1. Introduction

Mold flux, as a key functional material in the continuous casting process, is crucial for ensuring smooth operation and high-quality slabs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Currently, significant issues persist in the selection and application of mold fluxes at steel plants, hindering their ability to adequately meet the requirements for casting exceptional steel grades. This situation impedes progress in expanding the range of steel grades, increasing casting speeds, improving slab quality, and further elevating the level of continuous casting [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. As exceptional steel grades continue to evolve, the development focus for mold fluxes has shifted towards product serialization, performance stability, and high compatibility with continuous casting process conditions [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Addressing the application scenarios of mold fluxes in the continuous casting process of exceptional steel grades requires comprehensive technical analysis to identify the precise matching relationship between industrial steel grades and mold fluxes, and to clarify the discrepancies between required and supplied flux properties, in order to provide a basis for developing new mold fluxes suitable for continuous casting production requirements.

Hebei Iron and Steel Co., Ltd. in China produces the low-alloy peritectic steel using the slab continuous caster. This steel grade possesses excellent impact toughness, wear resistance, and weldability, making it a type of high-strength structural steel widely used in manufacturing buildings, bridges, ships, pipelines, and automotive components [

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, phenomena such as surface cracks, slag entrapment, and sticker breakouts frequently occur during the continuous casting of this steel grade, to some extent reducing the comprehensive yield of slabs and increasing steelmaking production costs [

19,

20]. Tracing the root causereveals that this issue is closely related to the mold fluxes used in continuous casting process. Many problems remain to be solved regarding the matching between mold fluxes and steel grades, as well as casting process conditions. Therefore, this paper conducted an industrial survey on the continuous casting of low-alloy peritectic steel, collecting the typical and representative samples of mold fluxes and corresponding flux films used the continuous casting process, and then systematically studied the physical properties of mold fluxes and the mineralogical characteristics of flux films, exploring their lubrication and heat transfer mechanisms as well as connection with slab quality.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

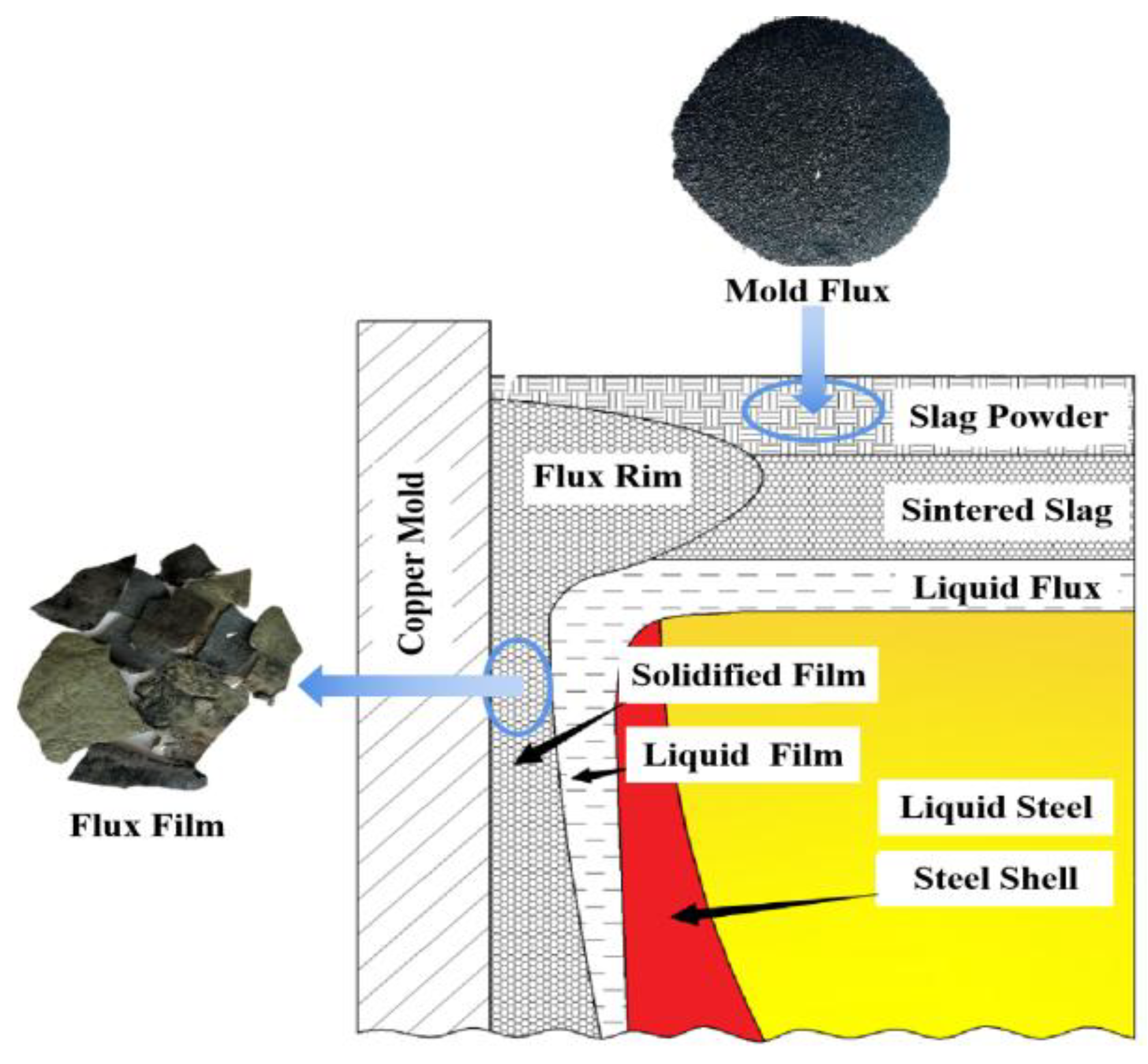

The low-alloy steel continuous casting mold flux and flux film samples used in this work were provided by Hebei Iron and Steel Co., Ltd. in China. On-site tracking and investigation were conducted on the continuous casting process of two typical low-alloy peritectic steels (referred to as Steel A and Steel B). Corresponding mold flux samples (referred to as Flux A and Flux B) as well as their solidified flux film samples were collected respectively. The flux film samples were taken from the meniscus region near the top of the copper mold when the continuous casting process was usually stopped. The distribution of mold flux and the sampling position of the flux film in the mold are shown in

Figure 1. The chemical compositions of the mold flux and flux film samples for low-alloy steel continuous casting are shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Methods for Testing Physical Properties of Mold Flux

The melting point tester (KFMP-1600A, Kefeng Metallurgical New Materials Co., Ltd., Luoyang, China) was used to observe the high-temperature melting process of the mold flux samples in-situ, following the Chinese Industrial Standard (GB/T 40404-2021). During the experiment, the sample was heated at a rate of 10°C/min. The temperatures at which the sample height reduced to 3/4, 2/4, and 1/4 of its original height were recorded and defined as the softening temperature, hemispherical temperature (melting point), and flow temperature of the sample, respectively.

Following the Chinese Industrial Standard (YB/T185-2017), the high-temperature viscometer (RTW-13, Northeastern University, Shenyang, China) was used to measure the viscosity data of the test fluxes during cooling, construct viscosity-temperature curves, analyze the break temperature where viscosity begins to change abruptly, and record the viscosity value at 1300°C to characterize the viscosity properties of the test fluxes.

The high-temperature in-situ thermal analyzer (S/DHTT-TA-III, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China) was used to observe the crystallization process of mold flux samples under different cooling rates and target temperatures. By identifying significant changes in slag surface morphology and light transmittance, the temperature-time points for the start and end of crystallization were accurately determined. These data allowed the construction of continuous cooling transformation (CCT) curves and isothermal transformation (TTT) curves for the test fluxes. Key crystallization parameters, such as the critical crystallization cooling rate and initial crystallization temperature, were analyzed from these curves.

