Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Dual Pathways of Organic Waste Valorization: Composting and Anaerobic Digestion

1.2. Defining Digestate: A Product of Anaerobic Biochemistry

1.3. Filling the Knowledge Gap: Objectives of this Review

- Hypothesis 1 (Agronomic Performance): Digestate would function primarily as a fast-acting mineral N fertilizer, producing short-term crop yields comparable or superior to synthetic fertilizers, but with a higher risk of nutrient loss if not managed precisely.

- Hypothesis 2 (Soil Health Impact): Unlike compost, digestate's contribution to soil physical properties and the broader soil food web would be minimal or even negative in the short term, with any positive effects limited primarily to its solid, fibrous fraction.

- Hypothesis 3 (Feedstock Dependency): The agronomic and environmental outcomes of digestate application would be highly variable and critically dependent on the AD feedstock.

2. Agronomic Efficacy: Crop Yield and Quality Responses

2.1. Efficacy as a Mineral Fertilizer Substitute: A Synthesis of Yield Outcomes

2.2. Beyond Yield: Influence on Crop Quality and Nutritional Value

2.3. The Functional Dichotomy: Liquid vs. Solid Digestate Fractions and Crop-Specific Responses

2.4. Digestate in Soilless and Hydroponic Systems: Opportunities and Challenges

2.5. Applications in Controlled Environments: Greenhouse Horticulture

3. Impacts on Soil Health and Ecology

3.1. Impacts on Soil Physical Structure and Carbon Sequestration

3.2. Impacts on the Soil Food Web: From Microbes to Earthworms

3.3. Molecular-Level Impacts: Dissolved Organic Matter Dynamics

