1. Introduction

Small modular reactors (SMRs) are relatively compact nuclear plants with a capacity of up to 300 MW. Compared to conventional NPPs, they take up less space, are easier to assemble and require less investment [

1]. Due to their modular design and factory fabrication capabilities, these reactors can be quickly delivered and installed even in remote or energy-poor regions where the construction of large power units would be too expensive or complex [

2].

In addition to their relatively simple design, SMRs are characterised by high levels of safety [

3]. Due to their relatively low power output and reduced operating parameters, in the event of an abnormal situation they can automatically shut down without operator intervention and without external power supply. This is possible thanks to passive safety systems that operate through natural physical processes such as natural circulation, convection, gravity and pressure rise. As a result, the risk of radioactive emissions into the environment is significantly minimised and often completely eliminated, making such plants particularly reliable and safe for people [

4].

Moreover, fuel replacement is much less frequent in SMRs - approximately every 3-7 years, whereas in conventional NPPs it is done every 1-2 years. Today, most SMRs use low-enriched uranium (LEU), which is a safe and proven fuel [

5,

6]. In particular, the U.S. NuScale and South Korea's SMART operate on such uranium. Argentina's CAREM and China's ACP100 use conventional uranium fuel and are designed for both domestic and international applications. Whereas Russia's RITM-200 reactors, which are already on icebreakers and are planned for the Arctic, use uranium with higher enrichment, ensuring autonomous operation in harsh conditions [

7],[

8]. In addition, new generation MMRs, such as Moltex and TerraPower, are being actively developed. They use reprocessed nuclear fuel or innovative liquid-salt technologies based on thorium and uranium. This makes nuclear power more sustainable and contributes to the reduction of nuclear waste [

9].

This article provides an overview of the main types of MSRs, categorised by fuel type and application. Both reactor plants fuelled by LEU and reactors fuelled by rarer and more promising fuels, such as thorium, reprocessed nuclear fuel and uranium with different degrees of enrichment (HALEU and HEU), including metallic compositions, are considered. Special attention is paid to new fuel cycles that can improve the efficiency and environmental friendliness of nuclear power. These include the transmutation of thorium into fissile uranium and the reuse of actinides, which can significantly reduce the amount of radioactive waste and move closer to a closed fuel cycle. Moreover, the article examines the current development of MMR technologies in the world: it highlights the most promising projects, analyses the regulatory, infrastructure and geopolitical challenges that may affect their implementation.

2. Advantages of Modular Nuclear Reactors

MMRs have a number of important advantages: high safety, simple and reliable design, and the ability to be installed in remote or inaccessible areas where energy consumption is low [

10]. In such regions, there is often no need for large-scale power generation facilities, and it is the SMRs that can effectively cover localised power needs [

11]. The modular approach makes these reactors easier to standardise and suitable for mass production, which reduces construction costs and simplifies operation. Universal design elements and proven technical solutions make maintenance more predictable and economical.

Conventionally, MMRs are divided by power level into two main categories [

12]:

Ultra-small modular reactors (vSMR, up to 50 MWe) - used mainly in isolated areas, remote industrial sites, military bases and other areas with limited access to centralised power.

Small Modular Reactors (SMR, 50 to 300 MWe) - a balanced solution combining sufficient power with mobility, suitable for a wider range of applications, including power supply to small towns, industrial facilities and infrastructure.

One of the key advantages of SMRs is their high autonomy - they can operate for long periods of time without the constant presence of maintenance personnel. And because these reactors are delivered as prefabricated modules, they can be quickly transported and started up in the most remote or inaccessible areas. This makes SMRs particularly useful not only for stable power supply in remote locations, but also for rapid response in emergency situations. In addition, such plants are not only used in the power sector: they are also suitable for district heating, seawater desalination and even hydrogen production - a key element of future green energy [

13,

14].

Although today microreactors represent a real technological breakthrough in nuclear power, their history dates back to space exploration. Back in 1965, the United States launched the SNAP-10A nuclear reactor with a power of only 0.5 kW, which provided satellite operation for 43 days - until the electrical equipment failed. In 1964, the Soviet Union created the Romashka reactor, which operated on the principle of direct thermoelectric conversion of nuclear fission heat into electricity. It produced 6.1 MWh and operated for more than 15,000 hours. Later, the USSR developed a 3 kW BUK unit, which was used in 32 space missions from 1970 to 1988. And in the 1980s, the US launched the SP-100 project, a concept of a lithium-cooled reactor for spacecraft using heat pipes and thermoelectric converters. Thus, microreactors have been serving for decades as a reliable source of energy in the most extreme conditions - from orbit to outer space [

15,

16,

17].

It is important to realise that the so-called nuclear batteries used in some space missions are not full nuclear reactors. They are not based on a fission chain reaction, but on the natural radioactive decay of isotopes such as tritium (³H), strontium-90 (⁹⁰Sr), plutonium-238 (²³⁸Pu) and curium-244 (²⁴⁴Cm). The heat produced is converted into electricity using the Seebeck thermoelectric effect. Usually, such sources produce only a few kilowatts and their efficiency is quite low. For example, the Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG), which is used in long-range spacecraft, can produce about 2 kilowatts of electricity with a thermal output of 125 MW - giving an efficiency of only about 6.25 per cent. Nevertheless, reliability and durability make these systems indispensable for environments where other power sources simply won't work [

18,

19].

The low MMR is usually combined with compact dimensions, making it possible to install even where conventional reactors would not fit. Due to their compactness, such plants can easily fit into limited spaces - where the construction of a large nuclear plant would be impossible. They can be integrated into the infrastructure of cities, small towns, industrial plants, ports, ships and even remote sites with limited access [

20]. In particular, Sweden's 3 MW SEALER microreactor has a vessel weighing less than 30 tonnes, with a diameter of just 2.75 metres and a height of 6 metres - all of which fits into an area of about 600 m². The more powerful US mPower (190 MW) weighs around 500 tonnes, but its design (4.15 m in diameter and 27.4 m high) allows it to be transported by rail. The ultra-compact ELENA (68 kW) can be disassembled into two modules, which is convenient for transporting it to hard-to-reach places. And the Danish CMSR reactor (100-115 MW) is only 2.5 metres high, making it one of the lowest profile plants. Other current examples include eVinci (0.2 to 15 MW), a compact waste-to-energy plant from Copenhagen Atomics (20 MW), as well as more powerful reactors such as SUPERSTAR (120 MW), UK SMR and Westinghouse SMR (up to 225 MW). All are being developed with a focus on mass production, mobility and versatility of application [

21].