2.3. Methods for Analyzing Mineralogical Characteristics and Mechanism of Flux Film

Part of the flux film samples from each group were bonded together using epoxy adhesive. Sections along the thickness direction were mounted on glass slides, ground to a thickness of 0.03 mm, and polished to prepare thin sections for microscopy. Other flux film samples were completely ground to a powder state with a particle size of 0.074 mm. Polarizing microscope (Axio Scope A1 pol, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to observe the thin sections of the flux film samples to analyze mineralogical characteristics such as mineral composition, crystallization ratio, and microstructure. The crystalline phase composition of powdered flux films was detected using an X-ray diffractometer (D8 Advance, Bruker AXS, Bremen, Germany) within a scanning range of 10° to 90°.

FactSage software was used to simulate the equilibrium crystallization process of the flux films. Key parameters such as the types of precipitated minerals, precipitation temperatures, and precipitation amounts during crystallization were obtained by plotting multi-component multi-phase equilibrium diagrams using the Equilib calculation module. This study explored the crystallization behavior of each mineral phase and provided an in-depth analysis to elucidate the formation mechanisms of the flux film mineralogy.

Following the Chinese Industrial Standard (YB/T4130-2018), the flat-plate thermal conductivity meter (PBD-13-4P, LIRR, Luoyang, China) was used to measure the changes in the thermal conductivity of solid flux film samples within the temperature range of 200°C to 600°C. Combined with the mineralogical structure characteristics of the flux films, this helped analyze the heat transfer mechanism of the flux film mineralogy.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Melting Properties of Mold Flux

Melting temperature and viscosity are two fundamental indicators of mold flux melting properties, significantly impacting the stability of the continuous casting process and the slab surface quality [

21,

22,

23,

24]. The melting point tester was used to observe the high-temperature melting process of the mold flux samples and record the softening temperature, hemispherical temperature, and flow temperature (

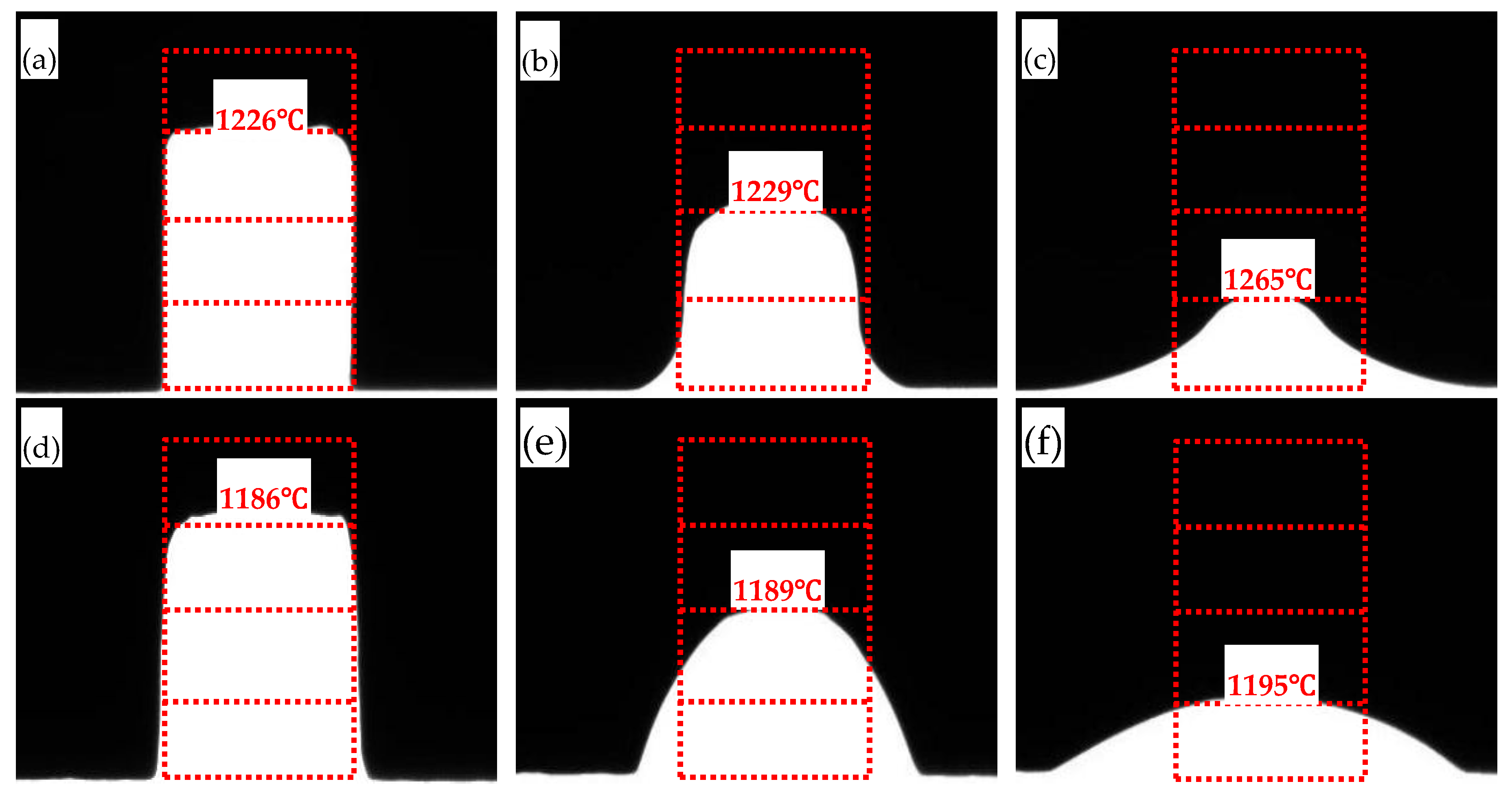

Figure 2). The two mold fluxes studied for low-alloy peritectic steel casting have different melting temperature ranges. The melting temperature range for Flux A is 1226–1265°C, while for Flux B it is 1186–1195°C. It can be seen that all melting temperature indicators for Flux B are lower than those for Flux A, and its melting temperature range is narrower.

