1. Introduction

Mushroom production has been a vital industry in global agriculture due to its high nutrient content, sustainability, and smaller environmental footprint compared to other agricultural methods. It holds significant value as a sustainable solution to aid poverty (SDG 1), hunger (SDG 2), and malnutrition while also contributing to good health and well-being (SDG 3) [

1].

Pleurotus ostreatus is an edible and therapeutic mushroom that could be a good protein, dietary fibers, and vitamins of the B complex and essential minerals intake. The bioactive compounds, such as -glucans and lovastatin have been attributed to its fame. These have been associated with cholesterol-lowering, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory effects as recognized in the Mushrooms and Health Summit Proceedings [

2]. In the Philippines, mushroom cultivation offers both health and economic benefits, serving as a nutritious food source and a promising avenue for environmentally friendly rural income. BEAM Organization, among others, has been active in nurturing the mushroom industry in Luzon, involving about seventy willing and participating members. For this field to be sustainable, members from various disciplines must come in, i.e., cultivation methods will be addressed by natural scientists, marketing by business professionals, and online marketing and distribution would be enabled by IT specialists. This becomes an ideal way of achieving SDG 8, which is Decent Work and Economic Growth, opening the way for income generation, job opportunities, and community development [

3].

Mushroom farming is an excellent source of easy livelihood as well as sustainable development. However, despite promising prospects, mushroom farming is not popular in the country, and this is majorly because of various systemic issues and challenges [

4], many of which include such that there is no good access to quality spawns and compost; other kinds of minimal government support with technical assistance are there; cold-chain and post-harvest infrastructural facilities so little; and finally, emerging public awareness on the nutritional and economical significance attached to mushrooms [

5]. Other parameters which discourage mushroom farming are the intensive labor factors involved in it, seasonal crop production as well as limited access to finance and institutional resources. These conditions really have limited access to resources for rural farmers and directly affect the progress of a nation towards achieving SDG 9 – Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure and SDG 10 – Reduced Inequalities.

In terms of yield performance, specific environmental conditions are required for successful production of Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom). Such parameters as temperature should range between 20-30 °C, relative humidity between 70-90%, moisture content of the substrate 50-70%, and good aeration to prevent accumulation of carbon dioxide [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Any minor variation from these parameters may result in stunted growth, contamination, low yield, or inadequate quality [

10]. More traditional ways of keeping these conditions rely heavily on manual tinkering and monitoring, which could be more time-wasting, labor-intensive, and subject to human faults [

11]. An increasing study involving applications of smart farming technologies based on controlled environment agriculture attests to several advancements in research. For example, production efficiency was improved by the application of climate controllers for oyster mushroom production [

12]. The IoT system for real-time environment monitoring in the greenhouse shows improved accuracy and less reliance on labor [

13]. Two corresponding IoT- based projects applied similar methodologies: one developed precision irrigation through soil moisture sensors and computerized sprinklers for organic farming; the other monitored temperature and humidity for poultry egg incubation to improve hatchability [

14,

15]. The systems, in general, collect the required information on temperature, humidity, and soil moisture through sensors, which are processed through microcontrollers, which in turn actuate exhaust fans, water pumps, humidifiers, or heaters to control the environment.

To mitigate these challenges, this study proposed smart farming technology through an IoT-based system enabling automated monitoring and control of temperature, humidity, substrate moisture, exhaust, and ventilation. The research adopts a systematic approach, integrating environmental monitoring sensors for real-time data acquisition and microcontrollers that process the data while using actuators (such as fans, sprinklers, and pumps) for dynamic maintenance of the optimal condition. The data obtained was transferred to a cloud on which graphical and visual representation of data were automatically created available for analysis. This closed-loop, data-centric system lessens human error and yields inconsistency, aids in the sustainability of rural mushroom cultivation, expands the capability of electronic management systems in agriculture, improves food security, and supports the cause of global mushroom cultivation.

2. Materials and Methods

The foundation of an effective system lies in clearly defining its requirements before development. This research was conducted in phases, as shown in

Table 1, beginning with data collection through a literature review, field study, and expert advice to identify the environmental factors necessary for mushroom cultivation, including ideal temperatures, humidity levels, and substrate moisture levels. One notable reference in this phase was the Solar-Powered Automated Modular Mushroom Growing House, a joint R&D effort by the DOST-NCR and Rizal Technological University (RTU), which was donated to the Pasig City Government under the Community Empowerment through Science and Technology (CEST) program [

15]. This project supported the development of this study’s IoT-based system by demonstrating the effectiveness of automated environmental control in real-world mushroom production.

