1. Introduction

Tubulin is one of the major structural proteins that exists either as in free form or as microtubules.[

1] Morphologically, tubulin exists in two major isoforms, α- and β-tubulin.[

2] These isoforms of tubulin polymerise in a head-to-tail fashion to form protofilaments. The formed protofilaments, when reach thirteen in number, further polymerise to cylindrical structures called ‘microtubules’.[

3,

4] These microtubules thus formed have a positive and negative end, wherein the positive end exposes the β form of tubulin while the negative end comprises α-tubulin.[

5] These microtubules, so formed, have unique characteristics, termed as ‘exquisite dynamic behavior’ that is associated with the polymerization and depolymerization of the microtubules or the tubulin units.[

6] This is vital in maintaining the cell shape and assists in the process of cell division, particularly karyokinesis, where it is involved in the formation of the mitotic spindle. Tubulin protein has cytoskeleton and mitotic spindle-forming properties that are essential for cellular transport and division. This dynamic behaviour is catalysed by the guanosine triphosphate (GTP) hydrolysis, followed by the guanosine diphosphate GDP/GTP exchange cycles. The GTP bound to the α-tubulin subunit is referred to as ‘N-site’ while the GTP bound to the β-tubulin is called ‘E-site’.[

7] Among these two sites, the N site is stable and does not undergo hydrolysis or the exchange cycle, whereas the E site is unstable and undergoes hydrolysis and exchange with free GDP.[

8,

9] Thus, considering this, the N-site (GTP bound) promotes the growth of microtubules, and the E-site (GDP bound) does not undergo polymerization. Any hindrance or negative signaling in the N-site (also referred to as the GTP-bound tubulin cap) allows the microtubules to enter the depolymerization phase. The brief illustration of this dynamicity and outcome is reflected in

Figure 1.

In cancer cells, which are metabolically more active, this dynamicity is lost owing to the elevated expression and functioning of microtubules.[

10,

11] These lead to uncontrolled cancer cell proliferation, evading controlled cell cycle checks, survival, and resistance to existing cancer chemotherapy.[

12] Considering that tubulin and microtubules are considered one of the major anticancer drug targets. To control the unrestrained dynamicity of the microtubules, numerous inhibitor classes for microtubules have been proposed. The agents targeting the microtubules and involved in altering the dynamicity are called microtubule-targeting agents (MTAs). These agents are further subclassified into three groups: (

i) microtubule-stabilizing agents (MSAs), which promote polymerization stabilization. MSAs act towards taxanes and laulimalide/peloruside-A binding site.[

13] Key inhibitors include Paclitaxel, Docetaxel, Epothilones including Ixabepilone, Patupilone, Laulimalide, and Peloruside; (

ii) microtubule-destabilizing agents (MDAs) are associated with the polymerization inhibition and promote depolymerization.[

14] MDAs interact with the five distinct binding sites, including the vinca domain, the colchicine domain, the pironetin site, the maytansine site, and the most recently discovered seventh site, known as the gatorbulin-1 site.[

5,

15] This site represents a dual behavior (MTs destabilizing or tubulin degraders) depending on the compounds binding to it. To exemplify, cevipabulin binds to the vinca site as a microtubule destabilizer and to the seventh site as a tubulin degrader.[

16] The key drugs in this category include vinblastine, colchicine, nocodazole, tivantinib, pironetin, maytansine, gatorbulin-1 (GB1), cevipabulin (also known as TTI-237), and (

iii) microtubule-targeting degraders (MTGs), which are associated with the microtubule denaturation leading to its degradation.[

17] The drugs in this category include withaferin-A,[

18] T0070907,[

5] 3-(3-phenoxybenzyl)amino-β-carboline(PAC),[

5] and cevipabulin, [

19]which exhibit tubulin-degrading properties. 2D chemical structures of these inhibitors are presented in

Figure 2A.

All these drugs, though have different mechanisms, lead to cancer cell death by causing microtubule abnormalities and affecting the cell cycle. The reported molecules are known to bind to seven distinct druggable sites (

Figure 2B) present in microtubules.[

5] This includes the major sites: taxane (paclitaxel and docetaxel), vinca (vinca alkaloids such as vincristine and vinblastine), and colchicine binding site (colchicine and combretastatin A-4), and lesser-explored sites that include maytansine, peloruside-A (laulimalide), and gatorbulin site.[

20,

21] Among these reported sites, the colchicine binding site (CBS) was the first site identified in the tubulin that was explored both for cancer and non-cancer diseases and disorders.[

15,

22,

23] This site is also important because the inhibitors binding to this site have unique mechanisms that inhibit the tubulin assembly

. Furthermore, it possesses a deep hydrophobic pocket located at the interface of α- and β-tubulin and making it a favorable druggable site for small molecules binding

.[

24,

25,

26] Unlike taxane and vinca sites, CBS inhibitors acts on rapidly dividing cancer cells

. The CBS moreover involves unique mechanism of inhibiting polymerization, thus overcoming resistance mechanisms associated with β-tubulin overexpression or drug efflux mediated by the P-glycoprotein. In addition to the anticancer effect, the inhibition of CBS site is also associated with anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic properties that further synergizes the anticancer effects.[

27,

28]

As the majority of inhibitors are phytochemicals or semisynthetic derivatives, they are associated with poor pharmacokinetics and toxicities that hamper their clinical use.[

12,

16] While the research is ongoing to identify and develop safer and more effective molecules targeting CBS, the rapidly growing cancer cases globally demand rapid drug discovery. Cancer evolves more rapidly owing to drug resistance, inadequate pharmacokinetics, and toxicities of existing chemotherapeutic agents.[

4,

29] This puts a global burden on the pace of current anticancer discovery and raises a quest for the utmost need for drug discovery and anticancer drug development. One of the rapid and recommended ways for drug discovery is drug repurposing or repositioning.[

30] Traditional approaches in developing novel drugs are limited by high cost and time, and have been largely surpassed by designing some efficient computational workflows for drug design, including structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD),[

31] considering in silico drug repurposing. The main advantage of the in-silico drug design is to implement the drug discovery research projects to discover new compounds with the potential to be transformed into new therapeutic agents in less time and at a lower cost than the traditional drug discovery approach. There are several significant methods in the in-silico drug design approach, including homology modelling, molecular docking, high-throughput virtual screening, quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), 3D pharmacophore mapping, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [

15,

32]. Moreover, recent integration of artificial intelligence (AI)[

33] and machine learning (ML) [

34] in these workflows have significantly accelerated the drug discovery pipeline. By leveraging vast commercially available huge chemical libraries and screening large number of molecules virtually, AI and ML allow exploration of chemical space at a scale and speed, outperforming traditional experimental approaches.[

35]

To achieve plausible CBS inhibitors with anticancer potential, we performed an ML-driven computational drug repurposing study, using 4500 USFDA-approved drugs.[

36] The ML workflow was combined with the computer-assisted drug design (CADD) strategy to identify promising tubulin inhibitors with anticancer activities. Structure-based drug design refinements such as molecular docking, MM-GBSA binding free energy calculations, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations allowed us to identify three promising hit molecules, i.e., podofilox, omeprazole, and sulfadoxine, which inhibit the CBS site of tubulin and could be further developed as anticancer agents. The identified hits were biologically corroborated by performing a tubulin polymerization assay, understanding the cytoskeletal disruption, and their anticancer potential was established in a panel of cancer cell lines, and the impact on cell cycle analysis and apoptosis was assessed.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Machine Learning Model Development

The AutoQSAR-based machine learning workflow[

41] in Maestro, Schrödinger[

39] was employed to develop predictive classification models for tubulin inhibitors. The curated dataset consisted of 279 compounds with experimentally determined pIC₅₀ values, categorized as actives (pIC₅₀ ≥ 5.5) and inactives (pIC₅₀ ≤ 4.9). An independent external validation set comprising 157 decoy compounds (pIC₅₀ ≤ 4.9) was reserved exclusively for final model testing. By default, AutoQSAR utilizes a comprehensive set of descriptors, including binary fingerprints (radial, linear, dendritic, and molprint2D) as well as numerical descriptors, including topographical, physicochemical, and Ligfilter properties.

Multiple models were generated using different algorithm–descriptor combinations. Among these, Bayesian classification (Bayes) and Recursive Partitioning (RP) models consistently achieved top ranks. In particular, Bayes models employing dendritic and linear fingerprints (i.e., bayes_dendritic_1 with a model score of 0.9389, and bayes_linear_20 with a 0.9337 model score) displayed the highest internal validation scores, with strong R² and Q² values, low RMSE, and balanced classification metrics, as mentioned in

Table 1. RP models such as rp_30 and rp_41 also performed competitively, demonstrating robust predictive ability across the descriptor set, showing model scores of 0.9158 and 0.9133, respectively.

The model score is a composite metric that combines multiple measures of model quality into a single value between 0 and 1, facilitating the direct comparison of models built using different descriptor sets and algorithms. For classification tasks, the score integrates internal cross-validated accuracy, area under the ROC curve (AUC), enrichment factors, and class-specific error rates, with greater weight given to predictive power and robustness across validation folds. For regression tasks, the score combines the coefficient of determination (R²), cross-validated coefficient (Q²), root-mean-square error (RMSE), and error consistency. Each metric is normalized and weighted before aggregation, ensuring that the final model score reflects both predictive accuracy and stability rather than a single performance statistic. The performance of the best individual ML model, each from Bayes classification and recursive partitioning is enlisted in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively, as well as discussed below.

Bayesian classification is a probabilistic approach grounded in Bayes’ theorem, estimating the posterior probability of class membership given the observed descriptors. AutoQSAR’s Bayes implementation assumes conditional independence among descriptors, which allows efficient handling of high-dimensional feature spaces. In this study, Bayes models integrated both structural fingerprints and numerical descriptors, facilitating the capture of chemical substructure patterns along with the physicochemical properties. The algorithm outputs a probability score for each class (active or inactive), with final classification determined by the higher posterior probability. The robustness of this method with respect to diverse data and the ability to generalize from limited samples make it particularly well-suited for virtual screening tasks involving structurally diverse datasets.

