Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

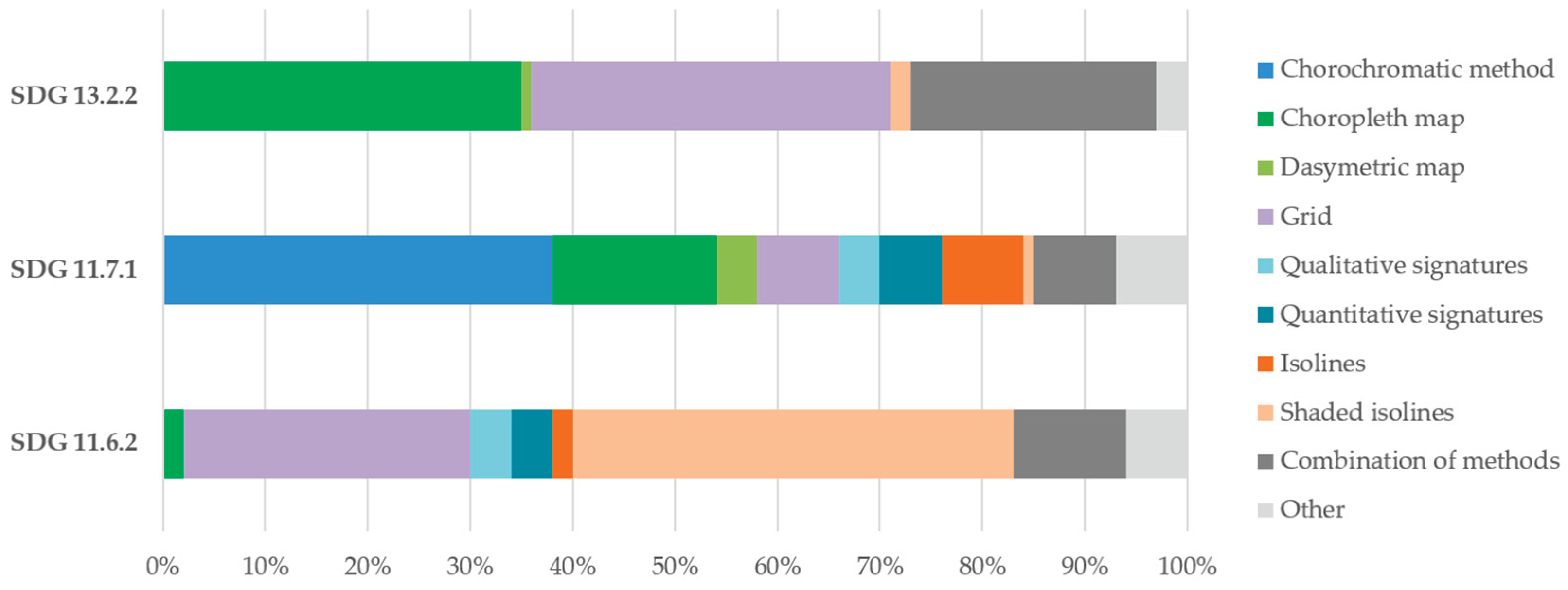

- Target 11.6: Reduce the environmental impacts of cities (Indicator 11.6.2 – Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter);

- Target 11.7: Provide access to safe and inclusive green and public spaces (Indicator 11.7.1 – Average share of the built-up area of cities that is open space for public use for all);

- Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies, and planning (Indicator 13.2.2 – Total greenhouse gas emissions per year).

