3. Analysis of the Formation of Stars and Their Equilibrium/Stability in the Early Universe According to the New Cosmological Model

According the new suggested Cosmological Model, the gravity of the Hydrogen had been shaped till approx. 20% of the current estimated value as result of the interaction with the primitive electromagnetic radiation prior to the formation of the first stars in the early Universe. [

1]

Therefore, in order to do our analysis based on this gravity degree, we’ll assume that the gravitational constant G’ = 20% G.

Star Size=1 x Sun’s mass (M⊙)

We’ll begin with a star equivalent to the Sun. Let’s analyze the conditions for hydrostatic equilibrium in the core of a star with 1x the Sun’s mass (

M=

M⊙), composed entirely of hydrogen, with a gravitational constant

G′ = 0.2×

G, where G =6.67430×10

−11m

3kg

−1s

−2. We’ll determine the core conditions using hydrostatic equilibrium [

2] and the equation of state [

3], check if the core reaches the hydrogen fusion temperature (~10

7 K), and assess long term stability.

Stellar Parameters

Mass: M = M⊙ =1.989×1030kg.

Composition: Pure hydrogen (X = 1, Y = Z = 0, that is, mainly composed of hydrogen atoms (X), with negligible amounts of helium (Y) and heavier elements (Z)).

Gravitational constant: G′ = 0.2×G = 1.33486×10−11m3kg−1s−2.

Equations: Hydrostatic equilibrium and ideal gas equation of state (since a solar-mass star’s core is non-degenerate). We’ll verify if fusion occurs and assess stability.

Hydrostatic Equilibrium and Equation of State

Hydrostatic equilibrium is [

2]:

For the core, we estimate central pressure as:

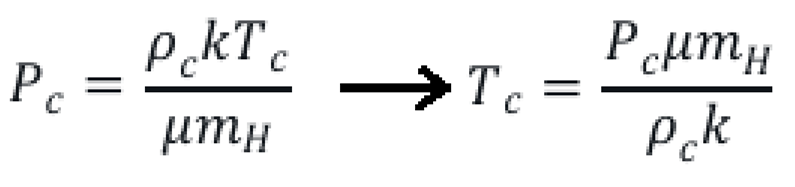

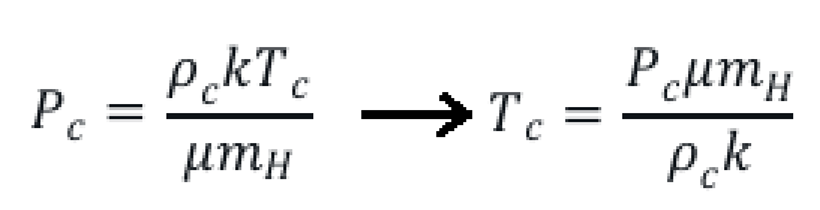

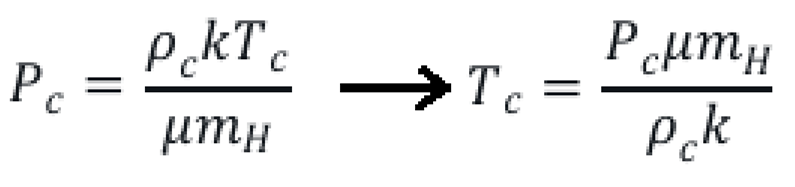

The equation of state for a fully ionized hydrogen core is [

3]:

where

k = 1.380649×10−

23J K

−1,

mH = 1.6726×10

−27kg, and for pure hydrogen (

X = 1), the mean

molecular weight

μ for fully ionized hydrogen is:

since each hydrogen atom provides one proton and one electron.

Therefore μ = 0.5.

Estimating Radius

For a solar-mass star with standard G,

R ≈

R⊙ = 6.96×10

8m. The lower G’ reduces gravitational compression, potentially increasing the radius. Using the polytropic relation (

P = Kρ(1+1/n) with

ρ=density and k=constant) for main-sequence stars (

n ≈3) and scaling [

4]:

R ∝ (

G′

M)

−1/2 (via virial theorem [

5] and luminosity scaling).

So, R ≈ 2.236R⊙ ≈ 1.557×109m. This is a rough estimate; main-sequence stars with lower G are less compact.

Core Conditions

Substituying values:

M=1.989×1030kg, R =1.557×109m, G′ = 1.33486×10−11m3kg−1s−2

M2 =(1.989×1030)2 ≈ 3.956×1060 kg2

R4 = (1.557×109)4 ≈ 5.868×1036m4

G′ M2 ≈ 1.33486×10−11×3.956×1060 ≈ 5.279×1049 N m2

Pc ≈ 9.00× 1012 Pa

Core density and temperature

Assume density

ρc ≈ 1.5×10

5kg/m

3 (similar to the Sun’s core)

This is below the fusion threshold. Let’s try to refine using a polytropic scaling for temperature [

4]:

Using solar values (

Tc,

⊙ ≈ 1.57×10

7K) as reference:

Fusion Temperature

Hydrogen fusion requires Tc ≳ 107K. Both estimates (3.63×106K and 1.40×106K) are below this threshold, suggesting that fusion may not occur. The reduced G’ significantly lowers core compression, resulting in a larger, less dense star with a cooler core.

Stability

Without sustained fusion, the star cannot maintain thermal equilibrium as a main-sequence star. It would resemble a protostar or pre-main-sequence object, contracting slowly. Long-term stability requires fusion, which seems unlikely here. The star may:

- -

Contract further to increase Tc, but the low G’ limits compression.

- -

Remain a “failed star” or proto-star-like object, cooling over time.

