1. Introduction

Honey bees (

Apis mellifera L.) as keystone pollinators in ecosystems, sustain the reproduction of over 80% of wild plant species globally, and enhance the yield of approximately 65% of crops worldwide [

1,

2]. Worker bees, the primary labor force of a colony, critically determine its survival through foraging efficiency: they maintain the colony’s metabolic homeostasis by continuously provisioning nectar and pollen [

3,

4], while simultaneously establishing a mutualistic “insect-plant” network via pollination services [

5,

6]. However, under survival pressures such as nectar scarcity or high colony density, some worker bees may violate intraspecific cooperation boundaries and exhibit robbing behavior—invading and robbing food resources from neighboring colonies [

7,

8] instead of engaging in routine foraging. Although this behavior transiently mitigates resource deficits for individual colonies, it markedly elevates inter-colony pathogen transmission risks. Moreover, it can trigger cascading effects, including queen balling and combat among worker bees. These events propagate rapidly across apiaries, leading to severe consequences such as colony collapse [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Floral resource limitation (particularly nectar scarcity) serves as the primary ecological factor triggering the dramatic increase in honey robbing [

12]. Current research on honey robbing predominantly focuses on its phenotypic characteristics and ecological drivers. Behavioral analyses reveal that robber bees exhibit an 8-fold increase in aggression and nearly a 2-fold enhancement in extranidal foraging activity compared to control groups [

13,

14]. Grume et al. observed a significant rise in guard bee numbers at the entrances of robbed colonies, with individuals identifying nestmates through odorant pheromones [

14]. Nevertheless, these studies remain largely confined to statistical descriptions of behavior-environment correlations, while scarcely addressing the molecular regulatory pathways underlying the robbing behavior.

In recent years, the application of proteomic technologies in insect behavioral research has made significant progress, providing powerful tools to decipher the molecular mechanisms underlying complex insect behaviors. These techniques have successfully uncovered the proteomic basis of

Apis mellifera L. caste differentiation [

15,

16], elucidated the brain protein reprogramming mechanisms during the behavioral transition from nursing to foraging in worker bees [

17], and identified olfactory-related protein networks involved in pollen collection decision-making [

18]. Furthermore, studies have clarified the molecular regulation of diapause behavior in

Galeruca daurica [

19], characterized energy metabolism features during migratory behavior in

Helicoverpa armigera [

20], and revealed egg-protection mechanisms in the oviposition behavior of

Bombyx mori Linnaeus [

21]. Notably, despite its widespread application in various insect behavior studies, a significant research gap remains regarding the molecular mechanisms of honey robbing. As an unconventional foraging strategy developed by honeybee colonies under resource competition pressure, the proteomic dynamics and regulatory networks underlying robbing behavior have yet to be systematically investigated.

Addressing this research gap, the present study employs Apis mellifera L. as experimental subjects to investigate the physiological costs of behavioral adaptation by comparing morphological traits (including tergite colorimetry, proboscis and appendage dimensions, etc.) and survival rates between robber bees and normal foragers. Furthermore, we implement Data-Independent Acquisition DIA mass spectrometry coupled with ultra-high-sensitivity detection to conduct Ultra-Fast quantitative proteomic sequencing of bee head samples. This integrated approach systematically deciphers key metabolic pathways and regulatory nodes associated with behavioral plasticity, ultimately elucidating the molecular proteomic regulatory network underlying the behavior.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Honey Bee Samples

This study employed Apis mellifera L. from standardized apiaries at the Institute of Apicultural Research, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, with all colonies confirmed pathogen-free before experimentation. Conducted during Beijing’s peak honey robbing season (August 2024, nectar and pollen scarcity period), the trial involved three strong and four weak colonies relocated to an open field. Newly emerged workers were marked daily (07:00-10:00) for five consecutive days (300 colored/300 white tags per colony/day), using seven distinct colors for colony differentiation. On day 23 post-marking, robbing was induced by applying high-concentration sugar syrup near weak colonies, with researchers subsequently capturing foreign-colored bees (robber bees) within robbed hives while intercepting white-tagged controls at source colony entrances during real-time monitoring.

2.2. Morphometric Measurements

The collected samples were fixed with 75% ethanol and stored at 4°C for subsequent use. Ten worker bees with no surface damage were randomly selected from both the experimental and control groups as a single sample set. Dissection was performed following Ruttner’s morphological taxonomy method for honeybees [

22]: the head, thorax abdomen, mouthparts, and legs were separated under a stereomicroscope (OLYMPUS SZX16, ×6.3). A stereo microscope (ZEISS Stemi 508, ×32) and a digital microscopy imaging system (LEICA DMS 300, equipped with a DFC450 CCD) were used to measure 23 morphological indicators, including proboscis length, width of tomentum on tergite, and appendage dimensions. To minimize operational errors, image acquisition was performed by a designated technician, and standardized analysis was conducted using Digimizer software (v6.02): after importing the original images with scale bars, the software was calibrated to perform three repeated measurements of key parameters (e.g., proboscis length and appendage dimensions), with the mean value taken. All data were exported to Excel 2021 for statistical analysis.

2.3. Survival Experiment

From both experimental and control group samples, 90 worker bees were randomly selected and equally distributed into three rearing cages per group. The custom-designed acrylic cages (150×100×80 mm³) featured precisely arranged 1.5 mm diameter ventilation holes (12 holes/cm² density) on both bottom and side panels, with two integrated 2 mL syringe ports on the upper surface. All experimental groups received continuous provision of 50% (w/v) sucrose solution under strictly controlled environmental conditions (30 ± 0.5°C, 60 ± 5% RH) maintained by a calibrated ESPEC PLC-450 environmental chamber. Daily maintenance procedures included 09:00 sucrose solution replacement, survival census recording, and immediate removal of deceased individuals upon verification. The experiment continued until complete natural mortality was achieved across all test groups.

