Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Apparatus

2.2. Sensor Chips Preparation

2.3. Patients and Samples

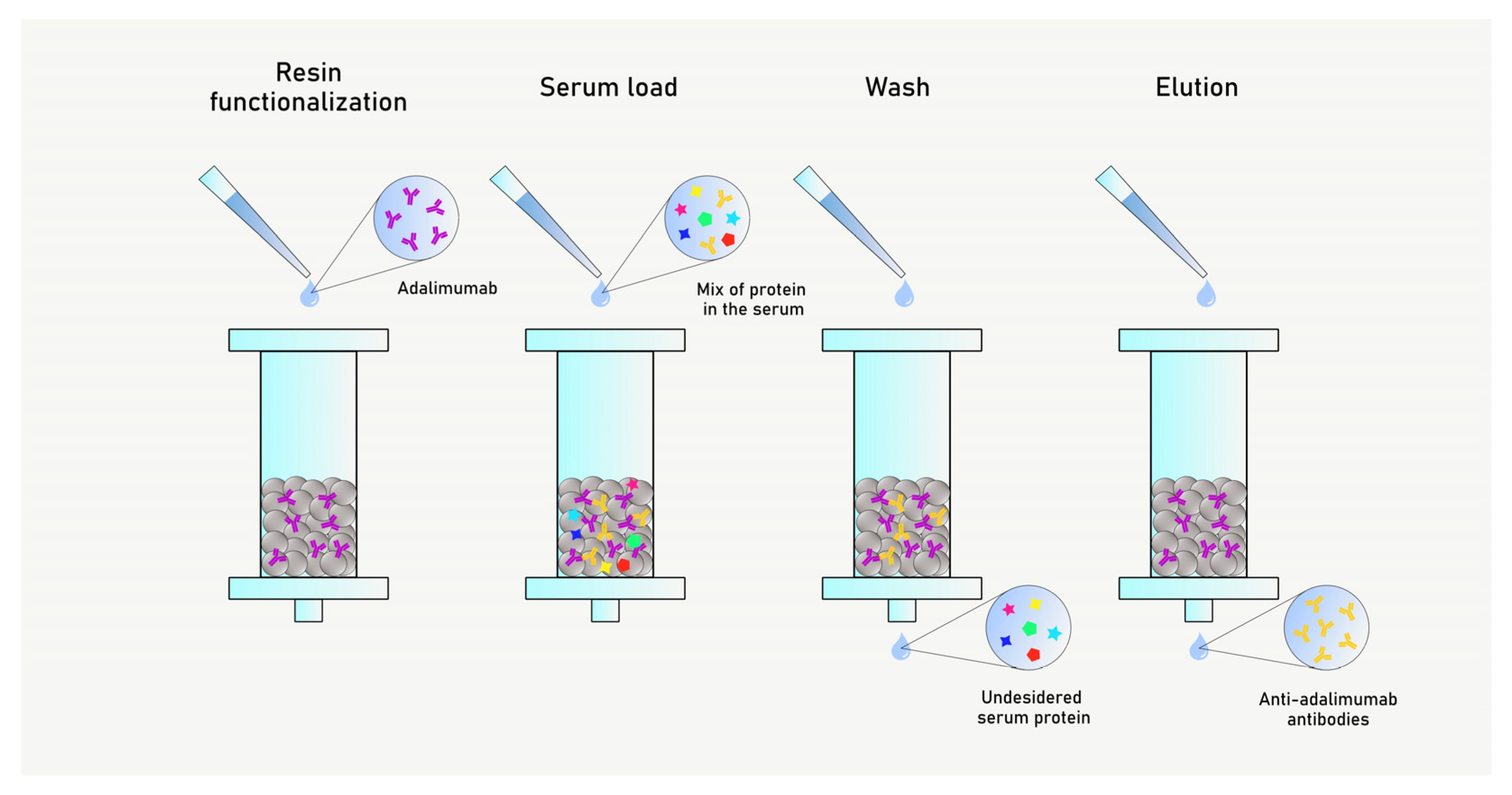

2.4. Anti-Drug Antibodies (AAA) Purification

2.5. Kinetic Experiments

3. Results

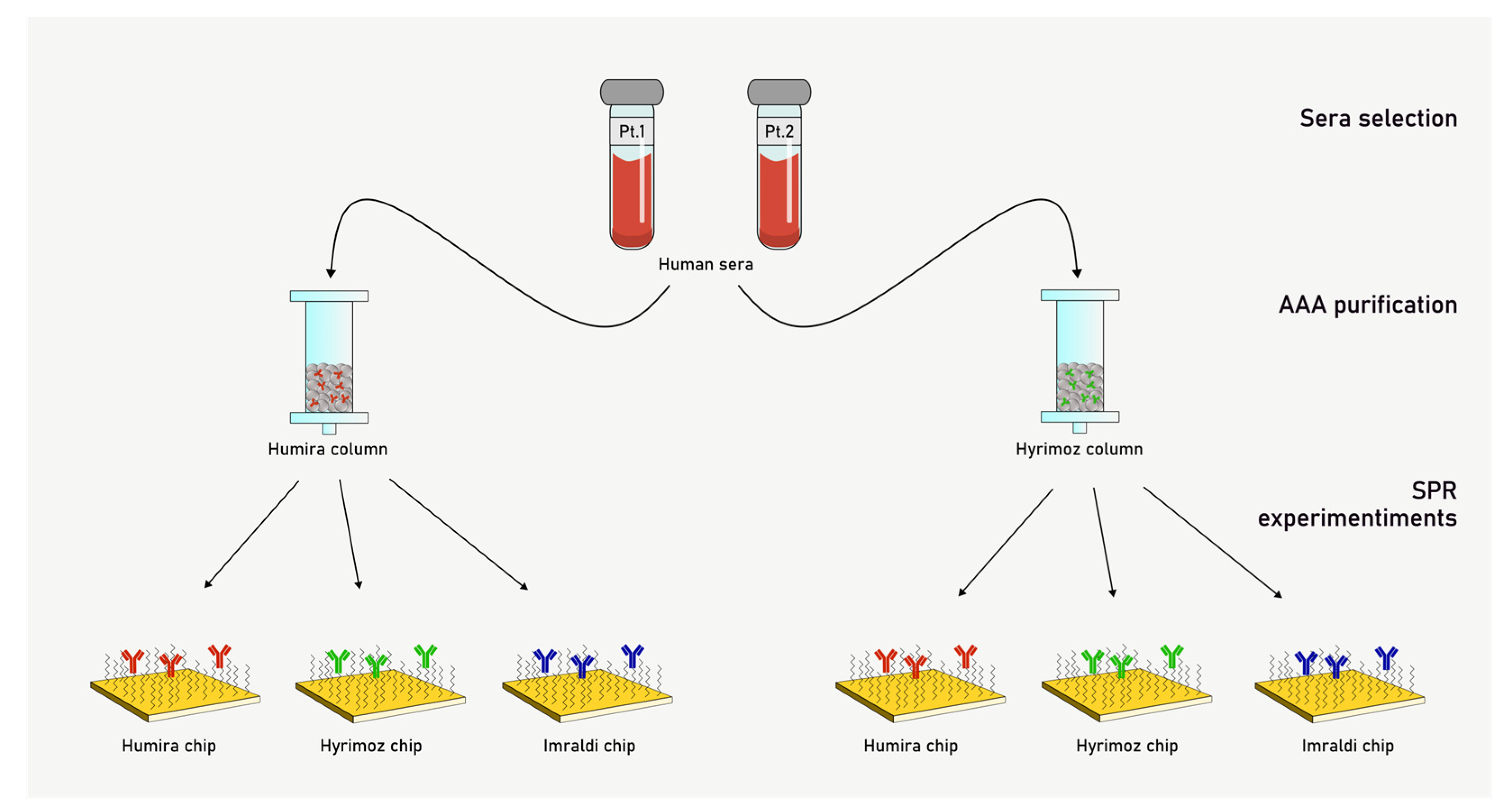

3.1. Serum Samples Selection

3.2. Anti-Adalimumab Antibodies Purification

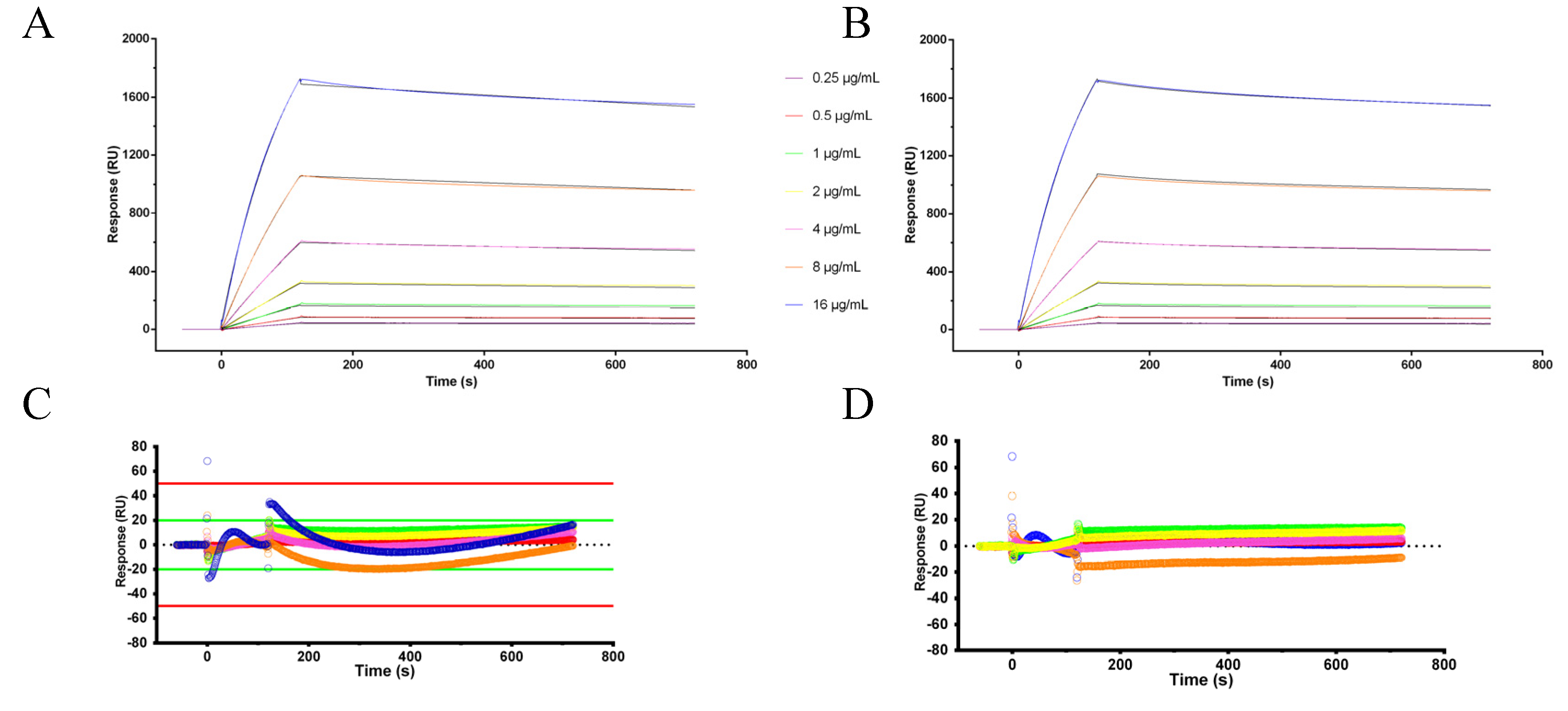

3.3. Surface Plasmon Resonance Experiments

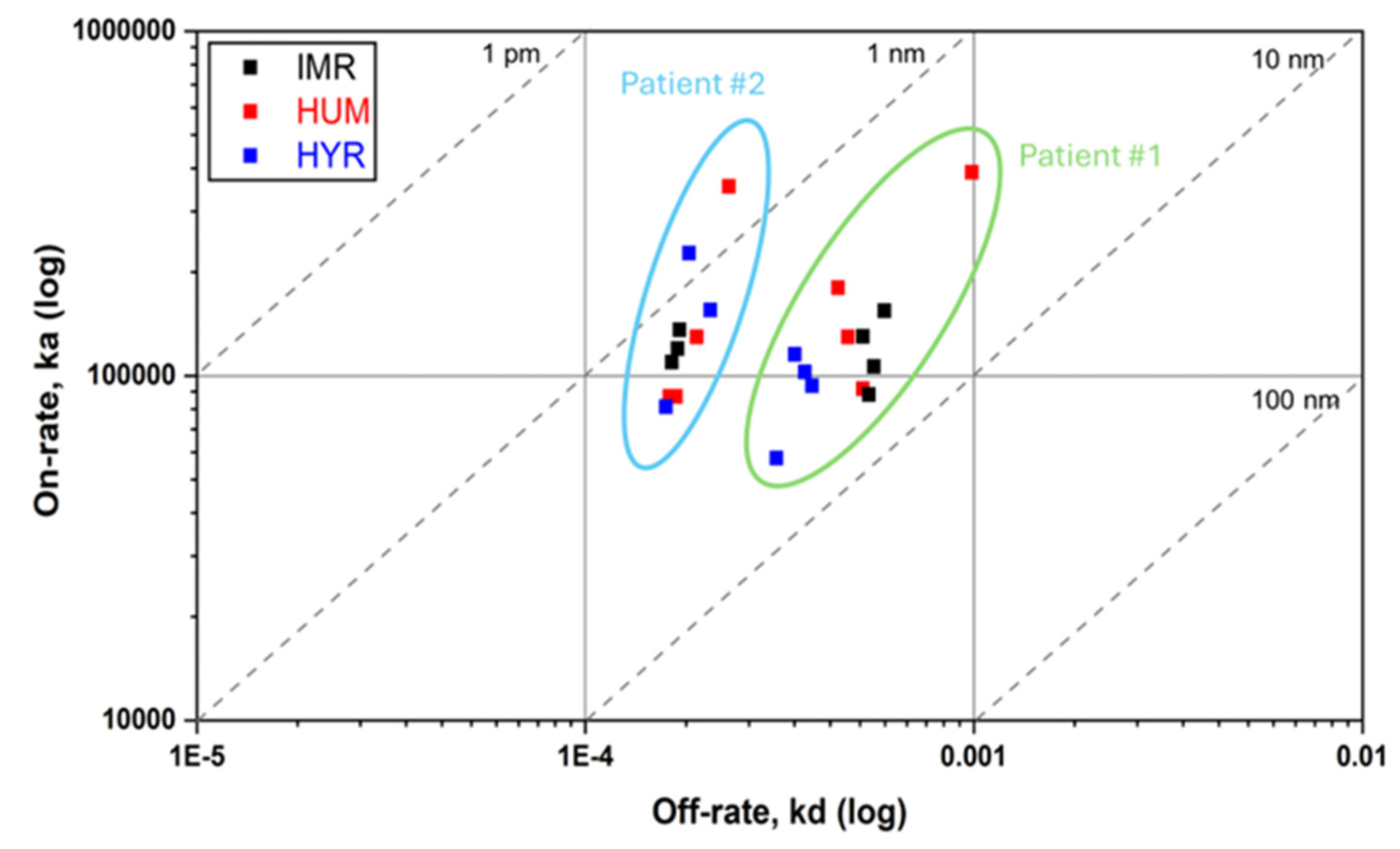

3.4. Kinetic Summary

