1. Introduction

Metanephrine and normetanephrine are catecholamines secreted by the adrenal medulla [

1,

2]. Metanephrines are synthesized from L-tyrosine [

3]. Tyrosine hydroxylase converts L-tyrosine into dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), which is then converted to dopamine by DOPA decarboxylase [

4]. Dopamine is converted to norepinephrine and epinephrine, which are then converted to metanephrine by catechol-O-methyltransferase.

Some adrenal gland tumors produce large amounts of catecholamines, which are broken down to produce metanephrines. The most common adrenal gland tumors are pheochromocytomas and neuroblastomas. Pheochromocytomas are paragangliomas that arise within the adrenal gland [

5], whereas neuroblastoma starts in cells called neuroblasts and occurs in the adrenal glands primarily during childhood [

6].

Pheochromocytomas are primarily diagnosed through biochemical screening. First, plasma-free and urinary metanephrine levels are measured. Using epinephrine as a screening marker is less sensitive than using metanephrine [

7,

8]. Analysis of urinary metanephrines is also less sensitive and require patients to collect 24-h urine samples [

9,

10]. Therefore, measurement of plasma-free metanephrine levels is preferred for diagnosing pheochromocytomas [

11,

12]. If these levels are less than three times the upper limit of the normal range, a clonidine suppression test is considered [

13]. If the result is more than three times the upper limit of the normal range, a tumor is highly suspected; in this case, tumor characterization is performed using radiological imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging [

14].

Metanephrines are present at low concentrations in plasma, however, can be concentrated in plasma samples using solid-phase extraction (SPE) [

15]. SPE can be used to purify and concentrate analytes based on their physical and chemical properties. In this study, metanephrines were concentrated using weak cation-exchange SPE because of their weakly acidic nature. Subsequently, liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was performed to detect metanephrines [

16]. LC-MS/MS offers greater sensitivity, specificity, and speed than conventional methods such as electrochemical and fluorometric detection [

17,

18,

19]. In this study, we validated a method for diagnosing pheochromocytomas by detecting metanephrines using SPE and LC-MS/MS.

2. Results

2.1. Accuracy

Accuracies for metanephrine and normetanephrine were 96.3–101.5 % and 95.7–98.1 %, respectively (

Table 1). Accuracy was evaluated at three concentration levels using FDA Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidance (±15 %; ±20 % at LLOQ) and CLSI C50-A criteria.

2.2. Precision

The precision was evaluated in two ways, within-run and between-run tests. In the within-run test, identical samples were analyzed for 20 d. The accuracies were 96.5–99.8% and the coefficients of variation (CVs) were 1.4–4.2% satisfying the acceptance criteria. In the between-run test, identical samples were analyzed twice per day, with a time gap of at least 4 h between for five days. The accuracies were 93.1–100.7% and CVs were 1.7–7.0% which also satisfied the acceptance criteria (

Table 2).

