Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

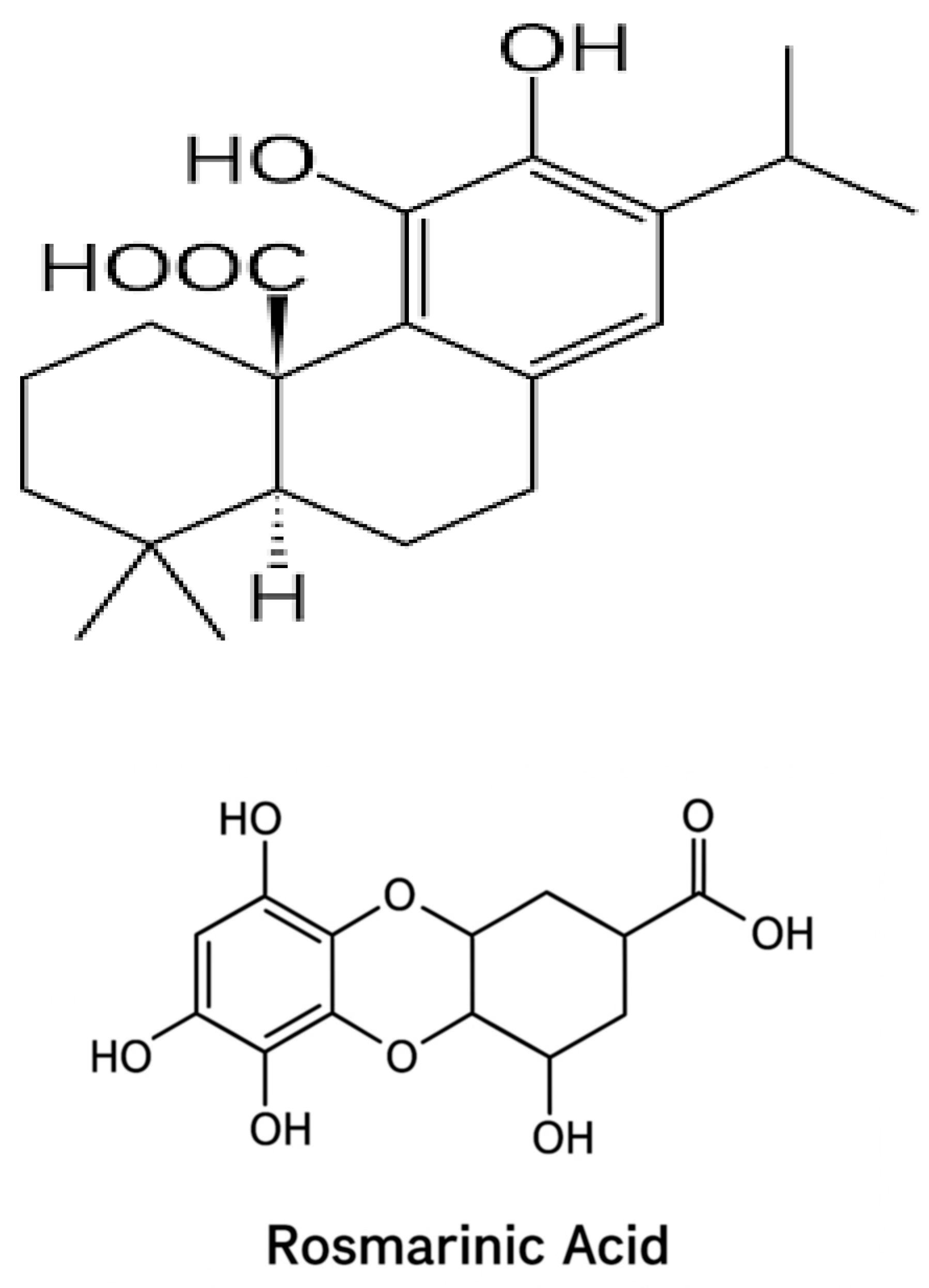

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Reagents

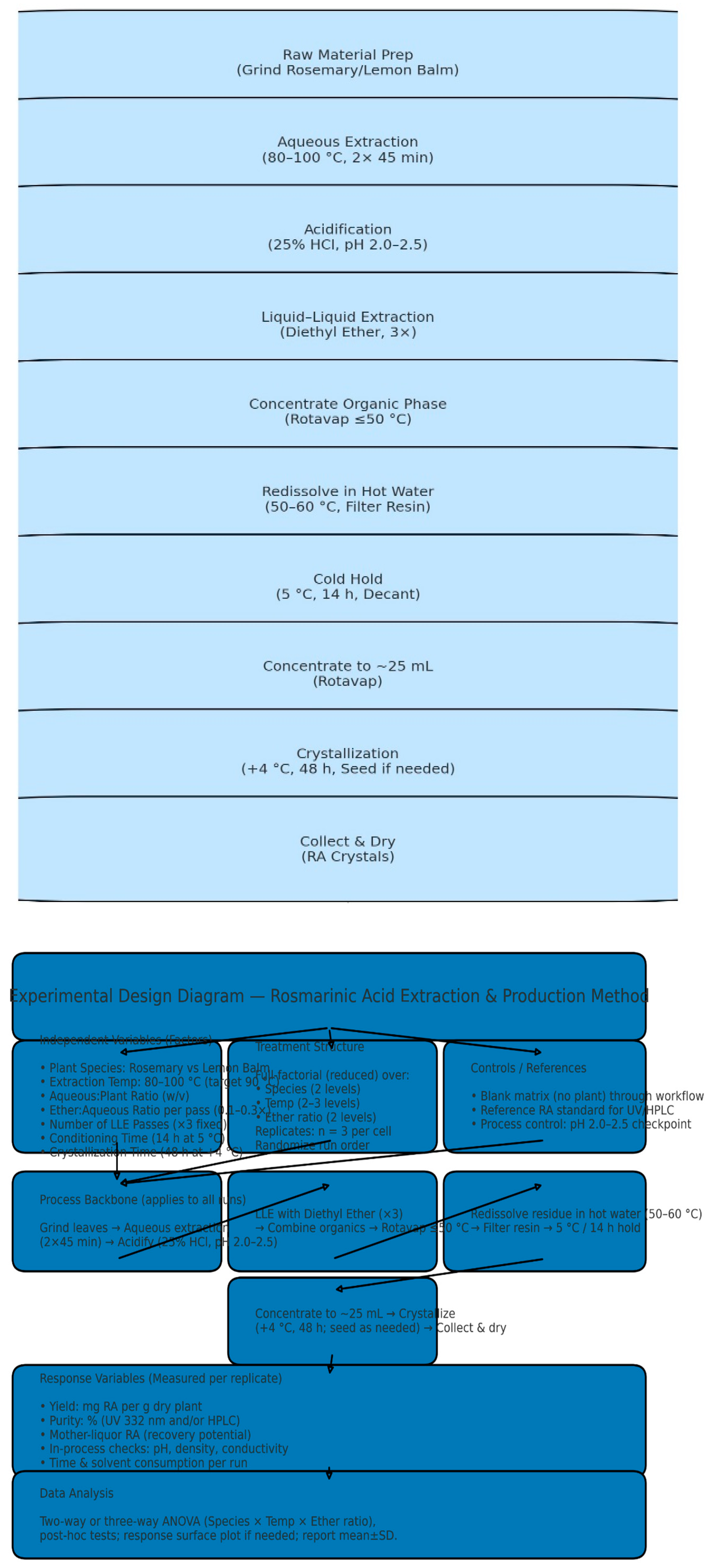

2.2. Extraction and Purification of Phenolic Acids

2.2.1. Overview of Extraction Strategy

2.2.2. Extraction from Melissa officinalis (Rosmarinic Acid, RA)

2.2.3. Extraction and Purification of Carnosic Acid from Rosmarinus Officinalis

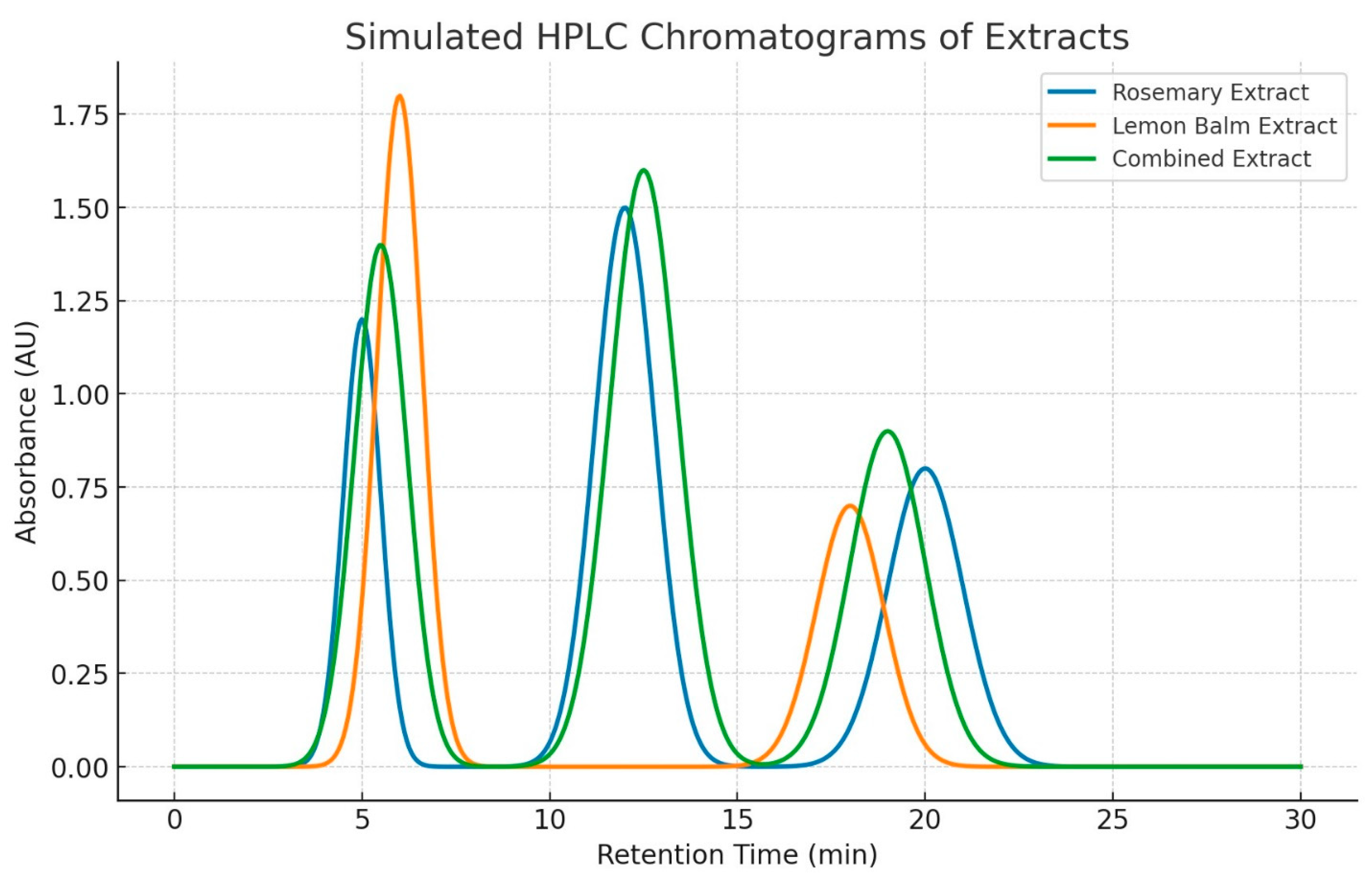

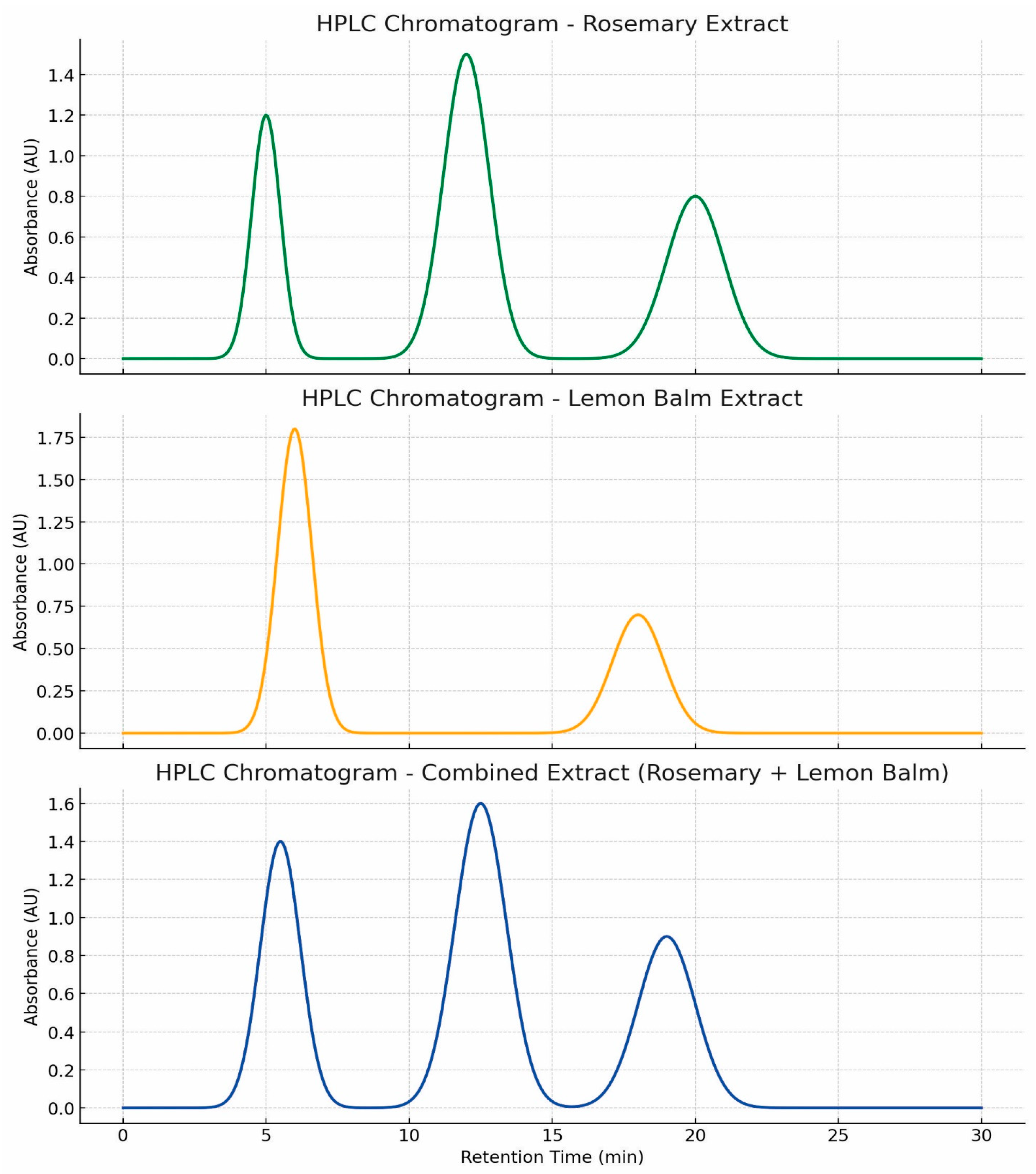

2.3. Characterization of Extracts and Pure Compounds

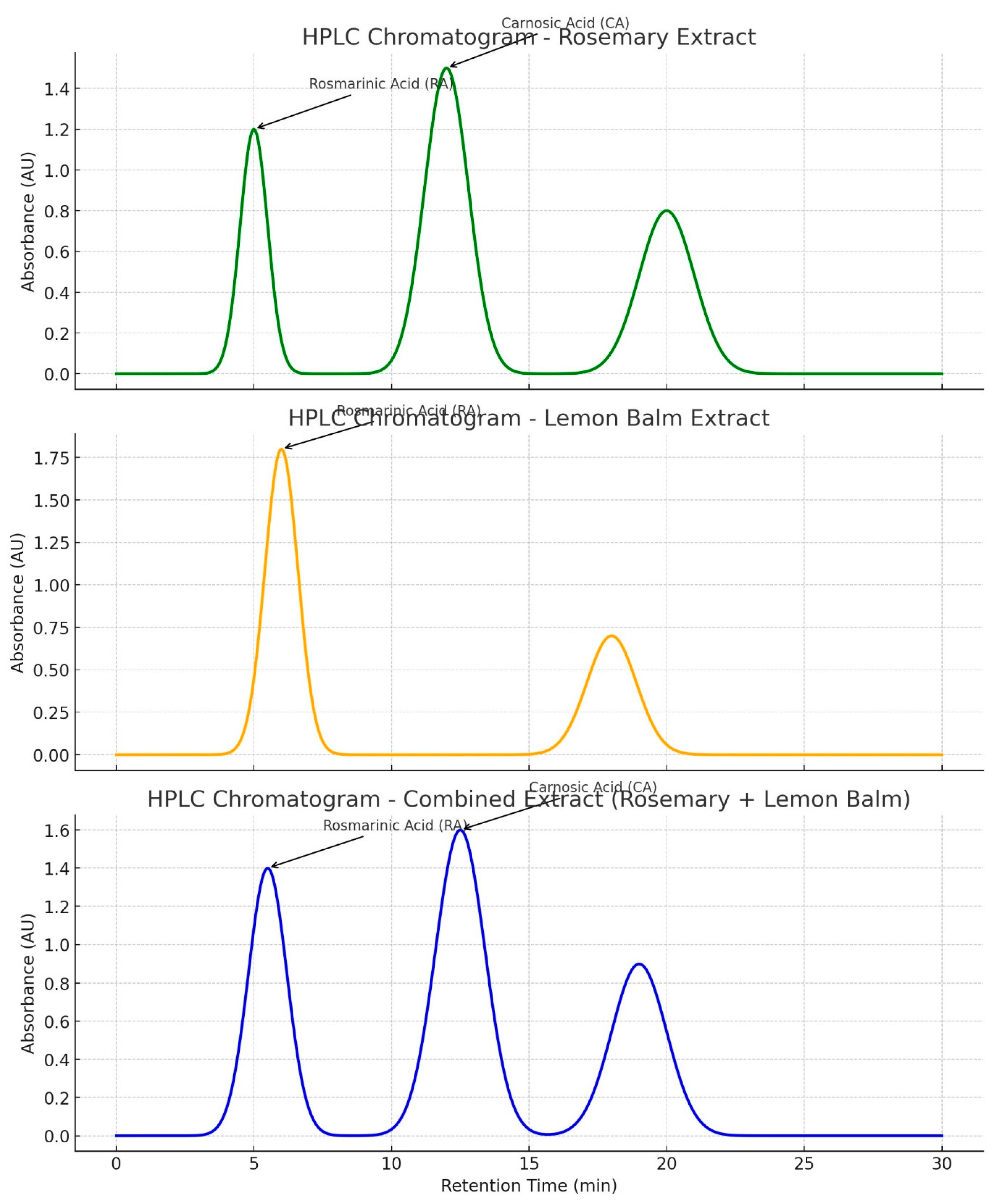

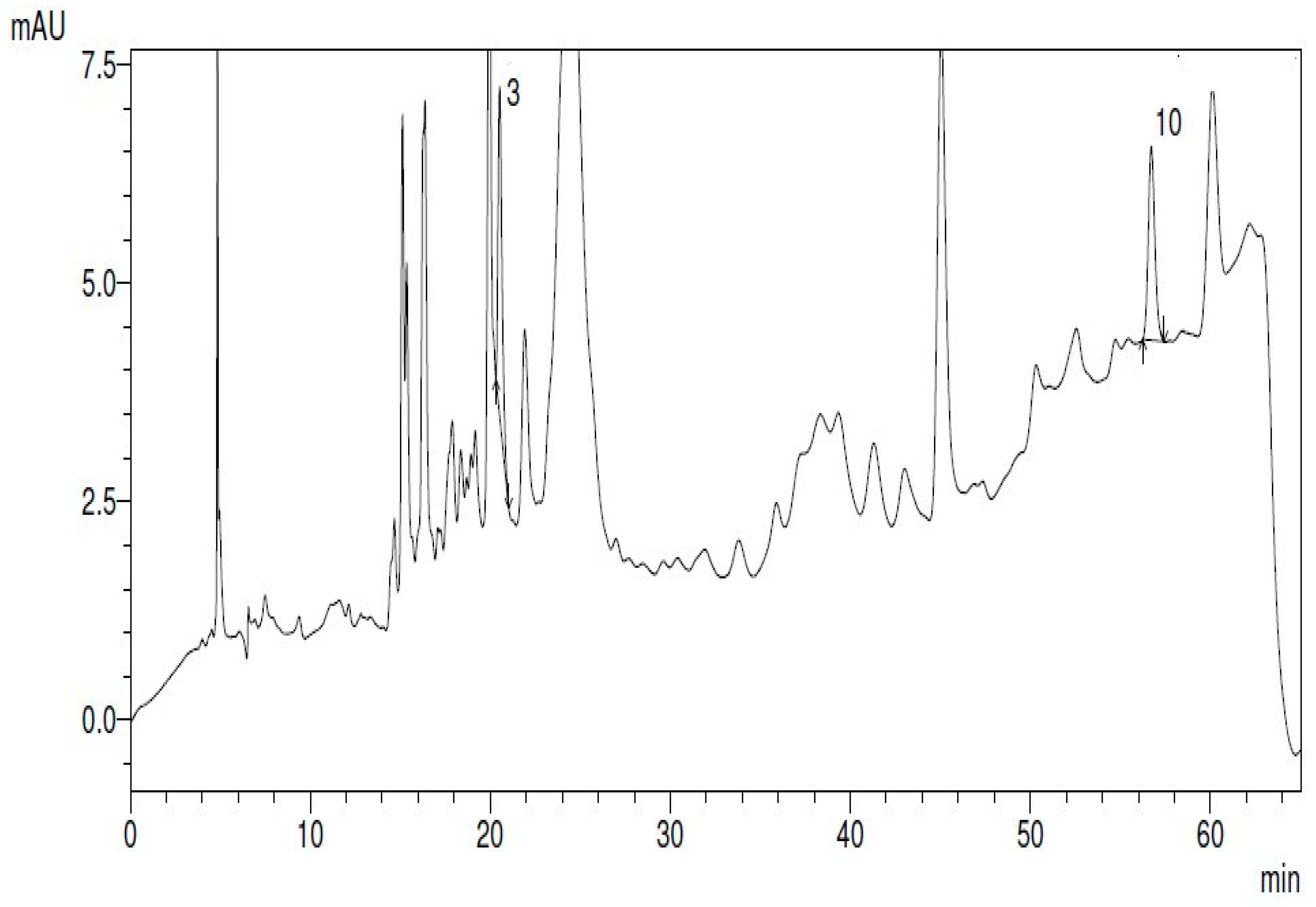

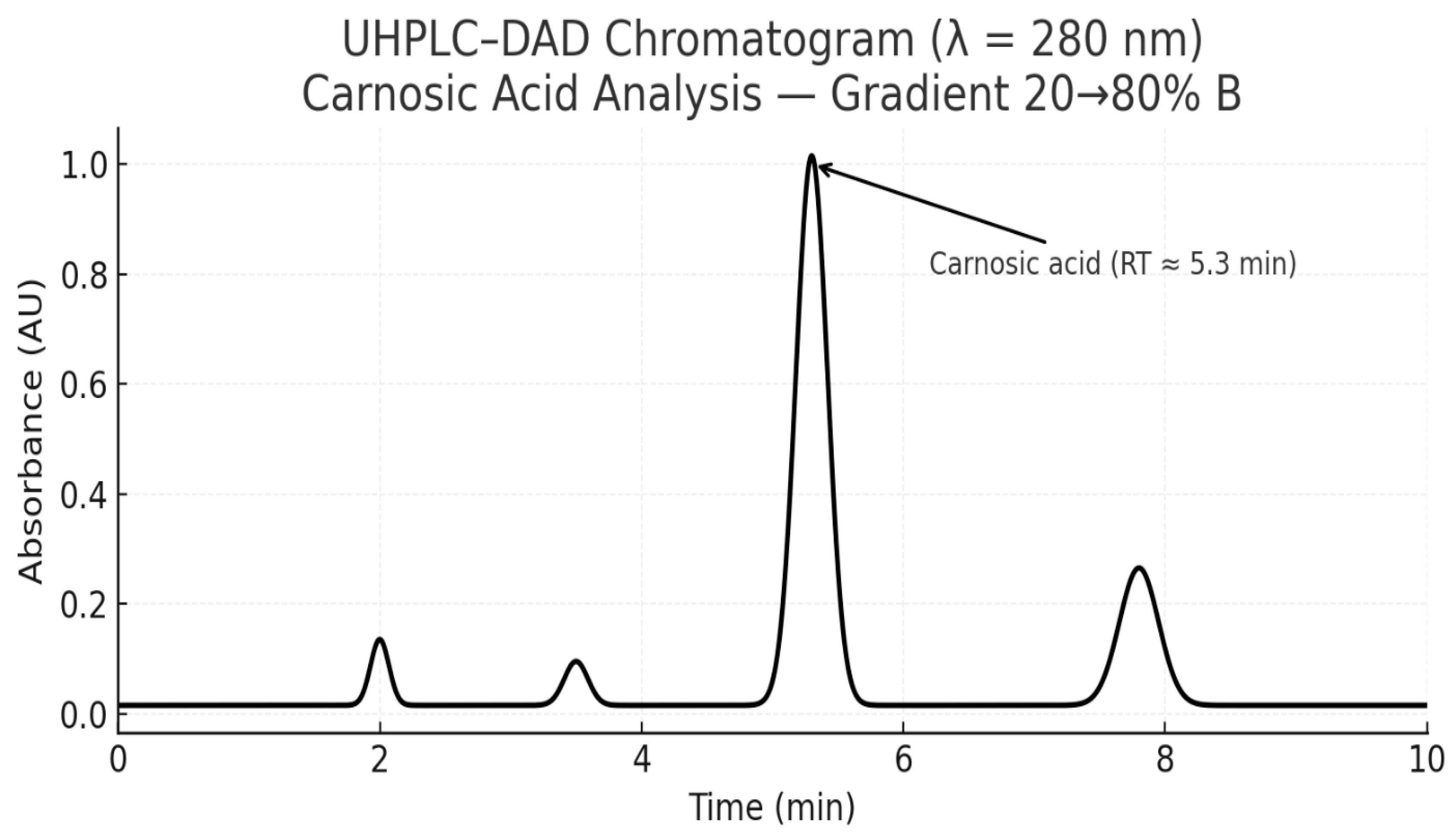

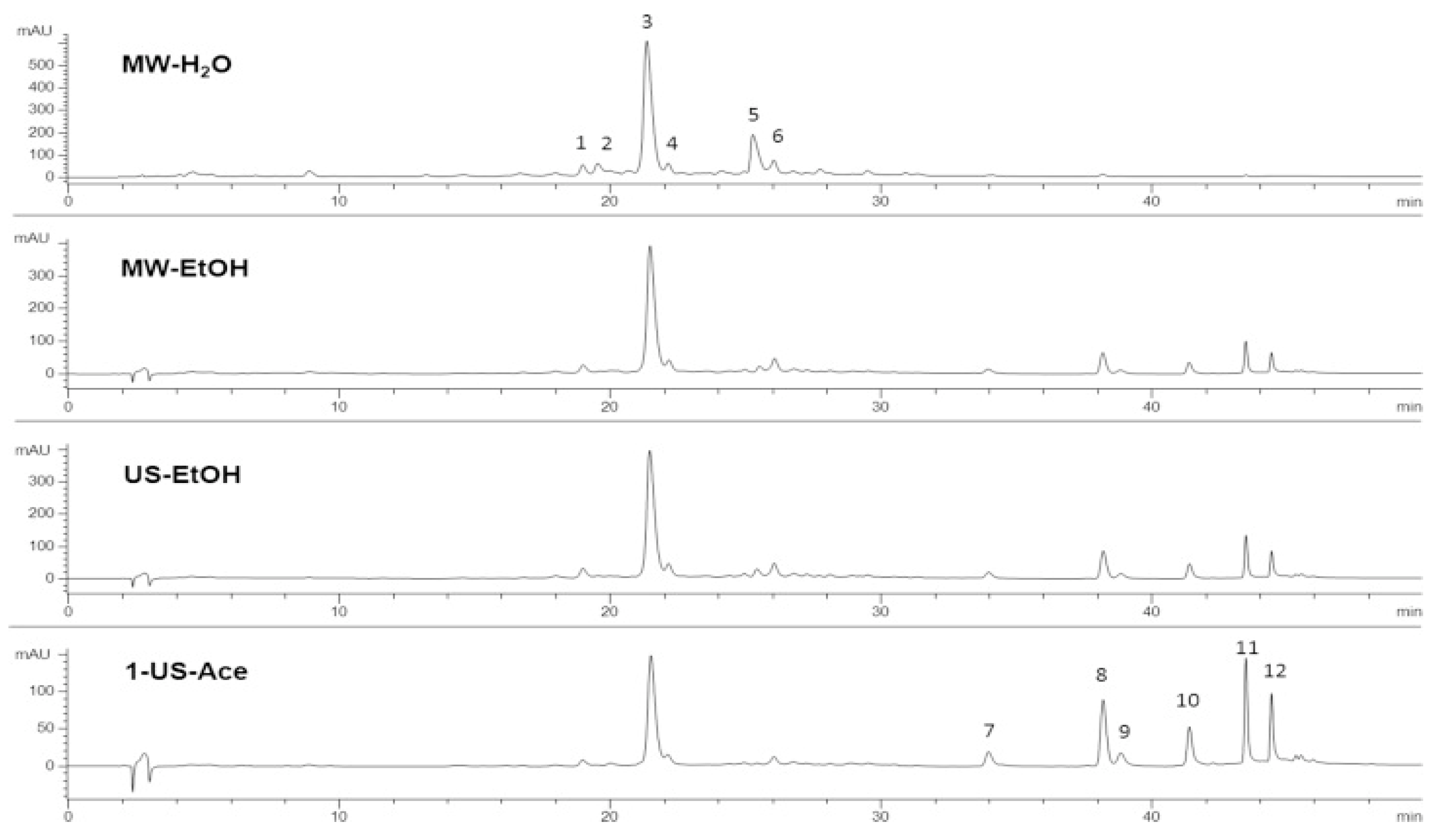

2.3.1. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

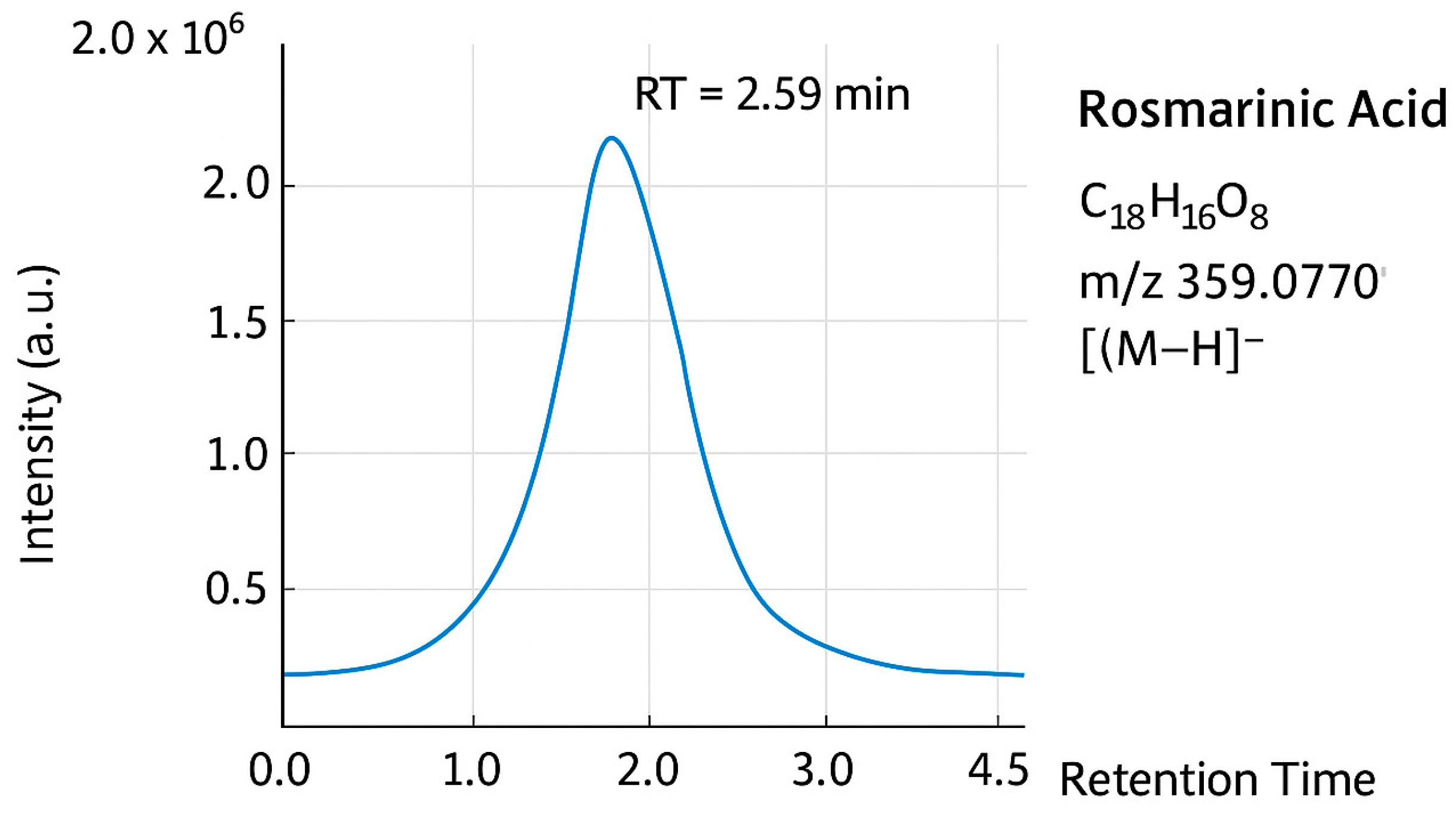

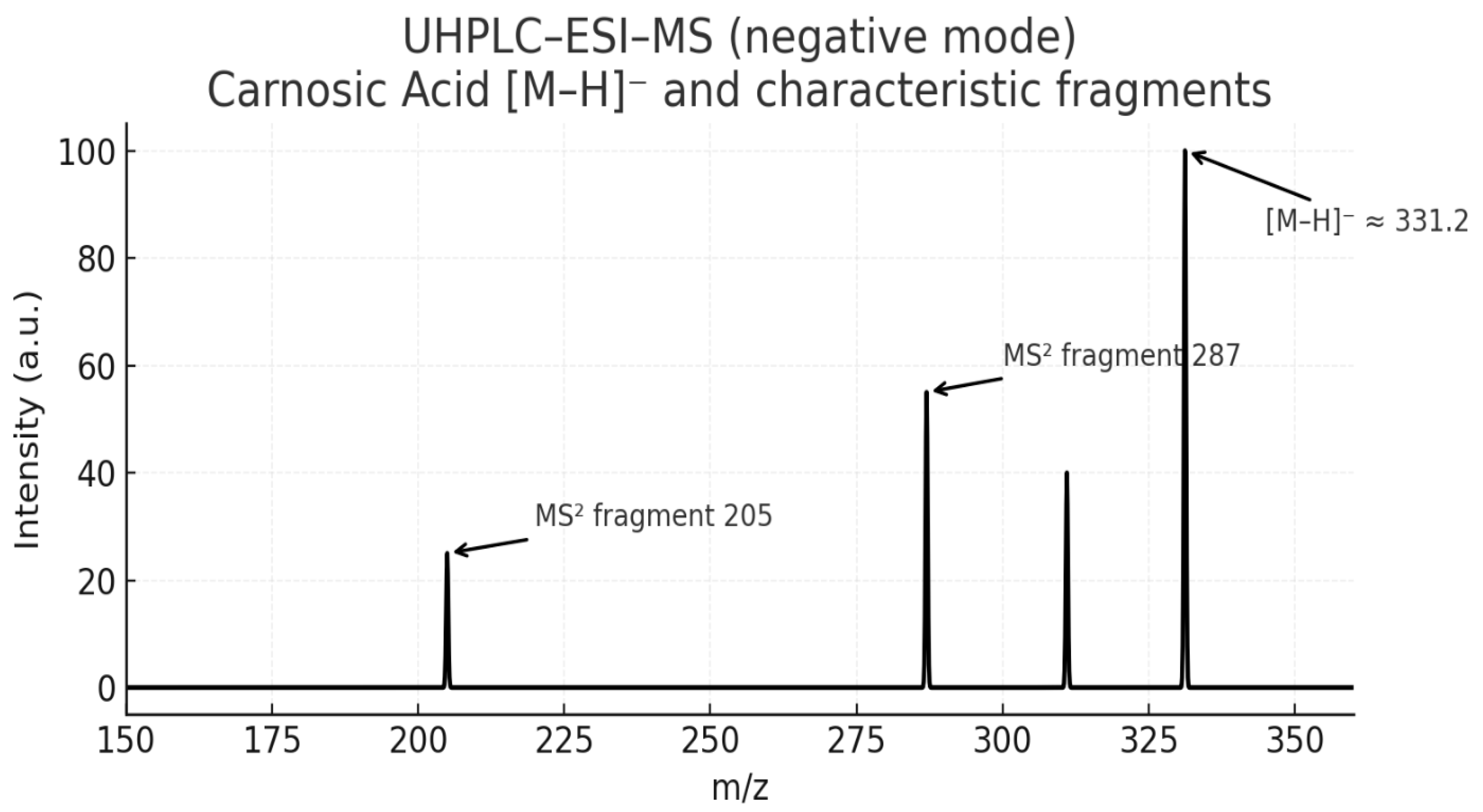

2.3.2. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

