Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Research Questions and Theoretical Framework

- How are structural changes in higher education influencing faculty entrepreneurship opportunities and activities?

- What are the demonstrated benefits, limitations, and potential drawbacks of faculty entrepreneurship for individuals, institutions, and knowledge ecosystems?

- What barriers impede faculty entrepreneurship, and how do these impact different faculty populations?

- What evidence-based approaches can institutions implement to support ethical and effective faculty entrepreneurship?

- Disciplines (8 STEM, 8 business/economics, 8 social sciences, 8 humanities/arts)

- Institution types (14 research universities, 10 comprehensive universities, 8 liberal arts/teaching-focused institutions)

- Career stages (10 assistant professors, 12 associate professors, 10 full professors)

- Demographics (16 women, 16 men; 12 faculty of color, 20 white faculty)

- Funding constraints: Public funding for higher education has declined by 13% per student (inflation-adjusted) over the past decade across OECD countries, creating financial pressure on institutions and faculty (OECD, 2023; Mitchell et al., 2019)

- Employment model shifts: The proportion of contingent faculty has grown to represent over 70% of instructional positions in U.S. higher education, fundamentally altering career stability and progression (AAUP, 2022; Kezar et al., 2019)

- Accountability demands: Institutions face intensifying pressure to demonstrate tangible impact, knowledge transfer, and societal relevance beyond traditional academic metrics (Perkmann et al., 2021; Hazelkorn, 2015)

- Knowledge dissemination evolution: Digital platforms have disrupted traditional knowledge gatekeeping, creating alternative channels for academic expertise dissemination (Weller, 2018; Levin & Greenwood, 2016)

- Corporate research partnerships with universities have increased by 27% over the past decade (Tartari & Breschi, 2012; NSF, 2022)

- A survey of 412 Fortune 1000 companies found that 63% reported seeking academic expertise for specialized consulting projects, particularly in data science, sustainability, and organizational behavior (Cohen et al., 2020)

- The professional development and thought leadership market has grown to approximately $40 billion globally according to multiple market analyses, with academic experts particularly valued for their research foundations (Bothwell, 2021; Aguinis et al., 2014)

- Individual factors: Expertise characteristics, career stage, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, risk tolerance, and identity orientation

- Institutional factors: Policy environment, support resources, disciplinary culture, and evaluation systems

- Environmental factors: Market demand, regional economic conditions, and external network access

- Engagement patterns: Time investment, integration with academic work, and ethical frameworks

- Demographic factors: Gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic background

- Institutional mediation: Policy implementation, resource allocation, and cultural reception

- Knowledge services: Consulting, advisory work, and expert testimony

- Knowledge dissemination: Speaking, training, and workshop facilitation

- Knowledge products: Books, courses, assessments, and educational resources

- Knowledge ventures: Startups, innovations, and commercial applications

- Paid speaking engagements (68%)

- Consulting (62%)

- Training/workshop facilitation (53%)

- Content creation (42%)

- Expert testimony (23%)

- Product development (19%)

- Startup ventures (12%)

- STEM faculty primarily engaged in technical consulting (75%) and industry-sponsored research (63%)

- Business faculty most commonly reported executive education (88%) and corporate advising (75%)

- Social science faculty focused on assessment tool development (63%) and organizational consulting (50%)

- Humanities faculty primarily pursued speaking engagements (88%) and content creation (75%)

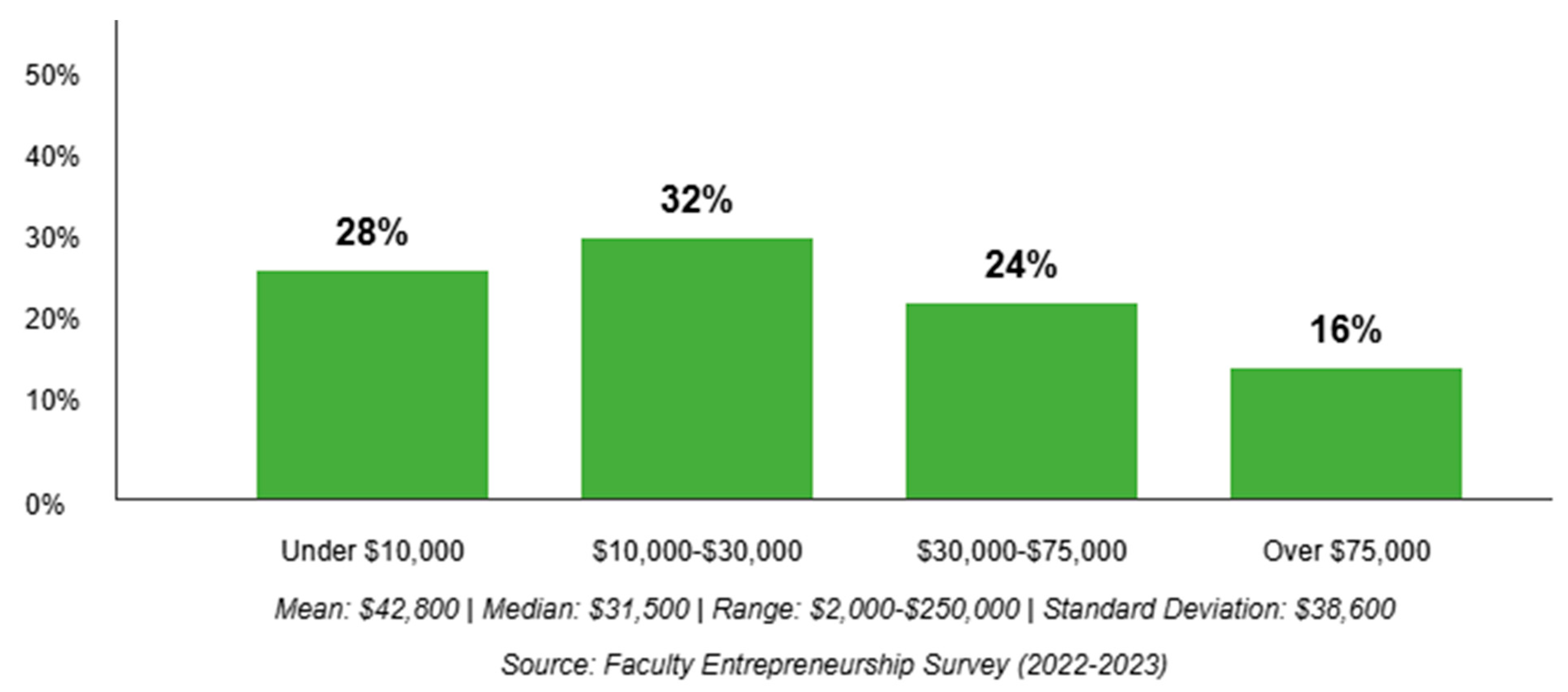

- Financial impact: Faculty entrepreneurs in the survey sample (n=106) reported supplemental income ranging from 2,000to2,000 to 2,000to250,000 annually, with a median of 31,500andmeanof31,500 and mean of 31,500andmeanof42,800 (SD=$38,600). This wide variance was influenced by discipline, experience, engagement level, and market factors (Figure 3).

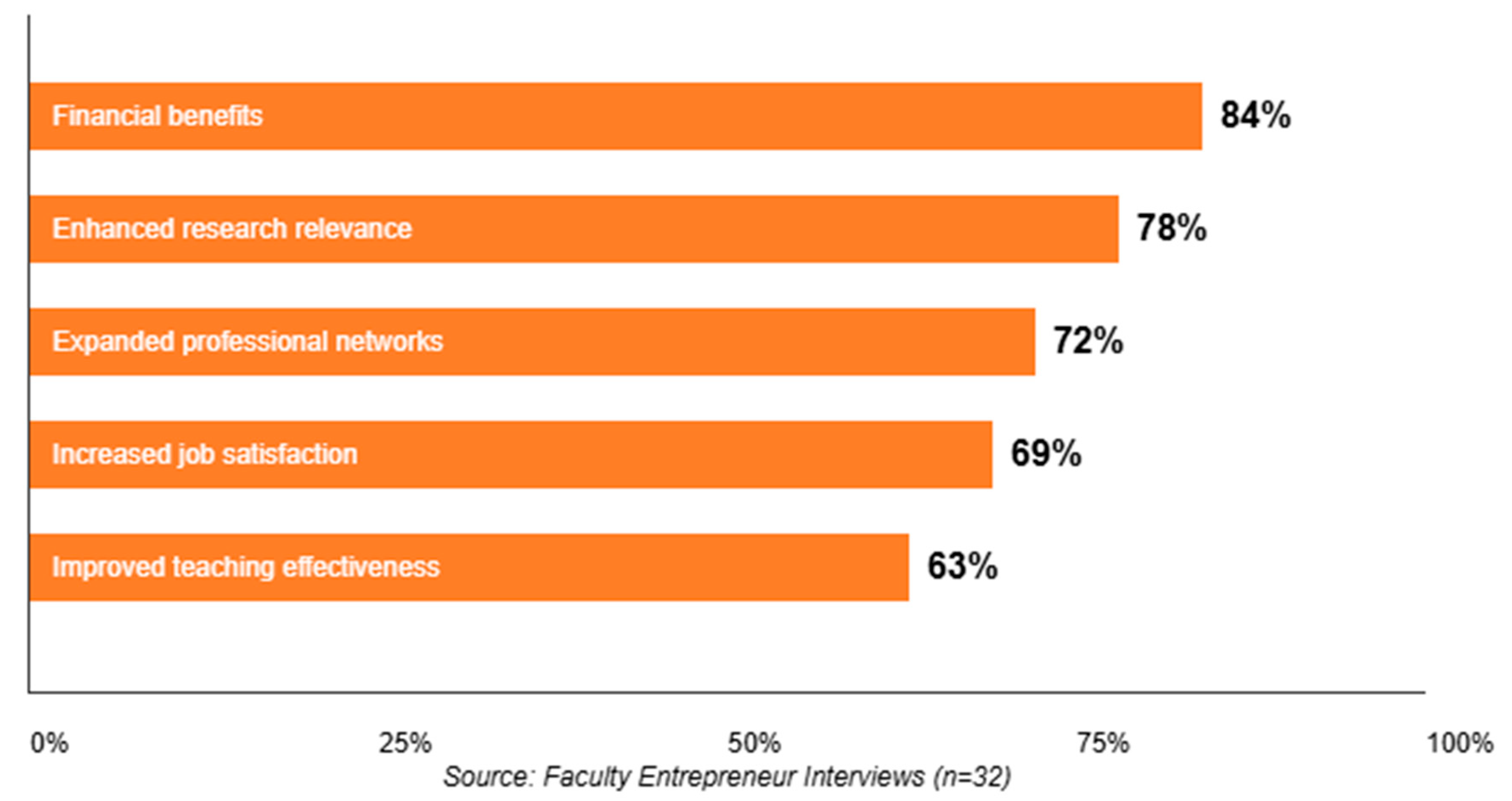

- Career satisfaction: The survey found that entrepreneurially active faculty reported significantly higher job satisfaction (M=4.2 on 5-point scale, SD=0.7) compared to non-entrepreneurial faculty (M=3.7, SD=0.8), t(244)=5.21, p<.001, d=0.67, 95% CI [0.41, 0.93]. This relationship was moderated by institutional support for entrepreneurship (β=.28, p<.01), with the satisfaction differential reduced in unsupportive environments.

