1. Introduction

How a child grasps and manipulates an object depends on their ability to control the forces they use to handle an object. (R. S. Johansson & Cole, 1992; R. Johansson & Westling, 1988). For example, poor control of forces may affect the ability to grade forces while writing, leading to poor handwriting. Similarly, force control affects grasping and holding utensils, leading to accidental spills or the inability to complete tasks. Understanding the forces imparted onto an object during manipulation can shed light on the quality of daily manual behaviors. (Forssberg, Eliasson, et al., 1991; Forssberg et al., 1992; Gordon, 2016; Gordon et al., 2006; Gordon & Duff, 1999a; Rose & Parikh, 2025).

Skillful object manipulation depends on predictive (anticipatory) mechanisms formed through experiences as well as reactive mechanisms based on sensory information. (Gordon et al., 1993; R. S. Johansson & Cole, 1992a; Parikh et al., 2020a; Rose & Parikh, 2025). Sensory and motor function have been examined during development in terms of their relationships to the control of forces for a grip and lift task (Gordon & Duff, 1999). For instance, sensory inputs provide precise information about contact with an object and guide the control of forces while handling an object (Forssberg, Kinoshita, et al., 1991; R. S. Johansson & Cole, 1992; R. S. Johansson & Flanagan, 2009). Distal muscle strength is also important for the application and control of forces (Bumin & Kayihan, 2001; Damiano et al., 2001; Engsberg et al., 2006; Fedrizzi et al., 2003; Moon et al., 2017; Tofani et al., 2020). Typical tests of hand function used in clinics do not examine the control of forces, thus do not objectively assess the sensorimotor behavior, and may be less sensitive to functionally relevant changes in hand function following an intervention (Olsen & Knudson, 2001; Sears & Chung, 2010; Wolff, 2023).

Using knowledge from previous laboratory-based studies of force control (Cole et al., 2010; Darling et al., 2006; Gash et al., 1999; Parikh & Cole, 2012), we have developed an objective measure of the quality of hand function in children, the Bead Maze hand function (BMHF) test (Rose et al., 2024). The BMHF test quantifies not only how quickly a task is accomplished but also how well the individual performs the activity by integrating measures of time and force control (Rose et al., 2024). During the test, children use their digits to slide a small bead over smooth wires of different shapes that require small changes in movement direction, while force sensors measure the forces imparted onto the wire. In a previous study, as the wires increased in complexity, participants applied more force as opposed to taking more time when maneuvering the bead (Rose et al., 2024), indicating that force is a more relevant measure of skill. We suggest that both sensory function and distal strength contribute to the ability to control forces during the BMHF test in children.

The main objectives of this study were to examine associations between performance (total force output) on the BMHF test and 1) performance on a laboratory-based assessment of force scaling using a laboratory gold standard dexterous manipulation task, and 2) general sensory and motor parameters important for fine motor skills. In the dexterous manipulation task, participants learn to scale the (rotational) forces required to lift an object with more mass on one side than the other. We expected that greater error in generating anticipatory forces on the dexterous manipulation task (torque error, TE) would predict higher total force on the BMHF test. We also expected that increases in hand size, grip strength, and tactile ability associated with increasing age would predict improved precision in performing the BMHF test, i.e., lower total force.

2. Materials and Methods

Thirty-nine typically developing children and adolescents provided assent, and parents provided written informed consent to participate in this study. Participants ranged in age from 5-10 years old (n=28) and 15-17 years (n=11). The study required each participant to participate in one session lasting approximately 2 hours. Participants were right-hand dominant with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, no upper limb injury, and no musculoskeletal or neuromuscular disorders as reported by a parent. The study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Houston.

