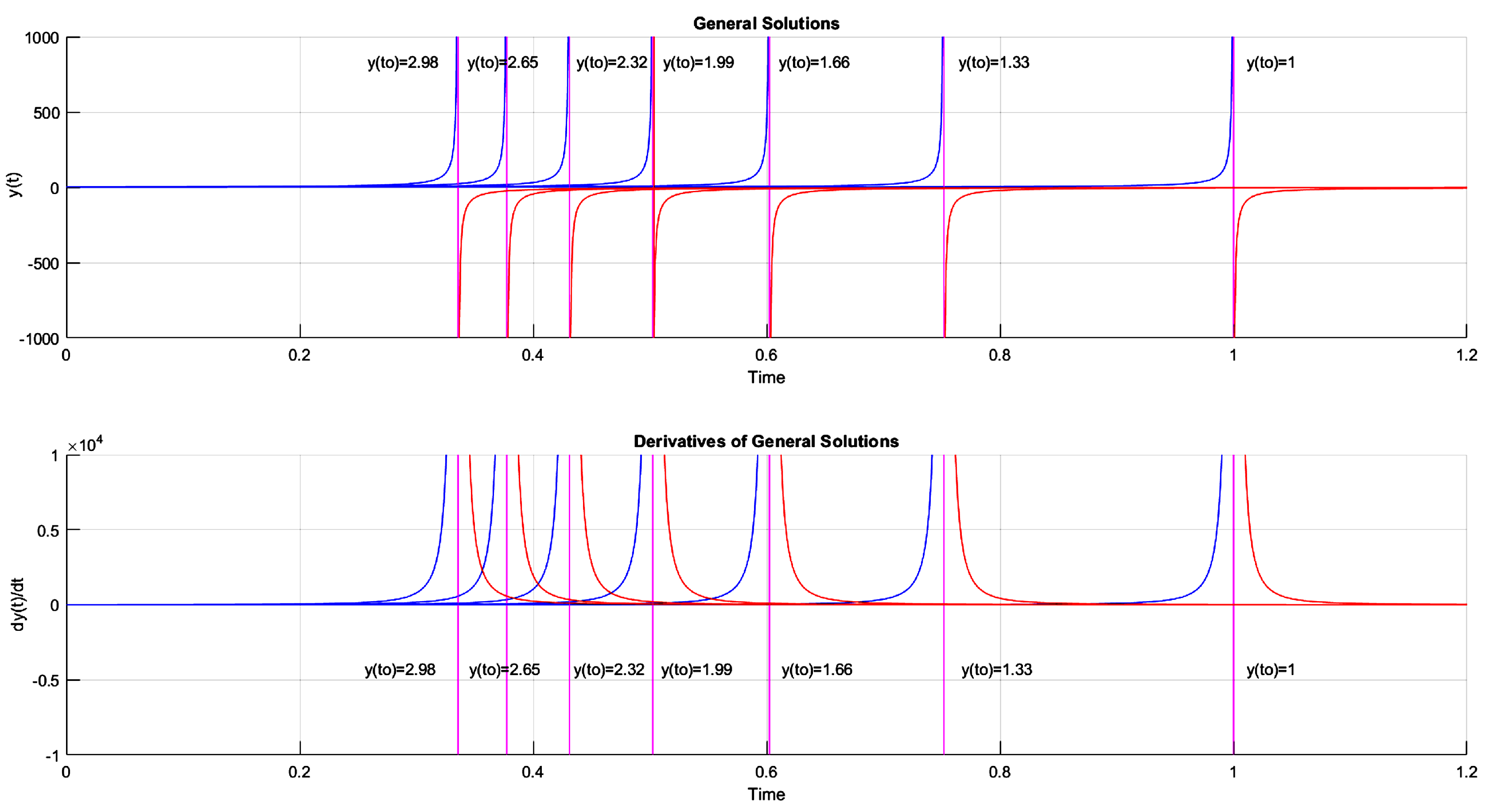

In this section, we present a concise and complete description of the Euler-Type Universal Numerical Integrator (E-TUNI). To this end, we present a formal mathematical proof for the general expression that governs E-TUNI’s operation to generate discrete solutions for autonomous nonlinear dynamical systems governed by ordinary differential equations. Additionally, we also present the correct way to use E-TUNI in a predictive control framework. We conclude this section by obtaining an approximate mathematical expression for E-TUNI to provide a continuous solution, rather than a discrete solution, for autonomous dynamical systems.

3.1. Basic Mathematical Development of E-TUNI

We provide a brief mathematical description of E-TUNI below. Then, in the following sub-section, we perform a formal mathematical demonstration of the general expression of the first-order Euler Integrator designed with mean derivative functions. So, by definition, the secants or mean derivatives

for

between the points

and

are given by:

where,

is the forward state of the dynamic system,

is the present state of the dynamical system, the over-index

k on the left indicates the instant

k, the over-index

i on the right suggests a discretization of the continuum, the sub-index

j on the right indicates the j-th state variable,

n is the total number of state variables and

is the integration step. We talk more about the over-index

i later in this article.

