1. Introduction

Coal is a dominant energy source, contributing 27.1% of the global energy mix and ranking as the second-most-important energy source (Zocche et al., 2023). In South Africa, coal is a key strategic mineral, accounting for around 80% of the electricity produced in 2022 (Pierce and Le Roux, 2023), while also directly employing 90,977 people (Minerals Council South Africa, 2023) and supporting an estimated 170,000 indirect jobs (Chamber of Mines of South Africa, 2018). Despite the benefits, coal mining comes with significant environmental and health costs. Although South Africa has robust environmental legislation, including the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA), the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA), the National Water Act (NWA), and the National Environmental Management: Waste Act (NEM:WA), which aim to regulate and alleviate environmental effects of mining, the industry continues to pose significant environmental degradation (Hassan., 2023).

The two primary factors contributing to the widespread issue of deserted mines and inadequate rehabilitation in South Africa are the business rescue and winding-up processes, and non-compliance with regulatory requirements by some mining companies (Almano, 2022; Mpanza et al., 2021; Mpanza et al., 2020; Humby, 2015; Centre for Environmental Rights, 2018). Furthermore, the government's efforts to address the legacy of abandoned mines have been slow or lacking (Mabaso, 2023; Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, 2019). Consequently, substantial waste with potentially toxic elements and compounds, including heavy metals, generated by the mining process are released into the environment, presenting serious threats to aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, water resources, and public health due to its persistence and ability to bioaccumulate (Akbar et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2024; Ai et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2020; Pei et al., 2017; Byrne et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2017; Sahoo et al., 2016).

Coal mining activities alter soil physicochemical properties, structure, horizons, microorganisms, and nutrient cycles (Huang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). Elevated metal content in soil, exceeding local background levels and receptor tolerance, poses severe risks to public health, food safety, agricultural productivity, and ecosystem health (Zerizghi et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2020). In Mpumalanga Province, coal mining has caused substantial environmental degradation, with acid mine drainage (AMD) and contaminated runoff posing threats to water quality and ecosystem health (Hasii & Gasii, 2024; Simpson et al., 2019). Witbank (eMalahleni) is a notable example, with approximately 22 coal mines operating in the area (Bench Marks Foundation, 2014). A century of coal mining in Witbank coalfields has resulted in significant environmental, social, and health impacts (Centre for Environmental Rights (CER, 2016). Studies have shown that coal mining can contaminate rivers, posing risks to aquatic life and human well-being (Magagula et al., 2024; Atangana and Oberholster, 2021; Du Plessis, 2017). Thus, regular assessments of chemical, physical, and biological properties of rivers and their tributaries are crucial to understanding and mitigating these impacts (Yadav and Jamal, 2018; Mayer et al., 2010).

Various water quality assessment tools and indices have been developed to evaluate the state of water in abandoned mines, rivers, and reservoirs. Notable indices include the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment Water Quality Index, as well as organic pollution, trace metal pollution, comprehensive pollution, and general water quality indices. These tools collectively provide a robust framework for assessing and managing water quality, as supported by recent studies (Uddin et al., 2021; Son et al., 2020; Kachroud et al., 2019). Researchers have used these indices to investigate coal mining impacts on water resources (Magagula et al, 2024), water contamination in rivers (Son et al, 2020; Karim et al, 2018), dams (Oberholster et al, 2021), and lakes (Mishra et al, 2016). The concentration of heavy metals in soils impacted by mining and the bioaccumulation of these metals in plant samples were investigated by several researchers (Akbar et al. 2024; Du et al., (2024); Shi et al. (2023); Shi et al. (2023); Espinoza et al. (2022).

Existing research on abandoned mines in South Africa has largely overlooked the application of water quality assessment indices and the development of practical remediation plans. This study fills this gap by presenting a remediation plan that encompasses AMD treatment, soil remediation, and sustainable post-mining land use options, promoting a circular economy approach. This work seeks to answers the following research questions: (1) What is the extent of soil and water pollution at the abandoned coal mine site? (2) How does the water quality at the site compare to national and international standards? (3) What remediation strategies can be employed, to mitigate the impact of coal mining? It is hypothesized that the abandoned coal mine site exhibits significant levels of soil and water pollution, exceeding national and international standards, and that the water quality poses to human health and the environment.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

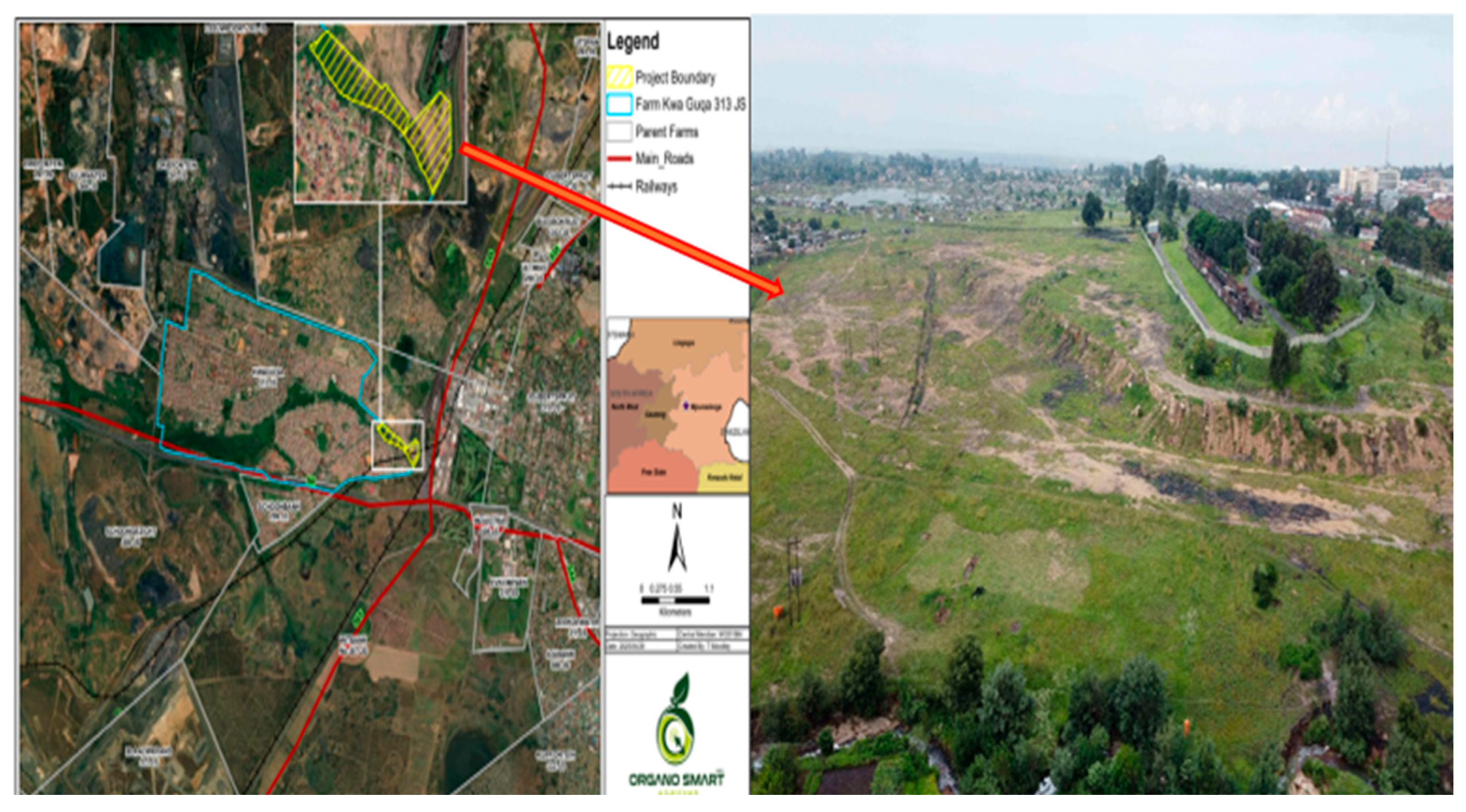

The study site, spanning approximately 6.76 hectares, is located on portion 60 of the farm KwaGuqa 313 JS within the EMalahleni Local Municipality, Nkangala district municipality, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Specifically, it lies in the B11K quaternary catchment area, about 900 m west of the R544 tar road to Verena and 600 m north of the N4 highway. The site falls within the Eastern Highveld Grassland vegetation unit (Gm 12) of the Mesic Highveld Grassland Bioregion in the Grassland Biome. The site was previously utilized by the adjacent community for farming before mining activities commenced.

The study area falls within the summer rainfall region of Mpumalanga province which experiences a Highveld climate with pronounced seasonal variations. Temperatures range from -3°C to 20°C in winter and 12°C to 29°C in summer. The area receives most of its rainfall (about 91% of the annual total) during the wet season from October to April, with an average annual precipitation of 674 mm (South African Weather Services, 2023). Frost is a regular occurrence, with 13 to 42 days of frost per year, particularly at higher elevations (Mucina and Rutherford 2006). The study area’s geology and soils comprise predominantly red and yellow sandy soils formed on shales and sandstones of the Madzaringwe formation, which is part of the Karro Super Group Geology and soils (Mucina and Rutherford 2006). The study area's topography is generally flat with gentle slopes and shallow sandy terrain, featuring subdued relief (Cairncross and McCarthy 2008). Coal mining in the area primarily employs opencast mining methods due to the shallow depth of coal deposits (Wilson and Anhaeusser, 1998).

