1. Introduction

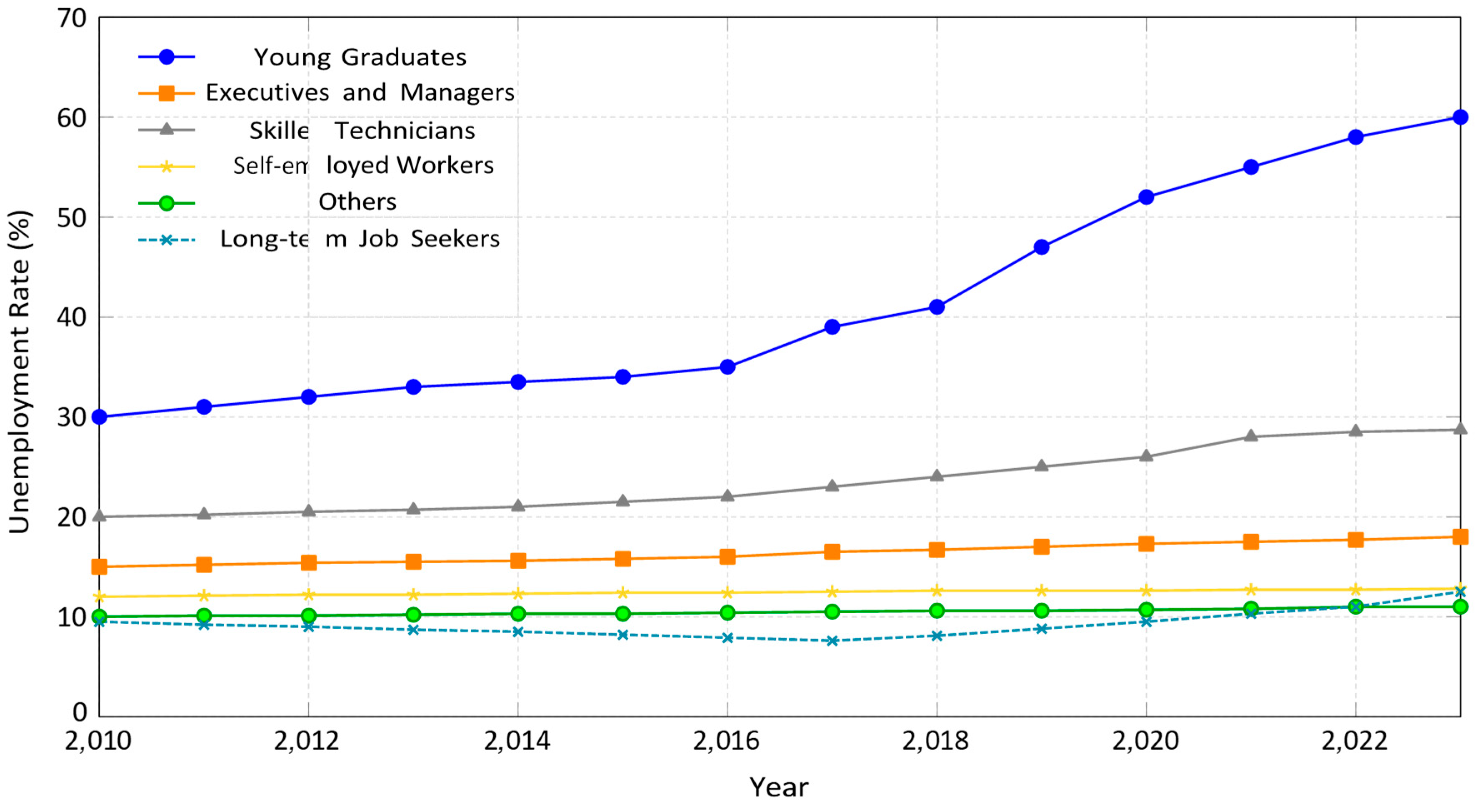

The Moroccan labor market is characterized by a high unemployment rate, particularly among young graduates, whose professional integration remains a major challenge (High Commission for Planning, 2023). This situation is explained by several structural factors, such as the low creation of formal jobs, the mismatch between education and business needs, and difficulties in accessing information on job opportunities (Benos & Karagiannis, 2018). In this context, digital recruitment platforms have emerged as an innovative solution to improve labor market efficiency by facilitating connections between employers and job seekers (Autor, 2019).

Digital platforms offer significant theoretical advantages: they help reduce job search costs, expand the reach of job postings, and optimize the selection process through advanced filtering tools (Kuhn & Mansour, 2014). By enhancing labor market transparency, they promise to improve the matching of supply and demand and accelerate young people’s entry into the workforce (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2020). However, despite their rise, the actual impact of these platforms on reducing unemployment in Morocco remains uncertain. Some studies show that their effectiveness heavily depends on the quality of job offers available, the qualification levels of users, and the adoption of digital tools by businesses (Deming & Noray, 2022).

Moreover, several studies suggest that recruitment platforms may reproduce or even amplify certain labor market inequalities, particularly by favoring candidates who already have work experience or specific skills sought by employers (Horton, 2017). Additionally, the rapid development of these tools raises challenges related to information verification, personal data protection, and the regulation of the digital labor market (Agrawal, Gans & Goldfarb, 2018).

In the Moroccan context, where youth unemployment is particularly high and the informal sector plays a predominant role, it is essential to assess to what extent these platforms can genuinely serve as an effective solution. This article provides an in-depth analysis of the impact of digital recruitment platforms on youth employment in Morocco. It is based on a review of existing research and examines the challenges and opportunities they present, putting their potential role in structuring the Moroccan labor market into perspective.

The objective is to determine whether these platforms constitute a viable response to professional integration issues or whether they merely reproduce, in a new form, the limitations of traditional re- cruitment mechanisms.

2. Literature Review

The impact of digital recruitment platforms on the labor market has been the subject of numerous studies in recent years. These works primarily focus on their role in reducing labor market frictions, their effectiveness in matching employers with job seekers, and the challenges they present. This section provides a literature review on these various aspects, with a particular focus on insights applicable to the Moroccan context.

Digital recruitment platforms have emerged as a major tool for facilitating professional integration and reducing labor market frictions. Since the early 2010s, the digitalization of job search and recruitment processes has profoundly transformed interactions between employers and candidates, making the market more dynamic but also raising questions about the actual effectiveness of these platforms. In many countries, especially in developing economies, these tools are seen as an innovative solution to improve labor market transparency and combat structural unemployment, particularly among young graduates. However, empirical findings on their impact are mixed, showing that these platforms are not a panacea; their effectiveness depends on several factors, including the quality of matching algorithms, access to technology, and employer adoption.

Early theoretical analyses of recruitment platforms rely on the classical literature on labor market frictions. Van Den Berg (1999) and, more recently, Chade, Eeckhout, and Smith (2017) explain that matching labor supply and demand is a costly process, characterized by information asymmetries and significant search costs. In this context, digital platforms are expected to reduce these frictions by improving the availability of information on job vacancies and candidate qualifications. Autor (2019) demonstrates that digital platforms have contributed to a better-structured labor market by reducing transaction costs and facilitating employer-worker connections. However, Kroft and Pope (2014) highlight that the effectiveness of online job searches is limited by issues such as congestion and mismatches between available skills and business needs.

From a more critical perspective, some authors have questioned the role of platforms as neutral and benevolent labor market actors. According to Srnicek (2017), digital platforms operate within a capitalist framework where data collection and exploitation constitute a major source of value creation. This logic can conflict with equity and social inclusion objectives, particularly if the recommendation algorithms used by platforms favor certain groups of candidates over others. Recent empirical studies have shown that some recruitment algorithms can reproduce gender or ethnic biases, thereby exacerbating existing labor market inequalities (Binns, 2018). While these findings are empirical, they underscore the importance of adequate regulation to ensure a fair and transparent use of matching technologies.

Even from a macroeconomic perspective, digital platforms can influence structural unemployment by altering labor market access conditions. According to Diamond (1982), structural unemployment arises from an imbalance between workers’ skills and job requirements. Matching platforms, by offering training and skill development services, can help mitigate this imbalance by aligning labor supply with market needs. However, as noted by Acemoglu and Restrepo (2018), this dynamic largely depends on platforms’ ability to anticipate market trends and offer relevant training content. Furthermore, access to platforms remains a crucial issue, particularly for vulnerable populations who may face barriers related to digital literacy or the cost of platform services. A central question in the literature concerns the impact of digital platforms on hiring rates and wages. Several recent studies have attempted to quantify these effects, yielding varied results depending on the context. Horton (2017) examines online labor platforms in the United States and finds that while they increase candidate visibility, they do not necessarily guarantee higher hiring rates or wages. Pallais (2014) shows that workers with a verifiable work history on these platforms benefit from a significant hiring advantage, highlighting an entry barrier for newcomers without prior experience.

In developing countries, where labor market constraints are more pronounced, the effects of digital platforms on employment are even more uncertain. Franklin (2018) analyzes the labor market in Ghana and shows that while digital platforms reduce job search costs, they do not address worker mobility issues or structural mismatches between supply and demand for skills. Similarly, Kelley, Ksoll, and Magruder (2023) find that in several African countries, online recruitment platforms have a limited impact on hiring rates due to low employer adoption and unequal access to technology among job seekers. In Morocco, the development of digital recruitment platforms is part of a gradual transformation of the labor market. The National Agency for the Promotion of Employment and Skills (ANAPEC) has implemented several initiatives aimed at digitizing employment services and promoting the use of digital platforms among young graduates. However, as Bennafla (2021) highlights, these initiatives face several challenges, including the mismatch between job postings on these platforms and employer expectations, as well as a lack of support for job seekers who may struggle with digital tools.