4. Environmental Risks and Mitigation Strategies

4.1. The Challenge of Nutrient Synchrony and Environmental Losses

4.2. Contaminant Fate: Heavy Metals and Emerging Risks

5. Integrated Management and Valorization Pathways

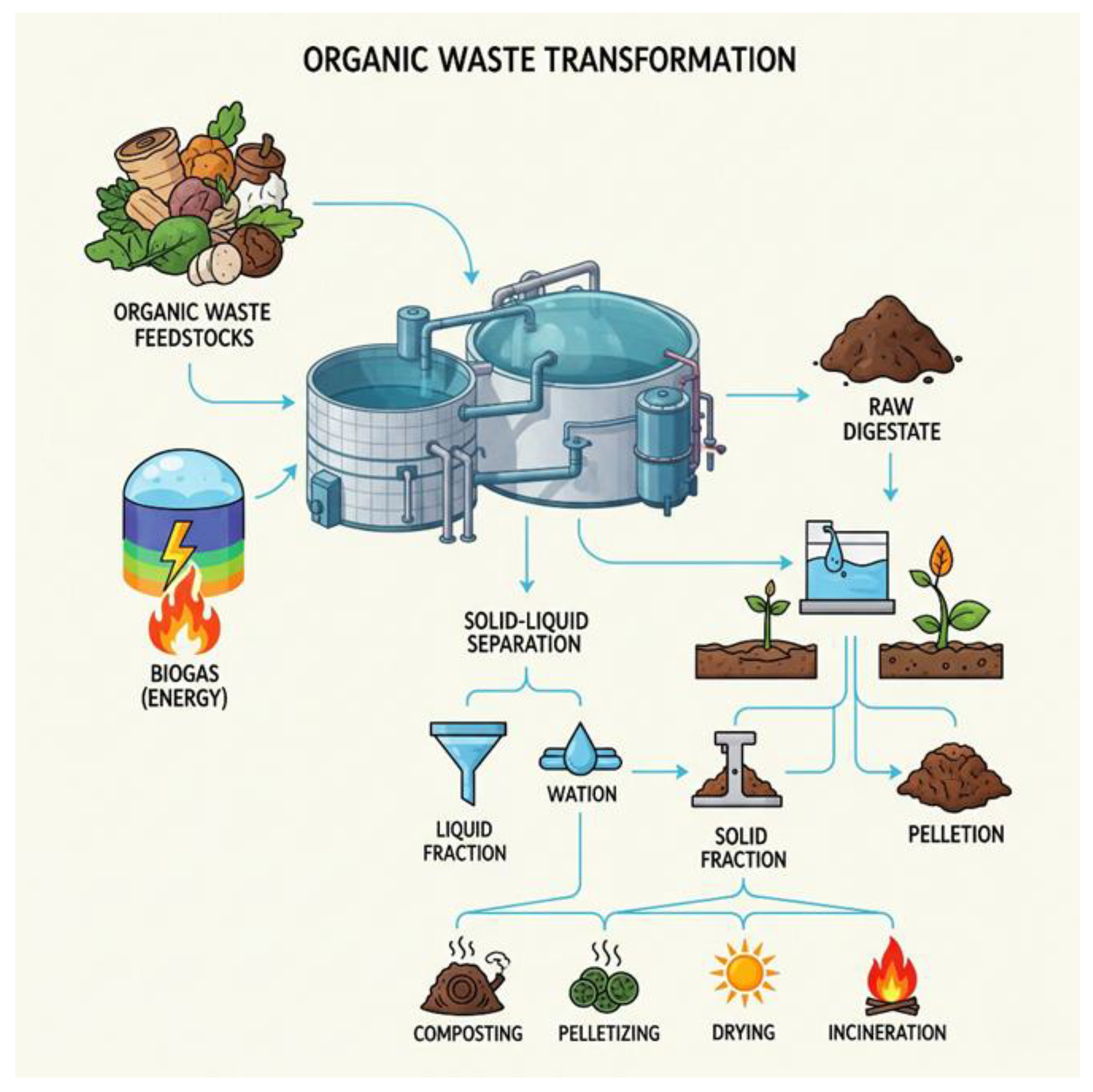

5.1. Digestate Processing and Conditioning for Enhanced Value

5.2. Novel Formulations: Synergies with Biochar and Other Amendments

5.3. Agroecosystem Integration: Intermediate Cropping and Carbon Dynamics

5.4. The Critical Role of Feedstock in Determining Digestate Quality

5.5. Economic and Policy Implications for Waste Valorization

5.6. Regional Perspectives: Digestate in Sub-Saharan African Agroecosystems

6. Conclusion and Future Research Directions

6.1. Synthesizing the Dilemma: A Framework of Trade-offs

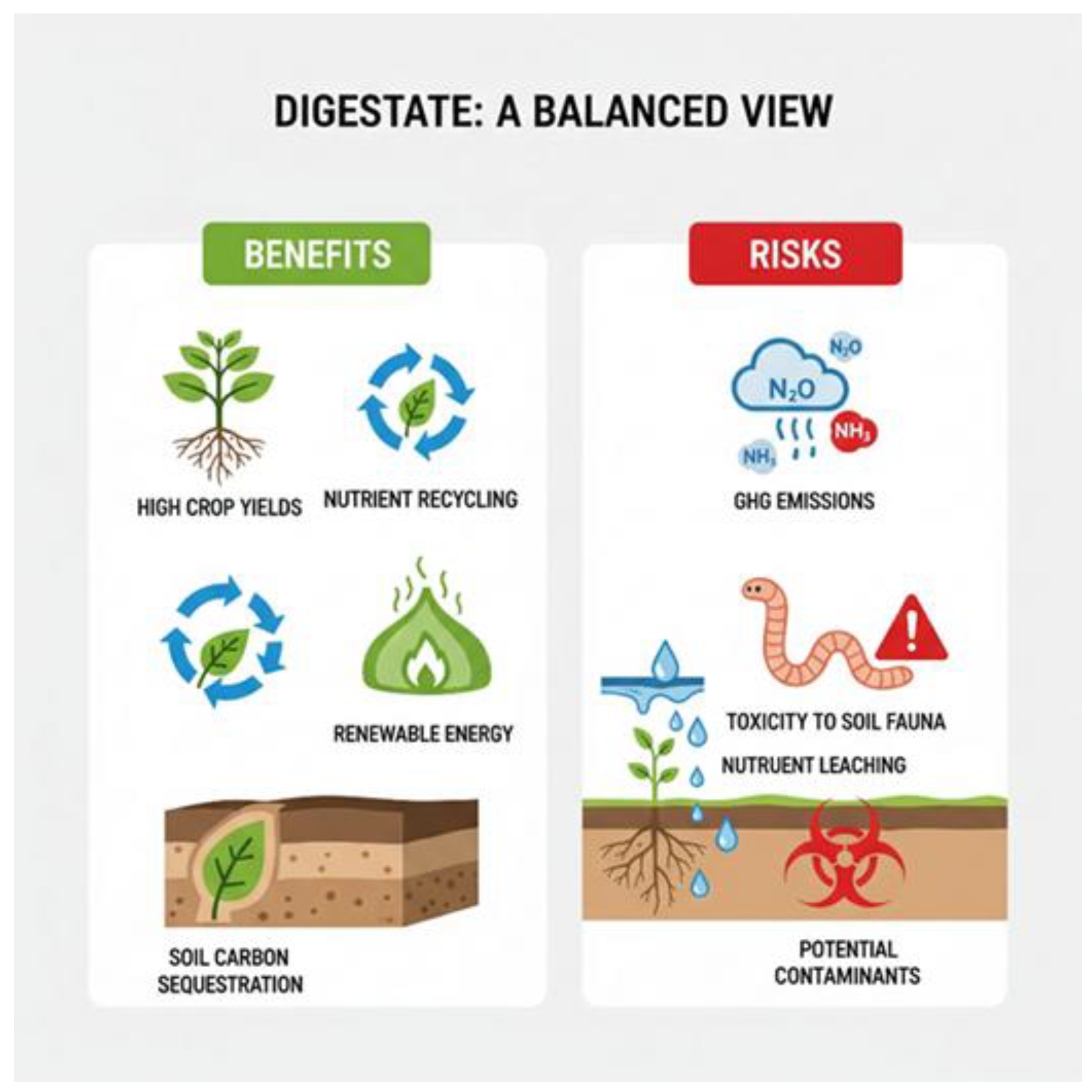

- Yield vs. Emissions: The high concentration of ammonium in liquid digestate provides a clear agronomic advantage, delivering readily available nitrogen for rapid crop growth. This very availability, however, presents a significant ecological dilemma: the same ammonium that fuels plant growth is also highly susceptible to volatilization and, as highlighted by Li et al. (2024), can lead to significantly higher nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions than mineral fertilizers, especially in moist, alkaline soils.

- Fast Nutrients vs. Soil Fauna: The immediate nutrient availability that benefits crops can be acutely toxic to essential soil fauna like earthworms and springtails, causing short-term population declines even if long-term benefits from increased organic matter eventually emerge.