2.1. Data Gathering

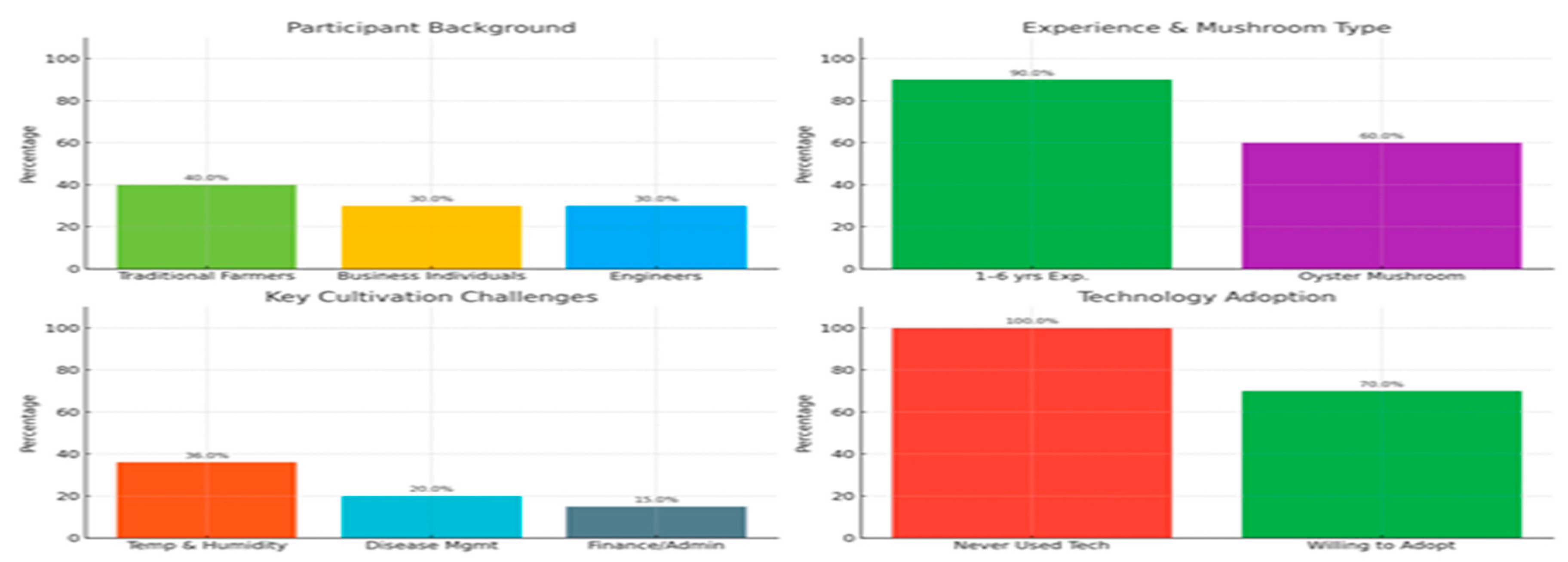

The data-gathering phase involved reviewing related literature and existing systems, as well as conducting interviews and surveys in mushroom farms across Silang, Cavite. These activities provided critical insights into local cultivation practices and technical requirements. Ten respondents were surveyed, as shown in

Figure 1, comprising 40% traditional farmers, 30% business owners, and 30% engineers, with the majority having 1–6 years of experience. Oyster mushroom was the most cultivated species (60%). The primary challenges reported included maintaining temperature and humidity (36%), managing plant diseases (20%), and system cost and administration (15%). Although none had used electronic systems before, 70% showed interest in whether the system was affordable and easy to use. Concerns included cost (30%), complexity (26.7%), and reliability.

Field tests revealed that manual intervention in mushroom farms typically resulted in a 30- to 45-minute delay, which led to oscillating environmental conditions. Logs and charts were used to identify key factors, including humidity, temperature, and moisture content.

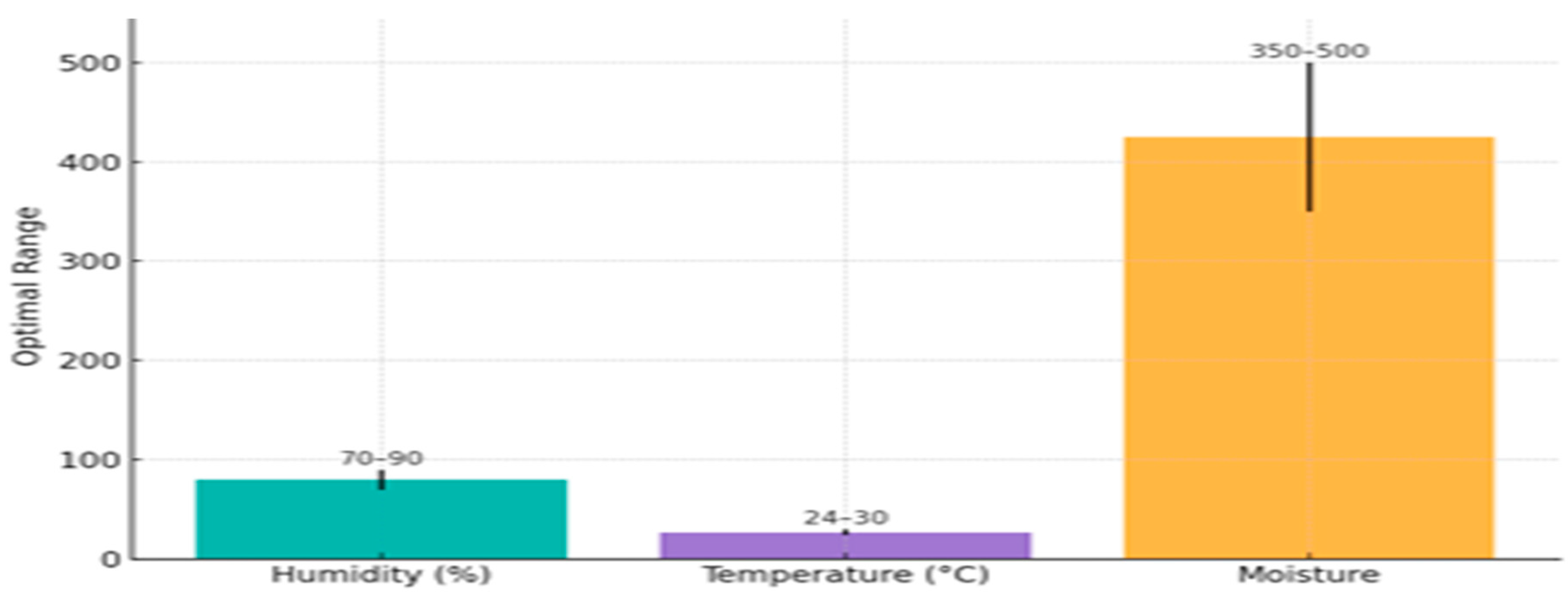

Interviews also emphasized these factors as key parameters, including 70–90% humidity, a temperature of 24–30°C, and 350–500 ppm moisture, as illustrated in

Figure 2. These results had a direct impact on the system's performance requirements, and therefore, an automated monitoring and control system was implemented, which reduced response time to a few seconds.

Field tests revealed that manual intervention in mushroom farms typically resulted in a 30- to 45-minute delay, which led to oscillating environmental conditions. Logs and charts were used to identify key factors, including humidity, temperature, and moisture content. Interviews also emphasized these factors as key parameters, including 70–90% humidity, a temperature range of 24–30°C, and a moisture level of 350–500 ppm, as illustrated in

Figure 2. These results had a direct impact on the system's performance requirements, and therefore, an automated monitoring and control system was implemented, which reduced response time to a few seconds.

2.2. Design and Development

The research used developmental and experimental design methodology. It was based on the Research and Development (R&D) process, which led the researcher from problem identification in mushroom growth to the development and testing of a technological solution.

