Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

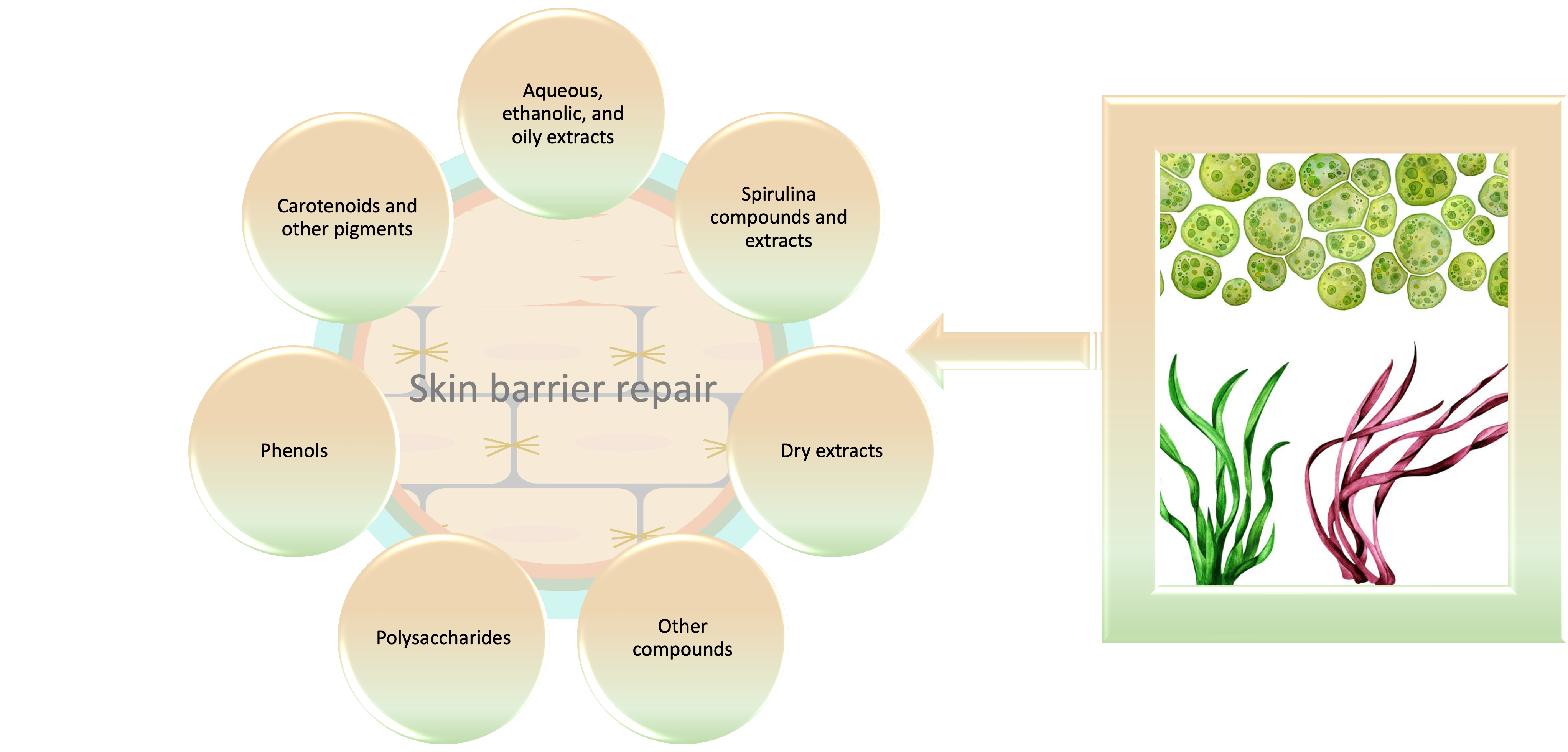

Polysaccharides

Carotenoids and Other Pigments

Phenols

Other Compounds

Aquaous, Ethanolics and Oily Extracts

Spirulina Compounds and Aqueous Extracts

Dry Extracts

Potential of Other Algae Compounds in Skin Barrier Recovery

Cosmetic Patents Based on the Use of Algae and Spiruline for Skin Barrier Improvement

3. Future Challenges and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harris-Tryon TA, Grice EA. Microbiota and maintenance of skin barrier function. Science. 2022;376(6596):940-945. [CrossRef]

- Egawa G, Kabashima K. Barrier dysfunction in the skin allergy. Allergology International. 2018;67(1):3-11. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Guo J, Tang P, et al. Insights from Traditional Chinese Medicine for Restoring Skin Barrier Functions. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17(9):1176. [CrossRef]