- Energy Generation vs. Carbon Sequestration: Using crop residues for biogas production (energy) creates a carbon deficit in the soil that must be actively managed. This can be offset by returning the more stable, recalcitrant carbon in the digestate and cultivating intermediate crops, but it requires a conscious, system-level approach to balance energy goals with soil health objectives (Barrios Latorre et al., 2024).Figure 2. A conceptual diagram illustrating the central trade-offs of the digestate dilemma, balancing agronomic and energy benefits (high crop yields, nutrient recycling, renewable energy, soil carbon sequestration) against environmental and ecological risks (GHG emissions, toxicity to soil fauna, nutrient leaching, potential contaminants).Figure 2. A conceptual diagram illustrating the central trade-offs of the digestate dilemma, balancing agronomic and energy benefits (high crop yields, nutrient recycling, renewable energy, soil carbon sequestration) against environmental and ecological risks (GHG emissions, toxicity to soil fauna, nutrient leaching, potential contaminants).

6.2. Evaluation of Initial Hypotheses

- Hypothesis 1 (Agronomic Performance): Supported and Refined. The literature strongly supports the hypothesis that digestate functions as a fast-acting mineral N fertilizer, producing yields comparable or superior to synthetic fertilizers (Barzee et al., 2019; Haefele et al., 2022). The evidence also strongly supports the associated risk of nutrient loss if mismanaged. The hypothesis is refined by the clear evidence that integrated management (combining digestate with mineral fertilizers or other organic amendments) and advanced processing can enhance efficacy and mitigate risks (Zheng et al., 2016; Tiong et al., 2024).

- Hypothesis 2 (Soil Health Impact): Supported and Refined. The evidence confirms that digestate's impact on soil physical properties is indeed minimal compared to compost and is largely confined to its solid, fibrous fraction (Garg et al., 2005; Greenberg et al., 2019). However, this review refines the hypothesis by showing that digestate can be a powerful tool for restoring degraded soils (Cucina et al., 2025) and can contribute significantly to long-term SOC sequestration, especially when part of an integrated system (Barrios Latorre et al., 2024). The immediate impact on soil fauna can be negative due to toxicity (Natalio et al., 2021), reinforcing the idea that digestate is not an unequivocal soil health builder in the same way as compost.

- Hypothesis 3 (Feedstock Dependency): Strongly Supported. This hypothesis is perhaps the most unequivocally supported by the literature. The variability in outcomes, from yield response (Dahiya, 1986) to gaseous emissions (Li et al., 2024) and nutrient ratios (Rolka et al., 2024), is consistently and critically linked back to the source feedstock. This confirms that a "one-size-fits-all" approach to digestate is untenable.

6.3. Limitations of the Review and Key Lessons Learned

- Function Dictates Form: Digestate and compost are not interchangeable. Digestate is primarily a fast-acting fertilizer; compost is a slow-release fertilizer and soil conditioner. Management decisions must be based on this fundamental functional difference.

- Management is Key: The high concentration of available nutrients in digestate makes it a powerful but "unforgiving" tool. Precision in application timing, rate, and integration with other practices is critical to maximize agronomic benefit and minimize environmental harm.

- Feedstock is Destiny: The properties of any given digestate are overwhelmingly determined by what went into the digester. Sustainable use requires a move towards feedstock-specific management guidelines.

6.4. Actionable Research Questions for the Future

- To develop precision application guidelines: Under what specific soil types, moisture regimes, and application methods does digestate offer a verifiable net greenhouse gas benefit compared to mineral fertilizers, and how can this data be used to develop regional, evidence-based guidelines for farmers, particularly in under-researched regions like Sub-Saharan Africa?

- To quantify long-term soil restoration potential: What is the decadal-scale impact of repeated digestate application on the restoration of degraded tropical soils, specifically measuring changes in soil organic carbon stocks, physical properties, and the functional resilience of microbial communities?

- To optimize digestate valorization pathways: What are the most techno-economically viable and environmentally sound pathways for refining raw digestate into standardized, high-value bio-based fertilizer products, and what policy incentives are needed to support their development?

- To validate novel formulations in the field: What are the long-term agronomic and ecological effects of novel formulations, such as digestate-encapsulated biochar, under a range of real-world farming conditions?

6.5. Concluding Remarks

Authors' contributions

Funding

Availability of data and material

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

References

- Abd El-kader, E.; Rahman, A. Residual Effects of Different Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers on Spinach (Spinacia Oleracea L.) Plant Grown on Clay and Sandy Soils. J. Agric.&Env. Sci.Alex. Univ. Egypt 2007, 6, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ablieieva, I.; et al. Digestate biofertilization: A sustainable pathway to increase global soil C content. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubaker, J.; Risberg, K.; Pell, M. Biogas residues as fertilisers - Effects on wheat growth and soil microbial activities. Applied Energy 2012, 99, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovičs, A.; Poiša, L. The Effects of Digestate and Wood Ash Mixtures on the Productivity and Yield Quality of Winter Wheat. Environmental and Climate Technologies 2025, 1, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alburquerque, J.A.; de la Fuente, C.; Campoy, M.; Carrasco, L.; Nájera, I.; Baixauli, C.; Bernal, M.P. Agricultural use of digestate for horticultural crop production and improvement of soil properties. European Journal of Agronomy 2012, 43, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana Isabel, P.A.; Luis, R.B.; Juan, C.P.; Jerónimo, G.C. (2022). Analysis of the Digestate Obtained in Experiences in a Pilot Plant in Extremadura and Study of the Possible Effect Produced as an Organic Fertilizer in Pepper Plants. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Water Energy Food and Sustainability, Portalegre, Portugal, 10–12 May 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, pp. 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Arab, G.; McCartney, D. Benefits to decomposition rates when using digestate as compost co-feedstock: Part I – Focus on physicochemical parameters. Waste Management 2017, 68, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asp, H.; Bergstrand, K.-J.; Caspersen, S.; Hultberg, M. Anaerobic digestate as peat substitute and fertiliser in pot production of basil. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture 2022, 38, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldasso, V.; et al. Trace metal fate in soil after application of digestate originating from the anaerobic digestion of non-source-separated organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023, 10, 1007390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios Latorre, S.A.; Björnsson, L.; Prade, T. Managing Soil Carbon Sequestration: Assessing the Effects of Intermediate Crops, Crop Residue Removal, and Digestate Application on Swedish Arable Land. GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barłóg, P.; Hlisnikovský, L.; Kunzová, E. Effect of Digestate on Soil Organic Carbon and Plant-Available Nutrient Content Compared to Cattle Slurry and Mineral Fertilization. Agronomy 2020, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryga, A.; Połeć, B.; Klasa, A. The Effects of Soil Application of Digestate Enriched with P, K, Mg and B on Yield and Processing Value of Sugar Beets. Fermentation 2021, 7, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzee, T.J.; Edalati, A.; El-Mashad, H.; Wang, D.; Scow, K.; Zhang, R. Digestate Biofertilizers Support Similar or Higher Tomato Yields and Quality Than Mineral Fertilizer in a Subsurface Drip Fertigation System. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beni, C.; Servadio, P.; Marconi, S.; Neri, U.; Aromolo, R.; Diana, G. Anaerobic Digestate Administration: Effect on Soil Physical and Mechanical Behavior. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2012, 43, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.P.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Moral, R. Composting of animal manures and chemical criteria for compost maturity assessment. A review. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 5444–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhogal, A.; et al. (2016). DC-Agri; field experiments for quality digestate and compost in agriculture. WRAP.

