Perspectives

Numerous molecular studies on the mechanisms of cancer drug resistance have identified components of the Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway as drivers of drug resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy in mouse models and in clinical data.

Multiple mechanisms contributing to TGF-β driven cancer drug resistance have been reported, including promotion of epithelial to mesenchymal transformation (EMT) and stemness, activation of cancer associated fibroblasts, and other potent immunosuppressive activities on and by diverse immune cell types.

Efforts to target TGF-β in the clinic have had limited success, in part due to activities on normal cells. Further study of interacting pathways and the critical cell types involved are warranted to develop nuanced therapies that target TGF-β driven drug resistance mechanisms, with the prospect for new drug designs, optimized drug sequencing, and early intervention, for prevention of drug resistance.

1. Introduction

The development of cancer drug resistance is an intractable problem for oncologists, and the major cause of cancer deaths. Tumors may be innately drug resistant or resistance may be acquired in response to therapeutic treatment. Resistance to therapies that target one specific kinase or kinase pathway may develop by somatic mutation of the drug target or recruitment of alternative signaling pathways that bypass that target [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, apart from these highly target-specific molecular mechanisms, innate or acquired drug resistance may occur through more generalized mechanisms resulting from the heterogeneity and plasticity of tumor cells and their microenvironment. In the early 1990’s there was evidence that elevated Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β) contributes to tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer [

5,

6,

7], and in 2012, using an

RNAi screening platform, Huang et al showed that loss of MED12 that normally suppresses expression of the type II TGF-β receptor (TGFBR2), induces chemotherapy resistance in a variety of cancer cell lines originating from distinct organ sites [

8]. Such TGF-β signaling mediated resistance was demonstrated in response to chemotherapy agents such as cisplatin and 5-fluorodeoxyuridine, as well as to targeted therapeutics including the tyrosine kinase inhibitors crizotinib, gefitinib, and erlotinib [

8].

Acquisition of drug resistance develops not only in response to chemotherapy, but also to radiotherapy or immunotherapy. This can evolve gradually through two stages; The first stage involves alterations in tumor cell plasticity, such as partial Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transformation (EMT), up-regulation of stem cell markers and stress responses, and downregulation of antigen presentation machinery [

9,

10,

11]. The second phase occurs in response to long-term cytotoxic treatment that debulks the tumor but leads to persistence of epigenetically altered drug tolerant persister cells (DTPs) that may remain dormant in the body for years [

12,

13,

14,

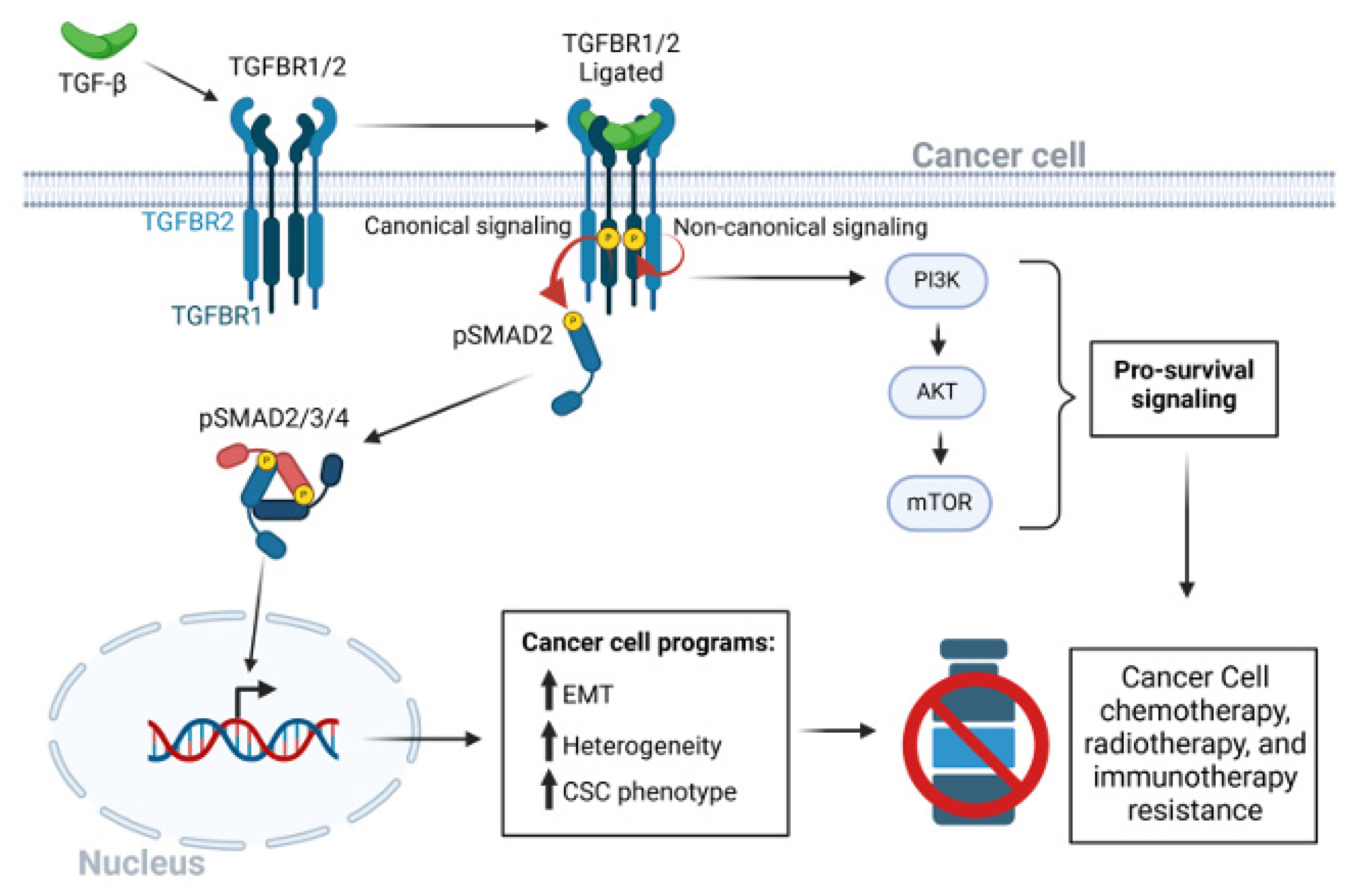

15]. Elevated flow through the TGFβ signaling pathway (

Figure 1) is often a major contributor to the first phase in this process which is the focus of this short review. Here, we will emphasize the potential importance of targeting TGF-β signaling early during drug sequencing to prevent the development of DTPs.

Figure 1.

The TGF-β signaling pathway in cancer drug resistance. After dimeric TGF-β ligation to the heterotetrameric TGF-β receptor complex of type I and type 2 receptors, a conformation change in TGFBR2 leads to kinase activation of TGFBR1. TGFBR1 phosphorylates and activates the canonical receptor associated SMAD2 and SMAD3 pathways. The hexameric SMAD2/3/4 complex enters the nucleus to regulate transcriptional programs that lead to EMT, CSC phenotypes, and tumor cell heterogeneity. Various non-canonical pathways may be triggered independent of the serine-threonine kinase activity of TGFBR1. Activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis promotes cancer cell survival. Red circular arrows indicated the serine threonine TGFBR-SMAD phosphorylation cascade. Thin black arrows indicate downstream consequences. Bold black arrows indicate upregulation of processes.

Figure 1.