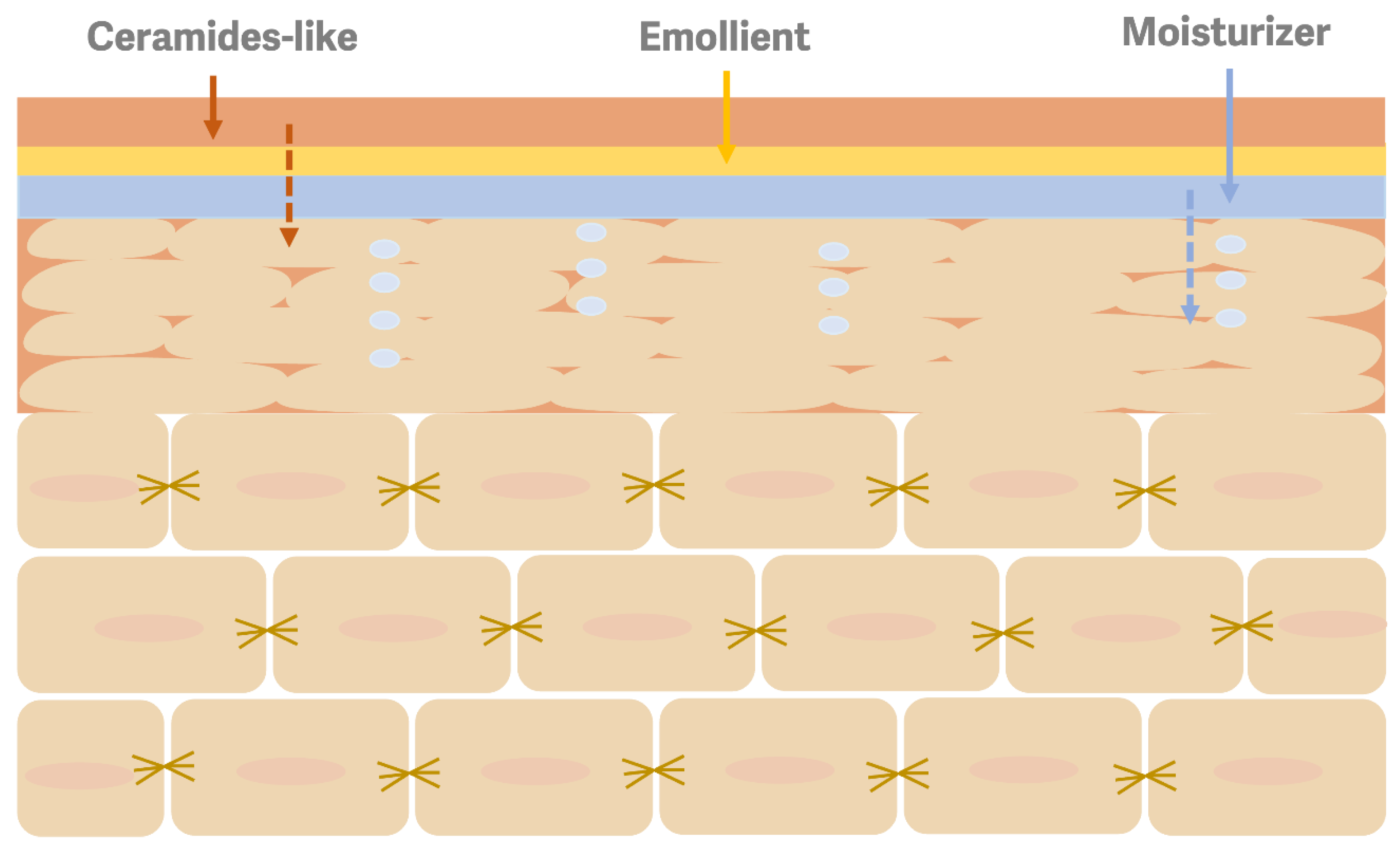

- Schild J, Kalvodová A, Zbytovská J, Farwick M, Pyko C. The role of ceramides in skin barrier function and the importance of their correct formulation for skincare applications. Intern J of Cosmetic Sci. 2024;46(4):526-543. [CrossRef]

- Yosipovitch G, Misery L, Proksch E, Metz M, Ständer S, Schmelz M. Skin Barrier Damage and Itch: Review of Mechanisms, Topical Management and Future Directions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(13):1201-1209. [CrossRef]

- Kucuksezer UC, Ozdemir C, Yazici D, et al. The epithelial barrier theory: development and exacerbation of allergic and other chronic inflammatory diseases. Asia Pacific Allergy. Published online March 31, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Orioli D, Dellambra E. Epigenetic Regulation of Skin Cells in Natural Aging and Premature Aging Diseases. Cells. 2018;7(12):268. [CrossRef]

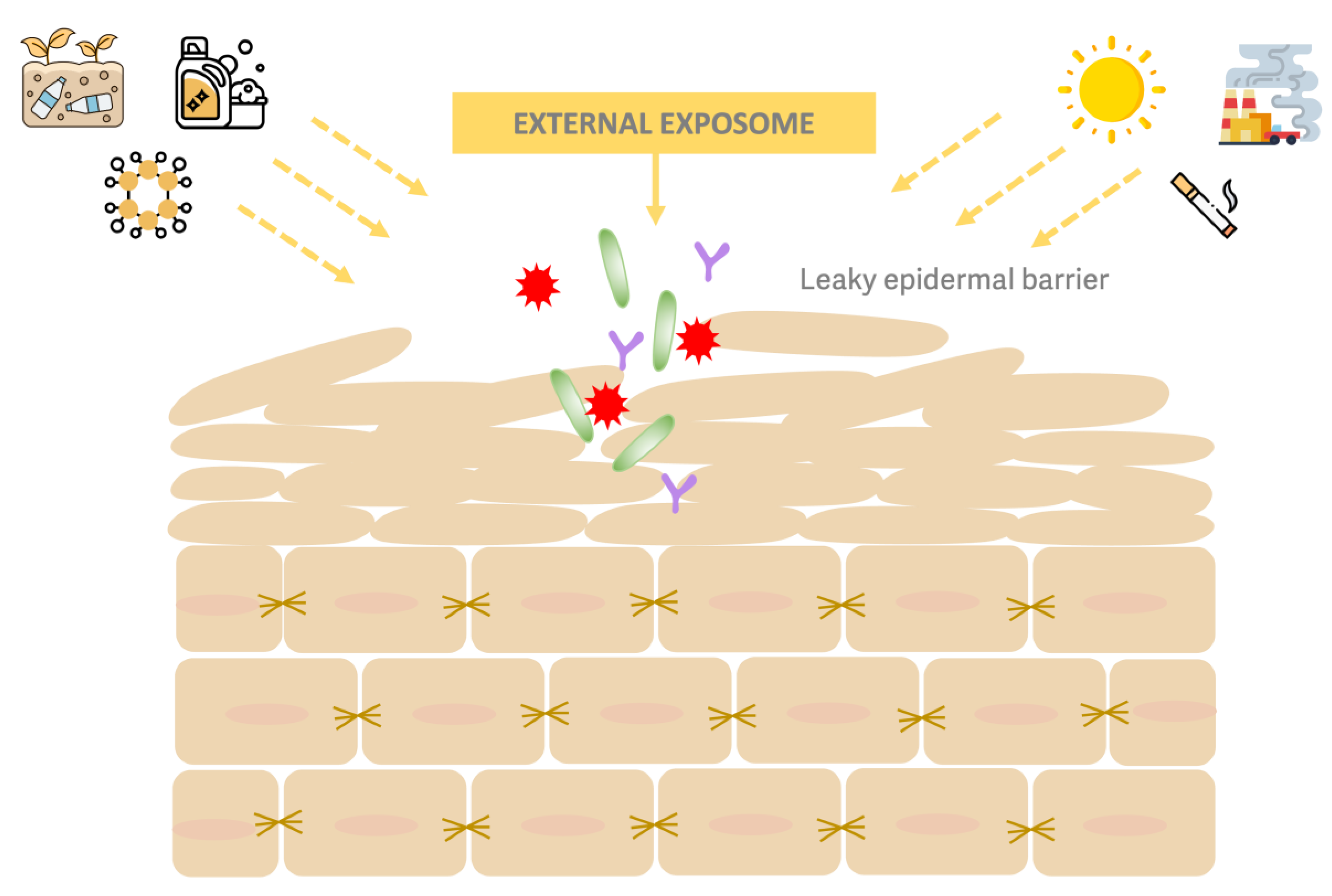

- Celebi Sozener Z, Ozdel Ozturk B, Cerci P, et al. Epithelial barrier hypothesis: Effect of the external exposome on the microbiome and epithelial barriers in allergic disease. Allergy. 2022;77(5):1418-1449. [CrossRef]

- Strugar TL, Bs AK, Seité S, Lin M, Lio P. Connecting the Dots: From Skin Barrier Dysfunction to Allergic Sensitization, and the Role of Moisturizers in Repairing the Skin Barrier. 2019;18(6).