2.4. Protein Extraction and Digestion

Protein extraction was conducted following established protocols [

18,

23]. Head samples from both robber bees and normal foragers (comprising four independent biological replicates per group, each replicate containing pooled head tissues from three worker bees) stored at -80°C were homogenized into powder using liquid nitrogen-precooled mortars. After adding ice-cold lysis buffer (8 M urea, 1 mM PMSF, 2 mM EDTA), samples underwent ice-bath sonication (5 min) followed by centrifugation (15,000 ×g, 10 min, 4°C; Eppendorf 5425R) to obtain supernatants. The total protein concentration was quantified using a BAC assay kit (manufactured by Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), with 100 μg protein aliquots subsequently processed through sequential treatments: reduction with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, 37°C, 30 min) and alkylation with 11 mM iodoacetamide (room temperature, dark, 15 min). Trypsin digestion (sequencing-grade, 37°C, 16 h) was terminated by acidification to pH 2.0 using 20% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), followed by C18 column desalting (Millipore, Billerica, MA), vacuum drying, and storage at -20°C for downstream applications.

2.5. LC-MS/MS Analysis

Peptide separation was achieved using a Vanquish Neo UHPLC system with mobile phases consisting of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile (B), utilizing a trap-elute configuration with a PepMap Neo Trap Cartridge (300 μm × 5 mm, 5 μm) and an analytical Easy-Spray™ PepMap™ Neo UHPLC column (150 μm × 15 cm, 2 μm) maintained at 55°C. Following injection of 200 ng sample at 2.5 μL/min, peptides were eluted using a linear gradient from 5% to 25% B over 6.9 min with 8 min column re-equilibration. Eluted peptides were directly ionized via a nano-electrospray source (2.0 kV spray voltage, 275°C capillary temperature) and analyzed by an Orbitrap Astral mass spectrometer in data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode with positive ion detection. Full MS scans were acquired at 240,000 resolution (at 200 m/z) across 380-980 m/z with 5 ms maximum injection time. MS/MS analysis employed 299 variable isolation windows (2 Th width) using higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) at 25% normalized collision energy with automatic gain control (AGC) target of 500%, 3 ms maximum injection time, and 30 s dynamic exclusion.

2.6. Data Analysis

Mass spectrometry raw data acquired from the Orbitrap Astral platform were analyzed using DIA-NN software (v1.8.1) in library-free mode, referencing the NCBI Apis mellifera L. proteome database (TaxID: 7460) with decoy database generation (1% false discovery rate threshold) and common contaminant filtering. Protein identification required ≥1 unique peptide with ≥ 2 matched spectra per protein. Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were identified using dual thresholds of |

log2(fold change,FC) | ≥ 0.58 (equivalent to

FC ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67) and

P ≤ 0.05, with differential patterns visualized through ggplot2 (v3.5.0)-generated volcano plots. Functional annotation of DEPs was performed using the Gene Ontology (GO) database (

http://geneontology.org/), while pathway analysis and enrichment were conducted via the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. Subcellular localization predictions were generated using WoLF PSORT software.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (v27.0), wherein inter-group comparisons of morphological characteristics were performed via independent samples T-tests with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05. Survival analyses employed Kaplan-Meier methodology with Log-rank testing for significance evaluation, while all data visualizations-including survival curves, column diagrams, and line graphs-were generated using GraphPad Prism (v27.0).