Bead Maze Hand Function Test

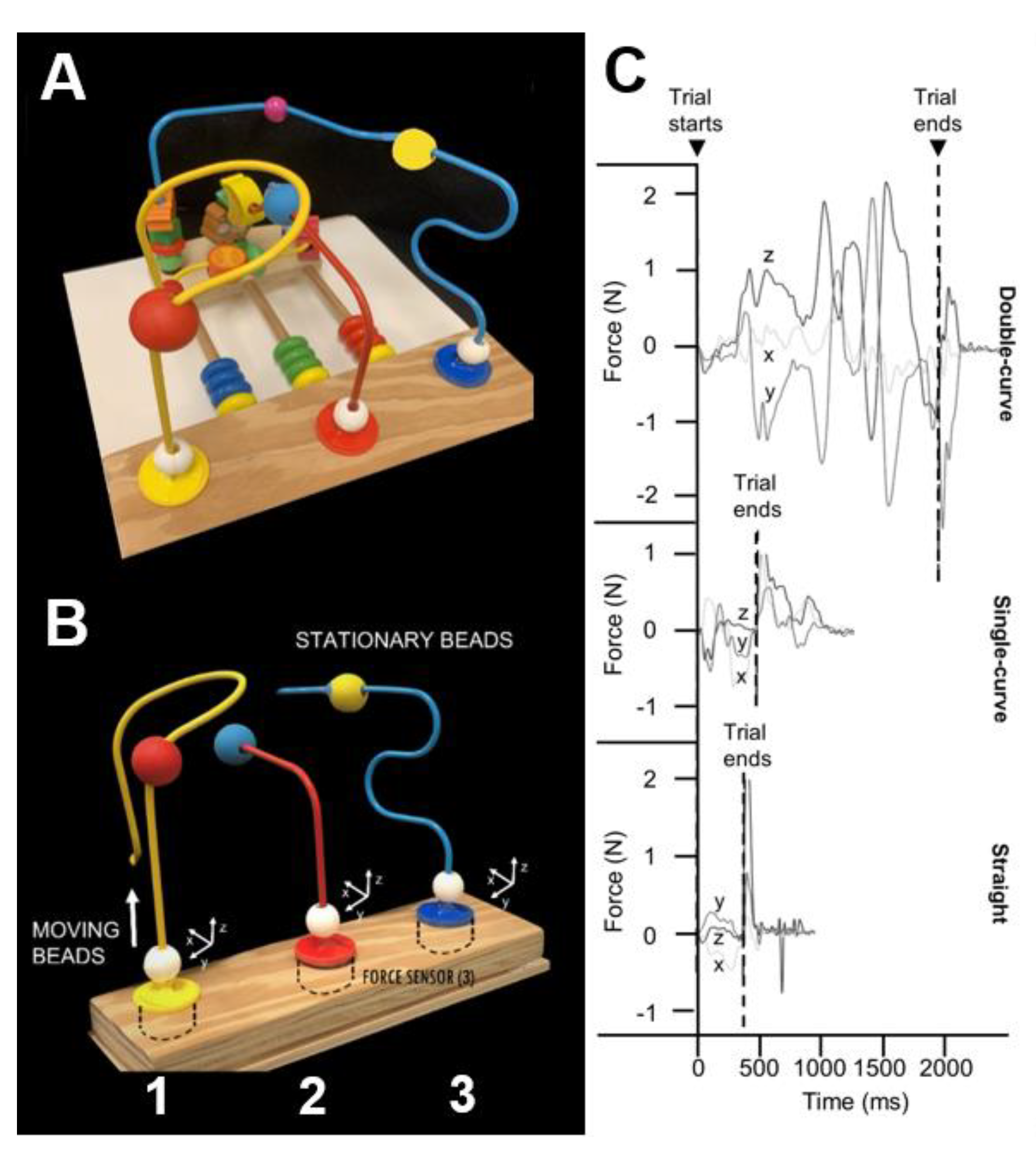

The BMHF test apparatus (

Figure 1A), as previously described (Rose et al., 2024), includes three triaxial force transducers (Nano 25, ATI, NC; 1000Hz) mounted on a base beneath a top plate holding straight and curved metal wires. This setup captures forces along all axes (x, y, z;

Figure 1B) as participants move beads along the wires. Each wire is rigidly connected to a sensor to allow continuous force recording during movement. Three wire shapes—straight, single-curve, and double-curve—represent increasing levels of difficulty. The moving beads (MVBs) are 18mm in diameter with a 6.5mm lumen and have textured surfaces to reduce slippage. Each wire also includes a stationary bead (STB) affixed to the wire at a fixed distance from the sensor. In the present study, we tested only the double curve wire because our previous work noted greater sensitivity of the total force to the precision demands of the complex shape of the double curve wire (Rose et al., 2024).

Participants sat with their hands resting on their laps, with the BMHF device placed 10 cm from the table edge. Verbal instructions were to grasp the MVB, lift it, and draw it over the wire until it came in contact with the STB. Once the MVB contacted the STB, participants were asked to release their grasp and return their hand to their lap. After a demonstration and one practice trial, participants used their dominant hand to perform five trials at a self-selected, comfortable speed. No specific instructions were given on grip, contact with the wire, or task execution (Rose et al., 2024).

Figure 1. A. Bead Maze Hand function test apparatus, B. Diagram showing where sensors are placed, moving and stationary beads for each wire shape (straight, single-curve, and double-curve). The wooden base measures 26x10cm and wires are 9cm apart. Force sensor top plates (3.4cm diameter) attach each wire. C. Representative force tracing outputs (horizontal—x,y, and vertical—z) shown in Newtons (N) for each wire shape. Trial starts and ends are identified according to characteristic changes in the force tracings. Reproduced from Rose et al 2024. The Bead Maze Hand Function Test for Children. Am J Occup Ther. 2024 Jul 1;78(4):7804205010. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2024.050584. PMID: 38900916; PMCID: PMC11220783.

Laboratory-Based Dexterous Object Manipulation Task.

Digit forces and torques were recorded using a custom inverted T shaped pediatric device (421.9 g) instrumented with two 6 axis force/torque sensors (Nano 25, ATI Industrial Automation; 1000 Hz), featuring two 10 cm, 320-grit sandpaper grasping surfaces and a 5 cm total width (Rose and Parikh 2025). The base included hidden compartments (left, center, right) for inserting a 200 g external mass, which generated ±122 N·mm frontal-plane torque depending on its position. Object roll (tilt) was tracked via an electromagnetic sensor (Polhemus FASTRAK; 0.05° resolution, 120 Hz) placed on top. Force data were sampled at 1 kHz via an analog-to-digital converter (PCI 6220 DAQ, National Instruments).

