1. Introduction

1.1. Overview and Background

Research has emphasized the increasing measures of sustainability that have significant impacts on the management of higher education institutions (HEIs). This consideration allows for more definite positioning of the actors enabling the promotion of environmental management and relevant implications regarding green behaviors (Zhang et al., 2021). In the UAE, educational institutions such as universities and colleges apply green functions and sustainability for the management of curricular themes and to enhance overall operational and cultural preferences.

There are a range of initiatives, such as the integration of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which can help to achieve goals such as successful management in academic programs, launching renewable energy projects within campuses, and enhancing student-led environmental policies through research commitments (Wood et al., 2021). Such ideas have been developed for the Middlesex University Dubai, to identify sustainability practices and management within the academic and community contexts, leading to recognized achievements such as the UAE Year of Sustainability Seal.

These efforts are helpful for increasing the awareness of HEIs while preparing future leaders to manage emerging complex challenges based on environmental changes through definite knowledge and relevant actions. Ethical leadership is considered effective for enhancing pro-environmental behaviors in organizations such as academic institutions (Ren et al., 2021). Leaders are responsible for demonstrating integrity, fairness measures, and a concern for sustainability, thus influencing the pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors of employees.

Clarification of roles, sharing of power, and provision of ethical guidance are helpful for leaders to create a workplace culture which offers value and support regarding possible green initiatives (Ullah et al., 2021). The implication of such a leadership style is that employees can effectively engage in a voluntary system of environmentally friendly actions that are considered effective for fulfilling their job requirements (Khan & Khan, 2022), thus enhancing the organization’s sustainability. Therefore, in the context of HEIs, ethical leadership is helpful for the faculty and staff regarding integrating sustainability within teaching practices, research implications, and campus management systems, ultimately reinforcing institutional commitments to environmental development and responsibility measures.

1.2. Research Gap

Although sustainability in higher education systems has been recognized at the global level, there are some definite research gaps when considering the Middle East—particularly the UAE—in this context. Ethical leadership has been shown to influence employee green behaviors (Islam et al., 2021). While the implications of sustainability initiatives in universities in the UAE seem to be well-documented, effective empirical studies examining the leadership dynamics which drive green employee behaviors remain scarce. Research has focused on the engagement of students with institutional policies, while devoting limited attention to the behavioral mechanisms within academic staff and administrators (Fatoki, 2023). These gaps limit the understanding of leadership practices and hinder the effective promotion of sustainable culture, considering the unique socio-cultural and organizational contexts of the academic sector in the UAE.

1.3. Research Objectives

The potential objectives of this research are as follows:

To investigate the relevant impacts of ethical leadership on the management of employee green behaviors in academic institutions in the UAE.

To Thematically identify different themes associated with ethical leadership, including people orientation, fairness, integrity, and concern for sustainability.

To assess the impacts of green behaviors on the higher education employees.

1.4. The Scope of the Research

This research involved both quantitative measurements obtained through surveys and qualitative insights via interviews, focusing on diverse HEIs across the UAE. This research seeks to contribute to the relevant theory by contextualizing ethical leadership in Middle Eastern academic environments and to practice by offering actionable recommendations for university leaders to enhance sustainable outcomes.

1.5. Structure of the Paper

The remainder of this research paper is structured into four significant sections.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on ethical leadership and employee green behaviors, highlighting the effective use of theoretical frameworks and definite empirical findings.

Section 3 offers details on the research methodology, including the design, sampling methods, instrumentation, data collection process, and analysis procedure.

Section 4 presents the results derived from both quantitative and qualitative data and integrates the findings to effectively address the research objectives. Finally,

Section 5 defines the implications of the research work, outlines the study’s limitations, and offering suggestions for future research, aiming to maintain the integrity of academic leadership in the UAE. Followed by the conclusion and ending notes in section 6.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ethical Leadership (EL)

Ethical leadership refers to leading by doing the right and fair things, and includes being honest, fair, caring, and respectful to employees (Knights, 2022). Ethical leaders treat everyone equally, help to create a safe space, and guide their team members to behave responsibly. Brown et al. (2005) defined ethical leaders as those that are honest and principled. They believe that ethical leaders set a good example through the right actions. Kalshoven et al. (2011) classified many traits of ethical leadership, including people orientation, fairness, honesty, and role clarification. Ethical leaders also share power and allow others to provide input.

They offer clear roles and guide their teams with moral support. Another important trait is concern for sustainability and the planet (Neamțu & Bejinaru, 2019); in particular, ethical leaders promote green values and eco-friendly workplace behaviors. They support their teams in adopting habits that protect natural resources. This kind of leadership supports long-term goals and responsible actions (Kumar et al., 2023) and allows organizations to meet both ethical and environmental expectations. Ethical leadership also builds trust among workers and senior managers (Malik et al., 2023).

Employees feel appreciated when leaders show fairness and strong values. This builds loyalty, motivation, and commitment to the organization’s success. Leaders who care about people and nature inspire others to follow. They cultivate a workplace culture based on fairness and responsibility (Sharma et al., 2019). At present, ethical leadership is considered highly important due to serious worldwide challenges and concerns such as climate change and resource use. Leaders who act ethically help to drive progress towards achieving sustainability goals, and push for policies that protect the environment and future generations (Guerra et al., 2022).

These leaders support honesty, openness, and doing what is morally right, which helps employees to feel safe, valued, and trusted in the workplace (Yadav et al., 2024). A solid ethical culture inspires people to behave with similar values. This kind of leadership shapes trust and strengthens team relationships over time (Malik et al., 2023). Moreover, ethical leadership is more important at present than ever before, with the world facing many serious environmental and social problems.

2.2. Employee Green Behavior (EGB)

Employee green behaviors refer to actions in the workplace that serve to protect the environment. These actions can be small or big but are always important. EGBs help to decrease the harm caused to the planet through everyday work practices (Unsworth et al., 2021). These behaviors cover both those that are job-related and extra efforts outside one’s normal job duties. Task-related green behavior (TRGB) is part of an employee’s daily tasks. Examples include turning off unused lights, printing fewer paper documents, using office supplies wisely, and avoiding energy waste (Aroonsrimorakot et al., 2019). These small steps help to decrease a workplace’s environmental impacts.

Extra-role green behaviors are actions beyond formal job descriptions and tasks. They include civic engagement, eco-initiatives (eco-civic initiatives behavior; ECIB), and helping others to act green. ECIB refers to joining eco-projects or awareness campaigns (Levinthal & Weller, 2023); for example, employees may join tree planting or clean-up drives in their local areas. Such actions show care for both the environment and the larger community. Eco-conscious initiative behaviors (ECEBs) include suggesting new green workplace ideas; for instance, finding ways to save paper or reduce electricity use (Ramirez & George, 2019).

Employees might suggest reusable items or better recycling systems at work. These ideas come from workers who care about sustainability and change. Eco-helping behaviors (ECHBs) refer to helping one’s coworkers to follow eco-friendly habits daily, such as reminding others to recycle or switch off unused machines. It also means teaching green habits to coworkers in a kind way (Lee and Manfredi, 2021). Many factors affect the green behaviors of employees in the workplace. Leadership plays an important role by setting examples and inspiring actions. Organizational culture, awareness, and personal values also guide green behaviors (Ahmad et al., 2021).

A supportive workplace helps employees to feel confident about acting environmentally responsible. These efforts jointly cultivate a strong green culture in the workplace. Moreover, many factors affect the green behaviors of employees in the workplace environment. The main factor is leadership and how leaders set daily examples. Ethical leaders often talk about saving energy, water, and natural resources (Streimikiene et al., 2021). They also support green projects and reward employees for eco-friendly actions. When leaders behave responsibly, employees are more likely to follow them. Significant factors in this regard include organizational culture and shared workplace values (Roscoe et al., 2019).

Green posters, eco-policies, and training also send clear, positive messages. A culture that supports the environment inspires people to do more. Awareness and knowledge also support employees in making better green choices (Ahmad et al., 2021).

2.3. Relationships Between EL and EGB

Many studies show how ethical leaders affect green actions in workers. Ethical leaders set examples for others to follow at work (Nguyen & Dekhili, 2024). They talk about values such as honesty, fairness, and responsibility. These values are linked with caring for nature and saving resources. Employees learn by watching leaders act ethically and sustainably such that leaders who care for the planet inspire workers to adopt green actions (Younas et al., 2023). Ethical leaders talk openly about values, such as fairness and responsibility, which often connect with environmental care and saving natural resources.

Leaders who protect the planet send strong messages to their employees. They motivate their teams to follow green habits in their daily routines. Employees learn not just from training, but also from real actions. When leaders recycle, save energy, and support green efforts, workers notice (Alwali & Alwali, 2025). This mode of learning by example is called social learning or observational learning, which helps to pass down values and behaviors in a practical way. In this context, Brown et al. (2005) found that ethical leaders influence moral behaviors and Kalshoven et al. (2011) linked ethical traits with employee actions.

Recent studies have explored the impacts of ethical leadership on environmental behaviors. For example, Mi et al. (2020) showed how leadership can improve green habits, finding that ethical leaders increase civic engagement and task-related green behaviors. Paillé et al. (2016) supported this idea with similar results. Many studies have shown that ethical leadership affects employee green behaviors at work, demonstrating that leadership shapes employee behaviors in both big and small ways. The studies conducted by Brown et al. (2005) and Kalshoven et al. (2011) supported the idea that the leaders with fairness, care, and guidance inspire green behaviors.

Mi et al. (2020) also found that ethical leadership supports civic action, and Paillé et al. (2016) linked leadership with task-related green behaviors. These studies demonstrate the soli connection between leadership and green behaviors. Moreover, a few studies have focused on higher education institutions and their employees. Universities are large and complex workplaces with unique sustainability roles.

2.4. Theoretical Foundation

This study uses three main theories to explain the relationship between EL and EGB. These theories support the idea that leaders influence green behaviors in the workplace (Saleem et al., 2020).