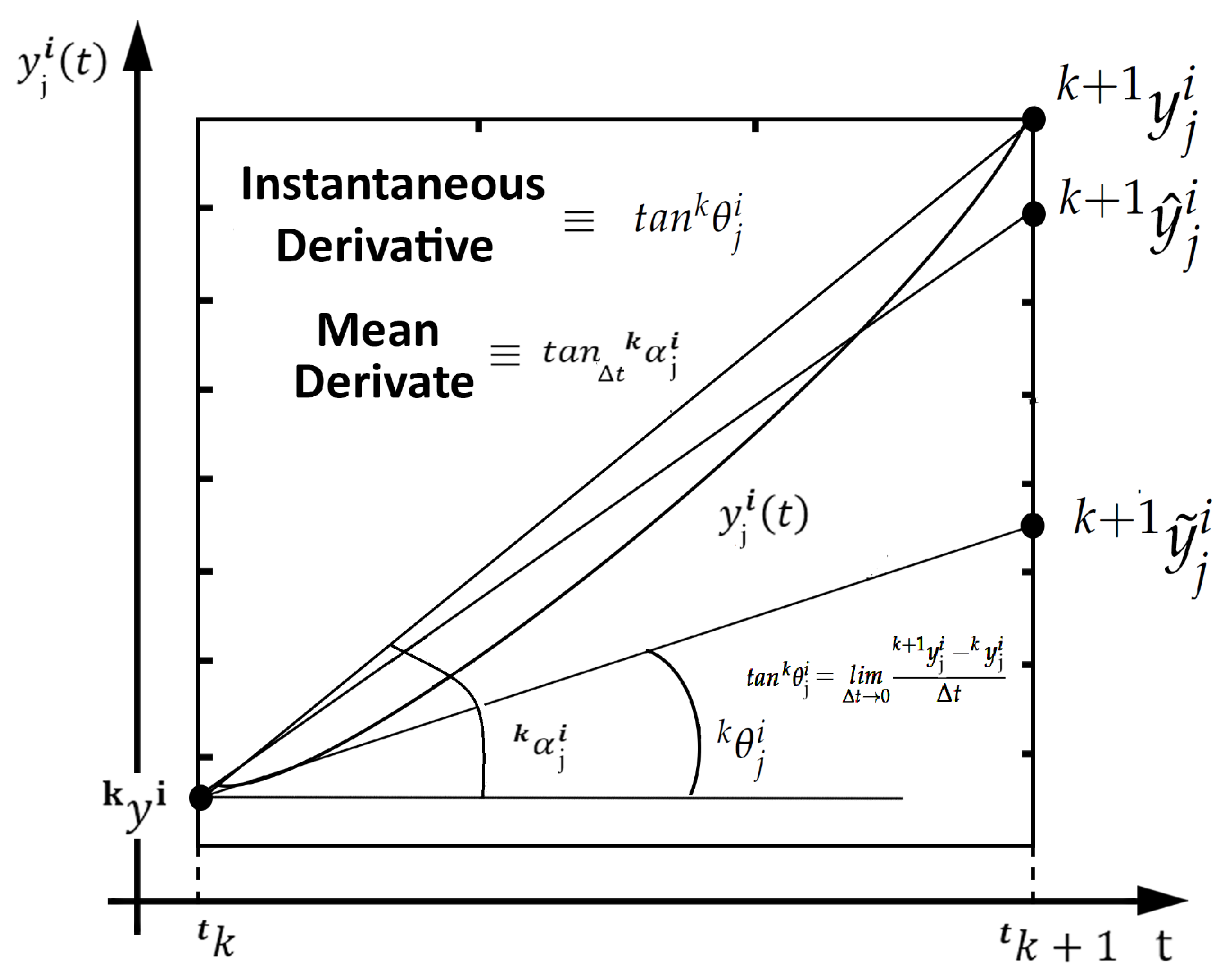

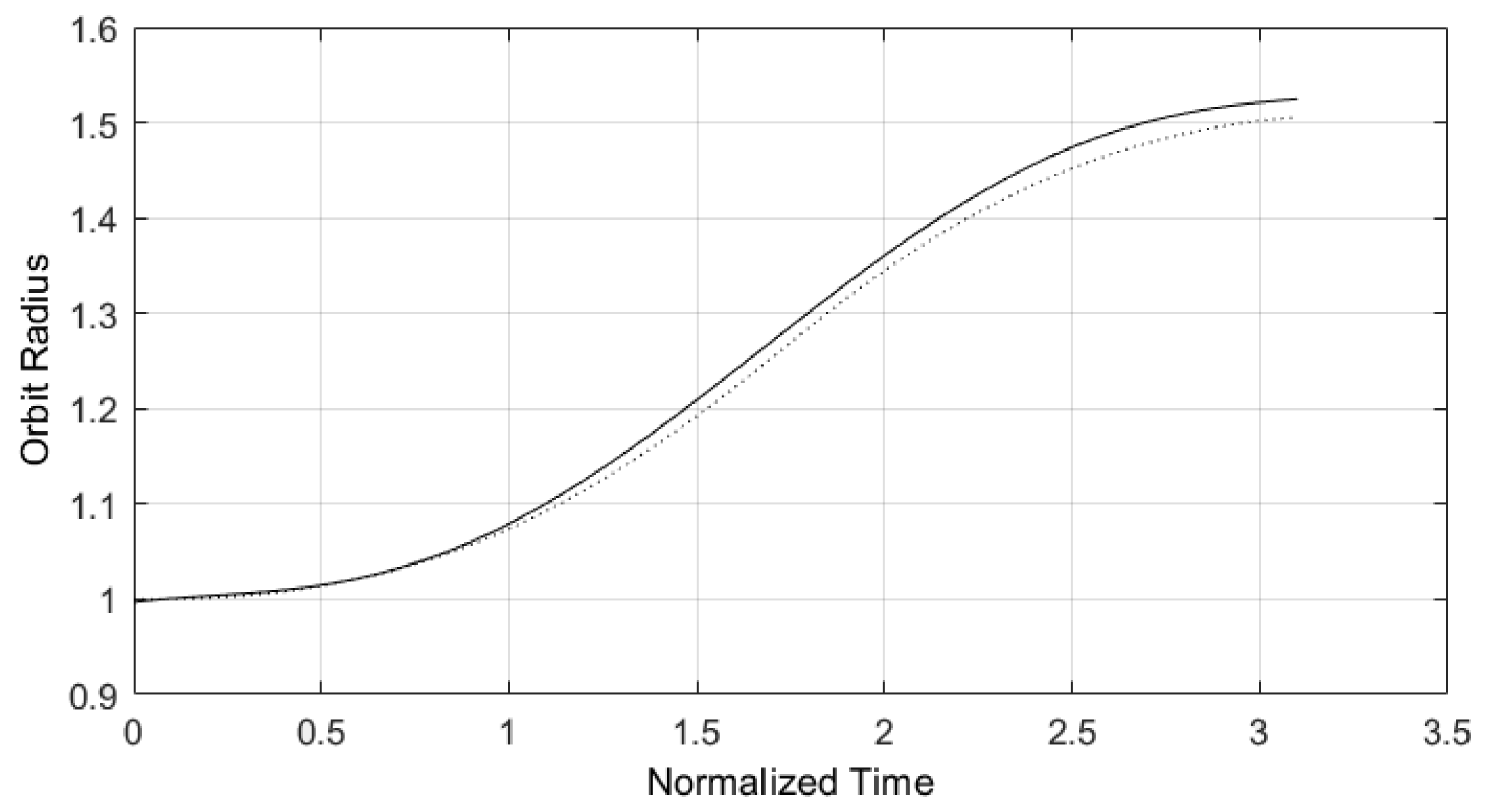

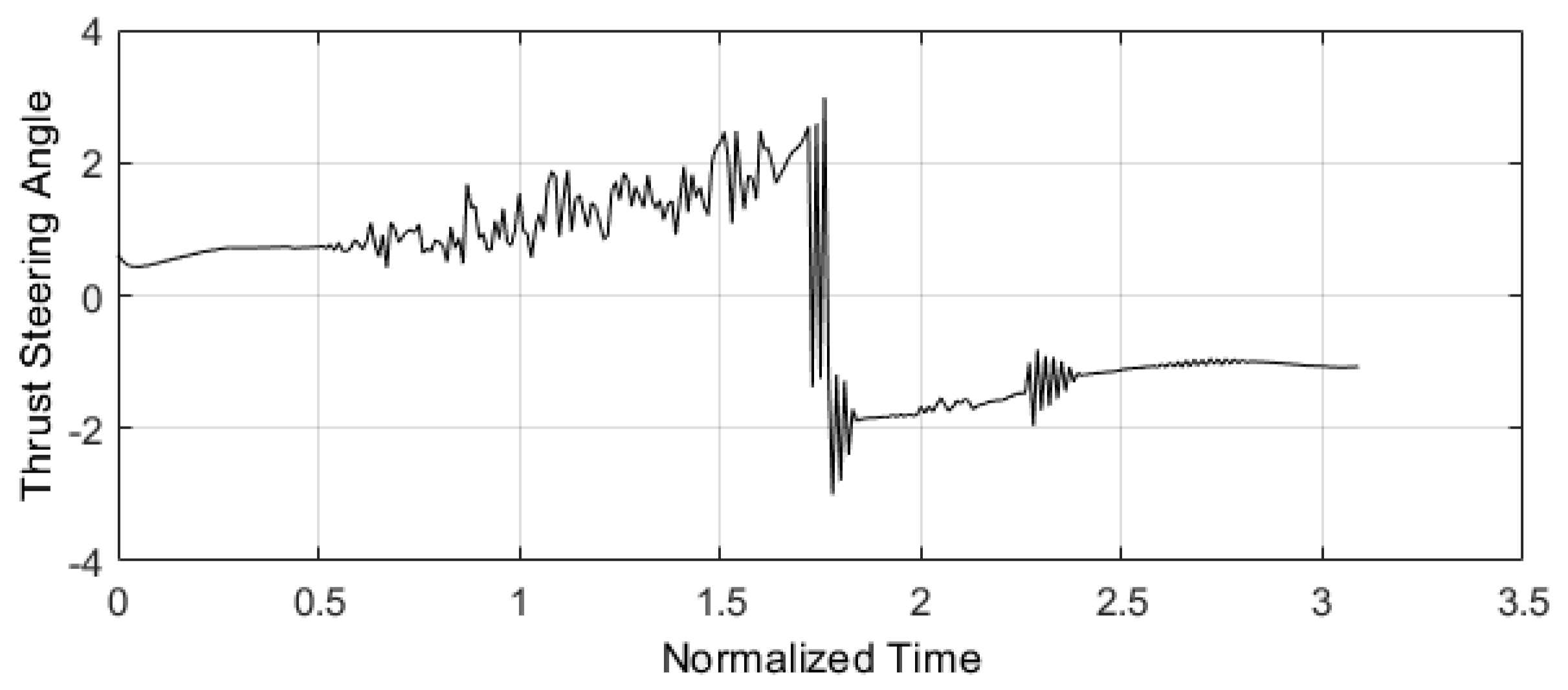

