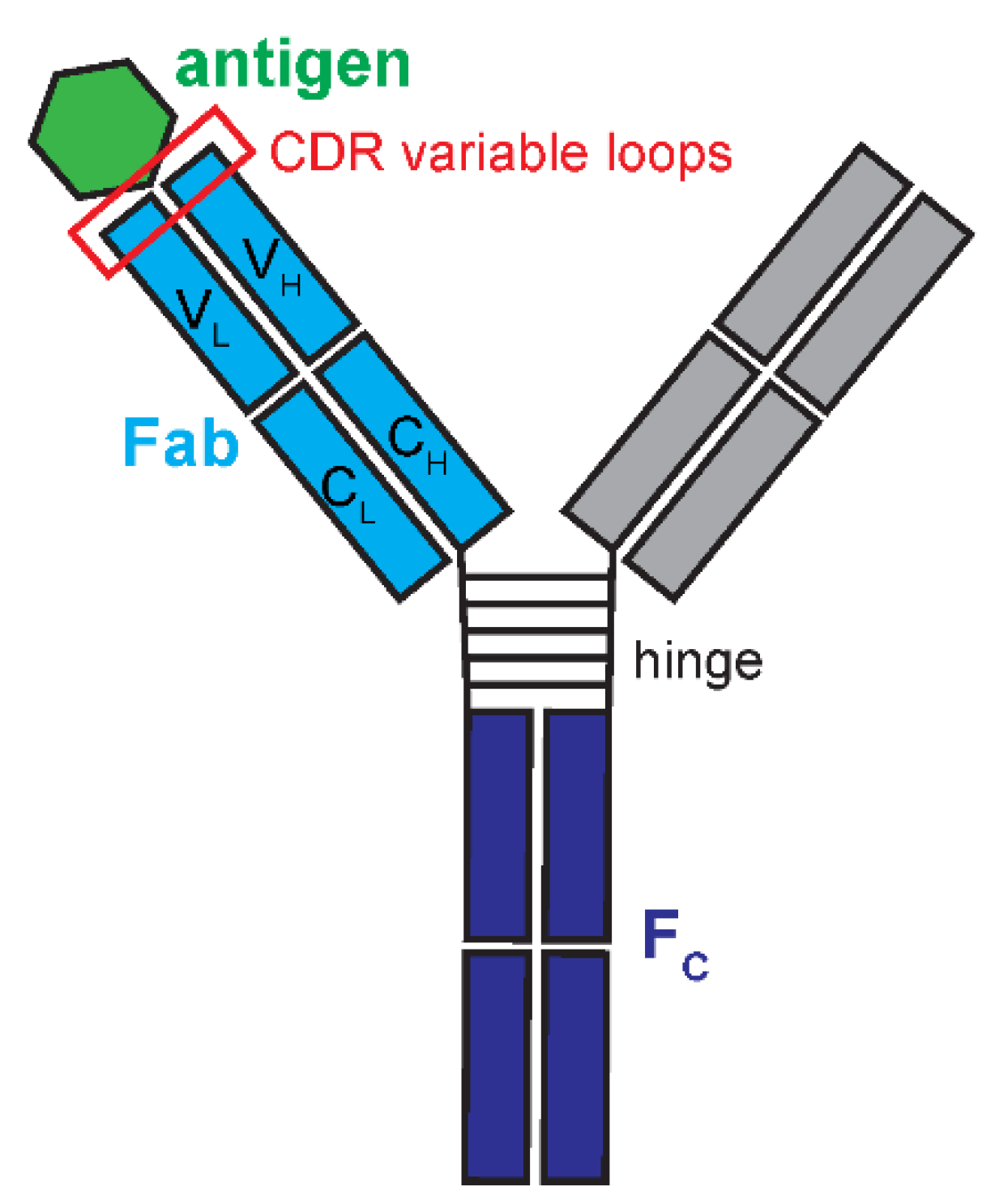

Antibody Structure

IgG is composed of 4 polypeptide chains crosslinked together and structurally arranged into a ‘Y’ shaped molecule (

Figure 1). Two 50 kilodalton (kDa) heavy chains and two 25 kDa light chains are bonded by covalent disulfide bridges (

Vidarsson et al. 2014). The IgG arms of the ‘Y’ are the fragment antigen-binding regions (Fab) that directly bind to their molecular target. The base of the ‘Y’ is the fragment crystallizable region (Fc) that holds the two arms together and used for an immunological response. Each Fab has 6 complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that typically dictate IgG binding (

Chothia and Lesk 1987). The heavy and light protein chains have three CDRs each of variable length. For example, two of the heavy chain CDRs, CDR-H1 and CDR-H2, are typically 8 amino acids (

Mejias-Gomez et al. 2023), while the third heavy chain CDR, CDR-H3, range from 8-25 amino acids (

Mejias-Gomez et al. 2023). Lengths as low as 4 residues or as high as 36 residues do exist, although rare (

Mejias-Gomez et al. 2023). The unique CDR sequence combinations form a structural arrangement unique for that antibody. Thus, the CDRs permit a wide breadth of antibody binding and specificities.

Antibody-antigen interactions can be incredibly strong, leading to low dissociation equilibrium constants (KDs). For example, a monoclonal antibody was reported to have a KD of 66 pM for its target antigen (Landry et al. 2015). Assuming this interaction has a typical association rate constant (KON, 1 × 10⁶ M⁻¹·s⁻¹), then the binding half-life of this interaction is estimated to be almost 3 hours. This is astounding when considering that potent drugs may have binding affinities that equate to binding half-lives of approximately 12 minutes. Strong antibody binding affinity originates from its CDRs. The CDRs create the antibody binding region paratope complementary to the corresponding target epitope (Stanfield and Wilson 2014; Vidarsson et al. 2014; Myung et al. 2023). This binding interaction is largely driven by the third heavy chain (H3) CDR. H3 is unique because of its variable length compared to the other five CDRs. Different H3 loop lengths create diversity in antibody binding specificities as the H3 length alters the contributions of the other CDR loops for its paratope shape (Tsuchiya and Mizuguchi 2016). Short H3 loops create concave CDR regions to allow for all 6 loops to interact with the antigen. Long H3 loops form a convex surface, and the H3 loop dominates the interactions. Thus, the H3 loop is a key determinant in antigen binding specificity due to its unique biochemical properties versus the other CDR loops.

