1. Introduction

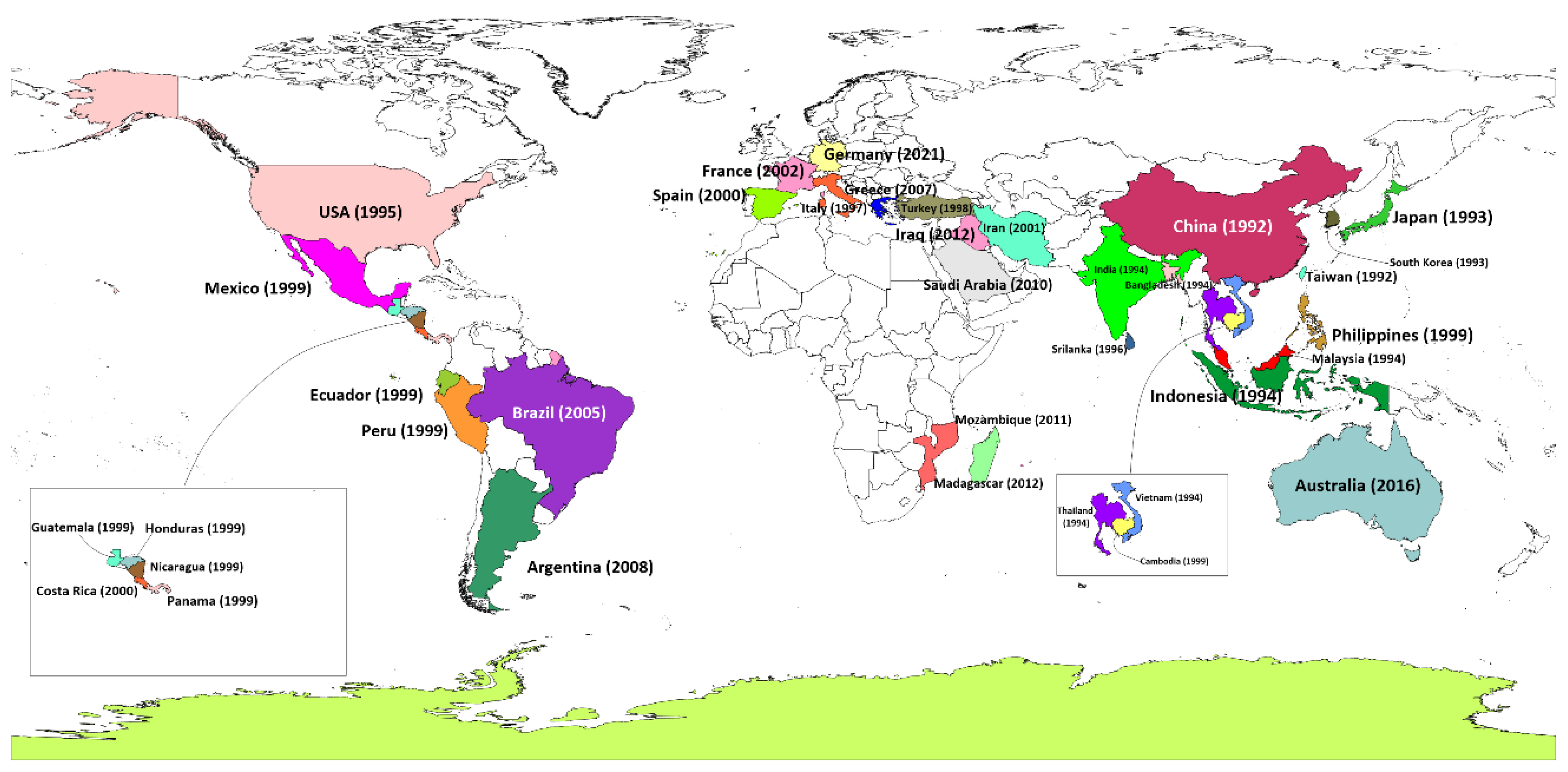

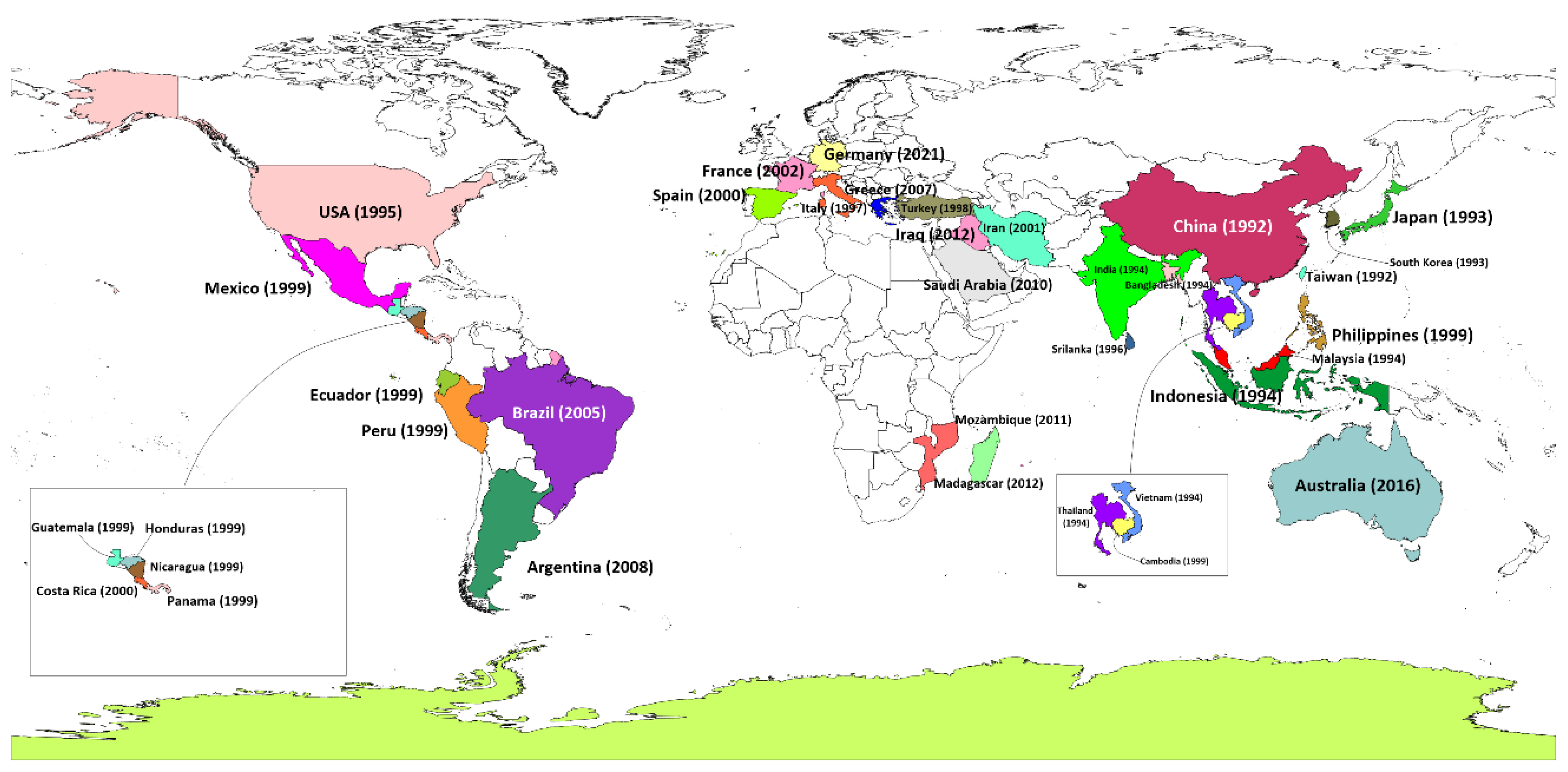

Shrimp aquaculture emerged as an international enterprise during the latter part of the 20th century, delivering nutrition- and protein-dense seafood to meet growing global market demand. With the boom of shrimp farming throughout much of Asia and beyond came a formidable foe: White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV), now one of the most virulent pathogens of shrimp in aquaculture. Since the emergence of WSSV in 1992, the global shrimp sector has suffered an estimated USD 8-15 billion in economic losses from this single disease (Verbruggen, Bickley et al. 2016, Panchal, Kumar et al. 2021). For the Asian shrimp industry a loss of about USD 20 billion due to WSD was possibly its worst experience (Davies 2016). The widespread presence of WSSV in global shrimp farms is a continuing nightmare for farmers. The virus can persist in pond sediments and surrounding areas for over 20 months, with studies detecting its presence in ponds soil for over ten months post-outbreak (Quang, Hoa et al. 2009). Notably, water serves as a critical medium for rapid viral dissemination; research has shown that WSSV DNA can be detected in water within six hours of disease onset in shrimp, with shedding intensifying until the host's death (Cox, De Swaef et al. 2023). Early reports of this disease from shrimp farms in China, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Ecuador and many countries that are among the largest producers of farmed shrimp in the world

(Figure 1). The speed with which the virus spread also reflected how quickly and across borders live shrimp and possibly contaminated water were traded in the globalized shrimp industry. By the early 2000s, WSSV had spread without control in shrimp aquaculture and epidemics appeared to be underway in almost all major shrimp-producing countries globally (Lotz and Soto 2002). While the devastating impacts of the virus were felt worldwide by shrimp farmers and aquaculture scientists, the virus continued to evolve infecting new species and gradually adapting to different environmental conditions. Over the years, WSSV advanced so rapidly – from farms in Bangladesh to shrimp ponds in Brazil – that the industry called for more sustainable farming practices paired with effective disease management (Hasan, Haque et al. 2020).

2. Integrated Review and Analytical Methods

This review presents a systematic effort in understanding the biology, pathology, and diagnostic methods as well as control measures associated with White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV), a globally-important pathogen of shrimp aquaculture. Data were synthesized according to a structured methodology adopted from various primary and secondary sources. A semi-structured search of relevant literature was conducted using the databases of Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar, focusing on peer-reviewed articles, government reports, and industry publications. Keywords used in the database search included variations and combinations of "WSSV diagnostics," "shrimp viral diseases," "aquaculture sustainability," and "viral transmission in crustaceans". After reviewing these primary sources, additional literature was identified by examining references cited in the initial studies, as well as through subsequent non-systematic searches on Google Scholar, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used to further transparency in the entire selection process. A total of 202 articles were found, and the final number of articles that were considered relevant for analysis was 108 after removal of duplicates and articles not relevant. These articles gave insights on the historical emergence and global distribution of WSSV and the biological mechanisms of its infection. To enhance the scope of the review, spatial and phylogenetic analyses were performed using secondary data. GPS coordinates of WSSV-infected zones were collected from government and non-government databases and visualized using ESRI’s ArcGIS software (version 10.8). Phylogenetic trees, depicting the genetic diversity of WSSV, were constructed using the VICTOR algorithm based on nucleotide sequence similarity data sourced from the NCBI database. Moreover, the review covers the economic and ecological impact assessments of WSSV outbreaks and these were conducted by compiling the global production statistics and analyzing co-infection reports with other pathogens. Such an integrative approach allowed the identification of patterns in WSSV spread and resilience mechanisms in shrimp.