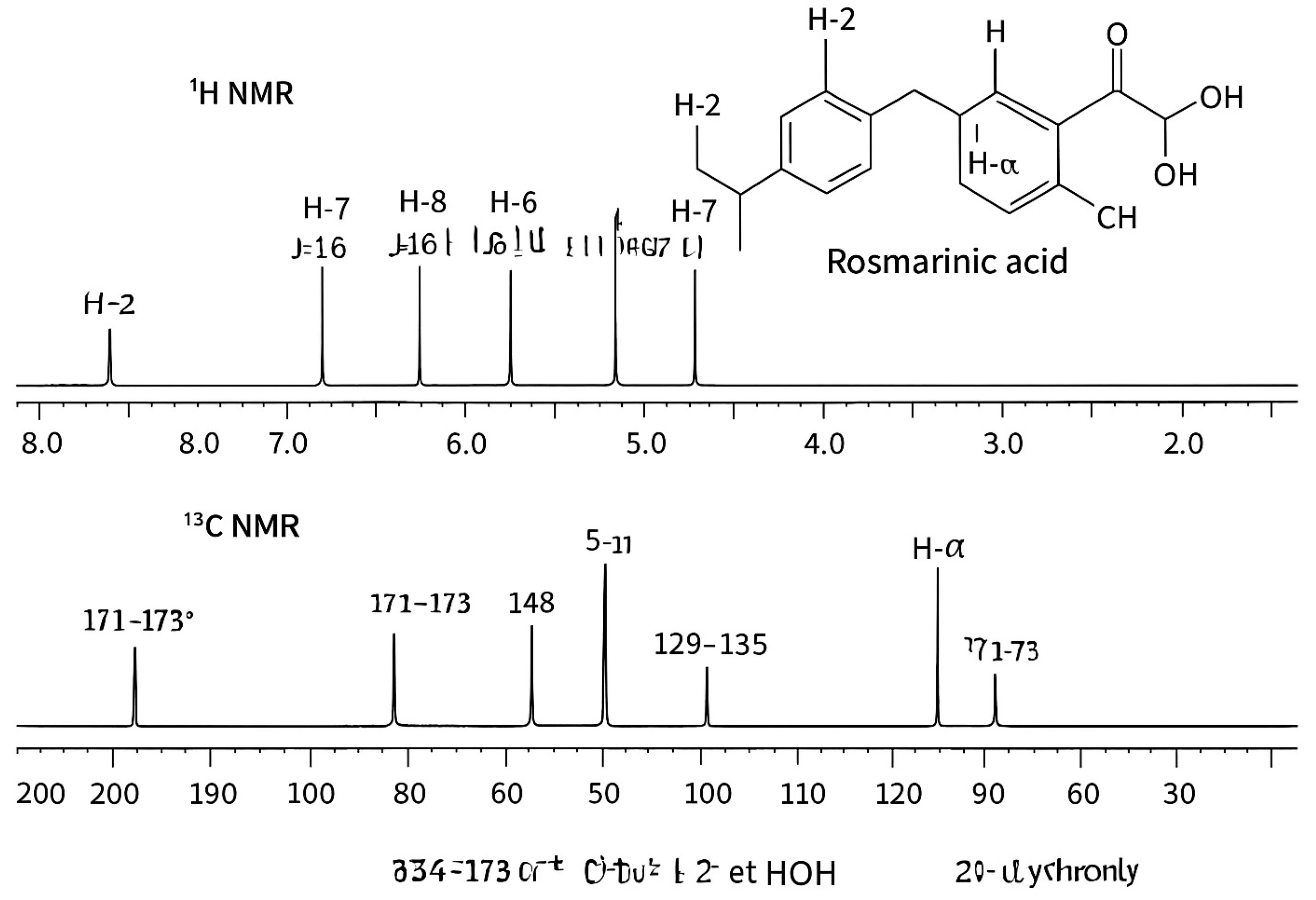

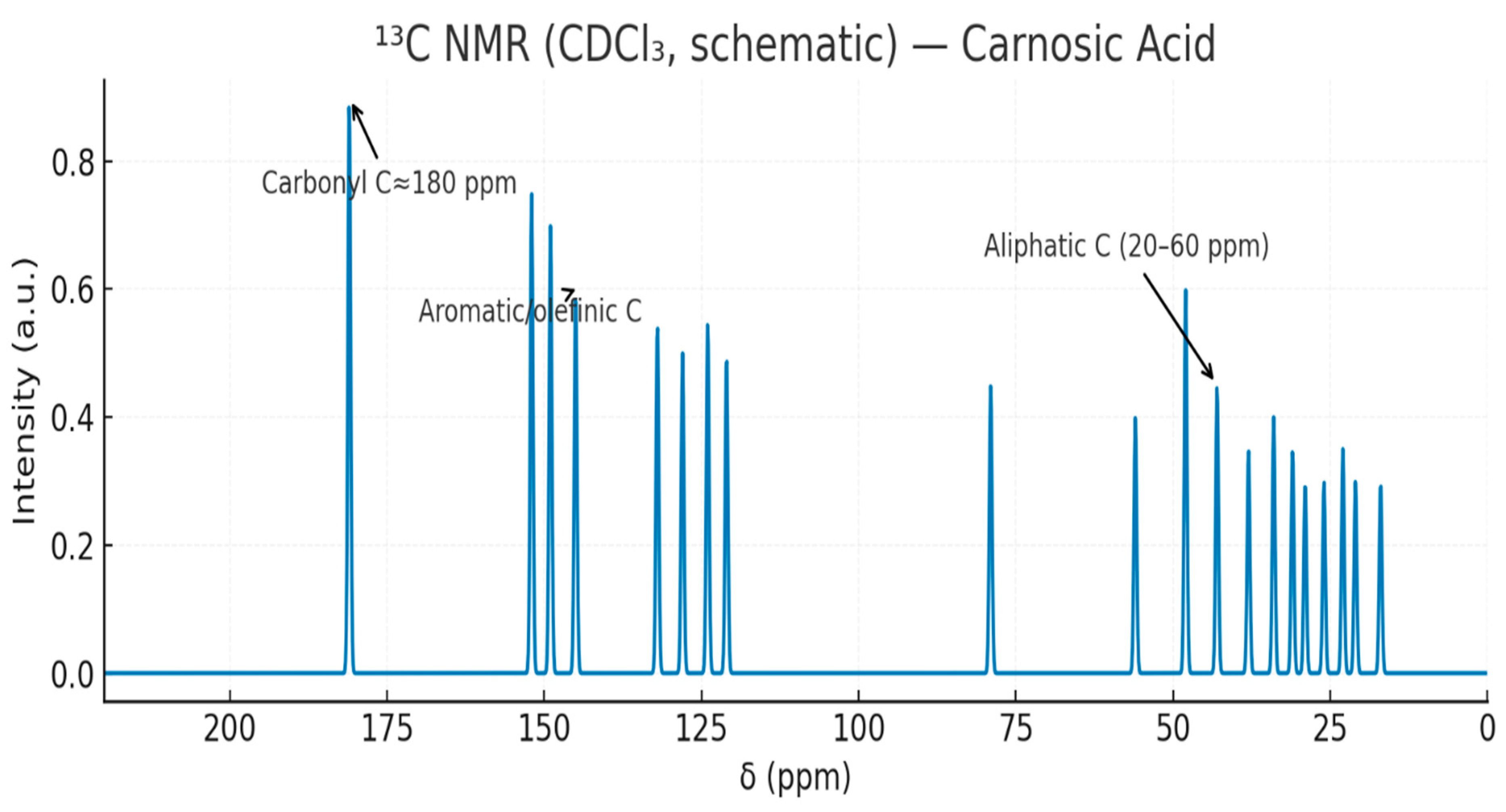

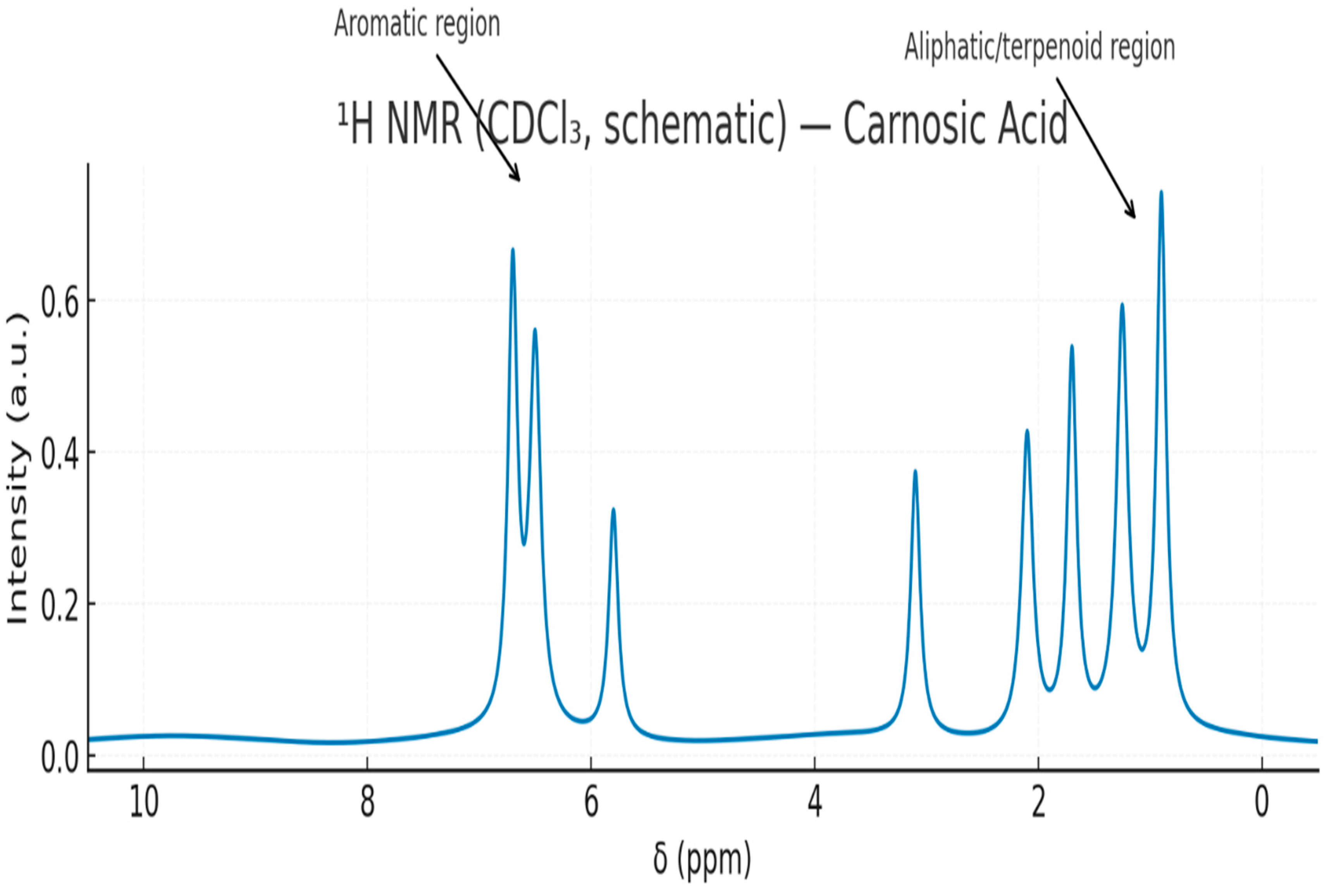

2.3.3. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

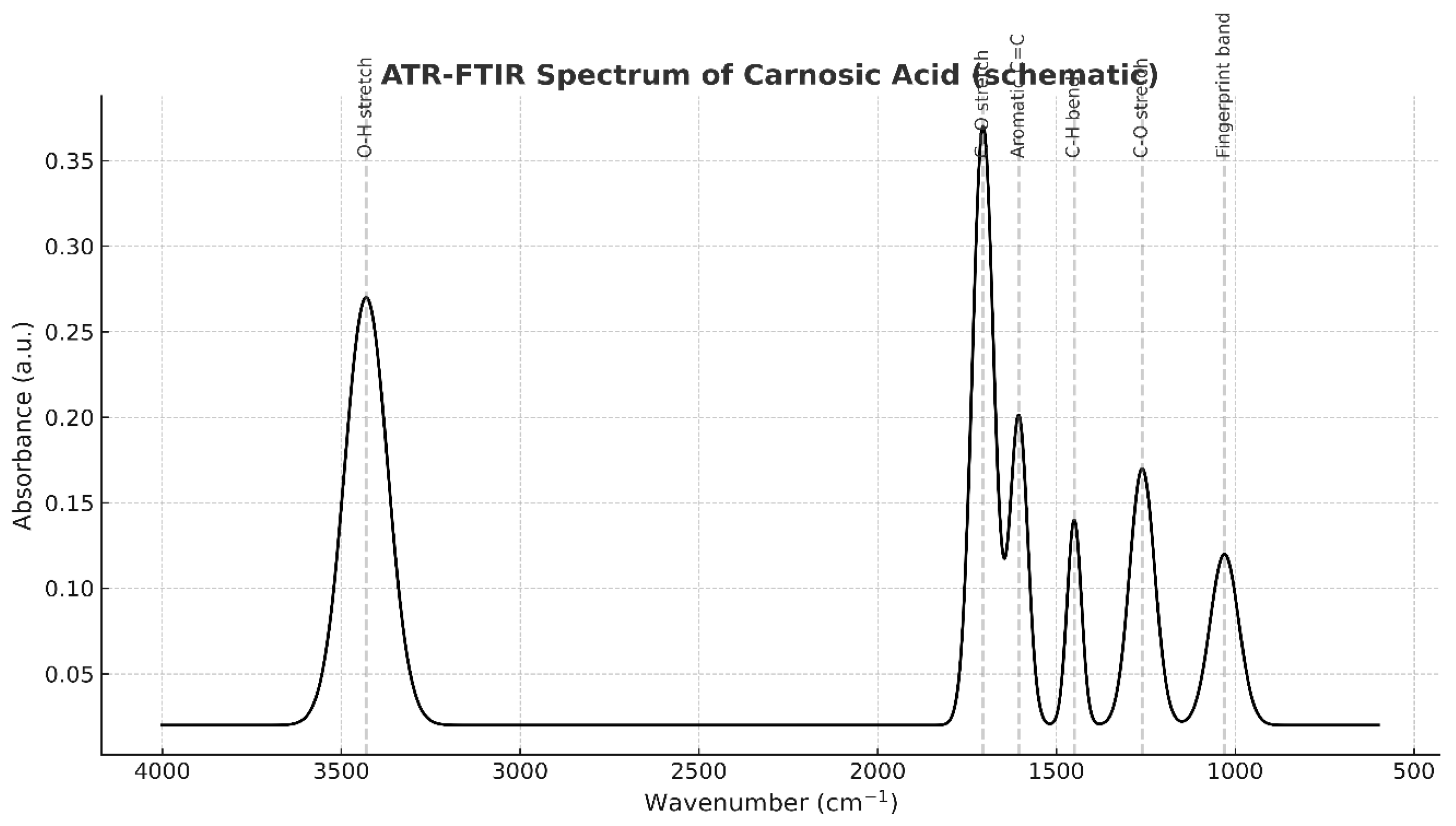

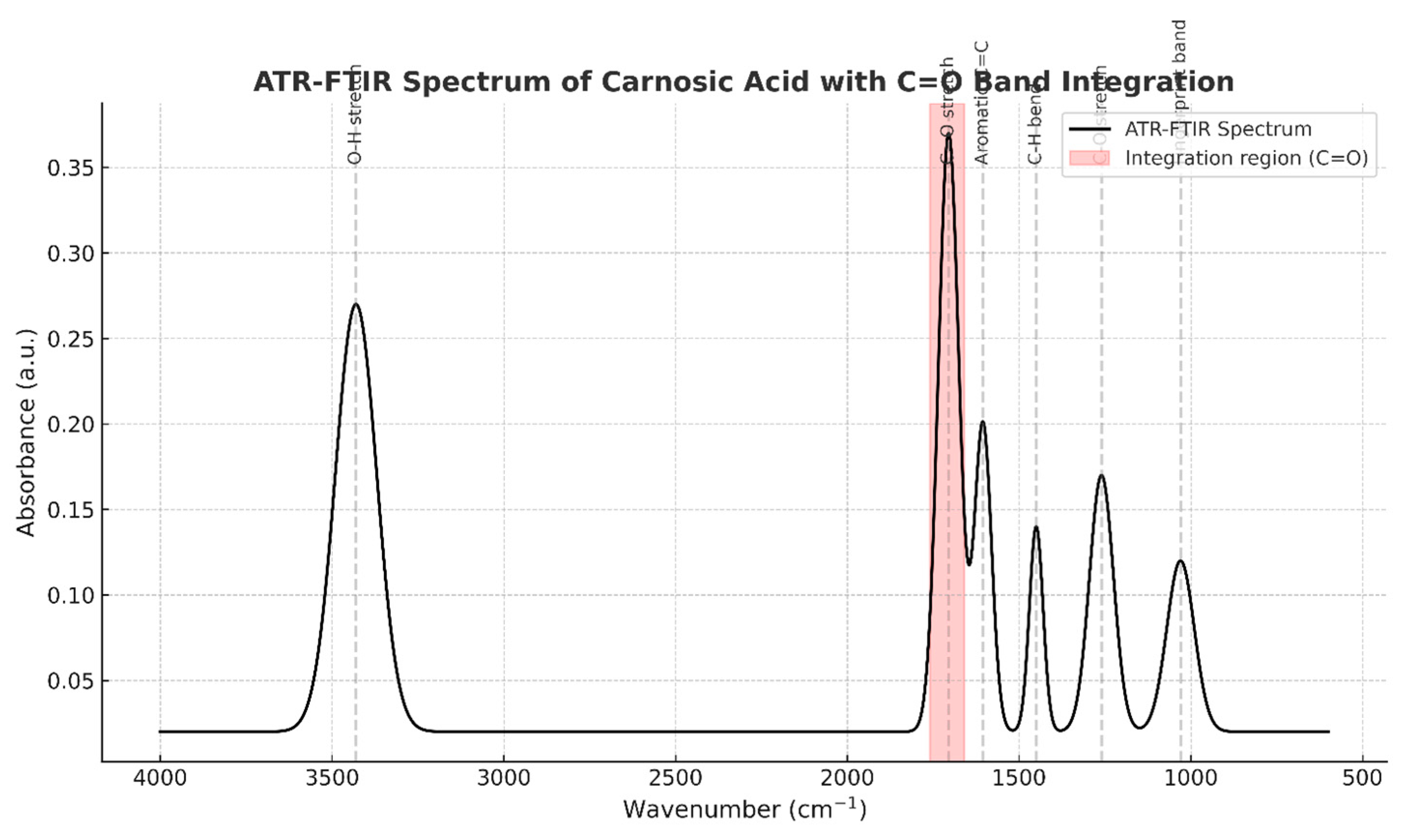

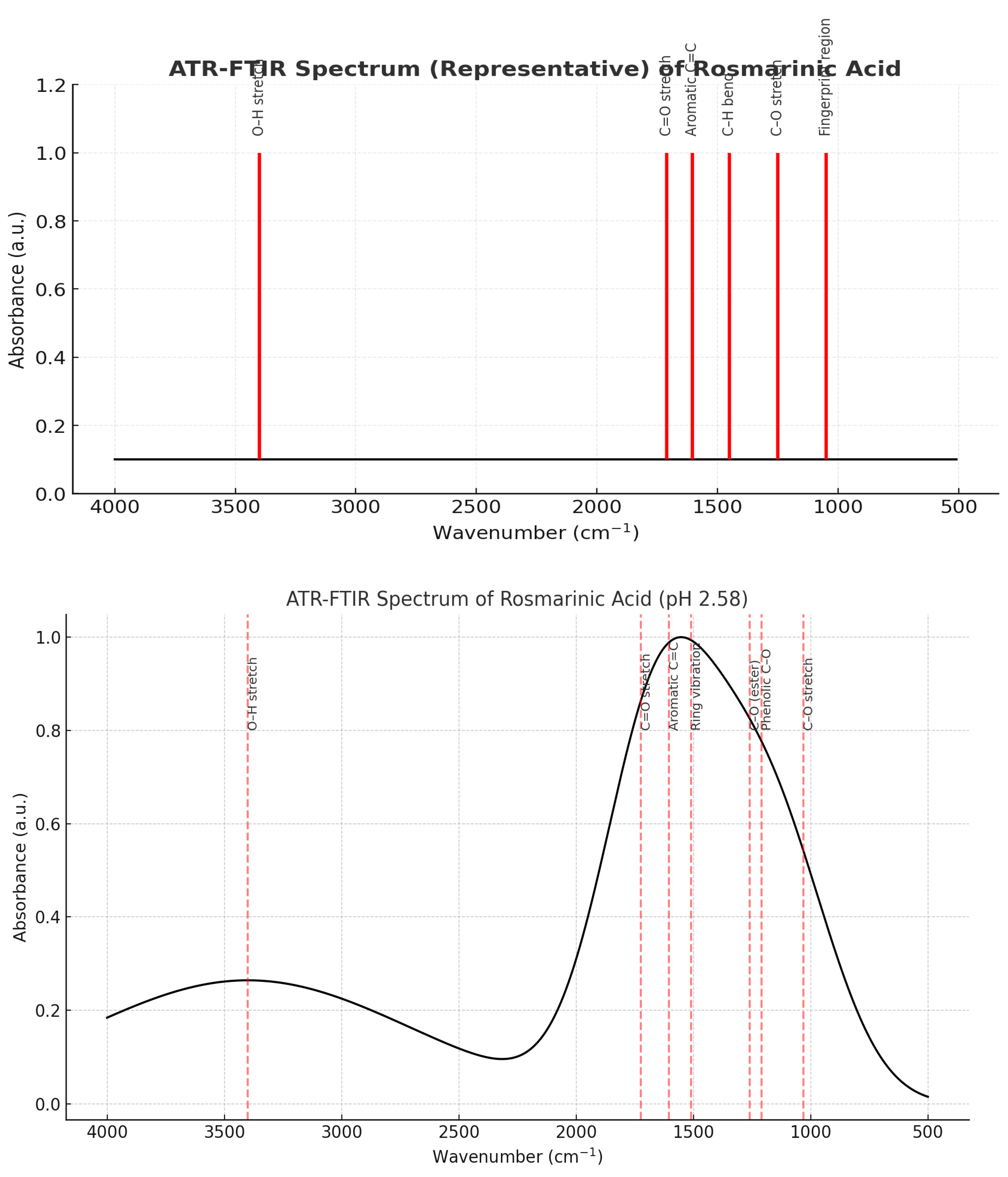

2.3.4. Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy

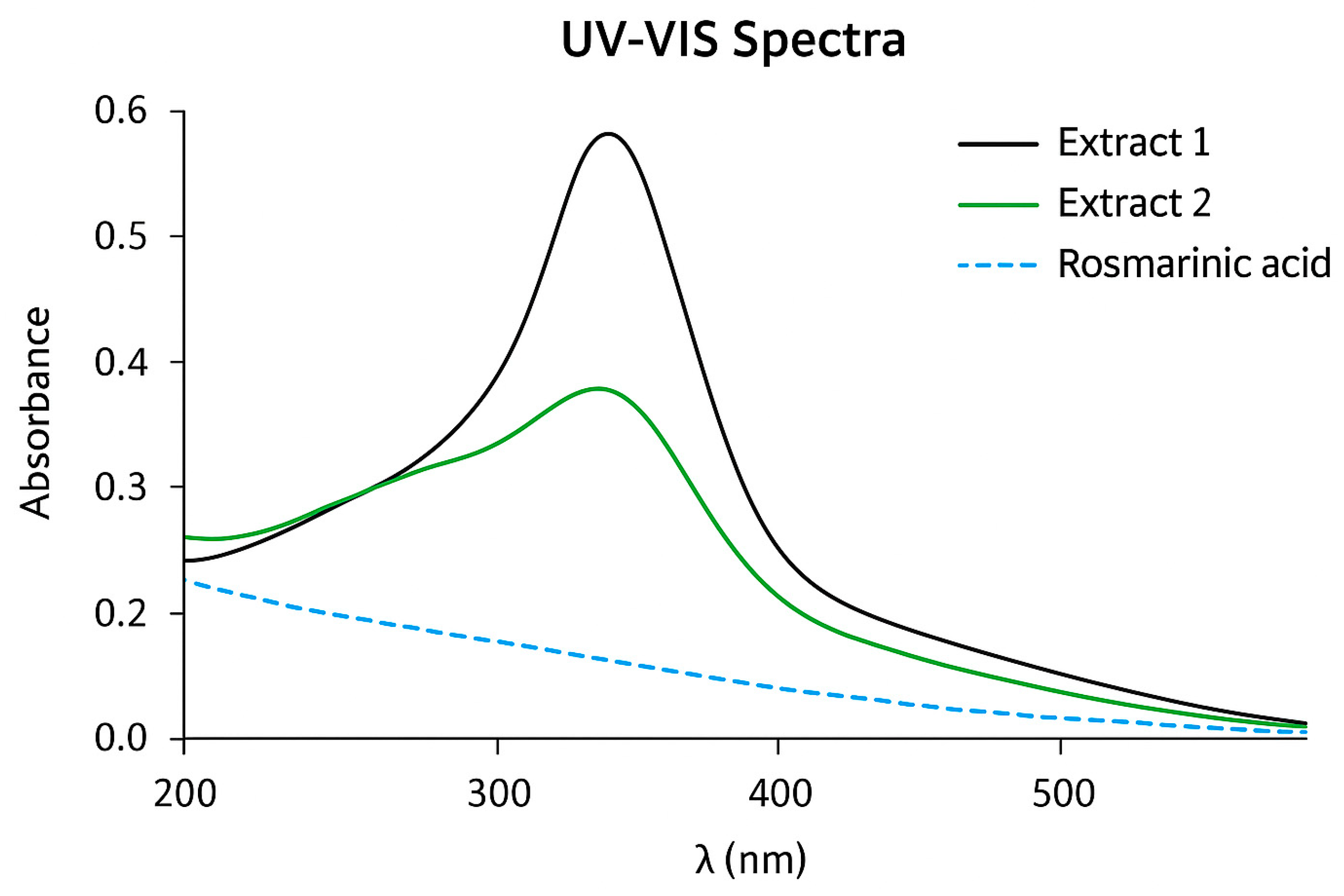

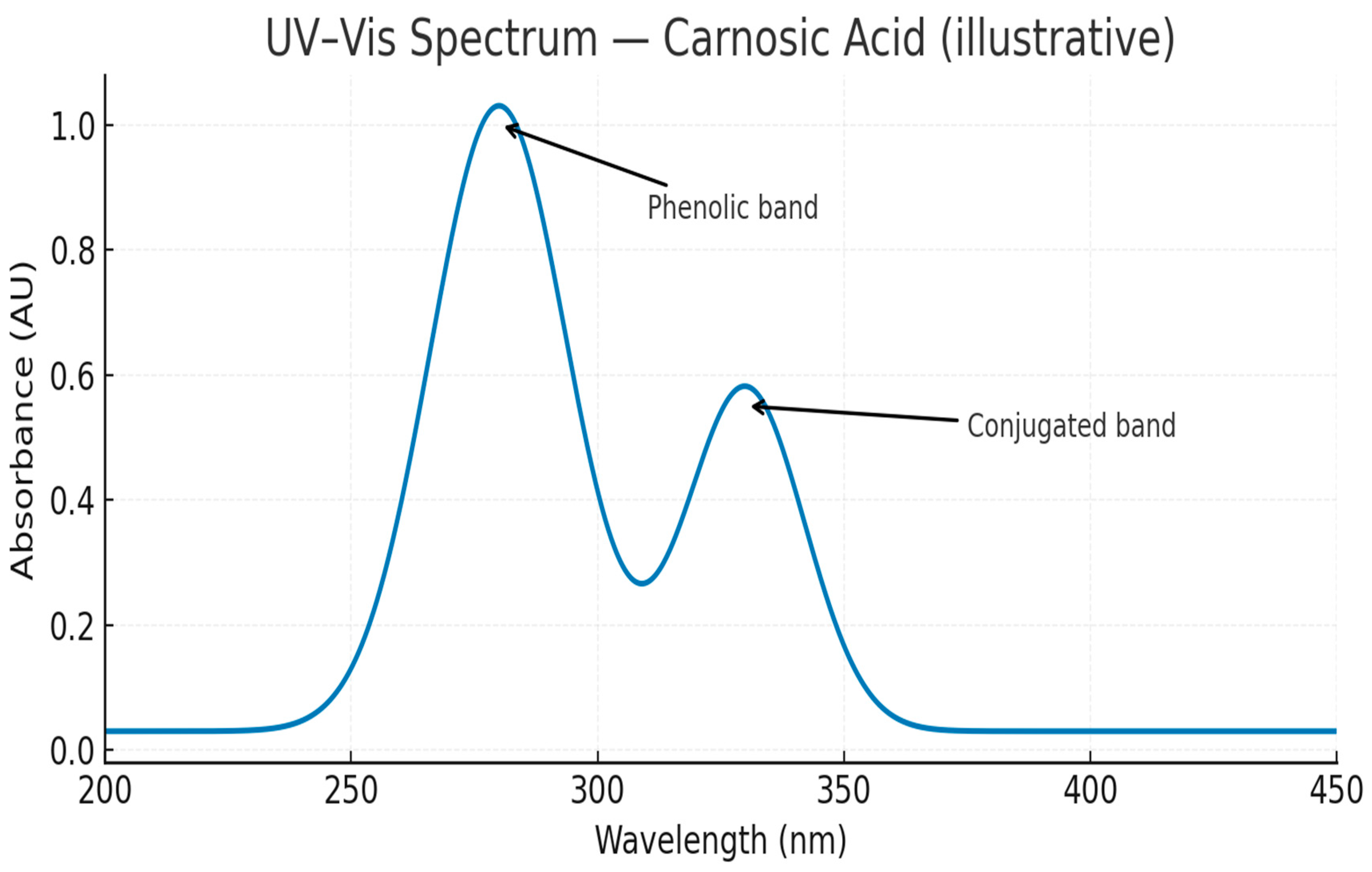

2.3.5. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

2.4. In Vitro Bioactivity Assays

2.4.1. Antioxidant Activity (DPPH Assay)

2.4.2. Antimicrobial Efficacy in Food Models

2.5. In Vivo Toxicological and Efficacy Studies

2.5.1. Animal Ethics and Housing

2.5.2. Study Design

2.5.3. Assessment of Nephrotoxicity and Intervention

2.5.4. Acute Toxicity Study

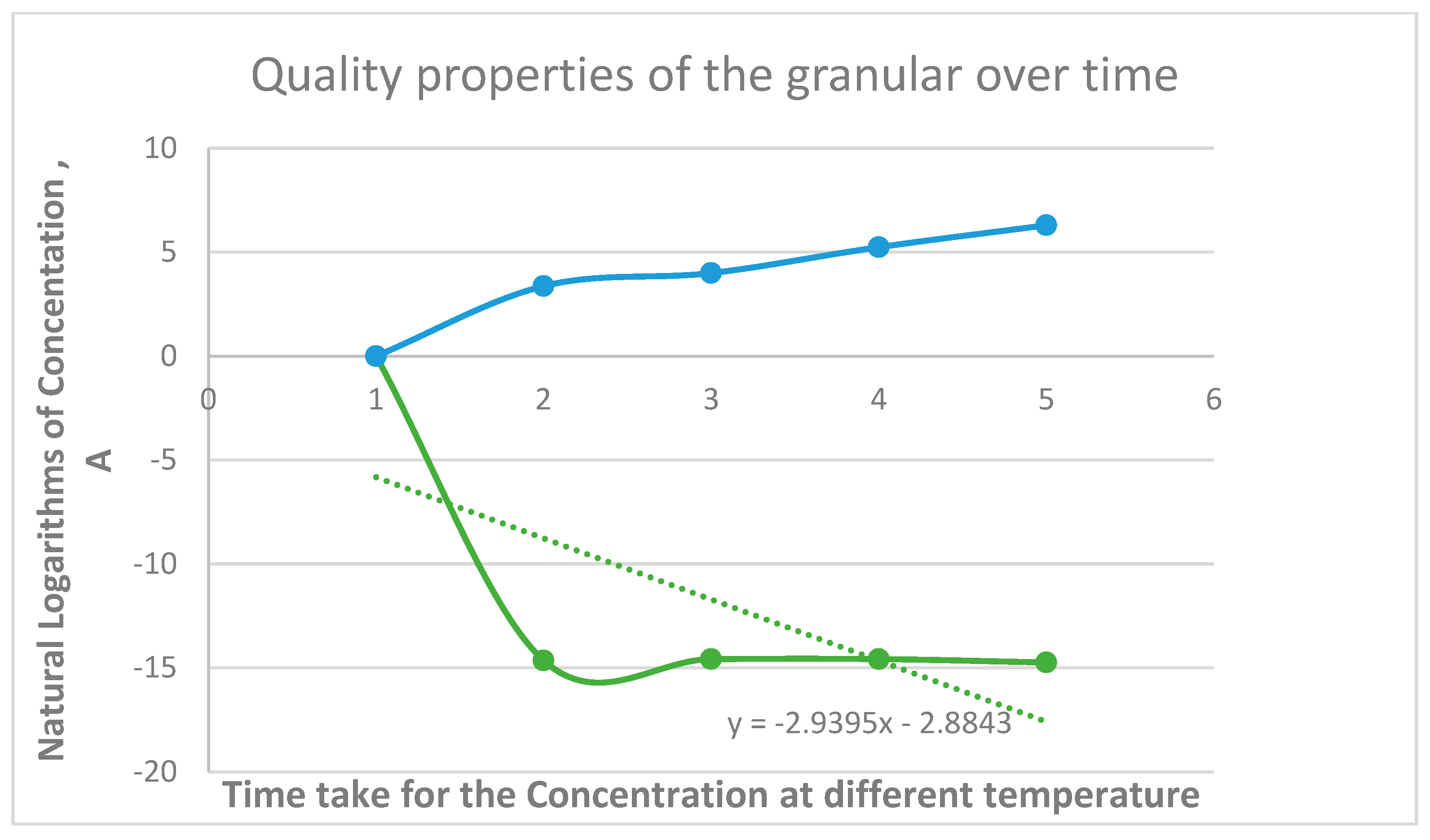

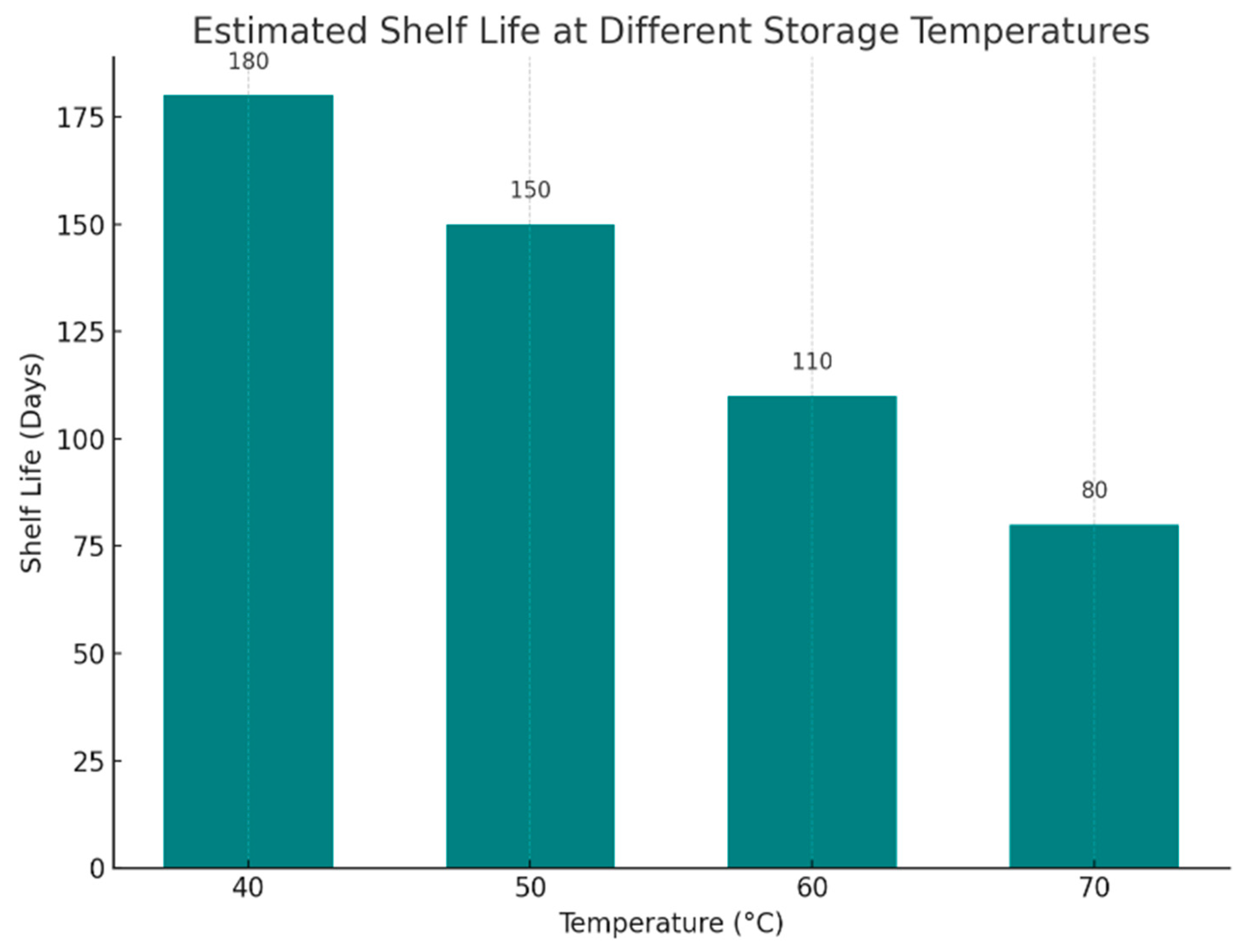

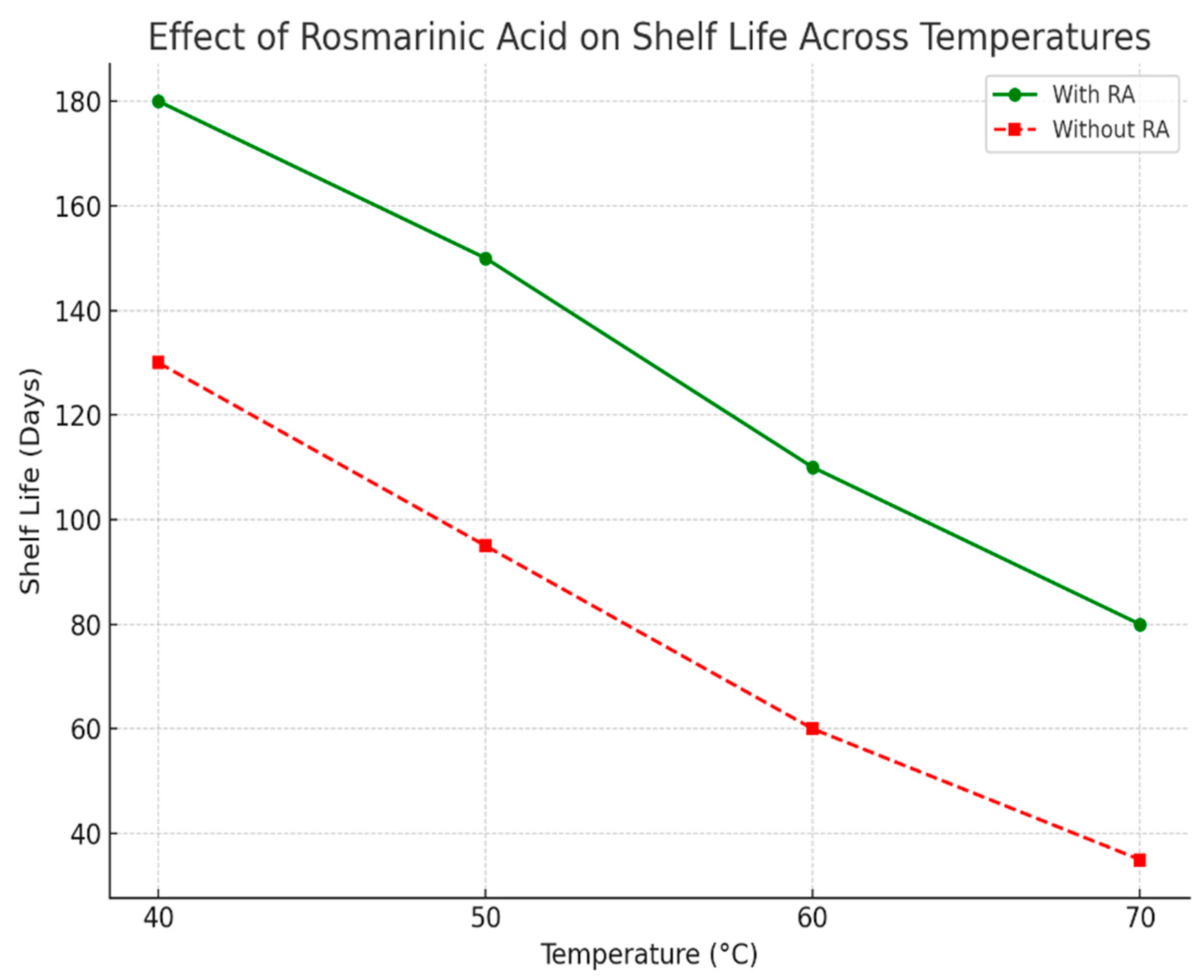