Antibody Diversification

In humans, up to 1012 unique antibodies are proposed to exist (Alberts 2002). One might assume that an enormous number of genes encode these antibody structures. However, all antibodies originate from only around 140 gene segments. The process of getting from hundreds of genes to a large portfolio of antibodies is through a mechanism known as V(D)J recombination and is reviewed more extensively elsewhere (e.g., (Chi et al. 2020; Lebedin and de la Rosa 2024)). Antibody encoding-genes are divided into three groups: V, D, and J segments. Human heavy chains have 51 V, 27 D and 6 J segments, while human light chains encode for 40 V and 5 J segments but lack D segments (Alberts 2002; Chi et al. 2020; Lebedin and de la Rosa 2024). One of each gene segment is selected randomly to create a chain. Segment joining introduces additional variability. When the DNA is recombined, a random number of bases can be lost or gained at the recombined ends to introduce potentially large variations. Antibody sequences are further diversified through a maturation process and somatic hypermutation (SHM). As the animal is exposed to antigens, it selects for improved antibody affinity through a maturation process. SHM creates point mutations in antibody V,D, and J segments (Chi et al. 2020; Lebedin and de la Rosa 2024). Antibodies can gain affinity up to 100x that of their un-mutated counterparts (Merkenschlager et al. 2025). In sum, mechanisms such V(D)J recombination and SHM give rise to a highly diverse, highly selective IgG repertoire.

Antibody-Antigen Interactions

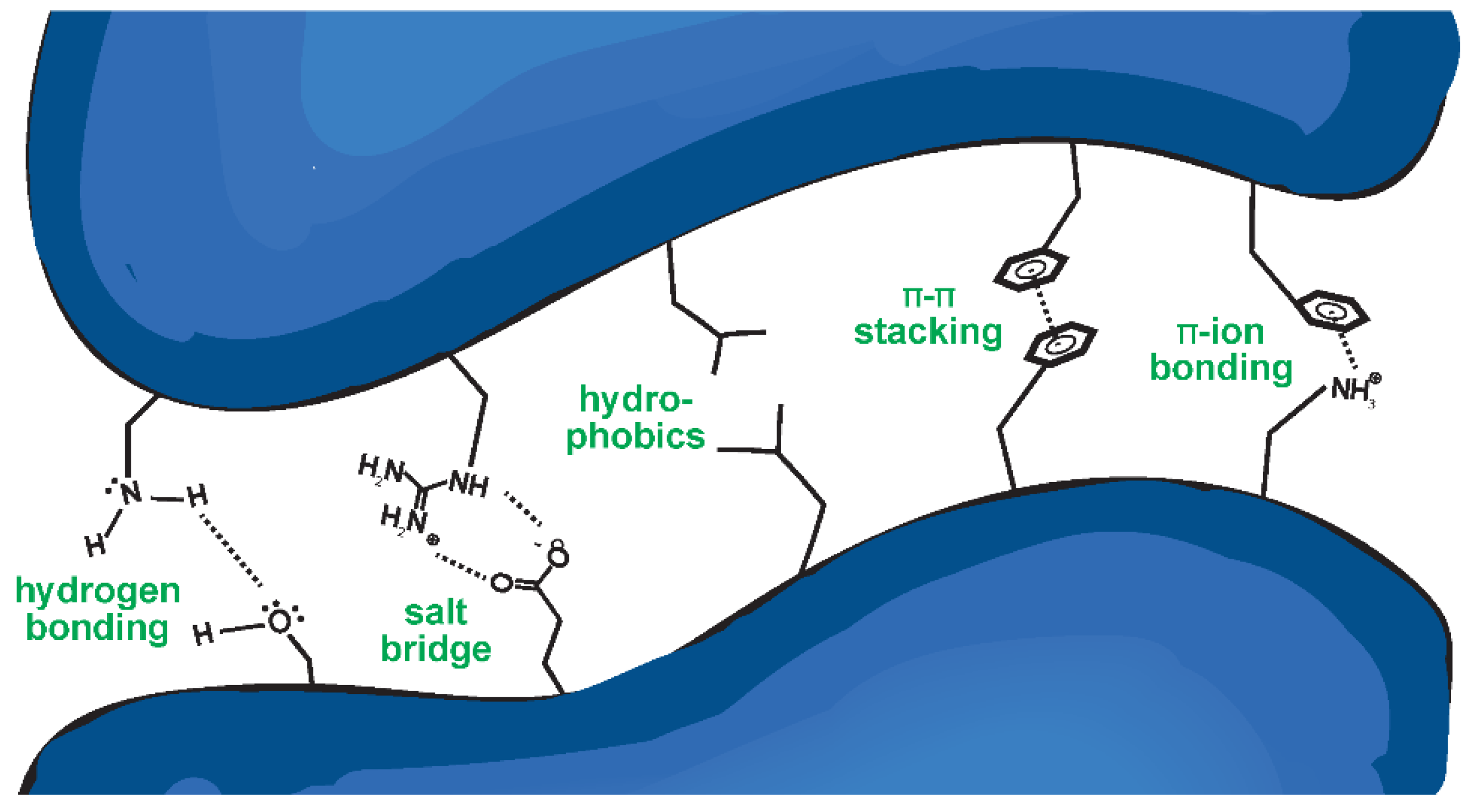

Antibody binding is governed by a wide assortment of chemical interactions (

Figure 2). These non-covalent interactions include (a) hydrogen bonding; (b) salt bridges or ionic interactions; (c) hydrophobic interactions; (d) Van der Waals forces, which occur between large nonpolar bodies (not depicted); (e) π-π stacking between aromatic side chains; and (f) π-ion bonding (

