Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digitalization and Labor Market Adjustment

2.2. Informality and Structural Constraints

2.3. Youth Labor Market Exclusion and NEET Patterns

2.4. Institutional Response and Labor Policy Adaptation

2.5. Identified Gaps and Analytical Positioning

3. Methodology

4. Results

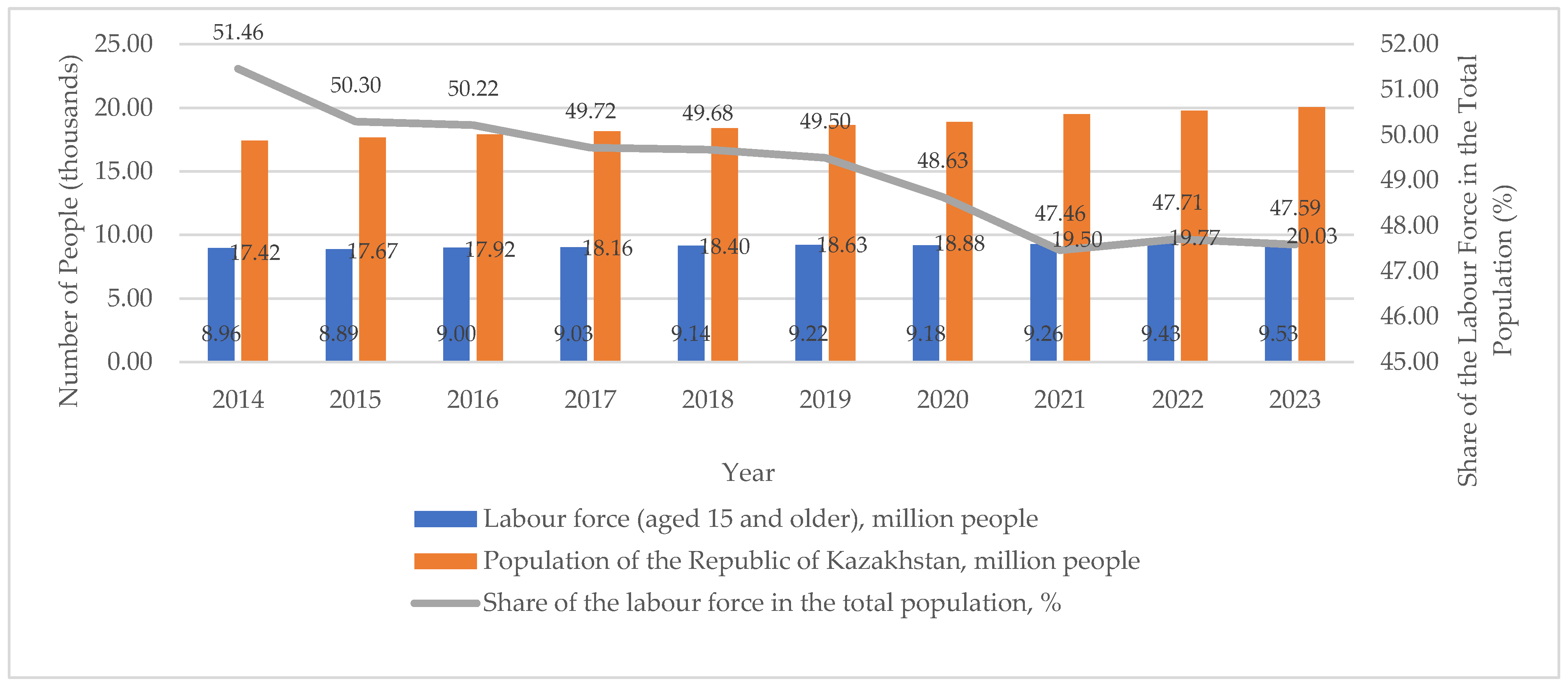

4.1. Structural Features and Transformational Trends of Kazakhstan’s Labor Market

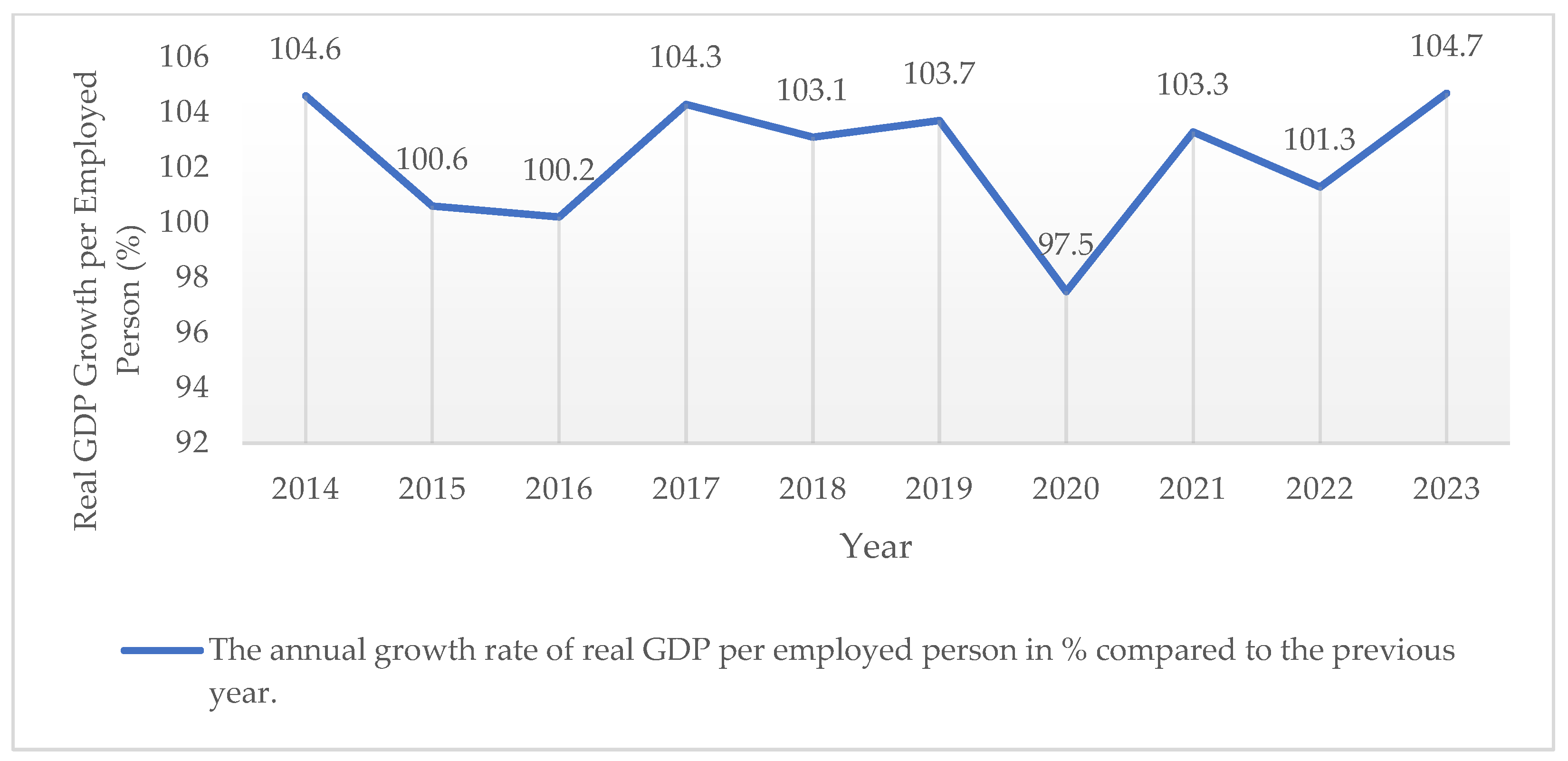

- Yit—the growth rate of real GDP per employed person in region i in year t;

- ICTit—the level of digitalization (the percentage of households with internet access);

- TECHit—the share of employment in high-tech industries;

- EDUit—the public expenditure on education (as a percentage of gross regional product);

- RESit—the share of employment in the resource sector;

- URBit—the level of urbanization (the share of urban population);

- εit—the stochastic error term capturing the influence of unobserved factors.

