1. Introduction: Evolution of Targeted Drug Delivery Systems

The idea of targeted drug delivery has also been redefined fundamentally over recent decades from primitive liposomal aggregates to highly sophisticated nanoformulations with highly regulated surface chemistry and breath taking tissue specificity. Early liposomal formulations ruled out the possibility that drugs would be housed within biocompatible vesicles as a way of optimizing pharmacokinetics and avoiding systemic toxicity [

1].Later innovation extended application to additional nanoscale morphologies and sophisticated targeting ligands, enhancing cell entry and site-specific delivery [

2]. Nanomedicine in the treatment of cancer brought a robust impetus for the establishment of delivery systems exploiting the tumor microenvironment’s distinctive properties [

3]. These encompassed permeability and retention effects, enzyme- and pH-sensitive drug release systems for targeted drug delivery in disease tissue. Nanoparticle engineering has also provided diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy by combining these properties into a single platform—so-called “theranostic” platforms—for simultaneous imaging and treatment [

4]. Historical landmarks for the development of liposomal technology laid the groundwork for advanced delivery platforms today [

5]. Not only did these early studies confirm the viability of lipid-based encapsulation, they also offered information on current design strategies for maximizing stability, drug loading, and biodistribution. As a body of work, these innovations laid the foundations for the broad range of targeted drug delivery methods employed in clinical and preclinical practice today.

Table 1.

Introduction: Evolution of Targeted Drug Delivery Systems.

Table 1.

Introduction: Evolution of Targeted Drug Delivery Systems.

| Subsection |

Description |

| Early Liposomal Systems |

Initial liposomal constructs demonstrated that drugs could be encapsulated within biocompatible vesicles to improve pharmacokinetics and minimize systemic toxicity [1]. |

| Advances in Lipid-Based Carriers |

Lipid carriers evolved to include diverse nanoscale architectures with advanced targeting ligands, enhancing cellular uptake and site-specific release [2]. |

| Nanotechnology in Oncology |

Nanotechnology leveraged tumor-specific characteristics such as enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects, and introduced pH- and enzyme-responsive release systems for selective drug delivery [3]. |

| Theranostic Systems |

Integration of diagnostic and therapeutic functions into single nanoparticles enabled simultaneous imaging and treatment, improving precision in therapy [4]. |

| Historical Milestones |

Foundational liposome research validated lipid-based encapsulation and informed design principles for stability, drug retention, and biodistribution, shaping modern targeted delivery strategies [5]. |

