Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

- Global trends in embodied carbon and life cycle assessment methodologies;

- Material-level impact studies (e.g., concrete, steel, insulation);

- Prior approaches to material ranking, classification, and prioritization;

- The integration of LCA into green building certifications and policy mechanisms.

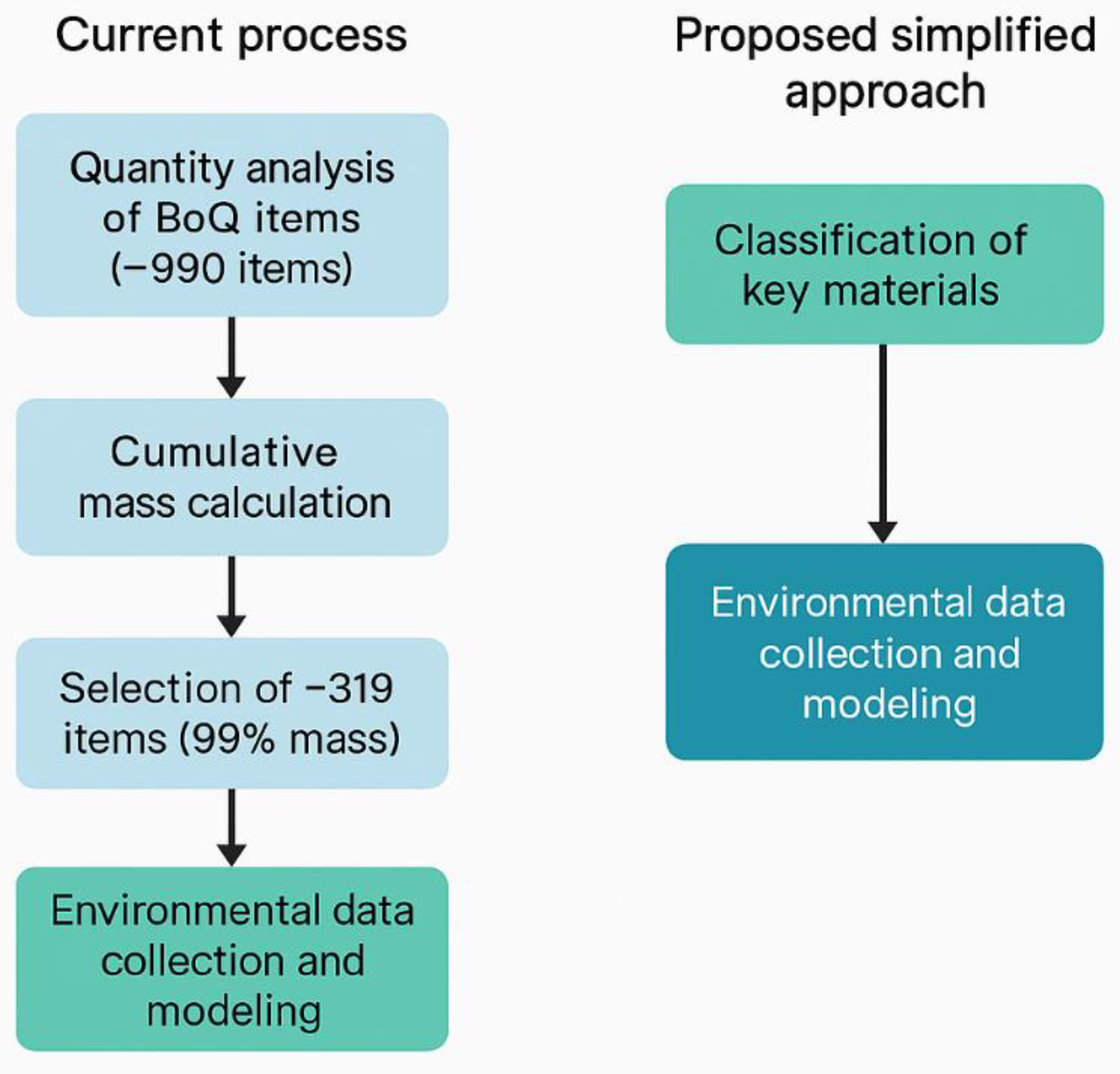

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

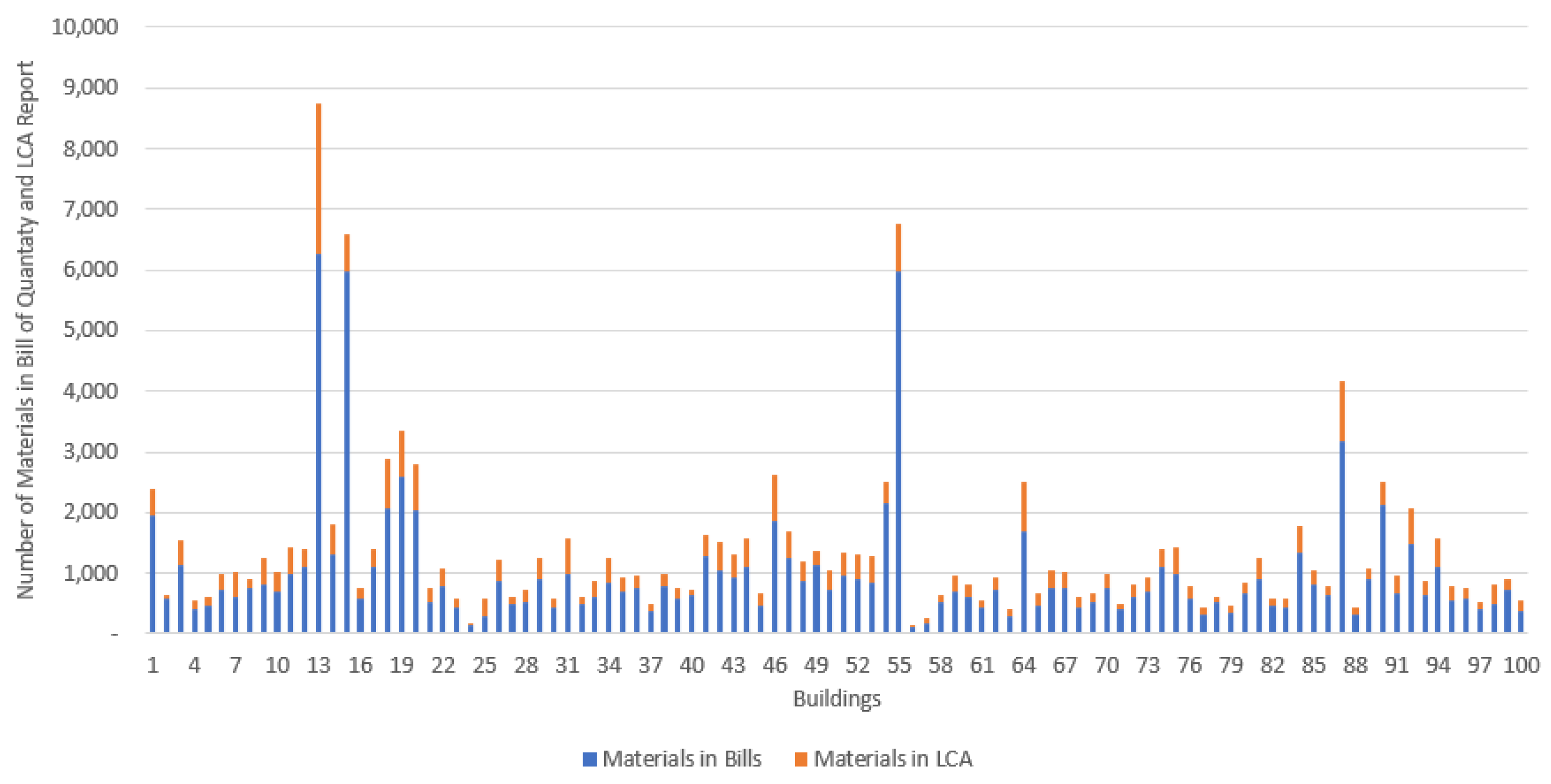

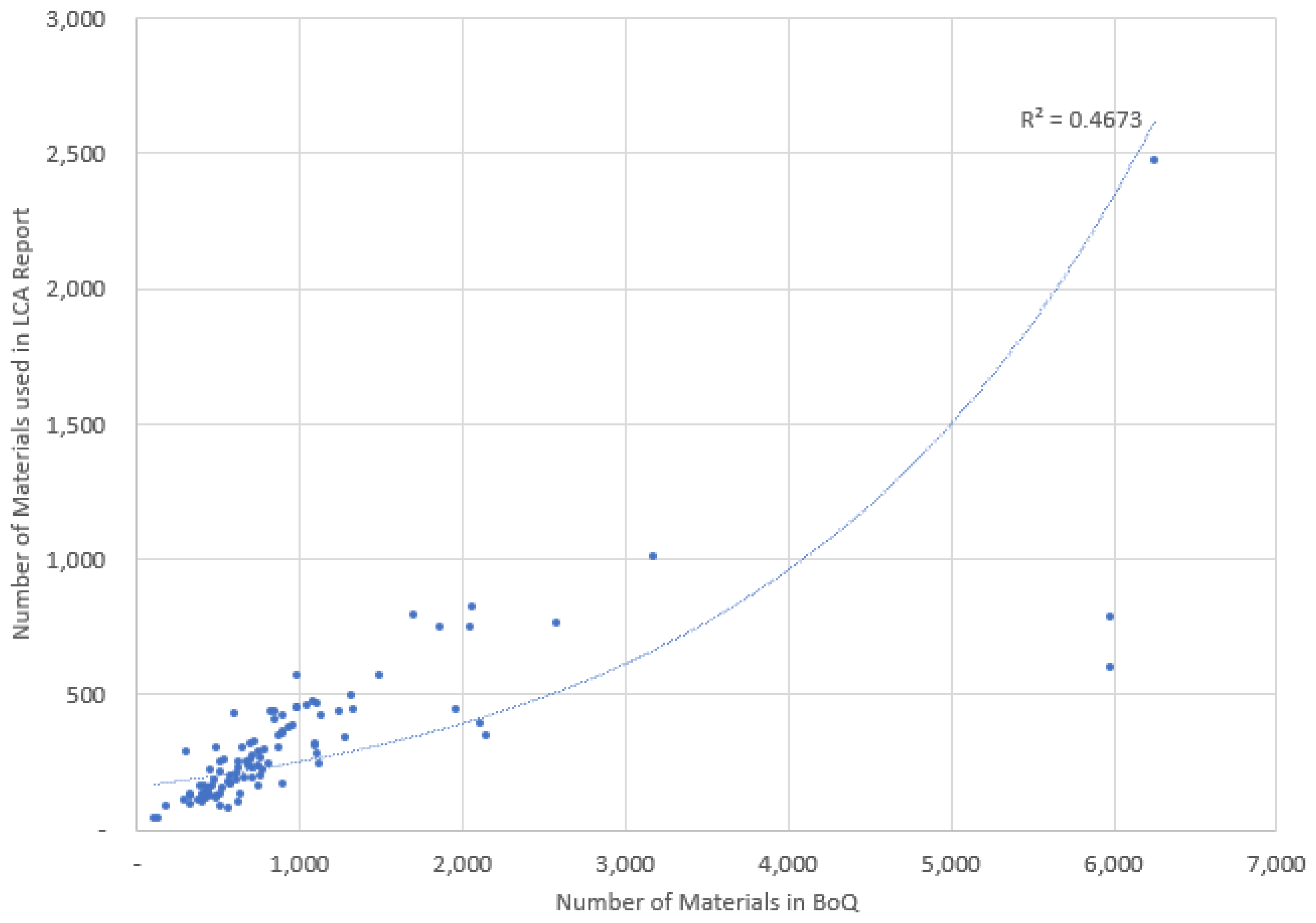

- Bill of Quantities (BoQ) Review: Each report’s BoQ was examined to determine the total number of materials listed.

- Mass Contribution Calculation: For material group, the percentage contribution to the total mass was computed.

- Material Ranking: Materials were ranked based on their frequency of occurrence across projects, cumulative mass contribution, and relative carbon impact potential.

- Classification Framework: Materials were grouped into 12 categories based on their functional roles and potential integration into certification systems.

