1. Introduction

Livestock farming is a key contributor to the South African economy, with beef production being the largest sector within the industry (Scholtz & Theunissen, 2010). The beef farming sector consists of high-input commercial farming and a low-input smallholder production system. Smallholder farmers primarily rely on informal markets and predominantly raise indigenous beef cattle breeds such as Bonsmara, Nguni, Boran, and non-descript crossbreds (Mugwabana et al., 2018; Malusi et al., 2021). Smallholder and communal farmers own approximately 40% of the national beef cattle herd (DAFF, 2018), positioning them as potential key players in the beef value chain. However, low productivity remains a major challenge in this sector, largely due to poor management practices and limited adoption of efficient production technologies (Mugwabana et al., 2018; Hadgu et al., 2020). As a result, the offtake rate from smallholder farms is low, and their contribution to the mainstream beef market remains minimal (Malusi et al., 2021). Additionally, the sector faces increasing challenges due to global climate and environmental changes, further complicating efforts to enhance productivity and sustainability (Daly et al., 2020).

Indigenous African cattle breeds offer a viable alternative to imported breeds, particularly under the challenging climatic conditions of Sub-Saharan Africa (Mwai et al., 2015). These breeds have adapted to harsh environmental conditions, including periodic droughts, seasonal dry periods, nutritional deficiencies, parasite infestations, infectious diseases, and high ambient temperatures (Mwai et al., 2015). Their resilience makes them especially suitable for the smallholder farming sector, where they can thrive with minimal feed supplementation or veterinary intervention.

Poor reproductive performance is a major factor limiting beef cattle productivity in South Africa’s smallholder farming sector (Scholtz & Bester, 2010; Mmbengwa et al., 2015). Multiple embryo production through in vivo and in vitro techniques, followed by embryo transfer into recipient females, is a widely used assisted reproductive technology (ART) that has been shown to enhance reproductive efficiency and livestock productivity (References). This technology presents a promising opportunity to improve productivity in the smallholder sector. However, its success has varied under different environmental and management conditions.

The developmental competence and quality of produced embryos are critical determinants of the success of embryo production and transfer. Embryo quality directly influences pregnancy outcomes, with higher-quality embryos yielding better pregnancy rates (Rocha et al., 2016; Thompson, 2016). Several factors, including culture methods, culture conditions, and animal-related variables such as genetics and nutritional status, influence both embryo yield and quality thereby affecting reproduction (Lonergan et al., 2003; Lopes et al., 2020). Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the efficacy of embryo production techniques in specific production environments before promoting their widespread adoption.

Although embryo production and transfer hold potential for improving productivity in South Africa’s smallholder beef sector, no documented data exist on the application and efficiency of this technology in this setting, particularly using indigenous cattle breeds. This study was conducted to evaluate embryo production in Bonsmara, Nguni, and Boran cattle under smallholder beef production conditions using both in vivo and in vitro techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Adrich PTY LTD (South Africa) unless otherwise indicated.

2.2. Animal Management

All animals used in this study were 24-36 months of age, and were kept at a simulated quarantine facility at Embryo Plus Laboratories Pty, Ltd, where they were provided with water ad lib. Bulls were fed on eragrostis grass at ad lib. A total of 60 non-pregnant, healthy cycling cows (20 Nguni, 20 Bonsmara and 20 Boran) were selected as donors and randomly allocated to two embryo production methods, namely ovum pick-up (in vitro) and embryo flushing (in vivo). Each donor cow was fed 7-10 kg lucerne, eragrostis grass ad lib and 1.5kg of Afgri® embryo concentrate per day.