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| ADL | adalimumab |

| AAA | Anti-adalimumab antibodies |

| SPR | Surface plasmon resonance |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| JIA | Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis |

| NHS | N-hydroxysuccinimide |

| EDC | 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide |

| RU | Resonance Units |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

References

- Coghlan, J.; He, H.; Schwendeman, A.S. Overview of Humira® Biosimilars: Current European Landscape and Future Implications. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2021, 110, 1572–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbon, J.B.; Laber, M.; Bennett, C.L. Humira: The First $20 Billion Drug. Am J Manag Care 2023, 29, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GaBI Journal Editor Patent Expiry Dates for Biologicals: 2018 Update. GaBI J 2019, 8, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Biosimilar Medicines: Overview | European Medicines Agency (EMA) Available online:. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Kirchhoff, C.F.; Wang, X.M.; Conlon, H.D.; Anderson, S.; Ryan, A.M.; Bose, A. Biosimilars: Key Regulatory Considerations and Similarity Assessment Tools. Biotech & Bioengineering 2017, 114, 2696–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinvia, S.; Cummings, J.R.F.; Ardern-Jones, M.R.; Edwards, C.J. Adalimumab Biosimilars in Europe: An Overview of the Clinical Evidence. BioDrugs 2019, 33, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biosimilars in the EU - Information Guide for Healthcare Professionals.