Figure 1 shows the extent of the site under study.

2.2. Sampling and Analysis Techniques

The primary objectives and activities within the catchment informed the selection of this study site. Sampling points were strategically chosen to target potential pollution sources and areas of concern.

2.2.1. Soil Sampling

The soil samples were strategically collected from the southern end of the site and near the stream to evaluate the chemical status and potential contamination caused by the abandoned mine. Five samples were extracted from 0-30 cm depth with a stainless steel spade, which was cleaned between each use to prevent cross-contamination. Each sample consisted of triplicate subsamples collected within a 2-meter radius, and each location’s GPS coordinates were recorded. The samples were packed in labelled polyethylene bags and transported to Environmental Pollution Laboratory (EPL), a South African National Accreditation System (SANAS) accredited laboratory within 24 hours.

2.2.2. Surface Water Sampling

Samples of water were collected from four points: two within the abandoned coal mine and two from the adjacent stream. Grab sampling was employed, using a plastic bailer to collect water, which was then transferred to 1-liter plastic bottles. To prevent contamination, water from each site was used to rinse the bailer prior to sampling. Each bottle was labelled with sample name, date, and time. Samples were collected during the day and transported to the EPL in Pretoria in a cooler box. EPL conducted the analysis.

The sampling points effectively represented the objectives of the study.

Figure 2 shows the soil sampling locations and surface water sampling points within the surface water drainage system.

2.2.3. Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted according to the South African Bureau of Standards (SABS) methods. Water quality assessments were benchmarked against SANS 241: 2015 for drinking water and SA DWAF guidelines for livestock watering. The CCME Water Quality Index (CCME-WQI) was used to evaluate water pollution levels based on measured parameters, providing a simplified and trend-analyzable representation of water quality data, as outlined in Equation 1 (Magagula et al., 2024).

where F1 denotes the number of variables which fail to meet their objectives, as defined in Equation 2..

F

2 represents the number of individuals not meeting the objectives also known as the frequency.

F3, also referred to as amplitude, quantifies the extent to which objectives were not met and is calculated as follows:

The degree of noncompliance is determined by calculating the normalized sum of excursions (

nse) as shown in Equation 6

If the CCME–WQI is from 0 to 25, the WQI is classified as unsuitable, while the ranges 26 to 50, 51 to 70, 71 to 90 and 91 to 100 are classified as very poor, poor, good and excellent, respectively (Ramakrishnaiah et al, 2009).

All soil analysis and water quality analyses for surface water samples are represented as the mean.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physico-Chemical Data: Soils

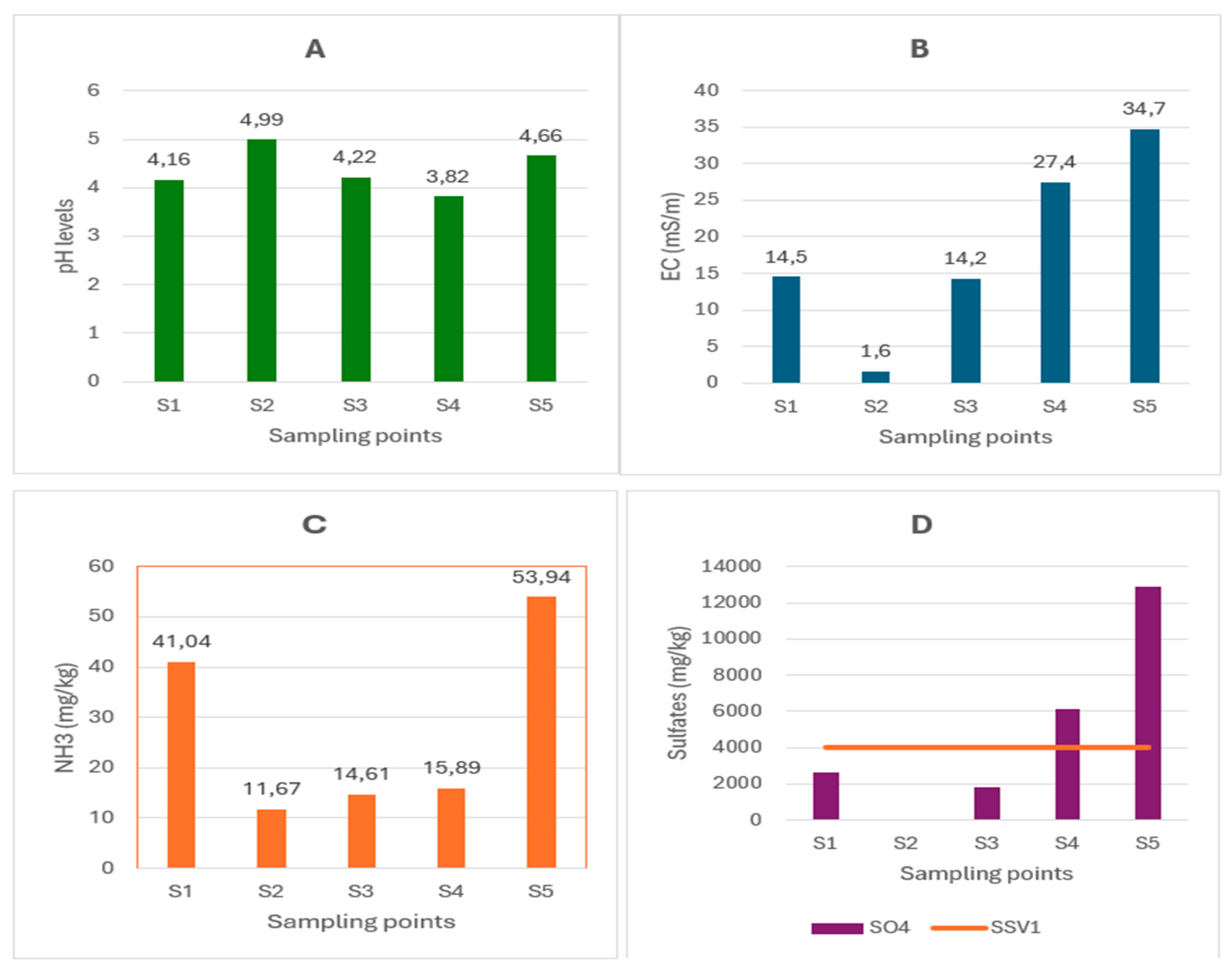

The physico-chemical data of the measured parameters for the soil are presented in

Table 1 below. All soil monitoring sites exhibited pH levels within the 3.5–5.0 range, characteristic of acidic conditions.

pH levels indicate acidity or alkalinity, calculated as the negative logarithm of H+ ion concentration. Acidic pH can result from acid mine water formed by pyrite (FeS

2) oxidation in coal (Asif et al., 2025). Sulfates, naturally occurring in various rock and soil types, are also generated abundantly through mining activities. Notably, sulfate concentrations at S4 and S5 exceeded the 2000 mg/L limit for soil screening value 1 (SSV1), (the soil quality standards that safeguard human health and ecosystems from toxic risks, considering multiple exposure routes and potential water contamination), coinciding with the highest electrical conductivity (EC) values at these sites. Ammonia (NH

3) concentrations followed the order: S5 > S1 > S4 > S3 > S2.

Figure 3 below is a graphical representation of the pH, EC, NH

3 and SO

4 of the soil samples at the study site.

Sample 2 (S2) showed better soil quality parameters (lowest levels of (NH3), sulfate (SO4), and EC, as well as a less acidic pH compared to the other samples), possibly due to its location or the absence of coal remnants and water drainage (which is acidic) in the sampling area. Sample 5 (S5), located in a low-lying area near the stream, exhibited the most deteriorated soil quality parameters (highest NH3, SO4 and EC), likely due to the accumulation of contaminants transported by surface runoff, seepage, leaching, and gravity-driven transport from the abandoned mine. S5’s poses a high risk of contamination. S4 and S3 were obtained from stockpiled material, while S1 was sampled in close proximity to the coal remnants. The high levels of sulfate and acidity in the soils may be attributed to AMD or oxidation of sulfide minerals in the soil (Asif et al., 2025). The elevated NH3 levels could be linked to decomposition of organic matter (in S5) or contamination from nearby sources (S1 and S5) (World Health Organization (WHO), 2017), including the community. These findings are consistent with previous studies, highlighting the environmental risks associated with abandoned coal mines and their impact on soil quality (Favas et al., 2016).