3. Literature Review

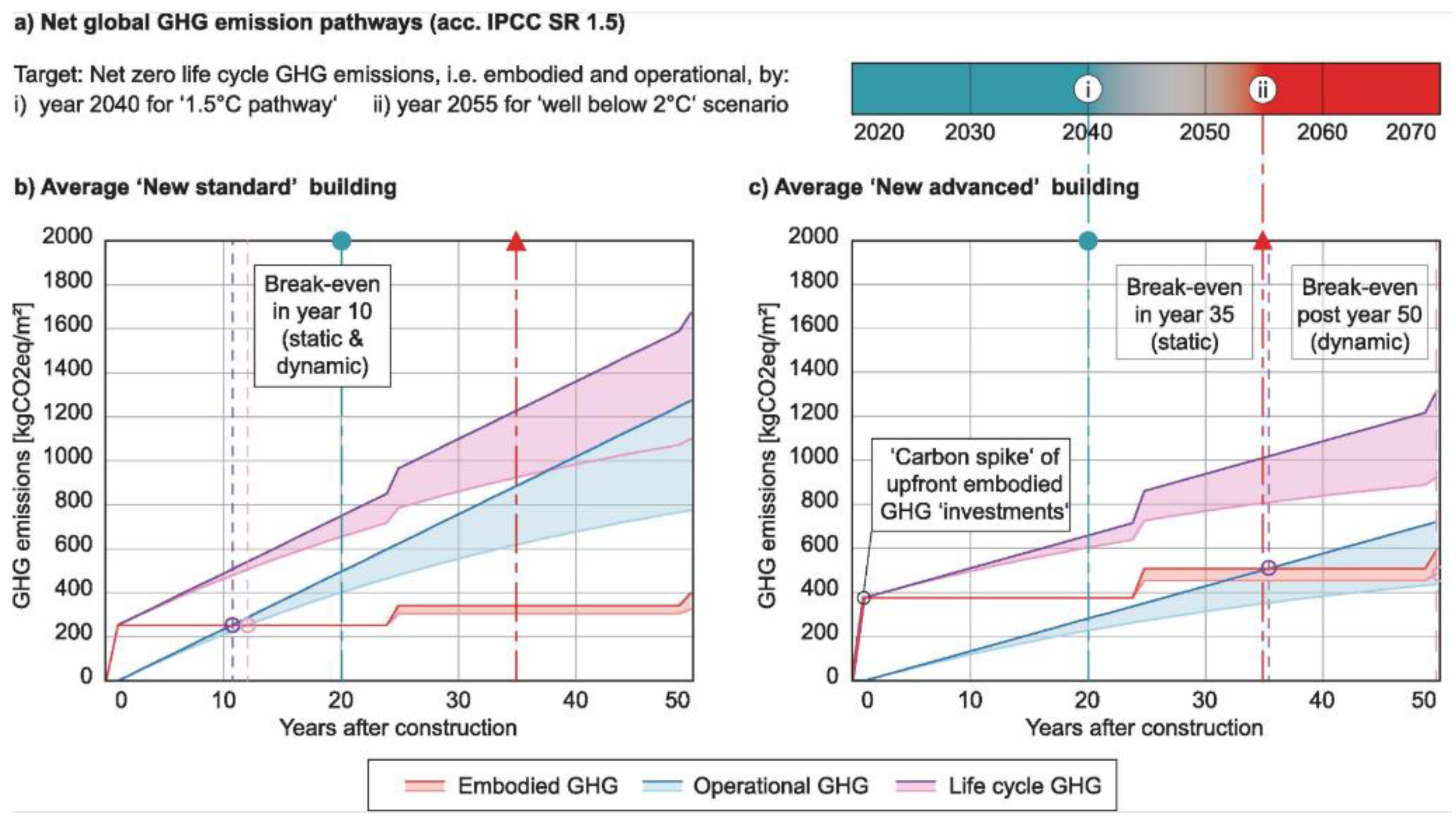

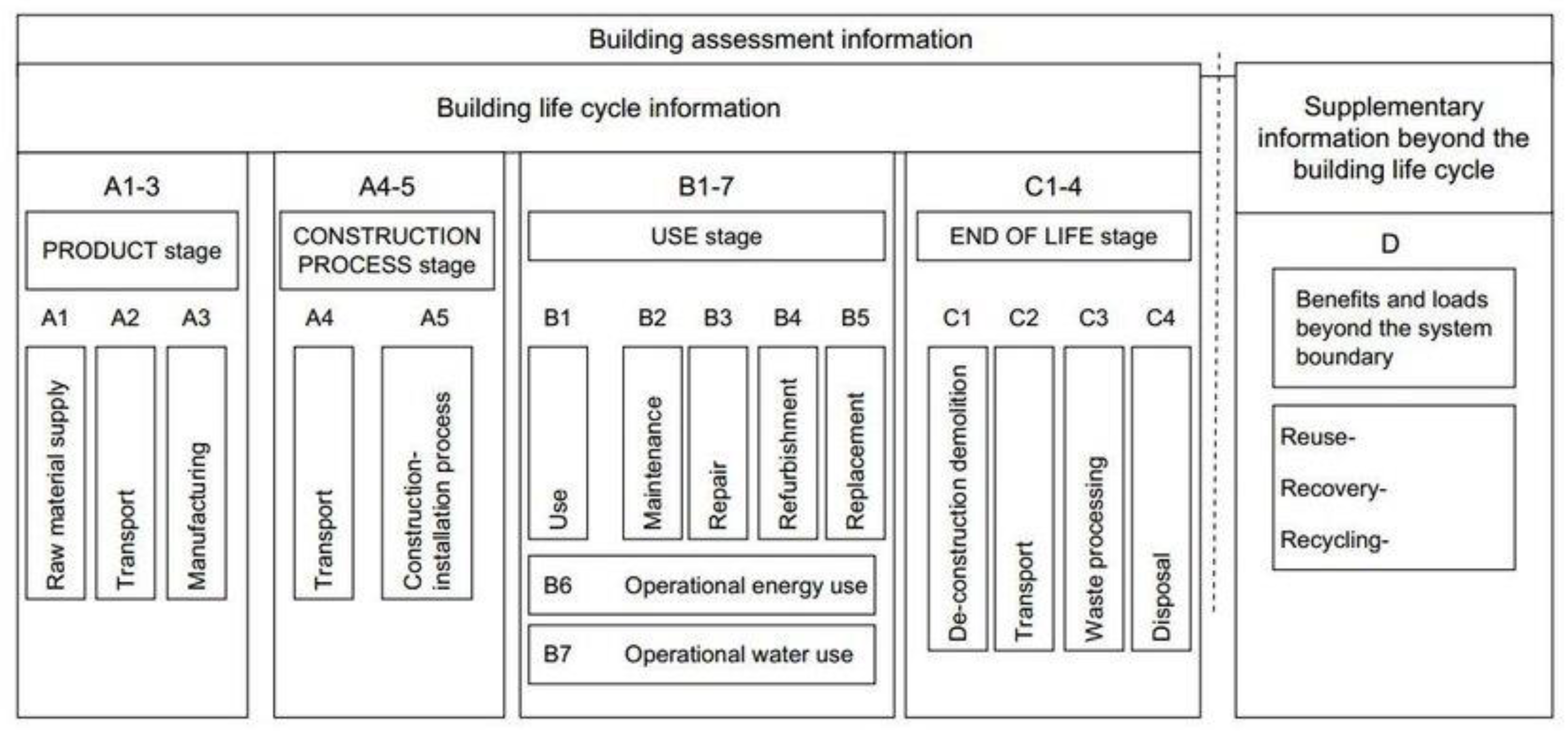

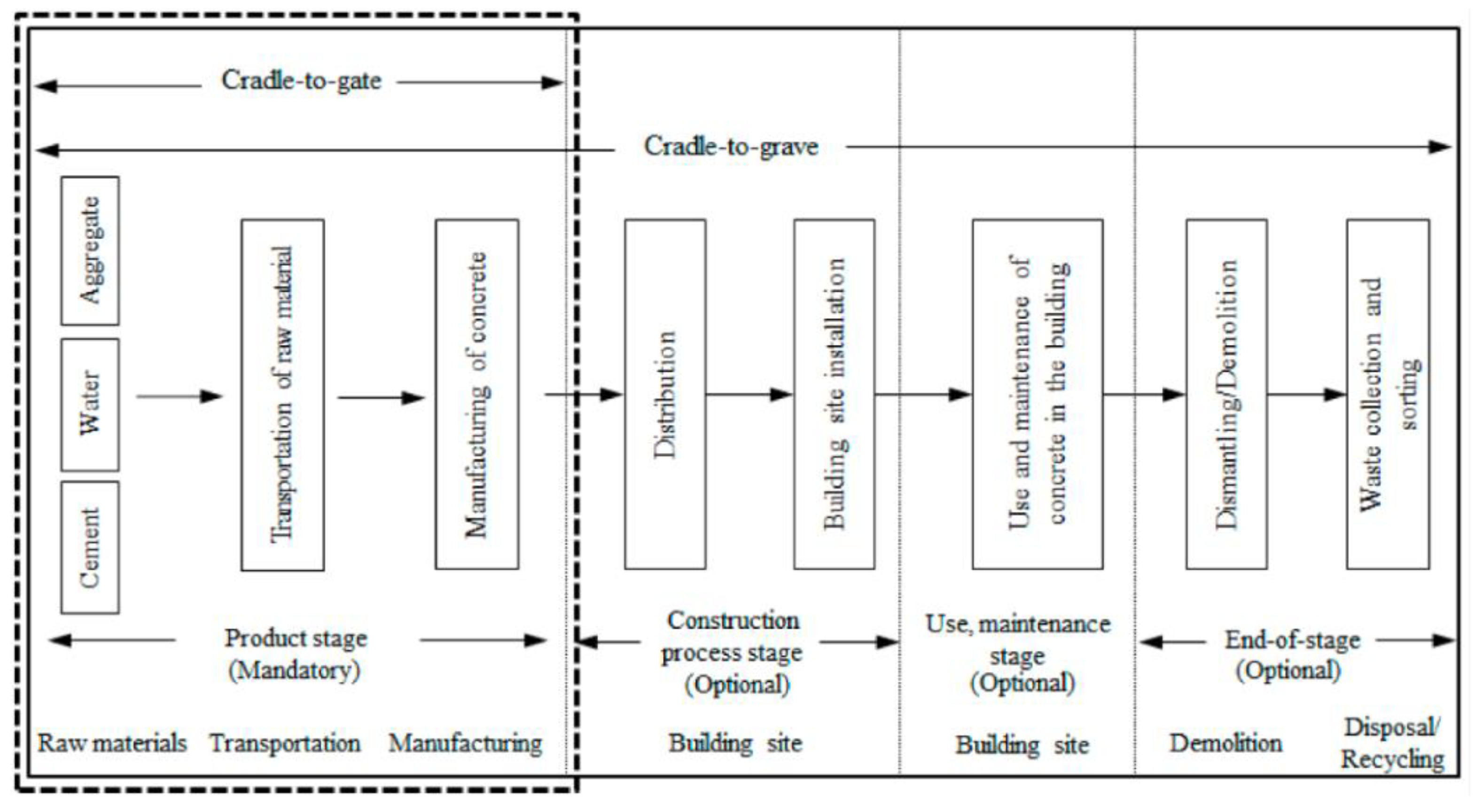

3.1. Overview of LCA in Buildings

3.2. Embodied Carbon and Material Contributions

3.3. Material Classification and Prioritization

3.4. Role of LCA in Certification and Policy

3.5. Practical Challenges in LCA implementation

3.6. National Context and Research Contribution

4. Data Collection and Analysis Result

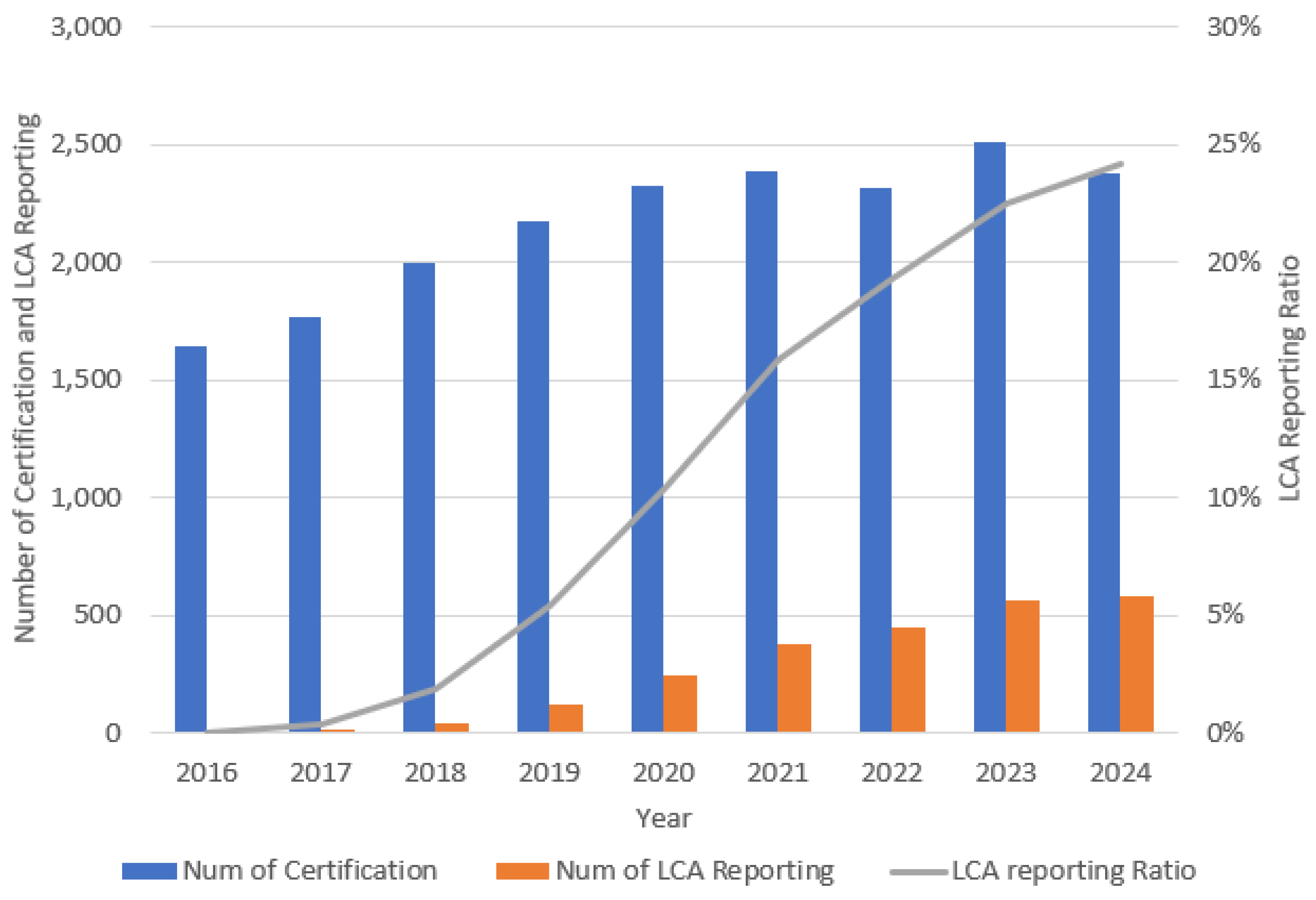

4.1. Status of Green Building Certification and Life Cycle Assessment Reports in Korea

4.2. LCA Data Analysis

4.3. Quantity Breakdown in LCA

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Barriers to LCA Implementation

5.2. Dominance of Key Material Categories

5.3. Implication for G-SEED and Global Certification Frameworks

5.4. Policy and Industry Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| G-SEED | Green Standard for Energy and Environmental Design |

| GHG | Green House Gas |

| LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| DGNB | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen |

| BoQ | Bill of Quantities |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

Appendix A. Detail Information of 100 LCA Projects

| 9 | Structure type | Gross Floor Area | Number of Materials in Bills of Quantity | Number of Materials used in LCA Reporting | Reporting Ratio |

