Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

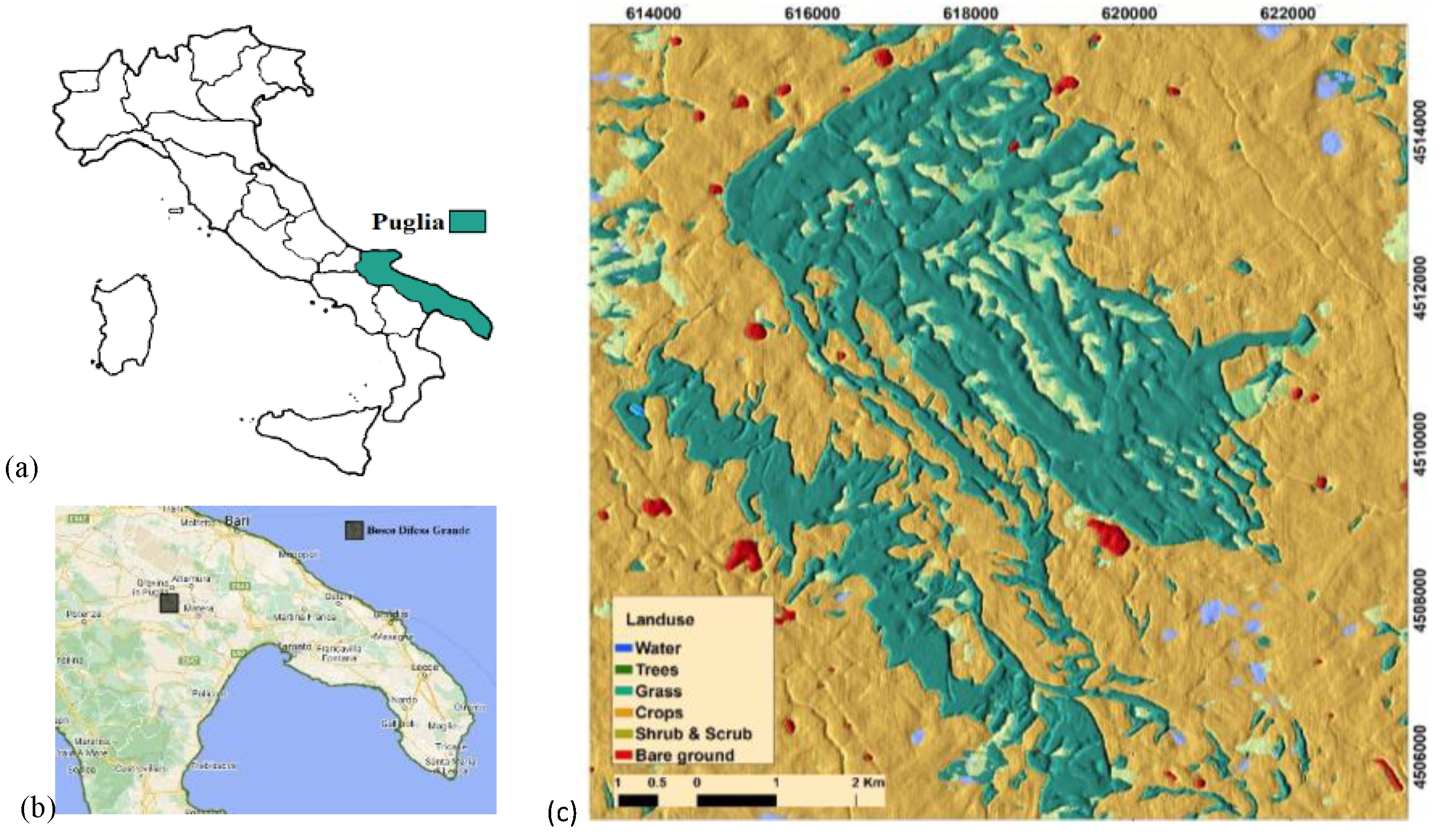

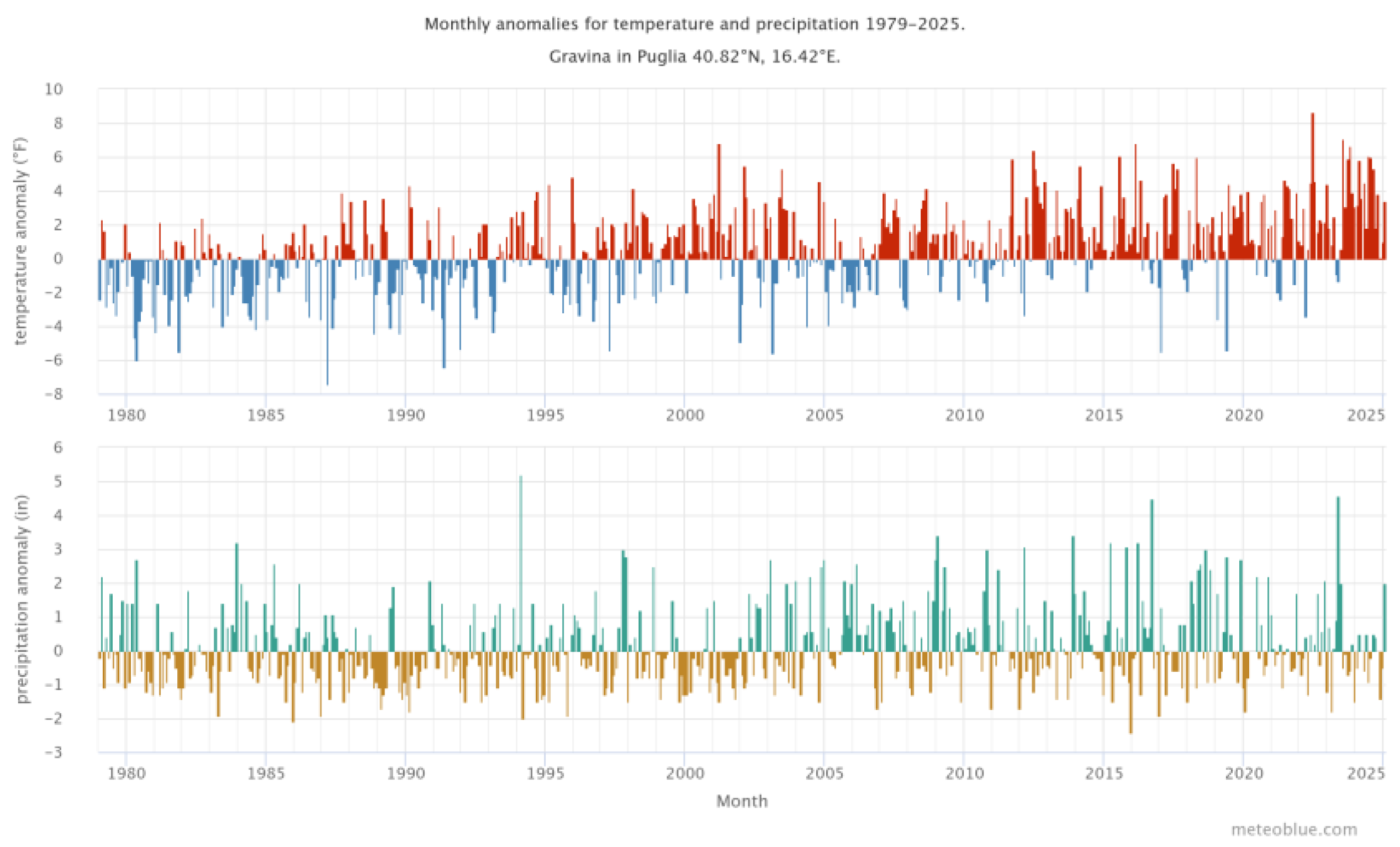

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Burned severity and Vegetation Recovery