Participants were instructed to lift the device ~10 cm from the table, pause for ~1 second, then place it back down. They aimed to lift it as vertically as possible to prevent frontal-plane rotation caused by the asymmetrical mass. Before each block of 10 trials, participants were informed that a change was made in the mass location, watched a demonstration, and completed two practice attempts with a centered mass. Between blocks, the external mass was repositioned out of view. Participants had to anticipate—not react to—the torque through successive lifts. Visual feedback from the object’s roll indicated task performance. Over repeated attempts, participants learned to predict and apply the compensatory torque before lifting.

Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted during one session in a well-illuminated and quiet room. Participants began with a hand preference test, and their hand span and length were measured (Thomas et al., 2022). For strength measures, participants were instructed to pinch a standard pinch gauge (accuracy ±1%, B&L Eng, CA) as hard as possible using a precision pinch grip and key grip. We used the highest score of two attempts for our analysis. For stereognosis, three familiar objects (key, spoon, pin) and six similar matched objects (e.g., button/coin; paper clip/safety pin; pen/pencil) were placed into the right hand from behind a screen, not visible to the participant. Participants verbally identified or matched each object to a visual display of the same objects, with scores ranging from 0 to 9 (Sakzewski et al., 2010). Participants then performed the BMHF test and the dexterous object manipulation task (Fu et al., 2010; Gutterman et al., 2021; Rose & Parikh, 2025).

Data Analysis

Total Force on the BMHF Test.

The BMHF force data were collected via a custom LabVIEW program (NI, TX) and processed using a MATLAB script (MathWorks, MA) with a 30 Hz low-pass, 5th order Butterworth filter (Rose et al 2024). Trial start was defined as the moment x, y, or z force exceeded baseline (mean ± 2SD) for at least 10 ms. Trial end was marked by a stereotypical y-force drop to -0.2 N following MVB-STB contact and prior to grasp release (

Figure 1C). Start and end times were algorithmically identified and visually confirmed. The trial duration was computed as the difference between the trial end time and the trial start time (in sec). The absolute value of the force signals from contact to end was summed to the total force for each trial. The mean of the last 5 trials was used for analysis (Rose et al 2024). The average of the final five trials was used for analysis.

Torque Error (TE) on the Dexterous Manipulation Task.

The force data were run through a 5th-order low-pass Butterworth filter (Fu et al., 2010; Parikh et al., 2020b; Rose & Parikh, 2025). Position data were resampled at the same rate as the force data (MATLAB; MathWorks). Object lift onset was defined as the time at which the vertical position of the grip device crosses and remains above a threshold (mean +2SD of the baseline) for 200ms. The torque exerted on the object was computed at the time of lift onset to quantify anticipatory control (Forssberg, Eliasson, et al., 1991; Forssberg et al., 1992). This is the time before subjects perceive and react to the external torque. The torque error (TE) is the absolute difference between the amount of applied compensatory torque and the target compensatory torque that is required to lift the object vertically. The TE during the last 5 trials of both the right and the left weighted conditions was averaged for each subject.

Statistical Analysis

A hierarchical regression was conducted to estimate a model that best predicts total force (α = 0.05). Model 1 was planned to test whether decreases in TE predict decreases in total force on the BMHF test. Model 2 was planned to test whether clinical measures (stereognosis, hand strength, or size) would improve the model fit. Clinical measures were chosen for the model comparison based on their contribution to precision force control according to the literature and on their suitability based on the assumptions of multiple regression. We performed bootstrapping to account for deviations from a normal distribution and inspected all relevant outputs for multicollinearity and normality of residuals. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 28.0 (IBM, USA)..

