Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Method

Collection and Identifcation of Seaweed

Preparation C. racemosa Juice

Preparation of C. racemosa Extract

1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity assay

Total phenolic content (TPC)

Sensory Analyses

Fiber Content of Formulated Juices

Vitamin C content of Formulated Juices

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) Analysis

In Silico Studies

Ligand and Target Protein Selection

Pharmacokinetic Properties

Molecular Docking dan Visualisasi

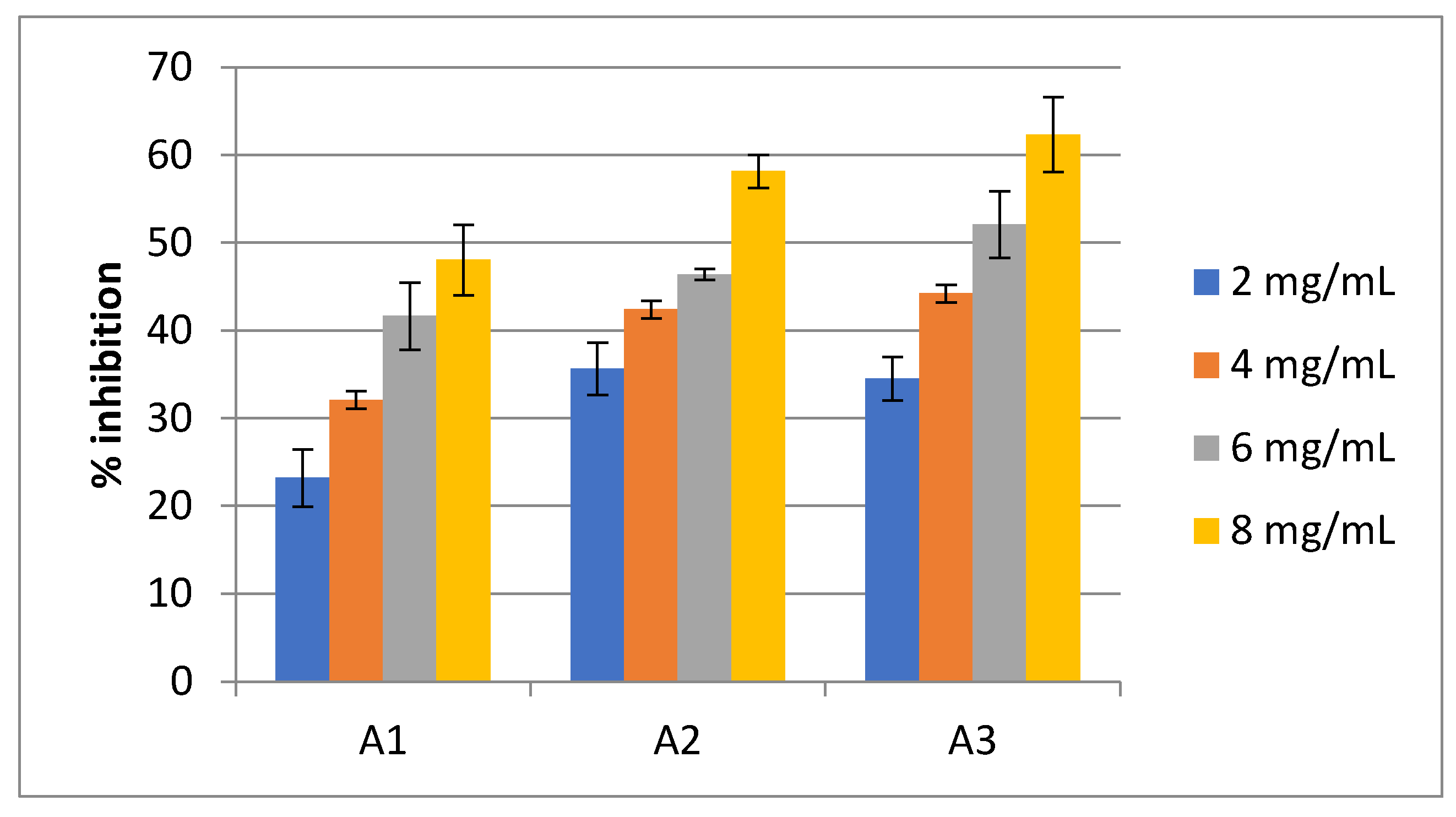

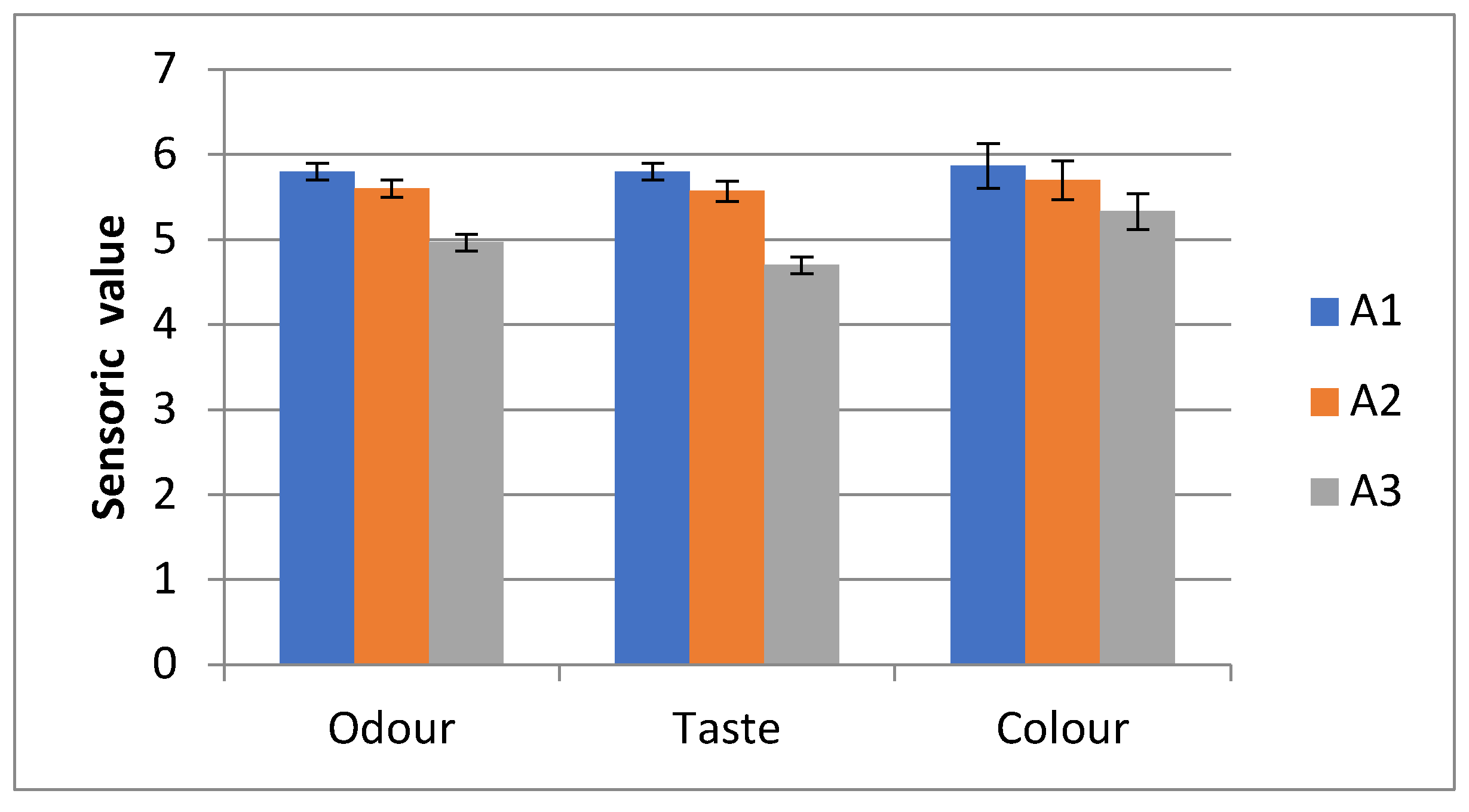

Result and Discussion

Juice of Seaweed

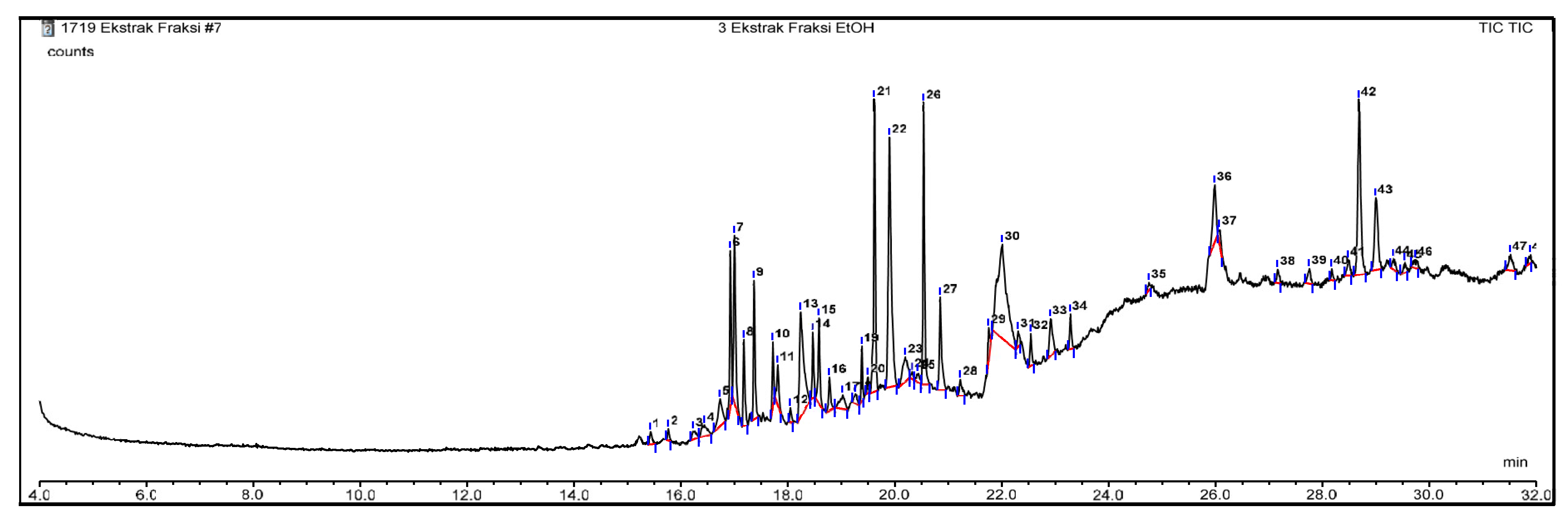

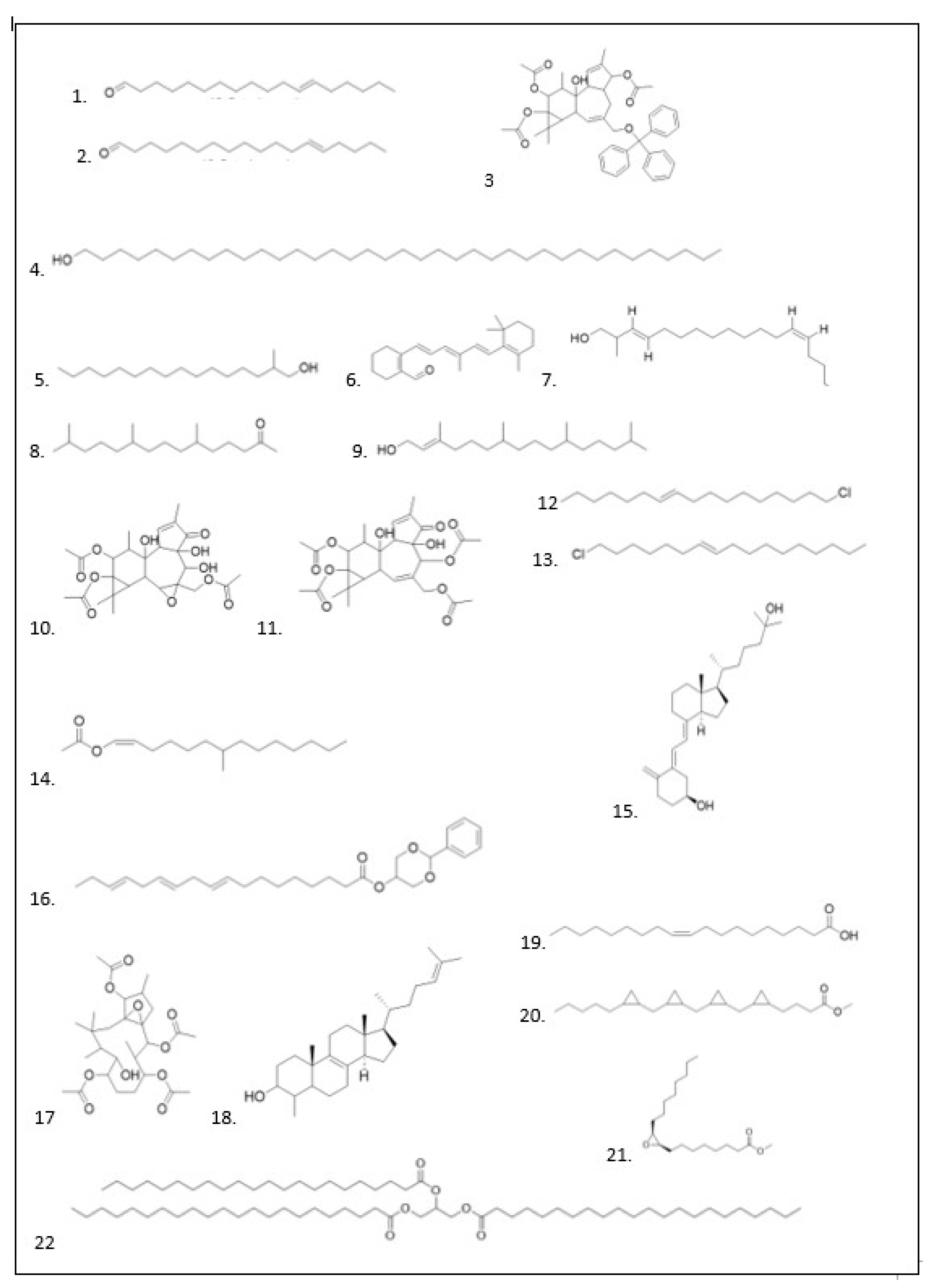

GC–MS Analysis

3. Evaluation of Molecular Docking

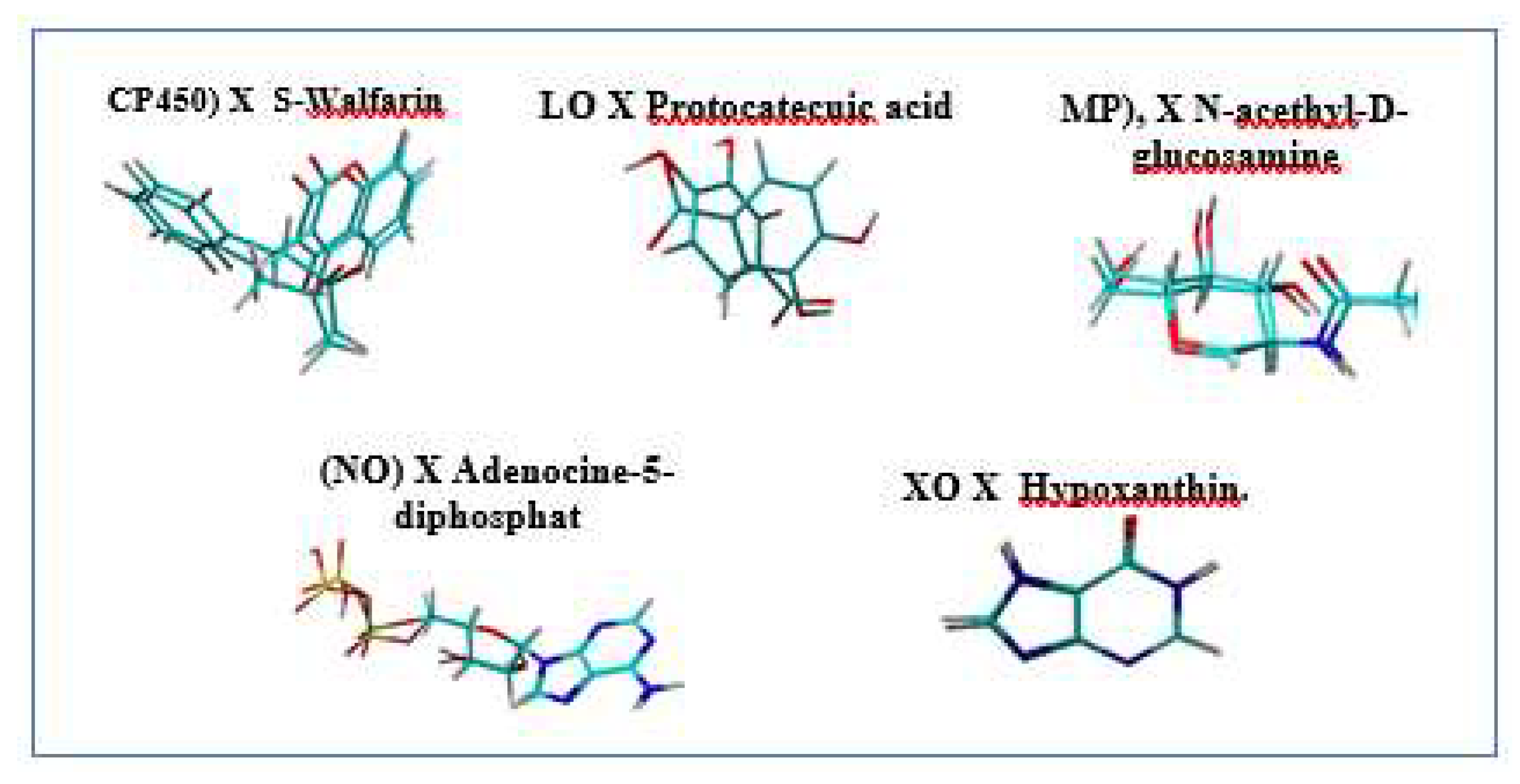

Validation of Protein Target