3. Results

3.1. Differential Morphological Characteristics

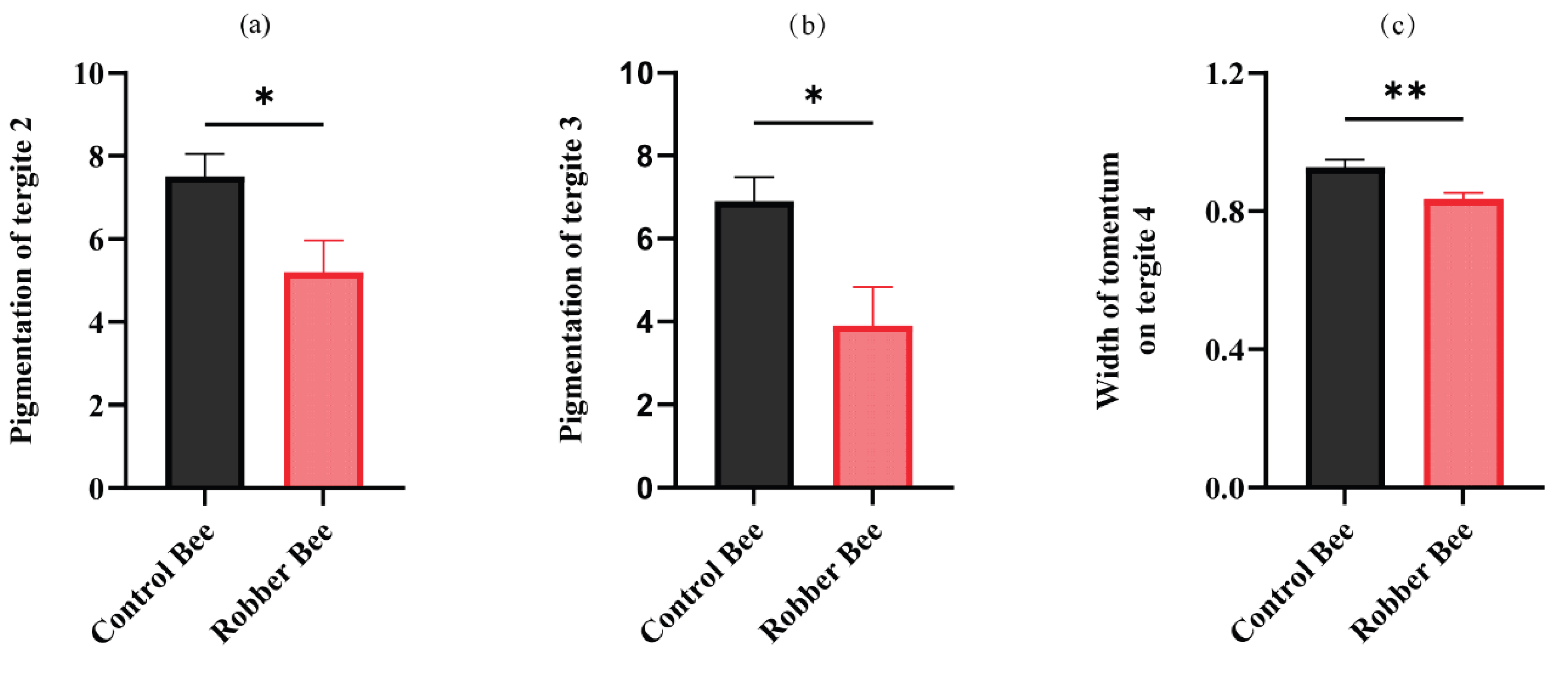

This study systematically compared morphological traits between robber bees and control bees (Additional file 1), revealing significant differences in only three parameters: tergite 2 pigmentation, tergite 3 pigmentation, and tomentum band width on tergite 4. Specifically, robber bees exhibited darker cuticular coloration, with significantly lower pigmentation values in tergite 2 (

Figure 1a) and tergite 3 (

Figure 1b) compared to control bees.

The results showed that the width of tomentum on tergite 4 in robber bees was significantly narrower than that in normal foragers (

Figure 1c), indicating a reduction in cuticular hair density. This morphological variation may be related to the specific behavioral activities of robber bees, where the decreased cuticular hair density adapts to their high-frequency aggressive fighting activities.

3.2. Survival Analysis

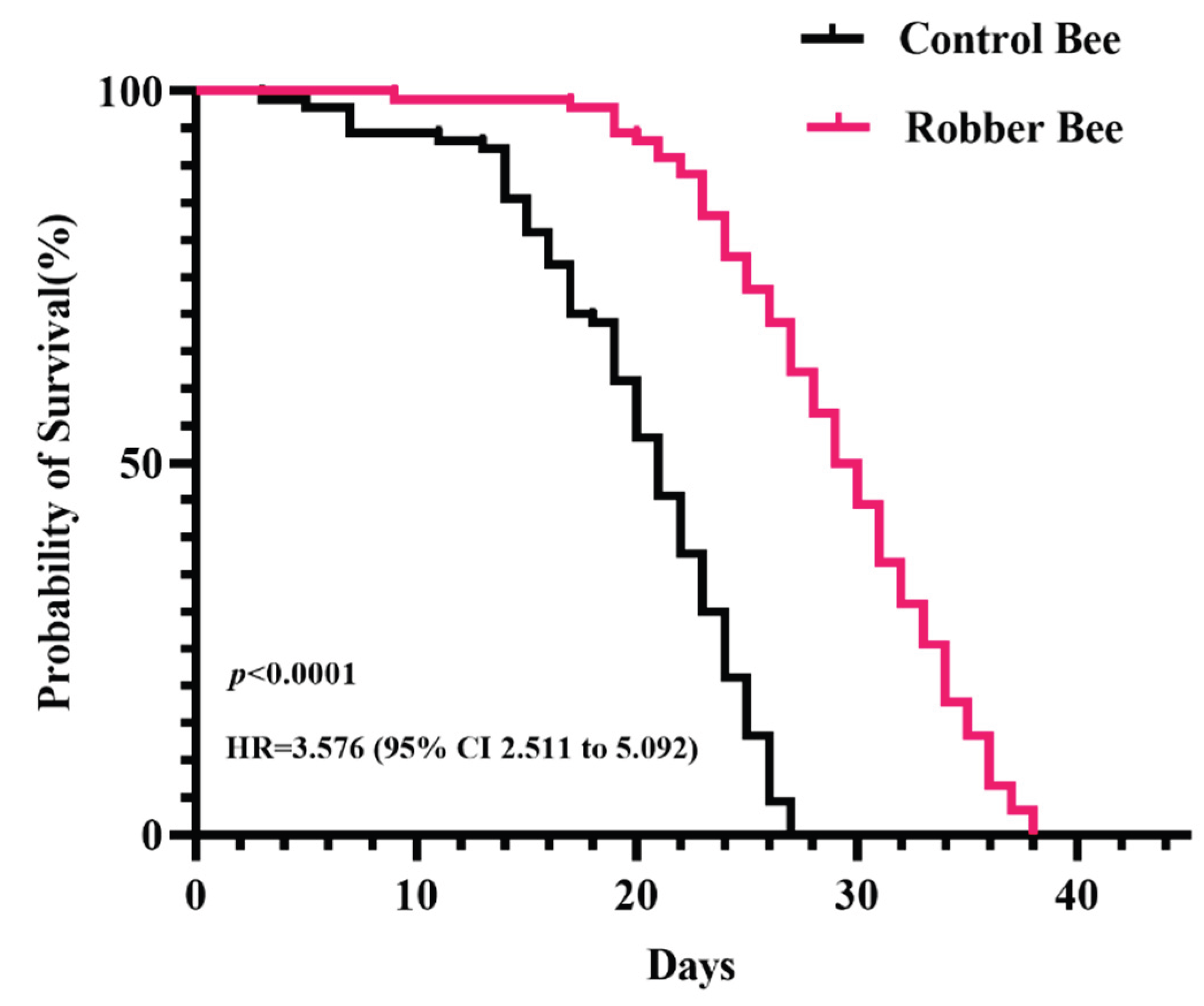

The survival curve of control bees displays a typical gradual decline pattern (

Figure 2), indicating that honey bees primarily die from natural aging under stable laboratory conditions. In contrast, the survival curve of robber bees shows a significantly accelerated decline rate, with a particularly steep drop after 14 days. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis combined with Log-Rank test confirmed an extremely significant difference between the two survival curves (

P < 0.0001). Further calculation of the Hazard Ratio (HR) revealed that robber bees have a 3.576 times higher mortality risk than control bees (95% CI: 2.511-5.092), quantitatively demonstrating the negative effect of robbing behavior on survival.