2. Related Studies

3. Materials and Methods

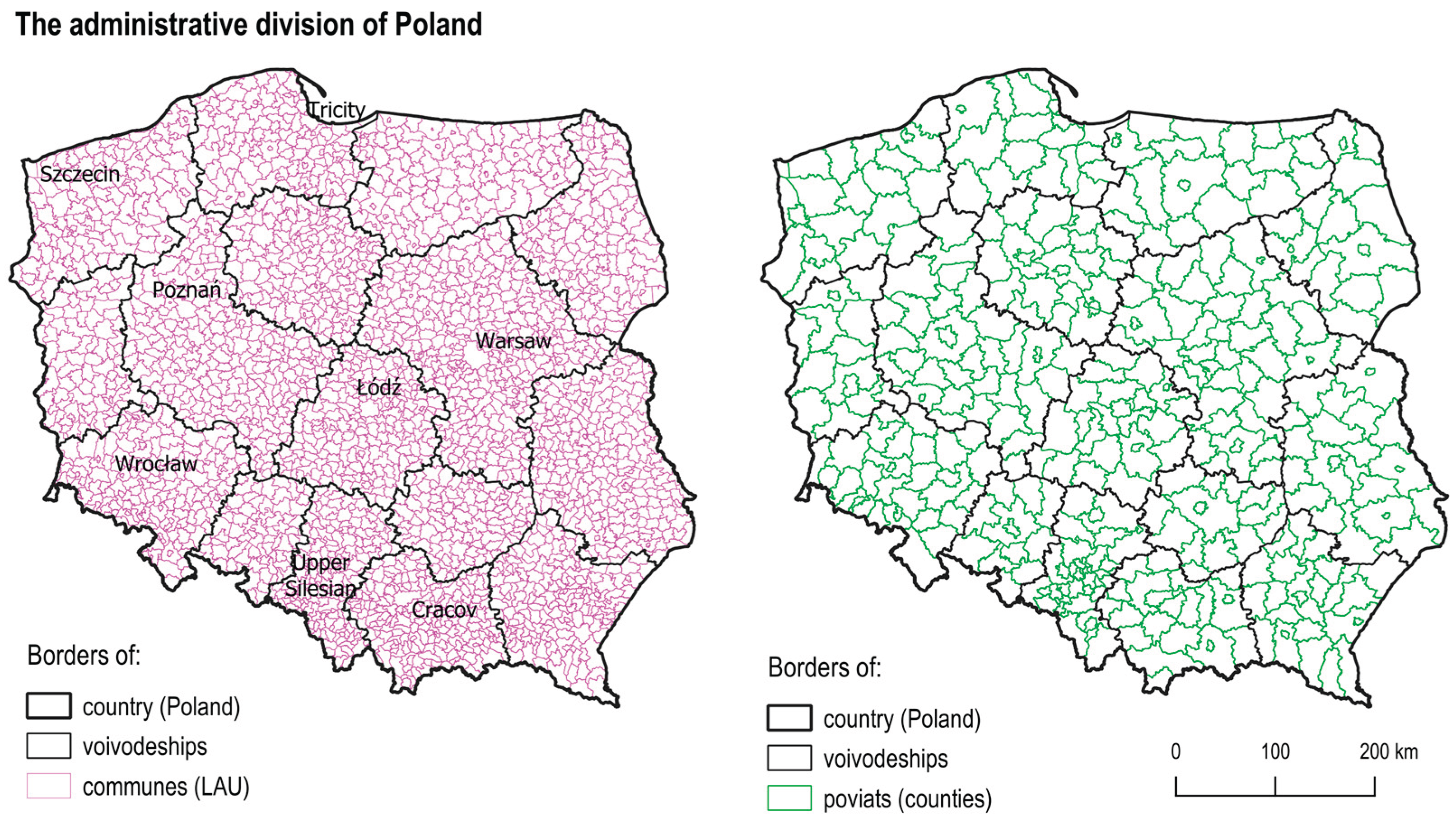

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Topic

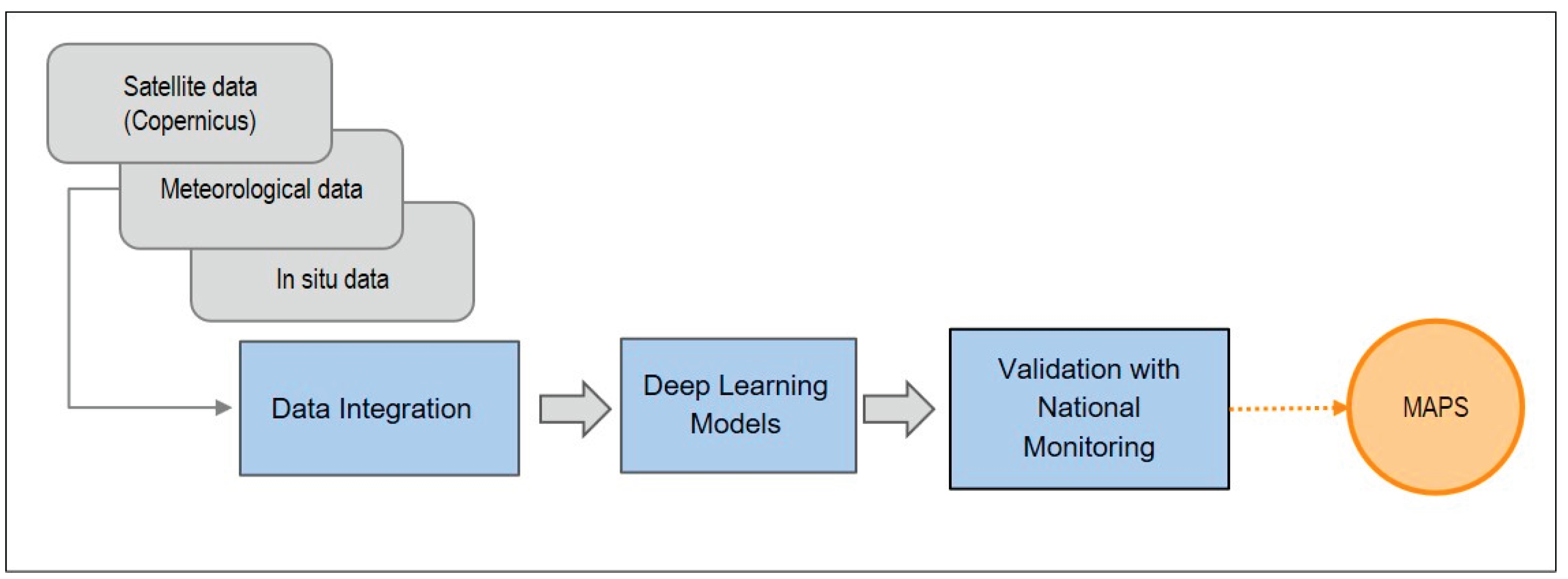

3.2.1. Air Polution

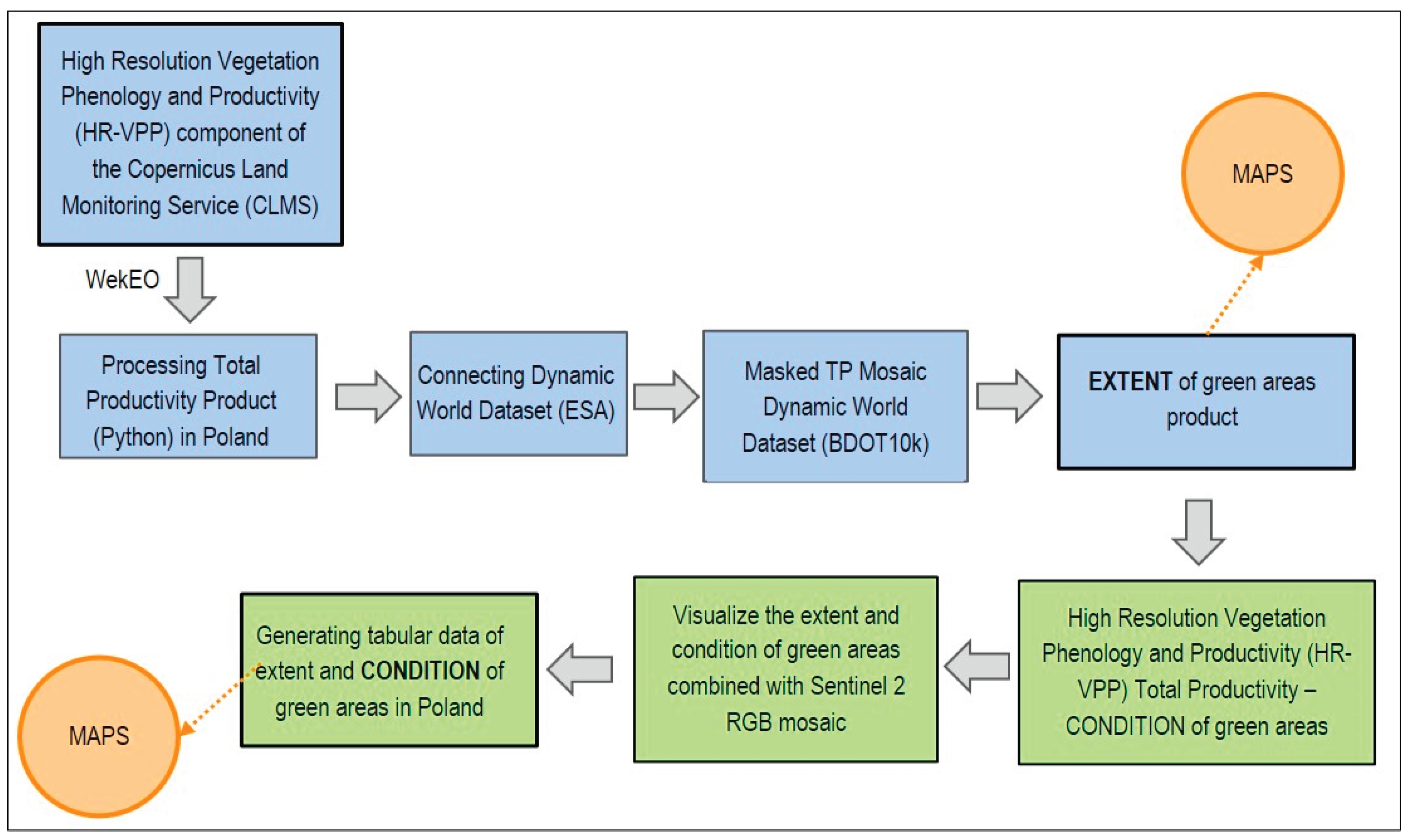

3.2.2. Green Areas

3.3. Data Sources

3.3.1. Air Polution

3.3.2. Green Areas

3.4. Map Production

3.4.1. Colour Legend

3.4.2. Choropleth Maps

3.4.3. Area Cartograms

4. Results

