Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

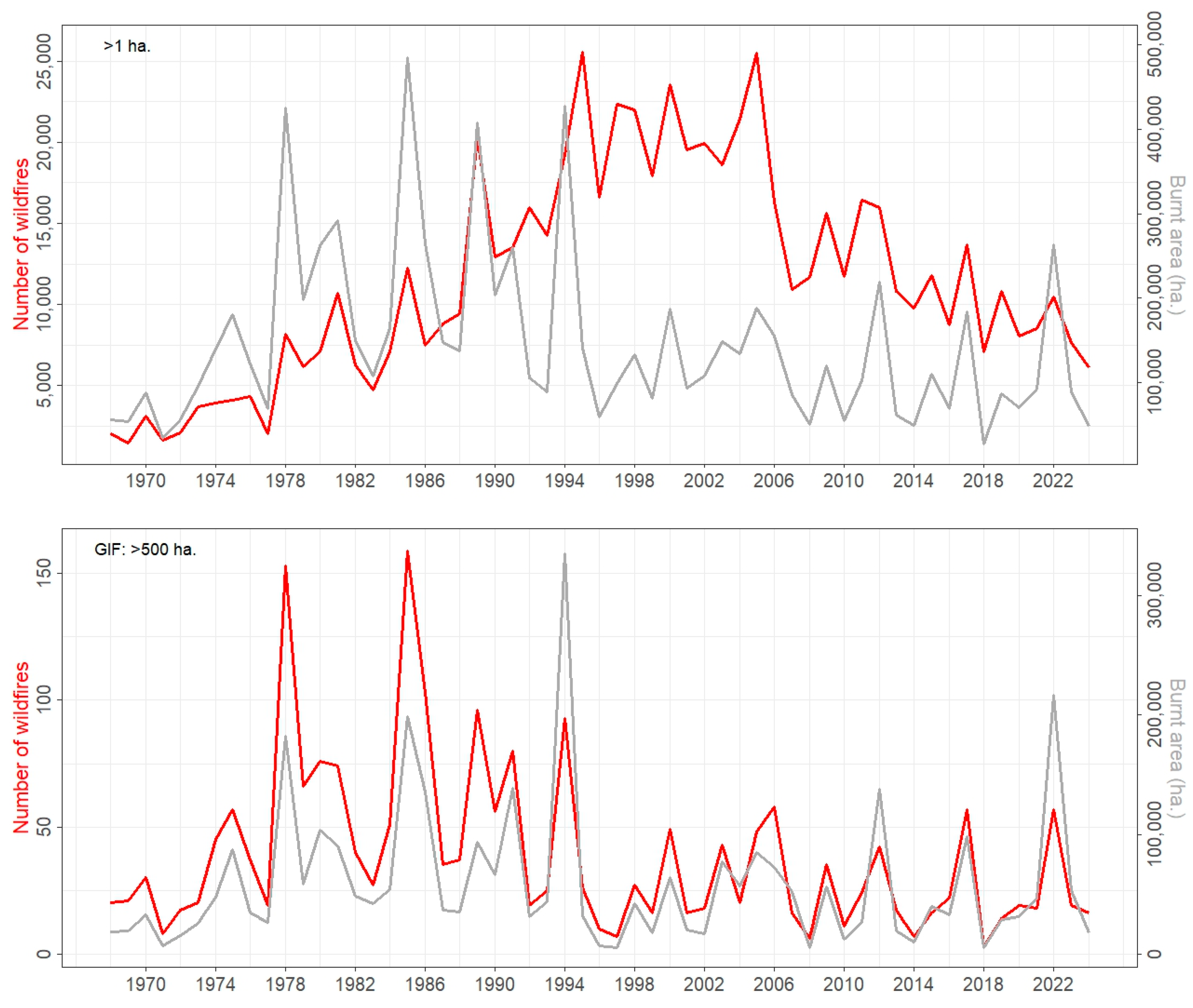

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

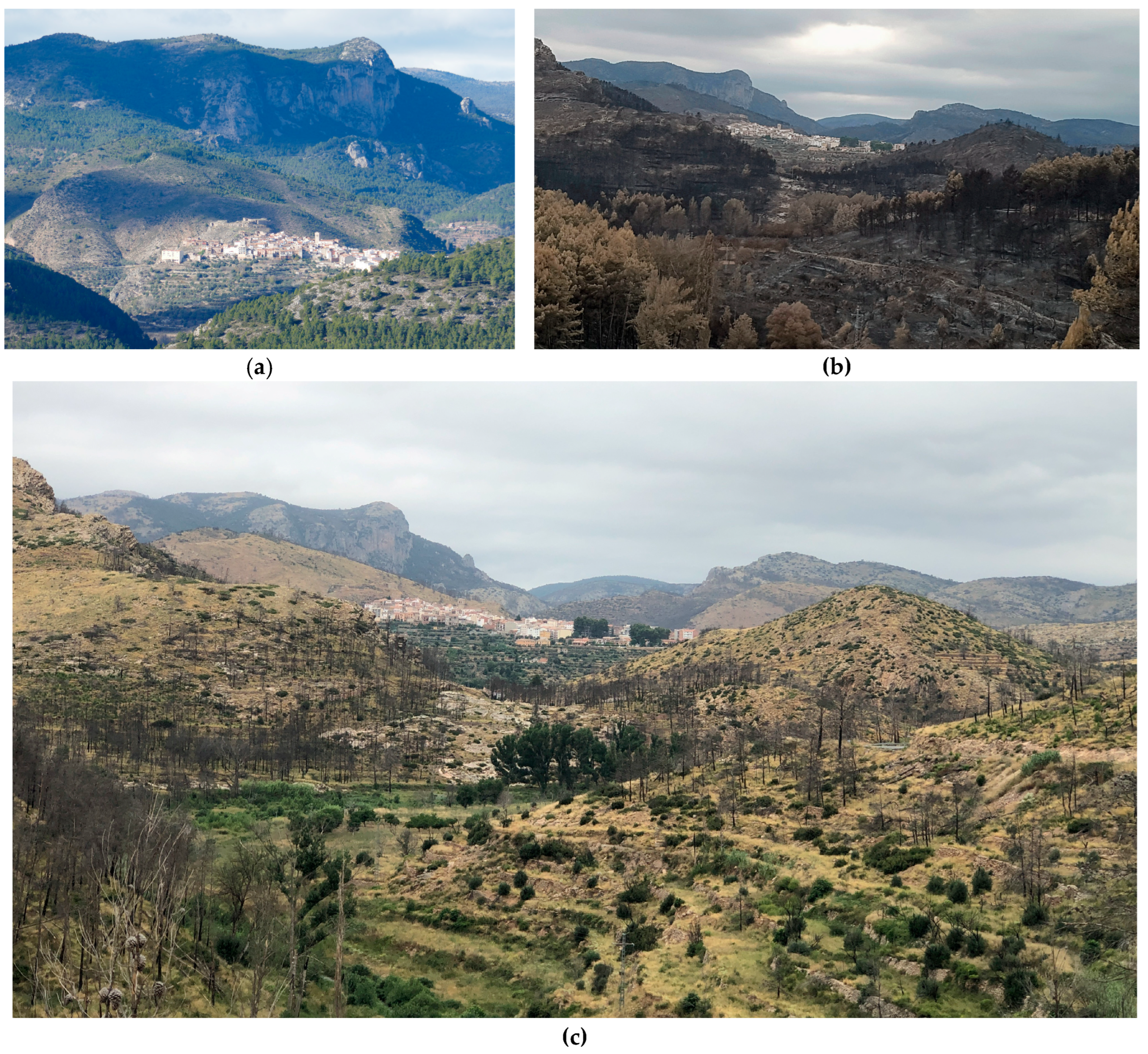

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Materials

2.3. Methods

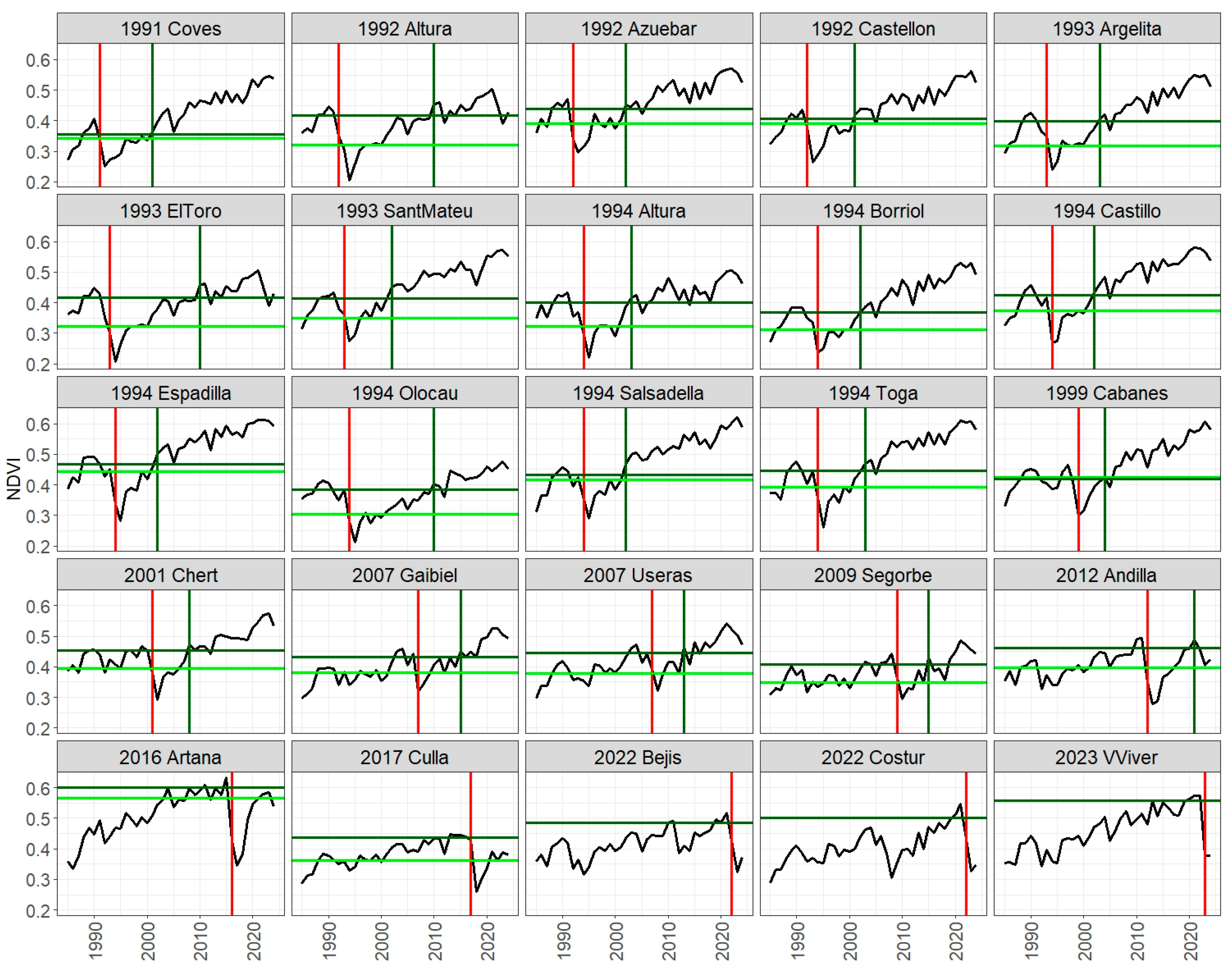

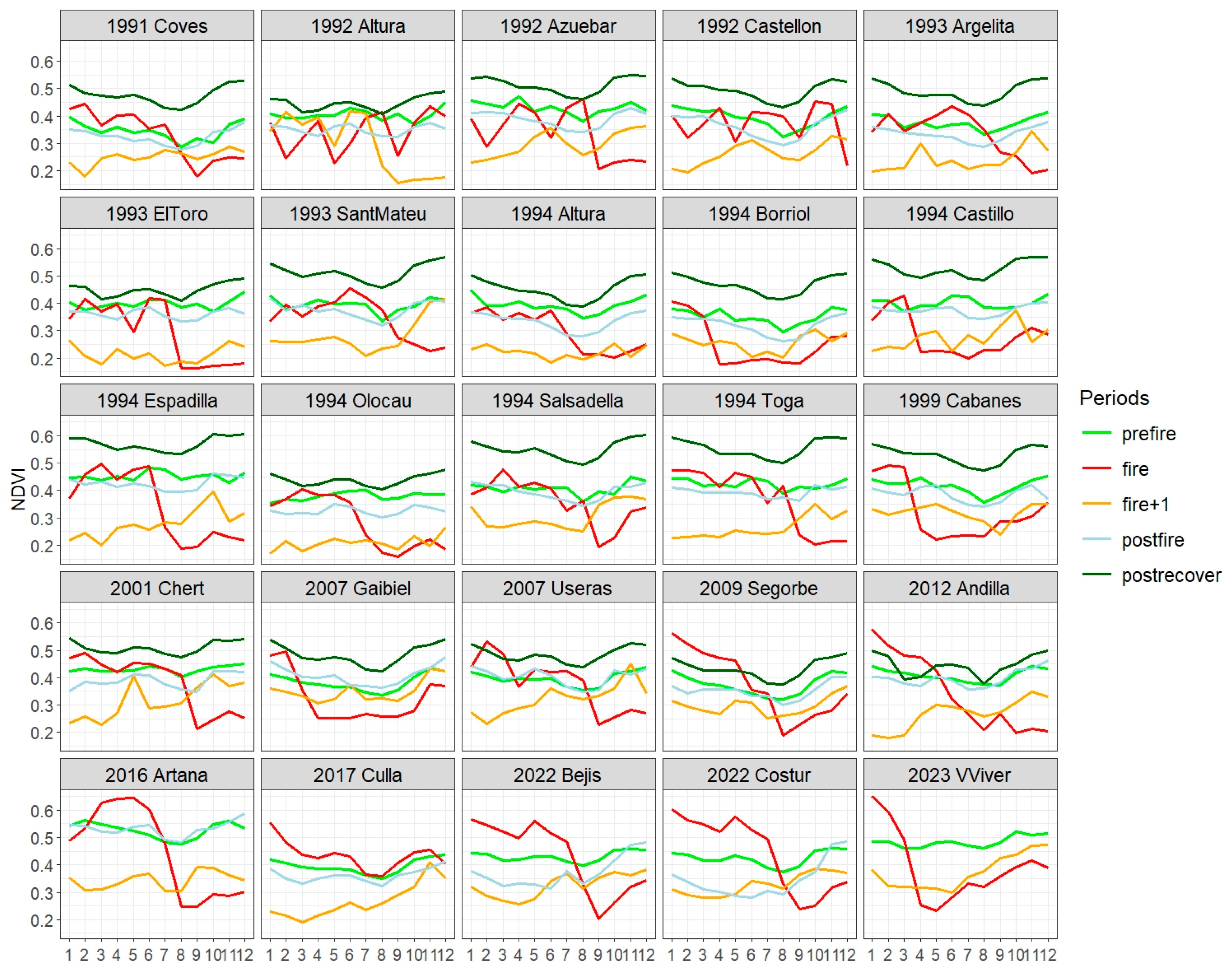

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| LULC | Land Use/Land Cover |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| CORINE | Coordination of Information on Environment |

| CE | Climate Engine |

| NBR | Normalized Burn Ratio |

| Km2 | Square kilometers |

References

- Parker, B. M.; Lewis, T.; Srivastava, S. K. Estimation and Evaluation of Multi-Decadal Fire Severity Patterns Using Landsat Sensors. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015, 170, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yengoh, G. T.; Dent, D.; Olsson, L.; Tengberg, A. E.; Tucker, C. J. Use of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to Assess Land Degradation at Multiple Scales: Current Status, Future Trends, and Practical Considerations, 2015., 1st