3. Results

Relationships Between Total Force on the BMHF Test and Clinical Measures

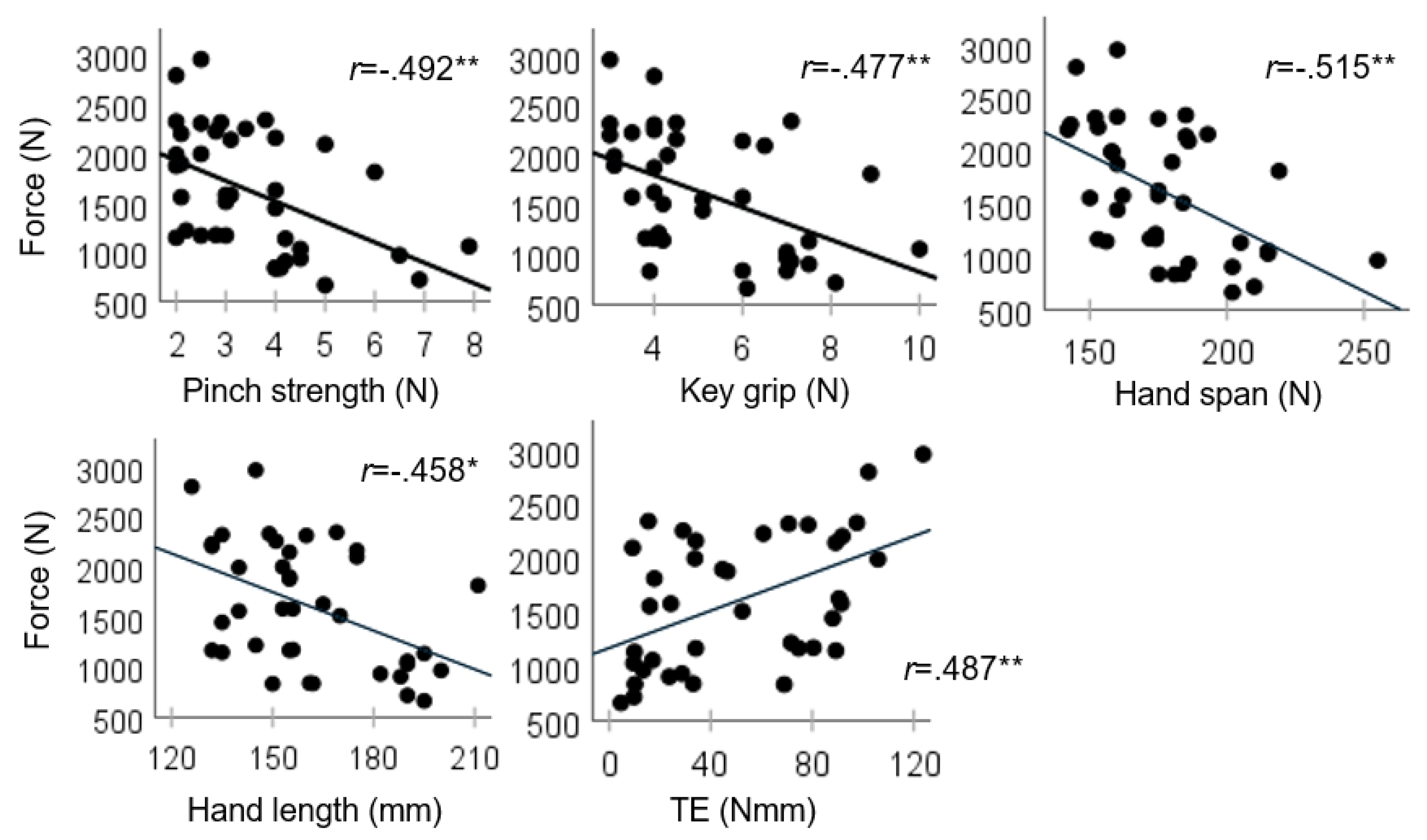

We found that the total force on the BMHF test was correlated with the grip strength and anthropometric variables (

Figure 2).

