Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Data Analysis

3. Impact on Aquatic Ecosystems

3.1. Water Contamination

3.2. Habitat Destruction

3.3. Alteration of Hydrological Cycles

3.4. Biodiversity Loss

4. Mitigation Strategies

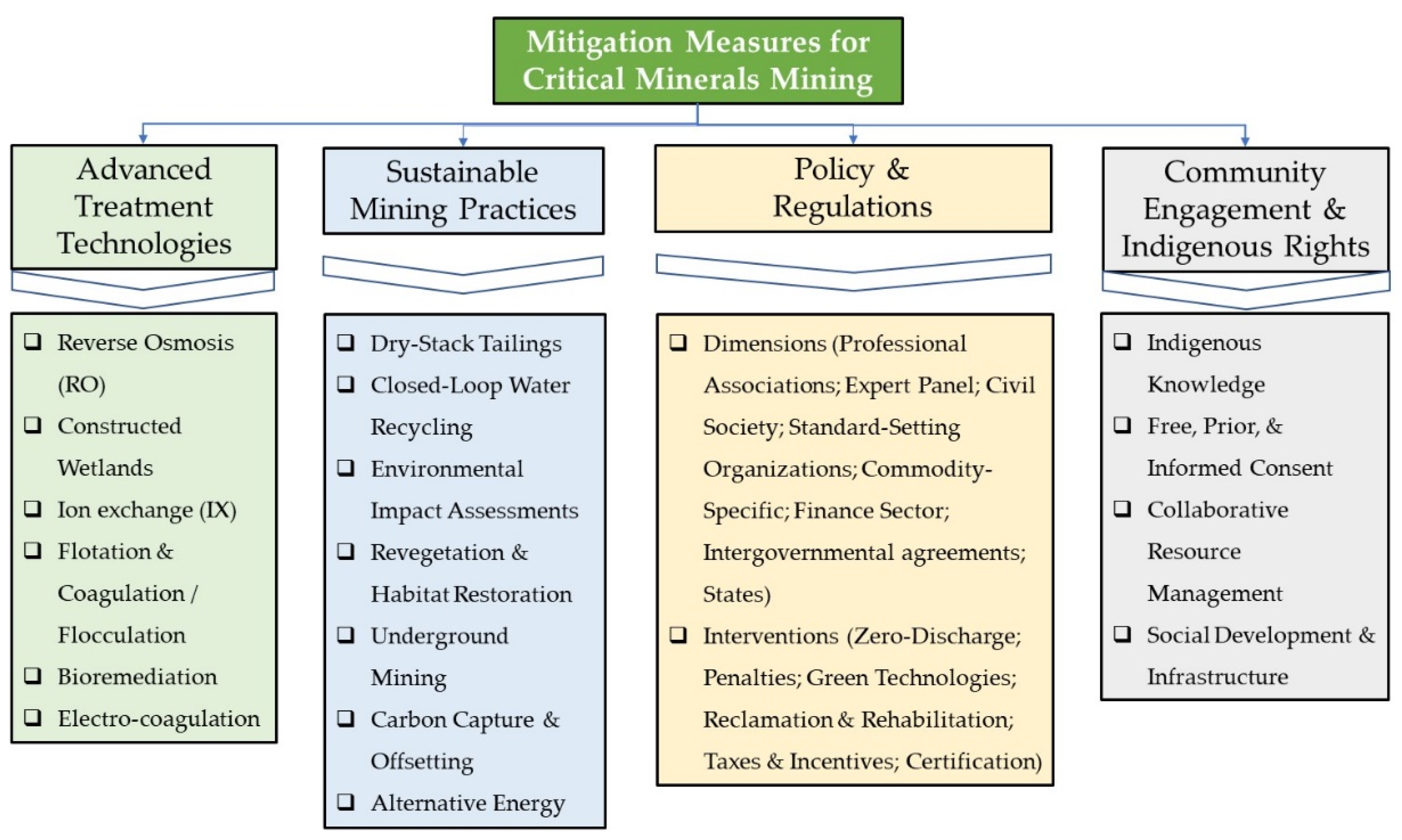

- Advanced treatment technologies focus on reducing water contamination and improving waste management through methods like reverse osmosis, constructed wetlands, ion exchange, flotation, bioremediation, and electro-coagulation.

- Sustainable mining practices emphasize environmentally responsible extraction methods, such as dry-stack tailings, closed-loop water recycling, revegetation, underground mining, carbon capture, and alternative energy sources.

- Policy and regulations outline the institutional and regulatory frameworks that govern mining activities. This includes professional associations, expert panels, civil society involvement, standard-setting organizations, intergovernmental agreements, and economic interventions like zero-discharge policies, penalties, incentives, and reclamation strategies.

- Community engagement and indigenous rights recognize the importance of Indigenous knowledge, free, prior, and informed consent, collaborative resource management, and social development to ensure fair and sustainable mining practices.

4.1. Advanced Water Treatment Technologies

4.2. Sustainable Mining Practices

4.2.1. Dry-stack Tailings

4.2.2. Closed-loop Water Recycling Systems

4.2.3. Conducting Detailed Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs)

4.2.4. Other Sustainable Practices

4.3. Policy and Regulations

4.3.1. Regulatory Dimensions

4.3.2. Regulatory Interventions

4.3.2.1. Mandating Zero-Discharge Policies

4.3.2. Imposing Penalties for Non-Compliance

4.3.3. Encouraging the Adoption of Green Mining Technologies

4.3.4. Other Regulatory and Policy Interventions

4.4. Community Engagement and Indigenous Rights

4.4.1. Incorporating Indigenous Knowledge in Conservation Strategies

4.4.2. Ensuring Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC)

4.4.3. Promoting Collaborative Resource Management

4.4.4. Investing in Social Development and Infrastructure

5. Summary, the Way Forward, Conclusion and Vision for the Future

5.1. Summary

5.2. The Way Forward:

- Strengthening policy and regulatory frameworks: Governments and international bodies must prioritize the implementation of stringent environmental regulations that hold mining companies accountable for their water use and discharge practices. Zero-discharge policies, mandatory environmental impact assessments (EIAs), and penalties for non-compliance should be enforced to ensure that mining operations minimize their environmental footprint. Governments should support the transition toward green mining technologies by offering incentives, such as tax credits or grants, for companies that invest in sustainable practices, water treatment systems, and eco-friendly extraction methods. International collaboration is crucial to align global mining standards and create a unified regulatory framework that addresses the environmental impacts of mining on aquatic ecosystems.

- Promoting sustainable mining practices: Mining companies must adopt sustainable practices such as dry-stack tailings and closed-loop water recycling to reduce their water consumption and prevent contamination. These methods can help conserve precious water resources, especially in regions where water scarcity is a growing concern. Mining projects should be required to conduct comprehensive EIAs that evaluate the potential effects of mining on local ecosystems, hydrological cycles, and aquatic biodiversity. This proactive approach will enable the identification of potential risks before mining begins and allow for effective mitigation measures to be implemented early on.

- Investing in advanced water treatment technologies: To address the severe contamination of water resources, mining operations must implement advanced water treatment technologies to reduce contaminants in mining effluents. Techniques such as reverse osmosis, chemical precipitation, and bioremediation can effectively treat toxic discharges, ensuring that mining effluents meet environmental standards before they are released into the surrounding ecosystem. Research and development in eco-friendly mining technologies should be prioritized to minimize environmental harm. These technologies could include the use of biodegradable chemicals in ore processing, the development of non-toxic alternatives to mercury in gold mining, and the introduction of low-impact mining techniques that reduce waste generation.

- Ensuring community engagement and indigenous rights: Involving local and indigenous communities in decision-making processes is crucial for ensuring that mining projects respect both environmental and social considerations. Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) must be upheld as a core principle to guarantee that communities have the right to approve or reject projects that affect their lands and resources. Collaborative resource management models, where mining companies work alongside indigenous peoples and local communities to manage water resources and biodiversity, should be encouraged. By integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern scientific practices, these partnerships can foster more sustainable and effective conservation strategies.

- Enhancing transparency and accountability: Transparency in mining operations is essential for building trust with local communities and governments. Companies should be required to adopt international reporting standards for environmental performance, social impacts, and water use. Independent third-party audits can verify compliance with environmental regulations and ensure that companies are meeting their obligations. Accountability mechanisms, including community monitoring and stakeholder oversight, can help ensure that mining companies adhere to their environmental commitments. Local communities should be empowered to monitor mining impacts and report violations, creating a system of checks and balances that holds companies accountable.

- Adaptation to climate change and long-term resilience: Mining operations must recognize the growing risks posed by climate change, including shifting weather patterns, extreme flooding, and water shortages. Companies should adopt adaptive management strategies that allow them to respond to these challenges and ensure that their operations remain resilient in the face of environmental stressors. Long-term planning should include strategies for the reclamation and restoration of mining-impacted areas, particularly aquatic ecosystems that have been degraded. Restoring wetlands, riparian zones, and aquatic habitats should be prioritized as part of the closure and post-mining phase.

5.3. Conclusion and Vision for the Future:

Author Contributions

References

- Abiye, T.A.; and Ali, K.A. (2022). Potential role of acid mine drainage management towards achieving sustainable development in the Johannesburg region South Africa. Groundw Sustain Dev 19:100839. [CrossRef]

- Adeola, A.O., and Forbes, P.B.C. (2020). Advances in water treatment technologies for removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Existing concepts, emerging trends, and future prospects, Water Environment Research 2020: 1–17.

- Agincourt Resources (2023). Constructed wetland technology for mining wastewater treatment, Mar 5, 2023; (https://agincourtresources.com/2023/03/05/constructed-wetland-technology-for-mining-wastewater-treatment/) Accessed 12 January, 2025.

- Agussalim, M.S., Ariana, A., and Saleh, R. (2023). Kerusakan Lingkungan Akibat Pertambangan Nikel di Kabupaten Kolaka melalui Pendekatan Politik Lingkungan. Palita: Journal of Social Religion Research 8(1): 37–48. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B., and Wood, C. (2002). A comparative evaluation of the EIA systems in Egypt, Turkey and Tunisia. Environ. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2002, 22, 213–234.

- Ahmad, T., and Ferdausi, S.A. (2016). Evaluation of EIA system in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference of the International Association of Impact Assessment, Nagoya, Japan, 11–14 May 2016.

- Akagi, T., and Edanami, K. (2017). Sources of rare earth elements in shells and soft tissues of bivalves from Tokyo Bay. Mar. Chem. 2017, 194, 55–62.

- Akpan, L., Tse, A.C., Giadom, F.D., and Adamu, C.I. (2021). Chemical characteristics of discharges from two derelict coal mine sites in enugu Nigeria: implication for pollution and acid mine drainage. J Mining Environ 12:89–111. [CrossRef]

- Alam, P.N., Yulianis, Pasya, H.L., Aditya, R., Aslam, I.N., and Pontas, K. (2022). Acid mine wastewater treatment using electrocoagulationmethod. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 63, S434–S437.

- Al-Azria, N.S., Al-Busaidia1, R.O., Sulaiman, H., and Al-Azri, A.R. (2013). Comparative evaluation of EIA systems in the Gulf Cooperation Council States. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 32, 136–149.

- Alkherraz, A.M., Ali, A.K., and Elsherif, K.M. (2020). Removal of Pb(II), Zn(II), Cu(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto olive branches activated carbon: Equilibrium and thermodynamic studies, Chemistry International 2020, 6(1): 11-20.

- Amira Global (2020). Amira Global. [Online]. Available at: https://amira.global/ (accessed 28 january 2025).

- Anandkumar, J., Chaterjee, T., and Sahariah, B.P. (2022). Bioremediation techniques for the treatment of mine tailings: A review. June 2022, Soil Ecology Letters. [CrossRef]

- Anastassakis, G., Karageorgiou, K., and Paschalis, M. (2004). Removal of phosphates species from solution by flotation, In: Gaballah, I. et al., (eds.), Proceedings of “REWAS 04”: Global Symposium on Recycling and Clean technology, Vol. II, 26 September 2004, Spain, 2004, pp.1147-1154.