Figure 3.

System Architecture.

Figure 3.

System Architecture.

The system architecture depicts the actual world representation and key components of the solar-powered IoT-based mushroom chamber. The Sensing–Actuation–Power Management Tier is integrated into the Microcontroller Unit (MCU), which serves as the control center of the system. The sensing element includes temperature, humidity, and soil moisture sensors utilized to gather environmental information within the chamber. Actuation involves controlling equipment such as fans, pumps, and lighting systems to manage microclimate conditions. Power management encompasses solar panels, charge controllers, and a 12V power supply, ensuring uninterrupted performance. The Wi-Fi module supports wireless data transmission to the cloud for real-time monitoring. A display unit provides users with a visual representation of data collected directly from the chamber. Users can access and control the system remotely using cloud-based services. The system is created based on an incremental development model, which allows for the step-by-step fulfillment of the entire functionality through the gradual integration of both hardware and software components.

Mushroom Chamber

A fruiting chamber is a controlled environment that mimics ideal conditions—specifically, humidity, temperature, and air circulation—for the development of mushrooms. Without control, mushrooms can show poor or abnormal growth. A well-designed chamber is, therefore, crucial for healthy growth and optimal yield [

16]. The chamber used in this research is a closed chamber (1 m × 1.5 m × 1 m) equipped with overhead sprinklers, exhaust, and ventilation fans, all designed to maintain key environmental parameters. Reflective insulation retains heat and humidity.

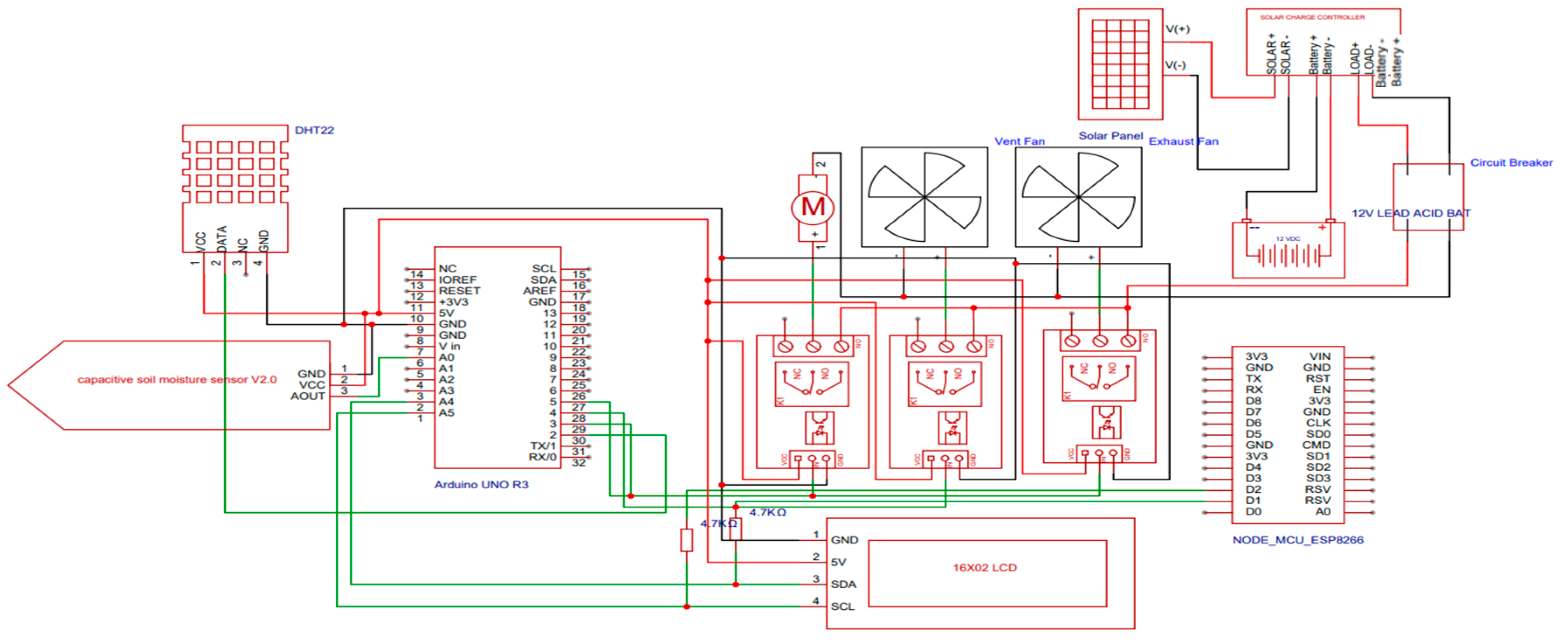

Microcontroller Unit

The heart of the system is an Arduino Uno R3, connected to a DHT22 sensor (temperature and humidity) and a capacitive moisture sensor. The microcontroller triggers actuators automatically upon setting thresholds [

17]. The sprinkler runs when the humidity is below 70% and sufficient time has elapsed since the last run or when the substrate moisture is too high. The ventilation fan operates at temperatures above 29°C, and the exhaust fan activates when the temperature exceeds 32°C or the humidity reaches 90%. Such logic attains accurate, real-time climate adjustment with little human intervention.

Wi-Fi Module

An ESP8266 module provides wireless data transfer to the ThingSpeak cloud platform [

18]. It includes sensor readings (e.g., temperature, humidity, and moisture) at scheduled intervals, which can be remotely monitored, historically recorded, and analyzed on any internet-connected device. Separation of Wi-Fi tasks from the microcontroller results in a more modular and convenient system.

Power System

For off-grid use and sustainability, the system also includes a mono-crystalline photovoltaic panel as the primary source of power [

19]. A solar charge controller ensures energy flow to prevent battery overcharge or draining. A 12V deep-cycle battery is used to store the energy for use during instances of zero sunlight [

20]. This ensures continuous 24/7 use, which is especially useful in rural areas with erratic electricity supply access to the conventional power grid. Consequently, the system is available 24/7, making it highly beneficial in rural or off-grid areas where a consistent electrical supply is a problem.