The TGF-β signaling pathway in cancer drug resistance. After dimeric TGF-β ligation to the heterotetrameric TGF-β receptor complex of type I and type 2 receptors, a conformation change in TGFBR2 leads to kinase activation of TGFBR1. TGFBR1 phosphorylates and activates the canonical receptor associated SMAD2 and SMAD3 pathways. The hexameric SMAD2/3/4 complex enters the nucleus to regulate transcriptional programs that lead to EMT, CSC phenotypes, and tumor cell heterogeneity. Various non-canonical pathways may be triggered independent of the serine-threonine kinase activity of TGFBR1. Activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis promotes cancer cell survival. Red circular arrows indicated the serine threonine TGFBR-SMAD phosphorylation cascade. Thin black arrows indicate downstream consequences. Bold black arrows indicate upregulation of processes.

2. TGFβ-Stimulated Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transformation Drives Chemotherapy Resistance Through Multiple Mechanisms

TGF-β is a major inducer of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) [

16,

17,

18], the cellular process by which epithelial cells gradually reduce or switch off expression of epithelial markers and acquire mesenchymal characteristics [

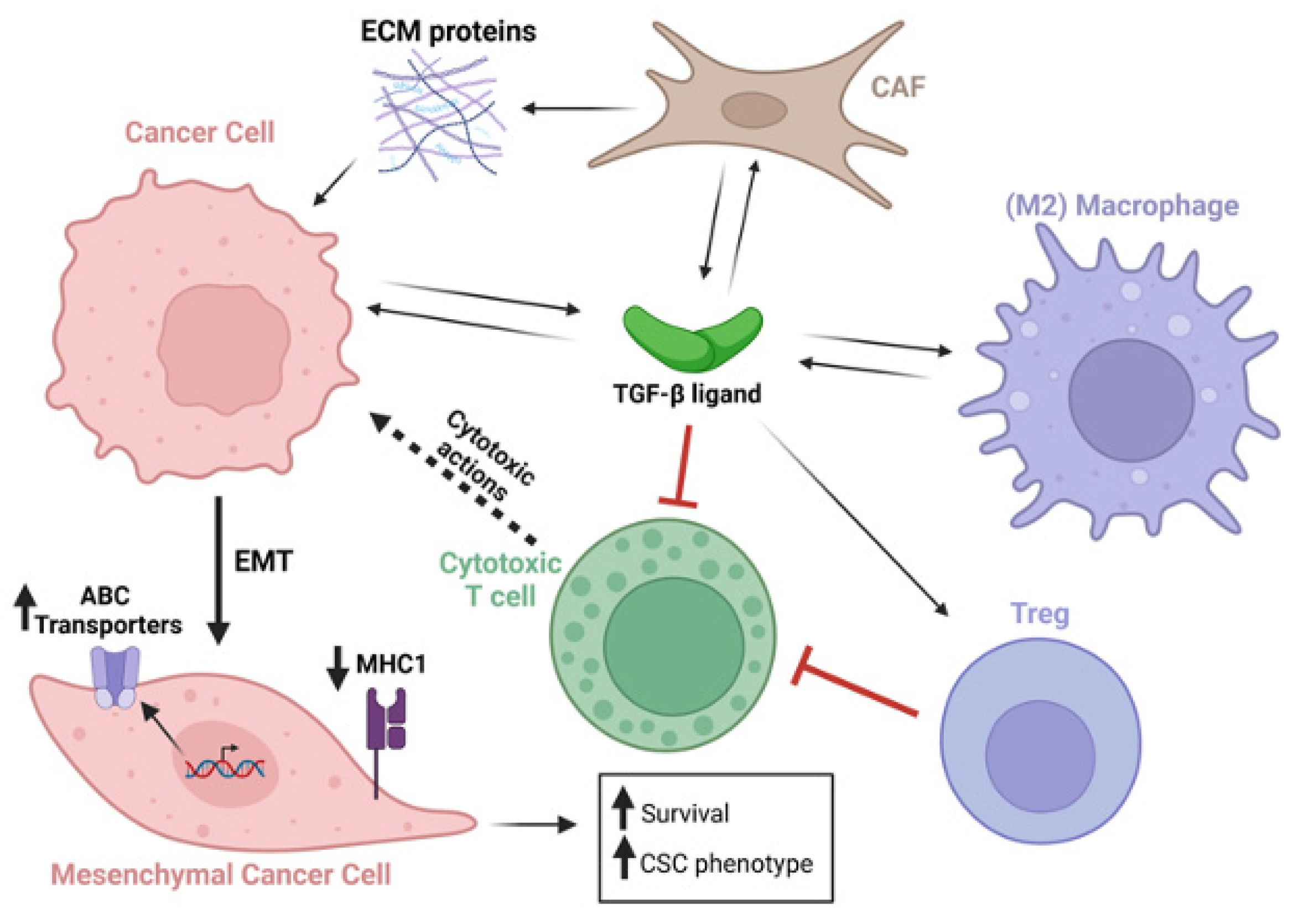

19] (

Figure 2). EMT of tumor cells is not a simple biphasic switch but requires gradual molecular changes that can eventually cause complete loss of expression of epithelial markers, and transition to a myofibroblast-like tumor cell [

19]. During this change in cellular phenotype, multiple molecular changes in gene and protein expression occur, and epigenetic changes stabilize this phenotype. As a result, cells acquire several functions that can potentially suppress drug sensitivity. Oshimori et al (2015) provided evidence that TGF-β signaling promotes tumor heterogeneity and elevates glutathione metabolism that protects cells from oxidative stress, thereby promoting cisplatin resistance in a murine squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) model [

20]. In another study that utilized a triple transgenic mouse model to track EMT in lung cancer cells

in vivo, cells that had transitioned to a mesenchymal state were found to be resistant to cyclophosphamide, and

in vitro experiments showed that TGF-β stimulation increased the number of mesenchymal cells, further increasing the links between TGF-β, EMT, and chemotherapy resistance [

21].

TGF-β-induced EMT causes elevated expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters that encode drug efflux pumps which lower intracellular drug concentrations. Both TGF-β and activin expression are frequently elevated in the tumor and its microenvironment to drive activation of pSMAD2/3/4 signaling, and the nuclear SMAD2/3/4 complex binds and activates genes encoding a variety of ABC proteins. In triple negative breast cancer, resistance to a Cyclin-Dependent Kinase type 7 (CDK7) inhibitor caused elevated phospho-SMAD3 binding to, and activation of, the

ABCG2 gene, and drug resistance was reversed by genetic knockdown of

ABCG2, pharmacological blockade of TGF-β/activin type I receptors, or by downregulation of SMAD4 [

22]. In ovarian cancers, TGF-β signaling has been shown to upregulate the homeobox transcription factor PITX2A/B, that binds and up regulates

ABCB1 resulting in chemotherapy resistance [

23]. In A549 lung cancer cells, de Costa et al (2023) found that TGF-β-induced EMT increased expression of the ABCB1 and ABCC1 drug efflux pumps, as well as increased cellular detoxification activity of the ABCC1 pump [

24]. ABCC1 expression is also elevated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) by TGF-β induction of the transcription factor ATF4 that binds the

ABCC1 gene promoter [

25] (

Figure 2). Notably, ABCC1 exports glutathionylated substrates causing resistance of various malignancies to anti-cancer drugs, including gemcitabine and cisplatin [

25,

26,

27].

Figure 2.