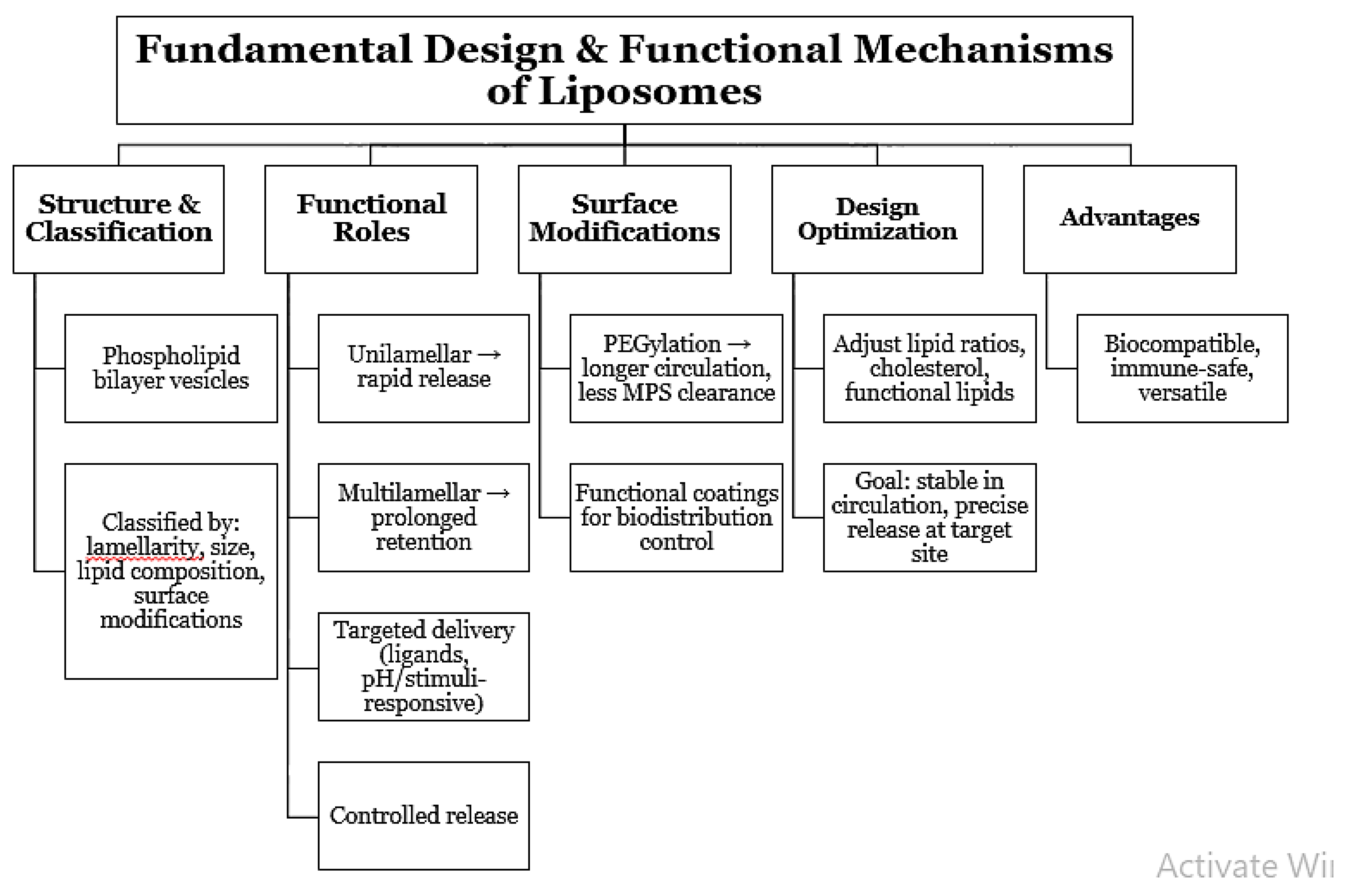

2. Fundamental Design and Functional Mechanisms of Liposomes

Liposomes are dynamic, bilayer structured, vesicular, associative systems composed of phospholipid and can systematically be categorized based on lamellarity, particle size, lipid type, and surface modification [

6], [

7]. A change in the above parameters enables regulation of pharmacokinetics, bio-distribution, and release pattern of drugs to meet the therapeutic requirement. Unilamellar vesicles, for example, are used extensively in drug delivery, whereas multilamellar structure is available for storage of long duration periods. New liposomal engineering sciences have done more than encapsulation itself. New design concepts involve the use of targeted ligands, pH-sensitive lipids, and stimulus-sensitive lipids to target drugs and control release [

8]. Surface chemistry modification like PEGylation can prolong circulation by minimizing recognition and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system. Pioneering studies involving foundations set the groundwork for liposomes to be able to interact with biological fluids without evoking considerable immune reactions so that they could act as useful biocompatible carriers [

9]. The experiments also illustrated the potential which plasma protein adsorption can have on modulating in vivo behavior, an aspect now addressed in lipid structure and coating selection. Current research stresses the optimization of lipid ratios, cholesterol levels, and the application of functional lipids to ensuring maximum stability-balancing and drug release efficiency [

10]. Optimization allows liposomes with systemic circulation stability but responsiveness to therapeutic loads to be released at target tissues. All these developments together have solidified liposomes as a cornerstone of contemporary nanomedicine.

Figure 1.

Fundamental Design and Functional Mechanisms of Liposomes.

Figure 1.

Fundamental Design and Functional Mechanisms of Liposomes.

