Submitted:

26 January 2023

Posted:

02 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

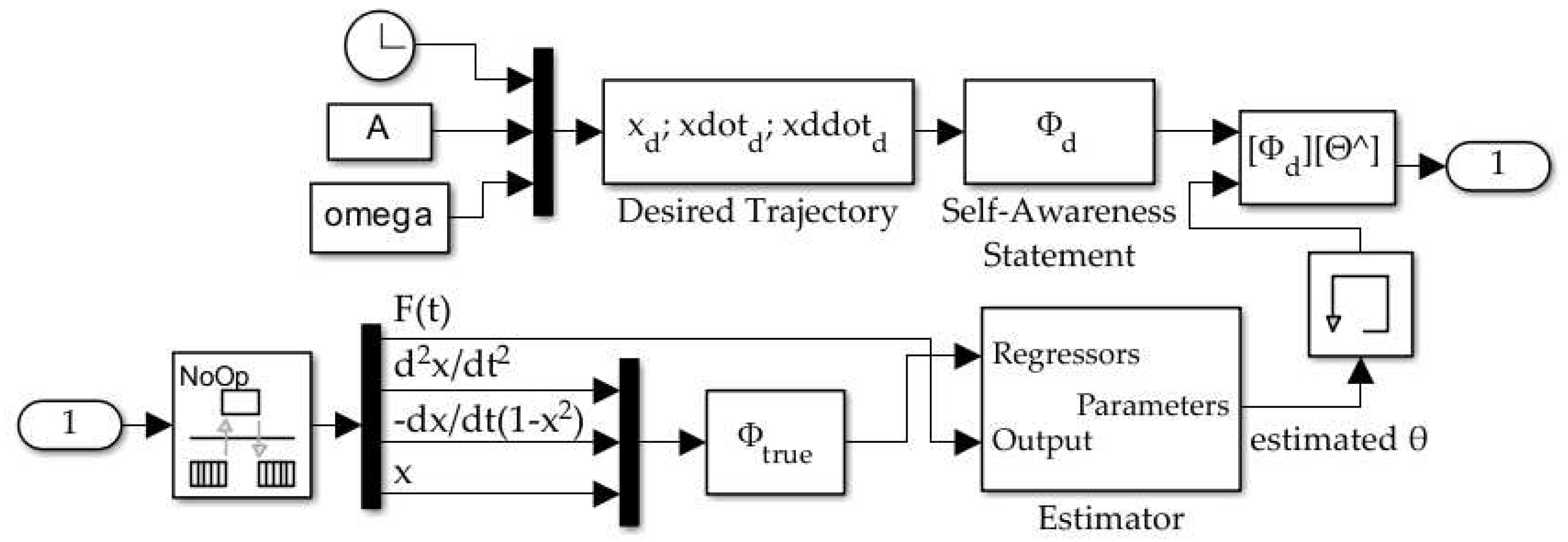

2. Materials and Methods

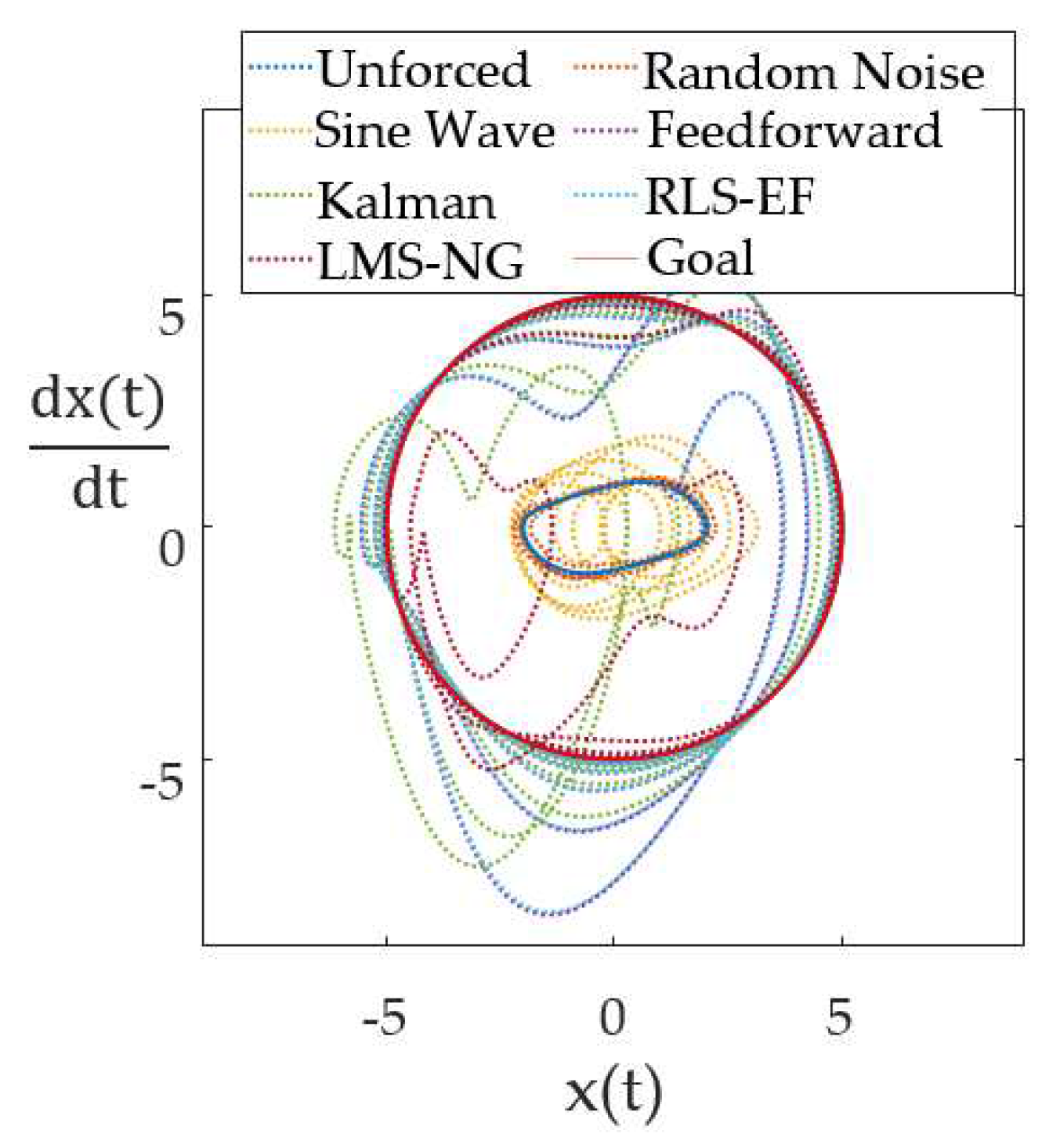

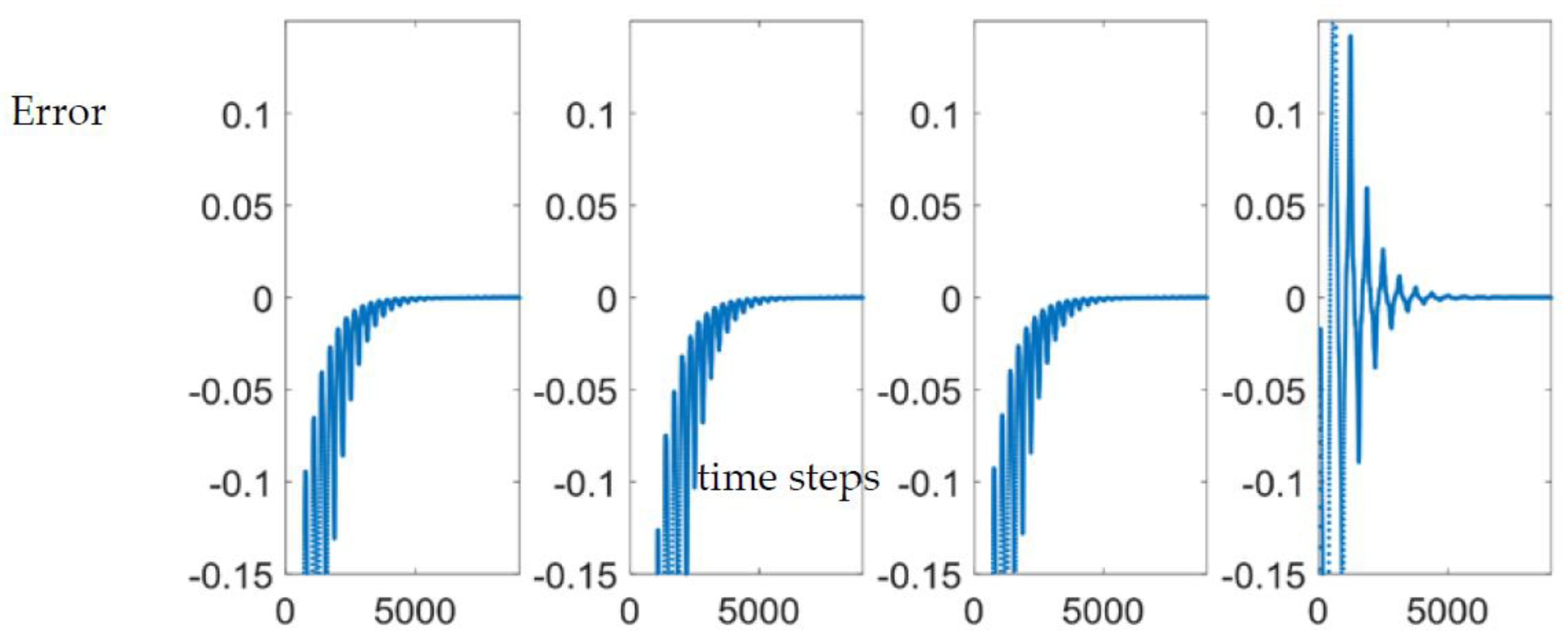

3. Results

- Unforced

- Uniform noise

- Sine wave

- Feedforward

- Deterministic artificial intelligence (DAI) – Kalman estimator

- Deterministic artificial intelligence (DAI) – RLS-EF estimator

- Deterministic artificial intelligence (DAI) – LMS-NG estimator

| Method | Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.3234 | 1 | 3.2031 |

| 2 | 3.3334 | 2 | 3.2110 |

| 3 | 3.9843 | 3 | 3.9275 |

| 4 | 0.2091 | 4 | 0.2284 |

| 5 | 0.4975 | 5 | 0.3927 |

| 6 | 0.2041 | 6 | 0.2237 |

| 7 | 0.3089 | 7 | 0.2877 |