Recursive Partitioning is a decision-tree-based algorithm that sequentially divides the dataset into progressively purer subsets according to descriptor thresholds that maximize class separation. Each split is determined by the descriptor value that generates a significant improvement in classification purity, and this process continues until stopping criteria are met. The resulting model can be visualized as a hierarchy of decision rules, making RP inherently interpretable. Its capacity to handle complex, non-linear interactions among descriptors is advantageous for modeling structure – activity relationships in datasets where multiple features collectively influence biological activity.

Internal evaluation was performed using a stratified 75:25 train–test split of the inhibitor dataset, with AutoQSAR applying k-fold cross-validation to the training set for hyperparameter tuning. The internal test results indicated strong generalization within the chemical space represented in the training data, with no signs of overfitting. External validation against the 157 decoy compounds demonstrated high specificity, indicating the models’ ability to accurately recognize inactive compounds and minimize false positives—an essential criterion for virtual screening workflows.

Based on combined internal and external validation metrics, we adapted a consensus strategy for predicting the hit molecules, binding at the CBS of the tubulin, further showing tubulin inhibitor and anticancer activities. Consensus model resulting from the top 10 ML models discussed above was used to screen FDA-approved library of 4500 compounds.

3.2. Molecular Docking

After the ML model development and validation, a consensus strategy was used to consider all the top 10 models and identify new tubulin inhibitors. A chemical library comprising 4500 USFDA approved drugs were predicted through the consensus ML model approach, to identify new compounds. Out of the 4500 FDA approved compounds, X compounds predicted to be ‘active’ against tubulin protein, based on possessing similar structural and molecular properties to that of existing tubulin inhibitors, used in ML training. Before performing structure-based virtual screening operation, we first retrieved and interrogated the X-ray structure of tubulin protein bound to a nanomolar potent inhibitor G8K (PDB code: 6O5M)

(Figure 3). The binding mode of the co-crystallized ligand G8K (

Figure 4) indicates that it forms water bridge/salt bridge interactions with the Arg 198, Lys 350, i.e., positively charged residues, followed by carbonyl oxygen interactions with Asn112 and Ser132, forming the H-bond. His 114 was also found to participate in an H-bond with the Aza group in the co-crystallised ligand. The aromatic ring systems were found to stabilise the molecule via π–π stacking with Phe169 and Tyr203. Additional interaction with Thr179 and Asn347 in the colchicine binding site highlighted G8K is maintaining interactions with both Further, oxygen and hydrogen atoms of water molecule forms hydrogen bond interactions with the amine hydrogen of the Cys239 and carbonyl oxygen of Gly235 helping towards the binding of G8K with the chain B. Thereby, four amino acid residues Thr179, Asn347, Cys239, and Gly235 contribute substantially towards the ligand interaction within the substrate binding site.

After studying the interactions and the binding mode of the co-crystallized inhibitor G8K at the tubulin binding site, the next step was to select and validate the docking program for our structure-based virtual screening study. The validation of docking was done by redocking the co-crystallised ligand within the same binding site (CBS) of tubulin, As shown in

Figure 5, the Glide SP docking poses results in a perfect superposition to that of the co-crystallized pose, possessing an RMSD of 1.18 Å, confirming the reliability of our docking method to be used in the next steps.

As illustrated in the virtual screening workflow diagram in

Figure 6, ~1800 compounds were subjected to three stages of docking using the Glide program of Schrödinger: (a) Glide HTVS, (b) Glide SP, and (c) Glide SP to refine the virtual screening workflow and prioritize promising compounds. Glide HTVS docking mode allowed prioritization of 698 compounds among 1800 compounds, possessing docking scores of 9.0 kcal/mol and above. Similarly, the 698 filtered compounds were further docked through the Glide SP docking mode, leading to 350 compounds with docking scores of 9.0 kcal/mol and above. The last stage of docking protocol involved the use of Glide XP mode, which facilitated the refinement of the best 38 compounds showing docking scores of 8.0 kcal/mol and above.

In general, the Glide Score provides an empirical and approximate scoring function, irrespective of providing any information on the actual free energy change. Owing to this, the docking scores often fail to portray the full complexity of molecular interactions. To overcome this, we additionally performed the molecular mechanics (MMGBSA) to calculate the ΔG_bind and ΔG_coulomb, which indicate the estimation of the binding free energy and the accompanying electrostatic interactions between the ligand and the target protein. These parameters provide much more accuracy and full complexity of molecular interactions of the ligand within the binding site. Together, these thermodynamic parameters portray much realistic and refined predictions and provide a true estimation of binding affinity. The Glide XP docking scores of the most promising compounds along with their binding energetics illustrated in

Table 4, also compared with the reference co-crystallized inhibitor G8K.

The said analysis revealed that Arformoterol, though it had an excellent docking score, had a poor ΔG_bind, suggestive of a potential outlier. Coming to the potent molecules, Omeprazole exhibited a strong binding (-64.16 kcal/mol), and a moderate electrostatic potential (-58.31 kcal/mol) along with a moderate Glide Score. Podofilox was found to be a perfect solid all-rounder, portraying optimal docking and binding scores of -9.908 kcal/mol and -38.61 kcal/mol, respectively. Thus, based on analysis, we selected podofilox, omeprazole, and sulfadoxine for our further analysis.

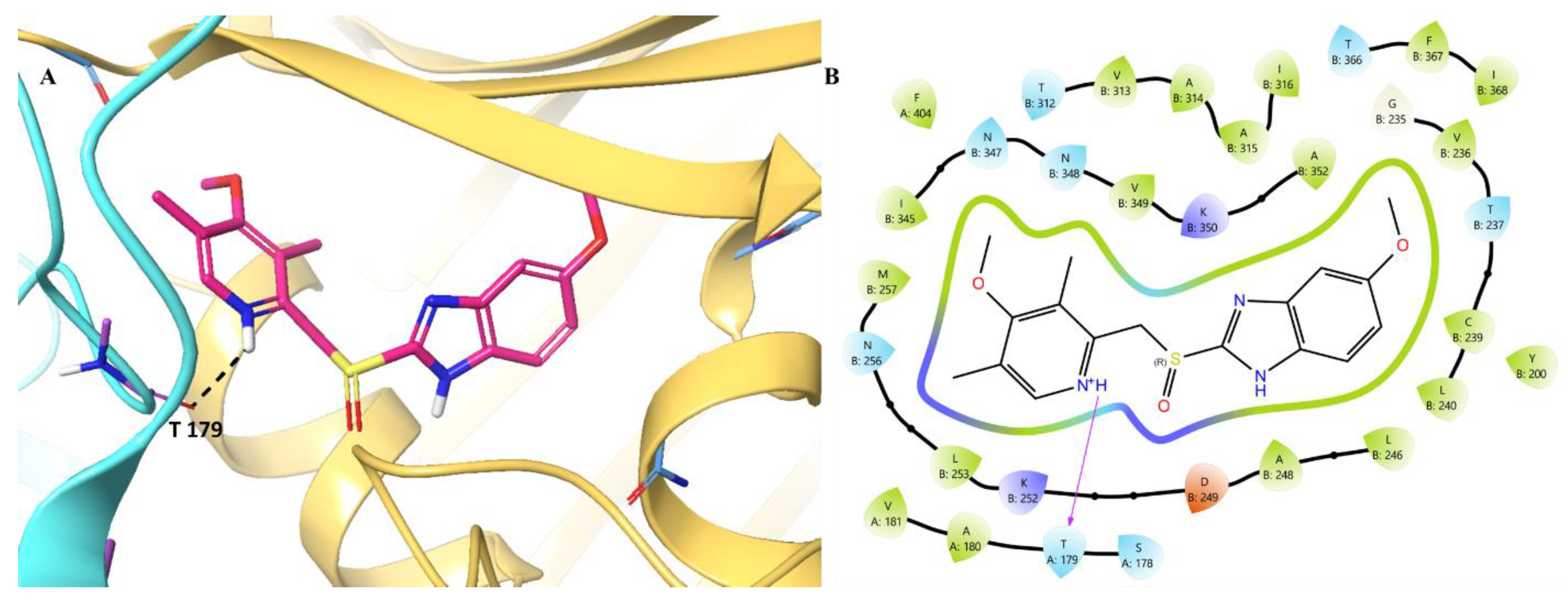

Initially, we analyzed the binding pattern of the selected compounds with the CBS. We analysed the podofilox binding pattern, the analysis revealed

(Figure 7) that the compound engages the CBS site primarily via the hydrogen bonding with Thr179 (A179). The water molecule present was further found to stabilise the interaction via the hydration network mediated with the involvement of Gly235, Val236, Thr237, and Ile368. Hydrogen bonds between the hydrogen atom of the water molecule and the oxygens of the trimethoxyphenyl group of podofilox help its binding with the water molecule. Further, oxygen and hydrogen atoms of the water molecule form hydrogen bond interactions with the amine hydrogen of Cys239 and the carbonyl oxygen of Gly235, helping towards the binding of podofilox with chain B. Additionally, the hydrophobic enclosure made by amino acid residues, primarily Leu253, Ala248, and Ile316, was also found to be important in stabilising the interaction. The negatively charged Asp249 was also found to provide podofilox optimal electrostatic binding (ΔG_coloumb). Podofilox was shown to portray its binding within the CBS cavity via the extensive water network, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bonding interactions.