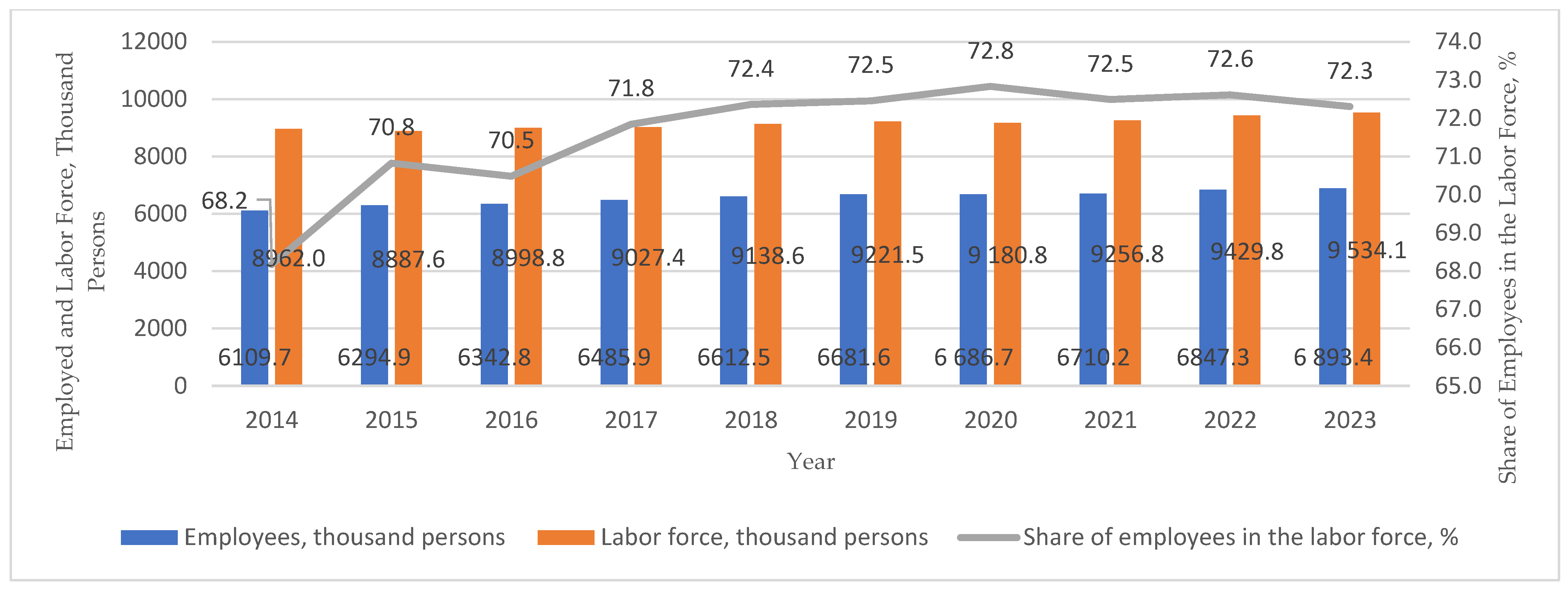

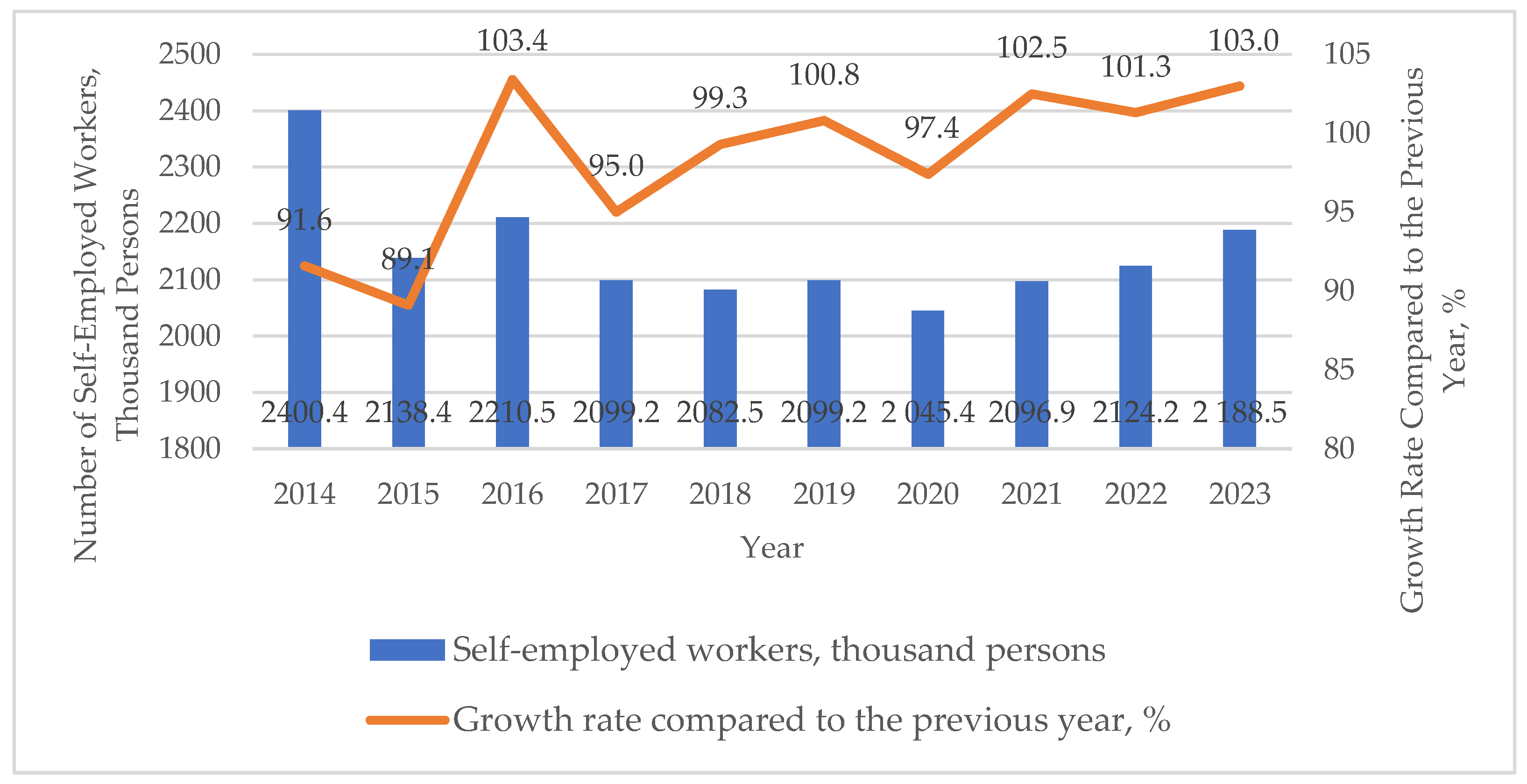

4.2. Structural Shifts and Empirical Assessment of Employment Dynamics in Kazakhstan (2014–2023)

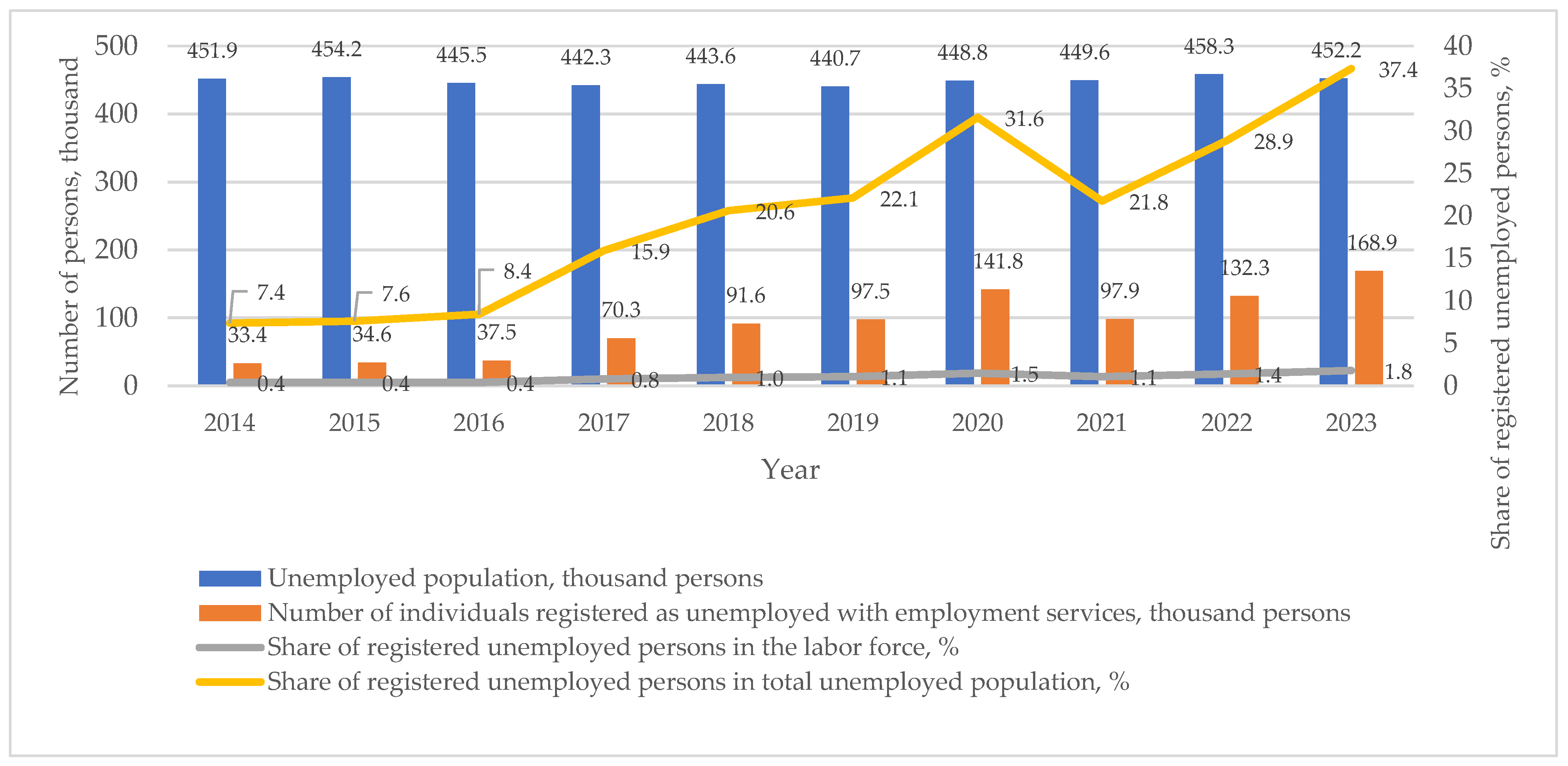

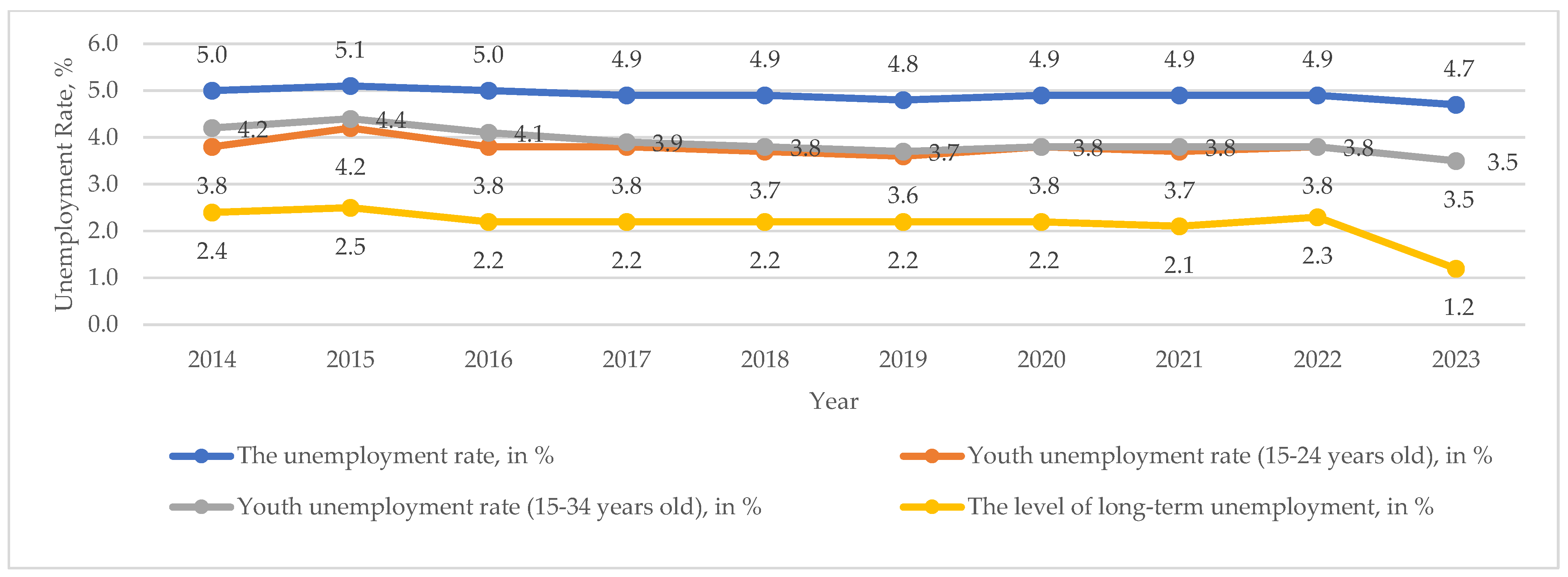

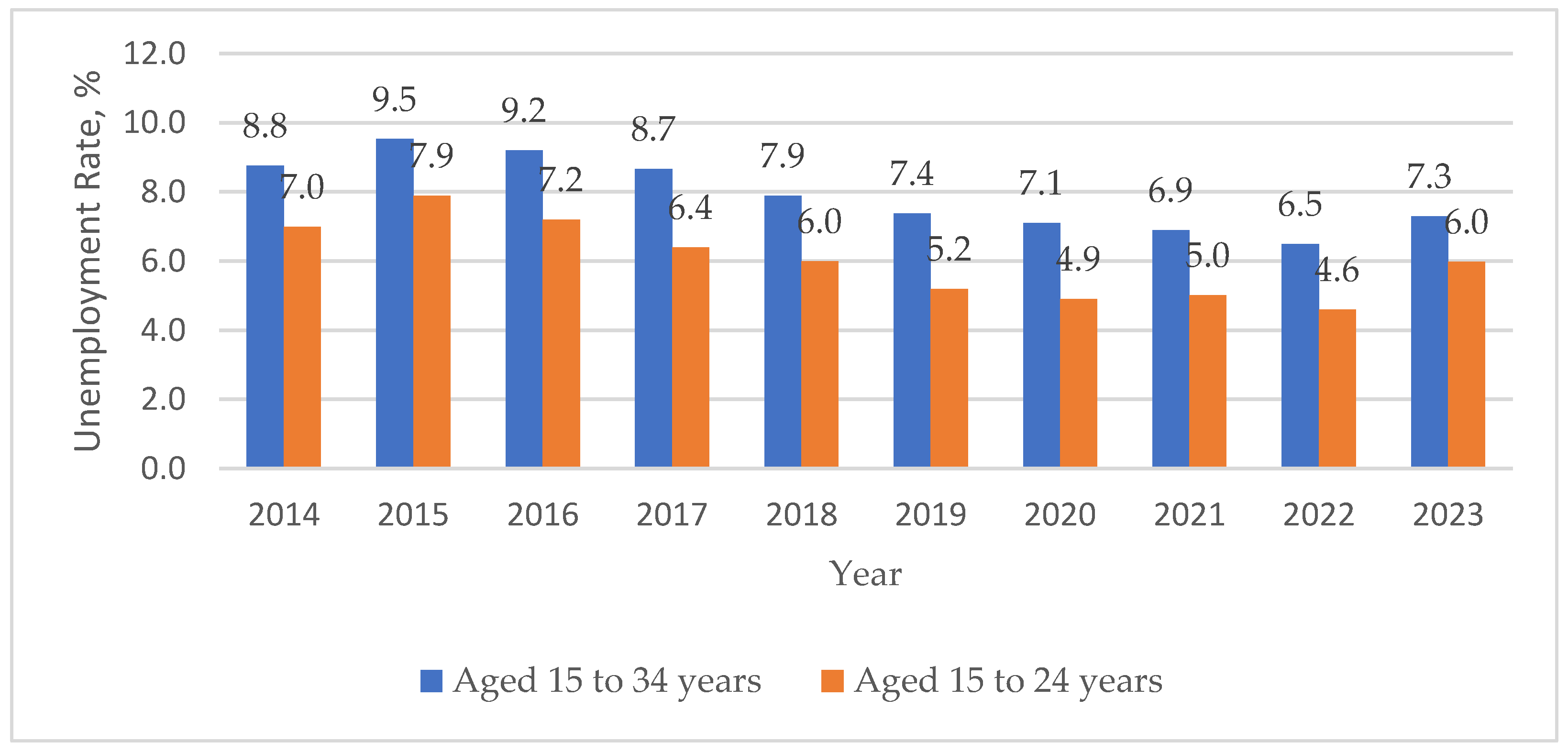

4.3. Unemployment Dynamics and Labor Market Vulnerabilities