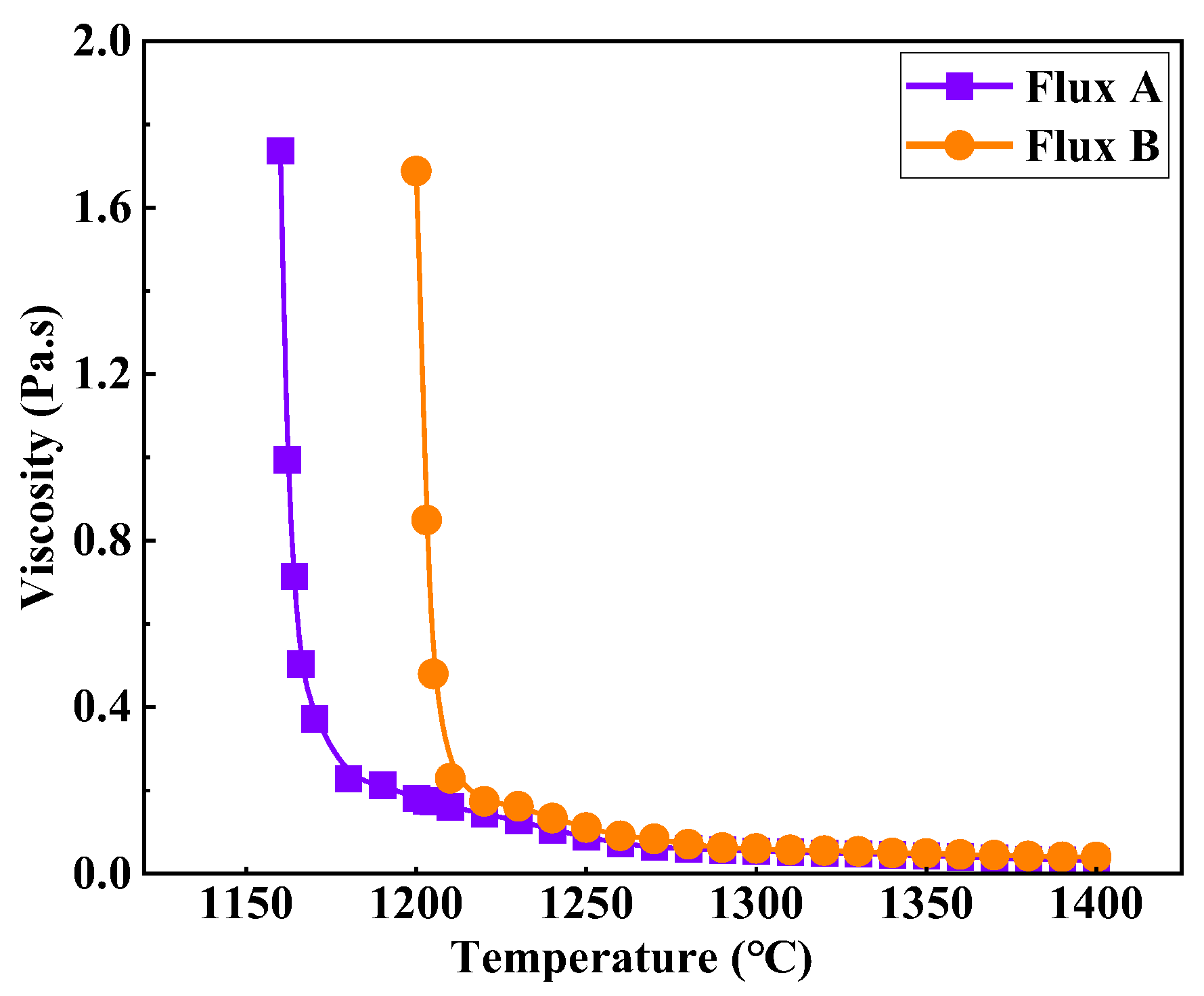

Figure 3 shows the viscosity-temperature curves of the two industrial mold fluxes for low-alloy peritectic steel. As the temperature decreases gradually from 1400°C, the viscosity of both industrial fluxes initially increases slowly. Upon reaching a specific temperature (break temperature), the viscosity value begins to rise sharply. Flux A has a viscosity of 0.055 Pa·s at 1300°C and a break temperature of 1180°C. Flux B has a viscosity of 0.060 Pa·s at 1300°C and a break temperature of 1210°C. Although the viscosity values of Flux A and Flux B at 1300°C are similar, the break temperature of Flux B is 30°C higher than that of Flux A. Based on silicate slag structure theory, this is likely due to the slightly higher binary basicity and main flux content (Na₂O) of Flux B compared to Flux A. This composition characteristic promotes increased polymerization of the silicate network structure during cooling, causing the flux to crystallize more readily, resulting in an earlier viscosity break point and a sharper viscosity increase.

3.2. Crystallization Behavior of Mold Flux

Crystallization behavior indicators, such as critical crystallization cooling rate, initial crystallization temperature, and crystallization incubation time, control the formation characteristics and structure of the flux film between the mold and strand. They are crucial parameters for coordinating heat transfer and lubrication [

25,

26,

27,

28]. The high-temperature in-situ thermal analyzer was used to observe the entire process of melting and crystallization of the mold flux samples (