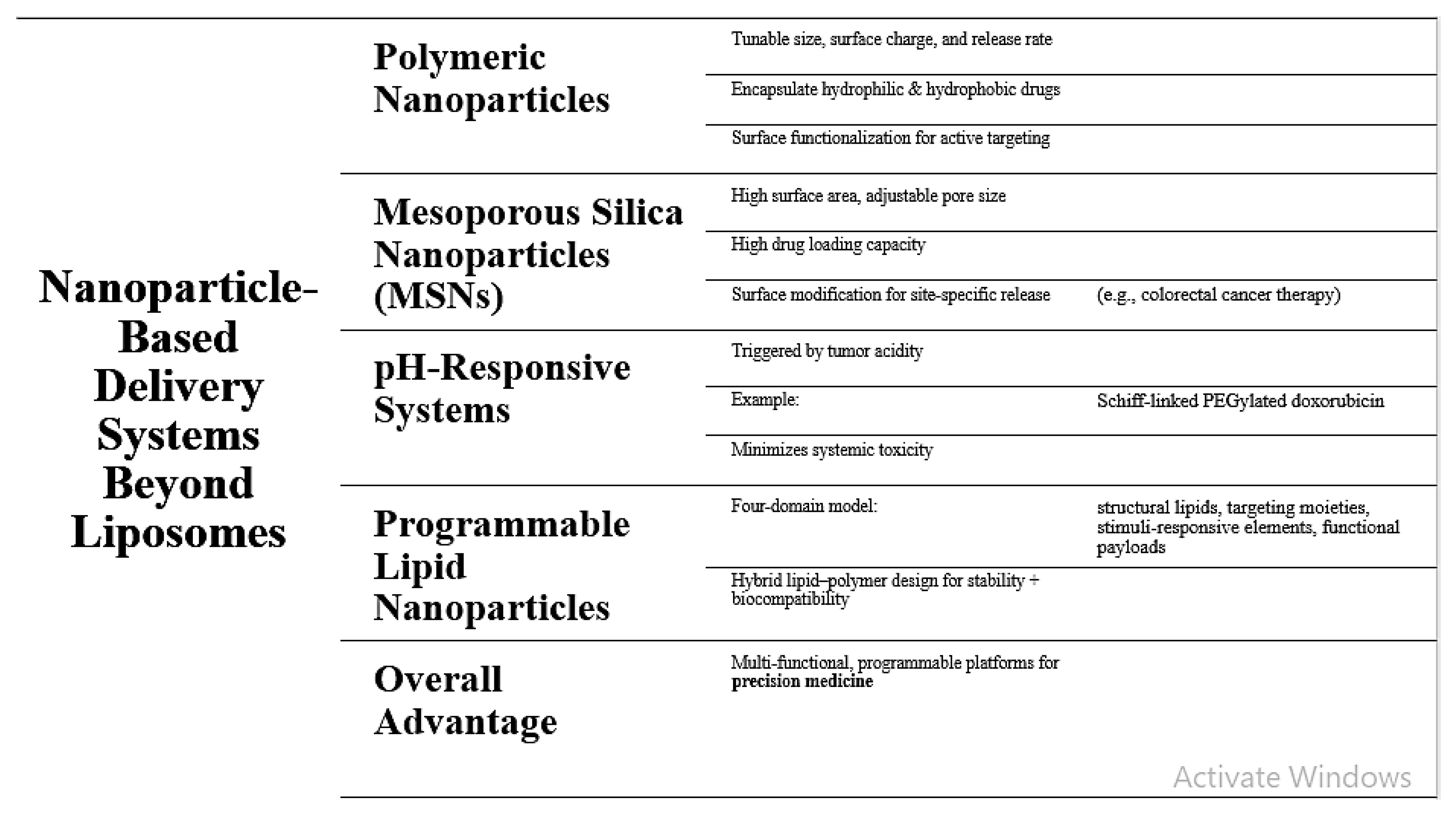

3. Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Systems Beyond Liposomes

While liposomes remain the gold standard in nanomedicine, newer nanoparticle platforms have demonstrated the added advantage of targeted drug delivery. Polymeric nanoparticles provide tunable physicochemical characteristics with complete control over size, surface charge, and drug release kinetics [

11]. Structural flexibility enables them to encapsulate hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs, and surface functionalization enables them to actively target the target tissue or cells. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) are also highly promising chemicals with tunable pore diameter, high surface area, and easy surface modification [

12]. Porosity of the particles ensures high drug loading, and release site specificity is regulated by ligands and surface coating, as demonstrated in colorectal cancer therapy. Concomitantly, pH-responsive nanoparticulate platforms such as Schiff-linked PEGylated doxorubicin prodrugs have also been engineered to respond to cancer microenvironment acidity [

13]. The systems deliver targeted trigger for drug delivery in the cancer tissue and minimizes systemic toxicity. Another recent advancement is programmable lipid nanoparticles based on a “four-domain” architectural framework combining structural lipids, target moieties, stimulus-responsive units, and functional payloads [

14]. Such hybrid lipid-polymer systems take advantage of the structural stability of synthetic polymer and the biocompatibility of lipids for both structural integrity and dynamic regulation of release mechanisms. Combined, these developments bring nanoparticle systems past the limitation of traditional liposomes to facilitate multi-functional, programmable systems of drug delivery that can be engineered for precision medicine.