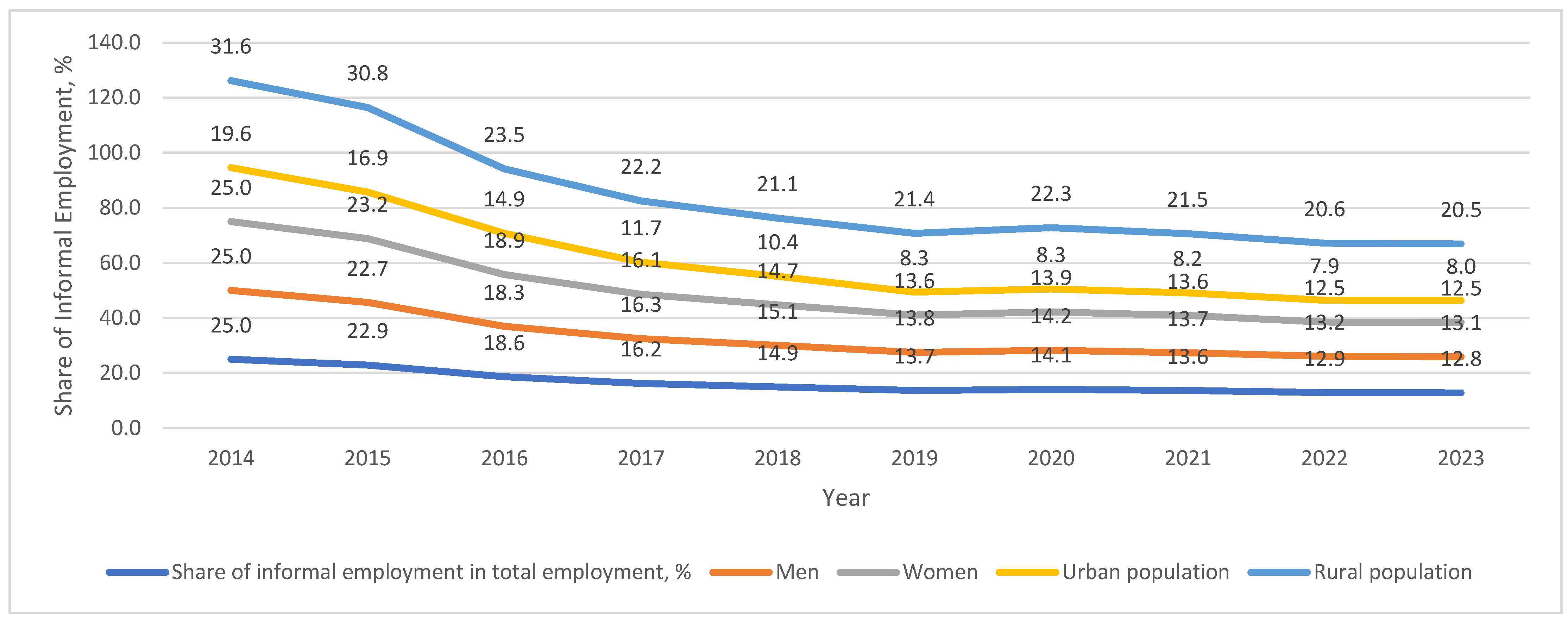

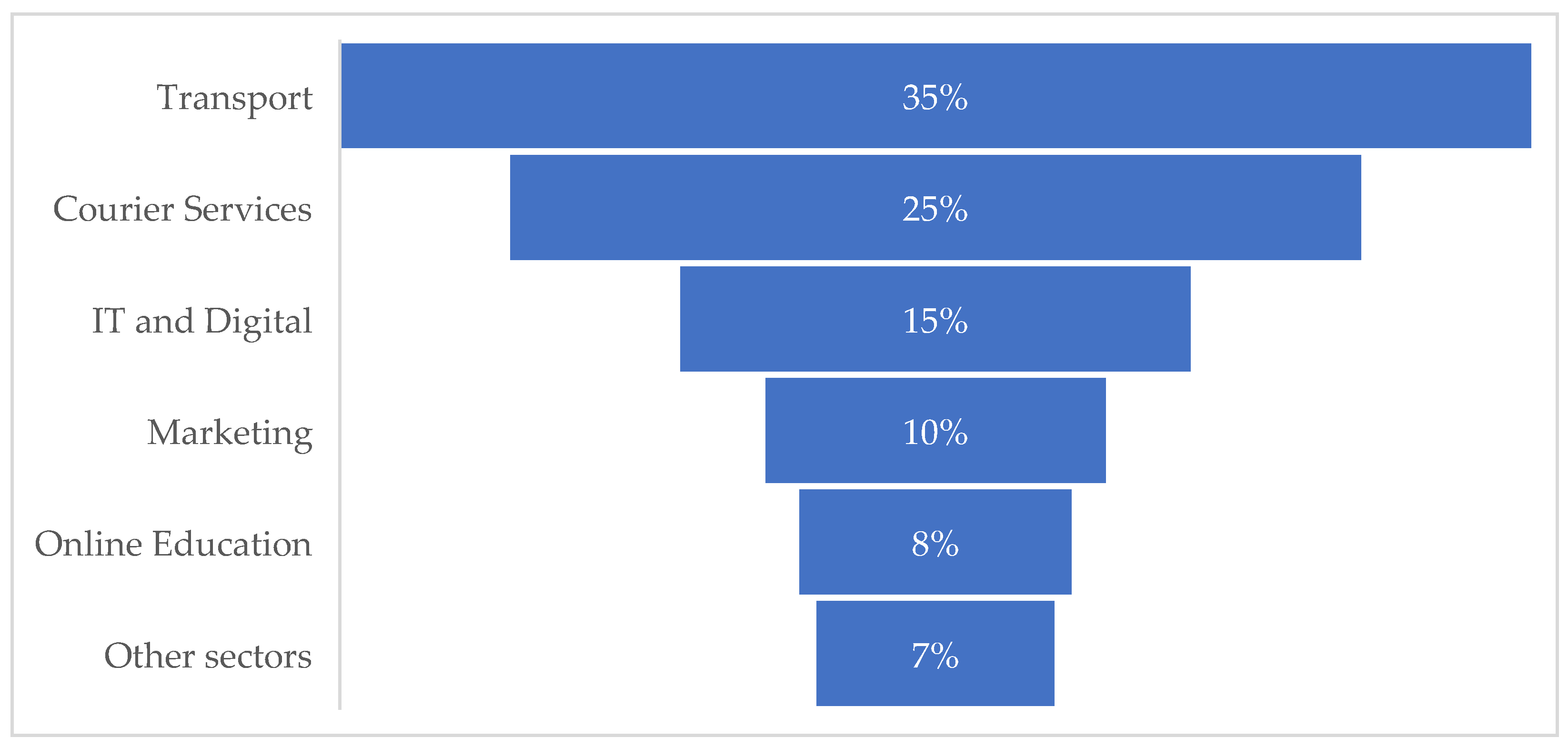

4.4. The Informal Labor Sector in Kazakhstan: Structure, Trends, and Digital Transition

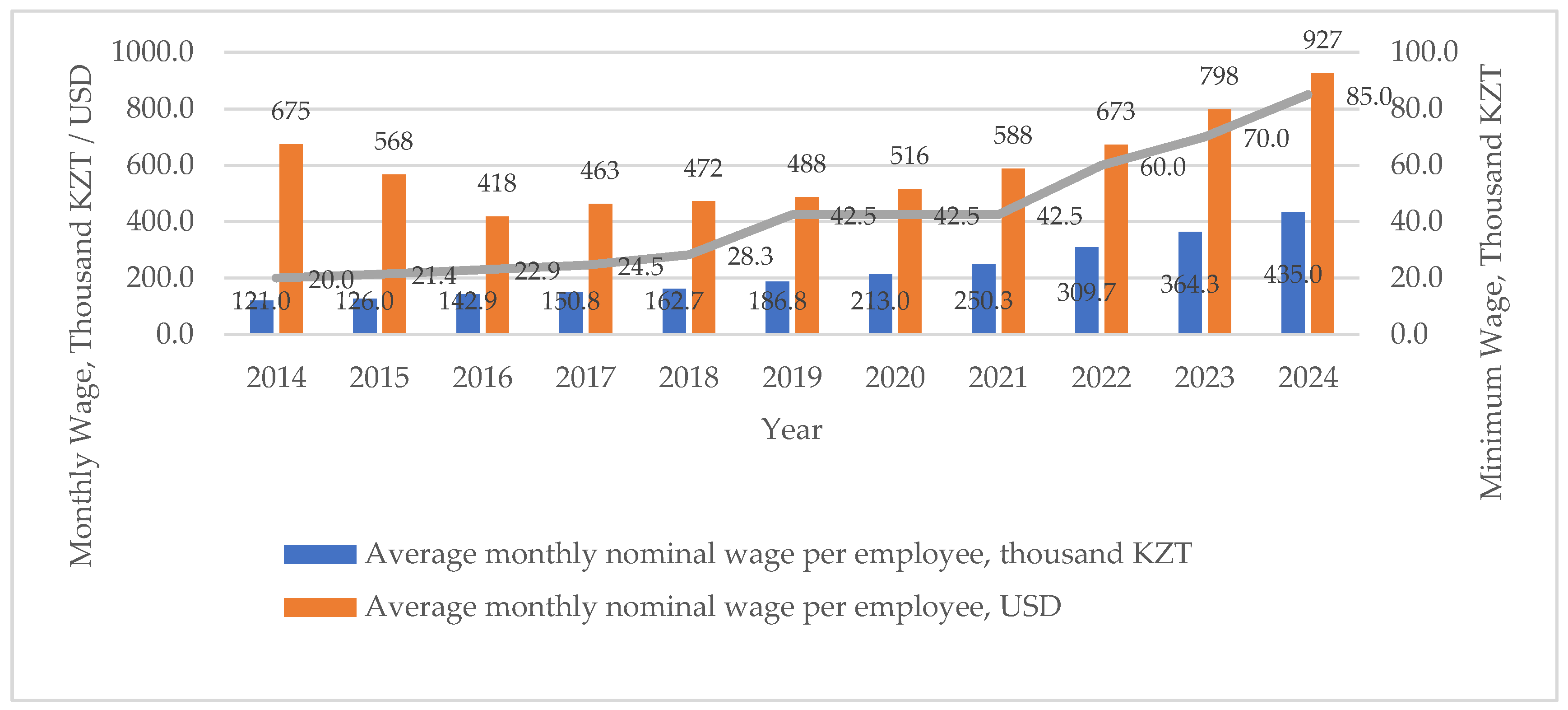

4.5. Empirical Assessment of Wage Dynamics in Kazakhstan (2014–2023)

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

5.1.1. Structural Transformation of the Labor Market

5.1.2. Macroeconomic Drivers of Employment

5.1.3. Formalization and Institutional Constraints

5.1.4. Sectoral Employment Shifts

5.1.5. Unemployment and Youth Vulnerability

5.1.6. Informality and Spatial Inequality

5.1.7. Real Wage Dynamics and Labor Income Determinants

5.2. Broader Implications

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADB | Asian Development Bank Institute |

| GDP | gross domestic product |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| ICT | information and communication technologies |

| NEET | Not in Employment, Education, or Training |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

