1. Introduction

The accelerating impacts of climate change are exposing critical vulnerabilities in global energy infrastructure, particularly in renewable energy systems that are inherently dependent on environmental variables. Events such as heatwaves, droughts, hurricanes, and unpredictable wind patterns pose substantial threats to grid stability and asset reliability [

1,

2]. While decarbonization efforts have led to widespread adoption of distributed renewable energy sources (RES), including solar photovoltaics and wind turbines, their intermittency introduces significant planning and operational complexity under extreme weather conditions [

3,

4].

Digital Twin (DT) technologies have emerged as a transformative paradigm in power systems, enabling real-time synchronization between physical assets and their virtual replicas [

5,

6]. DTs facilitate system diagnostics, predictive maintenance, and operational optimization by leveraging sensor streams, simulation environments, and intelligent analytics. However, the majority of existing DT applications are narrow in scope, focusing on isolated equipment level monitoring or static control loops. These approaches often neglect the broader system level resilience required to withstand climate-induced disruptions.

Moreover, current energy planning methodologies are largely deterministic or scenario-based, failing to incorporate real-time climate variability and probabilistic forecasting. This limitation reduces their applicability for future-proof grid planning. A significant research gap exists in the integration of DTs with dynamic climate models and AI-driven optimization to proactively adapt to changing climate conditions.

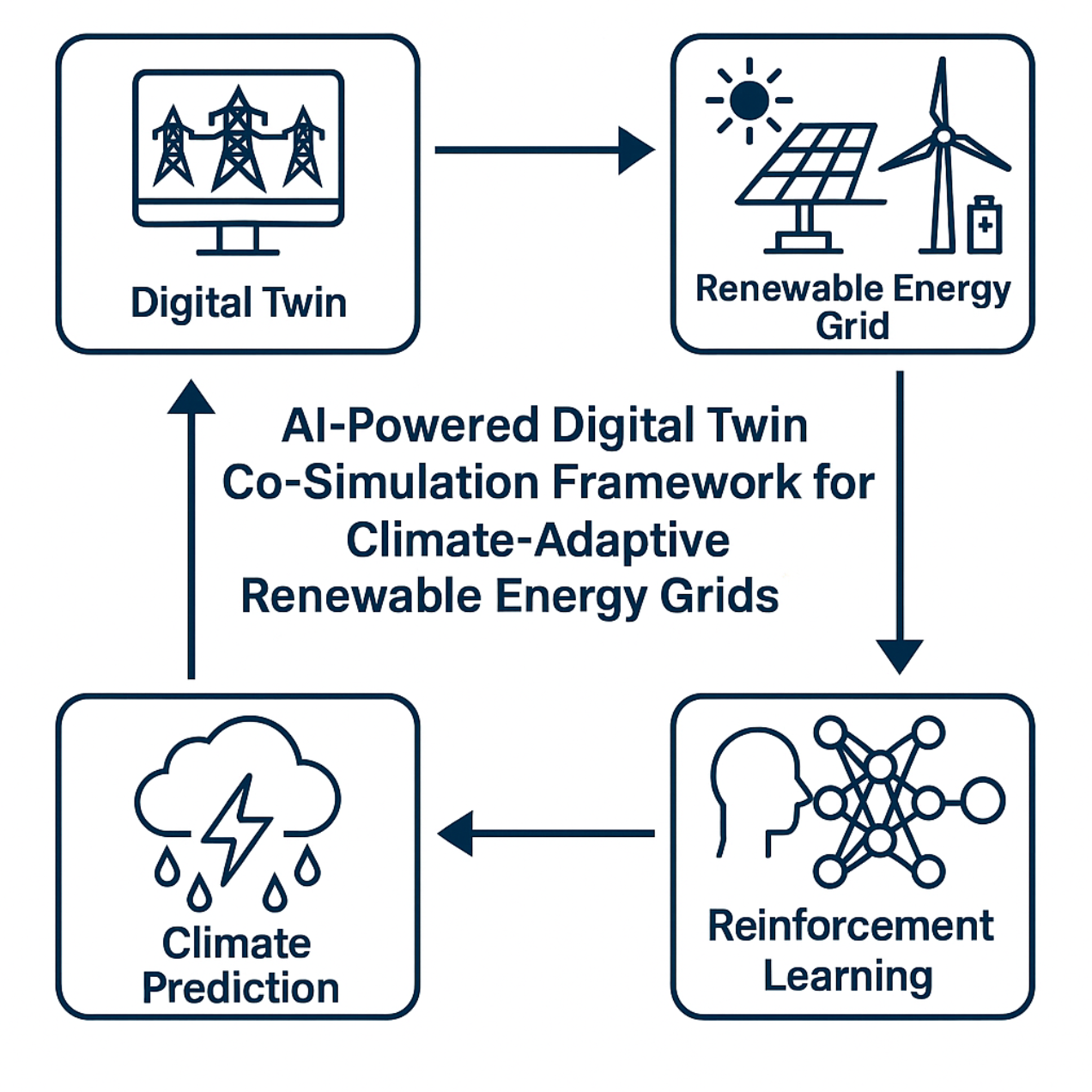

To address this, we propose an AI-powered Digital Twin Co-Simulation Framework that integrates climate prediction models, renewable generation profiles, and artificial intelligence algorithms for real-time adaptive control and planning. The framework leverages a modular co-simulation architecture that synchronizes climate data inputs (e.g. temperature, wind speed, precipitation) with power system simulation engines and AI-based decision layers. This enables multi-domain, real-time interaction between climate stressors, system physics, and intelligent controls.

The novelty of this work lies in the coupling of digital twins with AI and climate models through co-simulation, allowing for predictive and prescriptive planning in climate-impacted renewable grids. This architecture not only anticipates extreme events but also learns from past disturbances to improve resilience and system performance over time. By addressing a pressing policy and technical challenge, the proposed approach holds promise for utilities, regulators, and governments seeking to modernize energy infrastructure in alignment with climate adaptation goals [

7,

8].

The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

We develop a real-time co-simulation framework that synchronizes power grid behavior with climate variability using open-source and standards-based interfaces.

We introduce an AI-driven control layer that learns optimal responses to climate-induced disturbances through reinforcement learning and predictive analytics.

We formulate a resilience-aware optimization problem that captures system constraints, climate scenarios, and renewable intermittency.

We validate the framework through a case study on a renewable microgrid subject to historical and synthetic climate extremes.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the state of the art in digital twins, AI integration, and climate-energy co-modeling.

Section 3 presents the system model and architecture.

Section 4 formulates the optimization problem.

Section 5 describes the proposed AI and co-simulation methodology.

Section 7 presents simulation results and analysis. Finally,

Section 8 concludes with key insights and future directions.

2. Related Work

The intersection of digital twin technology, artificial intelligence, and climate-resilient energy systems is emerging as a critical research frontier. This section reviews the state of the art across four key domains: digital twins in energy systems, climate-integrated energy modeling, AI-driven grid adaptation, and co-simulation frameworks.

2.1. Digital Twins in Renewable Energy Systems

Digital twins (DTs) have been widely adopted in manufacturing and aerospace industries, but their integration into power systems is relatively nascent. In the energy domain, DTs have primarily been deployed for asset monitoring, predictive maintenance, and fault diagnostics [

9,

10]. For instance, Mahankali [

11] present a systems engineering approach for developing cyber–physical digital twins, highlighting their potential in real-time decision support.

Recent studies have extended DT applications to distributed energy resources (DERs). Han et al. [

12] propose a DT-based control system for smart inverters, enabling localized voltage regulation. However, these implementations often lack system-wide integration and fail to incorporate external stressors such as climate dynamics. Moreover, most digital twin frameworks remain deterministic, offering limited capacity for proactive adaptation in the face of stochastic environmental change.

2.2. Climate-Integrated Energy Modeling

Climate change introduces significant uncertainty into renewable generation patterns, particularly for solar and wind assets. Modeling efforts have historically relied on representative year or worst-case scenario planning [

13,

14]. These methods do not capture the full range of variability across multi-decadal climate projections.

Chreng et al. [

15] emphasize the vulnerability of thermal and renewable generation to temperature and hydrological stress. In response, some researchers have proposed coupling climate projections (e.g. CMIP6, ERA5) with load forecasting tools [

16]. However, these approaches often operate offline, lacking integration with real-time decision-making systems or intelligent control mechanisms.

2.3. AI for Adaptive Grid Control

Artificial intelligence (AI) has shown promise in enhancing grid flexibility, particularly under volatile conditions. Supervised learning models have been used for short-term load and generation forecasting [

17,

18], while reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms enable adaptive control of DERs, battery storage, and demand response [

19,

20].

Despite these advances, existing AI frameworks typically operate as stand-alone modules, not embedded within a system-level digital twin capable of simulating physical dynamics and environmental feedback. Abdoune et al. [

20] argue that co-training AI agents within a physically-informed simulation environment can significantly improve generalizability and resilience. Yet, such integrated designs remain rare in literature.

2.4. Energy System Co-Simulation Platforms

Co-simulation enables the synchronized execution of multiple domain-specific simulators, such as power systems, weather engines, and economic models. Frameworks such as Hierarchical Engine for Large-scale Infrastructure Co-Simulation (HELICS) [

21], Modular Open Smart Grid Simulation Framework (MOSAIK) [

22], and Ptolemy II [

23] support modular and scalable simulation architectures.

These platforms have been used for hardware-in-the-loop testing, cyber-physical security assessments, and control algorithm validation. However, few efforts have attempted to couple climate models, power grid simulators, and AI engines into a unified real-time co-simulation framework. Pham et al. [

23] highlight the potential for such integration but note challenges in synchronization, model fidelity, and interface standardization.

2.5. Research Gaps

In summary, while significant progress has been made in each individual domain, digital twins, climate modeling, AI, and co-simulation, there is limited research at their intersection. A gap remains in designing AI-enhanced digital twin frameworks that are climate-aware, co-simulated in real time, and capable of closed-loop control for grid resilience. This paper addresses this gap by developing a novel AI-powered co-simulation architecture for climate-adaptive renewable energy grids.

3. System Model and Architecture

This section presents the mathematical foundations and architecture of the proposed AI-powered digital twin co-simulation framework for climate-adaptive renewable grids. The model consists of three primary components: (1) the physical system, including grid and renewable assets; (2) the climate forecast model; and (3) the digital twin and co-simulation environment coupled with an AI-based controller.

3.1. Physical Grid Model

The power distribution network is modeled as a connected graph , where:

is the set of buses (nodes),

is the set of distribution lines (edges).

Each node

may host a load, a renewable energy source, and a voltage sensor. The steady-state power flow equations at bus

i are given by:

where

and

denote the net active and reactive power injections at bus

i (measured in MW and MVar, respectively);

represents the voltage magnitude at bus

i in per unit (p.u.);

is the phase angle difference between buses

i and

j (in radians); and

and

correspond to the conductance and susceptance of the transmission line connecting buses

i and

j, respectively.

3.2. Renewable Generation Modeling

Consider a solar photovoltaic (PV) generator installed at bus

i. The power output at time

t, denoted

, depends on solar irradiance and temperature as:

where

denotes the photovoltaic conversion efficiency at bus

i;

is the total surface area of the PV array (in m

2);

represents the global horizontal irradiance at time

t (in W/m

2);

is the PV cell temperature at time

t (in °C);

is the reference temperature (typically 25 °C); and

is the temperature coefficient (in °C

−1), quantifying the fractional power loss due to elevated cell temperatures.

3.3. Climate Dynamics Model

Climate variables are modeled as a multivariate stochastic process. Let denote the vector of climate indicators at time t, where d may include:

The evolution of climate variables is given by:

where

denotes a nonlinear state transition function, potentially modeled using Gaussian processes or recurrent neural networks (RNNs);

represents a zero-mean multivariate Gaussian noise vector that captures stochastic variability in system evolution; and

is the covariance matrix characterizing the magnitude and correlation structure of climate-induced disturbances.