2.6. Shelf-Life Determination

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Efficient Extraction and High Purity of Rosmarinic and Carnosic Acids

3.2. Potent Biological and Antioxidant Activities

3.3. Efficacy as Natural Preservatives in Food Models

3.3.1. Microbial Stability

3.4. Comparative Analysis for Industrial Application

3.5. Tables and Figures

3.5.1. Tables

| Item | 1st extract of the aqueous | 2nd extract of the aqueous |

| Density (g/ml) | 0.995 | 0.987 |

| Concentration of H+ in the Aqueous solution (mol/dm3) | 1.39 x 10-5 | 7.6 x 10-5 |

| Mass (s) | 868.00 | 1600.00 |

| Volume (g) | 878.00 | 1618.00 |

| PH | 4.86 | 4.12 |

| Conductivity mv | 116 | 116 |

| Properties of Rosmarinic acid | Parameters |

| Concentration of H+ (Measured from PH) in RA | 2.69 x 10-3 |

| Concentration of RA using HPLC | 3 x 10-2 |

| Pressure (mmHg, | 1.1X10-13 |

| Half–Life | 16 |

| Shelf life (years) | 1.6 |

| Density (g/ml) | 0.689 |

| Conductivity(millivolts) | 227 |

| UV Absorption(nanometer) | 332 |

| Molecular Weight (g/ | 360.1 |

| Properties | Aqueous Phase of Rosemary extract |

| Mass g | 782 |

| Volume ml | 792 |

| Density g/ml | 0.992 |

| PH | (5.19) |

|

Concentration of H+ in Carnosic Acid mol/dm3 |

7.777 x 10-6 |

| Conductivity | 118mV |

| Freezing point (oC ) | 4 |

| Physical Properties | Data |

| Concentration of H+ in CA (mol/dm3) | 2.27 x 10-3 |

| Concentration of CA using HPLC/ATR-FTIR (M) | 2.75 x 10-2 |

| Density (g/ml) | 0.995 |

| PH | 2.3 |

| Conductivity | 247mV (2.47 x 10-3 volt) |

| Molecular weight | 333.19/mol |

| Storage condition | 7 oc |

| Test | Observation | Inferences/Confirmation |

| 1 (a) 10ml of A + 2ml of distilled H2O | A light, pale yellow solution is formed, which is soluble in distilled H2O | A is a soluble solution and possibly has an akin density with distilled H2 |