Summary

Core conditions (Temperature, density, pressure): Tc ≈ 1.4–3.6×106K, ρc ≈ 1.5×105kg/m3, Pc ≈ 9.00×1012Pa.

Fusion: The core temperature is below the ~107 K needed for hydrogen fusion, so fusion is unlikely (only in a very small rate).

Stability: Without fusion, the star cannot sustain a stable main-sequence phase and will likely contract and cool over time, behaving like a massive proto-star or brown dwarf.

Star Size=0.5 x Sun’s mass (M⊙)

Stellar Parameters and Assumptions

Mass: M = 0.5M⊙, where M⊙ = 1.989×1030kg, so M = 9.945×1029kg.

Composition: Pure hydrogen (X = 1, Y = Z = 0).

Gravitational constant: G′ = 0.2×G = 0.2×6.67430×10−11 = 1.33486×10−11m3kg−1s−2

Equations: We’ll use the hydrostatic equilibrium equation [

2] and the ideal gas equation of state [

3], considering possible degeneracy effects in this case since the star is low-mass. We’ll check if the core reaches the temperature for hydrogen fusion (~10

7 K) and assess stability.

Hydrostatic Equilibrium and Equation of State

The condition for hydrostatic equilibrium in a star is given by:

For the core, we estimate central pressure as:

where R is the stellar radius. However, we need the core density and temperature, so we’ll use the equation of state. For a pure hydrogen core, we consider two possibilities:

Ideal gas: where k = 1.380649×10−23J K−1, mH = 1.6726× 10−27kg, and μ is the mean molecular weight.

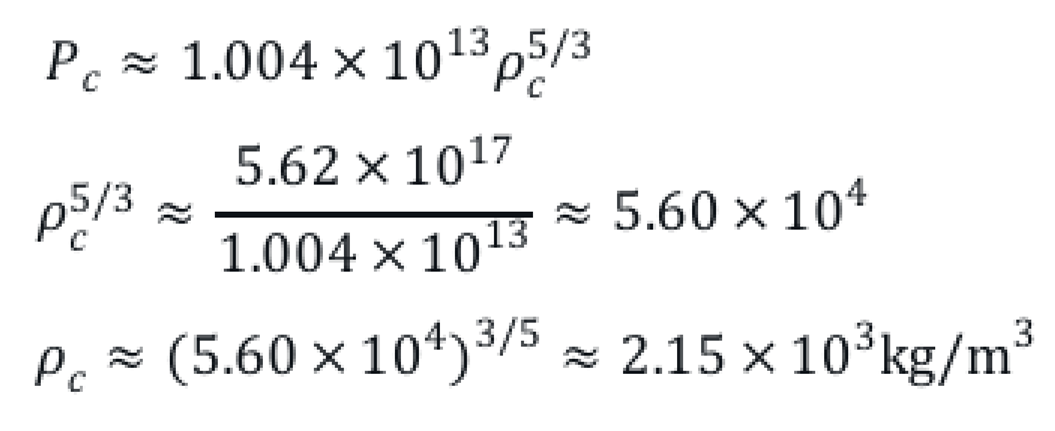

Degenerate gas: For low-mass stars, electron degeneracy pressure may dominate, given by:

Pe ≈

Kρ5/3 , for non-relativistic degeneracy, where

K ≈ 1.004×10

13(Pa⋅(kg/m

3)

−5/3) for fully ionized hydrogen. For pure hydrogen (

X = 1), the mean molecular weight

μ for fully ionized hydrogen is:

since each hydrogen atom provides one proton and one electron.

Estimating Core Conditions

To estimate core conditions, we need to know the stellar radius R. For a star with M = 0.5M⊙, we can approximate the radius using scaling relations for main-sequence stars or brown dwarfs, adjusted for the modified G. For main-sequence stars, the mass-radius relation is roughly R ∝ M0.8, but for low-mass stars or brown dwarfs, the radius is less sensitive to mass due to degeneracy, often R ≈ 0.1R⊙. Let’s assume R ≈ 0.1R⊙ = 6.96×107m, typical for a 0.5 M⊙ star or high-mass brown dwarf, and adjust later if needed.

Central pressure estimation:

Substitute: G′ = 1.33486×10−11m3kg−1s−2, M=9.945×1029kg,

R =6.96×107m. → Pc ≈ 5.62× 1017 Pa.