Another key factor determining the effectiveness of digital platforms lies in the quality of matching algorithms. Bastian, Riedl, and Bichler (2018) show that platforms using advanced recommendation algorithms have a higher rate of converting applications into hires. However, Stanton and Thomas (2016) point out that these algorithms can also reinforce existing inequalities by favoring certain profiles over others, thereby limiting their overall impact on unemployment reduction. As digital recruitment becomes a crucial issue for employment policies, several studies emphasize the importance of supporting job seekers in using digital platforms. Wheeler et al. (2022) demonstrate that training programs on digital tools significantly enhance job search effectiveness and improve participants’ hiring rates. This finding is particularly relevant in the Moroccan context, where access to digital skills remains uneven across different population groups and regions.

At the same time, a frequently overlooked aspect in the literature concerns the evolution of companies’ recruitment practices in response to the rise of digital platforms. Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020) show that companies adopting these tools tend to expand their talent pool and favor more standardized selection processes, which can have implications for the diversity of recruited profiles. However, McKenzie (2024) reminds us that employer adoption of these platforms remains limited in many contexts, mainly due to a lack of trust in the reliability of online information and difficulties in assessing candidates’ skills without physical interactions.

3. Labor Market and the Evolution of Digital Recruitment Plat- Forms in MOROCCO

3.1. Evolution of Activity and Employment Rates

Between 2014 and 2024, Morocco experienced a significant rise in the unemployment rate, increasing from 16.2% in 2014 to 21.4% in 2024. This surge has been particularly noticeable among youth and women, highlighting persistent structural challenges in integrating these groups into the labor market.

Meanwhile, the activity rate — which measures the percentage of the working-age population that is either employed or actively seeking employment — showed mixed dynamics. In 2024, it nearly stagnated at 43.5% compared to 43.6% in 2023. This overall stagnation masks divergent trends based on area of residence:

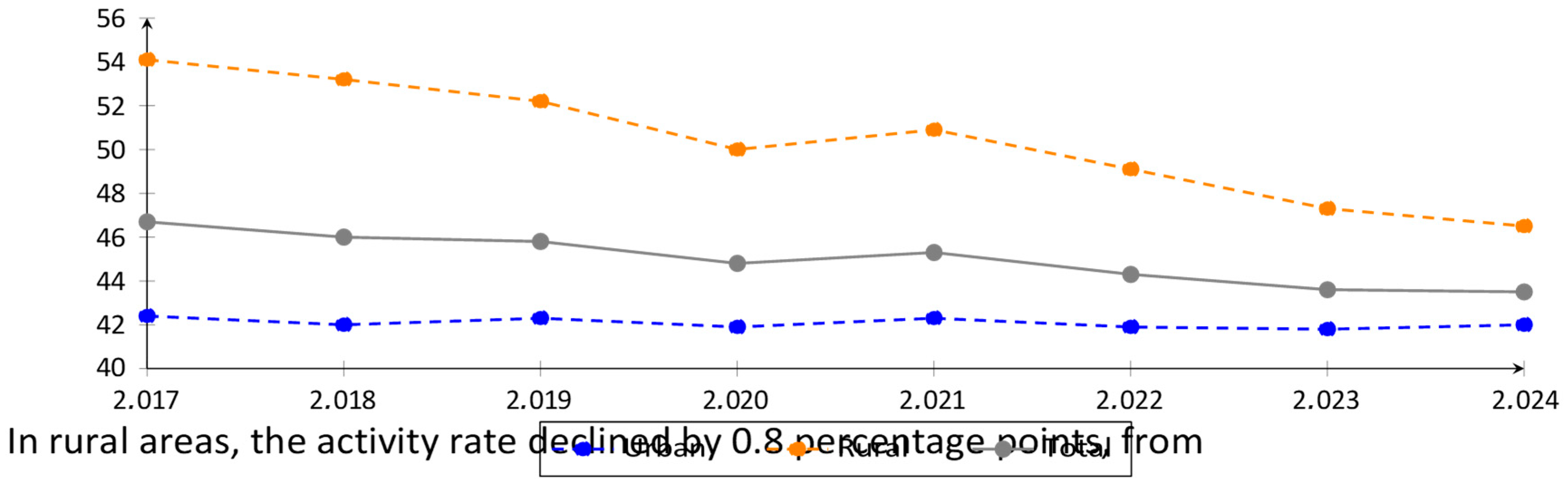

Figure 1.

Evolution of the activity rate since 2017 (in %).

Figure 1.

Evolution of the activity rate since 2017 (in %).

In rural areas, the activity rate declined by 0.8 percentage points, from 47.3% to 46.5%, reflecting potentially lower job opportunities or discouragement from job searching due to structural barriers. In urban areas, there was a slight increase of 0.2 points, from 41.8% to 42%, possibly due to new employment initiatives or informal job growth. In another perspective, women’s activity rate increased slightly by 0.1 point to 19.1%, showing a marginal improvement in female participation despite longstanding barriers. And in another way, men’s activity rate decreased by 0.4 point, settling at 68.6%, suggesting a potential saturation in male-dominated sectors or broader economic shifts.

In terms of employment, 2024 saw a slight national decrease in the employment rate from 38% to 37.7%, reflecting a loss of labor absorption capacity in the economy. Rural areas witnessed a notable decline of 1 point (from 44.3% to 43.3%), possibly due to adverse conditions in agriculture or reduced seasonal employment. Urban areas recorded a marginal rise of 0.1 point (from 34.8% to 34.9%), hinting at a slight uptick in service sector employment.