- Wickett RR, Visscher MO. Structure and function of the epidermal barrier. American Journal of Infection Control. 2006;34(10):S98-S110. [CrossRef]

- Baroni A, Buommino E, De Gregorio V, Ruocco E, Ruocco V, Wolf R. Structure and function of the epidermis related to barrier properties. Clinics in Dermatology. 2012;30(3):257-262. [CrossRef]

- Elias PM, Wakefield JS, Man MQ. Moisturizers versus Current and Next-Generation Barrier Repair Therapy for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;32(1):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar J, Chandan N, Lio P, Shi V. The Skin Barrier and Moisturization: Function, Disruption, and Mechanisms of Repair. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2023;36(4):174-185. [CrossRef]

- Madnani N, Deo J, Dalal K, et al. Revitalizing the skin: Exploring the role of barrier repair moisturizers. J of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2024;23(5):1533-1540. [CrossRef]

- Mourelle ML, Gómez CP, Legido JL. Role of Algal Derived Compounds in Pharmaceuticals and Cosmetics. In: Rajauria G, Yuan YV, eds. Recent Advances in Micro and Macroalgal Processing. 1st ed. Wiley; 2021:537-603. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca S, Amaral MN, Reis CP, Custódio L. Marine Natural Products as Innovative Cosmetic Ingredients. Marine Drugs. 2023;21(3):170. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. Pereira L. Seaweeds as Source of Bioactive Substances and Skin Care Therapy—Cosmeceuticals, Algotheraphy, and Thalassotherapy. Cosmetics. 2018;5(4):68. [CrossRef]

- Saide A, Martínez KA, Ianora A, Lauritano C. Unlocking the Health Potential of Microalgae as Sustainable Sources of Bioactive Compounds. IJMS. 2021;22(9):4383. [CrossRef]

- Cagney MH, O’Neill EC. Strategies for producing high value small molecules in microalgae. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2024;214:108942. [CrossRef]

- Conde T, Lopes D, Łuczaj W, et al. Algal Lipids as Modulators of Skin Disease: A Critical Review. Metabolites. 2022;12(2):96. [CrossRef]

- Fernando IPS, Dias MKHM, Madusanka DMD, et al. Fucoidan refined by Sargassum confusum indicate protective effects suppressing photo-oxidative stress and skin barrier perturbation in UVB-induced human keratinocytes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;164:149-161. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Li X, Gan X, et al. Fucoidan from Undaria pinnatifida Ameliorates Epidermal Barrier Disruption via Keratinocyte Differentiation and CaSR Level Regulation. Marine Drugs. 2019;17(12):660. [CrossRef]

- Fernando IPS, Dias MKHM, Madusanka DMD, et al. Low molecular weight fucoidan fraction ameliorates inflammation and deterioration of skin barrier in fine-dust stimulated keratinocytes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021;168:620-630. [CrossRef]

- Kirindage KGIS, Jayasinghe AMK, Cho N, et al. Fine-Dust-Induced Skin Inflammation: Low-Molecular-Weight Fucoidan Protects Keratinocytes and Underlying Fibroblasts in an Integrated Culture Model. Marine Drugs. 2022;21(1):12. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Huang C, Yang F, et al. Fucoidan isolated from the edible seaweed Sargassum fusiforme suppresses skin damage stimulated by airborne particulate matter. Algal Research. 2024;77:103339. [CrossRef]

- Kang J, Hyun SH, Kim H, et al. The effects of fucoidan-rich polysaccharides extracted from Sargassum horneri on enhancing collagen-related skin barrier function as a potential cosmetic product. J of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2024;23(4):1365-1373. [CrossRef]

- Ye Y, Ji D, You L, Zhou L, Zhao Z, Brennan C. Structural properties and protective effect of Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharides against ultraviolet B radiation in hairless Kun Ming mice. Journal of Functional Foods. 2018;43:8-16. [CrossRef]

- Masaki H, Doi M. Function of Sacran as an Artificial Skin Barrier and the Development of Skincare Products. YAKUGAKU ZASSHI. 2019;139(3):371-379. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Xu J, Liu Y, et al. Antioxidant and moisture-retention activities of the polysaccharide from Nostoc commune. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2011;83(4):1821-1827. [CrossRef]

- Matsui M, Tanaka K, Higashiguchi N, et al. Protective and therapeutic effects of fucoxanthin against sunburn caused by UV irradiation. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2016;132(1):55-64. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz S, Frank E, Gierhart D, Simpson P, Frumento R. Zeaxanthin-based dietary supplement and topical serum improve hydration and reduce wrinkle count in female subjects. J of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2016;15(4). [CrossRef]

- Kim M, Oh G, Kim M, Hwang J. Fucosterol Inhibits Matrix Metalloproteinase Expression and Promotes Type-1 Procollagen Production in UVB -induced HaCaT Cells. Photochem & Photobiology. 2013;89(4):911-918. [CrossRef]

- Fernando IPS, Jayawardena TU, Kim HS, et al. A keratinocyte and integrated fibroblast culture model for studying particulate matter-induced skin lesions and therapeutic intervention of fucosterol. Life Sciences. 2019;233:116714. [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe AMK, Han EJ, Kirindage KGIS, et al. 3-Bromo-4,5-dihydroxybenzaldehyde Isolated from Polysiphonia morrowii Suppresses TNF-α/IFN-γ-Stimulated Inflammation and Deterioration of Skin Barrier in HaCaT Keratinocytes. Marine Drugs. 2022;20(9):563. [CrossRef]

- Janssens-Böcker C, Wiesweg K, Doberenz C. The Tolerability and Effectiveness of Marine-Based Ingredients in Cosmetics: A Split-Face Clinical Study of a Serum Spray Containing Fucus vesiculosus Extract, Ulva lactuca Extract, and Ectoin. Cosmetics. 2023;10(3):93. [CrossRef]

- Choi JS, Moon WS, Choi JN, et al. Effects of seaweed Laminaria japonica extracts on skin moisturizing activity in vivo. JOURNAL OF COSMETIC SCIENCE. 2013;64:193-205.

- Li Z yi, Yu CH, Lin YT, et al. The Potential Application of Spring Sargassum glaucescens Extracts in the Moisture-Retention of Keratinocytes and Dermal Fibroblast Regeneration after UVA-Irradiation. Cosmetics. 2019;6(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Jang A yeong, Choi J, Rod-in W, Choi KY, Lee DH, Park WJ. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory and Skin Protective Effects of Codium fragile Extract on Macrophages and Human Keratinocytes in Atopic Dermatitis. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2024;34(4):940-948. [CrossRef]

- Dias MKHM, Madusanka DMD, Han EJ, et al. Sargassum horneri (Turner) C. Agardh ethanol extract attenuates fine dust-induced inflammatory responses and impaired skin barrier functions in HaCaT keratinocytes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2021;273:114003. [CrossRef]

- Mihindukulasooriya SP, Dinh DTT, Herath KHINM, et al. Sargassum horneri extract containing polyphenol alleviates DNCB-induced atopic dermatitis in NC/Nga mice through restoring skin barrier function. Histol Histopathol. 2022;37(09):839-852. [CrossRef]

- Grether-Beck S, Marini A, Jaenicke T, et al. Blue Lagoon Algae Improve Uneven Skin Pigmentation: Results from in vitro Studies and from a Monocentric, Randomized, Double-Blind, Vehicle-Controlled, Split-Face Study. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2022;35(2):77-86. [CrossRef]

- Buono S, Langellotti AL, Martello A, et al. Biological activities of dermatological interest by the water extract of the microalga Botryococcus braunii. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304(9):755-764. [CrossRef]