Table 1 summarises the current status of the MMR. So far, only one of them has been commissioned worldwide - the rest are still under development or under construction. Although some of the plants are slightly above the 300 MW threshold, they are still categorised as SMRs due to their modular architecture and compactness. Today, reactors fuelled by low-enriched uranium (LEU, less than 20 per cent U-235) are the most widespread. This fuel meets international safety standards and is easier to handle. Such solutions include NuScale Power Module (USA) [

22], SMART (South Korea) [

23], CAREM (Argentina), ACP100 (China) [

24] and the BWRX-300 boiling reactor from GE Hitachi (USA/Japan) [

25,

26,

27]. All of them use proven uranium oxide (UO₂) fuel similar to that used in conventional nuclear power plants. Russia's RITM-200 reactor, which is already operating on nuclear icebreakers and is planned for use in land-based power plants, also uses uranium fuel, but with a higher level of enrichment. This makes it possible to extend the duration of the fuel campaign and increase the plant's efficiency. In addition to conventional solutions, reactors using alternative fuel types are being actively developed. For example, liquid salt reactors such as Seaborg CMSR (Denmark) and TAP (USA) use fuel in dissolved form, which makes it possible to reprocess it directly during operation. Fast sodium reactors such as the ARC-100 (Canada/USA), as well as metallic compact reactors such as Oklo Aurora, focus on the use of reprocessed or highly enriched fuel. Thus, next-generation technologies that open up new opportunities for a closed nuclear fuel cycle, reducing radioactive waste and increasing the sustainability of nuclear power in the long term [

28,

29,

30,

31].

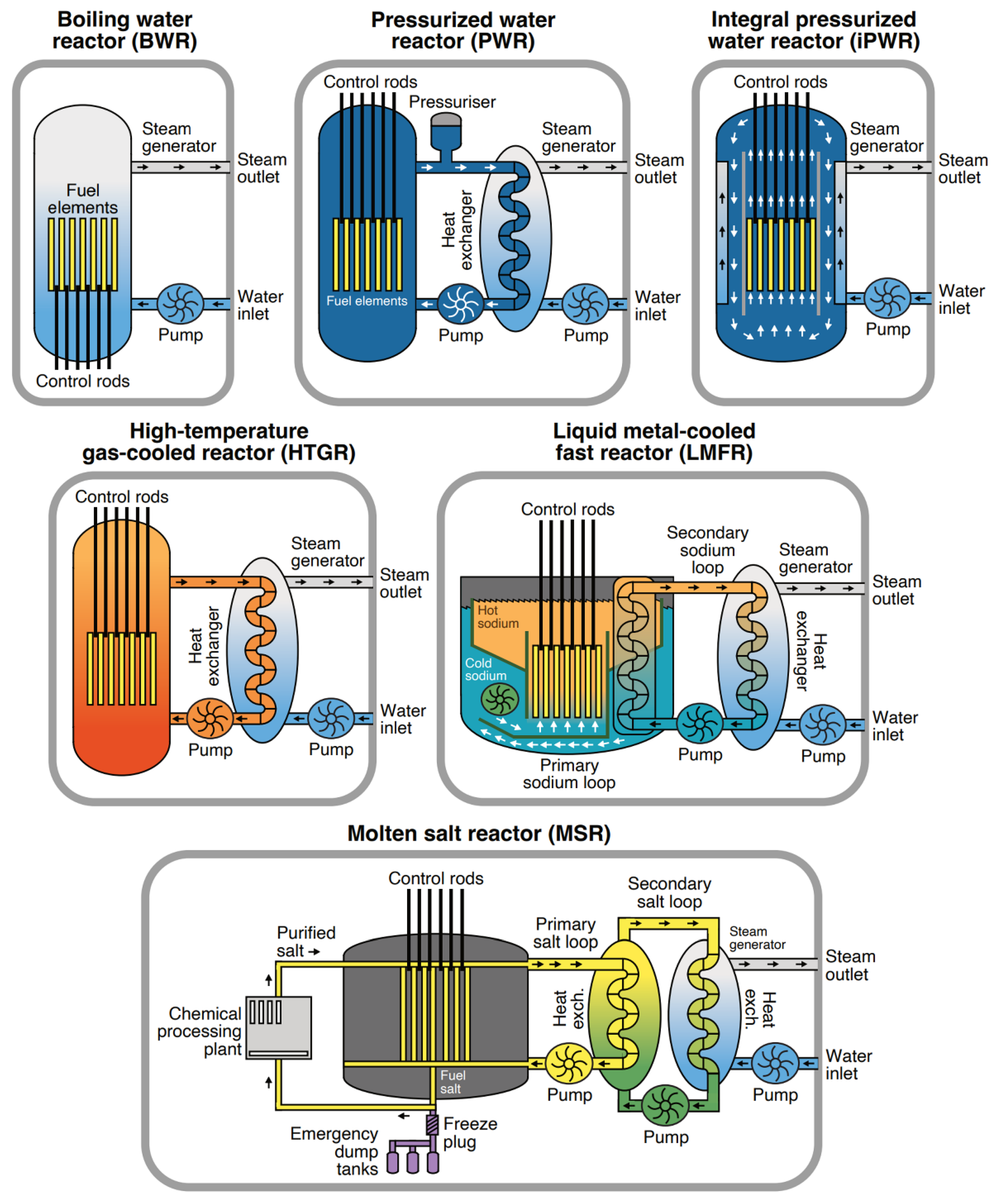

Figure 1 illustrates the main technological solutions underlying modern SMRs, with a focus on differences in steam generation methods. In most cases, conventional steam turbines are employed; however, certain high-temperature reactor concepts—such as gas-cooled design also incorporate Brayton cycles using air as the working fluid. Despite structural and thermal design differences, all these systems ultimately serve the same function: driving a turbogenerator that converts thermal energy into electricity. This highlights the versatility of the approach, where diverse engineering configurations are aligned toward a common goal—reliable and scalable power generation.

Overall, small and micro reactors offer a flexible and scalable solution for localised energy supply. Thanks to their compact design, autonomy and broad functionality, they are suitable for a wide range of applications, from power and heat generation to water desalination and hydrogen production. Their reliability has already been proven in practice, including operation in the harshest environments, even in space. Today's development of SMRs is aimed at making them even more affordable and efficient: mass production is simplified, costs are reduced, and applications are expanded. All of this makes small modular reactors a promising basis for future low-carbon energy.

3. Small Modular Reactors on Low Enriched Fuel

To date, LEU-fuelled reactors (with U-235 content less than 20%) are the most mature and widely used category among MSRs. Due to their proven technology, high level of safety and compliance with international requirements, such plants are considered as one of the main contenders for mass introduction into the civilian energy sector [

37,

38,

39].

