Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Characterization

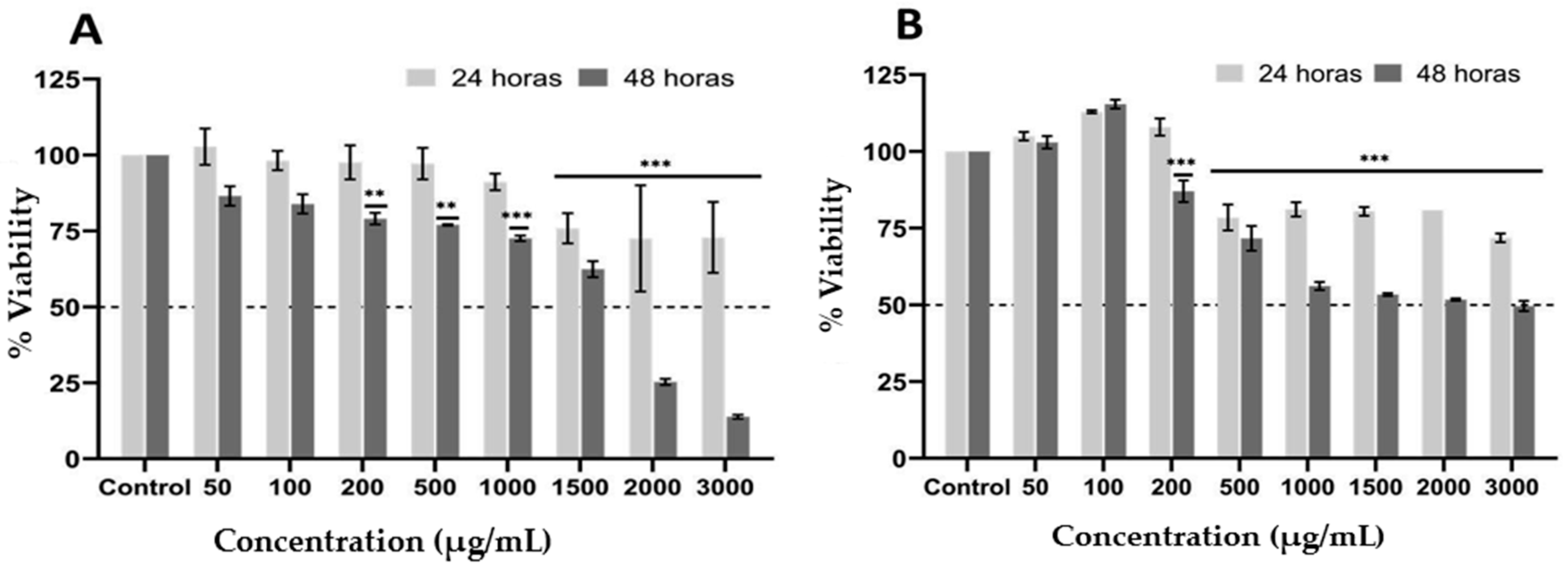

2.2. Effect of Ethanolic Extract from P. edulis Leaves on Cell Viability

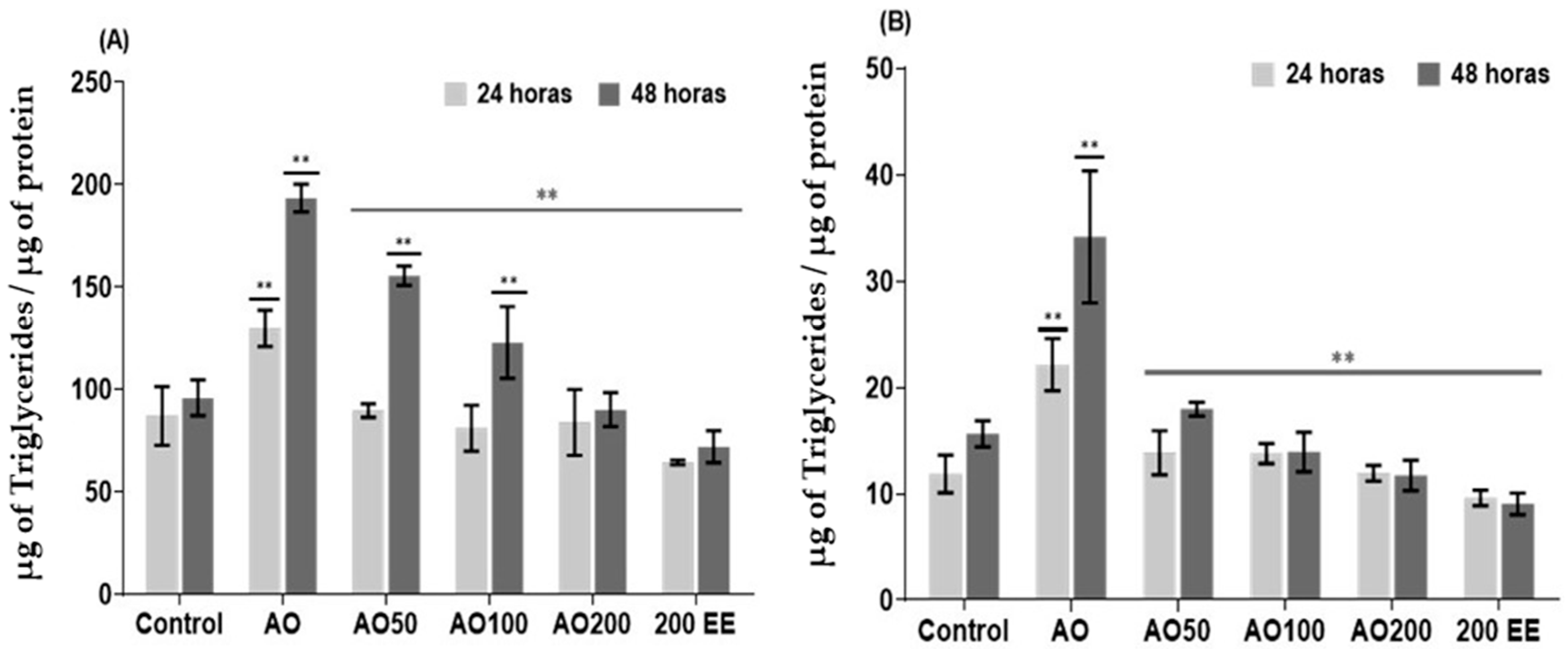

2.3. Effect of Ethanolic Extract from P. edulis Leaves on Intracellular and Extracellular Triglycerides

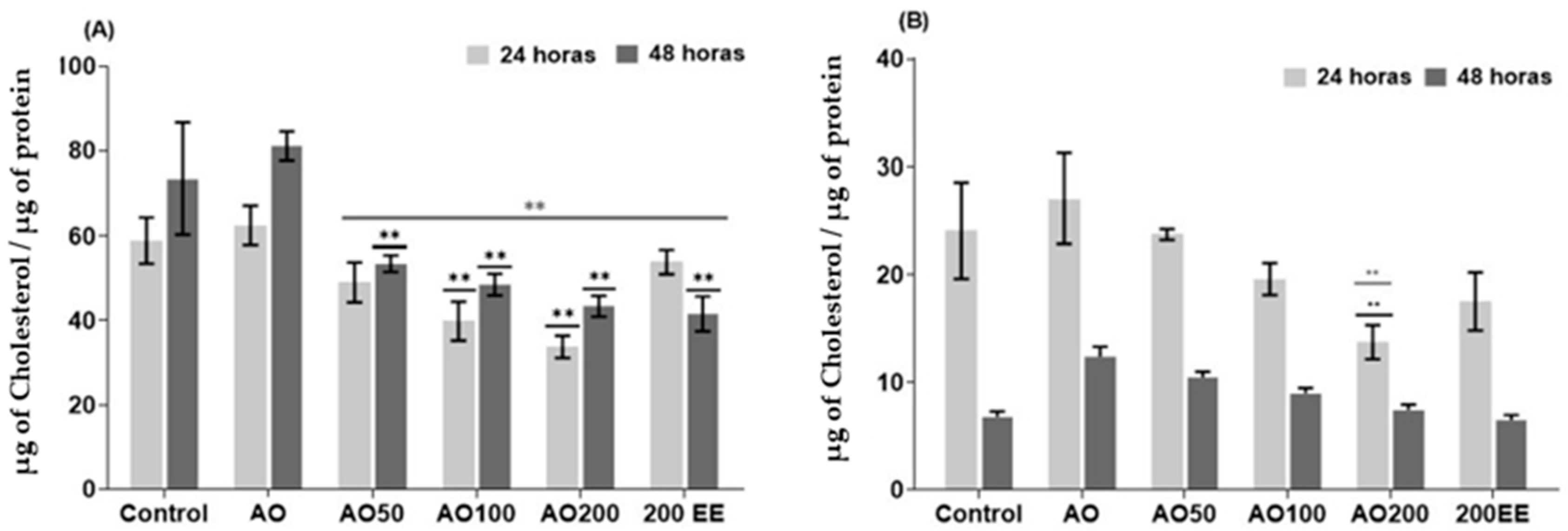

2.4. Effect of Ethanolic Extract from P. edulis Leaves on Intracellular and Extracellular Cholesterol

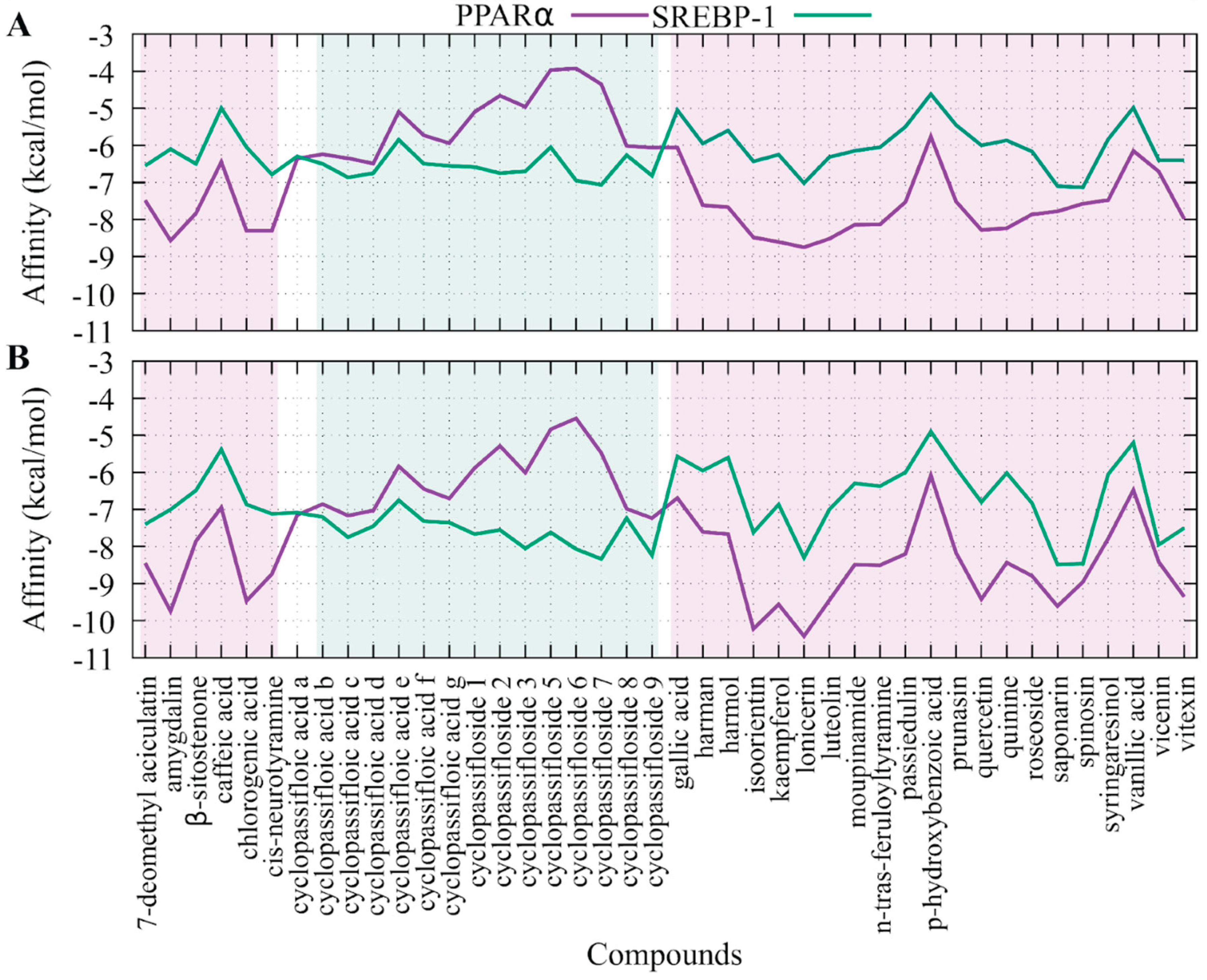

2.5. Molecular Coupling of the Compounds Presents in Passiflora edulis Against SREBP-1 and PPARα

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| PPARα | The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| SREBP-1 | The sterol regulatory element-binding protein type 1 |