Figure 2). Hydrogen bonding is an interaction between partially charged residues—a partially positively charged hydrogen atom and a partially negatively charged atom, typically N, O, or F. Ionic interactions are electrostatic forces between two charged residues, whereas hydrophobicity contributes to binding by stabilizing the complex when non-polar residues are buried, away from water. Van der Waals forces are weak interactions operating over comparatively large surface areas, where two non-polar residues interact via local variations in charge density. Less common binding interactions involve π systems, where aromatic molecules such as phenylalanine interact by aligning their aromatic ring with either another π system, as in π-π stacking, or a charged residue, as in π-ion bonding. As they are relatively rare, they are of modest relevance to the strength of an interaction. Instead, they contribute greatly to molecular recognition, or the specificity of the binding, since π interactions are geometrically restricted and strong on a per-interaction basis (

Hunter and Sanders 1990;

Lucas et al. 2016). Each of these individual interactions are relatively weak, but, through summation of many interactions dispersed across the protein surface, the total interaction is strong (

Yang et al. 2014).

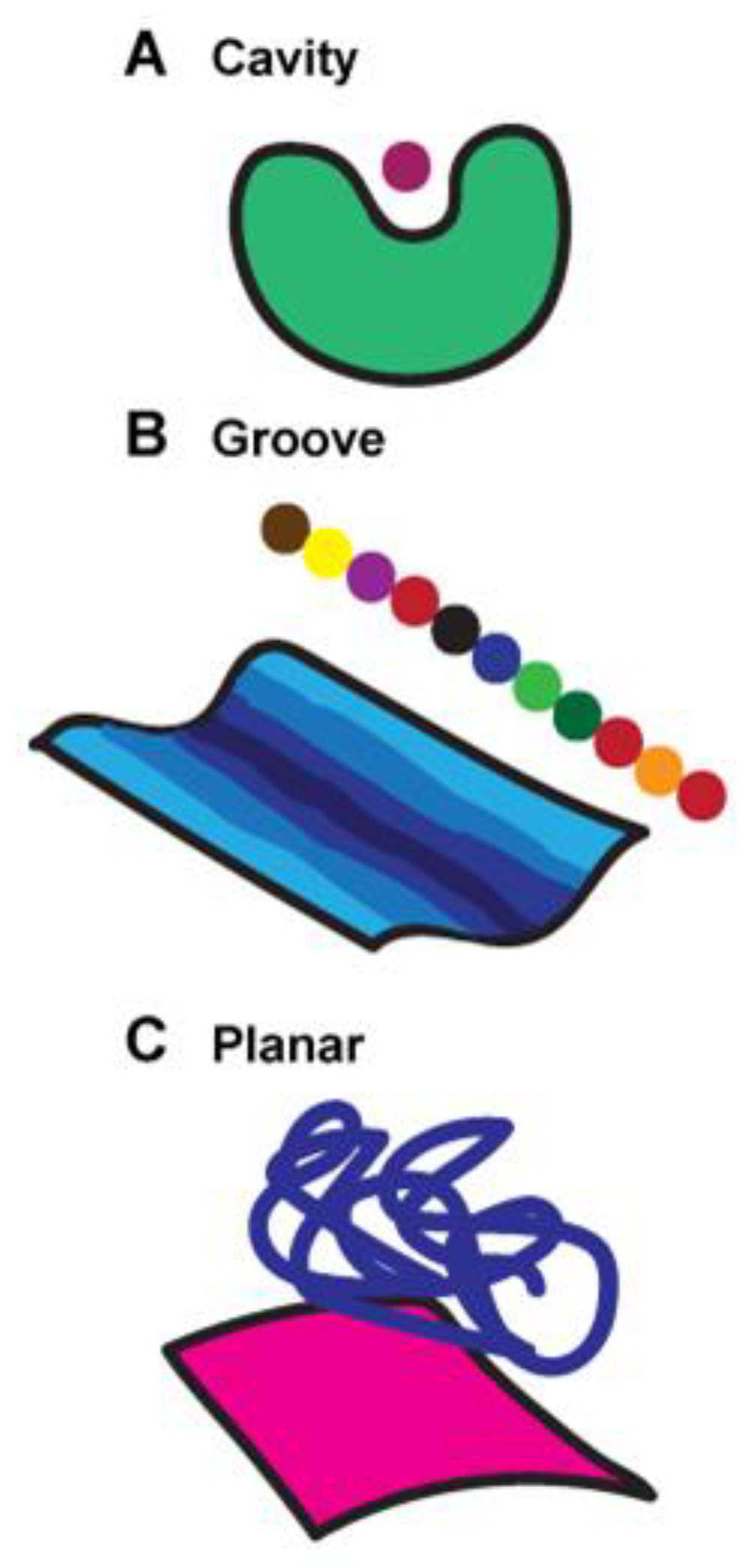

How Antibodies Recognize Their Antigen Targets

Antibodies typically use a lock and key mechanism to recognize their antigens. In this strategy, the antibody binding site is structurally arranged specifically to accommodate its target, analogous to how a key is specifically designed for a lock. The surface topography of antibody binding sites fit into three broad categories (

Rees et al. 1994) (

Figure 3): (A) cavity, (B) groove, and (C) planar. Small molecule haptens bind cavities. Peptides and other linear macromolecules, such as DNA or carbohydrates, generally bind grooves. Much larger proteins with folds bind to planes. Thus, the interaction relies on high complementarity between the antibody surface and its antigen.