4.1. Air Polution

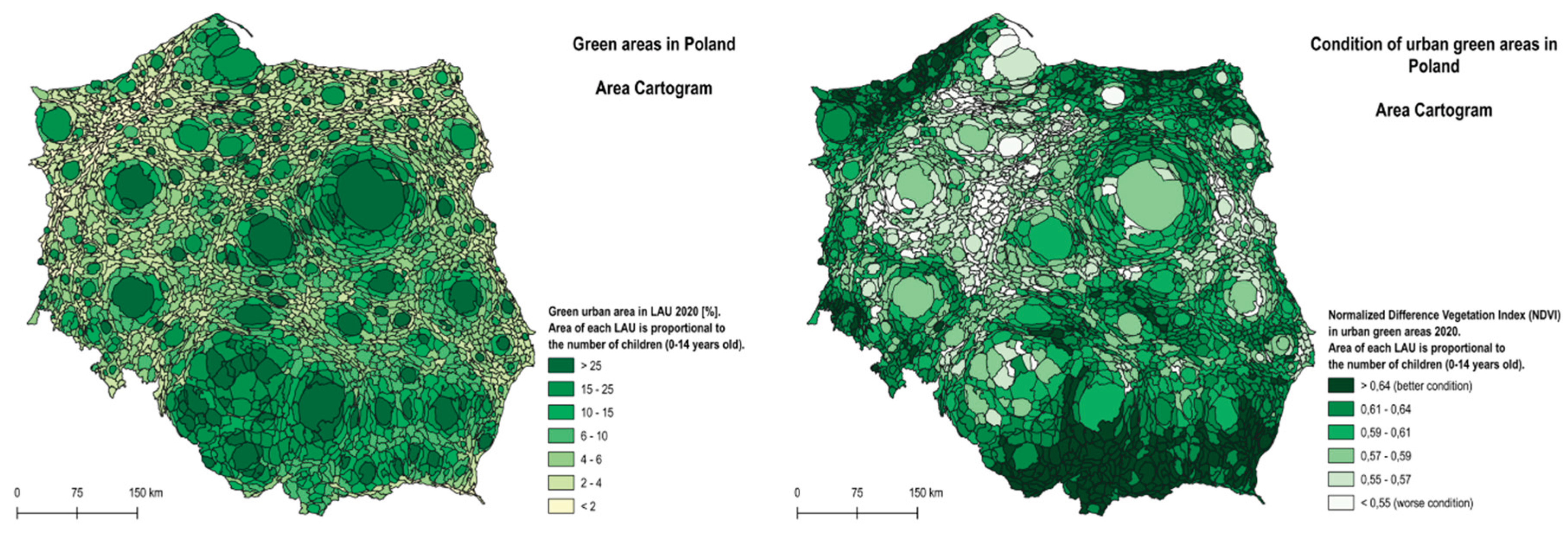

4.2. Green Areas

4. Discussion and Conclusion

- applying area cartograms to represent spatial units with highly variable population sizes at lower administrative levels (e.g., municipalities, counties). This technique enhances the visibility and interpretability of densely populated urban areas, which are often spatially limited but demographically significant;