Figure 2.

Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Systems Beyond Liposomes.

Figure 2.

Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Systems Beyond Liposomes.

4. Advanced Vesicular Platforms for Enhanced Therapeutics

Besides traditional liposomes, several vesicular systems—viz., proniosomes and niosomes—have been designed to address drug stability, solubility, and controlled release issues [

15]. Proniosomes, for instance, are an amorphous dry powder reconstituted to give niosomes after administration, thus shunning storage instability and risk of peroxidation. These delivery systems are extensively studied for parenteral, transdermal, and oral delivery where their capacity to entrap hydrophilic drugs and hydrophobic drugs provides drug delivery convenience [

16]. Patient compliance and pharmacokinetic profiles can be controlled by scientists with adjustments in vesicle composition and surface properties. To complement these vesicular entities, effervescent products provide a new drug delivery mode with instant disintegration, enhanced palatability, and enhanced gastrointestinal bioavailability [

17]. This can be coupled with drug vesicular carriers for patient acceptability enhancement and dosage form diversification. Another breakthrough is the application of pH-sensitive polymers in vesicular systems for site-specific drug release upon stimulation from the acidic tumor environment or endosomal compartment [

18]. Hybrid constructs have greatly improved the therapeutic ratio by ensuring drug activation at the site and reducing systemic exposure. In combination, these sophisticated vesicular platforms combine structural stability, stimulus response, and patient-dependent formulation design, a major leap towards personalized drug delivery systems.

5. Bioinspired Carriers and Hybrid Strategies

Extracellular vesicles (EVs)—biologically released nanoscale vesicles—are potential as new drug delivery vehicles due to their innate ability for targeting, immune compatibility, and biodegradability [

19]. EVs can deliver proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids across organism barriers and thus possess highly versatile therapeutic payload delivery without causing toxic immune responses. In comparison to their native conformation, scientists are also developing hybrid nanocarriers by bonding EVs with designed nanoparticles to take advantage of each system’s complementary strengths—native targeting ability of EVs and physicochemical tunability of engineered material [

20], [

21]. The hybrids are ligand functionalizable, suitable for more than one drug, and can be engineered for long circulation and penetration into deeper tissues. At the same time, plant and herbal bioactives also emerged as adjunctary drugs in drug delivery systems in combination [

22].The use of phytoconstituents like flavonoids, alkaloids, and saponins in lipid carriers not only enhances their bioavailability but also synergy with traditional medications towards a better therapeutical response. A time-honored example is the use of Tribulus terrestris fruit extracts in liposomal delivery, which exhibited targeted action and fewer side effects in the treatment of urolithiasis. Combine, bioinspired and hybrid platforms bridge the gap between the biocompatibility of nature and the tunability of engineered systems to chart the course towards precision therapeutics that are highly efficacious and tolerable.

6. Emerging Micro- and Nano-Robotic Delivery Approaches

The field of micro- and nanorobotic systems has opened up new possibilities for targeted drug delivery with unprecedented specificity in addressing the complexity of biological milieux. Magnetically operated microrobots have proven to provide controlled motility within the body, allowing site-specific delivery with less off-target exposure [

23]. They can be made biocompatible and can be loaded with various therapeutic payloads ranging from chemotherapeutic drugs to biologics. The synergy between programmable lipid nanoparticles (PLNPs) and microrobotic guidance offers an autonomous therapy synergy. PLNPs may be programmed to sense physiological signals like pH, temperature, or enzymes for on-demand release of drugs into target tissue microenvironment [

24]. With the incorporation of microrobots, carriers will not only offer spatial control but also temporal control of drug delivery, minimizing systemic toxicity and maximizing therapeutic index. This synergy of smart nanocarriers and robots is a revolutionary transition from passive to active and smart delivery and has the potential to revolutionize disease therapy with precision localization being of highest importance, for instance, deeply penetrated tumors, vascular occlusions, or pinpoint infection.