LEU fuel is recognised as safe from a nuclear non-proliferation point of view - this has been confirmed by organisations such as the IAEA and the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). Its use reduces the risks of military use and makes it easier to obtain export licences. In addition, LEU has long been used in large commercial nuclear power plants, which has provided a wealth of practical experience, from reliable operation and maintenance to the development of clear regulatory standards [

40].

One of the most famous and advanced projects in the field of small modular reactors based on low-enriched uranium is the NuScale Power Module (USA). It was the first modular reactor officially approved by the NRC [

41]. Each module of this plant generates 77 MW of electricity and is built according to the classical water-water reactor (PWR) scheme. NuScale's special feature is its high autonomy: one module can operate for up to 12 years without fuel reloading. In addition, the system is scalable - up to 12 modules in one complex, which allows it to be adapted to the needs of different regions and energy consumption scenarios.

Another striking example is South Korea's SMART (System-integrated Modular Advanced Reactor). It is a 100 MW compact integrated PWR reactor designed not only for power generation but also for seawater desalination. This multifunctionality makes it particularly useful for coastal or arid areas where not only power generation but also access to fresh water is important [

42].

China's ACP100 project, based on PWR technology, is in the final stages of construction and has already become a symbol of China's commitment to bringing modular nuclear technology into the civilian sphere. It is designed to power remote areas, industrial zones and infrastructure facilities [

43]. It pays special attention to automation and state-of-the-art safety systems, both active and passive, in line with the latest global trends in nuclear power.

Advantages of LEU-based small modular reactors [

44,

45,

46]:

Reliability and technological maturity. LEU fuel has been widely used in the power industry for decades. This experience reduces risks when introducing new reactors and speeds up the licensing and operation process.

Ready infrastructure. LEU-fuel production and supply rely on existing and certified chains: from uranium enrichment plants to fuel assembly fabrication factories.

Serialisation and standardisation. Thanks to standardised designs, LEU reactors can be mass-produced, which significantly reduces their cost and facilitates logistics for deployment in different countries and regions.

Export Control Compliance. Unlike HEU or reprocessed fuel reactors, LEU plants are easier to align with international nonproliferation regulations, including nuclear material control treaties.

Application flexibility. Due to their compactness, high safety and autonomy, these reactors are suitable for remote communities, small towns, industrial sites and can complement renewable sources in hybrid energy systems.

Multifunctionality. LEU reactors can provide not only electricity but also heat, making them effective for district heating, seawater desalination and industrial applications - especially in environments where reliable and sustainable energy is needed.

LEU reactors are finding their place in the energy industry of the future, especially in the next generation of smart grids and energy infrastructure. They provide a stable and predictable energy supply, compensating for the instability of solar and wind sources. This combination is becoming a key element in achieving emission reduction targets and the transition to clean energy [

47].

Thanks to international support, a well-established production base, a high degree of standardisation and a positive reputation for nuclear safety, LEU small modular reactors are now considered one of the most reliable and promising areas of civil nuclear power development. Their compactness, adaptability and ability to operate in decentralised environments make them an important part of the global transition to sustainable, low-carbon energy.

4. Small Modular Reactors Using Highly Enriched Fuel

Small modular reactors (SMRs) using highly enriched uranium (HEU, above 20 per cent U-235) or highly enriched fuel (HALEU, between 5-20 per cent) represent a promising technology for the development of compact and energy-efficient autonomous power systems [

48]. The key advantage of SMRs is their ability to operate for 10-20 years without the need for fuel replacement, which makes them particularly relevant in remote regions, military facilities and space missions. However, realisation of such a long fuel cycle requires the use of fuel elements with cladding resistant to high radiation and thermal loads, which makes it possible to achieve a deep degree of fuel burnup and reduce the risks associated with hydrogen formation [

49].

Practical implementation of such technologies is already underway in a number of countries. One example is the Russian RITM-200 reactor, successfully used on nuclear icebreakers and considered as an option for land-based power plants in the Arctic [

50]. Foreign solutions include the eVinci microreactor, developed by Westinghouse (USA), with a capacity from 200 kW to 5 MW, designed to supply power to isolated and hard-to-reach areas [

51]. Another promising project, Oklo Aurora, uses reprocessed highly enriched fuel and a passive cooling system, but it is currently facing obstacles at the licensing stage. Special attention should be paid to floating nuclear power plants, such as OFNP, which have internal safety systems and passive residual heat removal. Russia is actively implementing and developing such plants, including ABV-6M, KLT-40S and RITM-200 reactors based on the thermal spectrum and fuel element layout similar to VVER-1000. KLT-40S type units are already operating at the Akademik Lomonosov floating NPP and are being considered for such purposes as seawater desalination, process support and shipboard applications [

52,

53].

The design features and fuel policy of SMRs significantly distinguish them from conventional reactors. Unlike standard large light water reactors (LWRs), where the fuel enrichment level is typically less than 5 per cent, the modular reactors described above utilise a once-through fuel cycle with enrichments up to 20 per cent. For example, the KLT-40S uses uranium enriched to 18.6 %. Due to the limited core volume, such reactors are characterised by lower power density and noticeable neutron losses in radial and axial directions - up to 7 % [

54,

55].

Similar technological approaches have been reflected in international analyses. According to the Evaluation and Screening (E&S) study conducted by the US Department of Energy's Office of Nuclear Energy (DOE-NE), various nuclear fuel cycles were categorised into 40 evaluation groups, taking into account such parameters as neutron spectrum, fuel reprocessing and other features. The floating reactors mentioned above are categorised in the EG02 group, which is characterised by the single use of enriched uranium in thermal or fast spectrum reactors with high burnup. As a typical example for the EG02 group, a modular high temperature gas cooled reactor (mHTGR) operating with 15.5 % enriched uranium and achieving a burn-up of about 120 GWpd/t is considered [

56,

57]. In parallel, the transition from HEU to safer alternatives is coming into focus. Despite the non-proliferation concerns associated with the use of highly enriched uranium (HEU), the focus of current developments is shifting towards a safer alternative - HALEU fuel. This type of nuclear fuel offers a balanced combination of high energy density, improved thermal efficiency, and resilience to changing operating conditions. Currently, active work is underway in the US and European countries to create infrastructure for HALEU production, which opens up opportunities for large-scale deployment of such systems [

58,

59,

60].

In general, HEU- and HALEU-based reactors are seen as a strategically important area of development. HEU- and HALEU-based plants are particularly relevant in cases where autonomy, compactness and high reliability are required, for example, for military facilities, research stations or remote settlements [

61]. The use of HALEU offers a compromise between the stringent requirements of nuclear safety and the pursuit of high energy efficiency, thus forming a sustainable basis for the development of a new generation of small modular reactors.