| HepG2 | Cell line exhibiting epithelial-like morphology that was isolated from a hepatocellular carcinoma |

| WHO | The World Health Organization |

| SCD1 | Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 |

| FAS | Fatty acid synthase |

| ACC | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| EE | The ethanolic extract of P. edulis leaves |

| mg EAG/g DE | mg equivalent of gallic acid/g of dry extract |

| mg EC/g ES | mg equivalent of caffeine/g of dry extract |

| mgEQ | mg equivalent |

| HFF | Fibroblast cell that was isolated from the foreskin of a donor |

| AO | Oleic acid |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| CT | Cholesterol |

| IC50 | Medium Inhibitory Concentration |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase pathway |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| CYP4A1 | Enzyme cytochrome P450 4A1 |

References

- Younossi ZM, Rinella ME, Sanyal AJ, Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Goodman Z, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: assessment of variability in pathologic interpretations. Mod Pathol. 2020, 33, 776–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter T, Rinella M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 2020: the state of the disease. Gastroenterology, 2020; 1;158(7):1851-64.

- Wang W, Xu J, Fang H, Li Z, Li M. Advances and challenges in medicinal plant breeding. Plant Sci, 1: 301, 1105.

- Zhou Y, Li Y, Wang Y, Wang D, Li X, Zhang X, et al. CRISPR-Cas gene editing technology and its application prospect in medicinal plants. Chin Med. 2022, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugumira R, Tafire H, Vancoillie F, Ssepuuya G, Van Loey A. Nutrient and phytochemical composition of nine African leafy vegetables: a comparative study. Foods. 2025, 14, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M. Prevention of metabolic syndrome by phytochemicals and vitamin D. Biomed Res Int, 2022, 2022 9917154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Omari N, Bakrim S, Khalid A, Abdalla AN, Iesa MAM, El Kadri K, et al. Unveiling the molecular mechanisms: dietary phytosterols as guardians against cardiovascular diseases. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2024, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan Y, Wang M, Yang K. PPAR modulators as current and potential cancer treatments. Front Oncol, 2021: 11, 5999.

