1. Introduction

Narrowing the urban-rural income gap serves as a critical pathway to driving sustainable development and realizing common prosperity [

1,

2]. Since reform and opening-up, China’s economy has grown rapidly, with its GDP expansion consistently outperforming global averages. Through sustained government efforts, China's urban-rural income ratio has narrowed from 2.88 in 2012 to 2.34 in 2024, demonstrating continuous convergence in income distribution patterns [

3]. However, the issue of urban-rural income gap remains fundamentally unresolved [

4,

5,

6,

7]. During the same period, the Gini coefficient has consistently exceeded 0.45, indicating that inequality remains pronounced. In particular, the low-income population is predominantly concentrated in rural areas. Therefore, enhancing rural low-income groups' earnings and thereby narrowing the urban-rural income gap are the key priorities for promoting balanced development in the future.

The rapid development of digital technology offers a highly promising solution. Its application is transforming socioeconomic operations, particularly creating new opportunities for labor employment and income growth in rural areas. Through continuously deepening the integration of digital technology with the real economy and advancing digital industrialization, China has achieved sustained expansion of its digital economy. In 2023, the digital economy accounted for 42.8% of GDP [

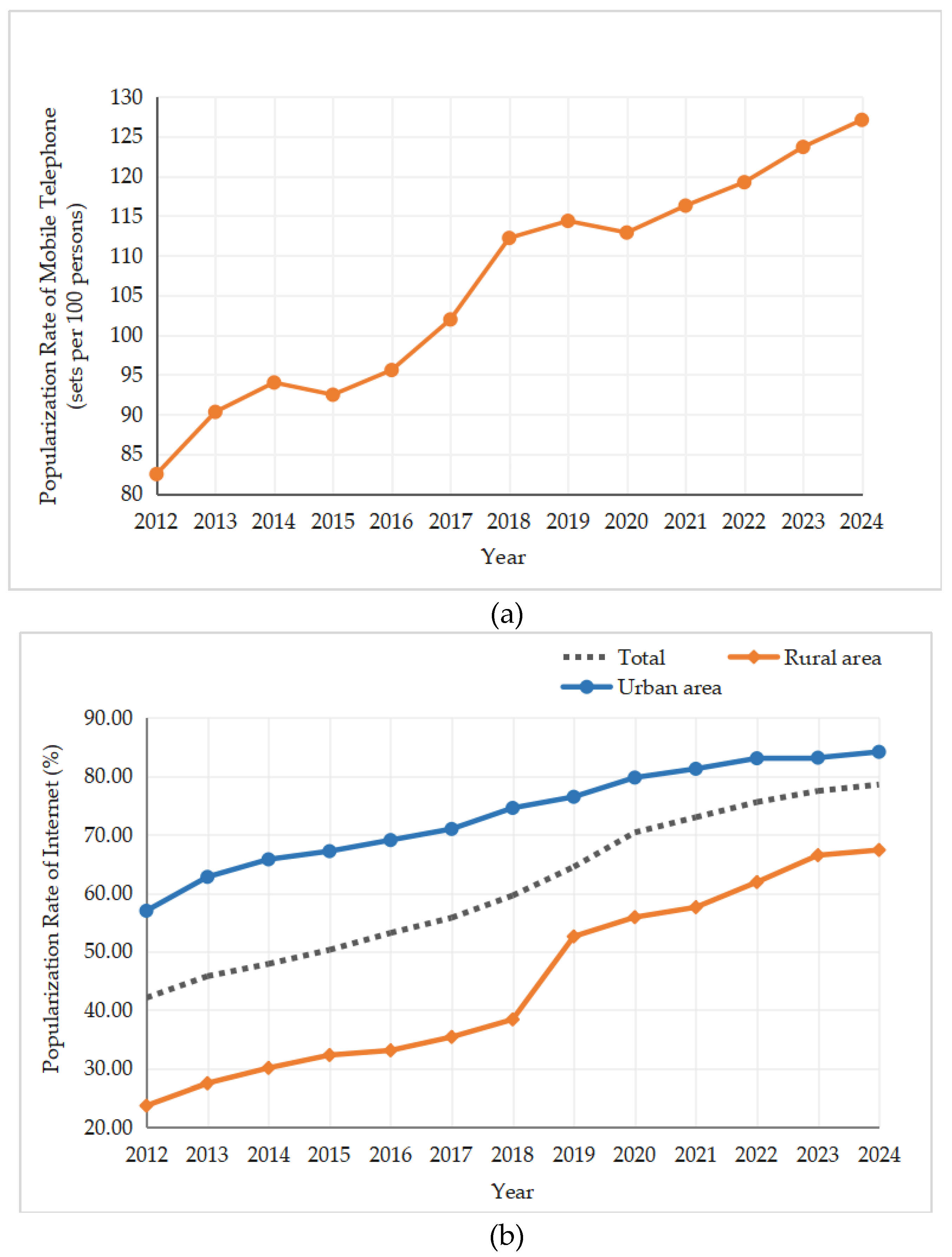

8], providing a strong impetus for the sustained and healthy development of the society. As the foundational support for the digital economy, digital technology infrastructure has achieved leapfrog development. As of 2024, China's mobile phone penetration rate reached 127.1%, with internet penetration at 78.6% [

9]. The Internet penetration rate in rural areas has also reached 67.7%, indicating that the gap between rural and urban digital technology infrastructure has significantly narrowed. The proliferation of digital technology infrastructure has provided rural laborers with increased non-farm employment opportunities. By offering low-cost and low-barrier access to capital accumulation channels, it has enabled their shift to secondary and tertiary industries, thereby enhancing labor market participation. In this context, examining digital technology's impacts on the urban-rural income gap and rural non-farm employment holds significant theoretical and practical importance.

