Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

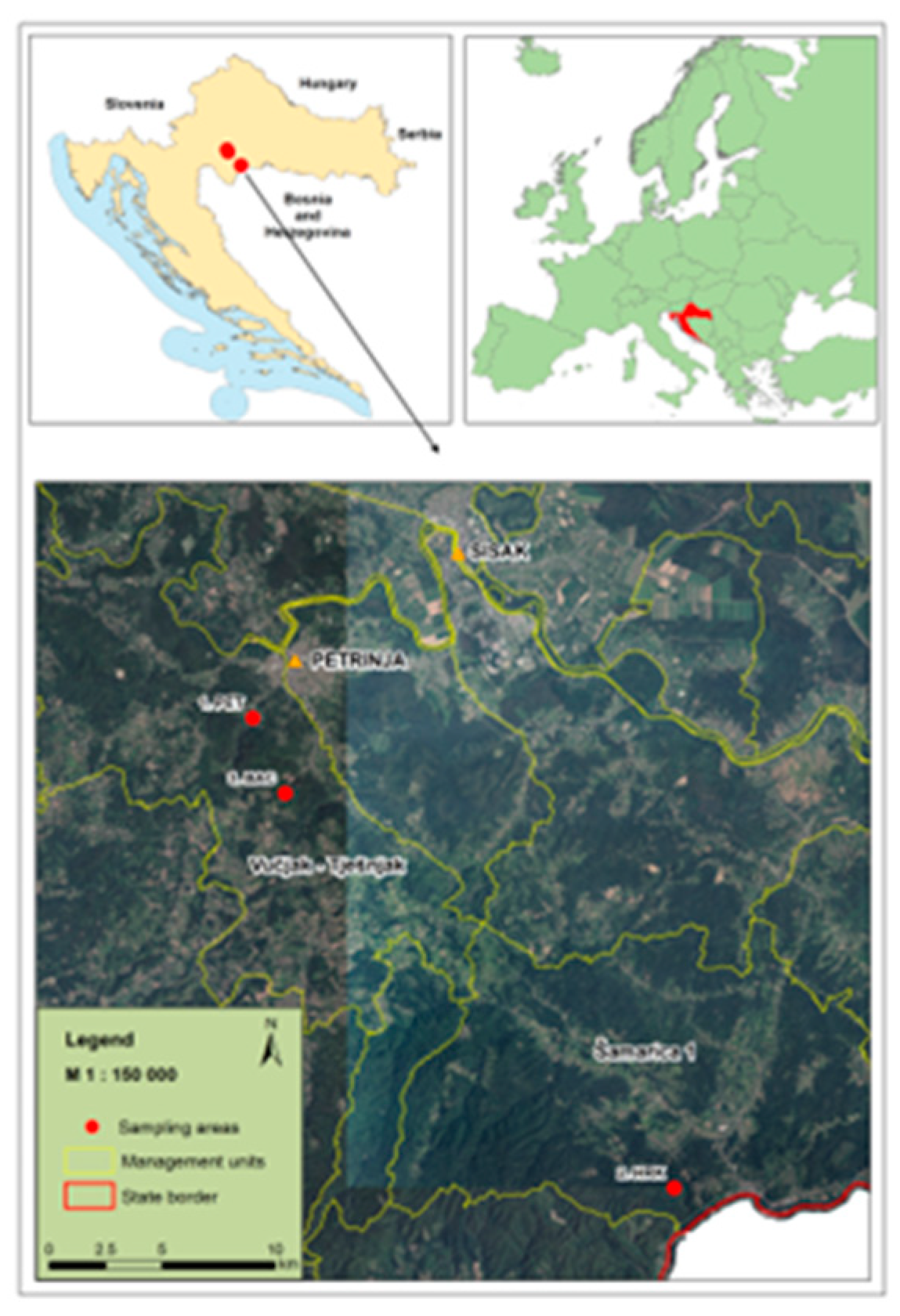

2.1. Study Area and Plant Material Collection

2.2. DNA Isolation, SSR Amplification, and Analysis

2.3. Genetic Analyses

3. Results

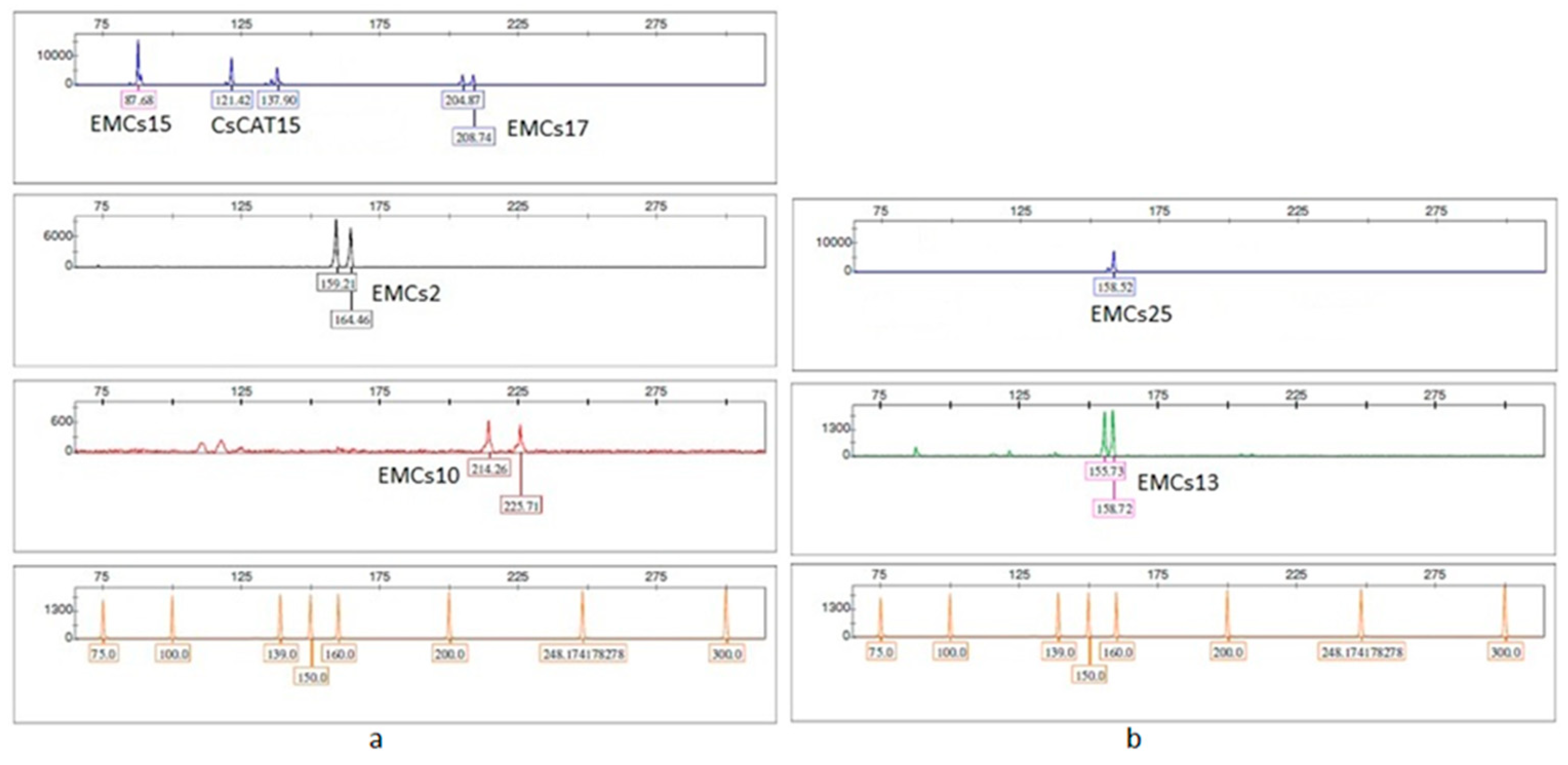

