1. Introduction

The vast majority of patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD) carries an history of hypertension and takes several drugs for maintaining blood pressure (BP) values within the normal range [

1]. Achieving optimal BP control in patients with IHD has a positive impact on their prognosis [

2] and it is among the most important pursued goals during cardiac rehabilitation programs [

3]. Physical activity alongside other non-pharmacological treatments, is a well-established intervention for preventing the rise of BP in pre-hypertension and for lowering BP in subjects with hypertension [

4,

5]. While all types of exercise have been shown to reduce BP, continuous aerobic exercise has the most robust evidence supporting its BP-lowering effects [

6,

7]. Isometric exercise (IE) has been shown to effectively reduce both systolic and diastolic BP with effects comparable to those of aerobic training [

8,

9]. This modality may be particularly advantageous in the management of hypertension among older adults, as it can be safely performed even by patients with limited functional capacity or those who have contraindications to aerobic activity [

10]. Additionally, IE offers a time-efficient option, as short sessions lasting 15–20 minutes have demonstrated significant benefits in BP reduction [

11]. The use of IE for the treatment of hypertension in patients with IHD has been scarcely investigated to date. In fact, concerns about causing an excessive increase in systolic BP and hemodynamic overload of the left ventricle (LV) have prevented the use of IE in this population. It has been demonstrated that the increase in blood pressure (BP) during isometric exercise is directly proportional to both the amount of muscle mass engaged and the intensity of the contraction. Consequently, different isometric exercises elicit distinct effects on BP and hemodynamic parameters. In a recent study involving patients with IHD, low-intensity bilateral knee extension was associated with a significant rise in systolic BP and a marked reduction in myocardial work efficiency. In contrast, low-intensity isometric handgrip (IHG) produced only minor changes in BP and exhibited neutral hemodynamic effects, with no significant impact on left ventricular contractile efficiency [

12]. While low-intensity IHG appears to be a suitable IE modality for IHD patients in terms of tolerability and safety, it still remains to be established if it is also effective in reducing BP in this population. The assessment of LV myocardial work through speckle tracking echocardiography is an accurate, noninvasive technique for evaluating LV contraction efficiency [

13] and, it has been used for investigating the effects of exercise on myocardial function [

14]. In the present study, we compared the hemodynamic responses and post-exercise BP effects elicited by single bouts of IHG exercise performed at high versus low intensity. The primary endpoint was changes in systolic BP during the post-exercise recovery phase. Secondary endpoints included changes in LV myocardial work efficiency during the exercise and diastolic BP during the post-exercise phase.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

A total of 56 male and female patients involved in secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation programs at San Raffaele IRCCS of Rome were enrolled in the study. Inclusion criteria were: age over 50 years; diagnosed hypertension; history of IHD encompassing: prior acute coronary syndrome (ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI, or unstable angina), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG); stable clinical conditions (no hospitalizations in the past 6 months and unchanged pharmacological therapy for at least 3 months); physically active: patients were considered exercisers if a planned and structured physical activity was performed for at least 30 min on three days or more during the past three months [

15]. Exclusion criteria included: signs or symptoms of myocardial ischemia or complex ventricular arrhythmias at rest or during exercise testing; incomplete revascularization; permanent or recurrent atrial fibrillation; resting BP ≥160/100 mmHg despite treatment; significant valvular disease; hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; having an history of chronic heart failure or having signs and/or symptoms of heart failure. Having an echocardiography LV ejection fraction below 40%. Additional exclusions included extracardiac conditions such as anemia (blood haemoglobin levels <10.5 g/dL), advanced COPD (with GOLD stage III–IV), and symptomatic peripheral artery disease (Leriche-Fontaine stage II–IV), poor acoustic window. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of San Raffaele IRCCS (Protocol No. 28/2024), and all participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The recruitment period started in October 2024 and was concluded in March 2025.