3.3. Identification of Proteins in the Heads

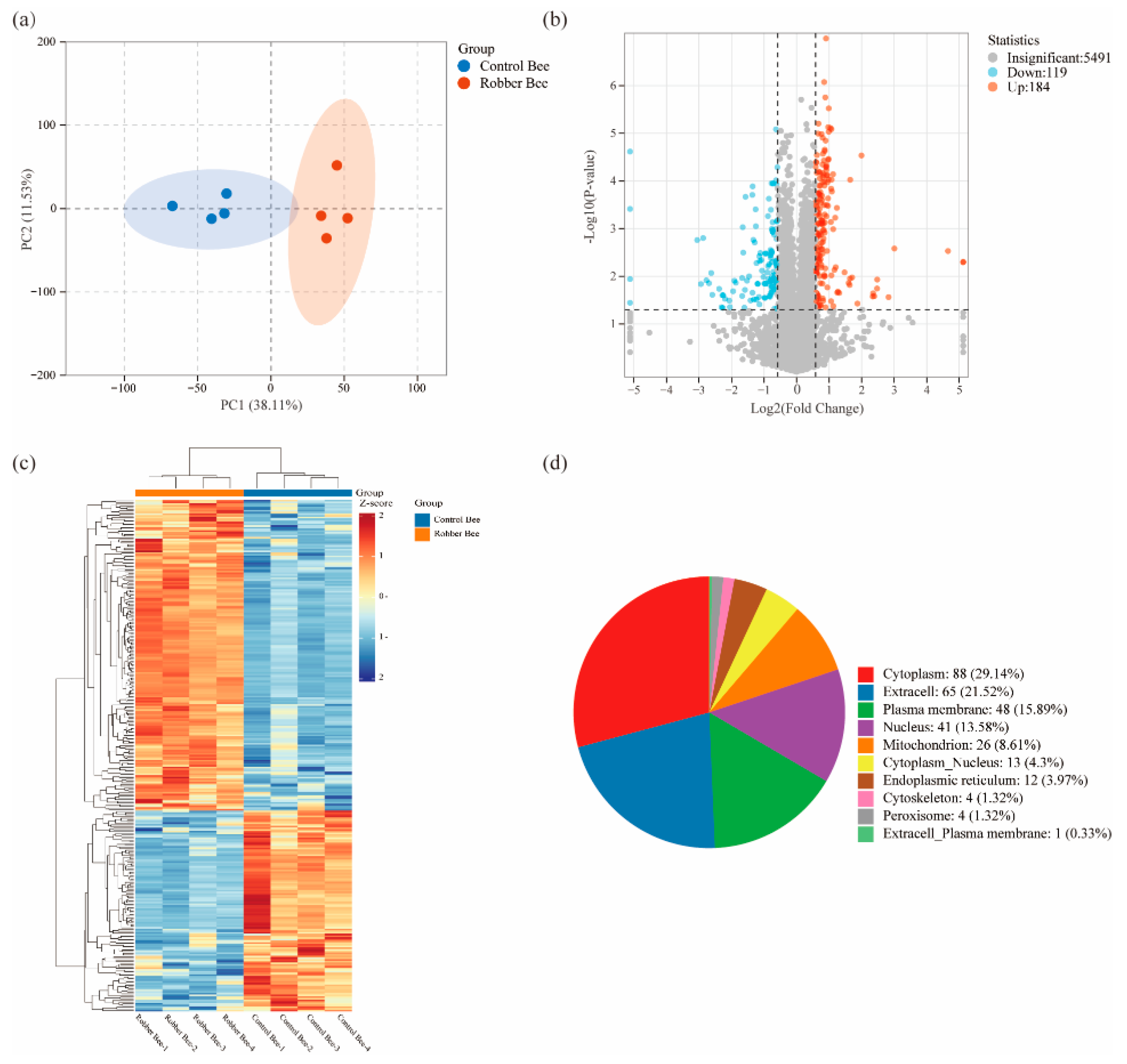

Proteomic sequencing of head proteins from robber bees and control bees identified 8,045 unique peptides corresponding to 5,218 proteins. PCA analysis showed clear separation between groups with tight clustering of quadruplicate biological replicates (

Figure 3a), confirming experimental reliability. Using thresholds of ≥1.5-fold upregulation or ≤0.67-fold downregulation,

P < 0.05, we identified 303 DEPs (184 upregulated, 119 downregulated;

Figure 3b, Additional file 2:

Table S1). Hierarchical clustering revealed that the DEPs between the two groups displayed distinct category-specific aggregation patterns (

Figure 3c). Subcellular localization analysis demonstrated compartment-specific enrichment of DEPs (

Figure 3d): cytoplasm (29.14%) contained metabolic enzyme complexes and signaling molecules; extracellular (21.52%) was enriched with secretory immune regulators; plasma membrane (15.89%) included transmembrane transporters and receptor kinases. The remaining 33.45% predominantly localized to mitochondria/nucleus, including flavin-containing monooxygenases(FMOs), glucose dehydrogenase (FAD), apyrase, heat shock protein 75 kDa (HSP75), and laccase-5.