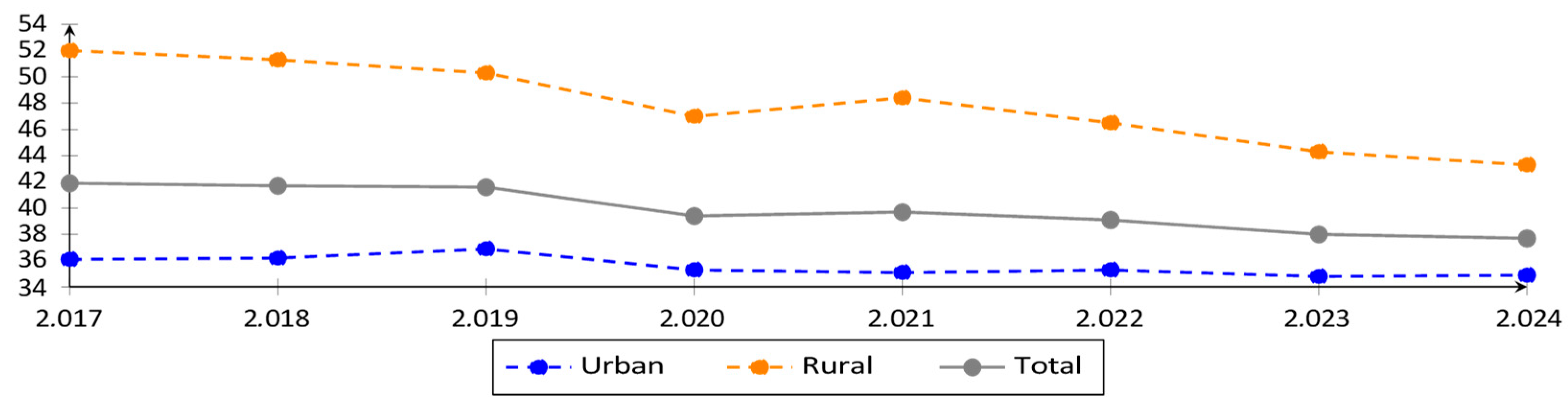

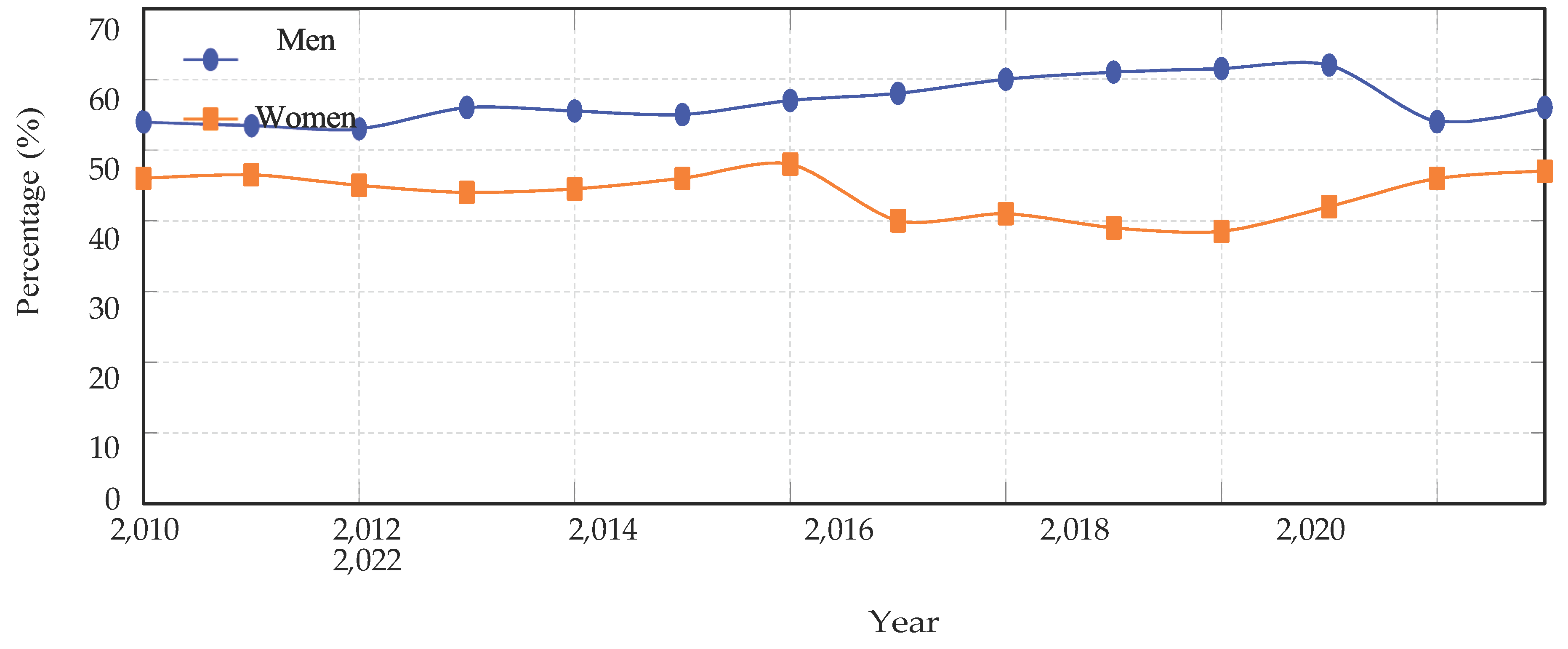

Figure 2.

Evolution of the employment rate since 2017 (in %).

Figure 2.

Evolution of the employment rate since 2017 (in %).

By gender, men’s employment rate dropped by 0.4 point to 68.6%, mirroring the broader downturn in economic opportunities for the male labor force, while women’s employment rate fell by 0.2 point to 19.1%, reinforcing concerns over persistent underemployment and exclusion. These shifts reflect complex labor market dynamics, with particular vulnerabilities in rural areas and among men, while urban and female employment showed slight improvements. The mixed performance underlines the need for targeted policy interventions.

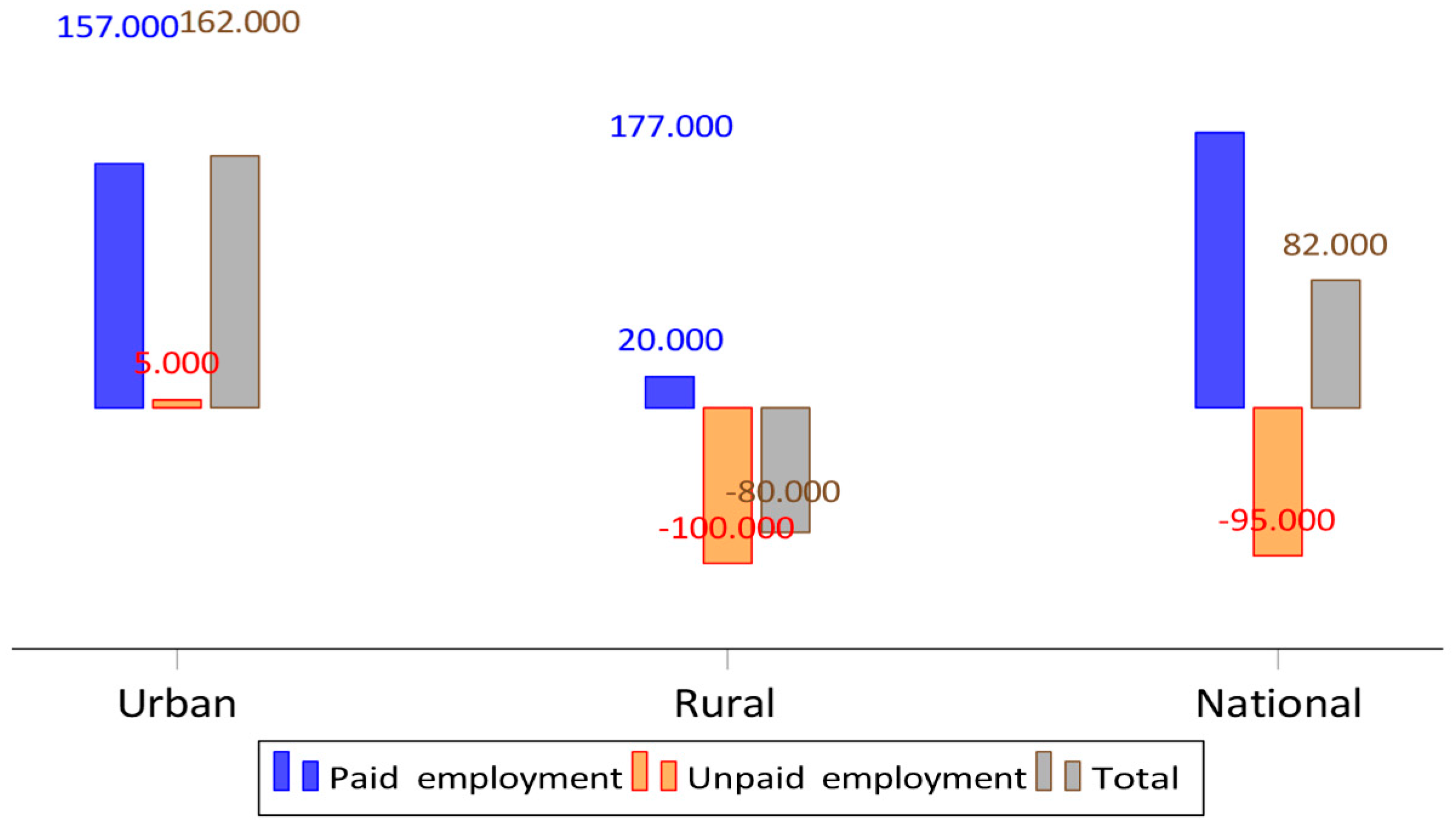

Figure 3.

Variation in employment by area and type (in number of jobs).

Figure 3.

Variation in employment by area and type (in number of jobs).

In 2024, the Moroccan economy recorded a net creation of 82,000 jobs (HCP, 2024). This figure is the result of two contrasting dynamics: a gain of 162,000 jobs in urban areas and a loss of 80,000 jobs in rural areas. This divergence highlights a persistent structural imbalance between urban and rural labor markets, where cities continue to benefit more directly from economic growth and investment.

When broken down by type of employment, the majority of newly created positions were paid jobs, totaling 177,000 new posts, with 157,000 of them located in urban areas and only 20,000 in rural zones. This reflects the concentration of formal and wage-based employment in cities, where both private sector activity and public services are more developed(HCP, 2024).

In contrast, unpaid employment (which often includes family labor or informal subsistence activities) saw a significant decline of 95,000 jobs. This was primarily due to a sharp drop of 100,000 unpaid positions in rural areas, partly offset by a minor increase of 5,000 unpaid roles in urban areas. This trend may be interpreted in two ways: either as a move towards more formal employment in some rural zones, or as a signal of deeper economic hardship forcing family units to abandon non-remunerated work that is no longer viable. From a sectoral perspective, the data confirms that, with the sole exception of agriculture, all major sectors of activity contributed positively to job creation in 2024(HCP, 2024).

The services sector led the trend, generating 160,000 jobs overall, of which 141,000 were urban and 18,000 were rural. This includes a wide range of subsectors: Commercial trade added 51,000 jobs, likely reflecting retail and wholesale recovery post-pandemic. Public and community services added 44,000 jobs, possibly due to expanded public hiring or NGO activities. Finance, insurance, real estate, scientific and administrative services added 39,000 jobs, showing the vitality of knowledge-intensive and support service industries. The industrial sector created 46,000 jobs, including 35,000 in urban and 11,000 in rural areas, indicating continued investment in manufacturing and processing, particularly in industrial zones near cities.

The 2024 labor market data for Morocco confirms both progress and persistent fragilities. While urban-based, wage-paying sectors like services and industry continue to absorb new labor and drive job creation, rural areas — especially those dependent on agriculture — are experiencing job losses and structural constraints. The rural-urban divide remains a key policy challenge, and targeted investment in rural job creation, formalization of labor, and sectoral diversification are crucial to ensure inclusive growth.

3.2. Rising Unemployment

The evolution of unemployment in Morocco over recent years reveals a mixed trajectory, characterized by significant fluctuations depending on the period. Following a gradual decline between 2017 and 2019, the labor market experienced a major shock in 2020 due to the global health crisis, resulting in a sharp increase in unemployment. A modest recovery began to emerge in 2021 and 2022, but this positive trend soon weakened, giving way to a new phase of deterioration between 2023 and 2024. In concrete terms, after recording approximately 1,216,000 unemployed individuals in 2017, Morocco saw a moderate upward trend until 2019, before witnessing a sharp spike in 2020 as the pandemic disrupted economic activity, pushing the number of unemployed beyond 1,400,000(HCP, 2024).

This surge in unemployment was partially mitigated by the economic rebound observed in 2021 and 2022. However, the labor market remained fragile and vulnerable to structural imbalances. Between 2023 and 2024, unemployment rose once again, increasing by 58,000 individuals—from 1,580,000 to 1,638,000—which represents a 4% year-on-year increase. This worsening situation is attributed to a rise in unemployment in both urban and rural areas, with urban unemployment increasing by 42,000 and rural unemployment by 15,000, highlighting the persistent disparity in labor market resilience across different geographic areas(HCP, 2024).