- Morocho-Jácome AL, Santos BBD, Carvalho JCMD, et al. Microalgae as a Sustainable, Natural-Oriented and Vegan Dermocosmetic Bioactive Ingredient: The Case of Neochloris oleoabundans. Cosmetics. 2022;9(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Lim Y, Park SH, Kim EJ, et al. Polar microalgae extracts protect human HaCaT keratinocytes from damaging stimuli and ameliorate psoriatic skin inflammation in mice. Biol Res. 2023;56(1):40. [CrossRef]

- Kim SY, Kwon YM, Kim KW, Kim JYH. Exploring the Potential of Nannochloropsis sp. Extract for Cosmeceutical Applications. Marine Drugs. 2021;19(12):690. [CrossRef]

- Kok JML, Dowd GC, Cabral JD, Wise LM. Macrocystis pyrifera Lipids Reduce Cytokine-Induced Pro-Inflammatory Signalling and Barrier Dysfunction in Human Keratinocyte Models. IJMS. 2023;24(22):16383. [CrossRef]

- Fabrowska J, KAPUåCI A, Feliksik-Skrobich K, Nowak I. IN VIVO STUDIES AND STABILITY STUDY OF CLADOPHORA GLOMERATA EXTRACT AS A COSMETIC ACTIVE INGREDIENT. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica. 2017;74:633-641.

- Ko SH, Lim Y, Kim EJ, et al. Antarctic Marine Algae Extracts as a Potential Natural Resource to Protect Epithelial Barrier Integrity. Marine Drugs. 2022;20(9):562. [CrossRef]

- Bulteau AL, Moreau M, Saunois A, Nizard C, Friguet B. Algae Extract-Mediated Stimulation and Protection of Proteasome Activity Within Human Keratinocytes Exposed to UVA and UVB Irradiation. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2006;8(1-2):136-143. [CrossRef]

- Vitale M, Truchuelo MT, Nobile V, Gómez-Sánchez MJ. Clinical Tolerability and Efficacy Establishment of a New Cosmetic Treatment Regimen Intended for Sensitive Skin. Applied Sciences. 2024;14(14):6252. [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj W, Gęgotek A, Conde T, Domingues MR, Domingues P, Skrzydlewska E. Lipidomic assessment of the impact of Nannochloropsis oceanica microalga lipid extract on human skin keratinocytes exposed to chronic UVB radiation. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):22302. [CrossRef]

- Birjandi Nejad H, Blasco L, Moran B, et al. Bio-based Algae Oil: an oxidation and structural analysis. Intern J of Cosmetic Sci. 2020;42(3):237-247. [CrossRef]

- Jang YA, Kim BA. Protective Effect of Spirulina-Derived C-Phycocyanin against Ultraviolet B-Induced Damage in HaCaT Cells. Medicina. 2021;57(3):273. [CrossRef]

- Delsin DS, Mercurio, S.G., Fossa MM, Maia Campos, P.M.B.G M. Clinical Efficacy of Dermocosmetic Formulations Containing Spirulina Extract on Young and Mature Skin: Effects on the Skin Hydrolipidic Barrier and Structural Properties. Clin Pharmacol Biopharm. 2015;04(04). [CrossRef]

- Mondal KA, Ahmed R. Clinical Profile of Spirulina on Skin Diseases-A Study in Tertiary care Hospital, Bangladesh. Global Academic Journal of Medical Sciences. 2021;3(3):54-62.

- D’Angelo Costa GM, Maia Campos PMBG. Development of Cosmetic Formulations Containing Olive Extract and Spirulina sp.: Stability and Clinical Efficacy Studies. Cosmetics. 2024;11(3):68. [CrossRef]

- Ma’Or Z, Meshulam-Simon, G, Yehuda, S, Gavrieli, J. A. Anti wrinkle and skin moisturizing effect of a mineral-algal-botanical complex. JOURNAL OF COSMETIC SCIENCE. 2000;51(1):27-36.

- Guillerme JB, Couteau C, Coiffard L. Applications for Marine Resources in Cosmetics. Cosmetics. 2017;4(3):35. [CrossRef]

- Kalasariya HS, Yadav VK, Yadav KK, et al. Seaweed-Based Molecules and Their Potential Biological Activities: An Eco-Sustainable Cosmetics. Molecules. 2021;26(17):5313. [CrossRef]

- Leong HJY, Teoh ML, Beardall J, Convey P. Green beauty unveiled: Exploring the potential of microalgae for skin whitening, photoprotection and anti-aging applications in cosmetics. J Appl Phycol. 2024;36(6):3315-3328. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço-Lopes C, Fraga-Corral M, Jimenez-Lopez C, et al. Metabolites from Macroalgae and Its Applications in the Cosmetic Industry: A Circular Economy Approach. Resources. 2020;9(9):101. [CrossRef]

- Bedoux G, Hardouin K, Burlot AS, Bourgougnon N. Bioactive Components from Seaweeds. In: Advances in Botanical Research. Vol 71. Elsevier; 2014:345-378. [CrossRef]

- Ariede MB, Candido TM, Jacome ALM, Velasco MVR, De Carvalho JCM, Baby AR. Cosmetic attributes of algae - A review. Algal Research. 2017;25:483-487. [CrossRef]

- Salehi B, Sharifi-Rad J, Seca AML, et al. Current Trends on Seaweeds: Looking at Chemical Composition, Phytopharmacology, and Cosmetic Applications. Molecules. 2019;24(22):4182. [CrossRef]

- Cikoš AM, Jerković I, Molnar M, Šubarić D, Jokić S. New trends for macroalgal natural products applications. Natural Product Research. 2021;35(7):1180-1191. [CrossRef]

- Dussably J, Mshvildadze V, Pichette A, Ripoll L. Microalgae and Diatom - Potential Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Resources – Review. J Biomed Res Environ Sci. 2022;3(9):1082-1092. [CrossRef]

- Kalasariya HS, Pereira L, Patel NB. Pioneering Role of Marine Macroalgae in Cosmeceuticals. Phycology. 2022;2(1):172-203. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang D, He N, Khoo KS, Ng EP, Chew KW, Ling TC. Application progress of bioactive compounds in microalgae on pharmaceutical and cosmetics. Chemosphere. 2022;291:132932. [CrossRef]

- Yadav A, Kumar S, Deepak B, Bhateria R, Mona S. Prospects of algal bioactive compounds in the cosmetic industry. In: Algae Based Bioelectrochemical Systems for Carbon Sequestration, Carbon Storage, Bioremediation and Bioproduct Generation. Elsevier; 2024:69-76. [CrossRef]

- Joshi S, Kumari R, Upasani VN. Applications of Algae in Cosmetics: An Overview. 2018;7(2).