3.4. GO and KEGG Pathway Analysis of DEPs

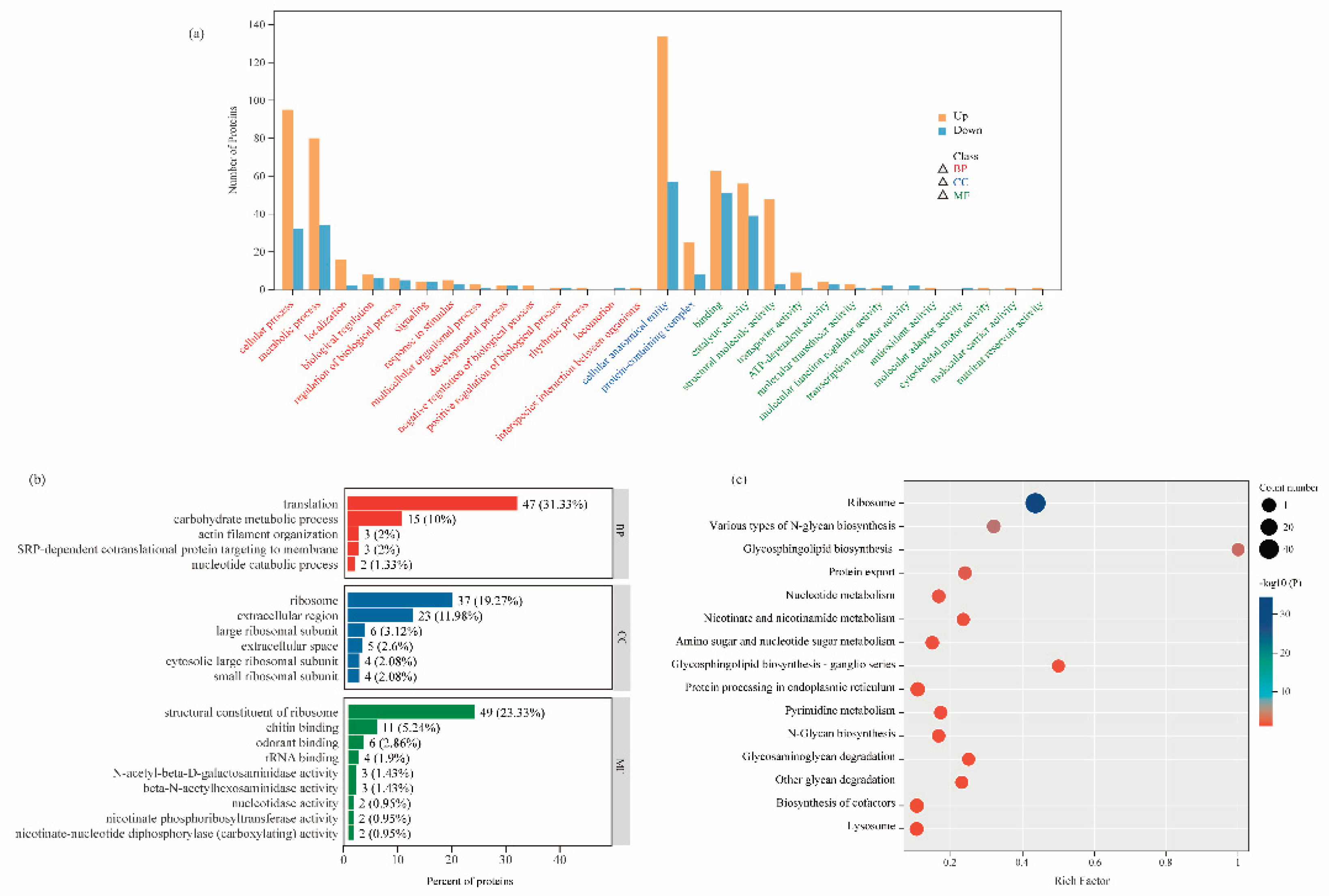

To further explore the biological significance of the DEPs, we systematically analyzed the functions of DEPs from three perspectives using the GO annotation system: Molecular Function (MF), Biological Process (BP), and Cellular Component (CC). We statistically evaluated the number of differentially expressed proteins annotated under all secondary GO terms, identifying a total of 29 significant GO terms (

Figure 4a). Among these, BP encompassed 14 terms (such as cellular process, metabolic process, localization, and biological regulation), CC included 2 terms (such as cellular anatomical entity and protein-containing complex), and MF comprised 13 terms (including binding, catalytic activity, structural molecule activity, and transporter activity).

To further investigate the functions of DEPs, we conducted GO enrichment analysis based on the GO annotation results (

Figure 4b, Additional file 2:

Table S2). In the BP, among the 303 proteins, 47 were involved in translation, 15 in carbohydrate metabolic process, 3 in actin filament organization, 3 in SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane, and 2 in nucleotide catabolic process. For CC, 37 proteins were associated with the ribosome, 6 with the large ribosomal subunit, 23 with the extracellular region, 4 with the cytosolic large ribosomal subunit, 4 with the small ribosomal subunit, and 5 with the extracellular space. In the MF category, 49 proteins were identified as structural constituents of the ribosome, 11 exhibited chitin binding, 6 showed odorant binding, 4 had rRNA binding, 2 possessed nucleotidase activity, and 2 displayed nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase activity.

To further elucidate the key biochemical metabolic and signal transduction pathways involving DEPs, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the 303 up-/down-regulated proteins using the KEGG database (

Figure 4c, Additional file 2:

Table S3). The results revealed that these proteins were primarily enriched in two functional categories: protein synthesis/processing and metabolic regulation. The ribosome pathway showed the most significant differential expression, followed closely by protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum and protein export pathways. These three pathways collectively form a complete “synthesis-processing-export” chain for proteins, all demonstrating significantly activated states in robber bees (with all related DEPs showing upregulated). Among metabolic pathways, notable enrichments were observed in: carbohydrate metabolism (N-glycan biosynthesis, glycosphingolipid biosynthesis, and amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism); nucleotide metabolism (pyrimidine metabolism and nucleotide metabolism); and cofactor metabolism (nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism and biosynthesis of cofactors). Particularly noteworthy are the pentose phosphate pathway and mTOR signaling pathway - although their enrichment did not reach the statistical significance threshold (Additional file 2:

Table S3), they may form a complex cooperative regulatory network through metabolite crossover and signal interaction. These specific metabolic pathway alterations likely reflect the unique metabolic remodeling that occurs in robber bees as an adaptation to their robbing behavior.

4. Discussion

4.1. Laccase Upregulation Darkens Robber Bees’ Tergite Color

Robber bees exhibit distinct morphological differences compared to control bees, with significantly lower chromaticity values on their pigmentation of tergite 2 and pigmentation of tergite 3 indicating darker body coloration and increased melanin deposition in the cuticle. Laccase, a multi-copper oxidase widely present in insects, not only oxidizes phenolic substances into corresponding quinones [

24] but also serves as a crucial sclerotization enzyme [

25]. Yamazaki et al. identified a phenol oxidase involved in pupal case hardening and pigmentation in

Drosophila virilis, later confirmed as laccase [

26]. Homologous laccases were also detected in the pupal cuticle of

Drosophila melanogaster [

27]. When Arakane et al. silenced the laccase gene in

Tribolium castaneum using RNAi, mutants displayed significant phenotypic defects: abnormal cuticle hardening accompanied by pigmentation disorders [

28,

29]. In our study, the upregulated expression of laccase-5 in robber bees correlated with their altered morphological chromaticity values, suggesting that robber bees may enhance cuticular pigmentation through laccase mediated sclerotization pathways, resulting in their distinctive body coloration compared to control bees.