2.2. Study Design

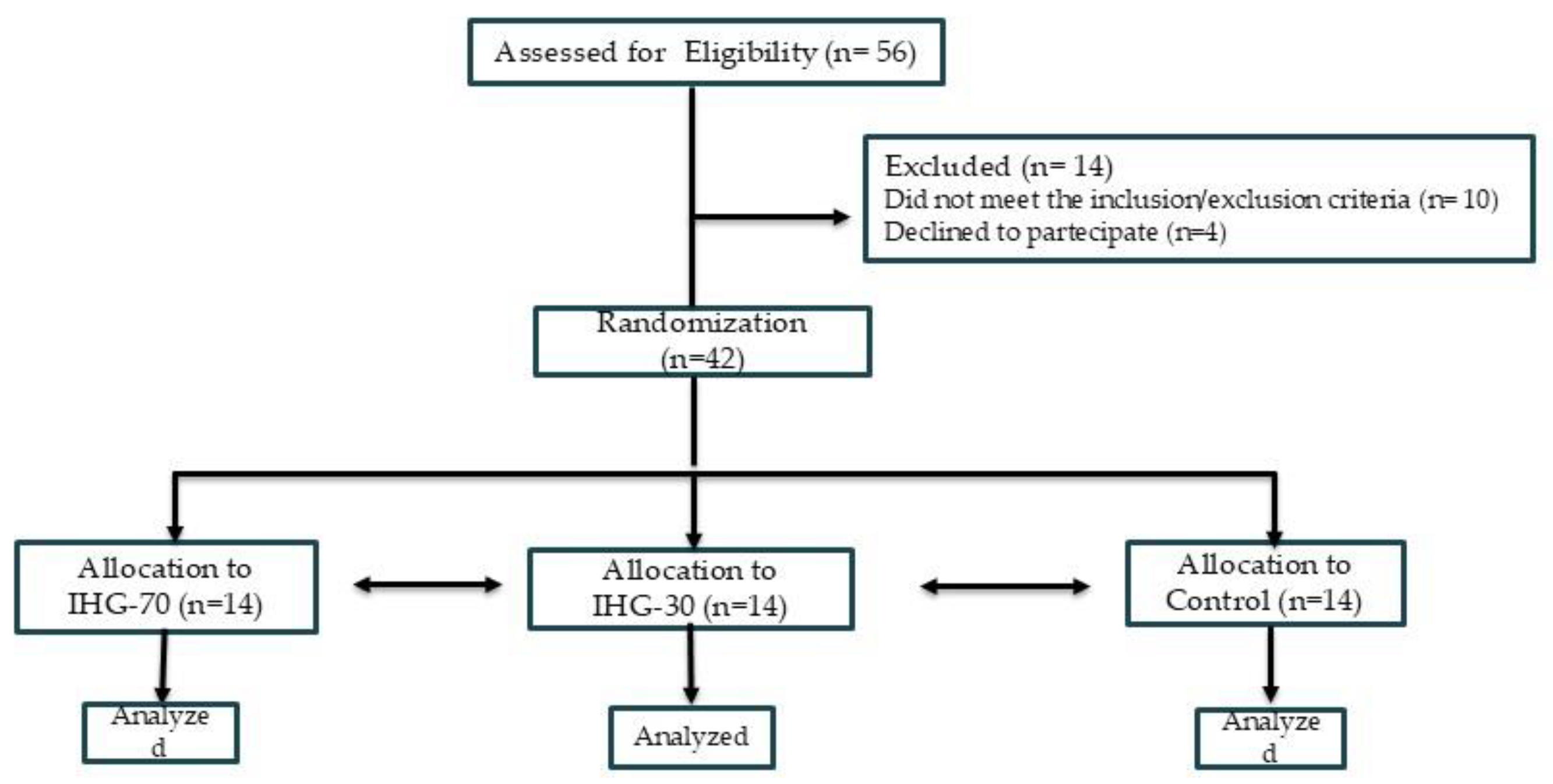

Figure 1 summarizes the study flow-chart. This research was conceived as a three-armed parallel randomized pilot study in which patients were alternately allocated to one of the following groups, at a ratio of 1:1:1. (1) high-intensity IHG in which IE was performed at 70% of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) (IHG-70) ; (2) low-intensity IHG in which IE was performed at 30% of MVC (IHG-30); (3) control, no exercise. The randomization code was developed by a computer random-number generator to select random permuted blocks. This was a single-blinded study in which the sonographers who performed the offline analysis of echocardiographic parameters were blinded to patient group allocation. The initial assessment (Visit 1) included: collection of clinical history, measurement of resting BP and heart rate, anthropometric measurements (weight and height); a symptom-limited ergometric test. The ergometric test was conducted on a cycle ergometer (Quark CPET, COSMED, Frascati, Italy) using a ramp protocol with 20-watt increments every 2 minutes. Patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study and provided written informed consent. A second evaluation (Visit 2) was conducted within one week of Visit 1. During visit 2 which participants were familiarized with the device used in the experimental session. The experimental session for each participant was completed within one week following Visit 2.

2.3. Experimental Sessions

All experimental sessions were performed in the morning, between 8.30 am and 12 am. Patients were required to avoid consuming coffee and smoking cigarettes for at least 12 hours before the sessions. A light breakfast was allowed at least 2 hours before the session. Patients were allowed to take regularly their medications of the morning on the day of the session. The experiments were carried out with participants lying on a bench, positioned with their backs reclined at a 120-degree angle from the horizontal. A sonographer was positioned on the participant’s left side, and a sphygmomanometer cuff (GIMA, S.p.A., Gessate [MI], Italy) was placed on the arm opposite the dominant one used for handgrip exercises. The MVC was determined by having each participant perform three maximal handgrip efforts, each lasting 3–5 seconds, with one-minute rest intervals between attempts. Exercise intensity was then set at 30% of MVC for the low-intensity group and at 70% for the high-intensity group. The isometric exercise phase lasted 3 minutes, during which participants were instructed to maintain a constant force. To avoid Valsalva maneuvers, they were guided to breathe normally, maintaining a steady rhythm and depth. Echocardiographic imaging began after the first minute of exercise. The sonographer remained on the participant’s left side, and BP was measured via a cuff on the right arm. Echocardiographic acquisitions and BP measurements were performed at three time points: at rest; during the isometric exercise, beginning one minute after exercise onset; and 15 minutes after the exercise end. BP measurement but no echocardiography were also carried out at 30 and 45 and 60 minutes after completion of the isometric effort. For the control group, the same measurement timeline was followed, but participants remained at rest for the entire duration of the session. They were also positioned supine on a bench with a 120-degree recline, mirroring the setup used for the intervention groups.