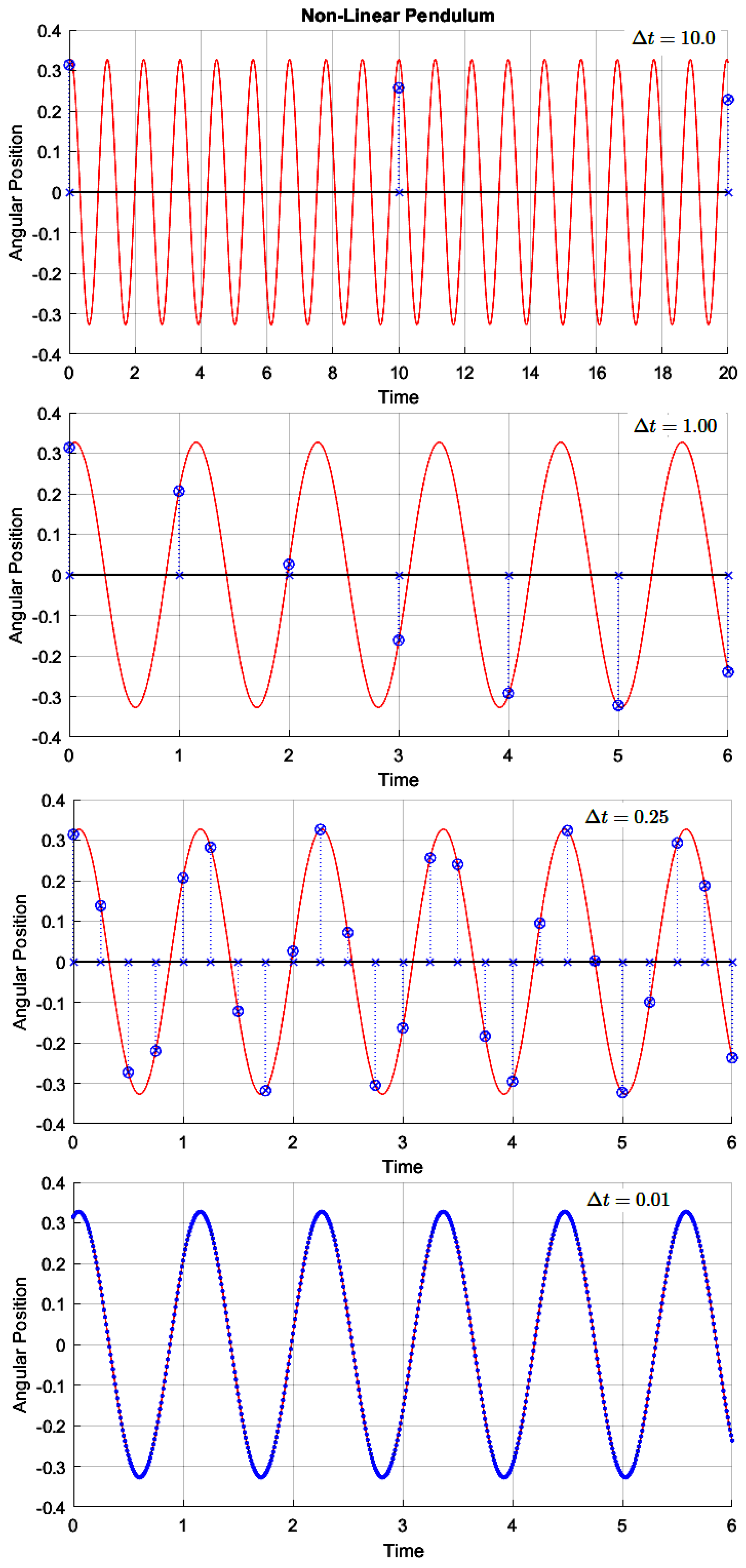

A geometric and intuitive difference between the mean and the instantaneous derivative functions is shown in