5. Small Modular Reactors Using Thorium Fuel

PurposeTorium-232 is considered a promising material for use in nuclear power, as it transforms into a fissile isotope of uranium-233 upon capture of thermal neutrons. This property makes thorium fuel a potential alternative to conventional uranium fuel cycles. Among its key advantages are its high abundance in nature, reduced plutonium-239 formation, and less long-lived radioactive waste. These characteristics make thorium a particularly attractive option for next-generation small modular reactors, especially in countries with significant reserves of the element [

62,

63].

Thorium's potential becomes particularly apparent when considering its behaviour in a one-way fuel cycle. In this approach, thorium exhibits a high conversion efficiency and reduced formation of secondary actinides, making it promising in terms of improving fuel efficiency. Although natural thorium reserves are about 3-4 times higher than uranium reserves, special conditions are required to start a thorium fuel cycle. Since thorium itself is not a fissile isotope, it must be converted into uranium-233 by thermal neutron irradiation. To initiate the chain reaction, fissile material, typically U-235, U-233 or Pu-239, must be present in the core [

64].

An additional advantage of thorium is its high reproduction factor in the thermal neutron spectrum, exceeding similar values for U-235 and Pu-239. This contributes to improved fuel cycle performance, especially in terms of conversion efficiency. From a nonproliferation perspective, the use of thorium in the cores of PWRs can significantly limit the generation of weapons-grade plutonium [

65]. Due to its high internal conversion rate, thorium fuel is seen as an attractive solution for long-life reactors without the need for rebooting.

The similarity of natural thorium to uranium as a heavy nuclide also supports interest in its application in nuclear facilities. Studies show that thorium-based fuel offers several advantages over uranium counterparts - including better conversion characteristics due to the high fissile capacity of U-233, more stable reactivity during vapour cavity formation, and high burnup efficiency [

66]. However, the thorium fuel cycle is of less concern in the context of nuclear proliferation.

Looking at specific reactor types, thorium fuel cycles in water-cooled (LWR) and heavy water reactors (HWR) exhibit improved neutron-physical characteristics compared to uranium and plutonium systems [

67]. This opens the way to more efficient fuel utilisation, as well as to strategies with increased burnup and spent fuel recyclability.

Moreover, the applicability of thorium fuel in existing water-cooled reactor designs has been specifically studied. The results show that thorium is able to provide higher reactivity excess, which can extend the fuel lifetime. The neutron-physical parameters of thorium fuel assemblies for modern PWRs have also been investigated - and no change in core geometry is required [

68]This simplifies thorium fuel integration and helps address spent fuel management and non-proliferation challenges.

Computer modelling confirms that thorium fuel cycles (ThFCs) can effectively complement or even partially replace conventional uranium and plutonium chains [

69]. This not only improves reactor performance, but also reduces the burden on the SNF reprocessing infrastructure. At the same time, the safety parameters of thorium fuel assemblies remain within the limits acceptable for existing PWR designs.

Nevertheless, the transition to a closed cycle Th-U-233 requires solving a number of technical problems [

70]. Since thorium itself is not a fissile material, the reactor system must initially contain an external fissile fuel additive. For this purpose, mixed oxide fuels such as (LEU-Th)O₂ are used. To ensure stable and safe operation, the amount of U-233 formed during irradiation must be precisely controlled [

71].

Against this background, specific projects centred on thorium technologies are being actively developed. Among them is ThorCon, a liquid-salt reactor intended for serial deployment in Indonesia [

72]. India is implementing a large-scale government programme for the use of thorium fuel - IThER (Indian Thorium Energy Reactor), which is facilitated by the presence of significant natural reserves [

73]. Earlier the concept of LFTR (Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactor), developed at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (USA), laid the foundation for modern developments in this field [

74].

Despite active research, serious challenges remain. In particular, the creation of a closed cycle of Th-U-233 requires radiochemical technologies that are resistant to extreme conditions - high radiation and aggressive chemical environment. In addition, there is no unified regulatory framework and accumulated experience of industrial operation of such systems. Nevertheless, thorium small modular reactors have significant potential: they provide high fuel efficiency, demonstrate improved safety characteristics and help reduce the volume of radioactive waste. All these qualities make thorium a key element in the strategy of sustainable and environmentally safe development of nuclear energy of the future.

6. Small Modular Reactors on Metallic Fuel and on Reprocessed Fuel

One of the most promising areas in the development of small modular reactors (SMRs) is considered to be the use of metallic nuclear fuel - in particular, uranium-zirconium (U-Zr) and molybdenum (U-Mo) alloys. Originally developed for fast reactors, these materials have a number of unique characteristics that make them particularly attractive for compact and highly efficient power systems. Metallic fuel provides significantly higher energy density than conventional oxide forms and is characterised by excellent thermal conductivity. This allows for efficient heat dissipation from the core and, consequently, a reduction in its geometric dimensions. The compact design opens up a wide range of possibilities for the use of such reactors in a wide variety of environments, from remote areas to space missions and military mobile power plants [

75,

76,

77].

These features are embodied in a number of modern developments. Due to its high temperature resistance and ability to adapt quickly to changes in thermal load, metallic fuels are particularly well suited for microreactors designed for backup power supply, field conditions and operation in extreme environments. One prominent example is the ARC 100 project being developed in Canada and the US. It is a fast sodium reactor designed for long-term autonomous operation without fuel reloading and is designed based on passive safety principles, which reduces operational risks. Similar interest in metallic fuel is also manifested in space developments, for example, in the framework of the American SP-100 programme, which created lithium-cooled reactors with metallic fuel capable of operating in weightlessness and increased radiation background [

78]. Another example is the Oklo Aurora microreactor, which was originally envisaged as a reprocessed fuel plant but also included uranium metal variants combined with passive cooling and an ultra-compact design [

79].

Despite the obvious advantages, metallic fuel technology is also accompanied by certain engineering limitations. Nevertheless, the use of metallic fuels comes with a number of technical challenges. Its safe operation requires reliable sealing, protection against oxidation - especially at high temperatures - as well as strict temperature control in the heat release zone. This places high demands on the design of cladding, the quality of fuel element sealing and the operation of diagnostic systems. Despite such difficulties, the combination of advantages, such as high energy density, excellent thermal conductivity, and resistance to sudden changes in heat load, makes metallic fuel one of the most promising options for next-generation compact nuclear plants.