3.3. The Evolution of Recruitment Platforms in Morocco

3.3.1. History and Structure of the Intermediation Market

With the rise and persistence of graduate unemployment since the 1980s, the need to restructure the public employment service gradually became apparent. The creation of a dedicated entity for labor market intermediation emerged as a priority for Moroccan public authorities. This process went through several phases of development, from municipal placement offices (established in 1921) to Employment Information and Orientation Centers (CIOPE), ultimately leading to the establishment of the National Agency for the Promotion of Employment and Skills (ANAPEC) in 2001.

ANAPEC’s mission is to support job seekers and assist employers in defining their skill needs by providing intermediation services between labor supply and demand. To optimize its services, its network was expanded to include 12 regional agencies, 96 provincial and prefectural agencies, as well as 10 university-based agencies by the end of 2022. Mobile units were also deployed to reach rural and peri- urban areas.

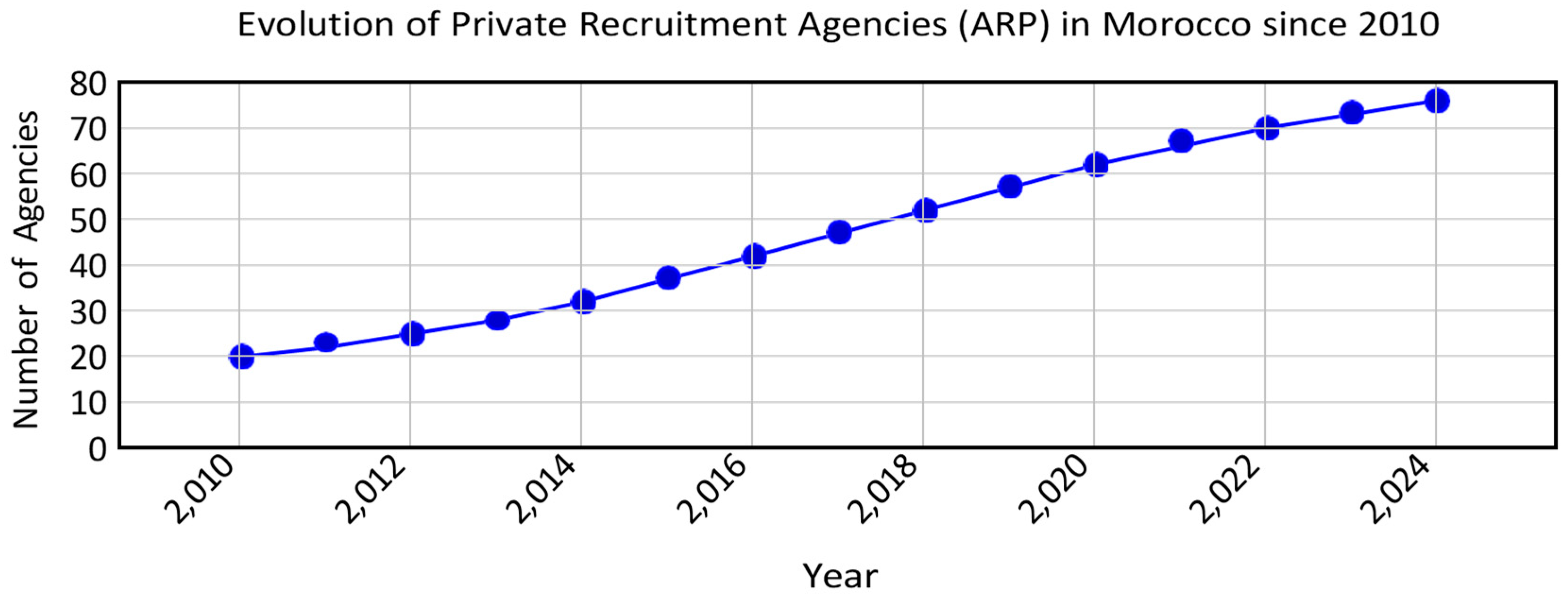

Figure 4.

Evolution of Private Recruitment Agencies (ARP) in Morocco between 2010-2024.

Figure 4.

Evolution of Private Recruitment Agencies (ARP) in Morocco between 2010-2024.

In parallel, the private sector was authorized to participate in labor market intermediation through Law 65-99, which defines private recruitment agencies (PRAs) as entities authorized to connect labor supply and demand. As of the end of September 2023, 75 private agencies were officially licensed to operate, compared to 68 in 2019 and 55 in 2015. However, a significant majority of these agencies (63%) are located in Casablanca, while only 9% are based in Rabat and 4% in Marrakech.

3.3.2. The Digital Shift in Recruitment in Morocco

The rise of digital technology has profoundly transformed the intermediation market, with the growing adoption of online recruitment platforms. The use of digital platforms has intensified, particularly due to the speed and efficiency they offer to both employers and job seekers. In this regard, the introduction of job boards in the early 2000s marked a turning point. Platforms such as Rekrute.com and Emploi.ma emerged as pioneers in online recruitment, offering companies a space to post job openings and candidates an easier way to apply. At that time, online recruitment was still seen as a complement to traditional methods.

In the 2010s, the emergence of more sophisticated platforms transformed the sector. Players like Novojob, Bayt.com, and LinkedIn Morocco introduced advanced features such as automatic skill match- ing, online assessment tests, and predictive analysis of applications. Recruitment became more targeted and efficient, allowing employers to reduce the time needed to identify talent.

The COVID-19 crisis accelerated the adoption of digital solutions in recruitment. Many Moroccan companies, constrained by health restrictions, adopted tools such as Indeed Morocco, Jobi.ma, and Jobeo, which offer video conferencing and online interview functionalities. As a result, the use of recruitment platforms skyrocketed, even among small businesses and sectors that had previously been reluctant to go digital (see

Table 1).

Table 1.

Main Digital Recruitment Platforms in Morocco.

Table 1.

Main Digital Recruitment Platforms in Morocco.

| Platform |

Description |

Key Features |

|

Target Audience |

| ReKrute.com |

Leading online recruit- ment site in Morocco |

Advanced large CV |

matching, database, |

Large companies, SMEs, executives |

|

Emploi.ma Generalist job board for Moroccan job market |

|

Bayt.com MENA region recruit- ment specialist with pres- ence in Morocco |

|

LinkedIn Professional networking platform also used for recruitment |

|

Indeed Maroc International job aggre- gator widely used in Mo- rocco |

|

Dreamjob.ma Moroccan platform for job listings and career tips |

|

Alwadifa-Maroc.com Specialized in government and public sector jobs |

|

Anapec.org Official public employ- ment service platform |

|

MarocAnnonces.com General classifieds platform with job section premium services for employers Free posting, easy application process, wide visibility International CV pool, skill assessments, smart filtering Job alerts, networking, company profiles Aggregates listings, employer ratings, quick applications Job listings, career advice, sectoral updates Public exams updates, job offers in administration Skills matching, training offers, guidance services Broad listing categories, local recruitment visibility |

| General job seekers |

| Job seekers looking locally or abroad |

| Professionals and recent graduates |

| All job seekers |

| Young professionals and students |

| Job seekers targeting public sector |

| Young job seekers and the unemployed |

| Informal and general job seekers |

By 2023, more than 70% of recruitments in large Moroccan companies were conducted online through these platforms, reflecting an accelerated digitalization of the sector (Source: Ministry of Economic Inclusion, Small Business, Employment and Skills, 2023). These platforms enable companies to publish job offers, analyze applications, and assess candidates’ skills through efficient digital tools. Since 2015, the recruitment tech market in Morocco has grown significantly, driven by digitalization and the need to streamline hiring processes.