TGF-β secreted from multiple cell types acts on a plethora of cell types within the tumor and tumor microenvironment. TGF-β stimulated cancer cells undergo EMT, which upregulates ABC transporters, downregulates MHC type 1 expression, and increases cancer cell survival and expression of cancer stem cell genes. Black arrows indicate secretion of TGF-β ligands, ECM proteins, or actions of these factors on cells. Dotted black arrow indications cytotoxic activity emanating from cytotoxic T cells. Red connecters indicate inhibitory activity. Long bold black arrow indicates cancer cell epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). Short bold black arrows indicate upregulation or downregulation as indicated.

Figure 2.

TGF-β secreted from multiple cell types acts on a plethora of cell types within the tumor and tumor microenvironment. TGF-β stimulated cancer cells undergo EMT, which upregulates ABC transporters, downregulates MHC type 1 expression, and increases cancer cell survival and expression of cancer stem cell genes. Black arrows indicate secretion of TGF-β ligands, ECM proteins, or actions of these factors on cells. Dotted black arrow indications cytotoxic activity emanating from cytotoxic T cells. Red connecters indicate inhibitory activity. Long bold black arrow indicates cancer cell epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). Short bold black arrows indicate upregulation or downregulation as indicated.

Not only can EMT drive tumor cell resistance to chemotherapies, but also to immunotherapies. TGF-β-induced EMT was shown to down regulate multiple components of the tumor cell neo-antigen presentation machinery, including MHC1 itself, as well as downregulation of β-2 microglobulin and the tumor antigen processing enzymes, TAP1 and TAP2 [

28]. More details on mechanisms recently came from studies in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) undertaken by Tan et al (2023), showing that increased TGF-β signaling caused phosphorylation of UHRF1 (

ubiquitin-like with plant

homeodomain and

ring

finger domains 1). This resulted in mis-localization of UHRF1 within the cytoplasm, causing binding to MHC1 that is consequently ubiquitinated and degraded through the proteosome [

29]. Inhibition of TGF-β may therefore potentiate immunotherapies, including immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), not only by activating immune cells directly, but by enhancing the visibility of the tumor cell to the adaptive immune system by elevating antigen presentation (

Figure 2).

3. Induction of Drug-Resistant Cancer Stem Cells by TGF-β

EMT, or at least a partial EMT, has been postulated as a route for tumor cells to acquire the properties of cancer stem cells (CSCs) [

10]. The cancer stem cell theory proposes that tumor cells arrange themselves into hierarchies within the tumor microenvironment (TME), at the top of which reside unique CSC clones that populate the tumor with their heterogenous progeny. Critical to CSC theory is that CSCs are required to seed new tumors, implicating CSCs as a major driver of tumor progression and metastasis [

10]. CSCs are also thought to contribute to chemotherapy resistance [

30], although exactly how this happens is still under investigation.

In recent times, Katsuno et al (2019) found that chronic TGF-β ligand stimulation resulted in a stabilized EMT in immortalized human mammary epithelial cells which included a stem cell like state and resistance to the commonly employed chemotherapy agents, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and cyclophosphamide [

31]. The authors further found that chronic TGF-β exposure led to this CSC-like phenotype through upregulation of AKT-mTOR signaling, and pharmacological mTOR inhibition attenuated TGF-β stimulated chemoresistance [

31]. Other studies identified additional mechanisms by which TGF-β signaling contributes to the CSC state in different organ-specific cancer sites. Loss of the tumor suppressor, MYOCD, enhances the stemness of NSCLC, which results in part by loss of PRMT5/MEP500 mediated epigenetic silencing of the

TGFBR2 gene. MYOCD binds to the

TGFBR2 gene promoter and recruits PRMT5/MEP500 [

32]. Similarly, up regulation of the type 1 TGFβ receptor is implicated in driving the CSC state and chemotherapy resistance in hepatocellular cancer. A CRISPR activation screen identified TGFBRAP1, a TGFβR1 binding protein, as supporting hepatocellular CSC formation and drug resistance. TGFBRAP1 stabilizes TGFβR1 by competing with the E3 ubiquitin ligase SMURF, thus blocking TGFβR1 polyubiquitination and degradation. Moreover, a positive feedback loop stabilizes the CSC phenotype through upregulation of TGFBRAP1 by TGFβ signaling [

33]. Elevated TGF-β signaling through both SMAD and non-SMAD pathways (

Figure 1) also increases expression of PITX2 to drive stemness in ovarian cancer [

23].

Taken together, TGF-β signaling may promote cancer resistance to chemotherapy by inducing tumor heterogeneity and cellular plasticity of cancer cells through EMT cellular programs, and EMT may increase the pool of CSCs while also providing pro-survival signaling within cancer cells, such as stimulation of the AKT-mTOR pathway, that increases tumor resistance to commonly used chemotherapy therapies used in the clinic.

4. TGF-β-Induced Pro-Survival Signaling in Tumor Cells is Elicited Through SMAD and Non-SMAD Pathways

Although there are certainly anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects associated with TGF-β signaling in normal epithelial cells [

34,

35,

36], it seems that at least some carcinomas dispose of this negative growth regulatory arm (after oncogene activation or loss of tumor suppressors) and take advantage of the pro-survival signaling pathways triggered by the TGF-β receptor complex. SMAD3 was recently identified in a CRISPR screen as a functional target for genes that promote MEKi resistance. An activated SMAD3 signature increased during development of BRAFi resistance and was high in DPCs and in tumor cells during relapse. SMAD3 appeared to drive resistance to MEKi in melanoma by directly up regulating the EGFR and AXL genes [

37]. Nevertheless, the outcome of TGF-β action on driving apoptosis

versus cell survival is context-dependent, and a recent study demonstrated that elevated TGF-β1 can synergize with MEK inhibition to

stimulate apoptosis in melanoma [

38].

As discussed above, AKT signaling plays a prominent role in terms of “non-canonical” TGF-β signaling pathways that directly promote cell survival downstream of TGF-β ligand/receptor engagement [

31]. TGF-β stimulates AKT signaling through PI3K activation, and PI3K and AKT inhibitors have been extensively tested in pre-clinical models. These drugs, that are currently being assessed in clinical trials [

39], may be applicable in reducing drug evading effects elicited by excess TGF-β [

40]. A recent report [

41] suggests that in PDAC, TGF-β-induced AKT activation, causes accumulation of specific neutral lipid species that contribute to gemcitabine resistance. This study showed that inhibition of TGF-β2, using the drug imperatorin, a naturally occurring coumarin, lead to synergistic tumor killing when used with gemcitabine in both

in vitro and

in vivo settings [

42].

TGF-β signaling may support other cellular pro-survival factors to drive chemotherapy resistance, such as by upregulation and maintenance of elevated B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) expression in bone metastatic prostate cancer [

43]. The authors of this study found that TGF-β promotes resistance to docetaxel through acetylation of the transcription factor KLF5, which in turn increases BCL-2 gene transcription. They additionally found that TGF-β prevented docetaxel induced degradation of BCL-2 [

43].

To conclude, TGF-β also promotes cancer cell survival and chemotherapy resistance through SMAD and non-SMAD signaling pathways, as well as through upregulation of proteins, such as EGFR, AXL and Hedgehog signaling from which there may be many downstream cellular effects that promote chemoresistance, such the acetylation of KLF5 that causes increased BCL-2 expression, or the accumulation of lipid species that promote cancer cell chemotherapy resistance.