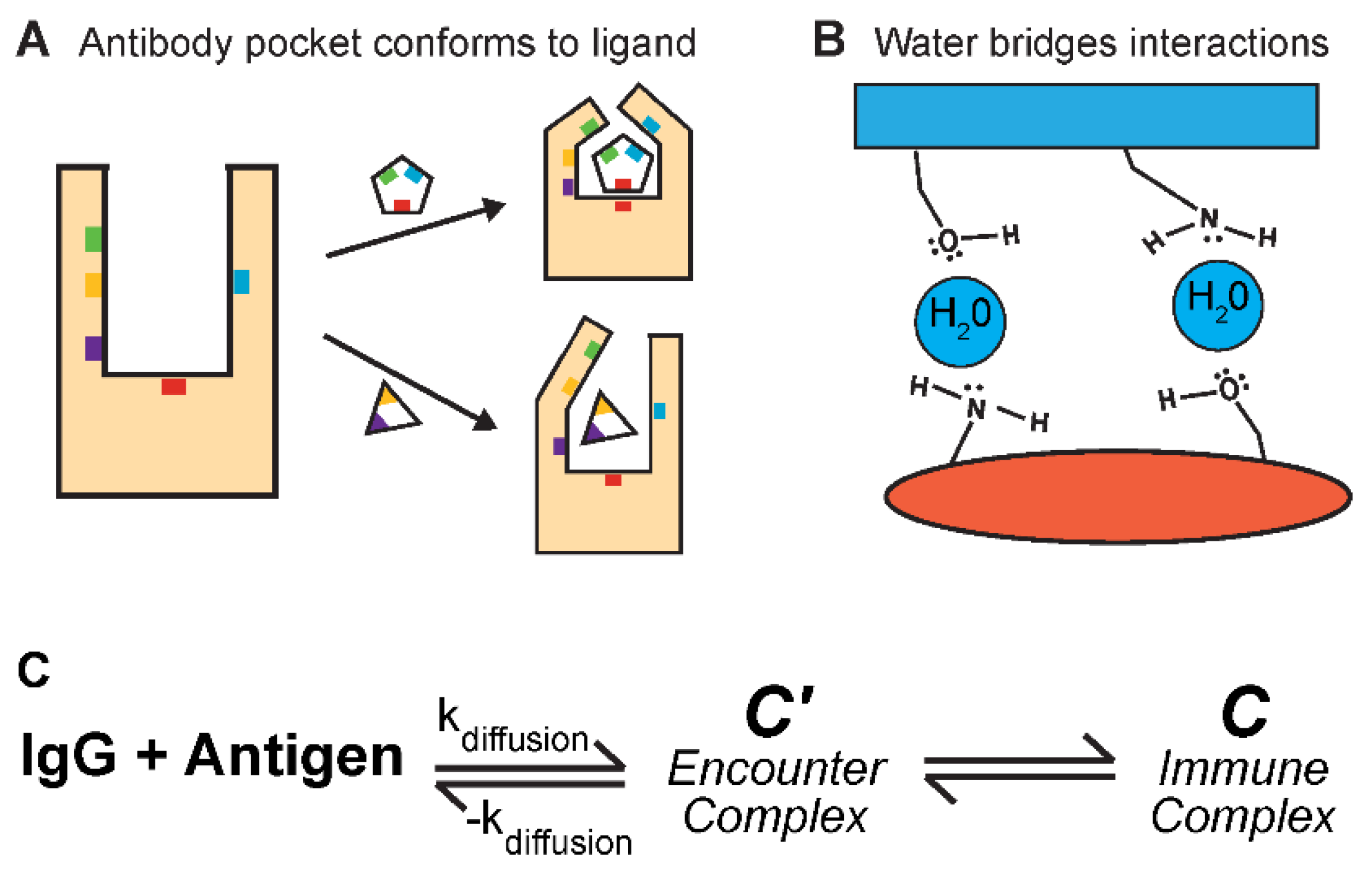

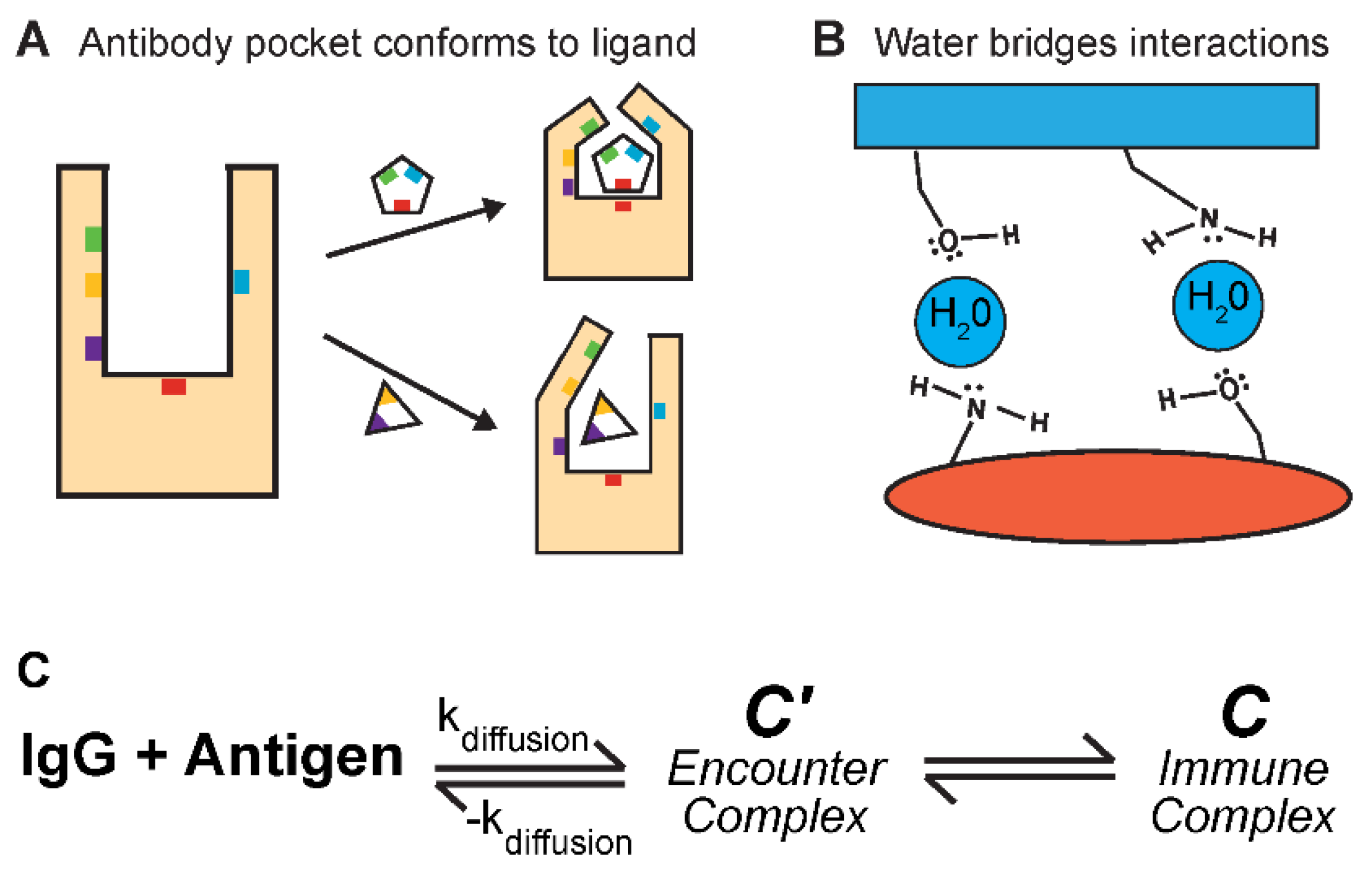

Antibody-antigen fit is not always perfect. Like enzyme-ligand interactions (

Schiebel et al. 2018;

Riziotis et al. 2022), two mechanisms can bridge the gap to permit binding (

Figure 4A,B): antibody conformational changes and water binding. Antibody conformational changes are documented (

Sela-Culang et al. 2012) (

Figure 4A), but their extent and contribution to antigen binding is not significant (

Liu et al. 2024). CDR-H3 has the most structural variation, but only approximately one-third of CDR-H3s report measurable changes (

Sela-Culang et al. 2012). The propensity for an antibody to undergo conformational changes upon binding is also dependent on the maturation of the antibody. Affinity maturation leads to higher binding affinities and increased stiffness of the antibody CDRs (

Sela-Culang et al. 2012). The presence of water molecules in antibody-antigen interactions have a more concrete and important role in binding (

Figure 4B). Water molecules can bridge molecular interactions between contacting surfaces through hydrogen bonding, strengthening the overall interactions (

Bhat et al. 1994). Additionally, water can indirectly alter the surface of an antibody paratope. Many antibodies contain cavities not directly involved in antigen binding but can have an allosteric, destabilizing effect on the target interaction (

Braden et al. 1995). Water molecules can fill these cavities and mitigate their negative effects on binding strength.

Antibody binding kinetics are enthalpy driven and exist in three states (

Galanti et al. 2016) (

Figure 4C): (1) the unbound IgG and antigen, (2) the encounter-complex (C’), and (3) the antibody-antigen immune complex (C). The unbound IgG and antigen are unassociated in solution. The encounter complex describes the random collisions between the antibody and antigen. These are weak interactions and in equilibrium with unbound molecules. The antibody-antigen complex describes a bound state. The encounter complex can convert to the immune complex for a stronger, stabler interaction. In sum, antibodies interact with their antigen pairs through a multi-step, reversable process, moving from an initially weak to a strong antibody-antigen complex.

Antibody Therapeutics

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are homogenous antibody molecules with both clinical and laboratory applications. For example, IgG mAbs are essential for molecular screening tests to test for certain antigens or biomolecules. The strength and specificity of IgG binding interactions allows for highly specific detection of immunogenic substances. In recent years, antibodies have become a more widespread therapeutic option to treat a wide variety of disorders. The four therapeutic examples below demonstrate the range of mechanisms through which antibodies help alleviate human disease.