Against the backdrop of the search for sustainable solutions, the use of reprocessed nuclear fuel is also actively developing. In parallel, the use of reprocessed nuclear fuel, including minor actinides such as neptunium, americium and curium, is being developed. Such approaches are aimed at significant reduction of spent fuel volumes and more complete utilisation of the energy potential of previously recovered materials [

80]. The inclusion of reprocessed isotopes in the fuel cycle makes it possible to form a virtually closed system where waste is transformed into a resource for new reactor plants. This solution is becoming increasingly important against the backdrop of growing environmental requirements, the need to manage accumulated waste, and the desire to transition to sustainable nuclear technologies.

Closed fuel cycle ideas are increasingly being realised as part of innovative reactor concepts. One of the most ambitious projects in the field of new nuclear technologies is the Compact Molten Salt Reactor (CMSR) being developed by the Danish company Seaborg Technologies [

81]. In this concept, the fuel circulates as a melt directly in the primary circuit, eliminating the need for traditional fuel assemblies. This engineering solution improves safety, reduces sensitivity to emergencies and enables the realisation of fully passive residual heat removal. The modular nature of the CMSR makes it particularly suitable for mass production and rapid deployment in regions with limited infrastructure [

82]. A similar idea is being developed by Copenhagen Atomics, which is developing small-sized reactors using recycled actinides. The focus here is on technology availability, lower costs and shorter deployment times, making these plants promising for commercial applications in decentralised power grids [

83].

Other engineering developments continue in this direction. Complementing this direction, the Canadian company Moltex is developing the SSR-W reactor, which implements the concept of sustainable incineration of radioactive waste. The facility combines the use of reprocessed fuel with passive safety systems and is designed for long-term operation near existing SNF storage facilities, which allows for a significant reduction in logistical and environmental costs.

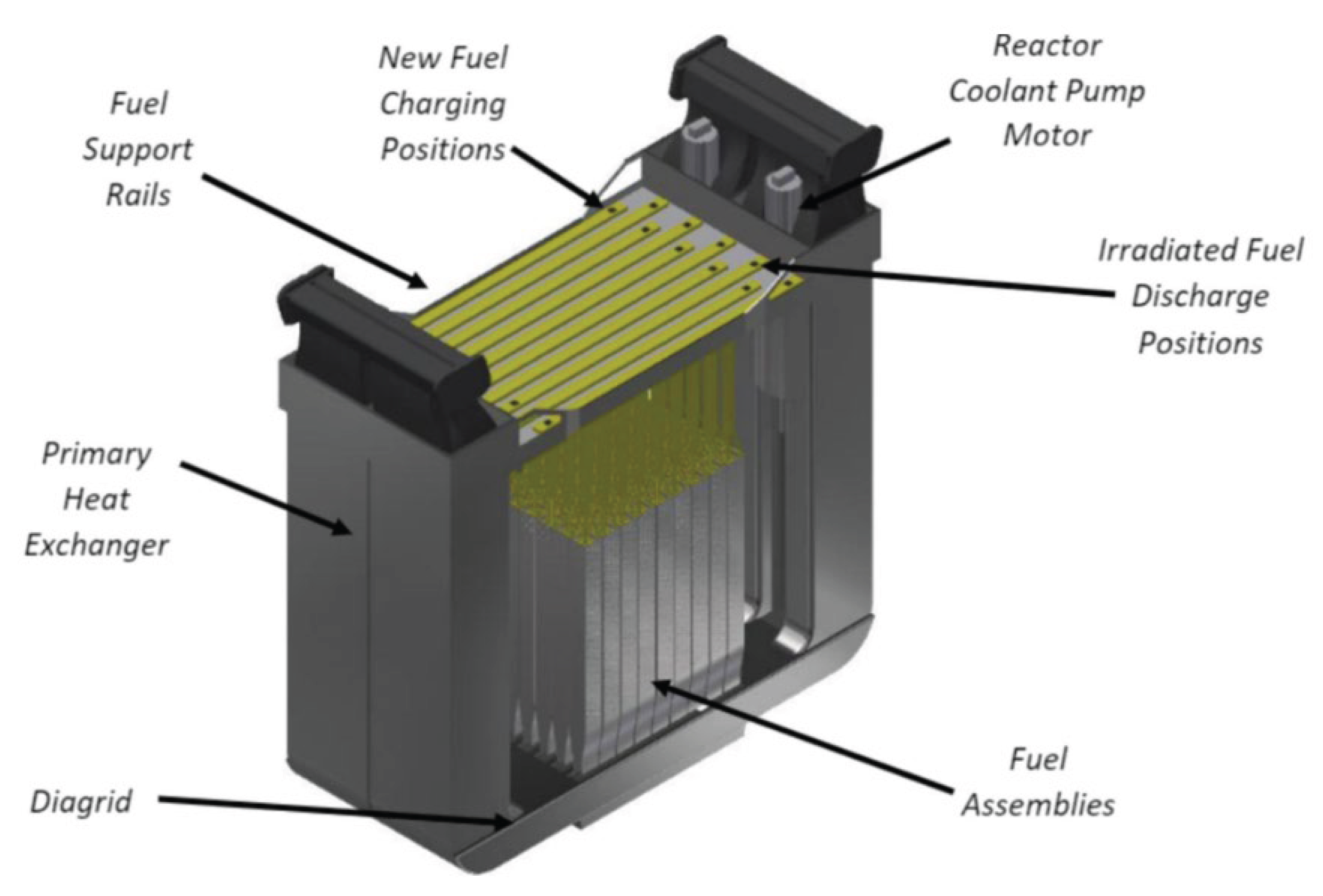

Figure 2 shows the geometry of the SSR W reactor module and fuel assembly containing fuel tubes. This design ensures efficient placement of reprocessed fuel and contributes to the thermal efficiency of the system [

84,

85]. However, the implementation of such technologies requires appropriate infrastructure, from reprocessing and isotopic separation plants to systems for the safe handling of high-level radioactive substances, as well as international regulations and legal support. Nevertheless, the long-term benefits, including reduced dependence on natural uranium, reduced disposal volumes, and increased energy independence, make such developments extremely promising in the context of sustainable nuclear energy [

86].

Such solutions become especially relevant for countries with significant stockpiles of spent nuclear fuel. Small modular reactors running on reprocessed fuel are especially important for countries with significant accumulations of spent nuclear fuel, such as the United States, France, Russia and Japan. These countries are interested in developing closed nuclear fuel cycles that allow them to utilise long-lived isotopes, extend the lifetime of storage facilities, and increase the efficiency of the use of already recovered resources. In this context, SMRs using reprocessed actinides become not only a source of energy, but also a key tool in addressing environmental and resource challenges, contributing to sustainable development and the achievement of international climate and energy goals [

88,

89,

90].