5. TGF-β Signaling Blockade, an Achilles Heel for Genotoxic Therapies Through Suppression of DNA Damage Repair Pathways

Radiotherapy and platinum-based chemotherapy kill tumor cells by inducing DNA damage including single and double strand DNA (dsDNA) breaks that lead to mutations, cytogenetic rearrangements, and ultimately to tumor cell death [

44]. These therapeutic modalities also induce expression and activation of TGF-β1 [

45,

46] that can result in innate drug resistance, as well as induction of fibrosis that reinforces drug resistance in the tumor by providing a source of activated CAFs (see below). Notably, in response to DNA damage elicited by radiotherapy or chemotherapy, a number of DNA Damage Repair (DDR) pathways are activated that, in one way or another, limit DNA damage to suppress tumor cell death, ultimately reducing the efficacy of these genotoxic therapies [

47]. Importantly, TGF-β signaling has been shown to protect the genome from DNA damage by potentiating several DDR pathways that are activated by dsDNA breaks [

48,

49,

50]. BRCA1/Rad51-mediated homologous recombination repair (HRR) is potentiated by TGF-β-mediated up regulation of BRCA2 [

51]. DNA repair through the Non-Homologous End-Joining (NHEJ) pathway is also stimulated by TGF-β through elevated expression and nuclear translocation of DNA ligase IV (LIG4) [

52,

53]. Finally, in the absence of TGFβ signaling a less efficient Alt-EJ repair pathway is preferentially utilized

via activity of LIG1 (DNA ligase 1), PARP1, and POLQ [

51], accentuating the effects of these therapies [

49,

52,

54,

55].

6. TGF-β and Tumor Immunity

Since 2013, when the major

Science breakthrough of the year was immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) for cancer therapy [

56], many labs focused their efforts on identifying the mechanisms of resistance to such immunotherapies. Apart from a low mutation load, which is unfavorable to immunotherapy responsiveness, transcriptomics analyses found that markers of EMT, ECM and TGF-β signaling associated with ICB resistance [

57,

58,

59]. Strong empirical evidence in preclinical models then showed that blockade of TGF-β signaling may alleviate resistance to immunotherapy through activity on multiple immune cell types within the tumor and draining lymph nodes [

40]. Indeed, TGF-β is a potent immunosuppressor of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and NK cells and tends to polarize CD4+ T helpers and myeloid cells away from an anti-tumor phenotype towards an immunosuppressive phenotype [

40,

60,

61]. Consistent with the idea that TGF-β signaling stimulates immune suppressing cell types, Dodagatta-Marri et al (2019) not only confirmed in their SCC model that anti-PD1 therapy enhances cytotoxic CD8+ T cell infiltration and activation, but notably also found an increased fraction of CD4+ T cells that are immunosuppressive FOXP3+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Logically, an anti-TGF-β blocking antibody was able to synergistically enhance anti-PD1 therapy through attenuation of this drug-induced increase in immunosuppressive intratumoral Tregs [

28], and consequent further elevation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cell activity [

62].

More recently, another group examined transcriptomes from recurrent gynecologic cancer patients treated with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies. They too, found a TGF-β driven genetic signature that predicted immunotherapy resistance as indicated by reduced overall and progression free survival [

63]. As in previous studies in other cancers [

40], the immune cell types that correlate with high TGF-β signaling in these ovarian cancers also correlated with worse overall survival, including Tregs, M2 macrophages, and eosinophils. Interestingly, in that study, naïve CD4+ T cells along with follicular helper T cells were associated with high TGF-β signaling signaures, possibly representing a TGFβ-mediated suppression of T cell differentiation, but the mechanisms by which naïve CD4+ T cells and follicular helper T cells contribute to poorer overall survival in response to ICB remain to be deciphered [

63]. The plethora of mechanisms whereby TGF-β signaling dampens immune responses to ICB has been reviewed extensively [

40,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68], and readers are advised to refer to these reviews for details of this important TGF-β activity in mediating immunotherapy resistance.

7. Contribution of TGF-β to Tumor Microenvironment (TME)-Driven Therapy Resistance

In addition to inducing tumor cell plasticity, cancer cell heterogeneity, and promoting cancer stemness through EMT, TGF-β has profound effects on the tumor microenvironment (TME) through regulation of fibroblasts and their transformation into cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) that impacts both the tumor cell [

40,

69,

70] as well as recruitment and cellular functions of diverse immune cell types within the tumor [

40,

59,

71,

72].

Several laboratories reported that TGF-β driven transcriptomic signatures associate with the presence of CAFs as well as with immunosuppressive blood cells, such as M2 macrophages, T regulatory cells (Tregs), and myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). This signature associates with decreased responses to ICB treatment, such as atezolizumab (anti-PDL-1) or pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1), in patients with Head and Neck (HN) SCC [

73], melanoma [

74], urothelial carcinoma [

59], gynecological cancers [

63], and breast cancer [

75].

Across many solid tumor types, CAFs are known to contribute to tumor progression [

40] and chemotherapy resistance [

76], which can at least partially be attributed to their secretion of TGF-β ligands, predominantly TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 [

77]. CAFs are a major contributor to elaboration of ECM (extracellular matrix) proteins within the TME [

78], a feature stimulated by TGF-β ligands. High levels of ECM production generate physical and chemical barriers to immune cell infiltration [

59,

72], as well as physical tension within the tumor that correlates with elevated TGF-β signaling and chemotherapy resistance, as observed in gastric cancer [

79]. Dominguez et al (2019) found that TGFβ stimulated a major subset of CAFs, identified by expression of Leucine-Rich-Repeats-Containing Protein 15, LRRC15, in PDAC and other cancers, and a high TGFβ CAF signature correlated with poor patient survival in an immunotherapy clinical trial [

80]. In a later study, the same group found that LRRC15

+ CAFs promote tumor progression and resistance to anti-PDL1 treatment via suppressing effector T cell function in various mouse tumor models [

81]. In line with these studies on CAFs in PDAC immunotherapy resistance, a subsequent study from an independent group found that CAFs in esophageal cancer may also play a role in immunotherapy resistance by upregulating their expression of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) [

82], which when ligated to T cell-PD-1 is known to induce T cell anergy and apoptosis, the premise for ICB therapies.

In ovarian cancer, which metastasizes to the peritoneal cavity, tumor-derived TGF-β induces osteopontin expression by mesothelial cells lining the peritoneal cavity. Secreted osteopontin in turn induces activation of the CD44 receptor, PI3K/AKT signaling and ABC drug pumps in tumor cells, contributing to chemotherapy resistance. Notably, targeting osteoponin in ovarian cancer models improved cisplatin efficiency of tumor killing [

26]. In concordance with these studies showing that CAFs and macrophages promote chemo- and immunotherapy resistance, a more recent study using co-culture experiments showed that CAFs and TAMs (tumor associated macrophages) promote neuroblastoma tumor cell survival through complex parallel mechanisms. Secretion of IL-6 and s-IL6Rα by “mesenchymal stromal cells”,

aka MSCs/CAFs, promotes monocyte survival, whilst TGF-β secretion from MSCs and tumor cells differentiates monocytes toward M2 macrophages [

83]. The authors demonstrated that all three cell types secrete TGF-β1 ligand, which in turn was shown to inhibit cytotoxic NK cell function in vitro [

83]. M2 macrophages contribute to chemotherapy resistance as a source of TGF-β ligands, which in turn promotes a cancer stem cell-like phenotype that confers cisplatin resistance as observed in studies on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [

84].