3. History of White Spot Syndrome Virus

Shrimp is one of the most valuable species in global aquaculture, prized for its high levels of protein, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals (Sass 2022). The development of modern shrimp farming began in Japan, where Fujinaga pioneered semi-intensive shrimp farming techniques in the mid-20th century (Flegel 1997). His innovations, including advancements in shrimp spawning, larval rearing, and growth techniques, laid the groundwork for the expansion of shrimp farming to other countries such as Taiwan and the United States (Chamberlain 2010). As semi-intensive shrimp farming techniques were adopted globally, inputs such as feed, therapeutic agents, and overstocking were introduced without proper regulation, resulting in outbreaks of various diseases (e.g., white spot syndrome virus (WSSV), Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP), infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis (IHHNV), infectious myonecrosis virus (IMNV), yellow head virus (YHV), Taura syndrome virus (TSV), Macrobrachium rosenbergii nodavirus (MrNV), and acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND)) (Jithendran, Navaneeth Krishnan et al. 2021, Patil, Geetha et al. 2021). Among these, WSSV has caused the most devastating financial losses with mortality rates up to 100% within 7-10 days of infection (Talukder, Punom et al. 2021). WSSV was first reported in 1992 in cultured Penaeus japonicas in Taiwan and China (Chou Hy, Wang et al. 1995, Zhan, Wang et al. 1998), quickly spreading to Japan and Korea by 1993 where the disease was reported in farmed Peaeaus japonicas and Penaeus orientalis, respectively (Inouye, Miwa et al. 1994, Park, Lee et al. 1998). The rapidity with which WSSV spread across Asia caused massive devastation to the shrimp aquaculture industry, conservatively estimated at billions of dollars in losses, severely affecting the local economies of those countries. This single disease caused annual losses of over USD 500 million in China during its first prevalence due to reduced shrimp yields (Pereira Dantas Da Rocha Lima 2013). This outbreak seriously affected global supply of shrimp while China was one of the large shrimp producers at the time and continues to maintain its production pace. By 1994, the virus spread throughout Southeast Asia, affecting countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, India and Bangladesh (Flegel 1997, Shankar and Mohan 1998, Wang, Hassan et al. 1999, Sunarto, Widodo et al. 2004). During this period, Thailand was the world's largest shrimp producer, and it was estimated that outbreak caused losses of approximately USD 600 million within one year, crippling the aquaculture industry (Chanratchakool and Phillips 2002). In India, the virus caused annual economic losses exceeding USD 100 million due to a more than 80% reduction in shrimp exports (Kalaimani, Ravisankar et al. 2013). The spread of virus in Vietnam, resulted in annual losses of approximately USD 200 million, seriously damaging the nation's economy (Chanratchakool and Phillips 2002). Indonesia which ranked second globally as a shrimp-producing country by 2001, WSSV induced annual losses ranging between USD 300 million and USD 400 million (Evan and Putri 2021). In Bangladesh, the first major outbreak occurred in semi-intensive shrimp farms in Cox's Bazar in 1994, primarily affecting Penaeus monodon. The outbreak led to widespread devastation, with 90% of shrimp farms impacted, resulting in a 20% decrease in national shrimp production. A subsequent outbreak in 2001, driven by unplanned and uncontrolled expansion of shrimp farming, affected 25% of production (Debnath, Karim et al. 2014). Since 2007, the frequency of outbreaks in Bangladesh has increased, with WSSV remaining the leading cause of production loss (Hasan, Haque et al. 2020). The spread of WSSV was not confined to Asia. By 1995, the virus had reached the United States, likely introduced through frozen shrimp imports. The virus was detected in cultured shrimp in Texas and South Carolina in 1997 and 1998, respectively (Lightner, Redman et al. 1997). Subsequently, in 1999, major WSSV epizootics occurred in Ecuador, Panama, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Cambodia, Nicaragua and South Asian country Philippines, primarily affecting cultured P. monodon (Fe, Karlo et al. 2000, Rodríguez, Bayot et al. 2003, Galavíz-Silva, Molina-Garza et al. 2004, Chamberlain, Lightner et al. 2013). In Ecuador, a major shrimp exporting country in Latin America, losses were estimated at over USD 300 million annually during early 2000s (Stern and Sonnenholzner 2010). WSSV infections were causing losses of more than USD 300 million annually in Mexico during the early years of the outbreak, which prompted widespread adoption of biosecurity measures to reduce the impact of the virus (López-Téllez, Corbalá-Bermejo et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Recent outbreak of WSSV in different countries whole over the world (DISEASES-Cefas , 2022).

Table 1.

Recent outbreak of WSSV in different countries whole over the world (DISEASES-Cefas , 2022).

| Country |

Year |

Country |

Year |

| Mozambique |

2019 |

Ecuador |

2019 |

| China |

2019 |

Bangladesh |

2012 |

| India |

2018 |

Brunei Darussalam |

2013 |

| Indonesia |

2019 |

Colombia |

2005 |

| Japan |

2020 |

El Salvador |

2005 |

| Malaysia |

2009 |

Honduras |

2013 |

| Philippines |

2019 |

Hong Kong |

2013 |

| South Korea |

2019 |

Iran |

2013 |

| Taiwan |

2019 |

Madagascar |

2013 |

| Thailand |

2019 |

Myanmar (Burma) |

2012 |

| Vietnam |

2019 |

Nicaragua |

2013 |

| Costa Rica |

2019 |

Peru |

2013 |

| Mexico |

2019 |

Iran |

2011 |

| Panama |

2019 |

Saudi Arabia |

2012 |

| United States |

2020 |

Venezuela |

2011 |

| Australia |

2020 |

Argentina |

2010 |

| Brazil |

2019 |

|

|

By 2000, the virus had spread to Costa Rica, where it was first detected in Litopenaeus vannamei farms in the Gulf of Nicoya (Peña Navarro, Castro Vásquez et al. 2020). In the same period (between 1995 and 2001), the virus was detected in shrimp farms in several European Union (EU) countries including Greece, Italy, and Spain, and later in Turkey (Stentiford and Lightner 2011). In 2002, France reported its first WSSV outbreak, traced back to wild crustaceans (Rosenberry 2002, Stentiford and Lightner 2011). The Middle East was affected by WSSV, with the first outbreak in L. vannamei reported in the Khuzestan province of Iran in 2001 (Afsharnasab, Kakoolaki et al. 2014). Brazil recorded its first WSSV outbreak in L. vannamei farms in the Laguna province in 2005 (Cavalli, Romano et al. 2011), and by 2008, the virus was detected in Argentina (Martorelli, Overstreet et al. 2010). WSSV was reported in Saudi Arabia in 2010 and off the coast of Iraq in wild penaeids in 2012 (Tang, Navarro et al. 2012, Jassim and Al-Salim 2015). In Africa, the first detection of WSSV occurred at the Aquapesca shrimp farm in Quelimane, Mozambique, in 2011, with a subsequent outbreak in Madagascar in 2012 (Chamberlain, Lightner et al. 2013). Most recently, in November 2016, WSSV was identified in a prawn farm near Brisbane, Queensland, Australia (Knibb, Le et al. 2018).

4. Biology of WSSV

4.1. Taxonomy, Evolution and Protein Homology of WSSV with Other Taxa

WSSV was officially named in 2005 after multiple reclassifications (Fauquet, Mayo et al. 2005). It was earlier described under various names in literature, including hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis baculovirus (HHNBV) (Miao, Tong et al. 2000), rod-shaped nuclear virus of P. japonicus (RV-PJ) (Miao, Tong et al. 2000), Chinese baculovirus (CBV) (Nadala, Tapay et al. 1997), systemic ectodermal and mesodermal baculovirus (SEMBV) (Sahul Hameed, Anilkumar et al. 1998), penaeid rod-shaped DNA virus (PRDV) (Inouye, Yamano et al. 1996), and white spot baculovirus (WSBV) (Miao, Tong et al. 2000). Initially what is now WSSV was considered a non-occluded Baculovirus due to its cylindrical morphological characteristics and histological injuries observed at the onset of the virus (Wongteerasupaya, Vickers et al. 1995). However, it was found to differ genetically and ultrastructurally from them. It was later reclassified as the only member of the genus Whispovirus, in the family Nimaviridae by the International Committee of Taxonomy of Viruses on the basis of its thread-like polar extension – the distinguishing morphological feature of the family (Wang, Hirono et al. 2019).

WSSV taxonomy thus reflects not only its unique structure but also represents a distant phylogenetic relation to other large dsDNA viruses, which include members of families Baculoviridae, Ascoviridae, Asfarviridae, phycodnaviridae, and Iridoviridae (Wang, Hirono et al. 2019). WSSV presents a unique genomic organization, and shares a relatively small subset of conserved genes with the earlier aforementioned viral families, indicating a distant evolutionary relationship (

for details see supplementary Table 1). Thus, large-dsDNA viruses are characterized by comparative phylogenetic studies with genetic conservatism, particularly in genes involved in DNA replication and repair. These observations suggest that WSSV and other virus families may have diverged from other virus families and evolved over time into distinct genomic features. Evidence of this evolutionary linkage is further supported through detailed protein homology analysis, which reflects notable sequence alignments between WSSV proteins and those of other dsDNA viruses.

Table 2 of this article shows homologous relationships of WSSV proteins to those of several viral families. For example, wsv459 of WSSV shares full identity with a hypothetical protein from PBCV-1 (Phycodnaviridae), with an E-value of 3e-04. This strong conservation among those viral families suggests that this protein may have a very important role in the virus life cycle. On the other hand, wsv360 and wsv143 are homologous to proteins of Asfarviridae and Ascoviridae, showing identity values of 86% and 96%, with E-values of 0.008 and 0.022, respectively. The low values of the E-parameter indicate that the observed homologies are statistically significant and are not due to chance alignments of sequences. Probably the most significant information deduced from this is that conserved proteins, such as ribonucleotide reductase, exist across viral families, indicating shared molecular mechanisms crucial for viral replication (Sakowski, Munsell et al. 2014). Apart from ribonucleotide reductase, other WSSV proteins homologous to those from various viral families like Poxviridae, Mimiviridae, and Baculoviridae are listed in

Table 2. For instance, wsv486 shares 90% identity with the variola B22R protein from FWPV (Poxviridae) with an E-value of 0.041, suggesting functional relatedness between these proteins. These conserved proteins may play roles in vital viral functions like DNA replication, immune evasion, and virion assembly (Sánchez-Paz 2010). The existence of such proteins in different viral families could be the result of evolutionary convergence in which homologous genes have been retained across different lineages due to similar functional imperatives (Wang, Li et al. 2020).

The presence of conserved proteins between WSSV and other large dsDNA viruses bears very strong implications for the understanding the evolutionary history of WSSV. WSSV also shares several essential genes with viruses infecting different hosts, such as plants and vertebrates, would implies that these are maintained through evolutionary pressures due to their functionality. This information enhances our understanding of how WSSV may have adapted to its crustacean hosts and developed its pathogenic capabilities. Moreover, the conservation of viral proteins across families has practical applications in the development of anti-viral strategies.

4.2. Global Genetic Distribution of WSSV (Genome)

The VICTOR program has produced the following neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree (

Figure 2), which illustrates evolutionary relationships between WSSV isolates from a broad geographical range. The tree is rooted by midpoint rooting and displays genetic diversity among the WSSV isolates based on nucleotide sequence similarity. This tree contains high (~100%) bootstrap values for most of the branches, providing very high confidence in clustering, particularly between the more closely related isolates. The isolates from China (NC 075105.1) and Bangladesh (PP134839.1, PP134840.1, PP134841.1) were grouped in one clade, which was strongly supported by a bootstrap value of 100, suggesting an extremely recent common ancestor or a closely related evolutionary origin. Indian isolates, EU327500, EU327499, and Thai, KX501222.1, KX501223.1, were phylogenetically tight, indicating regional phylogeographic patterns. This is further reflected in the presence of distant isolates, such as those from Mexico (MG432477.1) and Germany (KF981443.1), outside of primary clusters, indicating significant genetic divergence that might relate to geographical and environmental differences influencing WSSV evolution. Isolates from Saudi Arabia (KF976716.1) and Brazil (HQ130032.1) occupy an intermediate position, with a likely migration or trade-related virus spread. Another distinction involves the groupings from South Korea (GQ328029.1) and Australia (MF161441.1), which, further downstream, split into two lineages diverging from the other Asian core isolates. The branch lengths within the tree themselves are indicative of the mutation rates across the given isolates; some have longer branches, such as Germany and Brazil, indicating higher rates of evolution or separate mutational events.