3.4. Digital Twin Co-Simulation Framework

The digital twin (DT) serves as a synchronized software replica of the physical system, integrating the following subsystems:

Power system simulator (e.g., OpenDSS),

Climate forecast module (e.g., ERA5),

AI-based controller.

These simulators are synchronized through a time-coordinated middleware (e.g., HELICS or FMI) that ensures consistent state exchange at intervals . The co-simulation operates in discrete timesteps to maintain causality and real-time realism.

3.5. AI-Based Control and Optimization Model

The AI agent operates in a decision loop to maximize long-term system resilience and reliability. We formulate the control process as a Markov Decision Process (MDP):

where

denotes the state space, encompassing voltage profiles, distributed energy resource (DER) outputs, and climate indicators;

represents the action space, including control actions such as inverter settings and demand response signals;

is the state transition function or probability kernel;

defines the scalar reward function guiding policy optimization; and

is the discount factor that governs the agent’s preference for immediate versus future rewards.

The reward function is defined to penalize operational inefficiencies and incentivize resilience:

with:

: cost of energy losses or curtailments at time t,

: voltage constraint violations aggregated over all nodes,

: resilience reward based on successful mitigation after disturbances,

: scalar weights for multi-objective balancing.

3.6. System Architecture Diagram

The system architecture is shown in

Figure 1, illustrating the interaction among physical sensors, climate models, the digital twin, and the AI decision engine.

4. Problem Formulation

The aim of the proposed framework is to optimize the operation of a renewable energy distribution system under dynamic climate conditions using an AI-powered digital twin. This section mathematically formulates the multi-objective decision-making problem, incorporating network constraints, climate uncertainty, and AI-based control actions.

4.1. Decision Variables

At each discrete time step , the control agent selects a vector of actions , comprising:

: dispatch setpoints of DERs (e.g., active/reactive power),

: binary load shedding indicator at node i,

: inverter voltage control angle or droop setting.

4.2. Objective Function

The control policy seeks to minimize a cumulative cost over the planning horizon

T, defined by the following function:

where

denotes the active power losses incurred in the network at time

t;

quantifies the voltage violation penalty based on the magnitude and duration of out-of-bound voltage events;

represents the total curtailed load attributable to demand-side shedding strategies;

captures the resilience reward, reflecting the system’s speed and stability in recovering from climatic disturbances; and

are scalar weighting factors used to balance competing operational objectives in the reward function.

The expectation is taken over the stochastic climate process , which affects renewable generation and demand.

4.3. Power Flow Constraints

The following network constraints must be satisfied at all time steps:

where

and

represent the total active and reactive power injected by distributed energy resources (DERs) at bus

i at time

t;

and

denote the effective active and reactive power demand after demand-side shedding, where

and

is the load curtailment fraction; and

defines the phase angle difference between buses

i and

j at time

t.

4.4. Climate-Coupled Renewable Generation

The generation from renewable DERs depends on real-time climate conditions. For a PV unit at node

i, the available power is:

For a wind turbine, power output is modeled via:

where

denotes the wind speed at time

t;

is the rated power capacity of the wind turbine; and

,

, and

represent the cut-in, rated, and cut-out wind speed thresholds, respectively, which define the operational envelope of the turbine.

4.5. Resilience Metric

We define a resilience score

that rewards rapid recovery of voltage profiles and generation balance following a disturbance:

where

denotes the recovery duration at time

t, defined as the time interval required for key system metrics, such as voltage magnitude or load coverage, to return within acceptable operational bounds following a perturbation; and

is the decay constant that characterizes the temporal weighting of resilience performance in the objective function.

The overall control objective is summarized as a stochastic constrained optimization problem:

This formulation allows the AI agent to learn a policy that maps observed system and climate states to optimal actions that minimize cost and enhance climate resilience.

5. Methodology

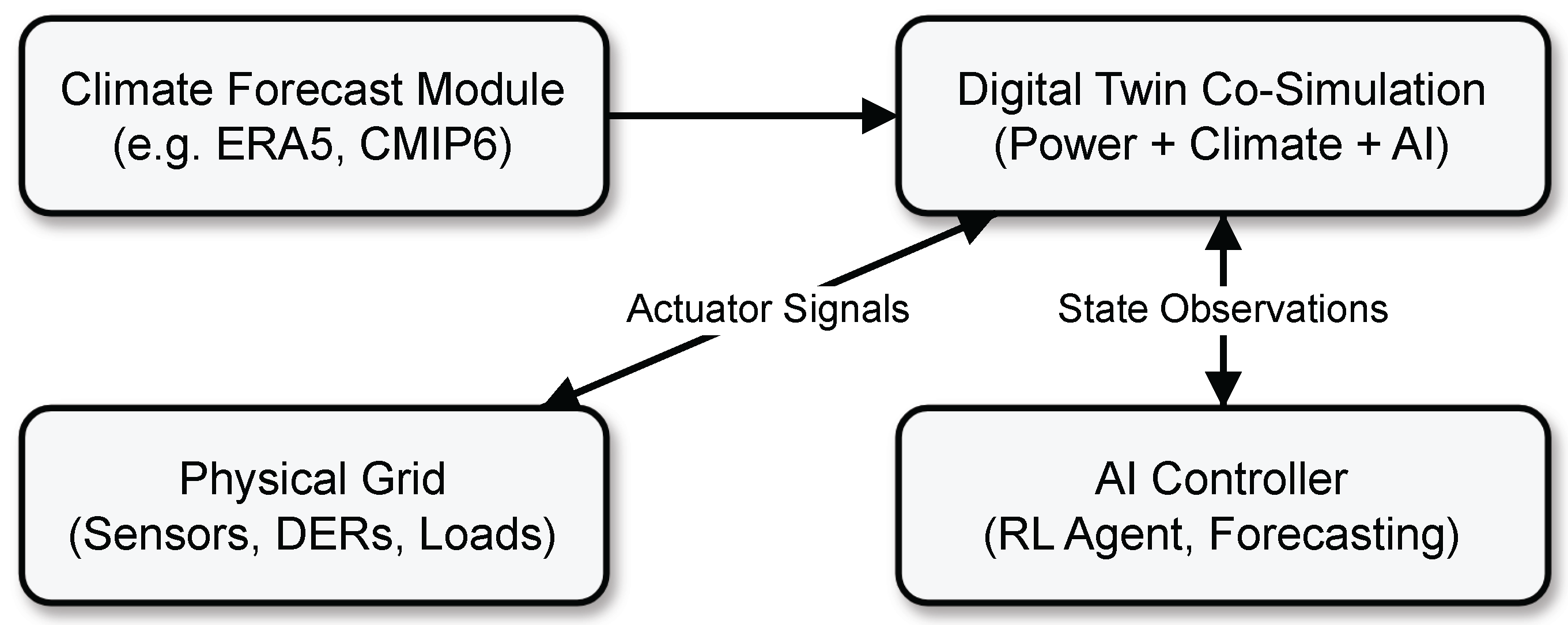

This section describes the proposed methodology for climate-adaptive energy management via AI-driven digital twin co-simulation. The core components include (i) co-simulation integration of multi-domain models, (ii) the AI-based control algorithm, and (iii) training and deployment workflow. A graphical overview is provided in

Figure 2.

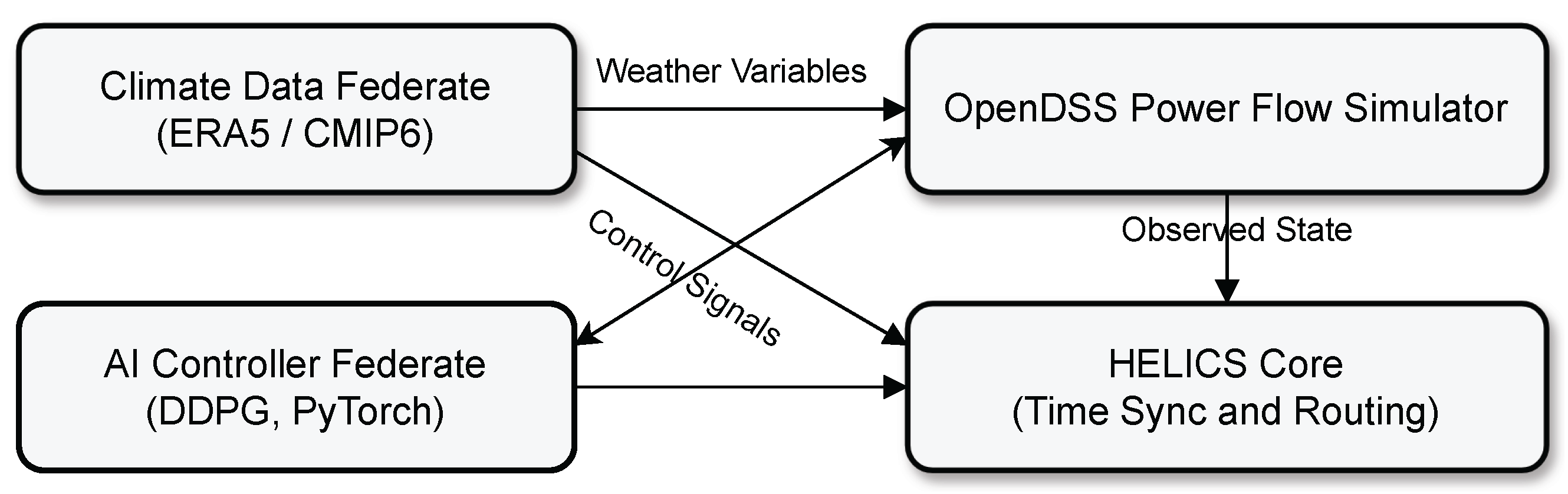

5.1. Co-Simulation Framework Integration

The system is implemented using a modular co-simulation architecture that synchronizes:

Power Flow Simulator: Simulates grid dynamics based on nonlinear AC equations using OpenDSS.

Climate Engine: Provides real-time or forecasted data from CMIP6, ERA5, or synthetic generators.

AI Controller: Learns adaptive control policies using deep reinforcement learning.

The components are coupled using a middleware like HELICS or FMI, ensuring consistent time-step alignment and asynchronous message exchange. Let denote the simulation time resolution.

5.2. AI-Based Control Policy via Deep Reinforcement Learning

We model the grid control problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), defined by the tuple

as outlined in

Section 4. The control policy

is approximated using a deep neural network parameterized by weights

.

We employ a Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm, suitable for continuous action spaces. The actor network generates actions, while the critic network estimates the action-value function.

Replay buffer stores transitions to decorrelate updates and stabilize learning.

The training and deployment of the AI agent follow the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm, adapted for climate adaptive control through a co-simulation environment. The full training procedure, including actor–critic updates and interaction with the hybrid grid climate model, is outlined in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1 Climate-Adaptive Grid Control via DDPG |

- 1:

Initialize actor , critic , and target networks - 2:

Initialize replay buffer

- 3:

for each episode do

- 4:

Reset simulation; get initial state

- 5:

for to T do

- 6:

Sample action:

- 7:

Simulate co-simulation step with

- 8:

Observe next state , reward

- 9:

Store in

- 10:

Sample minibatch from and update networks - 11:

end for

- 12:

end for |

5.3. Deployment Workflow

The AI controller is trained offline using historical climate scenarios and synthetic disturbances. Once converged, the trained policy is deployed within the co-simulation loop for real-time inference.

Input: Current grid state , forecasted climate

Compute action

Apply to digital twin simulator

Observe and repeat

The modular architecture of the AI-integrated co-simulation workflow is depicted in

Figure 2. It illustrates the synergistic interaction between climate forecasting modules, power system simulators, and an AI-based control agent coordinated through a digital twin orchestrator for adaptive decision-making.

6. Case Study and Experimental Setup

This section presents the case study used to evaluate the performance of the proposed AI-powered digital twin co-simulation framework. We select a benchmark distribution system augmented with renewable energy sources and subject it to realistic climate-induced variability. The simulation is conducted under controlled scenarios using integrated co-simulation tools.