- Morais T, Cotas J, Pacheco D, Pereira L. Seaweeds Compounds: An Ecosustainable Source of Cosmetic Ingredients? Cosmetics. 2021;8(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Mendes M, Cotas J, Pacheco D, et al. Red Seaweed (Rhodophyta) Phycocolloids: A Road from the Species to the Industry Application. Marine Drugs. 2024;22(10):432. [CrossRef]

- Parikh HS, Singh PK, Tiwari A. Algal biorefinery: focus on cosmeceuticals. Syst Microbiol and Biomanuf. 2024;4(4):1239-1261. [CrossRef]

- Fabrowska J, Łęska B, Schroeder G, Messyasz B, Pikosz M. Biomass and Extracts of Algae as Material for Cosmetics. In: Kim S, Chojnacka K, eds. Marine Algae Extracts. 1st ed. Wiley; 2015:681-706. [CrossRef]

- Silva M, Avni D, Varela J, Barreira L. The Ocean’s Pharmacy: Health Discoveries in Marine Algae. Molecules. 2024;29(8):1900. [CrossRef]

- Kalasariya HS, Dave DrMP, Yadav DrVK, Patel DrNB. BENEFICIAL EFFECTS OF MARINE ALGAE IN SKIN MOISTURIZATION AND PHOTOPROTECTION. IJPHC. Published online 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel F, Alves R, Rodrigues F, P. P. Oliveira M. Macroalgae-Derived Ingredients for Cosmetic Industry—An Update. Cosmetics. 2017;5(1):2. [CrossRef]

- Ersoydan S, Rustemeyer T. Investigating the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Various Brown Algae Species. Marine Drugs. 2024;22(10):457. [CrossRef]

- Freitas R, Martins A, Silva J, et al. Highlighting the Biological Potential of the Brown Seaweed Fucus spiralis for Skin Applications. Antioxidants. 2020;9(7):611. [CrossRef]

- Jing R, Guo K, Zhong Y, et al. Protective effects of fucoidan purified from Undaria pinnatifida against UV-irradiated skin photoaging. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(14):1185-1185. [CrossRef]

- Mayer A, Mayer V, Swanson-Mungerson M, et al. Marine Pharmacology in 2019–2021: Marine Compounds with Antibacterial, Antidiabetic, Antifungal, Anti-Inflammatory, Antiprotozoal, Antituberculosis and Antiviral Activities; Affecting the Immune and Nervous Systems, and Other Miscellaneous Mechanisms of Action. Marine Drugs. 2024;22(7):309. [CrossRef]

- Ryu B, Himaya SWA, Kim SK. Applications of Microalgae-Derived Active Ingredients as Cosmeceuticals. In: Handbook of Marine Microalgae. Elsevier; 2015:309-316. [CrossRef]

- Castro V, Oliveira R, Dias ACP. Microalgae and cyanobacteria as sources of bioactive compounds for cosmetic applications: A systematic review. Algal Research. 2023;76:103287. [CrossRef]

- Messyasz B, Michalak I, Łęska B, et al. Valuable natural products from marine and freshwater macroalgae obtained from supercritical fluid extracts. J Appl Phycol. 2018;30(1):591-603. [CrossRef]

- Gürlek C, Yarkent Ç, Köse A, Oral İ, Öncel SŞ, Elibol M. Evaluation of Several Microalgal Extracts as Bioactive Metabolites as Potential Pharmaceutical Compounds. In: Badnjevic A, Škrbić R, Gurbeta Pokvić L, eds. CMBEBIH 2019. Vol 73. IFMBE Proceedings. Springer International Publishing; 2020:267-272. [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Hyun J, Nagahawatta DP, Kim YM, Heo MS, Jeon YJ. Cosmeceutical Effects of Ishige okamurae Celluclast Extract. Antioxidants. 2022;11(12):2442. [CrossRef]

- Yuan M, Wang J, Geng L, Wu N, Yang Y, Zhang Q. A review: Structure, bioactivity and potential application of algal polysaccharides in skin aging care and therapy. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;272:132846. [CrossRef]

- Ruocco N, Costantini S, Guariniello S, Costantini M. Polysaccharides from the Marine Environment with Pharmacological, Cosmeceutical and Nutraceutical Potential. Molecules. 2016;21(5):551. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Lee JE, Kim KH, Kang NJ. Beneficial Effects of Marine Algae-Derived Carbohydrates for Skin Health. Marine Drugs. 2018;16(11):459. [CrossRef]

- Lomartire S, Gonçalves AMM. Algal Phycocolloids: Bioactivities and Pharmaceutical Applications. Marine Drugs. 2023;21(7):384. [CrossRef]

- Valado A, Cunha M, Pereira L. Biomarkers and Seaweed-Based Nutritional Interventions in Metabolic Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Marine Drugs. 2024;22(12):550. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Man MQ, Li T, Elias PM, Mauro TM. Aging-associated alterations in epidermal function and their clinical significance. Aging. 2020;12(6):5551-5565. [CrossRef]

- Patel NB, Tailor V, Rabadi M, Jain DA, Kalasariya H. Role of marine macroalgae in Skin hydration and photoprotection benefits: A review. International Journal of Botany Studies.

- Fournière M, Bedoux G, Lebonvallet N, et al. Poly- and Oligosaccharide Ulva sp. Fractions from Enzyme-Assisted Extraction Modulate the Metabolism of Extracellular Matrix in Human Skin Fibroblasts: Potential in Anti-Aging Dermo-Cosmetic Applications. Marine Drugs. 2021;19(3):156. [CrossRef]

- Alves A, Sousa RA, Reis RL. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment of Ulvan, a Polysaccharide Extracted from Green Algae. Phytotherapy Research. 2013;27(8):1143-1148. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Jin W, Hou Y, Niu X, Zhang H, Zhang Q. Chemical composition and moisture-absorption/retention ability of polysaccharides extracted from five algae. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2013;57:26-29. [CrossRef]

- Shao P, Shao J, Han L, Lv R, Sun P. Separation, preliminary characterization, and moisture-preserving activity of polysaccharides from Ulva fasciata. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2015;72:924-930. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Chi Z, Yu L, Jiang F, Liu C. Sulfated modification, characterization, and antioxidant and moisture absorption/retention activities of a soluble neutral polysaccharide from Enteromorpha prolifera. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2017;105:1544-1553. [CrossRef]

- Cai CE, Yang YY, Cao RD, Jia R, He PM. Derivatives from Two Algae: Moisture Absorption-Retention Ability, Antioxidative and Uvioresistant Activity. j biobased mat bioenergy. 2018;12(3):277-282. [CrossRef]

- Jesumani V, Du H, Pei P, Aslam M, Huang N. Comparative study on skin protection activity of polyphenol-rich extract and polysaccharide-rich extract from Sargassum vachellianum. Achal V, ed. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0227308. [CrossRef]

- Lee MC, Yeh HY, Shih WL. Extraction Procedure, Characteristics, and Feasibility of Caulerpa microphysa (Chlorophyta) Polysaccharide Extract as a Cosmetic Ingredient. Marine Drugs. 2021;19(9):524. [CrossRef]

- Tian T, Chang H, He K, et al. Fucoidan from seaweed Fucus vesiculosus inhibits 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis. International Immunopharmacology. 2019;75:105823. [CrossRef]

- Lee SE, Lee SH. Skin Barrier and Calcium. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30(3):265. [CrossRef]

- Hänel K, Cornelissen C, Lüscher B, Baron J. Cytokines and the Skin Barrier. IJMS. 2013;14(4):6720-6745. [CrossRef]

- Cheong KL, Qiu HM, Du H, Liu Y, Khan BM. Oligosaccharides Derived from Red Seaweed: Production, Properties, and Potential Health and Cosmetic Applications. Molecules. 2018;23(10):2451. [CrossRef]