- Brtnicky, M.; et al. Effect of digestates derived from the fermentation of maize-legume intercropped culture and maize monoculture application on soil properties and plant biomass production. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 2022, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.A.; et al. Co-composting of the solid fraction of anaerobic digestates, to obtain added-value materials for use in agriculture. Biomass and Bioenergy 2012, 43, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantigny, M.H.; et al. Yield and Nutrient Export of Grain Corn Fertilized with Raw and Treated Liquid Swine Manure. Agronomy Journal 2008, 100, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cui, Y.; Bai, F.; Wang, J. Effect of two biogas residues’ application on copper and zinc fractionation and release in different soils. Geoderma 2013, 192, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; et al. Decomposition of biogas residues in soil and their effects on microbial growth kinetics and enzyme activities. Biomass and Bioenergy 2012, 45, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Shearin, T.E.; Peet, M.M.; Willits, D.H. Utilization of treated swine wastewater for greenhouse tomato production. Water Science and Technology 2004, 50, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucina, M.; et al. Application of digestate from low-tech digesters for degraded soil restoration: Effects on soil fertility and carbon sequestration. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 967, 178854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, A.K. Biogas plant slurry as an alternative to chemical fertilizers. Energy Management 1986, 9, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahunsi, S.O.; Ogunrinola, G.A. Improving soil fertility and performance of tomato plant using the anaerobic digestate of tithonia diversifolia as Bio-fertilizer. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2018, 210, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didelot, A.-F.; Jaffrezic, A.; Morvan, T.; Liotaud, M.; Gaillard, F. ; Jardé; E Effects of digestate application, winter crop species and development on dissolved organic matter composition along the soil profile. Organic Geochemistry 2025, 200, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domene, X.; et al. Role of soil properties in sewage sludge toxicity to soil collembolans. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2010, 42, 1982–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; et al. Ecological and economic analysis of planting greenhouse cucumbers with anaerobic fermentation residues. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2011, 5, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, G.; et al. C and N turnover of fermented residues from biogas plants in soil in the presence of three different earthworm species (Lumbricus terrestris, Aporrectodea longa, Aporrectodea caliginosa). Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2008, 40, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Biogas Association (EBA). (2024). Exploring digestate's contribution to healthy soils.

- Feiz, R.; et al. Systems analysis of digestate primary processing techniques. Waste Management 2022, 150, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.N.; Pathak, H.; Das, D.K.; Tomar, R.K. Use of flyash and biogas slurry for improving wheat yield and physical properties of soil. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2005, 107, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Brandón, M.; Juárez, M.F.D.; Zangerle, M.; Insam, H. Effects of digestate on soil chemical and microbiological properties: A comparative study with compost and vermicompost. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2016, 302, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, I.; et al. The effect of biochar with biogas digestate or mineral fertilizer on fertility, aggregation and organic carbon content of a sandy soil: Results of a temperate field experiment. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2019, 182, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelak, A.; Bień, B.; Sławczyk, D.; Bień, J. Conditioning Biomass for Biogas Plants: Innovative Pre-Treatment and Digestate Valorization Techniques to Enhance Soil Health and Fertility. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefele, S.M.; et al. Anaerobic digestate as a fertiliser: A comparison of the nutritional quality and gaseous emissions of raw slurry, digestate and inorganic fertiliser. SSRN Electronic Journal 2022. [CrossRef]