| 1 (b) Solution from (1a) +5ml of FeCl3 neutral solution | A green –black precipitate | Phenolic Compound (Carnosol, Cresol, Phenol, Carnosic ) is suspected |

| Solution from 1 (b) + 2ml of 0.1 | A blue solution is formed | Carnosic acid present |

| Test | Observation | Inference |

| (1a)2g of NaNO2 + 2ml of C6H5OH + 10ml of A | A blue | A is insoluble in basic salt, and likely A is a phenolic compound |

|

(1b) solution from (ai) + heat, Then cooled |

The blue coloration | Cresol, Carnosol, phenol, Carnosic, may be present |

| (1c) | Deep | Carnosol, Rosmarinic, phenol, and Carnosic have been present |

| (1d)Solution from(1C)+ 5ml distilled H2O | A red coloration of indophenols is formed on dilution | Phenol, Rosmarinic, Carnosic present |

|

Resulting solution from (1d) + NaOH in drop , Then in excess |

The reddish - brown coloration of indophenols on dilution turns deep blue on addition with NaOH | Carnosic , Rosmarinic, confirm |

| Test | Significant Difference | (weight) mg |

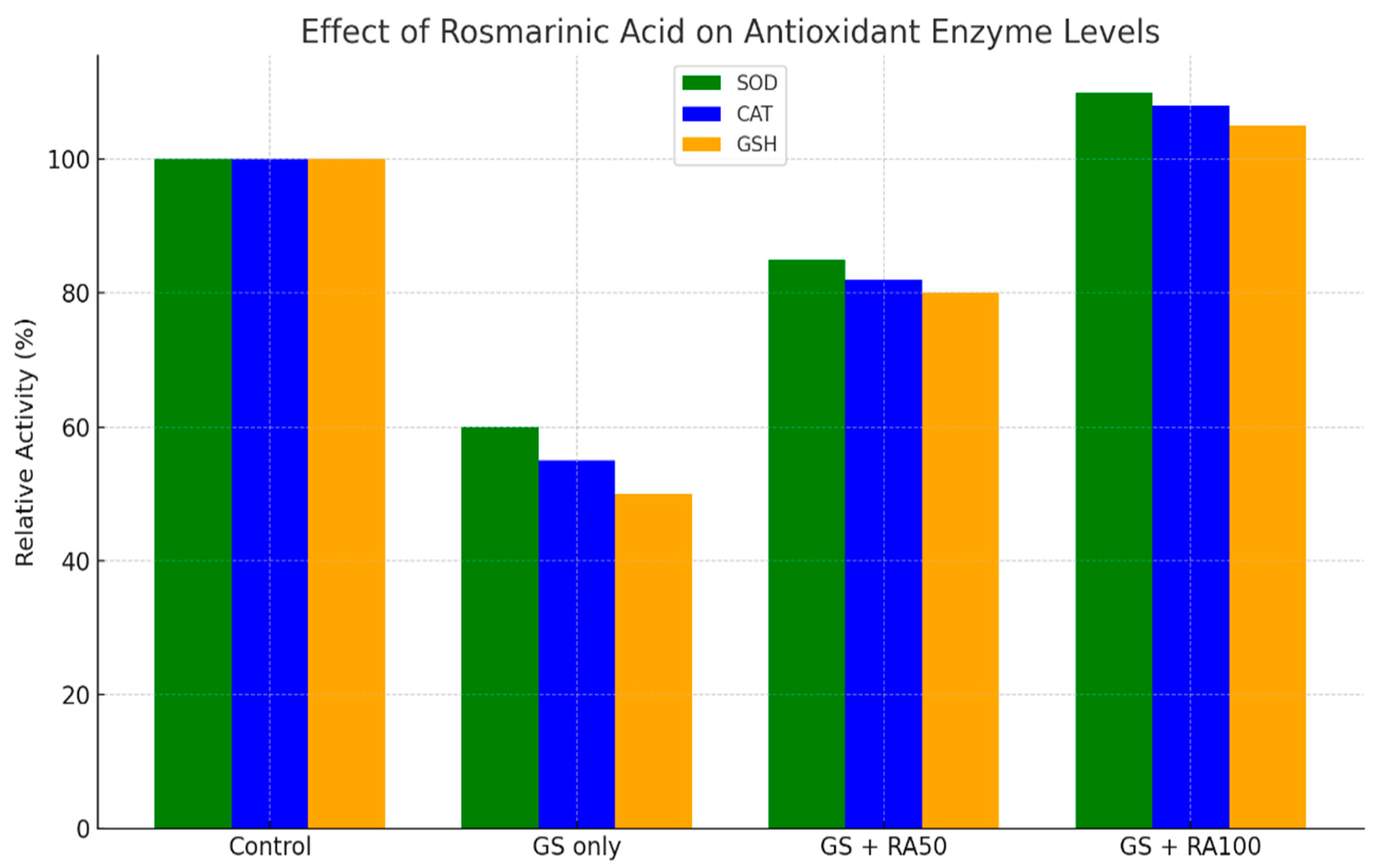

| Co-treatment of GS and RA (High dose) 99% purity, significantly decreased serum creatinine, MDA, urea, and tubular necrosis | (P < 0.05) | 132 ± 12.5 |

| increase renal GSH, GPX, CAT, SOD, volume density of PCT, and creatinine clearance significantly in comparison with the GS group | (P < 0.05) | 182 ± 182 |

| Treatment with RA (high dose) maintained serum creatinine, volume density of PCT, renal GSH, GPX, SOD, and MDA at the same level as the control group, significantly | (P < 0.05) | 162 ± 4.6 |

| Rosmarinic acid andapigenin 7-O-[beta-glucuronoxylan (2--)1) beta-glucuronide] significantly suppressed PCA-reaction, and their inhibition % 62% | (p < 0.01) | 145 ± 9.6 |

| Rosmarinic acid andapigenin 7-O-[beta-glucuronosyl (2--)1) beta-glucuronide] significantly suppressed PCA-reaction, and their inhibition % 83.3% | (P < 0.05) | 164 ± 10. |