- integrating Earth Observation data into the construction of area cartograms, which enriches the thematic content of the maps and enables more frequent and dynamic monitoring of urban environments compared to conventionally collected statistical datasets. EO-based inputs offer higher temporal resolution and spatial consistency, supporting timely assessments of sustainability indicators;

- combining area cartograms with other cartographic techniques, such as choropleth maps, proportional symbols, or qualitative and quantitative point signatures. Such hybrid visualizations provide a more comprehensive representation of SDG-related issues by simultaneously conveying multiple dimensions of the data.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDOT10k | Topographic Objects Database |

| CAMS | Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| EO | Earth observation |

| GIS | Geographic information system |

| GUGiK | Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland |

| HR-VPP | High-Resolution Vegetation Phenology and Productivity |

| LAU | Local administrative unit |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NO2 | Nitrogen oxides |

| NUTS | Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics |

| O3 | Tropospheric ozone |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| SGDs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SO2 | Sulphur dioxides |

| SP | Statistics Poland |

| UN | United Nations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- UN General Assembly, 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1, 21 October 2015. https://www.refworld.org/legal/resolution/unga/2015/en/111816.

- UN DESA, 2024. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024 – June 2024. New York, USA: UN DESA. © UN DESA. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/.

- Lamsal, L. N., Martin, R. V., Parrington, M., Krotkov, N. A., van Donkelaar, A., Celarier, E. A., ... & Sioris, C. E. (2021). A Senti-nel-5P TROPOMI derived nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) product for air quality monitoring. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 14(6), 2607–2633.

- Kassomenos, P., Bais, A., Dandou, A., & Katsafados, P. (2018). Machine learning models for predicting urban air quality using satellite and ground-based observations. Atmospheric Environment, 189, 54–66. [CrossRef]

- Buczyńska, A., Szpak, M., & Sobik-Szołtysek, J., 2020. Satellite-based assessment of air quality over Poland using Sentinel-5P data. Environmental Pollution, 263, 114462. [CrossRef]

- Panek-Chwastyk, E., Dąbrowska-Zielińska, K., Markowska, A., Kluczek, M., Pieniążek, M., 2024. Advanced utilization of satellite and governmental data for determining the coverage and condition of green areas in Poland: An experimental statistics supporting the Statistics Poland. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, Vol. 130, 103883. [CrossRef]

- Czekajlo, A., Coops, N.C., Wulder, M.A., Hermosilla, T., Lu, Y., White, J.C., Van Den Bosch, M., 2020. The urban greenness score: A satellite-based metric for multi-decadal characterization of urban land dynamics. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 93, 102210 . [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, M., Yusoff, M.M., Shafie, A., 2022. Assessing the role of urban green spaces for human well-being: A systematic review. GeoJournal 87, 4405–4423. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., Li, X., Wang, S., Gao, X., 2022. Assessing the effects of urban green landscape on urban thermal environment dynamic in a semiarid city by integrated use of airborne data, satellite imagery and land surface model. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 107, 102674 . [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., Wang, W., Ren, Z., Zhao, Y., Liao, Y., Ge, Y., Wang, J., He, J., Gu, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, W., Zhang, C. (2023) ‘Multi-scale feature fusion and transformer network for urban green space segmentation from high-resolution remote sensing images’. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observ. Geoinf. 124, 103514. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Meng, Q., Zhang, L., Hu, D., 2021. Evaluation of urban green space in terms of thermal environmental benefits using geographical detector analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 105, 102610 . [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-B., Ma, J., Meadows, M.E., Banzhaf, E., Huang, T.-Y., Liu, Y.-F., Zhao, B., 2021. Spatio-temporal changes in urban green space in 107 Chinese cities (1990–2019): The role of economic drivers and policy. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 103, 102525 . [CrossRef]

- Gelan, E., Girma, Y., 2022. Urban green infrastructure accessibility for the achievement of SDG 11 in rapidly urbanizing cities of Ethiopia. GeoJournal 87, 2883–2902. [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G., Petri, E., Interwies, E., Vysna, V., Guigoz, Y., Ray, N., Dickie, I., 2021. Modelling accessibility to urban green areas using open earth observations data: A novel approach to support the urban SDG in four European Cities. Remote Sens. (Basel) 13, 422. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Sáez, E., Lerma-Arce, V., Coll-Aliaga, E., Oliver-Villanueva, J.-V., 2021. Contribution of green urban areas to the achievement of SDGs. Case study in Valencia (Spain). Ecol. Ind. 131, 108246 . [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, A.B., Borodina, T.L., 2020. Green and digital economy for sustainable development of urban areas. Reg. Res. Russ. 10, 583–592. [CrossRef]

- Krzyżaniak, M., Świerk, D., Szczepańska, M., Urbański, P., 2018. Changes in the area of urban green space in cities of western Poland. Bull. Geogr. Soc.-Econ. Ser. 39, 65–77. [CrossRef]

- Wysmułek, J., Hełdak, M., Kucher, A., 2020. The analysis of green areas’ accessibility in comparison with statistical data in Poland. IJERPH 17, 4492. [CrossRef]

- Gavrilidis, A. A., Popa, A-M., Onose, D. A., Gradinaru, S. R., 2022, Planning small for winning big: Small urban green space distribution patterns in an expanding city, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 78 (2022) 127787. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H., 2022, Big Earth Data in Support of the Sustainable Development Goals (2022)—The Belt and Road, Sustainable Develop-ment Goals Series, Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Apilánez, B. Ormaetxea, E., Aguado-Moralejo, I., 2023, Urban Green Infrastructure Accessibility: Investigating Environmental Justice in a European and Global Green Capital. Land 2023, 12, 1534. [CrossRef]

- Stessens, P., Khan, A. Z., Marijke Huysmans, M., Canters, F., 2017, Analysing urban green space accessibility and quality: A GIS-based model as spatial decision support for urban ecosystem services in Brussels, Ecosystem Services 28 (2017) 328–340. [CrossRef]

- Vukmirovic, M., Gavrilovic, S., Stojanovic, D., 2019, The Improvement of the Comfort of Public Spaces as a Local Initiative in Coping with Climate Change, Sustainability 2019, 11, 6546; [CrossRef]

- Carbon Dioxide Emissions 2015 - Worldmapper, 2.07.2025, 13:02.