- Holm-Nielsen, J.B.; Al Seadi, T.; Oleskowicz-Popiel, P. The future of anaerobic digestion and biogas utilization. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 5478–5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horta, C.; Carneiro, J.P. Use of Digestate as Organic Amendment and Source of Nitrogen to Vegetable Crops. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankauskienė, J.; Laužikė, K.; Kaupaitė, S. The Use of Anaerobic Digestate for Greenhouse Horticulture. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, A.; et al. Effects of digestate from anaerobically digested cattle slurry and plant materials on soil microbial community and emission of CO2 and N2O. Applied Soil Ecology 2013, 63, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuitunen, M.; H, H. Anaerobically digested poultry slaughterhouse wastes as fertiliser in agriculture. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 3507–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.E.; Steiman, M.W.; St Angelo, S.K. Biogas digestate as a renewable fertilizer: Effects of digestate application on crop growth and nutrient composition. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2021, 36, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levén, L.; et al. Phenols in anaerobic digestion processes and inhibition of ammonia oxidising bacteria (AOB) in soil. Science of The Total Environment 2006, 364, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; et al. Impact of organic fertilization by the digestate from by-product on growth, yield, and fruit quality of tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) and soil properties under greenhouse and field conditions. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 2023, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; et al. Digestate induces significantly higher N2O emission compared to urea under different soil properties and moisture. Environmental Research 2024, 241, 117617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Du, L.; Yang, Q. Biogas slurry added amino acids decreased nitrate concentrations of lettuce in sand culture. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B — Soil & Plant Science 2009, 59, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; et al. Nutrient supplementation increased growth and nitrate concentration of lettuce cultivated hydroponically with biogas slurry. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B — Soil & Plant Science 2011, 61, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loria, E.R.; Sawyer, J.E. Extractable Soil Phosphorus and Inorganic Nitrogen following Application of Raw and Anaerobically Digested Swine Manure. Agronomy Journal 2005, 97, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loria, E.R.; et al. Use of anaerobically digested swine manure as a nitrogen source in corn production. Agronomy Journal 2007, 99, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lošák, T.; et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of digestate and mineral fertilisers on yields and quality of kohlrabi. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 2011, 59, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makádi, M.; et al. Nutrient cycling by using residues of bioenergy production - Effects of biogas-digestate on plant and soil parameters. Cereal Research Communications 2008, 36 (Suppl. 5), 1807–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Maliki, M.; Ifijen, I.H.; Khan, M.E. Effect of Digestate from Rubber Processing Effluent on Soil Properties. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2020, 19, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarirambi, M.T.; et al. Effects of organic fertilizers on growth, yield, quality and sensory evaluation of red lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) Veneza Roxa. Journal of Agricultural Science 2010, 2, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; et al. Suppressive effect of anaerobically digested slurry on the root lesion nematode Pratylenchus penetrans and its potential mechanisms. Japanese Journal of Nematology 2007, 37, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinard, V.; et al. Short and long-term impacts of anaerobic digestate spreading on earthworms in cropped soils. Applied Soil Ecology 2021, 168, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, K.; Müller, T. Effects of anaerobic digestion on digestate nutrient availability and crop growth: A review. Engineering in Life Sciences 2012, 12, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Salguero, D.; Montenach, D.; Gilles, M.; Jean-Baptiste, V.; Sadet-Bourgeteau, S. Long-term effects of combining anaerobic digestate with other organic waste products on soil microbial communities. Frontiers in Microbiology 2025, 15, 1490034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabel, M.; et al. Effects of digestate fertilization on Sida hermaphrodita: Boosting biomass yields on marginal soils by increasing soil fertility. Biomass and Bioenergy 2017, 107, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalio, A.I. M.; et al. The effects of saline toxicity and food-based AD digestate on the earthworm Allolobophora chlorotica. Geoderma 2021, 393, 114972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyang'au, J.O.; Møller, H.B.; Sørensen, P. Nitrogen dynamics and carbon sequestration in soil following application of digestates from one- and two-step anaerobic digestion. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 851, 158177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlare, M.; Pell, M.; Svensson, K. Changes in soil chemical and microbiological properties during 4 years of application of various organic residues. Waste Management 2008, 28, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, M.; et al. Effects of Sewage Sludges and Composts on Soil Porosity and Aggregation. Journal of Environmental Quality 1981, 10, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuccio, M.R.; et al. Use of recalcitrant agriculture wastes to produce biogas and feasible biofertilizer. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2021, 7, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, V.; et al. Environmental impact of biogas: A short review of current knowledge. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A 2018, 53, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platen, R.; Glemnitz, M. Does digestate from biogas production benefit to the numbers of springtails (Insecta: Collembola) and mites (Arachnida: Acari)? Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 85, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommeresche, R.; Loes, A.K.; Torp, T. Effects of animal manure application on springtails (Collembola) in perennial ley. Applied Soil Ecology 2017, 110, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, V.; Vasileva, V.; Ljubičić, N.; Rakašćan, N.; Ikanović, J. Environment, Soil, and Digestate Interaction of Maize Silage and Biogas Production. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakascan, N.; et al. Effect of digestate from anaerobic digestion on Sorghum bicolor L. production and circular economy. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2021, 49, 12270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolka, E.; Wyszkowski, M.; Żołnowski, A.C.; Skorwider-Namiotko, A.; Szostek, R.; Wyżlic, K.; Borowski, M. Digestate from an Agricultural Biogas Plant as a Factor Shaping Soil Properties. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronga, D.; et al. Effects of solid and liquid digestate for hydroponic baby leaf lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) cultivation. Scientia Horticulturae 2019, 244, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.L.; et al. Assessing the impact of soil amendments made of processed biowaste digestate on soil macrofauna using two different earthworm species. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 2017, 63, 1939–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seswoya, R.; et al. Assessment of Digestate from Anaerobic Digestion of Fruit Vegetable Waste (FVW) as Potential Biofertilizer. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2025, 1453, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimon, T.; Kunzová, E.; Friedlová, M. The effect of digestate , cattle slurry and mineral fertilization on the winter wheat yield and soil quality parameters. 2015, 61, 522–527. [CrossRef]