4.2. Oxidative Stress and Immunosuppression Mediate the Shortened Lifespan of Robber Bees

The study revealed that robber bees exhibit a significantly shortened lifespan, with a mortality risk 3.576 times higher than that of normal foragers (

Figure 2). Integrated proteomic analysis provided preliminary insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying their accelerated aging. Firstly, the downregulation of HSP75 suggests impaired mitochondrial protein folding [

30], weakening cellular stress response and exacerbating oxidative damage accumulation. Additionally, reduced glutathione transferase (GST) activity indicates compromised clearance of peroxides and electrophilic substances, impairing the antioxidant defense system [

31]. Facing this oxidative crisis, robber bees activate a two-tiered defense mechanism: during the primary phase, they upregulate cytochrome P450 enzyme system (CYP450) and FMOs to enhance xenobiotic metabolism [

32,

33]; in the secondary phase, peroxiredoxin (Prx) and FAD are upregulated to strengthen antioxidant defenses [

34,

35]. This compensatory mechanism, however, requires sustained consumption of reducing equivalents such as NADPH. To meet this demand, robber bees activate nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism to boost NADPH supply. While this metabolic reprogramming temporarily mitigates oxidative stress-induced damage, long-term maintenance of this stress-responsive state not only depletes substantial energy reserves but also disrupts redox homeostasis. Studies have shown [

36,

37,

38] that such imbalance accelerates pro-apoptotic signaling and oxidative damage to biomolecules, thereby hastening the aging process. These findings offer novel molecular-level insights into the aging mechanisms of social insects under environmental stress.

Furthermore, immunity is another critical factor influencing the overall health and survival of honey bees [

39,

40]. Defense protein 3, an essential effector of innate immunity, plays a vital role in combating various pathogens including bacteria, fungi, and viruses [

41,

42]. Similarly, C-type lectin 5, a pattern recognition receptor from the C-type lectin family, specifically binds to carbohydrate structures on pathogen surfaces through calcium-dependent recognition mechanisms, playing a pivotal role in immune recognition and clearance [

43,

44]. This study demonstrates that the reduced expression of these proteins in robber bees impairs their ability to recognize and eliminate pathogens, significantly compromising their health and ultimately shortening their lifespan.

4.3. Metabolic and Proteomic Reprogramming in Honey Robbing Adaptation

The high-frequency foraging behavior of robber bees is often accompanied by intense aggressive activities [

14], and the sustained execution of such behaviors requires robust support from the organism’s metabolic system. Proteomic analysis revealed that robber bees establish a molecular foundation supporting their behavioral patterns through coordinated upregulation of both energy metabolism and protein synthesis/processing systems. This physiological strategy of “metabolic-synthetic co-enhancement” is primarily manifested in the following aspects.

In terms of energy metabolism, robber bees exhibit significantly enhanced expression of key enzymes involved in nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism (Nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase A0A7M7GAK0, A0A7M7R7E2, etc.), and nucleotide metabolism (Apyrase A0A7M7GSG4, Adenylate kinase-6 A0A7M7TF44, etc.), and the pentose phosphate pathway (FAD A0A7M7GJ80, A0A7M7RBJ1, etc.). The synergistic effects of these metabolic enzymes form an efficient energy supply network: in the nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism pathway, nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase (the key enzyme for NAD+ salvage synthesis) forms a substrate-dependent relationship with FAD from the pentose phosphate pathway, enhancing oxidative phosphorylation efficiency through the NAD+ recycling system [

45,

46]; in the nucleotide metabolism pathway, the apyrase, adenylate kinase, and protein 5NUC together construct a dynamic energy balance network that both prevents ATP surplus and ensures sufficient emergency energy supply [

47,

48].

Simultaneously, the protein synthesis system in robber bees demonstrates comprehensive enhancement, manifested by significant upregulation of 51 ribosomal proteins in the ribosome pathway, along with increased expression of Sec61α/β and signal peptidase, collectively establishing an efficient protein folding and secretion system [

49]. This enhanced system not only meets the synthetic demands for nutritional functional proteins (such as MRJP and VG) under high metabolic rates [

50], but also achieves dual improvements in protein folding quality control and export efficiency through coordinated upregulation of the protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum and protein export pathways. Notably, the activation of the mTOR signaling pathway (with 2 differentially expressed proteins upregulated) reveals the molecular switch mechanism through which robber bees regulate the coordination between energy metabolism and protein synthesis via the nutrient-sensing hub [

51,

52].

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first comparative proteomic analysis between robber bees and normal forager bees. The findings reveal that robber bees establish a molecular foundation supporting their robbing behavior through coordinated upregulation of energy metabolism pathways and protein synthesis/processing systems. However, while this “metabolic-synthetic co-enhancement” adaptation strategy provides short-term behavioral advantages, it comes at the cost of accumulated oxidative damage and downregulation of immune-related proteins, which likely constitute key molecular mechanisms underlying their shortened lifespan. Our results not only uncover the molecular basis of behavioral polymorphism in social insects, but also provide novel molecular evidence for understanding the physiological costs of behavioral adaptation in animals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Additional file 1: Table S1: The mean and standard deviation of morphological indicators for control bee and robber bee. Additional file 2: Table S1 - S3. Table S1: Expression and differential analysis of all DEPs. Table S2 :GO functional classification for DEGs. Table S3: KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for DEGs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and X.L.; methodology, X.W., X.L., Z.Y., and M.H.; software, X.W. and X.L.; formal analysis, X.W. and X.L. and Z.Y.; investigation, X.L., Z.Y., M.H. and X.C.; resources, X.L., Z.Y., and M.H.; data curation, X.W. ,X.L and X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.W., X.L., Z.L. and J.G.; visualization, X.W., X.L., and Y.Z.; supervision, Z.L., J.G. and Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z.. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was supported by the earmarked fund for China Agriculture Research System-Bee (CARS-44-KXJ17), and the Science and Technology Innovation Project of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-2024-IAR).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DTT |