- Hennig, B., 2012, Emissions of Greenhouse Gases. https://www.viewsoftheworld.net/.

- Tian, Y., Zhu, Q., Lai K., Y.H. Lun, V., 2014, Analysis of greenhouse gas emissions of freight transport sector in China, Journal of Transport Geography 40 (2014) 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Interactive 2024 Average Air Quality Map of the Greater Cleveland Area - Mold and Air Duct Pros, May 28, 2024.

- Bertazzon, S., Shahid, R., 2019, Schools, Air Pollution, and Active Transportation: An Exploratory Spatial Analysis of Calgary, Canada, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 834; [CrossRef]

- Daramola, S.O, Makinde, E.O., 2024, Modeling air pollution around major dumpsites in Lagos State using geospatial methods with solutions, Environmental Challenges 16 (2024) 100969. [CrossRef]

- Duan, J., Li, Y., Li, S., Yang, Y., Li, F., Li, Y., Wang, J., Deng, P., Wu, J., Wang, W., Meng, Ch., Miao, R., Chen, Z., Zou, B., Yuan, H., Cai, J., Lu, Y., 2022, Association of Long-term Ambient Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) and Incident CKD: Prospective Cohort Study in China, AJKD Vol 80, Iss 5, November 2022. [CrossRef]

- Habermann, M., Billger, M., Haeger-Eugensson, M., 2015, Land use regression as method to model air pollution. Previous results for Gothenburg/Sweden, Procedia Engineering 115 ( 2015 ) 21 – 28. [CrossRef]

- Lisberg Jensen, E., Karin Westerberg, K., Malmqvist, E., Oudin, A., 2020, Through Internet and Friends: Translation of Air Pollu-tion Research in Malmö Municipality, Sweden, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4214; [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Bertazzon, S., 2016, Fine Scale Spatio-Temporal Modelling of Urban Air Pollution, J.A. Miller et al. (Eds.): GIScience 2016, LNCS 9927, pp. 210–224, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Mijling, B., 2020, High-resolution mapping of urban air quality with heterogeneous observations: a new methodology and its application to Amsterdam, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 13, 4601–4617, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Obanya, H.E., Amaeze,N.H., Togunde, O., Otitoloju,A.A., 2018, Air Pollution Monitoring Around Residential and Transportation Sector Locations in Lagos Mainland, Journal of Health & Pollution Vol. 8, No. 19 — September 2018.

- Sówka, I., Cichowicz, R., Dobrzański, M.., Bezyk, Y., 2023, Analysis of Air Pollutants for a Small Paintshop by Means of a Mobile Platform and Geostatistical Methods. Energies 2023, 16, 7716. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A., Qi, Q., Jiang, L., Zhou, F., Wang, J., 2013, Population Exposure to PM2.5 in the Urban Area of Beijing. PLoS ONE 8(5): e63486. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T., Li, F., Niu, W., Gao, Z., Han, Y., Zhang, X., 2021, Health Risk Assessment of Toxic and Harmful Air Pollutants Discharged by a Petrochemical Company in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region of China. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1604. [CrossRef]

- El Ghazi, I., Berni, I., Menouni, A., Amane, M., Kestemont, M.-P., El Jaafari, S., 2022, Exposure to Air Pollution from Road Traffic and Incidence of Respiratory Diseases in the City of Meknes, Morocco. Pollutants 2022, 2, 306–327. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Sun, W., Huai, B., Wang, L., Han, Ch., Wang, Y., Mi, W., 2023, Seasonal variation and sources of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a background site on the Tibetan Plateau, Journal of Environmental Sciences 125 (2023) 524–532.

- Che, W., Zhang, Y., Lin Ch., Fung, Y.H., Fung J.C.H., Lau A.K.H., 2023, Impacts of pollution heterogeneity on population exposure in dense urban areas using ultra-fine resolution air quality data, Journal of Environmental Sciences 125 (2023) 513–523.

- Bailey, J., Ramacher, M.O.P., Speyer, O., Athanasopoulou, E., Karl, M., Gerasopoulos, E., 2023, Localizing SDG 11.6.2 via Earth Observation, Modelling Applications, and Harmonised City Definitions: Policy Implications on Addressing Air Pollution. Re-mote Sens. 2023, 15, 1082. [CrossRef]

- Ta Bui, L., Nguyen, P.H., My Nguyen, D.Ch., 2021, Linking air quality, health, and economic effect models for use in air pollution epidemiology studies with uncertain factors, Atmospheric Pollution Research 12 (2021) 101118. [CrossRef]

- Guttikunda, S. K., Goel, R., Mohan, D., Tiwari, G.,Gadepalli, R., 2015, Particulate and gaseous emissions in two coastal cities - Chennai and Vishakhapatnam, India, Air Quality Atmosphere & Health · December 2015. [CrossRef]

- Holnicki, P., Kałuszko, A., Nahorski, Z., Stankiewicz, K., Trapp, W., 2017, Air quality modeling for Warsaw agglomeration, Archives of Environmental Protection, Vol. 43 no. 1 pp. 48–64. [CrossRef]

- Holnicki, P., Kałuszko, A, 2014, Supporting management of air quality in an urban area, Research Report RB/5/2014, Systems Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, 12 p.

