Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

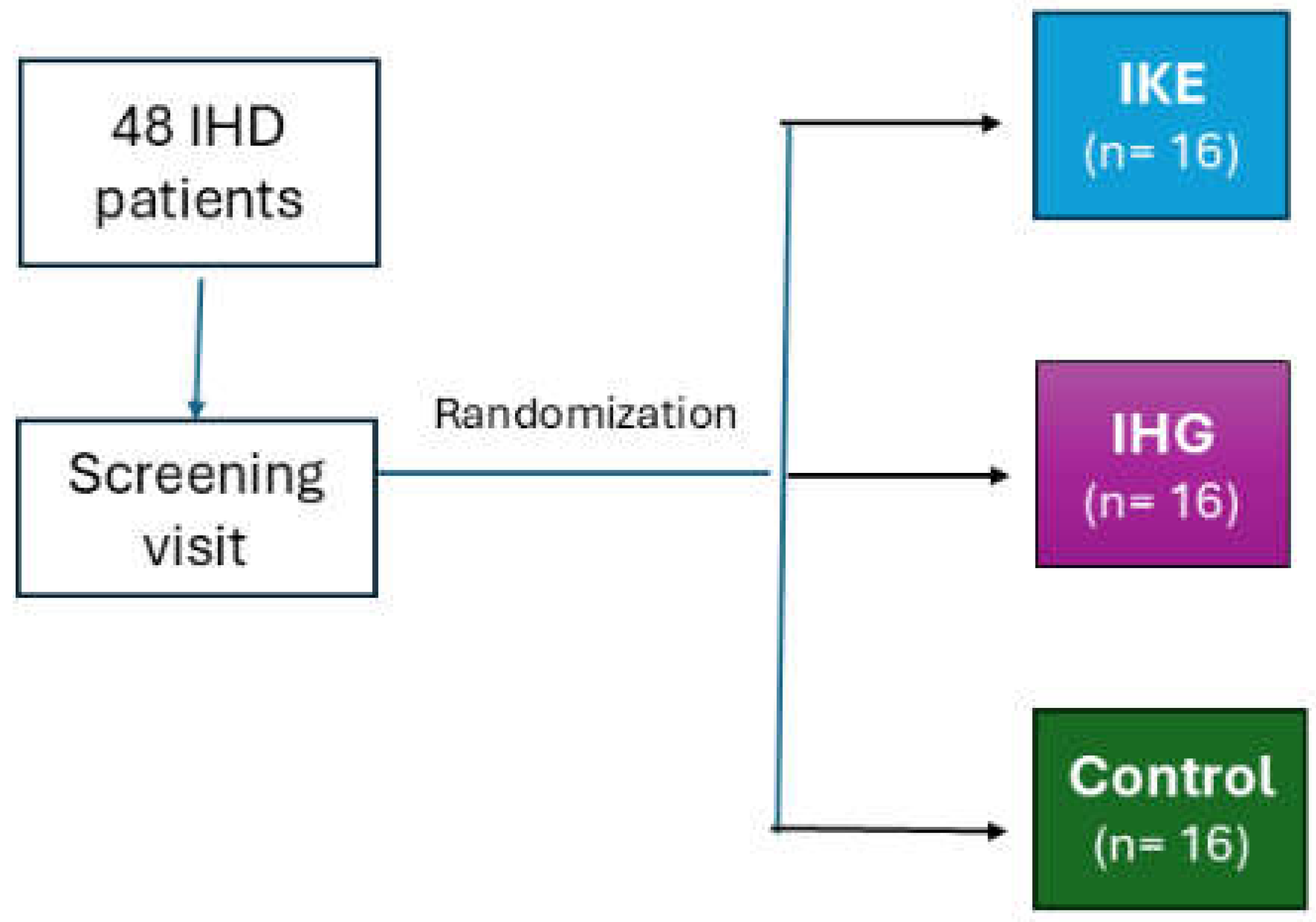

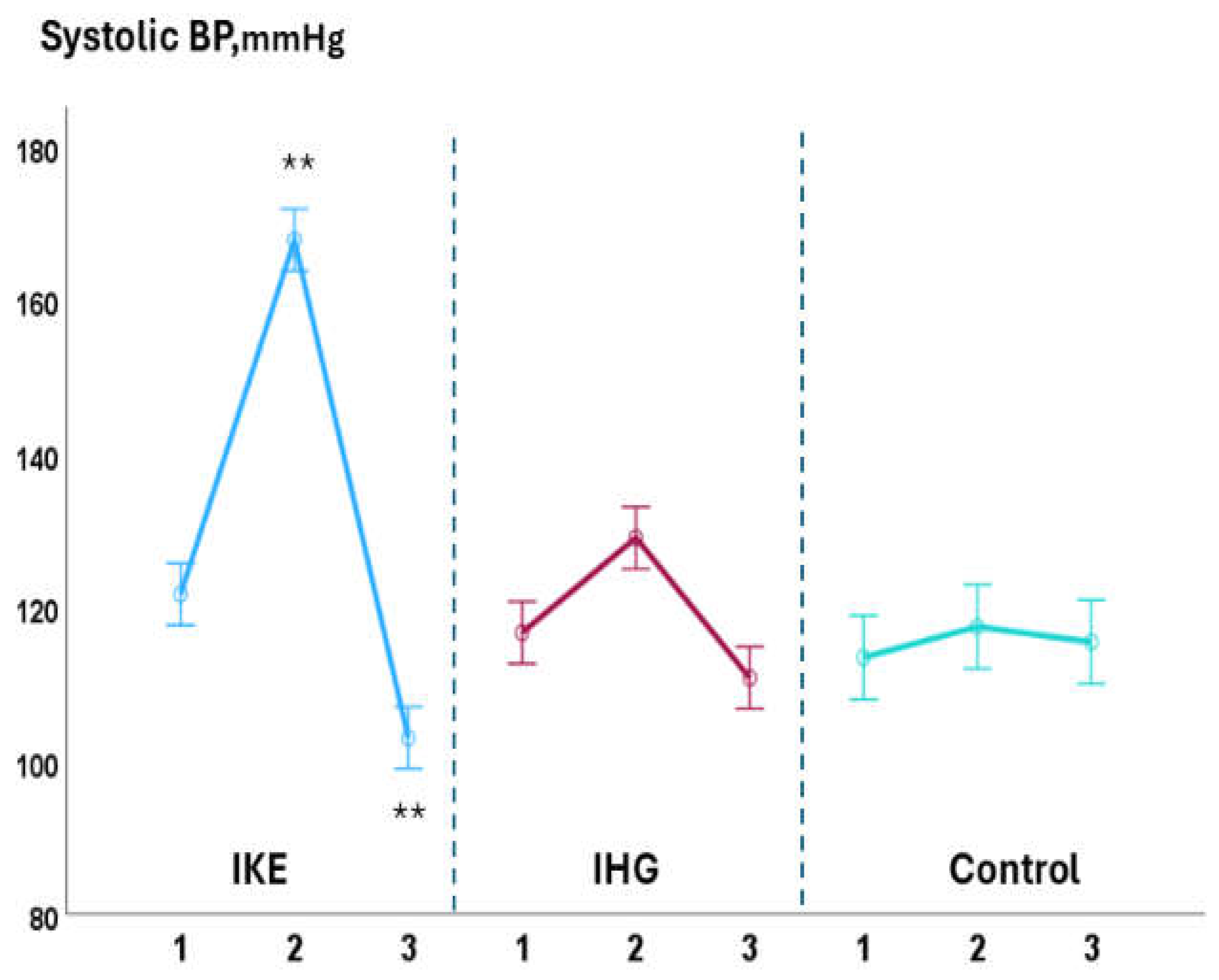

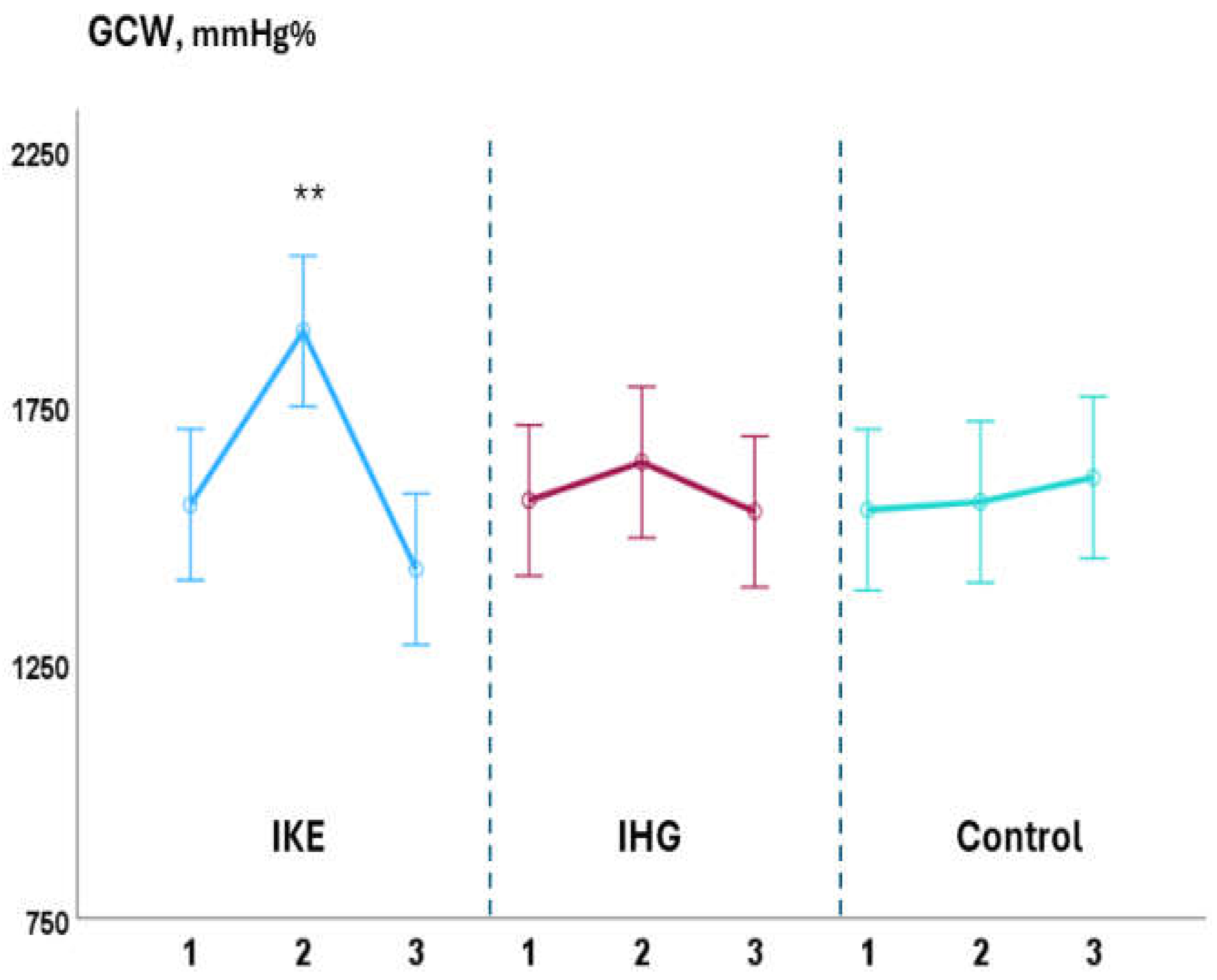

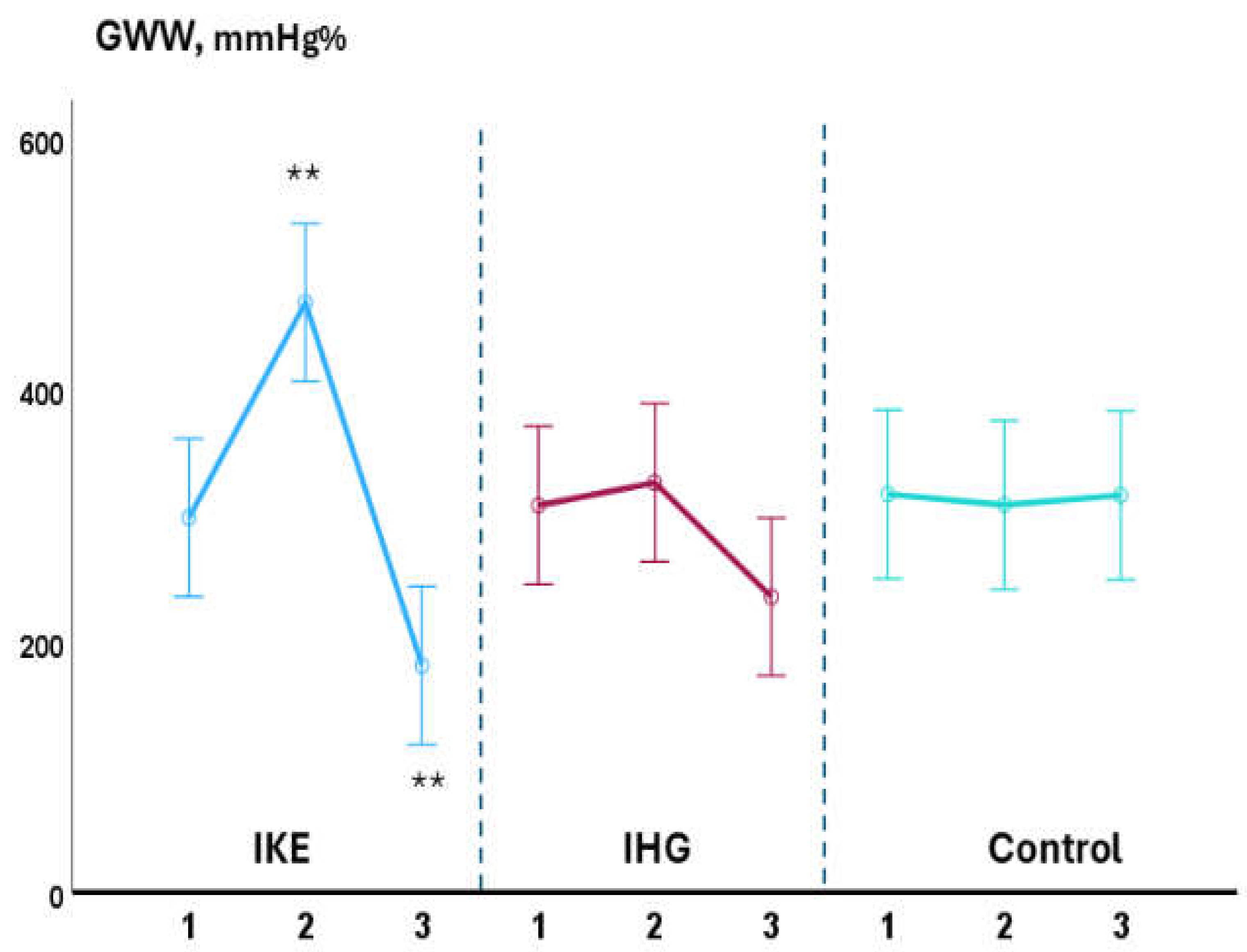

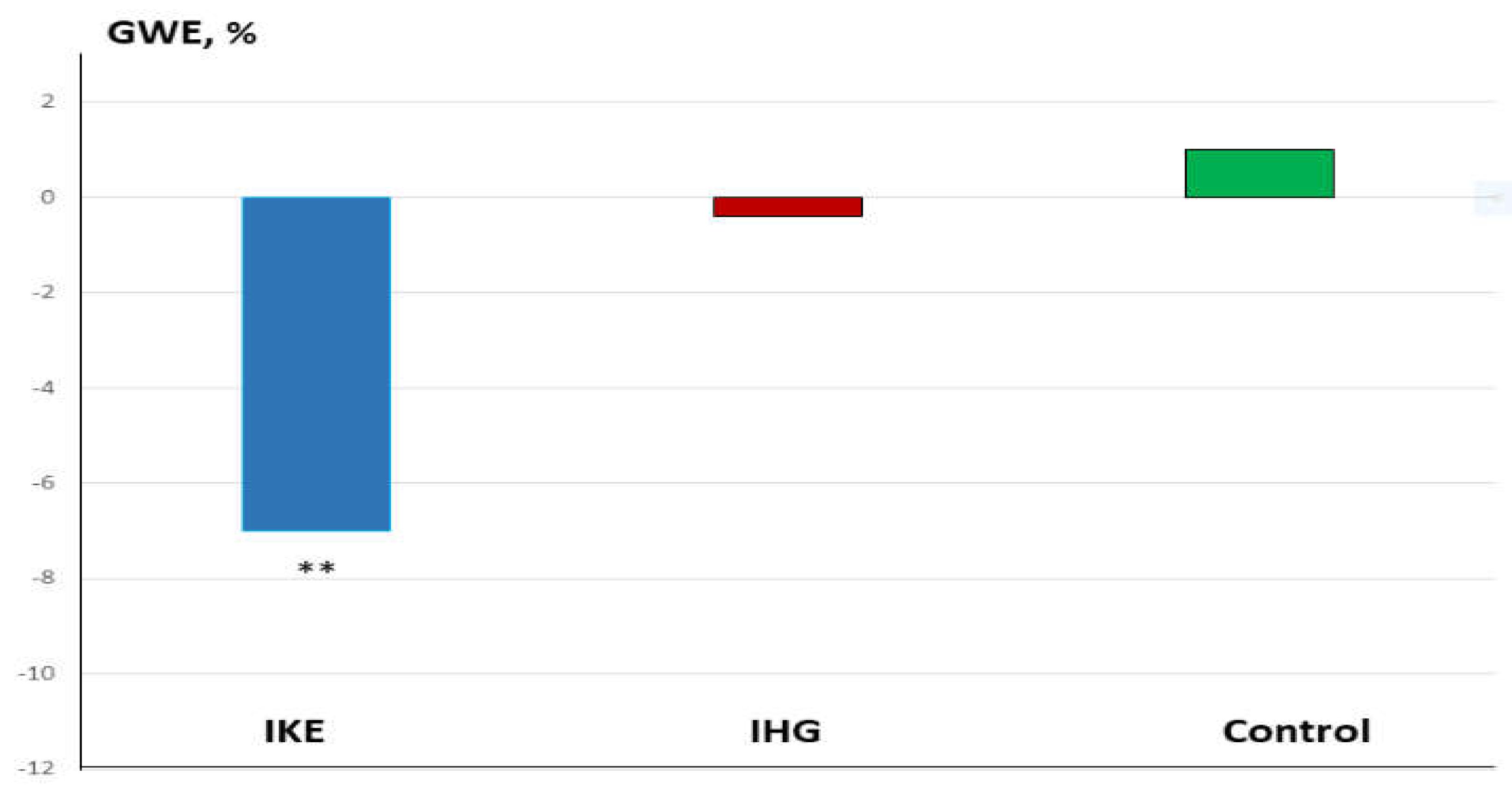

Background: Isometric exercise effectively reduces blood pressure (BP) but its effects on myocardial work have been poorly studied. In the present