In melanoma, Xu et al (2025) found that CD133+PDL-1+ tumor stem like cells, that synthesize higher TGF-β quantities than their CD133-PDL-1- counterparts, develop a local niche characterized by high ECM elaboration. This in turn prevents recruitment and killing of tumor cells by adoptively transferred macrophages due to prevention of macrophage migration through the stiffened ECM. Moreover, locally high TGF-β prevents full differentiation of macrophages to a phagocytic phenotype for tumor cell clearance [

72]. Finally, a recent study has shown that TGF-β trapped in Neutrophil “NETs” (Neutrophil extracellular traps) promotes resistance to two different chemotherapy regimens (cisplatin or combinatorial adriamycin plus cyclophosphamide) [

85]. The authors found that in breast carcinoma, neutrophil “NETs” are formed within the tumor in response to chemotherapy, due to activation of the inflammasome by ATP released from dying cancer cells. This causes release of IL-1β that drives NET elaboration. Latent TGF-β released by tumor cells gets trapped in NETs through binding to integrin αvβ1 and is activated by NET-trapped MMPs. Activated TGF-β released from the NETs thus drives drug resistance in the tumor cells [

85]. To conclude, clearly TGF-β signaling has a profound effect on non-malignant cell types in the tumor microenvironment through transformation of fibroblasts into CAFs, and multiple immunosuppressive effects on myeloid cells. These immunosuppressive cell types promote immune evasion and survival of malignant tumor cells through further secretion of TGF-β ligands, as in the case of M2 macrophages, thus attenuating the efficacy of both chemo- and immune-therapies.

8. Conclusions

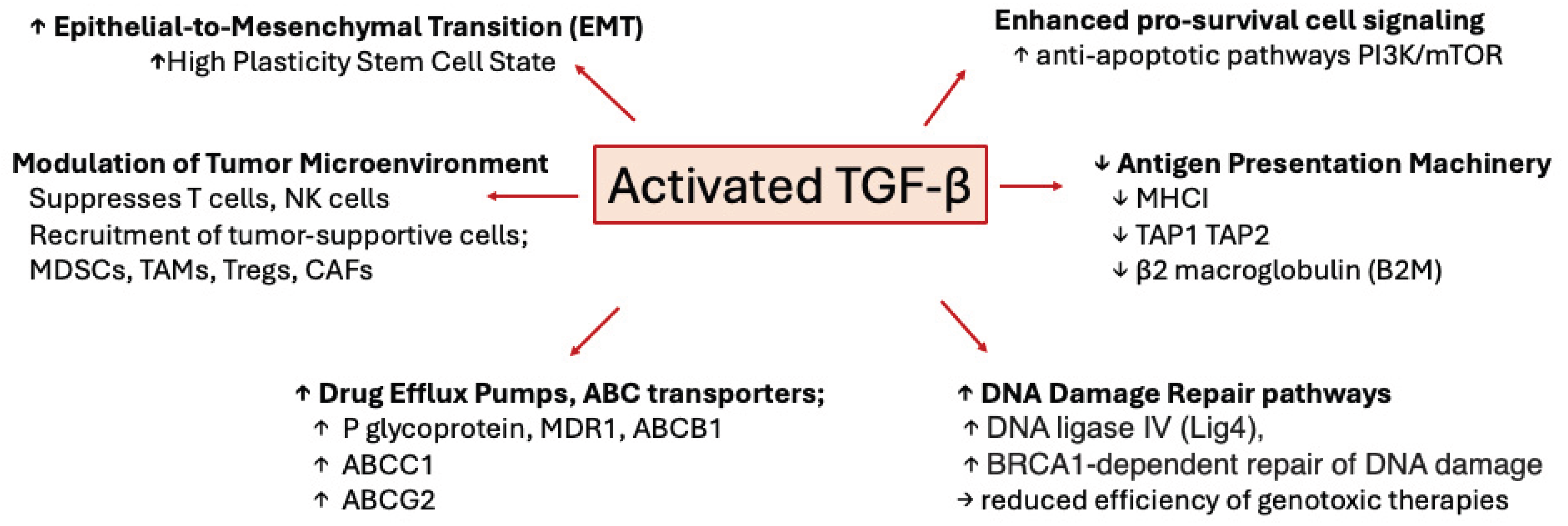

Recent studies, supported by publications from decades past, have clearly demonstrated that aberrant upregulation and/or activation of TGFβ signaling in many cancers contribute to resistance to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy through a plethora of mechanisms (

Figure 3). TGFβ ligands, acting on cancer cells, drive phenotypic as well as molecular changes, inducing cancer cell heterogeneity and a drug-resistant phenotype that is associated with EMT, stemness, upregulation of drug efflux pumps, support of DNA Damage Repair mechanisms, pro-survival signaling, as well as decreased neoantigen presentation. Furthermore, TGFβ also acts on tumor-associated immune and non-immune cell types alike, providing protection of cancer cells from cytotoxic immune cells by elaboration of a stiff extracellular matrix and polarization of TME and immune cells towards immunosuppressive phenotypes (

Figure 2). These studies have highlighted TGFβ signaling as a major driver of resistance to currently used cancer therapies and warrant the further exploration of the molecular and cellular consequences of TGFβ stimulation of cancer and stromal cells with the goal of discovering and designing new cancer treatment schemes.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Mechanisms of TGF-β mediated drug resistance. Cartoon depicting various mechanisms whereby TGF-β promotes resistance to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Mechanisms of TGF-β mediated drug resistance. Cartoon depicting various mechanisms whereby TGF-β promotes resistance to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy.

9. Future Directions

Targeting TGF-β signaling in cancer continues to be of interest in drug development, but more nuanced approaches are required due to the widespread pleiotropic activities of TGF-β in many tissues and cell types. Targeting components of the TGFβ pathway that show more restricted expression, such as integrin β8 which is expressed at highest levels in intratumoral CD4+CD25+ Tregs and tumor cells

per se, may be one avenue towards success [

62,

86,

87]. Another approach is the use of bispecific drugs that target TGF-β inhibition to specific cell types, such as a bispecific antibody composed of TGF-β-neutralizing TGFBR2 extracellular domain fused to ibalizumab, a non-immunosuppressive CD4 antibody [

71], in order to specifically target TGFβ signaling in CD4+ T cells. Bintrafusp alfa has so far shown limited success in the clinic; This bispecific drug blocks both PDL-1 and TGF-βs and importantly causes drug homing to the tumor [

67]. Another consideration is targeting proteins that synergize with the TGF-β pathway to drive drug resistance, for example targeting S100A4 or NFAT5 to prevent PDAC resistance to the Kras inhibitor, G12Di-MRTX1133 [

88], or the use of the SRC inhibitor, dasatinib, to target a SRC-SLUG-TGF-β2 chemoresistance pathway in triple negative breast cancer [

89]. Although less amenable as drug targets, inhibition of TGFBRAP1 or PRMT5/MEP500 to alleviate drug resistance in NSCLC [

32], or ATF4 inhibition to relieve gemcitabine resistance in PDAC [

25], have been proposed. Importantly, identifying and optimizing the best combinatorial therapies for use with TGF-β signaling blockade, and determining the ideal sequential dosing strategies for each drug combination, remain to be fully investigated. Although difficult to achieve in a clinical trial setting, the use of combinatorial TGF-β blockade

early during first line therapy may be important to realize the full potential of blocking this pathway to prevent development of drug resistance.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the writing and artwork.