Figure 1. In line with the

Figure 1 and

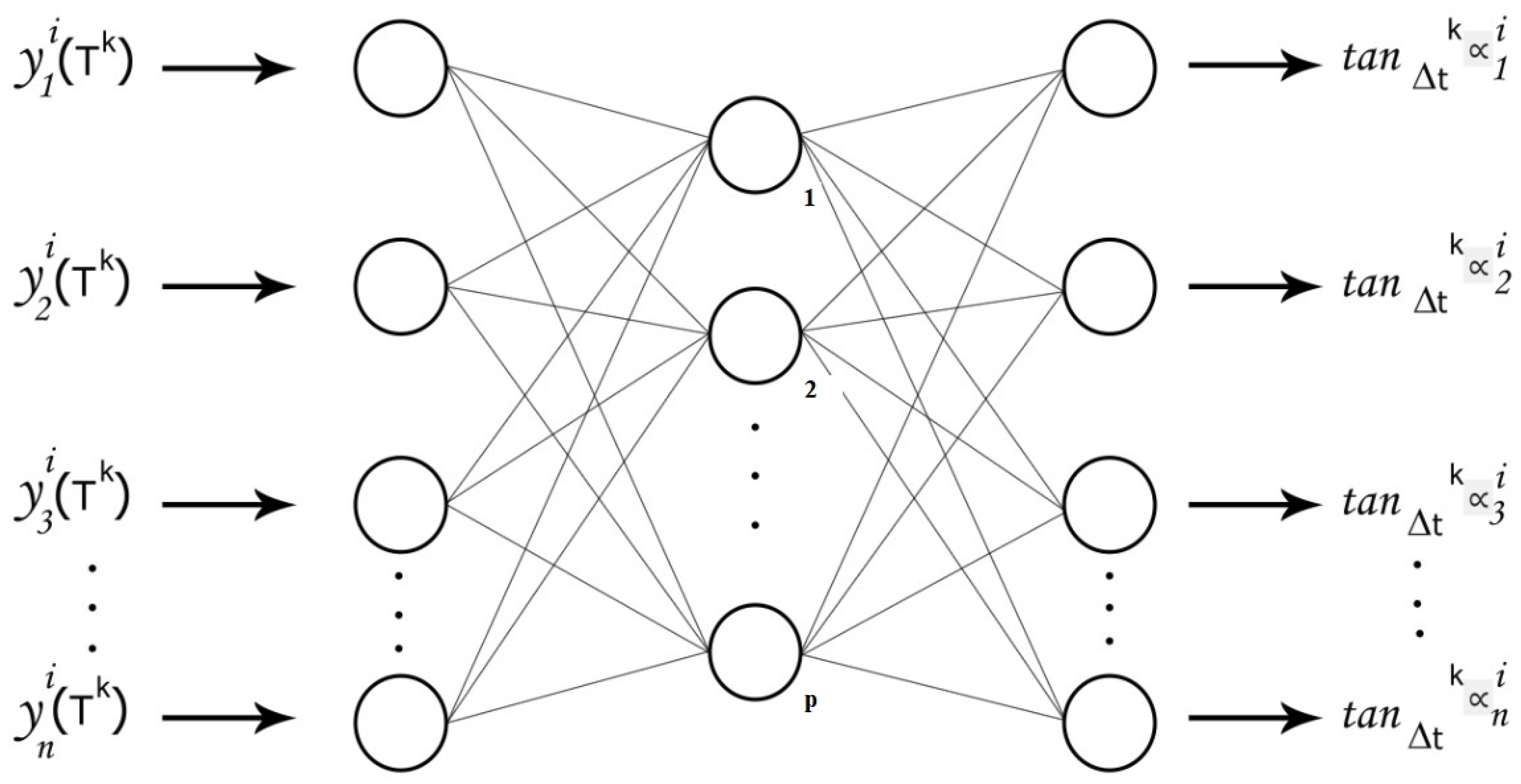

Figure 2, the E-TUNI is entirely based on the concept of mean derivative functions and not on the idea of instantaneous derivative functions. As will be seen throughout this article, this change is quite significant when incorporated adequately into the Euler-type first-order integrator. Furthermore, the mean derivative functions can also be obtained from supervised training with input/output patterns using a neural network with any feed-forward architecture (MLP, RBF, SVM, among others).

It is also essential to note that it is possible to train E-TUNI in two different ways, namely: a) through the direct approach or b) through the indirect or empirical approach. In the direct approach, the neural network is trained decoupled from the Euler-type integrator, while in the indirect or empirical approach, the neural network is trained coupled to the structure of the first-order Euler integrator. For this reason, in the indirect approach, the back-propagation algorithm needs to be modified slightly. In the references [

8,

17,

18] this is explained in more detail.

In this way, be a non-linear dynamic system of

n simultaneous first-order equations with dependent variables

. If each of these variables satisfies a given initial condition for the same value

a of

t, then we have an initial value problem for a first-order system, and we can write:

In [

14], the mathematician Leonard Euler himself proposed in 1768 the first numerical integrator, in the history of mathematics, to approximately solve non-linear dynamical systems governed by the equation (

2). This solution, which is well-known to everyone, is given by:

where,

for

are instantaneous derivative functions, according to the graphical notation shown in

Figure 1. On the other hand, there is an attempt in [

18] to prove mathematically that if you exchange the instantaneous derivatives in (

3) for the mean derivatives, then the solution proposed by Leonard Euler becomes accurate, i.e.,

Comparing equations (

3) and (

4), it is observed that the instantaneous derivative functions do not depend on the integration step, but the mean derivative functions do. Additionally, the equations in (

4) can also be expressed in a more compact notation, given by:

where,

[

…

,

[

…

e

[

…

. The generalization of the mean derivatives methodology to multiple backward inputs and/or multiple forward outputs is relatively easy. This expression can be obtained by following the equation:

where

p is the number of backward and/or forward instants and

. For example, if

then it is possible to design an E-TUNI with

inputs in the role of backward mean derivatives and

outputs in the role of forward mean derivative. In this way, the reader is free to choose the values of

and

as long as the previous equality is satisfied. However, it should be noted that the first input of the neural network must be an absolute value, not a relative one.

On the other hand, notice that if the reader tries to compare the NARMAX model with the E-TUNI structure, one can see that the former is very similar to the latter. In the NARMAX model, for example, the output of the universal approximator of functions is the forward instant . However, in the E-TUNI model, the output of the universal approximator of functions is the mean derivative function at the present instant. This description is the only practical difference between these two methodologies. However, the E-TUNI may be a little more computationally efficient than the NARMAX model, as explained in the following paragraph.

Considering the direct approach to training the mean derivative functions required by the E-TUNI structure, it is then possible to perform a theoretical analysis of the local error committed by this first-order universal numerical integrator. Thus, let the exact value

and the estimated value

be obtained, respectively, by the equations (

7) and (

8) of a given solution of a generic dynamical system.

where

is the mean absolute error of the output variables of the universal approximator of functions used to learn the mean derivative functions. Thus, if the equation (

7) is subtracted from the equation (

8) and the result of this subtraction is squared, we have:

The equation (

9) states that the local squared error made by E-TUNI can dampen the squared error of training the universal approximator of functions, used in neural training, if

. If

, the local error will be amplified. However, for a more accurate analysis of the global training error, further studies are needed.

The equation (

9) is fundamental, as it partially explains why training the E-TUNI with a mean square error

, greater than that obtained by training the NARMAX model can also yield good results from estimation and potentially surpass those obtained in the NARMAX methodology. However, as stated earlier, this is true only if

.

Therefore, an E-TUNI neural integrator can be used for supervised training of a generic plant. Additionally, this plant can be used in a predictive control framework. Thus, the plant’s neural model can be used, as a model of the system’s internal response to derive a smooth control policy. This control is then able to track a reference trajectory by minimizing a finite-horizon quadratic functional, given by [

16]:

where,

is the reference trajectory at the instant

;

m is the number of horizons ahead;

and

are positive definite weight matrices;

is the output of the previously trained E-TUNI. Thus, in [

16] it is shown that it is necessary to know the partial derivatives

to solve the problem of optimization given by the equation iteratively (

10) through the Kalman filter. Also, in [

16] these partial derivatives can be calculated as follows:

where,

In the equations (

11) to (

14), we have that

is the total number of state variables and

is the total number of control variables. Furthermore, to derive these equations, it was assumed that the neural network, which learns the mean derivative functions, was designed with only one late input for the state and control variables, and also only one forward output for the mean derivatives.