The digital economy constitutes a more advanced economic stage following agricultural and industrial economies. The impact of the digital economy on the urban-rural income gap has attracted significant scholarly attention [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Related research can be mainly divided into three categories: The first perspective argues that the digital economy alleviates the urban-rural income gap by enhancing agricultural productivity and migrant workers' wages [

12,

13]. The narrowing effect is particularly pronounced in regions with more advanced digital infrastructure and greater human capital endowment. Deichmann et al. demonstrated in developing countries that information and communication technology promotes farmers' entrepreneurship by reducing transaction costs [

14]. Yin et al. pointed out that the prosperity of e-commerce has played a positive role in narrowing the urban-rural income gap [

15]. The second perspective posits that digital economic development stimulates urban economic growth, thereby indirectly widening the disparity [

16]. The authors in [

17] and [

18] also indicate that the application of digital technology is often accompanied by technological barriers, disproportionately preventing rural areas from fully benefiting from the digital economy and thereby widening the income gap. The third perspective posits an inverted U-shaped relationship between the digital economy and the urban-rural income gap [

19,

20]. Simon et al. pointed out that in the early stages of economic development, income distribution tends to deteriorate initially, then gradually improves with sustained growth, ultimately achieving relative equity [

21]. This is termed the Kuznets Curve. In summary, the widening income gap primarily stems from inadequate penetration of digital technology in rural areas. Over the long run, as rural digital adoption progresses, the widespread application of new-generation digital technologies (e.g., AI and big data) will further enhance production efficiency and optimize resource allocation, thereby contributing to narrowing the urban-rural income gap.

Non-farm employment is recognized as a pivotal pathway for narrowing the urban-rural income gap. The literature [

22] has found that such employment not only directly increases farmers' income but also generates positive redistributive effects on neighboring regions through spatial spillover mechanisms. Research [

23] has demonstrated that digital finance development enhances financing accessibility for rural entrepreneurs, stimulating entrepreneurial activities that thereby drive non-farm employment expansion. Digital infrastructure development is the cornerstone of the digital economy. Tian et al. demonstrated that broadband network penetration significantly boosts county-level employment rates [

24]. Atasoy et al. analyzed the U.S. data, revealing that broadband internet access increased employment by 1.8 percentage points, with amplified effects in rural and remote areas [

25]. Wang et al. constructed a theoretical model elucidating the underlying mechanisms through which internet adoption promotes rural labor transition to non-farm employment, showing a 7.9 percentage points increase in non-farm employment probability among internet-using rural workers [

26]. The digital technology facilitates rural non-farm employment through multiple channels. Firstly, the information acquisition channel enables rural laborers to access real-time urban labor market dynamics via internet penetration, thereby enhancing their job search capabilities and employment success rates [

26,

27]. Secondly, the skill enhancement channel provides skills training and educational opportunities, which strengthen rural workers' competitiveness and enable them to secure higher-paying positions [

23]. Jiang et al. analyzed the impact of the digital economy on urban-rural income disparities, identifying human capital as a moderating variable that positively regulates this relationship [

28]. Additionally, digital technology alleviates employment pressures in traditional sectors while driving industrial upgrading and occupational diversification [

24].

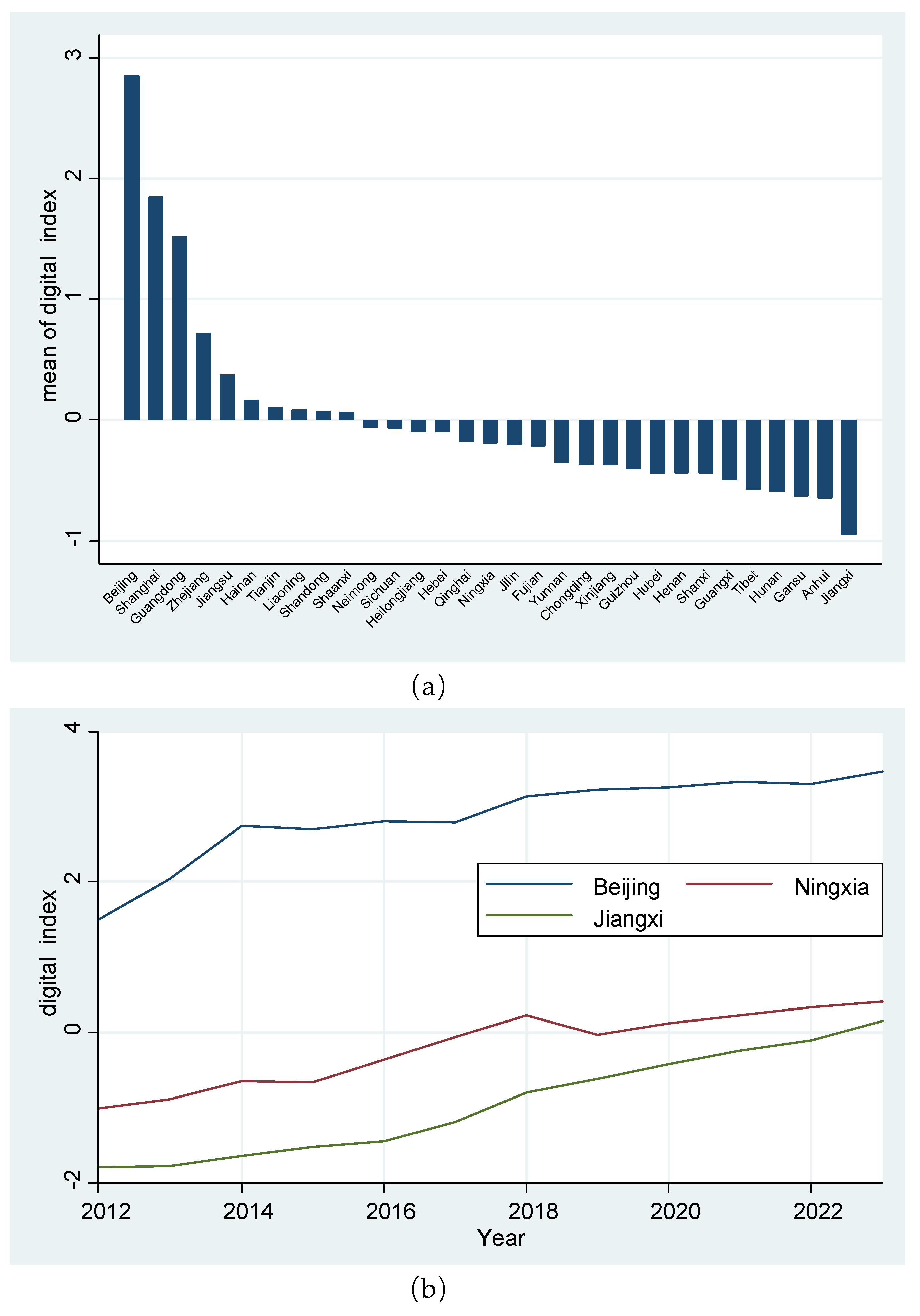

Overall, existing studies on the impact of digital technology on income gap mostly focus on changes since the reform and opening up, covering a longer period of time. At the same time, their characterization of digital technology development remains incomplete, often relying solely on internet penetration rates. Additionally, empirical studies rigorously assessing digital technology's impact on non-farm employment are relatively scarce. In contrast, this study focuses on data from 2012 to 2024 (the new period), during which China's rural digital technology infrastructure has undergone rapid development. This study establishes macro-level digital technology evaluation criteria, deriving more objective indicators through principal component analysis (PCA). Moreover, empirical validation employs micro-level China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data, while incorporating a comprehensive assessment of digital technology across both mobile and desktop platforms. The main contributions can be summarized as follows:

(1) A more comprehensive digital technology development indicator system is established. Macro-level data are analyzed via PCA to assess digital advancement, while micro-level technology accessibility is systematically evaluated across both mobile and desktop platforms.