Figure 1 shows the conceptual diagram as a result pf the theoretical foundation.

2.5. Social Learning Theory

The first theory is Social Learning Theory, proposed by Bandura (1977). This theory states that people learn by observing others and copying their behaviors. If a leader acts ethically, employees will likely do the same. Leaders become role models when they show honest and genuine actions. Employees often copy the behaviors of leaders that they admire and respect (Hameed et al., 2022). In this way, values are passed from leaders to their teams.

2.6. Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) Theory of Behavior

The second theory is Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) Theory of behavior. This theory links values and beliefs with personal environmental responsibilities. When people value nature, they feel a strong duty to protect it (Ahmad et al., 2021). This duty leads to eco-friendly actions in their daily work settings. Leaders shape these beliefs by sharing green values and workplace norms (Plimmer et al., 2022). Ethical leaders support the creation of a shared belief in environmental care. Employees influenced by these values feel more responsible to act green (Sadiq, 2023).

2.7. Environmental Stewardship Theory

The third theory recognized in leadership studies is Environmental Stewardship Theory. Stewardship means protecting the environment for future generations and communities. Ethical leaders see stewardship as an important part of their role and encourage employees to care for nature in their work. This leads to the creation of shared goals based on long-term sustainability and eco-awareness (Nguyen & Dekhili,2024). All three theories mentioned above work together within the framework of this research project, supporting the development of the interview questions and survey tools. They reflect how leadership influences behaviors through learning, values, and duties.

Together, these theories support better understanding regarding how EL shapes employee green behaviors (Younas et al., 2023). These theories help to shape the shared sustainability and eco-awareness goals, emphasizing the ways in which leaders influence employee behaviors in positive, green ways. Each theory clarifies a different part of how learning and values work (Rasheed, 2025); for example, Social Learning Theory demonstrates how employees copy the ethical green actions of leaders. Employees follow leaders who show respect, honesty, and environmental responsibility. Furthermore, Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) Theory clarifies the roles of personal values (Alwali & Alwali, 2025).

When leaders support green values, employees start to feel a moral duty, which leads them to act in eco-friendly ways. VBN Theory connects beliefs and actions through a sense of responsibility. Finally, Environmental Stewardship Theory adds the idea of long-term care for nature. Payne et al. (2023) stated that leaders who practice stewardship think about future generations and the planet. They guide employees to protect the environment through actions in the workplace, thus shaping a solid green culture that benefits both people and nature.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study used a mixed-methods sequential explanatory design, which involved gathering quantitative data first, followed by qualitative data. This method supports elaboration of the survey results through follow-up interviews (Toyon, 2021). First, data were collected using a structured questionnaire. The interviews provided thoughtful insights into the views held by employees. This design supports understanding of both quantitative aspects and real-life experiences (Wipulanusat et al., 2020), balancing the strengths of both methods used in the study. The overall aim was to discover how ethical leadership shapes green behaviors, and the study design allowed us to assess both general trends and detailed opinions.

3.2. Sample and Setting

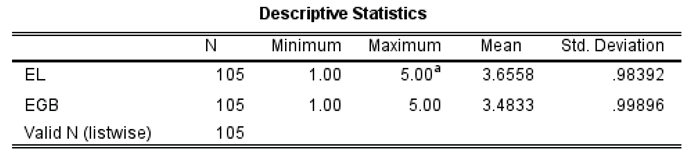

The setting of the study was academic institutions in the UAE. The target sample included higher education institution (HEI) employees (Boeske, 2023), covering faculty members, administrative staff, and technical support teams. These people work in environments that affect sustainability practices (Leal Filho et al., 2020), and their experiences with leaders influence how they act towards the environment. A sample size of 105 employees was selected, which was considered sufficient for statistical analysis and deriving meaningful results. The setting comprised universities and colleges in urban areas (Usman et al., 2023). A mixed-method approach was used, including surveys followed by qualitative follow-up interviews, with thematic analysis applied to understand the qualitative data. Subsequently, interviews were conducted with six participants to gain a deeper understanding of their responses.

At present, the considered institutions are working to become more eco-friendly, and employees in these places are faced with various policies, leadership styles, and green campaigns (Swathi & Johnpaul, 2025). The academic environment is ideal for studying leadership and sustainability, and it has been shown that ethical leadership in such places may affect green workplace behaviors (Ogbeibu et al., 2024). Moreover, diversity in roles and job experience is emphasized in this context; as such, individuals with diverse genders, age groups, and job types were involved in the study.