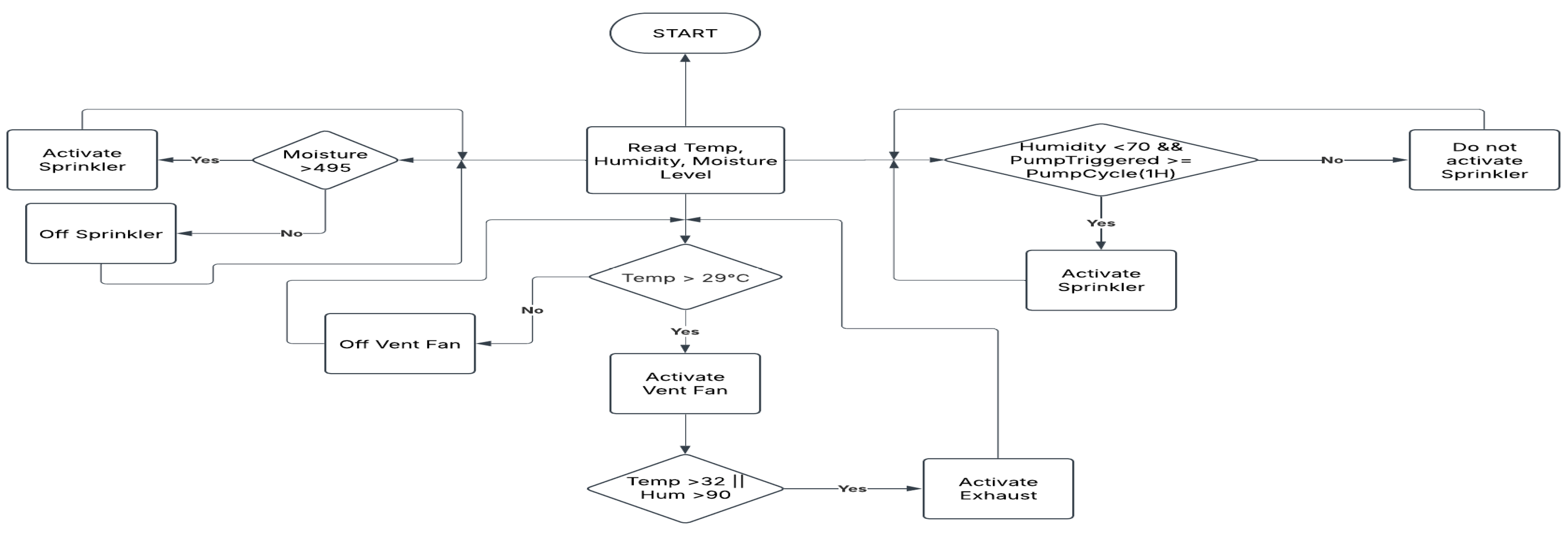

The flowchart shown in

Figure 4 illustrates the interaction between all units within the automated microclimate control system. It starts by gathering real-time information regarding the environment, temperature, humidity, and substrate moisture. The system then makes decisions based on pre-established threshold levels. When the humidity level is less than 70% and at least an hour has elapsed since the last pump, the sprinkler system is activated. Additionally, when the substrate moisture exceeds 495, the sprinkler also becomes activated. To regulate temperature, the ventilation fan is activated when the temperature exceeds 29°C. When the condition worsens, such as when the temperature exceeds 32°C or the humidity exceeds 90%, the exhaust fan is activated to release excess heat and moisture. The flowchart enables the system to respond promptly to environmental changes and maintain optimal conditions for mushroom growth with minimal human intervention.

The microclimate for mushroom farming using IoT employs a combination of electronic devices to sense and control environmental factors. The system schematic diagram shown in

Figure 5 illustrates the connection of the devices, demonstrating how they cooperate to automate the process of growing mushrooms.