3.1. SSR Primer Screening and PCR Amplification

3.2. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Loci and Populations

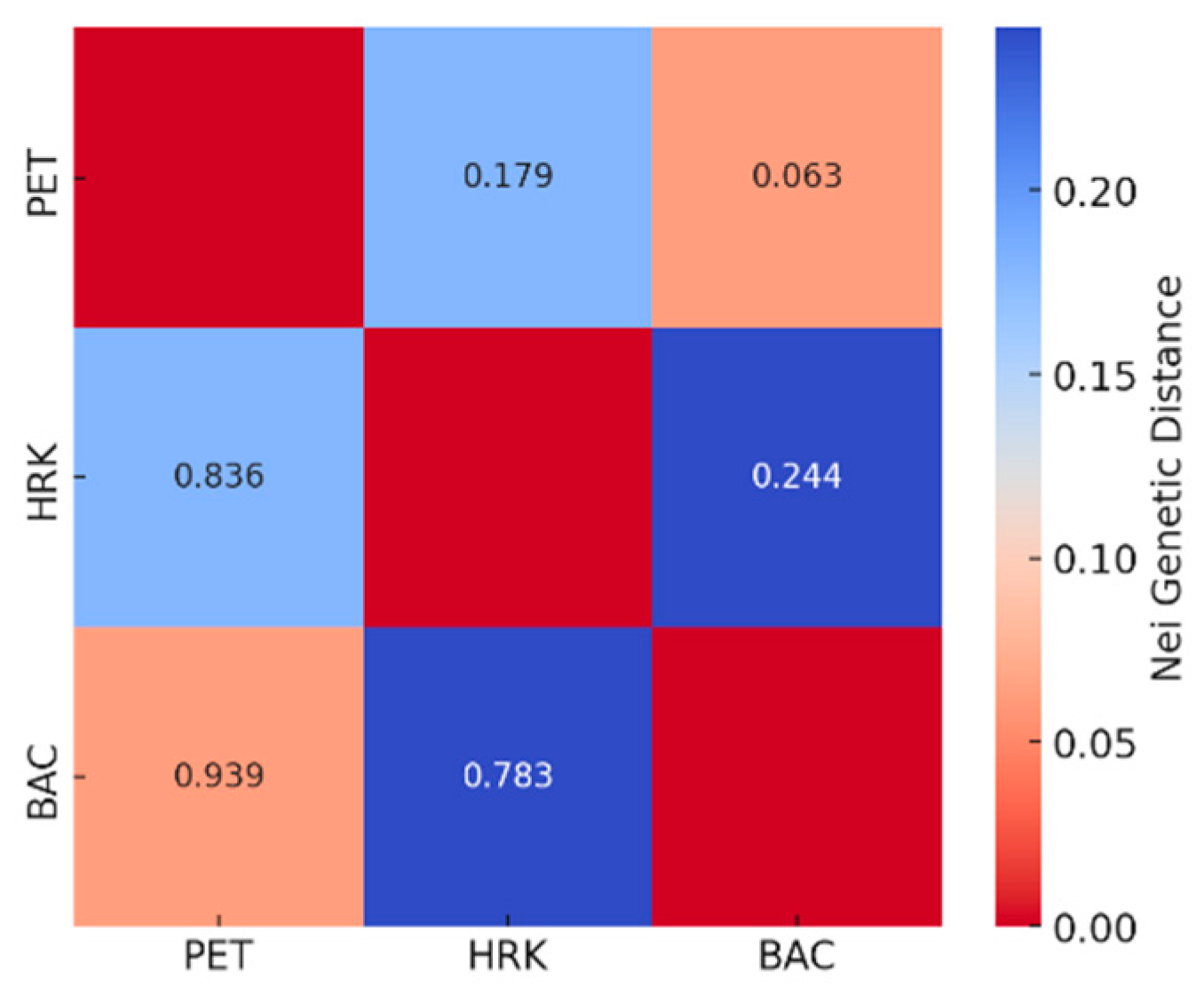

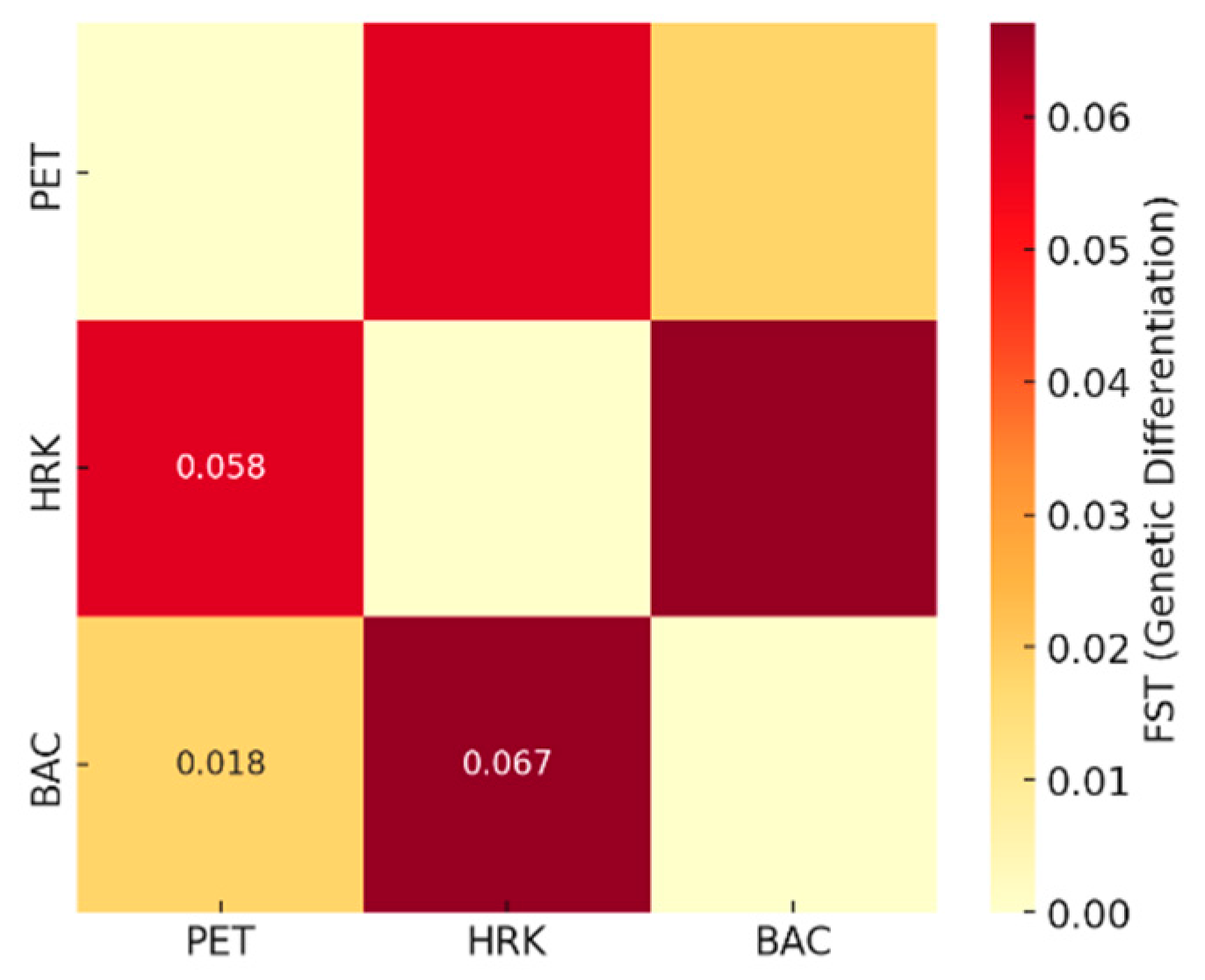

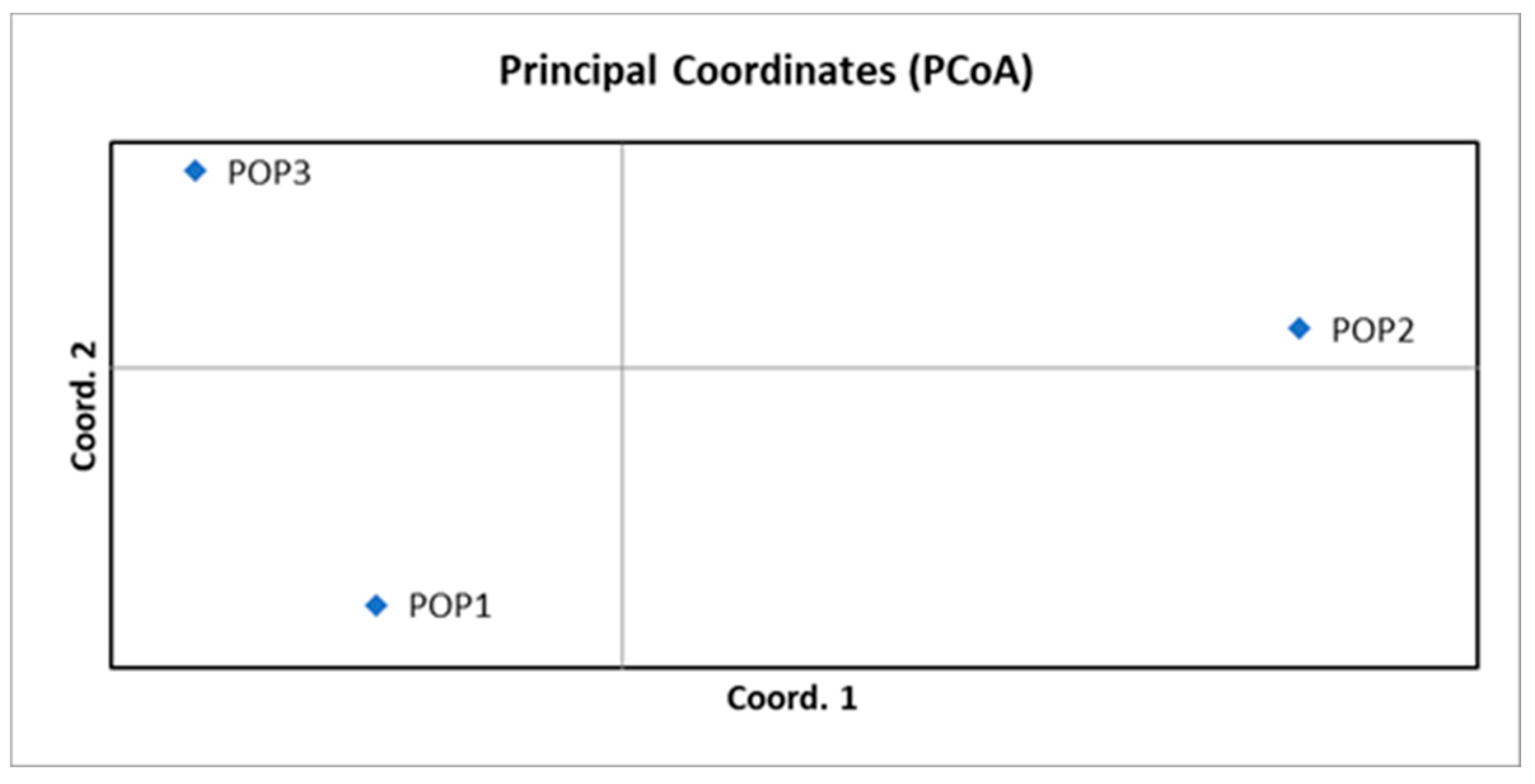