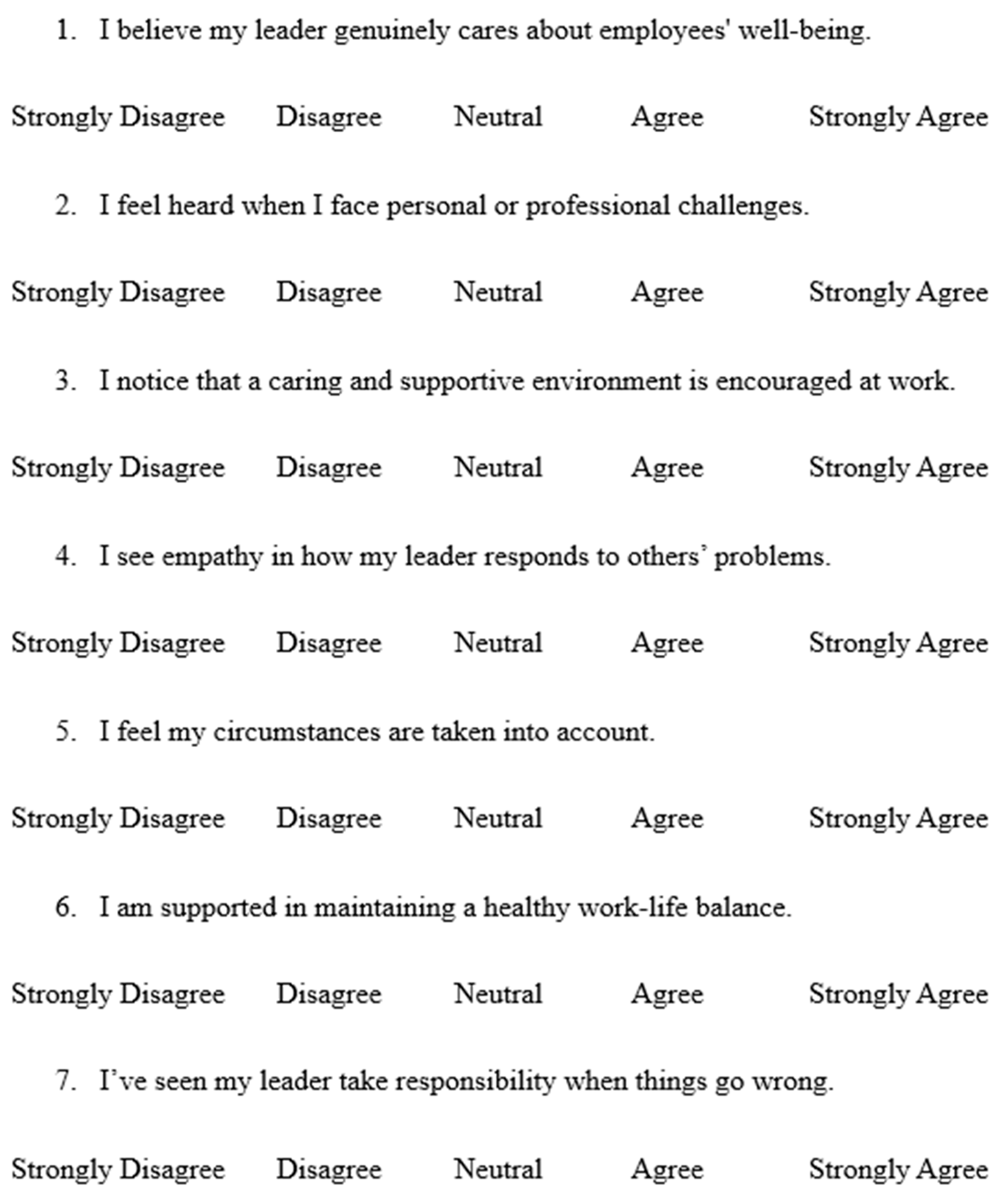

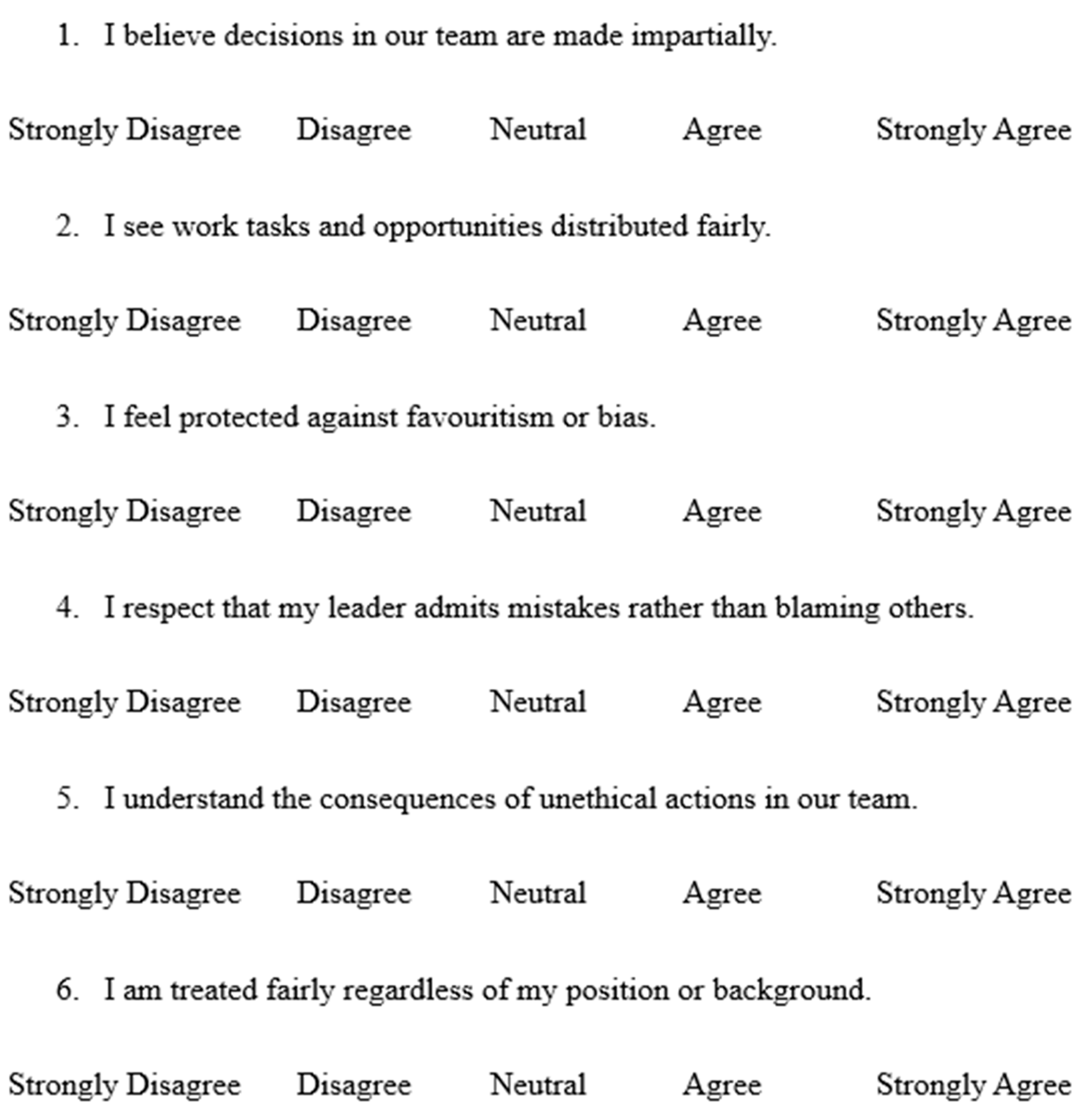

3.3. Instrumentation

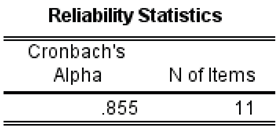

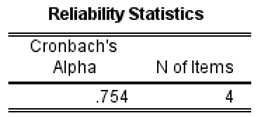

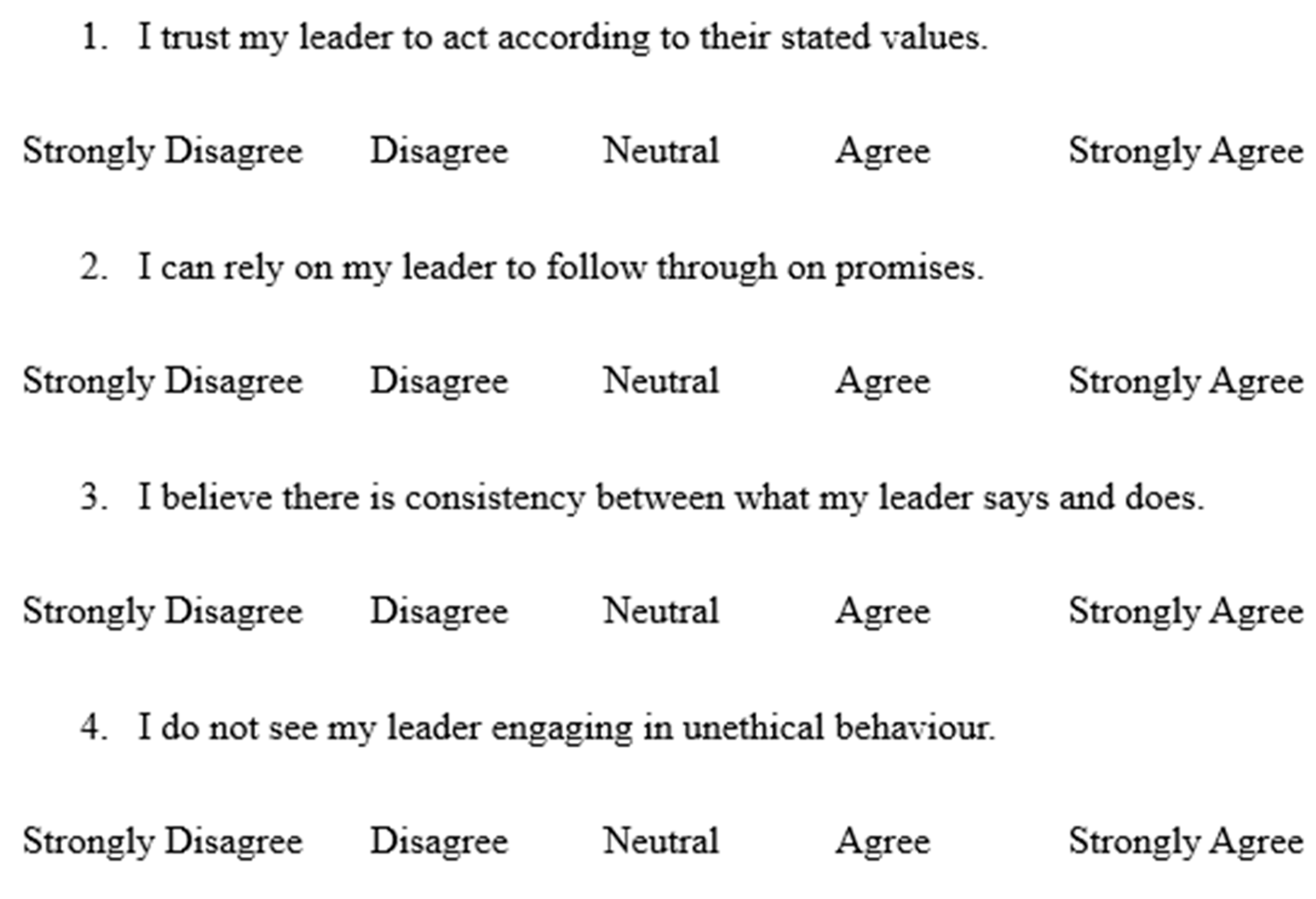

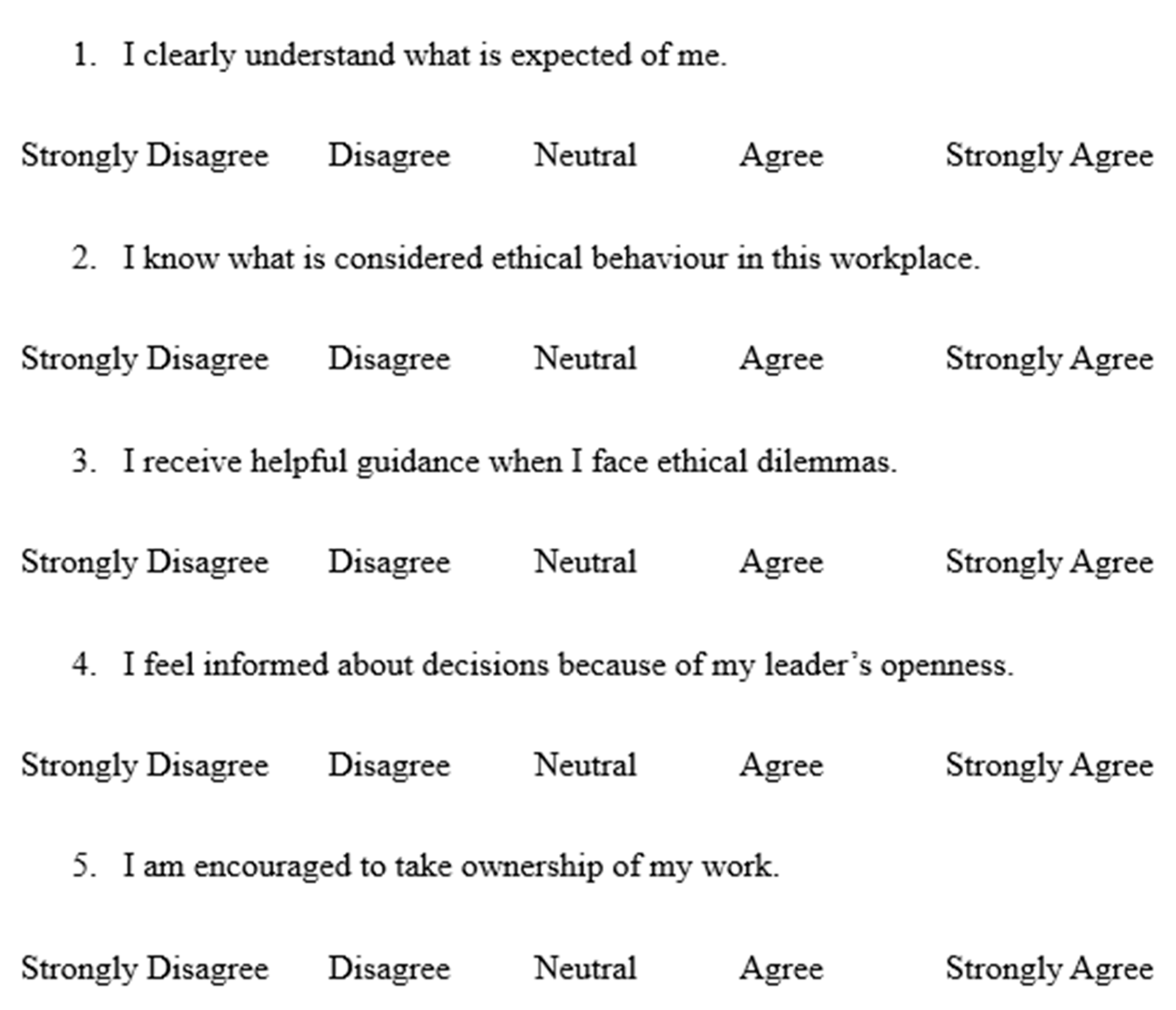

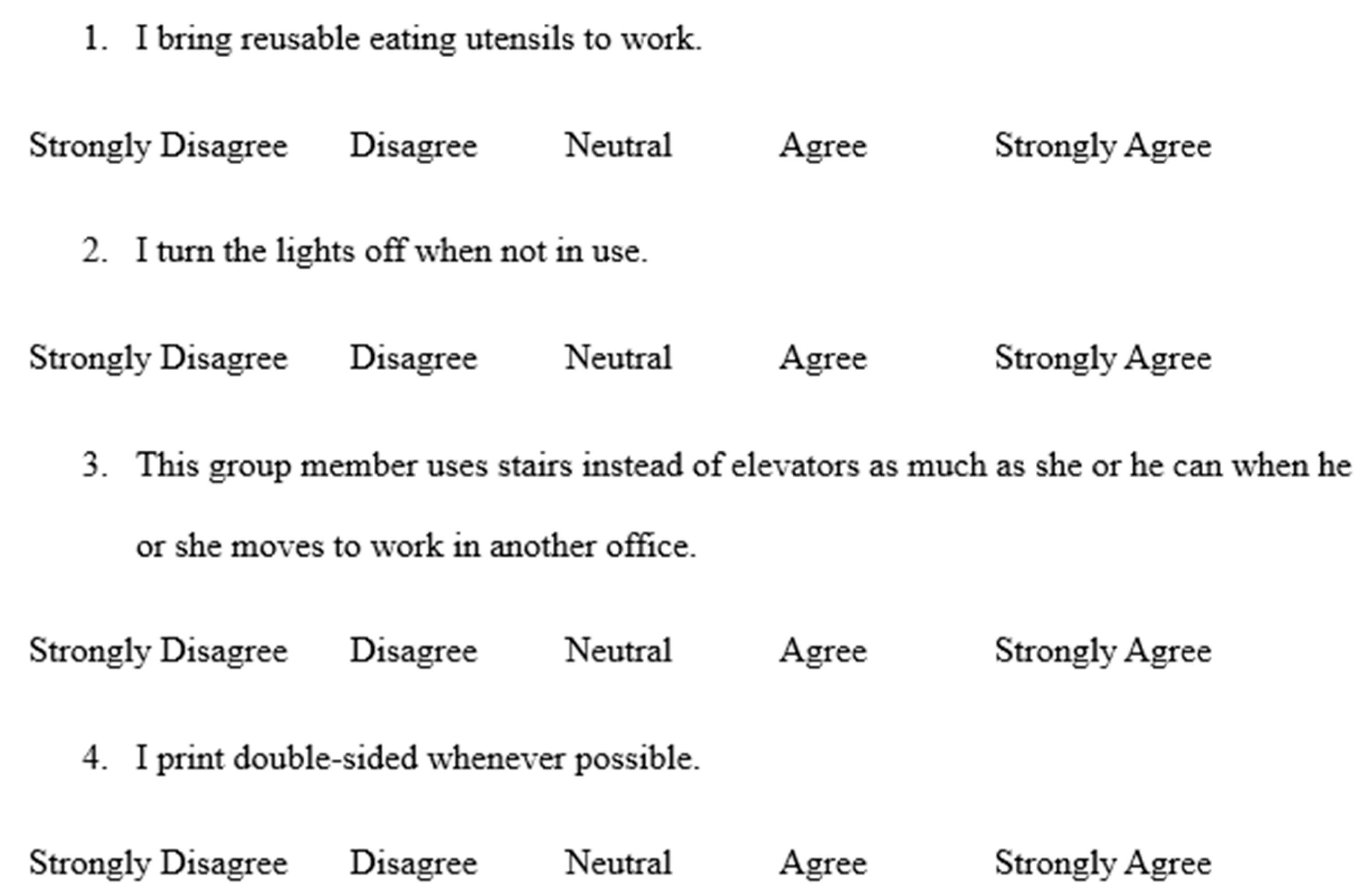

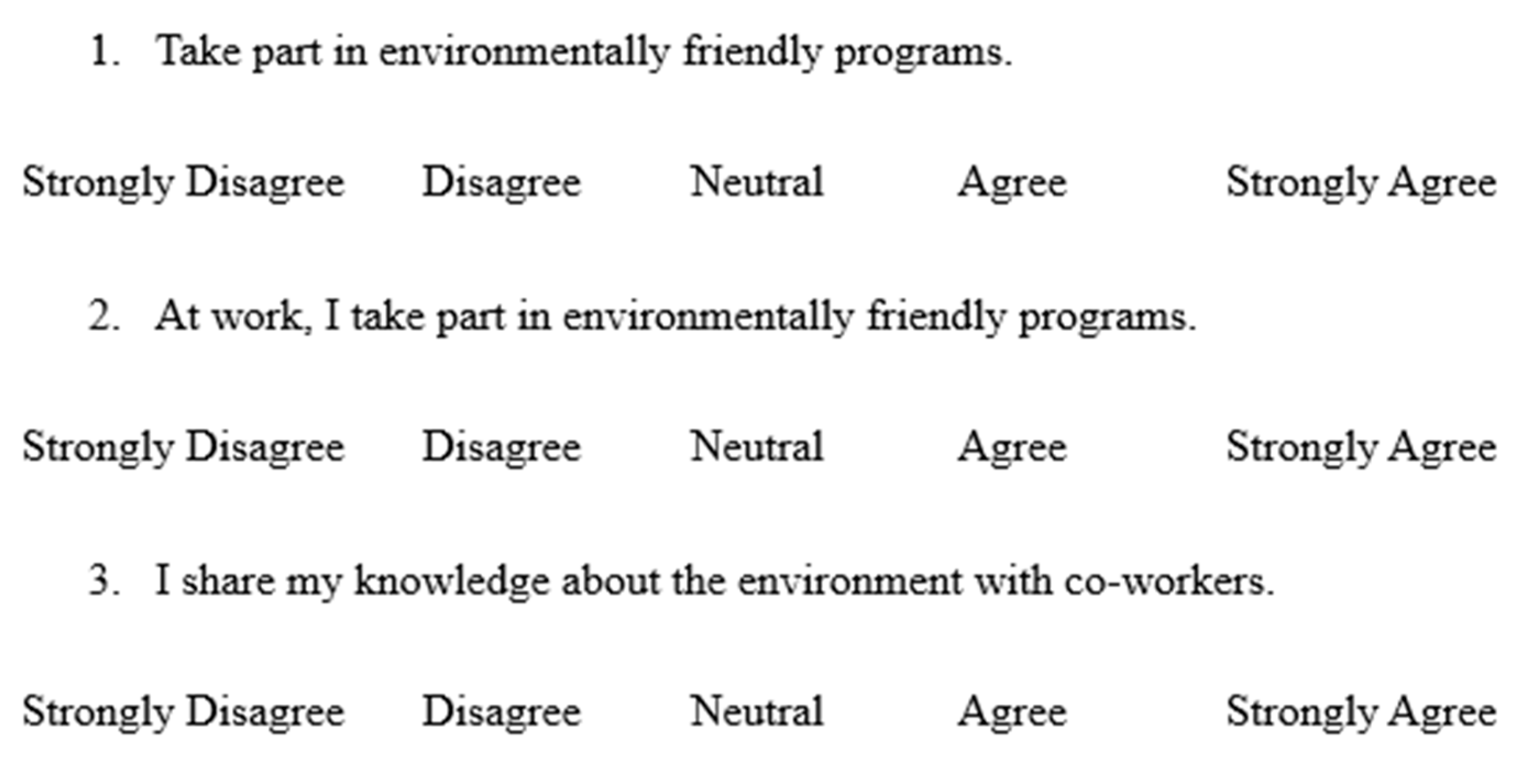

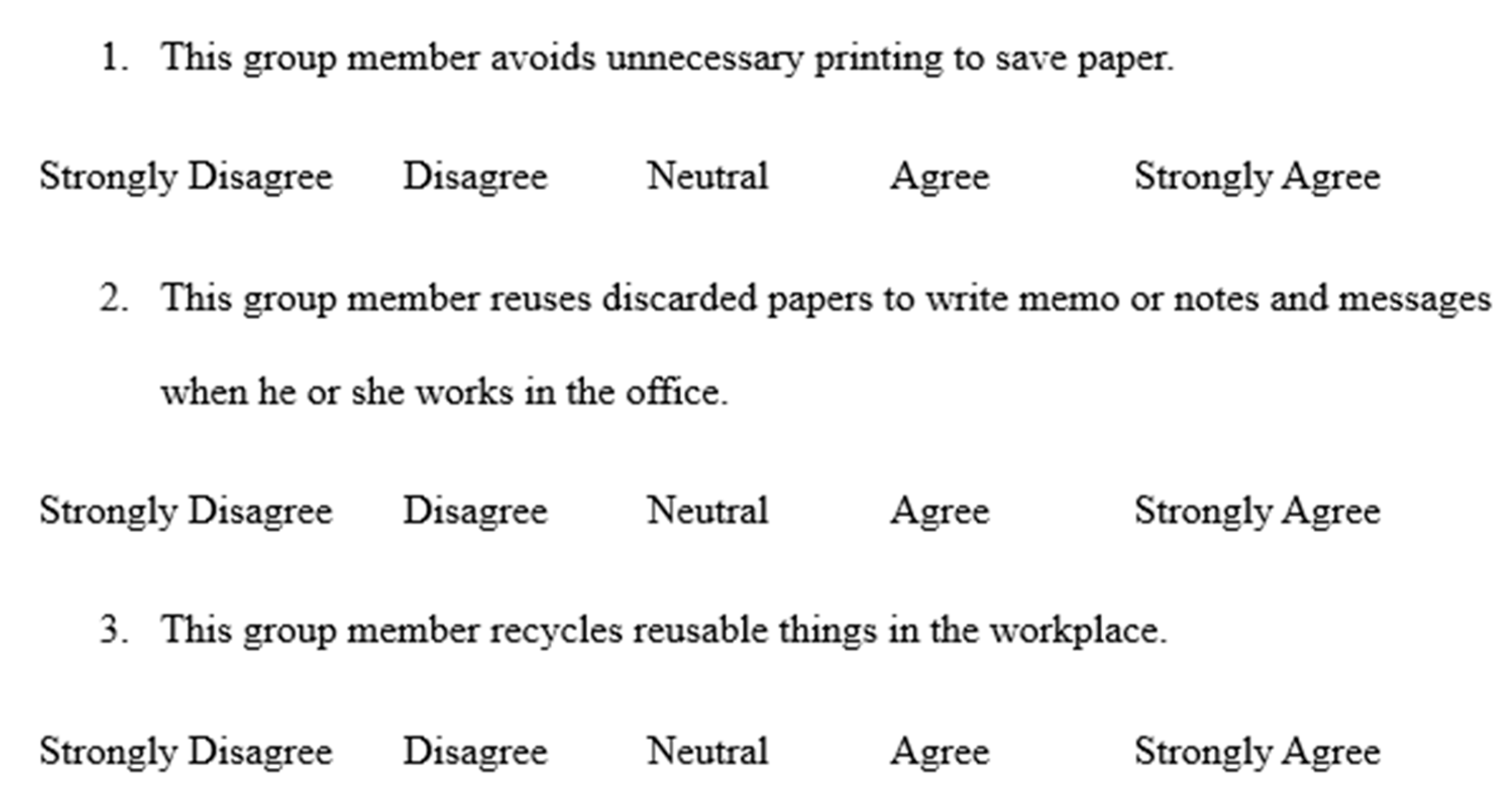

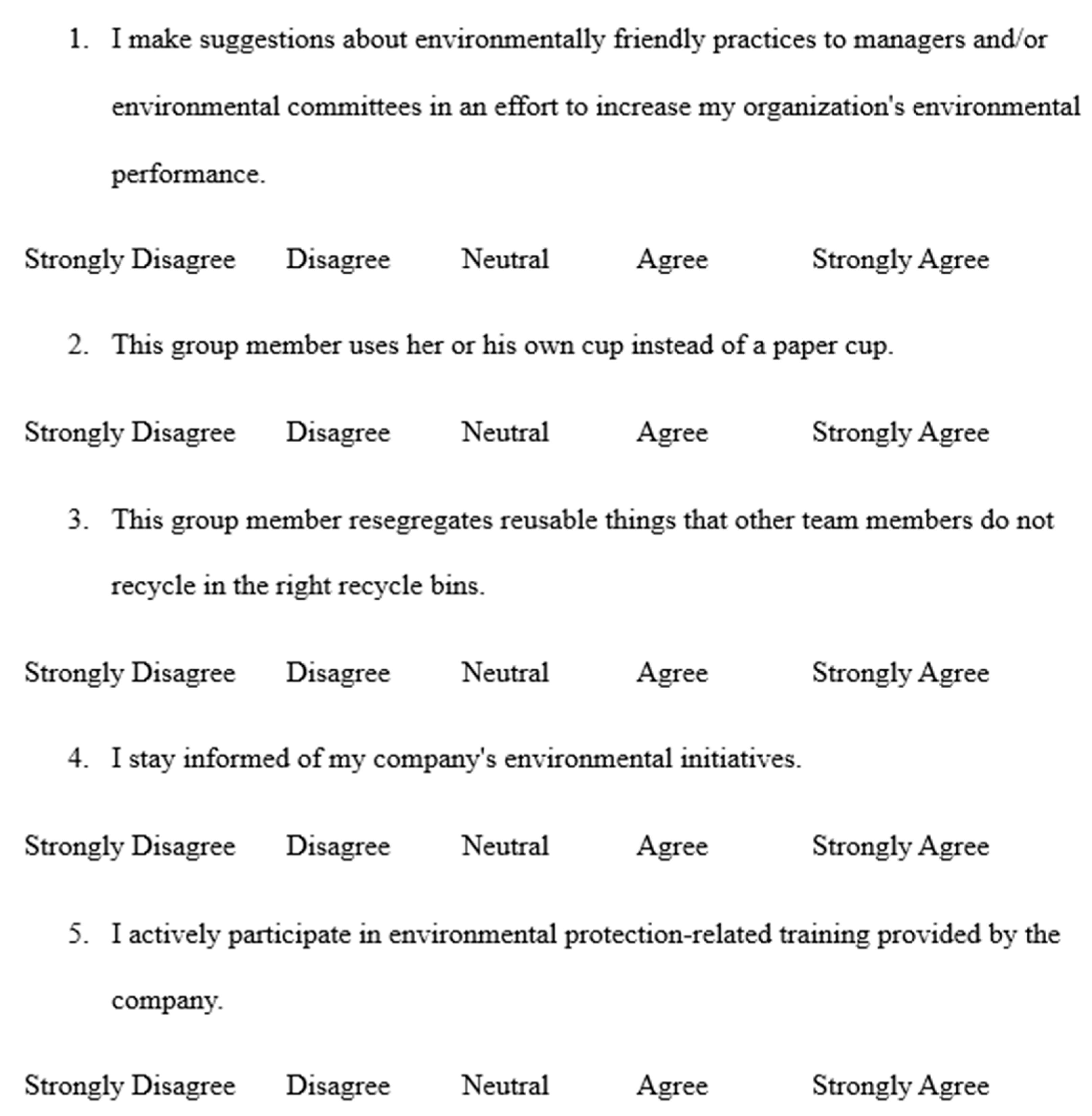

To ensure respondent engagement and reduce survey fatigue during the pilot phase, a reduced-item strategy was implemented for both the ethical leadership (EL) and employee green behavior (EGB) scales. From the original 38-item EL scale developed by Kalshoven et al. (2011), 7 items were carefully selected which is one from each of the seven sub-dimensions to maintain both breadth of content and theoretical representation. The selected items were (1) “Cares about his/her followers” (people orientation), reflecting the core interpersonal concern of ethical leaders; (2) “Holds me accountable for problems over which I have no control” (fairness), representing fairness in accountability; (3) “Allows subordinates to influence critical decisions” (power sharing), emphasizing participatory leadership; (4) “Shows concern for sustainability issues” (concern for sustainability), directly aligning with the study’s environmental focus; (5) “Clearly explains integrity-related codes of conduct” (ethical guidance), highlighting clarity in moral expectations; (6) “Explains what is expected of each group member” (role clarification), emphasizing role transparency; and (7) “Can be trusted to do the things he/she says” (integrity), denoting reliability and moral trust.