4.3. Transmission Dynamics of WSSV

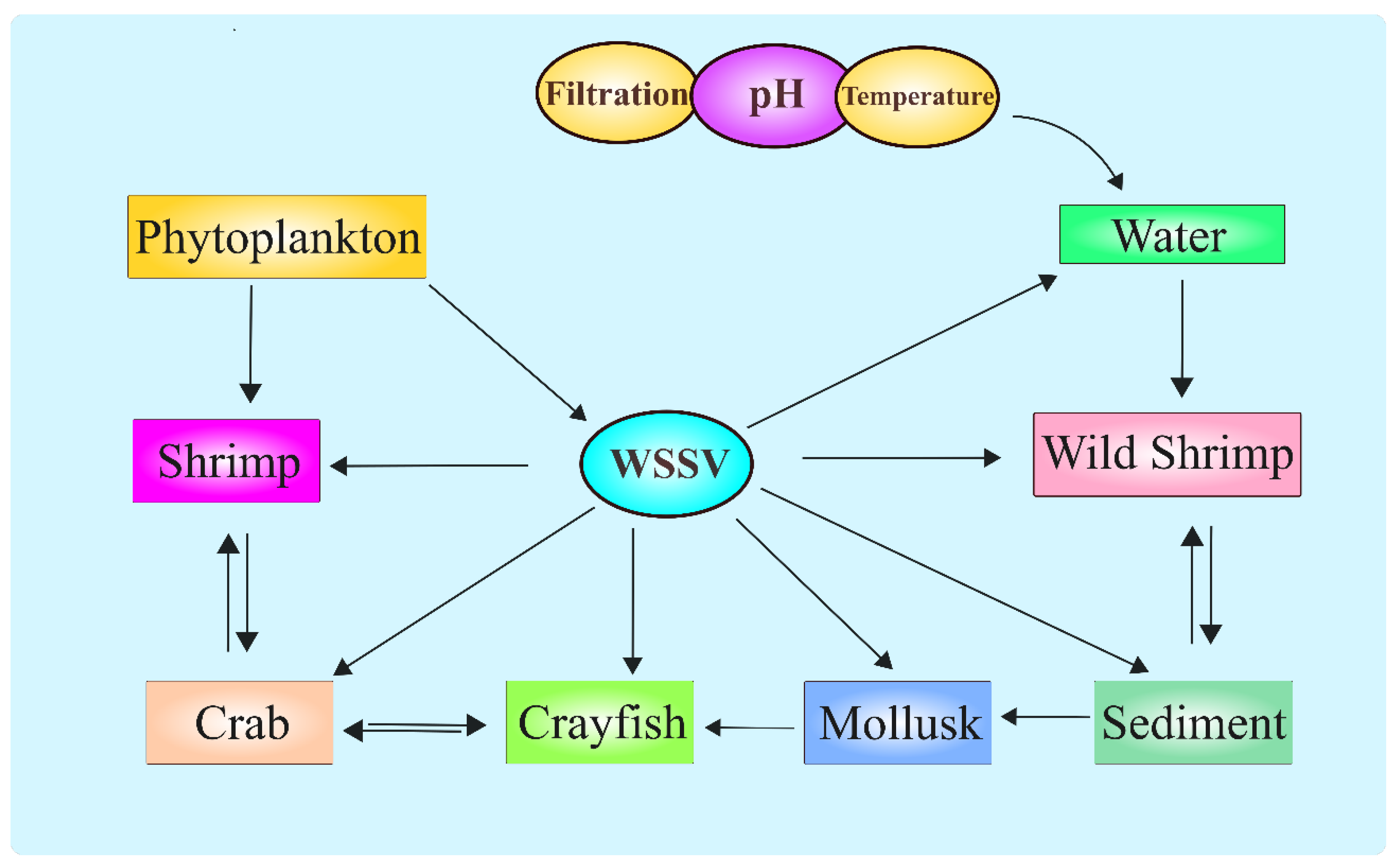

The WSSV is the most virulent pathogen affecting global shrimp aquaculture, and unraveling its dynamics of transmission is crucial for effective mitigation strategies. WSSV is a highly contagious, lethal, double-stranded DNA virus of the Nimaviridae family that often causes large scale mortalities (Oakey, Smith et al. 2019). It has vertical and horizontal routes of transmission, both contributing to the rapid spread of the disease in different shrimp farms and even in nature. Horizontal transmission is the more common mode of transmission; this includes direct contamination through waterborne contact, infected shrimp, and organic materials such as feces and molts (Tuyen, Verreth et al. 2014, Kim, Kim et al. 2023). Waterborne transmission is most important because infected shrimp release viral particles into the water through gill shedding, from body surfaces, or during decomposition, hence producing a heavily contaminated milieu. It has been observed that even an extremely low level of virus-contaminated water may mediate the spread of WSSV, and viral shedding can be detectable within hours of infection onset (Kim, Kim et al. 2023). This environmental transmission is a serious concern in densely populated shrimp farming systems where high stocking densities enhance the risk of infection. In infected shrimp, WSSV advances with rapid and lethal progression.

Significantly, it has been found that compared to the important transmission route of cannibalism or ingestion of infected tissues, waterborne exposure poses a greater infection risk in high-density farming (Pradeep, Rai et al. 2012, Verbruggen, Bickley et al. 2016). Clearly, this makes the design of biosecurity protocols very relevant; it implies that control over water quality and reduction of waterborne exposures should be emphasized above preventing cannibalism. On the other hand, vertical transmission becomes evident when the virus-carrying broodstock is used to transmit the virus to progeny through spawning (Vijayan, Anand et al. 2024). This has been considered a very injurious route of infection in hatcheries since asymptomatic carriers can spread the virus unknowingly to those populations.

WSSV does not exclusively affect shrimp, but can affect a wide variety of crustacean and non-crustacean species as carriers and vectors both in aquaculture and the wild (Peng, Lo et al. 1998, Otta, Shubha et al. 1999, Hossain, Chakraborty et al. 2001, Joseph, James et al. 2015). For instance, WSSV was isolated from crabs (Pratapa, Kumar et al. 2023), crayfish (Lee, Kim et al. 2021), and other decapods (Wang, Lo et al. 1998) (

Figure 3), broadening the circle of potential inter-species infection and increasing the degree of difficulty in containment measures. These findings further stress the generalist nature of WSSV, able to thrive under varying conditions of brackish and freshwater systems. Such adaptability carries further control complications, especially in open systems where farmed and wild populations interact. Probably one of the main stumbling blocks in interpreting the transmission routes of WSSV is the variation in impact due to different environmental factors like temperature, salinity, and pH (Van Thuong, Van Tuan et al. 2016). Studies have demonstrated that the rate of virus replication as well as the speed of diffusion are higher at elevated temperatures, while variation in salinity can lead to differences in susceptibility among shrimp to the virus (Millard, Ellis et al. 2021). For example, in tropical regions, where temperatures are consistently high, WSSV outbreaks are more serious with rapid disease development and higher mortalities. Moreover, the virus appears to be stable within a broad range of salinity levels, which allows it to infect shrimp in both marine and freshwater aquaculture.

However, despite advances in understanding WSSV transmission dynamics, substantial knowledge gaps still remain, particularly relating to the role of non-crustacean species and environmental reservoirs in the perpetuation of the virus. Further, the presence of wild species that could be carriers or reservoirs of WSSV complicates efforts to establish WSSV-free zones in aquaculture. Additionally, the persistence of the virus in the environment, even in the absence of host species, raises concerns about the long-term sustainability of shrimp farming in such locations (Quang, Hoa et al. 2009). One proposed solution has been compartmentalization farming, a concept where shrimp are reared in biosecure units, inhibiting the spread of pathogens at both farm and external environment levels (Tidbury, Ryder et al. 2020). These techniques have achieved limited success, and the high cost of retrofitting has precluded widespread adoption. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise mechanisms of WSSV transmission in mixed-species environments, as well as developing novel strategies for disease prevention and control. With such diverse routes of virus transmission, further investigation into the host range, whether through natural or experimental infection, together with interaction of host proteins with the virus during replication and dissemination, will clarify the complex epidemiology of WSSV.

4.4. Host Species Reported to Be Naturally or Experimentally with WSSV

A wide range of host including economically important different shrimp species and organisms from both fresh and marine environment have been found to be infected with viral pathogens. For WSSV, hosts in a wide array of shrimp species have been detected from

Penaeus monodon (Wang, Hassan et al. 1999),

Penaeus vannamei (Jang, Qiao et al. 2014),

Marsupenaeus japonicus (Zhang, Koiwai et al. 2018), and

Penaeus chinensis (Yang, Zhang et al. 2008). In addition to these economically valuable penaeid species, WSSV has been isolated from crabs (

Scylla olivacea,

Neohelice granulate) (Pratapa, Kumar et al. 2023), copepods (Chang, Chen et al. 2011), lobsters (Rajendran, Vijayan et al. 1999), crayfish i.e.,

Procambarus clarkii (Huang, He et al. 2022), and freshwater species such as

Macrobrachium rosenbergii (Peng, Lo et al. 1998). Furthermore, it was confirmed that WSSV primarily afflicts decapod crustaceans, but recent studies demonstrate that its host range is further expanding. A study by Desrina

et al. emphasized that WSSV infects species from more than 50 families, including non-crustacean hosts such as mollusks, though crustaceans remain the primary hosts (Desrina, Prayitno et al. 2022). In experimental conditions, the transmission and replication of WSSV have been confirmed in non-target species like

Metapenaeus ensis (Chang, Peng et al. 2004),

Exopalaemon orientalis, and

Calappa lophos (Pradeep, Rai et al. 2012), where non-target species might act as reservoirs or vectors (for more details see

Table 3). The wide host range of WSSV, comprising different species of shrimps and other crustaceans, partly due to the ability of WSSV to bind a wide variety of host proteins that are conserved or functionally similar across hosts.

4.5. WSSV Virion Proteins

The WSSV virion is an extremely infective particle and thus very important in the process of disease transmission (Sánchez-Paz 2010). Structurally, this virion is a rod-shaped enveloped, non-occluded particle composed of macromolecules arranged to protect and convey the viral genome to effect infection in host organisms. The width of the WSSV virion ranges from 70 to 170 nm, while the length falls between 210 and 420 nm. The virion is composed of three layers: the tegument layer, the envelope, and the nucleocapsid (300 by 70 nm and enveloped by a layer of capsids) (Wang, Hirono et al. 2019). Each of these layers plays a role in the integrity and infectivity of the virus. WSSV has at least 58 structural proteins, of which localization data is available for 48 (Li, Lin et al. 2007). Among these, 33 are envelope proteins, nine are nucleocapsid proteins, and five are tegument proteins (Wang, Hirono et al. 2019). Of these envelope proteins, the major ones are VP28 and VP26 proteins, making up about 60% of the envelope proteins. The envelope proteins play an important part in WSSV's infectivity by means of binding. VP28 is a well-known protein that handles cell surface recognition as a receptor for the virus to attach to the host cell membrane (van Hulten, Witteveldt et al. 2001, Tsai, Wang et al. 2004, Yi, Wang et al. 2004). This mechanism of binding is critical for successful infection in shrimp because it allows the virus to pass into the cytoplasm of the host cell. Thus, VP28 may be considered a prime target for antiviral treatment because inhibiting this protein is normally adequate to block the virus from attaching to or entering host cells.

Besides VP28, other envelope proteins VP31, VP33, VP36A, VP110, VP136A and VP664 contain cell attachment motifs that may facilitate the initial stage of viral infection (Tsai, Wang et al. 2004, Leu, Tsai et al. 2005, Xie, Xu et al. 2006). These motifs allow the virus to attach to the host cell surface, making them an important feature for the development of therapeutic strategies. Among them, VP664 is one of the most abundant and largest proteins, comprising 6,077 amino acids, and plays a very important role in viral replication. Interfering with the functioning of VP664 might disturb replication of the virus and potentially offer another avenue for pharmaceutical intervention. A more detailed breakdown of the structural proteins (VP28, VP39B, VP31A, VP41B, VP51A, VP51B, VP68, VP124, VP150, VP187, VP281, and VP292) found in the WSSV envelope (Li, Lin et al. 2007) and other proteins (VP190, VP466, VP15, VP51, and VP76) derived from a collagen-like protein in the nucleocapsid of WSSV (Li, Chen et al. 2004) are listed in Table 2 according to their respective locations in the virion: envelope, tegument, or nucleocapsid. For instance, proteins such as VP124, VP187, and VP466, their kDa and ORF values reflect their capability to enhance the WSSV virion’s invasiveness into host cells; thus, further understanding of their structure and function could eventually facilitate targeted treatments (Xie, Xu et al. 2006).

