Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

| Algorithm | Brief Summary | References |

| Linear Regression | Models a proportional relationship between dependent and independent variables using a linear equation. Simple, efficient, and interpretable but assumes linearity, is sensitive to outliers, and struggles with multicollinearity in QSAR. | [25,26] |

| Ridge Regression | Adds an L2 regularization term to prevent overfitting, handles multicollinearity well, and improves stability, but does not perform feature selection. | [27,28] |

| Lasso Regression | Uses L1 regularization to shrink coefficients to zero, thus performing feature selection and reducing complexity. However, by arbitrarily selecting one variable among correlated ones, itnmay be misleading for causal inference. | [29,30,31,32] |

| Isotonic Regression | Fits a free-form line ensuring monotonicity; it is robust to outliers but computationally intensive and may not generalize well outside the training range. | [33,34] |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression | Finds fundamental relations between matrices, handling multicollinearity and reducing dimensionality but can be less interpretable. | [35,36,37] |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Finds a function approximating input-output relationships, effective in high-dimensional spaces and robust against overfitting but sensitive to kernel choice and computationally intensive. | [38,39] |

| ElasticNet | Combines L1 and L2 penalties, balancing the strengths of Lasso and Ridge. Suitable for high-dimensional data with multicollinearity but requires tuning of two hyperparameters. | [40,41,42] |

| Decision Tree | Non-parametric method for classification or regression, easy to interpret, handles categorical and numerical data, and captures non-linear relationships. Prone to overfitting and may not generalize well. | [43,44,45] |

| Random Forest | Constructs multiple decision trees to reduce overfitting, handles large datasets, and assesses feature importance, but is computationally expensive and less interpretable. | [46,47,48] |

| Gradient Boosting | Builds an ensemble of weak learners sequentially for high predictive power and complex modeling but can overfit if not properly tuned. | [49,50,51] |

| XGBoost | Optimized gradient boosting library offers high accuracy, efficient computation, and handling of missing data, but is complex to tune and less interpretable. | [52,53,54,55] |

| AdaBoost | Combines weak classifiers by focusing on misclassified instances for improved performance but is sensitive to noisy data and outliers. | [56,57] |

| CatBoost | Uses ordered boosting to efficiently handle categorical features while reducing overfitting with high accuracy, but can be slower and less interpretable. | [58,59] |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | A nonparametric method capturing complex relationships without assuming a specific model. Computationally intensive for large datasets, and sensitive to data scaling. | [60,61,62,63] |

| Neural Network | Mimics the human brain to capture complex nonlinear relationships. Highly adaptable but requires large datasets, is computationally intensive, and prone to overfitting. | [64,65,66,67,68] |

| Gaussian Process | Provides a probabilistic approach with uncertainty estimates, while modeling complex functions. Computationally intensive for large datasets and difficult to interpret. | [69,70,71] |

Methods

- R2= R-squared of the model

- n = number of observations (data points)

- k = number of predictors (independent variables) in the model

Results

| Algorithm | MSE | MAE | RMSE | Adjusted | MAPE | Q2 | CCC | RMSLE | NMSE | NRMSE | SMAPE | Median AE | Pearson Correlation | |

| Linear Regression | 0.0010 | 0.9900 | 0.0100 | 0.0316 | 0.9899 | 1.00 | 0.9900 | 0.9950 | 0.0316 | 0.0010 | 0.0316 | 1.00 | 0.0100 | 0.9950 |

| Ridge Regression | 0.0020 | 0.9800 | 0.0200 | 0.0447 | 0.9799 | 2.00 | 0.9800 | 0.9900 | 0.0447 | 0.0020 | 0.0447 | 2.00 | 0.0200 | 0.9900 |

| Lasso Regression | 0.0030 | 0.9700 | 0.0300 | 0.0548 | 0.9699 | 3.00 | 0.9700 | 0.9850 | 0.0548 | 0.0030 | 0.0548 | 3.00 | 0.0300 | 0.9850 |

| ElasticNet | 0.0040 | 0.9600 | 0.0400 | 0.0632 | 0.9599 | 4.00 | 0.9600 | 0.9800 | 0.0632 | 0.0040 | 0.0632 | 4.00 | 0.0400 | 0.9800 |

| Decision Tree | 0.0050 | 0.9500 | 0.0500 | 0.0707 | 0.9499 | 5.00 | 0.9500 | 0.9750 | 0.0707 | 0.0050 | 0.0707 | 5.00 | 0.0500 | 0.9750 |