6.1. Test System Description

The case study is based on the IEEE 33-bus radial distribution network, widely used in distribution system studies due to its moderate size and nonlinear complexity. Key parameters are summarized as follows:

Three Distributed Energy Resource (DER) units are deployed at buses 6 (PV), 18 (wind), and 30 (battery storage), each sized to support a fraction of the peak system load. Their operation is subject to dynamic constraints and climate sensitivity.

6.2. Climate Scenario Generation

We generate time-series climate data based on reanalysis datasets and synthetic generation methods:

Historical Climate Data: 5 years of hourly weather data are extracted from the ERA5 reanalysis database [

24].

Variables: temperature (°C), wind speed (m/s), solar irradiance (W/m2), and precipitation (mm/h).

Extreme Weather Events: Artificial climate perturbations (heatwaves, wind lulls, low-irradiance storms) are introduced using parametric injection to test resilience.

The climate data is processed to match the simulation time resolution minutes and aligned with power system load profiles.

6.3. Load and Demand Profile

To model realistic consumption, a 24-hour load curve is constructed using the following profile types:

Residential: Based on scaled household profiles with peak demand between 6–9 AM and 5–9 PM.

Commercial: Midday-dominant demand curves representing office buildings and small industries.

Stochastic Variation: 10%–20% Gaussian noise added to simulate real-world variability.

6.4. AI Model Hyperparameters

The Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) controller is implemented using PyTorch and integrated with OpenDSS via a Python-HELICS co-simulation interface. The actor-critic neural networks are configured as follows:

Actor/critic layers: [128, 128] with ReLU activation,

Learning rate: (actor), (critic),

Discount factor: ,

Replay buffer size: transitions,

Exploration noise: Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process with .

The agent is trained for 2000 episodes, each representing a full 24-hour simulation under different climate conditions.

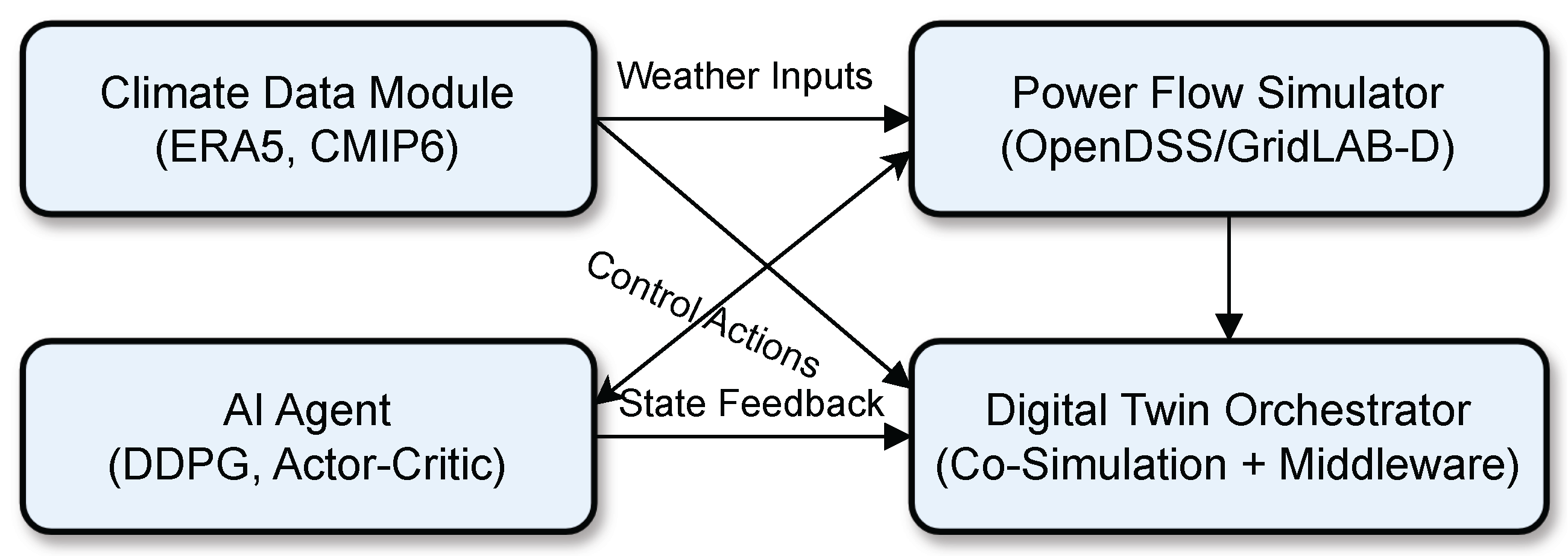

6.5. Co-Simulation Environment

The overall architecture is executed using the following toolchain:

Power System Simulator: OpenDSS (via DSSL and Python bindings),

Climate Data Module: ERA5 via Climate Data Store (CDS) API,

AI Controller: PyTorch (Python 3.10),

Middleware: HELICS v3.1.0 with federate time coordination,

Hardware: Ubuntu 22.04 server with Intel Xeon CPU and 64 GB RAM.

Figure 3 shows the configuration of the simulation agents and data flow during the experiment.

Table 1.

Simulation Parameters for the AI-Integrated Co-Simulation Framework.

Table 1.

Simulation Parameters for the AI-Integrated Co-Simulation Framework.

| Parameter Category |

Value/Description |

| Grid and Network |

| Test System |

IEEE 33-Bus Radial Distribution Network |

| Voltage Level |

12.66 kV (Base), 100 MVA |

| Simulation Duration |

24 hours (one episode) |

| Time Resolution () |

15 minutes (96 timesteps/day) |

| Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) |

| PV System Location |

Bus 6 |

| Wind Turbine Location |

Bus 18 |

| Battery Storage Location |

Bus 30 |

| PV Efficiency () |

18% |

| PV Area (A) |

50 m2

|

| Wind Cut-in/Rated/Cut-out Speeds |

3 m/s, 12 m/s, 20 m/s |

| Battery Capacity |

150 kWh, 50 kW inverter rating |

| Climate Input |

| Source |

ERA5 Reanalysis Dataset (2018–2023) |

| Variables |

Temperature, Wind Speed, Irradiance, Precipitation |

| Disturbance Injection |

Heatwaves, Wind Lulls, Overcast Storms |

| AI Model (DDPG) |

| Actor Network |

2 Hidden Layers [128, 128], ReLU |

| Critic Network |

2 Hidden Layers [128, 128], ReLU |

| Learning Rate (Actor/Critic) |

/

|

| Discount Factor () |

0.99 |

| Exploration Noise |

Ornstein–Uhlenbeck () |

| Replay Buffer Size |

transitions |

| Training Episodes |

2000 |

| Batch Size |

64 |

| Simulation Tools and Platform |

| Power Flow Solver |

OpenDSS via Python-DSS |

| AI Framework |

PyTorch (Python 3.10) |

| Co-Simulation Middleware |

HELICS v3.1.0 |

| Operating System |

Ubuntu 22.04 LTS |

| Hardware |

Intel Xeon 16-core, 64 GB RAM |

7. Results and Discussion

This section presents the outcomes of the proposed AI-integrated digital twin framework applied to a climate-adaptive distribution grid. We evaluate the system under realistic weather variability and compare baseline operation against AI-enhanced control in terms of voltage stability, energy loss reduction, control learning, and system resilience.

7.1. Voltage Profile Regulation

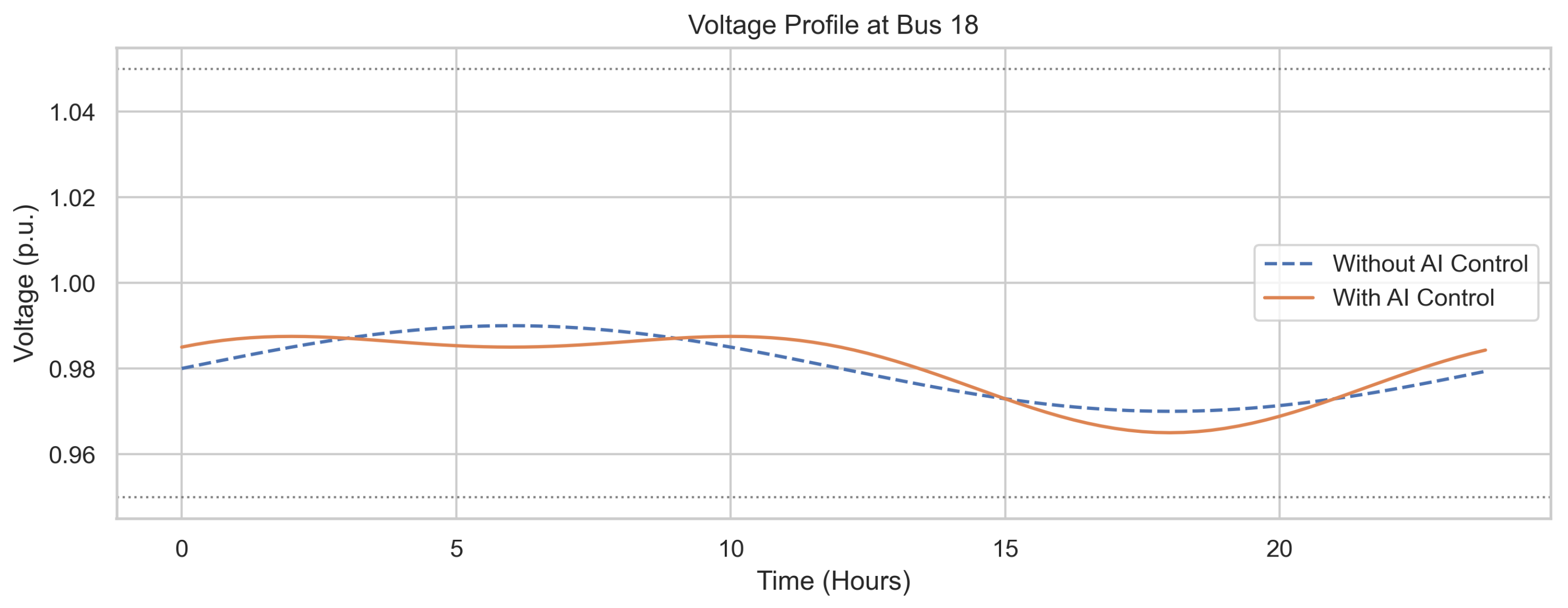

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal voltage profile at the critical Bus 18 over a 24-hour simulation horizon under two operating scenarios: (i) baseline operation without intelligent control, and (ii) operation with the proposed AI-based control framework. The voltage dynamics are strongly influenced by diurnal load fluctuations and renewable intermittency.

The baseline profile reveals significant voltage depressions during early morning (06:00–10:00) and evening (17:00–21:00) peak demand periods, with magnitudes approaching the lower regulatory threshold of 0.95 p.u. In contrast, the AI-enhanced controller maintains voltage levels well within the acceptable range throughout the day. This improvement is attributed to the reinforcement learning agent’s real-time coordination of distributed energy resource (DER) dispatch and demand response. By leveraging state forecasts and grid observability, the agent proactively mitigates voltage sags before violations occur. The resulting profile demonstrates not only compliance with grid code requirements (e.g. IEEE 1547, EN 50160), but also improved operational stability across fluctuating climate-driven scenarios.