Funding

Work relevant to this review was supported by NIH grants, 1R01CA285426-01 to RJA, and 5T32AI007334-35 to JPH.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results.

Abbreviations

| ABC |

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette |

| CAF |

cancer-associated fibroblast |

| CSC |

cancer stem cells |

| DDR |

DNA damage response |

| ECM |

Extracellular Matrix |

| EMT |

Epithelial Mesenchymal Transformation |

| ICB |

Immune Checkpoint Blockade |

| MDSC |

Myeloid derived suppressor cell |

| NET |

Neutrophil extracellular trap |

| NK |

Natural Killer |

| NSCLC |

non-small cell carcinoma |

| PD-1 |

Programmed Death -1 |

| PDAC |

Pancreatic ductal carcinoma |

| SCC |

Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| TGF-β |

Transforming growth factor β |

References

- Sergina NV, Rausch M, Wang D, Blair J, Hann B, Shokat KM, et al. Escape from HER-family tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy by the kinase-inactive HER3. Nature. 2007;445(7126):437–41. https://doi.org:nature05474 [pii] 10.1038/nature05474.

- Carlomagno F, Guida T, Anaganti S, Provitera L, Kjaer S, McDonald NQ, et al. Identification of tyrosine 806 as a molecular determinant of RET kinase sensitivity to ZD6474. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16(1):233–41. https://doi.org:10.1677/erc-08-0213.

- Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483(7387):100–3. https://doi.org:10.1038/nature10868 nature10868 [pii].

- Ahronian LG, Sennott EM, Van Allen EM, Wagle N, Kwak EL, Faris JE, et al. Clinical Acquired Resistance to RAF Inhibitor Combinations in BRAF-Mutant Colorectal Cancer through MAPK Pathway Alterations. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(4):358–67. https://doi.org:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1518.

- Thompson AM, Kerr DJ, Steel CM. Transforming growth factor beta 1 is implicated in the failure of tamoxifen therapy in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1991;63(4):609–14. https://doi.org:10.1038/bjc.1991.140.

- Arteaga CL, Carty-Dugger T, Moses HL, Hurd SD, Pietenpol JA. Transforming growth factor beta 1 can induce estrogen-independent tumorigenicity of human breast cancer cells in athymic mice. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4(3):193–201.

- Arteaga CL, Koli KM, Dugger TC, Clarke R. Reversal of tamoxifen resistance of human breast carcinomas in vivo by neutralizing antibodies to transforming growth factor-beta. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(1):46–53.

- Huang S, Holzel M, Knijnenburg T, Schlicker A, Roepman P, McDermott U, et al. MED12 controls the response to multiple cancer drugs through regulation of TGF-beta receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;151(5):937–50. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.035S0092-8674(12)01296-2 [pii].

- Singh A, Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4741–51.

- Shibue T, Weinberg RA. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(10):611–29. https://doi.org:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.44.

- Dongre A, Weinberg RA. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(2):69–84. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41580-018-0080-4.

- Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, Quinlan MP, Takahashi F, Maheswaran S, et al. A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell. 2010;141(1):69–80. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027.

- Vinogradova M, Gehling VS, Gustafson A, Arora S, Tindell CA, Wilson C, et al. An inhibitor of KDM5 demethylases reduces survival of drug-tolerant cancer cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12(7):531–8. https://doi.org:10.1038/nchembio.2085.

- Guler GD, Tindell CA, Pitti R, Wilson C, Nichols K, KaiWai Cheung T, et al. Repression of Stress-Induced LINE-1 Expression Protects Cancer Cell Subpopulations from Lethal Drug Exposure. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(2):221–37 e13. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.002.

- Hangauer MJ, Viswanathan VS, Ryan MJ, Bole D, Eaton JK, Matov A, et al. Drug-tolerant persister cancer cells are vulnerable to GPX4 inhibition. Nature. 2017;551(7679):247–50. https://doi.org:10.1038/nature24297.

- Cui W, Fowlis DJ, Bryson S, Duffie E, Ireland H, Balmain A, et al. TGFbeta1 inhibits the formation of benign skin tumors, but enhances progression to invasive spindle carcinomas in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996;86(4):531–42.

- Portella G, Cumming SA, Liddell J, Cui W, Ireland H, Akhurst RJ, et al. Transforming growth factor beta is essential for spindle cell conversion of mouse skin carcinoma in vivo: implications for tumor invasion. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9(5):393–404.

- Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(3):178–96. https://doi.org:10.1038/nrm3758.

- Nieto MA, Huang RY, Jackson RA, Thiery JP. Emt: 2016. Cell. 2016;166(1):21–45. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028.

- Oshimori N, Oristian D, Fuchs E. TGF-beta promotes heterogeneity and drug resistance in squamous cell carcinoma. Cell. 2015;160(5):963–76. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.043.

- Fischer KR, Durrans A, Lee S, Sheng J, Li F, Wong ST, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;527(7579):472–6. https://doi.org:10.1038/nature15748.

- Webb BM, Bryson BL, Williams-Medina E, Bobbitt JR, Seachrist DD, Anstine LJ, et al. TGF-β/activin signaling promotes CDK7 inhibitor resistance in triple-negative breast cancer cells through upregulation of multidrug transporters. J Biol Chem. 2021;297(4):101162. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101162.

- Ghosh S, Tanbir SE, Mitra T, Roy SS. Unveiling stem-like traits and chemoresistance mechanisms in ovarian cancer cells through the TGFβ1-PITX2A/B signaling axis. Biochem Cell Biol. 2024;102(5):394–409. https://doi.org:10.1139/bcb-2024-0010.

- da Costa KM, Freire-de-Lima L, da Fonseca LM, Previato JO, Mendonça-Previato L, Valente RDC. ABCB1 and ABCC1 Function during TGF-β-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition: Relationship between Multidrug Resistance and Tumor Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(7). https://doi.org:10.3390/ijms24076046.

- Wei L, Lin Q, Lu Y, Li G, Huang L, Fu Z, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts-mediated ATF4 expression promotes malignancy and gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer via the TGF-β1/SMAD2/3 pathway and ABCC1 transactivation. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(4):334. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41419-021-03574-2.

- Qian J, LeSavage BL, Hubka KM, Ma C, Natarajan S, Eggold JT, et al. Cancer-associated mesothelial cells promote ovarian cancer chemoresistance through paracrine osteopontin signaling. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(16). https://doi.org:10.1172/jci146186.

- Ebner J, Schmoellerl J, Piontek M, Manhart G, Troester S, Carter BZ, et al. ABCC1 and glutathione metabolism limit the efficacy of BCL-2 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Nature Communications. 2023;14(1):5709. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-023-41229-2.

- Dodagatta-Marri E, Meyer DS, Reeves MQ, Paniagua R, To MD, Binnewies M, et al. anti-PD-1 therapy elevates Treg/Th balance and increases tumor cell pSmad3 that are both targeted by anti-TGFbeta antibody to promote durable rejection and immunity in squamous cell carcinomas. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):62. https://doi.org:10.1186/s40425-018-0493-9.

- Tan L, Yin T, Xiang H, Wang L, Mudgal P, Chen J, et al. Aberrant cytoplasmic expression of UHRF1 restrains the MHC-I-mediated anti-tumor immune response. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):8569. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-024-52902-5.