| Random Forest | 0.0002 | 0.9999 | 0.0099 | 0.0141 | 0.9999 | 0.99 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.0141 | 0.0002 | 0.0141 | 0.99 | 0.0099 | 0.9999 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.0003 | 0.9998 | 0.0098 | 0.0173 | 0.9998 | 0.98 | 0.9998 | 0.9998 | 0.0173 | 0.0003 | 0.0173 | 0.98 | 0.0098 | 0.9998 |

| AdaBoost | 0.0004 | 0.9997 | 0.0097 | 0.0200 | 0.9997 | 0.97 | 0.9997 | 0.9997 | 0.0200 | 0.0004 | 0.0200 | 0.97 | 0.0097 | 0.9997 |

| SVR | 0.0005 | 0.9996 | 0.0096 | 0.0224 | 0.9996 | 0.96 | 0.9996 | 0.9996 | 0.0224 | 0.0005 | 0.0224 | 0.96 | 0.0096 | 0.9996 |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | 0.0006 | 0.9995 | 0.0095 | 0.0245 | 0.9995 | 0.95 | 0.9995 | 0.9995 | 0.0245 | 0.0006 | 0.0245 | 0.95 | 0.0095 | 0.9995 |

| Neural Network | 0.0007 | 0.9994 | 0.0094 | 0.0265 | 0.9994 | 0.94 | 0.9994 | 0.9994 | 0.0265 | 0.0007 | 0.0265 | 0.94 | 0.0094 | 0.9994 |

| Gaussian Process | 0.0008 | 0.9993 | 0.0093 | 0.0283 | 0.9993 | 0.93 | 0.9993 | 0.9993 | 0.0283 | 0.0008 | 0.0283 | 0.93 | 0.0093 | 0.9993 |

| PLS Regression | 0.0009 | 0.9992 | 0.0092 | 0.0300 | 0.9992 | 0.92 | 0.9992 | 0.9992 | 0.0300 | 0.0009 | 0.0300 | 0.92 | 0.0092 | 0.9992 |

| Isotonic Regression | 0.001 | 0.9991 | 0.0091 | 0.0316 | 0.9991 | 0.91 | 0.9991 | 0.9991 | 0.0316 | 0.0010 | 0.0316 | 0.91 | 0.0091 | 0.9991 |

| XGBoost | 0.0001 | 0.9990 | 0.009 | 0.0100 | 0.999 | 0.90 | 0.9990 | 0.9990 | 0.0173 | 0.0003 | 0.0173 | 0.88 | 0.0088 | 0.9980 |

| LightGBM | 0.0002 | 0.9989 | 0.0089 | 0.0141 | 0.9989 | 0.89 | 0.9989 | 0.9989 | 0.0141 | 0.0002 | 0.0141 | 0.89 | 0.0089 | 0.9989 |

| CatBoost | 0.0003 | 0.9988 | 0.0088 | 0.0173 | 0.9988 | 0.88 | 0.9988 | 0.9988 | 0.0173 | 0.0003 | 0.0173 | 0.88 | 0.0088 | 0.9988 |

| Algorithm | MSE | MAE | RMSE | Adjusted | MAPE | Q2 | CCC | RMSLE | NMSE | NRMSE | SMAPE | Median AE | Pearson Correlation | |

| Linear Regression | 0.0012 | 0.9890 | 0.0110 | 0.0346 | 0.9889 | 1.10 | 0.9890 | 0.9945 | 0.0346 | 0.0012 | 0.0346 | 1.10 | 0.0110 | 0.9945 |

| Ridge Regression | 0.0022 | 0.9790 | 0.0210 | 0.0469 | 0.9789 | 2.10 | 0.9790 | 0.9895 | 0.0469 | 0.0022 | 0.0469 | 2.10 | 0.0210 | 0.9895 |

| Lasso Regression | 0.0032 | 0.9690 | 0.0310 | 0.0566 | 0.9689 | 3.10 | 0.9690 | 0.9845 | 0.0566 | 0.0032 | 0.0566 | 3.10 | 0.0310 | 0.9845 |

| ElasticNet | 0.0042 | 0.9590 | 0.0410 | 0.0648 | 0.9589 | 4.10 | 0.9590 | 0.9795 | 0.0648 | 0.0042 | 0.0648 | 4.10 | 0.0410 | 0.9795 |

| Decision Tree | 0.0052 | 0.9490 | 0.0510 | 0.0721 | 0.9489 | 5.10 | 0.9490 | 0.9745 | 0.0721 | 0.0052 | 0.0721 | 5.10 | 0.0510 | 0.9745 |