- Anglo American (2022). Anglo American unveils a prototype of the world’s largest hydrogen-powered mine haul truck - a vital step towards reducing carbon emissions over time. [Online]. Available at: https://www.angloamerican.com/media/press-releases/2022/06-05-2022 (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- Angloamerican.com (2023a).Thriving Communities. [Online]. Available at: https://www.angloamerican.com/sustainable-mining-plan/thriving-communities (Accessed 25 January 2025).

- Angloamerican.com (2023b). Collaborative Regional Development. [Online]. Available at: https://www.angloamerican.com/sustainable-mining-plan/collaborative-regional-development (Accessed 25 January 2025).

- Angloamerican.com (2024). Project roundup: Giving back to host communities. [Online]. Available at: https://www.angloamerican.com/our-stories/communities/project-roundup-giving-back-to-host-communities (Accessed 25 January 2025).

- Annandale, D. (2001). Developing and evaluating environmental impact assessment systems for small developing countries. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2001, 19, 187–193.

- Ansu-Mensah, P., Marfo, E.O., Awuah, L.S., and Amoako, K.O. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder engagement in Ghana’s mining sector: a case study of Newmont Ahafo mines. Int J Corporate Soc Responsibility, 6, 1 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ashton, P.J., Love, D., Mahachi, H., and Dirks, P.H.G.M. (2001). An Overview of the Impact of Mining and Mineral Processing Operations on Water Resources and Water Quality in the Zambezi, Limpopo and Olifants Catchments in Southern Africa. Contract Report to the Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development (SOUTHERN AFRICA) Project, by CSIREnvironmentek, Pretoria, South Africa and Geology Department, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe. Report No. ENV-P-C 2001-042. xvi + 336 pp.

- ASI, Aluminium Stewardship Initiative (2023). ASI Standards Overview. [Online]. Available at: https://aluminiumstewardship.org/asi-standards/overview. Accessed 30 November 2023. 2023.

- Aung, T.S. (2017). Evaluation of the environmental impact assessment system and implementation in Myanmar: Its significance in oil and gas industry. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 66, 24–32. [CrossRef]

- Austmine (2020). Austmine. [Online]. Available at: http://www.austmine.com.au/.

- Australian Government (2016). Tailings Management: Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program for the Mining Industry. Canberra. [Online]. Available at: https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-04/lpsdp-tailingsmanagement-handbook-english.pdf.

- Australian Government (2025). Industry Growth Centres Initiative: Background Information for Australian Research Council Industrial Transformation Research Program Applicants. [Online]. Available at: https://www.arc.gov.au/industry-growth-centres-initiative (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- Babidge, S. (2016). Contested value and an ethics of resources: water, mining and indigenous people in the Atacama desert, Chile. Aus. J. Anthrop. 27(1), 84–103. [CrossRef]

- Babidge, S., and Bolados, P. (2018). Neoextractivism and Indigenous Water Ritual in Salar de Atacama, Chile. Lat. Am. Perspect. 45(5), 170–185. [CrossRef]

- Badr, E.A. (2009). Evaluation of the environmental impact assessment system in Egypt. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 193–203. [CrossRef]

- Banza, C.L.N., Nawrot, T.S., Haufroid, V., Decrée, S., De Putter, T., Smolders, E., Kabyla, B.I., Luboya, O.N., Ilunga, A.N., and Mutombo, A.M. (2009). High human exposure to cobalt and other metals in Katanga, a mining area of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 745–752.

- BC Ministry of Energy and Mines (2017). Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia (Victoria, BC: Ministry of Energy and Mines). [Online]. Available at: www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/mineral-exploration-mining/health-safety/health-safety-and-reclamation-code-for-mines-in-british-columbia (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Benzal, E., Solé, M., and Lao, C. (2020). Elemental copper recovery from e-wastes mediated with a two-step bioleaching process Waste and Biomass Valorization 11 5457 5465. [CrossRef]

- Beylot, A., Bodénan, F., Guezennec, A-G. and Muller, S. (2022). LCA as a support to more sustainable tailings management: critical review, lessons learnt and potential way forward. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 183, 106347. [CrossRef]

- BHP (2024). FY24 Australian Indigenous Social Investment Report. [Online]. Available at: https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/ourapproach/operatingwithintegrity/indigenouspeoples/241126_bhpfy24australianindigenoussocialinvestmentreport.pdf (Accessed 25 January 2025).

- Bidul, S., and Zaid, Z. (2024). Analisis Yuridis Dampak Pencemaran Lingkungan Pertambangan Mangan dan Nikel di Provinsi Maluku Utara. Justisi 9(3), 412–426. [CrossRef]

- Bjelkevik, A. (2023). ICOLD Bulletin No. 194. Tailings Dam Safety. PowerPoint presentation. International Commission on Large Dams. [Online]. Available at: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/8_2_Annika%20Bjelkevik_ENG.pdf.

- Bnamericas (2023).Brazil’s Vale steps up focus on innovation, sustainability. [Online]. Available at: https://www.bnamericas.com/en/news/brazils-vale-steps-up-focus-on-innovation-sustainability (Accessed 25 January 2025).

- Boening, D.W. (2000). Ecological effects, transport, and fate of mercury: a general review. Chemosphere. 2000 Jun;40(12),1335-51. [CrossRef]

- Bose, D., Bhattacharya, R., Kaur, T., Pandya, R., Sarkar, A., Ray, A., Mondal, S., Mondal, A., Ghosh, P., and Chemudupati, R.I., (2024).Innovative approaches for carbon capture and storage as crucial measures for emission reduction within industrial sectors, Carbon Capture Science & Technology, 12, 2024, 100238, ISSN 2772-6568. [CrossRef]

- Bose-O’Reilly, S., Lettmeier, B., Gothe, R.M., Beinhoff, C., Siebert, U., and Drasch, G. (2008). Mercury as a serious health hazard for children in gold mining areas. Environ Res. 2008 May;107(1):89-97. [CrossRef]

- Bosse, M.A., Schneider, H., and Cortina, J.L. (2007). Treatment and reutilization of liquid effluents of copper mining in desert zones, Water Sustainability and Integrated Water Resource Management, The Preliminary Program for 2007 Annual Meeting, 2007. [Online] Available at: http://aiche.confex.com/aiche/2007/preliminaryprogram/abstract_101082.htm.

- Boulot, E., and Collins, B. (2023). Regulating Mine Rehabilitation and Closure on Indigenous Held Lands: Insights from the Regulated Resource States of Australia and Canada”, International Development Policy | Revue internationale de politique de développement [Online], 16, 2023, Online since 12 June 2023, connection on 22 January 2025. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/poldev/5319. [CrossRef]

- Boulot, E., and Collins, B. (2023). Regulating Mine Rehabilitation and Closure on Indigenous Held Lands: Insights from the Regulated Resource States of Australia and Canada. International Development Policy | Revue internationale de politique de développement [Online], 16, 2023, Online since 12 June 2023, connection on 22 January 2025. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/poldev/5319. [CrossRef]

- BP Berau Ltd. (2016). Draft Resettlement and Indigenous People Plan: INO: Tangguh LNG Expansion Project. [Online]. Available at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents//49222-001-remdp-01.pdf (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- Brahmi, K., Bouguerra, W., Hamrouni, B., Elaloui, E., Loungou, M., and Tlili, Z. (2019). Investigation of electrocoagulation reactor design parameters effect on the removal of cadmium from synthetic and phosphate industrial wastewater. Arab. J. Chem. 2019,12, 1848–1859.

- Bredariol, D.O.T. (2022) Reducing the Impact of Extractive Industries on Groundwater Resources International Energy Agency Paris, France. [Online]. Available at: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/reducing-the-impact-of-extractive-industries-on-groundwater-resources (accessed 03/01/2024).

- Brock, T., Reed, M.G., and Stewart, K.J. (2023). A practical framework to guide collaborative environmental decision making among Indigenous Peoples, corporate, and public sectors. The Extractive Industries and Society 14(2), 101246. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., Boyd, D.S., and Kara, S. (2022). Landscape analysis of cobalt mining activities from 2009 to 2021 using very high-resolution satellite data (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Sustainability 2022, 14, 9545. [CrossRef]

- Burritt, R. L., and Christ, K. L. (2021). Full cost accounting: A missing consideration in global tailings dam management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 321, 129016. [CrossRef]

- Cacciuttolo, C., and Cano, D. (2022). environmental impact assessment of mine tailings spill considering metallurgical processes of gold and copper mining: Case studies in the Andean Countries of Chile and Peru. Water 2022, 14, 3057. [CrossRef]

- Censi, P., Randazzo, L.A., D’Angelo, S., Saiano, F., Zuddas, P., Mazzola, S., and Cuttitta, A. (2013). Relationship between lanthanide contents in aquatic turtles and environmental exposures. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 1130–1135.

- Cheyns, K., Banza Lubaba Nkulu, C., Ngombe, L.K., Asosa, J.N., Haufroid, V., De Putter, T., Nawrot, T., Kimpanga, C.M., Numbi, O.L., Ilunga, B.K., Nemery, B., and Smolders, E. (2014). Pathways of human exposure to cobalt in Katanga, a mining area of the D.R. Congo. Sci Total Environ. 2014 Aug 15;490:313-21. [CrossRef]

- China Water Risk (2016). Rare earths: shades of grey Can China Continue To Fuel Our Global Clean & Smart Future. [On line] Available at: https://www.chinawaterrisk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/CWR-Rare-Earths-Shades-Of-Grey-2016-ENG.pdf (accessed 09 January 2025).

- Colorado School of Mines (2025). Mechanical Dewatering of Mine Tailings. [On line] Available at: https://www.mines.edu/capstoneseniordesign/project/mechanical-dewatering/; (Accessed 21 January 2025).

- Congressional Research Service (2021). Alaska Native Lands and the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). [On line] Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46997#:~:text=At%20the%20time%20of%20its,which%20they%20lived%20for%20generations. (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- Corin, K.C., Reddy, A., Miyen, L., Wiese, J.G., and Harris, P.J. (2011). The effect of ionic strength of plant water on valuable mineral and gangue recovery in a platinum bearing ore from the Merensky reef. Miner. Eng. 24, 131e137. [CrossRef]

- Daraz, U., Li, Y., Ahmad, I., Iqbal, R., and Ditta, A. (2023). Remediation technologies for acid mine drainage: Recent trends and future perspectives, Chemosphere,311, Part 2,137089,ISSN 0045-6535. [CrossRef]

- Day, D., and Howe, C. (2003). Forecasting peak demand—What do we need to know? Water Supply 2003, 3, 177–184.

- Deady, E. (2021). Global Rare Earth Element (REE) Mines, Deposits and Occurrences British Geological Survey Keyworth, UK.

- Dibrov, I., Voronin, N., and Klemyatov, A. (1998). Froth flotoextraction - a new method of metal separation from aqueous solutions, International Journal of Minerals Processing 1998; 54: 45-58.

- DMP, Department of Mines and Petroleum, Western Australia (2013). Code of Practice: Tailings Storage Facilities in Western Australia. East Perth: Resources Safety and Environment Divisions. [On line] Available at: https://www.dmp.wa.gov.au/Documents/Safety/MSH_COP_TailingsStorageFacilities.pdf.

- DMP, Department of Mines and Petroleum, Western Australia (2015). Guide to the Preparation of a Design Report for Tailings Storage Facilities (TSFs). East Perth: Resources Safety and Environment Divisions. [On line] Available at: https://www.dmp.wa.gov.au/Documents/Safety/MSH_G_TSFs_PreparationDesignReport.pdf.