(2) A regression model between digital technology and income gap is constructed, along with mediating effect model linking digital technology to non-farm employment. A dual-channel mediation mechanism (information acquisition and skill enhancement) is proposed, revealing digital technology's role as an enabling tool in transforming rural employment patterns, thereby establishing transmission mechanisms that narrow income gaps.

(3) An integrated macro-micro analysis is conducted by combining provincial panel data (macro) with individual CFPS data (micro), revealing digital technology’s multi-level impacts on income gap and non-farm employment.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents an in-depth analysis of digital technology development, based on which two research questions are formulated.

Section 3 offers the research assumptions based on the analysis of the current situation of urban-rural income gap and non-farm employment. In

Section 4, analytical models are established to examine the impacts of digital technology on income gap and non-farm employment.

Section 5 details the empirical data processing and analysis. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper, offers theoretical and managerial implications and suggests directions for future research.

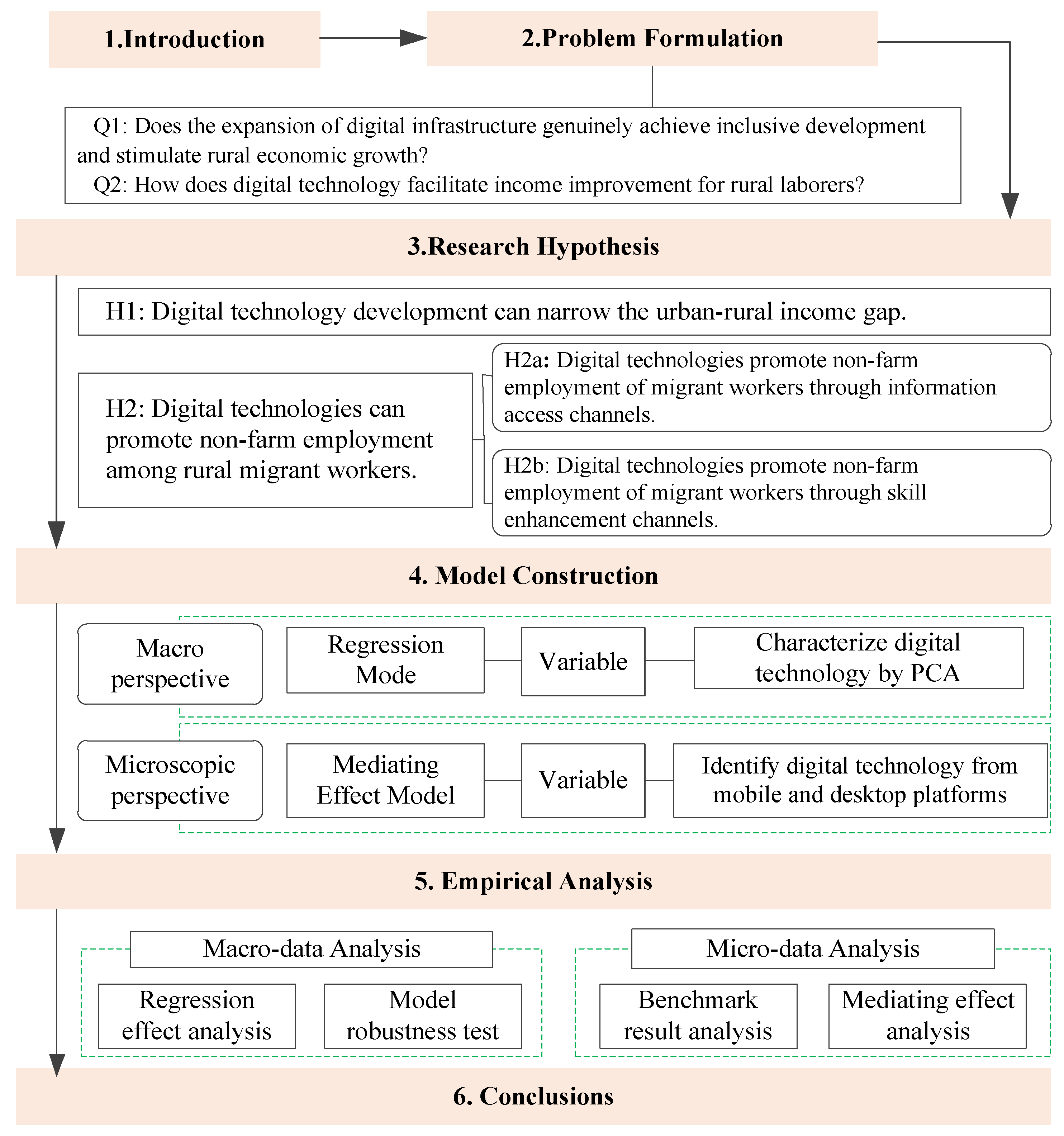

Following is the research framework of this study, as shown in

Figure 1.

2. Problem Formulation

Digital technology and digital economy represent the forefront of current global technological and industrial revolutions. Digital economy is a more advanced economic stage following agricultural and industrial economies [

29].