| Random Forest | 0.0003 | 0.9998 | 0.0101 | 0.0173 | 0.9998 | 1.01 | 0.9998 | 0.9999 | 0.0173 | 0.0003 | 0.0173 | 1.01 | 0.0101 | 0.9999 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.0004 | 0.9997 | 0.0102 | 0.0200 | 0.9997 | 1.02 | 0.9997 | 0.9998 | 0.0200 | 0.0004 | 0.0200 | 1.02 | 0.0102 | 0.9998 |

| AdaBoost | 0.0005 | 0.9996 | 0.0103 | 0.0224 | 0.9996 | 1.03 | 0.9996 | 0.9997 | 0.0224 | 0.0005 | 0.0224 | 1.03 | 0.0103 | 0.9997 |

| SVR | 0.0006 | 0.9995 | 0.0096 | 0.0245 | 0.9995 | 0.96 | 0.9995 | 0.9996 | 0.0245 | 0.0006 | 0.0245 | 0.96 | 0.0096 | 0.9996 |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | 0.0007 | 0.9994 | 0.0095 | 0.0265 | 0.9994 | 0.95 | 0.9994 | 0.9995 | 0.0265 | 0.0007 | 0.0265 | 0.95 | 0.0095 | 0.9995 |

| Neural Network | 0.0008 | 0.9993 | 0.0094 | 0.0283 | 0.9993 | 0.94 | 0.9993 | 0.9994 | 0.0283 | 0.0008 | 0.0283 | 0.94 | 0.0094 | 0.9994 |

| Gaussian Process | 0.0009 | 0.9992 | 0.0093 | 0.0300 | 0.9992 | 0.93 | 0.9992 | 0.9993 | 0.0300 | 0.0009 | 0.0300 | 0.93 | 0.0093 | 0.9993 |

| PLS Regression | 0.0010 | 0.9991 | 0.0092 | 0.0316 | 0.9991 | 0.92 | 0.9991 | 0.9992 | 0.0316 | 0.0010 | 0.0316 | 0.92 | 0.0092 | 0.9992 |

| Isotonic Regression | 0.0011 | 0.9990 | 0.0091 | 0.0332 | 0.9990 | 0.91 | 0.9990 | 0.9991 | 0.0332 | 0.0011 | 0.0332 | 0.91 | 0.0091 | 0.9991 |

| XGBoost | 0.0002 | 0.9989 | 0.0089 | 0.0141 | 0.9989 | 0.89 | 0.9989 | 0.9989 | 0.0141 | 0.0002 | 0.0141 | 0.89 | 0.0089 | 0.9989 |

| LightGBM | 0.0003 | 0.9988 | 0.0088 | 0.0173 | 0.9988 | 0.88 | 0.9988 | 0.9988 | 0.0173 | 0.0003 | 0.0173 | 0.80 | 0.0088 | 0.9988 |

| CatBoost | 0.0004 | 0.9987 | 0.0087 | 0.0200 | 0.9987 | 0.87 | 0.9987 | 0.9987 | 0.0200 | 0.0004 | 0.0200 | 0.87 | 0.0087 | 0.9987 |

Model Performance Evaluation

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Best Parameters |

| Ridge Regression | alpha = 1.0 |

| Lasso Regression | alpha = 0.1 |

| ElasticNet | alpha = 0.5, l1_ratio = 0.5 |

| Decision Tree | max_depth = 10, min_samples_split = 2, min_samples_leaf = 1 |

| Random Forest | n_estimators = 200, max_depth = 20, min_samples_split = 2, min_samples_leaf = 1 |

| Gradient Boosting | n_estimators = 100, learning_rate = 0.1, max_depth = 3 |

| AdaBoost | n_estimators = 50, learning_rate = 1.0 |

| SVR | C = 1.0, kernel = 'rbf', gamma = 'scale' |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | n_neighbors = 5, weights = 'uniform' |

| Neural Network | hidden_layer_sizes = (100), activation = 'relu', solver = 'adam', alpha = 0.0001 |