Information integrated in Table 2 on WSSV proteins provides further potential targets that could be used in drug development. For instance, proteins such as VP26 and VP28 have roles in maintaining the structural integrity of the virion and are also involved in a series of steps which result in infection (Valdez, Yepiz-Plascencia et al. 2014, Taengchaiyaphum, Nakayama et al. 2017). Small molecules or peptides could be designed to interfere with the structural roles of these proteins, preventing proper virion assembly or entry into host cells (Chang, Liu et al. 2008). These can be targeted therapeutically by devising means through which the functions of these proteins are disrupted to inhibit the virus from spreading. Another idea that might be significant is that proteins with glutathione S-transferase fusion, like ORF151-VP466, can be targets that allow improvements in the host immune response, or inhibit viral processes (Ha, Soo-Jung et al. 2008). Indeed, these key identifications allow the possibility of developing vaccines or antiviral medications targeting the virus life cycle at points intended to interfere with infecting and replicating within shrimp, thereby reducing aquaculture losses attributed to WSSV.

4.6. Molecular Mechanisms of WSSV Life Cycle: Host Protein Contributions

The molecular underpinning of the life cycle mechanisms involves an elaborate interplay between viral components and host cell machinery. Interactions of host proteins with viral proteins at many steps in the infection process are indeed critical to the successful replication and spread of the virus through the host organism. These proteins facilitate not only the entry of the virus into the host cell but also contribute to intracellular trafficking, viral replication, assembly, and egress. Here, we have focused on the participation of host proteins in each critical stage of the WSSV life cycle from viral entry to progeny virion release.

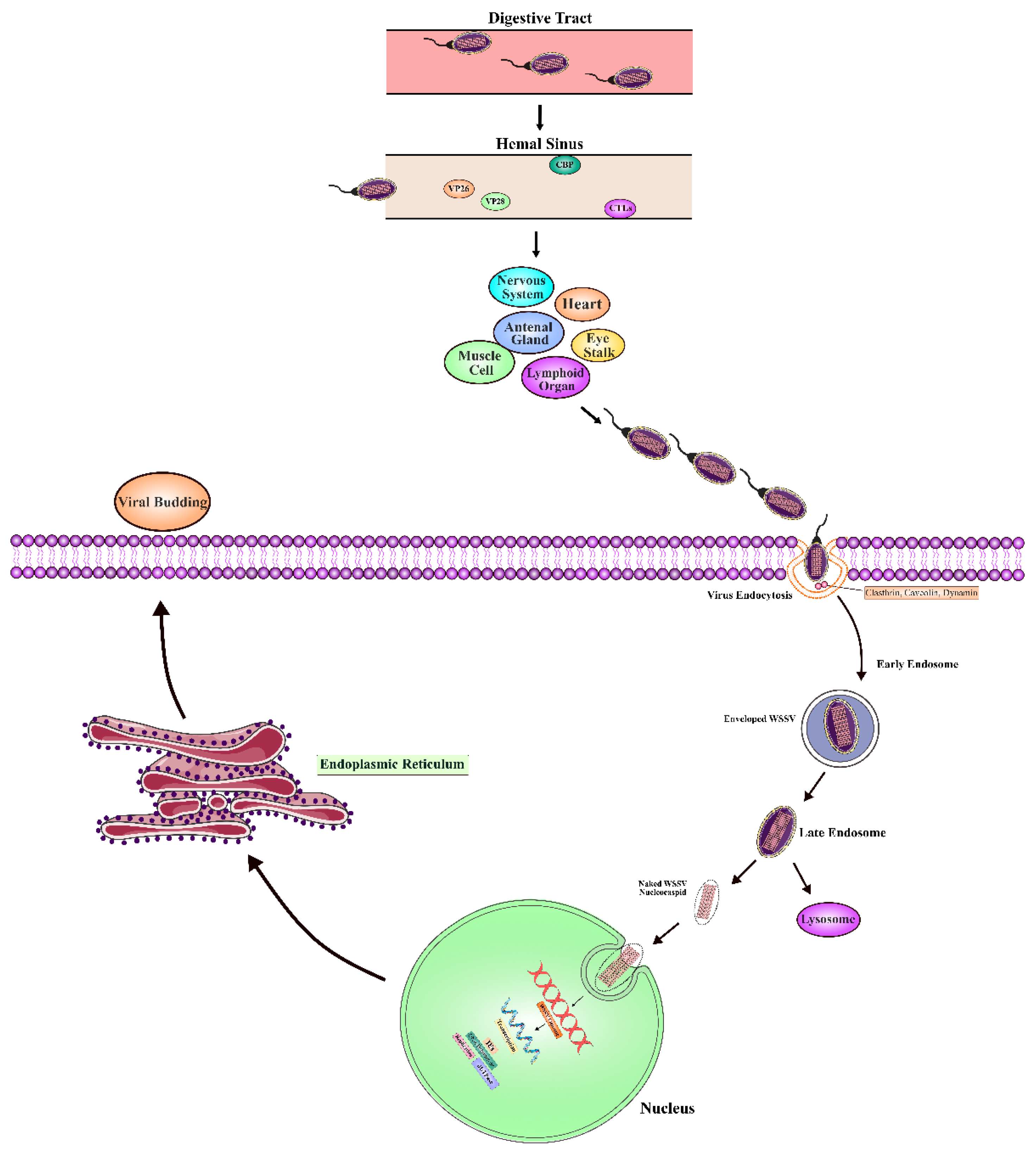

Entry of viruses into host cells: The process of infection is initiated when WSSV virions come in contact with host cells through the ingestion of infected or dead shrimp. Infection is mainly via the digestive tract, where the viral particles come into contact with and attach to the receptors of the host cells lining the epithelium (

Figure 4). These interactions are mediated by host proteins serving as receptors/co-receptors for the virus, which allow viral attachment to the surface of the cell. In this regard, one of the most studied receptor families involves the CBPs, more specifically the PmCBP in

Penaeus monodon, which is a critical participant in mediating WSSV attachment. Hence, this protein is capable of binding at least 11 envelope proteins of WSSV and establishes a stable interaction through which the virus can initiate entry into the host cell, such as VP24, VP32, VP39B, VP41A, VP51B, VP53A, and VP110 (Huang, Leu et al. 2014). Moreover, PTs play a vital role in the gut as receptors, especially in

L. vannamei, where LvPT interacts with viral proteins like VP32, VP38A, and VP39B (Verma, Gupta et al. 2017). These proteins are secreted into the stomach, possess potent chitin binding properties, and help in the transportation of viral particles across the epithelium of the digestive tract. Bound to these receptors, the WSSV particles penetrate the epithelial cells, cross over the basal membrane, and enter further into the circulatory system. Another major molecule that plays an important role in viral entry includes the glucose transporter 1 (Glut1) protein, expressed in almost all tissues, including the digestive tract, muscles, and pleopods. Glut1 plays a complementary role in identifying several envelope proteins of WSSV, such as VP28 and VP53A, during viral entry into cells (Huang, Chan et al. 2015). This protein binds to at least seven viral envelope proteins in an adjoining loop region, making it a key mediator of WSSV infection. More recent studies have proposed a complex of Glut1 forming with PmCBP, presenting a larger surface area to the virus by making viral binding and, therefore, attachment and internalization more effective (Encinas-García, Mendoza-Cano et al. 2023).

Endocytosis and intracellular trafficking: Attached to the host cell, the main mode of WSSV entry into the cell is through receptor-mediated endocytosis. This allows the virus to bypass the host cell membrane into the intracellular environment. So far, the best-characterized pathway of endocytosis exploited by WSSV is clathrin-mediated endocytosis, where the virus is engulfed into clathrin-coated vesicles that bud off from the plasma membrane (Pavelka and Roth 2010). These vesicles ferry the virus to early endosomes, in which the low pH allows viral uncoating to occur. This acidic environment is essential for initiating conformational changes in the virus, leading to the release of the viral genome and nucleocapsid into the host cytoplasm (Villanueva, Rouillé et al. 2005). Also, endocytosis depends on cholesterol and dynamin, evidenced by studies showing that WSSV invasion depends on these lipid components for membrane curvature and vesicle scission (Chen, Shen et al. 2016). The virus avoids lysosomal degradation via Rab GTPases, which regulate membrane trafficking events during endocytosis. Specifically, Rab5, during development in P. monodon and L. vannamei, mediates the maturation of early endosomes into late endosomes. Rab7 is involved in the later stages of endosome maturation and replaces Rab5, ensuring transport of viral nucleocapsid to the host cell nucleus without degradation (Attasart, Kaewkhaw et al. 2009).

Viral genome delivery and replication: Once inside the host's cytoplasm, the viral nucleocapsid has to reach the nucleus, where replication occurs. The viral envelope fuses with the host endosomal membrane and discharges the nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm, which then migrates to the nucleus. The nuclear pore complexes transport the viral genome into the nucleus. This marks the start of the replication phase. Inside the nucleus, WSSV expresses its immediate early genes, which are considered crucial for initiating the replication machinery. These early genes allow for the synthesis of mRNA, which is transported back to the cytoplasm for translation. The viral mRNA then undergoes translation in the cytoplasm by free ribosomes, encoding a major structural protein, VP664, which forms the backbone of the WSSV capsid. This occurs in parallel with the replication of the viral genome and the synthesis of viral proteins, enabling the assembly of new viral particles (Leu, Tsai et al. 2005). The involvement of host proteins continues to play a critical role in these processes. For instance, glucose transporter 1 (Glut1) mediates the trafficking of viral proteins between cellular compartments, while the tetraspanins like FcTetraspanin-3 bridge the connection between the inner and outer cell membranes to help mediate the intracellular locomotion of viral components (Wang, Li et al. 2010, Gui, Wang et al. 2012).

Viral assembly and egress: Assembly of the virus occurs near the host nucleus, where the major capsid proteins, including VP664, form the new structure of virions. These assembled virions incorporate viral envelope proteins like VP28, synthesized in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. These envelope proteins are then targeted to the inner nuclear membrane, where they associate with the assembling virions. VP28 is an essential protein for infection efficiency and has been shown to stabilize the viral envelope and increase the infectivity of the virions (van Hulten, Westenberg et al. 2000). As the viral load within the host cell increases, it builds up until the accumulation of viral particles overwhelms the cell. Finally, lysis of the host cell releases newly formed virions into the extracellular environment. Completion of the WSSV life cycle enables the virus to infect neighboring cells and to spread throughout the host organism. The lysis of infected cells is a pivotal event that permits the rapid propagation underlying the systemic infection that is typical of WSSV.

Systemic spread and organ targeting: Once internalized into the hemolymph, the virus is circulated via the open vascular system of the host to infect a wide array of tissues and organs of mesodermal and ectodermal origin. Integrin proteins on the surface of target cells, including those of the gonads, heart, muscles, and nervous system, constitute important docking points for WSSV. Integrins in L. vannamei bind viral proteins VP26, VP31, VP37, VP90, and VP136, thereby facilitating virus attachment and penetration of these vital tissues (Verma, Gupta et al. 2017). There exist specific viral motifs, such as RGD, YGL, and LDV, which enable the virus to recognize and bind integrins on the host cell surface through such interactions. The virus can either penetrate directly into the host cell membrane once bound to the integrins or be internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis. WSSV research has shown that both clathrin-mediated and caveolae-mediated pathways are used for endocytosis depending on the host cell and tissue type (Leu, Tsai et al. 2005). Caveolae-mediated endocytosis is particularly cholesterol-dependent, and it promotes internalization within vesicles, thus bypassing lysosomal degradation of viral particles. The systemic spread of WSSV within the host is further facilitated by C-type lectins that bind viral proteins and facilitate the transportation of the virus through the circulatory system (Wang, Xu et al. 2009). In L. vannamei, LvCTL1 binds to viral proteins VP14, VP24, VP28, and VP95 and helps distribute them in the body via the hemolymph. These interactions initiate a systemic infection, with the virus targeting multiple organs and tissues, including hemal sinuses, gonads, and eyestalk (Zhao, Yin et al. 2009).