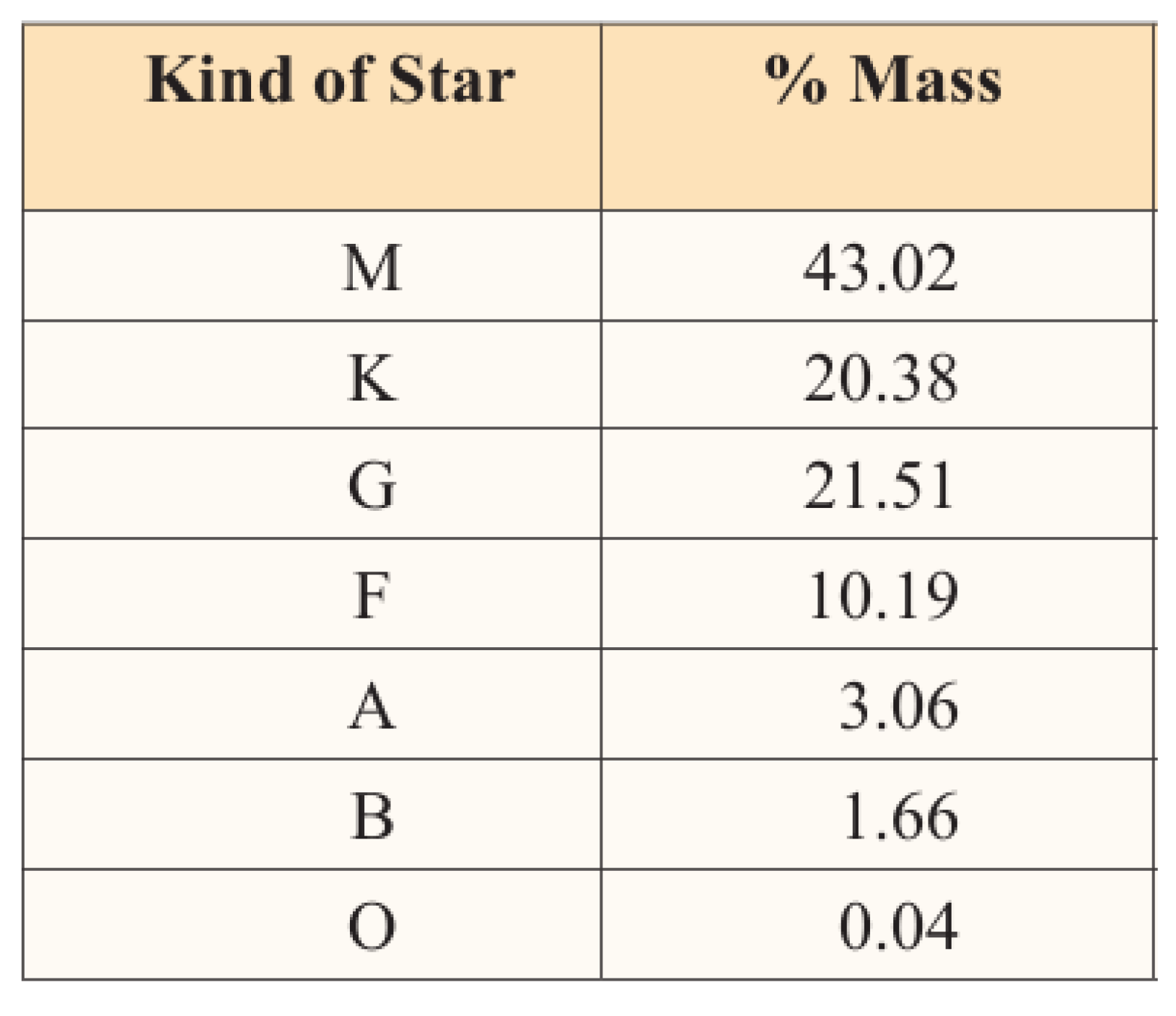

Core density:

Assume a polytropic model (

P ∝

ρ1+1/n,

n ≈ 1.5 for degenerate cores). For non-relativistic degeneracy [

4]:

This density is l

ow compared to

typical degenerate cores (~10

6–10

8 kg/m

3), suggesting degeneracy may not dominate. Let’s try the other way, that is, ideal gas law:

Assuming density ρc ≈ 105kg/m3 (typical for low-mass stellar cores): Tc = 3.40 x 108 K

This temperature is well above the hydrogen fusion threshold (~107 K), but let’s refine using a polytropic model.

Polytropic Model and Scaling

For a polytrope with

n = 1.5, the central density and temperature scale as [

4]:

Using solar values (

M⊙,

R⊙,

Tc,

⊙ ≈ 1.57×10

7K) and scaling:

Assume R ≈ 0.1 R⊙: Tc ≈ 1.57×107×0.5×10×0.2 = 1.57×107K

This is on the order of the fusion temperature, but we need to account for the lower G. The reduced gravitational constant decreases the core compression, so let’s compute the radius more accurately. For degenerate stars, radius scales as:

Using a reference (e.g., brown dwarf,

Mref = 0.5

M⊙,

Rref ≈ 0.1

R⊙):

Then, recalculating pressure and temperature with R ≈ 0.215R⊙ = 1.49×108m

R4 = (1.49×108)4 ≈ 4.93×1033m4, ρc ≈ 1.320×1049 / (4.93×1033) ≈ 2.68× 1015Pa.

That is, using ideal gas:

Fusion Temperature

Hydrogen fusion (proton-proton chain) requires Tc ≳ 107K. The calculated Tc ≈ 1.62×107K exceeds this, suggesting fusion is possible. However, the lower G’ reduces core compression, making fusion less efficient. The fusion rate scales as ϵ ∝ ρTν, where ρ=density, T=Temperature and ν ≈ 4–6 for the p-p chain. The lower density and slightly lower temperature (compared to a 0.5 M⊙ star with standard G) imply a reduced fusion rate.

Stability

For long-term stability, the star must maintain hydrostatic and thermal equilibrium. With fusion active, the star can sustain itself on the main sequence, balancing energy generation with losses. However:

Low fusion rate: The reduced G’ lowers core density and temperature, reducing the fusion rate, potentially making the star a marginal main-sequence star or a “hot brown dwarf.”

Degeneracy: If the core becomes partially degenerate, fusion may be unstable or insufficient, leading to a brown dwarf-like object that cools over time.

Timescale: For a 0.5 M⊙ star with standard G, the main-sequence lifetime is ~50 billion years. With lower G’, the luminosity L ∝ M3(G′)4/R is reduced, extending the lifetime, but if fusion is marginal, the star may not sustain a stable main sequence. In any case, as the star begins the fusion, other processes that we’ll analyze forward take place increasing the fusion rate (2).

Summary

Core conditions: Tc ≈ 1.62×107K, ρc ≈ 105kg/m3, Pc ≈ 2.68×1015Pa.