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. In Vivo Embryo Development

A total of 30 donor cows (10 Nguni; 10 Bonsmara; 10 Boran) were super stimulated for ovulation according to the method described by Pontes et al. (2009), with slight modifications. Briefly, a controlled internal drug release (CIDR®) (1.9g, Pfizer (Pty) Ltd, Sandton, Republic of South Africa) was inserted into the vagina of each cow on Day 0. An intramuscular injection of cloprostenol sodium (263μg, Estrumate®, Isando, and RSA) was administered to the cows after CIDR® removal on day 8, followed by intramuscular injection of estradiol benzoate (1g Pfizer (Pty) Ltd, Republic of South Africa) on Day 9. Signs of oestrus were observed using the heat mount detectors (Kamar®, RSA). Day 0 was then repeated by inserting a new CIDR three days after oestrus observation. On the 4th day following insertion of the second CIDR, two injections of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), Folltropin-V® (20mg, Armidale, Australia) were given at 12 h intervals initiated for 4 days on a decreasing dosage, plus two injections of prostaglandin 12 h apart on the last two days of Folltropin®. After detection of standing oestrous, each cow was inseminated twice (12 and 24 hours) with frozen/thawed semen from a bull of its respective breed. Thereafter, embryo recovery was performed 7 days post AI, whereby an epidural anaesthesia was performed with a standard non-surgical technique to flush the uterine horns using a three-way folley catheter. Flushed embryos were transferred into an embryo filter containing holding medium and evaluated using a stereo-microscope (Olympus SZ40, Olympus, Japan). Embryos were evaluated for embryo development (2–4 cells, 8-cell, Morula, Blastocyst).

2.3.2. In Vitro Embryo Development

Ovum pickup

Ovum pick up was performed on a total of 30 donor cows (10 Nguni’ 10 Bonsmara and 10 Boran) following the method described by Petyim et al. (2000), with minor modifications. Each cow was restrained in a crush pen and then given an epidural injection on the head of the tail. Thereafter, the rectum was emptied and the vulva was cleaned with a paper towel containing 70% alcohol, following which a transducer was advanced into the cervix. Targeted follicles were then transacted by the built-in puncture line on the ultrasound monitor by holding the ovaries through the rectum and positioning them over the transducer face. After stabilisation of the targeted follicles on the puncture line, the transducer needle was inserted into the guide and directed through the vaginal wall into the follicle antrum. Follicular fluid containing the oocytes was then aspirated and transferred into a 50ml tube, which was then taken to the laboratory for microscopic examination.

Ovary aspiration

Ovaries were collected from a local abattoir, and then transported to the laboratory in a pre-warmed (35°C) saline solution. They were then washed twice with buffered saline for removal of excess blood contaminants, within two hours of collection. This was followed by retrieval of oocytes from these ovaries, through the follicle aspiration method, using an 18-gauge hypodermic needle and 10ml syringe. Following aspiration, cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) with three or more layers of cumulus cells were selected using a stereo microscope (Olimpus®), and then washed three times in modified dulbecco phosphate buffered saline (mDPBS). Finally, the oocytes were washed again three times in 3ml petri dishes containing tissue culture medium (M199 + 10% foetus bovine serum) in preparation for in vitro maturation, fertilization and culture (IVMF).

IVMF and embryo production

In vitro maturation, fertilization and oocyte culture were carried out using procedures described by Huang et al. (2001), with slight modifications. Briefly, the cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) were matured for 24 hours in TCM-199 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 µg/ml leutenizing hormone, 1 µg/ml prostaglandin E2 and 1 µg/ml FSH, and then placed in an incubator with a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and a temperature of 38.5°C. Following maturation, oocytes were fertilized in 70 µl drops of Bracket and Olifants Fertilization medium, followed by co-incubation with frozen-thawed percoll gradient treated semen for 18 hrs at 38.5°C. After fertilization, presumptive zygotes were removed from the IVF medium and washed five times in 100 μl drops of synthetic oviductal fluid (SOF) supplemented with fatty acid free bovine serum albumin (BSA-FAF). They were then cultured in synthetic oviductal fluid (SOF) supplemented with bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated at 38.5°C in 5% CO2. The number of cleaved embryos from these presumptive zygotes was determined after 48 hours of culturing, and incubated further until Day 8.