- Dong, Y., Di, J., Wang, X., Xue, L., Yang, Z., Guo, X., and Li, D. (2020). Dynamic Experimental Study on Treatment of Acid Mine Drainage by Bacteria Supported in Natural Minerals, Energies 2020; 13(439); 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C., and Whitmore, A. (2014). Indigenous Peoples and the Extractive Sector: Towards a Rights-Respecting Engagement. Baguio: Tebtebba, PIPLinks and Middlesex University. ISBN No: 978-971-0186-20-4; [On line] Available at: https://rightsandresources.org/wp-content/uploads/IPs-and-the-Extractive-Sector-Towards-a-Rights-Respecting-Engagement.pdf (Accessed 24 January 2025).

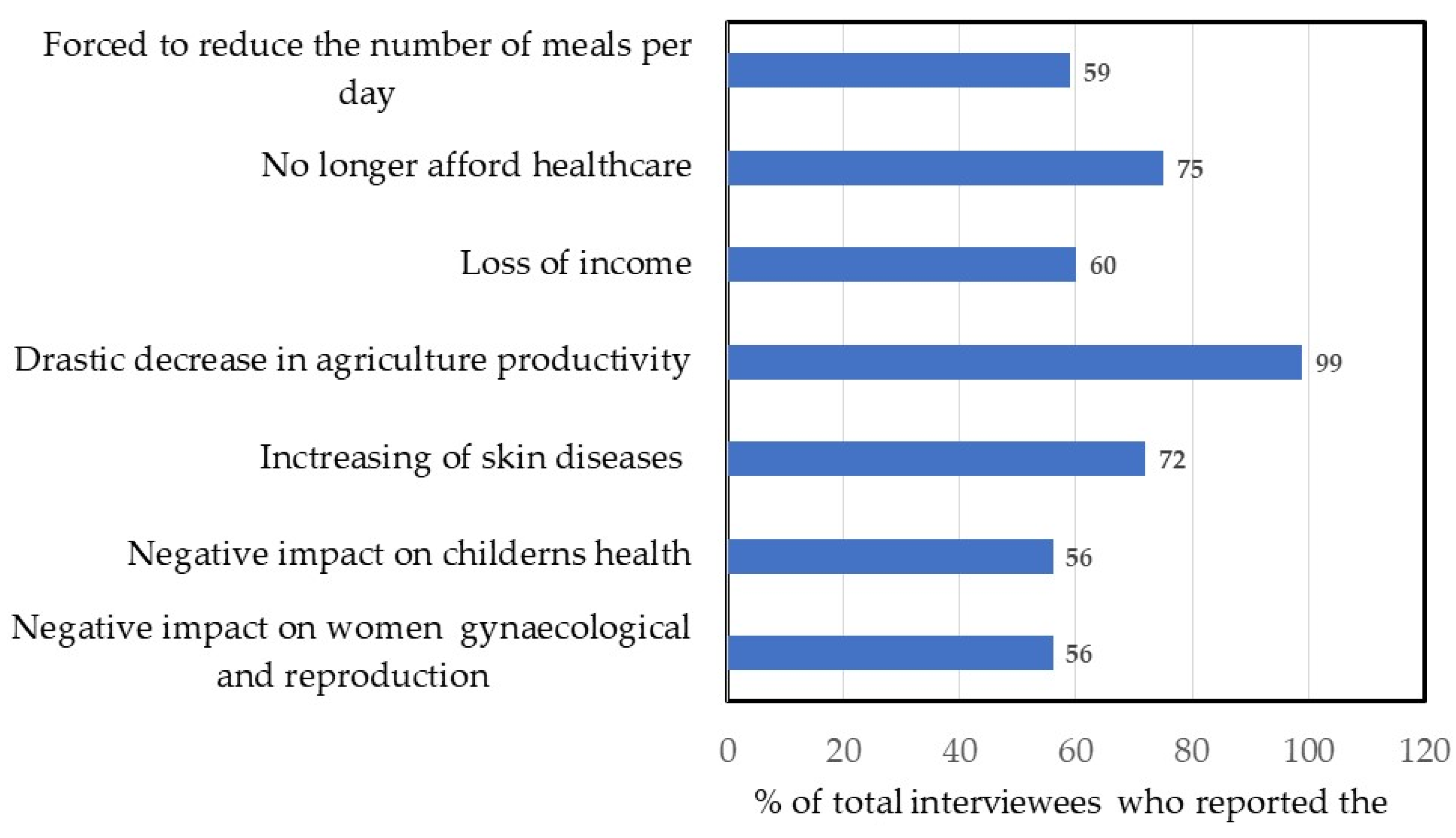

- Egbue, O. (2012). Assessment of social impacts of lithium for electric vehicle batteries. IIE Annu. Conf. Proc. 2012, 1–7.

- Elenge, M.M., and De Brouwer, C. (2011). Identification of hazards in the workplaces of artisanal mining in Katanga. Int. J. Occup. Med.Environ. Health 2011, 24, 57–66.

- El-Fadl, K., and El-Fadel, M. (2004). Comparative assessment of EIA systems in MENA countries: Challenges and prospects. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 553–593.

- Equator Principles (2023). [Online] Available at: https://equator-principles.com. Accessed 5 October 2023.

- Equator Principles (2025).The Equator Principles. [Online] Available at: https://equator-principles.com/ (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- Esdaile, L.J., and Chalker, J.M. (2018). The mercury problem in artisanal and small-scale gold mining. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6905 – 6916. [CrossRef]

- Esdaile, L.J., and Chalker, J.M. (2018). The mercury problem in artisanal and small-scale gold mining. Chemistry. 2018 May 11;24(27):6905-6916. [CrossRef]

- Éthier, M-P. (2011). Évaluation du comportement géochimique en conditions normale et froides de différents stériles présents sur le site de la mine raglan, a thesis in fulfilment of a master’s degree in applied sciences (Mineral Processing), Department of Civil Engineering, Geology and Mines, École Polytechnique de Montréal, 2011, 204p.

- EU, European Union (2018). EN 16907-7:2018. Earthworks – Part 7: Hydraulic Placement of extractive waste. Brussels.

- European Union (2017). Mining Waste Directive 2006/21/EC Assessment. ISBN 978-92-846-0398-5; [Online] Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/593788/EPRS_STU(2017)593788_EN.pdf (Accessed 22 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ezugbe, E.O., and Rathilal, S. (2020). Membrane technologies in wastewater treatment: A review, Membranes 2020;10 (89), 1-28. [CrossRef]

- FAO (2025). ANNEX I: Collaborative natural resource management. [Online] Available at: https://www.fao.org/4/a0032e/a0032e0c.htm (accessed 24 January 2025).

- Farjana, S.H., Huda, N., and Parvez Mahmud, M.A. (2019). Life cycle assessment of cobalt extraction process. Journal of Sustainable Mining 18 (2019) 150–1. [CrossRef]

- Fatta, D, and Kythreotou, N. (2005). Water as valuable water resource- concerns, constraints and requirements related to reclamation, recycling and reuse, Proceedings of IWA International Conference on Water Economics, Statistics, and Finance, Rethymno, Greece, 2005, pp.8-10.

- Figueiredo, C., Grilo, T.F., Lopes, C., Brito, P., Diniz, M., Caetano, M., Rosa, R., and Raimundo, J. (2018). Accumulation, elimination and neuro-oxidative damage under lanthanum exposure in glass eels (Anguilla anguilla). Chemosphere 2018, 206, 414–423.

- Fraser, J. (2021). Mining companies and communities: Collaborative approaches to reduce social risk and advance sustainable development, Resources Policy, 74, 2021, 101144, ISSN 0301-4207. [CrossRef]

- Freeport-McMoRan (2016). Form 10 K. Freeport-McMoRan, Phoenix. [Online] Available at: http://s2.q4cdn.com/089924811/files/doc_financials/quarter/10_ k2016/10_k2016.pdf〉).

- Future Bridge Mining (2025). Five ways to make mining more sustainable. [Online] Available at: https://mining-events.com/5-ways-to-make-mining-more-sustainable/ (Accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Gajardo, G., and Redón, S. (2019). Andean hypersaline lakes in the Atacama Desert , northern Chile: Between lithium exploitation and unique biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 1(9). [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, E., Orveillon, G., Saveyn, H., Barthe, P. and Eder, P. (2018). Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Management of Waste from Extractive Industries, in accordance with Directive 2006/21/EC; EUR 28963 EN. , Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [On line] Available at: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/74b27c3c-0289-11e9-adde01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

- GBC, Government of British Columbia (2023). Mount Polley Mine Tailings Dam Breach Government of British Columbia Victoria, BC, Canada. [Online] Available at: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/air-land-water/spills-environmental-emergencies/spill-incidents/past-spill-incidents/mt-polley (accessed 04/01/2024).

- Gholami, A., Tokac, B., and Zhang, Q. (2024). Knowledge synthesis on the mine life cycle and the mining value chain to address climate change, Resources Policy, 95, 2024, 105183, ISSN 0301-4207. [CrossRef]

- Gibb, H., and O’Leary, K.G. (2014). Mercury exposure and health impacts among individuals in the artisanal and small-scale gold mining community: a comprehensive review. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 667 – 672. [CrossRef]

- Government of South Australia (2011). Environmental impact statement: Olympic dam expansion. ISBN 978-0-7590-0175-6; [Online] Available at: https://plan.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/638242/Olympic_Dam_Expansion_Assessment_Report.pdf (Accessed 22 January 2025).

- Greenfield, N. (2022). Lithium Mining Is Leaving Chile’s Indigenous Communities High and Dry (Literally). NRDC Report. [Online] Available at: https://www.nrdc.org/stories/lithium-mining-leaving-chiles-indigenous-communities-high-and-dry-literally. Accessed 04/01/2025.

- GRI, Global Reporting Initiative (2023). Sector Standard Project for Mining. [On line] Available at: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/standards-development/sector-standard-project-for-mining. Accessed 5 October 2023.

- GTR, Global Tailings Review (2023). About us. [Online] Available at: https://globaltailingsreview.org/about. Accessed 5 October 2023.

- Gupta, C.K., and Krishnamurthy, N. (2005) Extractive Metallurgy of Rare Earths CRC Press Boca Raton, FL, USA.

- GYA (2024). How can underground mining minimise environmental impacts? [Online] Available at: https://hetherington.net.au/underground-mining-minimise-environmental-impacts/ (Accessed 22 January 2025).

- Handayanto, E., Muddarisna, N., and Krisnayanti, B. D. (2014). Induced phytoextraction of mercury and gold from cyanidation tailings of small-scale gold mining area of west Lombok, Indonesia. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2014, 8, 1277 – 1284.

- Haque, N., Hughes, A., Lim, S., and Vernon, C. (2014). Rare earth elements: overview of mining, mineralogy, uses, sustainability and environmental impact Resources 3 4 614 635. [CrossRef]

- Hartono, D. M., Suganda, E., and Nurdin, M. (2017). Metal Distribution at River Water of Mining and Nickel Industrial Area in Pomalaa Southeast Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. Oriental Journal of Chemistry 33(5): 2599–2607. [CrossRef]

- Hayes-Labruto, L., Schillebeeckx, S.J.D., Workman, M., and Shah, N. (2013). Contrasting perspectives on China’s rare earths policies: Reframing the debate through a stakeholder lens. Energy Policy, 63, 2013, pp. 55-68, ISSN 0301-4215. [CrossRef]

- Heaton, C., and Burns, C. (2014). An evaluation of environmental impact assessment in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2014, 32, 246–251.

- ICMI, International Cyanide Management Institute (2021). The International Cyanide Management Code. [Online] Available at: https://cyanidecode.org.

- ICMM (2025). Our principles. https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/our-principles (accessed 28 January 2025).

- ICMM, International Council on Mining and Metals (2021a). Tailings Management: Good Practice Guide. London. [Online] Available at: https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/guidance/innovation/2021/tailings-management-good-practice.

- ICMM, International Council on Mining and Metals (2021b). Conformance Protocols. Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management. London. [Online] Available at: https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/our-principles/tailings/tailingsconformance-protocols.