- Choi J, Kim S, Kim S. Spirulan from Blue-Green Algae Inhibits Fibrin and Blood Clots: Its Potent Antithrombotic Effects. J Biochem & Molecular Tox. 2015;29(5):240-248. [CrossRef]

- Ngatu NR, Okajima MK, Yokogawa M, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of sacran, a novel polysaccharide from Aphanothece sacrum, on 2,4,6-trinitrochlorobenzene-induced allergic dermatitis in vivo. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2012;108(2):117-122.e2. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki M, Takagi A, Ota S, Kawano S, Sasaki D, Asayama M. Coproduction of lipids and extracellular polysaccharides from the novel green alga Parachlorella sp. BX1.5 depending on cultivation conditions. Biotechnology Reports. 2020;25:e00392. [CrossRef]

- Sathasivam R, Ki JS. A Review of the Biological Activities of Microalgal Carotenoids and Their Potential Use in Healthcare and Cosmetic Industries. Marine Drugs. 2018;16(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Chekanov, K. Chekanov K. Diversity and Distribution of Carotenogenic Algae in Europe: A Review. Marine Drugs. 2023;21(2):108. [CrossRef]

- Jayawardhana HHACK, Jayawardena TU, Sanjeewa KKA, et al. Marine Algal Polyphenols as Skin Protective Agents: Current Status and Future Prospectives. Marine Drugs. 2023;21(5):285. [CrossRef]

- Aging Biomarker Consortium, Bao H, Cao J, et al. Biomarkers of aging. Sci China Life Sci. 2023;66(5):893-1066. [CrossRef]

- Hannan MdA, Sohag AAM, Dash R, et al. Phytosterols of marine algae: Insights into the potential health benefits and molecular pharmacology. Phytomedicine. 2020;69:153201. [CrossRef]

- Hwang E, Park SY, Sun Z wang, Shin HS, Lee DG, Yi TH. The Protective Effects of Fucosterol Against Skin Damage in UVB-Irradiated Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Mar Biotechnol. 2014;16(3):361-370. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira MS, Resende DISP, Lobo JMS, Sousa E, Almeida IF. Marine Ingredients for Sensitive Skin: Market Overview. Marine Drugs. 2021;19(8):464. [CrossRef]

- Choo WT, Teoh ML, Phang SM, et al. Microalgae as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Natural Product Against Human Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1086. [CrossRef]

- Mago Y, Sharma Y, Thakran Y, Mishra A, Tewari S, Kataria N. Next-Generation Organic Beauty Products Obtained from Algal Secondary Metabolites: A Sustainable Development in Cosmeceutical Industries. Mol Biotechnol. Published online August 21, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ruiz M, Martínez-González CA, Kim DH, et al. Microalgae Bioactive Compounds to Topical Applications Products—A Review. Molecules. 2022;27(11):3512. [CrossRef]

- Couteau C, Coiffard L. Microalgal Application in Cosmetics. In: Microalgae in Health and Disease Prevention. Elsevier; 2018:317-323. [CrossRef]

- Lee MK, Ryu H, Lee JY, et al. Potential Beneficial Effects of Sargassum spp. in Skin Aging. Marine Drugs. 2022;20(8):540. [CrossRef]

- Lim MCX, Loo CT, Wong CY, et al. Prospecting bioactivity in Antarctic algae: A review of extracts, isolated compounds and their effects. Fitoterapia. 2024;176:106025. [CrossRef]

- Nowruzi B, Sarvari G, Blanco S. The cosmetic application of cyanobacterial secondary metabolites. Algal Research. 2020;49:101959. [CrossRef]

- Doria E, Temporiti M, Verri M, Dossena M, Buonocore D. Algae as Alternative Source of Bioactive Compounds for Cosmetics. Published online 2020.

- De Luca M, Pappalardo I, Limongi AR, et al. Lipids from Microalgae for Cosmetic Applications. Cosmetics. 2021;8(2):52. [CrossRef]

- Sousa SC, Freitas AC, Gomes AM, Carvalho AP. Extraction of Nannochloropsis Fatty Acids Using Different Green Technologies: The Current Path. Marine Drugs. 2023;21(6):365. [CrossRef]

- Mosxou D, Letsiou S. Exploring the Protective Effects of Phaeodactylum tricornutum Extract on LPS-Treated Fibroblasts. Cosmetics. 2021;8(3):76. [CrossRef]

- Kalasariya HS, Maya-Ramírez CE, Cotas J, Pereira L. Cosmeceutical Significance of Seaweed: A Focus on Carbohydrates and Peptides in Skin Applications. Phycology. 2024;4(2):276-313. [CrossRef]

- Park C, Kim JH, Choi W, et al. Natural peloids originating from subsea depths of 200 m in the hupo basin, South Korea: physicochemical properties for potential pelotherapy applications. Environ Geochem Health. 2024;46(7):240. [CrossRef]

- Wani HMUD, Chen CW, Huang CY, et al. Development of Bioactive Peptides Derived from Red Algae for Dermal Care Applications: Recent Advances. Sustainability. 2023;15(11):8506. [CrossRef]

- Cunha SA, Coscueta ER, Nova P, Silva JL, Pintado MM. Bioactive Hydrolysates from Chlorella vulgaris: Optimal Process and Bioactive Properties. Molecules. 2022;27(8):2505. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Liu H, Shi M, Jiang M, Li L, Zheng Y. Microbial production of ectoine and hydroxyectoine as high-value chemicals. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20(1):76. [CrossRef]

- Kauth M, Trusova OV. Topical Ectoine Application in Children and Adults to Treat Inflammatory Diseases Associated with an Impaired Skin Barrier: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(2):295-313. [CrossRef]

- Leandro A, Pereira L, Gonçalves AMM. Diverse Applications of Marine Macroalgae. Marine Drugs. 2019;18(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Khan N, Sudhakar K, Mamat R. Eco-friendly nutrient from ocean: Exploring Ulva seaweed potential as a sustainable food source. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 2024;17:101239. [CrossRef]

- Čmiková N, Kowalczewski PŁ, Kmiecik D, et al. Characterization of Selected Microalgae Species as Potential Sources of Nutrients and Antioxidants. Foods. 2024;13(13):2160. [CrossRef]

- Stoyneva-Gärtner M, Uzunov B, Gärtner G. Enigmatic Microalgae from Aeroterrestrial and Extreme Habitats in Cosmetics: The Potential of the Untapped Natural Sources. Cosmetics. 2020;7(2):27. [CrossRef]

- Matias M, Martins A, Alves C, et al. New Insights into the Dermocosmetic Potential of the Red Seaweed Gelidium corneum. Antioxidants. 2023;12(9):1684. [CrossRef]

- Veeraperumal S, Qiu HM, Zeng SS, et al. Polysaccharides from Gracilaria lemaneiformis promote the HaCaT keratinocytes wound healing by polarised and directional cell migration. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2020;241:116310. [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga Do Nascimento-Neto L, Carneiro RF, Da Silva SR, et al. Characterization of Isoforms of the Lectin Isolated from the Red Algae Bryothamnion seaforthii and Its Pro-Healing Effect. Marine Drugs. 2012;10(9):1936-1954. [CrossRef]