Thus, the areas under consideration create the potential for a new stage in the development of nuclear energy. In general, the development of metallic and reprocessed fuel technologies opens a new chapter in the history of nuclear power - an era that prioritises not only energy efficiency and compactness of plants, but also environmental responsibility, resource intensity and technological adaptability. These approaches form the foundation for the creation of a new generation of nuclear systems capable of operating in different environments, meeting the challenges of the times and ensuring a reliable and sustainable energy supply in the long term.

7. Conclusion

The current development of small modular reactors (SMRs) demonstrates a wide variety of fuel solutions, each offering different approaches to sustainable, safe and efficient energy production. Low Enriched Uranium (LEU) reactors already represent a mature and reliable platform that is technically ready for large-scale deployment in power systems in different countries. A high level of standardisation, the availability of a production base and existing regulatory support make them the most realistic option for near-term commercial application. At the same time, HEU and HALEU reactors, despite nonproliferation and regulatory constraints, have serious potential in areas where autonomy and compactness are particularly important. In particular, HALEU-fuelled microreactors offer long periods of operation without fuel reloading, making them particularly promising for use in Arctic regions, defence facilities and space systems.

At the same time, the concepts of reprocessed fuel and actinide-based SMRs are being actively promoted, reflecting the strategic shift towards a closed nuclear fuel cycle. Such facilities make it possible not only to utilise accumulated stocks of spent fuel, but also to significantly reduce the environmental load, contributing to the overall sustainability of nuclear power. Against this background, thorium reactors are of interest as a solution based on more affordable raw materials with high long-term potential. Complementing the picture is the development of metallic fuels, which, due to their high energy density and heat resistance, offer new opportunities for compact, powerful and mobile energy systems. Thus, each of the fuel strategies mentioned above contributes to shaping the future architecture of global nuclear energy. Their further development should be based on the principles of science-based diversification, international partnership and country-specific adaptation. Together, small modular reactors can become the basis for a decentralised, reliable and environmentally oriented energy system for the 21st century.

The research is funded by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan IRN BR24993225

References

- Gao, X.; Chen, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Pan, P. Performance Assessment of a Multiple Generation System Integrating Sludge Hydrothermal Treatment with a Small Modular Nuclear Reactor Power Plant. Energy 2025, 315, 134323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotný, V.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.-B.; Rigby, A.; Saeed, R.M. Nuclear-Based Combined Heat and Power Industrial Energy Parks − Application of High Temperature Small Modular Reactors. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2025, 26, 101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignacca, B.; Locatelli, G. Economics and Finance of Small Modular Reactors: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 118, 109519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, T.H.; Kim, Y.I. Microgrid Control Incorporated with Small Modular Reactor (SMR)-Based Power Productions in the University Campus. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2025, 183, 105678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.; Miller, J.; Wu, Z. Implications of HALEU Fuel on the Design of SMRs and Micro-Reactors. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2022, 389, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, D.; Jiang, J. Review of Integration of Small Modular Reactors in Renewable Energy Microgrids. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 152, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, U.K.; Zhang, C. Phase-Based Safety Review of Micro and Small Modular Reactors from Design to Decommissioning. Safety Science 2025, 188, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanatta, M.; Patel, D.; Allen, T.; Cooper, D.; Craig, M.T. Technoeconomic Analysis of Small Modular Reactors Decarbonizing Industrial Process Heat. Joule 2023, 7, 713–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, N.; Silva, C.A.M.; Lorduy-Alós, M.; Gallardo, S.; Pereira, C.; Verdú, G. Neutronic Assessment of Stable Salt Reactor with Reprocessed Fuels. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2025, 218, 111383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, O.; Finin, G.; Ivaschenko, T.; Iatsyshyn, A.; Hrushchynska, N. Current State and Prospects of Smallmodule Reactors Application in Different Countries of the World. In Systems, Decision and Control in Energy IV: Volume IІ. Nuclear and Environmental Safety; Zaporozhets, A., Popov, O., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-3-031-22500-0. [Google Scholar]

- The Usage of Micro Modular Nuclear Reactors on Military Headquarters as a Prospective Solution to Achieve Energy Security and Improve National Defense | East Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Research. Available online: https://journal.formosapublisher.org/index.php/eajmr/article/view/3106 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Novotný, V.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.-B.; Rigby, A.; Saeed, R.M. Nuclear-Based Combined Heat and Power Industrial Energy Parks − Application of High Temperature Small Modular Reactors. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2025, 26, 101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.; Boarin, S.; Pellegrino, F.; Ricotti, M.E. Load Following with Small Modular Reactors (SMR): A Real Options Analysis. Energy 2015, 80, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanatta, M.; Patel, D.; Allen, T.; Cooper, D.; Craig, M.T. Technoeconomic Analysis of Small Modular Reactors Decarbonizing Industrial Process Heat. Joule 2023, 7, 713–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Usman, S. Advanced and Small Modular Reactors’ Supply Chain: Current Status and Potential for Global Cooperation. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2025, 184, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Arunachalam, M.; Elmakki, T.; Al-Ghamdi, A.S.; Bassi, H.M.; Mohammed, A.M.; Ryu, S.; Yong, S.; Shon, H.K.; Park, H.; et al. Evaluating the Economic and Environmental Viability of Small Modular Reactor (SMR)-Powered Desalination Technologies against Renewable Energy Systems. Desalination 2025, 602, 118624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M.; Dincer, I. A Clean Hydrogen and Electricity Co-Production System Based on an Integrated Plant with Small Modular Nuclear Reactor. Energy 2024, 308, 132834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs): A Review of Current Challenges and Future Applications - Chemical Communications (RSC Publishing). Available online: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2024/cc/d4cc03980g (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- (PDF) A Comprehensive Review of Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator. A B S T R C T. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360719626_A_comprehensive_review_of_Radioisotope_Thermoelectric_Generator_A_B_S_T_R_C_T (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Hidayatullah, H.; Susyadi, S.; Subki, M.H. Design and Technology Development for Small Modular Reactors – Safety Expectations, Prospects and Impediments of Their Deployment. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2015, 79, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.-D.; Khan, R. Techno-Economic Assessment of a Very Small Modular Reactor (vSMR): A Case Study for the LINE City in Saudi Arabia. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2023, 55, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, G.T. 14 - Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): The Case of the USA. In Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors; Carelli, M.D., Ingersoll, D.T., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing, 2015; pp. 353–377 ISBN 978-0-85709-851-1.