3.3. Genetic Differentiation Between Chestnut Populations: PET, HRK, and BAC

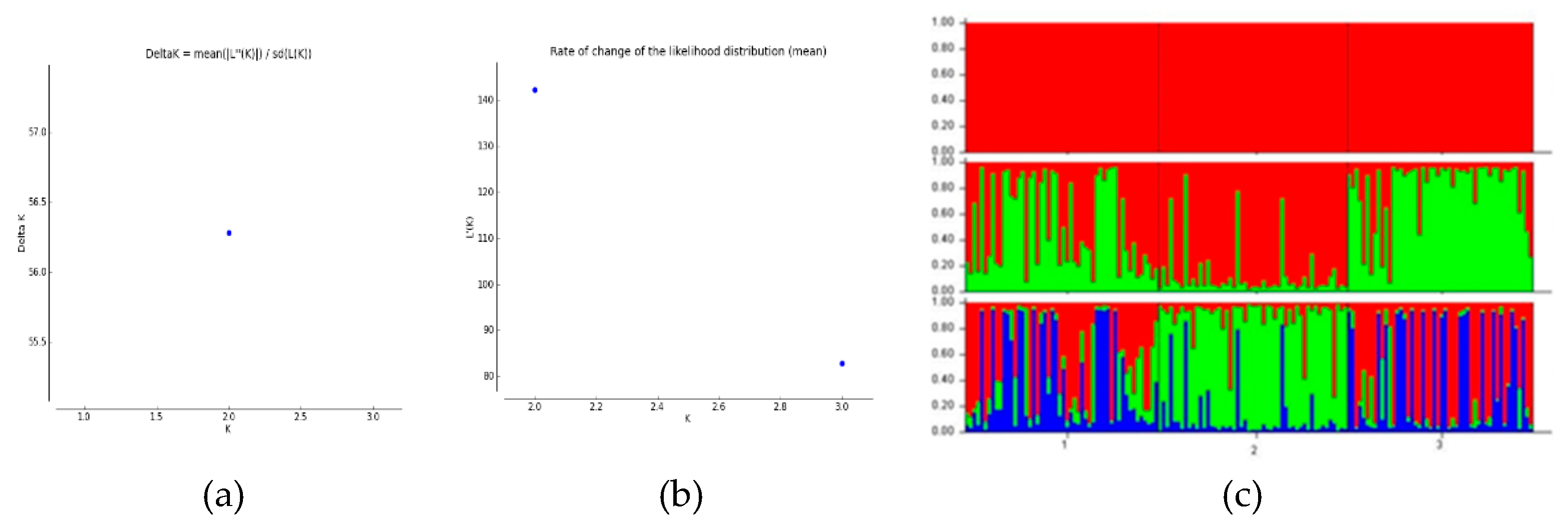

3.5. Population Genetic Structure Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. SSR Marker Performance and Genetic Resolution