2.4. Echocardiography

All echocardiographic assessments were conducted using the Vivid E95® cardiovascular ultrasound system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) equipped with a 4.0 MHz transducer, throughout the duration of the study. Examinations were performed with single-lead ECG monitoring, and image acquisition followed the recommendations of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging [

16]. All images were digitally archived for offline analysis. Strain analyses were carried out offline by two trained technicians that used a proprietary software (EchoPAC, version 10.8; GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horten, Norway) and who were blinded to patient group allocation. Left ventricular (LV) diastolic function was evaluated using the E/A ratio, calculated as the ratio between early (E-wave) and late (A-wave) diastolic filling velocities. Color tissue Doppler imaging was performed in the apical four-chamber view, with the sample volume positioned at the lateral mitral annulus. The E/e’ ratio was defined as the ratio between E-wave velocity and the average of septal and lateral e’-wave velocities. Left atrial (LA) volume was measured from apical four-chamber and two-chamber views at end-systole, before mitral valve opening, using the biplane Simpson’s method. LA volume index (LAVI) was calculated by dividing LA volume by body surface area. LV end-diastolic (LVEDV) and end-systolic volumes (LVESV) were measured from apical four- and two-chamber views, and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was computed using the modified Simpson’s method. Stroke volume (SV) was calculated as LVEDV minus LVESV, and cardiac output (CO) was derived as the product of SV and heart rate. Ejection fraction was also expressed as EF = (EDV – ESV) / EDV. Global longitudinal strain (GLS) of the LV was measured from apical four-chamber, three-chamber, and two-chamber views. The software automatically tracked endocardial borders and computed the peak negative systolic strain value in each segment, which represented maximum contractility. Manual corrections were made as needed to optimize contouring. The overall LVGLS was determined as the average of all segmental values. LA strain analysis was conducted using apical four-chamber and two-chamber views. The software automatically traced both endocardial and epicardial borders using R-R gating, with the R-wave as the reference point. If necessary, manual adjustments were applied. Control points were placed along the central myocardial curve to define the region of interest. Longitudinal strain curves were generated for each segment, and average segmental curves were computed. Reservoir, conduit, and contractile LA strain components were derived from the full strain curve. Myocardial work was assessed during the period between mitral valve closure and opening. Peak atrial contraction strain (PACS) was defined as the positive peak strain occurring at the onset of LV diastole, before atrial contraction; peak atrial longitudinal strain (PALS) was defined as the positive peak occurring during LV systole, at the end of atrial diastole. A 17-segment polar (bull’s-eye) plot was generated to represent regional and global myocardial work. The global work index (GWI) was calculated as the total area under the work curve between mitral valve closure and opening. Global constructive work (GCW) included positive work during systolic shortening and negative work during isovolumetric relaxation lengthening. Global wasted work (GWW) was defined as work performed during inappropriate shortening in isovolumetric relaxation and lengthening during systole. Global work efficiency (GWE) was calculated as the ratio of GCW to the sum of GCW and GWW. Timing of valvular events was determined using pulsed-wave Doppler at the levels of the mitral and aortic valves and confirmed through 2D imaging in long-axis and apical views [

17].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

This study was designed as a pilot investigation; therefore, no formal a priori sample size calculation was conducted regarding the expected differences between the two active groups. However, we hypothesized that a least one treatment would reduce systolic BP compared to control. Therefore, in order to establish the study sample size we utilized the effect size reported from previous studies comparing BP effects of IHG vs control [

18,

19]. We estimated that, to detect a 6.5 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure with an estimated standard deviation of 6.0 mmHg, assuming: 3 groups (2 treatment, 1 control), α = 0.05 (adjusted to 0.025 for 2 comparisons), power = 80%, 14 participants per group for a total of 42 participants were needed. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The assumption of normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. To evaluate changes in variables across the different phases of the experimental sessions a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA was applied, with Bonferroni correction used for post hoc comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages and compared using the chi-square test. All statistical analyses, data processing, and graphical presentation were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0.

3. Results

The study enrolled 56 patients. Of these, 8 were excluded due to excessively high BP values, 2 for having a poor acoustic window and 4 withdrew consent, refusing to continue participation in the study. Forty-two patients were therefore randomly assigned to one of the three study groups, with each group comprising 14 patients. All patients randomized completed the study and their data were analysed. Baseline clinical features of the patients are reported in

Table 1.