- Taylor MA, Kandyba E, Halliwill K, Delrosario R, Khoroshkin M, Goodarzi H, et al. Stem-cell states converge in multistage cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma development. Science. 2024;384(6699):eadi7453. https://doi.org:10.1126/science.adi7453.

- Katsuno Y, Meyer DS, Zhang Z, Shokat KM, Akhurst RJ, Miyazono K, et al. Chronic TGF-β exposure drives stabilized EMT, tumor stemness, and cancer drug resistance with vulnerability to bitopic mTOR inhibition. Sci Signal. 2019;12(570). https://doi.org:10.1126/scisignal.aau8544.

- Zhou Q, Chen W, Fan Z, Chen Z, Liang J, Zeng G, et al. Targeting hyperactive TGFBR2 for treating MYOCD deficient lung cancer. Theranostics. 2021;11(13):6592–606. https://doi.org:10.7150/thno.59816.

- Liu K, Tian F, Chen X, Liu B, Tian S, Hou Y, et al. Stabilization of TGF-β Receptor 1 by a Receptor-Associated Adaptor Dictates Feedback Activation of the TGF-β Signaling Pathway to Maintain Liver Cancer Stemness and Drug Resistance. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(34):e2402327. https://doi.org:10.1002/advs.202402327.

- Wildey GM, Patil S, Howe PH. Smad3 potentiates transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta )-induced apoptosis and expression of the BH3-only protein Bim in WEHI 231 B lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(20):18069–77. https://doi.org:10.1074/jbc.M211958200.

- Ohgushi M, Kuroki S, Fukamachi H, O'Reilly LA, Kuida K, Strasser A, et al. Transforming growth factor beta-dependent sequential activation of Smad, Bim, and caspase-9 mediates physiological apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(22):10017–28. https://doi.org:10.1128/mcb.25.22.10017-10028.2005.

- Ramjaun AR, Tomlinson S, Eddaoudi A, Downward J. Upregulation of two BH3-only proteins, Bmf and Bim, during TGF beta-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2007;26(7):970–81. https://doi.org:10.1038/sj.onc.1209852.

- Gautron A, Bachelot L, Aubry M, Leclerc D, Quéméner AM, Corre S, et al. CRISPR screens identify tumor-promoting genes conferring melanoma cell plasticity and resistance. EMBO Mol Med. 2021;13(5):e13466. https://doi.org:10.15252/emmm.202013466.

- Loos B, Salas-Bastos A, Nordin A, Debbache J, Stierli S, Cheng PF, et al. TGFβ signaling sensitizes MEKi-resistant human melanoma to targeted therapy-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(12):925. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41419-024-07305-1.

- Castel P, Toska E, Engelman JA, Scaltriti M. The present and future of PI3K inhibitors for cancer therapy. Nat Cancer. 2021;2(6):587–97. https://doi.org:10.1038/s43018-021-00218-4.

- Derynck R, Turley SJ, Akhurst RJ. TGFbeta biology in cancer progression and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(1):9–34. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41571-020-0403-1.

- Ma MJ, Shi YH, Liu ZD, Zhu YQ, Zhao GY, Ye JY, et al. N6-methyladenosine modified TGFB2 triggers lipid metabolism reprogramming to confer pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma gemcitabine resistance. Oncogene. 2024;43(31):2405–20. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41388-024-03092-3.

- Xu WW, Huang ZH, Liao L, Zhang QH, Li JQ, Zheng CC, et al. Direct Targeting of CREB1 with Imperatorin Inhibits TGFβ2-ERK Signaling to Suppress Esophageal Cancer Metastasis. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2020;7(16):2000925. https://doi.org:10.1002/advs.202000925.

- Zhang B, Li Y, Wu Q, Xie L, Barwick B, Fu C, et al. Acetylation of KLF5 maintains EMT and tumorigenicity to cause chemoresistant bone metastasis in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1714. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-021-21976-w.

- Iliakis, G. The role of DNA double strand breaks in ionizing radiation-induced killing of eukaryotic cells. Bioessays. 1991;13(12):641–8. https://doi.org:10.1002/bies.950131204.

- Barcellos-Hoff, MH. Radiation-induced transforming growth factor beta and subsequent extracellular matrix reorganization in murine mammary gland. Cancer research. 1993;53(17):3880–6.

- Barcellos-Hoff MH, Dix TA. Redox-mediated activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta 1. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10(9):1077–83.

- Wilkinson B, Hill MA, Parsons JL. The Cellular Response to Complex DNA Damage Induced by Ionising Radiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5). https://doi.org:10.3390/ijms24054920.

- Ewan KB, Henshall-Powell RL, Ravani SA, Pajares MJ, Arteaga C, Warters R, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 mediates cellular response to DNA damage in situ. Cancer Res. 2002;62(20):5627–31.

- Kirshner J, Jobling MF, Pajares MJ, Ravani SA, Glick AB, Lavin MJ, et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta1 signaling attenuates ataxia telangiectasia mutated activity in response to genotoxic stress. Cancer Res. 2006;66(22):10861–9.

- Barcellos-Hoff MH, Akhurst RJ. Transforming growth factor-beta in breast cancer: too much, too late. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(1):202.

- Liu Q, Ma L, Jones T, Palomero L, Pujana MA, Martinez-Ruiz H, et al. Subjugation of TGFβ Signaling by Human Papilloma Virus in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Shifts DNA Repair from Homologous Recombination to Alternative End Joining. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(23):6001–14. https://doi.org:10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-1346.

- Kim MR, Lee J, An YS, Jin YB, Park IC, Chung E, et al. TGFβ1 protects cells from γ-IR by enhancing the activity of the NHEJ repair pathway. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13(2):319–29. https://doi.org:10.1158/1541-7786.Mcr-14-0098-t.

- Lee J, Kim MR, Kim HJ, An YS, Yi JY. TGF-β1 accelerates the DNA damage response in epithelial cells via Smad signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;476(4):420–5. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.05.136.

- Bouquet F, Pal A, Pilones KA, Demaria S, Hann B, Akhurst RJ, et al. TGFbeta1 inhibition increases the radiosensitivity of breast cancer cells in vitro and promotes tumor control by radiation in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(21):6754–65. https://doi.org:1078-0432.CCR-11-0544 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0544.

- Formenti SC, Lee P, Adams S, Goldberg JD, Li X, Xie MW, et al. Focal Irradiation and Systemic TGFbeta Blockade in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(11):2493–504. https://doi.org:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3322.

- Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2013;342(6165):1432–3. https://doi.org:10.1126/science.342.6165.1432.

- Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, Song C, Moreno BH, Hu-Lieskovan S, et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Features of Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma. Cell. 2016;165(1):35–44. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.065.

- Chakravarthy A, Khan L, Bensler NP, Bose P, De Carvalho DD. TGF-beta-associated extracellular matrix genes link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and immunotherapy failure. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4692. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-018-06654-8.

- Mariathasan S, Turley SJ, Nickles D, Castiglioni A, Yuen K, Wang Y, et al. TGFbeta attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature. 2018;554(7693):544–8. https://doi.org:10.1038/nature25501.

- Arteaga CL, Hurd SD, Winnier AR, Johnson MD, Fendly BM, Forbes JT. Anti-transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta antibodies inhibit breast cancer cell tumorigenicity and increase mouse spleen natural killer cell activity. Implications for a possible role of tumor cell/host TGF-beta interactions in human breast cancer progression. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1993;92(6):2569–76. https://doi.org:10.1172/JCI116871.