Host defense evasion mechanisms: WSSV expresses several mechanisms that enable the pathogen to evade host immune responses to establish a productive infection. This includes manipulation of host endosomal trafficking pathways to avoid degradation by lysosomes, in which the Rab GTPases, notably Rab5 and Rab7, play important roles (Verbruggen, Bickley et al. 2016). Rab5 controls endosomal maturation, thereby facilitating transport of viral nucleocapsids from early to late endosomes. Rab7 ensures that the viral particles are not targeted to lysosomes for degradation (Attasart, Kaewkhaw et al. 2009). In this way, the virus evades host immune responses and possibly persists in a latent state for longer periods. WSSV also manipulates immunomodulation within its host by interacting with immune-related proteins, such as tetraspanins and lectins, which act as receptors with important implications in immune signaling. The virus, through binding, may alter the immune response and inhibit processes leading to the production of antiviral mechanisms, thereby enhancing its survival and replication within the host.

5. Pathology

5.1. Gross Sign of WSSV

Gross clinical signs in animals infected with WSSV vary considerably at different stages of the infection process, however, white spots on the cuticle are pathognomonic signs for this viral disease in some shrimp species. These appear as white spots, 1-3 mm in diameter, and are calcium-rich viral accumulations on the exoskeleton especially on the cephalothorax, appendages, and abdomen (Sánchez-Paz 2010). However, white spots do not occur in all WSSV infections, and identical lesions due to non-viral etiology such as bacterial infection or shell mineralization disease are also possible, thereby making them an unsatisfactory single diagnostic feature. In species such as the Penaeus monodon, Penaeus vannamei, and Marsupenaeus japonicus, infected individuals in general become lethargic, exhibiting decreased feeding and erratic swimming before eventually succumbing to the disease (Walker and Mohan 2009). Infected shrimp usually move to the edge of the ponds or to the water surface, where they are preyed upon by predatory birds that can facilitate mechanical transmission of the virus (DAWR 2017). Characteristic symptoms of infection include soft shells, discoloration of the body to reddish, and loose appendages in worst cases. Similar signs are shown by Penaeus chinensis, with additional symptoms of soft bodies and gill necrosis (Rajendran, Vijayan et al. 1999). The signs of WSSV infection in Macrobrachium rosenbergii (giant freshwater prawn) include red bodies, gill necrosis, and lethargy (Sahul Hameed and Bonami 2012). Experimental studies have shown that infected shrimp can begin shedding viral DNA into the water within six hours of infection, with shedding peaking just before death. This greatly elevates the risk of infection to surrounding shrimp, particularly in closed systems like grow-out ponds (Arbon, Andrade Martinez et al. 2024, Cox, De Swaef et al. 2024, Kim, Shin et al. 2025). Other susceptible decapod crustaceans, like Metapenaeus ensis and Exopalaemon orientalis, also exhibit similar clinical manifestations of incapacitated mobility, reddening of the body, and lesions in the exoskeleton. WSSV is histologically characterised as an ectodermal and mesodermal tissue-attacking virus. Very severe degenerations are shown among infected gills, lymphoid organs, and antennal glands (Pradeep, Rai et al. 2012). WSSV infection in Scylla olivacea and Neohelice granulata causes lethargy, white spots on the carapace, and internal tissue necrosis (Moser and Marques 2023). The same type of white spots develops on lobsters and crayfish (Procambarus clarkia), infected with WSSV, along with erratic swimming, often accompanied by discolored or darkened exoskeletons (Jiang, Xiao et al. 2017). Even copepods and mollusks, which are less infected, may act as passive carrier or mechanical vectors of WSSV, especially after being exposed to high viral loads from contaminated environments (Chang, Chen et al. 2011). Although such organisms may occasionally harbor viral particles, the current evidence does not show that they allow productive viral replication, and therefore function primarily to propagate transmission but not disease expression (Matozzo, Ercolini et al. 2018). WSSV exerts its pathogenicity towards host species by virtue of tissue tropism for vital tissues such as cuticle and haemopoietic systems, inducing degeneration and death. Poor water quality may act as an environmental stressor that enhances disease progression through increased susceptibility and more rapid viral replication. In addition, certain factors such as rising or fluctuating temperature, salinity imbalance, and high stocking density are also found to impair the immune response of the shrimp, contributing to the progression and severity of WSSV outbreaks (Millard, Ellis et al. 2021). Behavioral changes, including convulsions and reduced mobility, can be observed in the late stages of infection, often in severely diseased populations.

Table 4.

Gross clinical signs of WSSV in various species.

Table 4.

Gross clinical signs of WSSV in various species.

| Species |

Clinical sign observed |

Reference |

| Penaeus monodon |

White spots, lethargy, soft shell, erratic swimming, reddish body |

(Walker and Mohan 2009) |

| Penaeus vannamei |

White patches, gill necrosis, soft cuticle, lethargy |

| Marsupenaeus japonicus |

White spots, disorientation, loose appendages, lethargy |

| Penaeus chinensis |

Soft body, white spots, gill necrosis, lethargy |

(Rajendran, Vijayan et al. 1999) |

| Scylla olivacea |

White spots on carapace, necrosis, lethargy |

(Moser and Marques 2023) |

| Neohelice granulata |

White spots, lethargy, body discoloration |

| Procambarus clarkii |

White spots, abnormal swimming, lethargy |

(Jiang, Xiao et al. 2017) |

| Macrobrachium rosenbergii |

Red body, gill necrosis, lethargy |

(Sahul Hameed and Bonami 2012) |

| Metapenaeus ensis |

Lethargy, body redness, white spots |

(Pradeep, Rai et al. 2012) |

| Exopalaemon orientalis |

White spots, soft exoskeleton, decreased mobility |

| Calappa lophos |

Lethargy, body discoloration, white spots |

5.2. Histopathology of WSSV

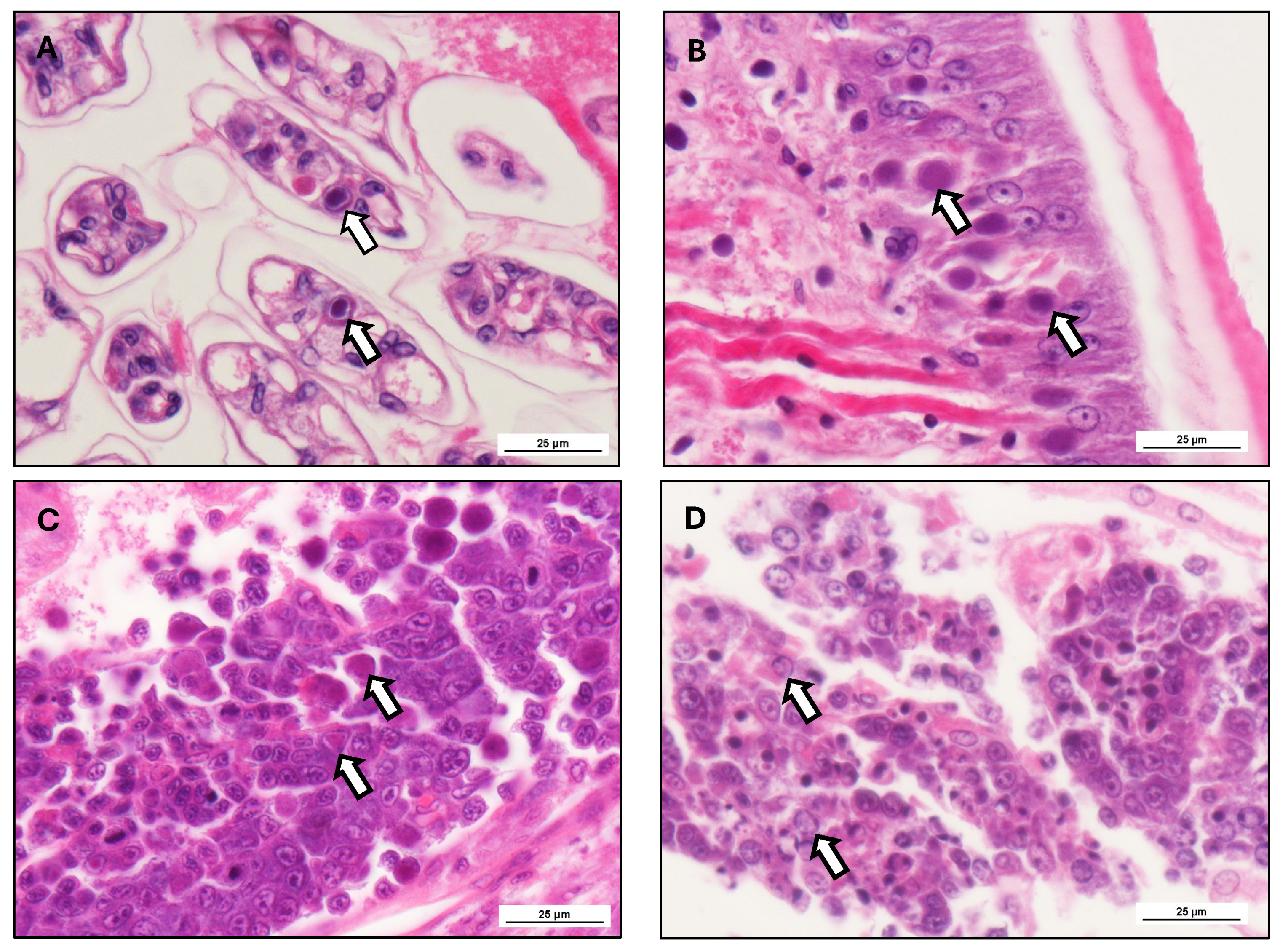

The histopathological changes of WSSV reflect the pathogenesis, disease course, and immunity associated with WSSV (

Figure 5). The main target cells of WSSV are the ectodermal and mesodermal tissues (Tang, Pantoja et al. 2013), including the cuticular epithelium, gills, lymphoid organ, foregut. In the hepatopancreas, WSSV infection has been observed predominantly in the haemocytes and connective tissues surrounding the tubules, but not in tubular epithelial cells themselves (Islam, Mou et al. 2023). The representation of WSSV infection features hypertrophied nuclei with intranuclear inclusion bodies of a basophilic nature, pyknosis, karyorrhexis, and cytoplasmic vacuolization (Rodríguez, Bayot et al. 2003). As infection progresses, these cellular changes result in widespread necrosis with attendant impaired physiologic function of infected organs (organ specific information available in

Table 5). Gill tissues exhibit epithelial sloughing and lamellar fusion, severely reducing respiratory efficiency, and the hepatopancreas, a principal organ of shrimp metabolism, degenerates, often complicated by secondary bacterial infections (Rajendran, Vijayan et al. 2005). The lymphoid organ plays a critical role in immunity as well, but in WSSV-infected shrimp, it undergoes lymphoid organ spheroid (LOS) formation, which is an attempt to limit viral replication but is unsuccessful because viral replication happens so rapidly (Sweet and Bateman 2016). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) has revealed that WSSV virions are rod-like, approximately 275 nm in length and 120 nm in diameter (van Hulten, Westenberg et al. 2000), enveloped with a double-stranded DNA genome in a lipid envelope. Virus replication occurs in the nuclei of infected epithelial cells (Ng, Cheng et al. 2023). Compared to other viruses of shrimp such as Infectious Hypodermal and Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus and Taura Syndrome Virus, which essentially infect haemocytes, WSSV has a tropism for epithelial tissues that significantly aggravates systemic infections (Sánchez-Paz 2010). The progression of WSSV infection is inconsistent, taking either acute or chronic forms. From histopathological observation it also has been ascertained that massive tissue necrosis, intense virus replication, and extensive intranuclear inclusions happen in acute WSSV infections (Yin, Yan et al. 2023), resulting in explosive mortality of shrimp. In contrast, chronic infections consist of persistent, low-grade viral replication, with localized tissue damage and immune suppression, resulting in growth impairment and increased susceptibility to secondary infections.