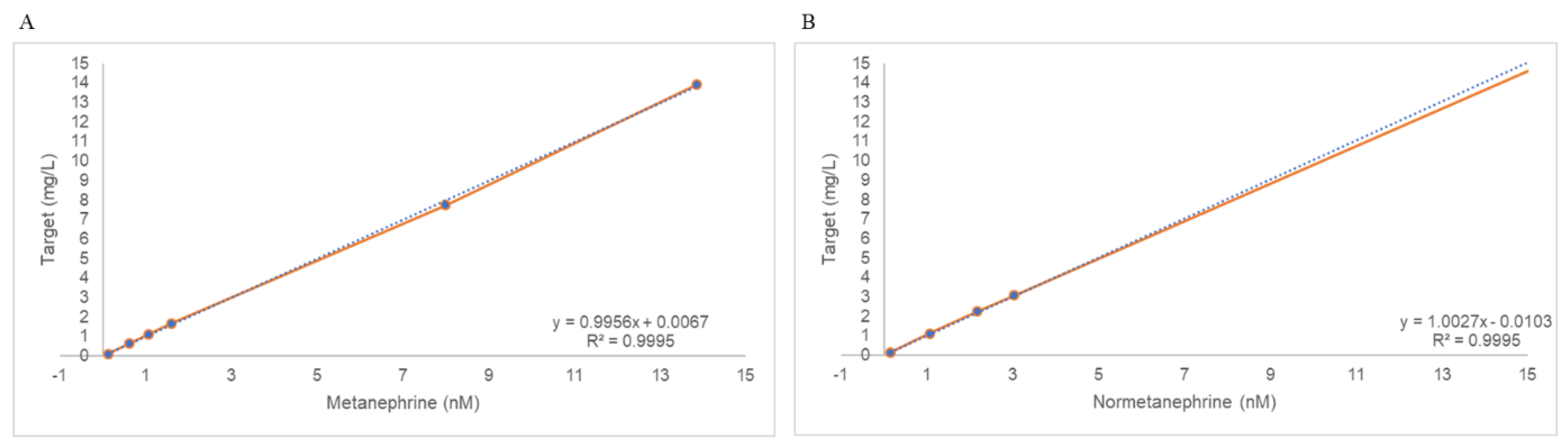

2.3. Linearity

The concentration ranges used to validate linearity were 0.11–13.92 nmol/L for metanephrine and 0.14–26.43 nmol/L for normetanephrine. The recovery rate at each level was less than 15%. The regression equations for metanephrine were y = 0.9956x + 0.0067 (R

2 = 0.9995) and y = 1.0027x + 0.0103 (R

2 = 0.9995) (

Figure 1). All R

2 values were greater than 0.95, thus satisfying the acceptance criteria.

2.4. Carryover

An F-test was conducted prior to the

t-test. The

p-values of the F-tests were less than 0.5, demonstrating that the low 1 and 3 groups had equal variance. Homoscedastic

t-tests were performed. The

p-values of the

t-tests were less than 0.05. No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups (

Table 3).

2.5. Lower Limit of Quantification

The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was determined by analyzing the diluted control samples. The expected concentrations were 0.061–0.307 nmol/L for metanephrine and 0.108–0.541 nmol/L for normetanephrines. The lowest concentration that satisfied an accuracy within 100 ± 15% and CV% of less than 20% was determined. In determined to be 0.123 and 0.432 nmol/L for metanephrine and normetanephrine, respectively.

Table 4.

Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) for Plasma Metanephrine and Normetanephrine Determined by SPE–LC-MS/MS.

Table 4.

Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) for Plasma Metanephrine and Normetanephrine Determined by SPE–LC-MS/MS.

| Analyte |

Expected concentration (nmol/L) |

Average concentration (nmol/L, n = 5) |

CV

(%) |

Accuracy

(%) |

| Metanephrine |

0.307 |

0.301 |

3.9 |

98.1 |

| |

0.245 |

0.247 |

2.8 |

100.7 |

| |

0.184 |

0.185 |

2.9 |

100.4 |

| |

0.123 |

0.126 |

5.5 |

102.8 |

| |

0.061 |

0.072 |

7.3 |

118.1 |

| Normetanephrine |

0.541 |

0.502 |

10.9 |

92.8 |

| |

0.432 |

0.409 |

11.0 |

94.6 |

| |

0.324 |

0.272 |

6.4 |

84.0 |

| |

0.216 |

0.150 |

37.1 |

69.6 |

|

0.108 |

0.072 |

27.1 |

66.8 |

2.6. Ion Suppression

The matrix effect, recovery, and process efficiency were verified by comparing samples spiked with the drug and internal standard (IS) before (sample A) and after (sample C) SPE, and the drug and IS spiked with 90% acetonitrile (sample B). The results are presented in

Table 5. The peak areas of the samples were normalized to the IS peak area. The normalized results are listed in

Table 5. All three tests were performed within 100 ± 15%. The IS-normalized recovery rates were 86–112% and 98–112% for the IS-normalized matrix effect and 92–121% for the IS-normalized process efficiency at all metanephrine concentrations. The lowest metanephrine concentration was 15%.