- ICMM, International Council on Mining and Metals (2022). Tailings Reduction Roadmap. London. [Online] Available at: https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/guidance/innovation/2022/tailings-reduction-roadmap.

- ICMM, International Council on Mining and Metals (2023b). Human Rights Due Diligence Guidance. London. https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/social-performance/2023/guidance_human-rightsdue-diligence.pdf.

- IDB (2025). Aurus Ventures III Fund. Innovation around the Copper and Mining Industries. [Online] Available at: https://www.iadb.org/en/project/CH-M1059 (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- IEA (2023). Final List of Critical Minerals, 2022. IEA, Paris, France. [Online] Available at: https://www.iea.org/policies/15271-final-list-of-critical-minerals-2022 (accessed 15/01/2024).

- IEA (International Energy Agency) (2022). The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions IEA Paris, France.

- IFC, International Finance Corporation (2007a). Environmental, Health, and Safety General Guidelines. Washington, D.C. 99. [Online] Available at: https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2023/ifc-general-ehs-guidelines.pdf.

- IFC, International Finance Corporation (2007b). Environmental, Health, and Safety Guidelines for Waste Management Facilities. Washington, D.C. 36. [Online] Available at: https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2000/2007- waste-management-facilities-ehs-guidelines-en.pdf.

- IGF (2024). Decarbonization of the mining sector: Scoping study on the role of mining in nationally determined contributions. Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development. [Online] Available at: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2024-08/igf-decarbonization-mining-sector.pdf (Accessed 22 January 2025).

- IIED, International Institute for Environment and Development (2002a). Human Rights in the Minerals Industry. London: Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development Project. [Online] Available at: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/G00531.pdf.

- Insights (2020). Queensland Government passes legislation introducing industrial manslaughter offence into resources industry. [Online] Available at: https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2020/05/queensland-government-passes-legislation-introducing-industrial-manslaughter-offence-into-resources-industry Accessed 23 January 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization (2015). ISO 14001:2015 – Environmental management systems. Geneva. [Online] Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/60857.html.

- Irawati, I. (2020). The Expansion of Nickel Mining, Environmental Damage and Determinants’ of the Bajo Community Marginalization in Pomalaa Regency, Southeast Sulawesi. J. Pemikiran Sosiologi 7(2), 139–152. [CrossRef]

- IRMA, Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (2023a). DRAFT Standard for Responsible Mining and Mineral Processing 2.0. Seattle. [Online] Available at: https://responsiblemining.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IRMA-Standard-forResponsible-Mining-and-Mineral-Processing-2.0-DRAFT-20231026.pdf.

- IRMA, Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (2023b). DRAFT Chain of Custody Standard for Responsibly Mined Materials 2.0. Seattle. [Online] Available at: https://responsiblemining.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IRMA-Chain-ofCustody-Standard-Draftv2.0_23October2023.pdf.

- Islam, M., Pranto, A., Shabab, R., Rone, R.I., Al Miraj, A., Hossen, Md M., and Shoumi, S. (2024). Revitalizing the Land: Ecosystem Restoration in PostMining Areas. North American Academic Research. 2024, 7(11), 26- 57. [CrossRef]

- Jasim, A.Q., and Ajjam, S.K. (2024). Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater using ion exchange resin in a batch process with kinetic isotherm. South African Journal of Chemical Engineering, 49, 2024, 43-54, ISSN 1026-9185. [CrossRef]

- Ji, B., Li, Q., and Zhang, W. (2022). Leaching recovery of rare earth elements from calcination product of a coal coarse refuse using organic acids Journal of Rare Earths 40 2 318 327. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y., Zhang, C., Su, P., Tang, Y., Huang, Z., and Tao Ma, T. (2023) A review of acid mine drainage: Formation mechanism, treatment technology, typical engineering cases and resource utilization. Process Safety Environ Prot 170:1240–1260. [CrossRef]

- Johannesson, K.H., Palmore, C.D., Fackrell, J., Prouty, N.G., Swarzenski, P.W., Chevis, D.A., Telfeyan, K., White, C.D., and Burdige, D.J. (2017). Rare earth element behavior during groundwater–seawater mixing along the Kona Coast of Hawaii. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 198, 229–258.

- Johnson, D.B., and Hallberg, K.B. (2005). Acid mine drainage remediation options: a review Science of the Total Environment 338(1–2), 3-14.

- Joyce, S., and Kemp, D. (2020). Social performance and safe tailings management: A critical connection. In Towards Zero Harm: A Compendium of Papers Prepared for the Global Tailings Review. Oberle, B., Brereton, D. and Mihaylova, A. (eds.). St. Gallen: Global Tailings Review. [Online] Available at: https://globaltailingsreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Ch-III-Social-Performance-and-SafeTailings-Management_A-Critical-Connection.pdf.

- Kagambeg, N., Sawadogo, S., Bamba, O., Zombre, P., and Galvez R. (2014). Acid mine drainage and heavy metals contamination of surface water and soil in southwest Burkina Faso–west Africa, International Journal of Multidisciplinary Academic Research 2014; 2 (3):9-19. [Online] Available at: www.multidisciplinaryjournals.com.

- Khosravi, F., Jha-Thakur, U., and Fischer, B. (20190. Evaluation of the environmental impact assessment system in Iran. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 74, 63–72.

- Kilborn Inc. Review of passive systems for treatment of acid mine drainage, Phase II May 1996, Mend report 3.14.1 revised in 1999 and prepared for the Mine Environment Neutral Drainage (MEND) program; Toronto, 1999, pp. 1-79. [Online] Available at: http://mendnedem.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/3.14.1.pdf.

- Kinnunen, P., Obenaus-Emler, R., Raatikainen, J., Guignot, S., Guimerà, J., Ciroth, A., and Heiskanen, K. (2021). Review of closed water loops with ore sorting and tailings valorisation for a more sustainable mining industry, Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 2021, 123237, ISSN 0959-6526. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, A., Lohunova, O., Winkelmann-Oei, G., Mádai, F. and Török, Z. (2020). Safety of Tailings Management Facilities in the Danube River Basin. Technical Report No. 185/2020. Dessau-Rosslau: German Environment Agency. https://unece.org/info/Environment-Policy/Industrialaccidents/pub/369164.

- Kríbek, B., and Nyambe, I. (Eds.) (2005). Impact Assessment of Mining and Processing of Copper and Cobalt Ores on the Environment in the Copperbelt, Zambia. Nsato, Mokambo and Kitwe Areas. Project of the Technical Aid of the Czech Republic to the Republic of Zambia in the Year 2004; Record Office—File Report No. 1/2005; Czech Geological Survey: Prague, Czech Republic, 2005; p. 160, Unpublished Work, Available on Request.

- Kríbek, B., and Nyambe, I. (Eds.) (2007). Impact Assessment of Mining and Processing of Copper and Cobalt Ores on the Environment in the Copperbelt, Zambia. Eastern Part of the Kitwe and Mufulira Areas. Project of the Technical Aid of the Czech Republic to the Republic of Zambia in the Year 2006; Czech Geological Survey: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007; p. 135, Unpublished Work, Available on Request.

- Kríbek, B., and Nyambe, I. (Eds.) (2009). Assessment of Impacts of Mining and Mineral Processing on the Environment and Human Health in Selected Regions of the Central and Copperbelt Provinces of Zambia, Republic of Zambia. The Ndola Area. Project of the Development Cooperation Programme of the Czech Republic to the Republic of Zambia. Final report for the year 2009—The Ndola Area; MS Czech Geological Survey: Prague, Czech Republic, 2010; p. 157, Unpublished Work, Available on Request.

- Kríbek, B., Majer, V., Veselovský, F., and Nyambe, I. (2010). Discrimination of lithogenic and anthropogenic sources of metals and sulphur in soils of the central-northern part of the Zambian Copperbelt Mining District: A topsoil vs. subsurface soil concept. J. Geochem. Explor. 2010, 104, 69–86.

- Kríbek, B., Nyambe, I., Sracek, O., Mihaljevic, M., and Knésl, I. (2023). Impact of Mining and Ore Processing on Soil, Drainage and Vegetation in the Zambian Copperbelt Mining Districts: A Review. Minerals 2023, 13, 384. [CrossRef]

- Kumba Iron Ore Limited (2017). Sustainability Report 2017. [Online] Available at: https://www.angloamericankumba.com/~/media/Files/A/Anglo-American-Kumba/annual-report-2018/section-wise/water.pdf (Accessed 21 January, 2025).

- Lanxess (2025). Ion exchange resins for the mining and metallurgy industry. [Online] Available at: https://lanxess.com/en/products-and-brands/brands/lewatit/industries/mining-and-metallurgy (Accessed 12 January 2025).

- Legge, G.H.H. (1982). Manual on tailings dams and dumps. International Commission on Large Dams. Bulletin 45. Paris.

- Levay, G., Smart, R.S.C., and Skinner, W.M. (2001). The impact of water quality on flotation performance. The Journal of The South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. The South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 2001. SA ISSN 0038–223X/3.00 + 0.00. Paper first published at, Minerals Processing Conference, Aug. 2000. 69-75.

- Lindberg, S., and Anderson, U. (2025). Blood Batteries, So High is the Price for the Technology of the Future. [online] Available at: https://special.aftonbladet.se/blodsbatterier/ (accessed on 05 January 2025).

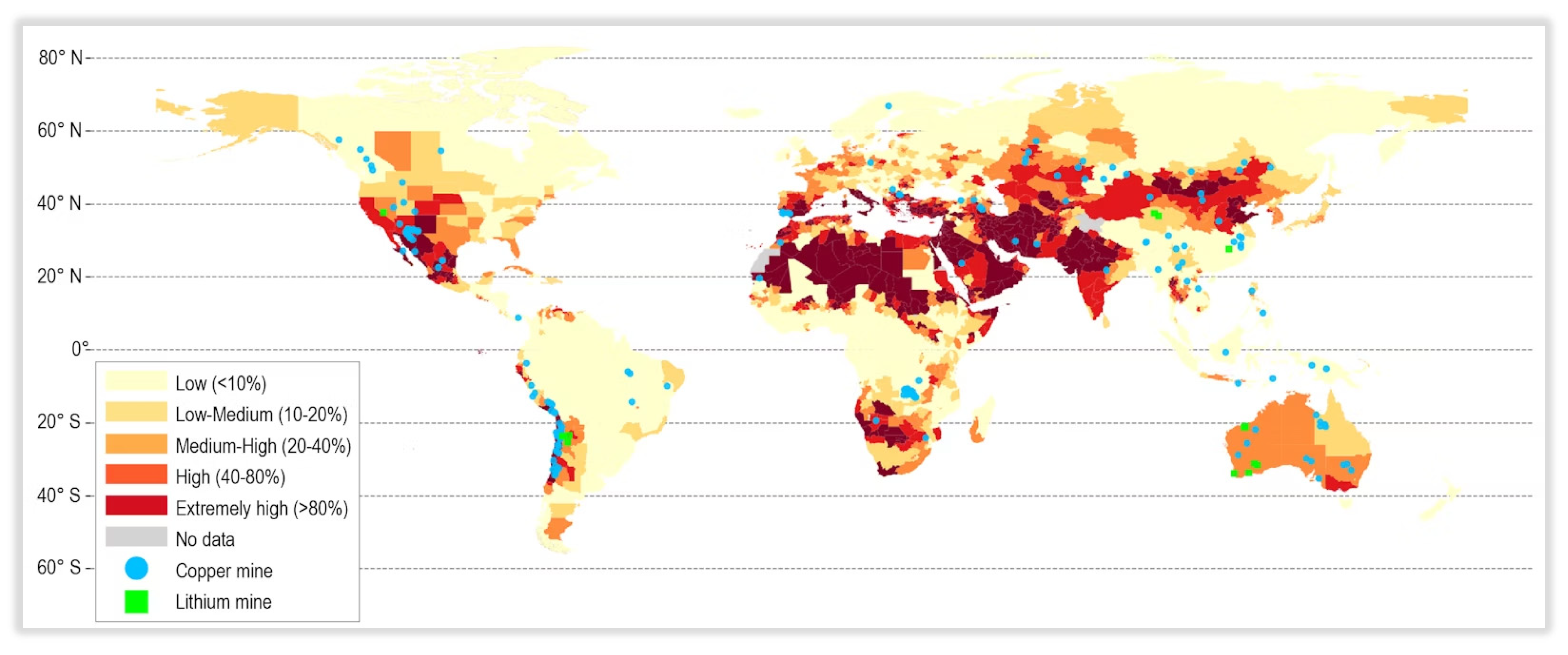

- Liu, W., Agusdinata, D., and Myint, S.W. (2019). Spatiotemporal patterns of lithium mining and environmental degradation in the Atacama Salt Flat, Chile. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 80, 145-156. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., and Agusdinata, D.B. (2020). Interdependencies of lithium mining and communities sustainability in Salar de Atacama, Chile. Journal of Cleaner Production, (), 120838–. [CrossRef]

- Lorch, D. (2024). Team Ghana helps Newmont Mining analyze biodiversity offset solutions. [Online] Available at: https://businessonthefrontlines.nd.edu/discover/insights-from-the-frontlines/team-ghana-helps-newmont-mining-analyze-biodiversity-offset-solutions ((Accessed 24 January 2025).