4.2. Genetic Diversity and Allelic Patterns

4.3. Population Differentiation

4.4. Population Structure Patterns

4.5. Implications for Conservation and Genetic Resource Management

4.6. Conservation Implications for European Chestnut

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Conedera, M.; Tinner, W.; Krebs, P. The cultivation of sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa (Mill.)) in Europe, from its origin to the present spread and decline. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2016, 25, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López, J.; Alía, R. EUFORGEN Technical Guidelines for Genetic Conservation and Use for European Chestnut (Castanea sativa); International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy, 2003; 6p, Available online: https://www.euforgen.org/fileadmin/templates/euforgen.org/upload/Publications/Technical_guidelines/Technical_guidelines_Castanea_sativa.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Conedera, M.; Manetti, M.C.; Giudici, F.; Amorini, E. Distribution and economic potential of the sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Europe. Ecol. Mediterr. 2004, 30, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumpa, T.; Islam, M.T.; Chowdhury, M.S.H.; Nath, T.K. Coppicing behavior and carbon sequestration potential of sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa): A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthos, I.; Tsiripidis, I.; Kazoglou, Y.; Papaioannou, C.; Fotiadis, G. Genetic and ecological insights into marginal chestnut populations in northern Greece. Forests 2025, 16, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiniger, U.; Rigling, D. Biological control of chestnut blight in Europe. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1994, 32, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Plant Health. Risk assessment of Dryocosmus kuriphilus for the EU territory. EFSA Journal 2010, 8, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettraino, A.M.; Natili, G.; Anselmi, N.; Vannini, A. Recovery and pathogenicity of Phytophthora species associated with ink disease of chestnut in Italy. Plant Pathol. 2005, 54, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, C.; Martin, M.A.; Chiocchini, F.; Cherubini, M.; Gaudet, M.; Villani, F. Genetic structure of European sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) populations: Evidence from nuclear microsatellite markers. Ann. For. Sci. 2013, 70, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffartigue, N.; Curt, T.; Rey, F.; Bouchaud, M. Cultivated–wild hybridization and genetic introgression in chestnut. Ann. For. Sci. 2020, 77, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasoli, M.; Derory, J.; Morera-Dutrey, C.; Brendel, O.; Porth, I.; Scotti-Saintagne, C.; Bodénès, C.; Kremer, A.; Villani, F. Comparison of quantitative trait loci for adaptive traits between oak and chestnut based on EST-linked markers. BMC Genet. 2006, 7, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak Agbaba, S.; Liović, B.; Medak, J.; Slade, D. Chestnut Research in Croatia. Acta Hortic. 2005, 693, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medak, J. Fitocenološke značajke šuma pitomog kestena u sjeverozapadnoj Hrvatskoj [Phytocoenological Characteristics of Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa) Forests in Northwestern Croatia]; Master’s Thesis, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Forestry, Zagreb, Croatia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Medak, J. Šumske zajednice i staništa pitomog kestena (Castanea sativa Mill.) u Hrvatskoj [Forest Communities and Habitats of Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Croatia]; Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Zagreb, Croatia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Idžojtić, M.; Mlinarec, J.; Zebec, M.; Franić, R. Morphological and molecular characterization of chestnut populations in Croatia. Šum. List 2010, 134, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnock, D. Historical dimensions of the Carpathian frontier: Central Europe’s military borderlands. GeoJournal 1997, 43, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruševar, D.; Bakrač, K.; Miko, S.; Ilijanić, N.; Šparica Miko, M.; Hasan, O.; Mitić, B. Vegetation history in Central Croatia from ~10,000 Cal BC to the beginning of the Common Era—Filling the palaeoecological gap for the Western Balkans. Diversity 2023, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ježić, M.; Nuskern, L.; Peranić, K.; Popović, M.; Ćurković-Perica, M.; Mendaš, O.; Škegro, I.; Poljak, I.; Vidaković, A.; Idžojtić, M. Regional Variability of Chestnut (Castanea sativa) Tolerance Toward Blight Disease. Plants 2024, 13, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegren, H. Microsatellites: Simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004, 5, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.N.; Devey, M.E. Occurrence and inheritance of microsatellites in Pinus radiata. Genome 1994, 37, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, B.D.; Ashley, M.V.; Howe, H.F. Characterization of highly variable (GA/CT) n microsatellites in the bur oak, Quercus macrocarpa. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1995, 91, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, B.D.; Ashley, M.V. Microsatellite analysis of seed dispersal and parentage of saplings in bur oak, Quercus macrocarpa. Mol. Ecol. 1996, 5, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinkellner, H.; Fluch, S.; Turetschek, E.; Lexer, C.; Streiff, R.; Kremer, A.; Burg, K.; Glossl, J. Identification and characterization of (GA/CT)_n-microsatellite loci from Quercus petraea. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 1997, 15, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampfer, S.; Lexer, C.; Glössl, J.; Steinkellner, H. Characterization of (GA)_n microsatellite loci from Quercus robur. Hereditas 1998, 129, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexer, C.; Heinze, B.; Steinkellner, H.; Kampfer, S.; Glössl, J. Microsatellite analysis of maternal half-sib families of Quercus robur: I. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 99, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, P.R.; Michler, C.H.; Sun, W.; Romero-Severson, J. Microsatellite markers for northern red oak (Quercus rubra). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2002, 2, 472–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, E.J.; Hadonou, M.; James, C.J.; Blakesley, D.; Russell, K. Isolation and characterization of polymorphic microsatellites in European chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2003, 3, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, D.; Akkak, A.; Bounous, G.; Botta, R. DNA typing of chestnut cultivars in Italy. Acta Hortic. 