3. Discussion

Plasma-free metanephrines are recognized as sensitive and specific biochemical markers for the screening of catecholamine-secreting tumors, specifically pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas, and outperform urinary epinephrine, norepinephrine, and vanillylmandelic acid in terms of diagnostic accuracy. Consequently, the Endocrine Society guidelines recommend plasma-free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines measured using LC–MS/MS as the first-line screening test, provided that critical pre-analytical factors, supine collection, EDTA anticoagulation, prompt cooling, and strict drug exclusion are controlled [

20]. In this context, our SPE–LC–MS/MS method was designed to exceed clinical expectations. Validation data confirmed that it achieved sub-nanomolar limits of quantification, excellent linearity, and robust accuracy and precision across clinically relevant ranges.

The sub-nanomolar limits of quantification achieved using our method (0.07 nmol/L for metanephrine and 0.11 nmol/L for normetanephrine) are comparable to those reported in similar LC–MS/MS applications [

21,

22,

23]. These sensitivity levels exceed the analytical requirements for clinical diagnosis, where plasma metanephrine concentrations typically range from 0.3–2.5 nmol/L in healthy individuals [

2]. The excellent linearity (R² > 0.999), robust accuracy, and precision across validated ranges confirmed the suitability of the method for quantitative analysis, which was consistent with the validation criteria established in previous LC–MS/MS metanephrine assays [

23,

24].

In this study, a weak cation exchange approach was employed for SPE, which allowed the metanephrines to be retained on the SPE cartridge and eluted in a smaller volume than that of the original plasma sample. This concentration step enhances the detectability of analytes using LC-MS/MS, offering superior sensitivity and selectivity compared to traditional methods such as electrochemical or fluorometric detection. The concentration step in SPE addresses key analytical challenges in plasma metanephrine measurements [

25].

To evaluate the matrix effect, process efficiency was assessed by comparing the analyte response in the plasma spiked before extraction (sample A) with that in the neat solution (sample B). At the lowest concentration, metanephrine showed a process efficiency of 121%, exceeding the acceptable range of 100 ± –15%. This may be attributed to matrix-induced ion enhancement, which tends to be more prominent at lower analyte concentrations [

26]. In addition, the variability in the SPE recovery at low concentrations may have contributed to the elevated response. Because sample A underwent SPE with the analyte present in the plasma, whereas sample B lacked matrix components, differences in ionization efficiency or recovery could explain this discrepancy.

Previous studies reported similar matrix effects in plasma metanephrine analyses. The magnitude of matrix effects can vary depending on the sample preparation method, with SPE typically providing better matrix cleanup than simple protein precipitation [

27]. However, complete elimination of matrix effects remains challenging, particularly at low analyte concentrations, where the signal-to-noise ratio is most vulnerable to matrix interference [

28,

29].

The clinical significance of our findings must be interpreted in the broader context of diagnostic performance. Although the elevated process efficiency at low concentrations represents a deviation from the ideal analytical conditions, the method maintained acceptable accuracy and precision across all tested concentrations. This result suggests that the matrix effect, although present, did not compromise the quantitative reliability of the assay within a clinically relevant concentration range.

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting our results. First, the elevated process efficiency at low metanephrine concentrations represents a deviation from ideal analytical conditions, which may introduce systematic bias in measurements near the LLOQ. Although the clinical impact appears minimal, given the maintained accuracy and precision, this finding suggests that the method can be further optimized.

Matrix-effect evaluation is limited to pooled plasma, an approach that masks the biological heterogeneity encountered in clinical specimens, and therefore may underestimate ion suppression or enhancement arising from patient-specific factors such as co-medications [

30]. Individual samples can exhibit variable matrix interference. Additionally, certain drugs, including tricyclic antidepressants, sympathomimetics, and proton pump inhibitors, alter endogenous metanephrine concentrations or confound their measurements. Future validation studies should extend matrix effect and interference testing to a broad range of patient samples representative of diverse pharmacological and pathological backgrounds to strengthen the analytical robustness and clinical applicability of the method.

This study did not include a clinical performance evaluation to compare our method with established diagnostic criteria or alternative analytical approaches. Although our analytical validation confirmed the technical adequacy of this method, a direct correlation with diagnostic outcomes would provide stronger evidence of its clinical utility.