- Lorion R. (2001). Constructed wetlands: Passive systems for wastewater treatment, Technology status report prepared for the US EPA Technology Innovation Office under a National Network of Environmental Management Studies Fellowship, 2001, pp. 1-24.

- Lukacs, H., and Ortolano, L. (2015). West Virginia has not directed sufcient resources to treat acid mine drainage efectively. Extr Ind Soc 2:194–197. [CrossRef]

- Lutandula, M.S., and Mpanga, F.I. (2021). Review of Wastewater Treatment Technologies in View their Application in the DR Congo Mining Industry. Glob. Environ. Eng. 2021; 8: 14-26. [CrossRef]

- Lutandula, M.S., and Mpanga, F.I. (2021).Review of Wastewater Treatment Technologies in View of their Application in the DR Congo Mining Industry. The Global Environmental Engineers, 2021, 14-26. [CrossRef]

- Lutandula, M.S., and Mwana, K.N. (2014). Perturbations from the recycled water chemical components on flotation of oxidized ores of copper: the case of bicarbonate ions. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2, 190e198. [CrossRef]

- Malek, S.A., and Mohamed, A.M.O. (2005) Environmental impact assessment of offshore oil spill on desalination plant, Desalination Journal, 185, 1435-1456.

- Marazuela, M.A., Vázquez-Suñé, E., Ayora, C., García-Gil, A., and Palma, T. (2019). The effect of brine pumping on the natural hydrodynamics of the Salar de Atacama: the damping capacity of salt flats. Sci. Total Environ. 654, 1118–1131. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A., Balcázar, R.M., and Barandiarán, J. (2022). Exhausted: How We Can Stop Lithium Mining from Depleting Water Resources, Draining Wetlands, and Harming Communities in South America, NRDC Report. [Online] Available at: https://www.nrdc.org/resources/exhausted-how-we-can-stop-lithium-mining-depleting-water-resources-draining-wetlands-and (accessed 04/01/2025).

- Mayangsari, M., Nastiti, A., Marselina, M., Astriani, N., and Wibisana, A.G. (2024). Assessing compliance with environmental regulations: a case study of fines imposed on companies in the Citarum River Basin, Indonesia. E3S Web of Conferences 485, 03002 (2024). [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, B. (2022). Mining industry standard failing to make waste dams safe. Earthworks. 31 May. https://earthworks.org/releases/mining-industry-standard-failing-to-make-waste-dams-safe.

- Mebratu-Tsegaye, T., Toledano, P., Brauch, M.D. and Greenberg, M. (2021). Five Years After the Adoption of the Paris Agreement, Are Climate Change Considerations Reflected in Mining Contracts? New York: Columbia Center on Sustainable Development. [Online] Available at: https://ccsi.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/docs/ccsi-climate-change-investor-state-miningcontracts.pdf.

- Mining Association of Canada (2023). Towards Sustainable Mining - Canada Tailings Management Protocol. [Online] Available at: https://canadacommons.ca/artifacts/11768333/towards-sustainable-mining-canada-tailings-management-protocol-version-date/12659730/ (Accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Mining Association of Canada (2025). Newmont’s all-electric Borden mine. [Online] Available at: https://mining.ca/resources/canadian-mining-stories/newmonts-all-electric-borden-mine/ (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- Mining.com (2022) Vale, other large companies leading reforestation program in Brazil. [Online] Available at: https://www.mining.com/vale-other-large-companies-leading-reforestation-program-in-brazil/(accessed 25 January 2025).

- Minsus.net (2020). Recommendations to Improve Local Governance through Mining Certifications. [Online] Available at: https://minsus.net/mineria-sustentable/documents/recommendations-to-improve-local-governance-through-mining-certifications.pdf (accessed 28 January 2025).

- MMSD (2025). Local communities and mines: chapter 9. The mining, minerals and sustainable development project. 198-229. [Online] Available at: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/G00901.pdf (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- Mohamed, A.M.O. (2024a) “Sustainable recovery of silver nanoparticles from electronic waste: Applications and safety concerns. Review Article. Academia Engineering, 1(3), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.O. (2024b) Nexuses of critical minerals recovery from e-waste. Academia Environmental Sciences and Sustainability 2024;1,1-21. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.O., and Antia, H. (1998) Geo-environmental Engineering, Elsevier, Amsterdam, ISBN: 0-444-89847-6, 707p.

- Mohamed, A.M.O., El Gamal, M.M., and Hameedi, S. (2022) Sustainable utilization of carbon dioxide in waste management: moving toward reducing environmental impact. Elsevier; ISBN 9780128234181, 606p.https://www.elsevier.com/books/sustainable-utilization-of-carbon-dioxide-in-waste-management/mohamed/978-0-12-823418-1.

- Mohamed, A.M.O., Paleologos, E.K. (2018) Fundamentals of Geo-environmental Engineering: Understanding Soil, Water, and Pollutant Interaction and Transport. Elsevier, USA, imprint: Butterworth- Heinemann, ISBN: 9780128048306; 708p.

- Molina Camacho, F. (2016). Intergenerational dynamics and local development: mining and the indigenous community in Chiu Chiu, El Loa Province, northern Chile. Geoforum 75, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Morrill, J., Chambers, D., Emerman, S., Harkinson, R., Kneen, J., Lapointe, U. et al. (2022). Safety First: Guidelines for Responsible Mine Tailings Management. Washington, D.C., Ottawa and London: Earthworks, MiningWatch Canada and London Mining Network. [Online] Available at: https://earthworks.org/wpcontent/uploads/2022/05/Safety-First-Safe-Tailings-Management-V2.0-final.pdf.

- Muddarisna, N., Krisnayanti, B.D., Utami, S.R., and Handayanto, E. (2013). Phytoremediation of mercury-contaminated soil using three wild plant species and its effect on maize growth. Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences. 2013; 1(3):27-32. [CrossRef]

- Muimba-Kankolongo, A., Nkulu, C.B.L., Mwitwa, J., Kampemba, F.M., Nabuyanda, M.M., Haufroid, V., Smolders, E., and Nemery, B. (2021). Contamination of water and food crops by trace elements in the African Copperbelt: A collaborative cross-border study in Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Environ. Adv. 2021, 6, 100103.

- Mulenga, C. Soil governance and the control of mining pollution in Zambia. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 100039. [CrossRef]

- Muma, D., Besa, B., Manchisi, J., and Banda, W. (2020). Effects of mining operations on air and water quality in Mufulira district of Zambia: A case study of Kankoyo Township. J. Sout. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2020, 120, 287–298.

- Murillo Costa, A., Fernando Zanoelo, E., Benincá, C., and Bentes Freire, F. (2021). A kinetic model for electrocoagulation and its application for the electrochemical removal of phosphate ions from brewery wastewater. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 243, 116755.

- Mustafa, M., Maulana, A., Irfan, U. R., and Tonggiroh, A. (2022). Evaluasi Kesuburan Tanah pada Lahan Pasca Tambang Nikel Laterit Sulawesi Tenggara. Jurnal Ilmu Alam dan Lingkungan 13(1): 52–56. [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, O., and Hameed, R. (2008). Evaluation of environmental impact assessment system in Pakistan. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2008, 28, 562–571.

- Nasution, M.J., Tugiyono, Bakri, S., Setiawan, A., Murhadi, Wulandari, C., and Wahono, E.P. (2024). The Impact of Increasing Nickel Production on Forest and Environment in Indonesia: A Review. Journal Sylva Lestari 12(3): 549-576. [CrossRef]

- Ncube, E., Banda, C., and Mundike, J. (2012). Air Pollution on the Copperbelt Province of Zambia: Effects of Sulphur Dioxide on Vegetation and Humans. Nat Env Sci 2012, 3(1), 34-41, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253650701.

- Négrel, P., Guerrot, C., Cocherie, A., Azaroual, M., Brach, M., and Fouillac, C. (2000). Rare earth elements, neodymium and strontium isotopic systematics in mineral waters: Evidence from the Massif Central, France. Appl. Geochem. 2000, 15, 1345–1367.

- Newmont (2022). Ahafo Operations Ghana Technical Report Summary. [Online] Available at: https://minedocs.com/23/Ahafo_TRS_12312021.pdf (Accessed 21 January 2025).

- Newmont (2023). Newmont’s Mining lifecycle: Sustainable value and community engagement. [Online] Available at: https://www.newmont.com/blog-stories/blog-stories-details/2023/Newmonts-Mining-Lifecycle-Sustainable-Value-and-Community-Engagement/default.aspx (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- Nguyen, H.T.H., Nguyen, B.Q., Duong, T.T., Bui, A.T.K., Nguyen, H.T.A., Cao, H.T., Mai, N.T., Nguyen, K.M., Pham, T.T., and Kim, K.-W. (2019). Pilot-Scale Removal of Arsenic and Heavy Metals from Mining Wastewater using Adsorption Combined with Constructed Wetland. Minerals 2019, 9, 379. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, M.R. (2020). 5 Ways to Make Mining More Sustainable. [Online] Available at: https://empoweringpumps.com/5-ways-to-make-mining-more-sustainable/ (Accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Nkulu, C.B.L., Casas, L., Haufroid, V., De Putter, T., Saenen, N.D., Kayembe-Kitenge, T., Obadia, P.M., Wa Mukoma, D.K., Ilunga, J.-M.L., Nawrot, T.; Luboya Numbi, O., Smolders, E., and Nemery B. (2018). Sustainability of artisanal mining of cobalt in DR Congo. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1(9), 495–504. [CrossRef]

- Oberle, B., Brereton, D. and Mihaylova, A. (eds.) (2020). Towards Zero Harm: A Compendium of Papers Prepared for the Global Tailings Review. St. Gallen: Global Tailings Review. https://globaltailingsreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GTR-TZH-compendium.pdf.

- OECD (2022), Regulatory Governance in the Mining Sector in Brazil, OECD Publishing, Paris. [Online] Available at; Accessed 22 January 2025. [CrossRef]

- Oelofse, S. (2008). Mine water pollution - Acid mine decant, Effluent and treatment: A consideration of key emerging issues that may impact the state of the environment, Emerging Issues Paper: Mine Water Pollution 2008, A document prepared for The South African Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT), 2008, pp. 1-11.