- Research impacts: Evidence on productivity effects is mixed. Faculty entrepreneurs in the survey reported publishing an average of 3.8 peer-reviewed articles in the past two years compared to 3.2 for non-entrepreneurs, a statistically significant difference (t(244)=2.36, p=.019, d=0.30, 95% CI [0.05, 0.55]). However, multiple linear regression analysis revealed a curvilinear relationship between entrepreneurial time investment and publication output (β time=.24, p<.01; β time²=-.31, p<.001), suggesting potential threshold effects where excessive entrepreneurial activity correlates with decreased scholarly output.

- Network expansion: Faculty entrepreneurs reported significantly more cross-sector professional connections (M=12.3, SD=6.1) than non-entrepreneurs (M=7.8, SD=4.9), t(244)=6.42, p<.001, d=0.82, 95% CI [0.56, 1.08].

- Skill development: 83% of entrepreneurially active faculty reported that entrepreneurial activities had improved their teaching effectiveness through enhanced real-world application, while 76% reported improved communication skills.

- Knowledge transfer metrics: Faculty entrepreneurship activities directly contribute to institutional impact measures increasingly valued by funders and accreditors (Siegel & Wright, 2015; Hazelkorn, 2015)

- Industry connections: Faculty entrepreneurs create pathways for broader institutional partnerships, with survey data indicating that 38% of faculty consulting relationships led to additional institutional engagement within two years. Linear regression analysis identified faculty entrepreneurial activity as a significant predictor of institutional industry partnerships (β=.27, p<.001).

- Faculty retention: The survey revealed that entrepreneurially active faculty reported significantly higher institutional commitment (M=4.0 on 5-point scale, SD=0.8) compared to non-entrepreneurial peers (M=3.5, SD=0.9), t(244)=4.18, p<.001, d=0.53, 95% CI [0.28, 0.79], with strongest effects among mid-career faculty. Longitudinal data from institutional retention reports indicated that institutions with supportive entrepreneurial policies retained 23% more entrepreneurially active faculty over a five-year period compared to those with restrictive policies (χ²=12.41, p<.001, φ=0.26).

- Student opportunities: Faculty with active industry engagement reported creating an average of 3.2 student internship or employment opportunities annually compared to 1.4 for non-engaged faculty (t(244)=5.72, p<.001, d=0.73, 95% CI [0.47, 0.99])

- Faculty entrepreneurship may divert attention from core teaching and service responsibilities if inadequately managed (Czarnitzki et al., 2015)

- Uneven entrepreneurial opportunities across disciplines may exacerbate resource and prestige disparities within institutions (Lockett et al., 2022)

- Conflicts of interest require careful management to maintain institutional integrity (Williams-Jones, 2013)

- Knowledge application: Faculty entrepreneurs can accelerate the translation of research into practice, potentially reducing the often-cited 17-year gap between discovery and implementation in fields like healthcare (Green et al., 2014; Morris et al., 2011)

- Cross-sector collaboration: Entrepreneurial activities create bridges between academic, industry, government, and nonprofit sectors, facilitating multidirectional knowledge flows (Etzkowitz, 2017; Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015)

- Workforce development: Faculty entrepreneurs contribute to workforce preparation by bringing current industry challenges into curriculum and training (Perkmann et al., 2013; Siegel & Wright, 2015)

- 72% reported that their work directly improved practice in their field

- 57% created resources or tools used by practitioners

- 43% influenced policy or decision-making in their areas of expertise

- However, critical perspectives highlight important limitations:

- Knowledge commodification may restrict access to insights that would otherwise be publicly available (Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004)

- Entrepreneurial priorities may skew research agendas toward commercially viable topics rather than socially important questions (Washburn, 2008)

- Benefits may flow primarily to already-advantaged communities and organizations rather than those with greatest need (Deem et al., 2007)