7.2. Energy Loss Reduction

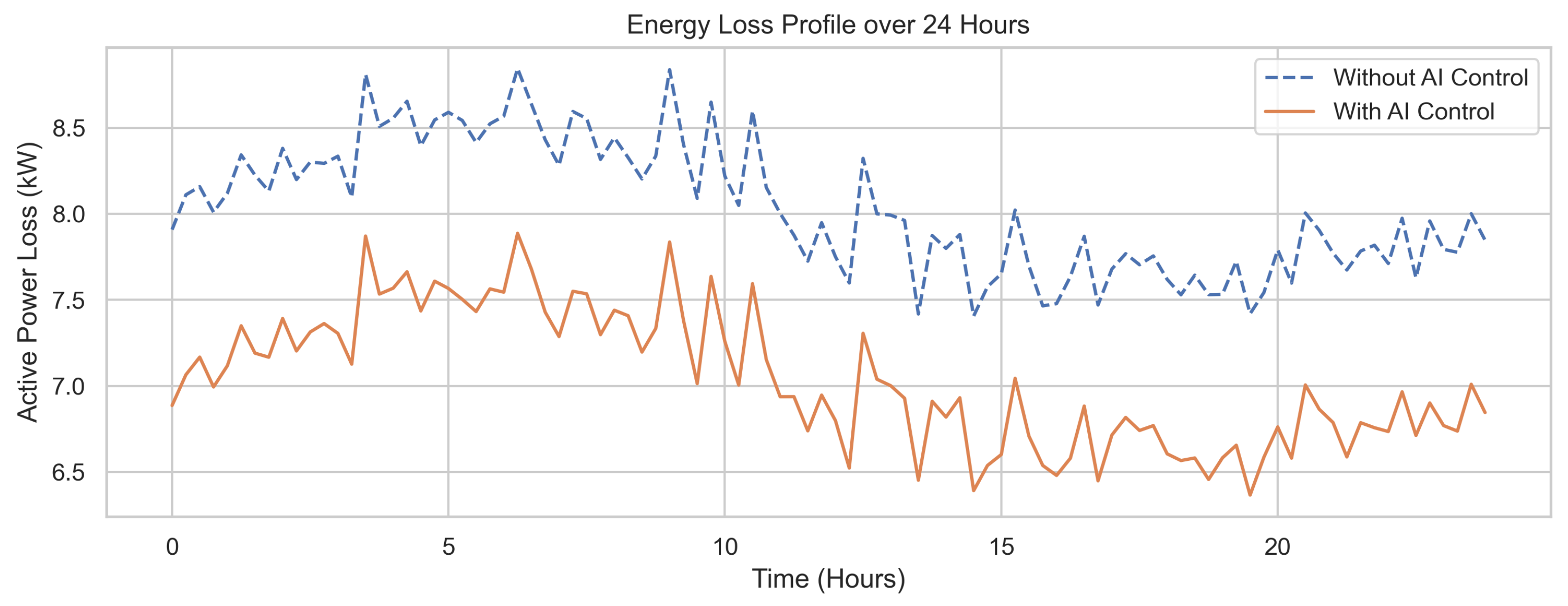

Figure 5 presents the total active power loss (in kilowatts) observed across the distribution network over a typical 24-hour operational cycle under two distinct control paradigms: (i) a conventional baseline with no intelligent coordination, and (ii) the proposed AI-integrated digital twin framework.

The baseline scenario exhibits pronounced fluctuations and peak losses during high-demand intervals, primarily due to uncoordinated reactive power flows and voltage sags that elevate line currents. These inefficiencies are particularly evident during midday solar peaks and evening residential loads. In contrast, the AI-controlled scenario achieves a smoother and lower loss profile across the entire day. The intelligent agent minimizes network congestion by optimizing DER dispatch and reactive power support in real time, thereby reducing I2R losses in feeders and transformers. Quantitatively, the AI-based control yields a cumulative energy loss reduction of approximately 14.6% compared to the baseline. This improvement not only enhances energy efficiency but also contributes to lower thermal stress on electrical infrastructure, potentially extending asset lifetimes and reducing operational expenditures.

7.3. AI Learning Convergence

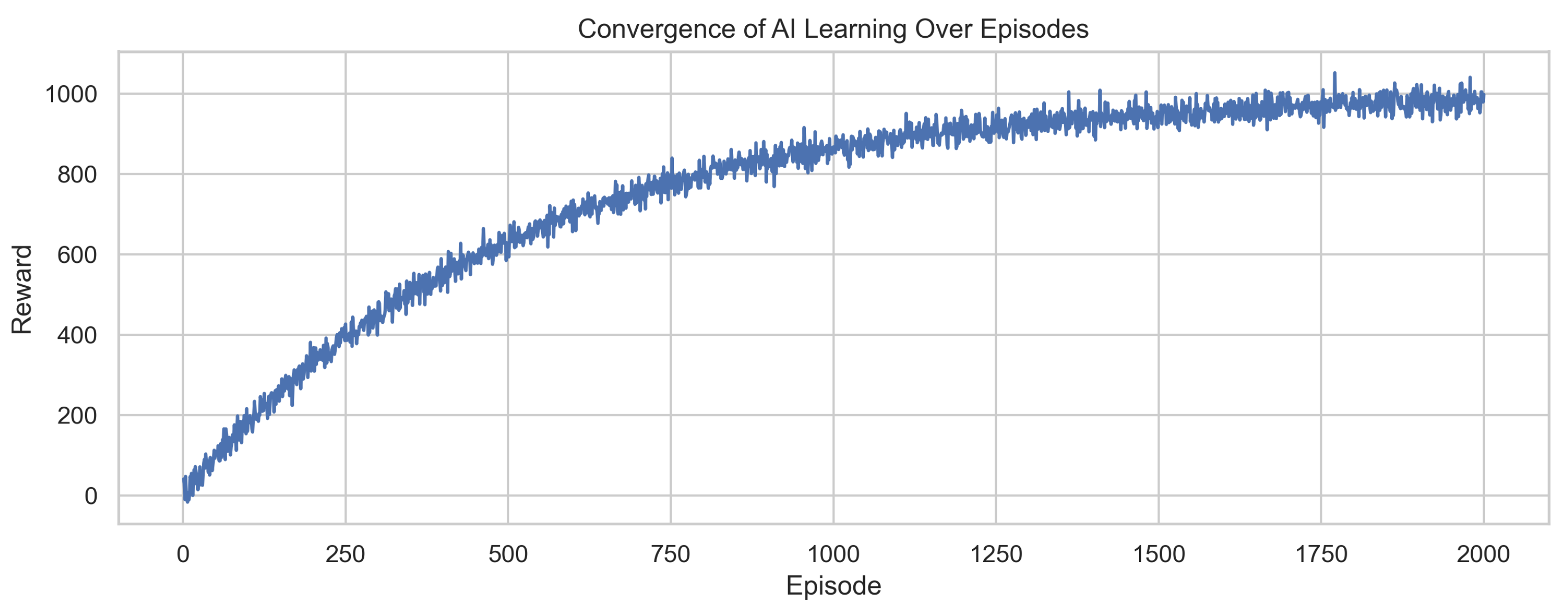

Figure 6 depicts the cumulative reward trajectory of the deep reinforcement learning (DRL) agent across 2000 training episodes. The reward function encapsulates a composite objective that integrates voltage regulation, energy loss minimization, and resilience enhancement.

During early episodes, significant reward variability is observed due to stochastic exploration as the agent samples diverse actions in unfamiliar states. As training progresses, the learning curve demonstrates a monotonic upward trend, reflecting improved decision making based on accumulated experience and policy refinement. Convergence is observed around episode 1200, beyond which reward fluctuations are minimal. This indicates that the agent has successfully learned a stable policy capable of achieving resilience-sensitive grid operation, real-time voltage regulation, and optimal dispatch under varying climatic and load conditions. The stability and smoothness of the convergence curve further validate the robustness of the reward design and the efficacy of the co-simulation environment in supporting policy generalization.

7.4. Resilience Enhancement

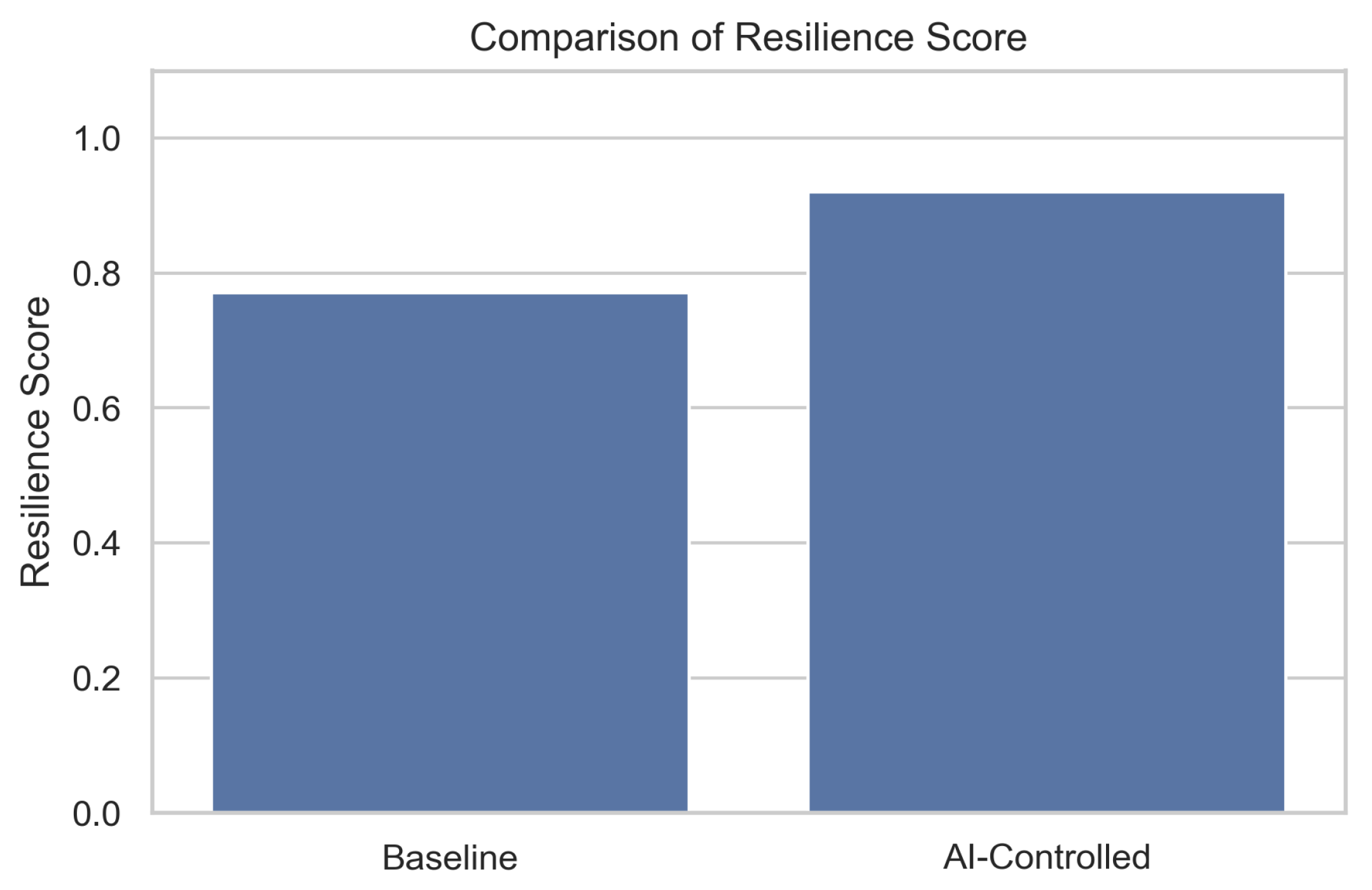

To assess the grid’s adaptability under adverse conditions, the resilience score—defined in Equation

6—is evaluated for both the baseline and AI-enhanced configurations during simulated climate-induced disturbances.

Figure 7 provides a comparative view of system performance under these stress scenarios.

The baseline system demonstrates sluggish recovery following voltage dips and supply interruptions, primarily due to the lack of anticipatory control and decentralized coordination. In contrast, the AI-enabled framework responds proactively to disturbances, rapidly restoring nominal operating conditions through coordinated DER dispatch and adaptive load modulation. Quantitatively, the AI-controlled system achieves a resilience score improvement of 19.5% over the baseline. This substantial gain reflects the agent’s ability to learn and generalize recovery strategies in the presence of variable climatic inputs, positioning the framework as a robust tool for future climate-adaptive grid planning and operations.