- Opitz, J., Alte, M., Bauer, M., and Peifer, S. (2021). The Role of Macrophytes in Constructed Surface-fow Wetlands for Mine Water Treatment: A Review, Mine Water and the Environment, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Otunola, B.O., and Mhangara, P. (2024). Global advancements in the management and treatment of acid mine drainage. Appl Water Sci 14, 204 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Oyewumi Tolulope, O., and Ajayi Omoyemi, O. (2020). Biological Treatment of Heavy Metal in Aquatic Environment: A Review of Wetland Phytoremediation and Plant-Based Biosorption Methods, International Journal of Current Research in Applied Chemistry & Chemical Engineering 2020; 4(1): 46-52.

- Paddock, R.C. (2016). The Toxic Toll of Indonesia’s Gold Mines, National Geographic. [Online] Available at: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/05/160524-indonesia-toxic-toll/.

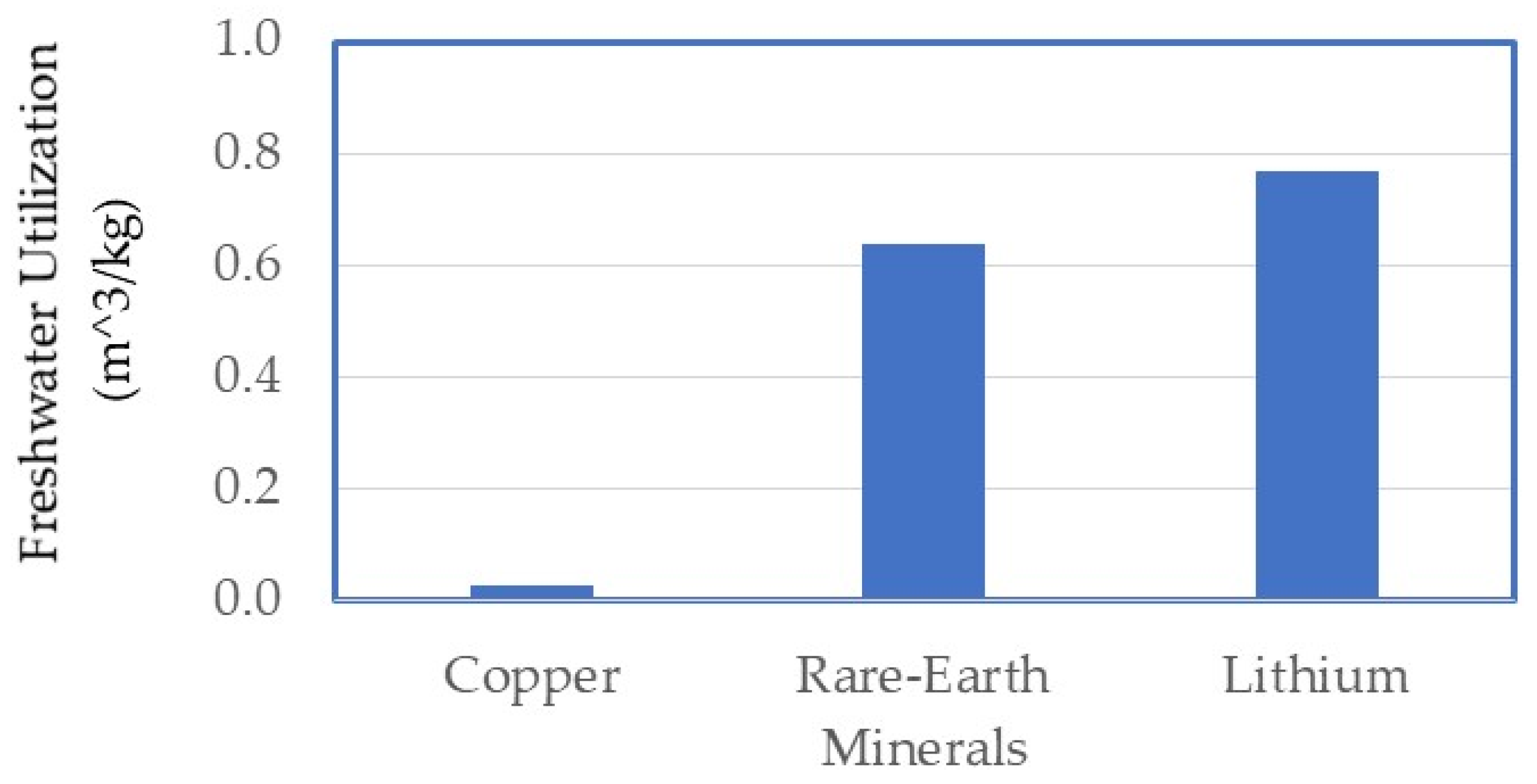

- Paleologos, E.K., Mohamed, A.M.O., Singh, D.N., O’Kelly, B.C., El Gamal, M., Mohammad, A., Singh, P., Goli, V.S.N.S., Roque, A.J., Oke, J.A., Abuel-Naga, H., and Leong, E-C. (2024) Sustainability Challenges of Critical Minerals for Clean Energy Technologies: Copper and Rare Earths. Environmental Geotechnics J. [CrossRef]

- Palmerton, D. (2023). The science, funding, and treatment of acid mine drainage: nationwide, states are developing acid mine reclamation projects in pennsylvania, west virginia, illinois, and wyoming, among others. Coal Age 128:16–21.

- Park, J.D., and Zheng, W. (2012). Human exposure and health effects of inorganic and elemental mercury. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012 Nov;45(6):344-52. [CrossRef]

- Pat-Espadas, A.M., Portales, R.L., Amabilis-Sosa, L.E., Gómez, G., and Vidal, G. (2018). Review of Constructed Wetlands for Acid Mine Drainage Treatment, Water 2018; 10 (1685): 2-25. [CrossRef]

- Patra, M., and Sharma, A. (2000). Mercury toxicity in plants. Bot. Rev 66, 379–422 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Pervov, A., Aung, H.Z., and Spitsov, D. (2023). Treatment of Mine Water with Reverse Osmosis and Concentrate Processing to Recover Copper and Deposit Calcium Carbonate. Membranes 2023, 13, 153. [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, U.T., Ingri, J., and Andersson, P.S. (2006). Hydrogeochemical processes in the Kafue River upstream from the Copperbelt Mining Area, Zambia. Aquat. Geochem. 2000, 6, 385–411.

- Poelzer, G., Frimpong, R., Poelzer, G., and Bram Noble, B. (2023). Community as Governor: Exploring the role of Community between Industry and Government in SLO. Environmental Management 72, 70–83 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Potvin, R. (2004). Réduction de la toxicité des effluents des mines de métaux de base et précieux à l’aide de méthodes de traitement biologique, Rapport de synthèse environnementale, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscaminque, Inédit, 2004, pp.7-20.

- Pourret, O., Lange, B., Bonhoure, J., Colinet, G., Decrée, S., Mahy, G., Séleck, M., Shutcha, M., and Faucon, M.-P. (2016). Assessment of soil metal distribution and environmental impact of mining in Katanga (Democratic Republic of Congo). Appl. Geochem. 2016, 64, 43–55.

- Prematuri, R., Turjaman, M., Sato, T., and Tawaraya, K. (2020). The Impact of Nickel Mining on Soil Properties and Growth of Two Fast-Growing Tropical Trees Species. International Journal of Forestry Research 2020: 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Prestipino, D. (2024). BHP’s $22million First Nations social investment aims to drive change. [Online] Available at: https://nit.com.au/27-11- 2024/15078/bhps-20m-to-social-investment-keeps-fn-dream-alive#:~:text=The%20results%20position%20BHP%20on,Centre%20for%20Indigenous%20Business%20Leadership (Accessed 25 January 2025).

- Queensland Government (2024). South west Qld mine operator fined for failing to manage onsite contaminated water. [Online] Available at: https://www.desi.qld.gov.au/our-department/news-media/mediareleases/2024/south-west-qld-mine-operator-fined-failing-manage-onsite-contaminated-water (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- RAID and AFREWATCH (2024). Beneath the Green: A critical look at the environmental and human costs of industrial cobalt mining in DRC. [Online] Available at: https://raid-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Report-Beneath-the-Green-DRC-Pollution-March-2024.pdf (accessed 04/01/2025).

- Rao, S.R., and Finch, J.A. (1989). Review of water re-use in flotation, Minerals Engineering 1989; 2: 65-85.

- Reichelt-Brushett, A.J., Stone, J., Howe, P., Thomas, B., Clark, M., Male, Y., Nanlohy, A., and Butcher, P. (2017). Geochemistry and mercury contamination in receiving environments of artisanal mining wastes and identified concerns for food safety. Environ Res. 2017 Jan;152:407-418. [CrossRef]

- Rio Tinto (2023). Rio Tinto to invest in Pilbara desalination plant. [Online] Available at: https://www.riotinto.com/en/news/releases/2023/rio-tinto-to-invest-in-pilbara-desalination-plant (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- Rio Tinto (2025). Oyu Tolgoi shareholders sign agreement to progress the development of underground mine. [Online] Available at: https://www.riotinto.com/mn-mn/mn/news/releases/oyu-tolgoi-shareholders-agreement-signed (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- RJC, Responsible Jewellery Council (2019). Code of Practices. Standard. London. 58. [Online] Available at: https://www.responsiblejewellery.com/wp-content/uploads/RJC-COP-2019-V1.2-Standards-updated130623.pdf.

- Roche, C., Thygesen, K., and Baker, E. (eds). (2017). Mine Tailings Storage: Safety Is No Accident. A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment. Nairobi and Arendal: United Nations Environment Programme and GRIDArendal. [Online] Available at: https://www.grida.no/publications/383.

- Rodgers, J.H., and Castle, J.W. (2008). Constructed wetland systems for efficient and effective treatment of contaminated waters for reuse, Environmental Geosciences 2008; 15(1): 1-8.

- Rodríguez-Luna, D., Encina-Montoya, F., Alcalá, F.J., and Vela, N. (2022). An Overview of the Environmental Impact Assessment of Mining Projects in Chile. Land 2022, 11, 2278. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Luna, D., Vela, N., Alcalá, F.J., and Encina-Montoya, F. (2021). The Environmental Impact Assessment in Aquaculture Projects in Chile: A Retrospective and Prospective Review Considering Cultural Aspects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9006.

- Romero, H., Méndez, M., and Smith, P. (2012). Mining development and environmental injustice in the Atacama Desert of Northern Chile. Environ. Justice 5 (2), 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J., Carissimi, E., and Rosa, J. (2007). Flotation in water and waste-water treatment and reuse: recent trends in Brazil, International Journal of Environment and Pollution 2007; 30: 193-207.

- Sanderson, H., and Hume, N. (2019). Financial Times. Dozens Die on Congo Mine Accident. 2019. [Online] Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/aea51eb0-98c7-11e9-8cfb-30c211dcd229 (accessed on 05 January 2025).

- Schelesinger, M., and Paunovic, M. (2006). Fundamentals of Electrochemical Deposition, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Windsor, ON, Canada, 2006.

- Scheuhammer, A., Braune, B., Chan, H.M., Frouin, H., Krey, A., Letcher, R., Loseto, L., Noël, M., Ostertag, S., Ross, P., and Wayland, M.(2015). Recent progress on our understanding of the biological effects of mercury in fish and wildlife in the Canadian Arctic, Science of The Total Environment, Volumes 509–510, 2015, 91-103, ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Scheyder, E. (2024). Arizona’s battle over crucial copper mine poised to sway US election. [Online] Available at: https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/arizonas-battle-over-crucial-copper-mine-poised-sway-us-election-2024-09-12/ (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- Seccatore, J., Veiga, M., Origliasso, C., Marin, T., and De Tomi, G. (2014). An estimation of the artisanal small-scale production of gold in the world. Sci Total Environ. 2014 Oct 15;496, 662-667. [CrossRef]

- Shengo, L.M., and Mutiti, W.N.C. (2016). Bio-treatment and water reuse as feasible treatment approaches for improving wastewater management during flotation of copper ores, International Journal of Environmental Sciences and Technology 2016; 13: 2505–2520.