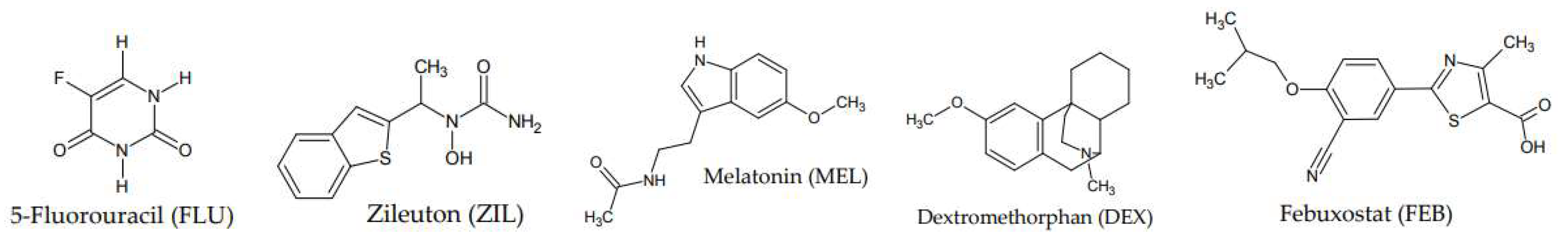

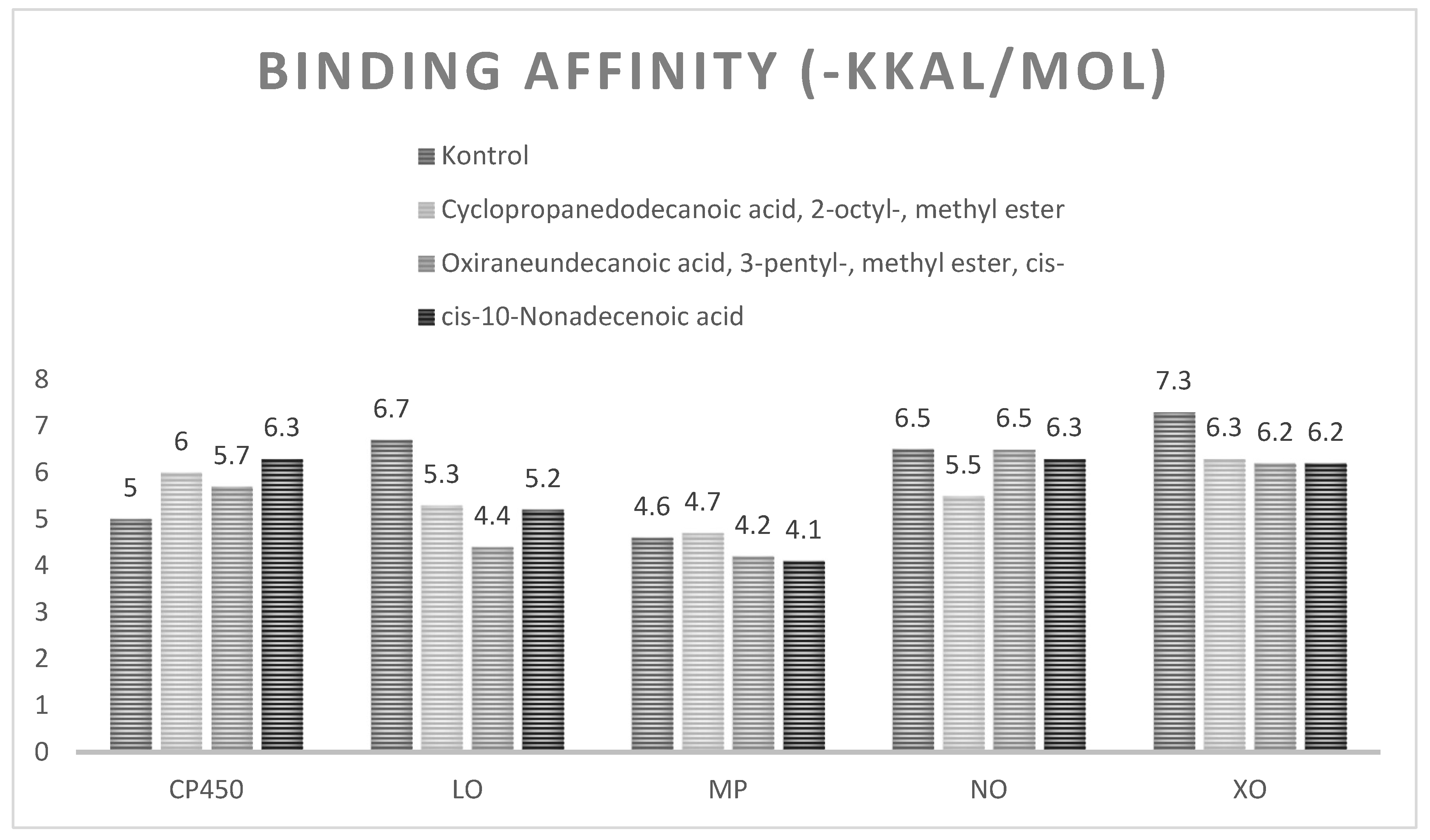

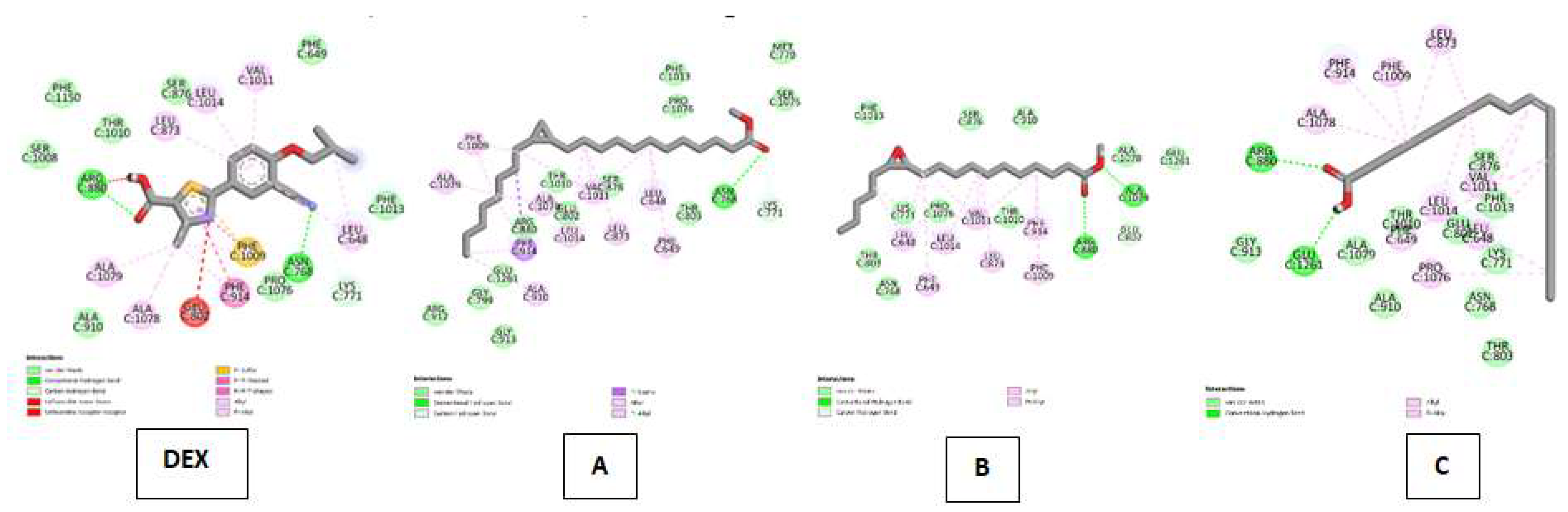

Molecular Docking Studies of Proteins with Bioactive Compound

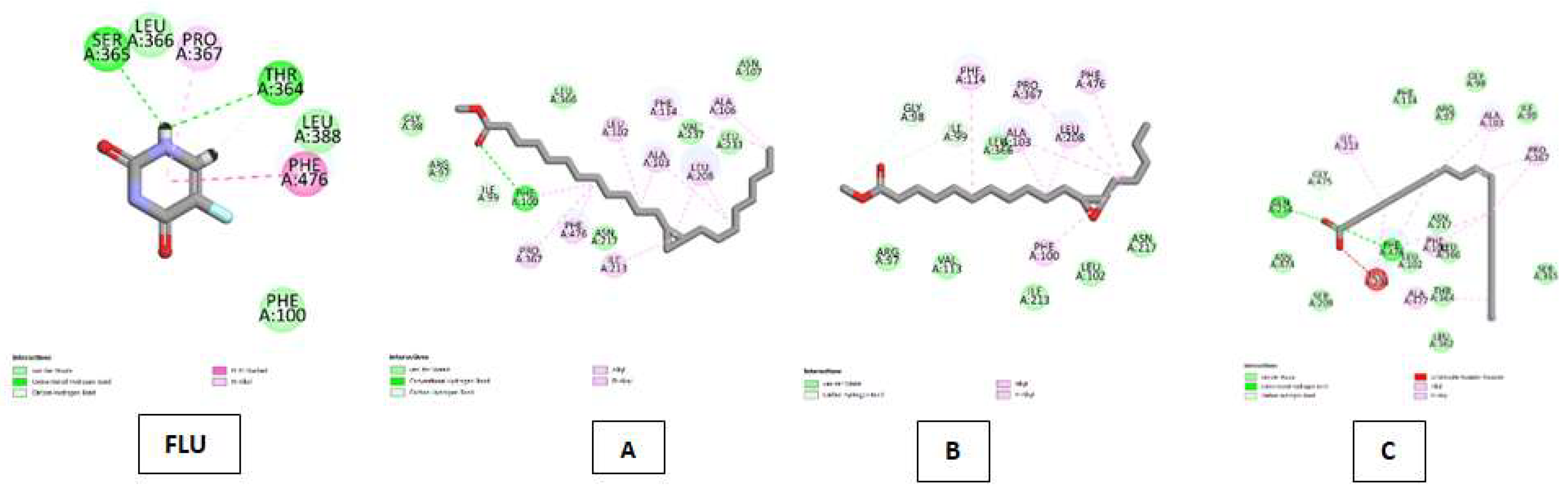

| Reseptor | Ligan | Asam amino yang berinteraksi |

|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome P450 (CP450) Kode PDB : 1OG5 Gambar 5 |

5-fluorouracil (FLU) | Van Der Waals :LEU A: 366, LEU A: 388, PHE A:100 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : SER A:365, THR A:364 ; Carbon Hydrogen Bond :THR A:364 ; Pi-Pi Stacked : PHE A:476 ; Pi-Alkyl : PRO A:367. |

| Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | Van Der Waals : GLY A:98, ARG A:97, ASN A:2017, LEU A:366, VAL A:237, LEU A:233, ASN A:107 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : PHE A:100 ; Carbon Hydrogen Bond : ILE A:99, Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :PHE A:476, PRO A:367, ILE A:213, LEU A:208, ALA A:103, LEU A:102, PHE A:114, ALA A:106 | |

| Oxiraneundecanoic acid, 3-pentyl-, methyl ester, cis- | Van Der Waals : ARG A:97, VAL A:113, ILE A:213, LEU A:102, ASN Al2017, LEU A:366 ; Carbon Hydrogen Bond : GLY A:98, ILE A:99 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl : PHE A:114, ALA A:103, LEU A:208, PRO A:367, PHE A:476. | |

| cis-10-Nonadecenoic acid | Van Der Waals : SER A:209, ASN A:474, GLY A:475, PHE A:114, ARG A:97, GLY A:98, ILE A:99, SER A:365, LEU A:362, THR A:364, LEU A:366, ASN A:217, LEU A :102 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : GLN A:214, PHE A:476 ; Unfavorable Acceptor-Acceptor : LEU A:208, Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :ILE A:213, ALA A:103, PRO A:367, PHE A:100, ALA A:477 | |