Appendix A

| Variable | Coefficient (β) | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | Interpretation |

| ICT_Access | 0.452 | 0.148 | 3.05 | 0.004 | Strong positive impact of digital infrastructure |

| Tech_Employment | 0.376 | 0.162 | 2.32 | 0.025 | Technological employment boosts labor productivity |

| Gov_Edu_Spending | 0.237 | 0.130 | 1.82 | 0.075 | Moderate positive effect of public education spending |

| Resource_Dependency | −0.314 | 0.122 | −2.57 | 0.013 | Resource dependence hinders productivity growth |

| Urban_Pop | 0.091 | 0.118 | 0.77 | 0.442 | Statistically insignificant |

| Constant | 99.472 | 2.106 | 47.24 | <0.001 | Baseline growth rate |

| R-squared (R2) | 0.63 | — | — | — | Model explains 63% of variance in dependent variable |

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Variable | Coefficient (β) | Standard Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | Interpretation |

| GDP Growth Rate | 0.39 | 0.145 | 2.69 | 0.028 | Positive impact on employment |

| Real Wage Index | 0.57 | 0.113 | 5.04 | 0.004 | Significant effect on employment growth |

| Constant | −1.12 | 0.514 | −2.18 | 0.056 | Statistically insignificant at 5% level |

| Coefficient of Determination (R2) | 0.69 | — | — | — | Model explains 69% of variation |

Appendix D

Appendix E

| Coefficient | Direction of Impact | Interpretation |

| β1 > 0 | Positive | An increase in total employment contributes to a rise in the share of formal employment, indicating the institutional strengthening of the official sector of the economy. |

| β2 < 0 | Negative | A higher unemployment rate reduces the share of formal employment, possibly reflecting the displacement of workers into informal or temporary employment forms. |

| β3 > 0 | Positive | Growth in the overall labor force positively influences formalization, likely due to demographic factors and the expansion of employment systems. |

Appendix F

| Variable | Coefficient (β) | Standard Error | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Number of Employed Persons | 0.456 | 0.118 | 0.007 | Positive effect on formalization |

| Unemployment Rate | –0.273 | 0.095 | 0.019 | Negative effect |

| Labor Force | 0.364 | 0.134 | 0.022 | Growth in the labor force increases the share of employees |

| Constant | 48.32 | 2.44 | 0.001 | Baseline level |

| R2 | 0.83 | — | — | The model explains 83% of the variance. |

Appendix G

| Indicators | Share of Employees | Number of Employed Persons | Unemployment Rate | Labor Force |

| Share of Employees | 1.00 | 0.93 | −0.88 | 0.90 |

| Number of Employed Persons | 0.93 | 1.00 | −0.86 | 0.92 |

| Unemployment Rate | −0.88 | −0.86 | 1.00 | −0.82 |

| Labor Force | 0.90 | 0.92 | −0.82 | 1.00 |

Appendix H

Appendix I

| Indicators | Unemployment Rate (%) | Youth (15–34), % | Youth (15–24), % | Long-term Unemployment, % | Registered Unemployed Persons, thousand |

| Unemployment Rate (%) | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.81 | −0.82 |

| Youth (15–34), % | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.73 | −0.88 |

| Youth (15–24), % | 0.90 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.71 | −0.62 |

| Long-term Unemployment, % | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 1.00 | −0.68 |

| Registered Unemployed Persons, thousand | −0.82 | −0.88 | −0.62 | −0.68 | 1.00 |

Appendix J

| Indicator | Nominal Wage | Nominal Wage Index | Real Wage Index | Minimum Wage |

| Nominal Wage | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.95 |

| Nominal Wage Index | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.84 |

| Real Wage Index | 0.82 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.78 |

| Minimum Wage | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 1.00 |

Appendix K

| Variable | Coefficient (β) | Standard Error | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Nominal Wage | 0.000082 | 0.00003 | 0.014 | Positive effect on real wages |

| Minimum Wage | −0.00051 | 0.00026 | 0.078 | Slightly negative effect on real wages |

| Constant | 95.6 | 0.48 | 0.001 | Baseline level of real wage index |

| R2 | 0.81 | — | — | The model explains 81% of the variance |

Appendix L

| Scenario | Description | Key Indicators (by 2030) | Expected Outcomes |

| Optimistic | Rapid digital infrastructure rollout, effective youth employment strategies, large-scale upskilling, integration of informal workers | NEET rate: ≤4% Informal employment: ≤8% Digital sector employment: ≥10% Remote work share: ≥5% Labor productivity growth: ≥4% annually |

Inclusive labor market growth, regional convergence, reduced informality, and strong integration of youth |

| Pessimistic | Fragmented digitalization, persistent institutional inertia, growing digital divide, ineffective employment policies | NEET rate: ≥10% Informal employment: ≥18% Digital sector employment: ≤5% Remote work share: ≤1% Labor productivity growth: ≤1% annually |

Widening disparities, youth exclusion, stagnant productivity, expansion of precarious employment |

| Optimal (Baseline) | Gradual digital integration, moderate success of targeted employment programs, partial formalization, improvement in urban centers | NEET rate: 6–7% Informal employment: 10–12% Digital sector employment: 6–8% Remote work share: 2–3% Labor productivity growth: 2–3% annually |

Moderate formalization, selective inclusion of youth, persistent rural–urban gaps, partial transition to digital economy |

References

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets. J. Politi- Econ. 2020, 128, 2188–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADB, 2022) ADB. (2022). Kazakhstan Country Diagnostic Study: Toward a More Inclusive and Resilient Labor Market. Asian Development Bank.

- Adilkhanova, 2023) Adilkhanova, Z. (2023). Unemployment rate in Kazakhstan: An alternative calculation (Analytical note No. 2023–02). Monetary Policy Department, National Bank of Kazakhstan.

- Amirgaliyeva & Dosmuratova, 2022) Amirgaliyeva, A., & Dosmuratova, A. (2022). Socioeconomic determinants of NEET youth in the south of Kazakhstan. Bulletin of the Academy of Labor and Social Relations, 3, 77–88.

- Arntz et al., 2016) Arntz, M.; Gregory, T.; Zierahn, U. (2016). The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A Com-parative Analysis. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 189. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/the-risk-of-automation-for-jobs-in-oecd-countries_5jlz9h56dvq7-en (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Arynova, Z.; Shelomentseva, V.; Kaidarova, S.; Zolotareva, S.; Bekniyazova, D. TRENDS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LABOR MARKET IN THE CONTEXT OF DIGITALIZATION OF THE ECONOMY. Bull. 2024, 3, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , 2020) Autor, D., Mindell, D., & Reynolds, E. (2020). The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines. MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future.