- Shrestha, K.L. (2008). Decentralised wastewater management using constructed wetland in Nepal, Water aid in Nepal, Kupondole, 2008, pp.1-12.

- SIBELCO (2013). SIBELCO EA amendments attachment 9. [Online] Available at: https://documents.parliament.qld.gov.au/com/AREC-56F5/RN3154PNSI-A863/que-23Oct2013Att9.pdf); accessed 12 January, 2025.

- Simões, A., Macêdo-Júnior, R., Santos, B., Silva, L., Silva, D., and Ruzene, D. (2020). Produced Water: An overview of treatment technologies, International Journal for Innovation Education and Research 2020; 8(4): 207-224. [CrossRef]

- Skrzypiec, K., and Gajewska, M.H. (2017). The use of constructed wetlands for the treatment of industrial wastewater, Journal of Water and Land Development 2017; 34 (VII–IX): 233–240. [CrossRef]

- Shardendu, S.N., Boulyga, S.F., and Stengel, E. (2003). Phytoremediation of selenium by two helophyte species in subsurface flow constructed wetland, Chemosphere 2003; 50: 967-973.

- Smolders, E., Roels, L., Kuhangana, T.C., Coorevits, K., Vassilieva, E., Nemery, B., and Nkulu, C.B.L. (2019). Unprecedentedly High Dust Ingestion Estimates for the General Population in a Mining District of DR Congo. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7851–7858.

- Sole, K.C., Prinsloo, A., and Hardwick, E. (2016). Recovery of copper from Chilean mine waste waters. Proceedings IMWA 2016, Freiberg/Germany | Drebenstedt, Carsten, Paul, Michael (eds.) | Mining Meets Water – Conflicts and Solutions. 1295- 1302; [Online] Available at: http://www.imwa.de/docs/imwa_2016/IMWA2016_Sole_277.pdf (Accessed 12 January 2025).

- Solis-Marcial, O.J., Talavera-López, A., Ruelas-Leyva, J.P., Hernández-Maldonado, J.A., Najera-Bastida, A., Zarate-Gutierrez, R., and Serrano Rosales, B. (2024). Clarification of Mining Process Water Using Electrocoagulation. Minerals 2024, 14, 412. [CrossRef]

- Souza, I.C., Morozesk, M., Azevedo, V.C., Mendes, V.A.S., Duarte, I.D., Rocha, L.D., Matsumoto, S.T., Elliott, M., Baroni, M.V., Wunderlin, D.A., Monferrán, M.V., and Fernandes, M.N. (2021). Trophic transfer of emerging metallic contaminants in a neotropical mangrove ecosystem food web. Journal of Hazardous Materials 408, 124424. [CrossRef]

- Sracek, O., Kríbek, B., Mihaljevic, M., Majer, V., Veselovský, F., Vencelides, Z., and Nyambe, I. (2012). Mining-related contamination of surface water and sediments of the Kafue River drainage system in the Copperbelt district, Zambia: An example of a high neutralization capacity system. J. Geoch. Explor. 2012, 112, 174–188.

- Sracek, O., Kříbek, B., Mihaljevič, M., Majer, V., Veselovský, F., Vencelides, Z., and Nyambe, I. (2012). Mining-related contamination of surface water and sediments of the Kafue River drainage system in the Copperbelt district, Zambia: An example of a high neutralization capacity system. January 2012. Fuel and Energy Abstracts, 112(3). [CrossRef]

- Steckling, N., Tobollik, M., Plass, D., Hornberg, C., Ericson, B., Fuller, R., and Bose-O’Reilly, S. (2017). Global burden of disease of mercury used in artisanal small-scale gold mining. Ann Glob Health. 2017 Mar-Apr;83(2):234-247. [CrossRef]

- Strady, E., Kim, I., Radakovitch, O., and Kim, G. (2015). Rare earth element distributions and fractionation in plankton from the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 72–82.

- Sudilovskiy, P., Kagramanov, G., and Kolesnikov, V. (2008). Use of RO and NF for treatment of copper containing wastewaters in combination with flotation, Desalination 2008; 221: 192-201.

- Sumi, L., and Thomsen, S. (2001). Mining in Remote Areas: Issues and impacts, Produced for MiningWatch Canada/Mines Alerte by the Environmental Mining Council of British Columbia, Printed by union labour at Fleming Printing, Victoria, BC, 2001, pp. 1-33.

- Swenson, J. J., Carter, C. E., Domec, J.-C., and Delgado, C. I. (2011). Gold Mining in the Peruvian Amazon: Global Prices, Deforestation, and Mercury Imports. PLoS One 2011, 6. [CrossRef]

- Syarifuddin, N. (2022). Pengaruh Industri Pertambangan Nikel terhadap Kondisi Lingkungan Maritim di Kabupaten Morowali. Jurnal Riset dan Teknologi Terapan Kemaritiman 1(2): 19–23. [CrossRef]

- T&E (2024). Mining waste: time for the EU to clean up. [Online] Available at: https://www.transportenvironment.org/articles/mining-waste-time-for-the-eu-to-clean-up. Accessed 22 January, 2025.

- Taşdemir, T., and Başaran, H.K. (2020). Floatability of Suspended Particles from Wastewater of Natural Stone Processing by Floc-Flotation in Mechanical Cell, El-Cezerî Journal of Science and Engineering 2020;7(2): 358-370. [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B., Ayensu, W.K., Ninashvili, N., and Sutton, D. (2003). Environmental exposure to mercury and its toxicopathologic implications for public health. Environ Toxicol. 2003 Jun;18(3),149-175. [CrossRef]

- Teck (2020). 2020 Sustainability report. [Online] Available at: https://ceowatermandate.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2020-sust-water-Teck-Resources.pdf (Accessed 21 January 2025).

- Teck (2023a). Sustainability Report: Relationships with Indigenous Peoples. [Online] Available at: https://www.teck.com/media/Sustainability-Report-Relationships-With-Indigenous-Peoples.pdf (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- Teck (2023b). Sustainability Report Relationships with Communities. [Online] Available at: https://www.teck.com/media/Sustainability-Report-Relationships-With-Communities.pdf (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- The Warren Centre (2020). Zero Emission Copper Mine of the Future. [Online] Available at: https://internationalcopper.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Emissions-Copper-Mine-of-the-Future-Report.pdf (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- Traore, M. (2023). Research progress on the content and distribution of rare earth elements in rivers and lakes in China. Marine Pollution Bulletin 191(2023):114916. [CrossRef]

- Trapasso, G., Chiesa, S., Freitas, R., and Pereira, E.(2021). What do we know about the ecotoxicological implications of the rare earth element gadolinium in aquatic ecosystems? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146273. [PubMed]

- Trifuoggi, M., Donadio, C., Ferrara, L., Stanislao, C., Toscanesi, M., and Arienzo, M. (2018). Levels of pollution of rare earth elements in the surface sediments from the Gulf of Pozzuoli (Campania, Italy). Mar. Poll. Bull. 2018, 136, 374–384.

- UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Indigenous Peoples (2016). Free Prior and Informed Consent – An Indigenous Peoples’ right and a good practice for local communities – FAO. [Online] Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/publications/2016/10/free-prior-and-informed-consent-an-indigenous-peoples-right-and-a-good-practice-for-local-communities-fao/#:~:text=FPIC%20is%20a%20principle%20protected,%2C%20social%20and%20cultural%20development’. (Accessed 24 January 2025).

- UNECE, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2020). Conclusions of the seminar on mine tailings safety in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe region and beyond. Informal document CP.TEIA/2020/INF.6. Geneva. [Online] Available at: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/documents/2020/TEIA/COP_11/Informal_docs/CP.TEIA2020INF.6_Eng.pdf.

- UNECE, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2022a). Conference of the Parties to the UNECE Industrial Accidents Convention, Decision 2022/1 on Strengthening Natech risk management in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe region and beyond (ECE/CP.TEIA/44/Add.1). Geneva. [Online] Available at: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/ECE_CPTEIA_44Add1_E.pdf.

- UNECE. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2022b). Roadmap to Strengthen Mine Tailings Safety Within and Beyond the UNECE Region. Geneva. [Online] Available at: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/ECE_CP.TEIA_2022_7-2214590E%5B1%5D.pdf.

- UNEP (2024) Knowledge Gaps in Relation to the Environmental Aspects of Tailings Management. [Online] Available at: https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/tools/Final%20Knowledge%20Gaps%20Report_Environmental%20Aspects%20of%20Tailings%20Management%20%28January%202024%29_1.pdf (accessed 22 January, 2024).

- UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme (2023a). Environmental aspects of minerals and metals management. Co-chairs’ summary of intergovernmental regional consultation. Group of Eastern European States. 24-25 April 2023. [Online] Available at: https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/tools/EEG-Report-FINAL.pdf.

- UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme (2023b). Environmental aspects of minerals and metals management. Co-chairs’ summary of intergovernmental regional consultation. Group of Western European and Other States. 27-28 April 2023. [Online] Available at: https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/tools/WEOG-Report-FINAL.pdf.

- UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme (2023c). Environmental aspects of minerals and metals management. Co-chairs’ summary of intergovernmental regional consultation. Group of Latin American and Caribbean States. 17-18 May 2023. [Online] Available at: https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/tools/GRULAC-Report.pdf.

- UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme (2023d). Environmental aspects of minerals and metals management. Co-chairs’ summary of intergovernmental regional consultation. Group of Asian and Pacific States. 15-16 June 2023. [Online] Available at: https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/tools/Asian-Pacific-Group-ReportV3.pdf.

- UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme (2023e). Environmental aspects of minerals and metals management. Co-chairs’ summary of intergovernmental regional consultation. African Group of States. 5- 6 July 2023. [Online] Available at: https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/tools/African-GroupReport-V3.pdf.

- UNFCCC (2021). Chile’s long-term climate strategy the path to carbon neutrality and resilience by 2050; [Online] Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/CHL_LTS_2021_EN_0.pdf (Accessed 23 January 20250.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2022). Mineral Resource Governance and the Global Goals: An Agenda for International Collaboration – Summary of the UNEA 4/19 Consultations. Nairobi. [Online] Available at: https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/37968.

- US EPA (2025). Criminal Provisions of Water Pollution. [Online] Available at: https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/criminal-provisions-water-pollution (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- USGS, U.S. Geological Survey. Minerals Yearbook-Rare Earths. [Online] Available at: https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/rare_earths/mcs-2015-raree.pdf (accessed on 05 January 2025).

- Vale (2025). Amazon. [Online] Available at: https://vale.com/amazonia (Accessed 25 January 2025).

- Verónica, R.O.A., González, J., and Torres, J (2017). How to improve collaboration between industry, government and universities to face industry challenges: the case of the Chilean Mining Programme ‘Alta Ley’. Revista, ISSN 0798 1015, [Online] Available at: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n47/a17v38n47p31.pdf (Accessed 23 January 2025).

- Vidal, M.C. (2023). Updated Environmental and Social Impact Assessment on the Construction and operation of the Six Senses Cerro Verde Ecolodge. [Online] Available at: https://d1xeoqaoqyzc9p.cloudfront.net/app/uploads/2023/10/UPDATED-ESIA-and-ESMP_Six-Senses-Cerro-Verde_20231010_EN_compressed.pdf (Accessed 22 January 2025).

- Vigneswaran, S., Ngo, H.H., Chaudhary, D.S., and Hung, Y-T. (2007). Physicochemical treatment processes for water reuse, in Wang, L. K., Hung, Y.-T. & Shammas, N.K. (Eds.)., 2007. Handbook of Environmental Engineering, Volume 3: Physicochemical Treatment Processes, The Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ, 2007, pp. 635-676.

- Vrel, A. (2012). Reconstitution de L’historique des Apports en Radionucléides et Contaminants Métalliques à L’estuaire Fluvial de la Seine Par L’analyse de Leur Enregistrement Sédimentaire. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Caen, Caen, France, 2012.