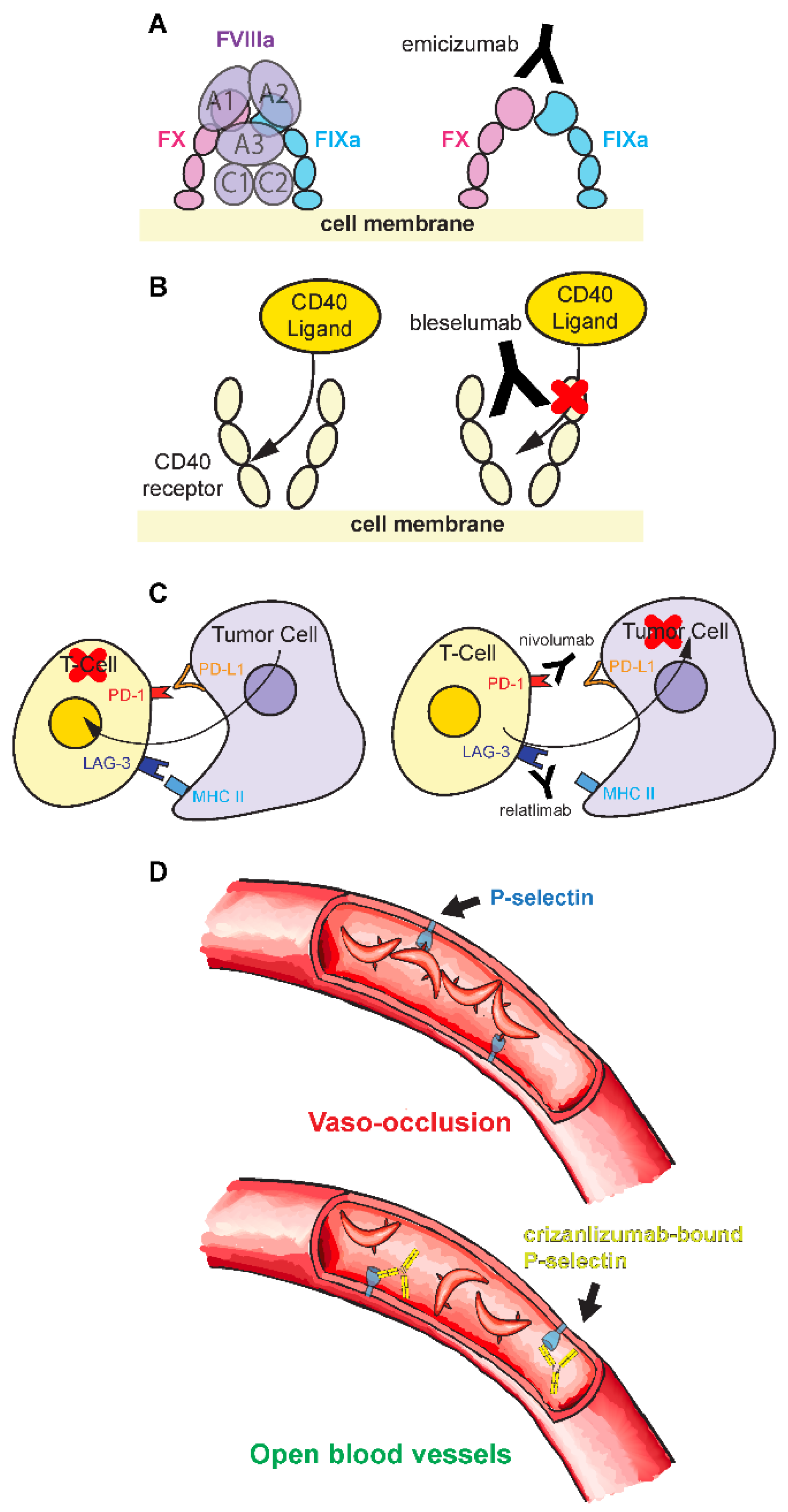

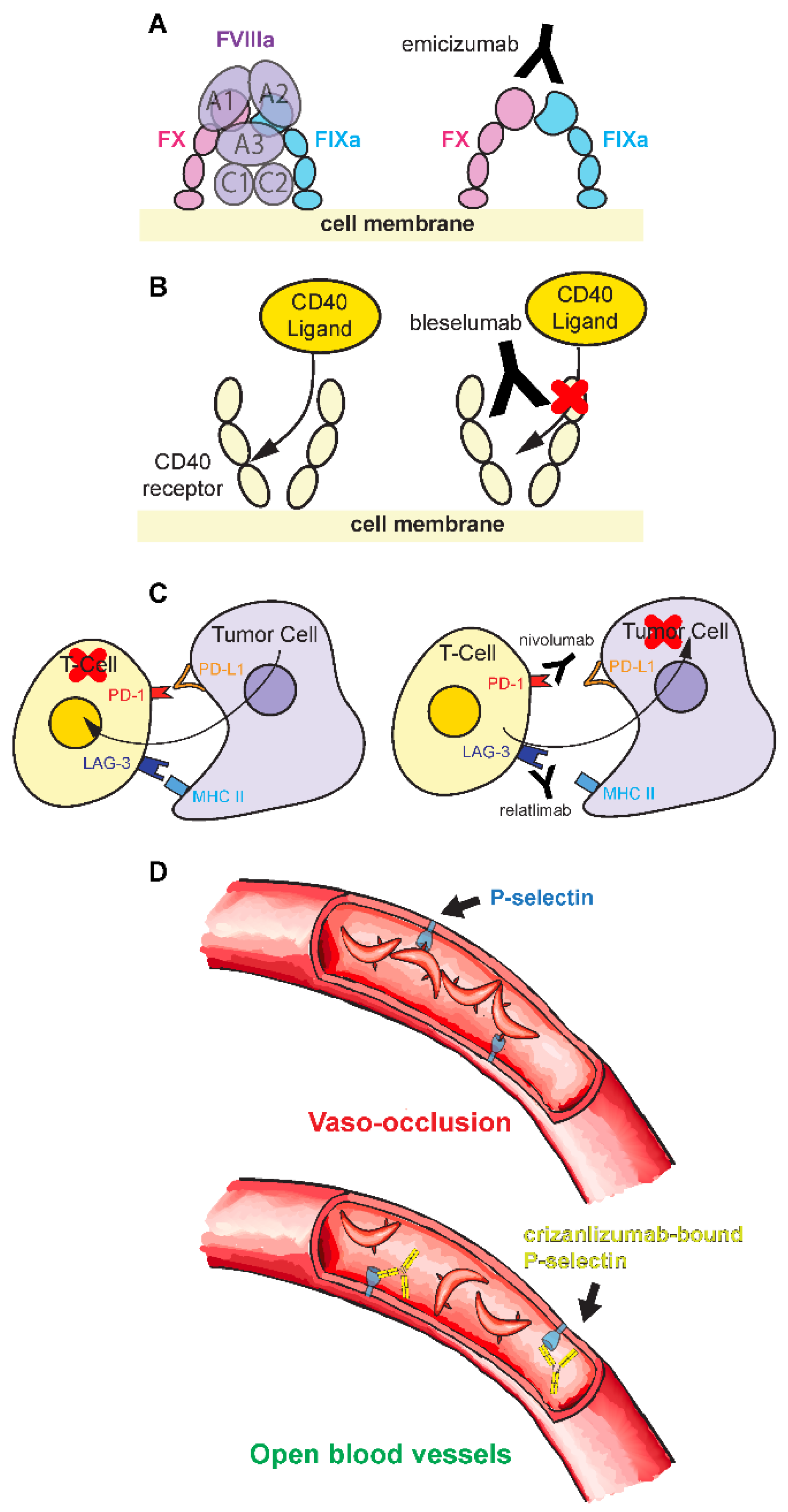

Hemophilia is an X-linked recessive genetic disorder characterized by a deficiency in blood clotting factors. It exists in two predominant types (