| dNBR < 0.100 | dNDVI < 0.07 | Very Low/ Unburened |

| 0.100 ≤ dNBR ≤ 0.255 | 0.08 ≤ dNDV ≤ 0.13 | Low |

| 0.256 ≤ dNBR ≤ 0.419 | 0.13 ≤ dNDV ≤ 0.20 | Moderate |

| 0.420 ≤ dNBR ≤ 0.660 | 0.33 ≤ dNDV ≤ 0.44 | High |

| dNBR > 0.660 | dNDV > 0.45 | Very High |

3. Results and Discussion

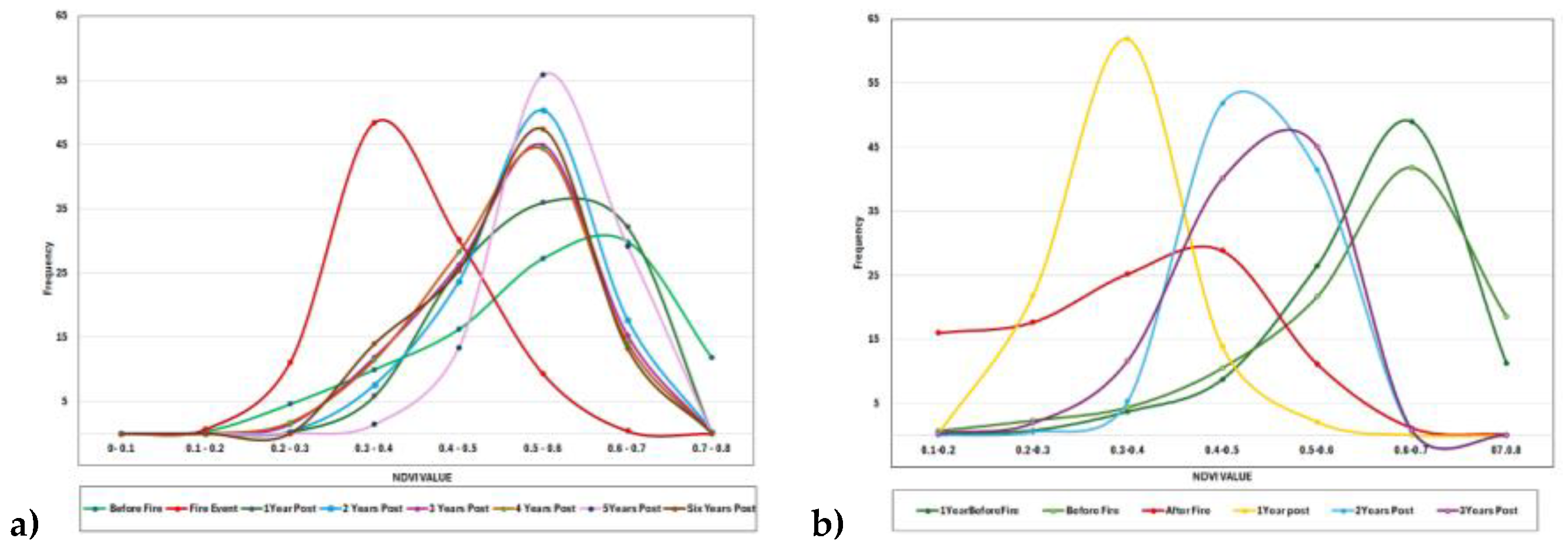

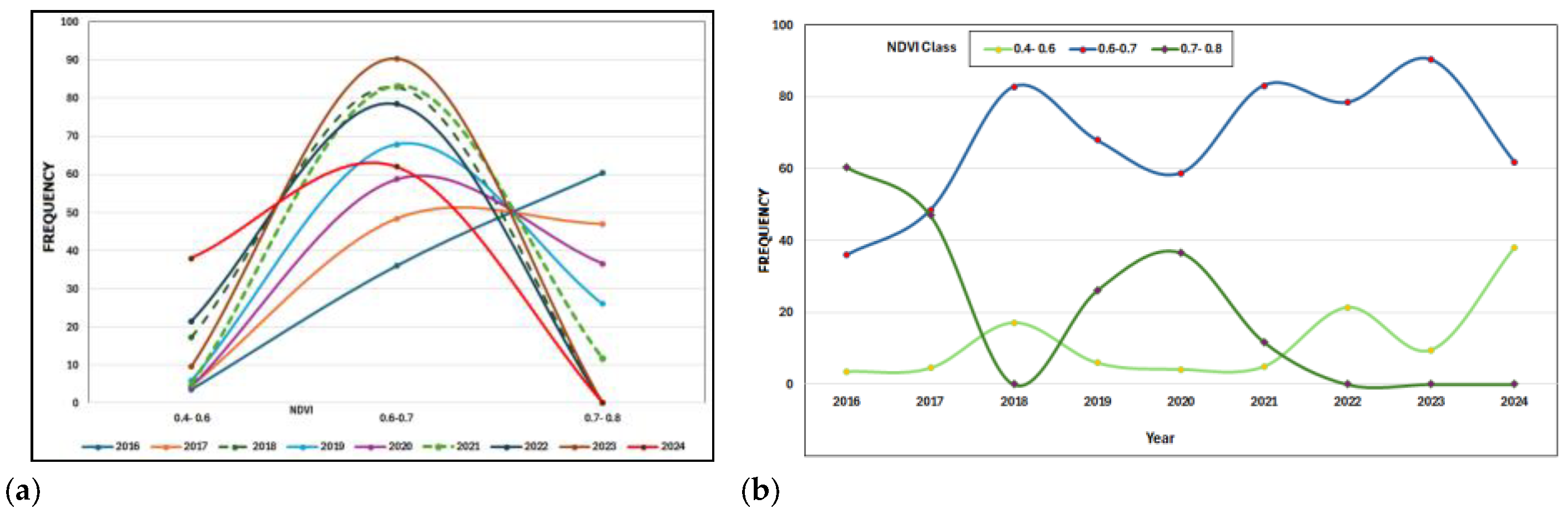

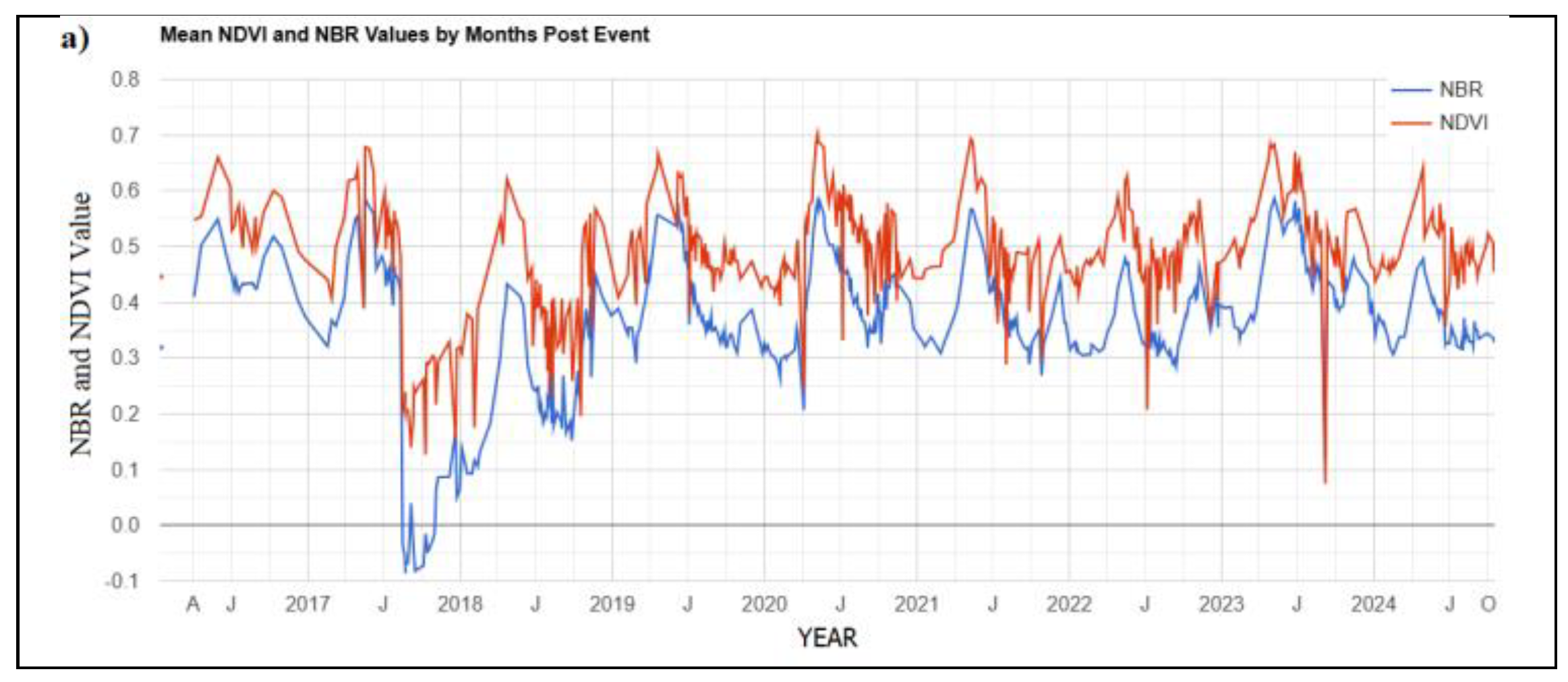

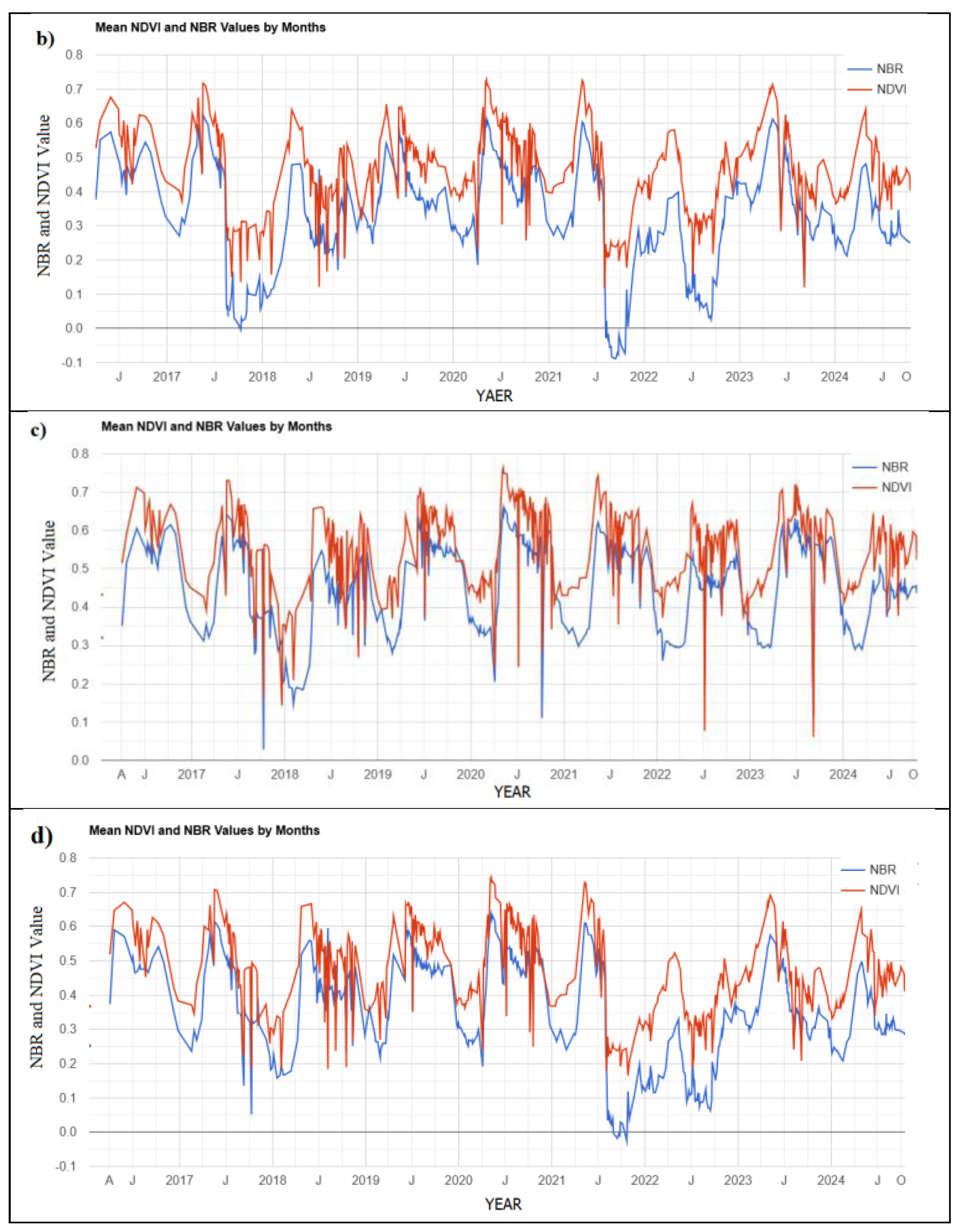

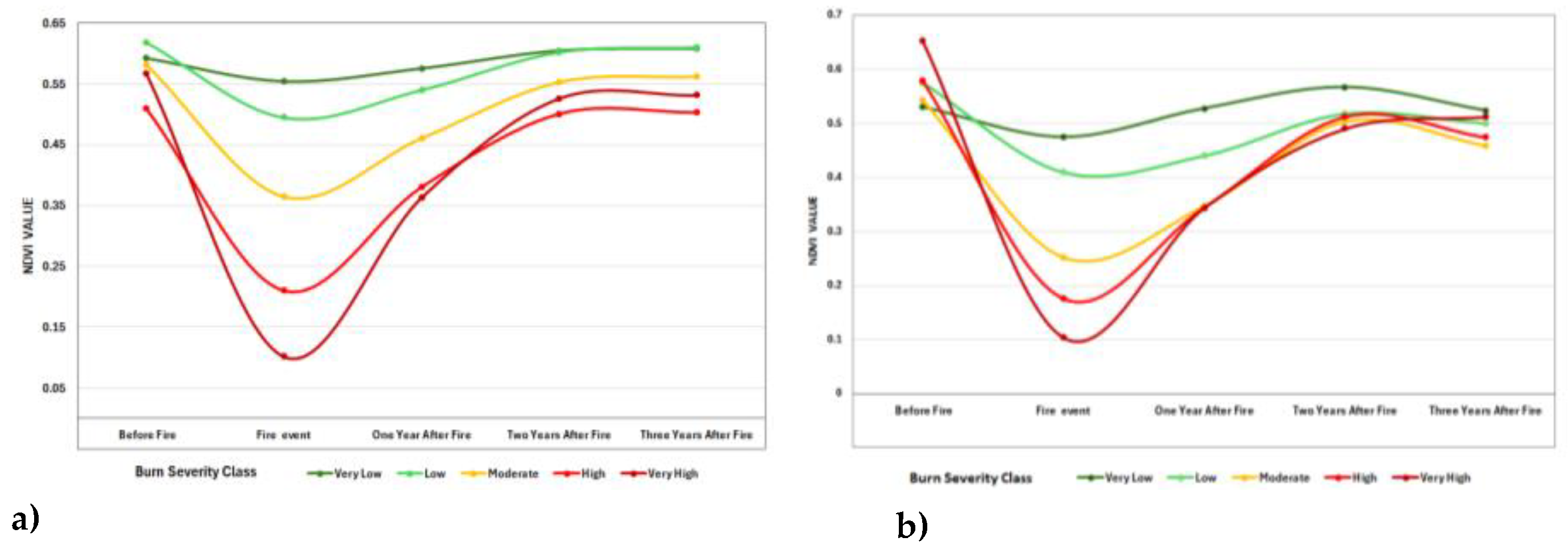

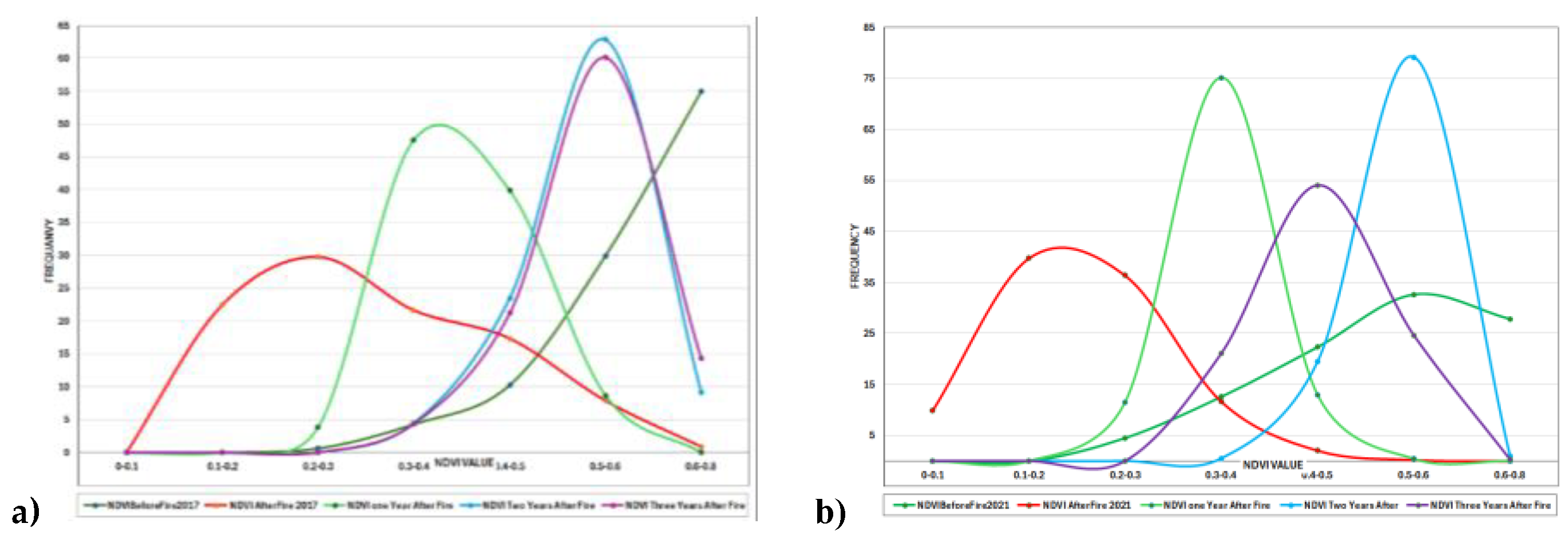

3.1. Time Series of Mean NDVI and NBR

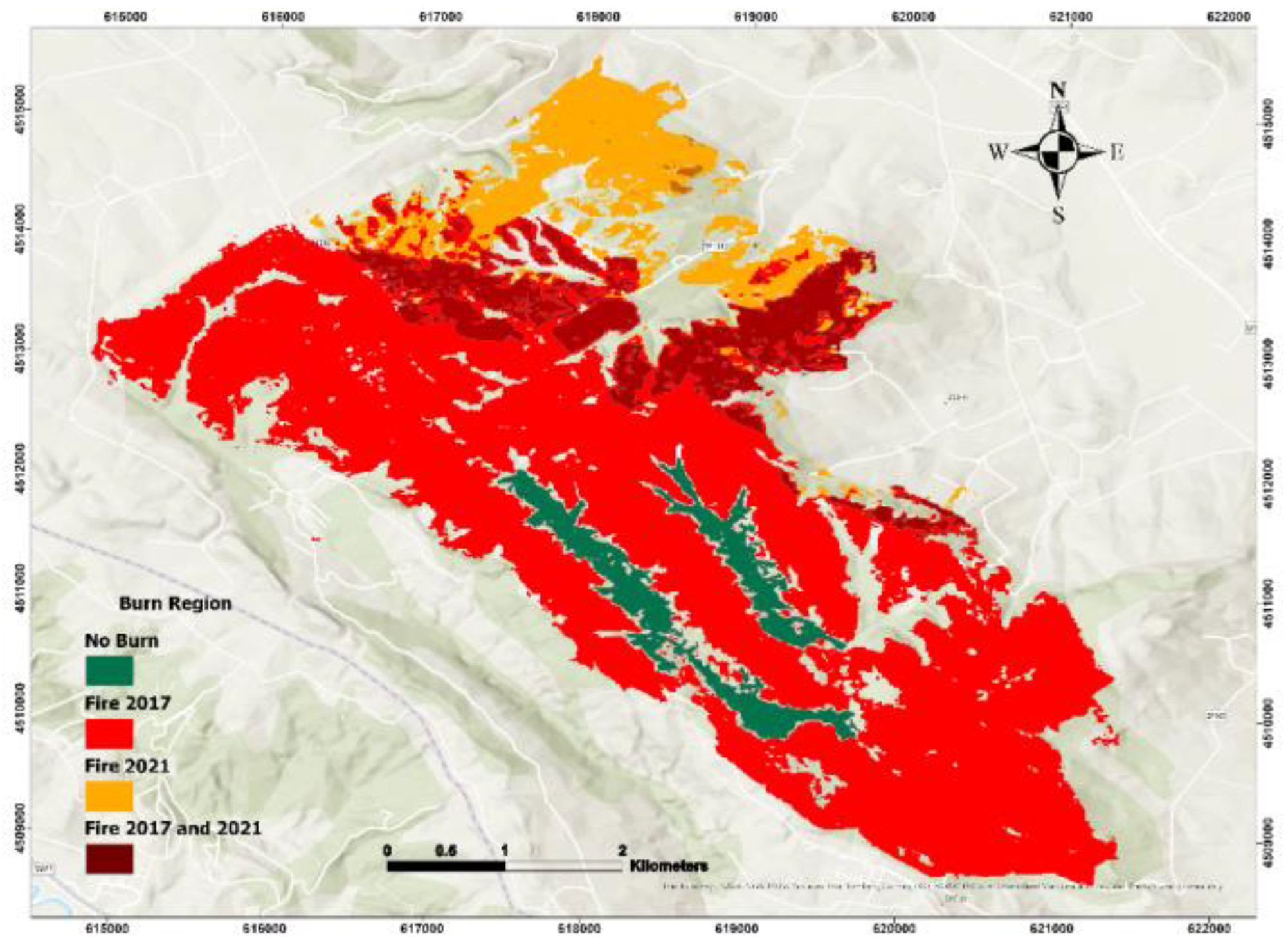

3.2. Burn Severity

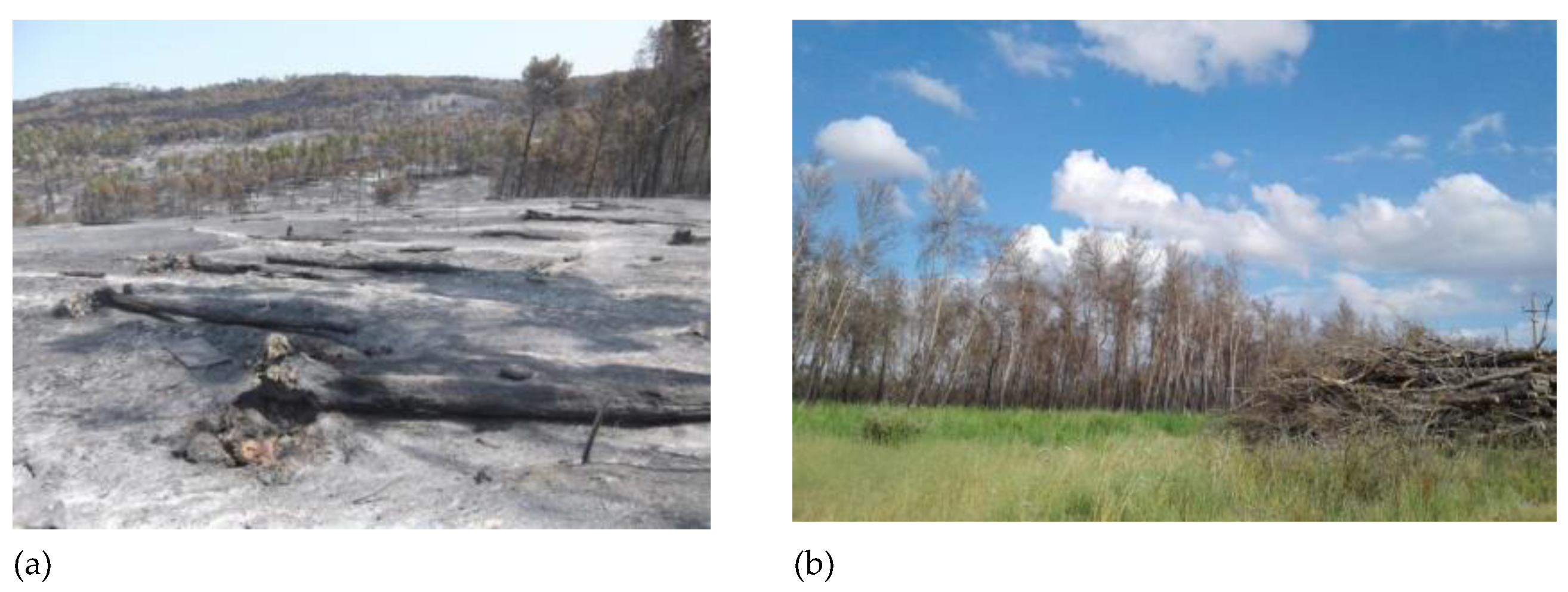

3.3. Burn Severity and Vegetation Regrowth

3.4. Vegetation Recovery Evaluation in Burn and Nonburn Regions

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J. Pausas. and J. E. Keeley, “Wildfires as an ecosystem service,” Front. Ecol. Environ., 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. T. Kelly, K. M. Giljohann, A. Duane, and