2.3.3. Embryo Grading

Embryo grading was performed according to methods described in Manual of the International Embryo Transfer Society: a procedural guide and general information for the use of embryo transfer technology emphasizing sanitary procedures (Stringfellow and Givens, 2010). Embryos were graded at the different stages of development (2-4 cell, 8 cell, morula and blastocyst), and blastocyst quality was classified into 4 categories(1= excellent or good; 2= fair; 3= poor; 4= dead or degenerating embryos).

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

A two-way analysis of variance was carried out to test for the significance of the main effects (breed and embryo production method) as well as interaction effects. Pair-wise mean comparison was conducted using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) method (α = 0.05) if effects were significant.

3. Results

3.1. Breed Effects on Number of Embryos at Different Stages of Development

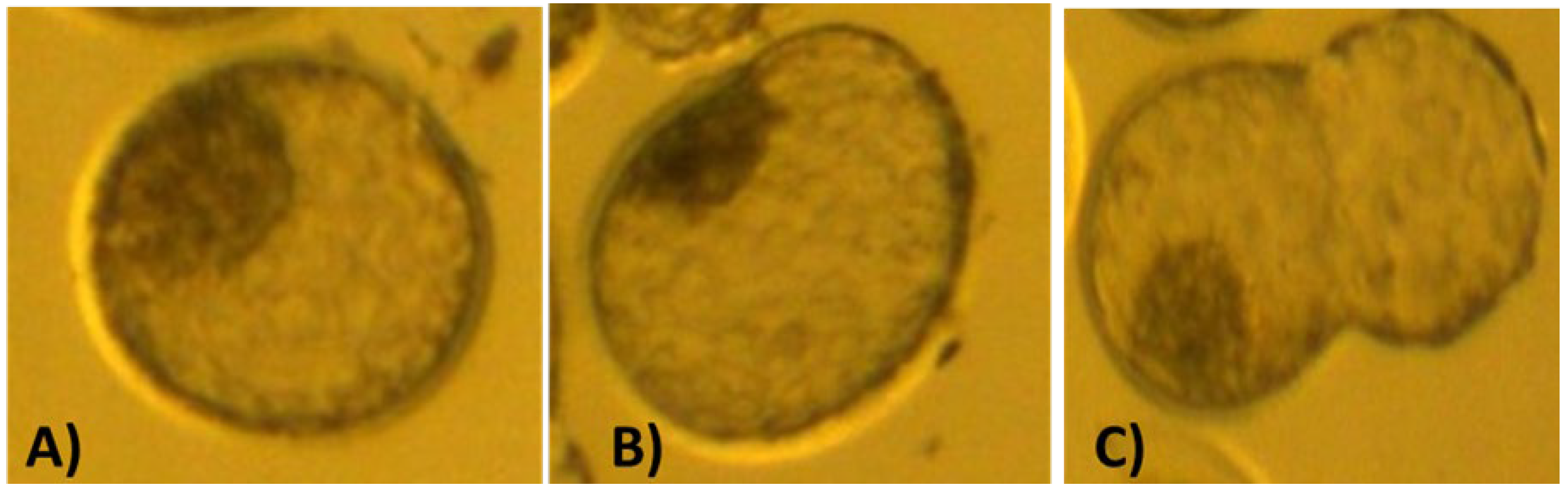

Figure 1 shows the appearance of embryos at the different developmental stages. Breed means for developmental competence of embryos produced by the in vivo and in vitro techniques are contained in

Table 1. There were no significant breed differences (P>0.05) in development to blastocyst, expanded blastocyst and hatched blastocyst stages for embryos produced in vivo . However, Bonsmara and Nguni breeds had significantly more (P<0.05) in vivo developed blastocysts on day 8 compared to the Boran. On the other hand, under in vitro conditions, there were no significant breed effects (P>0.05) for all developmental stages .