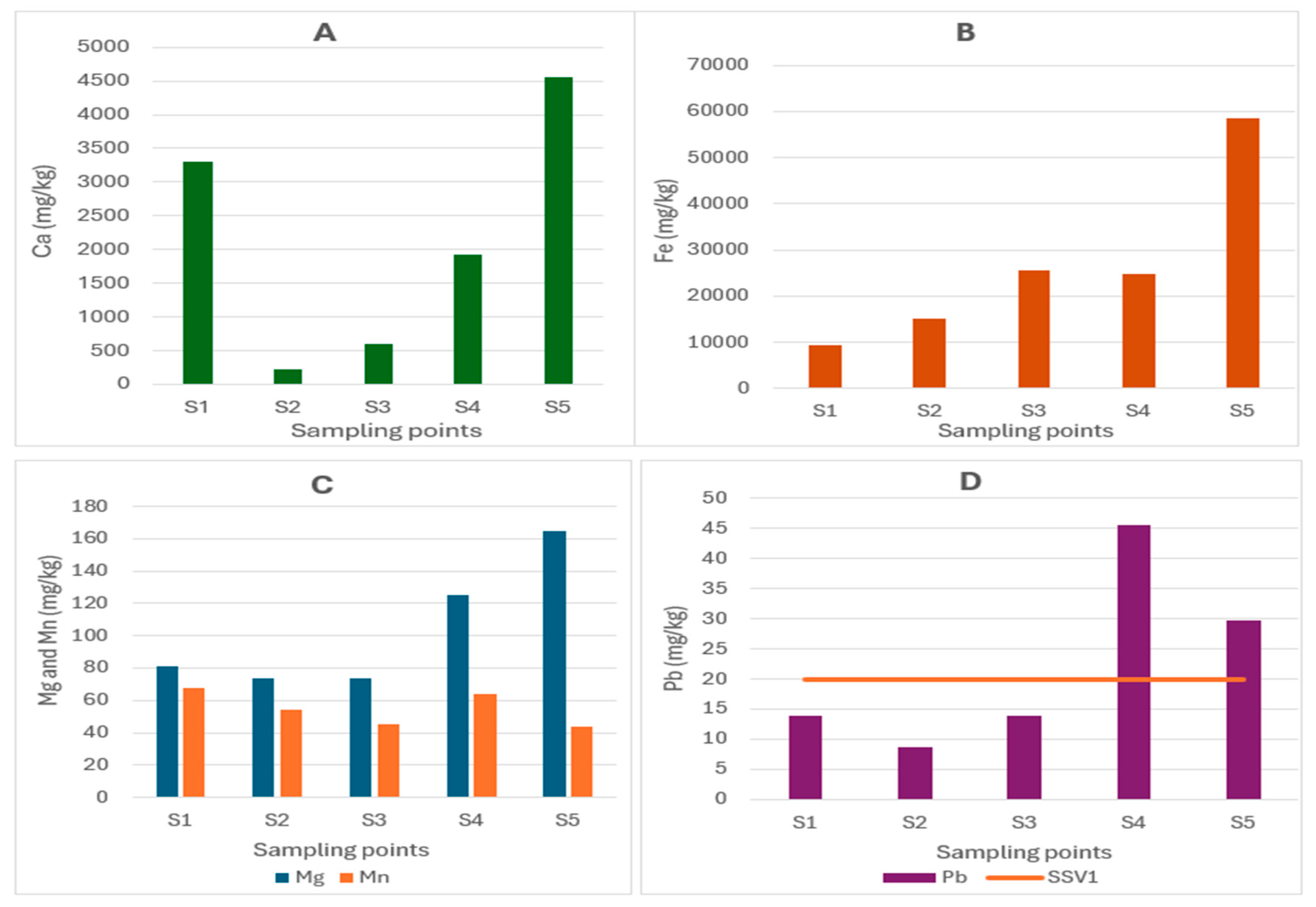

Figure 4 shows the concentrations of different metals measured in the soil samples. The element concentrations (mg/kg) ranged from 9373-58497 for Fe, 43.70-67.82 for Mn, and 8.61-45.48 for Pb. Concentrations of Ca and Mg ranged from 225.70 to 4562.00 mg/kg and 73.43 to 164.40, respectively.

Based on the South African guidelines, the concentrations of Pb in S4 and S5 were above the SSV1 standard. The average levels in this study area are higher than those reported in the Mpumalanga province rangeland in 2006 (Steyn and Herselman, 2006). The high concentrations of Ca, Fe, Pb and Mg especially in S4 and S5 may be related to the acidic pH and high conductivity values observed at this site and their location within the study site in relation to the potential contaminants sources. Acidic conditions can lead to increased mobility and solubility of the metals, allowing them to be more easily transported and accumulated in the soil (Grantcharova et al., 2021). The high sulfate levels in S4 and S5 may also contribute to the elevated Ca, Fe, Pb and Mg concentrations, as sulfate can form complexes with these metals, increasing their mobility and bioavailability (Ying et al., 2022). The fact that Sample 2 had the lowest concentrations of Ca, Mg, Pb and Fe may be related to its relatively less acidic pH, lower conductivity and its location relative to contaminants sources. This suggests that Sample 2 may be less impacted by the mining activities, resulting in lower levels of metal contamination (Favas et al., 2016).

The Pb content in the coal samples varies significantly, with levels in S1, S2, and S3 (13.83, 8.16, and 13.83 mg/kg, respectively) comparable to those in U.S. and Chinese coals (11 mg/kg and 15.1 mg/kg; Orem & Finkelman, 2003; Dai et al., 2012), but higher than global averages for hard and low-rank coals (9.0 mg/kg and 6.6 mg/kg respectively (Ketris & Yudovich, 2009). However, S4 and S5 exhibit significantly higher Pb contents (45.48 and 29.76 mg/kg, respectively), exceeding the worldwide mean. This suggests potential Pb enrichment or contamination in these samples, possibly related to the mining activities.

Heavy metals (such as Pb) contamination in soil and materials left on the surface poses serious environmental and health risks owing to their bioaccumulation, toxicity, and potential release into the environment (Mahar et al., 2016; Rouhani et al., 2023). Soil pollution can harm organisms which dwell in the soil and their consumers, disrupting the ecosystem (Lu et al., 2021). Soil microorganisms and vegetation are particularly vulnerable to pollution, and the initial risk (Ri) they face can have cascading impacts through the food web (Chen et al., 2011). The conditions at the study site (low pH, high sulfate levels, and elevated Pb and Fe concentrations), particularly at S5, may favour the growth of certain alien invasive species that adapts to stressful conditions (

Figure 5):

The presence of the invasive and alien plant species is a symptom of a highly modified ecosystem. The invasive species on the study site include Acacia mearnsii (black wattle), Eupatorium macrocephalum (Pom pom), Ipomoea purpurea (common morning glory, Solanum mauritianum (bug weed), Mirabilis jalapa (Four o’clock), Eucalyptus diversicolor (Karri), Pennisetum clandestinum (Kikuyu grass). Alien and invasive species pose a serious threat to native ecosystems, competing with and replacing indigenous plant species, leading to veld degradation, reduction in biodiversity, and alteration of ecosystem processes (van Wilgen et al., 2001; Richardson & van Wilgen, 2004). These invasive species can invade various habitats, including woodlands, waste areas, arable land, roadsides, riverbanks, and coastal dunes, outcompeting native vegetation and altering community composition and ecosystem function (Henderson, 2001). Species along watercourses, in particular, can reduce stream flow, while species like kikuyu can crowd out desirable species, further exacerbating ecosystem degradation (Le Maitre et al., 2000). The alteration of ecosystems can have far-reaching impacts on livelihoods, food security, and cultural practices, emphasizing the need for effective management and control of invasive species.

The catchment’s water supply is substantially polluted by the river inflow, which in turn leads to severe sanitary and ecological problems (Sigua and Tweedale 2003; Singh et al. 2005). The surface runoff can mobilise the heavy metals from spoil or refuse dumps, potentially contaminating subsurface soil and nearby water resources through leaching (De and Mitra, 2004).