etal, “Fire and biodiversity in the Anthropocene,” Science, vol. 370, no. 6519, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. M. J. S. Bowman, K. Crystal A, J. T. Abatzoglou, F. H. Johnston, G. R. van der Werf, and M. Flannigan, “Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene,” Nat. Rev. Earth Environ., pp. 500–515, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. N. Wasserman and S. E. Mueller, “Climate influences on future fire severity: a synthesis of climate-fire interactions and impacts on fire regimes, high-severity fire, and forests in the western United States,” Fire Ecol., vol. 19, no. 43, 2023. [CrossRef]

- IPCC, “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,” Camb. Univ. Press, 2021.

- J. E. Halofsky, D. L. Peterson, and B. J. Harvey, “Changing wildfire, changing forests: the effects of climate change on fire regimes and vegetation in the Pacific Northwest, USA,” Fire Ecol, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Pausas and J. E. Keeley, “A burning story: The role of fire in the history of life.,” BioScience, vol. 59, no. 7, pp. 593–601, 2009. [CrossRef]

- B. Vannière, D. Colombaroli, E. Chapron, A. Leroux, W. Tinner, and M. Magny, “Climate versus human-driven fire regimes in Mediterranean landscapes: the Holocene record of Lago dell’Accesa (Tuscany, Italy),” Quat. Sci. Rev., vol. 27, pp. 1181–1196, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Camia. and G. Amatulli, “Weather Factors and Fire Danger in the Mediterranean. In: Chuvieco, E. (eds) Earth Observation of Wildland Fires in Mediterranean Ecosystems,” Springer Berl. Heidelb., 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Salesa, M. J. Baeza, and W. M. Santana, “Fire severity and prolonged drought do not interact to reduce plant regeneration capacity but alter community composition in a Mediterranean shrubland,” Santana, vol. 20, no. 61, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Tangney, R. Paroissien, T. Le