3.2. Breed Effects on Developmental Competency of In Vivo and In Vitro Produced Embryos

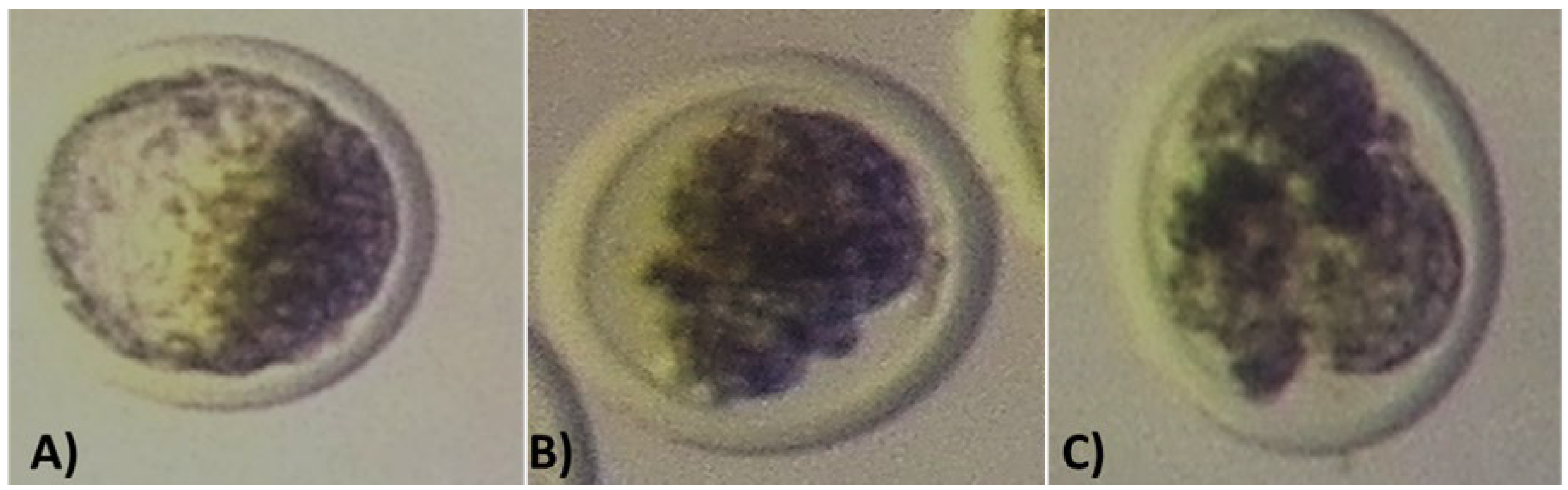

Blastocyst quality was determined by visual assessment and classification, which is a subjective method. Blastocyst quality was classified as Grade I, II and III and is represented in

Table 2, while the blastocyst quality (morphological grading) is presented in

Figure 2. No significant breed differences (P> 0.05) were detected in embryo quality under both in vivo and in vitro production techniques. cows in the number of blastocysts obtained following flushing (In vivo). All breeds showed, on average, a higher (P<0.05) number of Grade I blastocysts in vivo than under in vitro conditions. Furthermore, the number of Grade II and Grade III blastocysts were significantly lower (P>0.05) in all the breeds than those in grade I. Moreover, the number of Grade III embryos produced by in vivo method was significantly higher (P<0.05) in Bonsmara cattle compared to Boranand Nguni cattle. There were no significant differences in the number of Grade I, Grade II and Grade III blastocyst produced by the in vitro method. On average, all breeds produced higher (P<0.05) number of Grade I embryos than Grade II or Grade III.