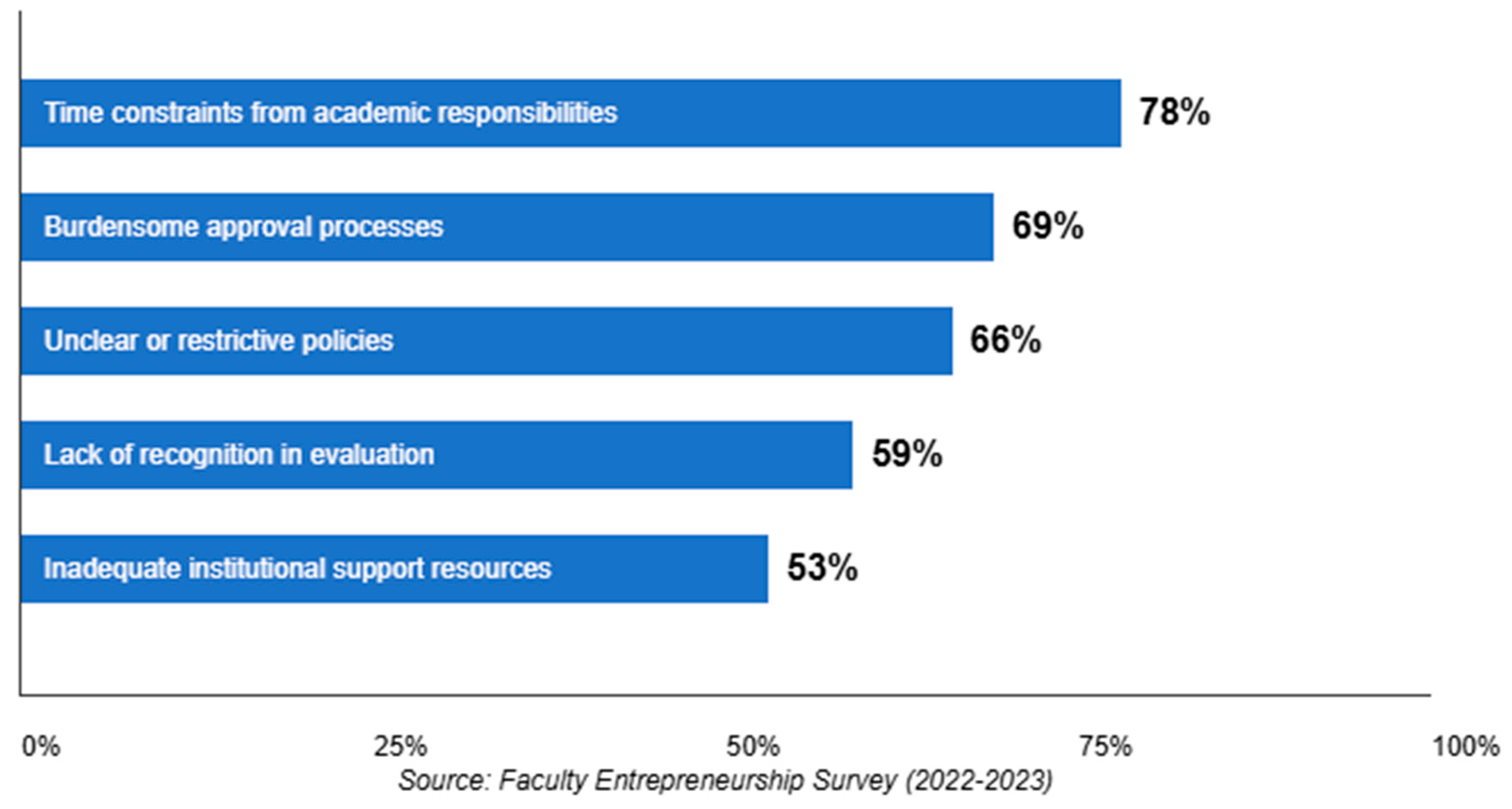

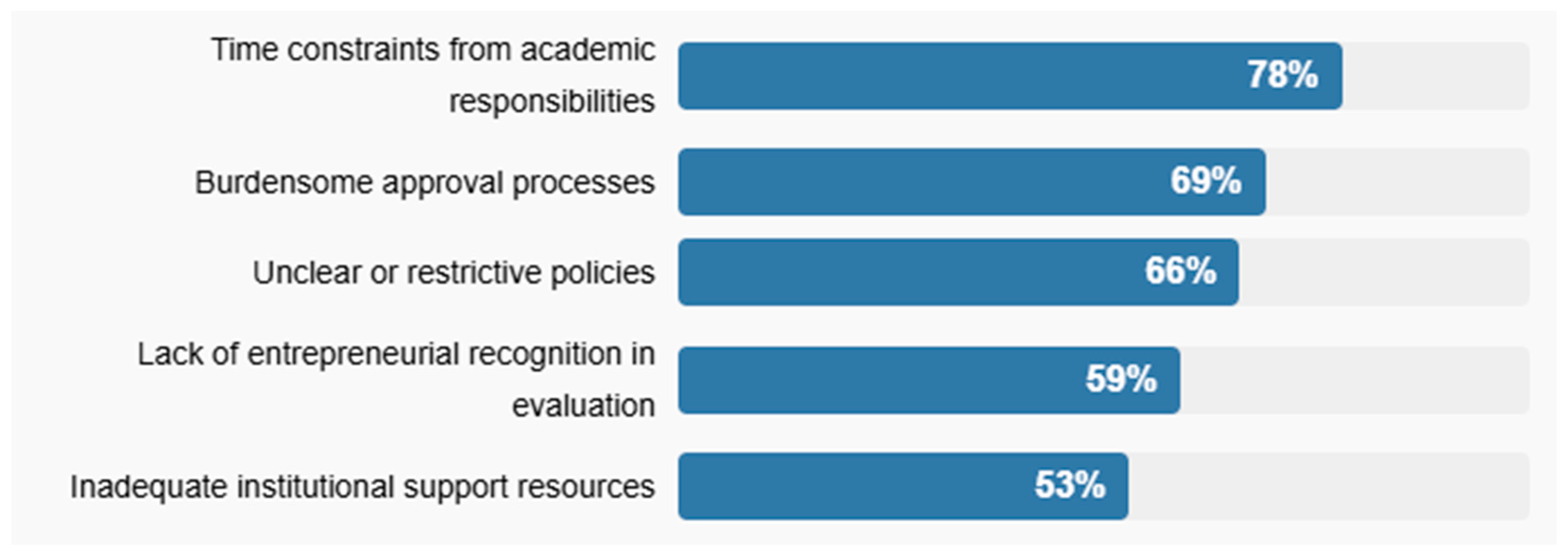

- Policy restrictions: Analysis of faculty handbooks from 24 universities reveals that approximately 40% maintain policies limiting external work to one day per week or less, often with burdensome approval processes (AAUP, 2022; policy analysis data). Linear regression analysis identified restrictive policies as a significant negative predictor of entrepreneurial engagement (β=-.34, p<.001), even when controlling for discipline and faculty characteristics.

- Recognition gaps: Survey respondents overwhelmingly reported that entrepreneurial activities received inadequate recognition in evaluation processes, with 82% indicating entrepreneurship was "minimally valued" or "not valued at all" in promotion and tenure decisions. Document analysis of promotion and tenure guidelines found that only 14% explicitly recognized entrepreneurial impact as valuable for advancement.

- Resource limitations: Only about one-quarter of institutions provide dedicated support for faculty entrepreneurship beyond technology transfer, according to surveys of research universities (Huyghe et al., 2016; ACE, 2021). Institutional investment in entrepreneurial support resources significantly predicted faculty entrepreneurial engagement (β=.28, p<.001).

- Cultural resistance: Academic culture often maintains what Veblen (1918) termed the "dichotomy between the scholarly and the practical," creating normative pressure against market engagement (Duberley et al., 2018; Abreu & Grinevich, 2013). In our interviews, 72% of faculty entrepreneurs reported experiencing explicit or implicit cultural resistance to their entrepreneurial activities.

- Knowledge gaps: Faculty typically receive minimal training in business development, marketing, or entrepreneurial skills during academic preparation (Wood, 2019; Wright et al., 2018). Survey respondents rated their preparedness for entrepreneurial activities at an average of 2.4 on a 5-point scale (SD=1.1). Path analysis revealed that entrepreneurial self-efficacy significantly mediated the relationship between business knowledge and entrepreneurial engagement (indirect effect=.17, p<.01).

- Identity concerns: Many academics experience identity conflicts when considering commercial applications of their expertise, particularly in disciplines with strong anti-commercial norms (Duberley et al., 2018; Jain et al., 2009). Among survey respondents who had never engaged in entrepreneurial activities (n=140), 42% cited concerns about "professional identity" or "academic values" as barriers. Identity concerns were significantly stronger in humanities (M=3.8, SD=0.9) than in business disciplines (M=2.3, SD=1.1), F(4,241)=16.38, p<.001, η²=.21.

- Time constraints: Heavy teaching, research, and service obligations create practical limitations on entrepreneurial capacity (Perkmann et al., 2021; Link et al., 2017). Time constraints were cited by 83% of survey respondents as a significant barrier. Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that teaching load significantly predicted entrepreneurial engagement (β=-.29, p<.001), with faculty teaching 4+ courses per term 62% less likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities than those with lighter teaching loads.

- Network limitations: Academic networks often lack connections to potential clients and partners outside academia (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015; Tartari et al., 2014). Among survey respondents, 64% cited "limited connections outside academia" as a significant barrier to entrepreneurship. Social network analysis revealed that successful faculty entrepreneurs maintained significantly more diverse networks with higher proportions of non-academic connections (45% vs. 17% for non-entrepreneurs, t(244)=11.23, p<.001, d=1.44, 95% CI [1.15, 1.73]).

- Gender disparities: Multiple studies document that women faculty face additional barriers to entrepreneurship, including network exclusion, implicit bias from potential partners, and greater work-life balance challenges (Ding et al., 2013; Murray & Graham, 2007; Pinheiro et al., 2022). The current survey found that women faculty were significantly more likely than men to report inadequate networks (74% vs. 56%, χ²=9.23, p<.01, φ=0.19) and concerns about credibility with external clients (61% vs. 38%, χ²=11.76, p<.001, φ=0.22) as barriers. While these effect sizes are small to moderate, they represent consistent patterns across multiple measures. Multivariate linear regression controlling for discipline, rank, and institution type confirmed gender as a significant predictor of entrepreneurial barriers (β=.25, p<.001).

- Racial inequities: Faculty of color report significantly greater challenges in establishing entrepreneurial ventures, including credibility questions, network limitations, and institutional skepticism (Lockett et al., 2022; Dworkin et al., 2018). In the current survey, faculty of color were more likely than white faculty to report experiencing credibility challenges (73% vs. 41%, χ²=16.42, p<.001, φ=0.26) and differential treatment by potential clients (68% vs. 35%, χ²=18.91, p<.001, φ=0.28). Logistic regression analysis revealed that faculty of color were 2.38 times more likely to experience significant entrepreneurial barriers than white faculty (95% CI [1.56, 3.64], p<.001), even when controlling for discipline, institution, and rank.

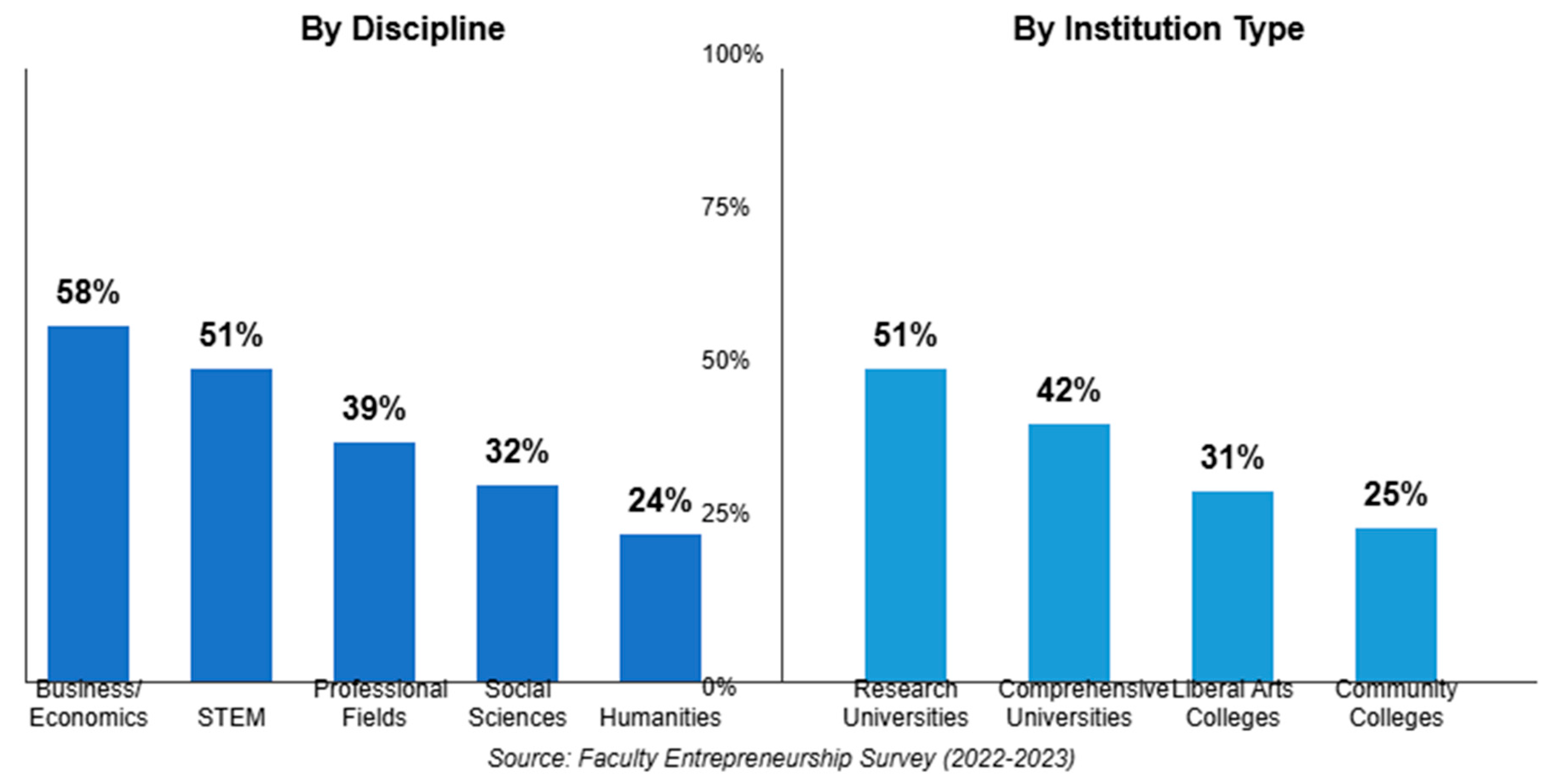

- Institutional hierarchies: Faculty at less prestigious or teaching-focused institutions report fewer entrepreneurial opportunities despite comparable expertise (Tartari et al., 2014; Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015). Survey data showed significant differences in entrepreneurial participation by Carnegie classification (F(3,242)=8.74, p<.001, η²=.10). Hierarchical linear modeling revealed that institutional prestige significantly predicted entrepreneurial opportunity (b=1.83, SE=0.37, p<.001) independent of individual faculty characteristics.