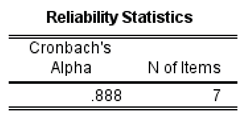

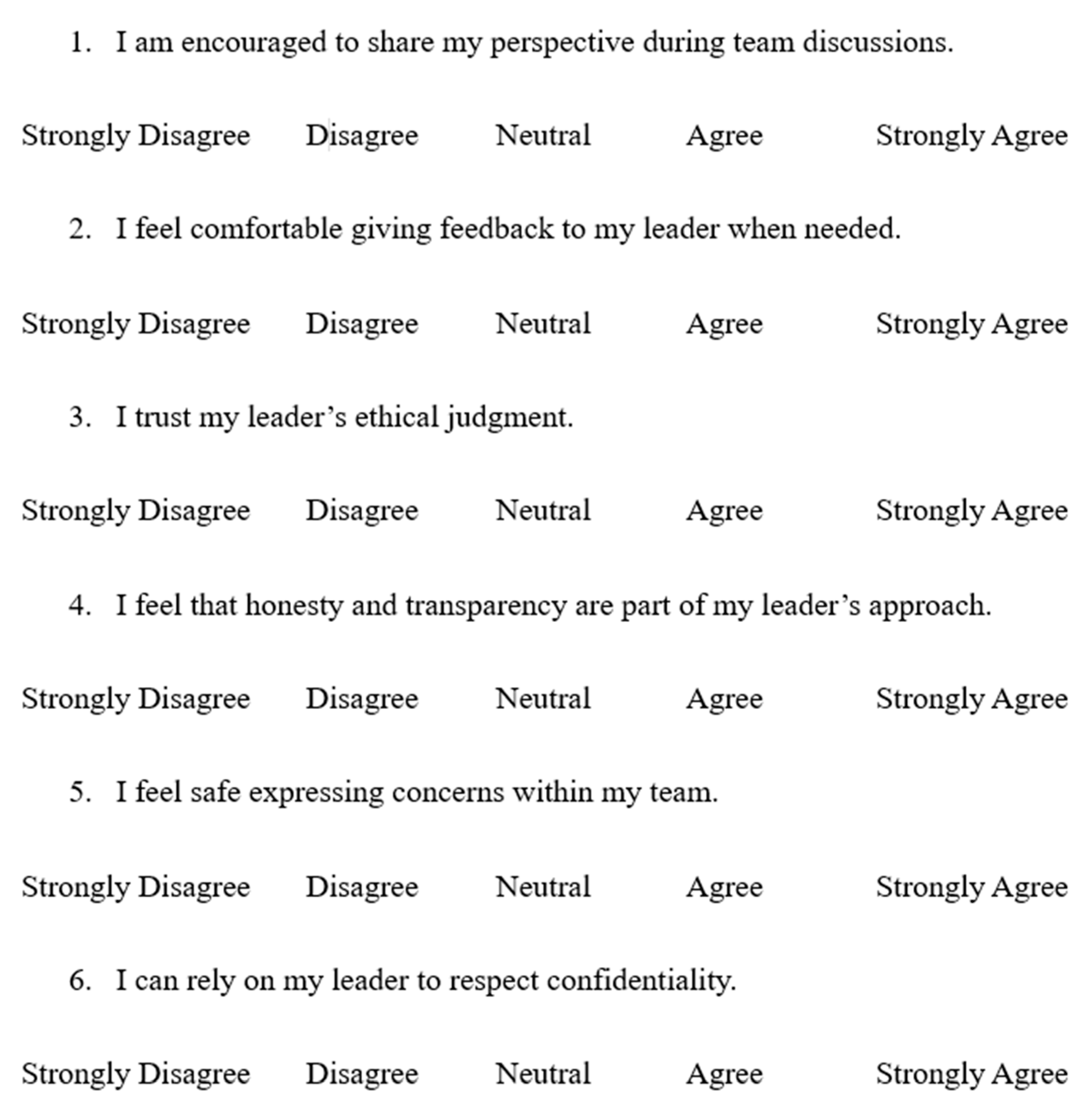

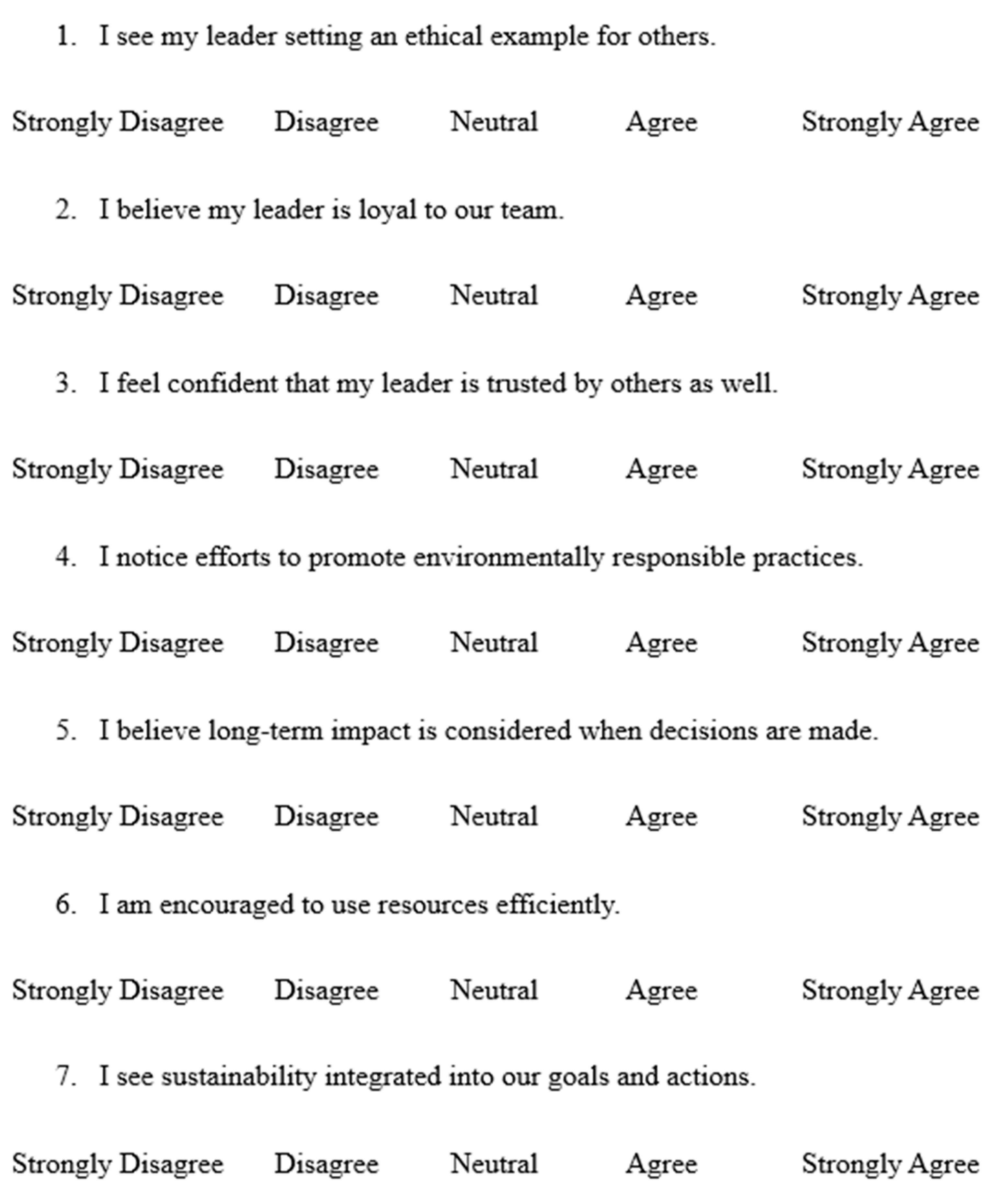

For the EGB scale, originally consisting of 15 items, 4 key items were retained to reflect different domains of green behavior. These were (1) “I can accomplish the environmental protection tasks within my duties competently” to capture job-aligned environmental responsibility; (2) “I pay attention to energy conservation and low-carbon travel in my daily work” to reflect individual daily sustainable practices; (3) “I voluntarily carry out environmental actions and initiatives in my daily work” to assess proactive engagement; and (4) “I spontaneously encourage my colleagues to adopt more environmentally conscious behavior at work” to measure peer influence and advocacy. These items were chosen due to their strong alignment with the constructs under study, ensuring conceptual coverage despite the reduced format. This approach balances the need for brevity in pilot testing with the preservation of theoretical and measurement integrity. The full scales will be reintroduced in research relating to the final thesis for comprehensive validation and comparison.

3.4. Data Collection

This study used two main tools for data collection: a survey and follow-up interviews. First, a structured questionnaire was shared with 105 employees from different higher education institutions (HEIs) in the UAE (Younas et al., 2023). The survey contained two main parts: the first measures ethical leadership using 7 items from 7 sub-dimensions which is one from each dimension; the other measures employee green behavior with only 4 items (Nguyen & Dekhili, 2024). The respondents were asked to answer the two parts on a 5-point Likert scale varying between 1 (Strongly Disagree) and 5 (Strongly Agree). The survey was issued on the internet via email or through institutional channels, depending on the ease of accessibility.

Once the survey results were obtained, a smaller group of respondents was then chosen to carry out semi-structured interviews. These interviews were conducted to further elaborate on the survey outcome (Wipulanusat et al., 2020) to better understand the outcomes of the employees regarding ethical leadership in the workplace and its impact on their green behaviors (Wipulanusat et al., 2020). The interviewees were also requested to give personal examples, such as how their leader encouraged pro-environmental behaviors or what encouraged them to act sustainably. The interviews were not tape recorded as it seems that voice recording is viewed as disrespectful and in poor taste, so the data was transcribed on spot.

The combination of surveys and interviews allowed for the collection of a greater volume of data, including profound individual insights (Younas et al., 2023). The survey provided an overall picture, whereas the interviews elaborated on real-life experiences associated with the obtained data. The synthesis of these two approaches provided more complete and balanced insights into the research topic. For the existing study, a mixed-methods approach was applied, allowing both quantitative and qualitative data to be collected. Quantitative data collection was based on issuing an online survey, which was distributed using institutional email resources (Younas et al., 2023). Two reminder waves were implemented, with the goal of achieving a good response rate. The surveys were issued based on purposeful sampling with random components which means if the employees work in HEI then they can fill the data.

The qualitative part of the study was based on the semi-structured interviews carried out with selected participants that were allocated relatively high or low EGB scores. The interviews were 10-15 minutes long and were conducted virtually using email and video formats. The interviews allowed for exploration of themes such as leadership influence mechanisms and the institutional barriers to sustainability (Mercader et al., 2021).

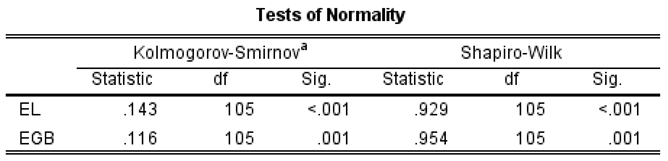

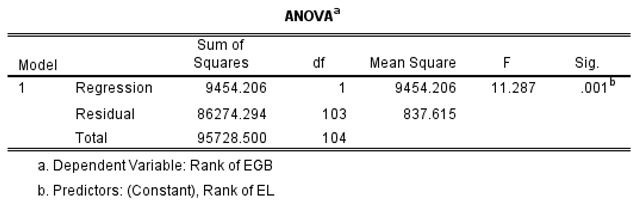

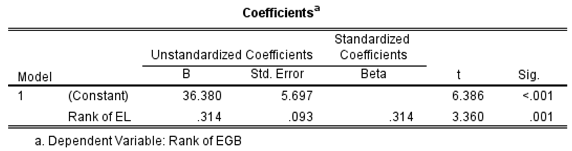

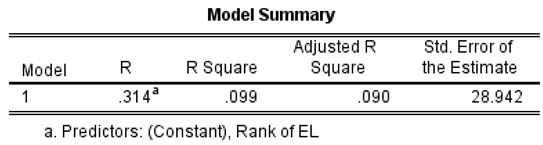

Data were collected to determine the results collected from the participants and related processes (Younas et al., 2023). Two types of methods were applied in this research for the collection of data. For the quantitative analysis, the researchers used SPSS to manage the results through descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies and standard deviations), a scale reliability system for assessment, and inferential analyses based on hierarchical regression for testing of the EL–EGB relationship with the use of a controlling system for the covariates. The implications of the mediation analysis are also helpful for determining the mediating influences of variables such as organizational trust in the relationship between EL and EGB (Hoang et al., 2023). Thus, SPSS was utilized to conduct all analyses of the data collected through the distributed questionnaire.