- Autor, D.H. Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation. J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson and McAfee, 2014). Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Baimukhanov, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , 2021) Baimukhanov, A., Bekmagambetova, A., & Amangeldina, G. (2021). Digital economy and the transformation of employment in Kazakhstan. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies, 28(4), 389–403. [CrossRef]

- Beisembina, A.; Abuselidze, G.; Nurmaganbetova, B.; Kabakova, G.; Makenova, A.; Nurgaliyeva, A. The Labour Market in Kazakhstan Under Conditions of Active Transformation of Their Economy. Economies 2025, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom & McKenna, 2021) Bloom, D. E., & McKenna, M. J. (2021). The future of work in the age of AI. Harvard Public Health Review, 26, 1–7.

- Kudrle, R.T. Moves and countermoves in the digitization challenges to international taxation. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , 2015) Bonin, H., Gregory, T., & Zierahn, U. (2015). Übertragung der Studie von Frey/Osborne (2013) auf Deutschland. ZEW—Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung GmbH.

- Bowles, 2014) Bowles, J. (2014, July 17). The computerisation of European jobs. Bruegel Blog. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/computerisation-european-jobs (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Bruck & Burke, 2016) Bruck, J., & Burke, I. (2016). The great decoupling: Automation, productivity and inequality. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 32(2), 221–234.

- Bureau of National Statistics of the Kazakhstan, 2024) Bureau of National Statistics of the Kazakhstan. (2024). Structure and distribution of wages of employees in the Kazakhstan (by the end of 2024). Statistical Bulletin. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/en/industries/labor-and-income/stat-wags/publications/184222/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Bureau of National Statistics, 2023) Bureau of National Statistics. (2023). Labor market indicators. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Campos, F.; Frese, M.; Goldstein, M.; Iacovone, L.; Johnson, H.C.; McKenzie, D.; Mensmann, M. Teaching personal initiative beats traditional training in boosting small business in West Africa. Science 2017, 357, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for the Development of Human Resources, 2021) Center for the Development of Human Resources(2021). The national report «The labour market of Kazakhstan: Development in a new reality» Available online:. Available online: https://erdo.enbek.kz/news/414 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Center for the Development of Human Resources, 2022) Center for the Development of Human Resources(2022). The national report «The labour market of Kazakhstan: On the way to digital reality» Available online:. Available online: https://erdo.enbek.kz/news/241 (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Center for the Development of Human Resources, 2023) Center for the Development of Human Resources (2023). The national report «The Future Workforce: Youth in Kazakhstan’s Labor Market» Available online:. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rGYomZ6r6tao9unGHD0RSJpqqZPXCaWL/view (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Dauth et al, 2017) Dauth, W., Findeisen, S., Suedekum, J., & Woessner, N. (2017). German Robots – The Impact of Industrial Robots on Workers (CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP12306). Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://cepr. 1230.

- Eurofound, 2016) Eurofound. (2016). Exploring the diversity of NEETs. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

- European Training Foundation, 2025) European Training Foundation (ETF). New Forms of Work and Platform Work in Central Asia; ETF: Turin, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://www.etf.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/new-forms-work-and-platform-work-central-asia (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Federation of Trade Unions of the Kazakhstan, 2022) Federation of Trade Unions of the Kazakhstan. (2022). Report on Plat-form-Based Employment in Kazakhstan. Kasipodaq.kz. Available online: https://kasipodaq.kz/wp-content/uploads/Отчет-пo-латфoрменнoй-занятoсти-oктябрь-2022.pdf. (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Ford, 2015) Ford, M. (2015). The rise of the robots: Technology and the threat of a jobless future. Basic Books.

- Frey, C.B.; Osborne, M.A. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2023). Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2023). Resolution No. 1050 of 19 December 2023: On Approval of the Concept for the Development of the Labor Market of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2029. (In Kazakh). Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2300001050.

- Graham & Dutton, 2019) Graham, M., & Dutton, W. H. (Eds.). (2019). Society and the Internet: How networks of information and communication are changing our lives (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Gyiazov, A. T. 2025) Gyiazov, A. T. The Impact of Digital Literacy on Kazakhstan’s Employment Structure in the Context of Tech-nological Change. Economy: Strategy and Practice, 20(1), 6–18.

- ILO, 2018) International Labour Organization. (2018). Formalization of the informal economy: Global trends and policy recom-mendations. International Labour Organization.

- ILO, 2020) International Labour Organization. (2020). Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture (3rd ed.); International Labour Organization.

- ILO, 2020) International Labour Organization.(2020). World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020. Geneva: ILO.

- ILO, 2025) International Labour Organization (2025). World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2025; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ILO, 2025) International Labour Organization (2025). Formalizing the Informal Economy: A Roadmap towards Decent Work. Report VI for the 113th Session of the International Labour Conference; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , 2020) Johansson, J., Nafchi, M. Z., & Mohelska, H. (2020). Digital transformation and employment in the EU: Regional effects and policy implications. European Journal of Business Science and Technology, 6(1), 5–18.

- Kakizhanova, T.; Utepkaliyeva, K.; Zeinolla, S.; Aben, A.; Ilyashova, G. Impact of Digitalization, Economic Growth and Birth Rate on Female Labor Force: Evidence from Kazakhstan. ECONOMICS 2025, 13, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenjebayeva & Sagiyeva, 2019) Kenjebayeva, L., & Sagiyeva, R. (2019). Informal employment in Kazakhstan: Gender and regional aspects. Economic Research Kazakhstan, 2(16), 45–53.

- Keynes, 1930) Keynes, J.M. (1930). Economic possibilities for our grandchildren. In Essays in Persuasion. Macmillan.

- Khussainova, Z.; Gazizova, M.; Abauova, G.; Zhartay, Z.; Raikhanova, G. Problems of Generating Productive Employment in the Youth Labor Market as a Dominant Risk Reduction Factor for the NEET Youth Segment in Kazakhstan. Economies 2023, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Shleifer, A. Informality and Development. J. Econ. Perspect. 2014, 28, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, 2016) McAfee, A. (2016). More from the second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy.

- Nafchi & Mohelska, 2019) Nafchi, M.Z., & Mohelska, H. (2019). The impact of Industry 4.0 on labor market: Theoretical and empirical evidence. Acta Informatica Pragensia, 8(3), 152–165.

- National Bank of Kazakhstan, 2025) National Bank of Kazakhstan. (2025). Macroeconomic review: Exchange rates, inflation and wages. Available online: https://nationalbank.kz (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Nazarbayev University, 2021) Nazarbayev University. (2021). Labour market inequality and informality in Kazakhstan: Empirical review. Center for Policy Research.

- OECD OECD Skills Strategy Kazakhstan; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2021.

- OECD, 2021) OECD. (2021). The future of work: OECD employment outlook 2021. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- OECD, 2025) OECD (2025). OECD Public Governance Scan of Kazakhstan; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pajarinen & Rouvinen, 2014) Pajarinen, M., & Rouvinen, P. (2014). Computerization threatens one third of Finnish em-ployment. ETLA Brief, 22, 1–6.

- Prettner, 2019) Prettner, K. ( 163, 273–292.

- Prettner, K.; Strulik, H. Innovation, automation, and inequality: Policy challenges in the race against the machine. J. Monetary Econ. 2020, 116, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri & Kergroch, 2023) Siri, S., & Kergroch, S. (2023). Modeling adaptive labor policies under automation scenarios. Future of Work Studies, 4(2), 111–128.