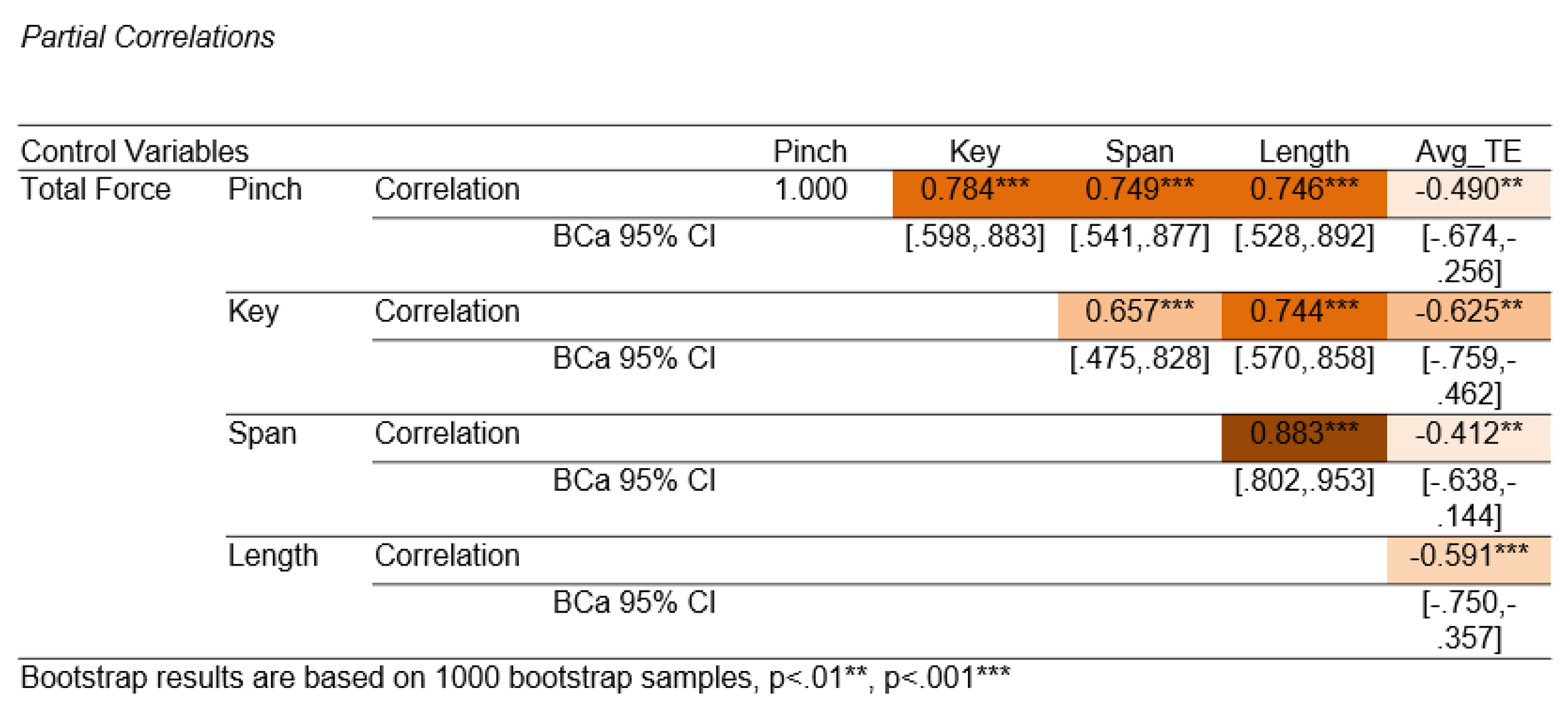

Given the known increases in strength and size during typical development, it was not surprising to find that these variables shared variance in total force (partial correlations,

Table 1). Based on their shared variance, any one of these measures could be a suitable predictor of BMHF total force. Pinch strength was chosen for the regression model because it (and hand span) shared the least variance with TE (

Table 1).

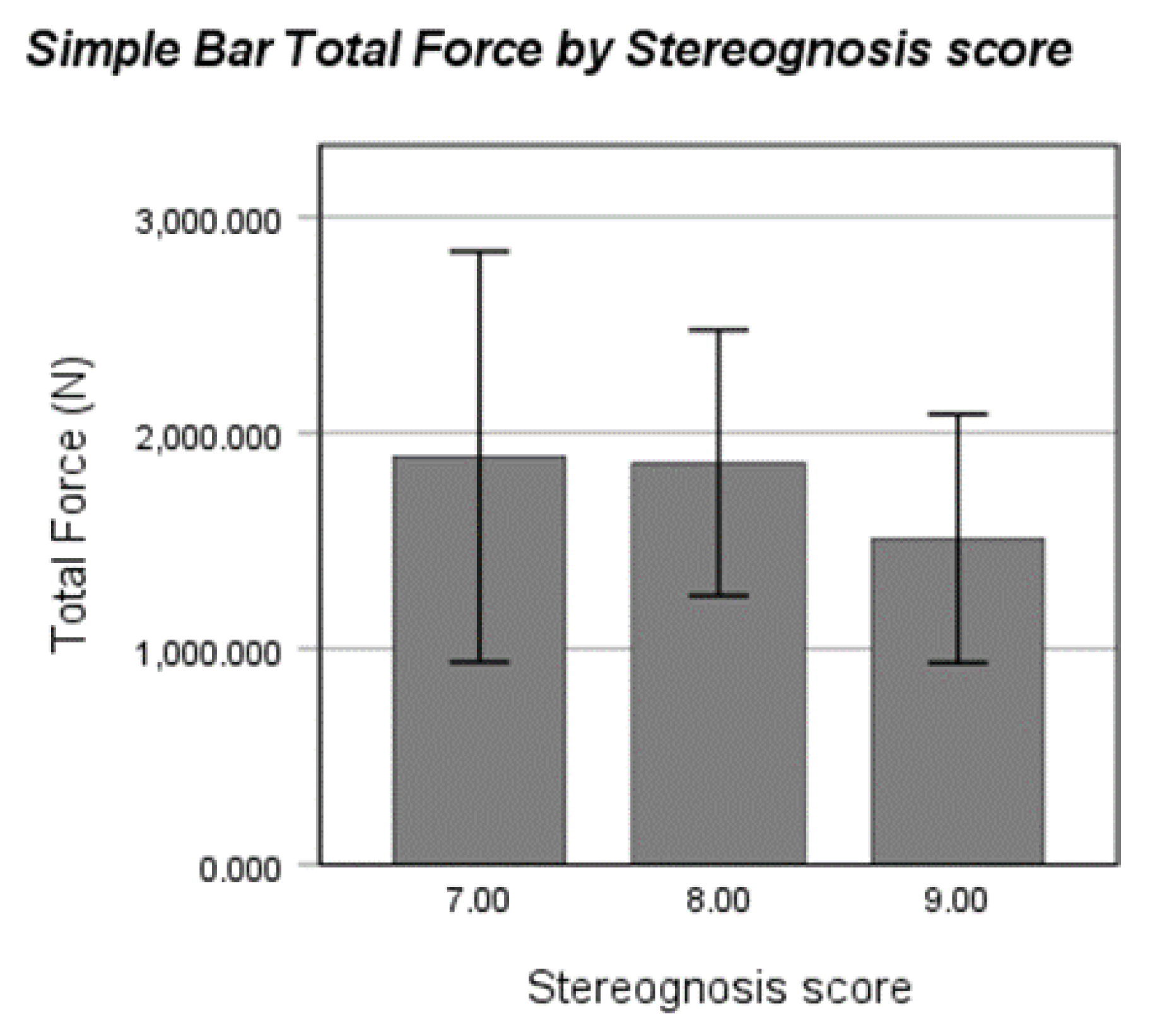

For stereognosis, we performed a bootstrap point-biserial correlation between stereognosis score (Y/N perfect score) and total force. Despite the limitations of sample size at the lower scores, the correlation was near-significant (rpb=.265, p=.052, 95% BCa CI [-.097,.542]). There were only 3 participants who scored a 7/9 (ages 5.5, 6.12, and 7.7yrs), and 8 who scored an 8/9 (ages 5.08- 9.6yrs). While there was a trend (

Figure 3) indicating that typically developing children with scores less than 9/9 on the stereognosis test exerted more total force on the wire, there were not enough data points to draw conclusions.