2003, 622, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, C.; Martin, M.A.; Chiocchini, F.; Cherubini, M.; Gaudet, M.; Villani, F. Landscape genetics of European sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.): Indications for conservation strategies. Tree Genet. Genomes 2008, 4, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.A.; Mattioni, C.; Cherubini, M.; Taurchini, D.; Villani, F. Genetic diversity in European chestnut populations by means of genomic and genic microsatellite markers. Tree Genet. Genomes 2010, 6, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Barreneche, T. Analysis of the genetic diversity and structure of chestnut cultivars from Spain and France using microsatellites. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2010, 156, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, F.; De Lorenzis, G.; Marconi, G.; D’Angiolillo, F.; Bounous, G.; Cherubini, M.; et al. Genetic diversity and differentiation of European chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Italy. Tree Genet. Genomes 2019, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, C.; Martin, M.A.; Pollegioni, P.; Choimet, C.; Villani, F. Landscape genetics structure and conservation priorities in Castanea sativa populations. Tree Genet. Genomes 2020, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, G.; Giannini, R.; Mattioni, C.; Cherubini, M.; Villani, F. Patterns of genetic variation in European chestnut and conservation strategies. Forests 2024, 15, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idžojtić, M.; Zebec, M.; Mlinarec, J.; Franić, R. Genetic characterization of Lovran Marron chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Croatia. Šum. List 2012, 136, 283–291. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/94589 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Prgomet, S.; Poljak, I.; Jukić, D.; Idžojtić, M.; Hanzer, V. Genetic Diversity of Chestnut Populations from Istria and Gorski Kotar. Šum. List 2014, 138, 415–422. Available online: http://www.sumari.hr/sumlist/gootxt.asp?id=201411&s=27 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Poljak, I.; Idžojtić, M.; Šatović, Z.; Ježić, M.; Ćurković Perica, M.; Simovski, B.; Acevski, J.; Liber, Z. Genetic Diversity of the Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Central Europe and the Western Part of the Balkan Peninsula, and Evidence of Marron Genotype Introgression into Wild Populations. Tree Genet. Genomes 2017, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croatian Forest Research Institute. Protection of Sweet Chestnut Forests, 2006-2010. Available online: https://www.sumins.hr/projekti/zastita-suma-pitomog-kestena/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Croatian Forest Research Institute. Experimental Chestnut Grove, 2013-2015. Available online: https://www.sumins.hr/projekti/pokusni-nasad-pitomog-kestena-gornja-bacuga/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A Rapid DNA Isolation Procedure for Small Quantities of Fresh Leaf Tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—An update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Liu, J.X. STRUCTURESELECTOR: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, M.; Rosenberg, N.A. CLUMPP: A cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.A. DISTRUCT: A program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2004, 4, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthos, I.; Sotiropoulos, T.; Karapetsi, L.; Xanthopoulou, A.; Madesis, P. Genetic characterization of Greek chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) germplasm collections in Parnon Mountain—AMOVA indicates high within-individual variation (~84%) and low between-region differentiation (ΦPT ≈ 0.222, p < 0.001). Not. Bot. Horti Agrobo. 2025, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guichoux, E.; Lagache, L.; Wagner, S.; Chaumeil, P.; Léger, P.; Lepais, O.; Lepoittevin, C.; Malausa, T.; Revardel, E.; Salin, F.; Petit, R.J.; et al. Current trends in microsatellite genotyping. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2011, 11, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, K.A.; Toonen, R.J. Microsatellites for ecologists: A practical guide to using and evaluating microsatellite markers. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, C.; Martin, M. A.; Chiocchini, F.; Cherubini, M.; Gaudet, M.; Pollegioni, P.; Velichkov, I.; Jarman, R.; Chambers, F. M.; Paule, L.; Damian, V. L.; Crainic, G. C.; Villani, F. Landscape Genetics Structure of European Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill): Indications for Conservation Priorities. Tree Genet. Genomes 2017, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, R.J.; Hampe, A.; Cheddadi, R. Climate changes and tree phylogeography in the Mediterranean. Taxon 2005, 54, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, J.L.; Godt, M.J.W. Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1996, 351, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, A.; Iriondo, J.M.; Torres, M.E. Spatial analysis of genetic diversity as a tool for plant conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 113, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austerlitz, F.; Garnier-Géré, P. Evolutionary models of seed dispersal and genetic diversity. Heredity 2003, 91, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Smouse, P.E.; Quattro, J.M. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: Application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 1992, 131, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Barreneche, T. Genetic variability and structure of local chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) populations from northwestern Spain. Tree Genetics & Genomes 2010, 6, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatkin, M. Gene flow and the geographic structure of natural populations. Science 1987, 236, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holderegger, R.; Kamm, U.; Gugerli, F. Adaptive vs. neutral genetic diversity: Implications for landscape genetics. Landscape Ecol. 2006, 21, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatkin, M. A measure of population subdivision based on microsatellite allele frequencies. Genetics 1995, 139, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, F.; Boivin, T.; Bousquet, J.; et al. . Conserving adaptive genetic diversity in forest trees. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 197, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravanopoulos, F.A.; et al. Population genetic structure in Mediterranean forest trees. Forests 2015, 6, 909–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jump, A.S.; Peñuelas, J. Running to stand still: adaptation and the response of plants to rapid climate change. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 8, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskela, J.; Buck, A.; Teissier du Cros, E. Conserving forest genetic resources in Europe; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: http://www.euforgen.org/fileadmin/bioversity/publications/pdfs/1216.pdf.