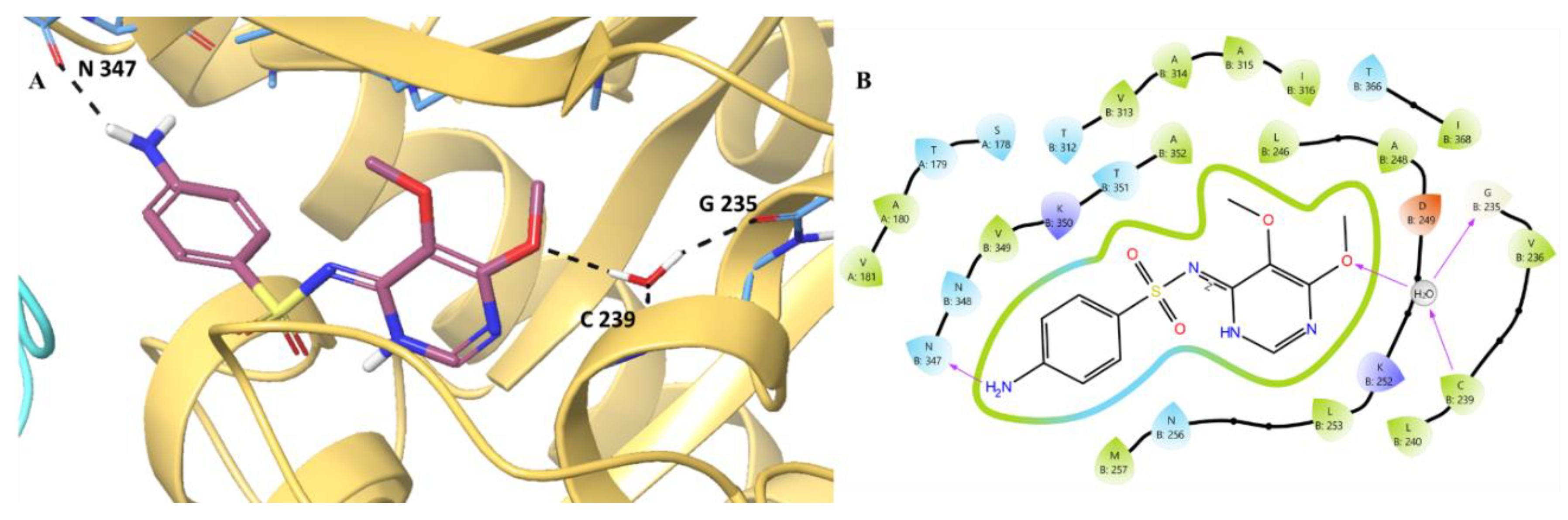

Next, we analysed the binding pattern of Omeprazole. The analysis revealed

(Figure 8) shows one interaction with the hydroxy group of Thr179 with the protonated nitrogen (N⁺H) of omeprazole. The omeprazole is further found to be stabilised by the hydrophobic amino acid residues such as Val181 (A181), Ala180 (A180), Leu253 (B253) and hydrophilic interaction mediated by the polar residues such as Thr312 (B312), Asn347 (B347) and Asn348 (B348), offering stabilization via the dipole-diploe interactions and hydrogen bonding mediated by the water molecule. In addition to this, charged residues Lys350 and Asp249 further contributed to the electrostatic stabilization. although no direct salt bridges are depicted. Furthermore, aromatic amino acid residues (Phe367 and Phe404) hover the binding cavity, raising the possibility of π-π interactions.

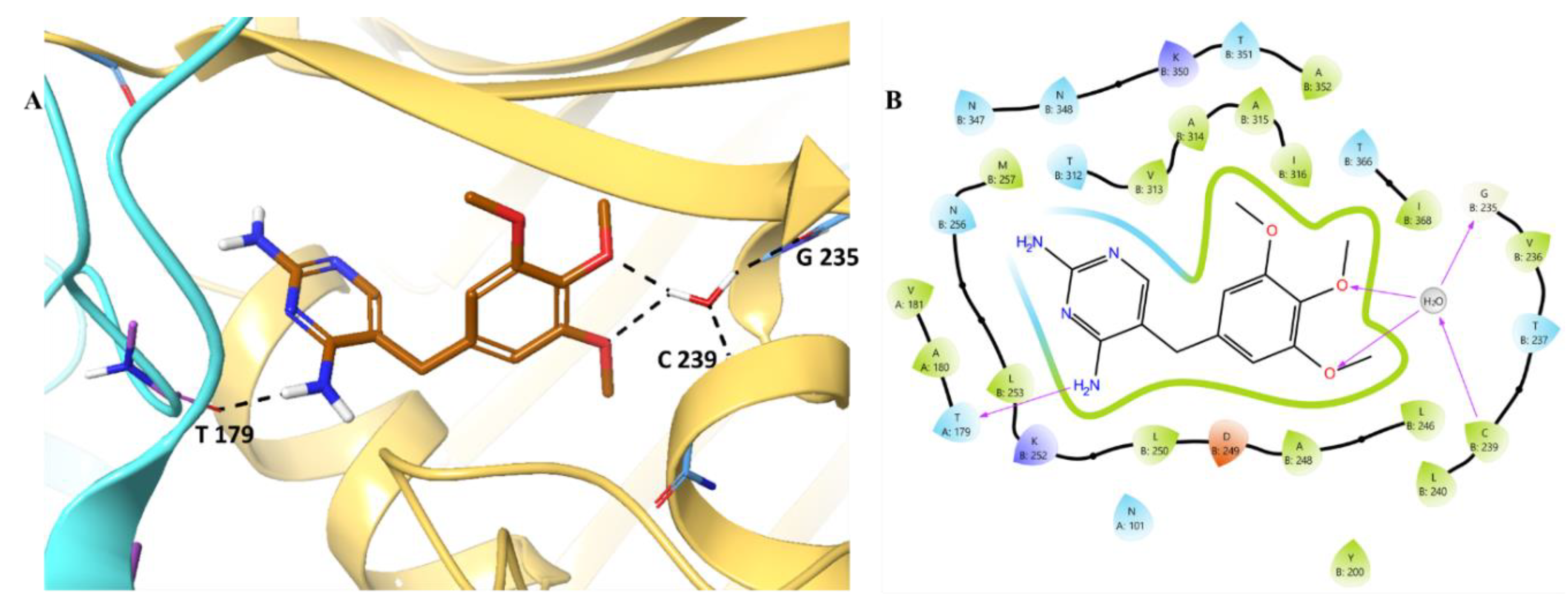

We analyzed the binding pattern of sulfadoxine. The analysis revealed

(Figure 9) multiple hydrogen bonds, notably with Asn347, Gly235, and Cys239. Additionally, the electrostatic stability was provided by the Asp249 (B:249) and Lys252 and Lys350 based charged residues. Along with this, a water-mediated hydrogen bond was also found to stabilise the ligand in the CBS. The hydrogen bond between the hydrogen atom of the water molecule and the oxygen of the trimethoxyphenyl group of sulfadoxine helps its binding with the water molecule. Further, oxygen and hydrogen atoms of the water molecule form hydrogen bond interactions with the amine hydrogen of Cys239 and the carbonyl oxygen of Gly235, which also helped towards the binding of sulfadoxine with the chain B. Thereby, three amino acid residues, Asn347, Gly235, and Cys239, contribute significantly towards the ligand interaction within the substrate binding site.

Lastly, the suggested binding mode of the docked compound trimethoprim from the docking studies (

Figure 10) shows THR179 (T179) is associated with the formation of a hydrogen bond with TMP water-mediated interaction and another interaction with Thr179 in the colchicine binding site. This allows trimethoprim to maintain interactions with both chain A and chain B of the tubulin heterodimer, thus allowing it a strong binding affinity towards the CBS embedded at the interface of both chains. One other water-mediated interaction was observed by the docking studies in which a water molecule exists as an intermediate, helping towards the binding of trimethoprim with the Gly235 and Cys239 of chain B. The Cys239 contributed to the hydrophobic interactions and was involved in stabilisation via van der Waals forces, while Gly235 formed another bond with the TMP. Thus, three amino acid residues Thr179, Gly235, and Cys239 contribute significantly towards the ligand interaction within the substrate binding site. Besides the hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic enclosure formed via Ala248, Leu 253, and Ile368, and aromatic stabilisation via π-π stacking also played a major role. In a nutshell, the conformation pattern of TMP revealed that it sits deeply embedded in CBS, stabilized primarily by the polar and hydrogen bonding interactions.

3.3. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

From the cumulative molecular docking and MMGBSA analysis, we concluded podofilox, omeprazole, and sulfadoxine to be the best possible hits. However, the molecular docking analysis assumes the protein to be in a rigid state, undergoing no conformation changes, while the molecular mechanics studies provide an idea of an approximate estimation of the binding energy, which, however, does not take into account the excess water and or solvent residues in the binding site. To overcome this research gap, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are recommended, which take into account the stability of protein–ligand complex over time when both are in perturbations and have constant fluctuation in the conformations. The MD poses thus assist in confirming whether the binding pose is stable over the simulation period or the binding pose revealed through the docking study was unrealistic, and if there was a transitory protein-ligand binding. To study this, we performed the MD simulations of 200 ns on the top hit identified ligands from the pool.