- Stinner, W.; Möller, K.; Leithold, G. Effects of biogas digestion of clover/grass-leys, cover crops and crop residues on nitrogen cycle and crop yield in organic stockless farming systems. European Journal of Agronomy 2008, 29, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, M.; Ahrends, H.E.; Srivastava, A.K.; Sosulski, T. Anaerobic Digestate from Biogas Plants—Nuisance Waste or Valuable Product? Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, Y.W.; et al. Enhancing sustainable crop cultivation: The impact of renewable soil amendments and digestate fertilizer on crop growth and nutrient composition. Environmental Pollution 2024, 342, 123132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinuzzi, F.; et al. The fertilising potential of manure-based biogas fermentation residues: Pelleted vs. liquid digestate. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.J.; et al. Replacing inorganic fertilizer with anaerobic digestate may maintain agricultural productivity at less environmental cost. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2012, 175, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Application of biogas digestate with rice straw mitigates nitrate leaching potential and suppresses root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita). Agronomy 2019, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, P. Biogas production: Current state and perspectives. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2010, 85, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, S.; et al. Co-composting of digestate and garden waste with biochar: Effect on greenhouse gas production and fertilizer value of the matured compost. Environmental Technology 2023, 44, 4261–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester-Larsen, L.; Jensen, L.S.; Jensen, J.L.; Müller-Stöver, D.S. Effects of biobased fertilisers on soil physical, chemical and biological indicators-a one-year incubation study. Soil Research 2024, 62, SR23213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagüe, M.R.; Lobo, M.C. Liquid digestate from organic residues as fertilizer: Carbon fractions, phytotoxicity and microbiological analysis. Spanish Journal of Soil Science 2020, 10, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; et al. Effects of digestate-encapsulated biochar on plant growth, soil microbiome and nitrogen leaching. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 334, 117481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; et al. Animal based biogas digestate application frequency effects on growth and water-nitrogen use efficiency in tomato. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2019, 22, 748–756. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; et al. Effects of biogas slurry application on peanut yield, soil nutrients, carbon storage, and microbial activity in an Ultisol soil in southern China. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2016, 106, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title of the paper | Digestate Source | Plant/Organism | Observations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Effects of organic fertilizers on growth, yield, quality, and sensory evaluation of red lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) 'Veneza Roxa'" | Bounce back compost, Poultry manure & Cattle manure | Red lettuce & River sand soil | Chicken manure > Cattle manure > bounce back compost > synthetic chemical fertilizers showing higher values on the number of leaves, plant height, yield & mean leaf dry mass. | (Masarirambi et al., 2010) |

| Biogas Plant Slurry as an Alternative to Chemical Fertilizers | Biogas plant slurry | Wheat, Bajra, Mustard, Tomato, Cauliflower, Ladyfinger, Barseem, Guar | Substitution of N fertilizer through slurry reduced the yields, while higher yields were achieved by replacing the half and total N fertilizer in vegetables and fodders, respectively. | (Dahiya, 1986) |

| Digestate Biofertilizers Support Similar or Higher Tomato Yields and Quality Than Mineral Fertilizer in a Subsurface Drip Fertigation System | Digested food waste (FWC), Dairy manure-derived biofertilizers (DMP) | Tomato | Ultra-filtered DMP had the highest yield of red tomatoes (7.13 ton·ha−1) next to the concentrated food waste digestate biofertilizer (FWC), 6.26 ton·ha−1. The FWC tomatoes had greater total and soluble solids contents than synthetically fertilized tomatoes. |

(Barzee et al., 2019) |

| Anaerobic digestate as a fertiliser: a comparison of the nutritional quality and gaseous emissions... | Food waste digestate; Manure-based digestate | Wheat | Food-waste AD achieved higher yields than mineral fertilizer at the same N rate. Manure-based AD required slightly higher N rates to achieve yields equal to mineral fertilizer. |

(Haefele et al., 2022) |

| Anaerobic Digestate from Biogas Plants-Nuisance Waste or Valuable Product? | Digestate pellets (from whole digestate and solid fraction) | Maize | Unprocessed digestate and liquid fraction gave the highest yields. Pelletized forms acted as slow-release fertilizers with lower initial yields. | (Szymańska et al., 2022) |

| "Comparison of the effectiveness of digestate and mineral fertilizers on yields and quality of kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea, L.)" | Pig slurry and maize silage | Kohlrabi | Mineral fertilizer, 29.2% outperformed digestate treatment, 27.9% by 1.3% compared to Urea treatment. Reduction in NO3− concentration from 678 mg NO3−/kg fresh matter to 228 mg after digestate application. | (Lošák et al., 2011) |

| Improving soil fertility and performance of tomato plants using the anaerobic digestate of Tithonia diversifolia as Bio-fertilizer | Tithonia diversifolia (Mexican sunflower) shoot | Tomato plant | 1000 ml of digestate had the highest plant growth rate, followed by the 800 ml treatment. Plants remedied with chemical fertilizer showed equivocal plant height and leaf length increase in 400 ml treatments. | (Dahunsi & Ogunrinola, 2018) |

| Ecological and economic analysis of planting greenhouse cucumbers with anaerobic fermentation residues | Digestates produced from pig manure | Cucumber | 4.62% DM, 4.08% solids, and 29.05% reductive sugar increase, and 15.90% more yields, longer cucumbers with low curvature. 3.77 profit more than NPK. | (Duan et al., 2011) |

| "Effects of biogas slurry application on peanut yield, soil nutrients, carbon storage, and microbial activity in an Ultisol soil in southern China" | Digestate: a mixture of pig manure + urine | Ultisol peanut plants & red soil microorganisms | Peanut grain yields of BS-CF combinations 3588 Kg ha−1 and 20% higher than the Chem fertilizer. With increased soil microbial biomass C and N. | (Zheng et al., 2016) |