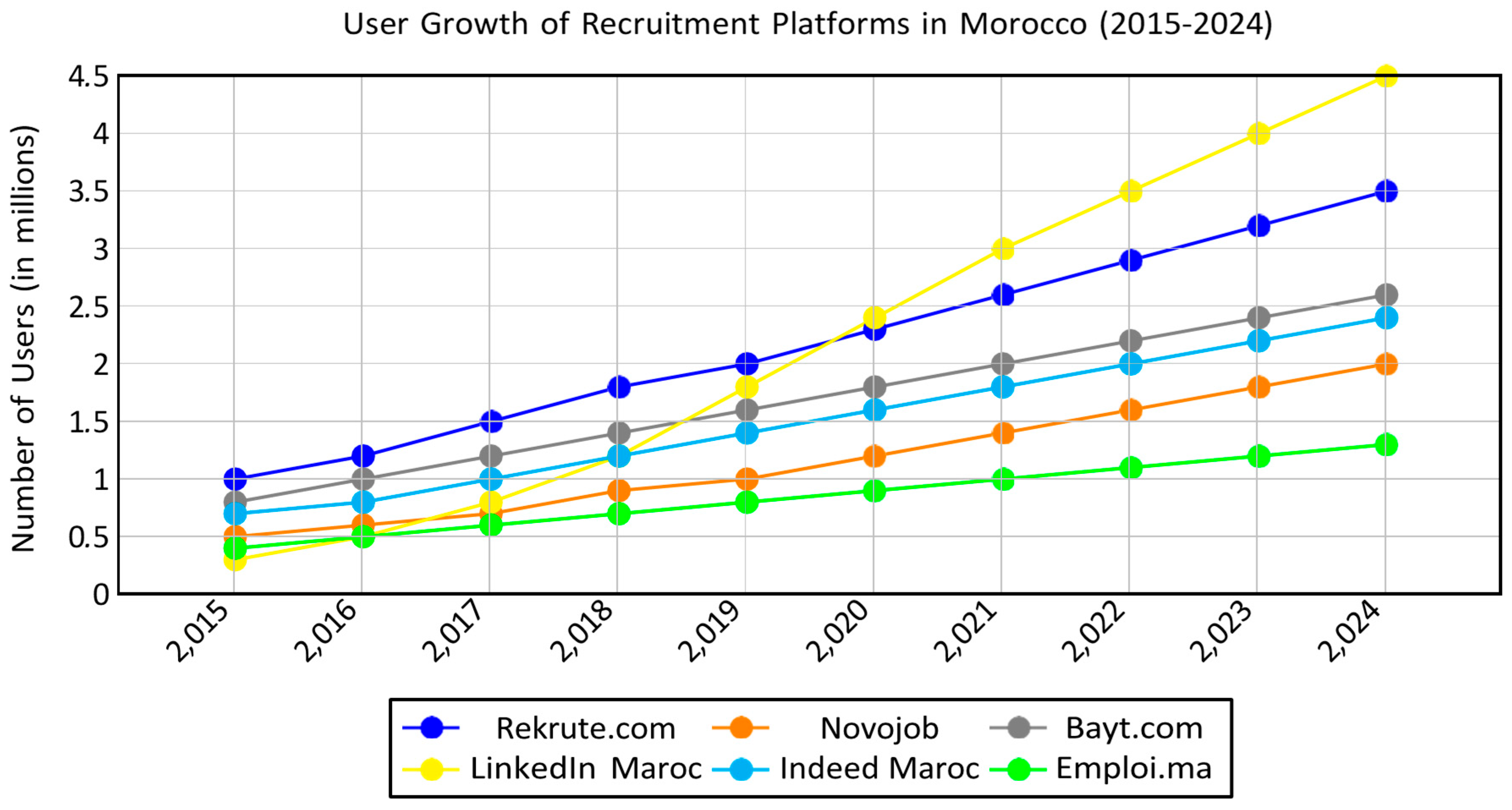

ReKrute.com, the market leader, increased its user base from 1.2 million in 2015 to 3.4 million in 2024, thanks to its advanced matching algorithms and strong presence among large companies. Novojob, although newer, experienced rapid growth, reaching 1.8 million users by 2024. Bayt.com, with its regional reach across the MENA region, grew steadily from 1.5 million to 2.5 million users. LinkedIn Morocco saw the most notable growth, jumping from 2 million users in 2015 to over 4.2 million in 2024, driven by its international positioning and increasing popularity among professionals and recruiters. Indeed Morocco followed a similar upward trend, reaching 2.7 million users in 2024. Finally, Handicap Maroc, a platform dedicated to the inclusion of people with disabilities, is gaining visibility with a user base of 450,000 in 2024, despite being relatively new.

Figure 5.

User Growth of Recruitment Platforms in Morocco (2015-2024).

Figure 5.

User Growth of Recruitment Platforms in Morocco (2015-2024).

This evolution reflects the growing digitalization of recruitment in Morocco, highlighting the importance of these tools in improving intermediation in the labor market.

3.3.3. Differences Between Traditional Platforms and E-Recruitment

The evolution of recruitment in Morocco highlights fundamental differences between traditional job boards and e-recruitment platforms:

Table 2.

Key Differences Between Job Boards and E-Recruitment Platforms.

Table 2.

Key Differences Between Job Boards and E-Recruitment Platforms.

| Characteristics |

Job Boards |

E-Recruitment |

| Scope |

Aggregates job offers from vari-

ous sources |

Includes all digital tools and

strategies used for recruitment |

| Employer Involvement |

Limited to job postings |

More involved, with application

management and online assess-

ments |

| User Experience |

Can be overwhelmed by the vol-

ume of job offers |

More personalized and tailored

to candidates |

| Cost |

Generally free for job seekers |

Varies depending on the tools

and services used |

The adoption of these digital solutions has enhanced the visibility of job offers and reduced recruitment timeframes—cutting them by an average of 30% compared to traditional methods.

3.3.4. Profile of Users of Recruitment Platforms and Job Positions in Demand on the Labor Market

According to the prospective monitoring survey conducted by ANAPEC in 2022, the use of digital re- cruitment platforms has grown significantly in recent years, accompanying a transformation in job search and recruitment methods in Morocco (see

Figure 6). The analysis of user profiles on these platforms re- veals a variety of profiles, although certain trends are clearly emerging. Young graduates represent the most active category on these platforms, accounting for approximately 65% of users. Among them, higher education graduates make up the majority, with a proportion of 72%, compared to 28% for voca- tional training graduates. Additionally, individuals in their first job represent nearly 45% of registered candidates, confirming the key role of these platforms in helping young people enter the labor market.

The gender distribution reveals a slight male predominance, with 54% men compared to 46% women among users in 2022 and 2023. However, this proportion varies depending on the targeted sectors: the fields of information technology and digital services show a strong male presence (62%), whereas the commerce and service sectors exhibit a more balanced representation between men and women (see

Figure 7).

Regarding regionalization, the survey highlights a strong concentration of users in the country’s major economic cities. Casablanca-Settat represents 35% of users, followed by Rabat-Sal’e-K’enitra (15%) and Tanger-T’etouan-Al Hoceima (12%). In contrast, the interior and southern regions of the country show more limited adoption of digital recruitment platforms, often due to restricted internet access and lower levels of digitalization in local businesses.

User behavior reveals a clear preference for certain types of applications. Approximately 60% of job seekers use the platforms to apply for permanent positions (CDI), compared to 25% for fixed-term contracts (CDD) and 15% for internships or temporary assignments. Furthermore, companies largely favor profiles with prior experience, although 56% of job postings on these platforms do not necessarily require experience, particularly in high-demand sectors like offshoring and retail.

Additionally, according to the Rekrute Barometer survey (2023), five sectors account for 50% of recruitment intentions recorded in 2022, 2023, and 2024. These include the automotive industry, ICT and offshoring, education and training, administrative and support services, and tourism, hospitality, and catering, which are among the most dynamic sectors in terms of recruitment.

Among the most sought-after jobs, offshoring stands out with a strong demand for teleoperators, accounting for nearly 20% of online job offers. This sector, driven by the rise of call centers and outsourced services, continues to attract a large number of young graduates. In the automotive industry, positions for wiring and production operators are particularly in demand, with a 15% increase compared to 2021. The retail and distribution sector is also experiencing strong growth, with increased demand for customer service managers, salespeople, and service agents.

The level of qualification required by employers varies across sectors. 44% of job offers require a degree of Bac+3 or higher, especially in the fields of ICT, finance, and business services. In contrast, 28% of recruitments are for profiles with a technician or vocational qualification, particularly in industrial production and construction jobs. Job offers targeting candidates without a diploma remain limited, accounting for about 5% of the job postings on digital platforms.

Based on the Moroccan case, following the survey, the time to find a job through digital recruitment platforms varies significantly depending on the sector, the applicant’s profile, and the region. However, some general insights are provided by surveys and studies on the topic:

Table 3.

Average time to find a job in different sectors and regions in Morocco.

Table 3.

Average time to find a job in different sectors and regions in Morocco.

| Factor |

Average Time to Find a Job |

| Overall Average |

4 to 6 months |

| Offshoring Sector |

3 to 4 months |

| Automotive and Industrial Sectors |

4 to 6 months |

| Education and Training |

6 to 9 months |

| Urban Areas (e.g., Casablanca, Rabat) |

3 to 5 months |

| Rural and Southern Regions |

6 to 12 months |

| Higher Education (Bac+3 and above) |

3 to 5 months |

| Lower Qualifications (Vocational Training) |

6 months to 1 year |

As we examined, the adoption of digital recruitment platforms in Morocco, highlighting a concentra- tion of users in major cities like Casablanca, Rabat, and Tanger, with limited usage in rural and southern regions due to infrastructure challenges. Job seekers primarily prefer permanent contracts (CDI), with many employers favoring candidates with prior experience, although sectors like offshoring remain open to less experienced applicants.

Key sectors like offshoring, automotive, and tourism show strong recruitment demand, while qual- ifications vary, with higher education (Bac+3 and above) being preferred. The time to secure a job typically ranges from 4 to 6 months, with faster job searches in urban areas and sectors like offshoring, and longer durations in rural areas or for candidates with lower qualifications.