Table 2.

Emerging Micro- and Nano-Robotic Delivery Approaches.

Table 2.

Emerging Micro- and Nano-Robotic Delivery Approaches.

| Subsection |

Description |

| Magnetically Guided Microrobots |

Microrobots capable of controlled in vivo locomotion allow site-specific delivery with minimal off-target exposure. They are engineered for biocompatibility and can carry diverse therapeutic agents, including chemotherapeutics and biologics [23]. |

| Programmable Lipid Nanoparticles (PLNPs) |

PLNPs respond to physiological cues such as pH, temperature, or enzyme levels, enabling on-demand drug release within targeted tissues [24]. |

| Integration with Microrobots |

Combining microrobots with PLNPs offers both spatial and temporal precision in drug delivery, reducing systemic toxicity and improving the therapeutic index [24]. |

| Clinical Potential |

This technology enables a transition from passive to active, intelligent drug delivery, with potential applications in treating deep-seated tumors, vascular occlusions, and localized infections. |

7. Clinical Translation, Safety Challenges, and Future Outlook

Though preclinical models have been very promising from emergent delivery systems, clinic translation has the challenge of overcoming a cascade of bottlenecks. Large-scale manufacture reproducibility and transport and storage stability and regulatory compliance with extremely rigid requirements are the principal bottlenecks [

25]. The inclusion of pathological patient heterogeneity and variability in disease state adds a further complexity that requires adaptive and personalized therapy. Safety concerns—like unanticipated immunogenicity, prolonged biodistribution, and potential deposition of non-biodegradable substance—must be addressed by comprehensive toxicological characterization and continued research. Manufacture must also become economically reduced in cost to supply Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) level at no compromise on quality. In the years ahead, the union of real-time biosensing with artificial intelligence and drug delivery will revolutionize the discipline. AI will have the ability to learn formulation parameters, forecast patient-specific response, and microrobotically migrate for therapeutic targeting. Dynamically responsive smart carriers that are able to detect microenvironmental fluctuations and modulate drug release profiles in response may bring us to the edge of real personalized nanomedicine. Finally, the future of targeted drug delivery is at the nexus of materials science, robotics, data analysis, and clinical pharmacology—precisely the type of synergy that can lead us into a new therapeutic era of unmatched potency and specificity.

Conclusion

Targeted drug delivery has come a long way from primitive liposomal formulations to highly engineered nano- and micro-scale systems with unprecedented selectivity, efficacy, and versatility. Liposomes remain a pillar because they are biocompatible and whose composition can be made tunable, but nanoparticle-based carriers like polymeric nanoparticles, mesoporous silica nanocarriers, and hybrid systems offer better control over payload, environmental sensitivity, and therapeutic diversity. Vesicular systems like proniosomes and pH-sensitive vesicles offer greater stability and modes of delivery, and bioinspired extracellular vesicles offer natural targeting and immune compatibility. Future micro- and nanorobotics have integrated an active navigation capability, enabling precise localization and demand-release upon integration with programable lipid nanoparticles. Upon this advancement, transferring the same technologies into clinics is difficult in aspects of scalability in manufacturing, regulatory approvals, stability, and chronic safety. Artificial intelligence, biosensing, and adaptive smart carriers convergence is foreseen to drive the next wave of innovation to deliver targeted and highly effective therapeutics. This convergence of materials science, engineering, biology, and analytics places target drug delivery in the spotlight as the next game-changing driver in medicine.

References

- Sengar, A. (2025). Advancements in Liposomal and Nanoparticle-Based Targeted Drug Delivery. Pharm Res J, 2(1), 1–5.

- Sengar, A. (2025). Advancements in Targeted Drug Delivery: Innovations in Liposomal, Nanoparticle, and Vesicular Systems. Int J Bioinfor Intell Comput, 4(2), 1–9.

- Ferrari, M. (2005). Cancer nanotechnology: Opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer, 5(3), 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Nie, S., Xing, Y., Kim, G. J., & Simons, J. W. (2007). Nanotechnology applications in cancer. Annu Rev Biomed Eng, 9, 257–288.

- Gregoriadis, G., & Florence, A. T. (1993). Liposomes in drug delivery. Drug Dev Ind Pharm, 19(6), 785–804.