Despite these limitations, the method showed acceptable process efficiency at all tested concentrations (86–121 % across 0.6–5.0 nmol L⁻¹). The accuracy and precision criteria were consistently met across the calibration range, thereby supporting the overall robustness and reliability of the method. Even if small deviation was present, further optimization, such as using matrix-matched calibration standards or improving the extraction protocol, may help reduce variability and increase reproducibility in future applications.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade water, acetonitrile, and methanol (J.T. Baker, Philipsburg, NJ, USA) were used for all experimental processes and solutions in LC. LC-MS-grade formic acid (Optima, Waltham, MA, USA) and ammonium formate (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) were used as additives in the mobile phase solutions. D,L-metanephrine hydrochloride (≥98%, HPLC, Sigma-Aldrich. St. Louis, MO, USA) and D,L-normetanephrine hydrochloride (≥98%, Sigma-Aldrich) were used in this experiment. Plasma calibration standards, controls, IS, and the tuning mix were obtained from ChromSystems (Munich, Germany). Plasma calibration standards and controls were rehydrated with HPLC-grade water according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.2. Sample Preparation

The plasma calibration and control samples were stored at 4 °C. After rehydration and aliquoting, calibration and control samples were stored at -40 °C until use. The IS were also stored at -40 ℃. Patient plasma was collected from EDTA whole blood samples, centrifuged at 2,300 × g for 10 min, and stored at 4 °C until use.

4.3. SPE

Metanephrines can be extracted using SPE with weak cation exchange. Strata-X solid-phase extraction chromatography (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) was performed. The SPE system was conditioned with methanol (1 mL) and equilibrated with 1 mL of water. Plasma samples were prepared for loading, diluted with 0.1% formic acid in water, and centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 10 min. Next, 1 mL of the diluted sample was added. During the washing step, 1 mL of methanol and 1 mL of water were added sequentially. Finally, 5% formic acid in acetonitrile was used for elution. The eluted samples were dried under nitrogen gas at 40 °C for 1 h and then reconstituted in a solution with the same composition as the initial LC solution.

4.4. Analytical Procedure

The analytical instrument used was a Sciex Exion liquid chromatograph combined with a Sciex QTAP5500 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). The analytical column used in this experiment was an Acquity UPLC BEH Amide column with a 1.7 μm C18 sorbent (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Its reversed-phase C18 stationary phase, coupled with ultra-HPLC, allows for efficient separation and detection of metanephrine. The temperature of the column oven was maintained at 60 ℃. The mobile phase for LC was 20 mM ammonium formate in 0.1% formic acid (solution A) and 100% methanol (solution B). The total flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. The equilibration and initial conditions for LC were 90% solution B. During the analysis, the concentration of solution B was maintained at 90% for 1 min, and then a linear gradient was applied from 90% to 65% for 1.5 min. It was decreased to 40% after 1 min. The concentration of solution B was returned to 90% for equilibration and stabilization before the next run. The run time was 5 min.

For MS analysis, electrospray ionization was used as the ion source, and collision-induced dissociation occurred in the Q2 collision cell. Only positive polarity was used to analyze the metanephrines. The multiple reaction monitoring method was used to analyze known analytes because of its ability to evaluate multiple ions in one run. The multiple reaction monitoring conditions, including ion transitions of the precursor and product ions, retention time, declustering potential, collision energy, and collision cell exit potential, are listed in

Table 6. The parameters for the mass spectrometer were curtain gas, 45.0 psi; collision gas, medium; ion spray voltage, 2,500.0 V; temperature, 600.0 °C; ion source gas 1, 50.0 psi, gas 2, 55.0 psi; entrance potential, 10.0 V. A MultiQuant MD 3.0.2 (AB SCIEX) was used to quantify the metanephrines.

4.5. Method Validation

The laboratory-developed test followed the Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidance for Industry (FDA, Docket number FAD-2013-D-1020, 2018) and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guideline C50-A. The validation methods were partially modified [

31,

32].

4.5.1. Accuracy

Control samples (mass check-free metanephrine plasma controls, ChromSystems) were used to investigate the accuracy. Three concentration levels (0.30, 0.93, 4.94 mg L⁻¹) of plasma controls were analysed (n = 20) to determine accuracy (% bias). Average values and biases were calculated to determine accuracy. The passing criterion was a bias of less than 15%, with the lowest level of bias being less than 20%.