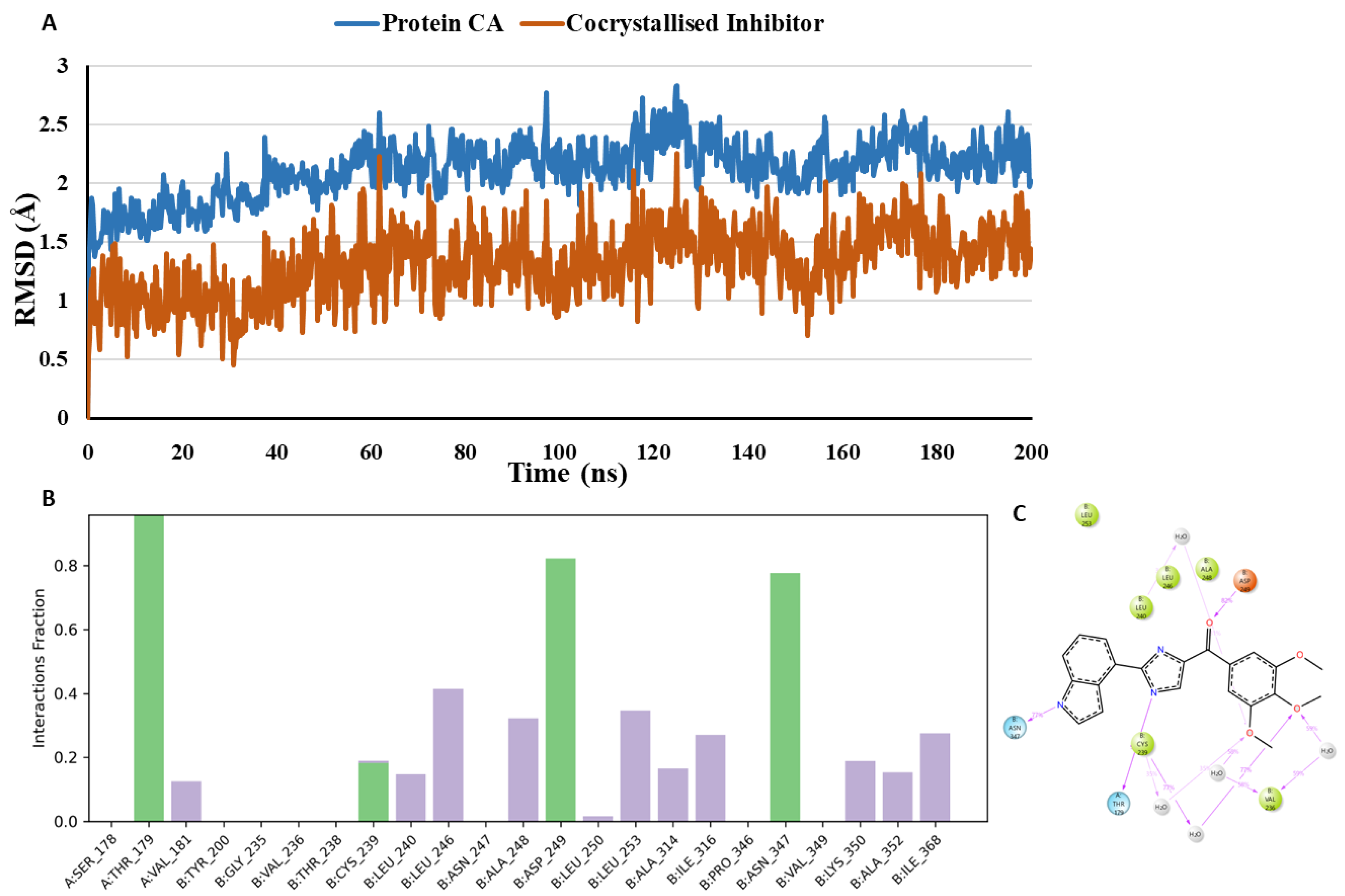

To analyse the conformational dynamicity of the receptor and ligand, the co-crystallized inhibitor, and the docked compounds podofilox, omeprazole, and sulfadoxine were subjected to 200 ns MD simulations, starting from their initial co-crystallized/Glide XP docking poses. During the simulation trajectory, the deviation of the protein and ligand atoms from their initial crystallographic poses is illustrated by the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and it was calculated for the α-carbons of protein and the ligand heavy atoms throughout the simulation. RMSD plot

(Figure 11) demonstrates that the co-crystallized inhibitor and the protein exhibit stability over the course of the simulation. The co-crystallised inhibitor, G8K is maintaining an average RMSD of 1.31 Å during the simulation in the tubulin binding site. The suggested binding mode of the G8K from the docking studies represents one hydrogen-bonded protein-ligand interaction mediated by a water molecule and other interactions with Thr179 (Chain A) and Asn347 (Chain B) in the colchicine binding site. Moreover, it was revealed by MD studies that H-bond interactions with the Thr179 (Chain A), Cys239 (Chain B) and Asn347 (Chain B) was maintained during 96.1%, 17.7% and 77.7% of the simulation time. Furthermore, MD studies demonstrated the presence of an additional H-bond interaction between G8K and Asp249 (Chain B). Although this interaction was not visible in the crystallographic binding pose, yet it was observed during 82.4% of the simulation time.

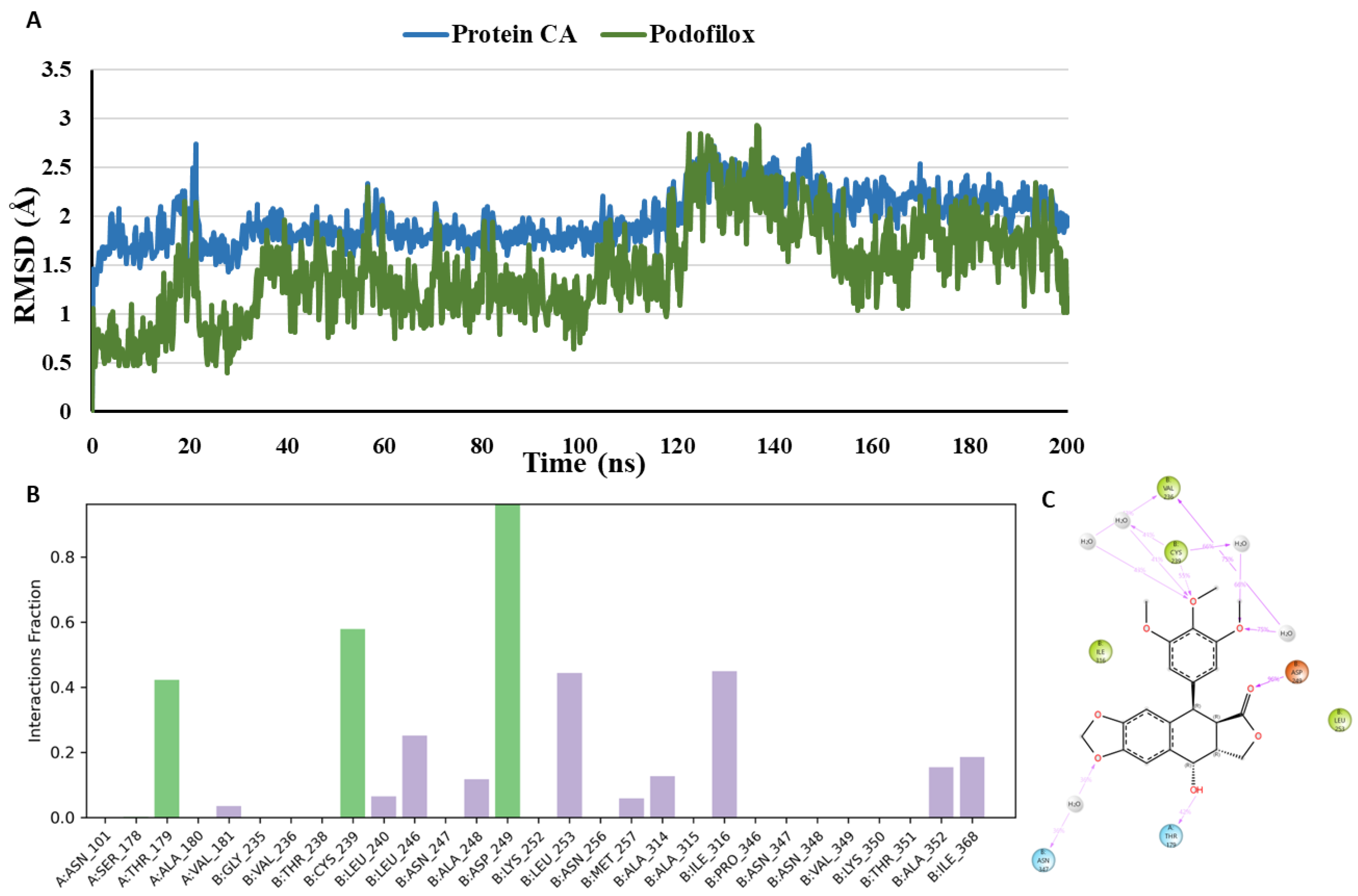

The suggested binding mode of the compound podofilox from the docking studies shows one hydrogen-bonded protein-ligand interaction mediated by a water molecule and another interaction with Thr179 (Chain A) in the colchicine binding site. Moreover, it was revealed by MD studies that H-bond interactions with the Thr179 (Chain A) and Cys239 (Chain B) was maintained during 42.3% and 56.4% of the simulation time. Furthermore, MD studies demonstrated the presence of an additional H-bond interaction between the docked compound podofilox and amine hydrogen of Asp249 (Chain B). Although this interaction was not seen in the crystallographic binding pose, yet it was observed during 96.5% of the simulation time. Additionally, we observed that in the crystallographic pose, podofilox interacts with Cys239 (Chain B) by forming hydrogen bond with the amine hydrogen of Cys239 (Chain B) while it interacts with the Cys239 (Chain B) by forming hydrogen bond with the thiol hydrogen as revealed by MD studies. RMSD plot

(Figure 12) demonstrates that podofilox and the protein exhibit stability over the course of the simulation, but some fluctuations were observed in between 20-23 ns and 125-150 ns indicating that the podofilox is undergoing some major conformational changes and becoming more flexible in the CBS. Thr179 (Chain A), Cys239 (Chain B) and Asp249 (Chain B) are the common amino acid residues forming H-bond interactions with both co-crystallized inhibitor and podofilox. With podofilox, Thr179 (Chain A) was observed maintaining a low percentage of 42.3% as compared to the co-crystallized inhibitor maintaining this interaction during 96.1% of the simulation time. Furthermore, the H-bond interactions between podofilox and amino acid residues, Cys239 (Chain B) and Asp249 (Chain B) was observed maintaining a high percentage of 56.4% and 96.5% as compared to the co-crystallized inhibitor maintaining this interaction during 17.7% and 82.4% of the simulation time.