Dithiothreitol |

| TFA |

Trifluoroacetic acid |

| DIA |

Data-independent acquisition |

| HCD |

Higher-energy collisional dissociation |

| AGC |

Automatic gain control |

| DEPs |

Differentially expressed proteins |

| FC |

Fold change |

| GO |

Gene Ontology |

| KEGG |

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genesand Genomes |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

| FMOs |

Flavin-containing monooxygenases |

| FAD |

Glucose dehydrogenase |

| HSP75 |

Heat shock protein75kDa |

| MF |

Molecular Function |

| BP |

Biological Process |

| CC |

Cellular Component |

| GST |

Glutathione transferase |

| CYP450 |

CytochromeP450enzymesystem |

| Prx |

Peroxiredoxin |

| MRJP |

Main royal jelly proteins |

| VG |

Vitellogenin |

References

- Halvorson, K.; Baumung, R.; Leroy, G.; Chen, C.; Boettcher, P. Protection of honeybees and other pollinators: one global study. Apidologie 2021, 52, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrol, D.P. Decline in Pollinators. Pollination Biology: Biodiversity Conservation and Agricultural Production, 2012; 545–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.R. Division of labor in honeybees: form, function, and proximate mechanisms. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2010, 64, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Kohlmaier, M.G. Nectar source profitability influences individual foraging preferences for pollen and pollen-foraging activity of honeybee colonies. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2019, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Malthankar, P.A.; Mathur, V. Insect-Plant Interactions: A Multilayered Relationship. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 2021, 114, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Elshafiey, E.H.; Shetaia, A.A.; Abd El-Wahed, A.A.; Algethami, A.F.; Musharraf, S.G.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Zhao, C.; Masry, S.H.D.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; et al. Overview of Bee Pollination and Its Economic Value for Crop Production. Insects 2021, 12, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan Willingham, J.K.; Ellis, J. Robbing Behavior in Honey Bees. EDIS 2021, ENY-163, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, J.B. The behaviour of robber honeybees. Behaviour 1954, 7, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuszewska, K.; Woyciechowski, M. Risky robbing is a job for short-lived and infected worker honeybees. Apidologie 2014, 45, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, D.T.; Seeley, T.D. Mite bombs or robber lures? The roles of drifting and robbing in transmission from collapsing honey bee colonies to their neighbors. Plos One 2019, 14, e0218392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindström, A.; Korpela, S.; Fries, I. Horizontal transmission of Paenibacillus larvae spores between honey bee (Apis mellifera)colonies through robbing. Apidologie 2008, 39, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittschof, C.C.; Nieh, J.C. Honey robbing: could human changes to the environment transform a rare foraging tactic into a maladaptive behavior? Curr Opin Insect Sci 2021, 45, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Z.G.; Wang, H.F.; Xu, B.H.; Guo, X.Q. The Wisdom of Honeybee Defenses Against Environmental Stresses. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Grume, G.J.; Biedenbender, S.P.; Rittschof, C.C.; Foraging, Q.; Robbing, S. Honey robbing causes coordinated changes in foraging and nest defence in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Animal Behaviour 2021, 173, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolschin, F.; Amdam, G.V. Plasticity and robustness of protein patterns during reversible development in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Anal Bioanal Chem 2007, 389, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttstedt, A.; Moritz, R.F.A.; Erler, S. Origin and function of the major royal jelly proteins of the honeybee (Apis mellifera) as members of the yellow gene family. Biol Rev 2014, 89, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Feng, M.; Ma, C.; Rueppell, O.; Li, J.K. Major royal jelly proteins influence the neurobiological regulation of the division of labor among honey bee workers. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 225, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Fu, B.C.; Qin, G.J.; Song, H.L.; Wu, W.Q.; Shao, Y.Q.; Altaye, S.Z.; Yu, L.S. Proteome analysis reveals a strong correlation between olfaction and pollen foraging preference in honeybees. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 121, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.Y.; Zhou, X.R.; Tan, Y.; Pang, B.P. Proteomic analysis of adult Galeruca daurica (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) at I) different stages during summer diapause. Comp Biochem Phys D 2019, 29, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Minter, M.; Homem, R.A.; Michaelson, L.V.; Venthur, H.; Lim, K.S.; Withers, A.; Xi, J.H.; Jones, C.M.; Zhou, J.J. Odorant binding proteins promote flight activity in the migratory insect, Helicoverpa armigera. Mol Ecol 2020, 29, 3795–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.M.; Wang, X.H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.P.; Chen, Q.M.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhao, P.; Xia, Q.Y. Proteome profiling reveals tissue-specific protein expression in male and female accessory glands of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruttner, F. Morphometric Analysis and Classification. In Biogeography and Taxonomy of Honeybees 1988, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Song, F.F.; Zhang, L.; Aleku, D.W.; Han, B.; Feng, M.; Li, J.K. Differential antennal proteome comparison of adult honeybee drone, worker and queen (Apis mellifera L.). Journal of Proteomics 2012, 75, 756–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janusz, G.; Pawlik, A.; Swiderska-Burek, U.; Polak, J.; Sulej, J.; Jarosz-Wilkolazka, A.; Paszczynski, A. Laccase Properties, Physiological Functions, and Evolution. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Seto, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Kurushima, H. Mini-review an insect-specific system for terrestrialization: Laccase-mediated cuticle formation. Insect Biochem Molec 2019, 108, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroko, I. Yamazaki. The cuticular phenoloxidase in Drosophila virilis. Journal of Insect Physiology 1969, 15, 2203–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, F.M. Phenoloxidases from larval cuticle of the sheepblowfly, Lucilia cuprina: characterization, developmental changes,and inhibition by antiphenoloxidase antibodies. Archives ofInsect Biochemistry and Physiology 1987, 5, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakane, Y.