- Todisco S, Santarsiero A, Convertini P. PPAR Alpha as a Metabolic Modulator of the Liver: Role in the Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Biology. 2022, 11, 792. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, GC. Plasma free fatty acid concentration as a modifiable risk factor for metabolic disease. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou Y, Geng F, Guo D. Lipid metabolism in glioblastoma: from de novo synthesis to storage. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Ferré P, Phan F, Foufelle F. SREBP-1c and lipogenesis in the liver: an update. Biochem J. 2021, 478, 3723–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of SCAP/SREBP as central regulators of lipid metabolism in hepatic steatosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros N, Almeida D, Lima J. In vitro antioxidant activity of Passiflora alata extract by different kinds of treatment on rat liver. Curr Bioact Compd 2018; 14:21–5.

- Smruthi R, Divya M, Archana K, Maddaly R. The active compounds of Passiflora spp. and their potential medicinal uses from both in vitro and in vivo evidence. J Adv Biomed Pharm Sci 2020; 4:45–55.

- Smilin G, Abbirami E, Sivasudha T, Ruckmani K. Passiflora caerulea L. fruit extract and its metabolites ameliorate epileptic seizure, cognitive deficit and oxidative stress in pilocarpine-induced epileptic mice. Metab Brain Dis 2020; 35:159–73.

- Dharmasiri PGNH, Ranasinghe P, Jayasooriya PT, Samarakoon KW. Antioxidant, anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory activities of Passiflora foetida grown in Sri Lanka. Trop Agric Res. 2024, 35, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasiri PGNH, Ranasinghe P, Jayasooriya PT, Samarakoon KW. Antioxidant, anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory activities of Passiflora foetida grown in Sri Lanka. Trop Agric Res. 2024, 35, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael HS, Mohammed NB, Ponnusamy S, Edward GN. A folk medicine: Passiflora incarnata L. phytochemical profile with antioxidant potency. Turk J Pharm Sci. 2022, 19, 287–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu Y, Jiao L. A new C-glycosyl flavone and a new neolignan glycoside from Passiflora edulis Sims peel. Nat Prod Res 2018; 32:2312–8.

- Silva LNS, Oliveira DM, Oliveira AS, Cunha VMN, Carvalho FAA, Costa JP, et al. Hypotensive and vasorelaxant effects of ethanolic extract from Passiflora edulis Sims leaves. J Ethnopharmacol 2017; 204:127–32. [CrossRef]

- Nerdy N, Ritarwan K. Hepatoprotective activity and nephroprotective activity of peel extract from three varieties of the passion fruit (Passiflora sp.) in the albino rat. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019, 7, 536–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jako P, Chonpathompikunlert P, Malakul W, Tunsophon S. Passiflora edulis extract ameliorates HFD-induced hepatic steatosis mediated through Nrf2 and IRS-1 activation, NFκB suppression, and hepatic lipid metabolism and bile acid modulation in obese rats. Biomed Pharmacother, 4752.

- Preetha P, Kamalabai S, Jayachandran S. Qualitative and quantitative phytochemical screening of Vitex negundo L. extract using chromatographic and spectroscopic methods. Qualitative and quantitative phytochemical screening of Vitex negundo L. extract using chromatographic and spectroscopic methods. Nat Volat Essent Oils J. 2021, 11949–61. [Google Scholar]

- Aguillón J, Arango S, Uribe F, Loango N. Cytotoxic and apoptotic activity of extracts from leaves and juice of Passiflora edulis. J Liver Res Disord Ther. 2018, 4, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães SF, Lima IM, Modolo LV. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of parts of Passiflora edulis as a function of plant developmental stage. Acta Bot Bras. 2020, 34, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Carmo L, Martins M, Magalhães R, Júnior M, Macedo A. Passiflora edulis leaf aqueous extract ameliorates intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction and reverts inflammatory parameters in Caco-2 cells monolayer. Food Res Int, 9162.