| R1 | RC | 3,881 | 1,958 | 444 | 22.68% |

| R2 | RC | 4,240 | 567 | 82 | 14.46% |

| R3 | RC | 7,919 | 1,129 | 424 | 37.56% |

| R4 | RC | 8,689 | 405 | 132 | 32.59% |

| R5 | RC | 11,793 | 464 | 158 | 34.05% |

| R6 | RC | 18,918 | 717 | 273 | 38.08% |

| R7 | RC | 35,128 | 601 | 426 | 70.88% |

| R8 | RC | 40,330 | 750 | 160 | 21.33% |

| R9 | RC | 42,725 | 821 | 438 | 53.35% |

| R10 | RC | 44,925 | 702 | 316 | 45.01% |

| R11 | RC | 48,073 | 985 | 453 | 45.99% |

| R12 | RC | 68,601 | 1,093 | 313 | 28.64% |

| R13 | RC | 97,490 | 6,259 | 2,473 | 39.51% |

| R14 | RC | 111,278 | 1,317 | 495 | 37.59% |

| R15 | RC | 180,254 | 5,984 | 602 | 10.06% |

| R16 | RC | 181,976 | 570 | 175 | 30.70% |

| R17 | RC | 292,294 | 1,093 | 306 | 28.00% |

| R18 | RC | 466,221 | 2,056 | 825 | 40.13% |

| R19 | RC | 70,872 | 2,582 | 762 | 29.51% |

| R20 | RC | 86,905 | 2,047 | 750 | 36.64% |

| Non-R1 | SRC | 2,218 | 110 | 38 | 34.55% |

| Non-R2 | RC | 2,307 | 180 | 86 | 47.78% |

| Non-R3 | SRC | 3,058 | 515 | 132 | 25.63% |

| Non-R4 | SRC | 3,666 | 697 | 255 | 36.59% |

| Non-R5 | RC | 5,196 | 609 | 207 | 33.99% |

| Non-R6 | RC | 5,296 | 434 | 116 | 26.73% |

| Non-R7 | RC | 6,039 | 711 | 224 | 31.50% |

| Non-R8 | SRC | 6,110 | 295 | 111 | 37.63% |

| Non-R9 | RC | 6,529 | 1,702 | 796 | 46.77% |

| Non-R10 | RC | 6,529 | 473 | 182 | 38.48% |

| Non-R11 | SRC | 6,691 | 747 | 290 | 38.82% |

| Non-R12 | SRC | 6,876 | 769 | 261 | 33.94% |

| Non-R13 | RC | 7,022 | 444 | 153 | 34.46% |

| Non-R14 | RC | 7,198 | 523 | 150 | 28.68% |

| Non-R15 | SRC | 7,225 | 751 | 232 | 30.89% |

| Non-R16 | RC | 7,450 | 399 | 104 | 26.07% |

| Non-R17 | SRC | 8,029 | 617 | 182 | 29.50% |

| Non-R18 | RC | 8,592 | 693 | 236 | 34.05% |

| Non-R19 | RC | 15,155 | 1,105 | 278 | 25.16% |

| Non-R20 | SRC | 15,258 | 981 | 448 | 45.67% |

| Non-R21 | RC | 17,621 | 572 | 199 | 34.79% |

| Non-R22 | RC | 19,680 | 328 | 95 | 28.96% |

| Non-R23 | RC | 20,099 | 522 | 89 | 17.05% |

| Non-R24 | SRC | 22,126 | 333 | 133 | 39.94% |

| Non-R25 | RC | 28,104 | 663 | 191 | 28.81% |

| Non-R26 | SRC | 32,635 | 897 | 350 | 39.02% |

| Non-R27 | SRC | 36,501 | 451 | 122 | 27.05% |

| Non-R28 | RC | 40,476 | 437 | 136 | 31.12% |

| Non-R29 | RC | 55,391 | 1,327 | 443 | 33.38% |

| Non-R30 | SRC | 55,887 | 817 | 241 | 29.50% |

| Non-R31 | RC | 56,633 | 638 | 134 | 21.00% |

| Non-R32 | RC | 57,559 | 3,171 | 1,009 | 31.82% |

| Non-R33 | RC | 59,402 | 326 | 121 | 37.12% |

| Non-R34 | RC | 70,628 | 896 | 168 | 18.75% |

| Non-R35 | SRC | 130,144 | 2,116 | 393 | 18.57% |

| Non-R36 | RC | 205,243 | 658 | 298 | 45.29% |

| Non-R37 | RC | 216,096 | 1,495 | 568 | 37.99% |

| Non-R38 | RC | 259,223 | 632 | 228 | 36.08% |

| Office1 | RC | 3,677 | 433 | 138 | 31.87% |

| Office2 | RC | 4,078 | 128 | 44 | 34.38% |

| Office3 | RC | 4,243 | 302 | 285 | 94.37% |

| Office4 | SRC | 4,449 | 878 | 345 | 39.29% |

| Office5 | RC | 4,993 | 489 | 118 | 24.13% |

| Office6 | RC | 5,601 | 514 | 209 | 40.66% |

| Office7 | RC | 5,757 | 897 | 363 | 40.47% |

| Office8 | RC | 8,904 | 423 | 162 | 38.30% |

| Office9 | RC | 9,467 | 986 | 572 | 58.01% |

| Office10 | RC | 10,103 | 487 | 120 | 24.64% |

| Office11 | RC | 11,466 | 623 | 247 | 39.65% |

| Office12 | RC | 13,019 | 849 | 408 | 48.06% |

| Office13 | RC | 15,328 | 682 | 250 | 36.66% |

| Office14 | RC | 17,226 | 759 | 198 | 26.09% |

| Office15 | RC | 17,881 | 374 | 111 | 29.68% |

| Office16 | RC | 18,601 | 779 | 222 | 28.50% |

| Office17 | RC | 18,945 | 580 | 164 | 28.28% |

| Office18 | RC | 19,171 | 626 | 103 | 16.45% |

| Office19 | RC | 21,554 | 1,285 | 341 | 26.54% |

| Office20 | RC | 21,736 | 1,043 | 456 | 43.72% |

| Office21 | RC | 25,653 | 941 | 377 | 40.06% |

| Office22 | RC | 25,694 | 1,091 | 469 | 42.99% |

| Office23 | RC | 25,950 | 457 | 221 | 48.36% |

| Office24 | SRC | 31,785 | 1,861 | 748 | 40.19% |

| Office25 | SRC | 33,420 | 1,242 | 433 | 34.86% |

| Office26 | RC | 38,361 | 880 | 305 | 34.66% |

| Office27 | SRC | 41,723 | 1,120 | 240 | 21.43% |

| Office28 | RC | 44,991 | 728 | 321 | 44.09% |

| Office29 | RC | 47,919 | 959 | 381 | 39.73% |

| Office30 | RC | 53,705 | 902 | 417 | 46.23% |

| Office31 | RC | 58,089 | 854 | 434 | 50.82% |

| Office32 | SRC | 197,057 | 2,145 | 345 | 16.08% |

| Office33 | SRC | 302,472 | 5,984 | 784 | 13.10% |

| School1 | RC | 8,941 | 537 | 259 | 48.23% |

| School2 | SRC | 9,657 | 577 | 165 | 28.60% |

| School3 | SRC | 17,261 | 406 | 114 | 28.08% |

| School4 | RC | 18,724 | 494 | 305 | 61.74% |

| School5 | RC | 30,380 | 715 | 190 | 26.57% |

| School6 | SRC | 61,464 | 387 | 161 | 41.60% |

| Hotel1 | RC | 10,890 | 519 | 248 | 47.78% |

| Hotel2 | RC | 14,740 | 791 | 296 | 37.42% |

| Retail | SRC | 125,563 | 1,114 | 464 | 41.65% |

| Average | - | 48,030 | 990 | 319 | 35.24% |

| *R: Residential building, Non-R: Non-residential building. | |||||

Appendix B. Detail Quantity of Major Construction Components

| Building Type | Number of Major Components | Quantity of Major Construction Components in LCA Building (ton) | |||||||||||

| Concrete | Structural Steel | Metal Finish | Cement & Brick | Wood | Glass | Insulation | Gypsum | Sand & Gravel | Stone Material | Tiles | Paint & Cover | ||