Fusion: The core temperature reaches the threshold for hydrogen fusion, but the lower G’ reduces initially the fusion rate.

Stability: The star may sustain fusion briefly, resembling a low-mass main-sequence star, but partial degeneracy and low fusion efficiency suggest it could behave like a brown dwarf, cooling over time rather than remaining stable for billions of years, although the relevance of (2) should not be dismissed. We would be looking at a star whose first millions of years would determine its stability over time.

Star Size=3 x Sun’s mass (M⊙)

Stellar Parameters

Mass: M = 3M⊙ =3×1.989×1030 = 5.967×1030kg.

Composition: Pure hydrogen (X = 1, Y = Z = 0).

Gravitational constant: G′ = 0.2×G = 0.2×6.67430×10−11 = 1.33486×10−11m3kg−1 s−2

Equations: Hydrostatic equilibrium and ideal gas equation of state (since a 3

M⊙ star’s core is non degenerate).[

2,

3]

Hydrostatic Equilibrium and Equation of State

Central pressure estimate for the core:

Equation of state for fully ionized hydrogen (

μ = 0.5):

where

k = 1.380649×10

−23J K

−1,

mH = 1.6726×10

−27kg.

Estimating Radius

For a 3

M⊙ star with standard G, the radius is approximately

R ≈ 1.7

R⊙ (based on main-sequence scaling,

R ∝

M0.7). With lower G’, the star is less compressed, so we scale the radius:

So R ≈ 3.873R⊙ ≈ 2.696×109m.

Core Conditions

Substitute: M=5.967×1030kg, R =2.696×109m,

G ′ = 1.33486×10−11m3kg−1s−2

Then Pc ≈ 4.752×1050 / 5.279×1037 ≈ 9.00× 1012Pa.

Core density and temperature:

Assume

ρc ≈ 5×10

4kg/m

3 (1/3 lower than the Sun’s core due to 3xlarger radius):

So Tc=1.09×107K

The ideal gas estimate (1.09×107K) is more consistent with fusion conditions, so we adopt it.

Fusion Temperature

Hydrogen fusion requires Tc ≳ 107K. The core temperature (1.09×107K) is just above this threshold, suggesting fusion is possible, though less efficient due to lower G’. The fusion rate (ϵ ∝ ρTν, ν ≈ 4–6) is reduced compared to a standard 3 M⊙ star, but the (2) factor must be also considerated as we’ll analyze forward.

Stability

With fusion occurring, the star can achieve hydrostatic and thermal equilibrium, behaving as a main sequence star. However:

Reduced fusion rate: Lower G’ decreases core density and temperature, reducing luminosity and extending main-sequence lifetime compared to a standard 3 M⊙ star (~400 Myr).

Stability: The star is stable as long as fusion sustains energy output. The larger radius and lower core density suggest a lower luminosity, potentially resembling a less massive main-sequence star.

Summary:

Core conditions: Tc ≈ 1.09×107K, ρc ≈ 5×104kg/m3, Pc ≈ 9.00×1012Pa.

Fusion: The core temperature marginally exceeds the fusion threshold, so hydrogen fusion occurs, but initially at a slightly reduced rate.

Stability: The star can maintain main-sequence stability, but its lower fusion efficiency and larger radius suggest a longer lifetime than a standard 3 M⊙ star.