- Janssen, S., Dumont, G., Fierens, F., Mensink, C., 2008, Spatial interpolation of air pollution measurements using CORINE land cover data, Atmospheric Environment 42 (2008) 4884–4903. [CrossRef]

- Nhung, N.T.T., Jegasothy, E., Ngan, N.T.K., Truong, N.X., Thanh, N.T..N, Marks, G.B., Morgan, G.G., 2022, Mortality Burden due to Exposure to Outdoor Fine Particulate Matter in Hanoi, Vietnam: Health Impact Assessment, International Journal of Public Health, 67:1604331. [CrossRef]

- Talianu, C., Vasilescu, J., Nicolae, D., Ilie, A., Dandocsi, A., Nemuc, A., Belegante, L., 2025, High-resolution air quality maps for Bucharest using a mixed-effects modeling framework, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 25, 4639–4654, 2025 . [CrossRef]

- Vohra, K.., Vodonos, A., Schwartz, J., Marais, E.A., Sulprizio, M.P., Mickley, L.J., 2021, Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem, Environmental Research 195 (2021) 110754. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Johnson, G., Kavouras, I.G., 2022, The Effect of Transportation and Wildfires on the Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of PM2.5 Mass in the New York-New Jersey Metropolitan Statistical Area, Environmental Health Insights, Volume 16: 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Wallek, S., Langner, M., Schubert, S., Schneider, C., 2022, Modelling Hourly Particulate Matter (PM10) Concentrations at High Spatial Resolution in Germany Using Land Use Regression and Open Data. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1282. [CrossRef]

- Shelestov, A., Yailymova, H., Yailymov, B., Kussul, N., 2021, Air Quality Estimation in Ukraine Using SDG 11.6.2 Indicator Assessment, Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 4769. [CrossRef]

- Bertazzon, S., Shahid, R., 2019, Schools, Air Pollution, and Active Transportation: An Exploratory Spatial Analysis of Calgary, Canada, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 834; [CrossRef]

- Gerasopoulos, E., 2019, SMURBS project’s portfolio of solutions for smart cities, Innovation News Network. https://www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/smurbs-projects-portfolio-of-solutions-for-smart-cities/1023/.

- Hansman, H., 2015, The EPA Has a New Tool For Mapping Where Pollution and Poverty Intersect. To better target its efforts, the agency is identifying problem areas, where people are facing undueenvironmental. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/epa-has-new-tool-mapping-where-pollution-poverty-intersect-180955663/.

- Ncongwane, K., Mayana, L., Yigiletu M., Malatji, S., Wright, C., 2021, The Impact of Air Pollution on Public Health through the Lens of the South African Weather Service Air Quality Monitoring Programme, Just Transition_28_October_2021.

- Chen, X., Ting Yang, T., Haibo Wang, H., Futing Wang, F., Wang, Z., 2023, Variations and drivers of aerosol vertical characterization after clean air policy in China based on 7-years consecutive observations, journal of Environmental Sciences 125 (2023) 499–512, . [CrossRef]

- Xing, X., Chen, Z., Tian, Q., Mao, Y., Liu, W., Shi, M., Cheng, Ch., Hu, T., Zhu, G., Li, Y., Zheng, H., Zhang, J., Kong, S., Qi, S., 2020, Characterization and source identification of PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban, suburban, and rural ambient air, central China during summer harvest, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 191 (2020) 110219. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, C., Hecht, R., Lautenbach, S., Schorcht, M., Zipf, A., 2021, Mapping Public Urban Green Spaces Based on OpenStreetMap and Sentinel-2 Imagery Using Belief Functions. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 251. [CrossRef]

- Łaszkiewicz, E., Wolff, M., Andersson, E., Kronenberg, J., Barton, D.N., Haase, D., Langemeyer, J., Baró, F., McPhearson, P., 2022, Greenery in urban morphology: a comparative analysis of differences in urban green space accessibility for various urban structures across European cities. Ecology and Society 27(3):22. [CrossRef]

- Rivas Navarro, J.L., Bravo Rodríguez, B., 2013, Creative City in Suburban Areas: Geographical and Agricultural Matrix as the Basis for the New Nodal Space, Spaces and Flows: an International Journal of Urban and Extraurban Studies, vol. 3, nr. 4. [CrossRef]

- Sanga, Å. O., Knez,I., Gunnarsson, B., Hedblom, M., 2016, The effects of naturalness, gender, and age on how urban green spaceis perceived and used, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 18 (2016) 268–276. [CrossRef]

- Schipperijn, J., 2010, Use of urban green space. Forest & Landscape Research No. 45-2010. Forest & Landscape Denmark, Frederiksberg, 155 pp., 978-87-7903-461-7 (internet).

- Zhang, L., Cao, H., Han, R., 2021, Residents’ Preferences and Perceptions toward Green Open Spaces in an Urban Area. Sustaina-bility 2021, 13, 1558. [CrossRef]

- Zsolt Farkas, J., Kovács, Z., Csomós, G., 2022, The availability of green spaces for different socio-economic groups in cities: a case study of Budapest, Hungary, Journal of Maps, 18:1, 97-105. [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, S., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Ambròsa, A., Wegenere, S., Muellera, N., 2020, Is a liveable city a healthy city? Health impacts of urban and transport planning in Vienna, Austria, Environmental Research 183 (2020) 109238, . [CrossRef]

- Pristeri, G., Peroni, F., Pappalardo, S.E., Codato, D., Masi, A., De Marchi, M., 2021, Whose Urban Green? Mapping and Classifying Public and Private Green Spaces in Padua for Spatial Planning Policies. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 538. [CrossRef]

