOXO3a/NF-κB pathway. International Immunopharmacology 2021, 90, 107268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, K.; Stone, V. Current hypotheses on the mechanisms of toxicity of ultrafine particles. Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanità 2003, 39, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Araujo, J.A.; Nel, A.E. Particulate matter and atherosclerosis: role of particle size, composition and oxidative stress. Particle and fibre toxicology 2009, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S. Particulate matter, air pollution, and blood pressure. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension 2009, 3, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.-T.; Yang, C.-M. Role of NADPH oxidase/ROS in pro-inflammatory mediators-induced airway and pulmonary diseases. Biochemical pharmacology 2012, 84, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, K.; Krause, K.-H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiological reviews 2007, 87, 245–313. [Google Scholar]

- Lassègue, B.; Griendling, K.K. NADPH oxidases: functions and pathologies in the vasculature. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2010, 30, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.K.; Choi, M.A.; Ha, J.W.; Boo, Y.C. Role of dual oxidase 2 in reactive oxygen species production induced by airborne particulate matter PM10 in human epidermal keratinocytes. Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Scientists of Korea 2019, 45, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.-M.; Lee, P.-H.; An, M.-H.; Yun-Gi, L.; Park, S.; Baek, A.R.; Jang, A.-S. N-acetylcysteine decreases lung inflammation and fibrosis by modulating ROS and Nrf2 in mice model exposed to particulate matter. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology 2022, 44, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Ni, J.; Tao, Y.; Weng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, J.; Hu, B. N-acetylcysteine attenuates PM2. 5-induced apoptosis by ROS-mediated Nrf2 pathway in human embryonic stem cells. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 666, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.-K.; Kim, J.; Park, H.-M.; Lim, C.-M.; Pham, T.-H.; Shin, H.Y.; Kim, S.-E.; Oh, D.-K.; Yoon, D.-Y. The DPA-derivative 11S, 17S-dihydroxy 7, 9, 13, 15, 19 (Z, E, Z, E, Z)-docosapentaenoic acid inhibits IL-6 production by inhibiting ROS production and ERK/NF-κB pathway in keratinocytes HaCaT stimulated with a fine dust PM10. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 232, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain, N.U.; Qamar, S.U.R. Particulate matter-induced cardiovascular dysfunction: a mechanistic insight. Cardiovascular Toxicology 2021, 21, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, T.; Shephard, P.; Kleinert, H.; Kömhoff, M. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression by cyclic AMP. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2007, 1773, 1605–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.-L.; Huang, P.-H.; Wang, H.-C.; Tseng, C.-H.; Yen, F.-L. Pterostilbene attenuates particulate matter-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and aging in keratinocytes. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | GenBank Accession Number |

Primer Sequences | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1)/Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 (PTGS1) |

NM_000962.4 | Forward: 5'-CAGAGCCAGATGGCTGTGGG-3' Reverse: 5'-AAGCTGCTCATCGCCCCAGG-3' |

[32] |

| Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2)/Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) |

NM_000963.3 | Forward: 5'-CTGCGCCTTTTCAAGGATGG-3' Reverse: 5'-CCCCACAGCAAACCGTAGAT-3' |

[33] |

| Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPGES-1)/Prostaglandin E synthase (PTGES) |

NM_004878.5 | Forward: 5'-AACCCTTTTGTCGCCTG-3' Reverse: 5'-GTAGGCCACGGTGTGT-3' |

[34] |

| Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 2 (mPGES-2); Prostaglandin E synthase 2 (PTGES2) |

NM_025072.7 | Forward: 5'-GAAAGCTCGCAACAACTAAAT-3' Reverse: 5'-CTTCATGGCTGGGTAGTAG-3' |

[34] |

| Cytosolic prostaglandin E synthase (cPGES)/ Prostaglandin E synthase 3 (PTGES3) |

NM_006601.6 | Forward: 5’-ATAAAAGAACGGACAGATCAA-3’ Reverse: 5’-CACTAAGCCAATTAAGCTTTG-3’ |

[34] |

| L-PGDS (PTGDS) | NM000954 | Forward: 5'-AACCAGTGTGAGACCCGAAC-3' Reverse: 5'-AGGCGGTGAATTTCTCCTTT-3' |

[35] |

| H-PGDS (HPGDS) | NM014485 | Forward: 5'-CCCCATTTTGGAAGTTGATG-3' Reverse: 5'-TGAGGCGCATTATACGTGAG-3 |

[35] |

|

GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) |

NM_002046.3 | Forward: 5'-ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG-3' Reverse: 5'-GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAA-3' |

[36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).