- Pietrzyk N, Zaklos-Szyda M, Kołopulus L. Fruit phenolic compounds protect against FFA-induced steatosis of HepG2 cells via AMPK pathway. J Funct Foods, 2021: 80, 1044.

- Liu Y, Zhai T, Yu Q, Zhu J, Chen Y. Effect of high exposure of chlorogenic acid on lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in oleic acid-treated HepG2 cells. Chin Herb Med. 2018, 10, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, Song C, Liu J, Chen F, Zhu Y, Fang X, et al. Chlorogenic acid modulates autophagy by inhibiting the activity of ALKBH5 demethylase, thereby ameliorating hepatic steatosis. J Agric Food Chem. 2024, 72, 19257–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Jiang Y. Chlorogenic acid and its isomers attenuate NAFLD by mitigating lipid accumulation in oleic acid-induced HepG2 cells and high-fat diet-fed zebrafish. J Food Biochem. 2024, 48, e13958. [Google Scholar]

- Yan F, Zheng X. Anthocyanin-rich mulberry fruit improves insulin resistance and protects hepatocytes against oxidative stress during hyperglycemia by regulating AMPK/ACC/mTOR pathway. J Funct Foods, 2017; 30:270–81.

- Zhang Y, Pan H, Ye X, Chen S. Proanthocyanidins from Chinese bayberry leaves reduce obesity and associated metabolic disorders in high-fat diet-induced obese mice through a combination of AMPK activation and alteration in gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 2295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Wang C, Jin X, Hou Y, Zheng L. Optimization of extraction technology of total flavonoids from Passiflora edulis peel by ultrasonic assisted with complex enzyme and its antioxidant activity. Sci Technol Food Ind. 2022, 43, 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulou M, Katsaros I, Vailas M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the role of quercetin and its therapeutic implications. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Sun R, Li Z. Luteolin alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats via restoration of intestinal mucosal barrier and microbiota involving the gut-liver axis. Arch Biochem Biophys, 1: 711, 1090.

- Saravanan S, Parimelazhagan T. In vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-diabetic properties of polyphenols from Passiflora ligularis Juss. fruit pulp. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2014, 3, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Li W, Liao W, Hao Q, Tang D, Wang D, Wang Y, Ge G. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and ameliorates intestinal immunity in mice fed a high-fat diet. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9924–9935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang Y, Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Lu Y, et al. Tannic acid attenuates hepatic oxidative stress, apoptosis and inflammation in a high-fat diet-induced NAFLD rat model. Exp Ther Med. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Mesquita LM, de Souza EL, de Oliveira Lima E, de Freitas Araújo AA, de Almeida RN. Passiflora edulis: an insight into current researches on pharmacology and phytochemistry. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11:617. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez L, Alvarez A, Murillo E, Guerra C, Mendez J. Potential uses of the peel and seed of Passiflora edulis f. edulis Sims (gulupa) based on chemical characterization, antioxidant, and antihypertensive properties. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019, 12, 104–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Liu C, Zhang G. Harmine alleviates LPS-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting CSF3-mediated MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway. Respir Res. 2023, 24, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Wang Y, Li X, Liu C, Zhang G. Alkaloids from traditional Chinese medicine against hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanisms and perspectives. Biomed Pharmacother, 1: 137, 1113. [CrossRef]

- Sun S, Zhong H, Zhao Y. Indole alkaloids of Alstonia scholaris (L.) R. Br. alleviate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet-fed mice. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2022, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Villada Ramos JA, Aguillón Osma J, Restrepo Cortes B, Loango Chamarro N, Maldonado Celis ME. Identification of potential bioactive compounds of Passiflora edulis leaf extract against colon adenocarcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Rep 2023; 34:101453. [CrossRef]

- Maëlle Carraz, Cédric Lavergne, Valérie Jullian, Michel Wright, Jean Edouard Gairin, Mercedes Gonzales de la Cruz, Geneviève Bourdy. Antiproliferative activity and phenotypic modification induced by selected Peruvian medicinal plants on human hepatocellular carcinoma Hep3B cells, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2015, 166:185-199. doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.028.