Bret, and etal, “Success of post-fire plant recovery strategies varies with shifting fire seasonality,” Commun Earth Env., vol. 3, no. 126, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Xu, H. Chen, and etal, “Global patterns and drivers of post-fire vegetation productivity recovery,” Nat. Geosci., no. 17, pp. pages874-881, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Zahabnazouri, P. Wigand, and A. Jabbari, “Biogeomorphology of mega nebkha in the Fahraj Plain, Iran: Sensitive indicators of human activity and climate change,” Aeolian Res., vol. 49, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Shirzadi, M. Hosseinzadeh, K. Nosrati, S. M. Beyranvand, S. Zahabnazouri, and D. Capolongo, “An evaluation of sheet erosion using dendrogeomorphological methods on Quercus brantii roots in the northern catchment of Zarivar Lake (Western Iran).,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Linares and W. Ni Meister, “Impact of Wildfires on Land Surface Cold Season Climate in the Northern High-Latitudes: A Study on Changes in Vegetation, Snow Dynamics, Albedo, and Radiative Forcing,” Remote Sens., vol. 16, no. 8, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Sishodia, R. Ray, and S. K. Singh, “Applications of Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture: A Review,” Remote Sens., vol. 12, no. 19, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Neary, K. C. Ryan, and L. F. DeBano, “Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Soil and Water,” 2005. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- W. Qiang, Á. Moreno-Martínez, M.-M. Jordi, M. Campos-Taberner, and G. Camps-Valls, “Estimation of vegetation traits with kernel NDVI,” J. Photogramm. Remote Sens., vol. 195, pp. 408–417, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Nemani., C. D. Keeling, and H. Hashimoto, “Climate-driven increases in global terrestrial net primary production from 1982 to 1999,” vol. 300, pp. 1560–1563, 2003. [CrossRef]