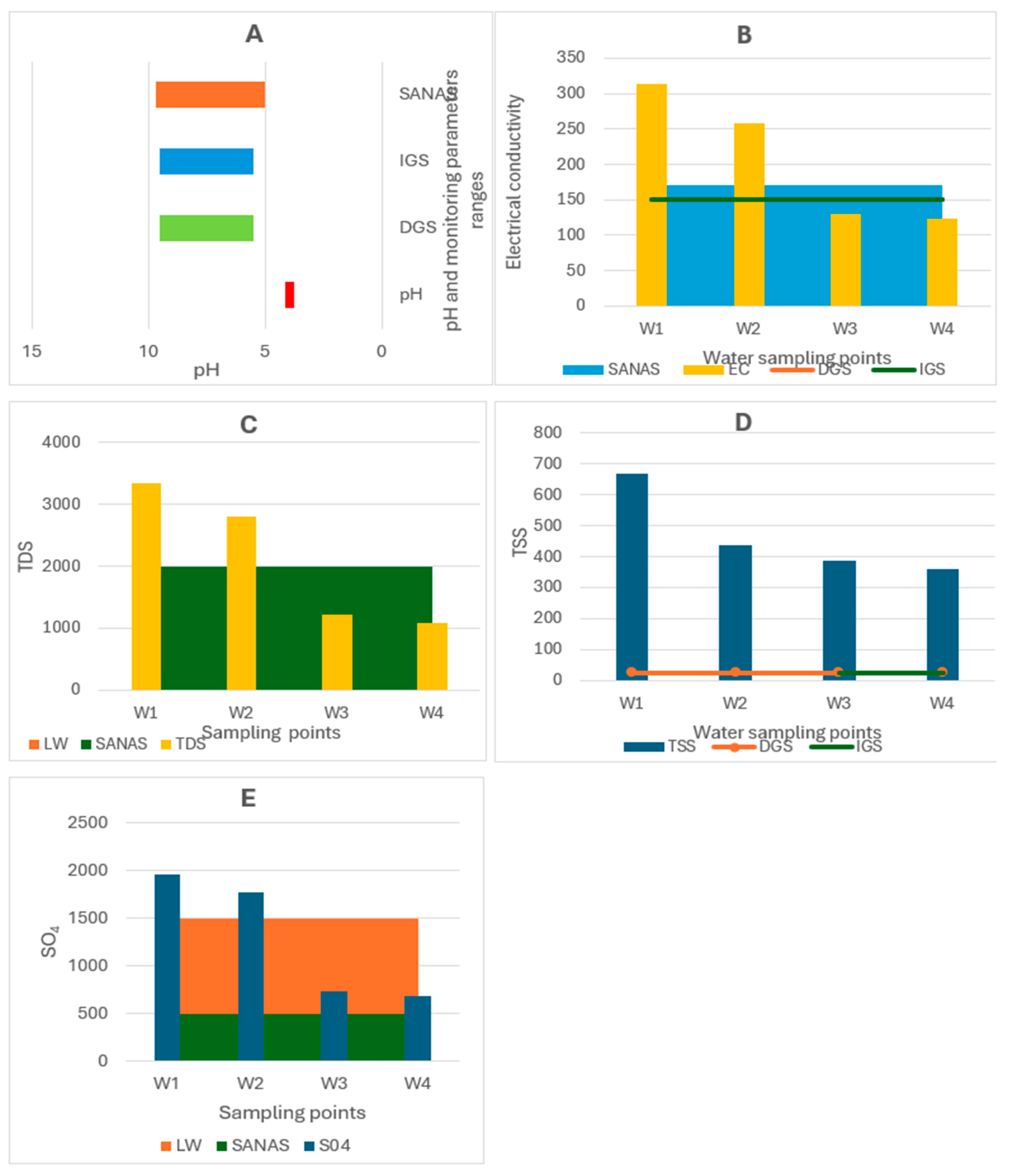

3.2. Physico-Chemical Data: Water

Generally, surface water monitoring sites show high levels of contamination. The assessed water quality data revealed that the surface water from all monitoring points exhibited some degree of contamination, likely linked to coal mining and associated activities. Largely, the site has acidic water, high EC, TDS, TSS and SO

4 exceeding several monitoring standards as shown in

Table 2 below.

The pH, TSS, SO

4, Fe and Mn at all the sampling points exceeded atleast one of the standards. EC for W1 and W2 (the sampling points within the mine) were above the discharge and irrigation general standards. Additionally, the TDS for W1 and W2 exceeded the livestock watering and the domestic use SANAS guidelines. W3 and W4 surface water monitoring sites located within the tributary showed an improved water quality compared to W1 and W2 (

Figure 6).

The elevated concentrations of SO

4, together with the low pH, are characteristic of AMD, a serious environmental issue related to coal mining (Reddick, 2016). The presence of oxygen, water, and acidophilic bacteria accelerates the AMD process, generating acidic runoff and facilitating heavy metal leaching. The resulting sulfuric acid can mobilize heavy metals like Mn, arsenic (As), nickel (Ni), chromium (Cr), and Pb from surrounding rocks, soil, and water, further contaminating the environment and posing significant ecological and health risks (Lechner et al., 2016).

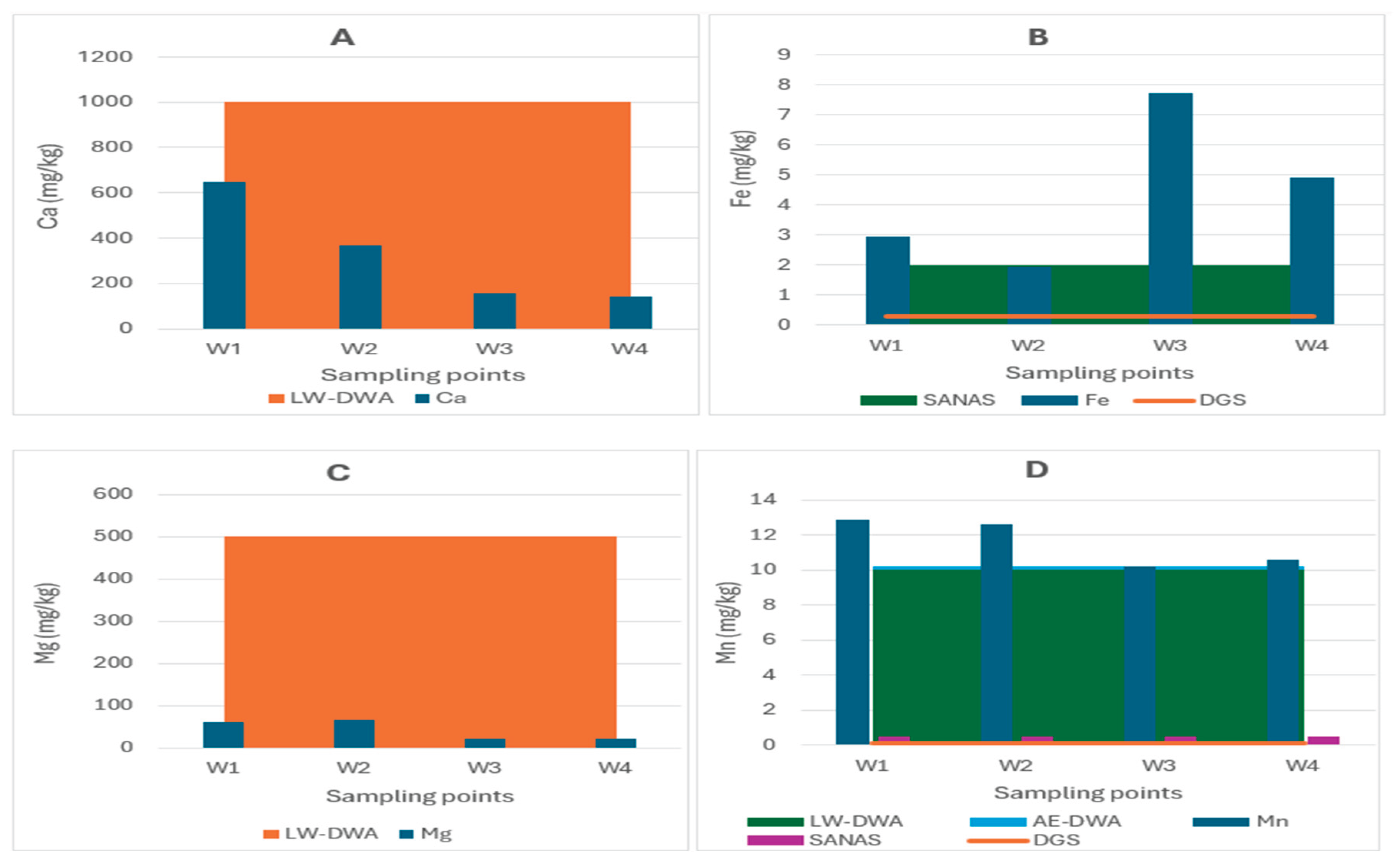

Figure 7 presents different metals concentrations in the water samples and the different standards. Although other heavy metals concentrations were beyond the scope of the present study, the analysis of samples at mine sites like the Greenside coal mine in Mpumalanga, as well as background concentrations (Zenizghi et al., 2022) has shown high concentrations of these heavy metals.

Mn concentrations in water samples exceeded the water standards although its concentractions decreased in the order W1 > W2 > W3 >W4. As distance increases from coal mines, the levels of potentially toxic elements and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in plants and soil tend to decline. This trend aligns with various studies including Shi et al. (2013); Song et al. (2023); Yakovleva et al. (2016), which demonstrated the impact of coal mining activities on environmental pollution and potential health risks in surrounding areas. This could be the reason for improved water quality on sample W3 and W4 further from the site. Moreover, the effect of dilution of the mine water with the stream water may have led to the observed results.

Fe concentrations also exceeded the standards, however the concentrations were in the order W3 > W4 > W1 >W2. The stream water has high Fe concentrations compared to the water on the abandoned mine. This may be attributed to rapid pH neutralization as the AMD from the mine enters the stream, resulting in metal precipitation and deposition in the bottom sediments within the localized discharge area (Mosley et al., 2018; Gavan et al., 2021), especially for W3 where the effluent from the mine enters the tributary (Fe concentration is7.73 mg/l) which decreased to 4.93 downstream at W4 due to dilution (Mosley et al., 2018).