ed.; SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science; Springer: Cham, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanorte, A.; Lasaponara, R.; Lovallo, M.; Telesca, L. Fisher–Shannon Information Plane Analysis of SPOT/VEGETATION Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) Time Series to Characterize Vegetation Recovery after Fire Disturbance. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2014, 26, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpakowski, D. M.; Jensen, J. L. R.; Butler, D. R.; Chow, T. E. A Study of the Relationship between Fire Hazard and Burn Severity in Grand Teton National Park, USA. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 98, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S. Un Viaje a La Antártida: Un Científico En El Continente Olvidado, 1a. edición.; Metatemas; Tusquets Editores: Barcelona, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Global Wildfire Information System – with minor processing by Our World in Data. Seasonal Wildfire Trends, 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/wildfires (accessed 2024-08-29).

- Jain, P.; Coogan, S. C. P.; Subramanian, S. G.; Crowley, M.; Taylor, S.; Flannigan, M. D. A Review of Machine Learning Applications in Wildfire Science and Management. Environ. Rev. 2020, 28, 478–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Stanturf, J.; Goodrick, S. Trends in Global Wildfire Potential in a Changing Climate. Forest Ecology and Management 2010, 259, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez Muñoz, R. Incendios Forestales. In Riesgos naturales; Ayala_Carcedo, F. J., Olcina Cantos, J., Eds.; Ariel, S.A.: Barcelona, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tazieff, H. Water risks on the Mediterranean coast. Met-mar. Revue de météorologie maritime de Météo-France.

- Viana-Soto, A.; Aguado, I.; Salas, J.; García, M. Identifying Post-Fire Recovery Trajectories and Driving Factors Using Landsat Time Series in Fire-Prone Mediterranean Pine Forests. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azorín Molina, C. El Viento, Un Elemento Climático Importante En El País Valencià. In Climas y tiempos del País Valenciano; Olcina Cantos, J., Moltó Mantero, E., Eds.; Publicacions Universitat d’Alacant, 2019; pp 78–84.