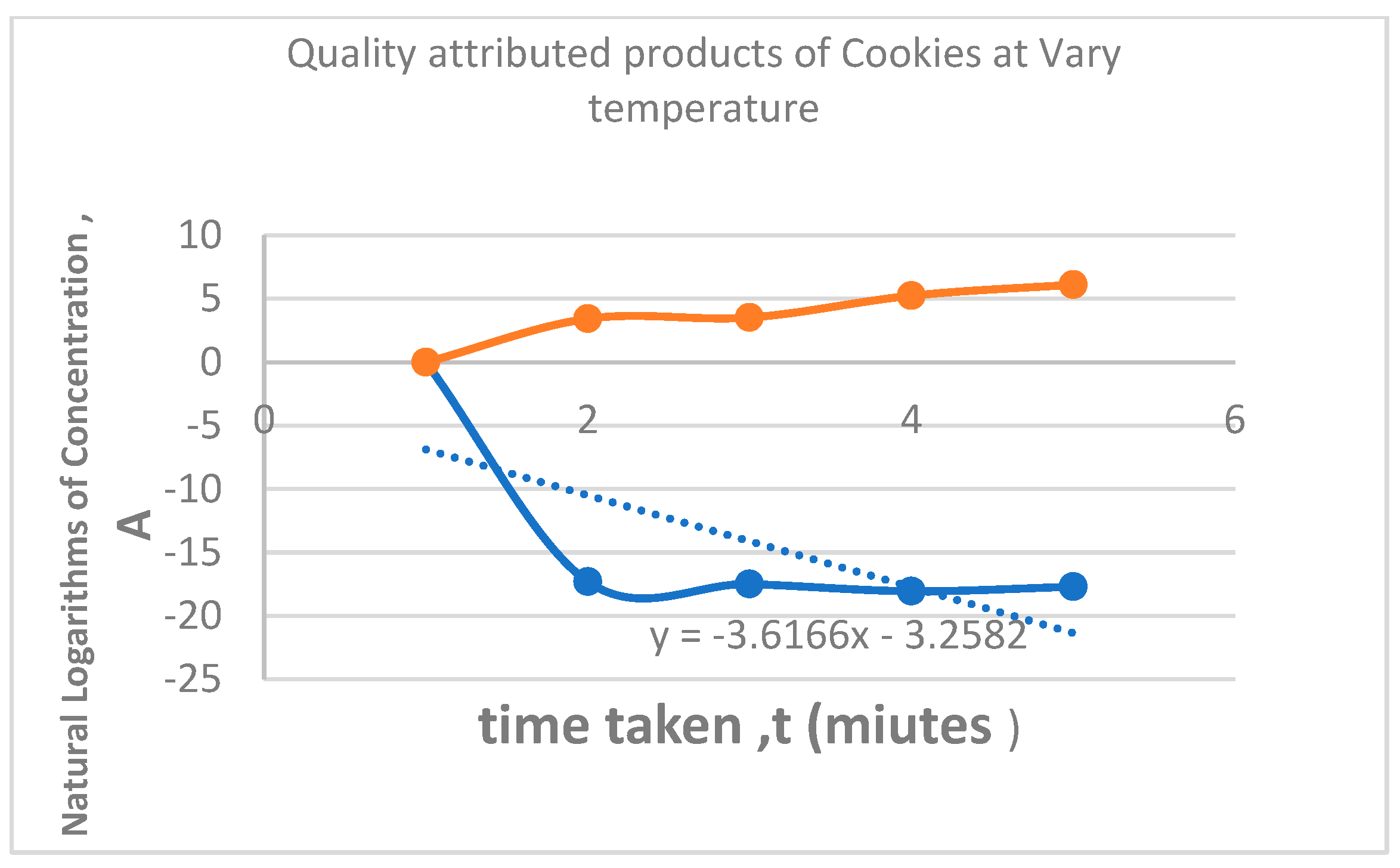

| Quality Properties of Cookies at Various Temperatures | |||||||

| S/N | Temperature, 0C | Concentration of H+ in the Cookies, mol/dm3 | PH | Conductivity Mv | time, (minutes) | InA | Log K |

| 1 | 40 | 3.09 * 10-8 | 7.51 | -6 | 3.43 | -17.2925 | 1.6021 |

| 2 | 50 | 2.52 * 10-8 | 7.6 | -9 | 3.54 | -17.4964 | 1.699 |

| 3 | 60 | 1.45 * 10-8 | 7.84 | -22 | 5.26 | -18.0429 | 1.7782 |

| 4 | 70 | 2.04 * 10-8 | 7.69 | -17 | 6.13 | -17.7077 | 1.8451 |

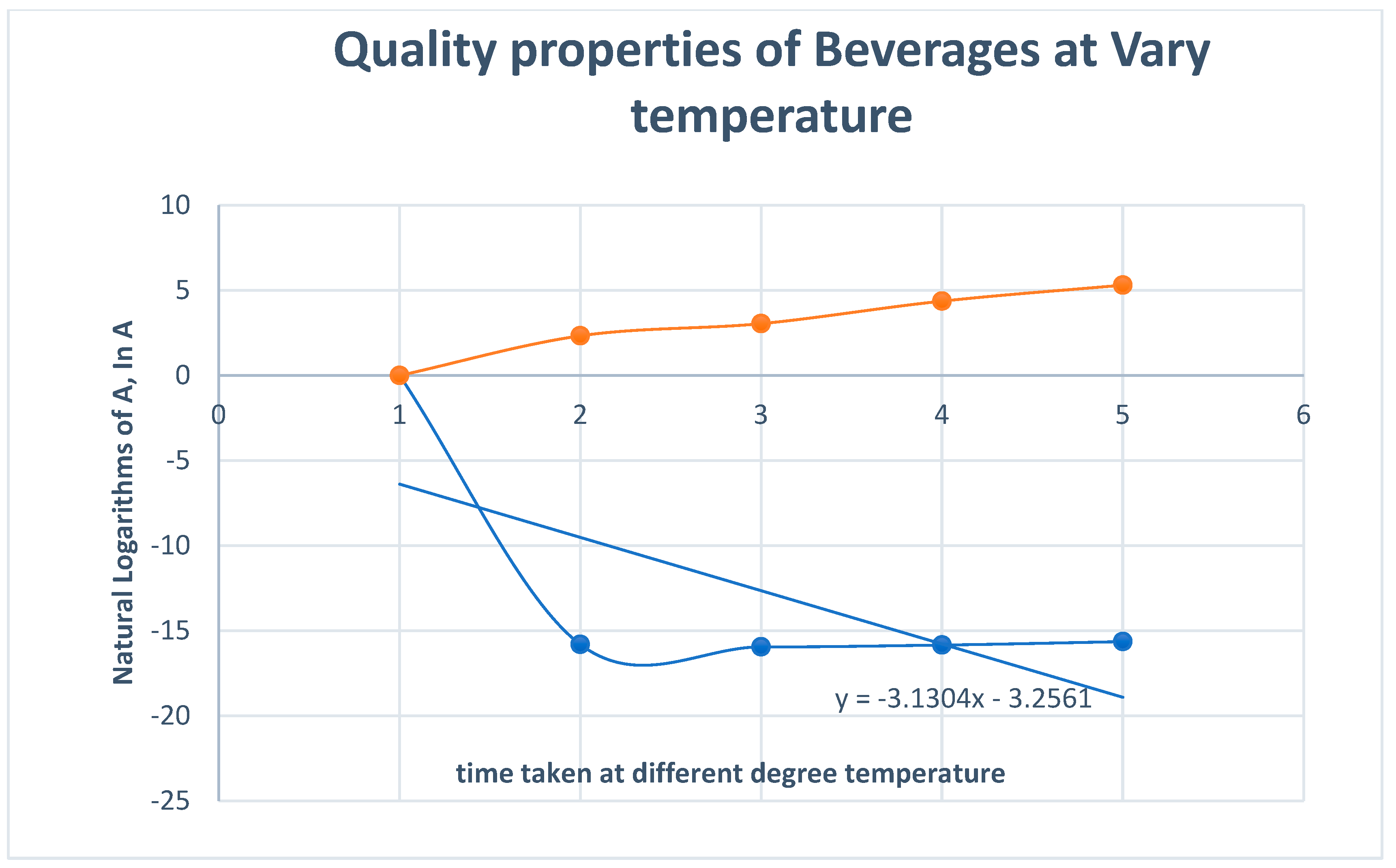

| Quality Properties of Beverages at Various Temperatures | |||||||

| S/N | Temperature 0C | Concentration of H+ in the Beverages, mol/dm3 | PH | Conductivity, Mv | time, (minutes) | InA | Log K |

| 1 | 40 | 1.38 * 10-7 | 6.87 | 25 | 2.33 | -15.818 | 1.6021 |

| 2 | 50 | 1.18 *10-7 | 6.93 | 23 | 3.05 | -15.9526 | 1.699 |

| 3 | 60 | 1.32*10-7 | 6.88 | 26 | 4.37 | -15.8404 | 1.7782 |

| 4 | 70 | 1.62 *10-7 | 6.79 | 30 | 5.31 | -15.636 | 1.8451 |

|

S/N Quality properties of Granules at various temperature |

Temperature 0C | PH Concentration of H+, |

Conductivity, mV | time (minutes) | InA | Log K | |

| 1 | 40 | 4.37 *10-7 | 6.36 | 49 | 3.37 | -14.6424 | 1.6021 |

| 2 | 50 | 4.71 *10-7 | 6.38 | 50 | 4 | -14.5684 | 1.699 |

| 3 | 60 | 4.71 *10-7 | 6.38 | 51 | 5.24 | -14.5684 | 1.7782 |

| 4 | 70 | 3.99 *10-7 | 6.4 | 53 | 6.3 | -14.7343 | 1.8451 |

|

Products |

Concentration |

PH |

Density g/cm3 |

Conductivity |

Storage Condition |

| Cookies | 1.06 * 10-7 | 6.91 | 0.999 | 18 | 250C /≥ |

| Granules | 3.82 * 10-7 | 6.42 | 0.963 | 44 | 80C |

| Beverages | 2.89 * 10-7 | 4.54 | 0.981 | 135 | 250C |

|

Microbiological Analysis |

UNIT |

SAMPLES (F, G, H) |

STANDARD (NIS 554:2015) |

METHOD OF ANALYSIS |

| Total Viable Count (Bacteria) | cfu/g | 1 x 102 | 1 x 103 | “Total Viable Count |

| Yeast Count | cfu/g | NIL | 1x 103 | “Total Viable Count |

| Mould Count | cfu/g | NIL | 1 x 103 | “Total Viable Count |

| Total Coliform Count | cfu/g | ND | 1 x 102 | “Total Viable Count |

| E-coli count | cfu/g | ND | 10 | “Total Viable Count |

| Salmonella spp. | cfu/g | NIL | NIL | “Total Viable Count |

| Shigella spp. | cfu/g | NIL | NIL | “Total Viable Count |

| Staphylococcus | cfu/g | NIL | NIL | “ Total Viable Count |

| Clostridium | cfu/g | NIL | NIL | “ Total Viable Count |

|

Microbiological Analysis |

UNIT |

SAMPLES (F,G, H) |

STANDARD (NIS 554:2015) |

METHOD OF ANALYSIS |

| Total Viable Count (Bacteria) | cfu/g | 1 x 10 | 1 x 103 | “Total Viable Count |

| Yeast Count | cfu/g | NIL | 1x 103 | “Total Viable Count |

| Mould Count | cfu/g | NIL | 1 x 103 | “ Total Viable Count |

| Total Coliform Count | cfu/g | ND | 1 x 102 | “Total Viable Count |

| E-coli count | cfu/g | ND | 10 | “Total Viable Count |

| Salmonella spp. | cfu/g | NIL | NIL | “Total Viable Count |

| Shigella spp. | cfu/g | NIL | NIL | “Total Viable Count |

| Staphylococcus | cfu/g | NIL | NIL | “ Total Viable Count |

| Clostridium | cfu/g | NIL | NIL | “ Total Viable Count |

|

Compound |

Yield (%) |

Purity (%) |

Shelf-life |

Scalability |

| Rosmarinic Acid | ~75% | ~85% | ~1.6 years | Moderate – requires multiple extraction & crystallization steps, yields relatively high |

| Carnosic Acid | ~85% | ~99.5% | ~5 years | High – higher yield, higher purity, stable crystallization, scalable to industrial quantities |