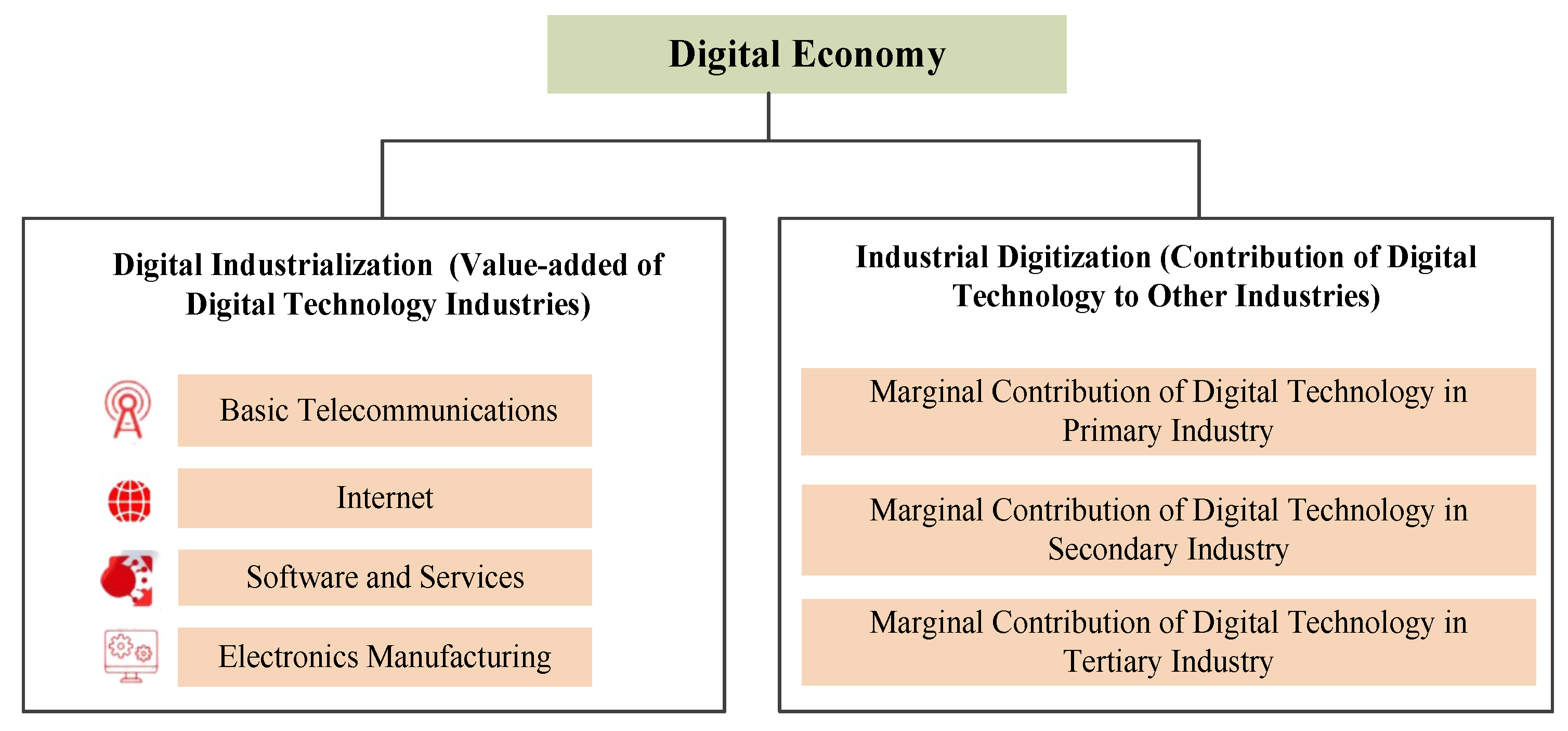

Figure 2 illustrates the composition of the digital economy. Digital economy can be categorized into digital industrialization and industrial digitization. For a long time, China has persistently facilitated the deep integration of digital technology with the real economy. The continuous development of both digital industrialization and the digital economy has provided strong impetus for the sustained and healthy development of the society.

According to continuous tracking research by the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT), China's digital economy has entered an accelerated development stage since 2012. Its scale has expanded from 11.2 trillion yuan in 2012 to 53.9 trillion yuan in 2023, with its proportion of GDP exceeding 42.8%. The contribution rate of digital technology to economic growth has consistently risen to over 66%. It serves as both a critical pillar and an essential driving force for the national economy [

8].

Serving as the foundational support for the digital economy, digital infrastructure has also achieved leapfrog development across domains. During the 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016-2020), China has further promoted the development of the digital economy. The digital infrastructure has been continuously improved. Moreover, the cultivation of emerging formats and innovative models has been accelerated. These developments have achieved positive results in promoting digital industrialization and industrial digitization.

In 2020, China constructed the world's largest fiber-optic and fourth-generation (4G) mobile communication network. The construction and application of fifth-generation (5G) mobile communication networks have also been accelerated. This has significantly increased the penetration rate of broadband users, with fiber-optic subscribers exceeding 94% of total users, mobile broadband penetration reaching 108%, and active Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) users attaining 460 million. The 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Digital Economy also points out that it is necessary to accelerate the construction of information network infrastructure and build intelligent, comprehensive digital infrastructure.