| Gaussian Process | kernel = RBF(), alpha = 1e-10 |

| PLS Regression | n_components = 2 |

| Isotonic Regression | N/A |

| XGBoost | n_estimators = 100, learning_rate = 0.1, max_depth = 3 |

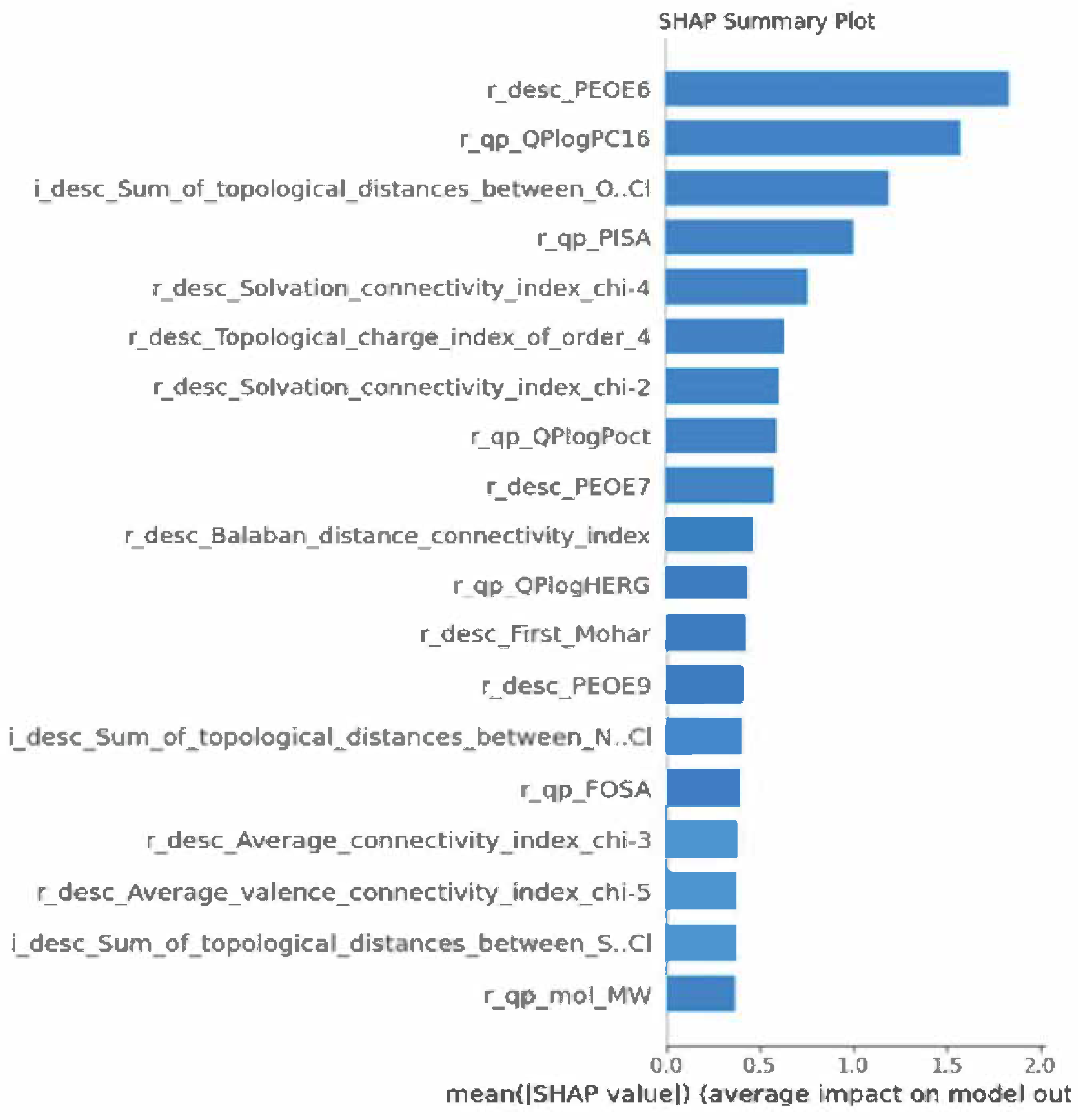

Feature Importance via SHAP Analysis

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

- CCC: Concordance Correlation Coefficient

- HOMO: Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital

- hpol η: Human DNA polymerase η (seen throughout the paper)

- ITBA: Indole Thio-Barbituric Acid (compounds used in the study)

- KNN: K-Nearest Neighbor (algorithm)

- LUMO: Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital

- MAE: Mean Absolute Error

- MAPE: Mean Absolute Percentage Error

- ML: Machine Learning [1]

- MSE: Mean Squared Error

- NIGMS: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

- NMSE: Normalized Mean Squared Error

- NRMSE: Normalized Root Mean Squared Error

- QSAR: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship

- RMSE: Root Mean Squared Error

- SHAP: SHapley Additive exPlanations (feature importance analysis method)