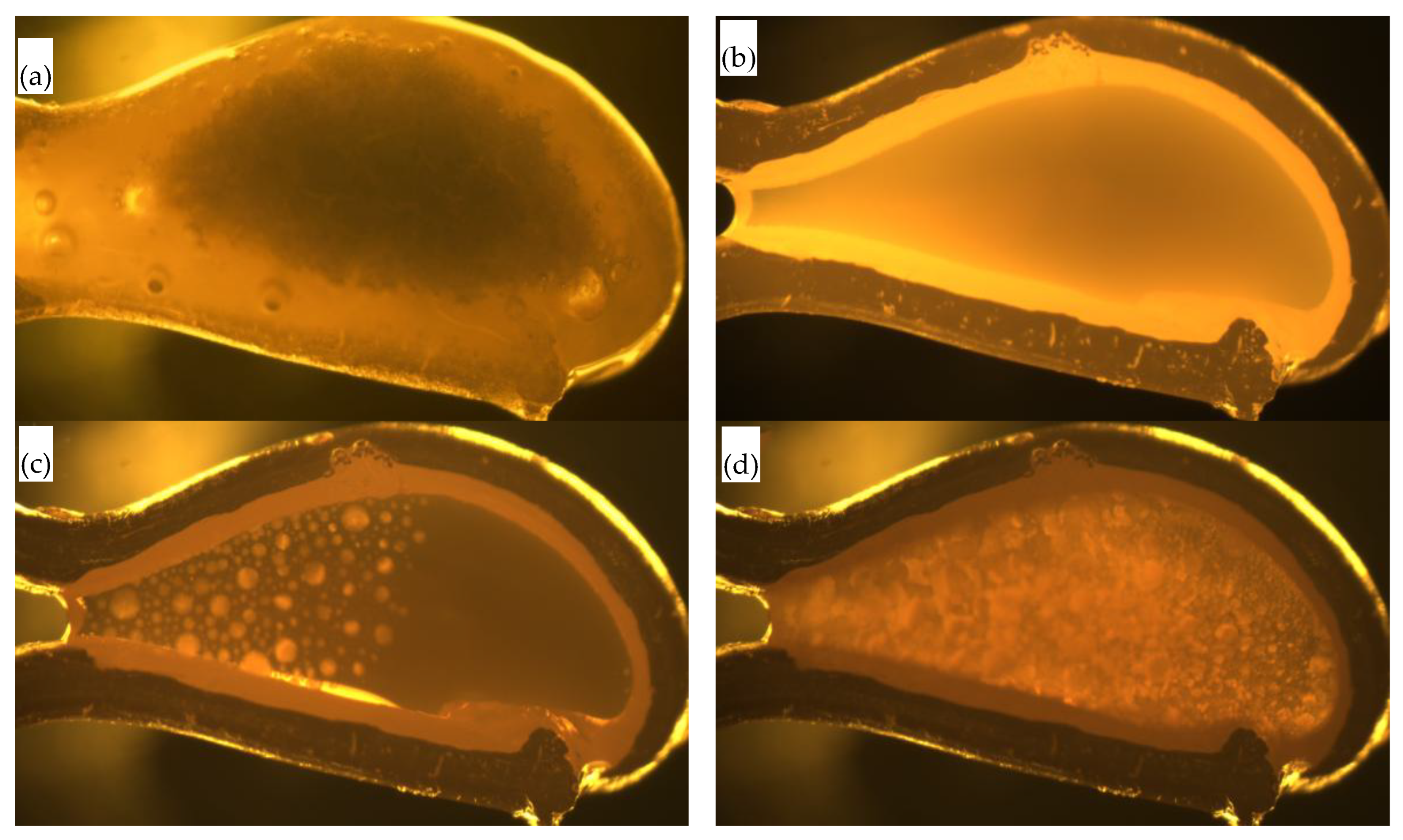

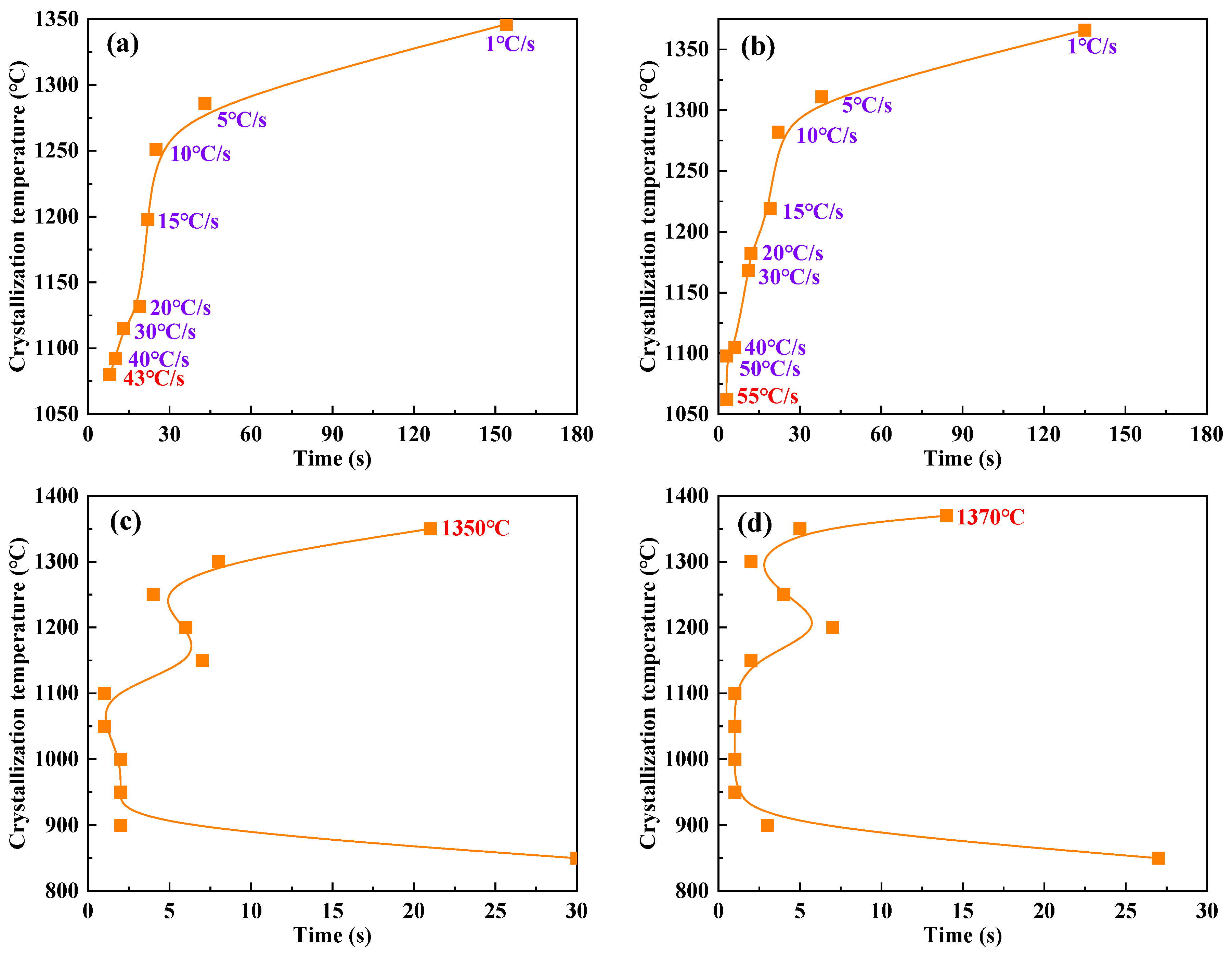

Figure 4). Under experimental conditions of continuous cooling transformation and isothermal transformation, the continuous cooling transformation (CCT) curves and isothermal transformation (TTT) curves of the mold fluxes were constructed (

Figure 5), ultimately allowing the accurate determination of crystallization behavior parameters such as the critical crystallization cooling rate and initial crystallization temperature.

The CCT curves show that as the cooling rate gradually increases, the crystallization temperatures of both Flux A and Flux B exhibit a clear decreasing trend. Under the same cooling rate, the crystallization temperature of Flux B is slightly higher than that of Flux A, and the critical crystallization cooling rate of Flux B is significantly greater than that of Flux A. The TTT curves show that the crystallization temperature ranges and initial crystallization temperatures of Flux A and Flux B are essentially the same. However, under identical isothermal conditions, the crystallization incubation times of Flux B are generally shorter than those of Flux A. The combined experimental results indicate that Flux B, compared to Flux A, maintains a higher crystallization temperature even at higher cooling rates, demonstrating stronger crystallization capability. Furthermore, the shorter crystallization incubation time of Flux B means its crystallization process is faster, which is beneficial for rapidly forming a stable flux film during continuous casting, thereby optimizing heat transfer and lubrication effects.

3.3. Mineralogical Structure of Flux Film

The flux film formed when mold flux flows into the gap between the mold wall and the solidifying shell. The mineralogical structure characteristics generated during the solidification of this flux film are also key factors determining heat transfer uniformity and slab crack incidence [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. This work employed polarizing microscopy combined with XRD to identify and analyze the microstructural characteristics of industrial flux films, focusing on the composition, content, morphology, and size of crystalline minerals.