| R1 | 7 | 11,550.6 | 627.4 | - | 629.0 | - | - | 3.0 | 72.7 | 160.0 | 273.9 | - | - |

| R2 | 8 | 10,419.6 | 379.2 | - | 212.0 | - | 160.0 | 33.2 | 84.5 | 636.4 | 148.6 | - | - |

| R3 | 7 | 19,798.4 | 915.6 | - | 1,444.2 | - | 85.7 | 115.5 | - | 654.4 | 115.3 | - | - |

| R4 | 6 | 26,949.1 | 1,298.8 | - | 631.9 | - | - | 130.3 | - | 848.0 | 588.4 | - | - |

| R5 | 7 | 24,603.1 | 1,054.7 | - | 3,324.6 | - | - | 246.0 | 162.1 | 193.6 | 262.9 | - | - |

| R6 | 8 | 45,047.8 | 1,697.0 | - | 4,166.8 | - | - | 429.8 | 171.9 | 3,127.0 | 277.5 | 144.7 | - |

| R7 | 5 | 44,584.1 | 1,420.6 | - | 3,470.1 | - | - | 122.2 | - | 5,018.0 | - | - | - |

| R8 | 8 | 66,019.6 | 2,710.9 | - | 5,476.0 | - | 272.4 | 185.5 | 741.8 | 2,270.4 | - | 326.8 | - |

| R9 | 6 | 106,936.2 | 3,047.0 | - | 3,297.0 | - | - | 139.2 | 477.6 | 2,775.9 | - | - | - |

| R10 | 6 | 117,832.7 | 4,608.4 | - | 5,737.6 | - | - | 49.9 | 515.3 | 8,566.3 | - | - | - |

| R11 | 7 | 103,184.2 | 5,358.6 | - | 7,000.8 | - | 350.1 | 114.7 | 427.5 | 2,298.1 | - | - | - |

| R12 | 7 | 131,556.2 | 4,010.5 | - | 14,148.6 | - | - | 165.7 | 974.5 | 8,616.0 | 813.3 | - | - |

| R13 | 8 | 216,451.9 | 7,411.4 | - | 12,819.0 | 643.7 | 711.8 | 302.1 | - | 1,504.5 | 1,408.2 | - | - |

| R14 | 8 | 268,557.2 | 9,030.0 | - | 24,973.0 | 281.5 | 983.1 | 2,354.4 | - | 6,915.2 | - | 1,302.2 | - |

| R15 | 6 | 412,359.1 | 13,917.4 | - | 26,788.0 | - | - | 518.5 | 1,607.6 | 22,974.8 | - | - | - |

| R16 | 7 | 409,249.9 | 13,770.6 | - | 24,153.5 | - | 3,008.8 | 507.6 | - | 11,779.7 | 1,886.3 | - | - |

| R17 | 6 | 542,944.9 | 24,678.0 | - | 79,196.1 | - | 3,627.5 | 536.2 | - | 11,951.3 | - | - | - |

| R18 | 8 | 869,306.9 | 28,692.0 | - | 82,918.1 | - | - | 546.9 | 4,498.9 | 13,686.4 | 27,523.5 | 4,033.1 | - |

| R19 | 8 | 21,044.1 | 1,180.2 | - | 1,206.5 | - | 129.2 | 72.0 | 203.1 | 341.2 | - | 150.4 | - |

| R20 | 6 | 42,638.3 | 1,992.5 | - | 3,106.8 | - | - | 267.6 | - | 2,073.6 | 398.0 | 156.2 | - |

| Non-R1 | 5 | 7,054.2 | 447.4 | 43.7 | 456.5 | - | - | 34.4 | 47.5 | 244.2 | 38.0 | - | - |

| Non-R2 | 6 | 8,823.5 | 409.4 | 46.1 | 345.1 | - | 31.2 | 45.9 | 73.0 | 1,212.7 | 440.7 | - | - |

| Non-R3 | 8 | 11,168.8 | 495.6 | - | 717.4 | - | - | 31.8 | 56.9 | 800.8 | 214.0 | - | - |

| Non-R4 | 9 | 11,824.3 | 552.2 | - | 1,392.3 | - | 37.7 | 14.1 | - | 576.0 | 42.2 | 44.9 | - |

| Non-R5 | 7 | 12,472.9 | 743.9 | - | 410.5 | - | - | 41.2 | 75.6 | 468.8 | 263.6 | - | - |

| Non-R6 | 8 | 14,768.3 | 837.2 | - | 655.5 | - | - | 22.0 | - | 317.4 | - | - | - |

| Non-R7 | 7 | 35,229.1 | 2,785.2 | 408.9 | 464.0 | - | - | 195.2 | - | 278.9 | - | - | - |

| Non-R8 | 5 | 12,263.6 | 925.1 | 179.6 | 217.8 | - | - | 67.4 | 223.1 | 116.6 | - | - | - |

| Non-R9 | 6 | 18,593.2 | 2,309.8 | 216.6 | 1,184.5 | - | 303.1 | 36.0 | - | 920.0 | 261.4 | - | - |

| Non-R10 | 7 | 14,277.9 | 1,230.6 | 164.6 | 497.3 | - | 52.4 | 45.5 | 66.7 | 304.6 | 316.7 | - | - |

| Non-R11 | 8 | 16,353.2 | 911.3 | - | 1,161.1 | - | 68.9 | 26.3 | - | 869.7 | 438.3 | - | - |

| Non-R12 | 9 | 15,963.9 | 797.3 | 98.5 | 637.5 | - | 103.7 | 51.7 | 70.9 | 594.4 | 216.0 | - | - |

| Non-R13 | 7 | 27,460.6 | 1,325.9 | - | 2,196.3 | - | - | 61.4 | 94.7 | 915.2 | 128.7 | - | - |

| Non-R14 | 9 | 12,826.1 | 501.3 | 76.2 | 1,968.2 | - | - | 22.5 | - | 2,779.8 | 72.2 | - | - |

| Non-R15 | 7 | 15,262.2 | 931.9 | - | 1,184.0 | - | 60.2 | 72.3 | 44.9 | 203.6 | - | 49.2 | - |

| Non-R16 | 7 | 21,953.5 | 1,094.1 | - | 1,241.8 | - | - | 38.4 | - | 1,043.0 | 145.8 | - | - |

| Non-R17 | 8 | 30,581.4 | 1,803.7 | 222.9 | 1,554.5 | - | - | 27.2 | 205.4 | 1,451.0 | 466.9 | - | - |

| Non-R18 | 6 | 20,902.6 | 2,394.1 | 344.6 | 527.0 | - | 237.9 | 80.3 | 631.3 | 543.8 | - | 108.1 | - |

| Non-R19 | 8 | 54,409.8 | 2,724.1 | 268.0 | 1,853.5 | - | 134.3 | 94.6 | 300.5 | 1,596.8 | 907.3 | - | - |

| Non-R20 | 9 | 45,001.8 | 1,964.7 | - | 2,841.5 | - | 589.3 | 45.1 | - | 1,507.2 | - | 151.6 | - |

| Non-R21 | 9 | 43,828.0 | 1,992.0 | - | 828.4 | - | 267.6 | 42.0 | - | - | 189.6 | - | - |

| Non-R22 | 7 | 47,842.3 | 3,489.4 | 727.3 | 1,230.2 | - | - | 51.4 | 229.7 | 2,149.4 | 644.6 | 226.9 | - |

| Non-R23 | 6 | 48,619.7 | 2,203.3 | 154.1 | 2,692.2 | - | 652.8 | 85.9 | 177.3 | 2,052.8 | - | - | - |