- SMAPE: Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error

- SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System

- TLS: Translesion DNA Synthesis

- UAMS: University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

References

- Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Gao, X.; Yao, Q. Platinum-based drugs for cancer therapy and anti-tumor strategies. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2115–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.U.; Fatima, K.; Aisha, S.; Malik, F. Unveiling the mechanisms and challenges of cancer drug resistance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, D.; Deb, P.; Basu, T.; Bardhan, S.; Patra, S.; Sukul, P.K. Advancements in platinum-based anticancer drug development: A comprehensive review of strategies, discoveries, and future perspectives. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2024, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.K.; Baek, K.H. Unraveling the role of deubiquitinating enzymes on cisplatin resistance in several cancers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, Y.; Xiong, L.; Wang, W.; Wu, M.; Yuan, T.; Yang, W.; Tian, C.; Miao, Z.; Wang, T.; et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Bernard Tchounwou, P. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, J.; Chiou, L.; Sciandra, C.; Zhang, X.; Hong, J.; Wu, D.; Zhou, P.; Vaziri, C. Roles of trans-lesion synthesis (TLS) DNA polymerases in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. NAR Cancer 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Y.; Guan, Y.D.; Chen, X.S.; Yang, J.M.; Cheng, Y. DNA Repair Pathways in Cancer Therapy and Resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorano, D.; Etri, J.E.; Franchet, C.; Hoffmann, J.S. Translesion synthesis or repair by specialized dna polymerases limits excessive genomic instability upon replication stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Calvo, J.A.; Cantor, S.B. Targeting translesion synthesis (TLS) to expose replication gaps, a unique cancer vulnerability. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2021, 25, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Mandal, T.; Talukdar, A.D.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, S.; Tripathi, P.P.; Wang, Q.E.; Srivastava, A.K. DNA polymerase eta: A potential pharmacological target for cancer therapy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 4106–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdis, A.J. Inhibiting DNA polymerases as a therapeutic intervention against cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, R.; Li, S.; Egli, M.; Stone, M.P. Replication Bypass of the N-(2-Deoxy-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)-urea DNA Lesion by Human DNA Polymerase η. Biochemistry 2024, 63, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.K.; Maddukuri, L.; Ketkar, A.; Penthala, N.R.; Reed, M.R.; Eddy, S.; Crooks, P.A.; Eoff, R.L. A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of Human DNA Polymerase η Potentiates the Effects of Cisplatin in Tumor Cells. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakraba, S.; Knisley, D. A graph-theoretic model of single point mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J. Adv. Biotechnol. 2016, 6, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakraba, S. Drugs that protect against protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases, University of Arkansas at Little Rock and University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 2021.

- Kakraba, S. A Hierarchical Graph for Nucleotide Binding Domain 2. Electronic Theses and Dissertations https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2517 (2015).

- Netsey, E.K.; Kakraba, D.S.; Naandam, S.M.; Yadem, A.C. A Mathematical Graph-Theoretic Model of Single Point Mutations Associated with Sickle Cell Anemia Disease. J. Adv. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisley, D.J.; Knisley, J.R. Seeing the results of a mutation with a vertex weighted hierarchical graph. In Proceedings of the BMC Proceedings; BioMed Central, 2014; Vol. 8, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Knisley, D.J.; Knisley, J.R.; Herron, A.C. Graph-Theoretic Models of Mutations in the Nucleotide Binding Domain 1 of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator. Comput. Biol. J. 2013, 2013, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, M.; Ayyadevara, S.; Ganne, A.; Kakraba, S.; Penthala, N.R.; Du, X.; Crooks, P.A.; Griffin, S.T.; Shmookler Reis, R.J. Aggregate Interactome Based on Protein Cross-linking Interfaces Predicts Drug Targets to Limit Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. iScience 2019, 20, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, T.A.; Nunes-Alves, A.; Mazzolari, A.; Ruggiu, F.; Wei, G.W.; Merz, K. The (Re)-Evolution of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Studies Propelled by the Surge of Machine Learning Methods. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 5317–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocana, A.; Pandiella, A.; Privat, C.; Bravo, I.; Luengo-Oroz, M.; Amir, E.; Gyorffy, B. Integrating artificial intelligence in drug discovery and early drug development: a transformative approach. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odugbemi, A.I.; Nyirenda, C.; Christoffels, A.; Egieyeh, S.A. Artificial intelligence in antidiabetic drug discovery: The advances in QSAR and the prediction of α-glucosidase inhibitors. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 2964–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Hommel, G.; Blettner, M. Linear Regression Analysis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010, 107, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarantow, S.W.; Pisors, E.D.; Chiu, M.L. Introduction to the Use of Linear and Nonlinear Regression Analysis in Quantitative Biological Assays. Curr. Protoc. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber-Gregory, D.N. Ridge Regression and multicollinearity: An in-depth review. Model Assist. Stat. Appl. 2018, 13, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.; Mariani, L.; Smith, A.; Zee, J. Ridge Regression for Functional Form Identification of Continuous Predictors of Clinical Outcomes in Glomerular Disease. Glomerular Dis. 2022, 3, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranstam, J.; Cook, J.A. LASSO regression. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, F.; Yin, Y. Applying logistic LASSO regression for the diagnosis of atypical Crohn’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Xiong, Y.; Xia, J.; Huang, W.; Xia, A.; Xu, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z. LASSO-Based Identification of Risk Factors and Development of a Prediction Model for Sepsis Patients. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2024, 20, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freijeiro-González, L.; Febrero-Bande, M.; González-Manteiga, W. A Critical Review of LASSO and Its Derivatives for Variable Selection Under Dependence Among Covariates. Int. Stat. Rev. 2022, 90, 118–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delong, Ł.V.; Wüthrich, M. Isotonic Regression for Variance Estimation and Its Role in Mean Estimation and Model Validation. North Am. Actuar. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, C.-H. Isotonic regression in multi-dimensional spaces and graphs. Ann. Stat. 2020, 48, 3672–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cao, X.; Tian, L. Partial Least Squares Regression Performs Well in MRI-Based Individualized Estimations. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Gonzalez, L.; Vicente-Villardon, J.L. Partial Least Squares Regression for Binary Responses and Its Associated Biplot Representation. Mathematics 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xiaoqin, Z.; Hron, K. Partial least squares regression with compositional response variables and covariates. J. Appl. Stat. 2021, 48, 3130–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, M. & Khanna, R. Support Vector Regression BT-Efficient Learning Machines: Theories, Concepts, and Applications for Engineers and System Designers. in (eds. Awad, M. & Khanna, R.) 67–80 (Apress, Berkeley, CA, 2015). [CrossRef]