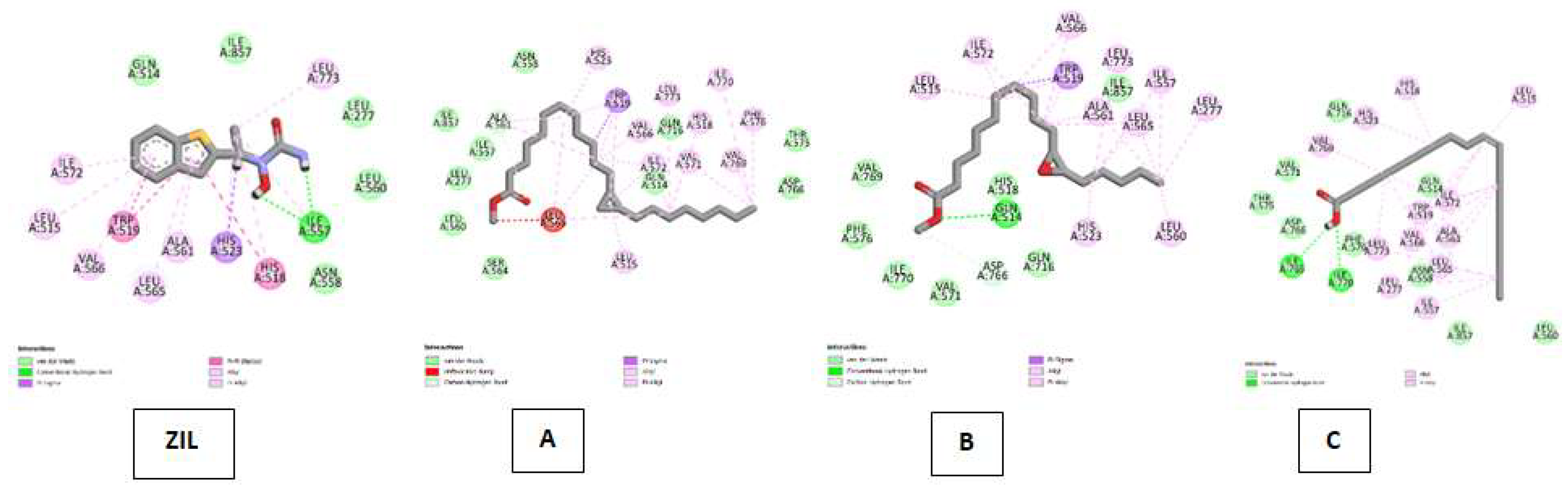

| Lipoxygenase (LO) Kode PDB : 1N8Q Gambar 6 |

Zileuton (ZIL) | Van Der Waals :ILE A: 857, GLN A:514, ASN A : 558, LEU A:560, LEU A:277 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : ILE A:557 ; Pi-Sigma : HIS A:523 ; Pi-Pi Stacked : HIS A:518, TRP A:519 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl : HIS A:518, LEU A:773, HIS A: 523, ILE A:557, LEU A : 565, ALA A:561, ILE A:572, VAL A:566, LEU A:515 |

| Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | Van Der Waals : SER A:564, LEU A:560, LEU A:557, ILE A:857, ASN A:558,GLN A:716, GLN A:514, THR A:575, ASP A:766 ; Carbon Hydrogen Bond : ALA A:561, Unfavorable Bump : LEU A:565, Pi-Sigma ; TRP A:519 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :LEU A:515, HIS A:523, VAL; A:566, ILE A:572, VAL A:571, VAL A:566, LEU A:773, HIS A:518, ILE A:770, VAL:769 | |

| Oxiraneundecanoic acid, 3-pentyl-, methyl ester, cis- | Van Der Waals : VAL A:769, PHE A:576, ILE A:770, VAL A:571, HIS A:518, GLN A:716, ILE A:857 ; Carbon Hydrogen Bond :ASP A:766 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : GLN A:514 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :LEU A:515, ILE A:572, VAL A:566, LEU A:773, ALA A:561M LEU A:565, HIS A:523, LEU A:560,LEU A:773, ALA A:561, LEU A:565, LRU A:560 | |

| cis-10-Nonadecenoic acid | Van Der Waals : LEU A:560, ILE A:857, ASN A:558, GLN A:514, PHE A:576, ASP A:776, THR A:575, VAL A:571, GLN A:716 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond :ILE A:765, ILE A 770 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :VAL A:769, HIS A:523, HIS A:518, LEU A:515, ILE A:572, TRP A:519, VAL A:566, ALA :561, LEU A:565, LEU A:773, LEU A:277, ILE A:557. | |

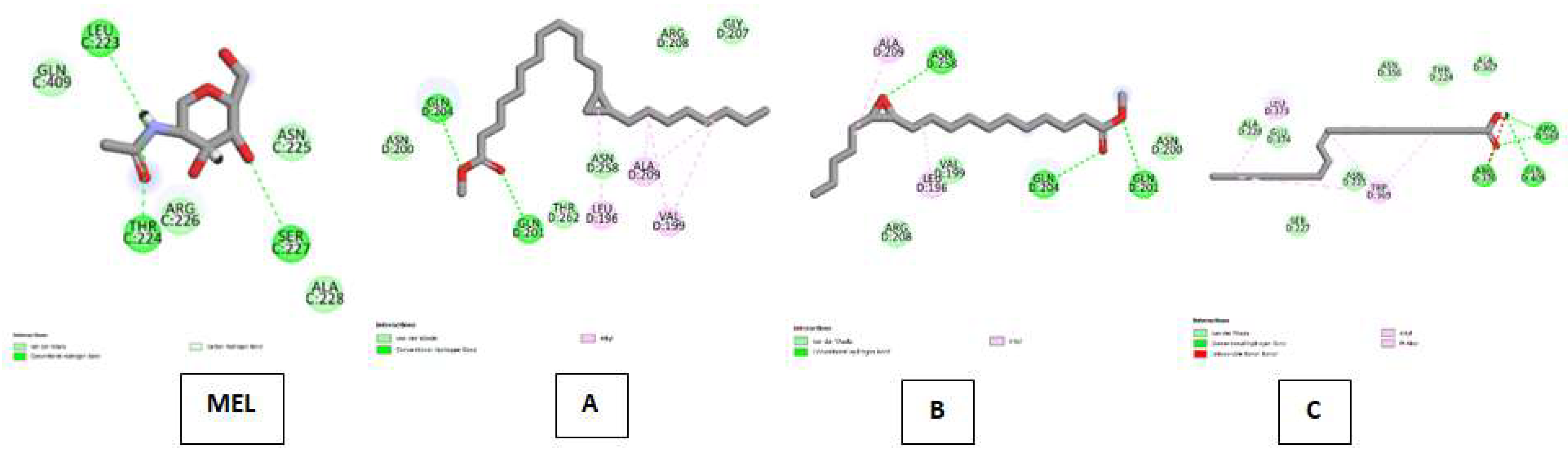

| Myeloperoxidase (MP) Kode PDB : 1DNU Gambar 7 |

Melatonin (MEL) | Van Der Waals : ALA C:228, ASN C:255, ARG C:226, GLN C:409 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : SER C:227, THR C:224, LEU C:223, |

| Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | Van Der Waals : ASN D:200, THR D:262, ASN D:258, ARG D:208, GLY D:207 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : GLN D:204, GLN D:201 ; Alkyl : ALA D:209, LEU D:196, VAL D:199 | |

| Oxiraneundecanoic acid, 3-pentyl-, methyl ester, cis- | Van Der Waals : VAL D:199, ARG D:208, ASN D:200 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond :ASN D:258, GLN D:204, GLN D:201 ; Alkyl : ALA D:209, LEU D:196 | |

| cis-10-Nonadecenoic acid | Van Der Waals : ALA D:228, GLU D:374, SER D:227, ASN D:225, ASN D:356, THR D:224, ALA D:367 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : ARG D:363, GLN D:409, ARG D:370 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :LEU D:373, TRP D:369. | |

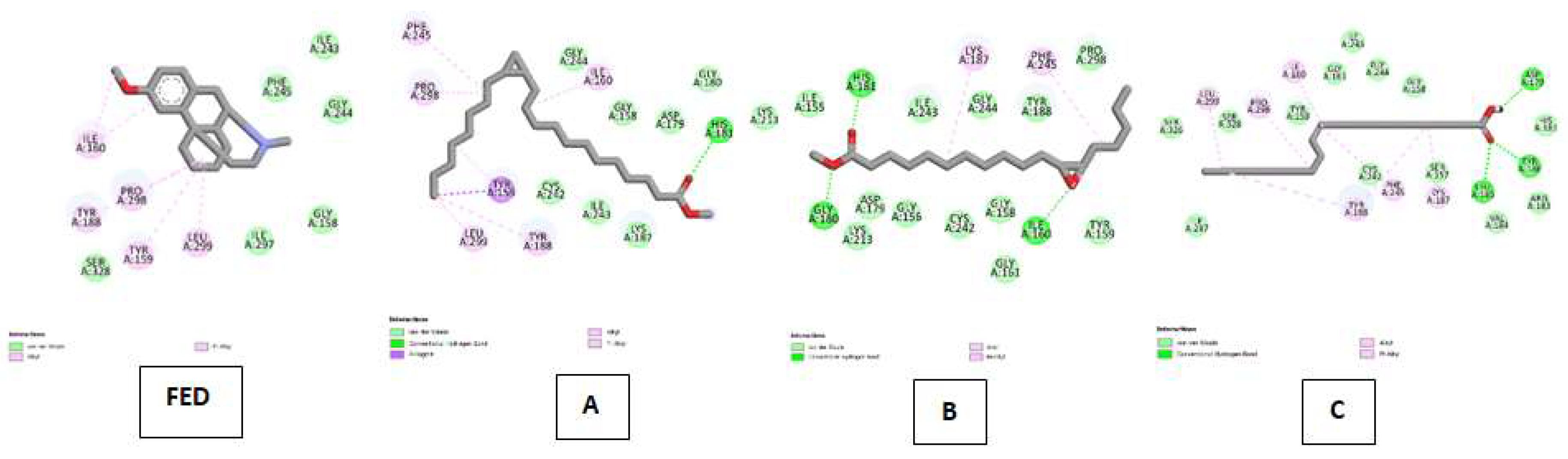

| NADPH oxidase (NO) Kode PDB : 2CDU Gambar 8 |

Dextromethorphan (DEX) | Van Der Waals :ILE A:243, PHE A:245, GLY A:244, GLY A:158, ILE A:297, SER A:328 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl : ILE A:160, PRO A:298, TYR A:188, TYR A:159, LEU A:299 |

| Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | Van Der Waals : CYS A:242, ILE A:243, LYS A:187, LYS A:213, GLY A:180, ASP A:179, GLY A:158, GLY A:244 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond :HIS A:181 ; Pi-Sigma : TYR A:159 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :ILE A:160, PHE A:245, PRO A:298, TYR A:188, LEU A:299 | |

| Oxiraneundecanoic acid, 3-pentyl-, methyl ester, cis- | Van Der Waals : LYS A:213, ASP A:179, GLY A:156, CYS A:242, GLY A:158, GLY A:161, TYR A:159, PRO A:298, TYR A:188, GLY A:244, ILE A:243, ILE A:155 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond :HIS A:181, GLY A:180 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :LYS A:187, PHE A:245. | |

| cis-10-Nonadecenoic acid | Van Der Waals : ILE A: 297, SER A:326, SER A:328, THYR A:159, GLY A:161, ILE A:243, GLY A:244, GLY A:158, CYS 242, SER A:157, VAL A:184, ARG A:183 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : TYR A:186, LEU A:185 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :LEU A:299, PRO A:298, ILE A:160, TYR A:188, PHE 245, LYS 187. | |

| Xanthine oxidase (XO) Kode PDB: 3NRZ Gambar 9 |

Febuxostat (FEB) | Van Der Waals : ALA C:910, SER C:1008, PHE C:1150, THR C:1010, SER C:876, PHE C:1013, PHE C:649, PRO C:1076 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : ASN C:768, ARG C:880 ; Carbon Hydrogen Bond : LYS C:771 ; Unfavorable Donor-Donor : GLU C:802 ; Unfavorable Acceptor-Acceptor : ARG C:880 ; Pi-Sulfur : PHE C:1009, Pi-Pi Stacked : PHE C:1009; Pi-Pi T-shaped : PHE C:1009 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl : ALA C:1079, ALA C:1078, PHE C:1009, LEU C:648, LEU C:873, LEU C:1014, VAL C:1011 |

| Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | Van Der Waals : ARG C:912, GLY C:913, GLY C:799, GLU C:1261, ARG C:880, GLU C:802, THR C:1010, SER C:876, THR C:803, SER C:1075, MET C:770, PHE C:1013, PRO C:1076 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : ASN C:768 ; Carbon Hydrogen Bond : LYS C:771 ; Pi-SigmaI :PHE C:914 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :ALA C:910, ALA C:1079, PHE C:1009, ALA C:1078, LEU C:1014, VAL C:1011, LEU C:873, PHE C:649, LEU C:648. | |

| Oxiraneundecanoic acid, 3-pentyl-, methyl ester, cis- | Van Der Waals : PHE C:1013, SER C:876, ALA C:910, ALA C:1078, FLU C:1261, THR C:1010, PRO C:1076, LYS C:771, THR C:803, ASN C:768 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : ARG C:880 ; Carbon Hydrogen Bond : GLU C:802 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :LEU C:648, PHE C:649, LEU C:1014, VAL C:1011, PHE C:914, PHE C:1009 | |

| cis-10-Nonadecenoic acid | Van Der Waals : GLY C:913, ALA C:1079, THR C:1010, GLU C:802, ALA C:910, ASN 768, THR C:803, LYS C:771, PHE C:1013, SER C:876 ; Conventional Hydrogen Bond : GLU C:1261, ARG C:880 ; Alkyl & Pi-Alkyl :ALA C:1078, PHE C:914, PHE C:1009, LEU C:873, VAL C:1011, LEU 648, LEU C:1014, PHE C:649, PRO C:1076. |

Pharmacokimetic Properties

Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindah, E.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1-2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, M.; Furtmüller, P.G.; Regelsberger, G.; Turco-Liveri, M.L.; Tesoriere, L.; Perretti, M.; Livrea, M.A.; Obinger, C. Mechanism of reaction of melatonin with human myeloperoxidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 282, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemist). Official Method of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical of Chemist Arlington; The Association of Official Analytical Chemist, Inc., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bayro, A.M.; Manlusoc, J.K.; Alonte, R.; Caniel, C.; Conde, P.; Embralino, C. Preliminary chracterization, antioxidant and antiproliferative properties of polysaccharide from Caulerpa taxifolia. Pharm Sci Res. 2021, 8, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Blair-Johnson, M.; Fiedler, T.; Fenna, R. Human myeloperoxidase: Structure of a cyanide complex and its interaction with bromide and thiocyanate substrates at 1.9 A resolution. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 13990–13997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, E. Basic mechanisms of antioxidant activity. BioFactors 1997, 6, 391–397. 6. Dharmaraja, A.T. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in therapeutics and drug resistance in cancer and bacteria. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3221–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, G.W.; Young, P.R.; Albert, D.H.; Bouska, J.; Dyer, R.; Bell, R.L.; Summers, J.B.; Brooks, D.W. 5-Lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of zileuton. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991, 256, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.E. Sensory evaluation. In Food Science and Ecologycal Epproach; Edelstein, S., Ed.; Jones & Baartlett Learning: Burlington, Massachusetts, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Corsetto, P.A.; Montorfano, G.; Zava, S.; Colombo, I.; Ingadottir, B.; Jonsdottir, R.; Sveinsdottir, K.; Rizzo, A.M. Characterization of antioxidant potential of seaweed extracts for enrichment of convenience food. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.D.S.; Ramos, R.D.S.; Costa, K.D.S.L.; Brasil, D.D.S.B.; Silva, C.H.T.D.P.D.; Ferreira, E.F.B. ,... & Santos, C.B.R.D. An in silico study of the antioxidant ability for two caffeine analogs using molecular docking and quantum chemical methods. Molecules 2018, 23, 2801. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.S.; Costa, K.S.L.; Cruz, J.V.; Ramos, R.S.; Silva, L.B.; Brasil, D.S.B.; Silva, C.H.T.P.; Santos, C.B.R.; Macêdo, W.J.C. Virtual screening and statistical analysis in the design of new caffeine analogues molecules with potential epithelial anticancer activity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.V.; Neto, M.F.A.; Silva, L.B.; da Ramos, R.; da Costa, J.; Brasil, D.S.B.; Lobato, C.C.; da Costa, G.V.; Bittencourt, J.A.H.M.; da Silva, C.H.T.P.; et al. Identification of novel protein kinase receptor type 2 inhibitors using pharmacophore and structure-based virtual screening. Molecules 2018, 23, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Science Reports 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, A.P.A.; Torres, M.R.; Pessoa, C.; et al. In vivo growthinhibition of Sarcoma 180 tumor by alginates from brown seaweed Sargassum vulgare. Carbohydrate Polymers 2007, 69, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugbank. Available online: https://www.drugbank.ca/unearth/ (accessed on 7 July 2018).

- Funahashi, H.; Imai, T.; Mase, T.; et al. Seaweed prevents breast cancer? Japanese Journal of Cancer Research 2001, 92, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funkhouser, T. Protein-Ligand Docking Methods; Princeton University New Jersey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Galijasevic, S.; Abdulhamid, I.; Abu-Soud, H.M. Melatonin is a potent inhibitor for myeloperoxidase. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 2668–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, A.R.; Tiwari, U.; Rajauria, G. Seaweed nutraceuticals and their therapeutic role in disease prevention. Food Science and Human Wellness 2019, 8, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, U.; Jayakanthan, M.; Sundar, D. Molecular docking studies of dithionitrobenzoic acid and its related compounds to protein disulfide isomerase: Computational screening of inhibitors to HIV-1 entry. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunes, A.; Coskun, U.; Boruban, C.; Gunel, N.; Babaoglu, M.O.; Sencan, O.; Bozkurt, A.; Rane, A.; Hassan, M.; Zengil, H.; et al. Inhibitory effect of 5-fluorouracil on cytochrome P450 2C9 activity in cancer patients. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006, 98, 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, A. Docking techniques in pharmacology: How much promising? Comp. Biol. Chem. 2018, 76, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Bioactive potential and possible health effects of edible brown seaweeds. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2011, 22, 315–26. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, W. New marine derived anticancer therapeutics? A journey from the sea to clinical trials. Marine Drugs 2004, 2, 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hevener, K.E.; Zhao, W.; Ball, D.M.; Babaoglu, K.; Qi, J.; White, S.W.; Lee, R.E. Validation of molecular docking programs for virtual screening against dihydropteroate synthase. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holdt, S.L.; Krann, S. Bioactive compounds in seaweed: functional food applications and legislation. Journal of Applied Phycology 2011, 23, 543–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.A. Total phenolics,flavonoids and antioxidant activity of tropical fruit pineapple. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 672–676. [Google Scholar]