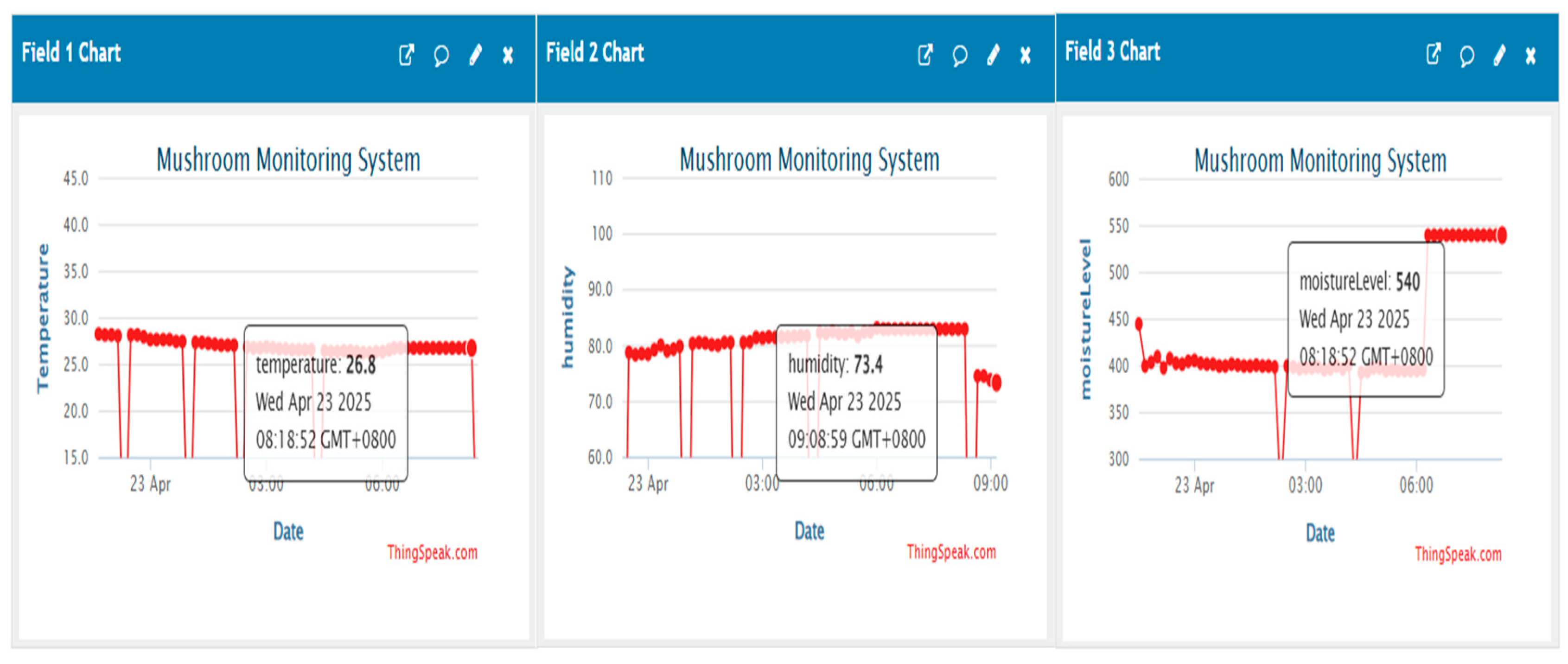

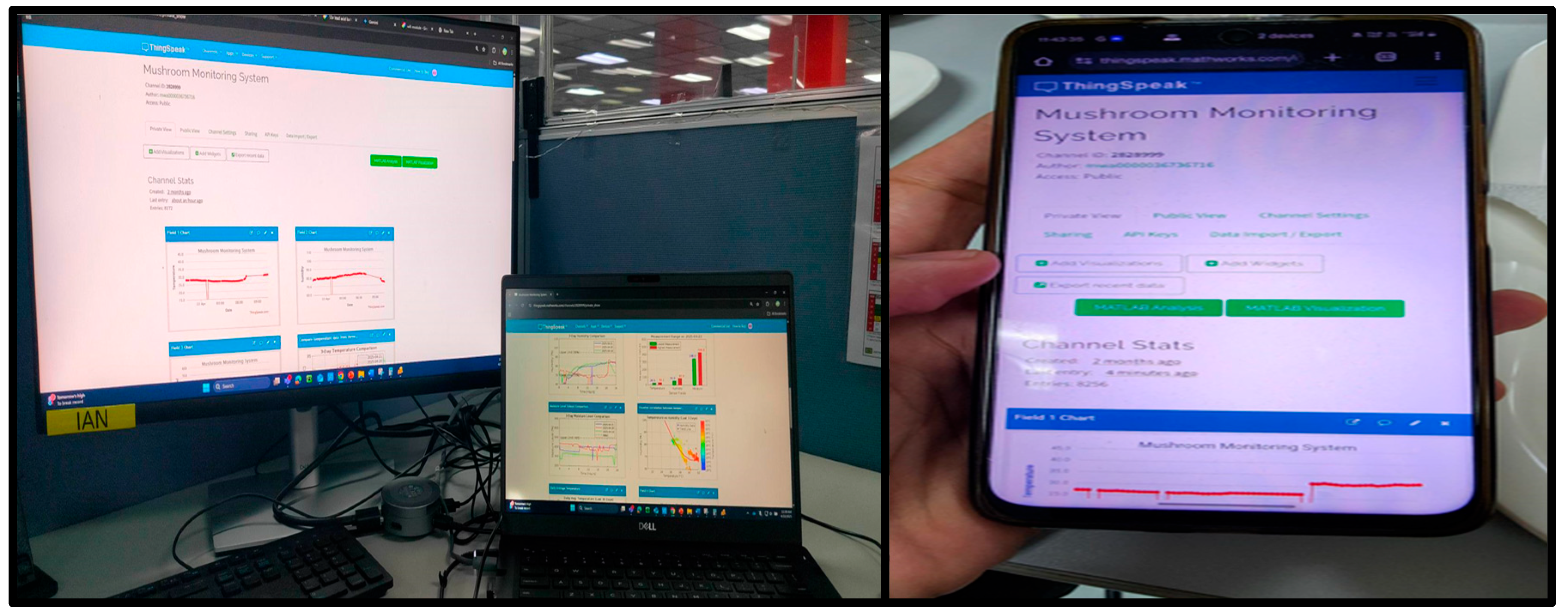

Figure 6 shows the ThingSpeak graphical user interface (GUI), which displays updated temperature, humidity, and moisture readings every 10 minutes. It automatically generates a three-day comparison of these parameters, including daily averages, as well as high and low values. The interface also indicates the status of the actuators, enabling improved monitoring and analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

A comprehensive eight-week simulation was conducted using oyster mushrooms as the test species. The system was installed in a controlled setup where sensors collected environmental data at 10-minute intervals. The automation was programmed to respond to changes in humidity, temperature, and substrate moisture.

Table 2.

Environmental Condition Monitored by Sensors.

Table 2.

Environmental Condition Monitored by Sensors.

| Condition |

Sensor |

Function |

| Temperature |

DHT22 |

Track temperature between 24-30°C |

| Humidity |

DHT22 |

Keeps humidity between 70-90% |

| Soil Moisture |

Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensor |

Maintains Moisture threshold lower than 495 |

| Data Logging |

ThingSpeak Flatform |

Captures real-time sensor feed data and actuator trigger automation |

Mushroom growth conditions were program to regulate rules for optimum internal conditions. If the temperature exceeded 30°C or the humidity fell below 70%, then the fan will turn on to create the correct airflow and to have the proper temperatures. If the moisture level of the substrate fell below 495, then the water pump will activate, thus maintaining the moisture necessary for healthy mycelium growth. In addition, the exhaust fan will activate when humidity exceeds 90%, thereby preventing mold growth. Thus, the entire process of automating these systems would automatically switch operation depending on the need. Data records indicated that the system was running well on repairs every 2 to 10 minutes for environmental readjustments.

Figure 7.

Real-Time Temperature, Humidity, and Moisture Logging on ThingSpeak.

Figure 7.

Real-Time Temperature, Humidity, and Moisture Logging on ThingSpeak.

Over a two-week period, the automated system's efficiency was drained by being compared against a manual growing system.

Table 3 and

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show that the mushrooms had begun to grow in the automated system as early as the 4th Day, while no growth was recorded in the manual system during the same period. The automated mushrooms measured 7.5 cm on Day 5 and continued their steady growth so that by Day 6 they had reached 20.3 cm and harvest size by Day 7. During the manual operation, the first growth recorded was on Day 9, measuring 4.5 cm, while the first harvesting was on Day 11. The last harvesting was recorded on Day 14 from the manual setup, measuring between 7.6 cm and 15.2 cm. Within the two-week period, the automated system was able to harvest 4 times with an average weight of 352.5 grams, while the manual system harvested one time and yielded 136 grams; it thus proved beyond doubt that the automated growing system is better and more productive.