| The fertilizing potential of manure-based biogas fermentation residues: pelleted vs. Liquid digestate | Biogas plant residue | Maize, Cucumber & Soil | Decreases in micro-nutrient concentration in cucumber and maize leaves. The liquid portion at low doses increased the shoot fresh weight in cucumber. Contrariwise, the solid pellets increased fresh weight in maize at a high dose. | (Valentinuzzi et al., 2020) |

| Agricultural use of digestate for horticultural crop production and improvement of soil properties | Mixture of pig slurry, 1.0% sludge from a slaughterhouse, wastewater treatment plant & 6.5% biodiesel wastewaters | Watermelon, cauliflower & soil microorganisms | No significant effect on TOC. Positive effect on the yield of watermelon, but minimal effect compared to mineral fertilization for cauliflower. | (Alburquerque et al., 2012) |

| The effect of digestate, cattle slurry, and mineral fertilization on the winter wheat yield and soil quality parameters | Digestate, cattle slurry | Winter wheat | Digestate (9.88 t/ha) produced slightly higher grain yields than mineral fertilizer (9.80 t/ha) and cattle slurry (9.73 t/ha). | (Šimon et al., 2015) |

| Environment, Soil, and Digestate Interaction of Maize Silage and Biogas Production | Maize silage digestate | Maize for silage | Application of 50 t/ha digestate increased plant height and led to a 16% increase in biomass yield compared to the unfertilized control. | (Popović et al., 2024) |

| Residual Effects of Different Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers on Spinach... | Plant and animal residues | Spinach | Spinach yield was highest with a 50% mineral N + 50% organic N combination, particularly in clay soils. | (Abd El-kader & Rahman, 2007) |

| Yield and Nutrient Export of Grain Corn Fertilized with Raw and Treated Liquid Swine Manure | Liquid swine manure (raw and digested) | Corn grain | Both raw and digested manure increased corn grain yield similarly to inorganic fertilizer, but digestate application required careful management to match N availability. | (Chantigny et al., 2008) |

| Nutrient cycling by using residues of bioenergy production... | Digestate from livestock manure, plant residues | Soybean | Splitting digestate applications into multiple phases during the growing season was effective for meeting crop demand and increasing pod yield and protein content. | (Makádi et al., 2008) |

| Nutrient | % Partitioned to Liquid Fraction (LF) | % Partitioned to Solid Fraction (SF) | Key Implication | Ref. |

| Nitrogen (N) | >80% | <20% | LF is a potent, fast-acting N fertilizer. | (Szymańska et al., 2022) |

| Phosphorus (P) | <40% | >60% | SF is a P-rich soil conditioner. | (Szymańska et al., 2022) |

| Potassium (K) | ~87% | ~13% | LF is a rich source of readily available K. | (Szymańska et al., 2022) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | <30% | >70% | SF is enriched in Mg. | (Szymańska et al., 2022) |

| Title of the paper | Digestate Source | Plant/Organism | Observations | Ref. |

| "Effects of biobased fertilisers on soil physical, chemical and biological indicators" | Compost, digestate, various biobased fertilisers | Arenosol (sandy), Luvisol (clay-rich) | Compost-like digestate significantly increased water-holding capacity (WHC), especially in sandy soil. Digestate decreased clay dispersibility in Luvisol (improved structure) but increased it in Arenosol. | (Wester-Larsen et al., 2024) |

| Use of fly ash and biogas slurry for improving wheat yield and physical properties of soil. | cattle dung | , wheat & soil: sandy loam | Leaf area index, root length density, and grain yield were higher with biogas slurry compared to the control (unamended). It also reduced bulk density and boosted moisture retention capacity and sandy loam hydraulic conductivity. | (Garg et al., 2005) |

| Effects of digestate fertilization on Sida hermaphrodita: Boosting biomass yields on marginal soils by increasing soil fertility | maize silage | Maize, sand soil | Yields of 28 t ha−1 were obtained with NPK compared to the digestate. However, higher SOC from digestate with all soils and marginal substrate. | (Nabel et al., 2017) |

| "The effect of biochar with biogas digestate or mineral fertilizer on fertility, aggregation and organic carbon content of a sandy soil" | Liquid digestate from maize silage | Sandy soil | No effect of fertilization with liquid digestate on bulk density, aggregation, or CEC. It could be due to the relatively small amount of Organic Matter. | (Greenberg et al., 2019) |

| Effects of Sewage Sludges and Composts on Soil Porosity and Aggregation | Aerobic sludge, anaerobic sludge, various composts & manure. | Soil | General improvement in physical parameters like Aggregate Stability, Pore Size Distribution, water holding capacity, and Porosity of sandy loam soil comparable to manure. | (Pagliai et al., 1981) |

| Anaerobic Digestate Administration: Effect on Soil Physical and Mechanical Behavior | distiller's residue, farm residue compost, various organic fertilizers, anaerobic digestate | alluvial soil & winter lettuce | The macroporosity of the soil surface improved considerably (> 20%). Hydraulic conductivity values increased with digestate application. | (Beni et al., 2012) |

| Effect of Digestate on Soil Organic Carbon and Plant-Available Nutrient Content... | Cattle slurry, digestate | Arable soil | Digestate application increased soil organic carbon content more effectively than cattle slurry over a multi-year period. | (Barłóg et al., 2020) |

| Application of digestate from low-tech digesters for degraded soil restoration... | Pig slurry digestate | Degraded soil | Application of 40 Mg ha−1 increased TOC by 58% and improved soil fertility indices, demonstrating restorative potential. | (Cucina et al., 2025) |