- Gouveia, C.; DaCamara, C. C.; Trigo, R. M. Post-Fire Vegetation Recovery in Portugal Based on Spot/Vegetation Data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viedma, O.; Meliá, J.; Segarra, D.; Garcia-Haro, J. Modeling Rates of Ecosystem Recovery after Fires by Using Landsat TM Data. Remote Sensing of Environment 1997, 61, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, L.; Camia, A.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Martín, M. P. Modeling Temporal Changes in Human-Caused Wildfires in Mediterranean Europe Based on Land Use-Land Cover Interfaces. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 378, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. T. T. R.; Coops, N. C.; Daniels, L. D.; Falls, R. W. Detecting Forest Damage after a Low-Severity Fire Using Remote Sensing at Multiple Scales. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2015, 35, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, S.; Haywood, A.; Jones, S.; Soto-Berelov, M.; Skidmore, A.; Nguyen, T. H. A Satellite Data Driven Approach to Monitoring and Reporting Fire Disturbance and Recovery across Boreal and Temperate Forests. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2020, 87, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Delgado, R.; Lloret, F.; Pons, X. Influence of Fire Severity on Plant Regeneration by Means of Remote Sensing Imagery. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2003, 24, 1751–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Wang, L.; McCabe, M. F. Multi-Sensor Remote Sensing for Drought Characterization: Current Status, Opportunities and a Roadmap for the Future. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 256, 112313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Qu, J. Satellite Applications for Detecting Vegetation Phenology. In Satellite-based Applications on Climate Change; Qu, J., Powell, A., Sivakumar, M. V. K., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escuin, S.; Navarro, R.; Fernández, P. Fire Severity Assessment by Using NBR (Normalized Burn Ratio) and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) Derived from LANDSAT TM/ETM Images. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2008, 29, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I.; Salas, J.; García, M.; Yebra, M.; Oliva, P. Satellite Remote Sensing Contributions to Wildland Fire Science and Management. Curr Forestry Rep 2020, 6, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João, T.; João, G.; Bruno, M.; João, H. Indicator-Based Assessment of Post-Fire Recovery Dynamics Using Satellite NDVI Time-Series. Ecological Indicators 2018, 89, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Malak, D.; Pausas, J. G. Fire Regime and Post-Fire Normalized Difference Vegetation Index Changes in the Eastern Iberian Peninsula (Mediterranean Basin). Int. J. Wildland Fire 2006, 15, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viedma, O.; Meliá, J. Monitoring Temporal Changes in the Spatial Patterns of a Mediterranean Shrubland Using LandsatTM Images. Diversity and Distributions 1999, 5, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, C.; Avena, G. C.; Olsen, E. R.; Ramsey, R. D.; Winn, D. S. Monitoring the Landscape Stability of Mediterranean Vegetation Relation to Fire with a Fractal Algorithm. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1998, 19, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montón Chiva, E.; Quereda Sala, J. Castellón, La Segunda Provincia Más Montañosa de España: ¿algo Más Que Un Lema Turístico? In Diego López Olivares. La visión integradora desde el turismo desde la geografía: libro homenaje: in memoriam; Ferrer Maestro, J. J., Ferreres Bonfill, J. B., Eds.; Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I; pp 265–287.

- Quereda Sala, J.; Montón Chiva, E. Los Elementos Del Clima: Distribución de Temperaturas y Precipitaciones. In Climas y tiempos del País Valenciano; Olcina Cantos, J., Moltó Mantero, E., Eds.; Publicacions Universitat d’Alacant, 2019; pp 72–77.

- Pérez Cueva, A. J. Los Climas Del País Valenciano. In Climas y tiempos del País Valenciano; Olcina Cantos, J., Moltó Mantero, E., Eds.; Publicacions Universitat d’Alacant, 2019; pp 85–94.

- Núñez Mora, J. Á. Datos Climáticos Básicos y Récords Atmosféricos En La Comunitat Valenciana. In Climas y tiempos del País Valenciano; Olcina Cantos, J., Moltó Mantero, E., Eds.; Publicacions Universitat d’Alacant, 2019; pp 137–144.

- Olcina Cantos, J. Cuando El Cielo Se Enfada. Peligrosidad Climática y Riesgos. In Climas y tiempos del País Valenciano; Olcina Cantos, J., Moltó Mantero, E., Eds.; Publicacions Universitat d’Alacant, 2019; pp 117–131.

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. CORINE Land Cover 1990 (Vector/Raster 100 m), Europe, 6-Yearly CC-BY 4.0 Scne.Es. https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/index.jsp#. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. CORINE Land Cover 2018 (Vector/Raster 100 m), Europe, 6-Yearly. CC-BY 4.0 Scne.Es. https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/index.jsp#. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus. CORINE Land Cover Nomenclature Guidelines, 2024. https://land.copernicus.eu/content/corine-land-cover-nomenclature-guidelines/html/ (accessed 2024-02-21).

- Valencian Government - Integrated forest fire management system. Fire Statistics. https://prevencionincendiosgva.es/Incendios/EstadisticasIncendios (accessed 2025-03-04).

- Detalle nota de prensa - Comunica GVA - Generalitat Valenciana. Comunica GVA. https://comunica.gva.es/va/detalle?id=368980826&site=174859783 (accessed 2025-06-19).

- MITECO - Ministry for the ecological transition and the demographic challenge. General Statistics on Forest Fires (EGIF). https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/temas/incendios-forestales/estadisticas-datos.html (accessed 2025-02-17).

- MITECO - Ministry for the ecological transition and the demographic challenge. Forest Fires. Information Updates. https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/temas/incendios-forestales/estadisticas-avances.html (accessed 2025-03-04).

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. CORINE Land Cover 2000 (Vector/Raster 100 m), Europe, 6-Yearly CC-BY 4.0 Scne.Es. https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/index.jsp#. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. CORINE Land Cover 2006 (Vector/Raster 100 m), Europe, 6-Yearly CC-BY 4.0 Scne.Es. https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/index.jsp#. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. CORINE Land Cover 2012 (Vector/Raster 100 m), Europe, 6-Yearly CC-BY 4.0 Scne.Es. https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/index.jsp#. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. CORINE Land Cover Roadmap. https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover?tab=roadmap (accessed 2025-06-15).