Histopathological grading is also an important technique for ascertaining WSSV severity and evaluating the extent of disease progression. The intensity of infection is classified into four grades: G0 (no infection), G1 (mild infection with nuclear hypertrophy in fewer than 10% of cells), G2 (moderate infection with inclusion bodies in 30-50% of infected cells and mild necrosis), G3 (severe infection with inclusion bodies in more than 50% of cells, together with extensive necrosis), and G4 (late infection with complete cell destruction in multiple organs) (Gholamhoseini, Afsharnasab et al. 2013, Kim, Kim et al. 2023). Molecular diagnostic techniques such as in situ hybridization (ISH) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) significantly enhance the sensitivity of WSSV detection. Parallel to ISH, normal histology and electron microscopy permit precise localization of viral DNA in infected tissues, which usually reveals strong signals in connective tissue, gill lamellae, and reproductive organs, suggesting potential vertical transmission (Sánchez-Martínez, Aguirre-Guzmán et al. 2007, Pradeep, Rai et al. 2012). Histopathology remains a vital diagnostic tool for early detection of the disease, enforcement of biosecurity, and treatment evaluation. Preventive strategies such as probiotics, immunostimulants, and plant extracts have shown promise in reducing histopathological damage and improving survival rates in shrimp (Hoseinifar, Sun et al. 2018). Additionally, histological examination is employed to examine the efficacy of antiviral drugs in managing WSSV caused tissue pathology (Nilsen, Karlsen et al. 2017). The combination of histopathology and molecular diagnosis is more effective at disease detection and control. It is noteworthy that histopathological lesion provides a presumptive diagnosis of WSSV. In accordance with the World Organisation for Animal Health diagnostic manual, confirmatory diagnosis is required to be carried out with PCR and better sequencing to ascertain the presence of WSSV-specific genomic material, which is very much essential for accurate reporting and disease surveillance in accordance with international standards.

5.3. Co-Infection of WSSV and Other Disease of Shrimp

Prevalence of disease pattern in shrimp farms has shifted from previous simple infection to co-infection including complicated infections, mixed infections, super infections, polymicrobial diseases, secondary infections, multiple infections, dual infections, and concurrent infections of homologous or heterologous pathogens in recent years (Dai, Yu et al. 2018, Kooloth Valappil, Stentiford et al. 2021, Lee, Jeon et al. 2023). Simultaneous or sequential co-exposure of heterologous pathogen (parasite-bacteria, parasite-virus, virus-bacteria, fungus-bacteria) also termed as co-infection what further defined as the infection of host animal (shrimp) from two or more genetically distinct pathogens, each of which has pathogenic effects and harms the host in concert with other infections. Among different pattern of pathogens exposure to shrimp species (for details see

Table 6), homologous combinations of viruses (WSSV, Taura syndrome virus (TSV), hepatopancreatic parvovirus and infectious myonecrosis virus (IMNV), infectious hypodermal and haematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV), monodon baculovirus (MBV)) (Cavalli et al., 2013; Chayaburakul et al., 2004; Dewangan et al., 2017; Feijó et al., 2013; Flegel et al., 2004; Manivannan et al., 2002; Otta et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2009; Teixeira-Lopes et al., 2011; Thamizhvanan et al., 2019) and bacteria (

Bacillus cereus,

Bacillus flexus,

Shewanella decolorationis,

Aeromonas veronii, Shewanella amazonensis and

Kurthia gibsonii) (Dewangan et al., 2022) are most extensively investigated.

For shrimp species parasite-virus co-infections are relatively uncommon and were first reported involving a microsporidian parasite (Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei) and viral pathogens (Taura syndrome virus (Tang et al., 2017) and infectious myonecrosis virus (Jithendran et al., 2021)). It is now increasingly evident that EHP has become a substantial global threat to shrimp aquaculture with the economic loss from this microsporidian being approximately double that of WSSV for Indian shrimp industry in 2021 (Patil et al., 2021). Moreover, co-infection of EHP and WSSV (Thamizhvanan et al., 2019) from synergistic interaction between these genetically distinct pathogens has raised greater concern regarding the transmission dynamics of microsporidians in shrimp farming systems and adjacent ecosystems, which is an emerging threat to the shrimp industry in Bangladesh.

6. Immunological Responses of Shrimp to WSSV

Compared to the possession of real adaptive immune system in vertebrates, shrimp have a well-developed innate defense mechanism. The system is characterized by a non-specific immunological response, usually segregated into cellular and humoral components and activated pattern recognition receptors (PRPs) (Kulkarni, Krishnan et al. 2021). So far, several PRRs have been identified in Penaeid shrimp including toll-like receptors (TLRs), lectin, tetraspanin, and lipopolysaccharide and β-1,3-glucan binding protein (Li and Xiang 2013). These receptors play a central role in the recognition of pathogens and in triggering of immune responses in shrimp.

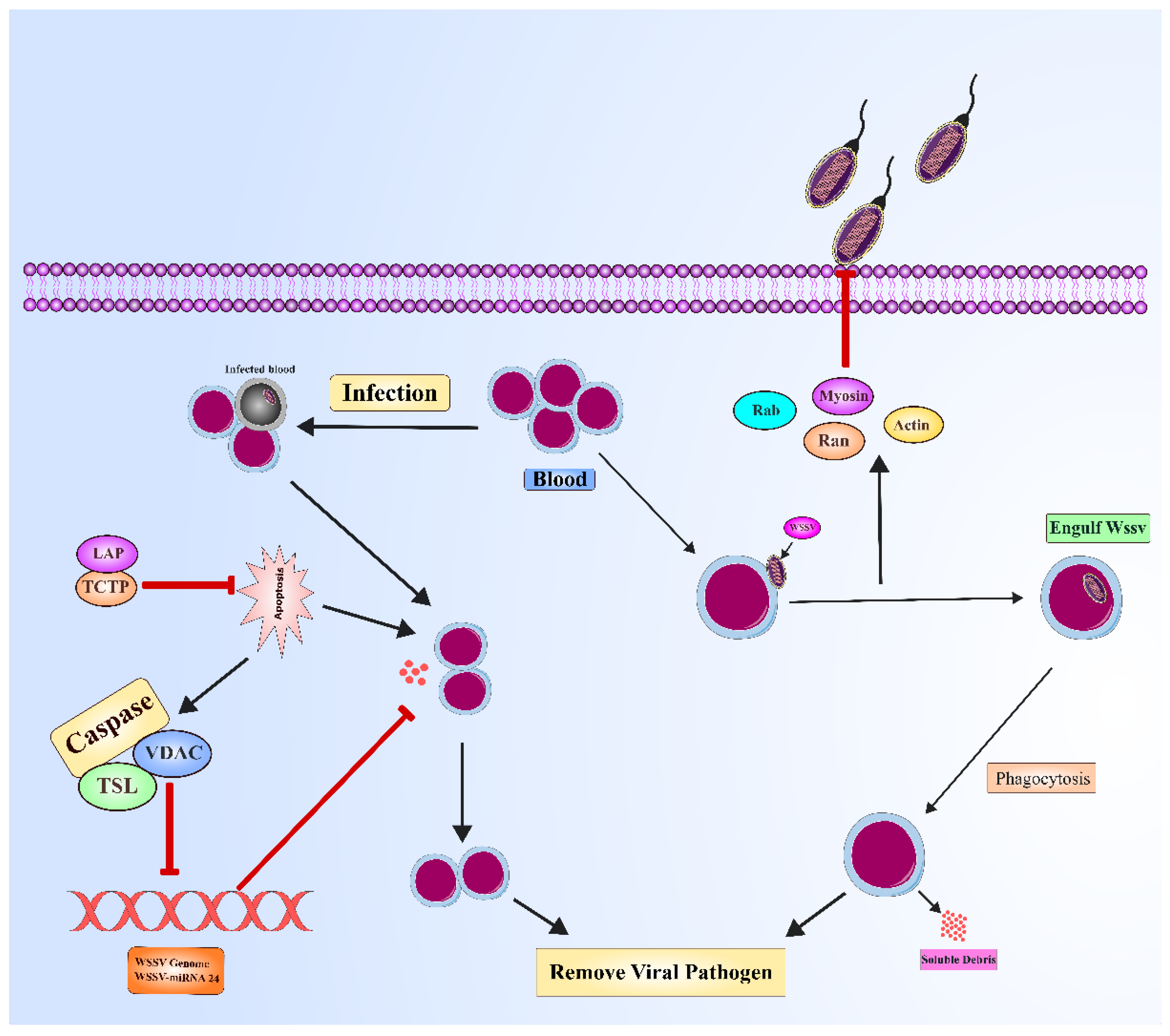

Cellular immune mechanisms in shrimp: Cellular immunity addresses the recognition and elimination of pathogens through various mechanisms, including phagocytosis, encapsulation, and apoptosis (

Figure 6). Hemocytes are circulating immune cells that essentially carry out the process in shrimp through phagocytosis, wherein pathogens are taken up and degraded. This also involves different small GTP-binding proteins such as Ran and Rab (Abubakar, Atmaca et al. 2015), reflecting the complexity of shrimp cellular immune responses. Crucially, hemocytes depend on immune mediators like lectins to improve their ability to recognize and respond to pathogens. Lectins are one of the most common classes of immune mediators, which are characterized by a carbohydrate recognition domain (Liu, Zheng et al. 2020). In shrimp, C-type lectins (CTLs) facilitate phagocytosis of microbial pathogens through opsonization, marking the pathogens for ingestion by immune cells. More directly, CTLs exhibit immunity by agglutination and inhibiting microbial growth, including gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Wang and Wang 2013). C-type lectins also show antiviral activity, especially against WSSV. A range of lactins, such as MjsvCL, LdlrLec1, LdlrLec2, LvAV, FmLC5, and FLdlr (found in

Fenneropenaeus merguiensis , Litopenaeus vannamei, and Marsupenaeus japonicus species) has been reported with anti-WSSV functions (Wang, Vasta et al. 2020). However, some lectin genes, for example LvCTL3 (found in

L. vannamei) and FmLC3 (found in

F. merguiensis), are paradoxically demonstrated to enhance their vulnerability to WSSV (Runsaeng, Kwankaew et al. 2018). These findings demonstrate the complexity of lectin immune modulation wherein their regulatory role may support or hinder resistance against pathogens. Recent studies have shown that the NFkB pathway could modulate CTLs expression in

L. vannamei. (Li, Li et al. 2014), again suggesting that in shrimp immune responses are controlled at every level in a highly ordered way.

Programmed cell death or apoptosis is another aspect of cellular immunity that helps shrimp eliminate cells harboring infectious agents (Cui, Liang et al. 2020). Apoptosis is typically brought about by various apoptosis-related genes such as caspases, inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP), apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), cytochrome c, the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), Fortilin or translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP), gC1qR, BAX inhibitor-1 (BI-1), and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) (Elmore 2007). These molecular components are important in coordinating the controlled and targeted destruction of cells, which is an important feature of the shrimp's immune response (Tang, Cui et al. 2019). Caspase are proteases that initiate the early phase of apoptosis in response to external signals. Apoptosis allows shrimp to limit pathogen dissemination in tissues by destroying infected cells in a timely manner (Clarke and Clem 2003). Shrimp were found to be resistant to WSSV by apoptosis-mediated blocking of viral propagation, hence hindering the virus from spreading in the host cells of shrimp (Huang, Cui et al. 2014). However, WSSV also evolved anti-apoptotic proteins such as AAP-1 (ORF390 or WSSV449), WSV222, VP38, WSSV134, and WSSV322 that delay or inhibit normal apoptosis, allowing completion of the viral replication cycle and further infection of other cells (Kulkarni, Krishnan et al. 2021).