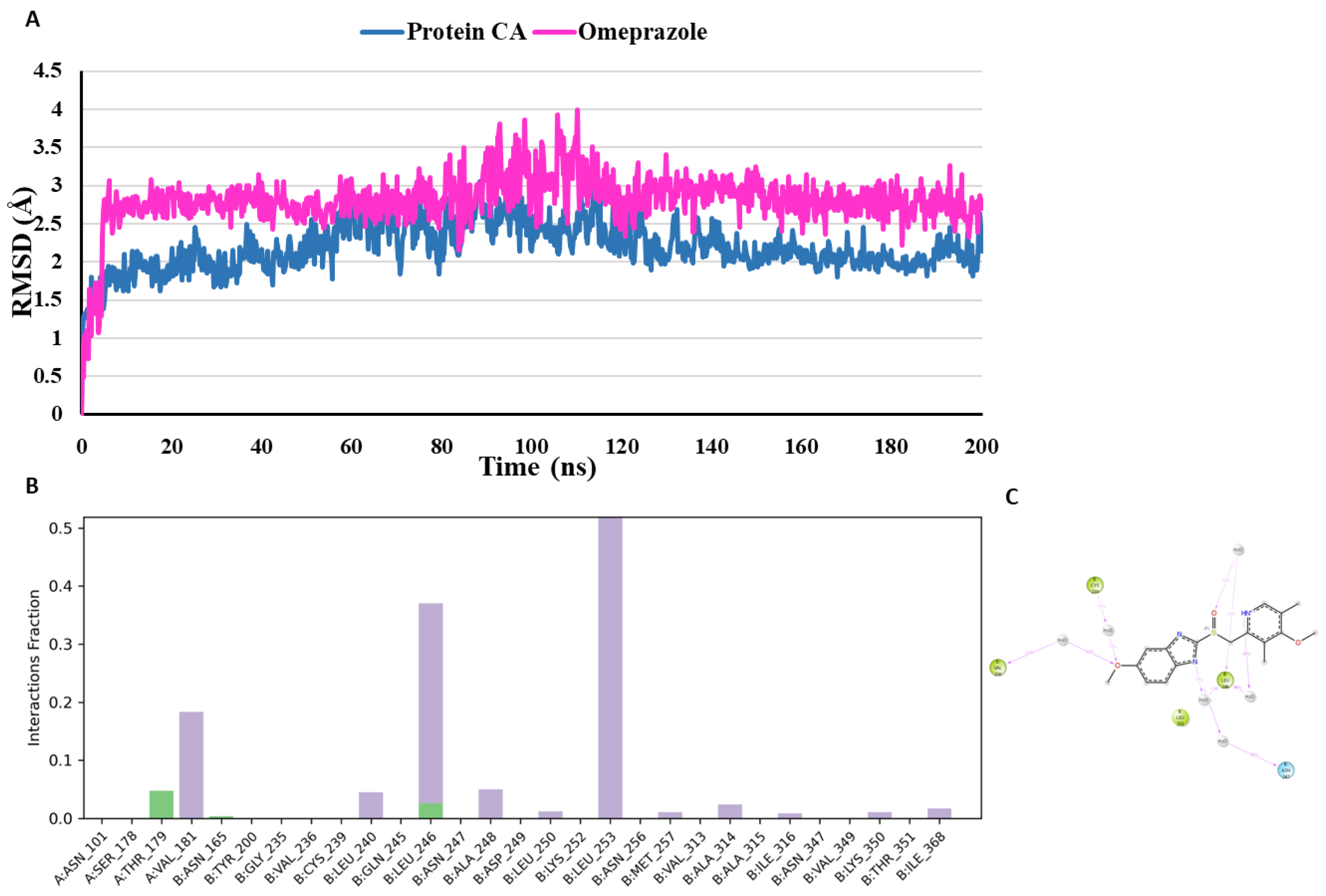

The suggested binding mode of the compound omeprazole from the docking studies shows one interaction with Thr179 (Chain A) in the colchicine binding site. Moreover, it was revealed by MD studies that H-bond interactions with the Thr179 (Chain A) was maintained during 4.8% of the simulation time. Furthermore, MD studies demonstrated the presence of two additional H-bond interactions between the docked compound omeprazole and amino acid residues Asn165 (Chain B) and Leu246 (Chain B). Although theses interactions were not seen in the crystallographic binding pose, yet they were observed during 1% and 2.6% of the simulation time. RMSD plot

(Figure 13) demonstrates that omeprazole and the protein exhibit stability over the course of the simulation suggesting that it is not undergoing any major conformational changes representing its stability and favourable binding affinity towards the CBS. Thr179 (Chain A) is the common amino acid residues forming H-bond interactions with both co-crystallized inhibitor and omeprazole. With omeprazole, Thr179 (Chain A) was observed maintaining a low percentage of 4.8% as compared to the co-crystallized inhibitor maintaining this interaction during 96.1% of the simulation time.

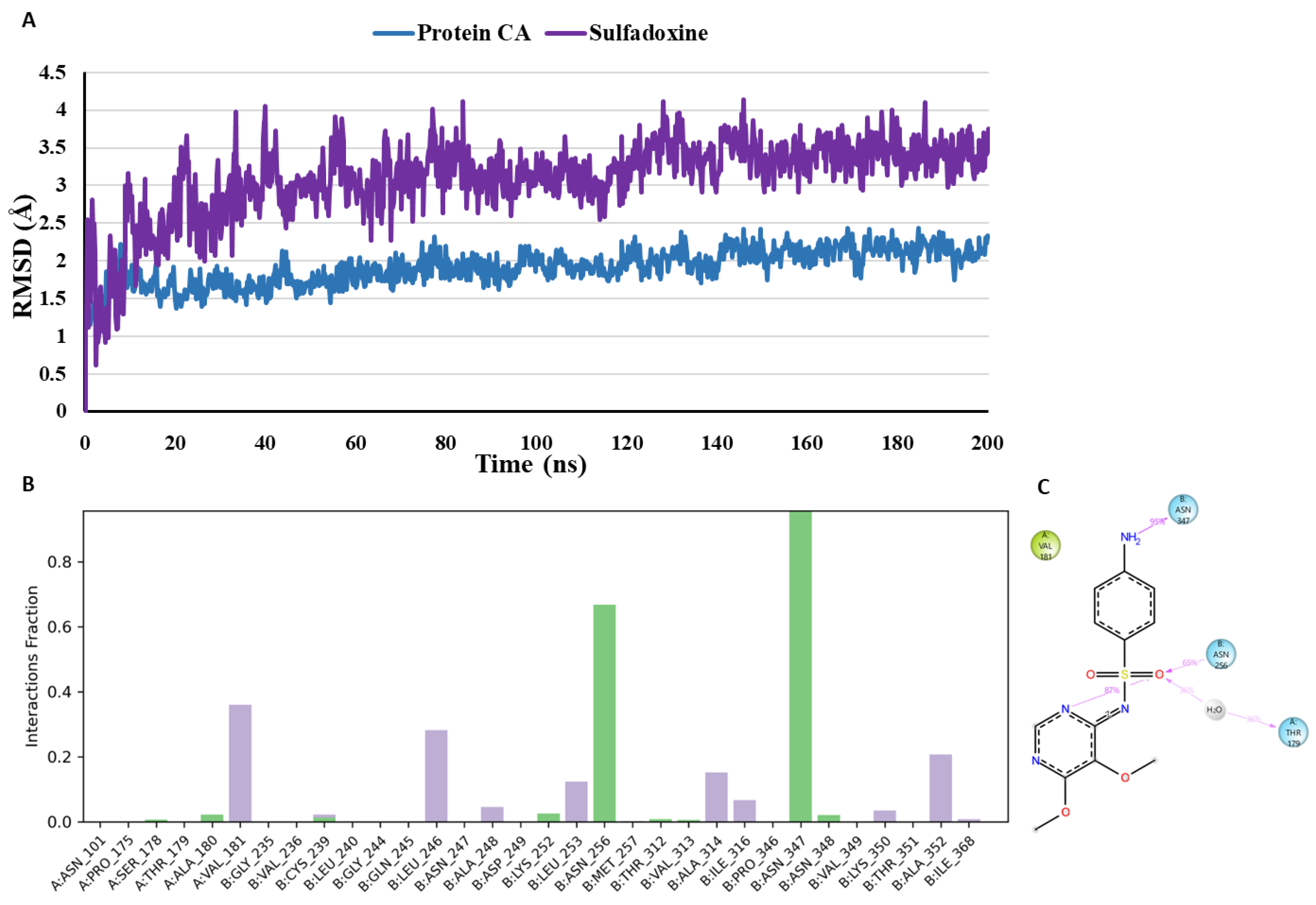

The suggested binding mode of the compound sulfadoxine from the docking studies shows one water mediated interaction with Cys239 (Chain B) and Gly235 (Chain B), and another interaction with Asn347 (Chain B) in the colchicine binding site. Moreover, it was revealed by MD studies that H-bond interactions with the Asn347 (Chain B) and Cys239 (Chain B) was maintained during 96% and 1.3% of the simulation time. Furthermore, MD studies demonstrated the presence of seven additional H-bond interactions between the docked compound sulfadoxine and amino acid residues Asn348 (Chain B), Ser178 (Chain A), Ala180 (Chain A), Lys252 (Chain B), Asn256 (Chain B), Thr312 (Chain B) and Val313 (Chain B). Although theses interactions were not seen in the crystallographic binding pose, yet they were observed during 2.1%, 1%, 2.3%, 2.6%, 67%, 1% and 1% of the simulation time respectively. RMSD plot

(Figure 14) demonstrates that sulfadoxine and the protein exhibit stability over the course of the simulation indicating that it is not undergoing any major conformational changes representing its stability and favourable binding affinity towards the CBS. Cys239 (Chain B) and Asn347 (Chain B) are the common amino acid residues forming H-bond interactions with both co-crystallised inhibitor and sulfadoxine. With sulfadoxine, Cys239 (Chain B) was observed maintaining a low percentage of 1.3% as compared to the co-crystallized inhibitor maintaining this interaction during 17.7% of the simulation time. Furthermore, the H-bond interactions between sulfadoxine and Asn347 (Chain B) was observed maintaining a high percentage of 96% as compared to the co-crystallized inhibitor maintaining this interaction during 77.7% of the simulation time.