Predictors of Total Force on the BMHF Test

Results from Model 1 (TE only) indicated that TE was a significant predictor of total force (F1,38=11.506, p=.002). As TE increases (Nmm), total force on the double curve wire increases 8.613N (at least 4.175N, 95% BCa lower bound). The R2 for Model 1 was .237, and the adjusted R2 .217 (2% less). Adding pinch strength into Model 2 improved the R2 (.297) and the adjusted R2 (.258). Model 2 was also significant (F2,36=7.615, p=.002), and both TE and pinch strength were significant predictors (

Table 2). The regression equation for Model 2 (R2 = .297) is presented below, where total force on the BMHF test double-curve wire is predicted by TE (Nmm) and pinch strength (N). About 70% of the variance in total force is still unaccounted for by this model.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the relationship between force-based output on an activity based assessment of precision force control—the BMHF test- and measures of strength, hand size, stereognosis, and force coordination (TE) in typically developing children and adolescents. We found that better performance on the BMHF test can be predicted by the development of anticipatory coordination of digit forces. We also found that factors of hand size and strength known to improve with age in typically developing children were associated with improved BMHF performance, and that pinch strength improved our ability to predict total force on the double curve wire. We discuss these findings in the context of the literature on the development of precision force control and their relevance to how the BMHF test might be used to connect developmental changes in body structures/functions with improvement in fine manual performance.

Linking Lab-Based Assessments to the BMHF Test

A key finding of this study is that force control during an activity-based assessment of hand function can be predicted by sensorimotor performance on a fine motor object manipulation task in a laboratory setting. In the grasping literature, fine motor skill is quantified in terms of anticipatory control of grasp parameters, e.g., accurate scaling of grasp parameters to object properties before grip and lift of an object. The anticipatory control indicates the brain’s ability to use sensorimotor memories from prior experience with the same or similar objects to plan the task for dexterous manipulation (Gordon et al., 1993; R. S. Johansson & Cole, 1988; Parikh et al., 2020). Torque error was calculated from the laboratory-based object manipulation task that required participants to scale their torque based on an object’s presumed center of mass before lift-off. The task goal was to achieve lifting of the object without any tilt. Smaller or no deviation from the target torque (i.e., torque error or TE ~0Nˑmm) indicates higher accuracy in the anticipatory control of grasp parameters for torque application. Larger TE would prompt correction based on the sensory information (Johansson & Cole, 1992; Johansson & Flanagan, 2009; Parikh et al., 2020). The BMHF test, on the other hand, requires a combination of anticipatory and reactive strategies for the control of grasp parameters. As the child grasps and moves the bead along the wire, they encounter several curves that require anticipatory tilting and rotating of the bead with their digits to ensure smooth movement around it. Anticipatory tilting of the bead is crucial; without it, the bead rubs against the curves in the wire, increasing force on the wire, which can limit its progression along the path. Our findings suggest that participants who were better able to control their digit forces in an anticipatory manner (less TE) were better able to smoothly navigate the bead along the curves, imparting less force onto the wire.

Linking Clinical Measures to the BMHF Test

Both clinical and laboratory assessments have been used to examine how sensorimotor deficits such as reduced grip/pinch strength, impaired pressure sensitivity, two-point discrimination, and stereognosis affect hand function. Impairments in grip/pinch strength, moving 2-point discrimination, stereognosis, and spasticity have been shown to predict scores on clinical tests such as the Assisting Hand Assessment, Jebsen Taylor Hand function test and Pegboard test (Decraene et al., 2021; Sakzewski et al., 2010). In another model, two-point discrimination, spasticity, and pinch strength best related to the ability of children with unilateral spastic cerebral palsy to adapt and scale their grip force during prehensile tasks (Gordon & Duff, 1999). The relationships between sensorimotor parameters and dexterity vary according to the specific parameters measured and the tasks involved in each assessment. Collectively, these studies highlight the value to clinicians in understanding which sensorimotor measures best relate to the performance of a given dexterity test.

For typically developing children and adolescents, we found that greater maximum pinch grip strength predicted better performance on the BMHF test (lower total force). This result was somewhat surprising given that the BMHF test requires very little strength. The bead is small, lightweight, and slides freely over the metal wire; very low forces are required to manipulate the bead. We speculate that greater maximum pinch strength, predicting lower total force on the BMHF test, can be attributed to the development of independent force control for precision pinch (Schieber & Santello, 2004); the primary grip pattern chosen to manipulate the bead. Producing a maximum pinch force requires the ability to isolate and direct fingertip forces, a capability that improves with age (Smits-Engelsman et al., 2003). Maintaining isometric precision pinch force across varying percentages of maximum voluntary contraction requires the development of neuronal connections and pathways (Beck et al., 2021) to isolate (Shim et al., 2007) and scale the forces of the specific muscles involved in executing an isometric precision pinch (Dayanidhi et al., 2013; Schieber & Santello, 2004; Smits-Engelsman et al., 2003).