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Beeman, R.W.; Kanost, M.R.; Kramer, K.J. Laccase 2 is the phenoloxidase gene required for beetle cuticle tanning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2005, 102, 11337–11342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakane, Y.; Lomakin, J.; Beeman, R.W.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Gehrke, S.H.; Kanost, M.R.; Kramer, K.J. Molecular and functional analyses of amino acid decarboxylases involved in cuticle tanning in Tribolium castaneum. The Journal of biological chemistry 2009, 284, 16584–16594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.J.; Voloboueva, L.A.; Ouyang, Y.B.; Emery, J.F.; Giffard, R.G. Overexpression of mitochondrial Hsp70/Hsp75 in rat brain protects mitochondria, reduces oxidative stress, and protects from focal ischemia. J Cerebr Blood F Met 2009, 29, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.B.; Wang, C.Z.; Li, X.; Huang, T.B.; Li, F.; Wu, S.Y. Glutathione S-Transferase Contributes to the Resistance of Against Lambda-Cyhalothrin by Strengthening Its Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms. Arch Insect Biochem 2024, 117, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.; Hayward, A.; Buer, B.; Maiwald, F.; Nebelsiek, B.; Glaubitz, J.; Bass, C.; Nauen, R. Phylogenomic and functional characterization of an evolutionary conserved cytochrome P450-based insecticide detoxification mechanism in bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2022, 119, e2205850119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, W.X.; Liu, F.; Chen, X.B.; Li, H.; Xu, B.H. Characterization of an cytochrome P450 gene (AccCYP336A1) and its roles in oxidative stresses responses. Gene 2016, 584, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.N.; Gul, I.; Khosravi, Z.; Amarchi, J.I.; Ye, X.; Yu, L.; Siyuan, W.; Cui, H. Molecular characterization, immune functions and DNA protective effects of peroxiredoxin-1 gene in Antheraea pernyi. Molecular Immunology 2024, 170, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, J.; Ikeda, Y. Advances in our understanding of peroxiredoxin, a multifunctional, mammalian redox protein. Redox Rep 2002, 7, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone-Finstrom, M.; Li-Byarlay, H.; Huang, M.H.; Strand, M.K.; Rueppell, O.; Tarpy, D.R. Migratory management and environmental conditions affect lifespan and oxidative stress in honey bees. Sci Rep-Uk 2016, 6, 32023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgun, T.; Dayioglu, M.; Ozsoy, N. Pesticide and pathogen induced oxidative stress in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Mellifera 2020, 20, 32–52. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J.; Joshi, N.K. Impact of Biotic and Abiotic Stressors on Managed and Feral Bees. Insects 2019, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, N.; Corona, M.; Neumann, P.; Dainat, B. Overwintering Is Associated with Reduced Expression of Immune Genes and Higher Susceptibility to Virus Infection in Honey Bees. Plos One 2015, 10, e0129956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainat, B.; Evans, J.D.; Chen, Y.P.; Gauthier, L.; Neumann, P. Predictive Markers of Honey Bee Colony Collapse. Plos One 2012, 7, e32151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyasov, R.A.; Gaifullina, L.R.; Saltykova, E.S.; Poskryakov, A.V.; Nikolenko, A.G. Review of the Expression of Antimicrobial Peptide Defensin in Honey Bees Apis mellifera L. J Apic Sci 2012, 56, 115-124. J Apic Sci 2012, 56, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyasov, R.A.; Gaifullina, L.R.; Saltykova, E.S.; Poskryakov, A.V.; Nikolaenko, A.G. Defensins in the Honeybee Antiinfectious Protection. J Evol Biochem Phys+ 2013, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.X.; Zhang, B.X.; Liu, F.F.; Rao, X.J. Functional characterization of Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) C-type lectin 5. J Econ Entomol 2023, 116, 1862–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danihlík, J.; Aronstein, K.; Petrivalsky, M. Antimicrobial peptides: a key component of honey bee innate immunity Physiology, biochemistry, and chemical ecology. J Apicult Res 2015, 54, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amici, A.; Grolla, A.A.; Del Grosso, E.; Bellini, R.; Bianchi, M.; Travelli, C.; Garavaglia, S.; Sorci, L.; Raffaelli, N.; Ruggieri, S.; et al. Synthesis and Degradation of Adenosine 5′-Tetraphosphate by Nicotinamide and Nicotinate Phosphoribosyltransferases. Cell Chem Biol 2017, 24, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu, C.F.; Wu, H.C.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Sheng, Y.C.; Wan, X.R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Physiological Role of Nicotinamide Coenzyme I in Cellular Metabolism. In Biology of Nicotinamide Coenzymes: From Basic Science to Clinical Applications, Qin, Z.-H., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Noma, T. Dynamics of nucleotide metabolism as a supporter of life phenomena. J Med Investig 2005, 52, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegutkin, G.G. Enzymes involved in metabolism of extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides: Functional implications and measurement of activities. Crit Rev Biochem Mol 2014, 49, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genuth, N.R.; Barna, M. The Discovery of Ribosome Heterogeneity and Its Implications for Gene Regulation and Organismal Life. Mol Cell 2018, 71, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Heerman, M.C.; Evans, J.D.; Rose, R.; Li, W.F.; Rodriguez-Garcia, C.; DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Huang, S.K.; Li, Z.G.; et al. Pollen reverses decreased lifespan, altered nutritional metabolism and suppressed immunity in honey bees (Apis mellifera) treated with antibiotics. Journal of Experimental Biology 2019, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2020, 21, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.Q.; Hu, R.Y.; Li, N.K.; Li, N.N.; Wu, J.L.; Yu, H.M.; Tan, J.; Li, Z.H.; Xu, S.F. Autophagy Is Required to Sustain Increased Intestinal Cell Proliferation during Phenotypic Plasticity Changes in Honey Bee (Apis mellifera). Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).