- Disciplinary differences: Humanities, arts, and some social sciences face structural disadvantages in entrepreneurial opportunity despite growing market potential (Abreu & Grinevich, 2013; Olmos-Peñuela et al., 2015). Survey data confirmed significant differences in entrepreneurial participation by discipline (F(4,241)=9.63, p<.001, η²=.14). However, our longitudinal case studies revealed that these disciplinary differences may be diminishing as digital platforms create new entrepreneurial channels for humanities and social science expertise.

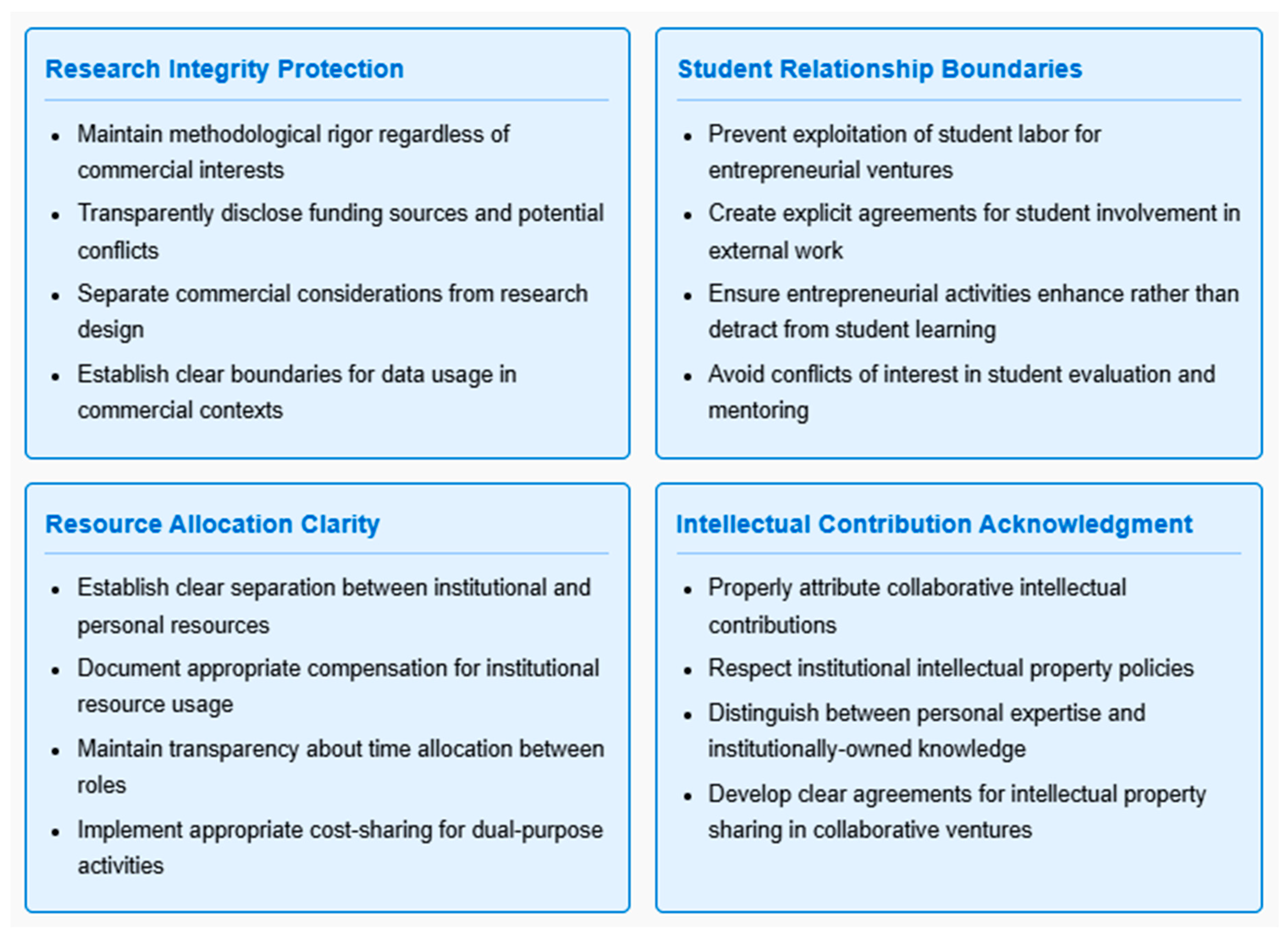

- Research integrity: Commercial interests may influence research questions, methods, or interpretation of results (Williams-Jones, 2013)

- Student relationships: Faculty may inappropriately use student labor or direct students toward entrepreneurial interests rather than educational priorities (Owen-Smith & Powell, 2004)

- Institutional resources: Boundaries between institutional and personal resource use may become blurred (Jain et al., 2009)

- Research integrity protection

- Student relationship boundaries

- Resource allocation clarity

- Intellectual contribution acknowledgment

- Public knowledge vs. private gain: When should expertise be freely shared versus commercially leveraged? (Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004)

- Academic vs. market values: How can scholarly integrity be maintained when client interests conflict with academic standards? (Washburn, 2008)

- Institutional vs. individual interests: How should benefits from faculty expertise be distributed? (Lockett et al., 2015)

- Knowledge stewards (43%): Prioritizing public good while selectively commercializing applications

- Boundary navigators (37%): Creating explicit separations between academic and commercial domains

- Value integrators (20%): Developing frameworks that harmonize academic and market values

- Transparent disclosure of commercial relationships to all stakeholders

- Formal separation of academic and commercial activities where appropriate

- Proactive identification and management of potential conflicts

- Prioritization of educational and scholarly integrity over financial gain

- Careful attention to power differentials, particularly with students

- Clearly define acceptable external activities with transparent approval processes

- Create equitable intellectual property frameworks that incentivize faculty participation

- Recognize entrepreneurial impact in promotion and tenure decisions

- Establish clear conflict of interest management protocols rather than prohibitions

- Clear procedural guidance (present at 34% of institutions)

- Streamlined approval processes (present at 29% of institutions)

- Consistent policy application across units (present at 42% of institutions)

- Regular policy review and updates (present at 37% of institutions)

- Entrepreneurial education: Structured training in business fundamentals, market assessment, and service design

- Peer learning communities: Discipline-specific groups sharing strategies and experiences

- Mentorship structures: Connecting early-stage faculty entrepreneurs with experienced peers

- Implementation support: Resources for developing business infrastructure and client acquisition systems

- Discipline-specific approaches rather than generic entrepreneurship training

- Staged development support matching faculty readiness levels

- Peer mentorship from successful faculty entrepreneurs rather than solely external consultants

- Explicit attention to equity in program design and access

- Integration with rather than separation from academic development

- Addressed both technical business skills and identity integration

- Provided ongoing support rather than one-time training

- Connected participants with successful peer mentors

- Integrated entrepreneurial development with academic career planning

- Administrative infrastructure for managing external engagements

- Legal support for contract development and negotiation

- Marketing and business development assistance

- Physical and virtual spaces for client meetings and project work

- Legal and contract support (81%)

- Business development assistance (76%)

- Administrative support for client management (72%)

- Dedicated meeting spaces (58%)

- Marketing assistance (56%)