4. Impact Evaluation of Job-Skills Matching Platforms Using the Difference-in-Differences (DiD) Method

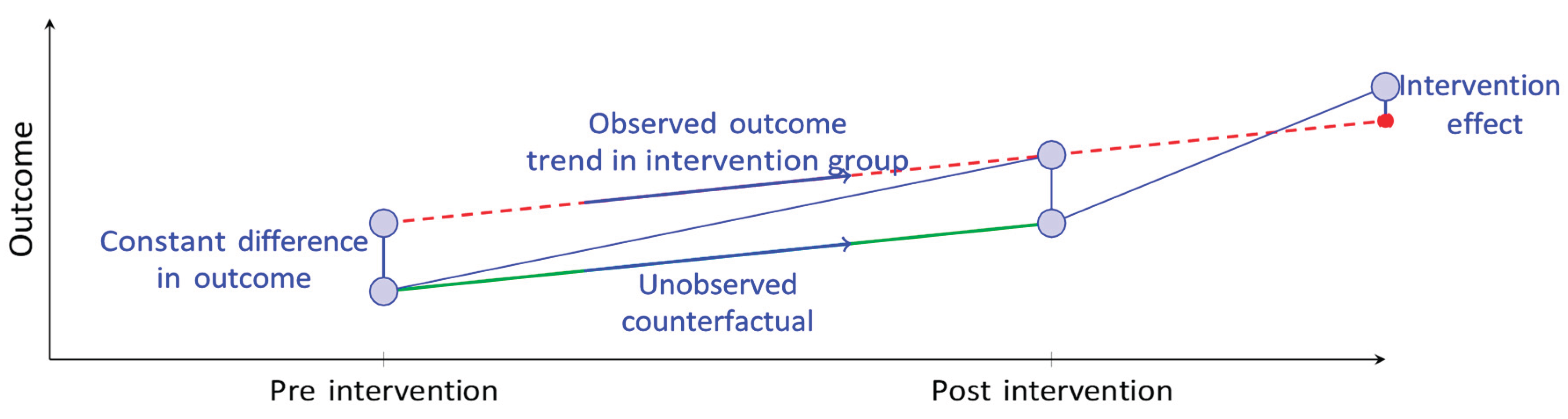

Evaluating the impact of digital job-skills matching platforms is a central concern for understanding their effectiveness in improving the employability of young graduates in Morocco. To identify the causal effects of using such platforms on employment outcomes, we employ the Difference-in-Differences (DiD) method, a robust econometric approach that estimates the impact of an intervention by comparing the evolution of a treated group (platform users) and a control group (non-users) before and after the introduction of the platforms.

4.1. Presentation of the Difference-in-Differences Method

The Difference-in-Differences (DiD) approach relies on the key assumption that, in the absence of the intervention, the treated and control groups would have followed parallel employment trajectories. This allows for the isolation of the specific effect of platform usage on employment outcomes. To strengthen causal inference, the analysis draws on Rubin’s Causal Model, or the Potential Outcomes Framework, which compares observed outcomes to the hypothetical scenario where no treatment was applied.

However, we can never observe both potential outcomes for the same individual simultaneously — this is known as the fundamental problem of causal inference. Therefore, we use an empirical approach based on DiD to reconstruct the counterfactual. In this context, we distinguish between two effects of interest:

The Average Treatment Effect (ATE): the average impact of the treatment on the entire target population.

The Average Treatment Effect on the Treated

(ATT): the impact of the treatment only on those who actually received it (i.e., platform users). In our case,it is particularly relevant for our study, as we aim to measure the real effect of the platforms on their users. Formally, the DiD model can be written as:

Where:

Yit is the outcome variable of interest (e.g., employment status, salary, job search duration) for individual i at time t,

Ti is a binary indicator equal to 1 if the individual belongs to the treatment group (platform user), 0 otherwise,

Postt is a binary indicator equal to 1 for post-treatment periods and 0 otherwise,

Ti × Postt is the interaction term; the coefficient δ captures the causal effect of platform usage,

Xit is a vector of control variables (age, degree, region, etc.),

The graphical representation (below) of the DiD model helps to visualize the estimated treatment effect. We observe two groups (treated and control) over two periods (pre- and post-intervention).

Figure 8.

Effect of intervention on outcome trends.

Figure 8.

Effect of intervention on outcome trends.

Assuming parallel trends in the absence of treatment, the control group (in green) serves as the counterfactual to estimate what the treated group’s trajectory (in red) would have been without the platform. The gap between the actual trajectory of the treated group and the estimated counterfactual trajectory represents the causal impact of the platform. Also, we can present a summary table illustrating the core logic of the Difference-in-Differences method. The table compares expected outcomes for the treated and control groups before and after the intervention. The net causal effect of the treatment is derived by subtracting the natural evolution observed in the control group from the total change observed in the treated group.

Table 4.

Synthetic illustration of the DiD method.

Table 4.

Synthetic illustration of the DiD method.

| Group |

Pre-intervent· (Post = 0) |

Post-intervent· (Post = 1) |

Difference |

| CG (T = 0) |

E[Y (0)|T = 0, Post = 0] |

E[Y (0)|T = 0, Post = 1] |

∆C = C1 − C0

|

| TG (T = 1) |

E[Y (0)|T = 1, Post = 0] |

E[Y (1)|T = 1, Post = 1] |

∆T = T1 − T0

|

| Difference-in-Differences (DiD) |

δ = ∆T − ∆C

|

Where:

4.2. Sampling, Database and Descriptive Statistics

The dataset used in this study comes from two separate sources provided by ANAPEC, covering the period from 2021 to 2024. The first includes individuals who used the national digital employment matching platform, while the second covers those who only accessed in-person services at ANAPEC agencies without using the digital platform. Respondents are young individuals aged 18 to 35, divided into a treatment group (platform users) and a control group (non-users).

Table 5.

Group distribution before and after platform introduction.

Table 5.

Group distribution before and after platform introduction.

| Group |

2021 (Before) |

2024 (After) |

Total |

Users (treated)

Non-users (control) |

128

121 |

145

139 |

273

260 |

| Total |

249 |

284 |

533 |

The following table (see

Table 6) presents the main socio-demographic characteristics of the two groups studied : platform users (treated group) and non-users (control group)—over two reference periods: 2021 and 2024. This comparison allows us to observe potential structural differences that may influence the outcomes of the impact evaluation.

In terms of age, the average was 26.3 years for the control group and 26.9 years for the treated group in 2021. By 2024, this had increased to 29.4 and 29.7 years, respectively. Regarding gender distribution, 48.4% of platform users were women in 2021, compared to 45.5% in the control group. These figures rose to 50.3% and 47.1% in 2024, indicating a slightly higher female participation among users. Urban residency remained high across both groups, with over 90% of participants living in urban areas and a marginally higher share among platform users.

Household size remained relatively stable over time, averaging around five members per household in both groups. However, the average number of children per individual was slightly higher in the control group, reaching 0.9 in 2024 compared to 0.7 among platform users. In terms of marital status, approximately 70% of participants were single in both groups, with a marginally higher proportion among the treated group. Overall, the two groups appear broadly comparable, although slight differences in gender composition, urban concentration, and education level may partly explain the variation in employment outcomes observed after the introduction of the platform.

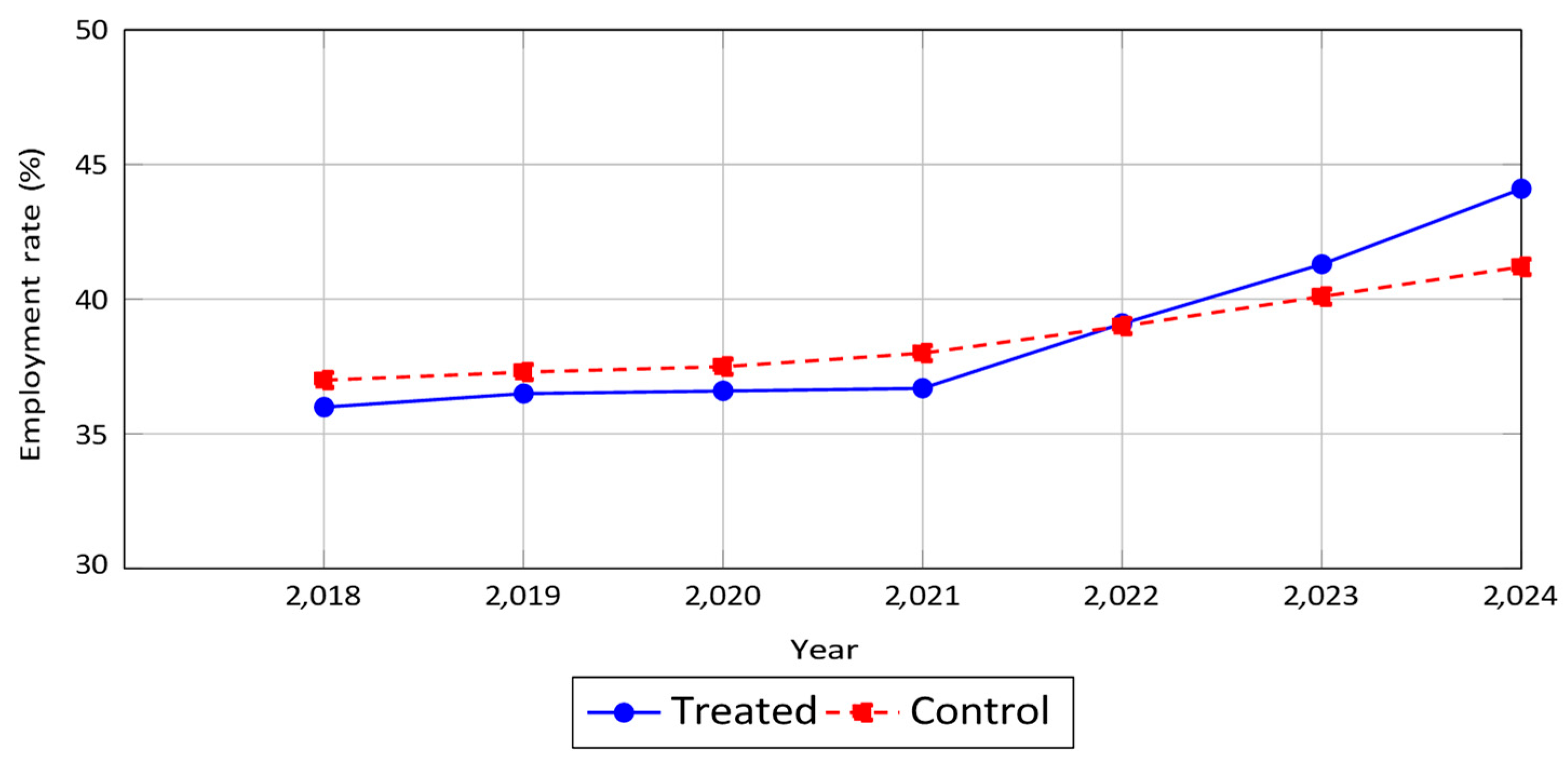

In 2021, the proportion of individuals with higher education was 38.8% in the control group and 42.2% in the treated group, a difference of 3.4%. By 2024, this gap increased to 5.3%, with 40.2% in the control group and 45.5% in the treated group. The share of individuals without a diploma was 9.1% in the control group and 7.0% in the treated group in 2021, a statistically significant difference of -2.1%, which decreased to -1.7% in 2024. Basic digital skills were reported by 55.4% of the control group and 67.2% of the treated group in 2021, a gap that widened to 14.5% in 2024. Advanced digital skills increased from 19.0% to 26.6% between control and treated groups in 2021, and this difference further rose to 14.2% in 2024. Regarding employment, 38.0% of the control group and 36.7% of the treated group were employed in 2021, a slight negative difference that turned positive in 2024, reaching 41.2% in the control group and 44.1% in the treated group.