| Method | Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.3218 | 1 | 3.1891 |

| 2 | 3.3262 | 2 | 3.1941 |

| 3 | 4.0150 | 3 | 3.9487 |

| 4 | 0.0642 | 4 | 0.0743 |

| 5 | 0.1220 | 5 | 0.1379 |

| 6 | 0.0629 | 6 | 0.0728 |

| 7 | 0.0329 | 7 | 0.0599 |

4. Discussion

Appendix A

References

- Rubinsztejn, Ari. Three double pendulums with near identical initial conditions diverge over time displaying the chaotic nature of the system. 2018. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e3/Demonstrating_Chaos_with_a_Double_Pendulum.gif/330px-Demonstrating_Chaos_with_a_Double_Pendulum.gif. (accessed on 22 12 2022).

- Cassady, J.; Maliga, K.; Overton, S.; Martin, T.; Sanders, S.; Joyner, C.; Kokam, T.; Tantardini, M. Next Steps in the Evolvable Path to Mars. In Proceedings of the International Astronautical Congress, Jerusalem, Israel, 12-16 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Li, Y. Li, C. Ott-Grebogi-Yorke controller design based on feedback control. 2011 International Conference on Electrical and Control Engineering, Yichang, China, 24 October 2011, pp. 4846-4849.

- Pyragas, K. Continuous control of chaos by self-controlling feedback. Physics Letters A 1992, 170(6), 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotine, J.; Li, W. Applied Nonlinear Control; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, U.S.A, 1991; pp. 392–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osburn, J.; Whitaker, H.; Kezer, A. New developments in the design of model reference adaptive control systems. Inst. Aero. Sci. 196161(39).