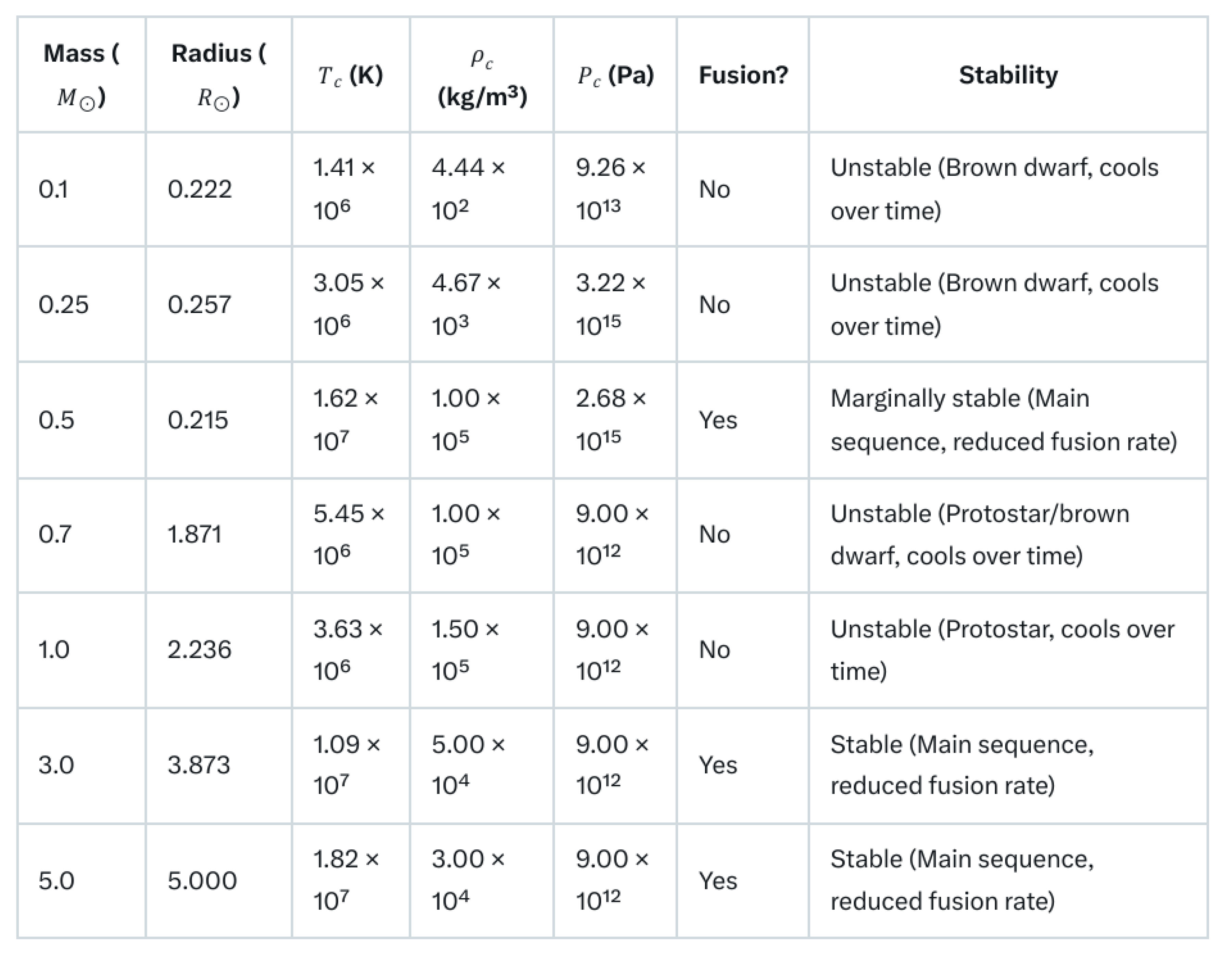

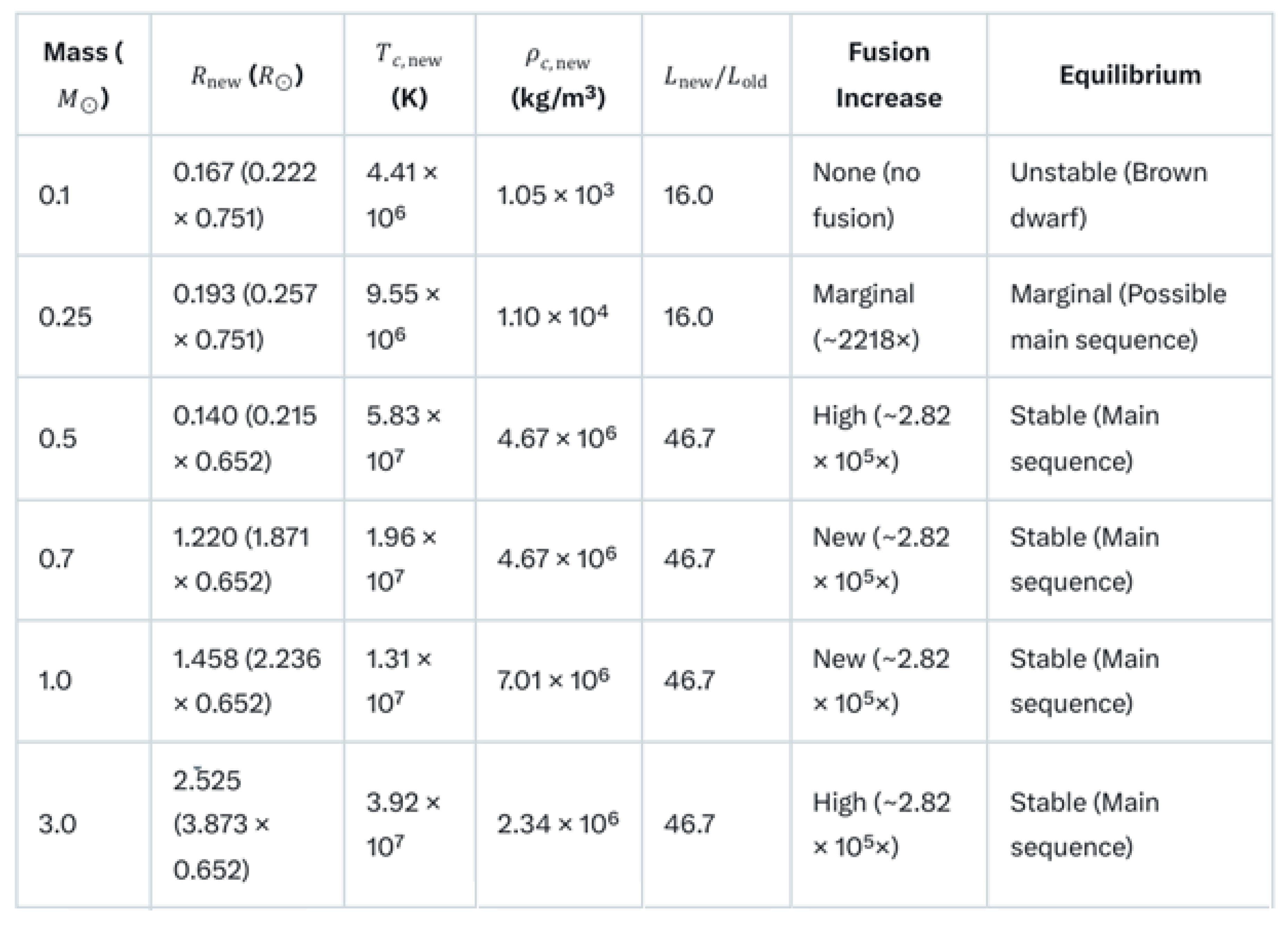

Other Star Sizes

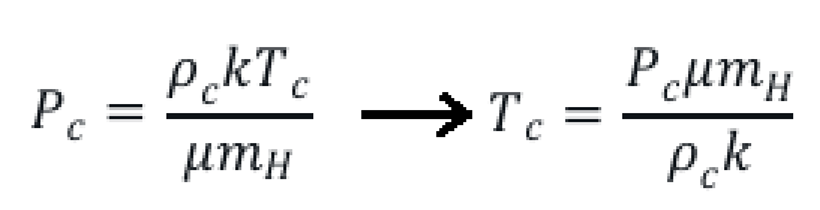

We can extend the calculation with the same basis to every kind of star, with different sizes.