- FAO. State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3825e/i3825e.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- de Cuyper, B.; Muzikar, P.; Aravanopoulos, F.; Westergren, M.; Koskela, J.; Bozzano, M.; Brožová, Z.; Collin, E.; de Vries, S.M.G.; Ducousso, A.; Frank, A.; Kramer, K.; Lefèvre, F.; Kraigher, H. Guidelines for Conservation and Use of Forest Genetic Resources. Forests 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Location Description |

Latitude / Longitude |

Altitude (m) | Ownership | Sampling Year | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | Department 47a, Management Unit Vučjak–Tješnjak, Forest Office Petrinja, Forest Administration Sisak, Croatian Forests Ltd. | 45.416972°N, 16.255232° E | 170–390 | State forest | 2011 | 52 |

| HRK | Department 90a, Management Unit Šamarica I, Forest Office Hrvatska Kostajnica, Forest Administration Sisak, Croatian Forests Ltd. |

45.229502°N, 16.493670° E | 140–240 | State forest | 2013 | 51 |

| BAC | Hrastovička Gora | 45.386900°N, 16.273600° E | 374 | Private forest | 2016 | 50 |

| Locus | Label | 5'-3' Sequences (F / R) | Expected Length (bp) | Repeat Motif | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMCs2 | NED | GCTGATATGGCAATGCTTTTCCTC/ GCCCTCCAGCCTCACTTCATCAG | 172–178 | (CGG)₇ | [27] |

| EMCs10 | PET | GTCTCCCCCAATCATAAGTAGGTC/ TCAAGGGAACATTAGGTCATTTTT | 218–230 | (CA)₈ | [27] |

| EMCs13 | VIC | TAGTCGGAGTACGGGCACAG/ TGATATGAGCATTTGACTTTGATT | 158–164 | (GCA)₈ | [27] |

| EMCs15 | 6-FAM | CTCTTAGACTCCTTCGCCAATC/ CAGAATCAAAGAAGAGAAAGGTC | 089–095 | (CAC)₉ | [27] |

| EMCs17 | 6-FAM | CGCCACGATTAGCTCATTTTCA/ GAGGTAGGGTCTTCTTCGGTCATC | 210–222 | (AGC)₄(CCAA)₅ | [27] |

| EMCs25 | 6-FAM | ATGGGAAAATGGGTAAAGCAGTAA/ AACCGGAGATAGGATTGAACAGAA | 140–158 | (GA)₁₂ | [27] |

| CsCAT15 | 6-FAM | TTCTGCGACCTCGAAACCGA/ GCTAGGGTTTTCATTTCTAG | 125–160 | (TC)₁₂ | [28] |

| Parameter | EMCs2 | EMCs10 | EMCs13 | EMCs15 | EMCs17 | EMCs25 | CSCAT15 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of alleles and length (bp) | 4 (214,216, 222,226) |