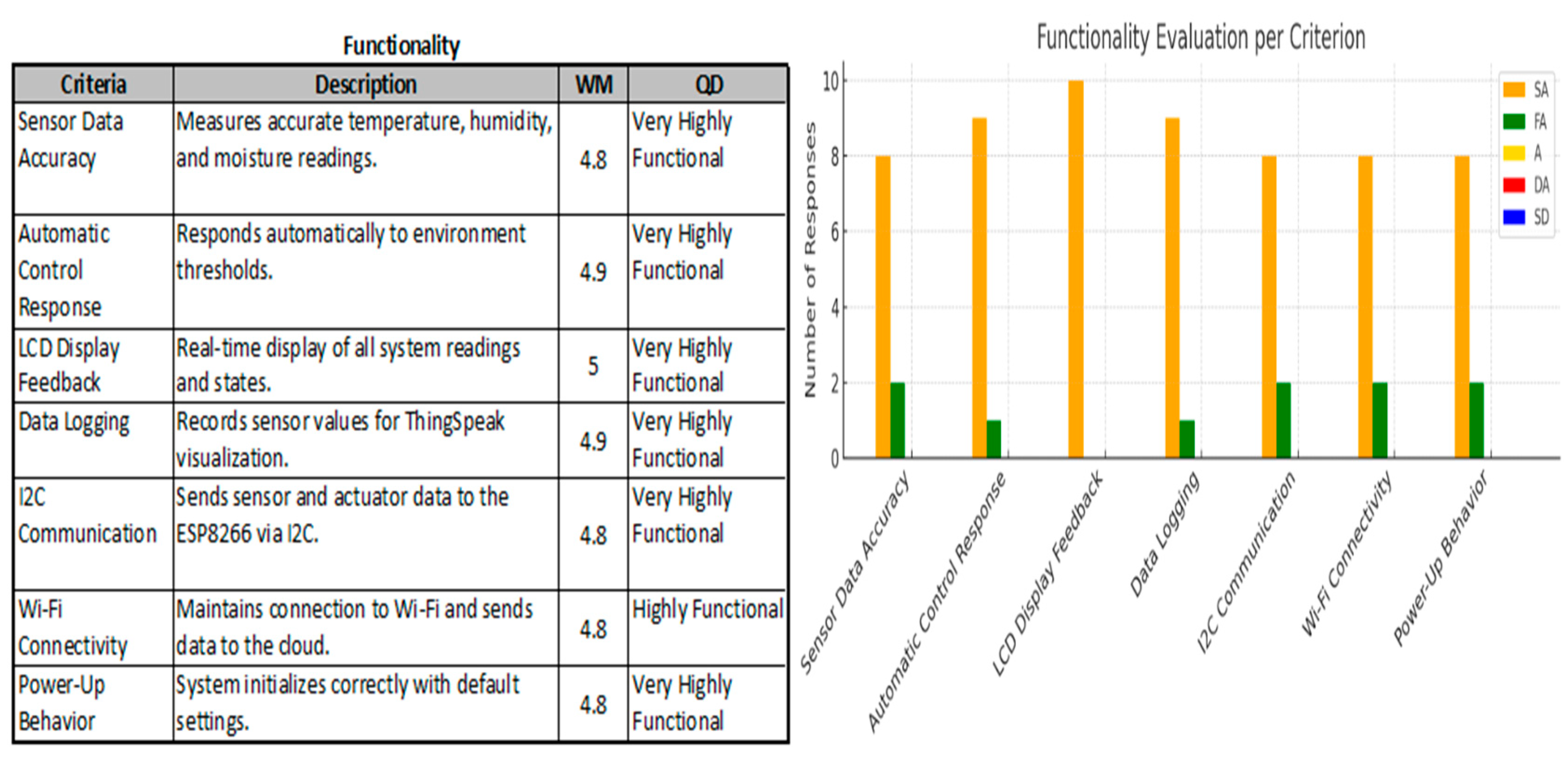

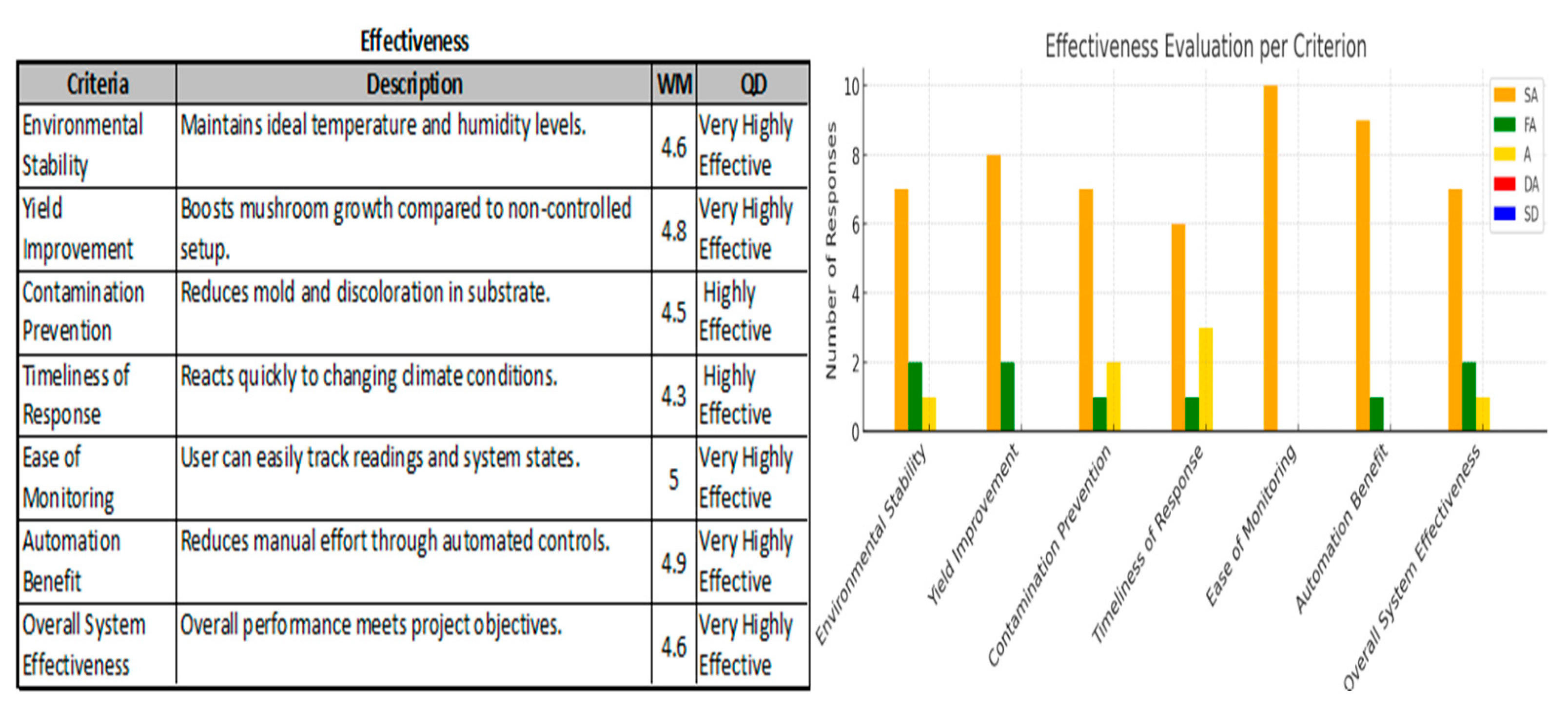

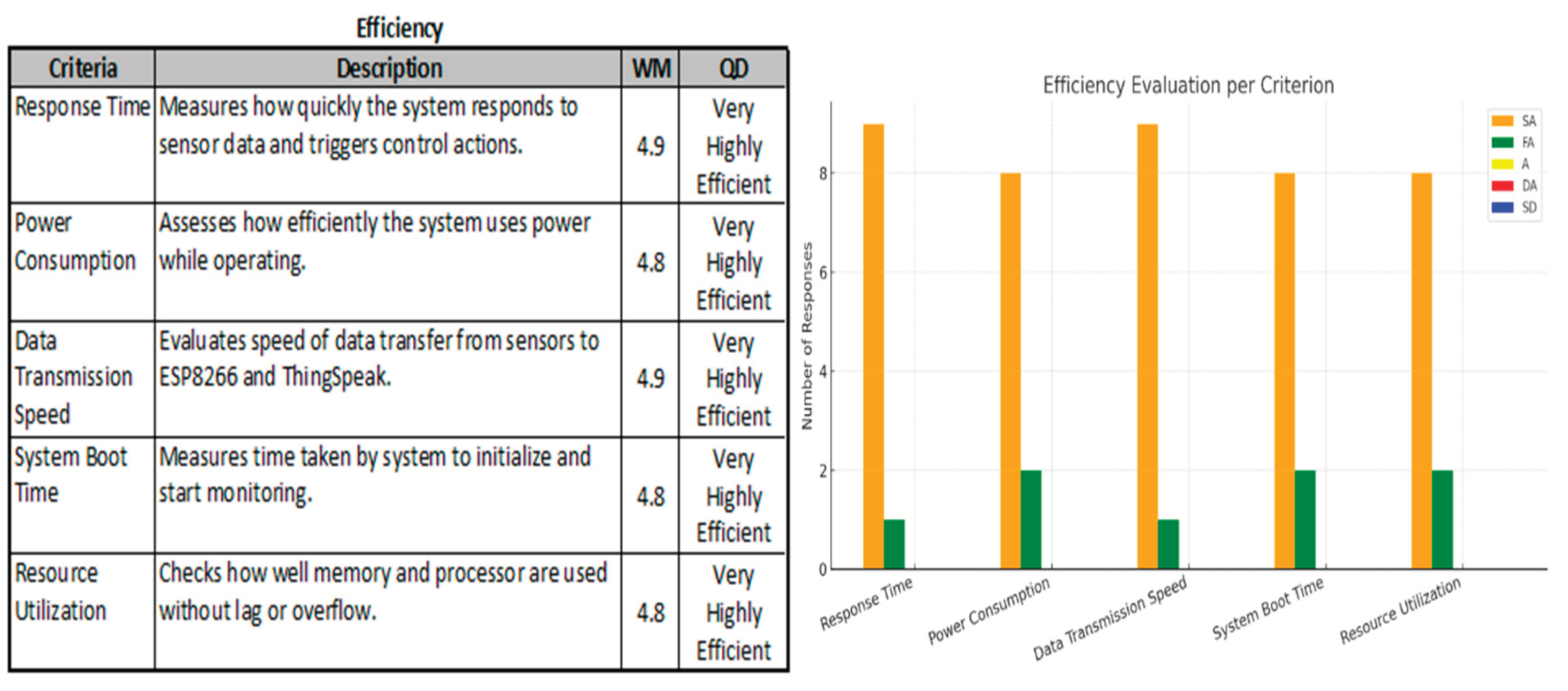

Prototype Evaluation

The conducted study, Precision Microclimate Control Using IoT for Enhanced Mushroom Production, monitors and automatically adjusts environmental parameters to maintain optimal conditions for mushroom cultivation. Ten respondents from Silang, Cavite, evaluated the system in terms of functionality, effectiveness, and efficiency.

Table 4.

Post-evaluation Survey in terms of Functionality.

Table 4.

Post-evaluation Survey in terms of Functionality.

Table 5.

Post-evaluation Survey in terms of Effectiveness.

Table 5.

Post-evaluation Survey in terms of Effectiveness.

Table 6.

Post-evaluation Survey in terms of Efficiency.

Table 6.

Post-evaluation Survey in terms of Efficiency.