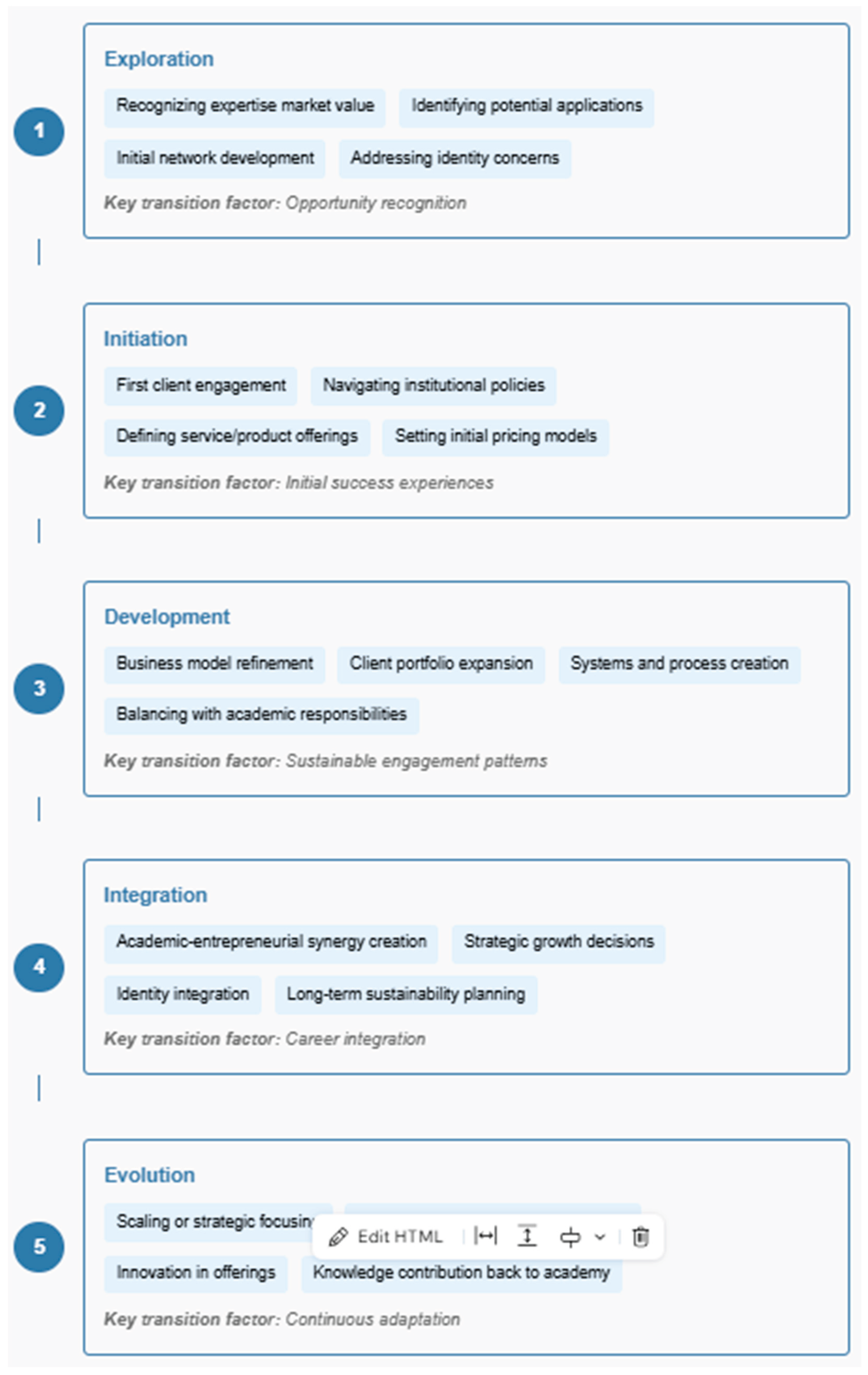

- Recognizing expertise market value

- Identifying potential applications

- Initial network development

- Addressing identity concerns

- Key transition factor: Opportunity recognition

- First client engagement

- Navigating institutional policies

- Defining service/product offerings

- Setting initial pricing models

- Key transition factor: Initial success experiences

- Business model refinement

- Client portfolio expansion

- Systems and process creation

- Balancing with academic responsibilities

- Key transition factor: Sustainable engagement patterns

- Academic-entrepreneurial synergy creation

- Strategic growth decisions

- Identity integration

- Long-term sustainability planning

- Key transition factor: Career integration

- Scaling or strategic focusing

- Potential team/business development

- Innovation in offerings

- Knowledge contribution back to academy

- Key transition factor: Continuous adaptation

- Creating a methodical framework translating historical case studies into applicable leadership principles

- Developing tiered content offerings from free articles to premium workshops

- Establishing clear agreements with her institution regarding intellectual property

- Building a systematic approach to balancing academic and entrepreneurial commitments

- Identifying specific industry pain points his research directly addressed

- Creating standardized assessment and implementation methodologies

- Involving graduate students in appropriate aspects of consulting projects

- Developing clear scope boundaries to manage time commitments

- Identifying a practice model compatible with heavy teaching responsibilities

- Leveraging institutional affiliation while maintaining clear separation

- Developing systems to minimize administrative burden

- Creating opportunities for undergraduate involvement as professional development

- Strategic alignment between academic expertise and market needs

- Clear boundary management between academic and entrepreneurial roles

- Development of systematic approaches rather than ad hoc engagements

- Intentional integration of entrepreneurial insights into academic work

- Navigation of institutional policies through persistence and demonstration of benefits

- Conducting systematic assessment of expertise marketability within specific sectors

- Developing incremental engagement strategies that manage risk and time investment

- Creating clear boundaries between academic and entrepreneurial activities

- Building complementarity between entrepreneurial work and research/teaching agendas

- Seeking institutional champions and peer support for entrepreneurial initiatives

- Proactively addressing potential ethical concerns and conflicts of interest

- Revising outdated policies that create unnecessary barriers to external engagement

- Developing explicit recognition for entrepreneurial impact in evaluation criteria

- Creating dedicated support infrastructure for faculty entrepreneurs

- Facilitating connections between faculty expertise and external opportunities

- Celebrating and showcasing successful faculty entrepreneurship

- Implementing targeted interventions to address entrepreneurial equity gaps

- Clear procedural guidance that reduces administrative burden

- Consistent application across departments and disciplines

- Explicit equity considerations in policy design and implementation

- Regular assessment and improvement of entrepreneurial support systems

- Developing funding mechanisms that incentivize knowledge application alongside discovery

- Creating regulatory frameworks that facilitate rather than impede academic-industry collaboration

- Establishing metrics that recognize entrepreneurial contributions to institutional missions

- Supporting professional development that prepares faculty for entrepreneurial opportunities

- Implementing accountability measures that address equity in entrepreneurial opportunity

- Digital transformation: Online platforms are dramatically reducing barriers to market entry for faculty entrepreneurs, creating global reach with minimal infrastructure. Survey respondents identified digital platforms as the most significant enabler of entrepreneurial activity (72%). Time series analysis of entrepreneurial engagement channels revealed a 143% increase in digital platform utilization over the three-year study period.

- Alternative credentials: The growing market for specialized professional education creates opportunities for faculty to develop focused certification programs. Faculty in the survey reported increasing demand for non-degree professional education (68%), with highest growth in technology-adjacent fields (86%) and practice-oriented disciplines (74%).

- Hybrid careers: New academic career models are emerging that explicitly integrate entrepreneurial activities alongside traditional responsibilities. Among faculty under 40 years old in the survey, 74% expressed interest in hybrid academic-entrepreneurial career paths. Institutional analysis revealed early adoption of formalized hybrid appointments at 18% of studied institutions, with planned implementation at another 32%.

- Collaborative entrepreneurship: Faculty teams increasingly form multidisciplinary ventures addressing complex challenges requiring diverse expertise. The survey found that 35% of entrepreneurial activities involved cross-disciplinary collaboration, with these ventures reporting 27% higher revenue (t(104)=3.86, p<.001, d=0.76, 95% CI [0.36, 1.15]) and greater problem-solving capacity than single-discipline ventures.

- Equity interventions: Growing awareness of structural barriers is driving more intentional approaches to increasing entrepreneurial diversity. Institutions with targeted diversity initiatives reported 42% higher entrepreneurial participation among underrepresented faculty, with particularly strong effects for women in STEM fields (53% increase, χ²=18.72, p<.001, φ=0.38) and faculty of color in humanities and social sciences (47% increase, χ²=15.83, p<.001, φ=0.35).

- While the survey sample was diverse, response rate limitations (20.5%) raise potential concerns about self-selection bias, particularly among faculty with strong opinions about entrepreneurship. Future research should employ alternative sampling strategies to capture experiences of non-respondents.

- The interview sample, while purposively selected for diversity, may not fully represent the experiences of all faculty entrepreneurs, particularly those from underrepresented groups or institutional contexts. More comprehensive sampling across institutional types and demographic categories would strengthen future studies.

- Longitudinal data on entrepreneurial outcomes remains limited, particularly regarding long-term career impacts and sustainability. Extended longitudinal tracking beyond our three-year window would provide valuable insights into entrepreneurial career trajectories.

- Comparative international analysis of faculty entrepreneurship across different higher education systems requires further development. While our sample included international institutions, more systematic cross-national comparison would illuminate how different higher education systems shape entrepreneurial opportunities.

- Systematic evaluation of institutional support programs is still emerging, with limited causal evidence on program effectiveness. Quasi-experimental designs evaluating specific interventions would strengthen the evidence base for institutional investments.

- Our theoretical integration, while multifaceted, could be further developed through more explicit testing of propositions derived from core theories. The relationships between academic capitalism, knowledge spillover theory, institutional theory, and identity work could be more systematically explored.

- While we addressed pandemic effects, our data collection period (2020-2023) coincided with exceptional circumstances that may limit generalizability. Follow-up studies in post-pandemic contexts would provide valuable comparative insights.

- More comprehensive demographic and institutional sampling in faculty entrepreneurship studies

- Longitudinal tracking of entrepreneurial faculty careers across multiple outcomes

- Comparative analysis of international contexts and policy environments

- Rigorous evaluation of institutional interventions and support programs

- Investigation of effective approaches to addressing equity gaps in entrepreneurial participation

- Development of more integrated theoretical models of faculty entrepreneurship

- Exploration of how emerging technologies and work models reshape faculty entrepreneurial opportunities

- Aligned with rather than separate from academic missions and values

- Supported by institutional policies and resources that facilitate rather than impede engagement

- Designed to enhance rather than detract from core academic responsibilities

- Implemented with explicit attention to equity and inclusion

- Managed with clear ethical frameworks and conflict mitigation strategies

Conflicts of Interest and Informed Consent Declarations

Appendix A. Research Instruments

- 1.

- Have you engaged in any paid activities outside your primary academic appointment in the past three years?

- o

- Yes

- o

- No [Skip to Section 4]

- 2.

- Which of the following entrepreneurial activities have you engaged in during the past three years? (Select all that apply)

- o

- Consulting

- o

- Paid speaking engagements

- o

- Training/workshop facilitation

- o

- Expert testimony

- o

- Content creation (books, courses, educational materials)

- o

- Digital content (online courses, apps, software)

- o

- Product development

- o

- Company/startup founding

- o

- Advisory board service

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 3.

- Approximately how many hours per month do you typically devote to these entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Less than 5 hours

- o

- 5-10 hours

- o

- 11-20 hours

- o

- 21-40 hours

- o

- More than 40 hours

- 4.

- Approximately what percentage of your total annual income comes from these entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Less than 5%

- o

- 5-10%

- o

- 11-25%

- o

- 26-50%

- o

- More than 50%

- 5.