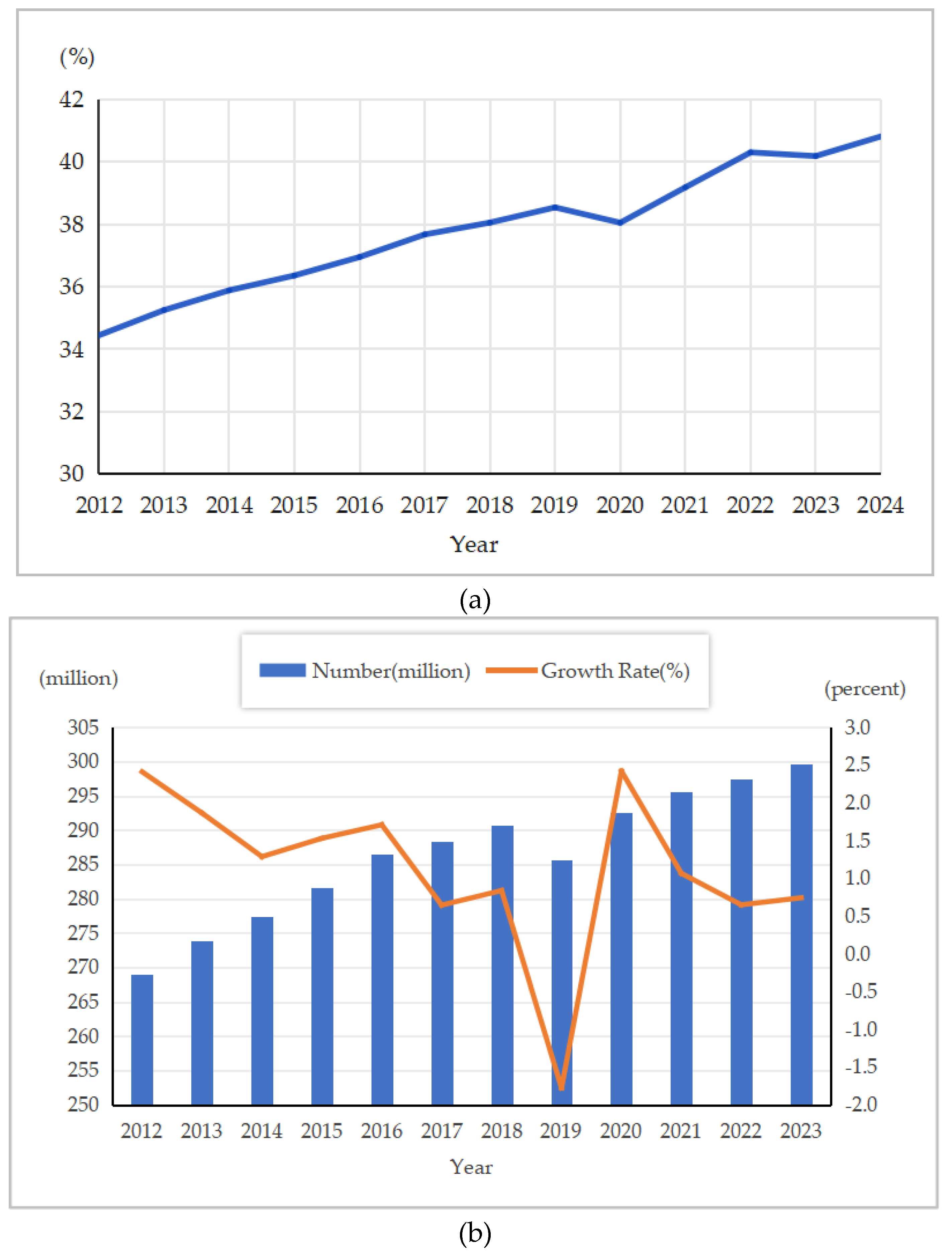

Figure 3(a) shows the penetration rate of mobile phones in China since 2012. It demonstrates a significant upward trend that has become particularly pronounced with year-by-year increases after 2020.

Figure 3(b) presents the internet penetration rates in China's urban and rural areas. As shown in Figure 3(b), the rural internet penetration rate has been continuously increasing with a rapid growth rate, while the gap between rural and urban internet penetration rates is gradually narrowing. Between 2018 to 2019, there was a notable increase in the rural internet penetration rate, with the growth rate reaching as high as 37%. It is evident that China's digital infrastructure is currently developing rapidly. With a strong emphasis on balanced development across regions, the disparity between rural and urban areas continues to diminish. The rapid advancement of digital technology has enabled residents in impoverished regions to gain access to shared digital dividends, thereby laying the foundation for comprehensively advancing digital rural development.

Behind this technology-driven growth, two critical research questions are emerging:

Question 1 (Q1):

Does the expansion of digital infrastructure genuinely achieve inclusive development and stimulate rural economic growth?

Question 2 (Q2):

How does digital technology facilitate income improvement for rural laborers?

For Q1, this paper adopts the urban-rural income gap as the dependent variable and uses digital technology infrastructure development as the independent variable to analyze its impact on the urban-rural income disparity. For Q2, this paper investigates the micro-individual level by targeting the rural labor force as research subjects. It analyzes how digital technology development facilitates rural laborers' non-farm employment through two channels - information acquisition and skill enhancement - thereby increasing personal income.