- Biosimilars Approved in Europe. Available online: https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/biosimilars-approved-in-europe (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Abitbol, V.; Benkhalifa, S.; Habauzit, C.; Marotte, H. Navigating Adalimumab Biosimilars: An Expert Opinion. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2023, 12, e230117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivo, R.; Castellani, C.; Mancuso, S.; Sciarra, G.; Giardina, F.; Bevignani, G.; Ceccarelli, F.; Spinelli, F.R.; Alessandri, C.; Di Franco, M.; et al. Effectiveness of Non-Medical Switch from Adalimumab Bio-Originator to SB5 Biosimilar and from ABP501 Adalimumab Biosimilar to SB5 Biosimilar in Patients with Chronic Inflammatory Arthropathies: A Monocentric Observational Study. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, B.; Plevris, N.; Constantine-Cooke, N.; Lyons, M.; O’Hare, C.; Noble, C.; Arnott, I.D.; Jones, G.-R.; Lees, C.W.; Derikx, L.A.A.P. Multiple Infliximab Biosimilar Switches Appear to Be Safe and Effective in a Real-World Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort. United European Gastroenterol J 2023, 11, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázár-Molnár, E.; Delgado, J.C. Implications of Monoclonal Antibody Therapeutics Use for Clinical Laboratory Testing. Clinical Chemistry 2019, 65, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schie, K.A.; Hart, M.H.; De Groot, E.R.; Kruithof, S.; Aarden, L.A.; Wolbink, G.J.; Rispens, T. The Antibody Response against Human and Chimeric Anti-TNF Therapeutic Antibodies Primarily Targets the TNF Binding Region. Ann Rheum Dis 2015, 74, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schouwenburg, P.A.; van de Stadt, L.A.; de Jong, R.N.; van Buren, E.E.L.; Kruithof, S.; de Groot, E.; Hart, M.; van Ham, S.M.; Rispens, T.; Aarden, L.; et al. Adalimumab Elicits a Restricted Anti-Idiotypic Antibody Response in Autoimmune Patients Resulting in Functional Neutralisation. Ann Rheum Dis 2013, 72, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartelds, G.M. Development of Antidrug Antibodies Against Adalimumab and Association With Disease Activity and Treatment Failure During Long-Term Follow-Up. JAMA 2011, 305, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, F.B.; Morand, E.F.; Murphy, K.; Mackay, F.; Mariette, X.; Marcelli, C. Antidrug Antibodies (ADAb) to Tumour Necrosis Factor (TNF)-Specific Neutralising Agents in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: A Real Issue, a Clinical Perspective. Ann Rheum Dis 2013, 72, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, M.; Bird, C.; Atkinson, E.; Cludts, I.; Rigsby, P. The First WHO International Standard for Adalimumab: Dual Role in Bioactivity and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 636420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cludts, I.; Spinelli, F.R.; Morello, F.; Hockley, J.; Valesini, G.; Wadhwa, M. Anti-Therapeutic Antibodies and Their Clinical Impact in Patients Treated with the TNF Antagonist Adalimumab. Cytokine 2017, 96, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real-Fernández, F.; Cimaz, R.; Rossi, G.; Simonini, G.; Giani, T.; Pagnini, I.; Papini, A.M.; Rovero, P. Surface Plasmon Resonance-Based Methodology for Anti-Adalimumab Antibody Identification and Kinetic Characterization. Anal Bioanal Chem 2015, 407, 7477–7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, A.; Accinno, M.; Errante, F.; Capone, M.; Vultaggio, A.; Simoncini, E.; Zipoli, G.; Cosmi, L.; Annunziato, F.; Rovero, P.; et al. Quantitative Evaluation of Adalimumab and Anti-Adalimumab Antibodies in Sera Using a Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor. Clinical Biochemistry 2024, 133–134, 110838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, T.W.J.; Torii, Y.; Muniz, R. Adalimumab Biosimilars in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of the Evidence for Biosimilarity. Rheumatol Ther 2021, 8, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Niewiarowski, A.; Arai, Y.; Nomura, H.; Baird, M.; Dalrymple, I.; Warrington, S.; Boyce, M. Pharmacokinetics, Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of FKB327, a New Biosimilar Medicine of Adalimumab/Humira, in Healthy Subjects. Brit J Clinical Pharma 2017, 83, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real-Fernández, F.; Pregnolato, F.; Cimaz, R.; Papini, A.M.; Borghi, M.O.; Meroni, P.L.; Rovero, P. Detection of Anti-Adalimumab Antibodies in a RA Responsive Cohort of Patients Using Three Different Techniques. Analytical Biochemistry 2019, 566, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, V.; McCabe, D.; Bender, S. Immunogenicity of Adalimumab Reference Product and Adalimumab-Adbm in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis, Crohn’s Disease and Chronic Plaque Psoriasis: A Pooled Analysis of the VOLTAIRE Trials. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e081687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alten, R.; Markland, C.; Boyce, M.; Kawakami, K.; Muniz, R.; Genovese, M.C. Immunogenicity of an Adalimumab Biosimilar, FKB327, and Its Reference Product in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int J of Rheum Dis 2020, 23, 1514–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, M.C.; Kellner, H.; Arai, Y.; Muniz, R.; Alten, R. Long-Term Safety, Immunogenicity and Efficacy Comparing FKB327 with the Adalimumab Reference Product in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: Data from Randomised Double-Blind and Open-Label Extension Studies. RMD Open 2020, 6, e000987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.-H.; Hsu, J.-L.; Huang, H.-Y.; Huang, J.-L.; Yeh, K.-W.; Chen, L.-C.; Lee, W.-I.; Yao, T.-C.; Ou, L.-S.; Lin, S.-J.; et al. Early Anti-Drug Antibodies Predict Adalimumab Response in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. IJMS 2025, 26, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, S.T.; Aalto, K.; Kotaniemi, K.M.; Kivelä, T.T. Anti-Adalimumab Antibodies in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Related Uveitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017, 35, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar]