- Climate Engine Team. Dataset Information. Landsat At-Surface Reflectance/Landsat Top-Of-Atmosphere Reflectance, 2024.

- Remote Sensing Handbook: Volume I: Remotely Sensed Data Characterization, Classification, and Accuracies; Thenkabail, P. S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, H. E.; McVicar, T. R.; Van Dijk, A. I. J. M.; Schellekens, J.; De Jeu, R. A. M.; Bruijnzeel, L. A. Global Evaluation of Four AVHRR–NDVI Data Sets: Intercomparison and Assessment against Landsat Imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment 2011, 115, 2547–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J. C.; Wulder, M. A.; Hermosilla, T.; Coops, N. C.; Hobart, G. W. A Nationwide Annual Characterization of 25 Years of Forest Disturbance and Recovery for Canada Using Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 194, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillesand, T. M.; Kiefer, R. W.; Chipman, J. W. Remote Sensing and Image Interpretation, Seventh edition.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Yang, S.; Yin, K.; Chan, P. Challenges to Quantitative Applications of Landsat Observations for the Urban Thermal Environment. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2017, 59, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Giri, C. P.; Vogelmann, J. E. Land-Cover Change Detection. In Remote Sensing of Land Use and Land Cover: Principles and Applications; Giri, C. P., Ed.; Remote Sensing Applications Series; CRC Press: Hoboken, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, J. L.; Hegewisch, K. C.; Daudert, B.; Morton, C. G.; Abatzoglou, J. T.; McEvoy, D. J.; Erickson, T. Climate Engine: Cloud Computing and Visualization of Climate and Remote Sensing Data for Advanced Natural Resource Monitoring and Process Understanding. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2017, 98, 2397–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desert Research Institute and University of California Merced. Climate Engine, Version 2.1. (1985-2024). http://climateengine.org (accessed 2025-03-20).

- Ravanelli, R.; Nascetti, A.; Cirigliano, R. V.; Rico, C. D.; Leuzzi, G.; Monti, P.; Crespi, M. Monitoring the Impact of Land Cover Change on Surface Urban Heat Island through Google Earth Engine: Proposal of a Global Methodology, First Applications and Problems. Remote Sensing 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Driscol, J.; Sarigai, S.; Wu, Q.; Chen, H.; Lippitt, C. D. Google Earth Engine and Artificial Intelligence (AI): A Comprehensive Review. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Mutanga, O. Google Earth Engine Applications Since Inception: Usage, Trends, and Potential. Remote Sensing 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, M. P.; Stephens, S. L.; Collins, B. M.; Agee, J. K.; Aplet, G.; Franklin, J. F.; Fulé, P. Z. Reform Forest Fire Management. Science 2015, 349, 1280–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xulu, S.; Mbatha, N.; Peerbhay, K. Burned Area Mapping over the Southern Cape Forestry Region, South Africa Using Sentinel Data within GEE Cloud Platform. IJGI 2021, 10, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulard, C. E.; Albano, C. M.; Villarreal, M. L.; Walker, J. J. Continuous 1985–2012 Landsat Monitoring to Assess Fire Effects on Meadows in Yosemite National Park, California. Remote Sensing 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z. S.; Scott, S. L.; Desmet, P. G.; Hoffman, M. T. Application of Landsat-Derived Vegetation Trends over South Africa: Potential for Monitoring Land Degradation and Restoration. Ecological Indicators 2020, 113, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L. K.; Gupta, R.; Fatima, N. Assessing the Predictive Efficacy of Six Machine Learning Algorithms for the Susceptibility of Indian Forests to Fire. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2022, 31, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marzo, T.; Pflugmacher, D.; Baumann, M.; Lambin, E. F.; Gasparri, I.; Kuemmerle, T. Characterizing Forest Disturbances across the Argentine Dry Chaco Based on Landsat Time Series. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 98, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. ALOS World 3D 30 Meter DEM., 2021. [CrossRef]

- OpenTopography. ALOS World 3D - 30m. https://portal.opentopography.org/raster?opentopoID=OTALOS.112016.4326.2 (accessed 2025-06-05).

- Dirección General del Agua (DGA). Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Red Hidrográfica Básica Procedente MDT 100x100. https://www.mapama.gob.es/app/descargas/descargafichero.aspx?f=Rios_MDT_100x100.zip (accessed 2025-04-24).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Red Hidrográfica Básica. Descripción Del Servicio. https://sig.mapama.gob.es/Docs/PDFServicios/Rios_MT100x100.pdf (accessed 2025-06-15).

- Institut Cartogràfic Valencià; Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Delimitació Territorial: Comarques de La Comunitat Valenciana, 2024.

- EFE News Agency. El Incendio de l’Alcalatén de 2007 Fue Provocado Por Trabajos En La Red Eléctrica Sin Licencia. El Mundo online, 2010.

- Dalezios, N. R.; Kalabokidis, K.; Koutsias, N.; Vasilakos, C. Wlidfires and Remote Sensing. An Overview. In Remote sensing of hydrometeorological hazards; Petropoulos, G. P., Islam, T., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton London New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saghafi, M. Extract NBR index using GEE (SLC issue resolved). https://github.com/MostafaSaghafi/NBR_GEE?tab=readme-ov-file#extract-nbr-index-using-gee-slc-issue-resolved (accessed 2025-03-02).

- Stal, C.; Sloover, L. D.; Verbeurgt, J.; Wulf, A. D. On Finding a Projected Coordinate Reference System. Geographies 2022, 2, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Engine Team. On-Demand Insights from Climate and Earth Observations Data, 2025. https://www.climateengine.org/.