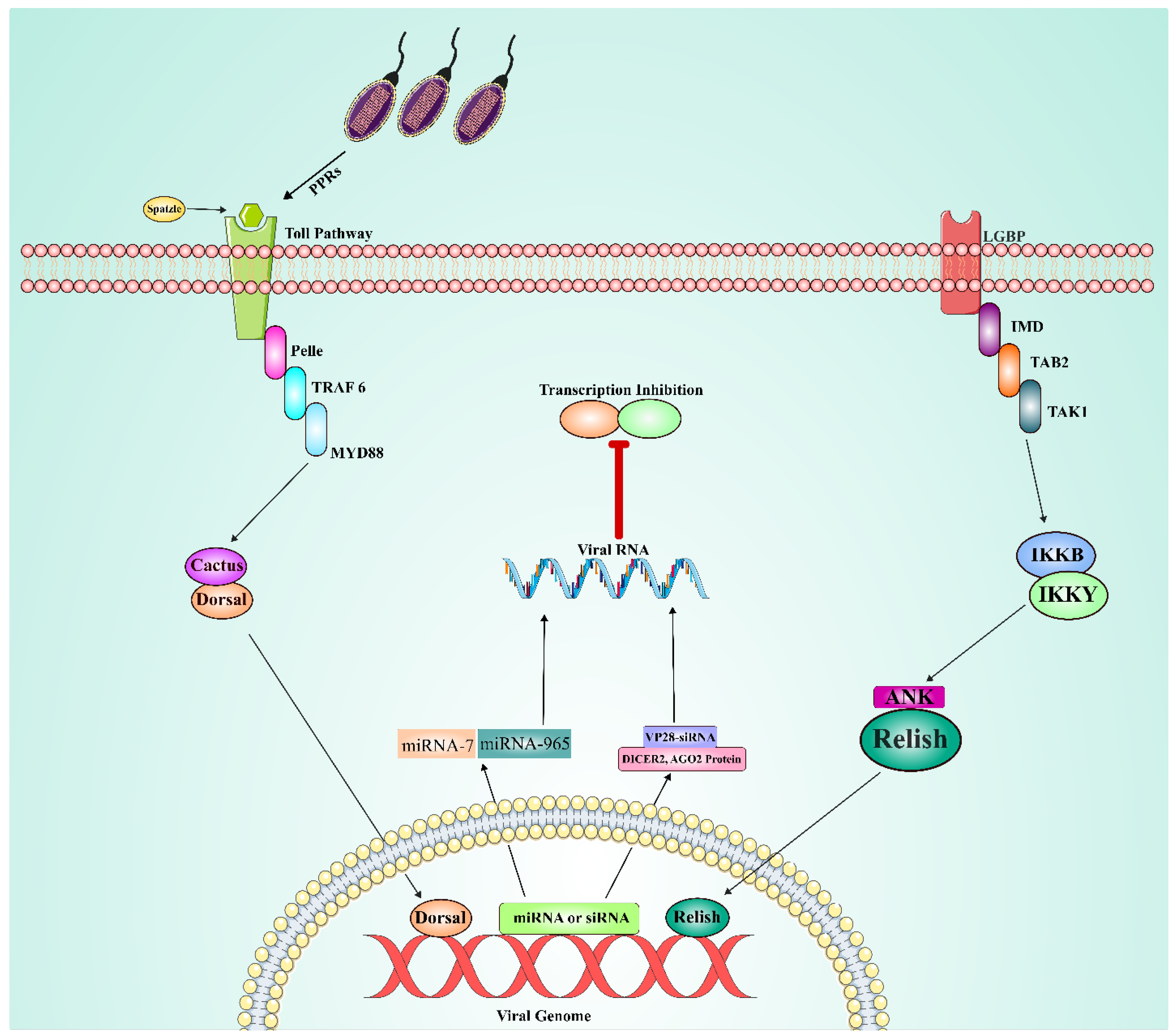

Humoral immune mechanisms in shrimp: In view of the absence of lymphocytes and immunoglobulins in shrimp, much dependence is placed on the humoral immune response as a complement to cellular immunity. Various biological macromolecules, including antimicrobial peptides, phosphatase, and lysozyme, are involved in mediating humoral immunity in shrimp against pathogen invasion (Kulkarni, Krishnan et al. 2021). It has been found that these molecules show crucial activity related to the recognition and neutralization of pathogens, thereby preventing their proliferation within the host (Wang and Zhang 2008). The Toll, IMD and JAK/STAT pathways are considered the main signaling pathways of the humoral response in shrimp, especially in their immune response to viral infections like WSSV (

Figure 7). Expression of the canonical Toll pathway has been well characterized in several shrimp species, including

L. vannamei, P. monodon, M. rosenbergii, P. clarkii, F. chinensis, and M

. japonicus (Mekata, Kono et al. 2008, Yang, Zhang et al. 2008, Feng, Zhao et al. 2016, Huang, Li et al. 2017, Liu, Xu et al. 2018, Yao, Su et al. 2018). Key molecules in this pathway include Spätzle, Toll, MyD88, Tube, Pelle, Pellino, TRAF6, Dorsal, Cactus, Tollip, SARM, Flightless-I, and b-arrestin, each of which plays subsequent roles in the activation of immune responses (Li, Wang et al. 2019). Interestingly, up to date, 25 Toll-like receptor genes have been identified in shrimp, with species-specific variations. These include LvToll1-9 from

L. vannamei, PmToll1 and PmToll9 from

P. monodon, FcToll from

F. chinensis, PcToll and PcToll1-5 from

P. clarkii, MjToll1-2 from

M. japonicas, as well as two MrTolls and MrToll1-3 from

M. rosenbergii (Yang, Yin et al. 2007, Mekata, Kono et al. 2008, Yang, Zhang et al. 2008, Wang, Tseng et al. 2010, Assavalapsakul and Panyim 2012, Wang, Liang et al. 2012, Hou, He et al. 2014, Srisuk, Longyant et al. 2014, Wang, Chen et al. 2015, Lan, Wei et al. 2016, Lan, Zhao et al. 2016, Guanzon and Maningas 2018). These findings highlight the evolutionary adaptation of the Toll pathway in shrimp to respond in a species-specific manner against pathogens.

The immune deficiency (IMD) pathway, first identified in L. vannamei in 2009 (Wang, Gu et al. 2009), also contributes to antiviral humoral immunity. Several IMD homologs known to have conserved functions have become species-specific regarding tissue distribution and immune response (Lan, Zhou et al. 2013). For example, FcIMD is mainly expressed in the stomach and gills from F. chinensis, while PcIMD is highly expressed in the hepatopancreas, stomach and heart from P. clarkia (Wang, Gu et al. 2009). The IMD pathway contains several canonical gene components (Relish, TAK1, TAB1, and TAB2) shared with the Toll pathways and are involved in activating immune response (Li and Xiang 2013). L. vannamei has been found to express LvTAK1 and LvTAK2, where these Toll-like receptors regulate the expression of various antimicrobial peptides in vivo (Wang, Li et al. 2016). In addition, Lvb-TrCP, LvMKK6, LvAkirin, LvNKRF, LvRelish exhibit strong responses to WSSV viral infection from L. vannamei. Along with PmRelish, FcRelish, FcMKK4, and FcP38 also show activity against viral infections like WSSV in the M. japonicas, F. chinensis (Li, Wang et al. 2019).

Compared to the well-characterized Toll and IMD pathways, the role of the JAK/STAT pathway during WSSV infection remains unclear; however, recent studies have unraveled the dual function of the JAK/STAT pathway in WSSV infection. In the JAK/STAT pathway, LvSOCS2 activates the expression of antimicrobial peptides, exhibiting an antiviral role in L. vannamei. Conversely, LvJAK promoted infection with viral genes such as WSV069 during the early stages of WSSV infection (Li, Weng et al. 2019). From these observations, it seems that in general the JAK/STAT pathway plays a dual role (positive or negative) during a viral infection depending on the different stages of infection and specific immune factors involved.

RNA interference (RNAi) and microRNA (miRNA) in shrimp immunity: Another important aspect of shrimp immunity is that RNAi and miRNA are involved in regulating immune responses. RNAi mediated by siRNAs has been found to be an essential defense against viral infections (Xu, Han et al. 2007). Shrimps produce siRNAs specific to viruses, like vp28-siRNA against WSSV infection, lowering viral replication by targeting viral genes in hemocytes. The main RNAi machinery elements, Dicer2 and Argonaute2, take part in the generation and function of siRNAs in antiviral reactions (Zhu and Zhang 2011, Sabin and Cherry 2013). Along with RNAi, miRNAs have also become important controllers of shrimp immune reactions (Kaewkascholkul, Somboonviwat et al. 2016). Various miRNAs displaying differential expression resulting from infection by WSSV have been identified through miRNA microarray analysis. For example, miR-7 and miR-965 have been identified as down-regulators of WSSV early genes, such as wsv477 and wsv240 (Huang and Zhang 2012, Shu, Li et al. 2016) respectively, which ultimately inhibit viral replication and subsequent infection (He and Zhang 2012). In addition, miR-965 has been shown to enhance phagocytic activity via autophagy-related gene-5, a gene involved in autophagy – thereby aiding in the phagocytosis of viral pathogens. On the contrary, some other viral miRNAs, such as WSSV-miR-66 and WSSV-miR-68, enable viral infection via the enhancement of expression levels during the early stage in WSSV infection by enhancing the expression of viral genes (wsv094, wsv177, wsv248 and wsv309) (He, Yang et al. 2014). These findings illustrate the complex interplay between host and viral miRNAs in regulating immune responses during WSSV infection.

7. On-Going Research on Control Measures

The conventional control methods of WSSV involve the use of antibiotics, which have mostly proved ineffective and also cause harm due to bioaccumulation; hence the need for other strategies (Lulijwa, Rupia et al. 2020). Continuous research has shifted towards newer approaches involving the use of immunostimulants, dietary interventions, and advanced technologies such as CRISPR technology and nanotechnology (Govindaraju, Dilip Itroutwar et al. 2020, Mariot, Bolívar et al. 2021, Ferdous, Islam et al. 2022, Zhang, Shan et al. 2022, Gong, Pan et al. 2023, Kumar, Verma et al. 2023, Galib, Ghosh et al. 2024, Namitha, Santhiya et al. 2024, Pudgerd, Saedan et al. 2024). These new methodologies have promising applications in the control and possible eradication of the virus, thereby offering a ray of hope to shrimp farmers.

Immunostimulants have become a strong tool in the arsenal of enhancing immunity in shrimp against WSSV infection. Different natural substances, seaweed extracts, essential oils, probiotics, plant-based chemicals and animal-derived immunostimulants have proven their efficacy by enhancing the resistance of shrimp to viral infections through boosting innate and non-specific? immunity (Citarasu 2010, Huang and Zhang 2013, Bindhu, Velmurugan et al. 2014, Rajashekar Reddy, Dinesh et al. 2016, Xie, Liu et al. 2019, Salehpour, Biuki et al. 2021, Huang, He et al. 2022, Ghosh 2023). One such compound is fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide extracted from brown algae such as Fucus vesiculosus. In shrimp, it enhances hemocyte counts, respiratory activity, and prophenoloxidase activity (Sinurat, Saepudin et al. 2016). All these mechanisms are capable of preventing viral replication, thereby reducing WSSV infection intensity. Another example is the sulfated galactan from red algae, which interacts with viral proteins VP26 and VP28, thereby preventing virus attachment to shrimp cells and further severely impeding its entry and replication (Rudtanatip, Asuvapongpatana et al. 2014). A few other promising compounds that exhibit antiviral activity include epigallocatechin gallate from green tea and naringenin from citrus fruits (Sun, Chen et al. 2021, Zhang, Wen et al. 2022). These natural compounds upregulate important immune-related genes, such as those involved in viral replication, providing shrimp with enhanced immunity against WSSV. Medicinal herbs like Agathi grandiflora and Argemone mexicana have already shown their efficacy in increasing shrimp immunity against WSSV replication (Bindhu, Velmurugan et al. 2014, Palanikumar, Benitta et al. 2018). These immunostimulants are especially important, as no effective antiviral drugs are currently known that would boost shrimp defenses naturally. For developing effective antiviral drug, targeting conserved proteins such as ribonucleotide reductase in critical stages of the virus life cycle could be a viable strategy. Inhibitors against such conserved enzymes could be effectively utilized against a wide range of dsDNA viruses, including WSSV. For example, ribonucleotide reductase is an essential enzyme involved in nucleotide metabolism and DNA synthesis; interference with its activity might disrupt viral replication (Krishnan, Katneni et al. 2023).