study we compared acute changes in myocardial work during two different isometric exercise, bilateral knee extension and handgrip in patients with hypertension and underlying ischemic heart disease (IHD). Methods: 48 stable, trained patients with hypertension and IHD were enrolled. They were randomly assigned to perform a single session of bilateral knee extension (IKE) or handgrip (IHG) or no exercise (control) with a 1:1:1 ratio. Both exercises were performed at 30% of maximal voluntary contraction and lasted three minutes. Echocardiography and BP measurements were performed at rest, during the exercise and after ten minutes of recovery. Results: both exercises were well tolerated, and no side effects occurred. During the exercise: systolic BP increased significantly in the IKE group compared to IHG and control (ANOVA p <0.001). LVGLS decreased significantly in IKE (-21%) compared IHG and control (ANOVA p 0.002). The global work index increased significantly in KE (+28%) compared to HG and control (ANOVA p 0.034). Global constructive work and wasted work increased significantly in the IKE compared to HG and control (ANOVA p 0.009 and <0.001 respectively). Global work efficiency decreased significantly in the IKE group (-8%) while remained unchanged in the IHG and controls (ANOVA p 0.002). Systolic BP increased significantly in the KE group and was unchanged in HG and control. Conclusion: myocardial work efficiency was impaired during isometric bilateral knee extension but not during handgrip. Handgrip evoked a limited hemodynamic response.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Echocardiography