At baseline the three groups were comparable regarding age, anthropometric parameters, rate of comorbidities and pharmacological therapy. The average number of medications taken for lowering BP was 2.8±0.8. All patients analysed had a previous myocardial infarction that was STEMI (80.9%); anterior STEMI:61.6%, inferior STEMI 38.4%. Twenty-six out of 42 (61.9%) were overweight and thirteen out of 42 (30.9%) were obese. Experimental sessions were well tolerated and no symptoms occurred during the exercise and the recovery phases.

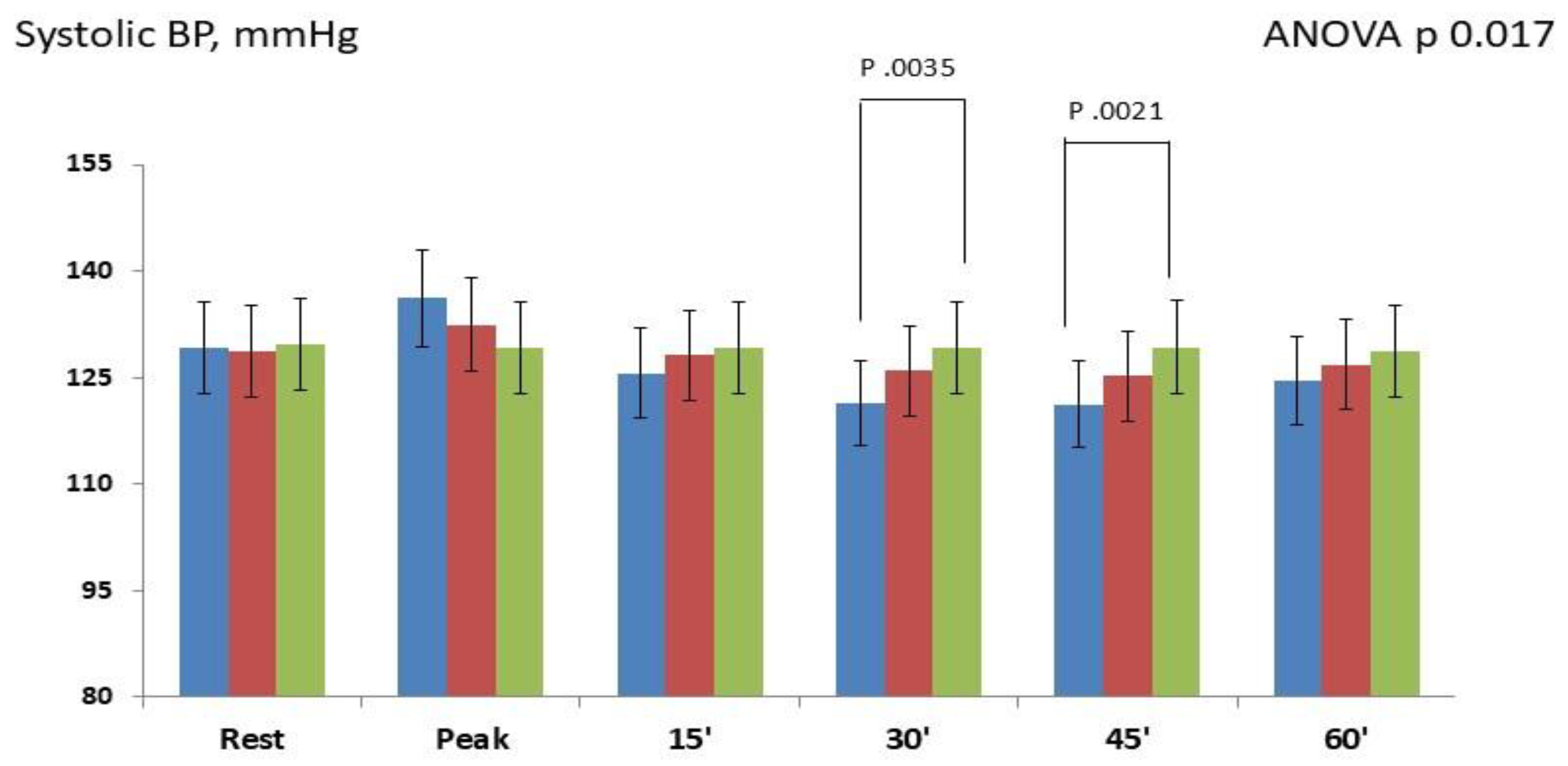

Changes in systolic BP occurring at different time-points are showed in

Figure 2.