The findings from the CCME-WQI analysis further proved that the water quality for both livestock and domestic use is poor, with scores of 43.33 and 15.56, respectively. These figures translates to poor water qualityu for livestock watering and unsuitable for domestic use. This shows that water quality at the sight is threatened. These findings are consistent with other research in Mpumalanga Province. Laisani and Jegede (2019) also reported increased chemical pollution and siltation of water, streams and other water bodies due to increased sediment loads at various mining impacted locations. According to the Department of Water and Sanitation (Mpumalanga), rivers such as the Olifants River and Wilge River are heavily polluted due to mining and other human activities. Reports also indicate that abandoned mines are negatively affecting agricultural activities in areas like Kendal and Ogies due to land degradation, resulting in large sinkholes and burning coal. Mining activities can leave lasting environmental legacies, including soil pollution that impacts nutrient availability and microbial activity (Wen et al., 2015). Even after mining operations cease, these sites can remain significant environmental liabilities, requiring ongoing monitoring and remediation efforts to mitigate their effects on ecosystems and human health.

4. Opportunities for Remediation and Value-Added Benefits

Our findings reveal that abandoned mine waste is undergoing oxidation, generating AMD and resulting in elevated metal concentrations in both soil and water, which in turn promotes the spread of alien species. Given these concerns, a rehabilitation plan prioritizing sustainable development goals, and circular economy principles, while aligning with potential end-use scenarios, is crucial. Adopting remediation or treatment approaches to neutralize acidity, curb metal leaching, and eliminate invasive alien species is an important step toward effective waste management and repurposing the land for potential end use.

4.1. AMD Treatment

AMD emanates from the mined area. While various AMD treatment technologies, single or combined, can be used to achieve effective treatment (Mosai et al., 2024), passive treatment approaches for AMD are advantageous due to their reduced resource requirements and infrequent reagent additions (Skousen et al., 2017). Furthermore, these systems operate without power and require minimal maintenance, rendering them a cost-effective solution, particularly suitable for abandoned mine sites. Passive treatment systems utilize natural geochemical and biological processes to improve mine water quality by passing it through a controlled environment (Bai et al., 2023). Abiotic passive treatments, such as open limestone channels and limestone leach beds, generate alkalinity to neutralize AMD and raise pH, promoting metal oxidation and precipitation (Rezaie and Anderson, 2020). However, the use of lime and limestone as prevalent reagents for AMD remediation is often hindered by the formation of sludge, which can lead to armouring on the reagent surface, thereby limiting dissolution and causing system clogging (Kefeni et al., 2017). In contrast, biotic passive treatments, including bioreactors and wetlands, harness natural biological processes under anaerobic or aerobic conditions to neutralize AMD and precipitate contaminants like metals over time (Rezaie and Anderson, 2020). Ramla and Sheridan (2015) demonstrated the use of indigenous South African grass, Hyparrhenia hirta, as an organic substrate for sulphate-reducing bacteria, which led to the reduction of sulphate to sulphides. Constructed wetlands, which leverage neutralizing agents, plants, and organic substrates, can be a viable alternative for the study site as noted by Naghaum et al. (2025). Constructed wetlands effectively neutralize acidity, remove metals, and enhance microbial sulfate reduction, resulting in a treated effluent that can be reused for various purposes (Naghaum et al., 2025). The constructed wetland approach, as an attractive approach, warrants further investigation to tailor it to the site's specific conditions.

4.2. Remediation, Reclamation, and Restoration of the Soils

The study site can be divided into two distinct areas: (i) the waste dump area and (ii) the mined area, both of which are generating AMD. The site can be remediated in situ using various physico-chemical techniques, including the isolation of soil and containment, vitrification, solidification and stabilization, soil flushing, and electrokinetic remediation (Dada et al., 2015). Conventional methods are often prohibitively expensive, damaging to soil structure, and harmful to microbial communities, rendering them unsustainable for large-scale use. In contrast, phytoremediation, which harnesses the power of plants and their associated microorganisms to remediate environmental pollutants, presents a more cost-effective and attractive alternative (Wan et al., 2016). By leveraging soil amendments and agronomic practices, phytoremediation can remove, contain, or neutralize toxins (Kafle et al., 2022). According to Xie et al. (2020), three key strategies for reclaiming abandoned mine lands include stabilizing surfaces to prevent erosion, containing toxic pollutants, and restoring the natural landscape.

Prior to implementing these strategies at the study site, coal remnants should be removed for potential use in domestic energy production. The residual coal poses a significant health and economic risk to nearby communities due to its susceptibility to spontaneous combustion (Bai, 2020; Zhou et al., 2017). Additionally, the site is currently impacted by invasive alien species, which can be harvested before flowering, composted, and repurposed as natural fertilizers to enrich the soil and improve its structure. However, if metal accumulation in these plants is high, the compost may be more suitable for use on the waste dump, where the metals can be stabilized in-situ, rather than on the mined land, which requires eventual cleanup and repurposing for community farm, the preferred post-mining land use for the study site.

Initially, both the waste dump area and the mined area must be planted with fast-growing hyperaccumulator plant species such as Berkheya coddii that can extract valuable metals. The benefits of recovering minerals and metals from mine wastes are multifaceted, including environmental mitigation, revenue generation, and supply of feedstock materials for industrial processes. By valorizing mine wastes, circular economy can be promoted thereby achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Kinnunen and Kaksonen, 2019). For instance, the Mn concentration in the water at the study site is high, presenting an opportunity to extract Mn, a metal crucial for steel alloying and electric vehicle battery production (Summerfield, 2020). Notably, pyrite from the study site can be repurposed as a valuable feedstock for sulfuric acid production and iron (Fe) recovery (Santander and Valderrama, 2019). However, metal recovery from mine wastes faces constraints such as low metal concentrations, limited accessibility, presence of hazardous elements like As, insufficient recovery technologies, and high reprocessing costs (Naidu et al., 2019).

After phytomining, the waste dump material can be utilized for road surfacing, bricks, or alternatively, high biomass producing plants can be planted to stabilize the dump. Grass species, such as vetiver grass, with deep roots and tolerance to elevated heavy metal concentrations, adaptability to different climatic conditions and a wide pH range, can be planted on the waste dump to stabilize metals in their rhizomes (Mlalazi et al., 2024). Vetiver grass is high in carbon sequestration and can also be harvested for bioenergy production (Mlalazi et al., 2024). Numerous benefits, such as improved water quality, reduced soil erosion, and enhanced ecosystem health and functionality, may be achieved. These outcomes will preserve natural resources, ultimately leading to a more sustainable environment for future generations (Ukhurebor et al., 2024; Holcombe and Keenan, 2020). Rehabilitating the mined area could increase arable land for farming, significantly contributing to global food security and helping to meet the needs of a growing population (Kopittke et al., 2019; de Paulo Farias and dos Santos Gomes, 2020). Moreover, the community can produce surplus food for selling, thereby increasing economic activity in the area and generating new income streams (Sengupta et al., 2018). This is important, as the closure of the mine likely resulted in job losses and reduced economic activity, affecting the livelihoods of local residents who may have been previously employed in the mining industry, either on a permanent or temporary basis.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed the ecological risks created by abandoned coal mine in eMalahleni, Mpumalanga province, South Africa, by analyzing various parameters in water and soil samples. The analysis included pH, EC, SO4, Ca, Fe, Mg, Mn, and Pb concentrations, as well as NH3 in soil samples and TSS and TDS in water samples. It was shown that the mean concentrations of heavy metals in both water and soil samples exceeded local background levels. Notably, Pb levels in soil samples surpassed the South African guidelines for water source protection which is dangerous to human and animal health. Furthermore, several water quality parameters, excluding Ca, Mg, and Pb, exceeded acceptable limits, highlighting potential environmental concerns. In conclusion, the abandoned coal mine site can be remediated and reclaimed through a combination of passive treatment approaches, such as constructed wetlands, and phytoremediation techniques. By leveraging natural geochemical and biological processes, acidity can be neutralized, remove metals, microbial sulfate reduction can be promoted, ultimately producing a treated effluent suitable for various end-uses. Phytomining can also extract valuable metals, generate revenue and promoting a circular economy. The remediation process can yield numerous environmental benefits such as improved water quality, reduced soil erosion, improved water quality, and ecosystem health. Further, rehabilitating the mined area can increase arable land for farming, contributing to global food security and generating new income streams for the local community. By adopting a sustainable and cost-effective approach, more sustainable environment for future generations can be created and the local economy can be supported.

Data Availability Statement

The laboratory results are available on request.

Acknowledgments

Analysis of the samples was funded by Procon Environmental Technologies.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- Almano, Z. (2022). The rehabilitation and closure of mines: A failure in the protection of human rights. University of Cape Town. The Rehabilitation and Closure of Mines: A Failure in the Protection of Human Rights | Mineral Law in Africa. Downloaded 21 July 2025.