| Patient #1 | Patient #2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 17 years | 10 years |

| JIA subtype | RF-negative polyarticular JIA | Oligoarticular JIA |

| Disease duration | 10 years | 8 years |

| Previous exposure to ADL (duration) | Yes (56 months) |

Yes(22 months) |

| Type of ADA | Biosimilar (Imraldi®) | Biosimilar (Hyrimoz®) |

| Disease remission | Yes | Yes |

| Concomitant MTX (dose) | No | Yes (oral MTX 7.5 mg/week, equivalent to 5 mg/m2/week) |

| Adverse events at the last available follow-up |

No |

No |

| Sample | Humira® column | Hyrimoz® column |

|---|---|---|

| Patient #1 | 37.9 µg/mL | 128 µg/mL |

| Patient #2 | 32.9 µg/mL | 33.6 µg/mL |

| Humira® column | Hyrimoz® column | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient #1 | Humira® chip | Hyrimoz® chip | Imraldi® chip | Humira® chip | Hyrimoz® chip | Imraldi® chip |

| Binding 1:1 | 3.13±0.60 (19.0%) | 3.32±0.23 (6.8%) | 3.91±0.13 (3.2%) | 4.14±1.54 (37.2%) | 4.64±0.44 (9.5%) | 6.16±0.76 (12.3%) |

| Two state reaction | 2.63±0.19 (7.2%) | 1.59±0.17 (10.7%) | 2.45±0.21 (8.4%) | 2.6±0.61 (23.5%) | 2.61±0.40 (15.3%) | 4.03±0.45 (11.2%) |

| Patient #2 | Humira® chip | Hyrimoz® chip | Imraldi® chip | Humira® chip | Hyrimoz® chip | Imraldi® chip |

| Binding 1:1 | 1.13±0.40 (35.6%) | 1.10±0.28 (25.9%) | 1.41±0.08 (5.7%) | 2.01±0.20 (9.7%) | 2.67±0.67 (25.1%) | 1.73±0.15 (8.4%) |

| Two state reaction | 0.545±0.067 (12.2%) | 0.655±0.241 (36.8%) | 0.567±0.142 (25.0%) | 0.902±0.398 (44.1%) | 1.79±0.44 (24.9%) | 0.402±0.049 (12.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).