- Amaral G, Gomes V, Andrade N. Cytotoxic, antitumor and toxicological profile of Passiflora alata leaf extract. Molecules. 2020, 25, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui W, Chen S, Hu Q. Quantification and mechanisms of oleic acidinduced steatosis in HepG2 cells. American journal of translational research. 2010, 2, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Zhang R, Yang Z, Zhang K, Xing J. Mechanism of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Important role of lipid metabolism. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2024, 12, 815–826. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhao L, Wang D, Huo Y, Ji B. Anthocyanin-rich extracts from blackberry, wild blueberry, strawberry, and chokeberry: antioxidant activity and inhibitory effect on oleic acid-induce d hepatic steatosis in vitro. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocaadam B, Ozgurtas T, Ozcelik AO, Sezgin GC. Curcumin attenuates hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet-fed rats and oleic acid-treated HepG2 cells. Phytother Res. 2021, 35, 4382–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park M, Yoo J, Lee Y, Lee J. Lonicera caerulea extract attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in free fatty acid-induced HepG2 hepatocytes and in high fat diet-fed mice. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 494.

- Le, H. , Choi, J., Jun, S. Ethanol extract of Liriope platyphylla root attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet-induced obese mice via regulation of lipogenesis and lipid uptake. Nutrients, 2021, 13, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin Y, Gao L, Lin H. improves non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in db/db mice by inhibition of liver X receptor activation to down-regulate expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2017, 482, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Wu P, Yang B. “et al”. Kaempferol prevents the progression from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway in oleic acid-induced HepG2 cells and high-fat diet-induced rats. Journal of Functional Foods. 2021, 85, 104655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Jeong E, Jo S, Park J, Kim J. Effects of light-controlled germination on saponarin content and lipid accumulation in HepG2 and 3T3-L1 cells using barley sprout extracts. Molecules. 2020, 25, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han B, Yu Q, Yang L, Shen Y, Wang X. Kaempferol induces autophagic cell death of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via activating AMPK signaling. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 86227–86239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Liu R, Shen Z, Cai G. Luteolin and lycopene protect against NAFLD via regulation of Sirt1/AMPK signaling. Life Sci, 2020: 256, 1179.

- Chang Y, Chen Y, Huang W, Liou C. Fucoxanthin attenuates fatty acid-induced lipid accumulation in FL83B hepatocytes through regulated Sirt1/AMPK signaling pathway. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2018, 495, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie F, Ding J, Hu N. “et al”. Kaempferol and kaempferide attenuate oleic acid-induced lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in HepG2 cells. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021, 22, 8847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguillón J, Maldonado M, Loango N. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of ethanolic and aqueous extracts from leaves and fruit juice of Passiflora edulis. Perspect Nutr Humana. 2013, 15, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz O, Torres G, Nuñez J. New insights into the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent interaction with sugars during total polyphenol quantification. Rev Cienc Quím Biol. 2017, 20, 23–8. [Google Scholar]

- Armentano M, Bisaccia B, Miglionico R. Antioxidant and proapoptotic activities of Sclerocarya birrea [(A. Rich.) Hochst.] Methanolic root extract on the hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2. BioMed Research International.

- López X, Taramuel A, Arboleda C, Segura F, Restrepo L. Comparación de métodos que utilizan ácido sulfúrico para la determinación de azucares totales. Revista cubana de Química, 2017; 29: 180-198.