2.4. Experimental Sessions:

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Intra-Groups Changes

3.2. Between-Groups Changes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Pescatello, L.S.; Buchner, D.M.; Jakicic, J.M.; Powell, K.E.; Kraus, W.E.; Bloodgood, B.; Campbell, W.W.; Dietz, S.; Dipietro, L.; George, S.M.; Macko, R.F.; McTiernan, A.; Pate, R.R.; Piercy, K.L. Physical Activity to Prevent and Treat Hypertension: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M.D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Gerdts, E.; Hanssen, H.; Harris, J.; Lauder, L.; McManus, R.J.; Molloy, G.J.; Rahimi, K.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Rossi, G.P.; Sandset, E.C.; Scheenaerts, B.; Staessen, J.A.; Uchmanowicz, I.; Volterrani, M.; Touyz, R.M. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2024, 45, 3912–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baffour-Awuah, B.; Pearson, M.J.; Dieberg, G.; Smart, N.A. Isometric Resistance Training to Manage Hypertension: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2023, 25, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.; De Caux, A.; Donaldson, J.; Wiles, J.; O’Driscoll, J. Isometric exercise versus high-intensity interval training for the management of blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2022, 56, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jae, S.Y.; Yoon, E.S.; Kim, H.J.; Cho, M.J.; Choo, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kunutsor, S.K. Isometric handgrip versus aerobic exercise: a randomized trial evaluating central and ambulatory blood pressure outcomes in older hypertensive participants. J Hypertens. 2025, 43, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, S. Evidence for exercise therapies including isometric handgrip training for hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.J.; Viana, J.L.; Cavalcante, S.L.; Oliveira, N.L.; Duarte, J.A.; Mota, J.; Oliveira, J.; Ribeiro, F. Physical activity in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Overview updated. World J Cardiol. 2016, 8, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, H.; Hayashi, T.; Shirahata, M. Ventricular systolic pressure-volume area as predictor of cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1981, 240, H39–H44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, P.; Nagle, F. Isometric exercise: cardiovascular responses in normal and cardiac populations. Cardiol Clin. 1987, 5, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijn, S.A.; Aly, M.F.; Terwee, C.B.; van Rossum, A.C.; Kamp, O. Three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography for automatic assessment of global and regional left ventricular function based on area strain. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011, 24, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, S.A.; Yamada, A.; Khandheria, B.K.; Speranza, V.; Benjamin, A.; Ischenko, M.; Platts, D.G.; Hamilton-Craig, C.R.; Haseler, L.; Burstow, D.; Chan, J. Use of three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography for quantitative assessment of global left ventricular function: a comparative study to three-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014, 27, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciapuoti, F.; Paoli, V.D.; Scognamiglio, A.; Caturano, M.; Cacciapuoti, F. Left Atrial Longitudinal Speckle Tracking Echocardiography in Healthy Aging Heart. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2015, 25, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandraffino, G.; Imbalzano, E.; Lo Gullo, A.; Zito, C.; Morace, C.; Cinquegrani, M.; Savarino, F.; Oreto, L.; Giuffrida, C.; Carerj, S.; Squadrito, G. Abnormal left ventricular global strain during exercise-test in young healthy smokers. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsythe, L.; George, K.; Oxborough, D. Speckle Tracking Echocardiography for the Assessment of the Athlete’s Heart: Is It Ready for Daily Practice? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2018, 20, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, T.; Bandera, F.; Generati, G.; Alfonzetti, E.; Bussadori, C.; Guazzi, M. Left Atrial Function Dynamics During Exercise in Heart Failure: Pathophysiological Implications on the Right Heart and Exercise Ventilation Inefficiency. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017, 10 Pt B, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, M.A. : Iellamo, F.; D’Antoni, V.; Gismondi, A.; Di Biasio, D.; Vadalà, S.; Marazzi, G.; Morsella, V.; Volterrani, M.; Caminiti, G. Acute Changes on Left Atrial Function during Incremental Exercise in Patients with Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Case-Control Study. J Pers Med. 2023, 13, 1272. [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi, G.; Carerj, S.; Di Bella, G.; Manganaro, R.; Pizzino, F.; Restelli, D.; Pelaggi, G.; Lofrumento, F.; Licordari, R.; Taverna, G.; Paradossi, U.; de Gregorio, C.; Micari, A.; Di Giannuario, G.; Zito, C. Clinical Applications of Myocardial Work in Echocardiography: A Comprehensive Review. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2024, 34, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; Kazi, D.S.; Kolte, D.; Kumbhani, D.J.; LoFaso, J.; Mahtta, D.; Mark, D.B.; Minissian, M.; Navar, A.M.; Patel, A.R.; Piano, M.R.; Rodriguez, F.; Talbot, A.W.; Taqueti, V.R.; Thomas, R.J.; van Diepen, S.; Wiggins, B.; Williams, M.S. Peer Review Committee Members. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2023, 148, e9–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F. 3rd; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; Marino, P.; Oh, J.K.; Popescu, B.A.; Waggoner, A.D. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016, 17, 1321–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.; Özden Tok, Ö.; Mitrousi, K.; Ikonomidis, I. Myocardial Work: Methodology and Clinical Applications. Diagnostics. 2021, 11, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flight, L.; Julious, S.A. Practical guide to sample size calculations: an introduction. Pharm Stat. 2016, 15, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caminiti, G.; Volterrani, M.; Iellamo, F.; Marazzi, G.; D’Antoni, V.; Calandri, C.; Vadalà, S.; Catena, M.; Di Biasio, D.; Manzi, V.; Morsella, V.; Perrone, M.A. Acute Changes in Myocardial Work during Isometric Exercise in Hypertensive Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease: A Case-Control Study. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont, A.; Sculthorpe, N.; Hough, J.; Unnithan, V.; Richards, J. Global and regional left ventricular circumferential strain during incremental cycling and isometric knee extension exercise. Echocardiography. 2018, 35, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Driscoll, J.M.; Edwards, J.J.; Wiles, J.D.; Taylor, K.A.; Leeson, P.; Sharma, R. Myocardial work and left ventricular mechanical adaptations following isometric exercise training in hypertensive patients. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2022, 122, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovithis, D.; Anifanti, M.; Koutlianos, N.; Teloudi, A.; Kouidi, E.; Deligiannis, A. Left Ventricular Diastolic Response to Isometric Handgrip Exercise in Physically Active and Sedentary Individuals. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022, 9, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, S.S.; Shah, S.J.; Thomas, J.D. A Test in Context: E/A and E/e’ to Assess Diastolic Dysfunction and LV Filling Pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carluccio, E.; Cameli, M.; Rossi, A.; Dini, F.L.; Biagioli, P.; Mengoni, A.; Jacoangeli, F.; Mandoli, G.E.; Pastore, M.C.; Maffeis, C.; Ambrosio, G. Left Atrial Strain in the Assessment of Diastolic Function in Heart Failure: A Machine Learning Approach. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023, 16, e014605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olher, R. dosR.; Bocalini, D.S.; Bacurau, R.F.; Rodriguez, D.; Figueira, A., Jr.; Pontes, F.L., Jr.; Navarro, F.; Simões, H.G.; Araujo, R.C.; Moraes, M.R. Isometric handgrip does not elicit cardiovascular overload or post-exercise hypotension in hypertensive older women. Clin Interv Aging. 2013, 8, 649–655. [Google Scholar]