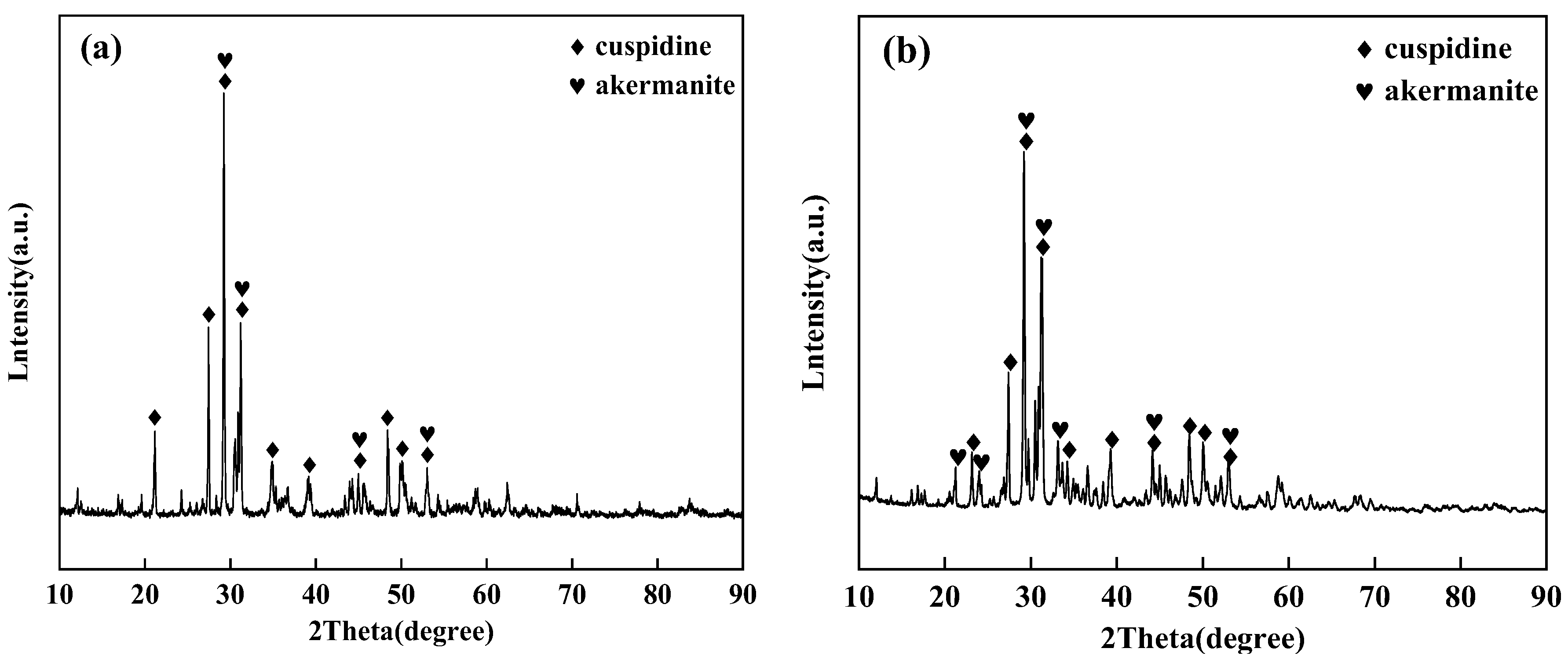

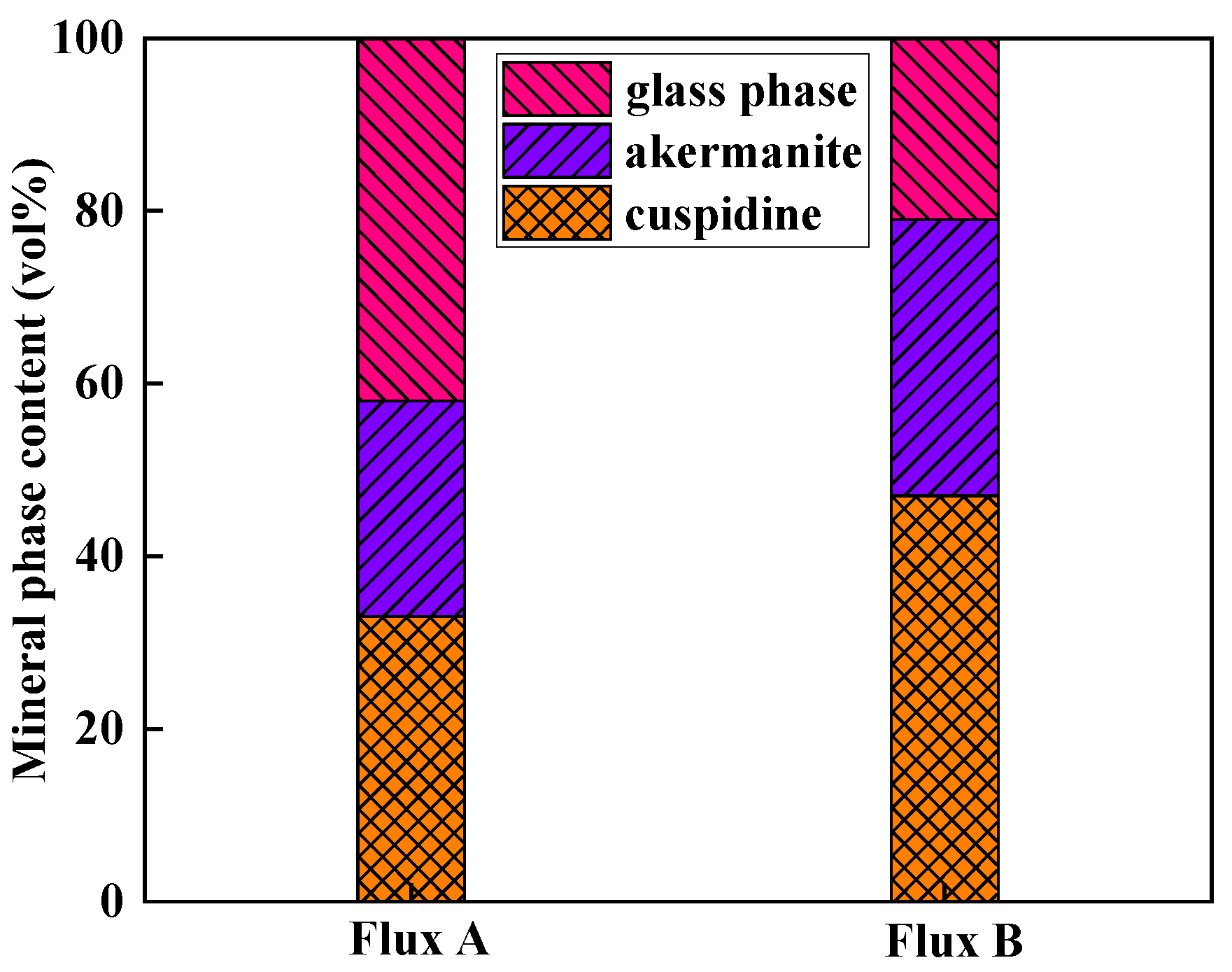

Based on the identification results from polarizing microscopy and XRD (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), the main crystalline phases in the industrial flux films corresponding to Flux A and Flux B are cuspidine and akermanite, with crystallization ratios concentrated between 50% and 80%. Compared to Flux A, Flux B's flux film exhibits a stronger ability to precipitate cuspidine and akermanite, especially with cuspidine content approximately 15% higher, resulting in an overall higher crystallization ratio for the flux film.

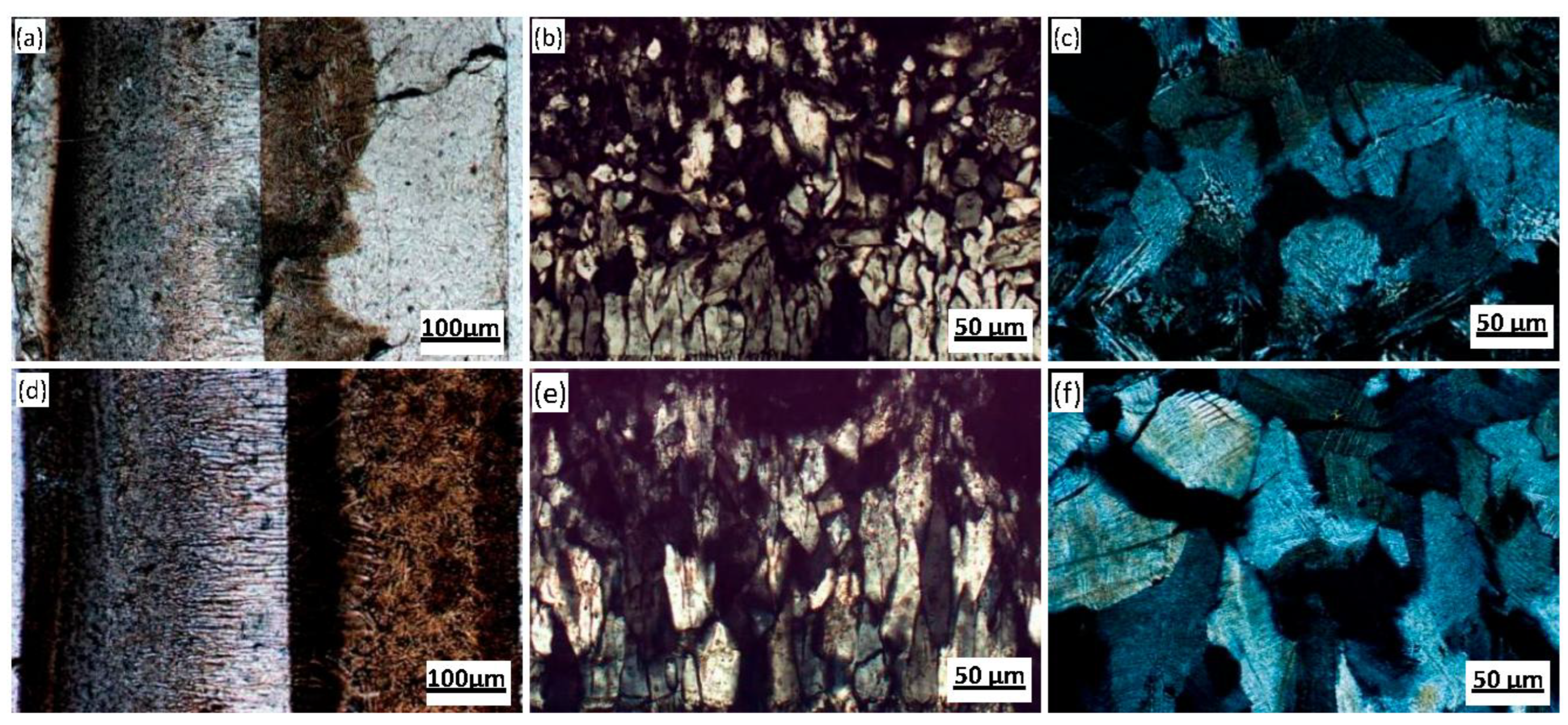

Polarizing microscopy was used to analyze and determine microstructural characteristics such as layered structure, mineral morphology, and grain size of the flux films (

Figure 8). The flux film of Flux A presents a typical "glass layer-crystalline layer-glass layer" three-layer structure. A distinct boundary within the middle crystalline layer divides it into a cuspidine layer and an akermanite layer. Cuspidine mostly appears as spearhead-shaped aggregates, while akermanite mostly appears as finely woven aggregates. The flux film of Flux B presents a typical "glass layer-crystalline layer" two-layer structure. The crystalline layer is further divided into a cuspidine layer and an akermanite layer. Cuspidine precipitates in large quantities, primarily as well-crystallized coarse spearhead-shaped and platy crystals; akermanite appears mainly as granular and woven aggregates.