4.5.2. Precision

Low- and high-level control samples were used. To evaluate within-run precision, Low (0.30 mg L⁻¹) and high (4.94 mg L⁻¹) concentration controls were measured for 20 d. To examine between-run precision, two levels of control samples were measured in the morning and afternoon (time interval of more than 4 h) for 5 d. The accuracy of both evaluations was within 100 ± –15%. The CV was set to less than 20%.

4.5.3. Linearity

Calibration standards (6PLUS1® Multilevel Plasma Calibrator Set Free Metanephrines, ChromSystems) were used to evaluate linearity. The six calibration standards were tested five times. The average of five results was calculated and compared with the target value according to the standard concentration in the data sheet. The coefficient of determination (R2) of the regression was greater than 0.95. The recovery percentage was within 100 ± –15%.

4.5.4. Carryover

Low and high concentrations of control samples were used to evaluate carryover (residual analyte detected in a subsequent blank or low-concentration sample). Carryover was examined by consecutively measuring three high-concentration control samples and three low-concentration control samples, which was repeated 10 times. To evaluate carryover, ten results of the first measured low concentration (low 1) control samples and last measured low concentration control samples (low 3) were statistically analyzed. F-tests were conducted for both groups (low 1 and 3). If the F-test results indicated equal variances in these groups, an equal-variance t-test was performed. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicated no difference between the two groups or no carryover.

4.5.5. LLOQ

The lowest concentration in the control was used to determine the LLOQ. Expected concentrations were dictated by serial 1 : 2 dilutions of the manufacturer’s lowest calibrator. The expected concentrations were 0.307–0.061 nmol/L for metanephrines and 0.541–0.108 nmol/L for normetanephrine. Each diluted sample was analyzed five times. The average of the five results was statistically analyzed and the accuracy was calculated. The accuracy should be within 100 ± 15% with a CV% of less than 20%. The lowest concentration that satisfied these two conditions was considered the LLOQ of the analyte.

4.5.6. Ion Suppression

The matrix effects of the metanephrine detection methods, including SPE, were evaluated by comparing drug spiking before and after sample preparation. Concentrations of 0.6, 1.3, 2.5 nmol/L for metanephrine and 1.3, 2.5, 5.0 nmol/L for normetanephrines were prepared. Three types of samples were prepared: samples spiked with the drug and IS before SPE (sample A), drug- and IS-spiked reconstitution solution without SPE (sample B), and samples spiked with the drug and IS after SPE before drying with nitrogen gas (sample C).

The results were calculated based on the peak areas. The matrix factor was evaluated by comparing samples B and C, with the difference being whether the matrix was plasma. Recovery was evaluated by comparing differences in spiking timing. Spiking of the drug and IS before (sample A) and after (sample C) SPE allowed for recovery from the SPE procedure. Process efficiency was evaluated by comparing samples A and B. IS were used to normalize the peak area. Normalized results were calculated using the same procedure employed for routine clinical-specimen reporting. The results were within the range of 100 ± 15%. Sample A = plasma + analyte/IS (pre-SPE); Sample B = 90 % acetonitrile + analyte/IS (no matrix); Sample C = plasma (post-SPE) spiked after extraction.

5. Conclusions

We established and validated a sensitive and reliable LC-MS/MS method for quantifying metamachine and normetanephrine in human plasma. The method met all major bioanalytical validation criteria and was suitable for routine clinical use in the screening of catecholamine-secreting tumors. The minor variability observed at low concentrations did not compromise the overall performance of the method, and the technique offers significant advantages over traditional detection methods in terms of speed, accuracy, and diagnostic applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and S.G.Y.; methodology, H.C.; software, H.C.; validation, H.C., J.Y. and J.K.L.; formal analysis, H.C.; investigation, H.C.; resources, S.G.Y.; data curation, H.C. and S.G.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C. and S.G.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.G.Y.; visualization, H.C. and S.G.Y.; supervision, J.Y., J.K.L., K.J.K., M.N., M.H.N., Y.C. and S.G.Y.; project administration, S.G.Y.; funding acquisition, S.G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) ( RS-2024-00393002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Anam Hospital (2025AN0183) on 28 April 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board because the study used fully de-identified residual plasma specimens obtained during routine clinical testing, which posed no more than minimal risk to subjects.