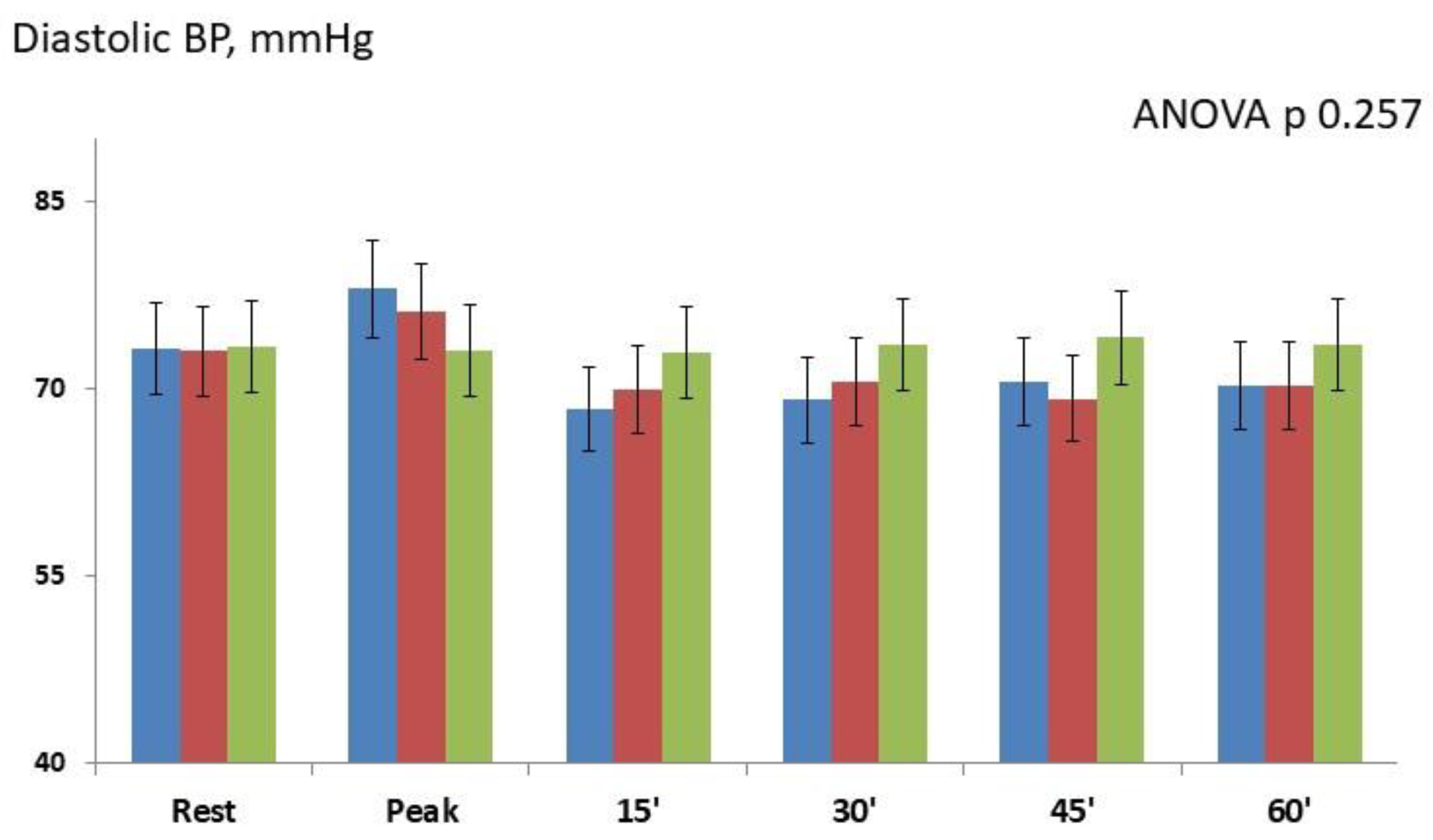

Overall The repeated-measures ANOVA showed significant changes between the three study groups (p 0.017). During the exercise phase, systolic BP modestly increased in both IHG-70 (+7.0±2.1; p 0.065) and IHG 30 (+3.2±1.6; p 0.231) compared to control; post-hoc Bonferroni tests did not show significant differences between the two active groups and versus control. During the post-exercise phase: post-hoc Bonferroni tests showed that systolic BP significantly decreased between IHG-70 and control at 30 minutes (-7.7±1.9; p 0.035 ) and 45 minutes (-8.1±2.3; p 0.021). There were not significant changes between the two active groups with the width differences observed at 30 minutes (-4.5±1.6; p 0.084) and between IHG-30 and control. Changes in diastolic BP occurring at different timepoints are showed in

Figure 3.

There were not significant differences in diastolic BP between the two active groups and between IHG-70 and IHG-30 versus control (repeated-measures ANOVA p 0.257). There were not significant changes in GCW (ANOVA p 0.372) and GWW (ANOVA p 0.298) between the two active groups and between active groups and control. There were not significant changes in GWE between the two active groups and between active groups and control at different timepoints (ANOVA p 0.154,). E/e’ ratio, PALS and PACS were unchanged in all groups.