4.3. Baseline Balance and GROUP comparability

Before proceeding with the estimation of the treatment effect using a Difference-in-Differences (DiD) approach, it is essential to verify that the treatment and control groups were comparable before the intervention. This ensures that any observed differences in outcomes after the intervention can plausibly be attributed to the treatment itself, rather than to pre-existing differences between groups.

We conduct a series of baseline balance checks on key sociodemographic and labor market variables measured in 2021, before exposure to the digital recruitment platform. Specifically, we report:

Mean comparisons between treatment and control groups using two-sample t -tests;

Standardized Mean Differences (SMD) to assess the magnitude of differences independently of sample size;

Chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

As shown in

Table 7, all baseline differences between the treatment and control groups are statistically non-significant at conventional levels (p-values

>0.4). Moreover, all standardized mean differences are well below 0.1, indicating a high degree of balance. This reinforces the assumption of parallel trends and supports the internal validity of the Difference-in-Differences estimation strategy.

Across all variables, the p-values from both mean comparisons and distributional tests (Ander- son–Darling for continuous variables and Pearson’s Chi-squared for categorical variables) indicate no statistically significant differences between the treatment and control groups at baseline.

Moreover, all standardized mean differences (SMDs) fall below the 0.1 threshold, further supporting the argument that the two groups are well balanced. These results lend credibility to the common trends assumption required for Difference-in-Differences estimation.

Figure 9.

Employment trends: Treated vs Control (2017–2024).

Figure 9.

Employment trends: Treated vs Control (2017–2024).

The figure above illustrates the evolution of employment rates for both the treated group (platform users) and the control group (non-users) from 2017 to 2024. This visualization serves to assess the parallel trends assumption, which is a key condition for the validity of the Difference-in-Differences (DiD) methodology. From 2018 to 2021, before the introduction of the digital employment platform, the employment trajectories of the two groups appear to follow similar and stable trends, with only minor fluctuations. The treated group consistently maintains slightly lower employment rates than the control group, but the gap remains relatively constant, suggesting no pre-existing divergent dynamics between the groups. Overall, the visual inspection of the pre-intervention period supports the parallel trends assumption, validating the application of the DiD framework for estimating the causal effect of the platform.

5. Results and Discussion

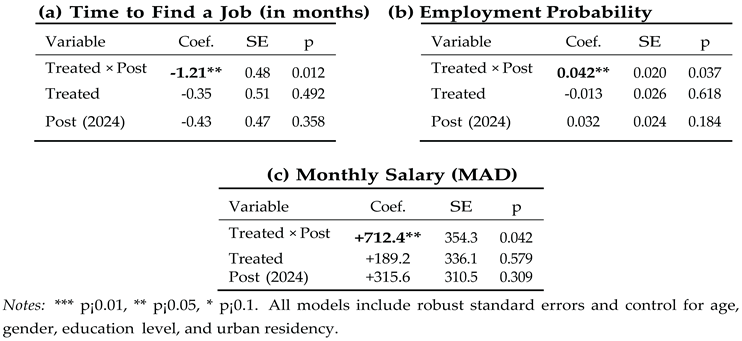

The results obtained from the Difference-in-Differences (DiD) regressions offer valuable insights into the impact of the digital employment platform on youth labor market integration in Morocco.

Table 8 panel (a) presents the baseline DiD regression results. The coefficient associated with the interaction term

Treated × Post is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level (

δ = 0.042,

p = 0.037), suggesting that, on average, users of the platform were 4.2 percentage points more likely to be employed in 2024 compared to their non-user counterparts, after controlling for baseline covariates such as age, gender, education level, and urban residency. This provides robust empirical evidence that the platform contributed positively to employment outcomes, particularly in a context where young people often face extended periods of job search and underemployment.

Table 8 panel (b) introduces a triple interaction term to test for heterogeneous effects by education level. The coefficient of the interaction

Treated × Post × Higher Education is also positive and significant (

β = 0.063,

p = 0.043), indicating that the platform had a stronger effect on individuals with higher education. Specifically, users with a university-level education experienced an additional 6.3 percentage- point gain in employment probability, relative to similarly educated non-users. This highlights a potential amplification effect: the digital platform appears to benefit individuals who already possess certain human capital advantages, likely due to their digital literacy, access to online tools, and ability to navigate virtual recruitment spaces. These findings align with existing literature emphasizing that technology-based employment tools tend to reinforce pre-existing disparities if digital inequality is not addressed.

Furthermore,

Table 8 panel (c) explores whether location, particularly urban versus rural residency, affects the platform’s impact. The coefficient for the triple interaction

Treated × Post × Urban is statistically significant and positive (

β = 0.059,

p = 0.041), suggesting that urban users of the platform experienced a significantly higher employment gain relative to their rural peers. This likely reflects differences in digital infrastructure, connectivity, and the density of job opportunities typically found in urban settings. While the platform was designed as a national tool for democratizing access to employment, the data suggest its effects may be spatially uneven, reinforcing the digital divide between rural and urban populations.

Altogether, the results across the three specifications underscore a central insight: although the platform appears to have a positive average effect, its benefits are not equally distributed. Users with higher education and those living in urban areas experience more pronounced employment gains. These patterns raise important policy questions regarding digital inclusion and the need to complement digital tools with targeted support measures for disadvantaged groups. The findings also strengthen the case for further investments in digital literacy, infrastructure, and awareness campaigns, particularly for women, rural populations, and those with lower educational attainment.

As shown, the empirical analysis supports the hypothesis that the digital employment matching platform has a causal and positive impact on job market integration. However, the magnitude and distribution of this impact depend heavily on socioeconomic and geographic factors, warranting further exploration of inclusive strategies to ensure equitable benefits from digital transformation in public employment services.

6. Platform Impact on Job Access, Duration, and Quality

Digital recruitment platforms not only influence whether individuals find jobs, but also how quickly they do so and the quality of employment they access. To assess the multidimensional impact of platform usage, we estimate three Difference-in-Differences (DiD) models using different outcome variables: (i) the average duration of job search (measured in months), (ii) the likelihood of being employed, and (iii) the monthly wage for those employed. These indicators collectively help evaluate both the effectiveness and the efficiency of digital employment platforms.

The results in

Table 9 provide compelling evidence of the platform’s multidimensional benefits. In Panel (a), the DiD estimate for time to employment shows that platform users found jobs, on average,

1.21 months faster than their counterparts in the control group, a result that is statistically significant at the 5% level. This suggests the platform accelerates job matching by improving information flow,automating application tracking, and simplifying the application process. Faster access to employment is particularly valuable in a context of high youth unemployment and job market uncertainty.

In Panel (b), we replicate the earlier finding that the probability of being employed increases by 4.2 percentage points for platform users relative to non-users, a difference that remains significant and robust after including covariates. This reinforces the interpretation that the platform has a tangible impact on job access, beyond what would be expected from general labor market improvements.

Perhaps most strikingly, Panel (c) shows that employed platform users earn, on average, 712 Mo- roccan dirhams more per month than comparable non-users—a statistically significant effect. This indicates that the platform not only helps users find jobs faster, but also improves the quality of those jobs, possibly by expanding access to better-paying sectors or improving alignment between skills and job requirements.

Taken together, these findings suggest that digital recruitment platforms offer a high return on investment in terms of employment policy. They reduce friction in the job search process, increase insertion rates, and raise the standard of employment attained. The effect on salary in particular implies that the platform helps users access more formal, stable, or higher-skilled positions. However, these benefits may not be equally distributed, as suggested by prior heterogeneity analyses. Further research should examine whether these gains persist over time and whether similar effects are observed in rural areas or among less-educated youth. The platform appears to significantly improve both the speed and quality of employment outcomes, making it a valuable lever in public strategies for labor market integration.

7. Policy Recommendations and Study Limitations

The results of this study suggest that digital recruitment platforms can serve as effective policy in- struments to enhance youth employment outcomes in Morocco. The observed reductions in job search duration, improvements in employment probability, and increased average salaries among platform users highlight not only the efficiency of these tools in matching supply and demand but also their potential to raise the quality of employment. These findings support a shift in national employment strategy toward a more technology-enabled, user-centered approach. However, for these tools to be fully transformative, their integration must be supported by a set of complementary public policies that address broader structural barriers.