The use of probiotics, which are beneficial bacteria improving shrimp gut health and strengthening immune responses, is another promising avenue in WSSV defense. Some of the cited probiotics include Pediococcus pentosaceus, Lactobacillus and Bacillus spp which have been shown to stimulate the shrimp's immune system. These probiotics enhance the activities of important immune-related enzymes such as phenoloxidase (PO) and prophenoloxidase (proPO), which play a critical role in shrimp immune response against viral infections (Dekham, Jones et al. 2023, Ghosh 2023). Probiotics like Bacillus subtilis and Vibrio alginolyticus enhance the activity of digestive enzymes, leading to improved growth and resistance against WSSV (Rodríguez, Espinosa et al. 2007, Sekar, Kim et al. 2019). Additionally, how probiotics enhance the gut microbial structure of shrimp to create an environment less permissive tor WSSV replication is a very promising avenue of research. Dietary interventions, such as the inclusion of bioactive compounds into shrimp feed, have been highly successful in conferring immunity in shrimp against WSSV. Quercetin, a bioactive flavonoid present in several fruits and vegetables, has been demonstrated to significantly upregulate immune-related genes such as TLR, ALF, and NF-κB, playing a key role in the control of viral infections and regulation of cell growth and death (Chen, Fan et al. 2023, Yang, Wang et al. 2024). Other dietary compounds, such as inulin, galactooligosaccharides, carotenoids, and polyphenols from chestnuts and olive extracts, have also been found effective in enhancing the immune response of shrimp and thereby reducing mortality due to WSSV (Luna-González, Almaraz-Salas et al. 2012, Mustafa, Buentello et al. 2019, Tan, Zhang et al. 2020). Another major advantage of dietary interventions is their efficiency in maintaining the health of the gut, thereby indirectly improving the immune system in shrimp. These dietary compounds promote nutrient digestibility and digestive enzyme secretion through maintenance of orderly gut microbiota, resulting in better growth and resilience to viral infections such as WSSV. Essential oils from plants such as Zanthoxylum tsihanimposa and Eucalyptus globulus were also recommended as effective natural treatments for WSSV (Babikian, Babikyan et al. 2020, Zafilaza, Andriantsimahavandy et al. 2020). The bioactive components of these oils, including terpinene and thymol, exhibit robust antiviral, antimodulatory, and antioxidant activities. Even essential oils, like thyme, when protected against deterioration by microencapsulation, were found to enhance the immune response of shrimp by boosting PO activity, thereby increasing survival upon WSSV infection (Tomazelli Júnior, Kuhn et al. 2018). Additionally, blending different essential oils can result in synergistic interactions among components, further enhancing antiviral properties (Tariq, Wani et al. 2019). This multilevel natural approach presents a hopeful alternative to chemical treatments and actively offers shrimp farmers a more sustainable and eco-friendly solution for WSSV control.

Apart from these nutritional and phytochemical based research, nanotechnology provides advanced solutions in the detection and prevention of WSSV. For example, the use of Surface Plasmon Resonance and DNA functionalized with gold nanoparticles enables more sensitive and accurate detection of WSSV in shrimp (Bai, He et al. 2023). These technologies support real-time monitoring of viral loads in shrimp populations, allowing for timely and efficient management of the virus. For prevention, PVP-coated silver nanoparticles have great potential in enhancing shrimp immunity, thereby increasing survival rates against WSSV infection (Namitha, Santhiya et al. 2024). These nanoparticles enhance the effectiveness of DNA vaccines and immunostimulants by enhancing delivery to target cells, offering better protection against the virus. Nanotechnology thus plays an important role in both detection and prevention of WSSV, raising new hope for shrimp aquaculture. In recent years, polyanhydride nanoparticles have gained attention as a novel method for delivering vaccine antigens and emerged as strong potential for encapsulating and controlling the release of dsRNA molecules to manage disease in shrimp aquaculture. Notably, research by Phanse et. al., (2022) advanced the use of dsRNA-based nano-vaccine to fight viral infections in shrimp species like L. vannamei. Their study highlights that nanoparticle made from copolymers of sebacic acid, 1,6-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy) hexane, and 1,8-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy)-3,6-dioxaoctane achieved an impressive ~80% protection rate in shrimp when challenged with WSSV. This high level of protection underscores the potential of these nanoparticles as effective dsRNA carriers, enhancing immune responses and providing a strong defense against viral threats. Alongside polyanhydride nanoparticles, virus-like particles (VLPs) present another promising tool for controlling diseases in shrimp, particularly for delivering dsRNA (Phanse, Puttamreddy et al. 2022). VLPs resemble viruses structurally but do not contain any viral genetic material, making them ideal for bypassing host defenses and safely transporting therapeutic dsRNA. Because they mimic the external properties of viruses, VLPs can stimulate immune responses without the risk of causing infection. Studies by Pudgerd, Saedan et al. (2024) and Weerachatyanukul, Pooljun et al. (2022) have shown that capsid proteins from viruses like infectious hypodermal and haematopoietic necrosis virus and Macrobracium rosenbergii nodavirus can be used to encapsulate and deliver dsRNA molecules, such as VP28 and VP37, which are known to boost immune responses and limit viral replication in shrimp. These findings suggest that VLPs not only protect dsRNA from breakdown within host cells but also improve the uptake and stability of these therapeutic molecules. Beyond VLPs, several other nanoparticle platforms are being explored to deliver dsRNA to shrimp. Plant virus-based particles like cowpea chlorotic mottle virus and brome mosaic virus, as well as non-viral nanoparticles such as liposome, chitosan and beta-glucan, are under study for their potential in dsRNA delivery (Itsathitphaisarn, Thitamadee et al. 2017, Abo-Al-Ela 2021, Ramos-Carreño, Giffard-Mena et al. 2021, Ruiz-Guerrero, Giffard-Mena et al. 2023, Jonjaroen, Charoonnart et al. 2024). Each of these systems offers unique benefits, like biocompatibility, high encapsulation efficiency, and controlled release capabilities.

One of the most promising recent developments in WSSV research involves the use of DNA vaccines, which work by encoding specific viral proteins such as VP28 into shrimp cells to trigger an immune response. Such vaccines have been shown to increase survival rates by enhancing enzymatic activities in shrimp, such as super-oxide dismutase (SOD) and alkaline phosphatase (AKP), which are generally induced during a viral infection (Du, Hu et al. 2022). These DNA vaccines targeting the VP28 gene (focusing on conserved regions, areas less likely to mutate in the WSSV genome) express specific immunity proteins that bind to and neutralize the virus, preventing further replication and spread (Krishnankutty Chandrika and Thavarool Puthiyedathu 2021, Mugunthan, Loganathan et al. 2025). Moreover, the global distribution and genetic diversity of WSSV (discussed earlier in section 4.2), along with its evolutionary trajectory (adaptation and mutation in response to climate change) will be helpful in identifying conserved regions in the viral genome – a promising candidate for vaccine development. Vaccines designed around these stable sequences would likely remain effective unless these regions undergo significant changes, providing a more reliable way to combat WSSV outbreaks. Other types of DNA vaccines coated with chitosan show high potential. The coating protects the vaccine from degradation and allows oral delivery, resulting in higher efficacy in preventing WSD (Feng, Wang et al. 2017, Wikumpriya, Prabhatha et al. 2023). Shrimp farmers may soon have a more reliable long-term solution for managing outbreaks with the recent development of DNA vaccine technology. Apart from DNA vaccines, RNA-based vaccines have also been shown to provide specific and robust protection against WSSV infection in cultured shrimp. However, the major challenge for field application of these vaccines is the limited stability of double-stranded RNA in aquatic systems (Phanse, Puttamreddy et al. 2022). Therefore, researchers have focused on developing RNA interference and nanoparticle-based RNA vaccines to inhibit WSSV. Since then, many WSSV genes (VP19, VP28, rr1 and rr2) have been used as targets for RNAi-mediated neutralization of WSSV (Sanjuktha, Stalin Raj et al. 2012, Rattanarojpong, Khankaew et al. 2016, Li, Hong et al. 2019, Krishnankutty Chandrika and Thavarool Puthiyedathu 2021). Additionally, RNAi targeting of non-WSSV genes (PmRab7, PmRab7/PmIAP and GFP) was also tested for their ability to prevent WSSV infection (Kulkarni, Caipang et al. 2014, Alenton, Kondo et al. 2016). In particular PmRab7 + rr2 showed high activity, reducing viral genome replication by approximately 95%.

CRISPR-Cas gene editing in WSSV research has introduced a new paradigm for improving shrimp resistance to viral infections. This technology enables researchers to edit the DNA of shrimp with precision, either directly at viral DNA or by modifying genes involved in immune suppression (Ferdous, Islam et al. 2022). For instance, some neuroendocrine hormones like GIH and MIH suppress the immune system, making shrimp more susceptible to WSSV infection (Wang, Li et al. 2019, Wei, Pan et al. 2020). These genes could be edited using the CRISPR-Cas technology to enhance natural immunity in shrimp against viral attack (Diwan, Ninawe et al. 2017). CRISPR-Cas biological systems can reproduce and insert small segments of DNA corresponding to WSSV as spacers between short repeat sequences into the genomes of host shrimp. This occurs during the invasion of WSSV in these shrimps. These spacers improve the immune response of shrimp by providing a template for rapid recognition and targeting of the same DNA sequence by RNA molecules during subsequent viral infections (Ferdous, Islam et al. 2022). Recent advances in transcriptome analyses also help researchers understand how shrimp respond to WSSV at the genetic level. These analyses identified key genes and pathways upregulated in response to WSSV infection, providing insight into how functional feeds might influence gene expression and improve shrimp survival. Feeds have also been reported to enhance antioxidant activity and immune responses, helping to moderate the effects of WSSV. Proteins identified in several proteome studies include proPO, lysozyme, and crustin, which showed increased expression during WSSV infection (Sun, Wang et al. 2017, Thamizhvanan, Nafeez Ahmed et al. 2021). Therefore, the genetic and proteomic changes discussed above may contribute to better design of specific treatments through diets and immunostimulants that enhance resistance to viral infections in shrimp. However, proteomics studies on WSSV are currently limited, highlighting the need for more extensive research to identify the functions of viral structural proteins and explore the potential of envelope proteins as subunit vaccines for host protection. Enhanced efforts in protein identification and structural characterization are essential to advance this area.

The growing threat of WSSV in shrimp farming has necessitated the development of alternative control strategies beyond traditional methods like antibiotics, which have proven ineffective and harmful. Recent advances in immunostimulants, dietary interventions, probiotics, essential oils, DNA vaccines, nanotechnology, and CRISPR-Cas gene editing offer promising solutions for enhancing shrimp immunity and preventing WSSV outbreaks. The continued integration of these technologies, along with a deeper understanding of shrimp immune responses through transcriptome and proteomic analyses, holds the key to future breakthroughs in combating WSSV.

8. Future Research Direction

WSSV is one such pathogen, and the battle against it in shrimp aquaculture underscores the urgency for novel means of control that are environmental-friendly and effective. Although WSSV was one of the first shrimp viruses to be studied in depth, it remains one of the major viral agents affecting shrimp farming worldwide, causing severe economic losses and food security concerns. In this review, we have illustrated the current knowledge of WSSV, with a special focus on virus sensing and manipulation, spread mechanisms, and the strategies being applied in aquaculture to ensure biosecurity, induce immunity, and apply biotechnology against WSSV. Yet, much more needs to be done to address unanswered questions and to develop scalable, long-lasting solutions.