- Fossen, T. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control, 2 ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fossen, T. Guidance and Control of Ocean Vehicles; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, T.; Kim, J.; Agrawal, B. Spacecraft fine tracking pointing using adaptive control. Proceedings of 58th International Astronautical Congress, International Astronautical Federation: Paris, France, 24-28 September 2007.

- Sands, T.; Kim, J.; Agrawal, B. Spacecraft Adaptive Control Evaluation. Infotech@Aerospace, Garden Grove, California, 19 - 21 June 2012.

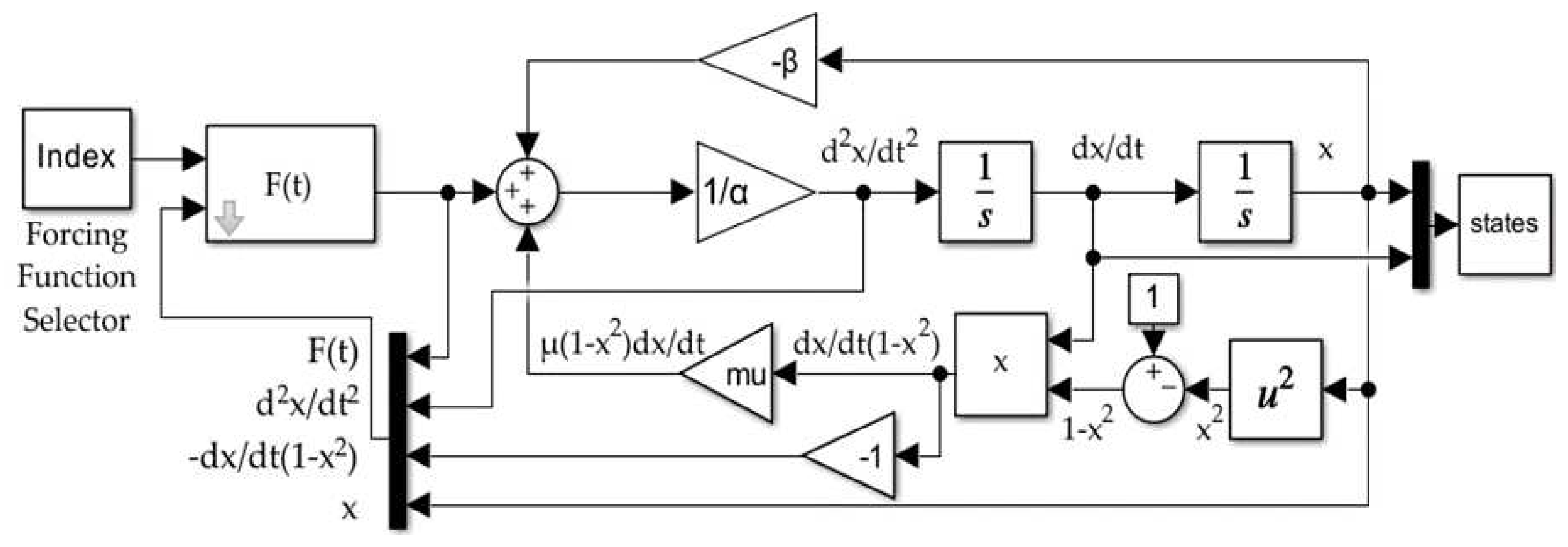

- Cooper, M.; Heidlauf, P.; Sands, T. Controlling Chaos—Forced van der Pol Equation. Mathematics 2017, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, B. A note on the relation of the audibility factor of a shunted telephone to the antenna circuit as used in the reception of wireless signals, Philosophical Magazine 1917, 34, 184–8. [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, B. On “Relaxation Oscillations”. I. Philos. Mag. 1926, 2, 978–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, B.; van der Mark, J. Frequency Demultiplication. Nature 1927, 120, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, B.; van der Mark, J. The heartbeat considered as a relaxation-oscillation, and an electrical model of the heart. Philosophical Magazine 1929, 6, 673–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, B. The nonlinear theory of electric oscillations. Proc. IRE 1934, 22, 1051–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