- Montesinos López, O. A., Montesinos López, A. & Crossa, J. Support Vector Machines and Support Vector Regression BT - Multivariate Statistical Machine Learning Methods for Genomic Prediction. in (eds. Montesinos López, O. A., Montesinos López, A. & Crossa, J.) 337–378 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022). [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and Variable Selection Via the Elastic Net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mol, C.; De Vito, E.; Rosasco, L. Elastic-net regularization in learning theory. J. Complex. 2009, 25, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lai, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shao, L.; Wu, J.; Xie, G.-S. Discriminative Elastic-Net Regularized Linear Regression. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navada, A.; Ansari, A.N.; Patil, S.; Sonkamble, B.A. Overview of use of decision tree algorithms in machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Control and System Graduate Research Colloquium; 2011; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.-Y.; Lu, Y. Decision tree methods: applications for classification and prediction. Shanghai Arch. psychiatry 2015, 27, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Mienye, I.D.; Jere, N. A Survey of Decision Trees: Concepts, Algorithms, and Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 86716–86727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Liang, X. An improved random forest based on the classification accuracy and correlation measurement of decision trees. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, A.; Cutler, D.R.; Stevens, J.R. Random Forests BT - Ensemble Machine Learning: Methods and Applications. In; Zhang, C., Ma, Y., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 157–175. ISBN 978-1-4419-9326-7. [Google Scholar]

- Natekin, A.; Knoll, A. Gradient boosting machines, a tutorial. Front. Neurorobot. 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, N.; Akhir, E.A.P.; Aziz, I.A.; Jaafar, J.; Hasan, M.H.; Abas, A.N.C. A Study on Gradient Boosting Algorithms for Development of AI Monitoring and Prediction Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI); 2020; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boldini, D.; Grisoni, F.; Kuhn, D.; Friedrich, L.; Sieber, S.A. Practical guidelines for the use of gradient boosting for molecular property prediction. J. Cheminform. 2023, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining.

- Raihan, M.J.; Khan, M.A.-M.; Kee, S.-H.; Nahid, A.-A. Detection of the chronic kidney disease using XGBoost classifier and explaining the influence of the attributes on the model using SHAP. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentéjac, C.; Csörgo, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, G. A comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 54, 1937–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.; Bell, M. XGBoost, A Novel Explainable AI Technique, in the Prediction of Myocardial Infarction: A UK Biobank Cohort Study. Clin. Med. Insights. Cardiol. 2022, 16, 11795468221133612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ni, M.; Zhang, C.; Liang, S.; Fang, S.; Li, R.; Tan, Z. Research and Application of AdaBoost Algorithm Based on SVM. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 8th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC); 2019; pp. 662–666. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. AdaBoost for Feature Selection, Classification and Its Relation with SVM, A Review. Phys. Procedia 2012, 25, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. CatBoost for big data: an interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.A.; Ridwan, R.L.; Muhammed, M.M.; Abdulaziz, R.O.; Saheed, G.A. Comparison of the CatBoost classifier with other machine learning methods. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Haque, I.; Lu, H.; Moni, M.A.; Gide, E. Comparative performance analysis of K-nearest neighbour (KNN) algorithm and its different variants for disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, R.K.; Uddin, M.N.; Uddin, M.A.; Aryal, S.; Khraisat, A. Enhancing K-nearest neighbor algorithm: a comprehensive review and performance analysis of modifications. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Introduction to machine learning: k-nearest neighbors. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Wang, H.; Bell, D.; Bi, Y.; Greer, K. KNN Model-Based Approach in Classification BT - On The Move to Meaningful Internet Systems 2003: CoopIS, DOA, and ODBASE.; Meersman, R., Tari, Z., Schmidt, D.C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 986–996. [Google Scholar]