- Chen, X.; Vogelmann, J. E.; Rollins, M.; Ohlen, D.; Key, C. H.; Yang, L.; Huang, C.; Shi, H. Detecting Post-Fire Burn Severity and Vegetation Recovery Using Multitemporal Remote Sensing Spectral Indices and Field-Collected Composite Burn Index Data in a Ponderosa Pine Forest. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2011, 32, 7905–7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana-Soto, A.; García, M.; Aguado, I.; Salas, J. Assessing Post-Fire Forest Structure Recovery by Combining LiDAR Data and Landsat Time Series in Mediterranean Pine Forests. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 108, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R. E.; Yang, Z.; Cohen, W. B.; Pfaff, E.; Braaten, J.; Nelson, P. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Forest Disturbance and Regrowth within the Area of the Northwest Forest Plan. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 122, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéret, V.; Denux, J.-P. Analysis of MODIS NDVI Time Series to Calculate Indicators of Mediterranean Forest Fire Susceptibility. GIScience & Remote Sensing 2011, 48, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- As climate changes, world grapples with a wildfire crisis. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/climate-changes-world-grapples-wildfire (accessed 2025-07-02).

- Wildfires and Climate Change - NASA Science. https://science.nasa.gov/earth/explore/wildfires-and-climate-change/ (accessed 2025-07-02).

- Wildfires and Climate Change - Center for Climate and Energy SolutionsCenter for Climate and Energy Solutions. https://www.c2es.org/content/wildfires-and-climate-change/ (accessed 2025-07-02).

- Wildfires | Environmental Defense Fund. https://www.edf.org/climate/heres-how-climate-change-affects-wildfires (accessed 2025-07-02).

- Wildfire climate connection | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.noaa.gov/noaa-wildfire/wildfire-climate-connection (accessed 2025-07-02).

- The Amazon, Siberia, Indonesia: A World of Fire - The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/28/climate/fire-amazon-africa-siberia-worldwide.html (accessed 2025-07-02).

- Kloster, S.; Lasslop, G. Historical and Future Fire Occurrence (1850 to 2100) Simulated in CMIP5 Earth System Models. Global and Planetary Change 2017, 150, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens-Rumann, C. S.; Morgan, P. Tree Regeneration Following Wildfires in the Western US: A Review. fire ecol 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical Summary | Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/chapter/technical-summary/ (accessed 2025-07-02).

- Teckentrup, L.; Harrison, S. P.; Hantson, S.; Heil, A.; Melton, J. R.; Forrest, M.; Li, F.; Yue, C.; Arneth, A.; Hickler, T.; Sitch, S.; Lasslop, G. Response of Simulated Burned Area to Historical Changes in Environmental and Anthropogenic Factors: A Comparison of Seven Fire Models. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 3883–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, M.; Bedia, J.; Di Liberto, F.; Fiorucci, P.; Von Hardenberg, J.; Koutsias, N.; Llasat, M.-C.; Xystrakis, F.; Provenzale, A. Decreasing Fires in Mediterranean Europe. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hall, J.; Van Wees, D.; Andela, N.; Hantson, S.; Giglio, L.; Van Der Werf, G. R.; Morton, D. C.; Randerson, J. T. Multi-Decadal Trends and Variability in Burned Area from the Fifth Version of the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED5). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 5227–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andela, N.; Morton, D. C.; Giglio, L.; Chen, Y.; Van Der Werf, G. R.; Kasibhatla, P. S.; DeFries, R. S.; Collatz, G. J.; Hantson, S.; Kloster, S.; Bachelet, D.; Forrest, M.; Lasslop, G.; Li, F.; Mangeon, S.; Melton, J. R.; Yue, C.; Randerson, J. T. A Human-Driven Decline in Global Burned Area. Science 2017, 356, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora Aliseda, J.; Horcajo Romo, A. I.; Castro Serrano, J.; Garrido Velarde, J. Evolución de los incendios forestales en España y Extremadura. ¿Correlación con el Cambio Climático? An. geogr. Univ. Complut. 2024, 44, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeda Cartañà, X.; Mataix-Solera, J.; Francos, M.; Farguell, J. Grandes incendios forestales en España y alteraciones de su régimen en las últimas décadas. In Geografia, Riscos e Proteção Civil. Homenagem ao Professor Doutor Luciano Lourenço.; Nunes, A., Amaro, A., Vieira, A., Velez de Castro, F., Félix, F., Eds.; RISCOS - Associação Portuguesa de Riscos, Prevenção e Segurança, 2021; pp 147–161. [CrossRef]

- Ruffault, J.; Curt, T.; Moron, V.; Trigo, R. M.; Mouillot, F.; Koutsias, N.; Pimont, F.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Barbero, R.; Dupuy, J.-L.; Russo, A.; Belhadj-Khedher, C. Increased Likelihood of Heat-Induced Large Wildfires in the Mediterranean Basin. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawchuk, M. A.; Moritz, M. A. Constraints on Global Fire Activity Vary across a Resource Gradient. Ecology 2011, 92, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Artés, R.; Garófano-Gómez, V.; Oliver-Villanueva, J. V.; Rojas-Briales, E. Land Use/Cover Change Analysis in the Mediterranean Region: A Regional Case Study of Forest Evolution in Castelló (Spain) over 50 Years. Land Use Policy 2022, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, L.; Camia, A.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Martín, M. P. Modeling Temporal Changes in Human-Caused Wildfires in Mediterranean Europe Based on Land Use-Land Cover Interfaces. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 378, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gónzalez Hidalgo, J. C. Una Teoría Con Fallos. Hechos, Mitos y Paradojas Del Cambio Del Clima; Aula Magna. Proyecto Clave; McGraw Hill.