No significant changes occurred between IHG-70 and IHG 30 and between IHG-30 and control at different timepoints.

4. Discussion

The addition of daily short sessions of isometric exercise (IE) as an adjunctive strategy for the long-term management of hypertension in patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD) who are already receiving antihypertensive therapy appears to be a promising approach. However, it remains unclear which type of IE is most suitable for this population, specifically, one that combines minimal hemodynamic impact during execution with a clinically significant post-exercise BP reduction. The present study comparatively evaluated the acute hemodynamic responses and post-exercise BP-lowering effects of single bouts of IHG performed at high versus low intensity. We found that both intensities elicited only modest increases in BP and did not produce significant detrimental hemodynamic changes during the exercise phase. However, only the higher-intensity protocol induced a significant post-exercise BP reduction compared with control.

Hemodynamic tolerability. In this study, systolic BP increases during both IHG-30 and IHG-70 were modest and left ventricular (LV) myocardial work efficiency remained unchanged. These findings are consistent with previous observations in hypertensive older women [

20] and in patients with IHD [

12]. However, this is the first study assessing the impact of high intensity IHG on LV myocardial work and efficiency. The finding that even high-intensity IHG did not induce significant hemodynamic effects suggests that this mode of IE is as safe as low-intensity IHG for patients with hypertension and IHD. This research showed no changes in metrics of diastolic function as E/e’ ratio and PALS during the isometric efforts. This result is probably due to the modest increase in afterload observed during both IHG-30 and IHG-70 and it can, as a first hypothesis, be attributed to the effectiveness of the pharmacological therapy received by the enrolled patients; however, it could also be related to the training status of the patients. In the study of Rovithis et al [

21], who compared changes in diastolic function during IHG in physically active versus sedentary men, the group of active men did not show a statistically significant change in E/e’ ratio in response to IHE, while the inactive participants’ E/e’ ratio was higher at peak activity in the IHG. Finding of this research differ from those of Javidi et al [

22]., who reported a significant systolic BP rise during high-intensity IHG. This discrepancy may be attributable to differences in study populations; in our cohort, patients were already receiving multiple antihypertensive agents, which may have attenuated the BP response during the isometric effort.

Post-exercise hypotension. In this study a significant reduction in systolic BP was observed only after IHG performed at high intensity. This is a unique finding in the population of IHD patients that needs to be confirmed and expanded. Results of the present study comply with the study of Javidi et al [

22] regarding the BP reduction in the post-exercise phase: who observed that high-intensity IHG evoked a greater BP decreased compared to low-intensity IHG On the contrary, BP did not decrease after IHG-30. The effects of low-intensity IHG on BP are controversial: despite it has been demonstrated that a single bout of low-intensity IHG reduces BP during the recovery phase in pre-hypertensive and hypertensive patients [

23,

24,

25] , such findings have not been consistently confirmed [

20,

26]. This variable response can be expected since the BP response to IE is influenced by several factors including age, gender, comorbidities and number of medications taken [

27]. Loaiza-Betancur et al. [

28] showed that low-intensity IHG was more effective in reducing BP values in subjects aged under 45 years. Similarly, in a recent study, Melnikov et al [

29], in young physically active men, documented significant BP reduction after IHG performed at 20% of MVC. Instead, the results obtained in the present study suggest that low-intensity IHG is not capable of significantly reducing post-exercise BP, at least in elderly patients with IHD, carrying also other comorbidities, and who were receiving, on average, more than two antihypertensive medications. We think that the present study adds useful information regarding the choice of exercise modality and intensity aimed at the non-pharmacological management of hypertension in patients with IHD. Moreover, it emphasizes the utility of performing a non-invasively echocardiography assessment of the hemodynamic response before starting an IE protocol. intensities were characterized by a mild comparable hemodynamic response since

Limitations. The main limitation of the present study is the small sample size that did not allow to reveal significant differences in the BP-lowering effect between the two active groups. Therefore, adequately powered future investigations will be required to determine whether high-intensity IHG is more effective than low-intensity IHG in reducing BP. However, it should be noted that since this study was powered enough to reveal differences between active groups and control, its result can be considered reliable. The measurement of BP during the post-exercise phase was very short therefore the duration of the hypotensive effect induced by high-intensity IHG exercise remains undetermined. The results of this study were obtained from a single bout of IHG, during which patients were instructed to maintain a constant contraction for three minutes. It cannot be excluded that alternative protocols might elicit different BP responses. Caution in interpreting the data is needed since strain echocardiography has several technical limitations [

30,

31]; therefore, further confirmations of our results should also be obtained with alternative diagnostic techniques as, for example, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, both low and high-intensity IHG exercises were hemodynamically well tolerated by patients with IHD but only high-intensity IHG induced a significant post-exercise systolic BP reduction. The use of high-intensity IHG appears to be a safe and effective non-pharmacological intervention for reducing BP in IHD patients. Further studies should assess whether it is more effective than low-intensity IHG in reducing BP.