The research results indicate that although the solidified flux films of different composition fluxes exhibit differences in mineral morphology and grain size characteristics, the layered distribution pattern of the mineralogical structure within the flux film is consistent. When liquid slag flows into the gap between the mold and strand, the side near the mold wall rapidly solidifies due to chilling, forming the glass layer of the flux film first. The contact between the glass layer and the mold wall creates significant interfacial thermal resistance, leading to a devitrification phenomenon in the glass layer. The crystals initially precipitating within this glass layer are primarily cuspidine. As the temperature drops rapidly on the strand side, the liquid flux film begins to solidify, precipitating akermanite crystals or forming another new glass layer.

3.4. Mineralogical Formation Pattern of Flux Film

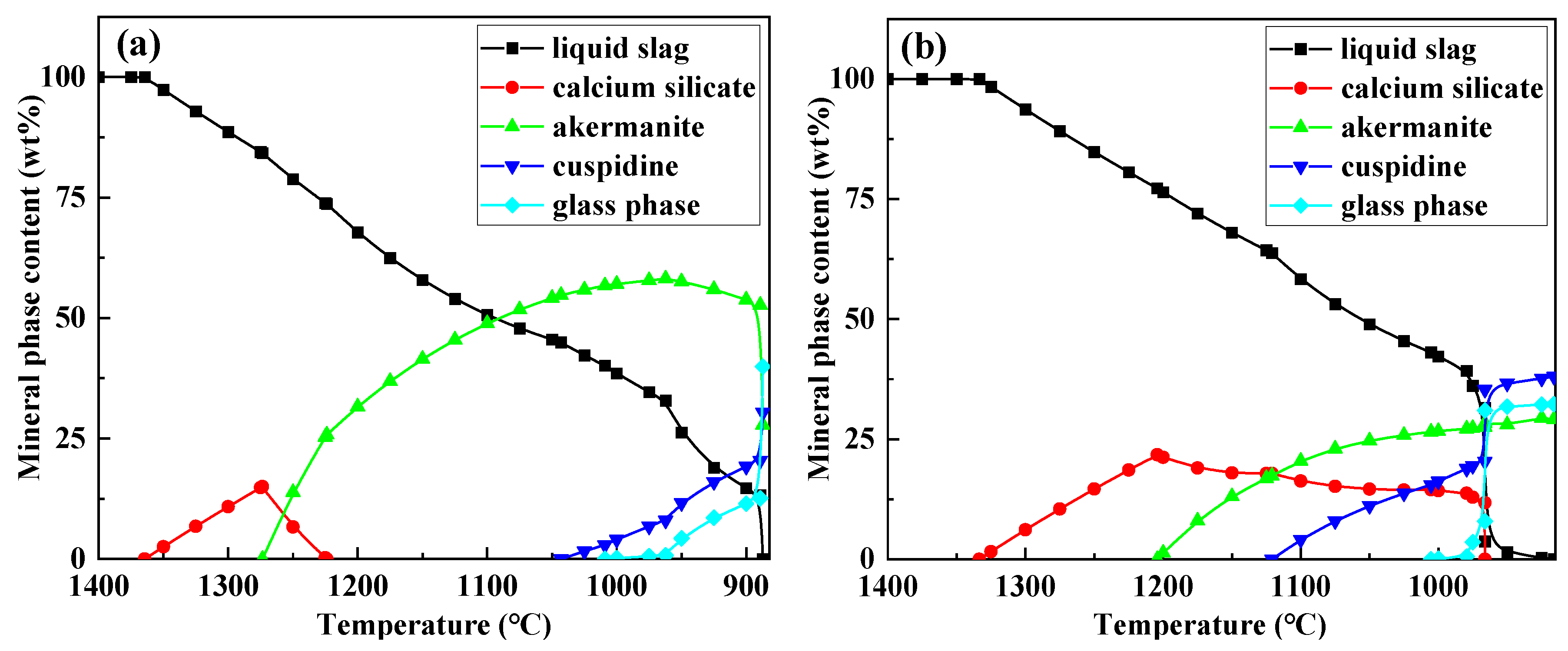

To further elucidate the formation mechanism of flux film mineralogy, based on the chemical composition characteristics of the industrial mold fluxes, FactSage software was used to simulate the equilibrium crystallization process for Flux A and Flux B. Multi-component multi-phase equilibrium diagrams were plotted using the Equilib calculation module, and key parameters such as the types of precipitated minerals, precipitation temperatures, and precipitation contents during crystallization were obtained (

Figure 9).

The crystallization process simulation results show that as the temperature decreases, the amount of liquid slag for both Flux A and Flux B begins to decrease around 1350°C. At this stage, the intermediate phase calcium silicate precipitates. When the temperature drops below 1300°C, the crystalline mineral akermanite begins to precipitate. When the temperature drops below 1150°C, the crystalline mineral cuspidine also begins to precipitate. When the temperature continues to drop to 1000°C, the glass phase begins to precipitate in large quantities, after which the liquid slag amount decreases sharply until it completely transforms into solid phases. The precipitation sequence of mineral phases during crystallization is consistent for Flux A and Flux B. However, differences exist in the precipitation temperatures and amounts of each mineral phase, indicating that the composition of the mold flux significantly influences the formation behavior of flux film mineralogy. Therefore, by adjusting the composition of the mold flux, the formation of an ideal mineralogical structure in the flux film can be optimized.

3.5. Mineralogical Heat Transfer Mechanism of Flux Film

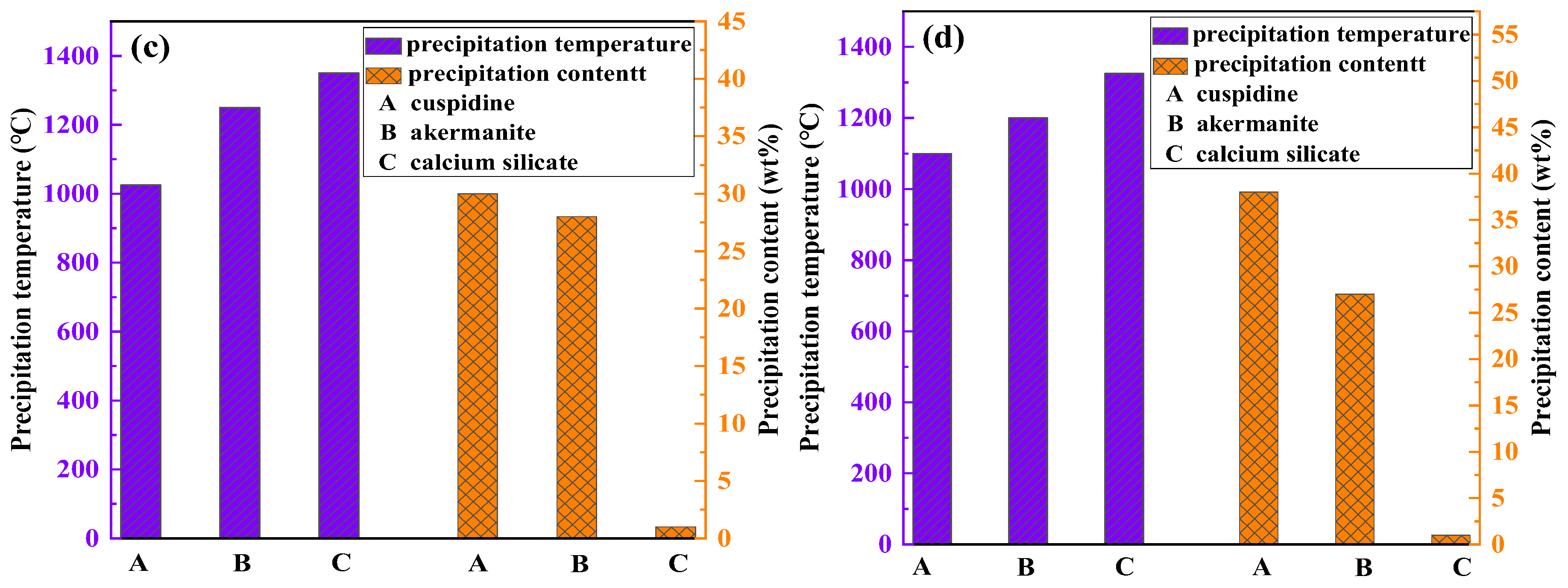

The thermal conductivity of the mold flux film is an important parameter characterizing its heat transfer performance [