- Uhrig, R.E. Introduction to artificial neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IECON ’95 - 21st Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics.

- Han, S.-H.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, S.; Youn, Y.C. Artificial Neural Network: Understanding the Basic Concepts without Mathematics. Dement. neurocognitive Disord. 2018, 17, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural networks 2015, 61, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, E.; Buscema, M. Introduction to artificial neural networks. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 19, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.; Goel, A.K.; Kumar, A. The role of artificial neural network and machine learning in utilizing spatial information. Spat. Inf. Res. 2023, 31, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deringer, V.L.; Bartók, A.P.; Bernstein, N.; Wilkins, D.M.; Ceriotti, M.; Csányi, G. Gaussian Process Regression for Materials and Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 10073–10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebden, M. Gaussian processes: A quick introduction. arXiv Prepr. arXiv1505.02965 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, E.; Speekenbrink, M.; Krause, A. A tutorial on Gaussian process regression: Modelling, exploring, and exploiting functions. J. Math. Psychol. 2018, 85, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, L.D. ChemDraw 8 ultra, windows and macintosh versions. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 2225–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, K.; Trainor, K.; Blazer, L.L.; Adams, J.J.; Sidhu, S.S.; Day, T.; Meiering, E.; Maier, J.K.X. A Descriptor Set for Quantitative Structure-property Relationship Prediction in Biologics. Mol. Inform. 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivakumar, M.; Parthasarathy, S.; Padmapriya, T. Trade-off between training and testing ratio in machine learning for medical image processing. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H.; Enda, K.; Shimizu, T.; Ishida, Y.; Ishizu, H.; Ise, K.; Tanaka, S.; Iwasaki, N. Machine Learning Algorithms: Prediction and Feature Selection for Clinical Refracture after Surgically Treated Fragility Fracture. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. Catboost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018; Vol. 2018-Decem, pp. 6638–6648. [Google Scholar]