Author Contributions

G.C., M.A.P. and F.I., contributed to the conceptualization of the paper; M.V. (Matteo Vitarelli). S.V., S.F., G.M., B.S., D.M.G., V.D.A., and A.G. prepared the initial draft after acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the results; V.M. (Valentina Morsella), M.V. (Maurizio Volterrani), and V.M. (Vincenzo Manzi) substantively revised it. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding of the Italian Ministry of Health [Ricerca corrente].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of San Raffaele IRCCS of Rome (protocol code 28/2024, approval date: July, 15th 2024). Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been also obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IHG |

Isometric handgrip |

| BP |

Blood pressure |

| IHD |

ischemic heart disease |

| MVC |

maximal voluntary contraction |

| IE |

Isometric exercise |

| LV |

Left ventricle |

| PCI |

Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| CABG |

Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| LA |

Left atrial |

| LAVI |

LA volume index |

| LVEDV |

LV end-diastolic |

| LVESV |

LV End-systolic volumes |

| LVEF |

LV ejection fraction |

| SV |

Stroke volume |

| CO |

Cardiac output |

| GLS |

Global longitudinal strain |

| PACS |

Peak atrial contraction strain |

| PALS |

Peak atrial longitudinal strain |

| GWI |

Global work index |

| GCW |

Global constructive work |

| GWW |

Global wasted work |

| GWE |

Global work efficiency |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

References

- Weber T, Lang I, Zweiker R, Horn S, Wenzel RR, Watschinger B, Slany J, Eber B, Roithinger FX, Metzler B. Hypertension and coronary artery disease: epidemiology, physiology, effects of treatment, and recommendations : A joint scientific statement from the Austrian Society of Cardiology and the Austrian Society of Hypertension. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016 Jul;128(13-14):467-79. [CrossRef]

- Martinez R, Soliz P, Campbell NRC, Lackland DT, Whelton PK, Ordunez P. Association between population hypertension control and ischemic heart disease and stroke mortality in 36 countries of the Americas, 1990-2019: an ecological study. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2022 ; 16;46:e143. [CrossRef]

- Taylor RS, Dalal HM, McDonagh STJ. The role of cardiac rehabilitation in improving cardiovascular outcomes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;;19(3):180-194. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy JW, McCarthy CP, Bruno RM, Brouwers S, Canavan MD, Ceconi C, Christodorescu RM, Daskalopoulou SS, Ferro CJ, Gerdts E, Hanssen H, Harris J, Lauder L, McManus RJ, Molloy GJ, Rahimi K, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Rossi GP, Sandset EC, Scheenaerts B, Staessen JA, Uchmanowicz I, Volterrani M, Touyz RM; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2024 Oct 7;45(38):3912-4018. [CrossRef]

- Hanssen H, Boardman H, Deiseroth A, Moholdt T, Simonenko M, Kränkel N, Niebauer J, Tiberi M, Abreu A, Solberg EE, Pescatello L, Brguljan J, Coca A, Leeson P. Personalized exercise prescription in the prevention and treatment of arterial hypertension: a Consensus Document from the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) and the ESC Council on Hypertension. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022 ;19;29(1):205-215. [CrossRef]

- Whelton SP, Chin A, Xin X, He J. Effect of aerobic exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Apr 2;136(7):493-503. [CrossRef]

- Cao L, Li X, Yan P, Wang X, Li M, Li R, Shi X, Liu X, Yang K. The effectiveness of aerobic exercise for hypertensive population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019 Jul;21(7):868-876. [CrossRef]

- Inder JD, Carlson DJ, Dieberg G, McFarlane JR, Hess NC, Smart NA. Isometric exercise training for blood pressure management: a systematic review and meta-analysis to optimize benefit. Hypertens Res. 2016 Feb;39(2):88-94. [CrossRef]

- Hansford HJ, Parmenter BJ, McLeod KA, Wewege MA, Smart NA, Schutte AE, Jones MD. The effectiveness and safety of isometric resistance training for adults with high blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens Res. 2021 Nov;44(11):1373-1384. [CrossRef]

- Miura, S. Evidence for exercise therapies including isometric handgrip training for hypertensive patients. Hypertens. Res. 2024, 48, 846–848.

- Vitarelli M, Laterza F, Peñín-Grandes S, Perrone MA, Santos-Lozano A, Volterrani M, Marazzi G, Manzi V, Padua E, Sposato B, Morsella V, Iellamo F, Caminiti G. Post-Exercise Hypotension Induced by a Short Isometric Exercise Session Versus Combined Exercise in Hypertensive Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease: A Pilot Study. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2025 May 25;10(2):189. [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, G.; Marazzi, G.; Volterrani, M.; D’Antoni, V.; Fecondo, S.; Vadalà, S.; Sposato, B.; Giamundo, D.M.; Vitarelli, M.; Morsella, V.; et al. Effect of Different Isometric Exercise Modalities on Myocardial Work in Trained Hypertensive Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease: A Randomized Pilot Study. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 108. [CrossRef]