Summary Table

The following summary shows the more relevant parameters and conclusions:

Some relevant conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

Small (in mass) stars with a mass M < 0.5 Sun’s mass (M⊙) are almost impossible to evolve, given their low temperature. Their fusion rate is excessively low so they fail.

- (2)

Stars with a mass M around 0.5 M⊙ can be stable if they’re able to increase slightly their fusion rate supported by (2).

- (3)

It’s very unlikely that Stars with a mass M such that 0.7 M⊙ < M < 2 M⊙ reach stability, because their fusion rate is low.

- (4)

Most of Stars with a mass M > 2 M⊙ should be able to reach stability, even more if they’re able to increase very slightly their fusion rate thanks to (2).

Therefore we can observe that many stars can’t reach an adequate fusion rate that guarantees their stability. As consequence, the rate of stars that were not able to evolve should be quite superior to the stars that really did it. Although it’s pretty difficult to infere such rate, we’ll do an estimation based on current stars distribution by size later.

What is clear is the most common stable stars in the early Universe would be those with more of 2x Sun’s mass. This is consistent with latest JWST detections, including “surprisingly” high levels of metalicity in some early galaxies.

4. Relevance of Induced Gravity on the Rate of Stellar’s Fusion Processes

According to previous works, the interaction among electromagnetic radiation and matter produced mainly by photoelectric effect/kinetic energy, creates an emergent time and an associated induced gravity.[

1,

6]

We’ll take the Sun as reference.

The value of such induced gravity increases from the outer layer to the inner layer of the radiative zone. It’s estimated around 35% for the outer layer, 60% for the middle layer and 100% for the inner layer. [

6]

The estimated kinetic energy density Ke is different for every layer (increasing from outer to inner), but we’ll do a conservative simplification of Ke=106 J/m3 like support by doing the following basic calculations:

We’ll calculate at first how much time needs the Sun for producing a Ke kinetic energy density through all the radiative layer assuming a hypothetical (although unreal) scenario where there’s not opacity at all:

Radiative Layer Volume: The Sun’s radiative zone extends from about 0.25 to 0.7 solar radii (R☉ = 6.96 × 10⁸ m). The volume of a spherical shell is approximated as V = (4/3)π [(0.7R☉)³ - (0.25R☉)³].

Inner radius = 0.25 × 6.96 × 10⁸ m = 1.74 × 10⁸ m

Outer radius = 0.7 × 6.96 × 10⁸ m = 4.872 × 10⁸ m

Volume = (4/3)π [(4.872 × 10⁸)³ - (1.74 × 10⁸)³] ≈ (4/3)π [1.156 × 10²⁷ - 5.266 × 10²⁵] ≈ 1.14 × 10²⁷ m³

Total Energy: The total kinetic energy equivalent to this energy density is E = energy density × volume= 106 J/m³ × 1.14 × 10²⁷ m³ ≈ 1.21 × 10²⁹ J.

Sun’s Energy Output: The Sun’s total luminosity (power output) is approximately P=3.846 × 10²⁶ W which is the rate of electromagnetic radiation energy emitted. This energy originates from nuclear fusion in the core, some of which is converted into kinetic energy in the radiative zone via photon interactions. The percentage (average) of such kinetic energy coming from photoelectric effect could be estimated in 0.01% (conservative value). [

1]

Therefore the time required to produce this energy is given by t = E / P.

So the time needed for getting energy enough for creating the induced gravity is not relevant in cosmological time. But there’s another param that determines the time really needed. We’re talking about the time needed for radiation (and therefore kinetic energy) for reaching to any point of the radiative layer due to the high opacity. This time can be calculated in different ways. It can be estimated among 170.000 years-1 million of years. We’re going to take the more conservative value as usual:

1 million of years. [

1]

Therefore there will be an induced gravity over the Hydrogen in the radiative zone which will increase the total gravity and as consequence it also will increase the fusion rate.

Our first step will be calculate the new gravity.

Assumptions and Approach

-

Stellar Structure.

- -

Low-mass stars (0.1, 0.25 M⊙) are fully convective, lacking a radiative zone, so the varying G may not apply directly, but we’ll assume the radiative zone exists for consistency across all masses. In any case, with so low fusion rate, induced gravity not apply in these cases.

- -

Higher-mass stars (0.5–5 M⊙) have a radiative zone. We divide it into three layers (outer, middle, inner) with equal mass fractions for simplicity.

- -

The core (where fusion occurs) retains G′ = 0.2×G . This is a conservative value again. Why conservative?... Because although it’s supposed that Hydrogen is fully ionized in the core (so the emergent time and its associated induced gravity would not apply), a percentage of the Hydrogen belonging to the inner layer of the radiative zone closer to the core is expected to become part of the core through the time.

-

Luminosity.

Luminosity (L) depends on mass, radius, and

gravitational constant. We use scaling relations adjusted for the effective G

in the radiative zone.

-

Fusion Rate.

Fusion

rate depends on core temperature and density. Changes in G in the radiative

zone affect the star’s structure, indirectly influencing core conditions.