- Gunes S, Tamburaci S, Dalay MC, Deliloglu Gurhan I. In vitro evaluation of Spirulina platensis extract incorporated skin cream with its wound healing and antioxidant activities. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2017;55(1):1824-1832. [CrossRef]

- Choi H, Kim B, Jeong SH, et al. Microalgae-Based Biohybrid Microrobot for Accelerated Diabetic Wound Healing. Small. 2023;19(1):2204617. [CrossRef]

- Fernando IPS, Kirindage KGIS, Jeon HN, Han EJ, Jayasinghe AMK, Ahn G. Preparation of microspheres by alginate purified from Sargassum horneri and study of pH-responsive behavior and drug release. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2022;202:681-690. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei H, Sedighi S, Kouchaki E, et al. Probiotics and the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: An Update. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2022;42(8):2449-2457. [CrossRef]

- Morganti P, Palombo M, Fabrizi G, et al. New Insights on Anti-Aging Activity of Chitin Nanofibril-Hyaluronan Block Copolymers Entrapping Active Ingredients: In Vitro and In Vivo Study.

- Hoskin RT, Grace MH, Guiotto A, Pecorelli A, Valacchi G, Lila MA. Development of Spray Dried Spirulina Protein-Berry Pomace Polyphenol Particles to Attenuate Pollution-Induced Skin Damage: A Convergent Food-Beauty Approach. Antioxidants. 2023;12(7):1431. [CrossRef]

- Tang S, Chen Y, Song G, et al. A Cocktail of Industrial Chemicals in Lipstick and Nail Polish: Profiles and Health Implications. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2021;8(9):760-765. [CrossRef]

- Couteau C, Coiffard L. Phycocosmetics and Other Marine Cosmetics, Specific Cosmetics Formulated Using Marine Resources. Marine Drugs. 2020;18(6):322. [CrossRef]

- Hempel MDSS, Colepicolo P, Zambotti-Villela L. Macroalgae Biorefinery for the Cosmetic Industry: Basic Concept, Green Technology, and Safety Guidelines. Phycology. 2023;3(1):211-241. [CrossRef]

- Hentati F, Tounsi L, Djomdi D, et al. Bioactive Polysaccharides from Seaweeds. Molecules. 2020;25(14):3152. [CrossRef]

- López-Hortas L, Flórez-Fernández N, Torres MD, et al. Applying Seaweed Compounds in Cosmetics, Cosmeceuticals and Nutricosmetics. Marine Drugs. 2021;19(10):552. [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan J, Gadkari S, Martinez-Hernandez E, et al. Novel macroalgae (seaweed) biorefinery systems for integrated chemical, protein, salt, nutrient and mineral extractions and environmental protection by green synthesis and life cycle sustainability assessments. Green Chem. 2019;21(10):2635-2655. [CrossRef]

- Siahaan EA, Agusman, Pangestuti R, Shin KH, Kim SK. Potential Cosmetic Active Ingredients Derived from Marine By-Products. Marine Drugs. 2022;20(12):734. [CrossRef]

- Bose I, Nousheen, Roy S, et al. Unveiling the Potential of Marine Biopolymers: Sources, Classification, and Diverse Food Applications. Materials. 2023;16(13):4840. [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarasaiyar K, Goh BH, Jeon YJ, Yow YY. Algae Metabolites in Cosmeceutical: An Overview of Current Applications and Challenges. Marine Drugs. 2020;18(6):323. [CrossRef]

- Bouafir Y, Bouhenna MM, Nebbak A, et al. Algal bioactive compounds: A review on their characteristics and medicinal properties. Fitoterapia. 2025;183:106591. [CrossRef]

| Bioactive Compound Group / Extract | Specific Bioactive Compound | Macro /Microalgae | Type of Study | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Low molecular fucoidan fraction | Sargassum confusum | In vitro (HaCaT cells) |

Moisture-preserving repair structural proteins in UVB-damaged HaCaT cells | [21] |

| Fucoidan | Undaria pinnatifida | In vivo (ICR mice) |

Promotion of the recovery of epidermal barrier disruption | [22] | |

| Low molecular fucoidan fraction | Sargassum horneri | In vitro (FD-induced HaCaT keratinocytes) |

Amelioration of key tight junction proteins and skin hydration factors Reduction of FD-induced inflammation and skin barrier deterioration |

[23] | |

| Low molecular fucoidan fraction | Sargassumconfusum | In vitro (FD-induced HaCaT keratinocytes) |

Increasing the cell viability in FD-stimulated HaCaT keratinocytes |

[24] | |

| Fucoidan | Sargassum fusiforme | In vitro (HaCaT cells and HDF cells) |

Protective effect against particular matter pollution | [25] | |

| Fucoidan (cream with 1% fucoidan) |

Sargassum horneri | Clinical trial |

Improvement skin barrier function Reduction of TEWL |

[26] | |

| Sulfated polysaccharides + Glucuronic acid | Sargassum fusiforme | In vivo (Hairless Kun Ming mice) |

Decreasing skin moisture loss | [27] | |

| Sacran gel | Aphanothece sacrum | Clinical study | Skin hydration increase TEWL decrease Promotion of normal epidermal differentiation and improvement of the maturation of corneocytes |

[28] | |

| Polysaccharide (specific type NR) | Nostoc commune | In vitro (Mouse stratum corneum) |

Higher water retention than urea | [29] | |

| Carotenoids and other pigments | Fucoxanthin | Undaria pinnatifida | In vitro In vivo |

Regulation of filaggrin genes expression Restoration of the skin barrier by filaggrin stimulation |

[30] |

| Zeaxanthin-based oral supplementation + topical gel serum | Laminaria and Porphyra extracts | Clinical study | Skin hydration improvement | [31] | |

| Phenols | Fucosterol | Sargassum fusiforme | In vitro (HaCaT cells) |

Modulation of MAPK in irradiated HaCaT cells | [32] |

| Fucosterol | Sargassum binderi | In vitro (HaCaT keratinocytes) |

Cytoprotective effects against xenobiotics | [33] | |

| Bromophenol (3-bromo-4,5 – dihydroxybenzaldehyde) |

Polysiphonia morrowii |

In vitro (HaCaT keratinocytes) |

Increasing the production of skin hydration proteins and tight junction proteins | [34] | |

|

Mixture of compounds (Fucus vesiculosus extract, Ulva lactuca extract, and Ectoine) |

Fucoidan, ulvans, and ectoine |

Fucus vesiculosus Ulva lactuca |

Split-Face Clinical Study | Increasing skin hydration Maintenance of the skin barrier function |

[35] |

| Aqueous extracts | NR |

Laminaria japonica (currently Saccharina japonica) |

In vivo | Hydration increase TEWL decrease |

[36] |

| Aqueous extracts | NR |

Sargassum glaucescens |

In vitro (Human Primary Epidermal Keratinocytes, HPEK) |

Induction of the expressions of skin barrier-related genes in HPEK Increasing expression levels of TGM1, KRT10 and FLG Promotion of NMF production |