- Marzlin N, Hays AG, Peters M, Kaminski A, Roemer S, O’Leary P, Kroboth S, Harland DR, Khandheria BK, Tajik AJ, Jain R. Myocardial Work in Echocardiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023 Feb;16(2):e014419. [CrossRef]

- Erevik CB, Kleiven Ø, Frøysa V, Bjørkavoll-Bergseth M, Chivulescu M, Klæboe LG, Dejgaard L, Auestad B, Skadberg Ø, Melberg T, et al. Myocardial inefficiency is an early indicator of exercise-induced myocardial fatigue. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023 Jan 11;9:1081664. [CrossRef]

- 2021. Asgfetapte PWK. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluer. 2021.

- Nagueh S.F., Smiseth O.A., Appleton C.P., Byrd B.F., 3rd, Dokainish H., Edvardsen T., Flachskampf F.A., Gillebert T.C., Klein A.L., Lancellotti P., et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2016;17:1321–1360. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos K., Özden Tok Ö., Mitrousi K., Ikonomidis I. Myocardial Work: Methodology and Clinical Applications. Diagnostics. 2021;11:573. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2: e004473. 6.

- Carlson DJ, Dieberg G, Hess NC, Millar PJ, Smart NA. Isometric exercise training for blood pressure management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Mar;89(3):327- 34. [CrossRef]

- Olher Rdos R, Bocalini DS, Bacurau RF, Rodriguez D, Figueira A Jr, Pontes FL Jr, Navarro F, Simões HG, Araujo RC, Moraes MR. Isometric handgrip does not elicit cardiovascular overload or post-exercise hypotension in hypertensive older women. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:649-55. [CrossRef]

- Rovithis D, Anifanti M, Koutlianos N, Teloudi A, Kouidi E, Deligiannis A. Left Ventricular Diastolic Response to Isometric Handgrip Exercise in Physically Active and Sedentary Individuals. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022 Nov 11;9(11):389. [CrossRef]

- Javidi, M.; Ahmadizad, S.; Argani, H.; Najafi, A.; Ebrahim, K.; Salehi, N.; Javidi, Y.; Pescatello, L.S.; Jowhari, A.; Hackett, D.A. Effect of Lower- versus Higher-Intensity Isometric Handgrip Training in Adults with Hypertension: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 287. [CrossRef]

- van Assche T, Buys R, de Jaeger M, Coeckelberghs E, Cornelissen VA. One single bout of low-intensity isometric handgrip exercise reduces blood pressure in healthy pre- and hypertensive individuals. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2017 Apr;57(4):469-475. [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante PA, Rica RL, Evangelista AL, Serra AJ, Figueira A Jr, Pontes FL Jr, Kilgore L, Baker JS, Bocalini DS. Effects of exercise intensity on post-exercise hypotension after resistance training session in overweight hypertensive patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2015 Sep 18;10:1487-95. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, Y., Yamaki, Y., Takahashi, T. et al. Effects of low-intensity isometric handgrip training on home blood pressure in hypertensive patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hypertens Res 2025;48:710–719. [CrossRef]

- Silva GO, Farah BQ, Germano-Soares AH, Andrade-Lima A, Santana FS, Rodrigues SL, Ritti-Dias RM. Acute blood pressure responses after different isometric handgrip protocols in hypertensive patients. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018 Oct 18;73:e373. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence MM, Cooley ID, Huet YM, Arthur ST, Howden R. Factors influencing isometric exercise training-induced reductions in resting blood pressure. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015 Apr;25(2):131-42. Epub 2014 Apr 22. PMID: 24750330. [CrossRef]

- Loaiza-Betancur AF, Chulvi-Medrano I. Is Low-Intensity Isometric Handgrip Exercise an Efficient Alternative in Lifestyle Blood Pressure Management? A Systematic Review. Sports Health. 2020 Sep/Oct;12(5):470-477. [CrossRef]

- Melnikov VN, Komlyagina TG, Gultyaeva VV, Uryumtsev DY, Zinchenko MI, Bryzgalova EA, Karmakulova IV, Krivoschekov SG. Time course of cardiovascular responses to acute sustained handgrip exercise in young physically active men. Physiol Rep. 2025 Apr;13(7):e70286. [CrossRef]

- Mirea O, Pagourelias ED, Duchenne J, Bogaert J, Thomas JD, Badano LP, Voigt JU. EACVI-ASE-Industry Standardization Task Force. Intervendor Differences in the Accuracy of Detecting Regional Functional Abnormalities: A Report From the EACVI-ASE Strain Standardization Task Force. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018; 11(1):25-34. [CrossRef]

- Rösner A, Barbosa D, Aarsæther E, Kjønås D, Schirmer H, D’hooge J. The influence of frame rate on two-dimensional speckle-tracking strain measurements: a study on silico-simulated models and images recorded in patients. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015; 16(10):1137-47. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).