Stereognosis was not a contributor to performance on the BMHF test for children and adolescents. This was due to the small number of children who scored less than a perfect score, although it is worth noting that those children who missed at least one object on the stereognosis test tended to produce higher total force. In typically developing children, it may not be possible to test whether stereognosis plays a role in performance. A larger sample, younger ages, and/or an alternative measure of tactile sensibility would be required. Given the importance of stereognosis as a clinical predictor of dexterity in children with impairments, and the importance of online sensory feedback and integration during dexterous manipulation tasks (R. S. Johansson & Flanagan, 2009; Parikh et al., 2020), a sensory capability/parameter is likely part of the missing, unexplained variance in our model.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is the lack of participants in preadolescence, ages 12- 14 years. Thus far, the primary focus of the BMHF test has been quantifying performance in the age ranges of 4-10yrs, when force control for manipulating objects is known to develop. Additionally, based on the parallel development of dexterity scores and neuroanatomical development (Dayanidhi et al., 2013), we expect that additional participants aged 12-14 years would not significantly change the relationship between total force and age. Despite the smaller sample size in pre-adolescence, the findings from this work support larger psychometric studies in clinical populations.

Our findings highlight the importance of a force control measure in clinical assessment of hand functions for daily tasks that require precision. Specifically, we observed how sensorimotor capabilities of anticipatory control and maximum precision pinch strength can predict performance on the BMHF test, an activity-based assessment of hand function. The current study adds evidence to support the use of more sensitive measures in clinical assessments of hand function. A better understanding of how the development of sensorimotor capabilities influences treatment outcomes can aid in the refinement of rehabilitation protocols and treatments (Contreras-Vidal et al., 2005; Gordon, 2016; Gordon et al., 1999; Kleim & Jones, 2008; Matusz et al., 2018; Parvinpour et al., 2020; Peterson & Prigge, 2020). For clinicians, this could mean a more complete evaluation of a child’s hand function and better-informed intervention planning. The findings support using sensitive, force-based measures in both clinical practice and research to improve outcomes for children who struggle with fine motor tasks. This work contributes to occupational therapy by advancing assessment methods that can guide more targeted and effective treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

The work reported in this article was primarily supported by a research grant to Pranav J. Parikh from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Center for Smart Use of Technologies to Assess Real-World Outcomes (C-STAR) at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, which was awarded under Grant P2CHD101899. This work was also supported by NIH/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R25HD106896 and the University of Houston CLASS Research Progress Grant to Pranav J. Parikh.