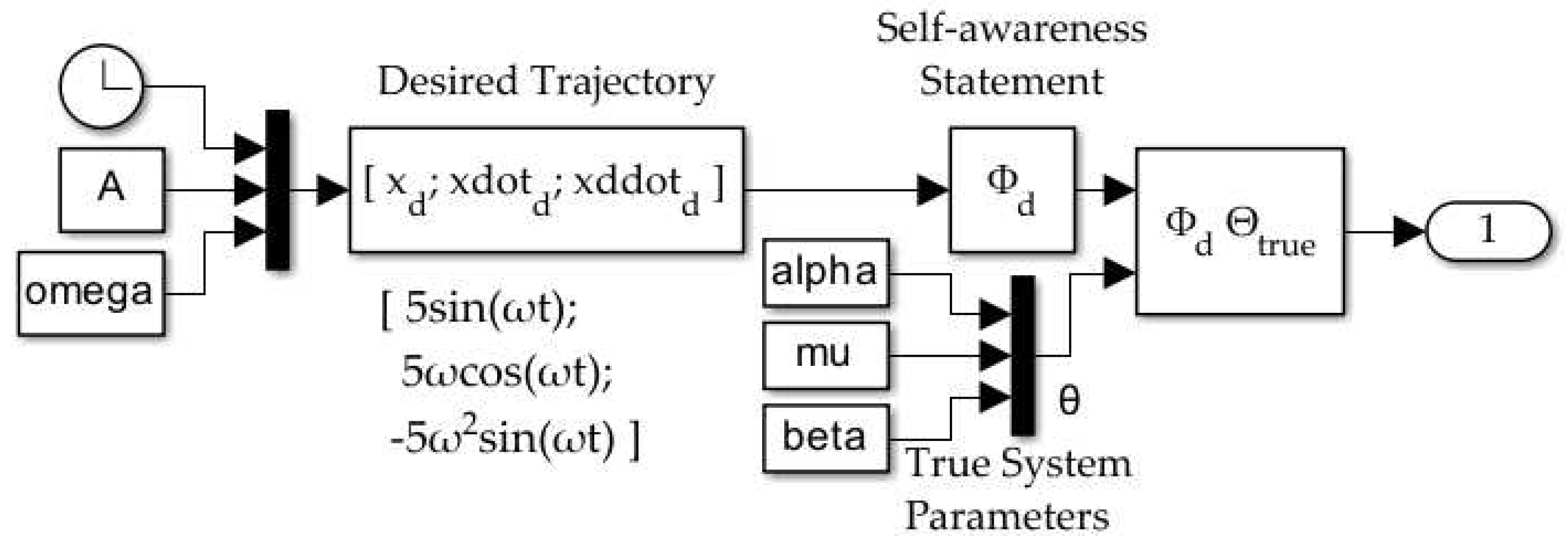

- Smeresky, B.; Rizzo, A.; Sands, T. Optimal Learning and Self-Awareness Versus PDI. Algorithms 2020, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, T. Development of Deterministic Artificial Intelligence for Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUV). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Sands, T. Controlling Chaos in Van Der Pol Dynamics Using Signal-Encoded Deep Learning. Mathematics 2022, 10, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Sands, T. Comparison of Deep Learning and Deterministic Algorithms for Control Modeling. Sensors 2022, 22, 6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plackett, R. ; Some Theorems in Least Squares. Biometrika 1950, 37, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astrom K., Wittenmark B. Adaptive Control. 2nd ed. Addison Wesley Longman: Massachusetts, USA; 1995.

- Patra, A.; Unbehauen, H. Nonlinear modeling and identification. In IEEE/SMC’93 Conference System Engineering in Service of Humans, Le Touquet, France, October 17-20, 1993.

| Method |

(% ± rel. method 4) |

(% ± rel. method 4) |

(% ± rel. method 4) |

(% ± rel. method 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feedforward Only (Method 4) | – | – | – | – |

| DAI with Kalman (Method 5) | -137.86 | -71.93 | -90.1 | -85.7 |

| DAI with RLS-EF (Method 6) | 2.41 | 2.04 | 1.97 | 1.93 |

| DAI with LMS-NG (Method 7) | -47.69 | -25.98 | 48.70 | 19.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).