- Jierula, A.; Wang, S.; Oh, T.M.; Wang, P. Study on accuracy metrics for evaluating the predictions of damage locations in deep piles using artificial neural networks with acoustic emission data. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossum, G.V.; Drake, F.L. Python Reference Manual. October 2006, 22, 9117–9129. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. Extracting spatial effects from machine learning model using local interpretation method: An example of SHAP and XGBoost. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 96, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Feature selection strategies: a comparative analysis of SHAP-value and importance-based methods. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Noor, S.; Javed, T.; Naseem, A.; Aslam, F.; AlQahtani, S.A.; Ahmad, N. XGBoost-enhanced ensemble model using discriminative hybrid features for the prediction of sumoylation sites. BioData Min. 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamathevan, J.; Clark, D.; Czodrowski, P.; Dunham, I.; Ferran, E.; Lee, G.; Li, B.; Madabhushi, A.; Shah, P.; Spitzer, M.; et al. Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Srivastava, G.; Ramanujam, J.; Brylinski, M. Insights from Augmented Data Integration and Strong Regularization in Drug Synergy Prediction with SynerGNet. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 1782–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaido, G.; Mienye, I.D.; Egbelowo, O.F.; Emmanuel, I.D.; Ogunleye, A.; Ogbuokiri, B.; Mienye, P.; Aruleba, K. Supervised machine learning in drug discovery and development: Algorithms, applications, challenges, and prospects. Mach. Learn. with Appl. 2024, 17, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lysenko, A.; Jia, S.; Boroevich, K.A.; Tsunoda, T. Advances in AI and machine learning for predictive medicine. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 69, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Xu, Q.; Yang, G.; Ding, J.; Pei, Q. Machine Learning for Prediction of Drug Concentrations: Application and Challenges. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, L.; Shukla, T.; Huang, X.; Ussery, D.W.; Wang, S. Machine Learning Methods in Drug Discovery. Molecules 2020, 25, 5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnuki, Y.; Akiyama, M.; Sakakibara, Y. Deep learning of multimodal networks with topological regularization for drug repositioning. J. Cheminform. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.Y.; Alsanousi, W.A.; Hamid, E.M.; Elbashir, M.K.; Al-Aidarous, K.M.; Mohammed, M.; Musa, M.E.M. An Efficient Deep Learning Approach for DNA-Binding Proteins Classification from Primary Sequences. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thedinga, K.; Herwig, R. A gradient tree boosting and network propagation derived pan-cancer survival network of the tumor microenvironment. iScience 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude, E.; Leclercq, M.; Thebault, P.; Droit, A.; Uricaru, R. Optimizing hybrid ensemble feature selection strategies for transcriptomic biomarker discovery in complex diseases. NAR Genomics Bioinforma. 2024, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Srivastav, S.; Shaffer, J.G.; Abraham, K.E.; Naandam, S.M.; Kakraba, S. Optimizing Parkinson’s Disease Prediction: A Comparative Analysis of Data Aggregation Methods Using Multiple Voice Recordings via an Automated Artificial Intelligence Pipeline. Data 2025, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.-R.; Ormazabal Arriagada, S.; Hsu, T.-C.; Lin, T.-W.; Lin, C. Exploiting common patterns in diverse cancer types via multi-task learning. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airlangga, G.; Liu, A. A Hybrid Gradient Boosting and Neural Network Model for Predicting Urban Happiness: Integrating Ensemble Learning with Deep Representation for Enhanced Accuracy. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Schlick, T. In silico evidence for DNA polymerase-β’s substrate-induced conformational change. Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 3088–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, C.B.; Golden, J.E.; Meibohm, B. Time to ‘Mind the Gap’ in novel small molecule drug discovery for direct-acting antivirals for SARS-CoV-2. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 50, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowicz-Piasecka, M.; Markiewicz, A.; Darłak, P.; Sikora, J.; Adla, S.K.; Bagina, S.; Huttunen, K.M. Current Chemical, Biological, and Physiological Views in the Development of Successful Brain-Targeted Pharmaceutics. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 942–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, E.Y.; Hellinga, H.W.; Beese, L.S. Structural factors that determine selectivity of a high fidelity DNA polymerase for deoxy-, dideoxy-, and ribonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 28215–28226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, W.A.; Wilson, S.H. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase β. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 2768–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, V.K.; Beard, W.A.; Shock, D.D.; Pedersen, L.C.; Wilson, S.H. Structures of DNA Polymerase β with Active-Site Mismatches Suggest a Transient Abasic Site Intermediate during Misincorporation. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabesoone, M.F.J.; Palmans, A.R.A.; Meijer, E.W. Solute-Solvent Interactions in Modern Physical Organic Chemistry: Supramolecular Polymers as a Muse. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 19781–19798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Meng, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Secundo, F.; Liu, Y. Enzyme stability and activity in non-aqueous reaction systems: A mini review. Catalysts 2016, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senhora, F.V.; Chi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Mirabella, L.; Tang, T.L.E.; Paulino, G.H. Machine learning for topology optimization: Physics-based learning through an independent training strategy. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 398, 115116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Wang, L.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, H.; Dong, J.; Yue, W.; Xia, H. Topology Optimization: A Review for Structural Designs Under Statics Problems. Materials (Basel). 2024, 17, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, B.; Taqvi, S.A.A.; Juchelkov, D.; Li, G.; Naqvi, S.R. Artificial intelligence-enhanced solubility predictions of greenhouse gases in ionic liquids: A review. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panapitiya, G.; Girard, M.; Hollas, A.; Sepulveda, J.; Murugesan, V.; Wang, W.; Saldanha, E. Evaluation of Deep Learning Architectures for Aqueous Solubility Prediction. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 15695–15710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, P.K.; Francis, S.A.J.; Barik, R.K.; Roy, D.S.; Saikia, M.J. Leveraging Shapley Additive Explanations for Feature Selection in Ensemble Models for Diabetes Prediction. Bioengineering 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, P.S.; Makeyev, E.V.; Butcher, S.J.; Bamford, D.H.; Stuart, D.I.; Grimes, J.M. The Structural Basis for RNA Specificity and Ca2+ Inhibition of an RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. Structure 2004, 12, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, A.; Agrawal, N.; Brezovsky, J. Impact of water models on the structure and dynamics of enzyme tunnels. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 3946–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeindlhofer, V.; Schröder, C. Computational solvation analysis of biomolecules in aqueous ionic liquid mixtures: From large flexible proteins to small rigid drugs. Biophys. Rev. 2018, 10, 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakraba, S., A.C. Yadem, and K.E. Abraham, Unraveling Protein Secrets: Machine Learning Unveils Novel Biologically Significant Associations Among Amino Acids, in Preprints. 2025, Preprints.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).