-

Equilibrium.

We

assess hydrostatic and thermal equilibrium over 1 million years (although it

can vary slightly depending of the size of the star), considering whether

fusion can sustain the star against gravitational changes.

-

Methodology.

We’ll

use:

- -

The previous core conditions (Tc, ρc, Pc) as a baseline.

- -

Adjust radius and luminosity using an effective Geff for the radiative zone.

- -

Estimate fusion rate changes via core conditions.

- -

Evaluate equilibrium based on fusion and structural stability.

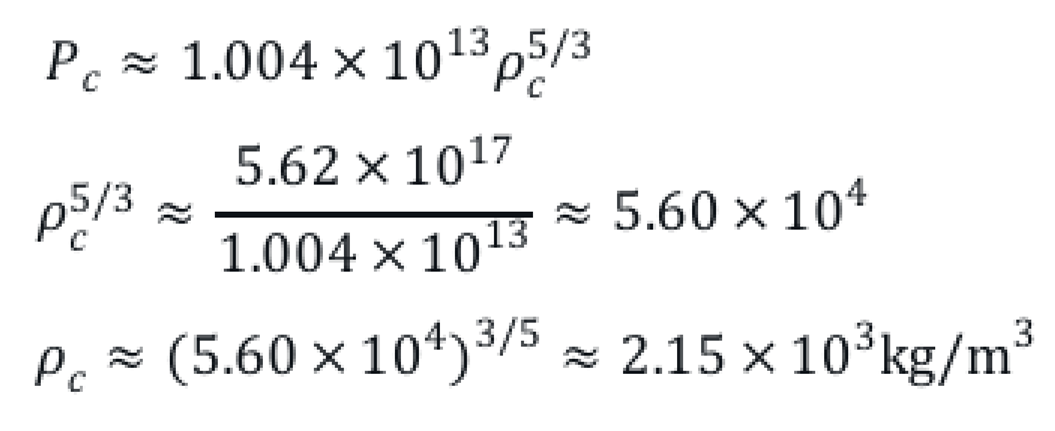

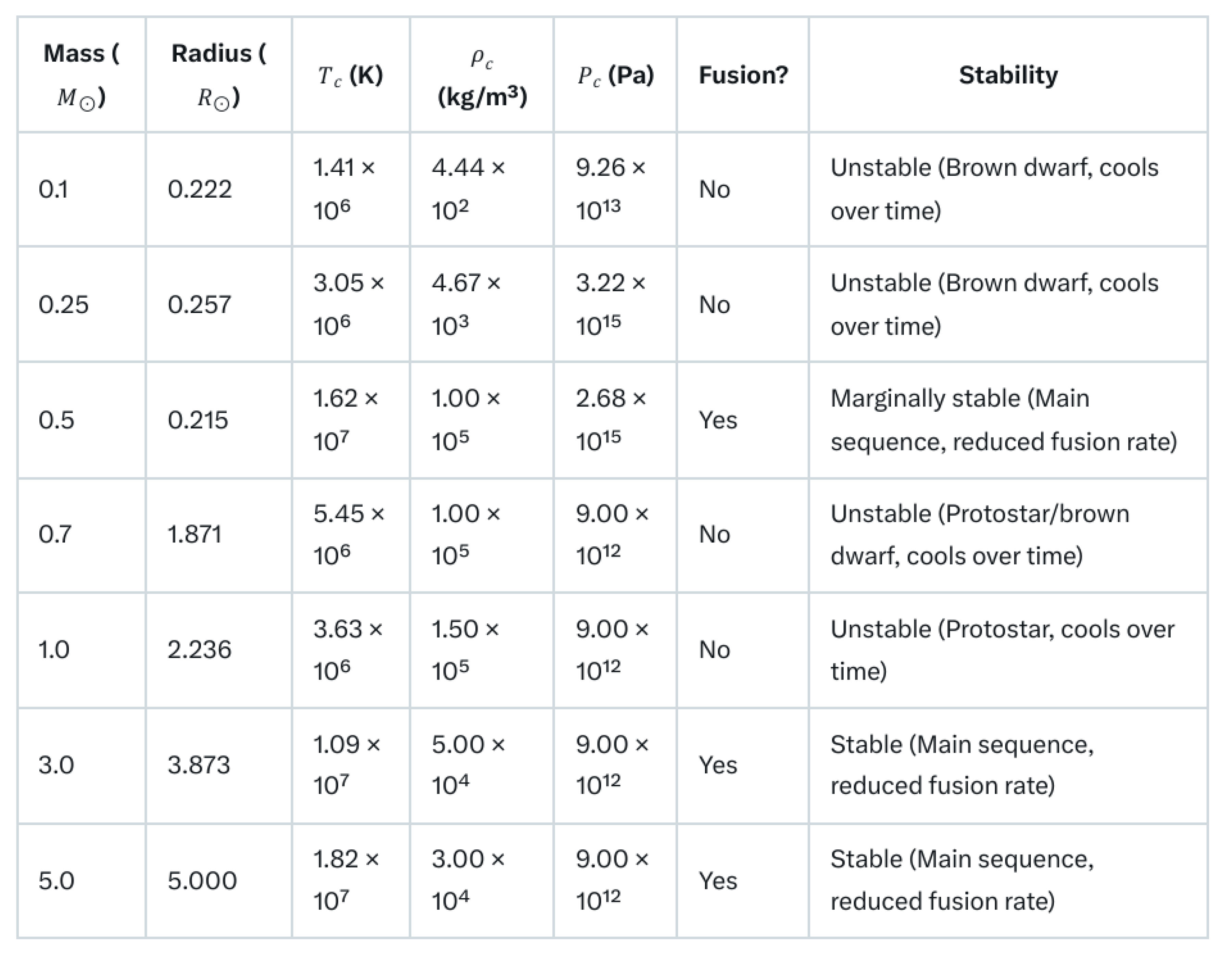

Effective Gravitational Constant

The radiative zone spans a significant portion of the star’s mass and radius in stars with