- Fernández, A.; Illera, P.; Casanova, J. L. Automatic Mapping of Surfaces Affected by Forest Fires in Spain Using AVHRR NDVI Composite Image Data. Remote Sensing of Environment 1997, 60, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, F.; Romanelli, S.; Bottai, L.; Zipoli, G. Use of NOAA-AVHRR NDVI Images for the Estimation of Dynamic Fire Risk in Mediterranean Areas. Remote Sensing of Environment 2003, 86, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doctor Cabrera, A. M. Los incendios forestales de más de 100 hectáreas en Andalucía (1988-2020): caracterización general y análisis de su afección en la provincia de Huelva. Ingeo 2025, No. 83, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacouture, D. L.; Broadbent, E. N.; Crandall, R. M. Detecting Vegetation Recovery after Fire in A Fire-Frequented Habitat Using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). Forests 2020, 11, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvira, N. J.; Lloret, F.; Jaime, L.; Margalef-Marrase, J.; Pérez Navarro, M. Á.; Batllori, E. Species Climatic Niche Explains Post-Fire Regeneration of Aleppo Pine (Pinus Halepensis Mill.) under Compounded Effects of Fire and Drought in East Spain. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 798, 149308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, N. G.; Turner, M. G. Where Are the Trees? Extent, Configuration, and Drivers of Poor Forest Recovery 30 Years after the 1988 Yellowstone Fires. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, 524, 120536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanos, C. A.; Daskalakou, E. N. Reproduction in Pinus Halepensis and P. Brutia. In Ecology, Biogeography and Management of Pinus Halepensis and P. Brutia. In Ecology, Biogeography and Management of Pinus Halepensis and P. Brutia. Forest Ecosystems in the Mediterranean Basin; Ne’eman, G., Traubaud, L., Eds.; Backhuys Publishers: Leyden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Presentación SIOSE. https://www.siose.es/presentacion (accessed 2025-07-04).

- Potapov, P.; Hansen, M. C.; Pickens, A.; Hernandez-Serna, A.; Tyukavina, A.; Turubanova, S.; Zalles, V.; Li, X.; Khan, A.; Stolle, F.; Harris, N.; Song, X.-P.; Baggett, A.; Kommareddy, I.; Kommareddy, A. The Global 2000-2020 Land Cover and Land Use Change Dataset Derived From the Landsat Archive: First Results. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

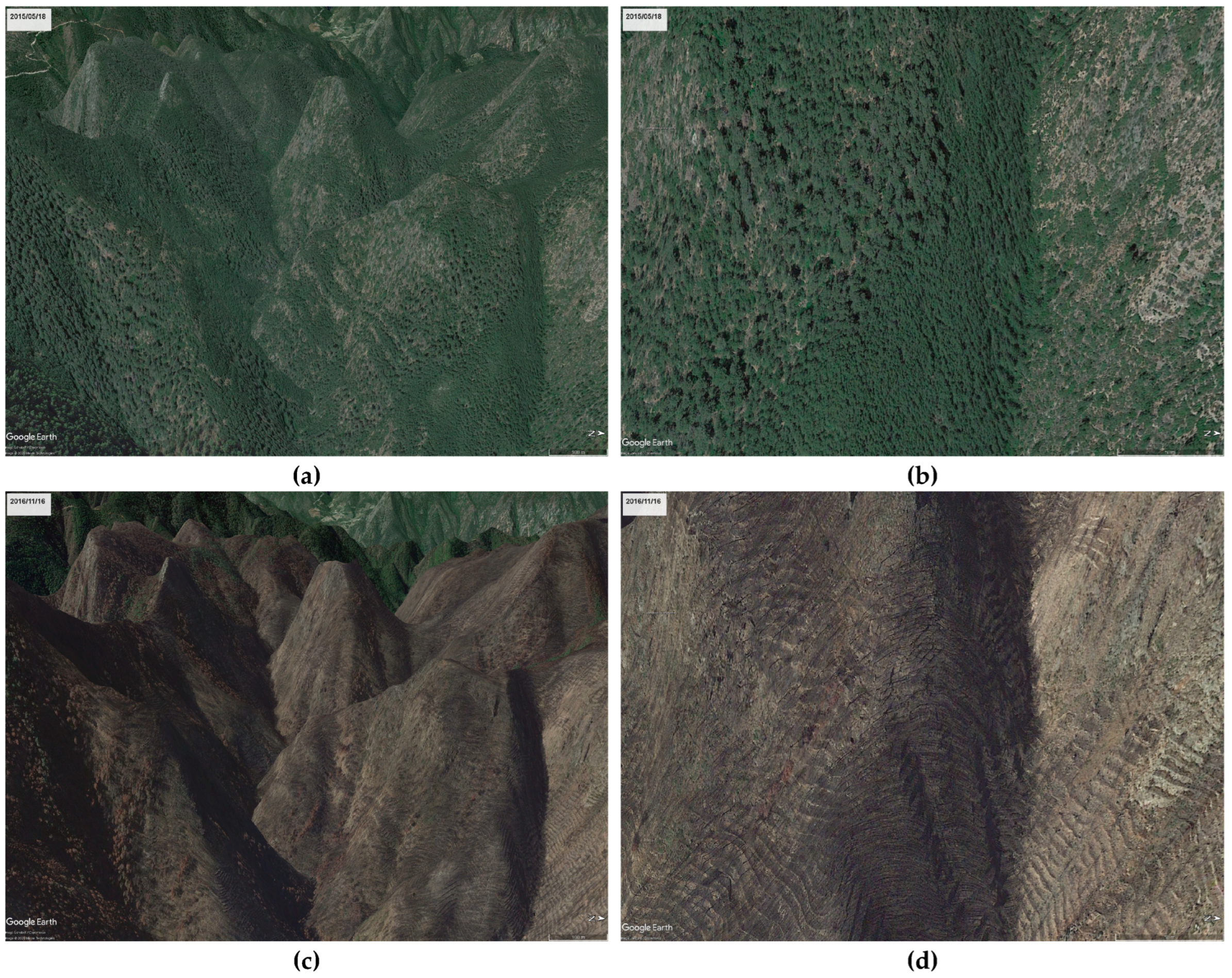

- Google Earth. General View of Artana Fire, 2015/05/18. 39°54’51.77"N - 0°17’19.28"W, 2015.

- Google Earth. Detail View of Artana Fire, 2015/05/18. 39°55’8.59"N - 0°16’55.60"W, 2015.

- Google Earth. General View of Artana Fire, 2016/11/16. 39°54’51.77"N - 0°17’19.28"W, 2016.