| Effect of Digestate from Rubber Processing Effluent on Soil Properties | Rubber processing effluent digestate | Acidic, sandy soil | Significantly enhanced soil quality, increasing SOC, N, P, K, Ca, and Na levels. | (Maliki et al., 2020) |

| Title of the paper | Digestate Source | Plant/Organism | Observations | Ref. |

| Nitrogen dynamics and carbon sequestration in soil following application of digestates from one- and two-step anaerobic digestion. | Digestates from one- and two-step AD | Loamy sand soil | A secondary AD step increased net inorganic N release by 9-17% compared to a primary AD step, improving N fertilizer value. | (Nyang'au et al., 2022) |

| Changes in soil chemical and microbiological properties during 4 years of application of various organic residues | Liquid biogas residues, & sewage sludge | Soil microorganisms | Increased potential ammonia oxidation rate (PAO), nitrogen mineralization capacity (N-min), while microbiological activity proliferated. Biogas residue had more significant concentrations of mineral nitrogen and easily degradable carbon. | (Odlare et al., 2008) |

| Biogas residues as fertilizers: Effects on wheat growth and soil microbial activities | Large-scale municipal biogas plant residue; pig slurry | Wheat and soil microbes | Highest yields from pig slurry. Digestate increased PAO and NMC in soil compared with NPK. Mineralized N, 50-82 kg ha−1. | (Abubaker et al., 2012) |

| Effects of digestate on soil chemical and microbiological properties: A comparative study with compost and vermicompost | Biogas plant | Arable soil microbial life | Higher soil nitrification rate than manure in the short-term, with no observable surge in soil microbial biomass and activity. | (Gómez-Brandón et al., 2016) |

| Land application of organic waste - Effects on the soil ecosystem | Biogas residue; Household waste + restaurant waste, household waste+ ley crop, household waste | Soil microbiology, Oats and spring barley | Crop yields are almost as high as the mineral fertilizer NPS. Substrate-induced respiration, potential ammonium oxidation & nitrogen mineralization increased post-digestate and compost application. | (Odlare et al., 2011) |

| Phenols in anaerobic digestion processes and inhibition of ammonia-oxidising bacteria (AOB) in soil | Municipal solid waste, slaughterhouse waste, cattle manure, swine manure & industrial waste | Soil bacteria | Swine manure contained the highest Phenol amounts. All 5 phenols inhibited ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB). | (Levén et al., 2006) |

| Effects of digestate from anaerobically digested cattle slurry and plant materials on soil microbial community... | Cattle slurry and plant materials digestate | Soil microbial community | Digestate application caused a rapid burst of microbial activity (priming effect) fueled by labile carbon and ammonium. | (Johansen et al., 2013) |

| Decomposition of biogas residues in soil and their effects on microbial growth kinetics and enzyme activities | Biogas residues | Soil microbes | Solid fraction of digestate provided a food source for slower-growing fungi and Gram-positive bacteria, leading to a sustained increase in microbial biomass. | (Chen et al., 2012) |

| Organism Group | Digestate Source/Type | Key Observation | Ref. |

| Earthworms (Macro-fauna) | Food-based digestate | High mortality and biomass loss in surface-dwelling species (A. chlorotica), directly linked to ammonia and salt toxicity. | (Natalio et al., 2021) |

| Earthworms (Macro-fauna) | Digestate from agricultural/food industry wastes & municipal sludge | Deep-burrowing species (L. terrestris) were less affected and responded positively, but still suffered mortality if at the surface during application. | (Moinard et al., 2021) |

| Earthworms (Macro-fauna) | Digestate from source-segregated biowaste | Epigeic and endogeic species actively avoided digestate-amended soils. | (Ross et al., 2017) |

| Earthworms (Macro-fauna) | Fermented residues from biogas plants | Deep-burrowing earthworms showed positive responses to digestate as a food source, though surface application still posed a mortality risk. | (Ernst et al., 2008) |

| Springtails (Meso-fauna) | Animal manure | Reduction in surface-dwelling springtails shortly after liquid digestate application. | (Pommeresche et al., 2017) |

| Springtails (Meso-fauna) | Digestate from maize silage, rye silage, and cattle slurry | Long-term positive effect on abundance, likely due to increased soil moisture and microbial food sources. | (Platen and Glemnitz, 2016) |

| Nematodes (Meso-fauna) | Rice straw & digestate | Suppressive effect on root-knot nematodes in the short term. | (Wang et al., 2019) |

| Nematodes (Meso-fauna) | Anaerobically digested slurry of dairy manure | Short-term suppressive effect on root lesion nematodes, attributed to volatile fatty acids and ammonia. | (Min et al., 2007) |

| Collembolans (Meso-fauna) | Sewage sludge | High concentrations of salts and ammonium in sludge (similar to digestate) were toxic to soil collembolans. | (Domene et al., 2010) |

| Gas | Food-Waste Digestate | Manure-Based Digestate | Mineral Fertilizer | Key Implication | Ref. |

| Ammonia (NH3) | High (up to 17% of applied NH4-N lost in 5 days) | Moderate | Low | Digestates, especially from protein-rich feedstock, are a significant source of NH3 volatilization. | (Haefele et al., 2022) |

| Nitrous Oxide (N2O) | Low | Low | Highest | Digestate application can significantly reduce N2O emissions compared to synthetic N fertilizers. | (Haefele et al., 2022) |

| Methane (CH4) | Low | High (if digestion is incomplete) | Negligible | Inefficient digestion can lead to residual CH4 emissions upon land application. | (Haefele et al., 2022) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).