[37] |

| Aqueous extracts | Guanosine and uridine nucleosides | Codium fragile | In vitro (TNF-α/IFN-γ stimulated HaCaT keratinocytes) |

Expression of factors related to skin barrier function, FLG, IVL, and LOR enhancement | [38] |

| Ethanolic extract | NR | Sargassum horneri | In vitro (FD-induced HaCaT keratinocytes) |

Amelioration of filaggrin, involucrin, and lymphoepithelial Kazal-type-related inhibitor (LEKTI) Regulation of tight junction proteins |

[39] |

| Ethanolic extract | NR | Sargassum horneri | In vivo (DNCB-induced AD) |

Improvement of skin barrier function | [40] |

| Aqueous extracts | NR | Coccoid and filamentous algae | In vivo | Increasing mRNA expression for involucrin, filaggrin and transglutaminase-1 |

[41] |

| Aqueous extract | NR | Botryococcus braunii | In vitro | Induction of gene expression of aquaporin-3, filaggrin and involucrin | [42] |

| Aqueous extract | NR | Neochloris oleoabundans | In vivo | Not skin barrier perturbation Anti-inflammatory activity |

[43] |

| Ethanolic extract | Dominant compounds: Docosahexaenoic acid methyl ester, linolenic acid methyl ester, 13-Docosenamide (Z)-, and methyl 4,7,10,13-hexadecatetraenoate |

Micractinium sp. (KSF0015 and KSF0041) Chlamydomonas sp. (KNM0029C, KSF0037, and KSF0134) Chlorococcum sp. (KSF0003) |

In vivo (C57BL/6 mice) |

Reduction of barrier integrity damage | [44] |

| Ethanolic extract | Main compounds: fatty acids 58.2%, carotenoids 1.6%, phenolics 7.7%, flavonoids 2.0% (crude extract) | Nannochloropsis sp. | In vitro NHDF cells |

Enhance the expression of HAS-2 in a dose-dependent manner | [45] |

| Lipid extract | Myristic acid, palmitoleic acid, and α-linolenic acid | Macrocystis pyrifera | In vitro Three-dimensional cultures of HaCaT cells |

Barrier protective effect | [46] |

| Oily extract | Rich in carotenoids and phenolic compounds (cream with 0,5% extract) |

Cladophora glomerata | Randomized clinical study | Moisturizing improvement | [47] |

| Lipid extract | Palmitic, oleic, myristic, stearic, and linoleic acids | Himantothallus grandifolius, Plocamium cartilagineum, Phaeurus antarcticus, and Kallymenia antarctica | In vitro (HaCaT cells) |

Protection of skin barrier function | [48] |

| Oily extract | Up to 99% of fatty acids + less than 1% of xanthophyll’s | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | In vitro Human keratinocytes |

Stimulation and protection of proteasome peptidase activities | [49] |

| Encapsulated (liposomal) lipid exact | ω-3 fatty acids, and standardized to fucoxanthin levels |

Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Randomized, clinical split-face study |

Soothing effect Barrier function improvement |

[50] |

| Lipid extract | Rich in phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatidylethanolamine | Nannochloropsis oceanica | In vitro | Down-regulation of sphingomyelin Upregulation of ceramides CER[NDS] and CER[NS] |

[51] |

|

Oily extract (Bio-Based Algae Oil) |

Triglyceride (three monounsaturated oleic acid chains with very low polyunsaturated fatty acid content) |

Not described (INCI name Triolein) |

In vivo Single-blind study |

Skin hydration increase TEWL decrease |

[52] |

| Phycocyanin | Spirulina-derived C-phycocyanin |

Spirulina sp. (Arthrospira sp.) |

In vitro (HaCaT cells) |

Protection and maintaining the expression of filaggrin, involucrin, and loricrin after UV radiation |

[53] |

| Aqueous extract | 50 and 70% proteins (dry weight) 8-14% polysaccharides |

Spirulina sp. (Arthrospira sp.) |

Clinical study (Gel-cream formulation with 0,1% w/w spirulina extract) |

Skin hydration increase TEWL decrease Skin microrelief improved Reduction of the surface roughness |

[54] |

| Aqueous extract | 50 and 70% proteins (dry weight) |

Spirulina sp. (Arthrospira sp.) |

Clinical study (Gel-cream formulation with 0,1% w/w spirulina extract) |

Skin hydration increase TEWL decrease Skin microrelief improved Reduction of the surface roughness |

[55] |

| Dry extract | NR |

Spirulina sp. (Arthrospira sp.) |

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial (Formulation containing olive oil and spirulina extract) | Skin hydration increase TEWL decrease Skin barrier improvement |

[56] |

| Dry extract | NR (Cream with 5% complex of Dead Sea Mineral salts + algae extract + “desert plants”) |

Dunaliella salina | Clinical trial | Skin roughness decrease Skin moisturizing improvement |

[57] |

| Polysaccharide Type | Moist Retention | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| LMW polysaccharides (brown algae) | The lower the molecular weight, the greater the moist retention capacity Higher than HA |

[96] |

| Sulfated polysaccharide (Ulva lactuca) | Higher than glycerol (43% vs 34%) |

[97] |

| Sulfated polysaccharides (Enteromorpha prolifera) | The higher the sulphate content, the higher the water retention Close to HA |

[98] |

| Brown and red algae polysaccharides | Higher in Sargassum horneri than in Porphyra yezoensis | [99] |

| Sulfated polysaccharide (fucoidan-rich extract) (Sargassum vachellianum) | Higher (65.84%) than glycerol (51.35%) | [100] |

| Polysaccharides-rich extract (Caulerpa microphysa) | Better than collagen and HA, and similar to urea | [101] |

| Polysaccharides-rich extract (Nostoc) | Higher (78.5%) than chitosan (75.2%), and urea (62.7%) | [29] |

| Compound | Specie / Strain | Claim | Patent Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein and peptides (dry powder) | Porphyra sp., Wakame sp., Spirulina sp., and Chlorella sp. | Glossing and moisturizing skin (cream) | EP1433463B1 |

| Extracts | Chondrus crispus and Codium tomentosum | Skin moisturizing | CN110339102A |

| Extracts of coccoid filamentous cyanobacteria | Cyanobacterium sp. | Enhancement of skin barrier | US8795679B2 |

| Lysate | Chlamydocapsa sp. | Enhancement of skin barrier | US8206721B2 |

| Cell algae or extracts | Prototheca, Auxenochlorella, Chlorella or Parachlorella genus | Improvement of skin hydration | US20150352034A1 |

| Extracts | Senedesmus sp. | Protection against UV damage and moisturizing | KR101825683B1 |

| Liposomes or algaesomes | Dunaliella salina | Moisturizing agent | KR102008870B1 |

| Extract | Leptolyngbya tenuis | Promote the production of Aquaporine-3 | JP2022029111A |

| Extract | Chlorella sorokiniana | Strengthening the skin barrier | FR3064481A1 |

| Peptide extract | Spirulina | Restructuring the cutaneous barrier | FR2857978, 27 |

| Extract |

Haematococcus pluvialis (H. lacustris) |

Moisturizing mask | CN106963670B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).