So, for example, if a neural network with an MLP architecture is used, the calculation of the partial derivatives, necessary for the use of the gradient training algorithm, can be obtained as follows [

16]:

where,

It is essential to note that

l is a generic layer of the MLP network. So

are the output values of the

l layer, and when

l is the last layer, then these outputs necessarily are the mean derivative functions. The

functions can be any sigmoid function. Furthermore, if another neural architecture is used, for example, RBF networks or Wavelets, it will only change the equation (

15). The equations (

11), (

12), (

13) and (

14) remain unchanged. The reason for this is that the equations from (

11) to (

14) refer exclusively to the type of integrator used, which, in this case, is necessarily the E-TUNI.

On the other hand, the equation (

15) refers exclusively to the type of feed-forward neural network used, which, in this case, is necessarily the MLP network. Thus, the equation (

15) is nothing more than an iterative version of the back-propagation algorithm, which calculates the partial derivatives from the output of the MLP network, concerning its inputs and not concerning the synaptic weights.

It is also worth noticing that, to fully understand the equations from (

11) to (

14), it is convenient to consult the reference [

16], as it is necessary to make a temporal chain of several first-order Euler integrators, which work exclusively with mean derivative functions. This fact is because the horizon

m has, in general, temporal advances in an amount greater than the total number of delayed inputs of the E-TUNI used.

3.2. Correct Mathematical Demonstration of the E-TUNI General Expression

In this section, we formally demonstrate the general mathematical expression of E-TUNI, which is nothing more than a first-order Euler-type integrator working with mean derivative functions. This development is done here because, as previously stated, there is a demonstration error in the general E-TUNI expression presented in reference [