First, there is a pressing need to improve digital access and usage across socio-demographic divides. The current benefits of digital platforms are not equally distributed: educated, urban youth are more likely to use them effectively, while young people in rural areas and those with limited digital literacy remain largely excluded. Public institutions should therefore prioritize investment in local training programs in digital and soft skills, and ensure the integration of digital recruitment tools within physical job centers, particularly in underserved regions. These platforms must also evolve to better accommodate non-standard users, including those with disabilities, older jobseekers, and informal workers transitioning into the formal economy. This can be achieved by designing more inclusive user interfaces, simplifying language, integrating local dialect options, and ensuring platform accessibility via mobile devices, which remain the primary digital access point for most low-income populations.

Second, digital recruitment efforts should be embedded in a larger ecosystem of employment support. Simply creating accounts and applying for jobs online does not guarantee results; young jobseekers also need personalized guidance, feedback loops, and mentoring to navigate labor market complexity. The development of hybrid services—where digital matching is combined with human support through ANAPEC agents or partner NGOs—may significantly enhance the quality of matching and help bridge the gap between jobseekers’ expectations and employers’ evolving needs. Partnerships with private sector actors, particularly in high-growth industries such as offshoring, digital services, and green jobs, should be pursued to ensure job offers posted on platforms reflect real and dynamic demand.

Third, we recommend the development of a performance-monitoring system for digital platforms, which would include key performance indicators such as time-to-placement, job sustainability after 6 or 12 months, and satisfaction from both employers and candidates. Real-time data analytics could also identify patterns of exclusion or drop-off in user activity, allowing for targeted interventions. Furthermore, governments should explore incentive structures to encourage SMEs and local businesses to post quality job offers and to engage actively with platform users, possibly through tax incentives or branding support. Despite the robustness of our analytical approach, the study is not without limitations. The main empirical strategy used—a Difference-in-Differences model—relies on the assumption of parallel trends, which we validated graphically and through baseline balance checks, but which cannot fully account for unobservable time-varying factors that may have differently affected the treatment and control groups. In addition, while our dataset covers a large sample over a three-year period, it remains a cross-sectional panel without longitudinal tracking of individual outcomes over time. As such, we cannot observe the sustainability of employment placements or detect possible rebound effects, such as job mismatches or underemployment. Moreover, our outcome variables—particularly job search duration and salary—are based on self-reported data, which introduces the risk of recall bias and social desirability bias, especially in a context where employment carries significant social weight.

Another limitation relates to the voluntary nature of platform use. Users are self-selected, and although we controlled for observable characteristics such as education, gender, and urban location, unobserved characteristics such as motivation, ambition, or network size may have influenced both the decision to use the platform and the employment outcome itself. This raises potential concerns about selection bias, which could be better addressed in future work using propensity score matching, instru- mental variable approaches, or panel fixed-effects models.

Lastly, the scope of the study is limited to short-term outcomes. While we observe encouraging improvements in employment metrics within a relatively short follow-up window, we do not yet know whether these effects persist over time or translate into career advancement, job stability, or upward social mobility. Future research should extend this analysis over a longer horizon, ideally using administrative data or mixed-methods approaches to capture qualitative dimensions such as user experience, satisfaction, and professional integration trajectories.

While our findings offer robust evidence in favor of digital employment platforms as tools for improving youth labor market outcomes in Morocco, their broader success will depend on how equitably they are deployed, how well they are embedded within institutional ecosystems, and how dynamically they evolve to reflect labor market realities. Equipping all young people—not just the digitally privileged—with the means to benefit from these tools remains a key policy priority, one that requires sustained political will, cross-sector collaboration, and a commitment to inclusive innovation.

8. Conclusion

This study has explored the effectiveness of digital platforms in bridging the gap between job seekers and employers in Morocco, particularly focusing on how these platforms influence the professional integration of young graduates. By employing a Difference-in-Differences (DiD) methodology, utilizing data from the ANAPEC database for the years 2021–2024, we have been able to draw key insights into the causal impact of these platforms on employment outcomes.

Our analysis shows that the use of digital platforms has led to a statistically significant improvement in the employment rates of young graduates, particularly in terms of faster job placement and better matches between available skills and job requirements. These findings support the hypothesis that digital platforms can enhance the efficiency of the labor market, offering opportunities to both job seekers and employers that were previously less accessible through traditional channels. The evidence also indicates that these platforms are playing a critical role in reducing the time-to-employment for youth, thus contributing to mitigating the persistent problem of youth unemployment in Morocco.

However, the analysis also reveals challenges that must be addressed. The findings suggest that while digital platforms are effective in some regions, there is significant variability in their impact across different geographical areas. This discrepancy can be attributed to differences in digital literacy, internet access, and the overall digital infrastructure in rural versus urban regions. These disparities highlight the need for targeted policies that ensure equitable access to digital job matching tools and the upskilling of the youth workforce to enhance their digital competencies.

Moreover, although digital platforms have demonstrated positive effects on job matching, they are not a panacea for all employment challenges. The complexities of youth employment in Morocco require a multifaceted approach, involving not only digital solutions but also the strengthening of traditional labor market institutions, education systems, and more robust employment policies that address the broader socio-economic context. The lessons learned from this study could guide future initiatives aimed at reducing youth unemployment in Morocco and the broader MENA region.

References

- ANAPEC. (2022). Rapport d’activit’e 2021–2022. Agence Nationale de Promotion de l’Emploi et des Comp’etences.

- Barocas, S.; Selbst, A.D. Big Data’s Disparate Impact. California Law Review 2016, 104, 671–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Lee, J.W. International Data on Educational Attainment: Updates and Implications. Oxford Economic Papers 2000, 52, 541–563. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. (1964). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. University of Chicago Press.

- Blundell, R.; Costa-Dias, M. Evaluation Methods for Non- Experimental Data. Fiscal Studies 2000, 21, 427–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Long, D. Estimating the Effect of Education on Health and Mortality: A Difference-in-Differences Approach. American Economic Review 2007, 97, 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A.; Dahan, A. Digital platforms: Transforming the labor market. Journal of Business Research 2017, 74, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E.L. , Scheinkman, J.A.; Shleifer, A. Growth in cities. Journal of Political Economy 2004, 100, 1126–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Miles, T.J. Digital Inequality and Online Job Seeking. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2020, 34, 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, C. The Quiet Revolution that Transformed Women’s Employment, Edu- cation, and Family. American Economic Review 2006, 96, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, P.; Wadsworth, J. The Labor Market in the Great Recession. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 2011, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, M. Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies, and statistics. Women’s Studies International Forum 2011, 34, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, J.J. The effects of algorithmic labor market recommendations. Management Science 2017, 63, 1805–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, P.; Mansour, H. Is Internet job search still ineffective? Eco- nomic Journal 2014, 124, 1213–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, V. Digital Labour Markets: Exploring the Future of Work. Journal of Information Technology 2020, 35, 275–296. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B.D.; Mok, W.K.C. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics and the Measurement of Income Inequality. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2016, 30, 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2024). International Migration Outlook 2024. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Pissarides(2017)] Pissarides, C.A. (2017). The Economics of Labor Markets. MIT Press.

- Reimer, D.; Moretti, E.; Jacobsen, S. Unemployment Benefits and Job Search: The Impact of Digital Job Matching. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2020, 12, 67–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rekrute. (2023). Barom`etre de l’emploi 2023 au Maroc. Rapport institutionnel interne.

- Reuters. (2024). Germany to expel 2,700 Moroccan migrants. Reuters World News, February 2024.

- Redalyc. (n.d.). La politique migratoire du Maroc : enjeux, dispositifs et limites. Revue des E’tudes sur la Migration en Afrique du Nord.

- Shaw, R. The digital revolution and the evolution of job markets. Journal of Busi- ness and Economics 2017, 45, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tambe, P.; Cappelli, P.; Yakubovich, V. Artificial intelligence in human resources management: Challenges and a path forward. California Management Review 2019, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddoups, S. Understanding the role of digital platforms in the modern labor market. International Labour Review 2022, 161, 323–345. [Google Scholar]

- Welt. (2024). EU asylum applications drop as migration policies tighten. Die Welt, 20 March.

- World Bank. (2021). World Development Report 2021: Data for Better Lives. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

- Yousef, T. The political economy of youth unemployment in the MENA region. World Development 2013, 51, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, S. , Pardo, A.; Carrillo, M. Digital platforms and their role in labor market development. Labor Economics Review 2021, 27, 122–144. [Google Scholar]

- Arntz, M.; Gregory, T.; Zierahn, U. The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 189. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bessen, J.E. (2019). AI and Jobs: The Role of Demand. NBER Working Paper Series, No. 24235.

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. (2014). The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Cappelli, P. Skill gaps, skill shortages, and skill mismatch: Evidence and arguments for the United States. Industrial Relations Research Journal 2015, 46, 347–370. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Han, S.; Jeong, S. How online platforms can enhance job matching. International Journal of Human Resource Management 2016, 27, 642–662. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, V. The rise of the ’just-in-time workforce’: On-demand work, crowdwork, and labor protection in the gig-economy. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal 2016, 37, 471–504. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.B. The Rise and Fall of American Labor Market Institutions. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2019, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Future of Work: OECD Employment Outlook 2019; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Duggan, M. (2019). Online Dating & Relationships. Pew Research Center.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).