- If comfortable sharing, please indicate your approximate annual income from entrepreneurial activities:

- o

- Under $10,000

- o

- $10,000-$30,000

- o

- $30,001-$75,000

- o

- $75,001-$150,000

- o

- Over $150,000

- o

- Prefer not to answer

- 6.

- To what extent have your entrepreneurial activities impacted the following aspects of your academic work? (Scale: Very negatively, Somewhat negatively, No impact, Somewhat positively, Very positively)

- o

- Research productivity

- o

- Teaching effectiveness

- o

- Service contributions

- o

- Overall job satisfaction

- o

- Advancement/promotion prospects

- o

- Collegial relationships

- o

- Work-life balance

- 7.

- How many peer-reviewed publications have you produced in the past two years?

- o

- 0

- o

- 1-2

- o

- 3-5

- o

- 6-10

- o

- More than 10

- 8.

- Has your entrepreneurial work directly contributed to any of the following? (Select all that apply)

- o

- New research questions or directions

- o

- Access to research sites or data

- o

- Securing additional research funding

- o

- Student internship or employment opportunities

- o

- Course content or teaching materials

- o

- New institutional partnerships

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 9.

- Please rate your agreement with the following statements: (Scale: Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Agree, Strongly agree)

- o

- My entrepreneurial activities enhance my academic credibility

- o

- My entrepreneurial work provides valuable real-world examples for teaching

- o

- My entrepreneurial activities create valuable networking opportunities

- o

- My entrepreneurial activities help keep my research relevant to real-world problems

- o

- My entrepreneurial work is intellectually stimulating

- o

- My entrepreneurial activities create financial stability

- o

- My entrepreneurial work increases my overall career satisfaction

- 10.

- Have you encountered any of the following institutional challenges or barriers to entrepreneurial activities? (Select all that apply)

- o

- Restrictive institutional policies

- o

- Burdensome approval processes

- o

- Unclear intellectual property provisions

- o

- Limited institutional support

- o

- Lack of recognition in promotion/tenure

- o

- Negative perceptions from colleagues

- o

- Time constraints from academic responsibilities

- o

- Conflict of interest concerns

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 11.

- Have you encountered any of the following personal challenges in pursuing entrepreneurial activities? (Select all that apply)

- o

- Limited business knowledge/skills

- o

- Network limitations

- o

- Difficulty identifying market opportunities

- o

- Concerns about maintaining academic identity

- o

- Concerns about academic-market value conflicts

- o

- Time management challenges

- o

- Difficulty securing initial clients/opportunities

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 12.

- On a scale from 1 (completely unprepared) to 5 (extremely well prepared), how prepared did you feel for engaging in entrepreneurial activities based on your academic training?

- o

- 1 (Completely unprepared)

- o

- 2

- o

- 3

- o

- 4

- o

- 5 (Extremely well prepared)

- 13.

- Have you experienced differential treatment or barriers based on any personal characteristics? (Select all that apply)

- o

- Gender

- o

- Race/ethnicity

- o

- Age

- o

- Institution type/prestige

- o

- Discipline

- o

- Academic rank/status

- o

- None experienced

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 14.

- Please rate how supportive the following entities have been of your entrepreneurial activities: (Scale: Very unsupportive, Somewhat unsupportive, Neutral, Somewhat supportive, Very supportive, N/A)

- o

- Department chair

- o

- Dean/college leadership

- o

- University administration

- o

- Departmental colleagues

- o

- Institutional policies

- o

- Promotion/tenure committee

- 15.

- Does your institution have explicit policies governing faculty entrepreneurship or outside activities?

- o

- Yes

- o

- No

- o

- Unsure

- 16.

- If yes, how would you characterize these policies? (Select all that apply)

- o

- Clear and transparent

- o

- Overly restrictive

- o

- Supportive of entrepreneurship

- o

- Focused primarily on risk management

- o

- Outdated or impractical

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 17.

- Does your institution limit the amount of time faculty can spend on outside activities?

- o

- Yes, limited to one day per week or less

- o

- Yes, but more than one day per week

- o

- No formal time limits

- o

- Unsure

- 18.

- Does your institution provide any of the following resources to support faculty entrepreneurship? (Select all that apply)

- o

- Entrepreneurship training

- o

- Business development support

- o

- Legal/contract assistance

- o

- Administrative support

- o

- Mentoring programs

- o

- Dedicated physical space

- o

- Funding/grants for entrepreneurial activities

- o

- None of the above

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 19.

- Does your institution recognize entrepreneurial activities in any of the following ways? (Select all that apply)

- o

- Considered in promotion/tenure decisions

- o

- Included in annual evaluation

- o

- Public recognition or awards

- o

- Course release or workload adjustment

- o

- None of the above

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 20.

- How would you rate your institution's overall support for faculty entrepreneurship?

- o

- Highly supportive

- o

- Somewhat supportive

- o

- Neutral

- o

- Somewhat unsupportive

- o

- Highly unsupportive

- 21.

- How likely are you to engage in entrepreneurial activities in the next three years?

- o

- Very unlikely

- o

- Somewhat unlikely

- o

- Neutral

- o

- Somewhat likely

- o

- Very likely

- 22.

- Which of the following would most help you develop or expand entrepreneurial activities? (Select up to three)

- o

- More supportive institutional policies

- o

- Recognition in promotion/tenure

- o

- Training in business skills

- o

- Entrepreneurial mentoring

- o

- Networking opportunities

- o

- Administrative/legal support

- o

- Seed funding

- o

- Time/workload adjustments

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 23.

- What advice would you give to faculty interested in developing entrepreneurial activities? (Open-ended)

- 24.

- What changes would you recommend to institutions seeking to better support faculty entrepreneurship? (Open-ended)

- 25.

- What is your current academic rank?

- o

- Assistant Professor

- o

- Associate Professor

- o

- Full Professor

- o

- Lecturer/Instructor

- o

- Clinical/Research Faculty

- o

- Adjunct Faculty

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 26.

- What is your tenure status?

- o

- Tenured

- o

- Tenure-track (not yet tenured)

- o

- Non-tenure track

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 27.

- How many years have you been in a faculty position?

- o

- Less than 5 years

- o

- 5-10 years

- o

- 11-15 years

- o

- 16-20 years

- o

- More than 20 years

- 28.

- In which disciplinary area is your primary appointment?

- o

- Arts and Humanities

- o

- Social Sciences

- o

- Natural Sciences

- o

- Engineering/Computer Science

- o

- Business/Economics

- o

- Health Sciences

- o

- Education

- o

- Law

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 29.

- What is your institution type?

- o

- Research university (R1/R2)

- o

- Comprehensive university

- o

- Liberal arts college

- o

- Community college

- o

- For-profit institution

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- 30.

- What is your gender identity?

- o

- Woman

- o

- Man

- o

- Non-binary/third gender

- o

- Prefer to self-describe: _________

- o

- Prefer not to say

- 31.

- What is your race/ethnicity? (Select all that apply)

- o

- White/Caucasian

- o

- Black/African American

- o

- Hispanic/Latino

- o

- Asian/Pacific Islander

- o

- Native American/Alaska Native

- o

- Middle Eastern/North African

- o

- Multiracial

- o

- Other (please specify): _________

- o

- Prefer not to say

- 32.

- What is your age range?

- o

- Under 35

- o

- 35-44

- o

- 45-54

- o

- 55-64

- o

- 65 or older

- o

- Prefer not to say

- 33.

- Is there anything else you would like to share about your experiences with faculty entrepreneurship? (Open-ended)

- 34.

- Would you be willing to participate in a follow-up interview about your experiences with faculty entrepreneurship?

- o

- Yes (please provide email): _________

- o

- No

- 1.

- Could you start by telling me about your current academic position and main areas of expertise?

- 2.

- What entrepreneurial activities have you engaged in alongside your academic work?

- o

- Probe: When and how did you first become involved in these activities?

- o

- Probe: How has your entrepreneurial work evolved over time?

- 3.

- Could you walk me through how you initially identified market opportunities for your expertise?

- o

- Probe: What signals indicated that your knowledge had commercial value?

- o

- Probe: How did you validate this market potential?

- 4.

- Approximately what percentage of your professional time is devoted to entrepreneurial activities, and how has this changed over time?

- 5.

- Could you describe the process of establishing your entrepreneurial venture(s)?

- o

- Probe: What formal structures or business models have you used?

- o

- Probe: How did you acquire necessary business skills and knowledge?

- 6.

- How do you typically find or attract clients/opportunities?

- o

- Probe: What marketing or business development approaches have been most effective?

- o

- Probe: How have professional networks influenced your entrepreneurial opportunities?

- 7.

- What has been most challenging about developing entrepreneurial activities alongside academic responsibilities?

- o

- Probe: How have you addressed these challenges?

- 8.

- Have you experienced any identity conflicts or tensions between your academic and entrepreneurial roles?

- o

- Probe: How have you reconciled or managed these tensions?

- 9.

- How would you characterize your institution's approach to faculty entrepreneurship?

- o

- Probe: What specific policies or procedures govern your outside activities?

- o

- Probe: How transparent and navigable are these policies?

- 10.

- How did you navigate institutional approval processes for your entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Probe: What challenges did you encounter?

- o

- Probe: What institutional resources were most helpful?

- 11.

- How have departmental colleagues and leadership responded to your entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Probe: Have you experienced support or resistance?

- o

- Probe: Has entrepreneurship affected your collegial relationships?

- 12.

- How are entrepreneurial activities viewed in promotion, tenure, or evaluation processes at your institution?

- o

- Probe: Have your entrepreneurial activities been recognized or valued in these processes?

- 13.

- How have your entrepreneurial activities affected your academic work?

- o

- Probe: Impact on research productivity or direction?

- o

- Probe: Impact on teaching approaches or content?

- o

- Probe: Impact on institutional service or engagement?

- 14.

- What financial outcomes have resulted from your entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Probe: How significant is this income relative to your academic salary?

- o

- Probe: How has this affected your financial security or career decisions?