16]. So, the starting point is

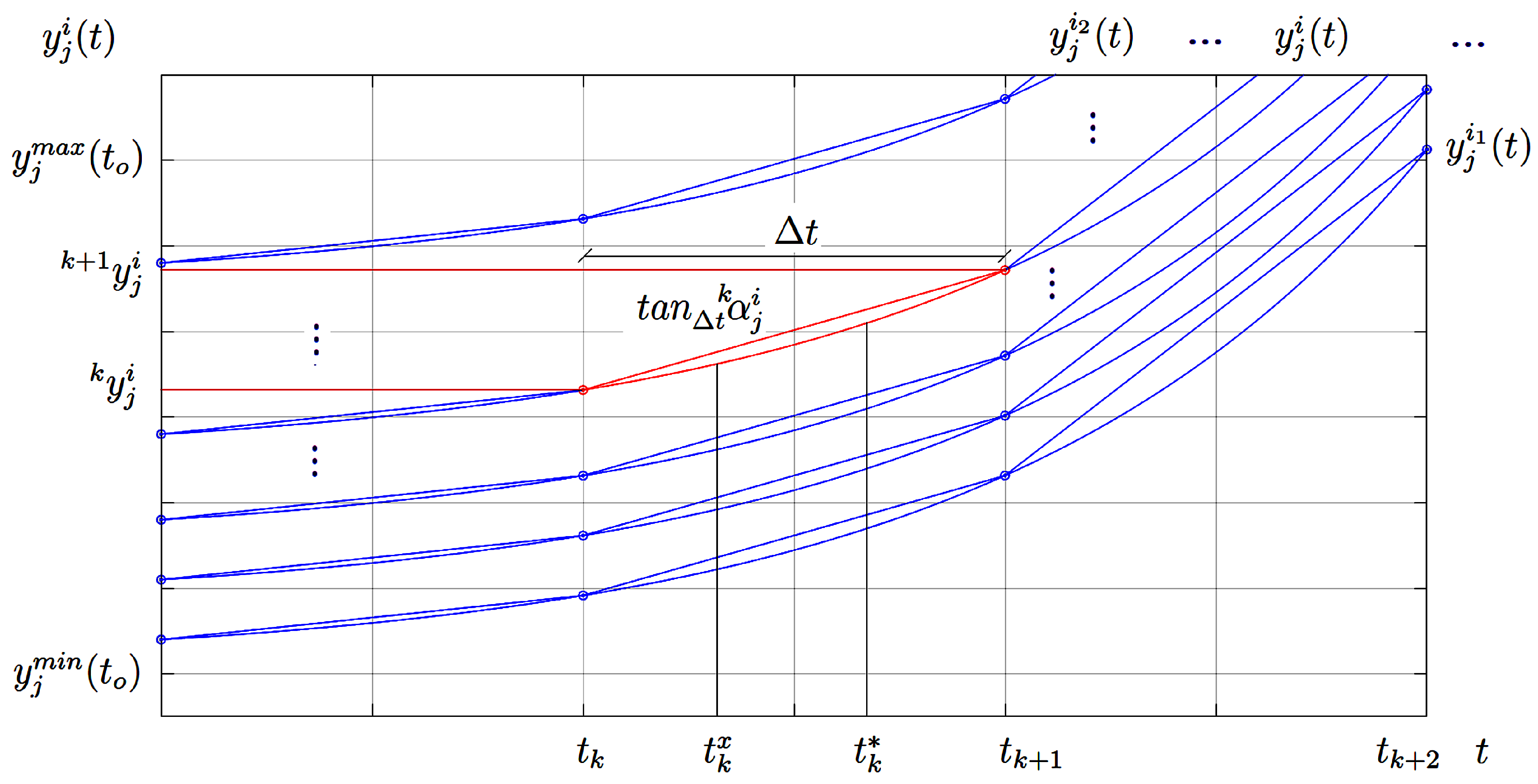

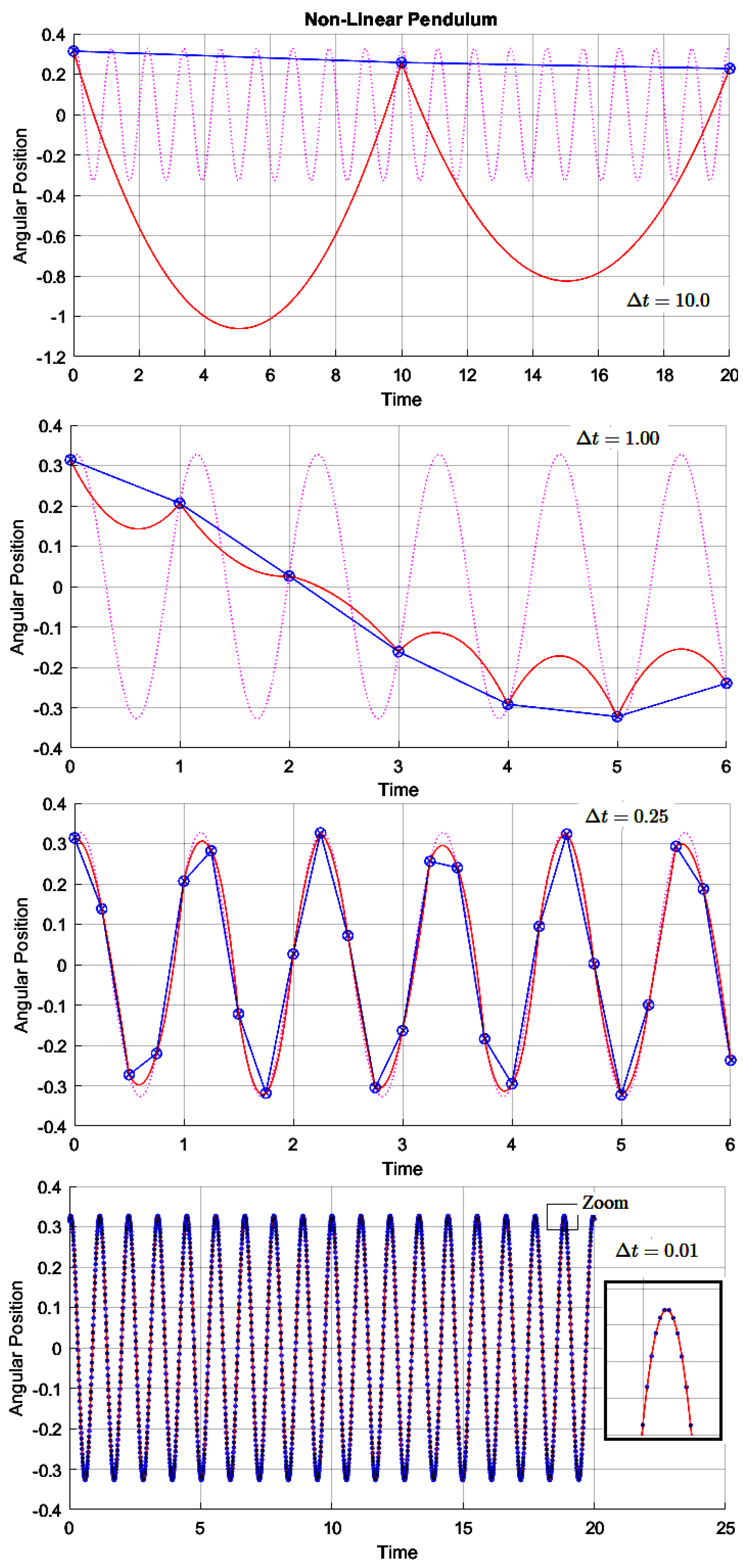

Figure 3.

So, for the reader to understand this figure, we explain it, starting from the point . The point is an instant of the solution of the considered autonomous dynamic system. The variable j means the jth state variable of the considered dynamic system, where , that is, there are a total of n state variables. The variable i represents the i-th curve of the family of curves confined in the interval and which is the solution of the considered dynamic system. By the continuum hypothesis, one can have infinite curves (). The variable k represents the k-th instant of time, that is, . In the case of the variable k, if the dynamical system solution does not come out of the region of interest [] and the system is autonomous then the variable k can also go to infinity (). Also, when we write or it means that and .

This notation for is sufficient to uniquely map it to its respective region of interest, where its associated secant characteristic is confined. So, in this case, for example, we can say that for the state we have its associated characteristic secant given by .

Thus, the secant is associated with the state variable with a curve i specific to the family of solutions, in this case, by and the instant . The fact that the secant is associated with the instant means that it is confined to the closed interval . Thus, the secant starts at and ends at .

Furthermore, the states

and

are special states, where both

and

are also confined to the closed interval

. The instants

as

are directly associated, respectively, with the integral mean value theorem and the differential mean value theorem [

25,

26]. So, having made these preliminary considerations, we begin now with this demonstration in a precise manner. Thus, let the following autonomous system of non-linear differential equations be given by,

Consider also, by definition,

for

a particular trajectory for a family of solutions to the system of differential equations

passing through

at instant

, i.e., initializing from a domain of interest

, where

and

are finite. It is also appropriate to introduce the following vector notation over (

16):

In [

25], by definition, the secant curve between two points

and

belonging to the curve

to

is the line segment joining these two points. Thus, the tangents of the secants between the points

and

,

and

, …,

and

are defined as:

with,

for

. Thus, we can state now the two fundamental theorems to consolidate our proof. These two theorems are the differential mean value theorem and the integral mean value theorem, which are presented below without proof [

25,

26].