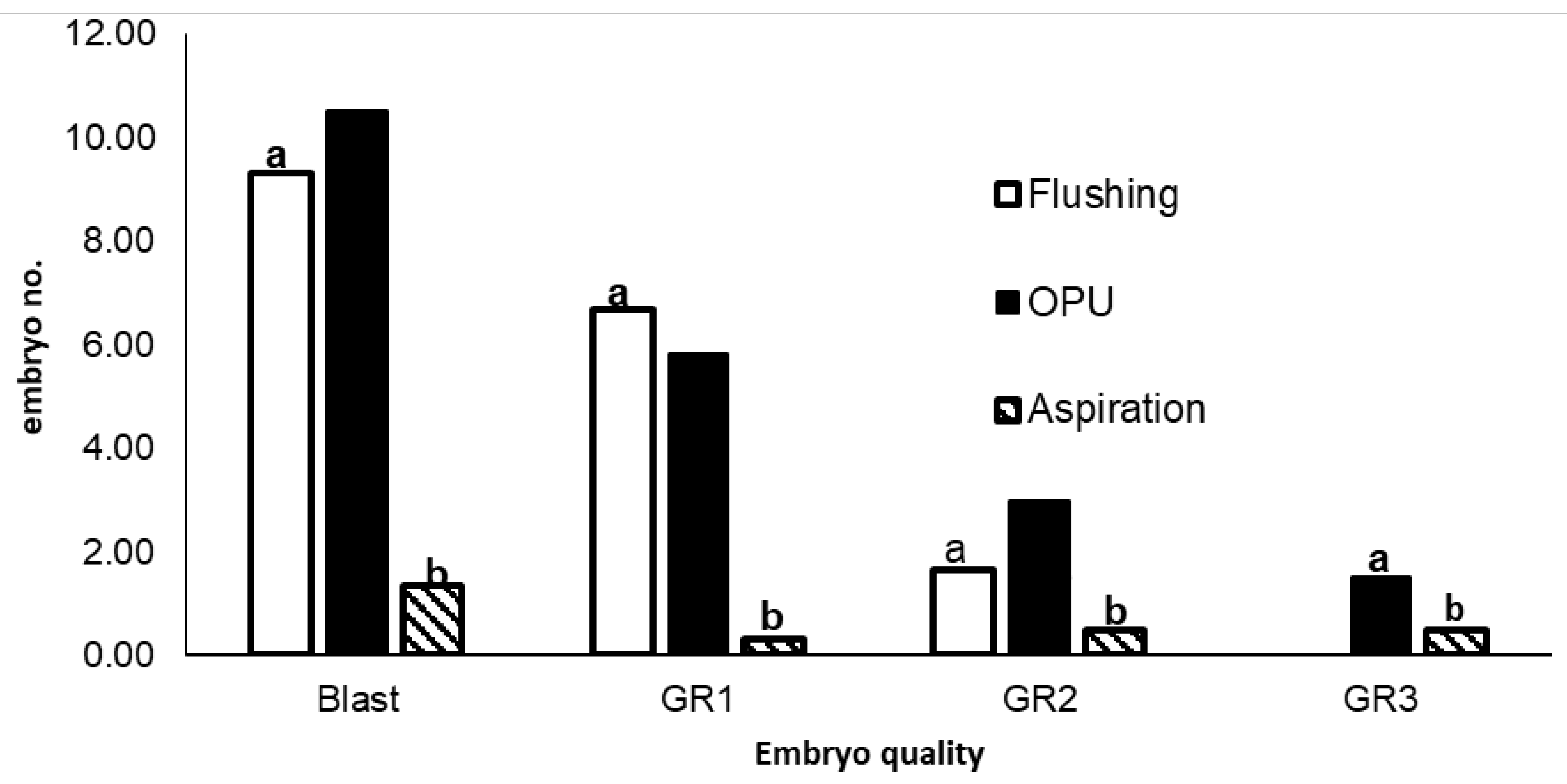

3.3. Effects of Retrieval Method on Embryo Quantity and Quality

Embryo retrieval method significantly (P<0.05) influenced the number of embryos developing into blastocysts, and the quality of embryos produced. Means for the quantity and quality of embryos obtained with each of the 3 embryo retrieval techniques (flushing, OPU and aspiration) are compared in Figure 4. Flushing and Ovum pickup (OPU) methods produced a significantly (P<0.05) higher number blastocysts than aspiration. There were significantly (P<0.05) more morphologically superior (Grade I and Grade II) embryos produced by flushing and OPU compared to aspiration. The number of Grade I and Grade II embryos produced by flushing and OPU were, however, not significantly different (P>0.05).. In addition, flushing produced fewer (P>0.05) embryos compared to OPU and aspiration methods.