The users rated the system highly, according to the evaluation results. Functionally, the following characteristics, including sensor precision, auto-controls, LCD feedback, data logging, and startup behavior, were rated "Very Highly Functional" with scores ranging from 4.8 to 5.0. Wi-Fi connectivity was rated "Highly Functional." In their effectiveness, dimensions such as stability within the environment, increased yields, monitoring capability, and the advantage of automation ranged from 4.3 to 5.0. They were generally very highly effective. Contamination prevention and response time were just slightly less, at "Highly Effective." To be efficient, critical factors such as response time, power consumption, data transmission rate, start time, and resource consumption were consistently scored as "Very Highly Efficient," with scores averaging 4.8 to 4.9. Overall, the results show that users are highly satisfied, indicating that the system is working well, effectively, and efficiently in growing mushrooms automatically.

4. Conclusions

In mushroom farming, the use of IoT technology has been found to improve productivity significantly. To address the issue of inconsistent environmental control, this study proposes a solar-powered, IoT-based system for automated mushroom farming. The system used a sensor-actuator setup that included a DHT22 sensor, a capacitive moisture sensor, and an ESP8266 to read data in real-time. The model was equipped with exhaust and ventilation fans, a water pump with overhead sprinklers, and an LCD to control optimal growing conditions. The system utilized solar energy supporting sustainable operation and greater efficiency compared to traditional methods, demonstrating superior performance in terms of average yield (352.5 g vs 136 g) and growth rate (harvest on 4th day vs 11th day). Stakeholder assessment showed that the system is far more efficient and effective, thus pointing to its great promise for sustainable and automated mushroom farming. Future development would focus on scaling it up, utilizing advanced data analytics, and applying the model in climate-sensitive agriculture, which would improve yields and sustainability further, and resilience in modern farming practices.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is extended to the College of Engineering of the Manuel S. Enverga University Foundation for the assistance and use of its facilities and resources.

References

- Jayaraman, S.; et al. Mushroom farming: A review Focusing on soil health, nutritional security, and environmental sustainability. Farming System 2024, 2, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, M.J.; et al. Mushrooms and Health Summit Proceedings. The Journal of Nutrition 2014, 144, 1128S–1136S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mina, J.C.; Campos, R.B., Jr.; Santiago, J.M.; Navarro, E.C.; Subia, G.S. Mushroom production as a source of livelihood for the depressed barangay in Nueva Ecija, Philippines: A strategic plan using TOWS matrix. International Journal of Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity 2020, 11, 3113–3121. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, A. Mushroom Production in Nueva Ecija: Promoting Entrepreneurship and Driving SDG Achievement for Sustainable Development. Journal of Lifestyle and SDGs Review 2025, 5, e04172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesia, M.J.C. Market assessment on white oyster mushrooms in Luzon, Philippines. Journal of Management Studies and Development 2025, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, H.T.; Wang, C.-L. The Effects of Temperature and Nutritional Conditions on Mycelium Growth of Two Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus cystidiosus). Mycobiology 2015, 43, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aditya, N.; Neeraj, N.; Jarial, R.S.; Jarial, K.; Bhatia, J.N. Comprehensive review on oyster mushroom species (Agaricomycetes): Morphology, nutrition, cultivation and future aspects. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, E.; It, U.F. Ultimate Guide to Mushroom Substrates. Urban Farm-It, May 01, 2025. https://urban-farm-it.com/blogs/mushroom-cultivation/guide-to-mushroom-substrates?srsltid=AfmBOopQV9Obf9qB_snZsQr24oD4Yxt8PIACn6ZRbMwVP1GrGD830QKG (accessed May 08, 2025).

- Muneeswaran, V.; Raghu, S.; Javed, S.; Yaswanth, V.; Priyanka, S.; Nagaraj, P. Instinctual Synced Ventilation for Mushroom Growing using IoT. 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS), Erode, India, 2023, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.D.; Patel, T.; Singh, H.J.; Singh, N.; Pal, A. Design and implementation of an IoT-based microclimate control system for oyster mushroom cultivation. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2024, 20, 1431–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Pedida, A.L. Integrating AI and IoT in Mushroom Growing Chamber. Jun. 25, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381665261_Integrating_AI_and_IoT_in_Mushroom_Growing_Chamber.

- Tiwari, S.; Sharma, N. Real-time monitoring of smart greenhouse environment using IoT for sustainable agriculture," Paripex – Indian Journal of Research 2020, 9, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Setiawati, D.A.; Utomo, S.G.; Murad, N.; Putra, G.M.D. Design of temperature and humidity control system on oyster mushroom plant house based on Internet of Things (IoT). IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 712, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghirang, M.S.; Maaño, R.; Santonil, H.S.; Canela, D.N.; De la Roca, M.J.; Buban, D.J.; Maaño, R.A. IoT-Enabled Soil Moisture Management for Precision Plant Sprinkler System for Organic Farming, Manuel S. Enverga University Foundation, Lucena City, Philippines.

- Maaño, R.C.; Maaño, R.A.; De Castro, P.J.; Chavez, E.P.; De Castro, S.C.; Maligalig, C.D. SmartHatch: An Internet of Things–Based Temperature and Humidity Monitoring System for Poultry Egg Incubation and Hatchability, Manuel S. Enverga University Foundation and Technological Institute of the Philippines, Lucena City and Manila, Philippines.

- Ncr.Dost.Gov.Ph and Ncr.Dost.Gov.Ph, “New technology to level up mushroom farming in Pasig City - DOST-NCR. DOST-NCR - Spearheading Innovations, Mar. 26, 2025. https://ncr.dost.gov.ph/new-technology-to-level-up-mushroom-farming-in-pasig-city/.

- Perlite, S.; Perlite, S. Unlocking the secrets of mushroom fruiting chambers: The Perlite Advantage - Supreme Perlite Company. Supreme Perlite Company - The Pacific Northwest’s Leading Manufacturer of Perlite Products Since 2024, 1954. https://www.supremeperlite.com/mushroom-fruiting-chambers-perlite-advantage/.

- Khaing, K.K.; Raju, K.S.; Sinha, G.R.; Swe, W.Y. Automatic temperature control system using Arduino. in Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 2020, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Liang, Q.; Li, H.; Pang, Y. Application of Internet-of-Things Wireless Communication Technology in Agricultural Irrigation Management: A review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.R.S. A Review Paper on Electricity Generation from Solar Energy. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2017, V, 1884–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, A.S.; Afianti, H.; Watiasih, R. Comparative analysis of solar charge controller performance between MPPT and PWM on solar panels. JEECS (Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences) 2023, 7, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).