- Korivi, M.; Chen, C.T.; Yu, S.H.; Ye, W.; Cheng, I.S.; Chang, J.S.; Kuo, C.H.; Hou, C.W. Seaweed supplementation enhances maximal muscular strength and attenuates resistance exercise-induced oxidative stress in rats. Evid Based Complementary Altern Med, 2019, 2019, 3528932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.C.; Vitek, L.; Nam, C.M. Algae consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2005. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2010, 56, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakmal, H.H.; et al. Anticancer and antioxidant effects of selected Sri Lankan marine algae. J. Natn. Sci. Foundation Sri Lanka, 2014, 42, 315–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.; Li, Y.H.; Shi, G.Y.; Tang, S.H.; Jiang, S.J.; Huang, C.W.; Liu, P.Y.; Hong, J.S.; Wu, H.L. Dextromethorphan reduces oxidative stress and inhibits atherosclerosis and neointima formation in mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 82, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Marco Bonesi, M.; Menichini, F.; De Luca, D.; Colicad Cand Menichinia, F. Evaluation of Citrus aurantifolia peel and leaves extracts for their chemical composition, antioxidant and anti-cholinesterase activities. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2021, 92, 2960–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Tsukui, T.; Sashima, T.; Hosokawa, M.; Miyashita, K. Seaweed carotenoid, fucoxanthin, as a multifunctional nutrient. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008, 17, 196–199. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, U.Z.; Hundley, N.J.; Romero, G.; Radi, R.; Freeman, B.A.; Tarpey, M.M.; Kelley, E.E. Febuxostat inhibition of endothelial-bound XO: Implications for targeting vascular ROS production. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máximo, P.; Ferreira, L.M.; Ferreira, P.; Lima, P.; Lourenço, A. Secondary Metabolites and Biological Activity of Invasive Macroalgae of Southern Europe. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Okubo, H.; Sasaki, S.; Arakawa, M. Seaweed consumption and prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: baseline data from the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, S.; Hashim, N.; Rahman, H.A. Seaweeds: a sustainable functional food for complementary and alternative therapy. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2012, 23, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.; Hashim, N.; Rahman, H.A. Seaweeds: a sustainable functional food for complementary and alternative therapy. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2012, 23, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated docking using a lamarckian genetic algorithm and empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukesh, B.; Rakesh, d.K. . Molecular Docking: A Review. IJRAP 2011, 2, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.P.; O’Connor, J.; Fitton, J.H.; et al. A combined phase I and II open-label study on the Immunomodulatory effects of seaweed extract nutrient complex. Biologics 2011, 5, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.P.; Mulder, A.M.; Baker, D.G.; Robinson, S.R.; Rolfe, M.I.; Brooks, L.; Fitton, J.H. Effects of fucoidan from Fucus vesiculosus in reducing symptoms of osteoarthritis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Biol. Targets Ther. 2016, 10, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan, S.; Mathaiyan, M. , Emerging novel anti HIV biomolecules from marine Algae: an overview. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 5, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namzar, F.; Mohamad, R.; Baharara, J.; Balanejad, Z.; Fargahi, F.; Rahman, H.S. Antioxidant, Antiproliferative, and Antiangiogenesis Effects of Polyphenol-Rich Seaweed (Sargassum muticum). Hindawi Publishing Corporation BioMed Research International 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, F.; Baharar, J.; Mahdi, A.A. Ntioxidant and anticancer activities of selected Persian Gulf algae. Indian J Clin Biochem 2014, 29, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanri, A.; Mizoue, T.; Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Noda, M.; Kato, M.; Kurotani, K.; Goto, A.; Oba, S.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S. Dietary patterns and suicide in Japanese adults: the Japan public health center-based prospective study, Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 203, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, K.M.; Mobin, M.; Abbas, Z.K. Variation in Photosynthetic Pigments, Antioxidant Enzymes and Osmolyte Accumulation in Seaweeds of Red Sea. Int J Plant Biol Res 2015, 3, 1028. [Google Scholar]

- Okimoto, N.; Futatsugi, N.; Fuji, H.; Suenaga, A.; Morimoto, G.; Yanai, R. ,... & Taiji, M. High-performance drug discovery: computational screening by combining docking and molecular dynamics simulations. Biophysical Journal 2010, 98, 460a. [Google Scholar]

- Padilha, E.C.; Serafim, R.B.; Sarmiento, D.Y.R.; Santos, C.F.; Santos, C.B.; Silva, C.H. New PPARα/γ/δ optimal activator rationally designed by computational methods. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2016, 27, 1636–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, J. Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid present in brown seaweeds and diatoms: metabolism and bioactivities relevant to human health. Marine Drugs 2011, 9, 1806–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.L.; Santos, G.B.; Franco, M.S.; Federico, L.B.; Silva, C.H.; Santos, C.B. Molecular modeling and statistical analysis in the design of derivatives of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2018, 36, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praiboon, J.; Palakas, S.; Noiraksa, T.; Miyashita, K. Seasonal variation in nutritional composition and anti-proliferative activity of brown seaweed, Sargassum oligocystum. J Applied Phycolohy 2019, 30, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajauria, G.; Foley, B.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Identification and characterization of phenolic antioxidant compounds from brown Irish seaweed Himanthalia elongata using LC-DAD–ESI-MS/MS, Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ramberg, J.E.; Nelson, E.D.; Sinnott, R.A. Immunomodulatory dietary polysaccharides: a systematic review of the literature. Nutrition Journal 2010, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Rosemary, T.; Arulkumar, A.; Paramasivam SMondragon PAMiranda, J.M. Biochemical, Micronutrient and Physicochemical Properties of the Dried Red Seaweeds Gracilaria edulis and Gracilaria corticata. Molecule 2019, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, L. Discovery and early uses of iodine. J. Chem. Educ. 2000, 77, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, G.; Rarung, K.L.; Wonggo, D.; Dotulong, V.; Damongilala, L.J.; Tallei, T.E. Cytotoxic activity of seaweeds from North Sulawesi marine waters against cervical cancer. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2021.

- Sanger, G.; Rarung, L.K.; Kaseger, B.E.; Assa, J.R.; Agustin, A.T. Phenolic content and antioxidant activities of five seaweeds from North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation 2019, 12, 2041–2050. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.B.R.; Ramos, R.S.; Sánchez Ortiz, B.L.; Silva, G.M.; Giuliatti, S.; Balderas-Lopez, J.L.; Navarrete, A.; Carvalho, J.C.T. Oil from the fruits of Pterodon emarginatus Vog.: A traditional anti-inflammatory. Study combining in vivo and in silico. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 222, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, D.; Gleitz, S.; Nguyen, H.H.; Kosinsky, R.L.; Sehmisch, S.; Hoffmann, D.B.; Wassmann, M.; Menger, B.; Komrakova, M. Effect of the lipoxygenase-inhibitors baicalein and zileuton on the vertebra in ovariectomized rats. Bone 2017, 101, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, L.; Prabhakar, B.; Pandita, N. Quantitative HPLC analysis of ascorbic acid and gallic acid in Phyllanthus emblica. J Anal Bioanal Techniques 2010, 1, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, D. Molecular Docking Studies of Human MCT8 Protein With Soy isoflavones in Allan-Herndon-Dudley Syndrome (AHDS). Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2018, 8, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challenges in delivery of therapeutic genomics and proteomics; Shash dan Misra, A., Ed.; Elsevier, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Systèmes, D.B. Discovery Studio Modeling Environment. Release. 2020. Available online: https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download.

- Silva, A.A.; Gonçalves, R.C. Reactive oxygen species and the respiratory tract diseases of large animals. Ciência Rural 2010, 40, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.C.; Poiani, J.G.C.; Ramos, R.S.; Costa, J.S.; Silva, C.H.T.P.; Brasil, D.S.B.; Santos, C.B.R. Ligandand structure- based virtual screening from 16-(N,N-diisobutylaminomethyl)-6α-hydroxyivouacapan7β,17β-lactone compound with potential anti-prostate cancer activity. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2018, 83, 6472. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, P.R.S.; Cirne-Santos, C.C.; de Souza Barros, C.; Teixeira, V.L.; Carneiro, L.A.D.; Amorim, L.S.C.; Ocampo, J.S.P.; Castello-Branco, L.R.R.; de Palmer Paixão, I.C.N. , Diterpene from marine brown alga Dictyota friabilis as a potential microbicide against HIV-1 in tissue explants, J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleria, H.A.; Masci, P.; Gobe, G.; Osborne, S. Current and potential uses of bioactive molecules from marine processing waste. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 1064–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teas, J.; Vena, S.; Cone, D.L.; Irhimeh, M. , The consumption of seaweed as a protective factor in the etiology of breast cancer: proof of principle. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles Fujishima, M.A.; Silva, N.S.R.; Ramos, R.S.; Batista Ferreira, E.F.; Santos, K.L.B.; Silva, C.H.T.P.; Silva, J.O.; Campos Rosa, J.M.; Santos, C.B.R. An Antioxidant potential, quantum-chemical and molecular docking study of the major chemical constituents present in the leaves of curatella americana linn. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, M.S. , Croft, A.K.; Hayes, M. A review of antihypertensive and antioxidant activities in macroalgae. Botanica Marina 2010, 53, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladilo, G.; Hasannali, A. Hydrogen Bonds and Life in the Universe. MDPI Life Journal. International Center for Theoretical Physics: Itali 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.N.; Tamai, Y.; et al. Seaweed intake and blood pressure levels in healthy pre-school Japanese children. Nutrition Journal 2011, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.K. , Zhou, C.; Liu, J.; Zeng, X. Purification, antitumor and antioxidant activities in vitro of polysaccharides from the brown seaweed Sargassum pallidum. Food Chemistry 2008, 111, 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Reddy, B.S.; Wong, C.Q.; Weisburger, J.H. Effect of dietary undegraded carrageenan on colon carcinogenesis in F344 rats treated with azoxymethane or methylnitrosourea. Cancer Research 1978, 38, 4427–4430. [Google Scholar]

- White, P.A.; Oliveira, R.C.; Oliveira, A.P.; Serafini, M.R.; Araújo, A.A.; Gelain, D.P.; Moreira, J.C.; Almeida, J.R.; Quintans, J.S.; Quintans-Junior, L.J.; et al. Antioxidant activity and mechanisms of action of natural compounds.