On the other hand, the qualitative data were assessed through thematic analysis of the transcripts, which were allocated using an open coding system involving, for example, identifying the initial concepts, grouping concepts within the themes, and selection of codes for integration of the themes to develop an explanatory framework (Younas et al., 2023). Triangulations were performed to merge the quantitative patterns and qualitative insights, such as comparison of the regression results with the interview outcomes, to better understand the impacts of leadership practices.

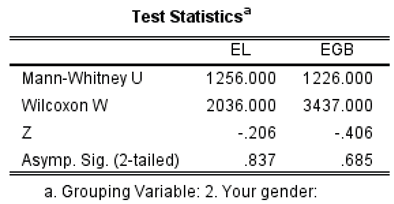

3.5. Data Analysis

This research involved both qualitative and quantitative analyses. The use of the SPSS software allows data collected in a quantitative format, such as those derived from surveys, to be analyzed (Habes et al., 2021). This software helps to describe the basic features of data through descriptive statistics, such as averages and percentages (Rahman & Muktadir, 2021). Next, correlation tests were performed to determine the links between ethical leadership (EL) employee green behaviors (EGBs). The results of these tests serve to support or reject the research hypotheses. In contrast, the qualitative data from the interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis, which involved reading the interviews carefully and finding common patterns (or themes) in the responses.

The researcher coded each response, thus grouping those with similar meaning (Habes et al., 2021). These themes may indicate how ethical leaders inspire green behaviors at work and may also help to determine the differences between authentic and performative green actions. For example, some employees may perform green actions to look good in front of others (Rahman & Muktadir, 2021), while others act green due to their strong personal values and ethics. Interview quotes support the explanation of these themes; for instance, one employee might say that their manager talks about saving water every week, while another might say they only recycle when the boss is around (Brummans et al., 2020). These quotes highlight gaps between true and surface-level green behaviors. Through comparison of the survey results and interview stories, a better understanding can be obtained, which can help to suggest ways to improve ethical leadership and green practices in HEIs.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Quantitative Results

The Ethical Leadership (EL) construct in this study consists of seven core traits: fairness, integrity, ethical guidance, people orientation, power sharing, role clarification, and concern for sustainability. Given the statistically significant positive correlation between ethical leadership and employee green behaviour, it becomes essential to recognize that each of these traits plays a meaningful role in shaping pro-environmental actions. This correlation underscores the importance of not viewing EL as a singular dimension but rather as a holistic model where all seven traits collectively contribute to fostering a culture of sustainability and ethical responsibility within academic institutions.

The survey results revealed a strong link between ethical leadership and employee green behaviors. Leaders who truly care about the environment inspire staff to present green behaviors. This finding agrees with that of Neamțu & Bejinaru (2019), who reported similar results. ethical guidance encourages employees to make green suggestions at work, as staff who are provided with clear moral guidance are more motivated to act sustainably. This supports the standpoint of Brown et al. (2005), who see ethical leaders as moral mentors. These leaders not only behave ethically themselves but also guide others to do so. Leaders who care about the well-being of staff build trust and safety at work. This trust helps employees to feel free to act in eco-friendly ways. Knights (2022) and Malik et al. (2023) similarly stressed the value of trust. Their works demonstrated that supportive leaders create space for the growth of green choices and behaviors. Staff who feel supported may recycle, save energy, or join green teams (Asif et al., 2022). When leaders clearly show that they care about the environment, they can make the greatest impact on employee behaviors. Their open support sends a strong message to staff to act green, who then see environmental care as a shared workplace value to follow. This finding supports earlier research linking leader values to staff actions.

EL is perceived to allow cultivation of workplace culture that promotes eco-friendly behaviors. Staff who feel respected and valued are more likely to present green behaviors. They see that their leaders support them both personally and professionally. As a result, it can be stated that without clear ethical goals, structure and shared power alone may not drive change. This suggests that structure should be implemented alongside strong ethical leadership to achieve successful outcomes. Leaders need to combine clarity and shared power with moral guidance (Arshad et al., 2021), and concern for sustainability must be a clear part of meetings, plans, and daily tasks. Ethical guidance must move beyond words and become visible in daily work, such that staff see their leaders acting on the values they share openly. People orientation must also stay central to leadership training and growth plans. Leaders must keep listening to staff concerns and support them in green choices. For managers in higher education, these findings provide a clear next step to take. Leadership training should involve teaching how to talk about ethics in real-life work scenarios. Managers should show staff why green actions fit the wider goals that they hold, and the staff need to clearly see that their leaders care both about them and the planet. These factors serve to create a workplace in which staff feel safe to carry out green actions daily. When leaders show real care for the environment, the staff likely do the same. In summary, clear ethical guidance, care for people, and visible green values matter the most. Together, these factors help to shape a culture in which staff feel free to act green (Alkadash et al., 2023) and, in turn, helping higher education institutions to meet their wider sustainability goals.

5.2. Qualitative Interpretation

The interviews helped us to better understand employee views on green behaviors. The staff felt inspired when leaders acted in ways that matched their words; for example, they noticed when managers truly cared about saving energy. Employees often shared that leaders who “walk the talk” had a greater impact. This relates to Social Learning Theory, in which it is considered that people copy the actions of leaders that they trust. Employees reacted positively when leaders showed daily green behaviors; for example, they valued seeing managers use less paper and support recycling plans. The staff said that these actions seemed genuine and not just for show. Genuine green actions were seen as regular and driven by real beliefs. Leaders who started projects themselves were trusted more by their teams, and employees also liked when teachers added sustainability topics to lessons naturally. In contrast, staff saw some green campaigns as being mainly for image. These top-down plans felt forced and lacked true internal team support. Employees could perceive when plans were designed with the aim of looking good from an outside perspective. This agrees with the studies of Mi et al. (2020) and Roscoe et al. (2019), who also found that staff notice whether projects feel symbolic or honest.

The staff said that real green actions were linked to values they truly shared, while performative green actions led to people simply following rules without heart, using words like “tick-box” to describe those forced projects. Some admitted to acting green only when their bosses were watching them; for example, they would switch off lights or print less when seen by their managers. This type of green compliance is linked to a lack of personal belief or inner drive (Ali et al., 2021) and shows that the influence of leadership depends on the organizational climate and level of trust. Employees cared if their leaders’ words and daily habits matched each other: when they saw honest effort, they felt motivated and proud to do the same. In contrast, if they felt that these actions were disingenuous, they did not feel motivated. Paillé et al. (2016) reported a similar pattern in workplaces. Ethical leadership had power only when people trusted leaders’ real intentions. The staff also spoke of wanting more voice in green decision-making. They felt included when asked to share ideas for saving energy, and suggested more workshops, shared goals, and open talks on progress. The employees liked when leaders listened and valued their green suggestions, which helped to them feel as though they are part of the bigger change, not just tools. The interviews revealed that authentic actions inspired true and lasting change, while performative actions only led to surface-level efforts and weak commitment. True green behaviors grow from trust, shared values, and daily actions.

The consideration of academic institutions regarding the importance of ethical leadership seems to have an influence on employees’ engagement in green behaviors. Such an environment allows for the fostering of a culture based on environmental responsibility that is grounded in trust and moral examples (Hameed et al., 2022). The leaders are considered effective in consistently demonstrating integrity, fairness, and concern based on sustainability concepts, contributing to the creation of a positive psychological climate. According to Al Halbusi et al. (2021), this is helpful in making employees feel motivated to align their daily actions with organizational environmental goals. The employees witness leaders who are responsible for providing authentic management practices aligned with a commitment to sustainability, including the integration of transparent communication based on green policies and visible participation in eco-friendly initiatives. Ahmed et al. (2022) have stated that such practices encourage the development of policies promoting the adaptation of similar behaviors, influencing the reinforcement of social learning processes. Therefore, Zhang et al. (2021) elaborated that the alignment between leadership values and employee actions is helpful in the management of practical green behaviors such as energy saving, waste reduction processes, and participation in environmental programs.

The role of ethical leadership in empowering employees seems to strongly depend on the clarity of leadership and ethical guidance (Wood et al., 2021), which has implications for the development of effective policies for promoting green behaviors in actionable and meaningful ways. Leaders are responsible for managing the communication of expectations relating to sustainable actions as well as providing ongoing support to help employees, allowing for a better understanding of their individual efforts and contributions towards collective environmental outcomes. Ren et al. (2021) stated that waste reduction allows for ambiguity regarding the increase in the sense of ownership of employees when describing green initiatives.

The presentation of authentic vs. performative green behaviors is associated with the sincerity, consistency, and underlying motivations of leaders, affecting their efficiency in the management of environmental actions (Li et al., 2023). There are some authentic approaches to the management of green behaviors, characterized by a genuine concern for environmental impacts, demonstration of consistent actions and behaviors, voluntary management of actions such as energy and waste reductions, and actively participating in sustainable initiatives. Islam et al. (2021) reported that employees who are shown authentic behaviors tend to use the definite resources of integrated policies in their daily routines. Furthermore, alignment between personal and organizational values helps employees to be inspired by ethical leaders who lead by example. Fatoki (2023) stated that authentic green behaviors reflect an intrinsic motivation to provide a deeper commitment to environmental stewardship, instead of external rewards and planned recognition.

In comparison, performative policies for green behaviors are generally perceived by employees as symbolic actions that are primarily used to garner a positive image and meet compliance requirements without any real commitment (Hameed et al., 2022). Examples include token gestures for the management of recycling and participating in green programs that are solely based on fulfilling organizational objectives. Performative behaviors tend to lead to a lack of consistent behaviors in employees and fail to have an effective influence on the broader organizational culture and the related sustainability outcomes (Al Halbusi et al., 2021). Behaviors will only truly change due to effective and authentic leaders, while those preferring the substantive use of environmental responsibilities for performative purposes lead to an effective reduction in employee engagement with respect to genuine green efforts (Ahmed et al., 2022).