- Google Earth. Detail View of Artana Fire, 2016/11/16. 39°55’8.59"N - 0°16’55.60"W, 2016.

- Google Earth. Detail View of Artana Fire, 2022/02/27. 39°55’8.59"N - 0°16’55.60"W, 2022.

- Google Earth. General View of Artana Fire, 2022/02/27. 39°54’51.77"N - 0°17’19.28"W, 2022.

| Date | Start municipality | Total area (ha.) | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991/08/08 | Coves de Vinromà | 600 | Rubbish burning |

| 1992/08/30 | Altura | 3,310 | Unknown |

| 1992/08/31 | Azuébar | 1,042 | Stubble burning |

| 1992/12/08 | Castellón | 1,634 | Bonfires |

| 1993/08/07 | El Toro | 2,135 | Unknown |

| 1993/09/12 | Argelita | 4,896 | Bonfires |

| 1993/09/13 | Sant Mateu | 3,520 | Stubble burning |

| 1994/04/02 | Castillo de Villamalefa | 7,120 | Bonfires |

| 1994/04/09 | Borriol | 1,113 | Bonfires |

| 1994/07/01 | Olocau del Rey1 | 11,381 | Lightning |

| 1994/07/02 | Espadilla | 19,310 | Lightning |

| 1994/08/10 | Altura | 3,220 | Unknown |

| 1994/08/26 | Salsadella | 2,800 | Unknown |

| 1994/09/08 | Toga | 778 | Intentional |

| 1999/04/07 | Cabanes | 742 | Intentional |

| 2001/08/29 | Chert | 3,200 | Lightning |

| 2007/03/07 | Gaibiel | 1,045 | Lightning |

| 2007/08/28 | Useras | 5,775 | Railway2 |

| 2009/07/23 | Segorbe | 832 | Lightning |

| 2012/06/29 | Andilla1 | 23,273 | Negligence |

| 2016/07/25 | Artana | 1,487 | Lightning |

| 2017/12/29 | Culla | 535 | Negligence |

| 2022/08/14 | Costur | 728 | Other causes |

| 2022/08/15 | Bejís | 16,824 | Lightning |

| 2023/03/23 | Villanueva de Viver | 3,381 | Other causes |

| Package | Tasks |

|---|---|

| Terra | Reading raster data |

| geodata | Administrative boundaries |

| Gpkg | Reading CORINE data |

| Sf | Spatial data processing |

| Utils | Reading csv files |

| data.table | Linking CORINE layers with categories |

| Dlookr | Outlier imputation |

| imputeTS | Missing data imputation |

| tidyverse | Data processing, results by areas and comparative tables |

| tidygeocoder | Retrieving geographical coordinates |

| ggplot2 | Graphic visualisation |

| basemapR | Base maps |

| grDevices | Saving graphs and maps |

| patchwork | Image compositions |

| Coordinates | Data |

|---|---|

| Maximum latitude | 41.0 oN |

| Minimum latitude | 39.6 oN |

| Maximum longitude | 0.7 oE |

| Maximum longitude | 1.0 oW |

| Date | Start municipality | LULC1 | dNDVI2 | %rec NDVI+53 |

dNBR4 | %rec NBR+55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991/08/08 | Coves de Vinromà | 1.70 | 0.103 | 96.3 | 0.170 | 69.0 |

| 1992/08/30 | Altura | 13.70 | 0.212 | 76.7 | 0.129 | 57.9 |

| 1992/08/31 | Azuébar | 7.73 | 0.143 | 89.0 | 0.093 | 69.1 |

| 1992/12/08 | Castellón | 7.83 | 0.144 | 95.9 | 0.169 | 74.7 |

| 1993/08/07 | El Toro | 29.67 | 0.208 | 77.6 | 0.171 | 79.0 |

| 1993/09/12 | Argelita | 11.75 | 0.158 | 79.5 | 0.155 | 52.7 |

| 1993/09/13 | Sant Mateu | 8.61 | 0.140 | 84.3 | 0.117 | 68.1 |

| 1994/04/02 | Castillo de Villamalefa | 43.49 | 0.157 | 87.5 | 0.141 | 55.2 |

| 1994/04/09 | Borriol | 0.76 | 0.131 | 85.0 | 0.183 | 32.8 |

| 1994/07/01 | Olocau del Rey | 44.45 | 0.172 | 78.7 | 0.149 | 51.3 |

| 1994/07/02 | Espadilla | 41.54 | 0.185 | 94.9 | 0.209 | 70.3 |

| 1994/08/10 | Altura | 22.28 | 0.181 | 80.3 | 0.160 | 38.4 |

| 1994/08/26 | Salsadella | 3.90 | 0.143 | 96.2 | 0.188 | 102.0 |

| 1994/09/08 | Toga | 45.52 | 0.183 | 88.1 | 0.233 | 45.4 |

| 1999/04/07 | Cabanes | 0.89 | 0.120 | 102.0 | 0.142 | 101.7 |

| 2001/08/29 | Chert | 29.60 | 0.160 | 87.1 | 0.149 | 78.7 |

| 2007/03/07 | Gaibiel | 8.71 | 0.134 | 88.3 | 0.080 | 59.8 |

| 2007/08/28 | Useras | 2.69 | 0.148 | 85.1 | 0.195 | 58.2 |

| 2009/07/23 | Segorbe | 17.32 | 0.113 | 85.1 | 0.171 | 55.6 |

| 2012/06/29 | Andilla | 30.62 | 0.183 | 86.4 | 0.208 | 75.6 |

| 2016/07/25 | Artana | 70.30 | 0.265 | 94.3 | 0.227 | 86.8 |

| 2017/12/29 | Culla | 0.96 | 0.177 | 82.8 | 0.190 | 69.3 |

| 2022/08/14 | Costur | 11.77 | 0.169 | -----6 | 0.228 | -----6 |

| 2022/08/15 | Bejís | 42.48 | 0.211 | -----6 | 0.163 | -----6 |

| 2023/03/23 | Villanueva de Viver | 58.36 | 0.214 | -----6 | 0.165 | -----6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).