- AI, Y., CHEN, H., CHEN, M., HUANG, Y., HAN, Z., LIU, G., ... & LI, J. (2023). Characteristics and treatment technologies for acid mine drainage from abandoned coal mines in major coal-producing countries. Journal of China Coal Society, 48(12), 4521-4535.

- Akbar, W. A., Rahim, H. U., Irfan, M., Sehrish, A. K., & Mudassir, M. (2024). Assessment of heavy metal distribution and bioaccumulation in soil and plants near coal mining areas: implications for environmental pollution and health risks. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 196(1), 97. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. R., Ye, B., & Ye, C. (2025). Acid sulfate soils: formation, identification, environmental impacts, and sustainable remediation practices. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 197(4), 484.

- Atangana, E., & Oberholster, P. J. (2021). Using heavy metal pollution indices to assess water quality of surface and groundwater on catchment levels in South Africa. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 182, 104254. [CrossRef]

- Bai, G., Zeng, X., Li, X., Zhou, X., Cheng, Y., & Linghu, J. (2020). Influence of carbon dioxide on the adsorption of methane by coal using low-field nuclear magnetic resonance. Energy & Fuels, 34(5), 6113-6123.

- Bai, S. J., Li, J., Yuan, J. Q., Bi, Y. X., Ding, Z., Dai, H. X., & Wen, S. M. (2023). An innovative option for the activation of chalcopyrite flotation depressed in a high alkali solution with the addition of acid mine drainage. Journal of Central South University, 30(3), 811-822. [CrossRef]

- Bench Marks Foundation. 2014. South African coal mining, Corporate Grievance Mechanisms, Community Engagement Concerns, and Mining Impacts. Policy Gap 9. Johannesburg: South Africa.

- Bodansky, D. (2016). The Paris climate change agreement: a new hope?. American Journal of International Law, 110(2), 288-319. http://doi:10.5305/amerjintelaw.110.2.0288.

- Byrne, P., Runkel, R. L., & Walton-Day, K. (2017). Synoptic sampling and principal components analysis to identify sources of water and metals to an acid mine drainage stream. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24(20), 17220-17240. [CrossRef]

- Cairncross, B., & McCarthy, T. S. (2008). A geological investigation of Klippan in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. South African Journal of Geology, 111(4), 421-428.

- Centre for Environmental Rights (CER, 2016). Zero hour. Poor Governance of Mining and the Violation of Environmental Rights in Mpumalanga. Cape Town: South Africa.

- Centre for Environmental Rights (CER, 2018). The truth about mining rehabilitation in South Africa.

- Chamber of Mines of South AFRica. 2018. National Coal Strategy for South Africa 2018. Minerals Council South Africa, Johannesburg. https://www.mineralscouncil.org.za/component/jdownloads/send/25-downloads/535-coal-strategy-2018.

- Chen, H., Teng, Y., Lu, S., Wang, Y., & Wang, J. (2011). Contamination features and health risk of soil heavy metals in China. Science of the Total Environment, 409(22), 4565-4574. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Miller, S. A., & Ellis, B. R. (2017). Comparative human toxicity impact of electricity produced from shale gas and coal. Environmental Science & Technology, 51(21), 13018-13027. http://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b03546.

- Dada, E. O., Njoku, K. I., Osuntoki, A. A., & Akinola, M. O. (2015). A review of current techniques of physico-chemical and biological remediation of heavy metals polluted soil. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management, 8(5), 606-615.

- Dai, S., Ren, D., Chou, C. L., Finkelman, R. B., Seredin, V. V., & Zhou, Y. (2012). Geochemistry of trace elements in Chinese coals: A review of abundances, genetic types, impacts on human health, and industrial utilization. International Journal of Coal Geology, 94, 3-21. [CrossRef]

- de Paulo Farias, D., & dos Santos Gomes, M. G. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak: What should be done to avoid food shortages?. Trends in food science & Technology, 102, 291.

- De, S., & Mitra, A. K. (2004). Mobilization of heavy metals from mine spoils in a part of Raniganj coalfield, India: Causes and effects. Environmental Geosciences, 11(2), 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (2019) Progress in Dealing with Derelict and Ownerless Mines. Department of Mineral Resources, Pretoria.http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/141112derelict.ppt.

- Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa. National Water Act, 1998 (Act No. 36 of 1998): Classes and 25 Resource Quality Objectives of Water Resources for the Olifants Catchment; Government Gazette No. 466; Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201604/3 9943gon466.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Dold, B. (2014). Evolution of acid mine drainage formation in sulphidic mine tailings. Minerals, 4(3), 621-641. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Tian, Z., Zhao, Y., Wang, X., Ma, Z., & Yu, C. (2024). Exploring the accumulation capacity of dominant plants based on soil heavy metals forms and assessing heavy metals contamination characteristics near gold tailings ponds. Journal of Environmental Management, 351, 119838. [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A. (2017). Freshwater challenges of South Africa and its Upper Vaal river (pp. 129-151). Berlin, Germany:: Springer.

- Dzhangi, T. R., & Atangana, E. (2024). Evaluation of the impact of coal mining on surface water in the Boesmanspruit, Mpumalanga, South Africa. Environmental Earth Sciences, 83(6), 159. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, S. E., Quiroz, I. A., Magni, C. R., Yáñez, M. A., & Martínez, E. E. (2022). Long-term effects of copper mine tailings on surrounding soils and sclerophyllous vegetation in Central Chile. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 233(8), 288.

- Favas, P. J. C., Pratas, J., & Prasad, M. N. V. (2016). Review of the environmental impacts of abandoned mines in South Africa. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(1), 33-45.

- Galván, L., Olías, M., Cerón, J. C., & de Villaran, R. F. (2021). Inputs and fate of contaminants in a reservoir with circumneutral water affected by acid mine drainage. Science of the Total Environment, 762, 143614. [CrossRef]

- Grantcharova, M. M., & Fernández-Caliani, J. C. (2021). Soil acidification, mineral neoformation and heavy metal contamination driven by weathering of sulphide wastes in a Ramsar wetland. Applied Sciences, 12(1), 249.

- Hasii, O., & Gasii, G. (2024, May). Coal mining and water resources: impacts, challenges, and strategies for sustainable environmental management. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 1348, No. 1, p. 012017). IOP Publishing. http://doi.org.10.1088/1755-1315/1348/1/012017.

- Hassan, A. S. (2023). Coal mining and environmental sustainability in South Africa: do institutions matter?. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(8), 20431-20449. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, L. (2001). Alien weeds and invasive plants. A complete guide to declared weeds and invaders in South Africa.

- Holcombe, S., & Keenan, J. (2020). Mining as a temporary land use scoping project: transitions and repurposing. The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia.

- Huang, Y., Kuang, X., Cao, Y., & Bai, Z. (2018). The soil chemical properties of reclaimed land in an arid grassland dump in an opencast mining area in China. Rsc Advances, 8(72), 41499-41508. http://doi.org.10.1039/C8RA08002J Humby, T. L. (2015). ‘One environmental system’: aligning the laws on the environmental management of mining in South Africa. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 33(2), 110-130.

- Jiang, C., Zhao, Q., Zheng, L., Chen, X., Li, C., & Ren, M. (2021). Distribution, source and health risk assessment based on the Monte Carlo method of heavy metals in shallow groundwater in an area affected by mining activities, China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 224, 112679. [CrossRef]

- Kachroud, M., Trolard, F., Kefi, M., Jebari, S., & Bourrié, G. (2019). Water quality indices: Challenges and application limits in the literature. Water, 11(2), 361. [CrossRef]

- Kafle, A., Timilsina, A., Gautam, A., Adhikari, K., Bhattarai, A., & Aryal, N. (2022). Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, plant selection and enhancement by natural and synthetic agents. Environmental Advances, 8, 100203.

- Karim, M., Das, S. K., Paul, S. C., Islam, M. F., & Hossain, M. S. (2018). Water quality assessment of Karrnaphuli River, Bangladesh using multivariate analysis and pollution indices. Asian J. Environ. Ecol, 7, 1-11. http://doi.org.10.9734/AJEE/2018/43015.

- Kefeni, K. K., Msagati, T. A., & Mamba, B. B. (2017). Acid mine drainage: Prevention, treatment options, and resource recovery: A review. Journal of cleaner production, 151, 475-493.Ketris, M. Á., & Yudovich, Y. E. (2009). Estimations of Clarkes for Carbonaceous biolithes: World averages for trace element contents in black shales and coals. International journal of coal geology, 78(2), 135-148. [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, P. H. M., & Kaksonen, A. H. (2019). Towards circular economy in mining: Opportunities and bottlenecks for tailings valorization. Journal of Cleaner Production, 228, 153-160.

- Kopittke, P. M., Menzies, N. W., Wang, P., McKenna, B. A., & Lombi, E. (2019). Soil and the intensification of agriculture for global food security. Environment international, 132, 105078.