Bolton-Maggs and Pasi 2003;

Peyvandi et al. 2016): Hemophilia A, caused by a deficiency in factor VIII (FVIII), and Hemophilia B, caused by a deficiency in factor IX (FIX). Deficiency of these factors leads to an inability for blood to clot. The function of activated FVIII (FVIIIa) is to act as a cofactor between FX and activated FIX (FIXa) (

Figure 5A), a critical part of the coagulation cascade. Loss of FVIII in Hemophilia A inhibits this process and causes excessive bleeding. This bleeding can occur in joints, destroying cartilage and promoting early onset of arthritis; in organs or intracranially, which can be life-threatening; or intramuscularly, which is less severe yet still inhibitory (

Bolton-Maggs and Pasi 2003;

Peyvandi et al. 2016). The traditional treatment for hemophilia depends on the relative severity of the disorder but commonly is the infusion of a pure factor obtained from donor plasma or recombinant, artificial protein sources (

Giangrande 2004). While effective, factor treatment suffers from several hurdles. It must be administered frequently and in large doses. This can be troublesome as intravenous infusion is typically used, which limits the infusion rate. Second, the factor can be immunogenic (

Giangrande 2004), resulting in an immune response toward the factor products. This reaction destroys drug efficacy and possibly be fatal. In recent years, many new treatments have been explored. Emicizumab (Hemlibra (

Yoneyama et al. 2023)) is a new monoclonal antibody treatment that emulates the function of FVIIIa (

Figure 5A). Emicizumab is a bi-specific antibody, with two different variable regions, allowing it to bind to two completely unrelated proteins. This allows the antibody to serve as a functional replacement for FVIIIa, which works as a cofactor to bring factor X (FX) and FIXa proteins together to promote their interaction (

Yoneyama et al. 2023) (

Figure 5A). Emicizumab is not perfect. Its catalytic cofactor efficacy is approximately 10-fold less than FVIIIa (

Lenting et al. 2017). When emicizumab concentrations are too high, its efficacy is impeded by binding only one factor instead of bridging two factors. Lastly, the affinity of emicizumab for its target factors is much lower than FVIIIa (

Lenting et al. 2017). Regardless, emicizumab is effective and conveniently acquired compared to traditional factor products.

Numerous mAb have been developed to combat organ transplant tissue rejection by the host. One critical drug target is the CD40/CD40L pathway. CD40 is a protein receptor found in the membranes of many immune, endothelial, and epithelial cells. The pathway is activated by the CD40L ligand found on activated T-cells. Binding leads to the signaling for B cell and cytokine propagation, cell cycle regulation, and apoptosis or programmed cell death (

Harland et al. 2020). Bleselumab acts as an antagonistic immunosuppressant by blocking this pathway through sterically inhibiting the CD40 receptor binding (

Asano et al. 2024) (

Figure 5B), thus hampering the immune response. Bleselumab functions to prevent rejection while having minimal side-effects, highlighting the benefits of mAb treatments (

Harland et al. 2020).

In contrast to bleselumab, IgG therapies have also been developed that counteract immune suppression. T-cells express LAG-3 protein that binds to MHC II, a ligand highly concentrated in melanoma tumors (

Albrecht et al. 2023). MHC II bound LAG-3 hinders anti-tumor responses, primarily through slowing T-cell production and increasing T-cell functional exhaustion (

Albrecht et al. 2023;

Mariuzza et al. 2024). Relatlimab binds and blocks the LAG-3 receptor from MHC II interaction to promote T-cell proliferation (

Figure 5C). Nivolumab (Opdivo) targets a separate pathway (

Figure 5C). It binds to the PD-1 receptor found on T-cells (

Phillips and Reeves 2023) to block ligand interactions. When PD-1 binds to its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, downstream effects occur (

Chen et al. 2023), like decreased cytokine production, T-cell proliferation, hindrance of T-cell immune function, and changing T-cell metabolism. This signaling pathway ultimately kills T-cells. By binding to this receptor, nivolumab prevents the immunosuppressant effects of the PD-1 pathway, allowing the immune system to better attack malignant tumors (

Chen et al. 2023). Nivolumab and relatlimab are often used together (Opdualag) for cancers like melanoma (

Phillips and Reeves 2023).

Sickle cell disease is a heritable disorder from a hemoglobin gene mutation. This mutation changes a hydrophilic glutamate to a hydrophobic valine in the hemoglobin protein sequence (

Rees et al. 2010), causing unfolding and aggregation. This alters the cellular structure of red blood cells to produce a ‘sickled’ crescent shape. Their crescent shape causes them to get stuck together in small blood vessels, causing immense pain (

Rees et al. 2010) (

Figure 5D). This process is mediated in part by the P-selectin blood vessel protein. Crizanlizumab (Adakveo) is a P-selectin targeting mAb that reduces the frequencies of vaso-occlusive crises (

Blair 2020). By binding to the P-selectin protein, crizanlizumab blocks its interaction with red blood cells, reducing vaso-occlusions (

Blair 2020) (

Figure 5D). Thus, this therapy operates by simply preventing the red blood cells from interacting with vessel walls for steric occlusion.

Figure 1.

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody anatomy. Pairs of shorter light chains and longer, heavy chains form the ‘Y’ shape of the IgG. The antigen binding fragment (Fab) is composed of light and heavy chains that form variable (VH and VL) and constant (CH and CL) domains. Fabs contain the complementarity determining region (CDR) variable loops primarily responsible for binding and specificity towards the antigen, the antibody binding target. Two Fabs are attached by a flexible hinge region to the crystallizable fragment (FC), the base of the IgG that interacts with other components of the immune system.