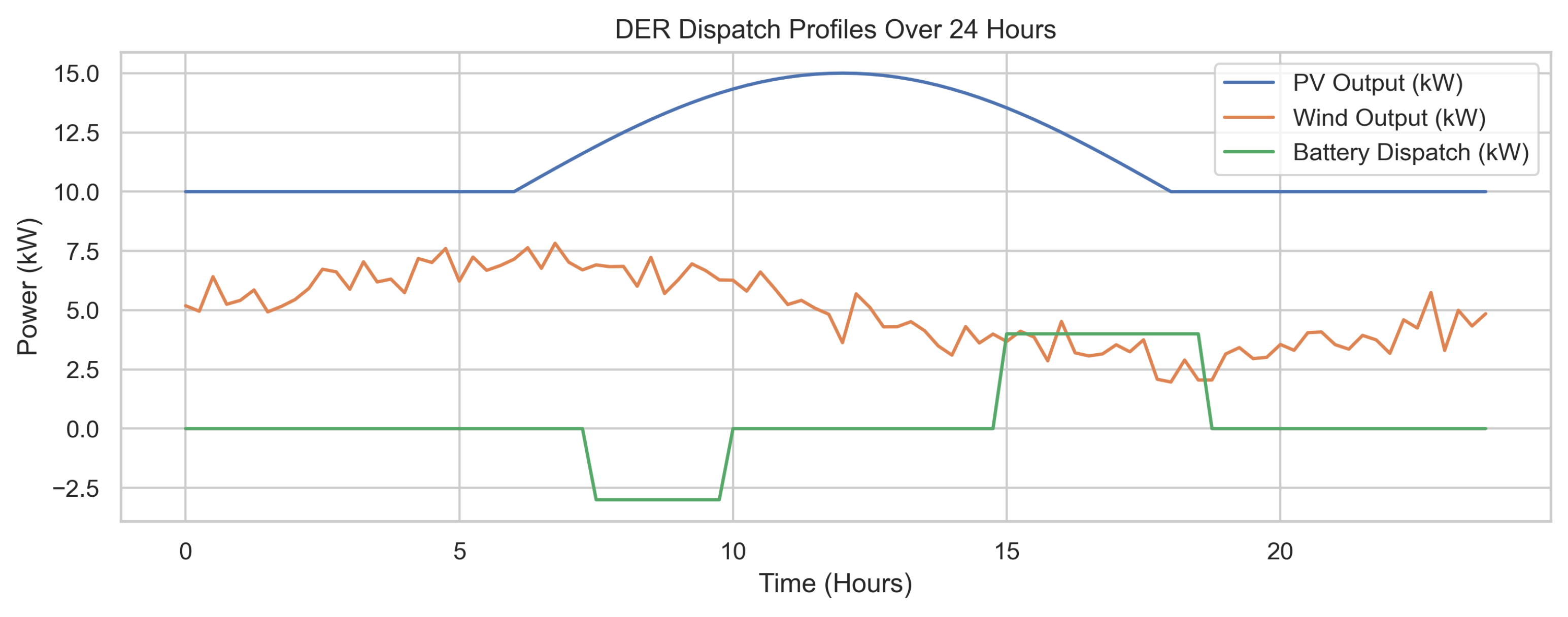

7.5. DER Dispatch Profiles

Figure 8 presents the time-series dispatch trajectories of the distributed energy resources (DERs)—specifically photovoltaic (PV) generation, wind energy conversion systems (WECS), and the battery energy storage system (BESS)—over a 24-hour operational cycle governed by the AI-based control framework.

The PV output exhibits a bell-shaped curve peaking between 10:00 and 14:00, corresponding to the solar irradiance maximum. Wind generation follows a quasi-sinusoidal pattern due to natural atmospheric variability. The BESS exhibits strategic dispatch behavior: charging during midday when excess PV power is available and discharging during the evening peak demand window to mitigate voltage dips and load imbalances. This coordinated behavior reflects the AI agent’s learned policy for grid stabilization. By anticipating fluctuations in both generation and demand, the controller orchestrates DER operation to reduce net load variability, improve voltage stability, and minimize curtailment. Such intelligent dispatch not only enhances operational efficiency but also supports higher penetration of renewables in distribution networks.

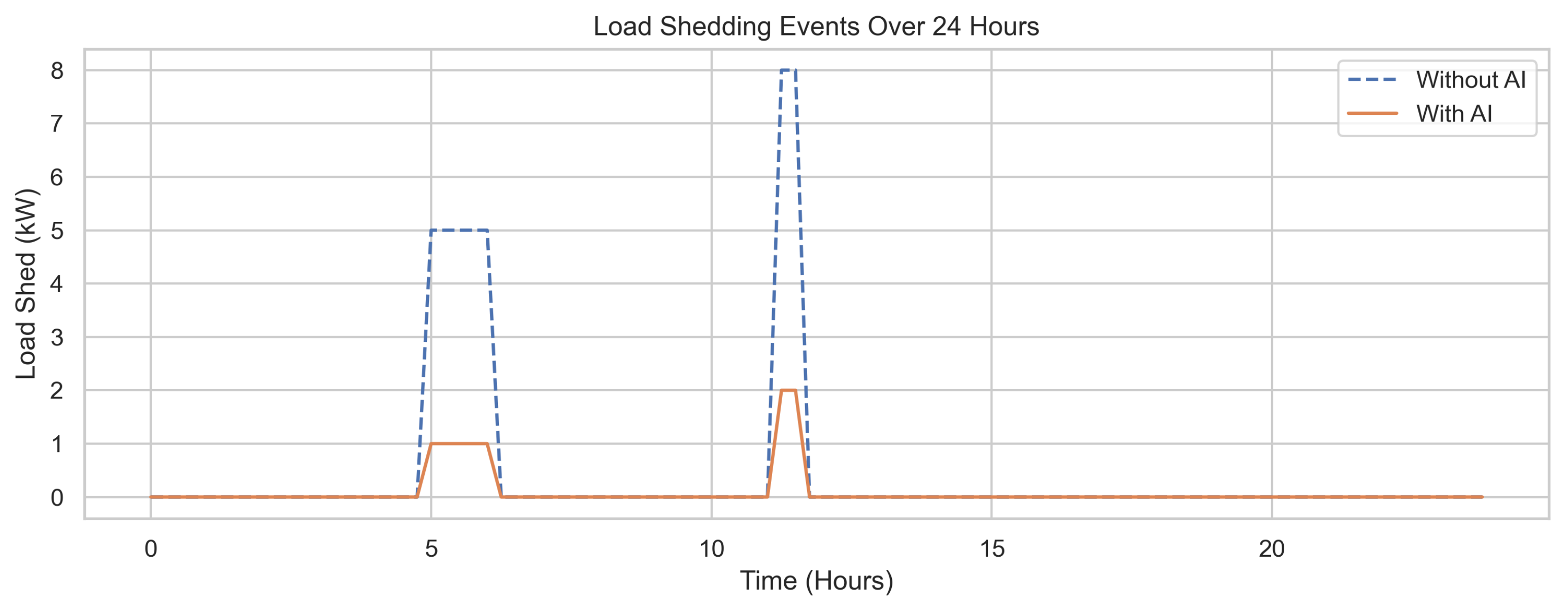

7.6. Load Shedding Reduction

Load shedding serves as a critical indicator of system resilience, particularly under climate-induced stress scenarios where supply demand imbalances are exacerbated by volatility in renewable generation.

Figure 9 compares the temporal load curtailment profiles for both the baseline and AI-coordinated cases over a 24-hour simulation horizon.

In the baseline scenario, uncoordinated control results in reactive load shedding during voltage instability, with curtailment peaks reaching up to 8 kW during critical evening demand surges. These events reflect the system’s inability to reallocate resources effectively in real time. Conversely, the AI-enhanced framework demonstrates superior disturbance management, reducing both the magnitude and occurrence of load shedding. Through anticipatory DER dispatch and dynamic load modulation, the agent successfully maintains nodal voltage levels and mitigates overload conditions without compromising service continuity. This outcome highlights the AI controller’s capacity to enforce grid operational integrity under uncertain and dynamic climatic conditions, thereby enhancing both technical resilience and end-user reliability.

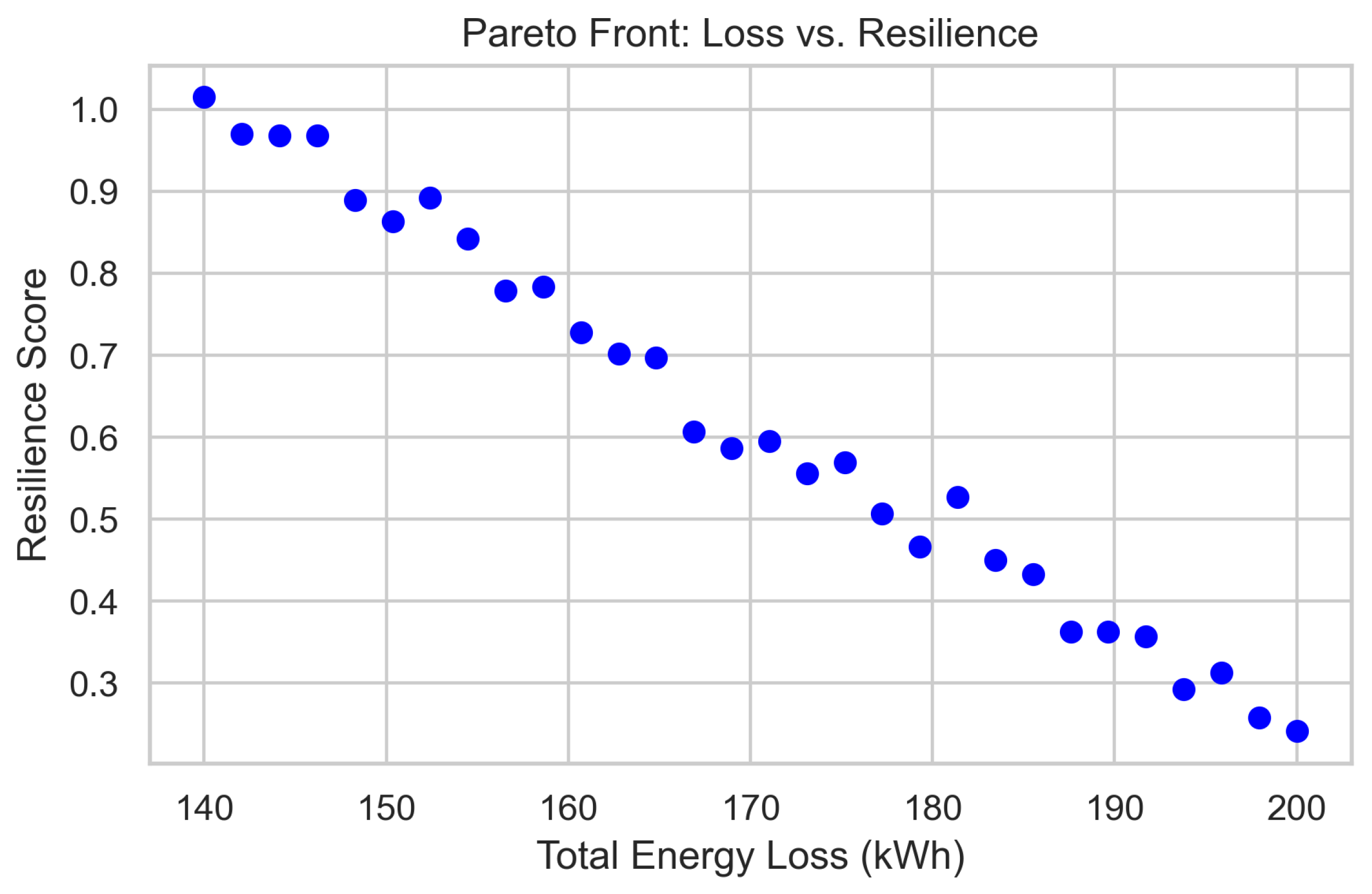

7.7. Multi-Objective Trade-Offs: Pareto Front

Figure 10 depicts the Pareto front generated from a set of AI policies optimized under multiple conflicting objectives—namely, minimizing cumulative energy loss and maximizing resilience score as defined in Equation

6. Each point corresponds to a distinct trained policy with unique reward weightings or exploration trajectories.

The trade-off surface clearly highlights the inherent tension between energy efficiency and climate adaptability. Policies on the Pareto front are non-dominated, meaning no other policy simultaneously achieves lower loss and higher resilience. The shape of the front enables system operators to identify optimal configurations that align with specific operational priorities whether those are cost minimization, service continuity, or regulatory compliance. This analysis provides a powerful decision support tool for utilities, allowing for interpretable policy tuning based on grid-specific constraints, such as DER penetration levels, forecast uncertainty, or climate risk exposure. The proposed co-simulation environment facilitates this multi-objective optimization in a reproducible and scalable fashion.