- 15.

- What non-financial benefits have you experienced from entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Probe: Professional networks or opportunities?

- o

- Probe: Skill development or personal growth?

- o

- Probe: Career satisfaction or future options?

- 16.

- Have your entrepreneurial activities created opportunities for student involvement or professional development?

- o

- Probe: How have students participated in or benefited from your entrepreneurial work?

- 17.

- Have you observed or experienced differences in entrepreneurial opportunities or support based on gender, race, or other personal characteristics?

- o

- Probe: How have these factors influenced your own entrepreneurial journey?

- 18.

- What advantages or disadvantages related to entrepreneurship have you observed based on academic discipline, institution type, or career stage?

- 19.

- What systemic barriers limit faculty entrepreneurship, and how might these be addressed?

- 20.

- What ethical considerations or potential conflicts have you navigated in your entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Probe: How have you managed boundaries between academic and commercial interests?

- o

- Probe: How have you addressed potential conflicts of interest?

- 21.

- How do you balance public knowledge dissemination with commercial application of your expertise?

- o

- Probe: Are there tensions between these priorities?

- o

- Probe: How do you determine what to commercialize versus share freely?

- 22.

- What advice would you give to faculty interested in developing entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Probe: What do you wish you had known when starting?

- o

- Probe: What common pitfalls should they avoid?

- 23.

- What changes would you recommend to institutional policies or practices to better support faculty entrepreneurship?

- 24.

- How do you see faculty entrepreneurship evolving in the future of higher education?

- o

- Probe: What trends or opportunities do you anticipate?

- o

- Probe: How might academic career paths incorporate entrepreneurship?

- 25.

- Is there anything else about your experiences with faculty entrepreneurship that you'd like to share that we haven't covered?

- Disciplines (2 STEM, 2 business/economics, 2 social sciences, 2 humanities/arts)

- Institution types (4 research universities, 2 comprehensive universities, 2 liberal arts/teaching-focused)

- Career stages (3 assistant professors, 3 associate professors, 2 full professors)

- Demographics (4 women, 4 men; 3 faculty of color, 5 white faculty)

- Entrepreneurial approaches (representing different models of faculty entrepreneurship)

- Comprehensive baseline interview using extended semi-structured protocol

- Collection of entrepreneurial artifacts (websites, marketing materials, sample contracts)

- Documentation of business structure and model

- Baseline financial and activity metrics

- 30-45 minute semi-structured interview

- Monthly activity log review

- Updated metrics collection

- Documentation of critical incidents

- 90-minute comprehensive interview

- Updated artifact collection

- Comparative analysis of metrics

- Institutional context update

- Time allocation across academic and entrepreneurial activities

- Client/project acquisition and development

- Revenue generation

- Academic outputs related to entrepreneurial work

- Challenges encountered

- Institutional interactions

- Critical incidents or decision points

- 1.

- Activity and Development Updates

- o

- What entrepreneurial activities have you engaged in since our last discussion?

- o

- What changes have occurred in your business model or approach?

- o

- What opportunities or challenges have emerged?

- 2.

- Client/Market Engagement

- o

- How have client relationships or market engagement evolved?

- o

- What business development activities have you undertaken?

- o

- What feedback have you received from clients or partners?

- 3.

- Institutional Interface

- o

- What interactions have you had with your institution regarding entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- Have any policy or procedural issues arisen?

- o

- How have colleagues responded to your entrepreneurial work?

- 4.

- Academic Integration

- o

- How have entrepreneurial activities integrated with your academic responsibilities?

- o

- What impacts have you observed on research, teaching, or service?

- o

- Have any new synergies or conflicts emerged?

- 5.

- Financial and Resource Considerations

- o

- How have financial outcomes evolved?

- o

- What resource challenges or needs have you encountered?

- o

- What investments have you made in your entrepreneurial activities?

- 6.

- Critical Reflection

- o

- What has been most surprising or challenging in this quarter?

- o

- What strategies have been most effective?

- o

- What would you do differently if starting now?

- 7.

- Next Steps

- o

- What are your entrepreneurial priorities for the next quarter?

- o

- What specific challenges do you anticipate?

- o

- What support or resources would be most helpful?

- 1.

- Business Evolution

- o

- How has your entrepreneurial venture evolved over the past year?

- o

- What significant pivots or strategic changes have you made?

- o

- How has your understanding of the market changed?

- 2.

- Academic Career Integration

- o

- How have entrepreneurial activities affected your academic career trajectory?

- o

- What synergies or conflicts have emerged between entrepreneurial and academic work?

- o

- How has entrepreneurship influenced your professional identity?

- 3.

- Institutional Relationship

- o

- How has your relationship with the institution evolved regarding entrepreneurial activities?

- o

- What policy changes or interpretations have affected your work?

- o

- How has entrepreneurship affected departmental relationships or standing?

- 4.

- Financial and Impact Assessment

- o

- How significant has entrepreneurial income been relative to academic salary?

- o

- What non-financial impacts has entrepreneurship had on your career?

- o

- How has entrepreneurship affected your long-term career planning?

- 5.

- Knowledge and Skill Development

- o

- What new entrepreneurial skills or knowledge have you developed?

- o

- How has entrepreneurial experience informed academic expertise?

- o

- What learning resources or supports have been most valuable?

- 6.

- Equity and Access Reflections

- o

- What advantages or barriers related to personal characteristics have you observed?

- o

- How have institutional factors affected entrepreneurial access or success?

- o

- What systemic issues have become more apparent through your experience?

- 7.

- Future Outlook

- o

- How do you see your entrepreneurial activities evolving in the coming year?

- o

- What tensions or challenges do you anticipate addressing?

- o

- What institutional changes would most support your entrepreneurial work?

- Longitudinal coding of interviews and activity logs

- Trend analysis of quantitative metrics

- Critical incident analysis

- Cross-case comparison

- Theoretical memo development

- Annual comparative case reports

- Confidentiality protections through pseudonyms and masked institutional identifiers

- Secure data storage with encryption

- Participant review of case documentation

- Clear guidelines for reporting potentially sensitive information

- Option to withdraw specific data points while maintaining case integrity

- Faculty handbooks

- Outside activity policies

- Conflict of interest policies

- Intellectual property policies

- Consulting policies

- Revenue sharing policies

- Promotion and tenure guidelines

- Entrepreneurship support program documentation

- 1.

- Policy Restrictiveness

- o

- Time limitations on outside activities

- o

- Approval process requirements

- o

- Activity exclusions or prohibitions

- o

- Compensation restrictions

- o

- Institutional resource use limitations

- 2.

- Entrepreneurial Support Elements

- o

- Explicit encouragement of knowledge application

- o

- Recognition in evaluation criteria

- o

- Support resources or programs

- o

- Intellectual property accommodations

- o

- Revenue sharing provisions

- 3.

- Procedural Elements

- o

- Disclosure requirements

- o

- Approval processes

- o

- Monitoring mechanisms

- o

- Compliance enforcement

- o

- Appeal procedures

- 4.

- Policy Clarity and Accessibility

- o

- Definition clarity

- o

- Language accessibility

- o

- Process transparency

- o

- Information availability

- o

- Guidance resources

- 5.

- Equity Considerations

- o

- Differential impact analysis

- o

- Explicit equity provisions

- o

- Accommodations for different disciplines

- o

- Support for underrepresented faculty

- o

- Bias mitigation approaches

- 6.

- Conflict Management Approaches

- o

- Conflict of interest definitions

- o

- Management versus prohibition orientation

- o

- Student protection provisions

- o

- Institutional reputation safeguards

- o

- Academic integrity protections

- 7.

- Knowledge Ownership and Commercialization

- o

- Intellectual property assignment

- o

- Course material ownership

- o

- Software/digital content provisions

- o

- Revenue sharing formulas

- o

- Traditional vs. digital knowledge products

- Initial coding of all policies using the framework

- Secondary targeted analysis of specific policy domains

- Comparative analysis across institutional types

- Identification of policy archetypes and approaches

- Assessment of potential equity impacts

- Development of best practice recommendations

| Policy Type | Primary Characteristics | Underlying Philosophy | Examples |

| Restrictive | Tight limits, extensive oversight, prohibition orientation | Protection of institutional interests and academic duties | [Institutions identified during analysis] |

| Permissive | Minimal restrictions, limited oversight, high autonomy | Maximizing knowledge application and faculty autonomy | [Institutions identified during analysis] |

| Managed Engagement | Clear parameters, streamlined processes, supported autonomy | Balancing engagement encouragement with reasonable oversight | [Institutions identified during analysis] |

| Discipline-Specific | Varied approaches by field, contextualized guidelines | Recognition of disciplinary differences in entrepreneurial forms | [Institutions identified during analysis] |

| Equity-Focused | Explicit attention to access barriers, targeted support | Addressing structural inequities in entrepreneurial opportunity | [Institutions identified during analysis] |

- Faculty entrepreneurship participation rates

- Demographic representation in entrepreneurial activities

- Faculty satisfaction with policy clarity and fairness

- Administrative burden metrics

- Policy compliance rates

- Conflict incident frequency

- Institutional benefit capture

References

- Abreu, M., & Grinevich, V. The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Research Policy 2013, 42, 408–422.

- AACSB. (2020). Faculty engagement and impact survey. Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business.

- AAUP. (2022). Annual report on the economic status of the profession. American Association of University Professors.

- Aguinis, H., Shapiro, D. L., Antonacopoulou, E. P., & Cummings, T. G. Scholarly impact: A pluralist conceptualization. Academy of Management Learning & Education 2014, 13, 623–639.

- Ankrah, S., & Al-Tabbaa, O. Universities-industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management 2015, 31, 387–408.

- Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. The theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Studies 2007, 44, 1242–1254.

- Azoulay, P., Ganguli, I., & Graff Zivin, J. The mobility of elite life scientists: Professional and personal determinants. Research Policy 2017, 46, 573–590.