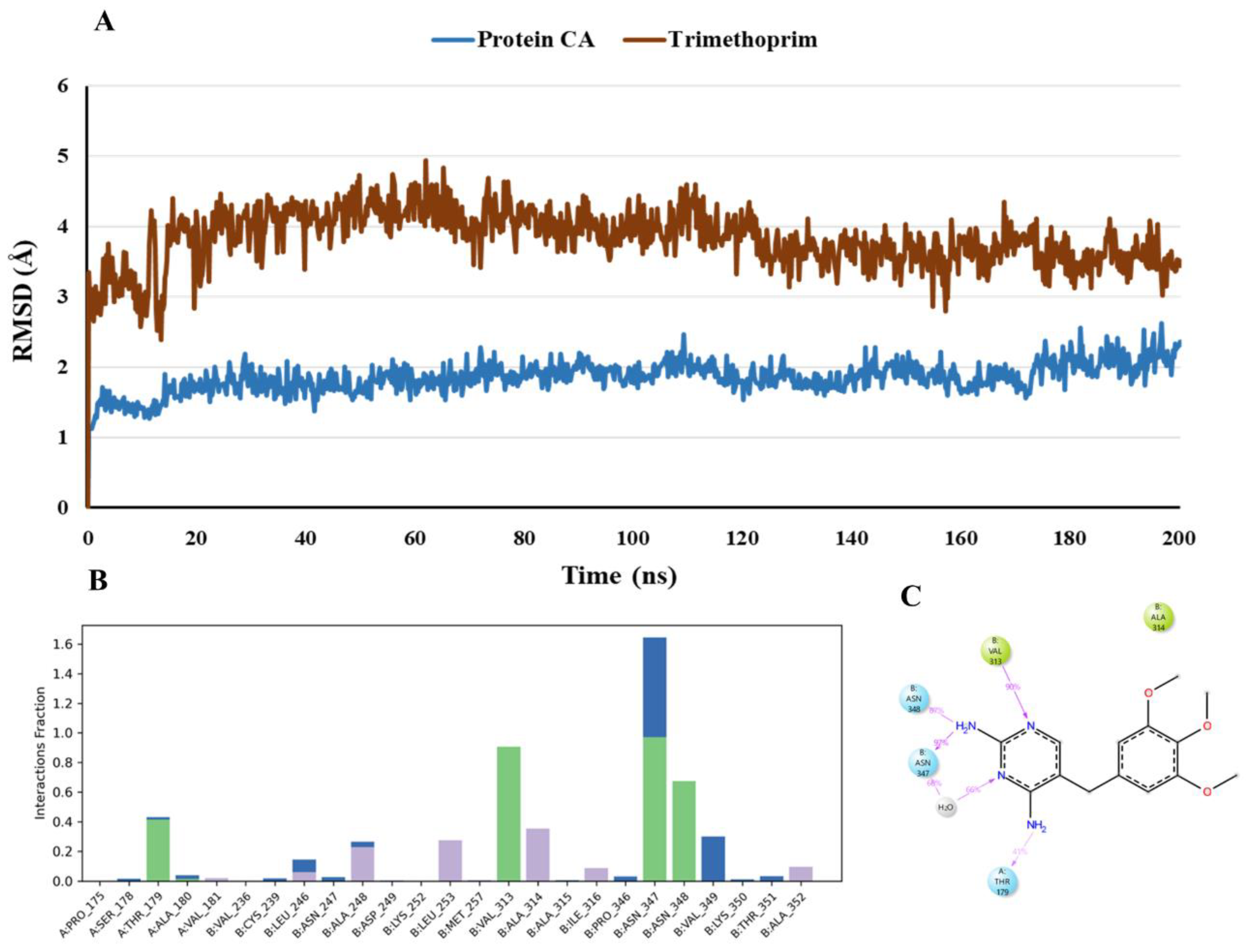

The suggested binding mode of the compound trimethoprim from the docking studies shows one hydrogen-bonded protein-ligand interaction mediated by a water molecule and another interaction with Thr179 (Chain A) in the colchicine binding site. Moreover, it was revealed by MD studies that H-bond interaction with the Thr179 (Chain A) was maintained during 41.2% of the simulation time. Furthermore, MD studies demonstrated the presence of four additional H-bond interactions between the docked compound trimethoprim and Val313 (Chain B), Asn347 (Chain B) , Asn348 (Chain B), and Ala180 (Chain A). Although these interactions were not seen in the crystallographic binding pose, yet these were observed during 90.8%, 97.3%, 67.6% and 1.6% of the simulation time. As revealed by the RMSD plot (

Figure 15), trimethoprim does not show any major fluctuation over the course of the simulation indicating that it is not undergoing any major conformational changes representing its stability in the CBS. Thr179 (Chain A) and Asn347 (Chain B) are two common amino acid residues forming H-bond interactions with both co-crystallized inhibitor and trimethoprim. With trimethoprim, Thr179 (Chain A) was observed maintaining a low percentage of 41.2% as compared to the co-crystallized inhibitor maintaining this interaction during 96.1% of the simulation time. Furthermore, the H-bond interaction between trimethoprim and Asn347 (Chain B) was observed maintaining a high percentage of 97.3% as compared to the co-crystallized inhibitor maintaining this interaction during 77.7% of the simulation time. Trimethoprim is endorsed by the occurrence of essential protein–ligand interactions, as well as the expansion of the H-bond network to Val313 (Chain B), Asn348 (Chain B) and Ala180 (Chain A) during 90.8%, 67.6% and 1.6% of the simulation time.

3.4. Biological Evaluation

We further aimed to identify the compounds inhibiting the microtubules with anticancer assets. To find the anticancer potential of the leads, we performed the resazurin (Alamar Blue) assay on SK-MEL-28 (Melanoma), A549 (Lung), MDAMB-231 (Breast), MCF-7 (Breast), PC-3 (Prostate), and HCT-116 (Colon) cancer cell lines. The investigational hits were treated at three varying concentrations of 1, 5, and 25 µM in comparison to the positive control, colchicine, and paclitaxel. The percentage survival was converted to inhibition, and the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50) was calculated. The outcome, as portrayed in

Table 5, revealed that the leads were able to portray some cytotoxicity towards the cancer cells in comparison to the positive control. The identified leads were found to be particularly potent towards the melanoma cells, where the omeprazole and podofilox portrayed an IC

50 of 4.32 µM and 4.98 µM in comparison to the Paclitaxel (1.98 µM) and Colchicine (2.43 µM). In addition, the compounds were also found to be active in colorectal cancer cells. Here, omeprazole portrayed an IC

50 of 6.22 µM, podofilox of 5.76 µM in comparison to colchicine (4.92 µM). Besides this, compounds were found to possess low to no cytotoxicity towards the other cell lines employed. The analysis thus revealed that omeprazole and podofilox possess significant anticancer potential, particularly towards melanoma and colorectal cell lines.