Figure 3.

Means for number of blastocysts and embryos in Grade I (GR1), Grade II (GR2) and Grade III (GR3) produced by flushing, ovum pick-up and aspiration oocyte and embryo retrieval methods . Different letters (a and b) indicate significant differences (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Means for number of blastocysts and embryos in Grade I (GR1), Grade II (GR2) and Grade III (GR3) produced by flushing, ovum pick-up and aspiration oocyte and embryo retrieval methods . Different letters (a and b) indicate significant differences (P<0.05).

4. Discussion

Embryo quality is a critical factor that determines conception after embryo transfer. In our study, development of day 7 blastocyst to the hatching stage did not show any statistical difference (P>0.05) in both the in vivo and in vitro methods. Contrary to these findings, Mahdavinezhad et al. (2019) reported a lower hatching rate for blastocysts produced in vivo compared to their in vitro counterparts. Normal hatching was shown to occur in in vivo developed grade I (Excellent) embryos, while those developed in vitro showed a hardened zona, which negatively affects the hatching ability of the blastocyst (Velásquez et al., 2013). For the in vivo technique, Nguni and Bonsmara breeds had a higher (P<0.05) number of day 8 blastocysts than the Boran, whereas no differences (p>0.05) were observed under the in vitro method. Viana et al. (2010) similarly found breed differences in the amount of embryo transcripts when using the in vivo production system, but no differences with the in vitro technique. Differences in reproductive performance among breeds are evident from the literature (References). . Factors such as semen quality, heat stress and nutritional management may, however, also affect the ability of the embryo to develop and complete the gestation (Abraham et al., 2012).

No statistical (p>0.05) difference in grade I -grade II embryos in all breeds studied. The Bonsmara breed had more (p<0.05) in vivo produced grade III embryos than the Nguni. High rates of grade III embryo production translate to low chances of accomplishing pregnancy following transfer. Such embryos are regarded as abnormal and are usually discarded. Silva et al (2013) also found breed differences in embryo quality, with the Nellore (Bos indicus) breed producing better embryos than the Angus (Bos taurus). The higher rate of Grade III embryo production by the Bonsmara may be due to its partial Hereford (Bos taurus) blood composition, which makes it relatively less adapted to heat stress than the Nguni and Boran. Satrapa et al. (2011) also found embryos of crossbreds (indicus x taurus) to be more sensitive to heat than those of pure Bos indicus breeds.

Significant (P<0.05) differences in the number of embryos developing into blastocysts, and the quality of embryos produced, were observed among the three different oocyte retrieval methods used in the current study. Blastocyst rate for OPU and flushing derived oocytes was significantly (p<0.05) higher than for those aspirated from abattoir ovaries, which concurs with previous findings by Karadjole et al (2010). Oocytes retrieved from OPU and aspiration were handled and cultured in the same way. Exposure to high temperatures during collection and transportation of ovaries, may have contributed to the poorer oocyte development, and subsequent lower blastocyst yield, for the OPU method. Other previous studies have, however, reported higher blastocyst rates from abattoir derived oocytes than aspirated ones (Merton et al., 2008). Factors such as the size of the needle and level of vacuum pressure used may influence the quality of oocytes produced by OPU, due to loss of cumulus cells that hinders development of oocytes to the blastocyst stage (References?). We also observed a larger (P<0.05) number of grade I and grade II blastocysts for OPU and embryo flushing compared to aspiration, which is consistent with results from previous research (Mapletoft et al 2015; Bó et al., 2019; de Oliveira Bezerra et al., 2019). Our study has however produced unsatisfactory results as there are still other factors such as heat, nutrition and hormonal treatments that affects the quality of embryos despite of the method used.