3. Research Hypothesis

3.1. The Impact Mechanism of Digital Technology on Income Gap

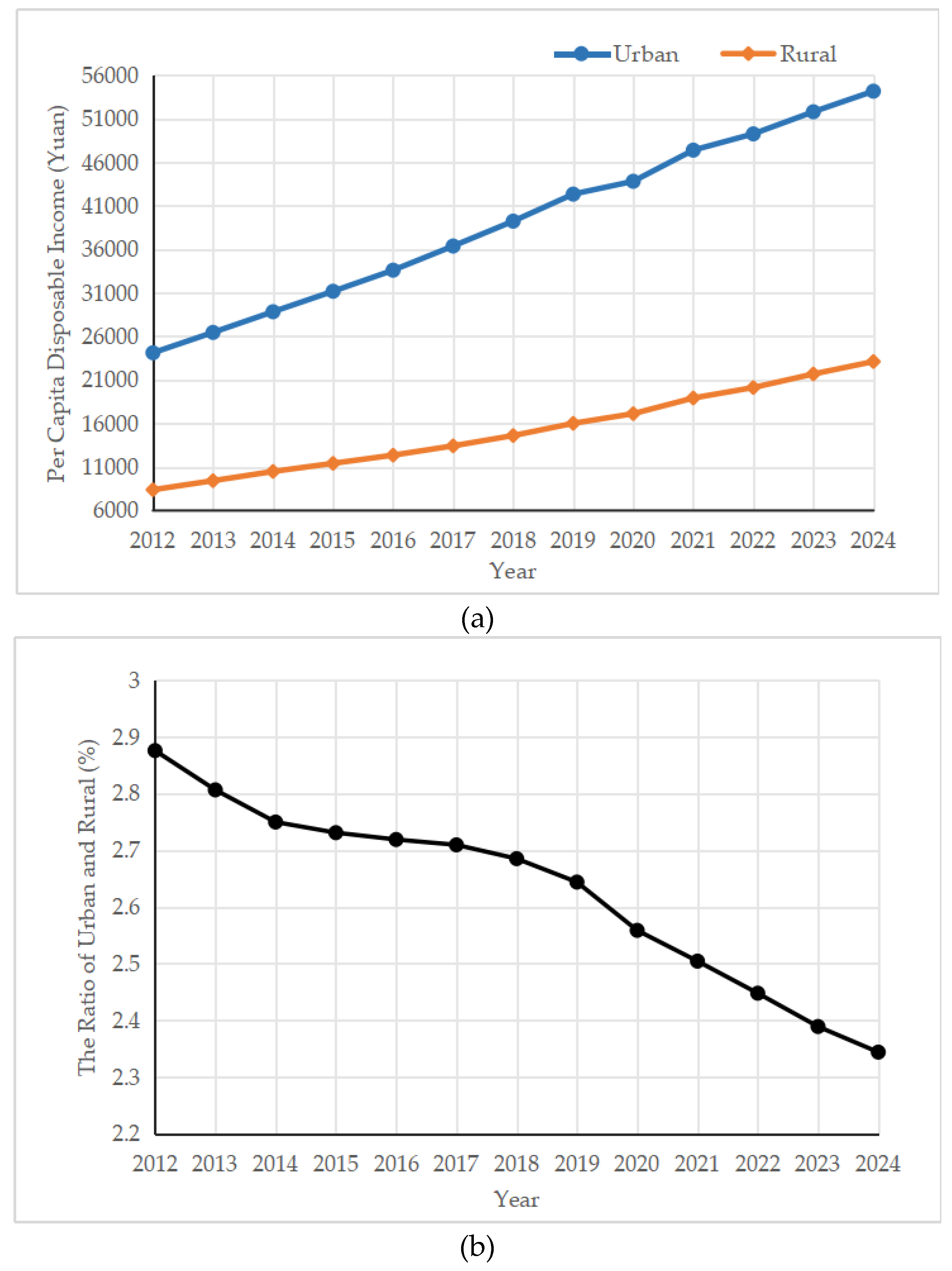

Figure 4 presents the per capita disposable income (PCDI) for urban and rural residents and their ratio from 2012 to 2024 in China. From

Figure 4(a), both urban and rural PCDI have demonstrated consistent annual growth, reflecting a long-term improvement in living standards.

Figure 4(b) reveals a decline in the urban-rural income ratio from 2.88 in 2012 to 2.34 in 2024. It signifies a progressive reduction in regional income inequality and underscores the substantive achievements in balanced interregional development.

Further,

Table 1 presents the PCDI of urban and rural households by income quintile in 2024. The income ratio of PCDI of highest 20% households between urban and rural approximates 2.11. The PCDI of lowest 20% households between urban and rural reaches 3.33. Regionally, the income disparity of rural highest 20% households and the rural lowest 20% households reveal a 9.95-fold gap. The income disparity of urban highest 20% households and the urban lowest 20% households reveal a 6.32-fold gap. Particularly, the ratio of PCDI between the urban highest 20% households and the rural lowest 20% households reaches about 21.03 times. This demonstrates that significant income disparities persist both within urban areas and rural communities, with rural income inequality being particularly pronounced.

In summary, while the urban-rural income gap has been narrowing annually, disparities between high- and low-income groups remain substantial within both urban and rural areas. The chronic low-income levels among the rural low-income population play a critical factor in urban-rural inequality. Improving the income of rural low-income groups constitutes both the key challenge and priority for promoting balanced development in the future.

It is worth studying whether digital technology is able to serve as a pivotal instrument to resolve this structural stagnation, increase rural residents' income and narrow the urban-rural income gap. With the continuous development of digital technology, digital dividends may gradually shift toward rural areas, thereby narrowing the urban-rural income gap. Theoretically, digital technology development can reduce costs in the real economy and improve efficiency, while simultaneously promoting precise supply-demand matching. Firstly, digital technology decreases information acquisition costs. Digital technology changes the traditional information acquisition methods and substantially reduces expenses for obtaining relevant information. Secondly, it significantly reduces resource matching costs. By bridging online and offline spaces, digital technology can address information asymmetry among urban-rural workers. It greatly reduces the costs of resource discovery, contract signing, and supervision and implementation.

As summarized in

Section 1, existing research indicates that digital technology expansion may exacerbate such gaps during initial phases, yet technological maturation and institutional refinement progressively narrow these disparities over time. The primary cause of widening income disparities lies in accessibility differences of workers to digital technology. Given that the gradual increase in rural internet penetration rates in China is approaching urban internet penetration levels, the widening effect is expected to diminish progressively. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Digital technology development can narrow the urban-rural income gap.

3.2. The Impact Mechanism of Digital Technology on Rural Labor Non-Farm Employment

China's economic structure is characterized by a distinct urban-rural dual system [

30]. In this structure, non-farm employment demonstrates significantly higher economic returns compared to agricultural employment. This structural divide is widely regarded as the root cause of the persistent urban-rural income gap. Rural household incomes, for instance, are predominantly composed of two sources: income from off-farm labor and agricultural production. With the advancement of agricultural modernization, a substantial rural labor force has been released from agricultural production. In pursuit of higher wages, these workers progressively transition from agriculture to secondary and tertiary industries, entering non-farm employment sectors. Massive research demonstrates that non-farm employment has made significant contributions to China's economic development [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Rural laborers' participation in non-farm employment is a crucial pathway to narrowing income disparities.

Rural Labor Force refers to individuals with household registration in rural areas, aged 16 and above (excluding students currently enrolled in formal education), who are physically capable of working [

32]. They are counted in the statistics whether currently working (farm/non-farm) or temporarily unemployed but still able to work. Rural Migrant Workers denote laborers who retain rural household registration and engage in non-farm industries locally or work outside their hometown for six months or longer in a year. As defined, Rural Migrant Workers are those engaged in agricultural activities locally or participated in non-farm employment outside their hometown. As a product of the urban-rural dual system, Rural Migrant Workers represent a special group transitioning from rural areas to urban sectors or non-farm industries. They play a pivotal role in rural revitalization, economic stability, and narrowing the urban-rural income gap [

31].