- N. Pettorelli, The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. Oxford University Press, 2025.

- S. Goward, C. Tucker, and D. Dye, “North American vegetation patterns observed with the NOAA-7 advanced very high resolution radiometer,” Vegetatio, vol. 64, pp. 3–14, 1985. [CrossRef]

- L. Lopes, F. Dias, O. Fernandes, and etal, “A remote sensing assessment of oak forest recovery after postfire restoration,” Eur J For. Res, vol. 143, pp. 1000–1014, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hao., X. Xu, W. Fei, and L. Tan, “Long-Term Effects of Fire Severity and Climatic Factors on Post-Forest-Fire Vegetation Recovery,” Forests, vol. 13, no. 6, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Banskota, N. Kayastha, M. J. Falkowski, M. A. Wulder, R. E. Wulder, and J. C. White, “Forest Monitoring Using Landsat Time Series Data: A Review,” Can. J. Remote Sens., vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 362–384, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Van Gerrevink. and S. Veraverbeke, “Evaluating the Hyperspectral Sensitivity of the Differenced Normalized Burn Ratio for Assessing Fire Severity,” Remote Sens., vol. 13, no. 22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Escuin, R. Navarro, and P. Fernández, “Fire severity assessment by using NBR (Normalized Burn Ratio) and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) derived from LANDSAT TM/ETM images,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1053–1073, 2007. [CrossRef]

- P. Phinn and P. D. Erskine, “Fire Severity and Vegetation Recovery on Mine Site Rehabilitation Using WorldView-3 Imagery,” Fire, vol. 1, no. 2, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Morante-Carballo, L. Bravo-Montero, P. Carrión-Mero, A. Velastegui-Montoya, and E. Berrezueta, “26. Morante-Carballo,” Remote Sens., vol. 14, no. 8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao., Y. Huang, Y. Sun, G. Dong, Y. Li, and M. Ma, “Forest Fire Mapping Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study in Chongqing,” Remote Sens., vol. 15, no. 9, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Meng and F. Zhao, “Remote sensing of fire effects: A review for recent advances in burned area and burn severity mapping. In Remote Sensing of Hydrometeorological Hazards,” in Remote Sensing of Hydrometeorological Hazards, George P. Petropoulos, Tanvir Islam., Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

- s Vicario, m Adamo, D. Alcaraz-Segura, and C. Tarantino, “Bayesian Harmonic Modelling of Sparse and Irregular Satellite Remote Sensing Time Series of Vegetation Indexes: A Story of Clouds and Fires,” Remote Sens., vol. 12, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Forte, in Forte, Luigi. “Flora e vegetazione del bosco comunale “Difesa Grande” di Gravina in Puglia., 2001, pp. 183–228.

- R. P. Manicone, F. Mannerucci, N. Luisi, and p Lerario, “The Spontaneous Flora and Vegetation in Puglia in Science, Art and History". Bari,” Influ. Environ. Anthropog. Factors Decay Oak For. South. Italy Conf. Proc., pp. 163–171, 1993.

- Kapur, P. Steduto, and T. Mladen, “Prediction of climatic change for the next 100 years in Southern Italy,” Ital. J. Agron., vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 365–371, 2007. [CrossRef]

- “https://www.meteoblue.com/,” Climate change. [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, E. Velizarova, and L. Filchev, “Post-Fire Forest Vegetation State Monitoring through Satellite Remote Sensing and In Situ Data,” Remote Sens., vol. 14, no. 24, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar, A. Sharma, and A. Kumar Thukral, Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ., 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Anke, A. Sharma, R. BhMcKennaardwaj, and A. Kumar Thukral, “Comparison of different reflectance indices for vegetation analysis using Landsat-TM data,” Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ., vol. 12, pp. 70–77, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Tamiminia, B. Salehi, M. Mahdianpari, L. Quackenbush, S. Adeli, and B. Brisco, “Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review,” Photogramm. Remote Sens, vol. 164, pp. 152–170, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shafeian, B. J. Mood, K. W. Belcher, and C. P. Laroque, “Assessing spatial distribution and quantification of native trees in Saskatchewan’s prairie landscape using remote sensing techniques,” Eur. J. Remote Sens., vol. 58, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Mohammad et al., “Estimation of agricultural burned affected area using NDVI and NBR satellite-based empirical models,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 343, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Llorens, J. Antonio Sobrino, C. Fernández, J. M. Fernández-Alonso, and J. Antonio Vega, “A methodology to estimate forest fires burned areas and burn severity degrees using Sentinel-2 data. Application to the October 2017 fires in the Iberian Peninsula,” Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation, vol. 95. [CrossRef]

- Alcaras, D. Costantino, F. Guastaferro, C. Parente, and M. Pepe, “Normalized Burn Ratio Plus (NBR+): A New Index for Sentinel-2 Imagery,” Remote Sens., vol. 14, no. 1727, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. B. Leigh et al., “Post-fire burn severity and vegetation response following eight large wildfires across the Western United States,” Fire Ecol., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 91–108, 2007.

- C. Teodoro and S. Amaral, “Algorithms for change detection using NIR and SWIR spectral areas: Assessing post-fire vegetation and canopy moisture loss,” J. Appl. Remote Sens., vol. 13, no. 4, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Key and N. C. Benson, “Landscape Assessment: Ground measure of severity, the Composite Burn Index; and Remote sensing of severity, the Normalized Burn Ratio,” Ogden, UT, Report RMRS-GTR-164-CD: LA 1-51, 2006. [Online]. Available: https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/2002085.