- Williams, P.A.; Cosme, J.; Ward, A.; Angove, H.C.; Vinkovic’, D.M.; Jhoti, H. Crystal structure of human cytochrome P450 2C9 with bound warfarin. Nature 2003, 424, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.C.; Chao, C.Y.; Lin, S.J.; Chen, J.W. Low-dose dextromethorphan, a NADPH oxidase inhibitor, reduces blood pressure and enhances vascular protection in experimental hypertension. PLoS ONE 2012, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.C.; Chao, C.Y.; Lin, S.J.; Chen, J.W. Low-dose dextromethorphan, a NADPH oxidase inhibitor, reduces blood pressure and enhances vascular protection in experimental hypertension. PLoS ONE 2012, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalkowsky, S.H.; Valvani, S.C. Solubilities and partitioning. 2. Relationships between aqueous solubilities, partition coefficients, and molecular surface areas of rigid aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1979, 24, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapo, E.S.; Kouakou, H.T.; kouakou kouakou, L.; Kouadio, J.Y.; Kouamé, P.; Mérillon, J.M. Phenolic profiles of pineapple fruits (Ananas comosus L. Merrill) Influence of the origin of suckers. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2011, 5, 1372–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.; Mullarky, E.; Lu, C.; Bosch, K.N.; Kavalier, A.; Rivera, K.; Roper, J.; Chio, I.I.; Giannopoulou, E.G.; Rago, C.; et al. Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science 2015, 350, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Nicholas, A.; Robinson Robyn, D.; Warner Colin, J.; Barrow Frank, R.; Dunshea, I.; Hafiz, A.R.; Suleria, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Characterization of Seaweed Phenolics and Their Antioxidant Potential. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Juice | TPC (µg GAE/g) |

Fiber (%) | Vitamine C (µg/mL) |

pH value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 32,1788±0,509 | 0,80±0,04 | 2,8923±0,076 | 4.47±0,379 |

| A2 | 31,7723±0,141 | 0,84±0,01 | 2,7953±0,049 | 4.57±0,115 |

| A3 | 31.8646±0,616 | 0.94±0,03 | 2.8215±0,048 | 4.5±0,172 |

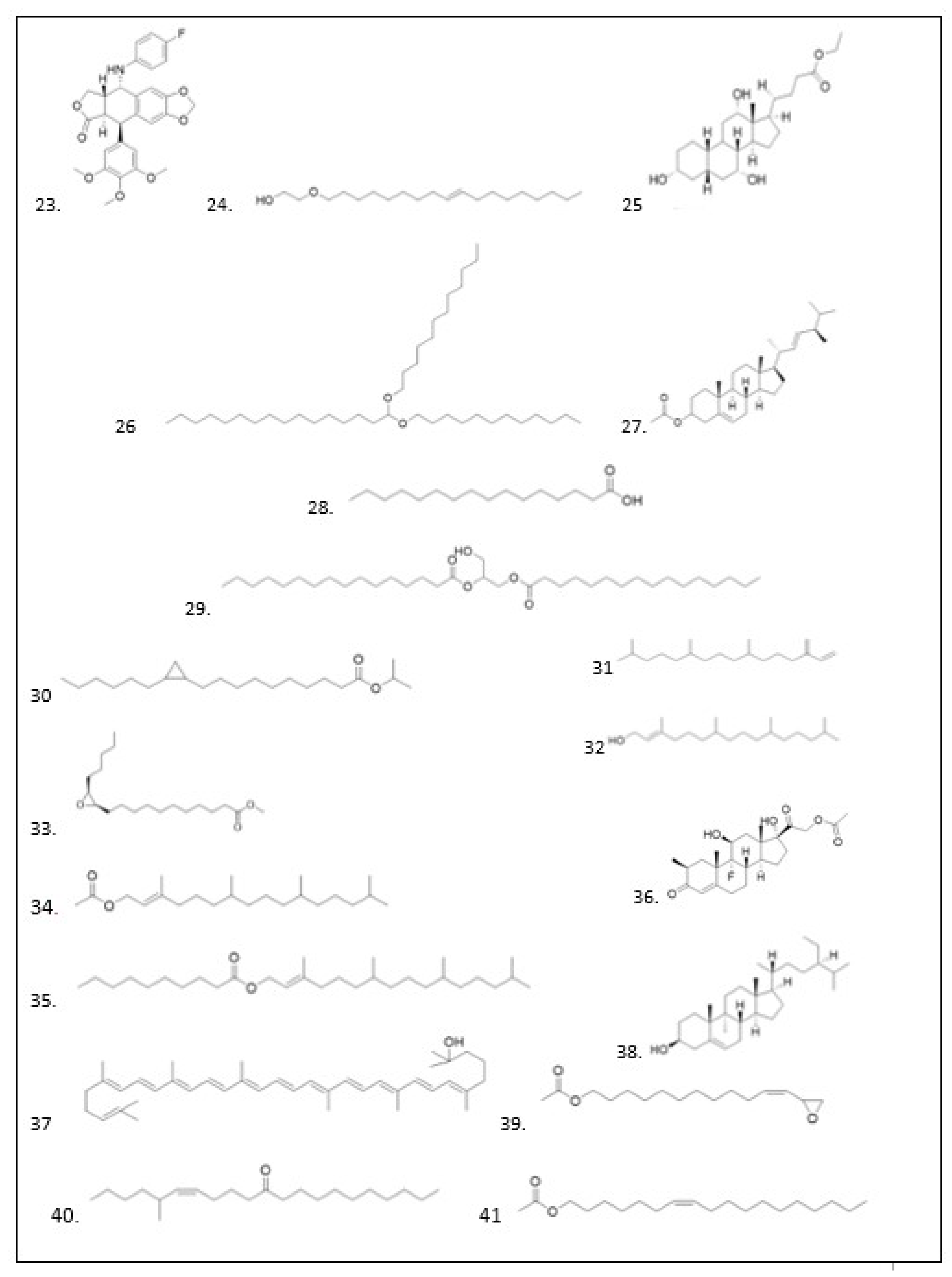

| No | Ligan | Molecule formula | RT | Persen area |

PubChem (CID) | Compound Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12-Octadecenal | C 18H34O | 17.71 | 1.31 | 5367671 | Aldehide |

| 2 | 13-Octadecenal | C 18H34O | 17.71 | 1.31 | 5367670 | Aldehide |

| 3 | 1H-Cyclopropa [3,4]benz [1,2-e]azulene-5,7b,9,9a-tetrol, 1a,1b,4,4a,5,7a,8,9-octahydro-1,1,6,8-tetramethyl-3-[(triphenylmethoxy)methyl]-, 5,9,9a-triacetate | C28H38O9 | 19.02 | 1.09 | 596973 | Ester |

| 4 | 1-Heptatriacotanol | C37H76O | 21.22 | 0.63 | 537071 | Alcohol |

| 5 | 2-Methyl-1-hexadecanol | C17H36O | 15.42 | 0.49 | 17218 | Alcohol |

| 6 | 2-[4-Methyl-6-(2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-enyl)hexa-1,3,5-trienyl]cyclohex-1-en-1-carboxaldehyde | C23H32O | 16.99 | 0.96 | 5363101 | Aldehide |

| 7 | 2-Methyl-E,E-3,13-octadecadien-1-ol | C19H36O | 16.72 | 1.65 | 5364413 | Alcohol |

| 8 | 6,10,14-Trimethylpentadecan-2-one | C18H36O | 16.99 | 4.48 | 10408 | Keton |

| 9 | 3,7,11,15-Tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol | C20H40O | 17.36 | 3.25 | 5366244 | Alcohol |

| 10 | 4H-Cyclopropa [5’,6’]benz [1’,2’7,8]azuleno [5,6-b]oxiren-4-one, 8,8a-bis(acetyloxy)-2a-[(acetyloxy)methyl]-1,1a,1b,1c,2a,3,3a,6a,6b,7,8,8a-dodecahydro-3,3a,6b-trihydroxy-1,1,5,7-tetramethyl- | C26H34O11 | 25,98 | 2.76 | 538186 | Keton |

| 11 | 5H-Cyclopropa [3,4]benz [1,2-e]azulen-5-one, 4,9,9a-tris(acetyloxy)-3-[(acetyloxy)methyl]-1,1a,1b,4,4a,7a,7b,8,9,9a-decahydro-4a,7b-dihydroxy-1,1,6,8-tetramethyl- | C28H36O11 | 25,98 | 2.76 | 538181 | Aldehide |

| 12 | 17-Chloro-7-heptadecene | C17H33Cl | 19.61 | 7.09 | 5364489 | Alkena |

| 13 | 7-Heptadecene, 1-chloro- | C17H33Cl | 19.61 | 7.09 | 5364485 | Alkena |

| 14 | 7-Methyl-Z-tetradecen-1-ol acetate | C17H32O2 | 16,72 | 1.65 | 5363222 | Ester |

| 15 | 9,10-Secocholesta-5,7,10(19)-triene-3beta,25-diol | C27H44O2 | 28.68 | 7.48 | 6506392 | Alcohol |

| 16 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, 2-phenyl-1,3-dioxan-5-yl ester | C28H40O4 | 16.43 | 0.96 | 5367498 | Ester |

| 17 | 9-Desoxo-9-x-acetoxy-3,8,12-tri-O-acetylingol | C28H40O10 | 24.74 | 0.27 | 537583 | Alcohol |

| 18 | 4-Methylcholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol | C28H46O | 22.90 | 1.69 | 44150703 | Alcohol |

| 19 | cis-10-Nonadecenoic acid | C19H36O2 | 18.46 | 1.39 | 5312513 | Carboxilic acid |

| 20 | Cyclopropanebutanoic acid, 2-[[2-[[2-[(2-pentylcyclopropyl)methyl]cyclopropyl]methyl]cyclopropyl]methyl]-, methyl ester | C25H42O2 | 17.81 | 1.18 | 554084 | Ester |

| 21 | Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2oktil metil ester | C15H28O2 | 16.22 | 0.51 | 11447830 | Carboxilic acid |

| 22 | Docosanoic acid, 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester | C69H134O6 | 22.54 | 0.81 | 62726 | Ester |

| 23 | (22E)-Ergosta-5,22-dien-3-ol acetate | C30H48O2 | 28,99 | 3.62 | 5352877 | Ester |

| 24 | Ethanol, 2-(9-octadecenyloxy)-, (E)- | C20H40O2 | 17.17 | 1.99 | 5367702 | Ester |

| 25 | Ethyl iso-allocholate | C26H44O5 | 16.22 | 0.51 | 6452096 | Ester |

| 26 | Furo(3’,4’:6,7)naphtho(2,3-d)-1,3-dioxol-6(5aH)-one, 9-((4-fluorophenyl)amino)-5,8,8a,9-tetrahydro-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-, (5R,5aR,8aS,9S)- | C28H26FNO7 | 19.25 | 0.44 | 468876 | Alkaloid |

| 27 | 1,1-Bis(dodecyloxy)hexadecane | C40H82O2 | 19.61 | 7.09 | 41920 | Alkena |

| 28 | Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 18,23 | 6.35 | 985 | Carboxilic acid |

| 29 | Hexadecanoic acid, 1-(hydroxymethyl)-1,2-ethanediyl ester | C35H68O5 | 20.84 | 3.04 | 99931 | Ester |

| 30 | i-Propyl 11,12-methylene-octadecanoate | C22H42O2 | 18.77 | 1.02 | 91692516 | Ester |