5.3. Integration with Theory

The findings of this study strongly support Social Learning Theory. Ethical leaders often show daily green actions in the workplace, which employees then watch and copy in their routine work; for example, turning off lights can become a shared daily habit. Many staff also promote paperless work after seeing their leaders do the same. These small actions lead to the creation of a larger culture of sustainable behavior at work. Employees learn by watching their leaders, not just through formal training, demonstrating the power of observational learning in daily business life. The actions of leaders speak louder than policy documents or written instructions, as employees trust what they see over what they read. Over time, these habits become a normal part of work for many employees (Ahmed et al., 2022), supporting the idea that social learning shapes real workplace behaviors. Employees find it natural to follow what leaders do every day, with their motivation growing through the direct observation of sustainable choices.

The study also supports Value–Belief–Norm Theory described by Ahmad et al. When leaders explain why sustainability is central to an organization’s mission, they shape employees’ beliefs about their moral duties, helping the employees to feel personally responsible to act in greener ways. This sense of responsibility does not come from rules alone but, rather, from shared values. These values can be discussed openly in meetings and internal messages. Leaders talk about the moral reasons for protecting the environment, helping staff to see green actions as part of who they were. The results of this study reveal that shared values turn into real daily practices, with many employees linking their green behaviors directly to these shared beliefs. They see their actions as expressions of moral duty, not just tasks, and this connection makes them feel proud to act sustainably at work.

The research findings also support Environmental Stewardship Theory. Employees view leaders as caretakers of the future environment as leaders often share stories about caring for future generations, thus encouraging staff to think beyond short-term business goals. The employees stated that such messages make them feel as though they are part of something bigger, seeing themselves as helping to protect the world for others. Leadership narratives cause employees to care about long-term environmental impacts, demonstrating that storytelling and vision are powerful tools for leadership. Employees become more committed when leaders share this broader vision, helping them to feel as though they are part of a collective mission to reduce harm to nature. However, the findings also showed where theory and practice can differ. Some staff stated that while clear job roles helped, they did not serve to fully change behaviors. Structure and clarity without moral framing seem to have weaker effects, with people following green practices best when supported by values and role models. The results suggest that knowledge and rules alone do not inspire lasting change; in contrast, ethical framing and daily modeling by leaders create deeper commitment. Without shared moral meaning, green policies risk becoming empty checklists. Staff need to understand why sustainability matters beyond business-related benefits, and leaders must connect their daily actions to shared values and wider goals. This integration of values makes sustainable action feel normal and important. Observational learning, shared beliefs, and stewardship messages work best together, serving to build a workplace culture in which green behaviors feel right and expected. Leaders must show, explain, and care for the environment openly. Consequently, employees will then feel both empowered and morally driven to act sustainably. Together, these theories help to explain how real change happens in the workplace. This study highlights the need for ethical leadership in daily practice—in the end, true change comes from people leading by honest example.

5.4. Practical Implications

For leaders in higher education institutions, this study offers useful guidance. Leaders should build ethical leadership skills through practical and targeted training sessions (Blaich et al., 2023). These sessions must cover real-life topics such as leading green projects and open talks. Leaders can learn how to show sustainable habits in their daily life. Training should also involve teaching them to speak clearly about their environmental values and plans, which helps staff to see that green behaviors are not just words. Leaders must also act in ways that match their communicated values, which will make staff more likely to copy these habits in their own daily work life. Leaders must also aim to make sustainability a shared value for everyone involved; this means integrating green goals into the mission of the institution itself. Performance reviews should involve measurements regarding how staff and managers support eco-friendly plans. Reward systems can provide real incentives for staff to lead or join green actions: when a green behavior is rewarded, it feels like a normal part of the culture (Hooi et al., 2022) and becomes something staff do naturally, instead of seeing it as extra work. In addition, leaders should open safe spaces for honest talks about sustainability ideas, and staff should feel free to suggest new projects without any fear of blame.

Leaders can publicly thank those who come forward with useful green ideas. Recognition in this way helps build a sense of shared ownership of green goals. It also follows power-sharing principles, where everyone can shape what happens. Such a shared approach makes staff feel more motivated to volunteer and get involved. Another step is to bring ethical guidance into everyday management processes. Leaders should receive clear tools and guides regarding the discussion of ethical choices, which can help them to handle conflicts relating to costs versus environmental gains and makes it easier to keep green values alive in daily meetings. Linking sustainability work to national goals is also very important in the UAE (Alkhaldi et al., 2023). Institutions can explain how their local actions support the UAE’s larger green vision, which can build pride in staff and help them to feel part of something bigger. When staff see how their small actions match national goals, their motivation grows stronger. Pride in national progress helps to turn abstract plans into real daily habits. Leaders should also support authentic, bottom-up green work instead of symbolic gestures. Staff should help to create sustainability plans, rather than having them forced from above. Co-created projects are usually more practical, better accepted, and longer lasting, helping to avoid the problem where staff pretend to support green work but do not act. Authentic engagement turns green behaviors from additional work into a daily routine. Leaders should also stay alert to signs of symbolic or half-hearted compliance. They can do this by asking for feedback, listening, and checking outcomes. Honest reviews help to keep plans grounded and focused on real change, instead of just image. These steps can help leaders to guide staff towards the adoption of true green habits. Ethical leadership becomes visible through daily choices, open dialogue, and shared ownership. Rewards and reviews allow sustainability to become part of how success is measured on an annual basis.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers valuable findings, it still has several important limitations. First, it relied on self-reported data, which may have introduced some bias; in particular, the respondents may have given answers that they feel are socially acceptable instead of true. Future work could include observational studies for the confirmation of actual employee behaviors. Second, the study was limited to higher education institutions in the UAE. The cultural context and institutional systems may shape these results strongly (Kaasa & Andriani, 2022), and the findings might not directly apply to other countries or industries. Third, the research design was cross-sectional, and thus, covered only one moment in time. Such a design makes it hard to fully determine true causal relationships. Future research could use a longitudinal design to track changes over time, allowing for determination regarding whether ethical leadership causes shifts in employee green behaviors. Another idea is to explore further moderation effects, such as those relating to institutional culture and structure, which might strengthen or weaken the link between ethical leadership and green behavior. Testing such moderating factors could help to explain the differences in results across contexts. Future work might also include the testing of mediation models to clarify the process; for instance, employee values or psychological safety might act as mediators. These mediators could reveal how ethical leadership leads to more green behaviors.

Understanding these pathways can help leaders to design better sustainability strategies. Comparing higher education institutions with private sector organizations could generate additional insights (Małkowska et al., 2021). Such comparisons could reveal whether ethical leadership has the same effect in different industrial contexts, as well as revealing sector-based differences and cultural influences more clearly. Future research could also directly assess interventions for the improvement of ethical leadership. Measuring employee green behaviors before and after training sessions could test their effectiveness. Longitudinal studies allow for determination of whether behavioral changes last over time or fade. Research could include expanded mixed-methods approaches; for example, including interviews and focus groups. This could add depth and context beyond what surveys alone can offer. More diverse samples from various countries and industries would increase the generalizability of the obtained results. Larger and more varied samples might reveal new patterns or confirm existing trends. Testing different leadership styles alongside ethical leadership may also be valuable (Fischer & Sitkin, 2023), and could indicate whether ethical leadership has a unique effect on green behaviors. Studies might also explore personal factors, such as employees’ green values and beliefs. These personal factors may interact with leadership and shape behaviors further. Future research should also investigate external pressures such as regulations and market demands, which could serve to increase or decrease the effects of ethical leadership. Examining organizational policies and reward systems could validate the efficacy of supportive structures; particularly whether they help employees to transform green intentions into real actions.

6. Conclusion

In short, this study explored how ethical leadership shapes employee green behaviors in HEIs in the UAE. The research combined survey results and interviews obtained from academic staff as participants. The findings reveal that leaders who care about sustainability strongly shape the daily green choices of employees. Leaders offering ethical guidance help employees to act responsibly towards the environment in their daily lives, and leaders who show a people-oriented approach can inspire real commitment to green practices. Together, these leadership qualities build a stronger pro-environmental culture in institutions. The results support ideas derived from Social Learning Theory and the VBN framework; in particular, employees tend to copy leaders’ actions and embrace shared environmental values deeply. The interviews also revealed differences between real and performative green behaviors. Employees perceived when leaders’ actions matched their words or were only symbolic. This difference demonstrates the power of authenticity in encouraging greener daily habits. National and cultural values in the UAE were considered to have amplified the effects of ethical leadership, and leaders working in this cultural context may influence green attitudes to a greater extent. As a result, it is suggested that universities should invest in ethical leadership training for managers, embedding environmental values into daily operations strengthens commitment across all staff groups, and focusing on authentic actions matters more than showing off green policies publicly.

Universities should avoid only symbolic steps and instead promote genuine behavioral change. Encouraging staff to share green ideas can build a deeper culture. Training leaders to show care for people makes green goals more achievable, and approaches to leadership that include clear ethical guidance supports consistent and visible green actions. In practice, universities should align their internal policies with ethical and environmental values. This research had some limitations, including its focus on HEIs in the UAE and using self-reported data, which may have resulted in biased responses. Future research could use observational designs or data from multiple countries to better balance the obtained results. Despite these limitations, the study offers important insights for leaders in higher education. Ethical leadership is more than words; it creates real cultural change. Staff who see their leaders model green behaviors are more likely to do the same. Universities that invest in these practices can build truly sustainable campuses. Teaching future graduates the importance of ethical leadership enables change to spread widely, and preparing students to face environmental challenges tomorrow starts with campus leadership today. Finally, ethical leadership remains a strong driver of positive green behaviors. With clear guidance and genuine care, leaders help to shape long-term institutional sustainability. This study demonstrates how leadership in universities can meaningfully impact environmental progress. This study’s findings can help to build greener campuses and influence the beliefs and actions of future generations. Overall, developing ethical leaders in educational settings is essential for ensuring a more sustainable future.