References

- Beck, M. M. , Spedden, M. E., Dietz, M. J., Karabanov, A. N., Christensen, M. S., & Lundbye-Jensen, J. Cortical signatures of precision grip force control in children, adolescents, and adults. eLife 2021, 10, e61018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumin, G. , & Kayihan, H. Effectiveness of two different sensory-integration programmes for children with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation 2001, 23, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, K. J. , Cook, K. M., Hynes, S. M., & Darling, W. G. Slowing of dexterous manipulation in old age: Force and kinematic findings from the “nut-and-rod” task. Experimental Brain Research 2010, 201, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Vidal, J. L. , Bo, J., Boudreau, J. P., & Clark, J. E. Development of visuomotor representations for hand movement in young children. Experimental Brain Research 2005, 162, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, D. L. , Quinlivan, J., Owen, B. F., Shaffrey, M., & Abel, M. F. Spasticity versus strength in cerebral palsy: Relationships among involuntary resistance, voluntary torque, and motor function. European Journal of Neurology 2001, 8, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, W. G. , Peterson, C. R., Herrick, J. L., McNeal, D. W., Stilwell-Morecraft, K. S., & Morecraft, R. J. Measurement of coordination of object manipulation in non-human primates. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2006, 154, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayanidhi, S. , Hedberg, Å., Valero-Cuevas, F. J., & Forssberg, H. Developmental improvements in dynamic control of fingertip forces last throughout childhood and into adolescence. Journal of Neurophysiology 2013, 110, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decraene, L. , Feys, H., Klingels, K., Basu, A., Ortibus, E., Simon-Martinez, C., & Mailleux, L. Tyneside Pegboard Test for unimanual and bimanual dexterity in unilateral cerebral palsy: Association with sensorimotor impairment. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2021, 63, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engsberg, J. R. , Ross, S. A., & Collins, D. R. Increasing ankle strength to improve gait and function in children with cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Pediatric Physical Therapy 2006, 18, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedrizzi, E. , Pagliano, E., Andreucci, E., & Oleari, G. Hand function in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: Prospective follow-up and functional outcome in adolescence. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 2003, 45, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssberg, H. , Kinoshita, H., Eliasson, A. C., Johansson, R. S., Westling, G., & Gordon, A. M. Development of human precision grip I: Basic coordination of force. Experimental Brain Research 1991, 90, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssberg, H. , Kinoshita, H., Eliasson, A. C., Westling, G., & Gordon, A. M. Development of human precision grip. II. Anticipatory control of isometric forces targeted for object’s weight. Experimental Brain Research 1992, 90, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q. , Zhang, W., & Santello, M. Anticipatory Planning and Control of Grasp Positions and Forces for Dexterous Two-Digit Manipulation. The Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 30, 9117–9126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, D. M. , Zhang, Z., Umberger, G., Mahood, K., Smith, M., Smith, C., & Gerhardt, G. A. An automated movement assessment panel for upper limb motor functions in rhesus monkeys and humans. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 1999, 89, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. M. (2016). Impaired Voluntary Movement Control and Its Rehabilitation in Cerebral Palsy. In J. Laczko & M. L. Latash (Eds.), Progress in Motor Control (Vol. 957, pp. 291–311). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. M. , Charles, J., & Duff, S. V. Fingertip forces during object manipulation in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. II: Bilateral coordination. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 1999, 41, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. M. , Charles, J., & Steenbergen, B. Fingertip Force Planning During Grasp Is Disrupted by Impaired Sensorimotor Integration in Children With Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy. Pediatric Research 2006, 60, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. M. , & Duff, S. V. Relation between clinical measures and fine manipulative control in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 1999, 41, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. M. , Westling, G., Cole, K. J., & Johansson, R. S. Memory representations underlying motor commands used during manipulation of common and novel objects. Journal of Neurophysiology 1993, 69, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutterman, J. , Lee-Miller, T., Friel, K. M., Dimitropoulou, K., & Gordon, A. M. Anticipatory Motor Planning and Control of Grasp in Children with Unilateral Spastic Cerebral Palsy. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R. S. , & Cole, K. J. Sensory-motor coordination during grasping and manipulative actions. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 1992, 2, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R. S. , & Flanagan, J. R. Coding and use of tactile signals from the fingertips in object manipulation tasks. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 2009, 10, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R. , & Westling, G. Coordinated isometric muscle commands adequately and erroneously programmed for the weight during lifting task with precision grip. Experimental Brain Research 1988, 71, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleim, J. A. , & Jones, T. A. Principles of Experience-Dependent Neural Plasticity: Implications for Rehabilitation After Brain Damage. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2008, 51, S225–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusz, P. J. , Key, A. P., Gogliotti, S., Pearson, J., Auld, M. L., Murray, M. M., & Maitre, N. L. Somatosensory Plasticity in Pediatric Cerebral Palsy following Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy. Neural Plasticity 2018, 2018, 1891978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. H. , Jung, J. H., Hahm, S. C., & Cho, H. Y. The effects of task-oriented training on hand dexterity and strength in children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy: A preliminary study. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2017, 29, 1800–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, K. M. , & Knudson, D. V. Change in strength and dexterity after open carpal tunnel release. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2001, 22, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, P. J. , & Cole, K. J. Handling objects in old age: Forces and moments acting on the object. Journal of Applied Physiology 2012, 112, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, P. J. , Fine, J. M., & Santello, M. Dexterous Object Manipulation Requires Context-Dependent Sensorimotor Cortical Interactions in Humans. Cerebral Cortex 2020, 30, 3087–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvinpour, S. , Shafizadeh, M., Balali, M., Abbasi, A., Wheat, J., & Davids, K. Effects of Developmental Task Constraints on Kinematic Synergies during Catching in Children with Developmental Delays. Journal of Motor Behavior 2020, 52, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J. K. , & Prigge, P. P. Early Upper-Limb Prosthetic Fitting and Brain Development: Considerations for Success. Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics 2020, 32, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, V. L. , Ajoy, A., Johnston, C. A., Gogola, G. R., & Parikh, P. J. The Bead Maze Hand Function Test for Children. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2024, 78, 7804205010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, V. L. , & Parikh, P. J. Anticipatory control of digit kinematics: A developmental milestone for motor skill acquisition. Experimental Brain Research 2025, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakzewski, L. , Ziviani, J., & Boyd, R. The relationship between unimanual capacity and bimanual performance in children with congenital hemiplegia. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2010, 52, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M. H. , & Santello, M. Hand function: Peripheral and central constraints on performance. Journal of Applied Physiology 2004, 96, 2293–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, E. D. , & Chung, K. C. Validity and Responsiveness of the Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test. Journal of Hand Surgery 2010, 35, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J. K. , Oliveira, M. A., Hsu, J., Huang, J., Park, J., & Clark, J. E. Hand digit control in children: Age-related changes in hand digit force interactions during maximum flexion and extension force production tasks. Experimental Brain Research 2007, 176, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits-Engelsman, B. C. M. , Westenberg, Y., & Duysens, J. Development of isometric force and force control in children. Cognitive Brain Research 2003, 17, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R. , Dale, M., Wicks, S., Toose, C., & Pacey, V. Reliability of a novel technique to assess palmar contracture in young children with unilateral hand injuries. Journal of Hand Therapy 2022, 35, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofani, M. , Castelli, E., Sabbadini, M., Berardi, A., Murgia, M., Servadio, A., & Galeoto, G. Examining Reliability and Validity of the Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test Among Children With Cerebral Palsy. Perceptual and Motor Skills 2020, 127, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, A. L. Does hand function continue to develop in older children and adolescents with cerebral palsy? Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2023, 65, 304–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. , Gordon, A. M., Fu, Q., & Santello, M. Manipulation after object rotation reveals independent sensorimotor memory representations of digit positions and forces. Journal of Neurophysiology 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).