- Kumar, S., Banerjee, S., Ghosh, S., Majumder, S., Mandal, J., Roy, P. K., & Bhattacharyya, P. (2024). Appraisal of pollution and health risks associated with coal mine contaminated soil using multimodal statistical and Fuzzy-TOPSIS approaches. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering, 18(5), 60. [CrossRef]

- Laisani, J., & Jegede, A. O. (2019). Impacts of coal mining in Witbank, Mpumalanga province of South Africa: An eco-legal perspective. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, 8, 1586-1597.

- Le Maitre, D. C., Versfeld, D. B., & Chapman, R. A. (2000). Impact of invading alien plants on surface water resources in South Africa: A preliminary assessment.

- Lechner, A. M., Baumgartl, T., Matthew, P., & Glenn, V. (2016). The impact of underground longwall mining on prime agricultural land: a review and research agenda. Land Degradation & Development, 27(6), 1650-1663. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., Lu, H., Wang, W., Feng, S., & Lei, K. (2021). Ecological risk assessment of heavy metal contamination of mining area soil based on land type changes: An information network environ analysis. Ecological Modelling, 455, 109633. [CrossRef]

- Mabaso, S. M. (2023). Legacy gold mine sites & dumps in the Witwatersrand: Challenges and required action. Natural Resources, 14(5), 65-77. [CrossRef]

- Magagula, M., Atangana, E., & Oberholster, P. (2024). Assessment of the Impact of Coal Mining on Water Resources in Middelburg, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa: Using Different Water Quality Indices. Hydrology, 11(8), 113. [CrossRef]

- Mahar, A., Wang, P., Ali, A., Awasthi, M. K., Lahori, A. H., Wang, Q., ... & Zhang, Z. (2016). Challenges and opportunities in the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soils: A review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 126, 111-121. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, P. M., Groffman, P. M., Striz, E. A., & Kaushal, S. S. (2010). Nitrogen dynamics at the groundwater–surface water interface of a degraded urban stream. Journal of Environmental Quality, 39(3), 810-823. [CrossRef]

- Midgley, D.C.; Pitman, W.V.; Middleton, B.J. (1990). Surface Water Resources of South Africa; WRC Report No 298/1.1/94; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, Volume 1. 30.

- Minerals Council of South Africa. (2018). Facts and Figures Pocketbook 2018. https://www.mineralscouncil.org.za/industry-news/publications/facts-and-figure.

- Minerals Council South Africa. 2023. Facts & Figures Pocketbook 2022. Johannesburg.

- Mishra, Saurabh, M. P. Sharma, and Amit Kumar. "Assessment of surface water quality in Surha Lake using pollution index, India." Journal of Material and Environmental Science 7 (2016): 713-719.

- Mlalazi, N., Chimuka, L., & Simatele, M. D. (2024). Synergistic effect of compost and moringa leaf extract biostimulants on the remediation of gold mine tailings using chrysopogon zizanioides. Scientific African, 26, e02358.Mosley, L. M., Biswas, T. K., Dang, T., Palmer, D., Cummings, C., Daly, R., ... & Kirby, J. (2018). Fate and dynamics of metal precipitates arising from acid drainage discharges to a river system. Chemosphere, 212, 811-820. [CrossRef]

- Mosai, A. K., Ndlovu, G., & Tutu, H. (2024). Improving acid mine drainage treatment by combining treatment technologies: A review. Science of The Total Environment, 919, 170806. [CrossRef]

- Mpanza, M., Adam, E., & Moolla, R. (2021). A critical review of the impact of South Africa’s mine closure policy and the winding-up process of mining companies. The journal for transdisciplinary research in Southern Africa, 17(1), 21.

- Mpanza, M., Adam, E., & Moolla, R. (2020). Dust deposition impacts at a liquidated gold mine village: Gauteng province in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4929. [CrossRef]

- Naidu, G., Ryu, S., Thiruvenkatachari, R., Choi, Y., Jeong, S., & Vigneswaran, S. (2019). A critical review on remediation, reuse, and resource recovery from acid mine drainage. Environmental pollution, 247, 1110-1124.

- Oberholster, P. F., Goldin, J., Xu, Y., Kanyerere, T., Oberholster, P. J., & Botha, A. M. (2021). Assessing the adverse effects of a mixture of AMD and sewage effluent on a sub-tropical dam situated in a nature conservation area using a modified pollution index. International Journal of Environmental Research, 15, 321-333. [CrossRef]

- Orem, W. H., & Finkelman, R. B. (2003). Coal formation and geochemistry. In Treatise on Geochemistry (Vol. 7, pp. 191-222). Elsevier.

- Pei, W., Yao, S., Knight, J. F., Dong, S., Pelletier, K., Rampi, L. P., ... & Klassen, J. (2017). Mapping and detection of land use change in a coal mining area using object-based image analysis. Environmental Earth Sciences, 76, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, W. and le Roux, M. (2023). Statistics of utility-scale power generation in South Africa. CSIR Energy Centre,Pretoria. https://researchspace.csir.co.za/dspace/bitstream/handle/10204/12067/Statistics_of_utility-scale_powergeneration_in_South_Africa_.

- Ramla, B., & Sheridan, C. (2015). The potential utilisation of indigenous South African grasses for acid mine drainage remediation. Water SA, 41(2), 247-252. [CrossRef]

- Reddick, J. (2016). Environmental impacts of coal mining. International Journal of Coal Geology, 157, 104-123.

- Richardson, D. M., & Van Wilgen, B. W. (2004). Invasive alien plants in South Africa: how well do we understand the ecological impacts?: working for water. South African Journal of Science, 100(1), 45-52. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC96214.

- Rouhani, S., Zhang, Y., & Liu, X. (2023). Heavy metal pollution in soil and its impact on human health: A review. Science of the Total Environment, 858, 159746.

- Rutherford, M. C., Mucina, L., & Powrie, L. W. (2006). Biomes and bioregions of southern Africa. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland, 19, 30-51.

- Sahoo, P. K., Equeenuddin, S. M., & Powell, M. A. (2016). Trace elements in soils around coal mines: current scenario, impact and available techniques for management. Current Pollution Reports, 2, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Santander, M., & Valderrama, L. (2019). Recovery of pyrite from copper tailings by flotation. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 8(5), 4312-4317.

- Sengupta, D., Chen, R., & Meadows, M. E. (2018). Building beyond land: An overview of coastal land reclamation in 16 global megacities. Applied geography, 90, 229-238.

- Shi, J., Qian, W., Jin, Z., Zhou, Z., Wang, X., & Yang, X. (2023). Evaluation of soil heavy metals pollution and the phytoremediation potential of copper-nickel mine tailings ponds. PLoS One, 18(3), e0277159.

- Shi, G. L., Lou, L. Q., Zhang, S., Xia, X. W., & Cai, Q. S. (2013). Arsenic, copper, and zinc contamination in soil and wheat during coal mining, with assessment of health risks for the inhabitants of Huaibei, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 20, 8435-8445. [CrossRef]

- Sigua, G. C., & Tweedale, W. A. (2003). Watershed scale assessment of nitrogen and phosphorus loadings in the Indian River Lagoon basin, Florida. Journal of environmental management, 67(4), 363-372. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G. B., Badenhorst, J., Jewitt, G. P., Berchner, M., & Davies, E. (2019). Competition for land: The water-energy-food nexus and coal mining in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 7, 86. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. K., Singh, K. P., & Mohan, D. (2005). Status of heavy metals in water and bed sediments of river Gomti–A tributary of the Ganga river, India. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 105, 43-67.

- Skousen, J., Zipper, C. E., Rose, A., Ziemkiewicz, P. F., Nairn, R., McDonald, L. M., & Kleinmann, R. L. (2017). Review of passive systems for acid mine drainage treatment. Mine Water and the Environment, 36(1), 133-153.Son, C. T., Giang, N. T. H., Thao, T. P., Nui, N. H., Lam, N. T., & Cong, V. H. (2020). Assessment of Cau River water quality assessment using a combination of water quality and pollution indices. Journal of Water Supply: Research and Technology—AQUA, 69(2), 160-172.

- Song, W., Xu, R., Li, X., Min, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, H., ... & Li, J. (2023). Soil reconstruction and heavy metal pollution risk in reclaimed cultivated land with coal gangue filling in mining areas. Catena, 228, 107147. [CrossRef]

- South African Weather Service. Climate Data for Mpumalanga; South African Weather Service: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023.

- Steyn, C. E., & Herselman, J. E. (2006). Trace element concentrations in soils under different land uses in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. South African Journal of Plant and Soil, 23(4), 230-236. [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, D. (2020). Australian resource reviews: iron ore 2019. (No Title).

- Uddin, M. G., Nash, S., & Olbert, A. I. (2021). A review of water quality index models and their use for assessing surface water quality. Ecological Indicators, 122, 107218. [CrossRef]

- Ukhurebor, K. E., Aigbe, U. O., Onyancha, R. B., Ndunagu, J. N., Osibote, O. A., Emegha, J. O., ... & Darmokoesoemo, H. (2022). An overview of the emergence and challenges of land reclamation: Issues and prospect. Applied and Environmental Soil Science, 2022(1), 5889823.