| Non-R24 | 9 | 35,431.5 | 10,630.2 | 9,690.3 | - | - | - | 180.3 | 210.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Non-R25 | 8 | 56,449.0 | 2,938.1 | - | 16,758.5 | - | 422.8 | 33.2 | 604.3 | 1,176.9 | - | - | - |

| Non-R26 | 5 | 135,944.0 | 5,755.1 | - | 1,553.2 | - | 774.4 | 76.2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Non-R27 | 7 | 107,169.5 | 6,978.1 | 627.7 | 5,702.3 | - | 1,191.4 | 131.6 | 1,131.0 | - | - | 645.3 | - |

| Non-R28 | 5 | 103,074.5 | 7,067.0 | 584.7 | 3,274.0 | - | 593.1 | 216.5 | 1,640.9 | 2,714.2 | - | 2,712.3 | - |

| Non-R29 | 8 | 132,595.0 | 5,895.5 | - | 3,290.1 | - | 939.9 | 361.3 | - | 1,705.6 | 1,106.6 | - | - |

| Non-R30 | 9 | 108,638.2 | 5,625.1 | 704.6 | 6,960.6 | - | 523.1 | 349.2 | 1,286.7 | 1,460.6 | 1,287.0 | - | - |

| Non-R31 | 7 | 106,763.7 | 4,619.6 | - | 4,035.6 | - | 461.2 | 123.6 | 1,115.7 | 1,064.0 | - | - | - |

| Non-R32 | 9 | 113,287.6 | 5,595.1 | 485.5 | 4,547.9 | - | 998.3 | 192.6 | 946.3 | 5,569.8 | - | - | - |

| Non-R33 | 7 | 732,707.5 | 27,328.7 | 7,758.8 | 6,647.4 | - | 150.5 | 321.2 | 516.1 | 3,284.0 | 273.7 | 92.8 | 220.4 |

| Non-R34 | 8 | 274,087.3 | 11,228.3 | 2,576.6 | 21,412.3 | - | 2,783.1 | 198.0 | - | 11,253.6 | 4,311.9 | - | - |

| Non-R35 | 11 | 362,299.6 | 16,355.9 | 2,164.4 | 26,466.6 | - | 3,504.6 | 396.4 | 2,649.8 | - | 2,276.1 | - | - |

| Non-R36 | 8 | 430,010.4 | 14,272.2 | - | 22,665.4 | - | 2,496.1 | 661.7 | 1,557.1 | 10,345.6 | 3,770.5 | - | - |

| Non-R37 | 8 | 174,096.0 | 4,757.5 | - | 16,766.6 | - | - | 458.2 | 1,071.3 | 1,092.5 | 1,492.2 | 577.7 | - |

| Non-R38 | 8 | 285,569.5 | 17,882.7 | - | 9,675.2 | - | - | 464.7 | - | 9,514.2 | - | 684.2 | - |

| Office1 | 7 | 10,591.5 | 513.2 | - | 151.3 | - | 33.3 | 21.8 | - | 313.6 | 127.1 | - | - |

| Office2 | 6 | 9,427.7 | 638.7 | 177.3 | 1,043.1 | - | 44.6 | 46.5 | 74.9 | 609.6 | 81.9 | - | - |

| Office3 | 7 | 11,115.8 | 587.7 | 23.9 | 752.4 | - | 77.4 | 30.2 | 7.6 | 1,446.0 | 260.3 | 10.8 | 3.7 |

| Office4 | 9 | 14,989.1 | 756.3 | - | 1,394.2 | - | 108.2 | 20.6 | 59.1 | 523.2 | 838.1 | 102.5 | - |

| Office5 | 11 | 13,615.0 | 622.6 | 100.3 | 417.4 | - | - | 52.1 | 59.4 | 435.2 | 281.0 | - | - |

| Office6 | 9 | 20,511.5 | 1,213.9 | - | 538.0 | - | - | 10.0 | 115.6 | 829.3 | 474.3 | - | - |

| Office7 | 8 | 17,355.8 | 902.4 | 305.2 | 153.3 | - | 92.7 | 122.7 | 275.3 | 306.9 | 182.2 | - | - |

| Office8 | 7 | 22,065.6 | 1,125.8 | 79.6 | 803.5 | - | 100.2 | 24.9 | 77.3 | 881.6 | 244.0 | - | - |

| Office9 | 9 | 25,601.3 | 1,288.3 | - | 1,998.9 | - | 103.0 | 62.1 | - | 1,180.4 | 258.6 | - | - |

| Office10 | 9 | 24,872.2 | 1,558.9 | - | 2,480.0 | - | - | 78.1 | 138.9 | 1,305.6 | - | 143.6 | - |

| Office11 | 7 | 25,893.4 | 1,503.9 | - | 3,419.7 | - | 121.8 | 63.3 | 205.1 | 1,260.8 | 254.9 | - | - |

| Office12 | 7 | 31,783.2 | 1,638.8 | 178.3 | 1,537.2 | - | 283.7 | 55.8 | - | 941.0 | - | 164.9 | - |

| Office13 | 8 | 31,203.0 | 1,905.3 | - | 2,669.8 | - | - | 31.1 | - | 1,481.3 | 463.7 | 180.7 | - |

| Office14 | 8 | 39,456.0 | 2,274.8 | 305.0 | 2,390.9 | - | 304.7 | 97.9 | 242.0 | 1,759.8 | 274.5 | 206.6 | - |

| Office15 | 7 | 39,139.1 | 2,154.5 | - | 1,689.7 | - | 197.5 | 47.7 | - | 1,022.4 | 325.5 | 151.2 | - |

| Office16 | 10 | 39,869.2 | 1,843.6 | - | 1,489.1 | - | - | 9.0 | 163.7 | 1,252.3 | 256.3 | - | - |

| Office17 | 8 | 50,418.8 | 2,157.1 | - | 3,707.5 | - | - | 155.7 | 211.8 | 1,230.4 | 216.1 | - | - |

| Office18 | 7 | 52,069.7 | 3,227.6 | 343.0 | 2,908.1 | - | 136.5 | 107.1 | 1,185.4 | 522.6 | - | 136.5 | - |

| Office19 | 7 | 42,688.0 | 2,414.1 | - | 1,879.4 | - | 187.4 | 38.3 | - | 1,545.3 | 346.9 | - | - |

| Office20 | 9 | 34,138.9 | 1,906.1 | 1,260.9 | 3,190.8 | - | 158.0 | 78.5 | 377.7 | 184.1 | - | 170.1 | - |

| Office21 | 7 | 50,075.6 | 2,242.6 | 101.5 | 2,121.0 | 25.7 | 310.5 | 140.6 | 119.2 | 3,316.2 | 105.8 | 3.4 | 13.3 |

| Office22 | 9 | 91,913.9 | 9,807.3 | 1,486.8 | 3,376.7 | - | - | 128.9 | 391.0 | 1,901.2 | 827.3 | - | - |

| Office23 | 12 | 123,315.9 | 34,110.4 | 509.3 | - | - | 799.8 | 191.9 | 1,061.0 | 759.0 | - | - | - |

| Office24 | 8 | 82,631.6 | 5,514.8 | 568.4 | 1,736.8 | - | 979.2 | 162.6 | 857.7 | 2,063.4 | - | 276.2 | - |

| Office25 | 7 | 60,687.6 | 6,413.7 | 422.0 | 2,099.5 | - | 975.9 | - | 483.9 | 1,500.0 | 434.0 | 81.5 | 18.0 |