- Beenen, G., & Goodman, J. S. Organizational learning in business schools: Connecting academic and professional concerns. Journal of Management Education 2014, 38, 336–363.

- Bothwell, E. The campus consultants: How academics are becoming key industry advisers. Times Higher Education 2021, June 10.

- Brown, W. (2015). Undoing the demos: Neoliberalism's stealth revolution. MIT Press.

- Clark, B. R. (2004). Sustaining change in universities: Continuities in case studies and concepts. Open University Press.

- Cohen, W. M., Nelson, R. R., & Walsh, J. P. Links and impacts: The influence of public research on industrial R&D. Management Science 2020, 48, 1–23.

- Czarnitzki, D., Grimpe, C., & Toole, A. A. Delay and secrecy: Does industry sponsorship jeopardize disclosure of academic research? Industrial and Corporate Change, 2015, 24, 251–279.

- D'Este, P., & Perkmann, M. Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. Journal of Technology Transfer 2011, 36, 316–339.

- Deem, R. , Hillyard, S., & Reed, M. (2007). Knowledge, higher education, and the new managerialism: The changing management of UK universities. Oxford University Press.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 1983, 48, 147–160.

- Ding, W. W., Murray, F., & Stuart, T. E. From bench to board: Gender differences in university scientists' participation in corporate scientific advisory boards. Academy of Management Journal 2013, 56, 1443–1464.

- Duberley, J., Cohen, L., & Leeson, E. Entrepreneurial academics: Developing scientific careers in changing university settings. Higher Education Quarterly 2018, 61, 479–497.

- Dworkin, T. M., Maurer, V., & Schipani, C. A. Career mentoring for women: New horizons/expanded methods. Business Horizons 2018, 55, 363–372.

- Etzkowitz, H. Innovation lodestar: The entrepreneurial university in a stellar knowledge firmament. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2017, 123, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, R., Jourdan, J., & Perkmann, M. Social valuation across multiple audiences: The interplay of ability and identity judgments. Academy of Management Journal 2018, 61, 2230–2264.

- Giroux, H. A. (2014). Neoliberalism's war on higher education. Haymarket Books.

- Green, L. W., Ottoson, J. M., García, C., & Hiatt, R. A. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annual Review of Public Health 2014, 30, 151–174.

- Hazelkorn, E. (2015). Rankings and the reshaping of higher education: The battle for world-class excellence. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huyghe, A., Knockaert, M., Piva, E., & Wright, M. Are researchers deliberately bypassing the technology transfer office? An analysis of TTO awareness. Small Business Economics 2016, 47, 589–607.

- Ibarra, H., & Barbulescu, R. Identity as narrative: Prevalence, effectiveness, and consequences of narrative identity work in macro work role transitions. Academy of Management Review 2010, 35, 135–154.

- Jain, S., George, G., & Maltarich, M. Academics or entrepreneurs? Investigating role identity modification of university scientists involved in commercialization activity. Research Policy 2009, 38, 922–935.

- Kezar, A. , DePaola, T., & Scott, D. T. (2019). The gig academy: Mapping labor in the neoliberal university. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Levin, M. , & Greenwood, D. (2016). Creating a new public university and reviving democracy. Berghahn Books.

- Link, A. N. , Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2017). The Chicago handbook of university technology transfer and academic entrepreneurship. University of Chicago Press.

- Lockett, A., Wright, M., & Wild, A. The institutionalization of third stream activities in UK higher education: The role of discourse and metrics. British Journal of Management 2015, 26, 78–92.

- Lockett, N., Qureshi, F., & McElwee, G. Barriers to entrepreneurship for underrepresented groups in higher education. International Small Business Journal 2022, 40, 377–397.

- Mitchell, M. , Leachman, M., & Masterson, K. (2019). State higher education funding cuts have pushed costs to students, worsened inequality. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- Morris, Z. S., Wooding, S., & Grant, J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2011, 104, 510–520.

- Murray, F. , & Graham, L. Buying science and selling science: Gender differences in the market for commercial science. Industrial and Corporate Change 2007, 16, 657–689. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education 2017, 16, 277–299.

- NSF. (2022). Higher education research and development survey. National Science Foundation.

- O'Kane, C., Mangematin, V., Zhang, J. A., & Cunningham, J. A. How university-based principal investigators shape a hybrid role identity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2020, 159, 120179.

- Olmos-Peñuela, J., Benneworth, P., & Castro-Martínez, E. Are sciences essential and humanities elective? Disentangling competing claims for humanities' research public value. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 2015, 14, 61–78.

- O'Shea, R. P., Allen, T. J., Chevalier, A., & Roche, F. Universities and technology transfer: A review of academic entrepreneurship literature. Irish Journal of Management 2014, 35, 29–48.

- Owen-Smith, J., & Powell, W. W. Knowledge networks as channels and conduits: The effects of spillovers in the Boston biotechnology community. Organization Science 2004, 15, 5–21.

- Perkmann, M., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., Autio, E., Broström, A., D'Este, P., ... & Sobrero, M. Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Research Policy 2013, 42, 423–442.

- Perkmann, M., Salandra, R., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., & Hughes, A. Academic engagement: A review of the literature 2011-2019. Research Policy 2021, 50, 104114.

- Pinheiro, R., Langa, P. V., & Pausits, A. The institutionalization of universities' third mission: Introduction to the special issue. European Journal of Higher Education 2022, 5, 227–232.

- Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Siegel, D. S. , & Wright, M. (2015). Academic entrepreneurship: Time for a rethink? British Journal of Management, 26, 582-595.

- Slaughter, S. , & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy: Markets, state, and higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Smith, K. N., Valentino, L., & Donoghue, C. Faculty survey response rates: Challenges and innovative strategies. New Directions for Institutional Research 2019, 2019, 9–19.

- Tartari, V., & Breschi, S. Set them free: Scientists' evaluations of the benefits and costs of university–industry research collaboration. Industrial and Corporate Change 2012, 21, 1117–1147.

- Tartari, V., Perkmann, M., & Salter, A. In good company: The influence of peers on industry engagement by academic scientists. Research Policy 2014, 43, 1189–1203.

- UK Innovation Survey. (2021). Faculty entrepreneurship and engagement report. Enterprise Research Centre.

- University of Michigan. (2022). Faculty handbook: Outside professional activities. Office of the Provost.

- University of Pennsylvania. (2021). Faculty ventures initiative: Annual report. Office of the Vice Provost for Research.

- University of Toronto. (2022). Entrepreneurship hub: Faculty programming overview. Office of Entrepreneurship.

- Veblen, T. (1918). The higher learning in America. B. W. Huebsch.

- Washburn, J. (2008). University Inc.: The corporate corruption of higher education. Basic Books.

- Weller, M. (2018). The digital scholar: How technology is transforming scholarly practice. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Williams-Jones, B. Beyond a pejorative understanding of conflict of interest. The American Journal of Bioethics 2013, 11, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, M. S. Entrepreneurial faculty and academic identity: A faculty perspective. Academy of Management Perspectives 2019, 33, 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M., Siegel, D. S., & Mustar, P. An emerging ecosystem for student start-ups. Journal of Technology Transfer 2018, 42, 909–922.

| Concept | Primary Focus | Institutional Involvement | Typical Activities |

| Faculty Entrepreneurship | Application of faculty expertise | Variable, often limited | Consulting, speaking, content creation |

| Technology Transfer | Commercialization of research outputs | High, often led by institution | Patents, licensing, spinoff companies |

| Academic Capitalism | Institutional market behaviors | High, institutionally driven | Research commercialization, industry partnerships |

| Knowledge Exchange | Bidirectional knowledge flows | Moderate to high | Collaborative projects, community engagement |

| Policy Approach | Characteristics | Benefits | Limitations |

| Restrictive | Tight time limits, extensive approval processes, default skepticism | Clear boundaries, minimal conflicts | Discourages engagement, drives covert activity |

| Permissive | Minimal restrictions, limited oversight, high autonomy | Encourages entrepreneurship, reduces barriers | Potential for conflicts, institutional risk |

| Managed Engagement | Clear parameters, streamlined processes, supported autonomy | Balances engagement and oversight, clarifies expectations | Requires administrative infrastructure, ongoing monitoring |

| Assessment Dimension | Key Questions to Consider |

| Expertise Marketability | - Does your expertise address specific external needs? - Can you articulate clear value propositions? - Is there evidence of market demand? |

| Personal Readiness | - Do you have capacity alongside academic responsibilities? - Are you comfortable with business development activities? - How will entrepreneurship affect work-life balance? |

| Institutional Context | - What policies govern outside activities? - How will entrepreneurship affect promotion/tenure? - What support resources are available? |

| Complementarity | - How will entrepreneurial work enhance research/teaching? - Can activities create student opportunities? - Will activities build valuable networks? |

| Ethical Alignment | - Can you manage potential conflicts of interest? - How will you maintain academic integrity? - Are proposed activities aligned with institutional mission? |

| Dimension. | Key Indicators | Assessment Questions |

| Policy Environment | Clarity, flexibility, support orientation | - Do policies explicitly support knowledge application? - Are approval processes streamlined and transparent? - Do policies address diverse entrepreneurial forms? |

| Recognition Systems | Evaluation criteria, advancement processes | - Do P&T guidelines recognize entrepreneurial impact? - Are entrepreneurial activities valued in annual reviews? - Is entrepreneurial mentoring rewarded as service? |

| Support Infrastructure | Resources, programs, administrative support | - Are entrepreneurial development programs available? - Is specialized support provided for different disciplines? - Are administrative resources allocated to support entrepreneurship? |

| Cultural Factors | Leadership messaging, success celebration, norms | - Do leaders actively promote knowledge application? - Are entrepreneurial successes celebrated? - Is entrepreneurship respected across disciplines? |

| Equity Systems | Access initiatives, barrier reduction, monitoring | - Are entrepreneurial barriers for underrepresented faculty addressed? - Are support resources equitably distributed? - Is demographic participation monitored and improved? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).