- Alavi, M., & Karimi, N. (2017). Application of various types of liposomes in drug delivery systems. Adv Pharm Bull, 7(1), 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Tseu, G. Y., & Kamaruzaman, K. A. (2023). A review of different types of liposomes and their applications. Molecules, 28(3), 1498.

- Akhter, S., Ahmad, M. Z., Ahmad, F. J., Storm, G., & Alvi, M. M. (2013). Advances in liposomal drug delivery: A review. Curr Drug Deliv, 10(5), 546–561.

- Chonn, A., Semple, S. C., & Cullis, P. R. (1992). Association of blood proteins with large unilamellar liposomes in vivo. J Biol Chem, 267(26), 18759–18765. [CrossRef]

- Large, D. E., Abdelmessih, R. G., Fink, E. A., & Auguste, D. T. (2021). Liposome composition in drug delivery: design, synthesis, characterization, and clinical application. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 176, 113851.

- Zielińska, A., Carreiró, F., Oliveira, A. M., Neves, A., & Pires, B. (2020). Polymeric nanoparticles: Production, characterization, toxicology and ecotoxicology. Molecules, 25(16), 3731.

- Mann, R. A., Hossen, M. E., Withrow, A. D. M., Burton, J. T., Blythe, S. M., & Evett, C. G. (2024). Mesoporous silica nanoparticles-based smart nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery in colorectal cancer therapy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.18809.

- Song, J., Xu, B., Yao, H., Lu, X., & Tan, Y. (2021). Schiff-linked PEGylated doxorubicin prodrug forming pH-responsive nanoparticles with high drug loading and effective anticancer therapy. Front Oncol, 11, 701. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Chen, J., Xu, M., Gracias, D. H., Yong, K.-T., Wei, Y., & Ho, H.-P. (2024). Advancements in programmable lipid nanoparticles: Exploring the four-domain model for targeted drug delivery. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.05695.

- Sengar, A., Saha, S., Sharma, L., Hemlata, Saindane, P. S., & Sagar, S. D. (2024). Fundamentals of proniosomes: Structure & composition, and core principles. World J Pharm Res, 13(21), 1063–1071.

- Sengar, A. (2025). Liposomes and Beyond: Pioneering Vesicular Systems for Drug Delivery. J BioMed Res Reports, 7(1), 1–6.

- Sengar, A., Tile, S. A., Sen, A., Malunjkar, S. P., Bhagat, D. T., & Thete, A. K. (2024). Effervescent tablets explored: Dosage form benefits, formulation strategies, and methodological insights. World J Pharm Res, 13(18), 1424–1435.

- Zhang, X., Zhang, T., Ma, X., Wang, Y., & Lu, Y. (2020). The design and synthesis of dextran-doxorubicin prodrug-based pH-sensitive drug delivery system for improving chemotherapy efficacy. Asian J Pharm Sci, 15(5), 605–614. [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M., Siljander, P. R., Andreu, Z., Zavec, A. B., Borràs, F. E., Buzas, E. I., ... & De Wever, O. (2015). Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles, 4(1), 27066. [CrossRef]

- Puglia, C., Bonina, F., & Puglisi, G. (2004). Evaluation of in-vivo topical anti-inflammatory activity of indometacin from liposomal vesicles. J Pharm Pharmacol, 56(10), 1225–1232. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R. K., & Stylianopoulos, T. (2010). Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 7(11), 653–664. [CrossRef]

- Sengar, A. et al. (2025). Advancing urolithiasis treatment through herbal medicine: A focus on Tribulus terrestris fruits. World J Pharm Res, 14(2), 91–105.

- Landers, F. C., Hertle, L., Pustovalov, V., Sivakumaran, D., Brinkmann, O., Meiners, K., ... & Nelson, B. J. (2025). Clinically ready magnetic microrobots for targeted therapies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.11553.

- Sengar, A. (2024). Precision in Practice: Nanotechnology and Targeted Therapies for Personalized Care. Int J Adv Nano Computing & Analytics, 3(2), 56–67. [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S., Ahmad, M. Z., Ahmad, F. J., Storm, G., & Alvi, M. M. (2013). Advances in liposomal drug delivery: A review. Curr Drug Deliv, 10(5), 546–561.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).