Based on annual data from China's National Bureau of Statistics and the Migrant Worker Monitoring and Survey Report [

32], as shown in

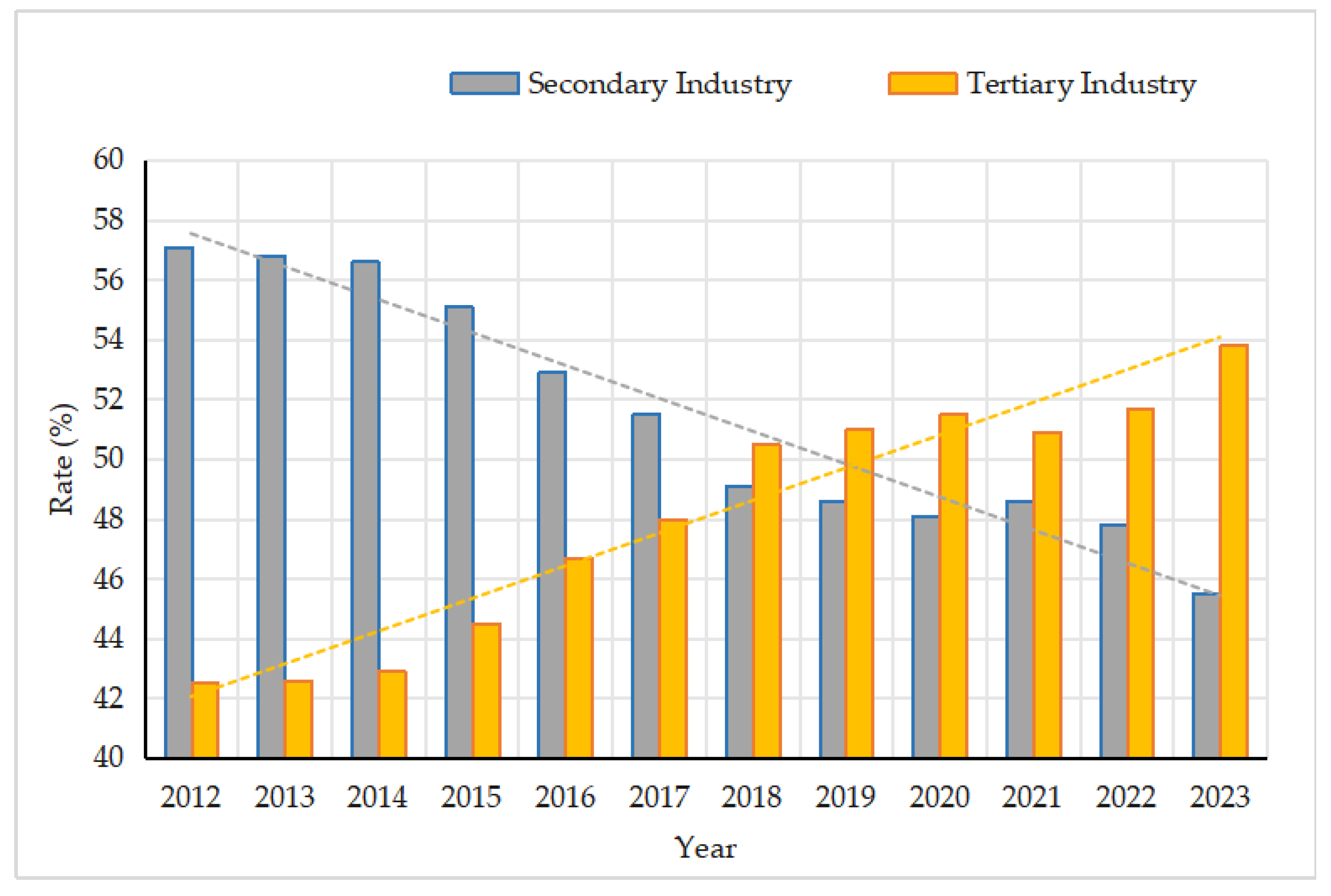

Figure 5(a), the proportion of rural migrant workers in China's total employed population from 2012 to 2024 are calculated. Clearly, this proportion has demonstrated a persistent upward trend, indicating that rural migrant workers are playing an increasingly vital role in China's economic development.

Furthermore,

Figure 5(b) shows the number of rural migrant workers and their annual growth rates. Additionally, the paper counted the proportion of rural migrant workers in secondary and tertiary industries from 2012 to 2023 (data for 2024 remains unpublished), with results displayed in

Figure 6.

From

Figure 5 and 6, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) The total number of migrant workers has been increasing and has a rising share of total employment. Under agricultural modernization, a sea of rural laborers has been liberated from agricultural production. In 2024, the migrant worker population reached 299.73 million in China. Accounting for 40.8% of total employment, their contribution to economic growth becomes increasingly significant. Except for a notable decline in 2020 (primarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic leading to widespread production halts and the return of migrant workers to agricultural activities), the total number of migrant workers has maintained a continuous upward trend.

(2) The proportion of migrant workers in the tertiary industry continues to rise. From an industrial perspective, massive rural surplus laborers engage in non-farm employment and transition to the secondary and tertiary industries. In 2023, 45.5% of migrant workers were employed in the secondary industry, and 53.8% worked in the tertiary industry. From 2012 to 2023, employment in the secondary industry consistently declined. In contrast, employment in the tertiary industry steadily increased and surpassed the former as early as 2018.