- van Wilgen, B. W., Richardson, D. M., Le Maitre, D. C., Marais, C., & Magadlela, D. (2001). The economic consequences of alien plant invasions: examples of impacts and approaches to sustainable management in South Africa. Environment, development and sustainability, 3, 145-168. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X., Lei, M., & Chen, T. (2016). Cost–benefit calculation of phytoremediation technology for heavy-metal-contaminated soil. Science of the total environment, 563, 796-802.

- Wen, H., Zhang, Y., Cloquet, C., Zhu, C., Fan, H., & Luo, C. (2015). Tracing sources of pollution in soils from the Jinding Pb–Zn mining district in China using cadmium and lead isotopes. Applied Geochemistry, 52, 147-154. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.G.C.; Anhaeusser, C.R. The Mineral Resources of South Africa, 6th ed.; Handbook 16; Council for Geoscience: Pretoria, South Africa, 1998.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017). Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th edition.

- Xiao, X., Zhang, J., Wang, H., Han, X., Ma, J., Ma, Y., & Luan, H. (2020). Distribution and health risk assessment of potentially toxic elements in soils around coal industrial areas: A global meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 713, 135292. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., & van Zyl, D. (2020). Distinguishing reclamation, revegetation and phytoremediation, and the importance of geochemical processes in the reclamation of sulfidic mine tailings: A review. Chemosphere, 252, 126446.

- Yadav, H. L., & Jamal, A. (2018). Assessment of water quality in coal mines: a quantitative approach.

- Yakovleva, E. V., Gabov, D. N., Beznosikov, V. A., & Kondratenok, B. M. (2016). Accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils and plants of the tundra zone under the impact of coal-mining industry. Eurasian Soil Science, 49, 1319-1328. [CrossRef]

- Ying, H., Zhao, W., Feng, X., Gu, C., & Wang, X. (2022). The impacts of aging pH and time of acid mine drainage solutions on Fe mineralogy and chemical fractions of heavy metals in the sediments. Chemosphere, 303, 135077.

- Zerizghi, T., Guo, Q., Tian, L., Wei, R., & Zhao, C. (2022). An integrated approach to quantify ecological and human health risks of soil heavy metal contamination around coal mining area. Science of the Total Environment, 814, 152653. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Xue, S., Wu, J., & Chang, L. (2017). Study on the relationship between microscopic functional group and coal mass changes during low-temperature oxidation of coal. International Journal of Coal Geology, 171, 212-222. [CrossRef]

- Zocche, J. J., Sehn, L. M., Pillon, J. G., Schneider, C. H., Olivo, E. F., & Raupp-Pereira, F. (2023). Technosols in coal mining areas: Viability of combined use of agro-industry waste and synthetic gypsum in the restoration of areas degraded. Cleaner Engineering and Technology, 13, 100618. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Locality map of the geographic location of portion 60 of Farm 313 JS KwaGuqa (the study site), generated using ArcGIS (left), and photographic representation of the abandoned open-cast mine site, showing unlevelled ground, coal remnant and eroded stockpiles or overburden evident. A stream runs along the western edge, with the invasive alien tree species dominating the riparian zone (right). A nearby community is situated approximately 10 meters from the stream, although not visible in this image .

Figure 1.

Locality map of the geographic location of portion 60 of Farm 313 JS KwaGuqa (the study site), generated using ArcGIS (left), and photographic representation of the abandoned open-cast mine site, showing unlevelled ground, coal remnant and eroded stockpiles or overburden evident. A stream runs along the western edge, with the invasive alien tree species dominating the riparian zone (right). A nearby community is situated approximately 10 meters from the stream, although not visible in this image .

Figure 2.

Surface water and soil sampling points within the study site and the water drainage system.

Figure 2.

Surface water and soil sampling points within the study site and the water drainage system.

Figure 3.

Values of pH (A), electrical conductivity (EC) (B), the concentrations of ammonia (NH3) (C) and sulfate (SO4) (D) at farm 313, an abandoned coal mine at KwaGuqa, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Sampling was done in March 2025.

Figure 3.

Values of pH (A), electrical conductivity (EC) (B), the concentrations of ammonia (NH3) (C) and sulfate (SO4) (D) at farm 313, an abandoned coal mine at KwaGuqa, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Sampling was done in March 2025.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of (A) calcium, (B) iron, (C) magnesium and manganese, and(D) lead at the study site.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of (A) calcium, (B) iron, (C) magnesium and manganese, and(D) lead at the study site.

Figure 5.

Alien and invasive plant species concentrated on the western side of the study site where the soil sample S5 was taken from, adjacent to a water course.

Figure 5.

Alien and invasive plant species concentrated on the western side of the study site where the soil sample S5 was taken from, adjacent to a water course.

Figure 6.

Values of (A) pH, (B) electrical conductivity (EC), the concentrations of (C) total dissolved solids (TDS), (D) total suspended solids and (E) sulfate (SO4) in the water samples against the livestock watering (LW), discharge general standard (DGS), irrigation general standard (IGS), Domestic Use SANAS 241(15) (SANAS).

Figure 6.

Values of (A) pH, (B) electrical conductivity (EC), the concentrations of (C) total dissolved solids (TDS), (D) total suspended solids and (E) sulfate (SO4) in the water samples against the livestock watering (LW), discharge general standard (DGS), irrigation general standard (IGS), Domestic Use SANAS 241(15) (SANAS).

Figure 7.

Concentrations of (A) calcium, (B) iron, (C) magnesium and (D) manganese in the water samples from the study site against the livestock watering department of water and sanitation (LW-DWA), aquatic ecosystem DWA (AE-DWA), discharge general standard (DGS), irrigation general standard (IGS), Domestic Use SANAS 241(15) (SANAS).

Figure 7.

Concentrations of (A) calcium, (B) iron, (C) magnesium and (D) manganese in the water samples from the study site against the livestock watering department of water and sanitation (LW-DWA), aquatic ecosystem DWA (AE-DWA), discharge general standard (DGS), irrigation general standard (IGS), Domestic Use SANAS 241(15) (SANAS).

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the soils and the soil screening values.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the soils and the soil screening values.

| |

SSV1 All land uses Protective of the water resources |

Protection of the Ecosystem Health (SSV3) |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

| pH |

|

|

4.16 |

4.99 |

4.22 |

3.82 |

4.66 |

| EC (mS/m) |

|

|

14.5 |

1.6 |

14.2 |

27.4 |

34.7 |

| NH3 as N |

|

|

41.04 |

11.67 |

14.61 |

15.89 |

53.94 |

| SO4 |

4000 |

|

2648.00 |

<200 |

1815.00 |

6130.00 |

12868.00 |

| Ca |

|

|

3307.00 |

225.70 |

600.80 |

1930.00 |

4562.00 |

| Fe |

|

|

9373.00 |

15176.00 |

25573.00 |

24781.00 |

58497.00 |

| Mg |

|

|

81.08 |

73.43 |

73.95 |

125.50 |

164.40 |

| Mn |

740 |

36 000 |

67.82 |

54.53 |

45.44 |

64.17 |

43.70 |

| Pb |

20 |

100 |

13.83 |

8.61 |

13.83 |

45.48 |

29.76 |

Table 2.

Concentrations of the water parameters measured at the study site.

Table 2.

Concentrations of the water parameters measured at the study site.

| |

Discharge General Standard (mg/l) |

Irrigation General Standard (mg/l) |

Livestock watering (DWA) (mg/l) |

Aquatic ecosystem (DWA) (mg/l) |

Domestic Use SANAS 241(15) (mg/l) |

W1

(mg/l) |

W2

(mg/l) |

W3

(mg/l) |

W4

(mg/l) |

| pH |

5.5-9.5 |

5.5-9.5 |

- |

- |

5-9.7 |

3.41 |

3.39 |

3.64 |

3.76 |

| EC * |

150 |

150 |

- |

- |

≤170 |

314.0 |

257.9 |

130.0 |

124.2 |

| TDS |

- |

- |

≤2000 |

- |

≤2000 |

3337 |

2803 |

1226 |

1093 |

| TSS |

25 |

25 |

- |

- |

- |

670 |

437 |

385 |

360 |

| SO4 |

- |

- |

≤1500 |

- |

≤500 |

1955.00 |

1766.00 |

731.40 |

681.00 |

| Ca |

- |

- |

≤1000 |

- |

- |

647.70 |

367.40 |

156.10 |

140.20 |

| Fe |

0.3 |

- |

- |

- |

≤2 |

2.95 |

1.95 |

7.73 |

4.93 |

| Mg |

- |

- |

≤500 |

- |

- |

60.42 |

64.96 |

20.08 |

20.88 |

| Mn |

0.1 |

- |

≤10 |

≤0.18 |

≤0.5 |

12.86 |

12.64 |

10.23 |

10.57 |

| Pb |

0.01 |

0.01 |

≤0.1 |

≤0.0012 |

≤0.01 |

<0.05 |

<0.05 |

<0.05 |

<0.05 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).