- Sathyakumar, V., Ramsankaran, R.A.A.J., Bardhan, R., 2019, Linking remotely sensed Urban Green Space (UGS) distribution patterns and Socio-Economic Status (SES) - A multi-scale probabilistic analysis based in Mumbai, India, GIScience & Remote Sensing, 56:5, 645-669. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Wang, X., Zhu, J., Chen, L., Jiae, Y., Lawrence, J.M., Jiang, L., Xiaohui Xie, X., Wua,⁎J., 2021, Using machine learning to examine street green space types at a high spatial resolution: Application in Los Angeles County on socioeconomic disparities in exposure, Science of the Total Environment 787 (2021) 147653. [CrossRef]

- Valente, D., Marinelli, M.V., Lovello, E.M., Giannuzzi, C.G., Petrosillo, I., 2022, Fostering the Resiliency of urban Landscape through the Sustainable Spatial Planning of Green Spaces. Land 2022, 11, 367. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, K., and Lee, D., 2021, Environmental Justice and Green Infrastructure in the Ruhr. From Distributive to Institutional Conceptions of Justice. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:670190. [CrossRef]

- Artmann, M., Mueller, C., Goetzlich, L., Hof, A., 2019, Supply and Demand Concerning Urban Green Spaces for Recreation by Elderlies Living in Care Facilities: The Role of Accessibility in an Explorative Case Study in Austria. Front. Environ. Sci. 7:136. [CrossRef]

- Jobes, J., Whicheloe, R., 2025, Greening the grey: Does urban green space cater for societal well-being and biodiversity?, 2025, ialeUK - International Association for landscape Ecology, https://iale.uk/greening-grey-does-urban-green-space-cater-societal-well-being-and-biodiversity.

- Rubaszek, J., Gubański, J., Podolska, A., 2023, Do We Need Public Green Spaces Accessibility Standards for the Sustainable Development of Urban Settlements? The Evidence from Wrocław, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3067. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Silva, C., Viegas, I., Panagopoulos, T., Bell, S., 2018, Environmental Justice in Accessibility to Green Infrastructure in Two European Cities, Land 2018, 7, 134; [CrossRef]

- Heikinheimoa, V., Tenkanena,H., Bergrotha,C., Järva, O., Hiippalaa, T., Toivonena, T., 2020, Understanding the use of urban green spaces from user-generated geographic information, Landscape and Urban Planning 201 (2020) 103845. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Kwan, M.-P., Kan, Z., 2021, Analysis of urban green space accessibility and distribution inequity in the City of Chicago, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 59 (2021) 127029. [CrossRef]

- Lwin, K.K., Murayama, Y., 2011, Modelling of urban green space walkability: Eco-friendly walk score calculator, Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 35 (2011) 408–420. [CrossRef]

- Torres Toda, M., Miri, M., Alonso, L., Gomez-Roig, M.D, Foraster, M., Dadvand, P., 2020, Exposure to greenspace and birth weight in a middle-income country, Environmental Research 189 (2020) 109866. [CrossRef]

- Viinikka, A., Tiitu, M., Heikinheimo, V., Halonen, J.I., Nyberg, E., Vierikko, K., 2023, Associations of neighborhood-level socioeconomic status, accessibility, and quality of green spaces in Finnish urban regions, Applied Geography 157 (2023) 102973. [CrossRef]

- Ben, S, Zhu, H., Lu, J., Wang, R., 2023, Valuing the Accessibility of Green Spaces in the Housing Market: A Spatial Hedonic Anal-ysis in Shanghai, China. Land 2023, 12, 1660. [CrossRef]

- Bernabeu-Bautista, A., Serrano-Estrada, L., Martí, P., 2023, The role of successful public spaces in historic centres. Insights from social media data, Cities 137 (2023) 104337. [CrossRef]

- Borie, M., Gina Ziervogel, G., Taylor, F.E., Millington, J.D.A., Sitas, R., Pelling, M., 2019, Mapping (for) resilience across city scales: An opportunity to open-up conversations for more inclusive resilience policy?, Environmental Science and Policy 99 (2019) 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Halecki, W., Stachura, T., Fudała, W., Stec, A., Kuboń, S., 2023, Assessment and planning of green spaces in urban parks: A review, Sustainable Cities and Society 88 (2023) 104280. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Lan, Z., 2019, Park green spaces, public health and social inequalities: Understanding the interrelationships for policy implications, Land Use Policy 83 (2019) 66–74. [CrossRef]

- Valença Pinto, L., Miguel Inacio, M., Carla Sofia Santos Ferreira, C.S., Dinis Ferreira, A., Pereira, P., 2022, Ecosystem services and well-being dimensions related to urban green spaces – A systematic review, Sustainable Cities and Society 85 (2022) 104072.

- Talav Era, R., 2012, Improving Pedestrian Accessibility to Public Space through Space Syntax Analysis, Proceedings: Eighth International Space Syntax Symposium Santiago, PUC, 2012.

- Zulian, G., Marando, F., Mentaschi, L., Alzetta, C., Wilk, B., Maes, J., 2022, Green balance in urban areas as an indicator for policy support: a multi-level application. One Ecosystem 7: e72685. [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G., Petri, E., Interwies, E., Vysna, V., Guigoz, Y., Ray, N., Dickie, I., 2021. Modelling accessibility to urban green areas using open earth observations data: A novel approach to support the urban SDG in four European Cities. Remote Sens. (Basel) 13, 422. [CrossRef]

- Mercader-Moyano, P., Estable-Reifs, A.M., Pellicer, H., 2021, Toward the Renewal of the Sustainable Urban Indicators’ System after a Global Health Crisis. Practical Application in Granada, Spain. Energies 2021, 14, 6188. [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W., Peters, G.P., Gasser, T., Andrew, R.M., Schwingshackl, C., Gütschow, J., Houghton, R.A., Friedlingstein, P., Pongratz, J., Le Quéré, C., 2023, National contributions to climate change due to historical emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and ni-trous oxide since 1850, Nature, Scientific Data, 2023, 10:155. [CrossRef]

- Kharas, H., Fengler, W., Vashold, L., 2023, Have we reached peak greenhouse gas emissions? https://www.brookings.edu/articles/have-we-reached-peak-greenhouse-gas-emissions/.