- R. Llorens, J. A. Sobrino, C. Fernández, J. M. Fernández-Alonso, and J. A. Vega, “A methodology to estimate forest fires burned areas and burn severity degrees using Sentinel-2 data. Application to the October 2017 fires in the Iberian Peninsula,” Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf, vol. 95, no. 102243, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Jones and R. Vaughan, “Understanding NDVI values: implications for vegetation assessment,” J. Remote Sens., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 123–135, 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. Keeley, “Fire intensity, fire severity and burn severity: a brief review and suggested usage,” Nternational J. Wildland Fire, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 116–126, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Morante-Carballo, L. Bravo-Montero, P. Carrión-Mero, A. Velastegui-Montoya, and E. Berrezueta, “Forest fire assessment using remote sensing to support the development of an action plan proposal in Ecuador,” p. 1783, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Eidenshink, B. Schwind, K. Brewer, Z. Zhu, B. Quayle, and S. Howard, Fire Ecol., vol. 3, no. 3, 2007. [CrossRef]

- B. C. Bright, A. T. Hudak, R. E. Kennedy, J. D. Braaten, and A. Henareh Khalyani, “Examining post-fire vegetation recovery with Landsat time series analysis in three western North American forest types,” Fire Ecol., vol. 15, no. 8, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Lai and T. Oguchi, “Evaluating Spatiotemporal Patterns of Post-Eruption Vegetation Recovery at Unzen Volcano, Japan, from Landsat Time Series,” Remote Sens., vol. 14, no. 21, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Bowd et al., “Direct and indirect effects of fire on microbial communities in a pyrodiverse dry-sclerophyll forest,” J. Ecol., vol. 110, no. 7, pp. 1687–1703, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Wolf, P. E. Higuera, K. T. Davis, and S. Z. Dobrowski, “Wildfire impacts on forest microclimate vary with biophysical context,” Ecosphere, vol. 12, no. 5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Chu, X. Guo, and K. Takeda, “Effects of Burn Severity and Environmental Conditions on Post-Fire Regeneration in Siberian Larch Forest,” Forests, vol. 8, no. 3, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Escuin, R. Navarro, and P. Fernández, “Fire severity assessment by using NBR (Normalized Burn Ratio) and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) derived from LANDSAT TM/ETM images,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1053–1073, 2007. [CrossRef]

- B. Hao, X. Xu, F. Wu, and L. Tan, “Long-Term Effects of Fire Severity and Climatic Factors on Post-Forest-Fire Vegetation Recovery,” Forests, vol. 13, no. 6, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. V. Jo Celebrezzee, M. C. Franz, R. A. Andrus, A. T. Stahl, M. Steen-Adams, and A. J. H. Meddens, “A fast spectral recovery does not necessarily indicate post-fire forest recovery.,” Fire Ecol., vol. 20, no. 54, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Johnstone, F. S. Chapin, J. Foote, S. Kemmett, K. Price, and L. Viereck, “Decadal observations of tree regeneration following fire in boreal forests,” Ecol. Monogr., vol. 80, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2016.

- C. Certini, “Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: a review,” Oecologia, vol. 143, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2005.

- V. H. Dale, L. A. Joyce, S. McNulty, and R. P. Neilson, “Climate change and forest disturbances,” BioScience, vol. 51, no. 9, pp. 723–734, 2001.

- R. A. Shakesby and S. H. Doerr, “Wildfire as a hydrological and geomorphological agent,” Earth-Sci. Rev., vol. 74, no. 3–4, pp. 269–307, 2006.

- S. L. Stephens et al., “Managing forests and fire in changing climates,” Science, vol. 342, no. 6154, pp. 41–42, 2013.

- M. North, B. M. Collins, and H. D. Safford, “Resilience of forest ecosystems to climate change,” US Dep. Agric. For. Serv., 2015.

- E. Carrari, P. Biagini, and F. Selvi, “Early vegetation recovery of a burned Mediterranean forest in relation to post-fire management strategies,” Int. J. For. Res., vol. 95, no. 4, pp. 548–561, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Peris-Llopis, M. Vastaranta, N. Saarinen, J. Ramon, G. Olabarria, and B. Mola-Yudego, “Post-fire vegetation dynamics and location as main drivers of fire recurrence in Mediterranean forests,” For. Ecol. Manag., vol. 568. [CrossRef]

| Fire | Date | AREA (ha) |

|---|---|---|

| Bosco Difesa Grande | 23/07/2007 | 372.47 |

| Bosco Difesa Grande - Rifessa Pantone | 12/7/2010 | 0.39 |

| Bosco Difesa Grande - Rifessa Pantone | 12/7/2010 | 0.918 |

| Bosco Comunale | 25/06/2011 | 1.63 |

| Bosco Comunale Difesa Grande | 29/06/2011 | 19.93 |

| Bosco Comunale Difesa Grande | 10/7/2011 | 27.80 |

| Bosco Comunale Difesa Grande | 30/06/2012 | 12.95 |

| Bosco Comunale Difesa Grande | 30/06/2012 | 16.34 |

| Bosco Difesa Grande | 15/08/2013 | 7.14 |

| Difesa Grande | 12/8/2017 | 24.13 |

| Difesa Grande | 12/8/2017 | 44.30 |

| Difesa Grande | 12/8/2017 | 1240.25 |

| Difesa Grande | 28/07/2021 | 935.67 |

| Index | Name | Equations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBR | Normalized Burn Ratio | (NIR- SWIR)/(NIR + SWIR) NBR = (B08 – B12)/(B08 + B12) |

Keeley, J. E. 2009 |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | (NIR−RED)/(NIR+RED) | Rouse et al. 1973 |

| dNBR | Differenced Normalized Burn Ratio | dNBR = NBRpre-fire − NBRpost-fire | Key& Benson. 2006 |

| dNDVI | Differenced Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | dNDVI = NDVIpre-fire − NDVIpost-fire | Escuin et al, 2007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).