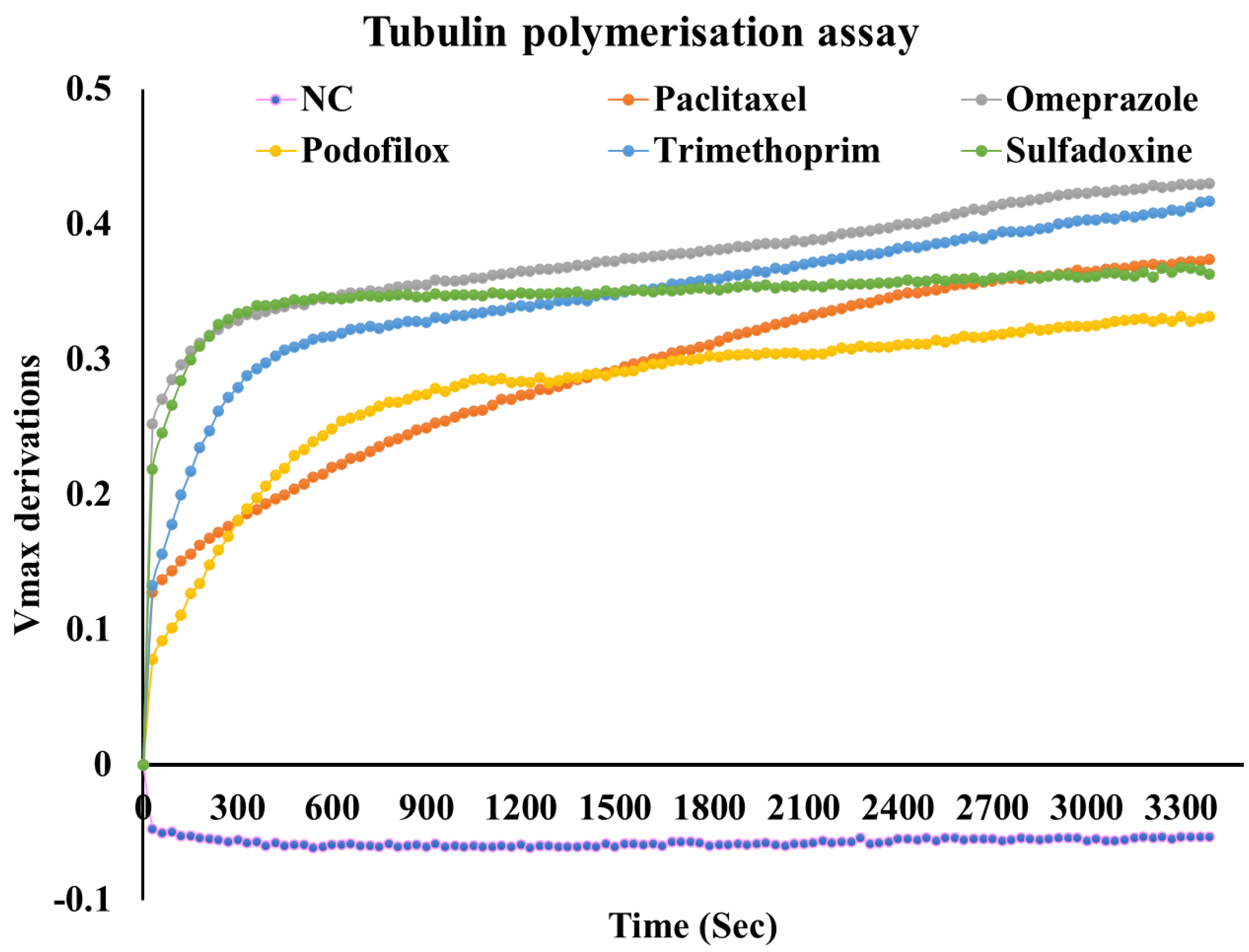

Next, we analysed the impact of top hits on the tubulin dynamics. The tubulin polymerization assay was conducted at a compound concentration of 5 µM, keeping paclitaxel (PCT) as the positive control. The assay relies on the measurement kinetics (Vmax) of microtubule polymerization over time at an absorbance of 340 nm. The increase in Vmax is associated with the polymerization, while the low Vmax is associated with depolymerization or inhibition of microtubule formation. Our analysis revealed (

Figure 16) that podofilox portrayed a low Vmax in comparison to paclitaxel employed as the positive control. In addition, the compounds, sulfadoxine, trimethoprim, and omeprazole, portrayed a higher Vmax in comparison to the positive control. All the compounds were found to stabilize the tubulin polymerization, indicated by a stable Vmax at a later part of the experiment.

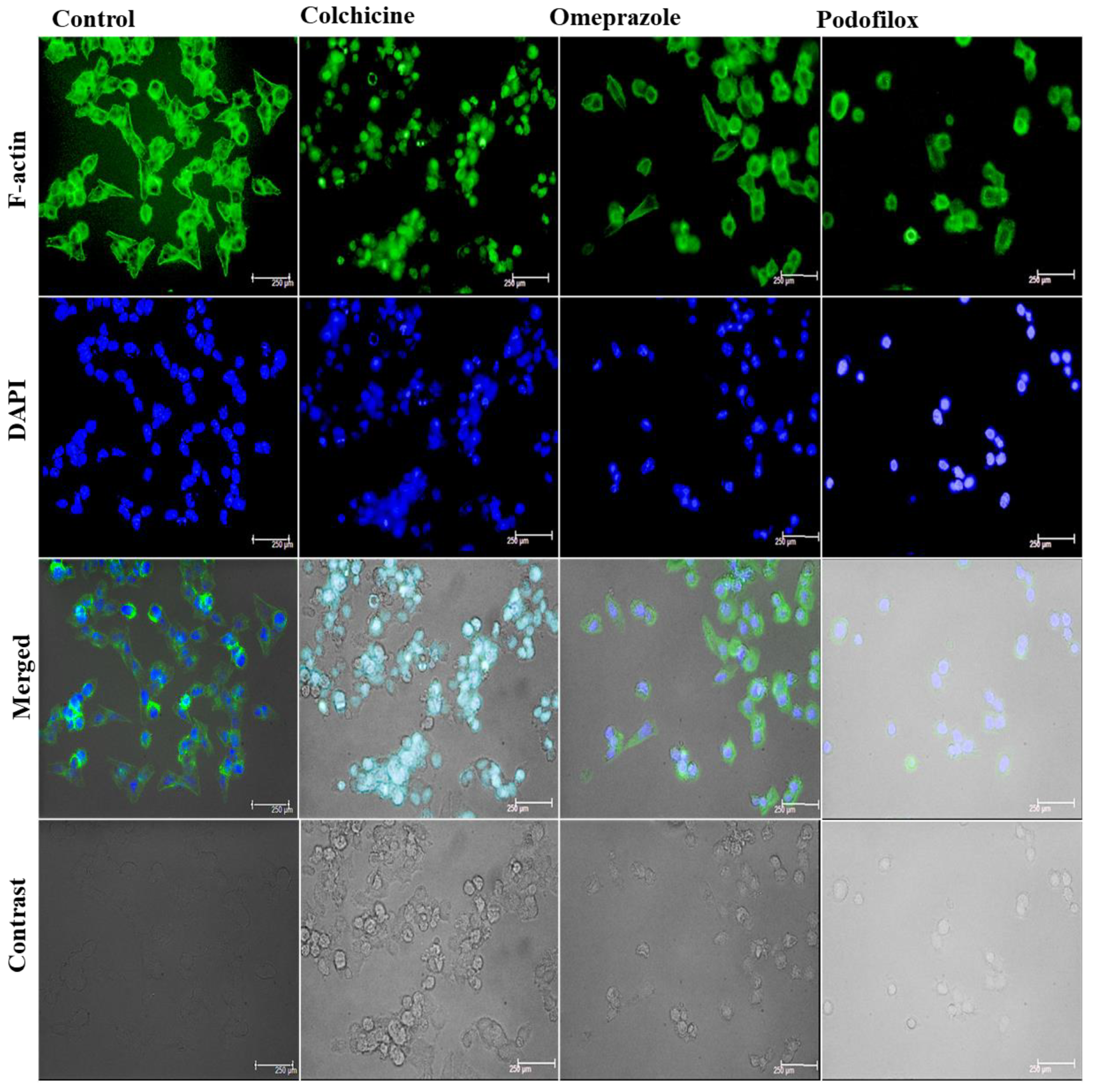

The loss of dynamicity in microtubules is also associated with the morphological changes in the actin cytoskeleton. The peculiar changes include the development of prominent stress fibres, followed by the enrichment of cortical actin and reduced filopodia formation via the activation and crosstalk of GEF-H1–mediated RhoA/ROCK pathway. To visualize the changes, we perform F-actin-based staining analysis on the HCT-116 cells previously treated with the lead compounds (5 µM) for 24 h in comparison to the colchicine.

The analysis revealed (

Figure 17) that cells were well spread in the control (untreated) well, with prominent actin (cortical) and stress fibres (F-actin dye, green in colour), with normal spreading. with evenly distributed nuclei (analysed by DAPI, blue in colour). The treatment with colchicine led to more circular cells (condensed) with fewer actin fibres, whereby the actin was more rim-like in contrast to forming central bundles in the control. This suggests cytoskeletal rearrangement partially, which could be due to microtubule polymerization by colchicine. The treatment with omeprazole indicated a mixed population. Actin filaments were found to be less organized, whereas the treatment with podofilox suggested severe cytoskeletal collapse owing to their anti-tubulin activities. In addition, the nuclear changes upon treatment with lead hits also support the cytotoxicity of these compounds towards HCT-116 cells.

Figure 1.

The illustrative diagram portrays the tubulin and its subunit, the process of polymerization of tubulin to protofilaments, eventually leading to the compact structure of the microtubule, along with the process of hydrolysis (depolymerization) catalyzed by GTP. The figure further reflects the role of microtubules in karyokinesis, followed by cellular division.

Figure 1.

The illustrative diagram portrays the tubulin and its subunit, the process of polymerization of tubulin to protofilaments, eventually leading to the compact structure of the microtubule, along with the process of hydrolysis (depolymerization) catalyzed by GTP. The figure further reflects the role of microtubules in karyokinesis, followed by cellular division.

Figure 2.

A. The key druggable binding sites reported in the microtubules; B. Important drugs (approved and investigational) interacting at taxane, vinca, and colchicine binding sites.

Figure 2.

A. The key druggable binding sites reported in the microtubules; B. Important drugs (approved and investigational) interacting at taxane, vinca, and colchicine binding sites.

Scheme 1.

ML-driven computational drug repurposing workflow.

Scheme 1.

ML-driven computational drug repurposing workflow.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal of tubulin in complex with the co-crystallized inhibitor G8K (PDB code: 6O5M). Chain A and Chain B of tubulin are coloured in pink and cyan, respectively, while the co-crystallized inhibitor is coloured in orange.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal of tubulin in complex with the co-crystallized inhibitor G8K (PDB code: 6O5M). Chain A and Chain B of tubulin are coloured in pink and cyan, respectively, while the co-crystallized inhibitor is coloured in orange.

Figure 4.

Colchicine binding site (CBS) view of the tubulin protein, showing intermolecular contacts of the co-crystallized inhibitor G8K. (A) key residues are shown (B) all residues of the binding site are shown. G8K is coloured in orange, while the binding site residues are in blue.

Figure 4.

Colchicine binding site (CBS) view of the tubulin protein, showing intermolecular contacts of the co-crystallized inhibitor G8K. (A) key residues are shown (B) all residues of the binding site are shown. G8K is coloured in orange, while the binding site residues are in blue.

Figure 5.