34,

35]. Since the temperature of the solid flux film near the mold wall side is within the range of 200–600°C, studying thermal conductivity under this temperature gradient is key to understanding the heat transfer mechanism. Standard samples of solid flux films for Flux A and Flux B were prepared using a mold flux film simulation device. The thermal conductivity meter was used to measure the variation in thermal conductivity of the flux film samples within the 200–600°C temperature range (

Figure 10). The experimental results show that as the temperature rises from 200°C to 600°C, the thermal conductivity of the flux films for both Flux A and Flux B gradually increases, roughly within the range of 0.47–0.67 W/m·K. At the same temperature, the thermal conductivity of Flux B's flux film is significantly lower than that of Flux A, indicating that Flux B has a better ability to reduce the heat transfer rate within the mold. Furthermore, the change in thermal conductivity of Flux B's flux film with increasing temperature is more linear, suggesting it has advantages in controlling heat transfer uniformity and stability.

Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between the mineralogical structure and thermal conductivity of the flux films for the two industrial mold fluxes. Compared to Flux A, Flux B's flux film mineralogy features a higher cuspidine content. High cuspidine content in the flux film usually also implies a higher crystallization ratio, but the corresponding flux film thermal conductivity is lower. Analysis suggests two reasons: Firstly, among the main crystalline minerals in mold flux, cuspidine has a lower thermal conductivity than other phases like akermanite, effectively reducing the overall thermal conductivity of the flux film. Secondly, the abundant precipitation of cuspidine in the flux film can easily trigger excessive crystal growth and coarsening of morphology, potentially leading to an increase in interfaces between crystals and the formation of more micropores around them, thereby significantly reducing the thermal conductivity of the flux film.

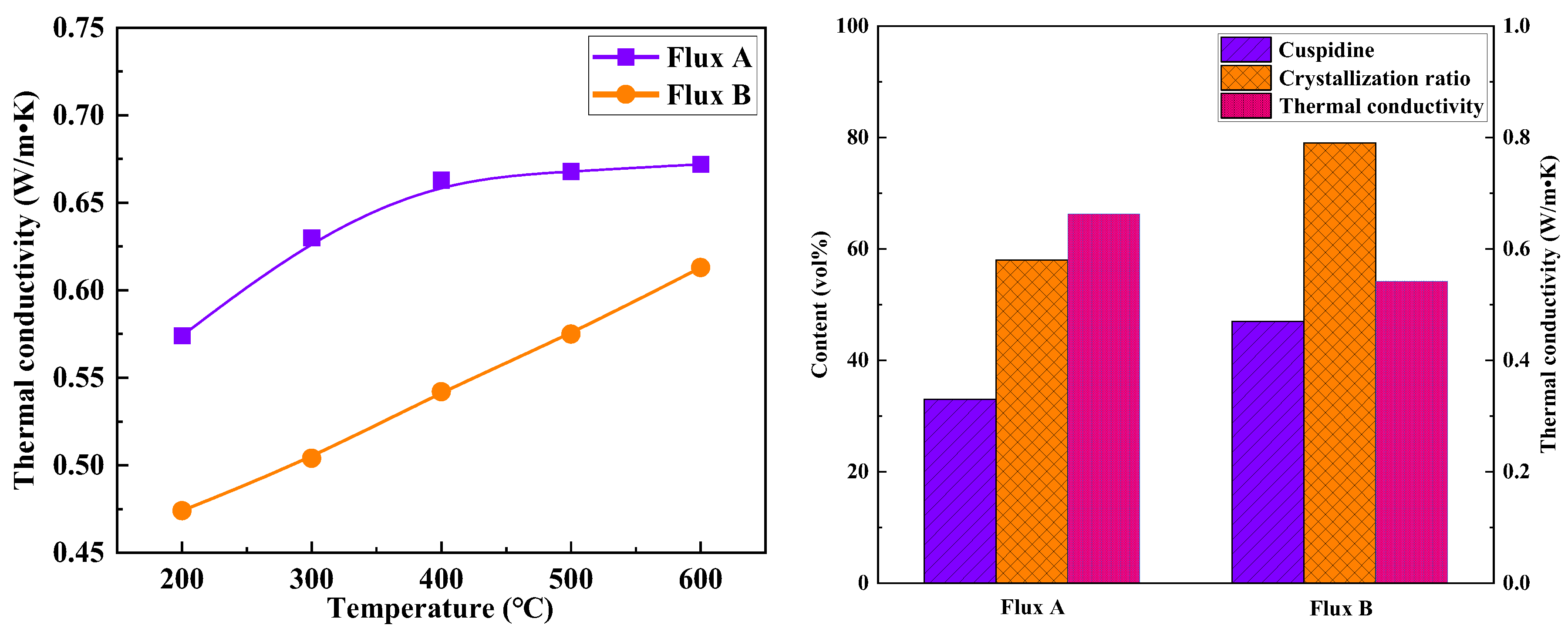

3.6. Discussion

Through systematic research on the physical properties and flux film mineralogical characteristics of the industrial mold fluxes (Flux A and Flux B) for low-alloy peritectic steel continuous casting, the differences between the two fluxes in terms of melting properties, rheological properties, crystallization behavior, mineralogical structure, and heat transfer performance can be clearly defined (

Figure 12). Their impact mechanisms on slab quality can be correlated.

The melting point (hemispherical temperature) of Flux B is significantly lower than that of Flux A, and its melting temperature range is narrower. This melting characteristic allows Flux B to form a more uniform liquid flux layer more easily within the mold, benefiting strand shell lubrication and reducing the risk of slag entrapment.

Although the viscosity values of Flux A and Flux B at 1300°C are similar, the break temperature of Flux B is 30°C higher than that of Flux A. Combined with slag structure theory, the higher binary basicity and Na2O content of Flux B promote the polymerization of the silicate network structure, causing its viscosity to rise sharply at higher temperatures. This viscosity characteristic may affect the fluidity of the slag in the high-temperature zone, increasing the risk of lubrication deterioration for the strand.

Flux B has a higher critical crystallization cooling rate, and under the same cooling rate, its crystallization temperature is higher than that of Flux A. This indicates that Flux B can still crystallize rapidly under high casting speed conditions, forming a stable crystalline layer in the flux film, which aids in uniform heat transfer. The crystallization incubation time of Flux B is shorter than that of Flux A, meaning its crystallization rate is faster, enabling rapid formation of the flux film structure and reducing instability of the liquid flux film, thereby lowering the incidence of sticker breakouts.

The crystallization ratio of Flux B's flux film is significantly higher than that of Flux A, with cuspidine content increased by approximately 15%. This mineralogical structural feature leads to the formation of more micropores and grain boundaries, thereby increasing the overall thermal resistance of the flux film. Consequently, the thermal conductivity of Flux B's flux film is markedly lower than that of Flux A, which can slow down the cooling rate of the strand shell in the mold, alleviating the volumetric shrinkage stress during the solidification of low-alloy peritectic steel, and thus inhibiting the formation of surface cracks.

In summary, Flux B outperforms Flux A in terms of melting properties, crystallization behavior, and heat transfer performance, making it more suitable for the efficient continuous casting of low-alloy peritectic steel. The higher Na₂O content and basicity of Flux B are key to its optimized performance. Through multi-faceted linkage analysis, the mapping relationship between mold flux physical properties, flux film mineralogical structure, and slab quality has been clarified, providing a basis for the precise design of mold fluxes for low-alloy peritectic steel continuous casting. Future mold flux development needs to balance further the contradiction between lubrication and heat transfer to adapt to higher casting speeds and more demanding steel grade requirements.