- Liu, X., Yuan, M., 2023, Assessing progress towards achieving the transport dimension of the SDGs in China, Science of the Total Environment 858 (2023) 159752. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Zhu, Q., Lai K., Y.H. Lun, V., 2014, Analysis of greenhouse gas emissions of freight transport sector in China, Journal of Transport Geography 40 (2014) 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Janssens-Maenhout, G., Crippa1, M., Guizzardi, D., Muntean, M., Schaaf, E., Dentener, F., Bergamaschi, P., Pagliari, V., Olivier, J.G.J., Peters, J.A.H.W., van Aardenne, J.A., Monni, S., Doering, U., Petrescu, A.M.R., Solazzo, E., Oreggioni, G.D., 2019, ED-GAR v4.3.2 Global Atlas of the three major greenhouse gas emissions for the period 1970–2012, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 11, 959–1002, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Whetstone, J., Mueller, K. Prothero, J., 2025, GReenhouse Gas And AirPollutants Emissions System(GRA2PES) Report, National Instutute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/greenhouse-gas-and-air-pollutants-emissions-system-gra2pes.

- World Meteorological Organization, 2025, Executive Council approves GlobalGreenhouse Gas Watch implementationplan. https://wmo.int/media/news/executive-council-approves-global-greenhouse-gas-watch-implementation-plan, 2.07.2025, 12:50.

- Sapkota, T.B., Khanamb, F., Mathivanan, G.P, Vetter, S., Hussainb, Sk.G., Pilat, A-L., Shahrin, S., Hossain, Md.K., Sarker, N.R., Krupnik, T.J., 2021, Quantifying opportunities for greenhouse gas emissionsmitigation using big data from smallholder crop and livestock farmers across Bangladesh, Science of the Total Environment 786 (2021) 147344.

- Guo, H., 2022, Big Earth Data in Support of the Sustainable Development Goals (2022)—The Belt and Road, Sustainable Develop-ment Goals Series, Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Hennig, B., 2012, Emissions of Greenhouse Gases. https://www.viewsoftheworld.net/.

- World Health Organization, 2021, WHO global air quality guidelines: Particulate matter (PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228.

- Act of 16 April 2004 on Nature Protection, Place of publication: Dziennik Ustaw: 021 r. poz. 1098, z późn. zm.

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts., 2024, CAMS Reanalysis (EAC4). Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. https://atmosphere.copernicus.eu.

- Markowska, A., 2019. Cartograms – classification and terminology. Polish Cartographical Review, Vol. 51(2), pp. 51–65. [CrossRef]

- Markowska, A., Korycka-Skorupa, J.,2015, An evaluation of GIS tools for generating area cartograms. Polish Cartographical Review, 47(1), 19–29. [CrossRef]

- Gastner, M. T., & Newman, M. E. J., 2004, Diffusion-based method for producing density-equalizing maps. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(20), 7499–7504.

- Heilmann, H., S. Stauffer, S., & Meyer, M. D., 2015, RecMap: Rectangular Cartogram Generation. R package version 1.0.2. https://cran.r-project.org/package=RecMap.

- Fink, C. (2022). cartogram3: QGIS3 plugin to create anamorphic maps. https://github.com/austromorph/cartogram3 https://github.com/austromorph/cartogram3.

- Jeworutzki, S., Giraud, T., Lambert, N., Bivand, R., Pebesma, E., & Nowosad, J. (2023). Cartogram: Create Cartograms with R (Version 0.3.0). CRAN. [CrossRef]

- Gastner, M.T., Seguy, V. & More, P., 2018, Fast flow-based algorithm for creating density-equalizing map projections, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 (10) E2156-E2164. [CrossRef]

- Kraak MJ, RE Roth, B Ricker, A Kagawa, and G Le Sourd. 2020. Mapping for a Sustainable World. United Nations: New York, NY (USA).

| Color | PM2.5 Range (µg/m³) |

PM10 Range (µg/m³) |

Nitrogen Oxides (NOₓ) Range (µg/m³) | Air Quality Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | 0 – 12 | 0 – 20 | 0 – 40 | Good air quality |

| Yellow | 12 – 35 | 20 – 50 | 40 – 90 | Moderate air quality |

| Orange | 35 – 55 | 50 – 100 | 90 – 180 | Unhealthy for sensitive groups |

| Red | 55 – 150 | 100 – 200 | 180 – 280 | Unhealthy |

| Purple | >150 | >200 | >280 | Very unhealthy /Hazardous |

| Tools | Software / Language | Cartogram Type | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| ScapeToad | Java | Irregular – Gastner-Newman |

Desktop application, diffusion algorithm [107] |

| Cartogram Geoprocessing Tool | ArcGIS Toolbox | Irregular – Gastner-Newman |

Implements Gastner-Newman algorithm within ArcGIS environment |

| RecMap | R | Rectangular or Mosaic | Produces cartograms using rectangular subdivision with attribute scaling [108] |

| Tilegrams | JavaScript | Hexagonal | Uses equal-sized hexagons or squares; suitable for web presentations (Pitch Interactive) |

| cartogram 3 | Python (PyQGIS) QGIS Plugin |

Irregular – Gastner-Newman |

Integrates cartogram generation into open-source QGIS environment [109] |

| cartogram: Create Cartograms with R | R | Irregular – gridded | It is actively maintained and suitable for creating gridded cartograms [110] |

| go-cart | C++ | Irregular– Flow-Based | Create a area cartogram, using Flow-Based-Algorithm [111] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).