- Social Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2023) Social Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2023), No. 224-VII, adopted on , 2023. Available online: https://adilet.zan. 20 April 2300.

- Suleimenova, 2020) Suleimenova, S. ( 11(2), 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Sumer & Daut, 2022) Sumer, B., & Daut, V. (2022). Digital transformation and labor markets: Regional perspectives. Techno-logical and Economic Development of Economy, 28(4), 987–1005.

- Tigland, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , 2022) Tigland, R. ( 9(1), 1–19.

- Tulegenova & Tuleuova, 2022) Tulegenova, G., & Tuleuova, A. (2022). The impact of ICT infrastructure on regional labor market development in Kazakhstan. Economy: Strategy and Practice, 17(3), 89–101.

- UNDP Kazakhstan, 2021) UNDP Kazakhstan. (2021). Youth employment and NEET analysis in Kazakhstan. United Nations Development Programme.

- UNDP, 2024) United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Transforming Careers: How UNDP Increases Employment Opportunities for the Population; UNDP Kazakhstan, 2024. Available online: https://www.undp.org/kazakhstan/news/transforming-careers-how-undp-increases-employment-opportunities-population (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Uvaliyeva, 2023) Uvaliyeva, D. (2023). Assessment of the efficiency of state employment programs in Kazakhstan: Regional perspective. Public Administration and Policy Review, 4(1), 34–49.

- Van der Zande, 2020) Van der Zande, J. (2020). AI displacement and workforce resilience: A regional analysis. European Labour Studies Journal, 5(2), 45–60.

- Vossner & Schneider, 2017) Vossner, N., & Schneider, H. (2017). Digital disruption and labor adjustment: An empirical study across European regions. Labour Economics, 49, 1–15.

- World Bank, 2020) World Bank. (2020). Pathways to better jobs in IDA countries: Findings from jobs diagnostics. World Bank.

- World Bank, 2023) World Bank. (2023). More, better and inclusive jobs in Kazakhstan. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099030724012521561/pdf/P17983812e207b06a188db1b5af589b895f.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- World Bank, 2023) World Bank. (2023). Kazakhstan Jobs Diagnostic. W: Washington, DC.

- World Bank, 2024) World Bank (2024). World Social Protection Report 2024–2026: Universal Coverage for More Resilient Societies; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/3a191516-270b-40c9-acdf-79e3f382c708/content.

- Zholdasbekova, 2020) Zholdasbekova, A. (2020). Regional digital inequality in Kazakhstan: Causes and labor market impli-cations. Central Asia Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 5(2), 55–67.

| Aspect | Description |

| Resource Dependence | The concentration of employment in the oil, gas, and mining sectors creates sectoral and regional asymmetries in income distribution and job availability. |

| Role of the Public Sector | The predominance of employment in the public sector ensures social stability but limits competition, reduces labor market flexibility, and increases fiscal pressure. |

| Scale of Informal Employment | A high share of informal employment is observed in construction, trade, and agriculture, which reduces legal protection and the level of social security for workers. |

| Regional Disparities | Southern regions of Kazakhstan are characterized by an oversupply of labor, while northern regions face shortages of qualified personnel, deepening territorial imbalances. |

| Digital Transformation | The adoption of digital technologies and automation stimulates demand for IT professionals but leads to labor displacement in traditional sectors. |

| Demographic Features | Youth represent a significant share of the labor force but face limitations in experience and qualifications. |

| Migration Processes | Internal migration increases pressure on labor markets in major cities, while external migration and brain drain weaken the economy’s skilled labor potential. |

| Category | Labor Demand Factors | Labor Supply Factors |

| Sectoral Economic Structure | Rising demand in oil and gas industry, construction, IT sector, agriculture, and finance | Labor resources concentrated in traditional sectors; growing number of IT and service graduates |

| Regional Characteristics | Increased demand in urban centers (Almaty, Astana, Shymkent) | High unemployment in rural areas; migration to cities |

| Digitalization and Automation | Growing demand for specialists in programming, Big Data, and digital marketing | Shortage of workers with digital skills; need for retraining |

| Labor Migration | Influx of migrants into construction, agriculture, and service sectors | Outflow of qualified professionals abroad; internal migration from rural regions to major cities |

| Government Policy | Subsidies and entrepreneurship programs creating new jobs | Skill training for the unemployed; state internships and grant support |

| Demographic Trends | Aging population increases demand for healthcare, caregiving, automation, and management | High youth unemployment, limited employment opportunities for graduates |

| Informal Sector | Active demand for informal labor in construction, trade, and services | Large share of self-employed and informally employed; absence of formal labor contracts |

| Aspect | Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic | Impact of Digitalization |

| Unemployment Rate | Sharp increase in unemployment, especially in 2020 | Gradual decline due to creation of new digital jobs |

| Employment Formats | Decline in employment in traditional sectors; expansion of remote work | Steady growth of flexible models: freelance, remote, and hybrid arrangements |

| Labor Productivity | Decrease in efficiency under restrictions and instability | Productivity growth driven by process automation and digital platforms |

| Sectoral Redistribution | Severe decline in tourism, food services, and passenger transport | Increased employment in IT, e-commerce, fintech, and related sectors |

| Technology Adoption | Emergency deployment of online tools and platforms | Strategic development of AI, Big Data, cloud solutions, and digital HR management tools |

| Business Process Transformation | Temporary adaptation to remote work | Deep reorganization of processes with emphasis on digital skills and technological resilience |

| Cluster | Regions | Characteristics |

| 1 | Zhetysu Region, Karaganda Region, Kostanay Region | Sustained high growth >105% |

| 2 | Abai Region, Akmola Region, Almaty City, Pavlodar Region | Moderate growth ~101–104% |

| 3 | Aktobe Region, Mangystau Region, Astana City | Low growth, instability <100% |

| Sector | Share of Employment, % | Change, p.p. | |

| 2014 | 2023 | ||

| Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries | 18.9 | 11.9 | −7.0 |

| Industry | 12.8 | 12.3 | −0.5 |

| Construction | 8.0 | 7.1 | −0.9 |

| Trade and Repair | 14.7 | 16.7 | +2.0 |

| Transport and Storage | 6.9 | 7.1 | +0.2 |

| Education | 11.5 | 13.0 | +1.5 |

| Healthcare and Social Services | 5.5 | 6.4 | +0.9 |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Activities | 1.9 | 2.9 | +1.0 |

| Information and Communication (ICT) | 1.9 | 2.1 | +0.2 |

| Cluster | NEET Range (%) | Regions |

| Cluster 1 (Low NEET) | 4.8–6.1 | Astana, Shymkent, West Kazakhstan, East Kazakhstan, Kostanay, Pavlodar |

| Cluster 2 (Medium NEET) | 6.7–7.0 | Almaty, Akmola, Almaty Region, Zhambyl |

| Cluster 3 (High NEET) | 9.9–11.7 | Karaganda, Turkistan, Ulytau, Mangystau |

| Region | Total Employed Population | Remote Workers | Share of Remote Workers (%) |

| Kazakhstan (Total) | 9,081,920 | 42,514 | 0.47 |

| Almaty City | 1,045,505 | 3231 | 0.04 |

| Astana City | 658,663 | 2434 | 0.03 |

| Karagandy Region | 535,799 | 4590 | 0.05 |

| Atyrau Region | 335,132 | 33 | 0.00 |

| East Kazakhstan Region | 368,832 | 321 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).