Theorem 1 (The Differential Mean Value Theorem): If a function

for

is a continuous function and defined over the closed interval

is differentiable over the open interval

, then there is at least one number

with

such that,

Theorem 2 (The Integral Mean Value Theorem): If a function

for

is a continuous function and defined over the closed interval

, then there is at least one inner point

in

such that,

It is important to note that generally is different from . Also, the mean value theorems say nothing about how to determine the value of and . These two theorems simply state that and are confined to the closed interval .

Property 1: Applying Theorem 2 on the curve is equivalent to applying Theorem 1 on the curve both on the same interval closed , that is, .

Proof: from Theorem 2 applied to the continuous curve results in a for such that as a result of the fundamental theorem of calculus. Thus, . On the other hand, the application of Theorem 1 about the continuous and differentiable curve implies the existence of a for , such that . Thus, . However, this proof does not prove that . □

That said, we prove now the main theorem of this section, namely Theorem 3. But before that, it is worth commenting on some preliminary considerations. In Theorem 3 when we write

we are specifying that the general dynamical system

is harnessed to the particular solution of the curve

i belonging to the family of curves that is a solution of

. Thus,

is an alternative way of saying that the general dynamical system

is harnessed to some initial condition

. Thus, the notation with the index

i is more didactic to accept the uniqueness of the mapping explained at the beginning of this sub-section in

Figure 3. However, in this article, we did not prove the uniqueness of the mapping discussed in

Figure 3, but we assume it is true. To better understand this type of mapping, see a practical example of the same that appears in [

19] (see Fig. 7 in this same reference).

Another essential consideration for understanding the proof of Theorem 3 is that it is necessary to know the solution of the dynamic system beforehand, which can then be solved using the Euler integrator that works with mean derivative functions. Also, notice that, since we are working with supervised learning with input/output training patterns, this is not absurd. This fact is easy to understand, as it is necessary to know the references and to accurately estimate the mean derivative , between these two points, through a universal approximator of functions with exclusively feed-forward architecture.

Thus, if the solution of the non-linear dynamical system that is wanted to estimate, then it is necessary to treat this problem as n independent equations with only one time variable t each (black-box approach), rather than n vector coupled equations (white-box approach). This last statement can be justified with the help of Principle 1, which is proved, by reduction to absurdity, right after the proof of Theorem 3.

Therefore, if the solution of the considered dynamic system is previously known and given by for and then the function are easily obtained by direct differentiation (numerically or analytically). In this way, the original dynamic system can be replaced by for and , for a time interval confined in with the help of Principle 1.

However, it should be noted that the math function , in general, has nothing similar to the math function . Note also that this simplification makes it possible to reduce the proposed proof to a differential calculus of only one variable. Thus, it allows the use of the differential and integral mean value theorems. Note that must also have the over-index i, as this function must necessarily also depend on the initial condition as well as its equivalent instantaneous derivative function .

Theorem 3: The discrete and exact general solution for the autonomous system of non-linear ordinary differential equations of the type can be established through the first-order Euler relation of the type , for and fixed; since that the general solution of this dynamical system, given by, and are, previously, known for ; and t. Furthermore, the solutions for must all be continuous and differentiable. However, note that for is suffice to be continuous.

Proof: Let the autonomous non-linear dynamical system of first-order be given by

for

and

. If the dynamical system solution is known and equals to

then the function

can be replaced by

, that is,

. In this way, we can write that

. Note that the indices

i,

j, and

k uniquely map the secant that interests us according to

Figure 3. This last integral can still be simplified as

as a result of the fundamental theorem of calculus. So, applying the integral mean value theorem, in this last expression, we get

where

and for

. On the other hand, applying the differential mean value theorem on the function

for

in the interval

we get that

. So, by Property 1 we have that

to

. So,

to

or, in vector form, it turns out that

The reason that the functions for are all continuous and differentiable is that, in the proof of Theorem 3, we used the differential mean value theorem over and this theorem requires these two conditions to be applied. The reason that the functions for are all continuous is that, in the proof of the same Theorem 3, the integral mean value theorem was applied over the function and this theorem requires this condition. Note that for the application of the integral mean value theorem, the function is not required to be differentiable.

Principle 1: Given the non-linear autonomous dynamic system and their respective general solutions for and then, the autonomous instantaneous derivative functions can be replaced by the exclusively non-autonomous instantaneous derivative functions given by , that is, for and .

Proof: Assume, for absurdity, that the referred principle is false. If this is true, then there would be no compromise of veracity between the computational data acquisition system (through sensors) and the real universe, and thus the black-box approach would not work; but this is absurd. So, by exclusion, the principle is true . □

Notice that when a computational data acquisition system is performed, for example, from a particular real-world plant, something interesting happens. Thus, whoever maintains the consistency of the acquired data, through several sensors acting simultaneously and independently of each other, is the omnipresent and immutable manifestation of the natural physical laws, which govern the proper functioning of the universe (e.g., the law of universal gravitation, conservation of energy law, Faraday’s law, among others). In this case, little is allowed to human wisdom and technology.

Finally, the E-TUNI universal numerical integrator is suitable for solving only ordinary differential equations. However, it should be noted that the current use of neural networks in solving Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) is quite extensive [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Additionally, [

36] explains how to use the Runge-Kutta numerical integrator to solve partial differential equations (mainly hyperbolic ones). Therefore, using the E-TUNI to solve partial differential equations may be a good option for future work and should be investigated more carefully.