3.5.2. Figures

4. Discussion

4.1. Validation of Optimized and Scalable Extraction Protocols

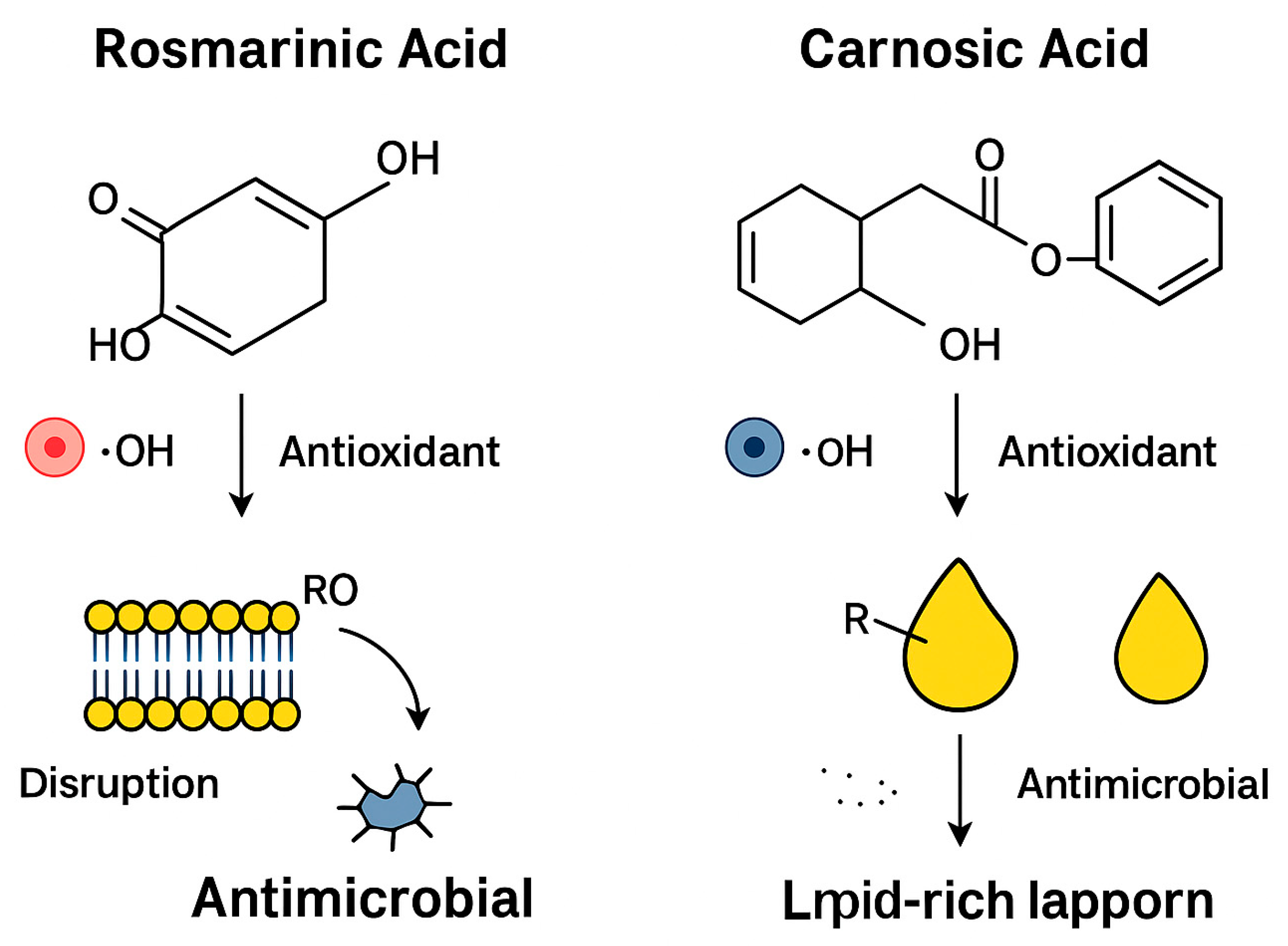

4.2. Superior Efficacy in Food Preservation: Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Synergy

4.3. Demonstrated Safety and Promising Nutraceutical Potential

4.4. Comparative Analysis and Strategic Implications for Industrial Adoption

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

- Higher Yield and Purity

- Greater Antimicrobial Efficacy

- Longer Shelf-Life (both as a compound and in fortified products)

- More Favorable and Scalable Extraction Process

Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Begum, A.; Sandhya, S.; Ali, S.S.; Vinod, K.R.; Reddy, S.; Banji, D. An in-depth review on the medicinal flora Rosmarinus officinalis (Lamiaceae). Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria 2013, 12, 61–73.

- Petersen, M., & Simmonds, M. S. (2003). Rosmarinic acid. Phytochemistry, 62(2), 121-125.

- Shakeri, A.; Sahebkar, A.; Javadi, B. Melissa officinalis L. – A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 188, 204–228. [CrossRef]

- Nieto, G.; Ros, G.; Castillo, J. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis, L.): A Review. Medicines 2018, 5, 98. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, S.Y. Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Compounds in Selected Herbs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5165–5170. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Camargo, A.d.P.; Valdés, A.; Sullini, G.; García-Cañas, V.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibáñez, E.; Herrero, M. Two-step sequential supercritical fluid extracts from rosemary with enhanced anti-proliferative activity. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 11, 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, N.; Sierra, H.; Carvajal, L.; Delpiano, P.; Günther, G. Fast high performance liquid chromatography and ultraviolet–visible quantification of principal phenolic antioxidants in fresh rosemary. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1100, 20–25. [CrossRef]

- Almela, L.; Sánchez-Muñoz, B.; Fernández-López, J.A.; Roca, M.J.; Rabe, V. Liquid chromatograpic–mass spectrometric analysis of phenolics and free radical scavenging activity of rosemary extract from different raw material. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1120, 221–229. [CrossRef]

- Ivanović, M., Islamčević Razboršek, M., & Kolar, M. (2020). Innovative extraction techniques for deep eutectic solvents-based analysis of plant phenolics in food and medicinal plants. Molecules, *25*(7), 1611.

- Wang, W.; Wu, N.; Zu, Y.; Fu, Y. Antioxidative activity of Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil compared to its main components. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 1019–1022. [CrossRef]

- Syarifah, A.N.; Suryadi, H.; Mun’iM, A. Validation of Rosmarinic Acid Quantification using High- Performance Liquid Chromatography in Various Plants. Pharmacogn. J. 2022, 14, 165–171. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Smuts, J.P.; Dodbiba, E.; Rangarajan, R.; Lang, J.C.; Armstrong, D.W. Degradation Study of Carnosic Acid, Carnosol, Rosmarinic Acid, and Rosemary Extract (Rosmarinus officinalisL.) Assessed Using HPLC. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9305–9314. [CrossRef]

- Meziane-Assami, D.; Tomao, V.; Ruiz, K.; Meklati, B.Y.; Chemat, F. Geographical Differentiation of Rosemary Based on GC/MS and Fast HPLC Analyses. Food Anal. Methods 2012, 6, 282–288. [CrossRef]

- Borrás Linares, I., Arráez-Román, D., Herrero, M., Ibáñez, E., Segura-Carretero, A., & Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. (2011). Comparison of different extraction procedures for the comprehensive characterization of bioactive phenolic compounds in rosemary leaves. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, *54*(5), 1028-1036.

- Kontogianni, V.G.; Tomic, G.; Nikolić, I.; Nerantzaki, A.A.; Sayyad, N.; Stosic-Grujicic, S.; Stojanović, I.; Gerothanassis, I.P.; Tzakos, A.G. Phytochemical profile of Rosmarinus officinalis and Salvia officinalis extracts and correlation to their antioxidant and anti-proliferative activity. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 120–129. [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; He, K.; Roller, M.; Zheng, B.; Chen, X.; Shao, Z.; Peng, T.; Zheng, Q. Active Compounds from Lagerstroemia speciosa, Insulin-like Glucose Uptake-Stimulatory/Inhibitory and Adipocyte Differentiation-Inhibitory Activities in 3T3-L1 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11668–11674. [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Wu, X.; Schaich, K. Standardized Methods for the Determination of Antioxidant Capacity and Phenolics in Foods and Dietary Supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4290–4302. [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 933–956. [CrossRef]

- Foti, M. C. (2007). Antioxidant properties of phenols. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, *59*(12), 1673-1685.

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The Chemistry behind Antioxidant Capacity Assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [CrossRef]

- Rota, M.C.; Herrera, A.; Martínez, R.M.; Sotomayor, J.A.; Jordán, M.J. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of Thymus vulgaris, Thymus zygis and Thymus hyemalis essential oils. Food Control. 2008, 19, 681–687. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.; Barry-Ryan, C.; Bourke, P. The antimicrobial efficacy of plant essential oil combinations and interactions with food ingredients. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 124, 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Oluwatuyi, M., Kaatz, G. W., & Gibbons, S. (2004). Antibacterial and resistance-modifying activity of Rosmarinus officinalis. Phytochemistry, *65*(24), 3249-3254.

- Rožman, T., & Jeršek, B. (2009). Antimicrobial activity of rosemary extracts (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) against different species of Listeria. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica, *93*(1), 51-58.

- Moreno, S.; Scheyer, T.; Romano, C.S.; Vojnov, A.A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of rosemary extracts linked to their polyphenol composition. Free. Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 223–231. [CrossRef]

- Sotelo-Félix, J.; Martinez-Fong, D.; Muriel, P.; Santillán, R.; Castillo, D.; Yahuaca, P. Evaluation of the effectiveness of Rosmarinus officinalis (Lamiaceae) in the alleviation of carbon tetrachloride-induced acute hepatotoxicity in the rat. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 145–154. [CrossRef]

- Rašković, A.; Milanović, I.; Pavlović, N.; Ćebović, T.; Vukmirović, S.; Mikov, M. Antioxidant activity of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) essential oil and its hepatoprotective potential. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 225–225. [CrossRef]

- Satoh, T.; Kosaka, K.; Itoh, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Shimojo, Y.; Kitajima, C.; Cui, J.; Kamins, J.; Okamoto, S.; et al. Carnosic acid, a catechol-type electrophilic compound, protects neurons both in vitro and in vivo through activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway via S-alkylation of targeted cysteines on Keap1. J. Neurochem. 2008, 104, 1116–1131. [CrossRef]

- Bakırel, T.; Bakırel, U.; Keleş, O.Ü.; Ülgen, S.G.; Yardibi, H. In vivo assessment of antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) in alloxan-diabetic rabbits. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 64–73. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Yousef, M.; Tsiani, E. Anticancer Effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Extract and Rosemary Extract Polyphenols. Nutrients 2016, 8, 731. [CrossRef]

- González-Vallinas, M.; Molina, S.; Vicente, G.; Zarza, V.; Martín-Hernández, R.; García-Risco, M.R.; Fornari, T.; Reglero, G.; de Molina, A.R. Expression of MicroRNA-15b and the Glycosyltransferase GCNT3 Correlates with Antitumor Efficacy of Rosemary Diterpenes in Colon and Pancreatic Cancer. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e98556. [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M.; Cava, R. Effectiveness of rosemary essential oil as an inhibitor of lipid and protein oxidation: Contradictory effects in different types of frankfurters. Meat Sci. 2006, 72, 348–355. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., Zhang, X., True, A. D., & Zhou, L. (2013). Inhibition of lipid oxidation in foods and biological systems by polyphenols. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, *4*, 275-297.

- Falowo, A.B.; Fayemi, P.O.; Muchenje, V. Natural antioxidants against lipid–protein oxidative deterioration in meat and meat products: A review. Food Res. Int. 2014, 64, 171–181. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: Antioxidant activity and health effects – A review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 820–897. [CrossRef]

- Carocho, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. A review on antioxidants, prooxidants and related controversy: Natural and synthetic compounds, screening and analysis methodologies and future perspectives. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 15–25. [CrossRef]

- Embuscado, M.E. Spices and herbs: Natural sources of antioxidants – a mini review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 811–819. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Inaba, Y.; Takeda, Y. Antioxidant Mechanism of Carnosic Acid: Structural Identification of Two Oxidation Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5560–5565. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, K.; Bertelsen, G.; Nissen, L.R.; Gardner, P.T.; Heinonen, M.I.; Hopia, A.; Huynh-Ba, T.; Lambelet, P.; McPhail, D.; Skibsted, L.H.; et al. Investigation of plant extracts for the protection of processed foods against lipid oxidation. Comparison of antioxidant assays based on radical scavenging, lipid oxidation and analysis of the principal antioxidant compounds. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 212, 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Frankel, E. In search of better methods to evaluate natural antioxidants and oxidative stability in food lipids. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1993, 4, 220–225. [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Sun, S.; Canning, C.; Zhou, K. Antioxidant rich grape pomace extract suppresses postprandial hyperglycemia in diabetic mice by specifically inhibiting alpha-glucosidase. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 7, 71–71. [CrossRef]

- BAM: FDA’s Bacteriological Analytical Manual. (Chapter 3: Aerobic Plate Count).

- BAM: FDA’s Bacteriological Analytical Manual. (Chapter 4: Enumeration of Escherichia coli and the Coliform Bacteria).

- BAM: FDA’s Bacteriological Analytical Manual. (Chapter 5: Salmonella).

- ISO 4833-1:2013. Microbiology of the food chain — Horizontal method for the enumeration of microorganisms — Part 1: Colony count at 30 degrees C by the pour plate technique.

- ISO 21528-2:2017. Microbiology of the food chain — Horizontal method for the detection and enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae — Part 2: Colony-count technique.

- Aruoma, O. I., Spencer, J. P., Rossi, R., Aeschbach, R., Khan, A., Mahmood, N., ... & Halliwell, B. (1996). An evaluation of the antioxidant and antiviral action of extracts of rosemary and Provençal herbs. Food and Chemical Toxicology, *34*(5), 449-456.

- Fischedick, J.T.; Standiford, M.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Structure activity relationship of phenolic diterpenes from Salvia officinalis as activators of the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 pathway. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 2618–2622. [CrossRef]

- Rasoulian, B.; Hajializadeh, Z.; Esmaeili-Mahani, S.; Rashidipour, M.; Fatemi, I.; Kaeidi, A. Neuroprotective and antinociceptive effects of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extract in rats with painful diabetic neuropathy. J. Physiol. Sci. 2018, 69, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, J.; Yamada, K.; Naemura, A.; Yamashita, T.; Arai, R. Testing various herbs for antithrombotic effect. Nutrition 2005, 21, 580–587. [CrossRef]

- Kashiwada, Y.; Nagao, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Ikeshiro, Y.; Okabe, H.; Cosentino, L.M.; Lee, K.-H. Anti-AIDS Agents 38. Anti-HIV Activity of 3-O-Acyl Ursolic Acid Derivatives. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1619–1622. [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, K.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Farzinia, M.M.; Ahmadi, M. (2017). Effect of Phenological Stages on Essential Oil Content, Composition, and Rosmarinic Acid in Rosmarinus officinalis L. International Journal of Horticultural Science and Technology, *4*(2), 251-258.

- Romano, C.S.; Abadi, K.; Repetto, V.; Vojnov, A.A.; Moreno, S. Synergistic antioxidant and antibacterial activity of rosemary plus butylated derivatives. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 456–461. [CrossRef]

- López, V.; Martín, S.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P.; Carretero, M.E.; Jäger, A.K.; Calvo, M.I. Neuroprotective and neurochemical properties of mint extracts. Phytotherapy Res. 2010, 24, 869–874. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.; Wang, M.; Wei, G.; Huang, T.; Huang, M. Chemistry and antioxidative factors in rosemary and sage. BioFactors 2000, 13, 161–166. [CrossRef]

- Cuvelier, M.; Richard, H.; Berset, C. Antioxidative activity and phenolic composition of pilot-plant and commercial extracts of sage and rosemary. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1996, 73, 645–652. [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, C.; Tarantilis, P.A.; Kokotou, M.G. Carnosic Acid and Carnosol: Analytical Methods for Their Determination in Plants, Foods and Biological Samples. Separations 2023, 10, 481. [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, A.; Petrova, A.; Teneva, D.; Ognyanov, M.; Georgiev, Y.; Nenov, N.; Denev, P. Subcritical Water Extraction of Rosmarinic Acid from Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis L.) and Its Effect on Plant Cell Wall Constituents. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 888. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).