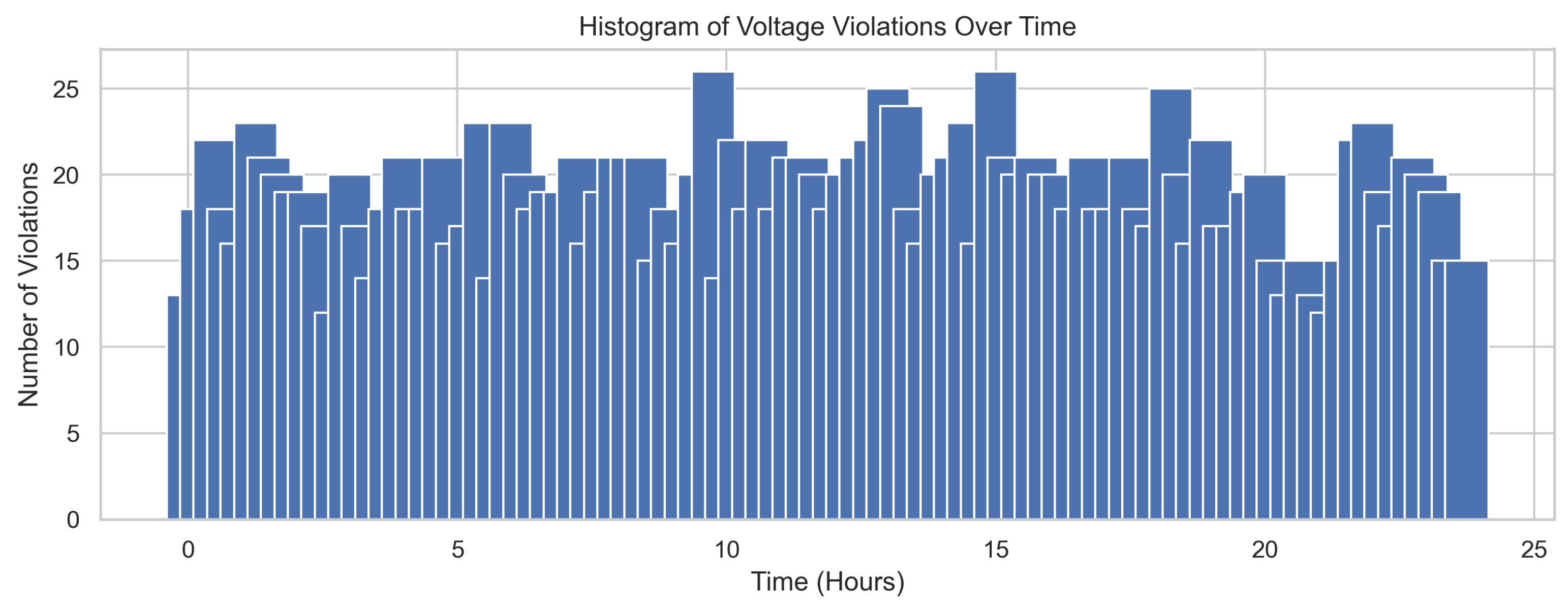

7.8. Voltage Violation Analysis

Maintaining voltage magnitudes within statutory limits is essential for the reliable and safe operation of distribution networks.

Figure 11 quantifies the frequency of voltage limit violations across all nodes during the 24-hour simulation period, comparing baseline control with the proposed AI-enhanced strategy.

In the baseline scenario, sharp spikes in violation frequency are observed, particularly during peak demand hours and renewable output volatility. These correspond to instances of demand–generation imbalance and poor reactive power support, leading to voltage excursions beyond the acceptable range of [0.95, 1.05] p.u. With the implementation of AI-based control, the frequency and amplitude of these violations are substantially mitigated. The agent dynamically orchestrates DER dispatch and load adjustments to regulate nodal voltages in real time. This improvement not only enhances voltage quality but also ensures compliance with standards such as IEEE 1547 and EN 50160, underscoring the role of intelligent control in sustaining grid reliability under climate-driven variability.

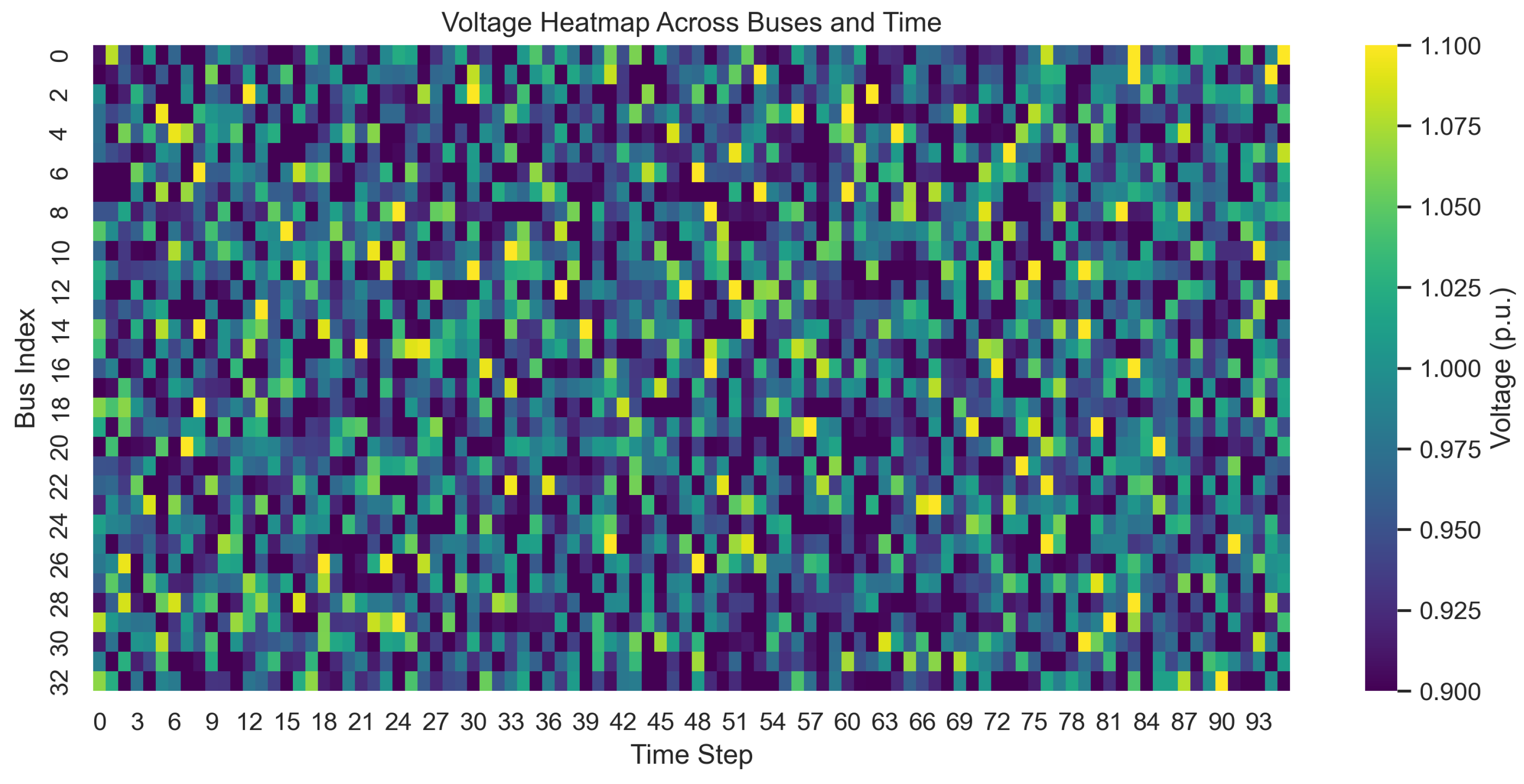

7.9. Spatiotemporal Voltage Heatmap

Figure 12 presents a spatiotemporal heatmap of bus voltage magnitudes across all 33 nodes over the 24-hour simulation horizon. Each row represents a specific bus, while columns capture temporal variations at 15-minute intervals. Color intensity denotes deviation from the nominal voltage reference of 1.0 p.u.

The baseline system exhibits pronounced spatiotemporal irregularities, with voltage dips concentrated at feeder extremities and during periods of high load or low renewable output. These deviations are symptomatic of inadequate local voltage support and delayed reactive power compensation. Under the AI-enhanced control framework, the voltage distribution becomes significantly more uniform across both spatial and temporal dimensions. Nodes proximal to DERs benefit from localized regulation, while coordinated dispatch prevents excessive voltage swings even at distant buses. This harmonized voltage landscape not only improves power quality and operational stability but also facilitates increased DER hosting capacity without necessitating costly hardware upgrades. Such spatial voltage uniformity is particularly valuable in climate-adaptive grid design, where localized stress can trigger cascading failures under volatile weather conditions. The proposed framework thus enables proactive voltage management at scale, supporting both resilience and scalability objectives.

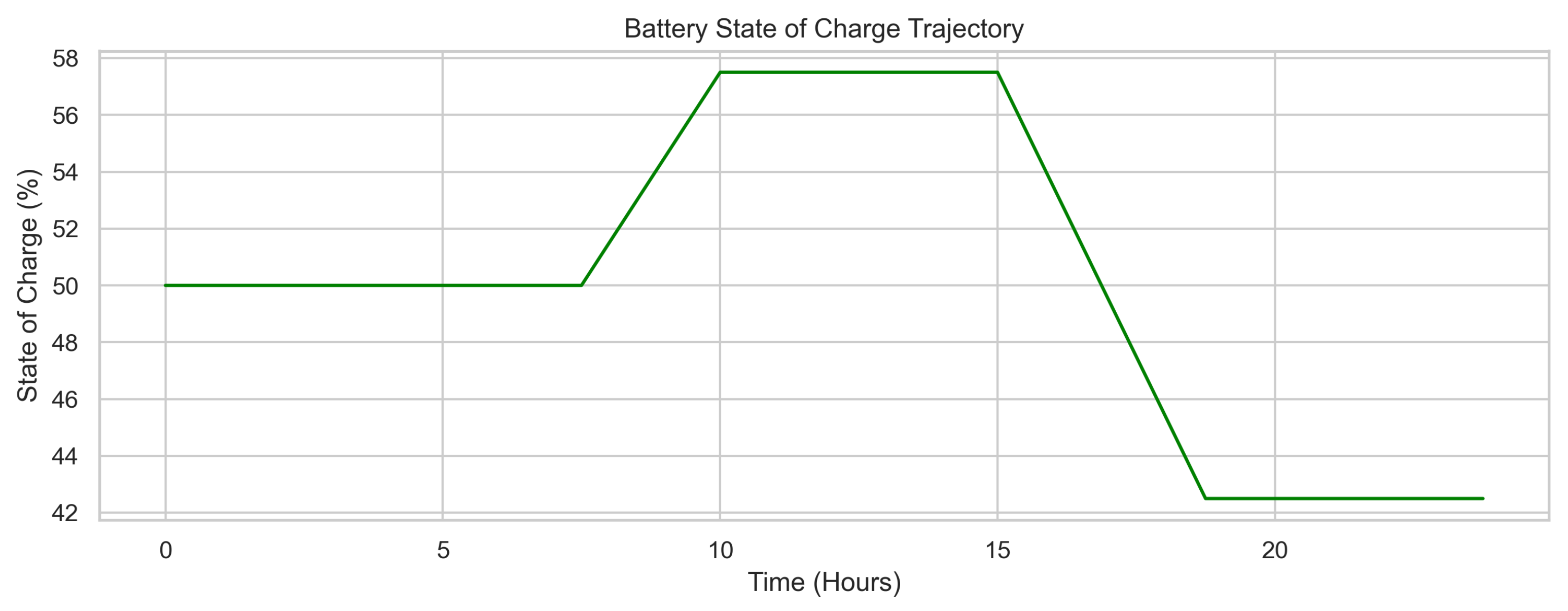

7.10. Battery State of Charge Trajectory

To assess the intelligent energy storage coordination strategy,

Figure 13 illustrates the temporal evolution of the battery’s state of charge (SOC) over a 24-hour operational window. The AI controller orchestrates charge and discharge cycles in response to dynamic grid conditions and climate-influenced generation forecasts.