- Wahanisa, R., and Adiyatma, S. E. (2021). Konsepsi Asas Kelestarian dan Keberlanjutan dalam Perlindungan dan Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup dalam Nilai Pancasila. Bina Hukum Lingkungan 6(1): 95–120. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F., and Reade, G. (1994). Design and performance of electrochemical reactors for efficient synthesis and environment treatment. Part 1.Electrode Geometry and Figures of Merit. Analuyst 1994, 119, 791–796.

- Wang, Z., Xu, Y., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, Y. (2021). Review: Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) in abandoned coal mines of shanxi. China. Water 13:8. [CrossRef]

- Wayakone, S., and Makoto, I. (2012). Evaluation of the environmental impacts assessment (EIA) system in Lao PDR. Environ. Prot. 2012, 3, 1655–1670.

- WGC, World Gold Council (2019). Responsible Gold Mining Principles. [Online] Available at: https://www.gold.org/download/file/14254/Responsible-Gold-Mining-Principles-en.pdf.

- White & Case LLP (2024). Net-zero by 2050: is the mining & metals sector on track to reduce greenhouse gas emissions? [Online] Available at: https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/net-zero-2050-mining-metals-sector-track-reduce-greenhouse-gas-emissions; Accessed 22 January 2025.

- WHO, World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: First Addendum to the Fourth Edition. 2017. [Online] Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549950 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Wolfe, M. F., Schwarzbach, S., and Sulaiman, R. A. (1998). Effects of mercury on wildlife: A comprehensive review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1998, 17, 146 – 160.

- Wolkersdorfer, C., and Mugova, E. (2022). Effects of mining on surface water. Encyclopedia of Inland Waters, Second Edition by Section Editors Ken Irvine, Debbie Chapman and Stuart Warner, 170-187. [CrossRef]

- Wood, C. (1995). Evaluación de Impacto Ambiental un Análisis Comparativo de Ocho Sistemas EIA, Doc de Trabajo N◦ 247; Centro de Estudios Públicos: Santiago, Chile, 1995.

- World Bank (2016). Environmental and social management framework. Zambia Mining Environment Remediation and Improvement Project. [Online] Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/fr/813951469077929423/pdf/SFG2338-EA-P154683-Box396279B-PUBLIC-disclosed-7-20-16.pdf (accessed 06 January 2025).

- Wróbel, M., Sliwakowski, W., Kowalczyk, P., Kramkowski, K., and Dobrzynski, J. (2023). Bioremediation of Heavy Metals by the Genus Bacillus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4964. [CrossRef]

- Yong, R.N., Mohamed, A.M.O, and Warkentin, B.P. (1992) Principles of Contaminant Transport in Soils,” Elsevier, Amsterdam, ISBN: 0-444-882936; 327p.

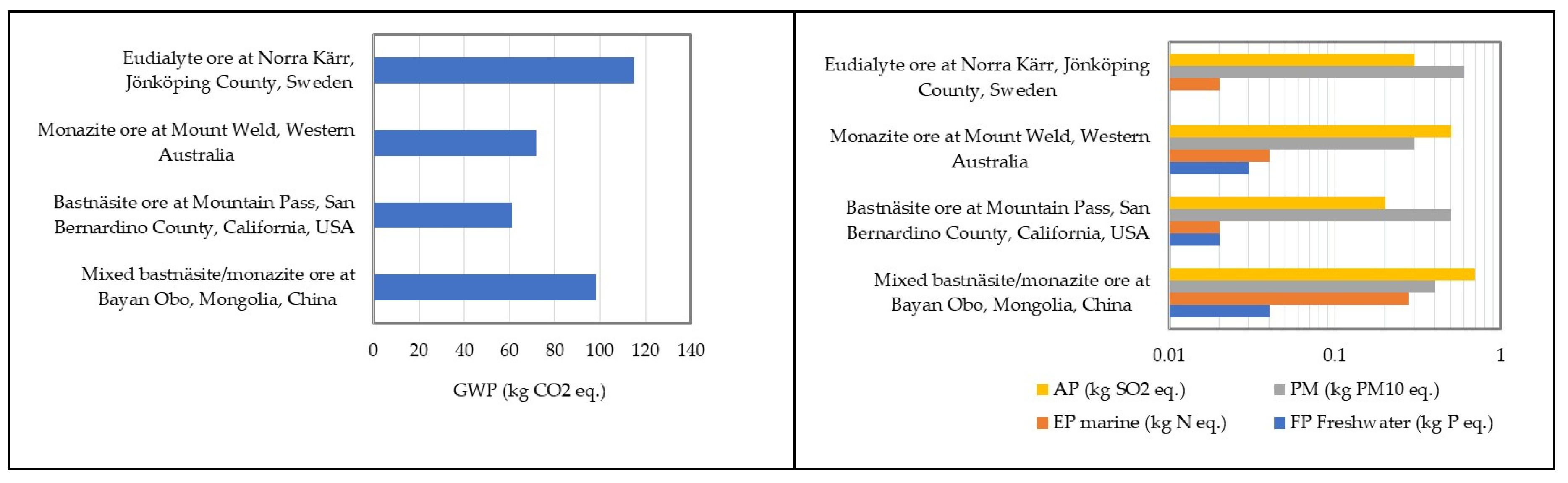

- Zapp, P., Schreiber, A., Marx, J., and Kuckshinrichs, W. (2022). Environmental impacts of rare earth production. MRS bulletin, 47, March 2022, 267-275. [CrossRef]

- Zillioux, E. J., Porcella, D. B., and Benoit, J. M. (1993) Mercury cycling and effects in freshwater wetland ecosystems. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1993, 12, 2245 – 2264. [CrossRef]

| Impact category | Unit | Cobalt (Co) | Copper (Cu) | Nickel (Ni) |

| Climate change | kg CO2 eq. | 10.81 | 5.44 | 11.19 |

| Ozone depletion | kg CFC-11 eq. | 3.68E-07 | 2.68E-07 | 5.12E-07 |

| Human toxicity, non-cancer effects | CTUh | 6.95E-07 | 7.79E-07 | 2.52E-06 |

| Human toxicity, cancer effects | CTUh | 1.45E-08 | 2.54E-08 | 4.51E-08 |

| Particulate matter | kg PM2.5 eq. | 5.3E-03 | 0.024 | 0.095 |

| Acidification | mole H+ eq. | 0.1 | 0.42 | 1.87 |

| Terrestrial eutrophication | mole N eq. | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.38 |

| Freshwater eutrophication | kg P eq. | 3.18E-05 | 0.01 | 0.014 |

| Marine eutrophication | kg N eq. | 0.041 | 0.018 | 0.026 |

| Freshwater ecotoxicity | CTUe | 0.52 | 9.25 | 17.52 |

| Land use | kg C deficit | 24.69 | 4.58 | 6.76 |

| Water resource depletion | m³ water eq. | 0.057 | 0.032 | 0.053 |

| Kafue River | Tributaries of the Kafue River | ||||||

| Mushishima River | Wusakile River | ||||||

| Water | Sediment | Water | Water | Sediment | |||

| Parameter/ Element | Inflow (µg/L) |

Outflow (µg/L) |

Inflow (mg/kg) |

Outflow (mg/kg) | Inflow (µg/L) | Inflow (µg/L) | |

| pH | 6.6 | 6.8 | ND | ND | 2.04 | ||

| SO4 | 1.02 | 79.5 | ND | ND | 1396 mg/L | ||

| Al | 4.5 | 20.5 | ND | ND | 2115 µg/L | ||

| As | < 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.36 | 3.77 | 30.9 mg/kg | ||

| Ba | 15.3 | 37.9 | ND | ND | |||

| Co | < 0.05 | 33.1 | 18 mg/kg | 540 | 919 | 909 µg/L | 1060 mg/kg |

| Cr | ND | ND | 64 | 40 | |||

| Cu | 3.5 | 52.3 | 161 | 1520 | 14,752 | 7405 µg/L | 6316 mg/kg |

| Fe | ND | ND | 2.27 wt.% | 2.01 wt.% | |||

| Hg | ND | ND | 0.026 | 0.11 | |||

| Mn | 12.5 | 158 | 117 | 2251 | |||

| Mo | < 0.1 | 1.18 | ND | ND | |||

| Ni | 0.11 | 0.82 | 27 | 23 | 51.5 µg/L | ||

| P | 33.5 | 62.1 | ND | ND | |||

| Pb | 0.11 | 0.25 | 8.5 | 24.5 | 161 µg/L | 60 mg/kg | |

| Se | 0.05 | 0.91 | ND | ND | |||

| Stot | ND | ND | 0.08 wt.% | 0.13 wt.% | 0.29 wt.% | ||

| Zn | 1.7 | 3.7 | 62.5 | 55.5 | 346 µg/L | 129 mg/kg | |

| Major process contribution in decreasing order | |||||

| Process Chain | GWP (kg CO2 eq.) |

FP Freshwater (kg P eq.) | EP marine (kg N eq.) |

PM (kg PM10 eq.) |

AP (kg SO2 eq.) |

| Mixed bastnäsite/monazite ore at Bayan Obo, Mongolia, China | 9 > 4 > 3 > 8 > 6 | 9 > 4 > 8 | 3 | 1 > 3 | 6 > 8 > 4 > 9 |

| Bastnäsite ore at Mountain Pass, San Bernardino County, California, USA | 4 > 9 > 2 | 9 > 4 | 4 > 9 | 1 > 3 | 1 > 4 > 9 |

| Monazite ore at Mount Weld, Western Australia | 4 > 8 > 6 > 9 | 9 > 8 > 4 | 8 > 4 | 1 > 4 > 2 > 6 | 6 > 4 > 8 > 9 |

| Eudialyte ore at Norra Kärr, Jönköping County, Sweden | 4 > 6 > 8 > 7 | 2 > 9 | 4 > 8 | 1 > 3 | 6 > 4 > 1 > 2 |

| Number identification of processes used: 1 for Mining; 2 for flotation; 3 for ammonium bicarbonate precipitation; 4 for solvent extraction; 5 for magnetic separation; 6 for roasting; 7 for leaching; 8 for precipitation with oxalic acid; and 9 for electrolysis GWP (kg CO2 eq.) for global warming potential; EP freshwater (kg P eq.) for eutrophication potential; EP marine (kg N eq.) for eutrophication potential; PM (kg PM10 eq.) for particulate matter; and AP (kg SO2 eq.) for acidification potential | |||||

| Treatment Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Reverse Osmosis (RO) |

|

|

| Constructed Wetlands |

|

|

| Ion Exchange (IX) |

|

|

| Flotation & Coagulation/Flocculation |

|

|

| Bioremediation |

|

|

| Electrocoagulation |

|

|

| Environmental Aspect | Reduction Measure | Benefit |

| Energy Consumption | Use of renewable energy sources (e.g., solar, wind) | Lower carbon emissions and fuel dependency |

| Water Usage | Implement water recycling and conservation systems | Reduce freshwater consumption and pollution |

| Air Quality | Install dust suppression and emission control systems | Improve local air quality |

| Land Degradation | Rehabilitate land after mining | Restore natural habitats and ecosystems |

| Biodiversity Loss | Design buffer zones and habitat corridors | Protect local flora and fauna |

| Waste Management | Use tailings reprocessing and safe disposal methods | Reduce toxic waste and soil contamination |

| Acid Mine Drainage | Chemical neutralization and natural barriers | Prevent contamination of local water bodies |

| Noise Pollution | Use sound barriers and low-noise equipment | Minimize impact on nearby communities |

| Carbon Emissions | Deploy electric or hybrid vehicles in mining | Decrease the overall carbon footprint |

| Mine Closure Planning | Create detailed closure and reclamation plans | Ensure long-term environmental restoration |

| Regulatory Dimension | Name | Performance Standards Areas |

| Professional associations | The International Commission on Large Dams | safety, design, construction, operation, closure, monitoring and management |