10 (138,140, 144,146, 148,150, 154,156, 158,160) |

3 (155,158, 161) |

3 (79,82, 88) |

4 (156,159, 162,165) |

8 (118,120, 122,124, 128,132, 134,138) |

4 (205,209, 213,217) |

36 alleles |

| Mean±SE | ||||||||

| FIS | -0.033 | 0.565 | 0.095 | -0.48 | 0.037 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.125±0.078 |

| FIT | -0.004 | 0.614 | 0.134 | 0.009 | 0.045 | 0.221 | 0.213 | 0.176±0.081 |

| FST | 0.028 | 0.112 | 0.043 | 0.055 | 0.009 | 0.104 | 0.096 | 0.064±0.015 |

| Nm | 8.689 | 1.974 | 5.55 | 4.326 | 27.342 | 2.146 | 2.36 | 7.484±3.432 |

| Population | Locus | Allele | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRK | CsCAT15 | 120 | 0,020 |

| HRK | CsCAT15 | 134 | 0,010 |

| HRK | EMCs25 | 154 | 0,029 |

| BAC | CsCAT15 | 118 | 0,010 |

| BAC | EMCs2 | 156 | 0,010 |

| BAC | EMCs25 | 144 | 0,130 |

| BAC | EMCs25 | 150 | 0,010 |

| Pop | Stat | N | Na | Ne | I | Ho | He | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | Mean | 52 | 4.143 | 2.39 | 1.015 | 0.511 | 0.569 | 0.074 |

| SE | 0.553 | 0.173 | 0.081 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.127 | ||

| HRK | Mean | 51 | 4.143 | 2.313 | 0.979 | 0.448 | 0.553 | 0.179 |

| SE | 0.508 | 0.157 | 0.071 | 0.043 | 0.036 | 0.071 | ||

| BAC | Mean | 50 | 4.429 | 2.631 | 1.096 | 0.506 | 0.59 | 0.127 |

| SE | 0.571 | 0.321 | 0.113 | 0.044 | 0.042 | 0.085 | ||

| Total | Mean | 51 | 4.238 | 2.444 | 1.03 | 0.488 | 0.571 | 0.127 |

| SE | 0.3 | 0.129 | 0.051 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.054 |