M ≥ 0.5

M⊙. For simplicity, assume the radiative zone contains ~60% of the star’s mass, split equally across the three layers (20% each). The effective gravitational constant for the radiative zone is approximated as a mass weighted average:

For the entire star, we approximate an overall effective G:

Core (~10% mass, for low-mass stars more):

G′ = 0.2

G. It’s supposed that 100% of Hydrogen is ionized by thermalization due to the high temperature, so the kinetic cloud due to photoelectric effect does not apply here and as consequence induced gravity neither.[

6]

Convective zones (variable, ~30% for higher masses): G′ = 0.2G. It doesn’t change because kinetic energy by photoelectric effect does not apply in this zone.

Radiative zone (~60%): Geff = 0.65G as calculated before.

Assuming mass fractions of 10% core, 30% convective, 60% radiative:

Gstar ≈ 0.1×0.2G + 0.3×0.2G + 0.6×0.65G = 0.02G+0.06G+0.39G = 0.47G = 3.1369×10−11m3kg−1s−2.

This Gstar is higher than the previous G′ = 0.2G, increasing gravitational compression.

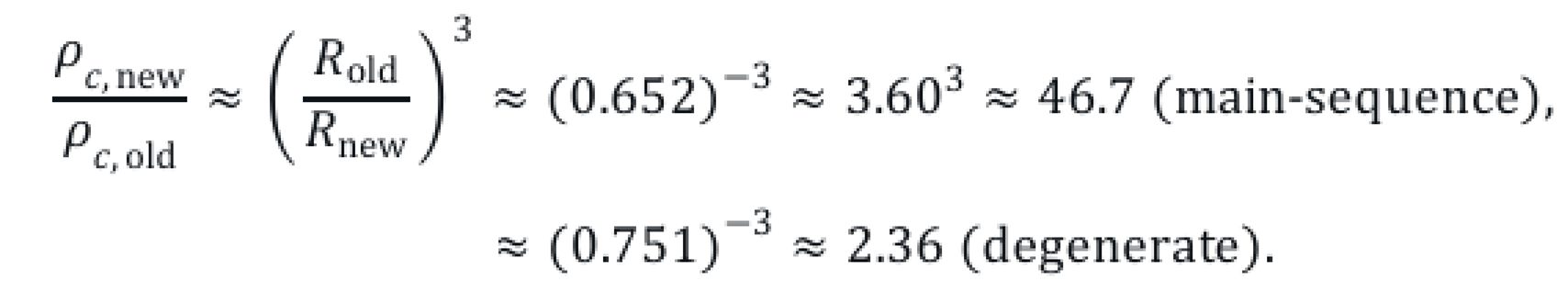

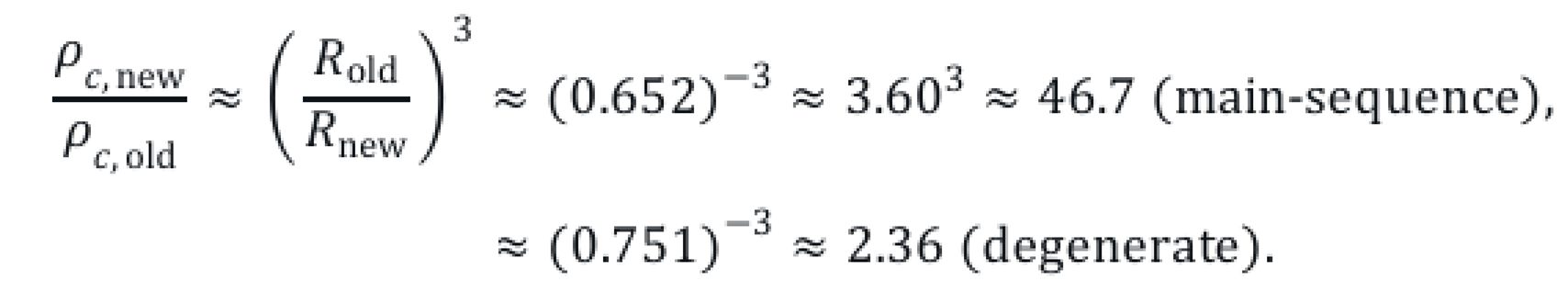

Radius Adjustment

The stellar radius scales as

R ∝ (

GM)−1/2 for main-sequence stars (virial theorem). [

5] Compared to the previous case (

G′ = 0.2

G):

For low-mass stars (0.1–0.5

M⊙), where degeneracy dominates,

R ∝ (

GM)

−1/3:

Luminosity Changes

Luminosity scales as

L ∝

M3(

G)

4/

R for main-sequence stars. The new luminosity relative to the previous case (with

G′=0.2

G):

For low-mass stars (degenerate), luminosity is less sensitive to G, but we approximate using a polytropic model [

4]:

Core Conditions and Fusion Rate

The increased

Gstar=0.47

G compresses the star, reducing radius and increasing core density and temperature. Using the scaling for core temperature:

Core density scales as

ρc ∝

M/

R3:

Fusion rate (

ϵ ∝

ρTν,

ν ≈ 4–6 for p-p chain):

For main-sequence stars (

ν = 5):

For low-mass stars (

ν = 6, assuming marginal fusion):