4. Conclusions

To better meet the requirements of low-alloy peritectic steel continuous casting, this study systematically investigated the physical properties of industrial mold fluxes and the mineralogical characteristics of their flux films. The following conclusions were drawn:

- (1)

Mold fluxes for low-alloy peritectic steel require a narrow melting temperature range, low melting point, and low viscosity. Both the melting point and viscosity break temperature should be below 1200°C to form a uniformly flowing liquid slag layer and enhance lubrication effectiveness.

- (2)

Strong crystallization capability is the core characteristic of mold fluxes for low-alloy peritectic steel. A high critical crystallization cooling rate (up to 50°C/s) and a high initial crystallization temperature (>1350°C) ensure the rapid formation of a stable flux film structure, enhancing heat transfer uniformity.

- (3)

The mineralogical structure of the flux film for low-alloy peritectic steel presents a multilayered structure with a high crystallization ratio (60–90 vol%), mainly composed of the crystalline minerals cuspidine and akermanite. Among these, cuspidine is characterized by high content and coarsened crystal morphology, which can effectively control the heat transfer rate.

- (4)

The thermal conductivity of flux film for low-alloy peritectic steel is generally low (0.47–0.67 W/m·K). The fundamental reason lies in the characteristics of high crystallization ratio and coarsened crystal morphology, which promote the formation of numerous micropores and grain boundaries between crystals, increasing the overall thermal resistance of the flux film.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z. and X.H.; methodology, formal analysis, D.Z. and L.L.; investigation, resources, J.G. and Y.Y.; data curation, D.Z. and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Z.; writing—review and editing, D.Z. and X.H.; visualization, D.Z. and L.L.; supervision, X.H.; project administration, D.Z. and X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (No. E2024209062), the Operation Expenses for Universities’ Basic Scientific Research of Hebei Province (No. JQN2022008), the Postgraduate Innovation Funding Project of Hebei Province (No. CXZZBS2022112), and the Tangshan Science and Technology Plan Funding Project (No. 24130206C)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mills, K.C. Structure and properties of slags used in the continuous casting of steel: Part 1. Conventional mould powders. ISIJ Int. 2016, 56, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.M.d.S.M.; Tavernier, H.; dos Santos Junior, T.; Vernilli, F. Design and analysis of fluorine-free mold fluxes for continuous casting of peritectic steels. Materials 2024, 17, 5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; He, S.P.; Xu, J.F.; Huo, X.L.; Wang, Q. Properties of high basicity mold fluxes for peritectic steel slab casting. ISIJ Int. 2012, 19, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbl, N. New mold slag compositions for the continuous casting of soft steels. Steel Res. Int. 2021, 93, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.C.; Fox, A.B. The role of mould fluxes in continuous casting-so simple yet so complex. ISIJ Int. 2003, 43, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Research on mold flux for hypo-peritectic steel at high casting speed. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2007, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.W.; Blazek, K.; Frazee, M.; Yin, H.; Park, J.H.; Moon, S.W. Assessment of CaO-Al2O3 based mold flux system for high aluminum TRIP casting. ISIJ Int. 2003, 53, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Yu, X. ; Controlling Step Variation in the Reaction of High-Al Steel and CaO-SiO2-Type Mold Flux. Metall Mater Trans B 2024, 55, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cheng, C.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Huang, X.; Jin, Y. Effect of MnO on physicochemical properties of CaO-Al2O3-based mold flux of high-Mn steel for ultra-low-temperature applications. Metall Mater Trans B 2025, 56, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costaa, I.T.; Carvalho, C.S.; Oliveira, J.R.; Vieirab, E.A. Physical properties characterization of a peritectic mold flux formed from the addition of calcitic marble residue in the commercial one. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhao, X.; Chen, S.; Shi, C.; Yang, C.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y. Development and application of mold flux for high-speed continuous casting of high-carbon steel billets. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2025, 32, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhai, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W. A comparison study on interfacial properties of fluorine-bearing and fluorine-free mold flux for casting advanced high-strength steels. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2022, 29, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J; Chen, D.; Long, M.; Duan, H. Transient flow and mold flux behavior during ultra-high speed continuous casting of billet. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 3984.

- Kamaraj, A.; Tripathy, S.; Chalavadi, G.; Sahoo, P.P.; Misra, S. Characterization and assessment of mold flux for continuous casting of liquid steel using an inverse mold simulator. Steel Res. Int. 2022, 93, 2100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechu, K.; Slater, C.; Santillana, B.; Sridhar, S. The use of infrared thermography to detect thermal instability during solidification of peritectic steels. Mater. Charact. 2019, 154, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanao, M.; Kawamoto, M.; Yamanaka, A. Influence of mold flux on initial solidification of hypo-peritectic steel in a continuous casting mold. ISIJ Int. 2012, 52, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; He, S.; Wang, Q.; Pistorius, P.C. Structure of solidified films of mold flux for peritectic steel. Metall Mater Trans B 2017, 48, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Long, M.J.; Chen, D.F.; Wu, S.X.; Tang, P.M.; Liu, S.; Duan, H.M.; Yang, J. Investigations of the peritectic reaction and transformation in a hypoperitectic steel: Using high-temperature confocal scanning laser microscopy and differential scanning calorimetry. Mater. Charact. 2019, 156, 109870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Han, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, D. Influence of mineralogical structure of mold flux film on heat transfer in mold during continuous casting of peritectic steel. Materials 2022, 15, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, J.L.; Medeiros, S.L.S.; Matos, K.T.; Azevedo, C.A.; Maranhão, E.A.; Ferreira, J.A.C. Designing mould fluxes to prevent longitudinal cracking for peritectic steel slab casting. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2023, 50, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Luo, H.; Wang, W.; Yan, X.; Wu, H. Effect of Al2O3/Na2O ratio and MnO on high-temperature properties of mold flux for casting peritectic steel. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2022, 29, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhou, L.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Si, X. Rapid Prediction of the viscosity of mold flux by ensemble tree models. Metall Mater Trans B 2025, 56, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wen, G.; Tang, P.; Lu, Y.; Yang, H. Effect of shape parameters on the melting behavior of hollow granular mold flux for continuous casting. Metall Mater Trans B 2023, 54, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, L. Influence of substituting B2O3 with Li2O on the viscosity, structure, and crystalline phase of low-reactivity mold flux. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2023, 30, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Wen, G.; Ding, Z.; Tang, P.; Liu, Q. Effect of Shear Stress on Isothermal Crystallization Behavior of CaO-Al2O3-SiO2-Na2O-CaF2 Slags. Materials 2018, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazim, M.A.; Emdadi, A.; Sander, T.; Malley, R. The Effect of mold flux wetting conditions with varying crucible materials on crystallization. Materials 2025, 18, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, W.L.; Sohn, I.L. Crystallization behavior and structure analysis for molten CaO-SiO2-B2O3 based fluorine-free mold fluxes. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2019, 511, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Q.; He, S.; Wang, Q. Effect of substituting Na2O for SiO2 on the non-isothermal crystallization behavior of CaO-BaO-Al2O3 based mold fluxes for casting high Al steels. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Long, S.; Luo, W.; Li, X.; Tu, C.; Na, Y.; Xu, J. Crystallization of slag films of CaO-Al2O3-BaO-CaF2-Li2O-based mold fluxes for high-aluminum steels continuous casting. Materials 2023, 16, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Han, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Wang, Y. Effects of mineral raw materials on melting and crystalline properties of mold flux and mineralogical structures of flux film for casting peritectic steel slab. ISIJ Int. 2023, 63, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Leng, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, J. Crystallization products and structural characterization of CaO-SiO2-based mold fluxes with varying Al2O3/SiO2 ratios. Materials 2019, 12, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Han, X.L.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.N. Effect of mineralogical structure of flux film on slab quality for medium carbon steel. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2018, 71, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, M.; Lai, F.; Li, J. Effect of cooling rate on phase and crystal morphology transitions of CaO-SiO2-based systems and CaO-Al2O3-based systems. Materials 2019, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; Yao, M. Simulation study on transient periodic heat transfer behavior of meniscus in continuous casting mold. Metall Mater Trans B 2023, 54, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L. Crystallization characteristics and heat transfer control of mould flux for peritectic steel continuous casting. ISIJ Int. 2022, 62, 1673. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).