Redocking study of the co-crystallized inhibitor G8K of tubulin. (A) The co-crystallized inhibitor pose is shown in orange. (B) The docking pose (Glide XP) is shown in green, perfectly superposed with the co-crystallized pose.

Figure 5.

Redocking study of the co-crystallized inhibitor G8K of tubulin. (A) The co-crystallized inhibitor pose is shown in orange. (B) The docking pose (Glide XP) is shown in green, perfectly superposed with the co-crystallized pose.

Figure 6.

Structure-based virtual screening workflow.

Figure 6.

Structure-based virtual screening workflow.

Figure 7.

Binding mode of Podofilox (green) representing 3D (A) and 2D (B) interactions in the colchicine binding site (CBS) of tubulin. .

Figure 7.

Binding mode of Podofilox (green) representing 3D (A) and 2D (B) interactions in the colchicine binding site (CBS) of tubulin. .

Figure 8.

Binding mode of Omeprazole (pink) representing 3D (A) and 2D (B) interactions in the colchicine binding site of tubulin. .

Figure 8.

Binding mode of Omeprazole (pink) representing 3D (A) and 2D (B) interactions in the colchicine binding site of tubulin. .

Figure 9.

Binding mode of Sulfadoxine (purple) representing 3D (A) and 2D (B) interactions in the colchicine binding site of tubulin.

Figure 9.

Binding mode of Sulfadoxine (purple) representing 3D (A) and 2D (B) interactions in the colchicine binding site of tubulin.

Figure 10.

Binding mode of Trimethoprim (brown) representing 3D (A) and 2D (B) interactions in the colchicine binding site of tubulin. .

Figure 10.

Binding mode of Trimethoprim (brown) representing 3D (A) and 2D (B) interactions in the colchicine binding site of tubulin. .

Figure 11.

(A) RMSD analysis of co-crystallized inhibitor (inhibitor in orange, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of co-crystallised inhibitor in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, lipophilic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are represented in blue colour) (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 11.

(A) RMSD analysis of co-crystallized inhibitor (inhibitor in orange, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of co-crystallised inhibitor in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, lipophilic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are represented in blue colour) (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 12.

(A) RMSD analysis of the docked compound podofilox (podofilox in green, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation. (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of podofilox in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, lipophilic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are represented in blue colour). (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 12.

(A) RMSD analysis of the docked compound podofilox (podofilox in green, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation. (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of podofilox in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, lipophilic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are represented in blue colour). (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 13.

(A) RMSD analysis of the docked compound omeprazole (omeprazole in pink, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation. (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of omeprazole in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, hydrophobic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are shown in blue colour). (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 13.

(A) RMSD analysis of the docked compound omeprazole (omeprazole in pink, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation. (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of omeprazole in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, hydrophobic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are shown in blue colour). (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 14.

(A) RMSD analysis of the docked compound sulfadoxine (sulfadoxine in purple, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation. (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of sulfadoxine in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, hydrophobic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are represented in blue colour). (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 14.

(A) RMSD analysis of the docked compound sulfadoxine (sulfadoxine in purple, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation. (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of sulfadoxine in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, hydrophobic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are represented in blue colour). (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 15.

(A) RMSD analysis of the docked compound trimethoprim (trimethoprim in brown, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation. (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of trimethoprim in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, hydrophobic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are shown in blue colour). (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory ( 0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 15.

(A) RMSD analysis of the docked compound trimethoprim (trimethoprim in brown, protein α-carbons in dark blue) during the 200 ns simulation. (B) Protein-ligand interaction histogram from the MD simulations of trimethoprim in the tubulin binding site (H-bonds are shown in green, hydrophobic contacts are shown in light purple and water bridges are shown in blue colour). (C) A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 30.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory ( 0.00 through 200 ns), are shown.

Figure 16.

Outcome of tubulin polymerization assay. The analysis revealed the compounds stabilized the microtubules, leading to a loss in their dynamicity and plausible inhibition (NC: Negative control).

Figure 16.

Outcome of tubulin polymerization assay. The analysis revealed the compounds stabilized the microtubules, leading to a loss in their dynamicity and plausible inhibition (NC: Negative control).

Figure 17.

Fluorescence analysis of F-actin organization (Green colour) in cells, along with DAPI staining (blue colour), following treatment with investigational hits, omeprazole, and podofilox, and positive control colchicine in HCT-116 cells in comparison to the untreated cells (control). The image also portrays the merged and contrast images for each intervention.

Figure 17.

Fluorescence analysis of F-actin organization (Green colour) in cells, along with DAPI staining (blue colour), following treatment with investigational hits, omeprazole, and podofilox, and positive control colchicine in HCT-116 cells in comparison to the untreated cells (control). The image also portrays the merged and contrast images for each intervention.

Table 1.

Performance of top 10 ML models for tubulin inhibitor classification.

Table 1.

Performance of top 10 ML models for tubulin inhibitor classification.

| Entry |

Model Name |

Algorithm |

Descriptor Type |

Model Score |

| 1. |

Bayes_dendritic_1 |

Bayesian Classification |

Dendritic Fingerprints |

0.9389 |

| 2. |

Bayes_linear_20 |

Bayesian Classification |

Linear Fingerprints |

0.9337 |

| 3. |

Bayes_linear_2 |

Bayesian Classification |

Linear Fingerprints |

0.9257 |

| 4. |

Bayes_dendritic_2 |

Bayesian Classification |

Dendritic Fingerprints |

0.9256 |

| 5. |

Bayes_linear_33 |

Bayesian Classification |

Linear Fingerprints |

0.9237 |

| 6. |

Bayes_molprint2D_46 |

Bayesian Classification |

Mol2D Fingerprints |

0.9200 |

| 7. |

Bayes_linear_1 |

Bayesian Classification |

Linear Fingerprints |

0.9185 |

| 8. |

RP_30 |

Recursive Partitioning |

Mixed Descriptor Set |

0.9158 |

| 9. |

Bayes_dendritic_33 |

Bayesian Classification |

Dendritic Fingerprints |

0.9146 |

| 10. |

RP_41 |

Recursive Partitioning |

Mixed Descriptor Set |

0.9133 |

Table 2.

Performance of the best bayes regression model (bayes_dendritic_1).

Table 2.

Performance of the best bayes regression model (bayes_dendritic_1).

| Dataset |

RMS Err |

Correlation (r) |

R2/Q2 |

| Training |

0.2246 |

0.9045 |

0.8182 |

| Test |

0.2374 |

0.8988 |

0.8078 |

Table 3.

Performance of the recursive partitioning classification model (RP_30).

Table 3.

Performance of the recursive partitioning classification model (RP_30).

| Dataset |

Class |

TP |

FP |

TN |

FN |

Recall |

Precision |

Specificity |

F-measure |

| Training set |

Active |

125 |

11 |

78 |

4 |

0.969 |

0.919 |

0.876 |

0.943 |

| Inactive |

78 |

4 |

125 |

11 |

0.876 |

0.951 |

0.969 |

0.912 |

| Test set |

Active |

41 |

4 |

25 |

1 |

0.976 |

0.911 |

0.862 |

0.943 |

| Inactive |

25 |

1 |

41 |

4 |

0.862 |

0.962 |

0.976 |

0.909 |

Table 4.

Glide XP docking scores of top 10 compounds along with their binding energetics.

Table 4.

Glide XP docking scores of top 10 compounds along with their binding energetics.

| Entry |

Compound |

Glide XP Docking Score (Kcal/mol) |

ΔGbind

(Kcal/mol)

|

ΔGcoulomb

(Kcal/mol)

|

| 1. |

Arformoterol |

-10.061 |

-18.12 |

-21.37 |

| 2. |

Podofilox |

-9.908 |

-38.61 |

-22.45 |

| 3. |

Tretoquinol |

-9.857 |

-17.73 |

-20.95 |

| 4. |

Terizidone |

-9.219 |

-25.83 |

-17.28 |

| 5. |

Rucaparib |

-9.145 |

-19.46 |

-15.23 |

| 6. |

Aminoglutethimide |

-8.99 |

-26.59 |

-6.77 |

| 7. |

Sulfadoxine |

-8.763 |

-50.56 |

15.89 |

| 8. |

Naftifine |

-8.531 |

-32.33 |

-6.58 |

| 9. |

Omeprazole |

-8.362 |

-64.16 |

-58.31 |

| 10. |

Trimethoprim |

-8.117 |

-43.89 |

-18.9 |

| 11. |

Co-crystallized G8K |

-12.365 |

-74.07 |

-29.70 |

Table 5.

Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) portrayed by identified hits in the panel of cancer cell lines.

Table 5.

Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) portrayed by identified hits in the panel of cancer cell lines.

| Code |

Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) (µM) ± SD |

| |

SK-MEL-28

(Melanoma) |

A549

(Lung) |

MDAMB-231

(Breast) |

MCF-7

(Breast) |

PC-3

(Prostate) |

HCT-116 (Colon) |

| Omeprazole |

4.32±0.29 |

17.32±0.19 |

21.65±0.21 |

13.44±0.26 |

12.22±0.18 |

6.22±0.22 |

| Podofilox |

4.98±0.37 |

>25 |

19.83±0.24 |

13.61±0.18 |

15.93±0.31 |

5.76±0.18 |

| Trimethoprim |

7.46±0.19 |

>25 |

>25 |

>25 |

18.65±0.28 |

11.32±0.31 |

| Sulfadoxine |

5.22±0.33 |

>25 |

16.11±0.19 |

18.22±0.27 |

13.98±0.22 |

8.88±0.27 |

| Paclitaxel |

1.98±0.31 |

2.22±0.35 |

3.89±0.22 |

3.22±0.33 |

4.86±0.19 |

NT |

| Colchicine |

2.43±0.19 |

2.11±0.22 |

2.54±0.31 |

2.89±0.24 |

4.02±0.16 |

4.92±0.19 |