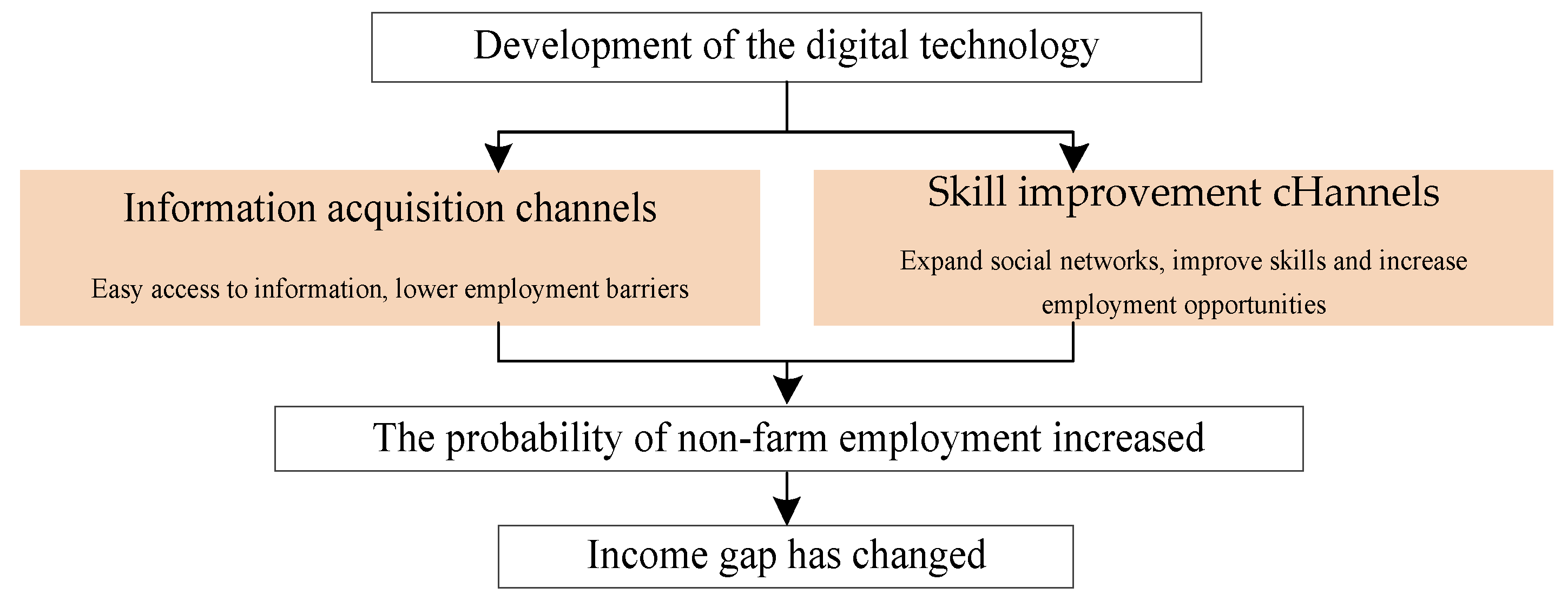

For individuals, digital technology promotes non-farm employment through two primary ways, as illustrated in

Figure 7. On the one hand, digital technology can enhance non-farm employment via improved information access. When digital technology is underdeveloped, many migrant workers have to seek employment through informal channels. It makes them vulnerable to deception and difficult to secure appropriate employment opportunities. However, the development of digital technology facilitates information dissemination and communication. It significantly removes the information barrier and information asymmetry in the labor market. This beneficial influence not only helps rural laborers to find abundant employment opportunities and understand labor market demands, but also motivates rural laborers to engage in non-farm employment and expands their access to information sources. On the other hand, digital technology enhances non-farm employment opportunities through increasing skill acquisition channels. Rural workers can acquire employment skills via digital technology, consequently improving their employability. Furthermore, they can engage in emerging employment models such as e-commerce entrepreneurship, online live-streaming, and short video production. Enhancing rural residents' digital skills and comprehensive competencies not only strengthens their adaptability to technological innovations but also elevates their employability in the digital economy era.

As evidenced above, it can be inferred that the development of inclusive digital infrastructure has provided rural workers with enhanced non-farm employment opportunities. Information access channels and skill acquisition channels constitute the key mechanisms through which digital technology application facilitates employment among migrant workers. By promoting non-farm employment through information acquisition and skill enhancement channels, digital technologies contribute to narrowing income gaps indirectly. Based on this, this study proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Digital technologies can promote non-farm employment among rural migrant workers.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a):

Digital technologies promote non-farm employment of migrant workers through information acquisition channels.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b):

Digital technologies promote non-farm employment of migrant workers through skill enhancement channels.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Findings

The persistent urban-rural income gap continues to hinder China's sustainable development and common prosperity goals. Promoting non-farm employment among rural laborers is pivotal to narrowing the urban-rural income gap. Digital technology provides relatively convenient channels for information acquisition and skill enhancement, enabling rural laborers to better participate in the labor market. First, from a macro-level perspective, the effects of digital technology advancement are empirically examined in relation to the urban-rural income gap. Second, from a micro-level perspective, the intrinsic mechanisms are explored by which rural laborers' participation in non-farm employment is facilitated through digital technology. The regression model between digital technology and income gap is constructed, along with a mediating effect model linking digital technology to non-farm employment. Panel data from 31 provinces and the CFPS data are utilized. Based on the analysis carried out in this article, we can get the following conclusions.

Digital technology plays a positive role in narrowing the income gap. The income gap will be reduced by about 11.9% for each unit of digital technology.

Digital technology significantly promotes non-agricultural employment. For individuals with average characteristics, the use of digital technology can increase the probability of non-farm employment by 20.13%.

Digital technologies promote non-farm employment through information acquisition channels. The use of digital technologies indirectly contributes to non-farm employment by approximately 2.26% through the information acquisition channel.

Digital technologies promote non-farm employment through skill enhancement channels. Digital technology usage indirectly contributes to non-farm employment by approximately 6.91% through the skill enhancement channel. Skill enhancement channels exert effects 1.7 times stronger than information acquisition channels in promoting non-farm employment.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the above findings, it is imperative to vigorously promote the adoption of digital technologies in rural areas. This study proposes the following policy optimization pathways:

Digital infrastructure enhancement. Priority should be given to deploying gigabit optical networks and 5G base stations in rural regions, with a focus on establishing county-level digital hubs. A dynamic monitoring mechanism should be implemented to ensure infrastructure coverage meets predefined benchmarks. Integrating digital infrastructure development into the rural revitalization evaluation system will align construction priorities with local employment demands.

Skill-oriented digital training systems. A nationwide digital skills certification and training network targeting rural laborers should be established. Through township government-university-enterprise tripartite partnerships, diversified vocational skills training programs should be offered for rural workers. Upon completion of training and certification, corresponding employment recruitment information should be systematically disseminated to workers. These digital training systems must integrate skill certification levels with wage scales to amplify the employment-promotion effects of skill enhancement channels.

Inclusive information infrastructure development. Standardized village-level digital information service centers must be constructed, integrating job posting dissemination and remote interview functionalities. Algorithmic regulation should be enforced to mitigate information bias in platform recommendations, thereby strengthening the foundational role of information acquisition channels.

Employment service optimization. An intelligent township level job matching system should be developed by aggregating data from leading recruitment platforms, using machine learning to improve recommendation accuracy. Algorithmic regulation should be enforced to mitigate platform recommendation bias, strengthening information acquisition channels. Targeted support should be provided to digital agriculture and rural e-commerce, coupled with a cross-regional coordination mechanism to balance labor demand across eastern, central, and western China.

Non-farm employment of the rural labor force is a key driver for rural development. In the context of advancing digital technology, it is essential to systematically integrate digital solutions with rural construction at multiple levels, building a digital countryside in the new era of socialism. Thereby, common prosperity can be effectively advanced. We believe that non-farm employment is a promising direction of further research in this area. Therefore, future work will aim to investigate the impact of the aforementioned policies on non-farm employment.