- Cho, E.; Lee, J. Social Acceptance of Small Modular Reactor (SMR): Evidence from a Contingent Valuation Study in South Korea. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2025, 57, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wu, G.; He, F.; Tong, J.; Zhang, L. Study on the Costs and Benefits of Establishing a Unified Regulatory Guidance for Emergency Preparedness of Small Modular Reactors in China. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2023, 161, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, E.; Clarno, K.; Haas, D.; Webber, M.E. The Economics of Small Modular Reactors at Coal Sites: A Program-Level Analysis within the State of Texas. Energy Policy 2025, 202, 114572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanatta, M.; Patel, D.; Allen, T.; Cooper, D.; Craig, M.T. Technoeconomic Analysis of Small Modular Reactors Decarbonizing Industrial Process Heat. Joule 2023, 7, 713–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T. 17 - Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): The Case of Japan. In Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors (Second Edition); Ingersoll, D.T., Carelli, M.D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing, 2014; pp. 409–424 ISBN 978-0-12-823916-2.

- Ayyildiz, E.; Yildirim, B.; Erdogan, M.; Aydin, N. Strategic Site Selection Methodology for Small Modular Reactors: A Case Study in Türkiye. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 215, 115545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X.; Han, D. Small Modular Reactors Enable the Transition to a Low-Carbon Power System across Canada. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 169, 112905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hee, N.; Peremans, H.; Nimmegeers, P. Economic Potential and Barriers of Small Modular Reactors in Europe. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 203, 114743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmastro, D.F. 14 - Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): The Case of Argentina. In Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors (Second Edition); Ingersoll, D.T., Carelli, M.D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing, 2021; pp. 359–373 ISBN 978-0-12-823916-2.

- Lim, S.G.; Nam, H.S.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, S.W. Design Characteristics of Nuclear Steam Supply System and Passive Safety System for Innovative Small Modular Reactor (i-SMR). Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2025, 57, 103697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, E.; Clarno, K.; Haas, D.; Webber, M.E. The Economics of Small Modular Reactors at Coal Sites: A Program-Level Analysis within the State of Texas. Energy Policy 2025, 202, 114572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, B.; Asad, A.; Krezan, L.; Yakout, M.; Hogan, J.D. A New Perspective on the Mechanical Behavior of Inconel 617 at Elevated Temperatures for Small Modular Reactors. Scripta Materialia 2025, 261, 116605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.; Liu, L.; Cao, J. Numerical Study of Forced Circulation and Natural Circulation Transition Characteristics of a Small Modular Reactor Equipped with Helical-Coiled Steam Generators. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2025, 183, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview of Small Modular and Advanced Nuclear Reactors and Their Role in the Energy Transition | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10841944 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Brown, N.R.; Worrall, A.; Todosow, M. Impact of Thermal Spectrum Small Modular Reactors on Performance of Once-through Nuclear Fuel Cycles with Low-Enriched Uranium. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2017, 101, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, N.A.Z.; Ismail, A.F.; Rabir, M.H.; Kok Siong, K. Neutronic Optimization of Thorium-Based Fuel Configurations for Minimizing Slightly Used Nuclear Fuel and Radiotoxicity in Small Modular Reactors. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2024, 56, 2641–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushamah, H.A.S.; Burian, O.; Ray, D.; Škoda, R. Integration of District Heating Systems with Small Modular Reactors and Organic Rankine Cycle Including Energy Storage: Design and Energy Management Optimization. Energy Conversion and Management 2024, 322, 119138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHart, M.D.; Karriem, Z.; Pope, M.A.; Johnson, M.P. Fuel Element Design and Analysis for Potential LEU Conversion of the Advanced Test Reactor. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2018, 104, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Kwon, O.-S.; Bentz, E.; Tcherner, J. Evaluation of CANDU NPP Containment Structure Subjected to Aging and Internal Pressure Increase. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2017, 314, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.G.; Wisudhaputra, A.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, K.; Park, H.-S.; Jeong, J.J. Development of a Special Thermal-Hydraulic Component Model for the Core Makeup Tank. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2022, 54, 1890–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishraq, Md.A.R.; Rohan, H.R.K.; Kruglikov, A.E. Neutronic Assessment and Optimization of ACP-100 Reactor Core Models to Achieve Unit Multiplication and Radial Power Peaking Factor. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2024, 205, 110588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.H.; Venneri, P.; Kim, Y.; Chang, S.H.; Jeong, Y.H. Preliminary Conceptual Design of a New Moderated Reactor Utilizing an LEU Fuel for Space Nuclear Thermal Propulsion. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2016, 91, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schickler, R.A.; Marcum, W.R.; Reese, S.R. Comparison of HEU and LEU Neutron Spectra in Irradiation Facilities at the Oregon State TRIGA® Reactor. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2013, 262, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposio, R.; Thorogood, G.; Czerwinski, K.; Rozenfeld, A. Development of LEU-Based Targets for Radiopharmaceutical Manufacturing: A Review. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2019, 148, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, S.; Baumeister, B.; Wight, J. Qualification of Advanced LEU Fuels for High-Power Research Reactor Conversion Designs. EPJ Nuclear Sci. Technol. 2025, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.; Miller, J.; Wu, Z. Implications of HALEU Fuel on the Design of SMRs and Micro-Reactors. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2022, 389, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, E.M.A. Emerging Small Modular Nuclear Power Reactors: A Critical Review. Physics Open 2020, 5, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Calculation of the Campaign of Reactor RITM-200 - IOPscience. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/1019/1/012057 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Swartz, M.M.; Byers, W.A.; Lojek, J.; Blunt, R. Westinghouse eVinciTM Heat Pipe Micro Reactor Technology Development.

- Wang, F.; Tian, Z.; Liu, J. Steady-State and Transient Analysis in Single-Phase Natural Circulation of ABV-6M.