5. Conclusions

Results of the current study suggests superiority of the in vivo method over the in vitro technique, in developing embryos from Bonsmara, Boran and Nguni cattle breeds, in a smallholder farming environment. The Bonsmara breed produced more poor quality embryos than the Nguni and Boran, which is probably a reflection of the fact that the latter breeds are slightly more adapted to this environment. Quantities of good quality embryos were however, equally good for the Bonsmara as for the Nguni and Boran. Based on the current findings, in vivo embryo production, combined with the ovum pickup embryo retrieval method, present a fair opportunity to improve the productivity of smallholder beef cattle, using adapted indigenous breeds. However, despite the current findings, the use and application of this technology in the smallholder environment has got its own limitations. The in vivo and in vitro embryo production technology is relatively expensive for smallholder farmers with limited-no financial resources. Therefore, there is a need for government support for off-take for its sustenance. Further research is required to improve embryo developmental rates, as well as to develop adaptable methods or protocol for indigenous breeds.

Author contribution

All authors designed the research work and prepared the manuscript daft; MHM conceptualized and designed the study, collected and analysed data and wrote the manuscript. CMP collected the data, read, improved, and approved the manuscript. JWN supervised, read improve and approved the final manuscript. CBB supervised, acquired researchfunding, read, improved, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received funding and support for this research through the Agricultural Research Council.

Ethics approval

The experimental work was submitted and approved by the Agricultural Research Council-Animal Production ethics committee on the 17 November 2016, Ref no. APIEC16/029 and University Limpopo ethics committee meeting dated 9 July 2018, Ref no. AREC/03/2018:PG.

Consent to participate and consent for publication

Consent for use of experimental animals was given by Embryo plus Pty, Ltd. All the authors have equally participated in this study and agreed to publish this work in this journal.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Code availability