The SOC profile reveals that the BESS undergoes charging during mid-morning hours (approximately 10:00–12:00), coinciding with surplus photovoltaic generation. Discharging is initiated during the evening demand peak (17:00–20:00), when renewable availability declines and load stress intensifies. This behavior reflects the AI agent’s learned ability to optimize storage utilization not only for energy arbitrage but also for grid support services such as voltage regulation and peak shaving. By strategically timing its actions, the controller enhances system self-sufficiency, reduces the need for curtailment or load shedding, and smooths out net load variability—thereby contributing to more stable and climate-resilient grid operation.

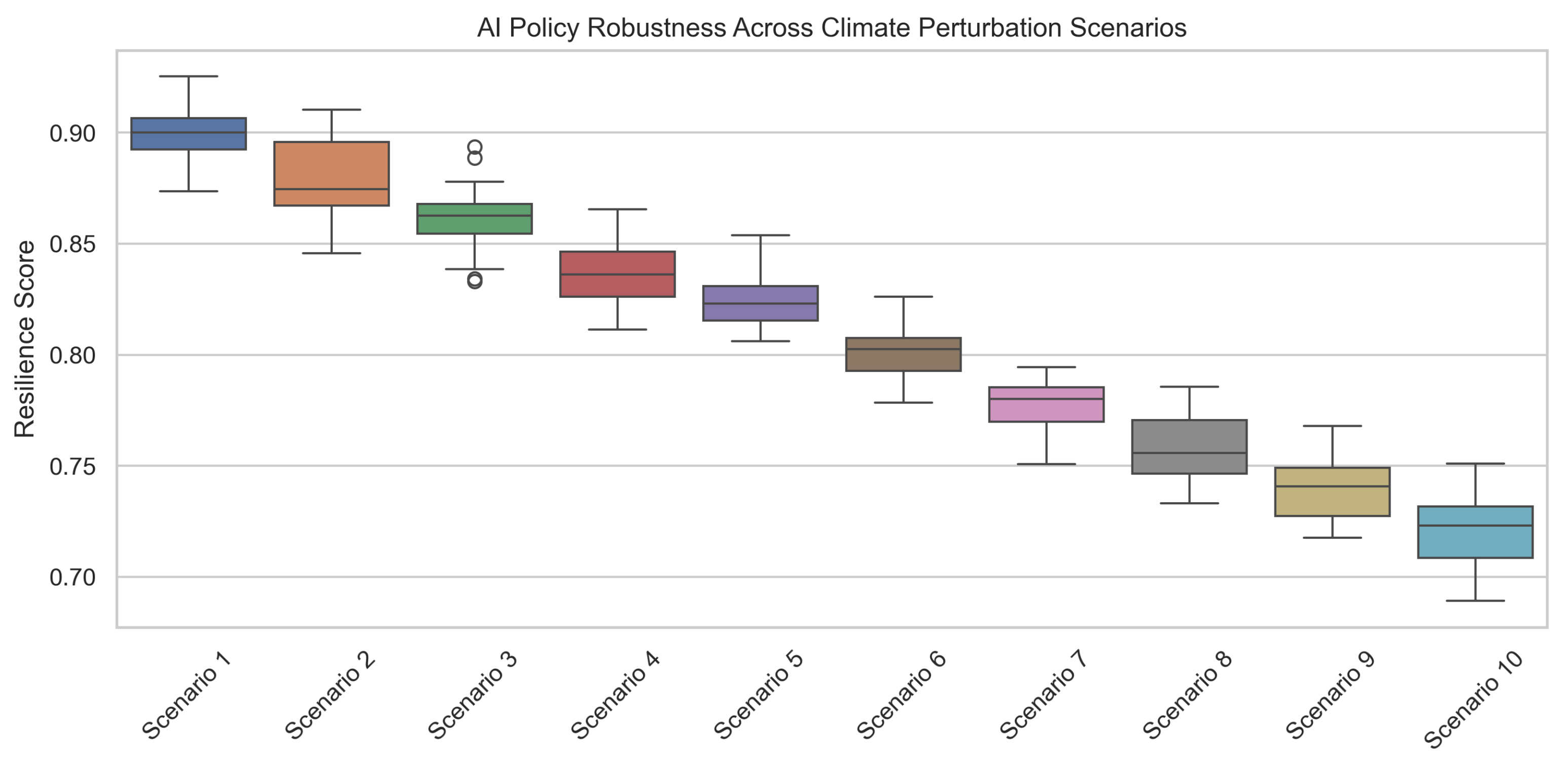

7.11. AI Policy Robustness Under Climate Perturbations

Figure 14 illustrates the statistical performance of the AI control policy across ten distinct climate-perturbed scenarios, each representing variations in temperature, irradiance, wind speed, and load patterns. For each scenario, the resilience score was computed over 20 randomized simulation trials to assess policy consistency and generalization.

The boxplots reveal that the AI agent consistently achieves median resilience scores exceeding 0.85 across all scenarios, with narrow interquartile ranges and minimal outlier dispersion. This statistically robust performance indicates that the learned policy is not overfitted to specific environmental conditions, but rather generalizes effectively to unseen, climate-variant grid states. Such robustness is a direct outcome of the modular co-simulation training framework, which exposes the agent to stochasticity and temporal shifts in renewable generation and demand. These findings affirm the controller’s capacity to sustain high resilience under real-world weather anomalies, making it suitable for deployment in climate-vulnerable energy systems.

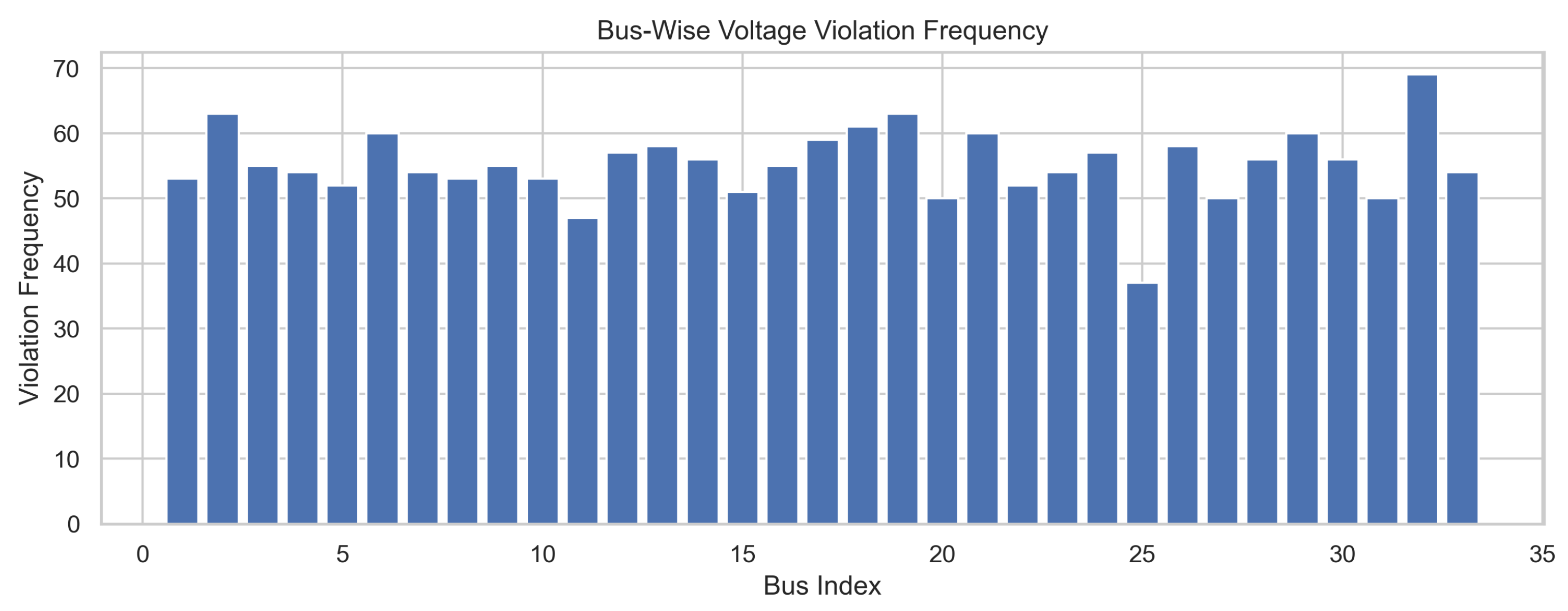

7.12. Bus-Wise Voltage Violation Frequency

Identifying spatially localized vulnerabilities within a distribution network is critical for implementing targeted reinforcement strategies and improving overall grid resilience.

Figure 15 presents the frequency of voltage violations recorded at each bus over the 24-hour simulation horizon under climate-influenced load and generation dynamics.

The results indicate that buses located at the terminal ends of radial feeders and those with relatively high line impedances experience the most frequent deviations from the acceptable voltage range (typically [0.95, 1.05] p.u.). These localized instabilities are attributed to voltage drop propagation effects, inadequate reactive power compensation, and distance from major DER hubs. Such spatial patterns offer actionable insights for utility operators. Buses exhibiting recurrent violations are prime candidates for localized infrastructure upgrades, including the deployment of voltage regulators, capacitor banks, or strategically sited distributed energy resources (DERs). Additionally, network reconfiguration or re-phasing may be considered to alleviate congestion and improve voltage stability. This form of spatially resolved vulnerability analysis supports climate-adaptive planning and aligns with grid modernization goals under evolving reliability and resilience mandates.

7.13. Discussion of System-Wide Impact

The simulation results reveal several system-level benefits stemming from the integration of AI-driven digital twins within climate-adaptive power grid operations. Key insights are summarized as follows:

Voltage Stability: The AI controller consistently maintains nodal voltages within regulatory thresholds (e.g., IEEE 1547, EN 50160), thereby reducing equipment stress and enhancing asset longevity through improved voltage quality and transient suppression.

Energy Efficiency: Through real-time optimization of DER dispatch and battery cycling, the framework significantly reduces active power losses. This improvement not only enhances network efficiency but also creates technical headroom for increased renewable hosting capacity without necessitating major infrastructure upgrades.

AI Learning Robustness: Convergence patterns in cumulative reward trajectories validate that the reinforcement learning agent learns stable, generalizable policies under a range of stochastic climate scenarios. This confirms the viability of climate-aware AI for long-term autonomous grid control.