- Thomas DA, Massague J. TGF-beta directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(5):369–80. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.012.

- Dodagatta-Marri E, Ma HY, Liang B, Li J, Meyer DS, Chen SY, et al. Integrin αvβ8 on T cells suppresses anti-tumor immunity in multiple models and is a promising target for tumor immunotherapy. Cell Rep. 2021;36(1):109309. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109309.

- Ni Y, Soliman A, Joehlin-Price A, Rose PG, Vlad A, Edwards RP, et al. High TGF-β signature predicts immunotherapy resistance in gynecologic cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibition. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5(1):101. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41698-021-00242-8.

- Batlle E, Massague J. Transforming Growth Factor-beta Signaling in Immunity and Cancer. Immunity. 2019;50(4):924–40. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.024.

- Chen S-Y, Mamai O, Akhurst RJ. TGFβ: Signaling Blockade for Cancer Immunotherapy. Annual Review of Cancer Biology. 2022;6(1):123–46. https://doi.org:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-070620-103554.

- Gameiro SR, Strauss J, Gulley JL, Schlom J. Preclinical and clinical studies of bintrafusp alfa, a novel bifunctional anti-PD-L1/TGFβRII agent: Current status. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2022;247(13):1124–34. https://doi.org:10.1177/15353702221089910.

- Gulley JL, Schlom J, Barcellos-Hoff MH, Wang XJ, Seoane J, Audhuy F, et al. Dual inhibition of TGF-β and PD-L1: a novel approach to cancer treatment. Mol Oncol. 2022;16(11):2117–34. https://doi.org:10.1002/1878-0261.13146.

- Tauriello DVF, Sancho E, Batlle E. Overcoming TGFβ-mediated immune evasion in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(1):25–44. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41568-021-00413-6.

- Yoon H, Tang CM, Banerjee S, Delgado AL, Yebra M, Davis J, et al. TGF-β1-mediated transition of resident fibroblasts to cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes cancer metastasis in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Oncogenesis. 2021;10(2):13. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41389-021-00302-5.

- Al-Bzour NN, Al-Bzour AN, Ababneh OE, Al-Jezawi MM, Saeed A, Saeed A. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Gastrointestinal Cancers: Unveiling Their Dynamic Roles in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(22). https://doi.org:10.3390/ijms242216505.

- Li S, Liu M, Do MH, Chou C, Stamatiades EG, Nixon BG, et al. Cancer immunotherapy via targeted TGF-β signalling blockade in T(H) cells. Nature. 2020;587(7832):121–5. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41586-020-2850-3.

- Xu J, Li Z, Tong Q, Zhang S, Fang J, Wu A, et al. CD133(+)PD-L1(+) cancer cells confer resistance to adoptively transferred engineered macrophage-based therapy in melanoma. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):895. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-025-55876-0.

- Qin X, Yan M, Zhang J, Wang X, Shen Z, Lv Z, et al. TGFbeta3-mediated induction of Periostin facilitates head and neck cancer growth and is associated with metastasis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20587. https://doi.org:10.1038/srep20587.

- Zhao F, Evans K, Xiao C, DeVito N, Theivanthiran B, Holtzhausen A, et al. Stromal Fibroblasts Mediate Anti-PD-1 Resistance via MMP-9 and Dictate TGFbeta Inhibitor Sequencing in Melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6(12):1459–71. https://doi.org:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0086.

- Cremasco V, Astarita JL, Grauel AL, Keerthivasan S, MacIsaac K, Woodruff MC, et al. FAP Delineates Heterogeneous and Functionally Divergent Stromal Cells in Immune-Excluded Breast Tumors. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6(12):1472–85. https://doi.org:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0098.

- Saw PE, Chen J, Song E. Targeting CAFs to overcome anticancer therapeutic resistance. Trends in cancer. 2022;8(7):527–55. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.trecan.2022.03.001.

- Chandra Jena B, Sarkar S, Rout L, Mandal M. The transformation of cancer-associated fibroblasts: Current perspectives on the role of TGF-β in CAF mediated tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Cancer Lett. 2021;520:222–32. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.canlet.2021.08.002.

- Forsthuber A, Aschenbrenner B, Korosec A, Jacob T, Annusver K, Krajic N, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast subtypes modulate the tumor-immune microenvironment and are associated with skin cancer malignancy. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):9678. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-024-53908-9.

- Nakamura A, Mashima T, Lee J, Inaba S, Kawata N, Morino S, et al. Intratumor transforming growth factor-β signaling with extracellular matrix-related gene regulation marks chemotherapy-resistant gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024;721:150108. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150108.

- Dominguez CX, Muller S, Keerthivasan S, Koeppen H, Hung J, Gierke S, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals stromal evolution into LRRC15+ myofibroblasts as a determinant of patient response to cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2019. https://doi.org:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0644.

- Krishnamurty AT, Shyer JA, Thai M, Gandham V, Buechler MB, Yang YA, et al. LRRC15(+) myofibroblasts dictate the stromal setpoint to suppress tumour immunity. Nature. 2022;611(7934):148–54. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41586-022-05272-1.

- Kawasaki K, Noma K, Kato T, Ohara T, Tanabe S, Takeda Y, et al. PD-L1-expressing cancer-associated fibroblasts induce tumor immunosuppression and contribute to poor clinical outcome in esophageal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72(11):3787–802. https://doi.org:10.1007/s00262-023-03531-2.

- Louault K, Porras T, Lee MH, Muthugounder S, Kennedy RJ, Blavier L, et al. Fibroblasts and macrophages cooperate to create a pro-tumorigenic and immune resistant environment via activation of TGF-β/IL-6 pathway in neuroblastoma. Oncoimmunology. 2022;11(1):2146860. https://doi.org:10.1080/2162402x.2022.2146860.

- Yang K, Xie Y, Xue L, Li F, Luo C, Liang W, et al. M2 tumor-associated macrophage mediates the maintenance of stemness to promote cisplatin resistance by secreting TGF-β1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):26. https://doi.org:10.1186/s12967-022-03863-0.

- Mousset A, Lecorgne E, Bourget I, Lopez P, Jenovai K, Cherfils-Vicini J, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps formed during chemotherapy confer treatment resistance via TGF-β activation. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(4):757–75.e10. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.ccell.2023.03.008.

- Lainé A, Labiad O, Hernandez-Vargas H, This S, Sanlaville A, Léon S, et al. Regulatory T cells promote cancer immune-escape through integrin αvβ8-mediated TGF-β activation. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6228. https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-021-26352-2.

- Seed RI, Kobayashi K, Ito S, Takasaka N, Cormier A, Jespersen JM, et al. A tumor-specific mechanism of T(reg) enrichment mediated by the integrin αvβ8. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(57). https://doi.org:10.1126/sciimmunol.abf0558.

- Deng D, Begum H, Liu T, Zhang J, Zhang Q, Chu TY, et al. NFAT5 governs cellular plasticity-driven resistance to KRAS-targeted therapy in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2024;221(11). https://doi.org:10.1084/jem.20240766.

- Angel CZ, Beattie S, Hanif EAM, Ryan MP, Guerra Liberal FDC, Zhang SD, et al. A SRC-slug-TGFβ2 signaling axis drives poor outcomes in triple-negative breast cancers. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22(1):454. https://doi.org:10.1186/s12964-024-01793-6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).