Figure 1.

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody anatomy. Pairs of shorter light chains and longer, heavy chains form the ‘Y’ shape of the IgG. The antigen binding fragment (Fab) is composed of light and heavy chains that form variable (VH and VL) and constant (CH and CL) domains. Fabs contain the complementarity determining region (CDR) variable loops primarily responsible for binding and specificity towards the antigen, the antibody binding target. Two Fabs are attached by a flexible hinge region to the crystallizable fragment (FC), the base of the IgG that interacts with other components of the immune system.

Figure 2.

Proteins interact via a cumulation of molecular interactions. These interactions include hydrogen bonding, salt bridges or ionic interactions, hydrophobics, and π-π and π-ion interactions.

Figure 2.

Proteins interact via a cumulation of molecular interactions. These interactions include hydrogen bonding, salt bridges or ionic interactions, hydrophobics, and π-π and π-ion interactions.

Figure 3.

Surface topography features of antibody-antigen recognition. (A) Cavities bind small molecule haptens, (B) grooves bind to peptides, and (C) planar surfaces predominantly bind to larger targets, like protein domains.

Figure 3.

Surface topography features of antibody-antigen recognition. (A) Cavities bind small molecule haptens, (B) grooves bind to peptides, and (C) planar surfaces predominantly bind to larger targets, like protein domains.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of antibody-antigen binding. (A,B) Alternative strategies antibodies use to bind their antigen targets. (A) Antibody pockets can conform to the shape of their antigens, providing more diverse binding specificity. (B) Waters may be included to bridge the antibody-antigen interactions. (C) Antibody binding to its antigen uses a two-stage process. First, the random molecular collisions (kdiffusion) in solution lead to loose, non-specific interactions, known as the encounter complex (C’). Second, the encounter complex rearranges to form a stronger, specific interaction, known as the immune complex (C). These interactions are reversable. The distribution of binding interactions across an antibody’s surface is not uniform. Hotspot regions of amino acid residues are vital for binding. When a hotspot is mutated, binding can decrease significantly. In contrast, mutations in non-hotspot regions may only lead to small changes. Hotspots are enriched for tryptophans, arginines, and tyrosines (Bogan and Thorn 1998), and these amino acids contribute largely through aromatic π-π and polar interactions (Akiba and Tsumoto 2015; Madsen et al. 2024).

Figure 4.

Mechanism of antibody-antigen binding. (A,B) Alternative strategies antibodies use to bind their antigen targets. (A) Antibody pockets can conform to the shape of their antigens, providing more diverse binding specificity. (B) Waters may be included to bridge the antibody-antigen interactions. (C) Antibody binding to its antigen uses a two-stage process. First, the random molecular collisions (kdiffusion) in solution lead to loose, non-specific interactions, known as the encounter complex (C’). Second, the encounter complex rearranges to form a stronger, specific interaction, known as the immune complex (C). These interactions are reversable. The distribution of binding interactions across an antibody’s surface is not uniform. Hotspot regions of amino acid residues are vital for binding. When a hotspot is mutated, binding can decrease significantly. In contrast, mutations in non-hotspot regions may only lead to small changes. Hotspots are enriched for tryptophans, arginines, and tyrosines (Bogan and Thorn 1998), and these amino acids contribute largely through aromatic π-π and polar interactions (Akiba and Tsumoto 2015; Madsen et al. 2024).

Figure 5.

Examples of human IgG antibody therapies. (A) In non-hemophiliacs, activated FVIII (FVIIIa) acts as an enzyme cofactor that brings together factors FX and FIXa to initiate the blood coagulation cascade. In hemophiliacs, FVIII levels are significantly decreased, if not absent, from the blood stream, preventing blood clotting when needed. Emicizumab is an antibody with two distinct Fabs. This allows the antibody to bind to both FX and FIXa, emulating the bridging function of FVIIIa. (B) CD40 Ligand binds to the CD40 receptor to activate the immune system. Bleselumab binds the CD40 receptor and blocks CD40 Ligand interactions, preventing an immune response and decreasing the risk of transplant rejection. (C) Tumor cells can express PD-L1 and MHC II that triggers PD-1 and LAG-3 receptors, respectively, to decrease T-cell responses and tumor cell recognition. Nivolumab and relatlimab block these signaling pathways to synergistically aid the body’s immune response towards the cancer. (D) In sickle cell disease, malformed red blood cells aggregate in blood vessels. Crizanmulab blocks the receptor interacting with red blood cells, reducing the likelihood of aggregation and vaso-occlusion.

Figure 5.

Examples of human IgG antibody therapies. (A) In non-hemophiliacs, activated FVIII (FVIIIa) acts as an enzyme cofactor that brings together factors FX and FIXa to initiate the blood coagulation cascade. In hemophiliacs, FVIII levels are significantly decreased, if not absent, from the blood stream, preventing blood clotting when needed. Emicizumab is an antibody with two distinct Fabs. This allows the antibody to bind to both FX and FIXa, emulating the bridging function of FVIIIa. (B) CD40 Ligand binds to the CD40 receptor to activate the immune system. Bleselumab binds the CD40 receptor and blocks CD40 Ligand interactions, preventing an immune response and decreasing the risk of transplant rejection. (C) Tumor cells can express PD-L1 and MHC II that triggers PD-1 and LAG-3 receptors, respectively, to decrease T-cell responses and tumor cell recognition. Nivolumab and relatlimab block these signaling pathways to synergistically aid the body’s immune response towards the cancer. (D) In sickle cell disease, malformed red blood cells aggregate in blood vessels. Crizanmulab blocks the receptor interacting with red blood cells, reducing the likelihood of aggregation and vaso-occlusion.