Data Availability Statement

None

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, o3; accessed 7 August 2025) solely for English-grammar proofreading and refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited all AI-generated output and assume full responsibility for the final content of this publication. The authors also thank Editage (

www.editage.co.kr) for professional English-language editing support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CV |

Coefficient of variation |

| DOPA |

Dihydroxyphenylalanine |

| HPLC |

High-performance liquid chromatography |

| IS |

Internal standard |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry |

| LLOQ |

Lower limit of quantification |

| SPE |

Solid-phase extraction |

References

- De Silva, D.C.; Wijesiriwardene, B. The adrenal glands and their functions. Ceylon Medical Journal. 2009, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhofer, G.; Lattke, P.; Herberg, M.; Siegert, G.; Qin, N.; Därr, R.; Hoyer, J.; Villringer, A.; Prejbisz, A.; Januszewicz, A.; et al. Reference intervals for plasma free metanephrines with an age adjustment for normetanephrine for optimized laboratory testing of phaeochromocytoma. Ann Clin Biochem. 2013, 50, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.C.; Ho, P.C. Chromatographic measurements of catecholamines and metanephrines. Chromatographic Methods in Clinical Chemistry and Toxicology. 2007, 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Meiser, J.; Weindl, D.; Hiller, K. Complexity of dopamine metabolism. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2013, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacak, K.; Linehan, W.M.; Eisenhofer, G.; Walther, M.M.; Goldstein, D.S. Recent advances in genetics, diagnosis, localization, and treatment of pheochromocytoma. Annals of internal medicine. 2001, 134, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson Jr, A.G.; Strong, L. Mutation and cancer: neuroblastoma and pheochromocytoma. American journal of human genetics. 1972, 24, 514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, M.; Serlin, I.; Edwards, T.; Rapport, M.M. Chemical screening methods for the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: I. Nor-epinephrine and epinephrine in human urine. The American Journal of Medicine. 1954, 16, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythe, G.; Edwards, G.; Graham, P.; Lazarus, L. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma by simultaneous measurement of urinary excretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine. Clinical chemistry. 1992, 38, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, J.W.; Keiser, H.R.; Goldstein, D.S.; Willemsen, J.J.; Friberg, P.; Jacobs, M.-C.; Kloppenborg, P.W.; Thien, T.; Eisenhofer, G. Plasma metanephrines in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Annals of internal medicine. 1995, 123, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, W.; Raffesberg, W.; Bischof, M.; Scheuba, C.; Niederle, B.; Gasic, S.; Waldhäusl, W.; Roden, M. Diagnostic efficacy of unconjugated plasma metanephrines for the detection of pheochromocytoma. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000, 160, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhofer, G. biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma—is it time to switch to plasma-free metanephrines? The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2003, 88, 550–552. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer, G.; Walther, M.; Keiser, H.; Lenders, J.; Friberg, P.; Pacak, K. Plasma metanephrines: a novel and cost-effective test for pheochromocytoma. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2000, 33, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, E.; Goldstein, D.S.; Hoffman, A.; Keiser, H.R. Glucagon and clonidine testing in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Hypertension. 1991, 17, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappachan, J.M.; Tun, N.N.; Arunagirinathan, G.; Sodi, R.; Hanna, F.W. Pheochromocytomas and hypertension. Current hypertension reports. 2018, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, W.H.; Graham, K.S.; van der Molen, J.C.; Links, T.P.; Morris, M.R.; Ross, H.A.; de Vries, E.G.; Kema, I.P. Plasma free metanephrine measurement using automated online solid-phase extraction HPLC–tandem mass spectrometry. Clinical chemistry. 2007, 53, 1684–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petteys, B.J.; Graham, K.S.; Parnás, M.L.; Holt, C.; Frank, E.L. Performance characteristics of an LC–MS/MS method for the determination of plasma metanephrines. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2012, 413, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, W.H.; de Vries, E.G.; Kema, I.P. Current status and future developments of LC-MS/MS in clinical chemistry for quantification of biogenic amines. Clinical biochemistry. 2011, 44, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peaston, R.T.; Graham, K.S.; Chambers, E.; van der Molen, J.C.; Ball, S. Performance of plasma free metanephrines measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Clinica chimica acta. 2010, 411, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, J.; Eisenhofer, G.; Armando, I.; Keiser, H.; Goldstein, D.; Kopin, I. Determination of metanephrines in plasma by liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Clinical chemistry. 1993, 39, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenders, J.W.; Duh, Q.Y.; Eisenhofer, G.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.P.; Grebe, S.K.; Murad, M.H.; Naruse, M.; Pacak, K.; Young, W.F., Jr.; Endocrine, S. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014, 99, 1915–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhofer, G.; Prejbisz, A.; Peitzsch, M.; Pamporaki, C.; Masjkur, J.; Rogowski-Lehmann, N.; Langton, K.; Tsourdi, E.; Pęczkowska, M.; Fliedner, S.; et al. Biochemical Diagnosis of Chromaffin Cell Tumors in Patients at High and Low Risk of Disease: Plasma versus Urinary Free or Deconjugated O-Methylated Catecholamine Metabolites. Clin Chem. 2018, 64, 1646–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, X.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Xiao, H.; Cao, X. ACCURACY OF PLASMA FREE METANEPHRINES IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA AND PARAGANGLIOMA: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS. Endocr Pract. 2017, 23, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Luo, X.; Li, H.; Guan, Q.; Cheng, L. A simple and robust liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay for determination of plasma free metanephrines and its application to routine clinical testing for diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Biomed Chromatogr. 2019, 33, e4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismann, D.; Peitzsch, M.; Raida, A.; Prejbisz, A.; Gosk, M.; Riester, A.; Willenberg, H.S.; Klemm, R.; Manz, G.; Deutschbein, T.; et al. Measurements of plasma metanephrines by immunoassay vs liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry for diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015, 172, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.W.; Cooke, B.; Hoad, K.; Glendenning, P. Improved plasma free metadrenaline analysis requires mixed mode cation exchange solid-phase extraction prior to liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry detection. Ann Clin Biochem. 2011, 48, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbelman, A.C.; van Wieringen, B.; Roman Arias, L.; van Vliet, M.; Vermeulen, R.; Harms, A.C.; Hankemeier, T. Strategies for Using Postcolumn Infusion of Standards to Correct for Matrix Effect in LC-MS-Based Quantitative Metabolomics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2024, 35, 3286–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R. Quantitative Measurement of Plasma Free Metanephrines by a Simple and Cost-Effective Microextraction Packed Sorbent with Porous Graphitic Carbon and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Anal Methods Chem. 2021, 2021, 8821276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, W.; Picard, F. Assessment of matrix effect in quantitative LC-MS bioanalysis. Bioanalysis. 2024, 16, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Faassen, M.; Bischoff, R.; Eijkelenkamp, K.; de Jong, W.H.A.; van der Ley, C.P.; Kema, I.P. In Matrix Derivatization Combined with LC-MS/MS Results in Ultrasensitive Quantification of Plasma Free Metanephrines and Catecholamines. Anal Chem. 2020, 92, 9072–9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, C. Commutability Assessment of Processed Human Plasma Samples for Normetanephrine and Metanephrine Measurements Based on the Candidate Reference Measurement Procedure. Ann Lab Med. 2022, 42, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Yim, J.; Cha, J.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.J.; Nam, M.; Nam, M.H.; Lee, C.K.; Cho, Y.; Yun, S.G. HPLC-MS/MS Method Validation for Antifungal Agents in Human Serum in Clinical Application. Clinical Laboratory. 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Choi, H.; Cha, J.H.; Kim, J.; Nam, M.-H.; Nam, M.; Lee, C.K.; Cho, Y.; Yun, S.G. Development and Validation of a U-HPLC-MS/MS Method for the Concurrent Measurement of four Immunosuppressants in Whole Blood. Clinical Laboratory. 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).