- Prajapati D, Makvana A, Patel M, Chaudhary R, Patel R. Spectrophotometric method for the determination of total alkaloids in selected plant parts. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2024, 13, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichai V, Kirtikara K. Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay for cytotoxicity screening. Nature protocols, 2006, 1, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira FS, Pimentel LL, Vidigal SSMP, Azevedo-Silva J, Pintado ME, Rodríguez-Alcalá LM. Differential lipid accumulation on HepG2 cells triggered by palmitic and linoleic fatty acids exposure. Molecules. 2023, 28, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J. The Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay for Protein Quantitation. The Protein Protocols Handbook. 2009, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh G, Dyer W. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian journal of biochemistry and physiology. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama T, Toyota K, Waku T. “et al”. Adaptability and selectivity of human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) pan agonists revealed from crystal structures. Acta Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography. 2009, 65, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artis R, Lin J, Zhang C. “et al”. Scaffold-based discovery of indeglitazar, a PPAR pan-active anti-diabetic agent. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008. 106(1), 262–267.

- Jin L, Lin S, Rong H. “et al”. Structural Basis for iloprost as a dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α/δ agonist. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011, 286, 31473–31479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara N, Oyama, T, Tomioka D. “et al”. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) have multiple binding points that accommodate ligands in various conformations: Phenylpropanoic acid-type PPAR ligands bind to PPAR in different conformations, depending on the subtype. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2012. 55(2), 893–902.

- Kamata S, Oyama T, Saito K. “et al”. PPARα ligand-binding domain structures with endogenous fatty acids and fibrates. iScience. 2020, 23, 101727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli D, Cerchia C, Montanari R. Structural basis for PPAR partial or full activation revealed by a novel ligand binding mode. Scientific Reports. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Cronet P, Petersen W, Folmer R. “et al”. Structure of the PPARα and -γ ligand binding domain in complex with AZ 242; Ligand selectivity and agonist activation in the PPAR family. Structure. 2001, 9, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oon H, Hae S, Kim. “et al”. Design and synthesis of oxime ethers of α-acyl-β-phenylpropanoic acids as PPAR dual agonists. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2007, 17, 937–941. [Google Scholar]

- Parraga A, Bellsolell L, Ferré-D’Amaré A, Burley K. Co-crystal structure of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1a at 2.3 å resolution. Structure. 1998, 6, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris M, Huey R, Lindstrom W. “et al”. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott O, Olson J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry.

- Koes R, Baumgartner P, Camacho J. Lessons learned in empirical scoring with smina from the CSAR 2011 Benchmarking Exercise. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2013, 53, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metabolite type | Total metabolite content (mgEQ) |

|---|---|

| Phenols | 235.7 ± 9.7 |

| Polysaccharides | 221.9 ± 16.4 |

| Flavonoids | 182.4 ± 7.9 |

| Tannins | 45.1 ± 3.5 |

| Alkaloids | 8.3 ± 1.1 |

| Compound | PPARα | SREBP-1 | MIX |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7deomethylaciculatin | 16.70 | 13 | 14 |

| Amygdalin | 5.19 | 24 | 13.5 |

| chlorogenic acid | 8.38 | 27 | 16.5 |

| cisnfeuroyltyramine | 11.57 | 14 | 12 |

| cyclopassifloic acid c | 27.99 | 7.5 | 17 |

| cyclopassifloicacid d | 27.18 | 11.5 | 18 |

| cyclopassifloside1 | 35.27 | 11 | 23 |

| cyclopassifloside3 | 32.7 | 8.5 | 21 |

| cyclopassifloside6 | 40.85 | 5.5 | 23.5 |

| cyclopassifloside7 | 39.15 | 3 | 22 |

| cyclopassifloside9 | 27.05 | 6.5 | 15.5 |

| Isoorientin | 5.05 | 15 | 8 |

| Kaempferol | 6.85 | 24 | 15 |

| Lonicerín | 5.4 | 4.5 | 3.5 |

| Luteolin | 7.05 | 22 | 14 |

| Quercetin | 8.95 | 29.5 | 18.5 |

| Saponarin | 10.85 | 1 | 4.5 |

| Spinosin | 12.9 | 2 | 6.5 |

| Vitexin | 11.2 | 18 | 13.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).