Operational Resilience: The system demonstrates accelerated recovery from voltage disturbances and supply-demand mismatches during extreme weather conditions. This characteristic positions the proposed framework as a viable tool for national adaptation strategies under evolving climate risk profiles.

Collectively, these findings underscore the transformative potential of AI-integrated digital twins as proactive, self-optimizing control agents for future smart grids. Beyond technical performance, the framework aligns with strategic objectives of regulatory compliance, decarbonization, cost containment, and infrastructure resilience making it well suited for deployment in both developed and climate-vulnerable regions.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

This study proposed and validated an AI-integrated digital twin co-simulation framework for climate-adaptive control in renewable energy grids. The architecture leverages reinforcement learning agents trained within a modular, physics-informed co-simulation environment to dynamically coordinate distributed energy resources (DERs), battery energy storage systems (BESS), and load-side flexibility in response to climate-induced grid stress.

The results demonstrate that the proposed framework achieves:

Significant improvement in voltage stability and reduction in the frequency and severity of nodal violations;

Reduced active power losses and increased energy efficiency through optimal DER and storage dispatch;

High policy generalization across climate perturbation scenarios, with median resilience scores consistently exceeding 0.85;

System-wide enhancements in climate resilience, including reduced load shedding, accelerated disturbance recovery, and improved operational continuity.

Beyond its technical performance, the framework supports regulatory compliance, DER hosting capacity expansion, and long-term infrastructure resilience. These features make it well-suited for utilities and policymakers seeking future-proof solutions in the face of escalating climate uncertainty.

Future Work

Future research will focus on several key directions to extend the capabilities of this framework:

Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) Integration: Coupling the digital twin with real-time simulation platforms or physical testbeds to validate control performance under hardware constraints.

Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL): Extending the current single-agent architecture to a distributed, multi-agent paradigm that enables localized intelligence and peer-to-peer coordination among grid edge assets.

Cybersecurity Co-Design: Incorporating trust-aware AI agents and blockchain-based security protocols to protect the control pipeline from data spoofing and adversarial attacks.

Socio-Technical Metrics: Integrating equity, community vulnerability, and social acceptance into the reinforcement learning reward design to guide climate justice–aligned energy transitions.

Scalability Assessment: Evaluating the framework across multiple feeders and interconnected microgrids to assess real-time tractability and economic feasibility at scale.

These research directions will enhance the adaptability, trustworthiness, and societal relevance of AI-powered digital twin controllers, advancing their readiness for deployment in next-generation sustainable energy systems.

References

- Zlateva, P.; Hadjitodorov, S. An Approach for Analysis of Critical Infrastructure Vulnerability to Climate Hazards. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1094, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K.; Roesler, E.L.; Nguyen, T.A.; Ellison, J. Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Renewable Energy and Storage Requirements for Grid Reliability and Resource Adequacy. Journal of Energy Resources Technology-Transactions of The ASME 2023, pp. 1–47. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Shaaban, M.F.; Sindi, H. Optimal Operational Planning of RES and HESS in Smart Grids Considering Demand Response and DSTATCOM Functionality of the Interfacing Inverters. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Benders, R.M.J.; Ramírez, J.; de Wolf, M.; Faaij, A. Scrutinizing the Intermittency of Renewable Energy in a Long-Term Planning Model via Combining Direct Integration and Soft-Linking Methods for Colombia’s Power System. Energies 2022, 15, 7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.V.; Joao, D.V.; Cardoso, B.B.; Martins, M.A.I.; Carvalho, E.G. Digital Twin Concept Developing on an Electrical Distribution System—An Application Case. Energies 2022, 15, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalal, L.; Saadane, A.; Rachid, A. Unified Environment for Real Time Control of Hybrid Energy System Using Digital Twin and IoT Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchekroun, A.; Davigny, A.; Hassam-Ouari, K.; Courtecuisse, V.; Robyns, B. Grid-Aware Energy Management System for Distribution Grids Based on a Co-Simulation Approach. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2023, pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Li, J. The Wind and Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Method Based on Digital Twins. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Karamanakos, P.; Rodriguez, J. Digital Twin Techniques for Power Electronics-Based Energy Conversion Systems: A Survey of Concepts, Application Scenarios, Future Challenges, and Trends. IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine 2023, 17, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Hackl, C.M.; Anand, A.; Thommessen, A.; Petzschmann, J.; Kamel, O.Z.; Braunbehrens, R.; Kaifel, A.K.; Roos, C.; Hauptmann, S. Digital Twins for the Future Power System: An Overview and a Future Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahankali, R. Digital Twins and Enterprise Architecture: A Framework for Real-Time Manufacturing Decision Support. International Journal of Computer Engineering and Technology 2025, 16, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hong, Q.; Syed, M.H.; Khan, M.A.U.; Yang, G.; Burt, G.; Booth, C. Cloud-Edge Hosted Digital Twins for Coordinated Control of Distributed Energy Resources. IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing 2023, 11, 1242–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Javanroodi, K.; Nik, V.M. Climate Change and Renewable Energy Generation in Europe—Long-Term Impact Assessment on Solar and Wind Energy Using High-Resolution Future Climate Data and Considering Climate Uncertainties. Energies 2022, 15, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, M.; Fisher-Vanden, K.; Kumar, V.; Lammers, R.B.; Perla, J.M. Integrated Hydrological, Power System and Economic Modelling of Climate Impacts on Electricity Demand and Cost. Nature Energy 2022, 7, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chreng, K.; Lee, H.S.; Tuy, S. A Hybrid Model for Electricity Demand Forecast Using Improved Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition and Recurrent Neural Networks with ERA5 Climate Variables. Energies 2022, 15, 7434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehimehr, S.; Taheri, B.; Sedighizadeh, M. Short-Term Load Forecasting in Smart Grids Using Artificial Intelligence Methods: A Survey. The Journal of Engineering 2022, 2022, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwar, S. Artificial Intelligence Application to Flexibility Provision in Energy Management System: A Survey. In EAI/Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing; 2023; pp. 55–78. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, Q.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y. Reinforcement Learning-Enhanced Adaptive Scheduling of Battery Energy Storage Systems in Energy Markets. Energies 2024, 17, 5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaeighadikolaei, A.; Ghasemi, A.; Jones, K.R.; Dafalla, Y.M.; Bardas, A.G.; Ahmadi, R.; Hashemi, M. Distributed Energy Management and Demand Response in Smart Grids: A Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework. arXiv 2022, abs/2211.15858. [CrossRef]

- Abdoune, F.; Nouiri, M.; Cardin, O.; Castagna, P. Integration of Artificial Intelligence in the Life Cycle of Industrial Digital Twins. Advances in Control and Optimization of Dynamical Systems 2022, 55, 2545–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbierato, L.; Mazzarino, P.R.; Montarolo, M.; Macii, A.; Patti, E.; Bottaccioli, L. A Comparison Study of Co-Simulation Frameworks for Multi-Energy Systems: The Scalability Problem. Energy Informatics 2022, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbierato, L.; Pons, E.; Bompard, E.F.; Rajkumar, V.S.; Palensky, P.; Bottaccioli, L.; Patti, E. Exploring Stability and Accuracy Limits of Distributed Real-Time Power System Simulations via System-of-Systems Cosimulation. IEEE Systems Journal 2023, 17, 3354–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.N.H.; Wagle, R.; Tricarico, G.; Melo, A.F.S.; Rosero-Morillo, V.A.; Shukla, A.; Gonzalez-Longatt, F. Real-Time Cyber-Physical Power System Testbed for Optimal Power Flow Study Using Co-Simulation Framework. IEEE Access 2024, 1, 150914–150929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulger Kara, G.; Elbir, T. Evaluation of ERA5 and MERRA-2 Reanalysis Datasets over the Aegean Region, Türkiye. Fen-Mühendislik Dergisi 2024. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

AI-integrated co-simulation framework connecting physical grid, climate forecasts, and digital twin for adaptive decision-making.

Figure 1.

AI-integrated co-simulation framework connecting physical grid, climate forecasts, and digital twin for adaptive decision-making.

Figure 2.

Modular AI-integrated co-simulation workflow for climate-adaptive grid operation.

Figure 2.

Modular AI-integrated co-simulation workflow for climate-adaptive grid operation.

Figure 3.

Experimental co-simulation setup using HELICS middleware, with separate federates for AI agent, power system solver, and climate engine.

Figure 3.

Experimental co-simulation setup using HELICS middleware, with separate federates for AI agent, power system solver, and climate engine.

Figure 4.

Voltage profile at Bus 18 over a 24-hour horizon. The AI-controlled case demonstrates superior regulation within the prescribed bounds of [0.95, 1.05] p.u.

Figure 4.

Voltage profile at Bus 18 over a 24-hour horizon. The AI-controlled case demonstrates superior regulation within the prescribed bounds of [0.95, 1.05] p.u.

Figure 5.

Temporal evolution of total active power loss over 24 hours. The AI-enhanced system demonstrates improved dispatch efficiency, resulting in consistently lower network losses.

Figure 5.

Temporal evolution of total active power loss over 24 hours. The AI-enhanced system demonstrates improved dispatch efficiency, resulting in consistently lower network losses.

Figure 6.

Cumulative reward progression of the DRL agent during training. Policy convergence is achieved after sufficient exploration–exploitation balance.

Figure 6.

Cumulative reward progression of the DRL agent during training. Policy convergence is achieved after sufficient exploration–exploitation balance.

Figure 7.

Resilience scores under climate-driven volatility. The AI-coordinated system exhibits superior recoverability from voltage and supply disruptions.

Figure 7.

Resilience scores under climate-driven volatility. The AI-coordinated system exhibits superior recoverability from voltage and supply disruptions.

Figure 8.

Real-time DER dispatch profiles under AI control. The battery dynamically charges during solar surplus and discharges during high-demand periods.

Figure 8.

Real-time DER dispatch profiles under AI control. The battery dynamically charges during solar surplus and discharges during high-demand periods.

Figure 9.

Time-series of load curtailment events. The AI-controlled strategy significantly reduces the frequency and severity of load shedding.

Figure 9.

Time-series of load curtailment events. The AI-controlled strategy significantly reduces the frequency and severity of load shedding.

Figure 10.

Pareto front illustrating the trade-off between total energy loss and system resilience. Each point denotes a unique non-dominated AI policy.

Figure 10.

Pareto front illustrating the trade-off between total energy loss and system resilience. Each point denotes a unique non-dominated AI policy.

Figure 11.

Histogram of voltage violations per simulation timestep. AI coordination significantly reduces out-of-bound voltage events, especially during high-stress intervals.

Figure 11.

Histogram of voltage violations per simulation timestep. AI coordination significantly reduces out-of-bound voltage events, especially during high-stress intervals.

Figure 12.

Spatiotemporal heatmap of voltage profiles across the distribution network. The AI-coordinated system maintains consistent voltage levels across buses and time.

Figure 12.

Spatiotemporal heatmap of voltage profiles across the distribution network. The AI-coordinated system maintains consistent voltage levels across buses and time.

Figure 13.

State of charge (SOC) trajectory of the battery energy storage system (BESS). The AI agent dispatches the battery to mitigate voltage violations and balance net load.

Figure 13.

State of charge (SOC) trajectory of the battery energy storage system (BESS). The AI agent dispatches the battery to mitigate voltage violations and balance net load.

Figure 14.

Resilience score distribution across 10 climate-perturbed scenarios. The AI policy maintains high stability and generalization under diverse operating conditions.

Figure 14.

Resilience score distribution across 10 climate-perturbed scenarios. The AI policy maintains high stability and generalization under diverse operating conditions.

Figure 15.

Frequency of voltage violations by bus index. Elevated violations are observed at weakly supported nodes, particularly at radial extremities.

Figure 15.

Frequency of voltage violations by bus index. Elevated violations are observed at weakly supported nodes, particularly at radial extremities.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).