- Coneglian, J.C.; Barcelos, G.T.; Bandeira, A.C.N.; Carvalho, A.C.A.; Correia, M.A.; Farah, B.Q.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; Gerage, A.M. Acute Blood Pressure Response to Different Types of Isometric Exercise: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2023, 24, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Sun, P.; Huang, L.; Hernandez, M.; Yu, H.; Jan, Y.K. Effects of the intensity, duration and muscle mass factors of isometric exercise on acute local muscle hemodynamic responses and systematic blood pressure regulation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1444598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounoupis, A.; Papadopoulos, S.; Galanis, N.; Dipla, K.; Zafeiridis, A. Are Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Stress Greater in Isometric or in Dynamic Resistance Exercise? Sports. 2020, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, H.T.; O’Driscoll, J.M.; Coleman, D.D.; Caux, A.; Wiles, J.D. Acute cardiac autonomic and haemodynamic responses to leg and arm isometric exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2022, 122, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, P.C.; Silva, M.R.; Lehnen, A.M.; Waclawovsky, G. Isometric handgrip training, but not a single session, reduces blood pressure in individuals with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2023, 37, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Assche, T.; Buys, R.; de Jaeger, M.; Coeckelberghs, E.; Cornelissen, V.A. One single bout of low-intensity isometric handgrip exercise reduces blood pressure in healthy pre- and hypertensive individuals. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2017, 57, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goessler, K.; Buys, R.; Cornelissen, V.A. Low-intensity isometric handgrip exercise has no transient effect on blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016, 10, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.R.; Vicente, J.B.; Melo, G.R.; Moraes, V.C.; Olher, R.R.; Sousa, I.C.; Peruchi, L.H.; Neves, R.V.; Rosa, T.S.; Ferreira, A.P.; Moraes, M.R. Acute Hypotension After Moderate-Intensity Handgrip Exercise in Hypertensive Elderly People. J Strength Cond Res. 2018, 32, 2971–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IKE (n= 16) |