| 31 | Neophytadiene | C20H38 | 16,91 | 3.19 | 10446 | Alkena |

| 32 | Oxiraneundecanoic acid,3-pentyl-, methyl ester, cis- | C13H24O3 | 17.81 | 1.18 | 86131368 | Carboxilic aid |

| 33 | Phytol | C20H40O | 19.89 | 10.81 | 5280435 | Alcohol |

| 34 | Phytol, acetate | C22H42O2 | 20.53 | 6.04 | 6428538 | Ester |

| 35 | Phytyl decanoate | C30H58O2 | 20.53 | 6.04 | 91711717 | Ester |

| 36 | Pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione, 21-(acetyloxy)-9-fluoro-11,17-dihydroxy-2-methyl-, (2beta,11beta)- | C24H33FO6 | 19.02 | 1.09 | 31719 | Steroid |

| 37 | Rhodopin | C40H58O | 29,32 | 0.45 | 5365880 | Terpenoid |

| 38 | ß-Sitosterol | C29H50O | 22.01 | 12,44 | 175268335 | Steroid |

| 39 | Z-(13,14-Epoxy)tetradec-11-en-1-ol acetate | C16H28O3 | 19.89 | 10.81 | 5363633 | Ester |

| 40 | Z-5-Methyl-6-heneicosen-11-one | C22H42O | 17.71 | 1.31 | 5363254 | Keton |

| 41 | Z-7-Octadecen-1-ol acetate | C20H38O2 | 16.99 | 4.48 | 5363553 | Ester |

| No | Ligan | Berat Molekul <500 | H-Donor <5 | H-Akseptor <10 | Log P <5 | Refraksi Molar 40-130 | Penyimpangan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12-Octadecenal | 266.000000 | 0 | 1 | 6.222801 | 85.515968 | 1 |

| 2 | 13-Octadecenal | 266.000000 | 0 | 1 | 6.222801 | 85.515968 | 1 |

| 3 | 1H-Cyclopropa [3,4]benz [1,2-e]azulene-5,7b,9,9a-tetrol, 1a,1b,4,4a,5,7a,8,9-octahydro-1,1,6,8-tetramethyl-3-[(triphenylmethoxy)methyl]-, 5,9,9a-triacetate | 312.000000 | 5 | 6 | -0.053101 | 77.145782 | 1 |

| 4 | 1-Heptatriacotanol | 312.000000 | 5 | 6 | -0.053101 | 77.145782 | 1 |

| 5 | 2-Methyl-1-hexadecanol | 256.000000 | 1 | 1 | 5.706000 | 81.944763 | 1 |

| 6 | 2-[4-Methyl-6-(2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-enyl)hexa-1,3,5-trienyl]cyclohex-1-en-1-carboxaldehyde | 81.944763 | 0 | 1 | 6.641202 | 103.926971 | 1 |

| 7 | 2-Methyl-E,E-3,13-octadecadien-1-ol | 280.000000 | 1 | 1 | 6.038201 | 90.990761 | 1 |

| 8 | 6,10,14-Trimethylpentadecan-2-one | 268.000000 | 0 | 1 | 6.014501 | 85.399971 | 1 |

| 9 | 3,7,11,15-Tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol | 296.000000 | 1 | 1 | 6.364101 | 95.561760 | 1 |

| 10 | 4H-Cyclopropa [5’,6’]benz [1’,2’7,8]azuleno [5,6-b]oxiren-4-one, 8,8a-bis(acetyloxy)-2a-[(acetyloxy)methyl]-1,1a,1b,1c,2a,3,3a,6a,6b,7,8,8a-dodecahydro-3,3a,6b-trihydroxy-1,1,5,7-tetramethyl- | 522.000000 | 0 | 11 | 4.684239 | 129.402466 | 2 |

| 11 | 5H-Cyclopropa [3,4]benz [1,2-e]azulen-5-one, 4,9,9a-tris(acetyloxy)-3-[(acetyloxy)methyl]-1,1a,1b,4,4a,7a,7b,8,9,9a-decahydro-4a,7b-dihydroxy-1,1,6,8-tetramethyl- | 548.000000 | 0 | 11 | 5.092820 | 138.002487 | 2 |

| 12 | 17-Chloro-7-heptadecene | 272.500000 | 0 | 0 | 6.872602 | 85.554970 | 1 |

| 13 | 7-Heptadecene, 1-chloro- | 272.500000 | 0 | 0 | 6.872602 | 85.554970 | 1 |

| 14 | 7-Methyl-Z-tetradecen-1-ol acetate | 268.000000 | 0 | 2 | 5.272600 | 82.163971 | 1 |

| 15 | 9,10-Secocholesta-5,7,10(19)-triene-3beta,25-diol | 400.000000 | 2 | 2 | 6.733902 | 122.648552 | 1 |

| 16 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, 2-phenyl-1,3-dioxan-5-yl ester | 440.000000 | 0 | 4 | 6.540953 | 135.386978 | 1 |

| 17 | 9-Desoxo-9-x-acetoxy-3,8,12-tri-O-acetylingol | 536.000000 | 0 | 10 | 5.651121 | 141.818985 | 2 |

| 18 | 4-Methylcholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol | 398.000000 | 1 | 1 | 7.698903 | 123.645737 | 1 |

| 19 | cis-10-Nonadecenoic acid | 296.000000 | 1 | 2 | 5.039920 | 102.327286 | 0 |

| 20 | Cyclopropanebutanoic acid, 2-[[2-[[2-[(2-pentylcyclopropyl)methyl]cyclopropyl]methyl]cyclopropyl]methyl]-, methyl ester | 374.000000 | 0 | 2 | 6.222682 | 127.046967 | 1 |

| 21 | Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2oktil metil ester | 240.000000 | 1 | 2 | 4.772099 | 71.146782 | 0 |

| 22 | Docosanoic acid, 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester | 312.000000 | 5 | 6 | -0.053101 | 77.145782 | 0 |

| 23 | (22E)-Ergosta-5,22-dien-3-yl acetate | 440.000000 | 0 | 2 | 7.507115 | 150.931992 | 1 |

| 24 | Ethanol, 2-(9-octadecenyloxy)-, (E)- | 312.000000 | 1 | 2 | 5.749202 | 110.685280 | 1 |

| 25 | Ethyl iso-allocholate | 436.000000 | 3 | 5 | 3.927198 | 119.034340 | 0 |

| 26 | Furo(3’,4’:6,7)naphtho(2,3-d)-1,3-dioxol-6(5aH)-one, 9-((4-fluorophenyl)amino)-5,8,8a,9-tetrahydro-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-, (5R,5aR,8aS,9S)- | 507.000000 | 1 | 8 | 4.435399 | 130.275681 | 1 |

| 27 | 1,1-Bis(dodecyloxy)hexadecane | 312.000000 | 5 | 6 | -0.053101 | 77.145782 | 1 |

| 28 | Hexadecanoic acid | 312.000000 | 5 | 6 | -0.053101 | 77.145782 | 1 |

| 29 | Hexadecanoic acid, 1-(hydroxymethyl)-1,2-ethanediyl ester | 256.000000 | 1 | 2 | 5.552299 | 77.947777 | 1 |

| 30 | i-Propyl 11,12-methylene-octadecanoate | 338.000000 | 0 | 2 | 6.129292 | 118.590973 | 1 |

| 31 | Neophytadiene | 278.000000 | 0 | 0 | 7.167703 | 94.055969 | 1 |

| 32 | Oxiraneundecanoic acid, 3-pentyl-, methyl ester, cis- | 228.000000 | 1 | 3 | 3.370800 | 63.545784 | 0 |

| 33 | Phytol | 296.000000 | 1 | 1 | 6.364101 | 95.561760 | 0 |

| 34 | Phytol, acetate | 338.000000 | 0 | 2 | 6.934901 | 105.108963 | 1 |

| 35 | Phytyl decanoate | 450.000000 | 0 | 2 | 8.799607 | 162.773972 | 1 |

| 36 | Pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione, 21-(acetyloxy)-9-fluoro-11,17-dihydroxy-2-methyl-, (2beta,11beta)- | 436.000000 | 2 | 6 | 2.690500 | 109.585564 | 0 |

| 37 | Rhodopin | 554.000000 | 1 | 1 | 9.998867 | 189.588913 | 2 |

| 38 | ß-Sitosterol | 368.000000 | 0 | 1 | 1.510640 | 93.379990 | 0 |

| 39 | Z-(13,14-Epoxy)tetradec-11-en-1-ol acetate | 565.000000 | 2 | 10 | 1.031598 | 152.134506 | 1 |

| 40 | Z-5-Methyl-6-heneicosen-11-one | 322.000000 | 0 | 1 | 6.447083 | 118.461472 | 1 |

| 41 | Z-7-Octadecen-1-ol acetate | 310.000000 | 0 | 2 | 5.705202 | 108.268982 | 1 |

| No | Molecular docking | Resolution | ∆G (Kkal/mol) |

RMSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cytochrome P450 (CP40) X S walfarin |

2.55 Å |

-10.4260 |

0.6311 Å |

| 2 | Lipoxygenase (LO) X Protocatecuic acid |

2.10 Å |

-6.6490 | 1.9756 Å |

| 3 | Myeloperoxidase (MP) X N-acethyl-D-glucosamine |

1.85 Å |

-4.2060 |

0.7344 Å |

| 4 | NADPH Oxidase (NO) X Adenocine-5-diphosphat |

1.80 Å |

:-8.8380 | 0.9495 Å |

| 5 | Xanthine oxidase (XO) X Hypoxanthin. |

1.80 Å |

- 5.9700 | 0.1940 Å |

| No. | Compound | HIA | BBB | Plasma protein Binding | CP450 | p-Gp | Log Kp | BiA Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | 100.000000 | 17.5431 | 100.000000 | inhibitor | Inhibitor | -1,25 | 0,55 |

| 2 | Oxiraneundecanoic acid, 3-pentyl-, methyl ester, cis- | 98.555395 | 6.62728 | 100.000000 | Inhibitor | No | -3,62 | 0,55 |

| 3 | cis-10-Nonadecenoic acid | 98.386939 | 9.69018 | 100.000000 | Inhibitor | Inhibitor | 0,525741 | 0,85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).