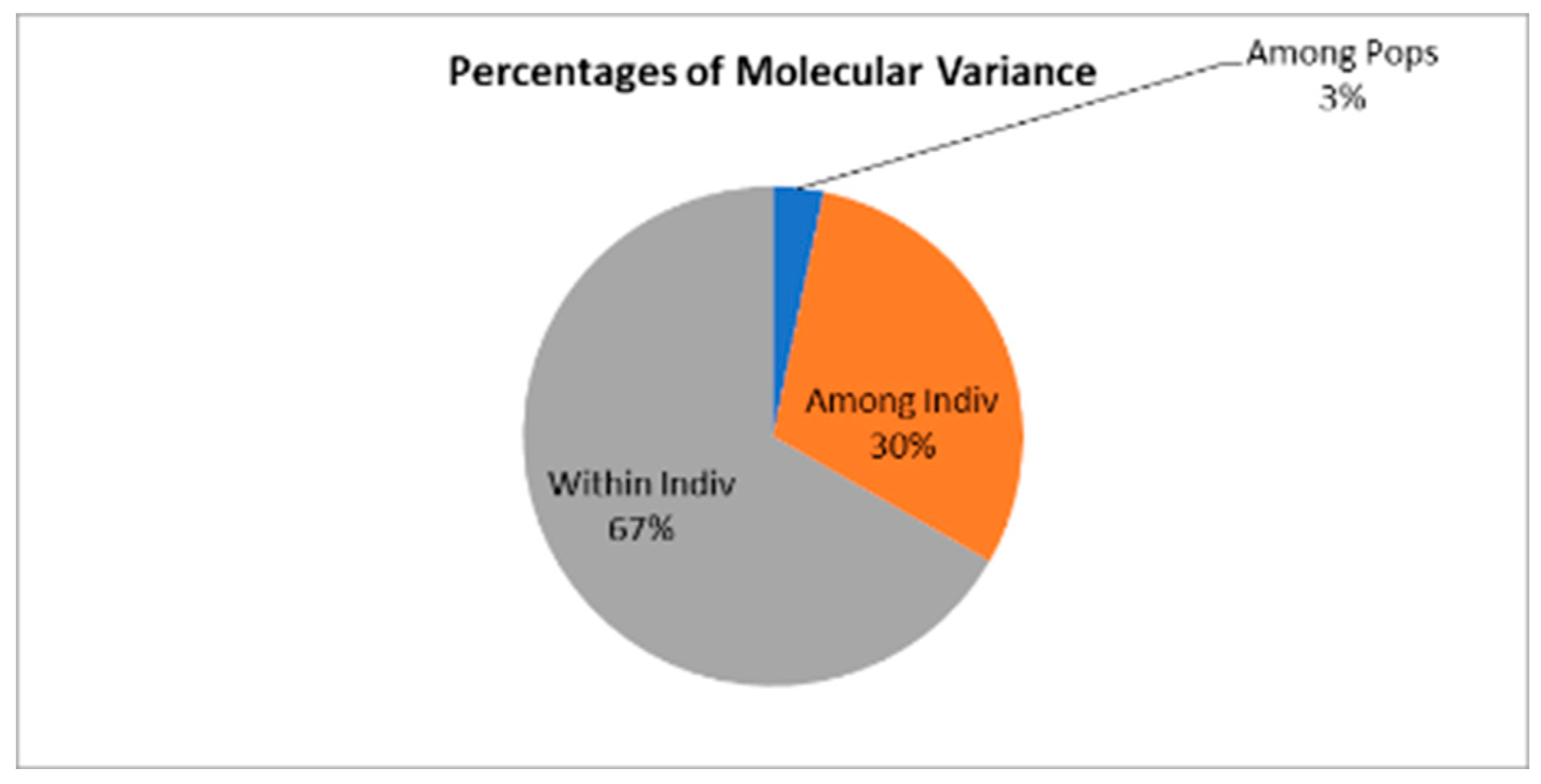

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Populations |

2 | 1542.097 | 771.048 | 5.480 | 3% |

| Among Individuals |

150 | 31826.374 | 212.176 | 50.300 | 30% |

| Within Individuals |

153 | 17071.000 | 111.575 | 111.575 | 67% |

| Total | 305 | 50439.471 | 167.355 | 100% |

| Statistic | Value | P(rand ≥ data) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RST | 0.033 | 0.001 | Among-population differentiation (stepwise model) |

| RIS | 0.311 | 0.001 | Within-individual diversity relative to subpopulations |

| RIT | 0.333 | 0.001 | Within-individual diversity relative to total population |

| Nm | 7.385 | — | Estimated gene flow (number of migrants per generation) |

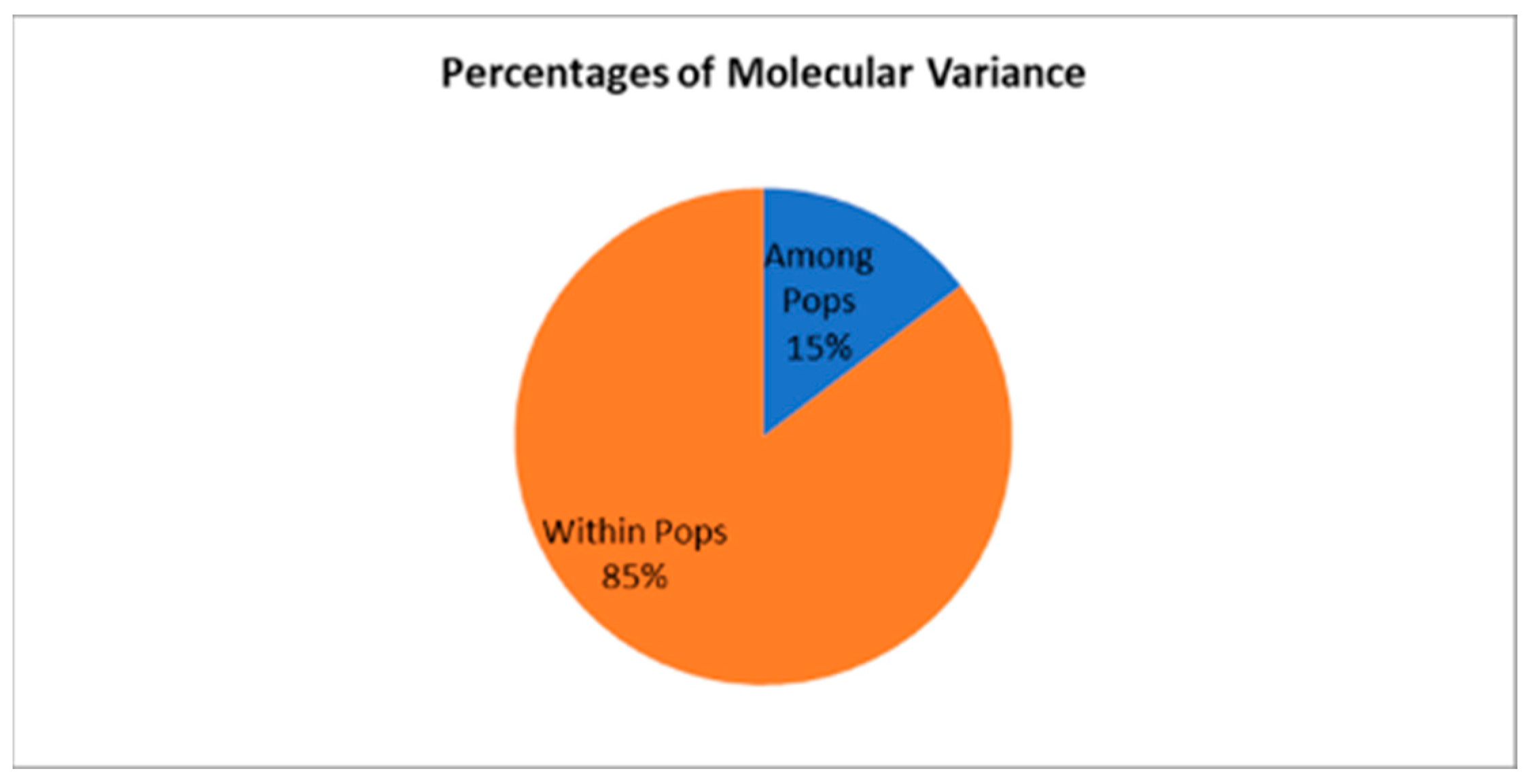

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Pops | 2 | 90.659 | 45.330 | 0.798 | 15% |

| Within Pops | 150 | 698.903 | 4.659 | 4.659 | 85% |

| Total | 152 | 789.562 | 5.457 | 100% |

| Stat | Value | P (rand ≥ data) |

|---|---|---|

| PhiPT | 0.146 | 0.001 |

| Nm | 1.461 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).