- Zhou, Z.; Xie, J.; Deng, N.; Chen, P.; Wu, Z.; Yu, T. Effect of KLT-40S Fuel Assembly Design on Burnup Characteristics. Energies 2023, 16, 3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, B.A.; Kotlyar, D.; Parks, G.T.; Lillington, J.N.; Petrovic, B. Reactor Physics Modelling of Accident Tolerant Fuel for LWRs Using ANSWERS Codes. EPJ Nuclear Sci. Technol. 2016, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squarer, D.; Schulenberg, T.; Struwe, D.; Oka, Y.; Bittermann, D.; Aksan, N.; Maraczy, C.; Kyrki-Rajamäki, R.; Souyri, A.; Dumaz, P. High Performance Light Water Reactor. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2003, 221, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougar, H.D.; Petti, D.A.; Demkowicz, P.A.; Windes, W.E.; Strydom, G.; Kinsey, J.C.; Ortensi, J.; Plummer, M.; Skerjanc, W.; Williamson, R.L.; et al. The US Department of Energy’s High Temperature Reactor Research and Development Program – Progress as of 2019. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2020, 358, 110397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wu, F.; Ai, C.; Chen, C.; Wu, X.; Zhong, P.; Yan, J. Modeling and Analysis of Control Rod Drop in a Floating Nuclear Power Plant under Ocean Conditions. Ocean Engineering 2025, 338, 121992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, P.; Read, N. On the Practicalities of Producing a Nuclear Weapon Using High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2025, 215, 111235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.N.; Jo, C.K.; Kim, C.S. Conceptual Core Design and Neutronics Analysis for a Space Heat Pipe Reactor Using a Low Enriched Uranium Fuel. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2022, 387, 111603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, M.; Ansarifar, G.R.; Yeganeh, M.H.Z. Assessment and Predicting the Effect of Accident Tolerant Fuel Composition and Geometry on Neutronic and Safety Parameters in Small Modular Reactors via Artificial Neural Network and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2025, 433, 113837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, N.; Raffuzzi, V. Neutronic Analysis of High Burnup Thorium-HALEU Fuels in PHWR. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2024, 422, 113113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari-Jeyhouni, R.; Rezaei Ochbelagh, D.; Maiorino, J.R.; D’Auria, F.; Stefani, G.L. de The Utilization of Thorium in Small Modular Reactors – Part I: Neutronic Assessment. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2018, 120, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatullah, A.; Permana, S.; Irwanto, D.; Aimon, A.H. Comparative Analysis on Small Modular Reactor (SMR) with Uranium and Thorium Fuel Cycle. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2024, 418, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, R.; Aghili Nasr, M.; D’Auria, F.; Cammi, A.; Maiorino, J.R.; de Stefani, G.L. Analysis of Thorium-Transuranic Fuel Deployment in a LW-SMR: A Solution toward Sustainable Fuel Supply for the Future Plants. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2024, 421, 113090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. Small Modular Reactors and the Future of Nuclear Power in the United States. Energy Research & Social Science 2014, 3, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwijayanto, R.A.P.; Miftasani, F.; Harto, A.W. Assessing the Benefit of Thorium Fuel in a Once through Molten Salt Reactor. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2024, 176, 105369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, M.H.; Van Niekerk, F.; Amirkhosravi, S. Review of Thorium-Containing Fuels in LWRs. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2024, 170, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsige-Tamirat, H. Neutronics Assessment of the Use of Thorium Fuels in Current Pressurized Water Reactors. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2011, 53, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ault, T.; Krahn, S.; Croff, A. Thorium Fuel Cycle Research and Literature: Trends and Insights from Eight Decades of Diverse Projects and Evolving Priorities. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2017, 110, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldova, D.; Fridman, E.; Shwageraus, E. High Conversion Th–U233 Fuel for Current Generation of PWRs: Part II – 3D Full Core Analysis. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2014, 73, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatullah, A.; Permana, S.; Irwanto, D.; Aimon, A.H. Comparative Analysis on Small Modular Reactor (SMR) with Uranium and Thorium Fuel Cycle. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2024, 418, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, T.; Feng, B.; Heidet, F. Molten Salt Reactor Core Simulation with PROTEUS. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2020, 140, 107099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, P.K.; Shivakumar, V.; Basu, S.; Sinha, R.K. Role of Thorium in the Indian Nuclear Power Programme. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2017, 101, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, T.; Feng, B.; Heidet, F. Molten Salt Reactor Core Simulation with PROTEUS. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2020, 140, 107099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dawood, K.; Palmtag, S. METAL: Methodology for Liquid Metal Fast Reactor Core Economic Design and Fuel Loading Pattern Optimization. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2024, 173, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.C.; Porter, D.L. Applying U. S. Metal Fuel Experience to New Fuel Designs for Fast Reactors. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2024, 171, 105135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Genk, M.S.; Schriener, T.M. Post-Operation Radiological Source Term and Dose Rate Estimates for the Scalable LIquid Metal-Cooled Small Modular Reactor. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2018, 115, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.I. Review of Small Modular Reactors: Challenges in Safety and Economy to Success. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 2761–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Lee, Y.; Kim, N.; Jo, H. Design of Heat Pipe Cooled Microreactor Based on Cycle Analysis and Evaluation of Applicability for Remote Regions. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 288, 117126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.H.; Hong, S.G. Neutronic Analysis on TRU Multi-Recycling in PWR-Based SMR Core Loaded with MOX (U-TRU) and FCM (TRU) Fueled Assemblies. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2022, 179, 109435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schønfeldt, T.; Klinkby, E.; Schofield, A.V.; Pettersen, E.E.; Puente-Espel, F. Chapter 24 - Seaborg Technologies ApS—Compact Molten Salt Reactor Power Barge. In Molten Salt Reactors and Thorium Energy (Second Edition); Dolan, T.J., Pázsit, I., Rykhlevskii, A., Yoshioka, R., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing, 2024; pp. 907–918 ISBN 978-0-323-99355-5.

- Mishra, V.; Branger, E.; Grape, S.; Elter, Z.; Mirmiran, S. Material Attractiveness of Irradiated Fuel Salts from the Seaborg Compact Molten Salt Reactor. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2024, 56, 3969–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuler, S.P.; Webler, T. The Challenge of Community Acceptance of Small Nuclear Reactors. Energy Research & Social Science 2024, 118, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Stable Salt Reactor—A Radically Simpler Option for Use of Molten Salt Fuel | SpringerLink. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-13-2658-5_37 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Gonçalves, N.; Silva, C.A.M.; Lorduy-Alós, M.; Gallardo, S.; Pereira, C.; Verdú, G. Neutronic Assessment of Stable Salt Reactor with Reprocessed Fuels. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2025, 218, 111383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnag, M.; Oh, T.; Kim, Y. A Neutronic Study on Safety Characteristics of Fast Spectrum Stable Salt Reactor (SSR). In Proceedings of the Challenges and Recent Advancements in Nuclear Energy Systems; Shams, A., Al-Athel, K., Tiselj, I., Pautz, A., Kwiatkowski, T., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 600–611. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, N.; Silva, C.A.M.; Lorduy-Alós, M.; Gallardo, S.; Pereira, C.; Verdú, G. Neutronic Assessment of Stable Salt Reactor with Reprocessed Fuels. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2025, 218, 111383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Brown, N.R. Potential Fuel Cycle Performance of Floating Small Modular Light Water Reactors of Russian Origin. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2020, 144, 107555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, I.J.; Bang, I.C. The Time for Revolutionizing Small Modular Reactors: Cost Reduction Strategies from Innovations in Operation and Maintenance. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2024, 174, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, E.; Clarno, K.; Haas, D.; Webber, M.E. The Economics of Small Modular Reactors at Coal Sites: A Program-Level Analysis within the State of Texas. Energy Policy 2025, 202, 114572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).