IHG (n= 16) |

Control (n= 16) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.9±14.7 | 63.4±16.1 | 64.2±13.5 |

| Male/female, n | 14/2 | 14/1 | 7/1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.1±5.5 | 28.2±8.0 | 27.5±7.3 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.88±1.1 | 1.93±0.8 | 1.91±1.3 |

| Previous STEMI | 13 (81) | 11 (69) | 12 (75) |

| PCI, n (%) | 11 (69) | 10 (62) | 10(62) |

| CABG, n (%) | 8 (50) | 7 (44) | 9(56) |

| Physical activity (min/week) | 174 | 178 | 173 |

| HR, bpm | 66.8±13.6 | 63.5±11.4 | 65.2±8.2 |

| SBP, mmHg | 128.9±27.5 | 135.2±33.8 | 136.7±32.1 |

| DBP, mmHg | 81.6±9.2 | 80.9±12.4 | 81.8±1.3 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes, n(%) | 3 (19) | 2 (12) | 3 (19) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n(%) | 14 (87) | 15 (94) | 14 (87) |

| GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 3 (19) | 4 (25) | 2 (25) |

| Previous smoke habit, n (%) | 8 (50) | 10 (62) | 8 (50) |

| Echocardiography | |||

| LVEDV, ml | 140.4 ± 33,4 | 136.3 ± 32.4 | 137± 32.4 |

| LVESV, ml | 70.5 ± 11.7 | 67.0 ± 26.3 | 69.4±19.4 |

| LVEF, % | 50.3 ± 7.4 | 49.2± 8.2 | 50.3±11.4 |

| LVGLS, % | -12.4 ± 3.8 | -13.1 ± 3.5 | -12.9± 3.1 |

| GWI, % | 1150.5 ± 412.6 | ì284.9 ± 492.0 | 1198±331.6 |

| GCW, % | 1601.3 ± 491.8 | 1678 ± 558.3 | 1523±341.9 |

| GWW, % | 338.7 ± 127.7 | 345.2 ± 198.9 | 344.3± 166.5 |

| GWE, % | 82.5± 11.7 | 82.8 ± 9.7 | 81.5±13.1 |

| DT, ms | 208.7 ± 60.4 | 197.4 ± 37.5 | 211.7±44.5 |

| E, cm/s | 48.1 ± 9.0 | 50.6± 13.0 | 52.3± 12.3 |

| A, cm/s | 66.4 ± 16.1 | 67.3 ± 13.9 | 66.9 ± 14.1 |

| E/A ratio | 0.75 ± 0.16 | 0.75 ± 0.22 | 0.78± 0.13 |

| e’, cm/s | 5.9± 1.5 | 6.2±2.2 | 6.3±2.2 |

| E/e’ ratio | 8.1± 1.9 | 8.1 ± 2.6 | 8.3± 2.3 |

| TRV, m/s | 1.9± 0.4 | 2.1± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| PALS, % | 19.7 ± 8.5 | 21.4 ± 6.0 | 19.2± 6.0 |

| PACS, % | -13.9± 3.5 | -15.4 ± 3.5 | -15 7±4.3 |

| LAVI, ml/m2 | 31.6 ± 7.2 | 34.2 ± 10.3 | 32.72 ±9.1 |

| SV, ml | 70.3 ± 14.3 | 72.0± 14.4 | 69.3± 16.4 |

| CO, l/min | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 4.6± 1.0 | 4.5± 1.6 |

| Treatment | |||

| Anti-platelets agents, n (%) | 16 (100) | 16 (100) | 16 (100) |

| ACE-Is/ARBs, n (%) | 15 (94) | 16 (100) | 15 (94) |

| Betablockers, n (%) | 16 (100) | 16 (100) | 8 (100) |

| Tiazidics, n (%) | 4 (25) | 5 (31) | 5 (31) |

| CCAs, n (%) | 5 (31) | 6 (37) | 7 (44) |

| Ranolazine, n (%) | 3 (19) | 2 (12) | 2 (12) |

| Furosemide, n (%) | 1(6) | 2 (12) | - |

| Statins, n (%) | 16 (100) | 16 (100) | 16 (100) |

| Ezetimibe, n (%) | 13 (81) | 12 (75) | 13 (81) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).