Not applicable

References

- Abraham, N.M.; Lamlertthon, S.; Fowler, V.G.; Jefferson, K.K. Chelating agents exert distinct effects on biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus depending on strain background: role for Clumping Factor B. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2012, 78, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholtz, M.M.; Theunissen, A. The use of indigenous cattle in terminal crossbreeding to improve beef cattle production in Sub-Saharan Africa. Animal Genetic Resources Information 2010, 46, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadjole, M.; Getz, I.; Samardžija, M.; Maćešić, N.; Matković, M.; Makek, Z.; Karadjole, T.; Baćić, G.; Poletto, M. The developmental competence of bovine immature oocytes and quality of embryos derived from slaughterhouse ovaries or live donors by ovum pick up. Vet. Arch 2010, 80, 445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Greive, T.; Callesen, H. Embryo technology: implications for fertility in cattle. Revue scientifique technique (International Office of Epizootics. 2005, 24, 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; De Haan, C. Livestock’s long shadow - Environmental issues and options; FAO Agriculture Technical paper; Rome, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Otten, D.; Van Den Weghe, H.F. The Sustainability of Intensive Livestock Areas (ILAS): Network system and conflict potential from the perspective of animal farmers. International Journal on Food System Dynamics 2011, 2, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugwabana, T.J.; Muchenje, V.; Nengovhela, N.B.; Nephawe, K.A.; Nedambale, T.L. Challenges with the implementation and adoption of assisted reproductive technologies under communal farming system. Journal of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Health 2018, 10, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadgu, A.; Fesseha, H. Reproductive Biotechnology Options for Improving Livestock Production: A Review. Advances in Food Technology and Nutritional Sciences 2020, 6, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwai, O.; Hanotte, O.; Knon, Y.J.; Cho, S. African Indigenous Cattle: Unique Genetic Resources in Rapid Changing World. Asian Australas Journal of Animal Science 2015, 7, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, J.C.; Passalia, F.; Matos, F.D.; Maserati, M.P.; Alves, M.F.; Almeida, T.G.; Cardoso, B.L.; Basso, A.C.; Nogueira, M.F. Methods for assessing the quality of mammalian embryos: How far we are from the gold standard? JBRA Assisted Reproduction 2016, 20, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, J.H.; Nonato-Junior, I.; Sanches bv Ereno-Junior, J.C.; Uvo, S.; Barreiros, T.R.; Oliveira, J.A.; Hasler, J.F.; Seneda, M.M. Comparison of embryo yield and pregnancy rate between in vivo and in vitro methods in the same Nelore (Bos indicus) donor cows. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringfellow, D.A.; Givens, M.D. Manual of the International Embryo Transfer Society (IETS), 4th ed.; IETS: Champaign, IL, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavinezhad, F.; Kazemi, P.; Fathalizadeh, P.; Sarmadi, F.; Sotoodeh, L.; Hashemi, E.; Hajarian, H. and Dashtized, M., In vitro versus In vivo: Development-Apoptosis- and Implantation Related Gene Expression in Mouse Blastocyst. Iran Journal of Biotechnology 2019, 17, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.M.S.; Santos, F.P.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Silva, E.M.S.; Silva, G.S.S.; Novais, J.S. Phenolic compounds, melissopalynological, physicochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of jandaira (Melipona subnitida) honey. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2013, 29, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrapa, R.A.; Nabhan, T.; Silva, C.F.; Simões, R.A.L.; Razza, E.M.; Puelker, R.Z. Influence of sire breed (Bos indicus versus Bos taurus) and interval from slaughter to oocyte aspiration on heat stress tolerance in vitro-produced bovine embryos. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, J.S.; Ask, B.; Onkundi, D.C.; Mullaart, E.; Colenbrander, B.; Nielen, M. Genetic parameters for oocyte number and embryo production within a bovine ovum pick-up-in vitro production embryo-production program. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.G.; Brown, H.M.; Sutton-McDowall, M.L. Measuring embryo metabolism to predict embryo quality. Reproduction Fertility and Development 2016, 28, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.; Smith, H.; McGrice, H.A.; Kind, K.L.; van Wettere, W.H.E.J. Review Towards Improving the Outcomes of Assisted Reproductive Technologies of Cattle andSheep, with Particular Focus on Recipient Management. Animals 2020, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.G.; Hasler, J.F. A 100-Year Review: Reproductive technologies in dairy science. Journal of Dairy Science 2017, 100, 10314–10331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, O.S.; Alcázar-Triviño, E.; Soriano-Úbeda, C.; Hamdi, M.; Cánovas, S.; Rizos, D.; Coy, P. Reproductive Outcomes and Endocrine Profile in Artificially Inseminated versus Embryo Transferred Cows. Animals 2020, 10, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, M.J.; Zeng, F.Y.; Ren, Z.R.; Zeng, Y.T. Selection of in vitro produced, transgenic embryos by nested-PCR for efficient production of transgenic goats. Theriogenology 2001, 56, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petyim, S.; Bage, R.; Forsberg, M.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H.; Larsson, B. The effect of repeated follicular puncture on ovarian function in dairy heifers. Journal of Veterinary Medicine. Series A: Physiology, Pathology, Clinical Medicine 2000, 47, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, J.H.; Palhao, M.P.; Siqueira, L.G.; Fonseca, J.F.; Camargo, L.S. Ovarian follicular dynamics, follicle deviation, and oocyte yield in Gyr breed (Bos indicus) cows undergoing repeated ovum pick-up. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapletoft, R.J.; Guerra, A.G.; Dias, F.C.F.; Singh, J.; Adams, G.P. In vitro and in vivo embryo production in cattle superstimulated with FSH for 7 days. Animal Reproduction 2015, 12, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).