| Office26 | 9 | 71,364.4 | 3,984.7 | 1,160.8 | 3,642.5 | - | - | 102.6 | 1,290.2 | 2,017.6 | - | 337.7 | - |

| Office27 | 10 | 74,342.9 | 6,220.0 | 321.8 | 1,132.5 | - | 226.1 | - | - | 758.4 | - | 218.0 | - |

| Office28 | 8 | 71,319.7 | 4,180.0 | 495.9 | 12,801.0 | - | 334.0 | 213.6 | - | 336.1 | - | 272.2 | - |

| Office29 | 7 | 100,580.6 | 3,794.2 | 386.7 | 17,226.8 | - | 444.3 | 291.9 | - | 469.6 | 411.1 | 474.6 | - |

| Office30 | 8 | 260,850.6 | 18,801.1 | 2,625.8 | 6,393.8 | - | - | 403.5 | 2,344.2 | 5,796.0 | 1,878.0 | - | - |

| Office31 | 9 | 451,917.6 | 48,016.3 | 6,475.1 | 37,597.1 | - | - | 774.3 | 3,994.6 | 13,536.3 | 3,892.2 | - | - |

| Office32 | 8 | 4,961.3 | 289.3 | - | 354.1 | - | - | 0.6 | - | 266.5 | - | - | - |

| Office33 | 8 | 4,491.9 | 205.9 | 15.5 | 225.4 | - | - | 20.4 | - | 122.7 | - | - | - |

| School1 | 8 | 15,010.6 | 794.4 | - | 1,363.3 | 16.7 | 62.7 | 35.7 | - | 430.7 | 482.0 | - | - |

| School2 | 6 | 117,108.4 | 5,445.8 | 396.2 | 4,676.4 | - | - | 200.4 | - | 2,353.6 | - | - | - |

| School3 | 6 | 35,410.8 | 1,758.4 | - | 7,088.5 | - | - | 61.1 | - | 2,670.4 | 229.4 | - | - |

| School4 | 7 | 30,123.1 | 1,490.8 | - | 1,457.5 | - | - | 168.1 | 618.6 | 2,774.4 | 139.0 | - | - |

| School5 | 11 | 18,092.0 | 1,078.7 | 77.7 | 236.5 | - | 44.0 | 23.7 | 19.9 | 1,063.3 | 347.2 | 12.4 | 19.4 |

| School6 | 8 | 143,970.8 | 11,197.3 | - | 4,451.6 | - | 658.2 | 209.9 | - | 7,821.4 | 607.6 | 531.5 | - |

| Retail | 8 | 246,470.6 | 19,598.9 | 2,373.2 | 5,098.0 | - | - | 354.8 | 2,548.4 | 30,070.3 | - | 894.3 | - |

| Hotel1 | 8 | 9,671.5 | 482.6 | - | 352.9 | - | - | 23.8 | 24.7 | 395.2 | 155.9 | - | - |

| Hotel2 | 7 | 8,803.2 | 487.0 | - | 597.7 | - | - | 5.2 | - | 743.7 | 46.8 | - | - |

| Average | 8 | 98,265.6 | 5,237.5 | 477.3 | 6,293.6 | 9.7 | 334.9 | 169.0 | 419.1 | 2,767.2 | 674.4 | 157.8 | 2.7 |

References

- IEA & UNEP. (2025). Not just another brick in the wall: The solutions exist-Scaling them will build on progress and cut emissions fast. Global Status Report for Building and Construction 2024/2025: https://globalabc.org. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/47214, (accessed on 28.07.2025.).

- Röck, M.; Saade, M.R.M.; Balouktsi, M.; Rasmussen, F.N.; Birgisdottir, H.; Frischknecht, R.; Habert, G.; Lützkendorf, T.; Passer, A. Embodied GHG emissions of buildings – The hidden challenge for effective climate change mitigation. Appl. Energy 2019, 258, 114107. [CrossRef]

- Moncaster, A.; Symons, K. A method and tool for ‘cradle to grave’ embodied carbon and energy impacts of UK buildings in compliance with the new TC350 standards. Energy Build. 2013, 66, 514–523. [CrossRef]

- Guggemos, A.A.; Horvath, A. Comparison of Environmental Effects of Steel- and Concrete-Framed Buildings. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2005, 11, 93–101. [CrossRef]

- Comparison of the certification systems for buildings DGNB, LEED and BREEAM. ICDLI (International Committee of the Decorative Laminates Industry) 2019. www.icdli.com (assessed on 28.07.2025.).

- Barjot, Z.; Malmqvist, T. Limit values in LCA-based regulations for buildings – System boundaries and implications on practice. Build. Environ. 2024, 259. [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.F.; Rincón, L.; Vilariño, V.; Pérez, G.; Castell, A. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle energy analysis (LCEA) of buildings and the building sector: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 394–416. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.K. Life cycle embodied energy analysis of residential buildings: A review of literature to investigate embodied energy parameters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 390–413. [CrossRef]

- Obrecht, T.P.; Kunič, R.; Jordan, S.; Legat, A.; Roles of the reference service life (RSL) of buildings and the RSL of building components in the environmental impacts of buildings. SBE19 Graz 2019, 323, 012146. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lee, S.; Chae, C.U.; Jang, H.; Lee, K. Development of the CO2 Emission Evaluation Tool for the Life Cycle Assessment of Concrete. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2116. [CrossRef]

- Asdrubali, F.; Baldassarri, C.; Fthenakis, V. Life cycle analysis in the construction sector: Guiding the optimization of conventional Italian buildings. Energy Build. 2013, 64, 73–89. [CrossRef]

- Bribián, I.Z.; Capilla, A.V.; Usón, A.A. Life cycle assessment of building materials: Comparative analysis of energy and environmental impacts and evaluation of the eco-efficiency improvement potential. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1133–1140. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tae, S. Assessment of Carbon Neutrality Performance of Buildings Using EPD-Certified Korean Construction Materials. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6533. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jang, H.; Tae, S.; Kim, H.; Jo, K. Life-Cycle Assessment of Apartment Buildings Based on Standard Quantities of Building Materials Using Probabilistic Analysis Technique. Materials 2022, 15, 4103. [CrossRef]

- Akbarnezhad, A.; Xiao, J. Estimation and Minimization of Embodied Carbon of Buildings: A Review. Buildings 2017, 7, 5. [CrossRef]

- Passer, A.; Kreiner, H.; Maydl, P. Assessment of the environmental performance of buildings: A critical evaluation of the influence of technical building equipment on residential buildings. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 1116–1130. [CrossRef]

- Buyle, M.; Braet, J.; Audenaert, A. Life cycle assessment in the construction sector: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 379–388. [CrossRef]

- Lasvaux, S.; Schiopu, N.; Habert, G.; Chevalier, J.; Peuportier, B. Influence of simplification of life cycle inventories on the accuracy of impact assessment: application to construction products. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 142–151. [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Das, B.B. Life Cycle Assessment of construction materials: Methodologies, applications and future directions for sustainable decision-making. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19. [CrossRef]

- Collinge, W.; Thiel, C.; Campion, N.; Al-Ghamdi, S.; Woloschin, C.; Soratana, K.; Landis, A.; Bilec, M. Integrating Life Cycle Assessment with Green Building and Product Rating Systems: North American Perspective. Procedia Eng. 2015, 118, 662–669. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Pinheiro, M.D.; de Brito, J.; Mateus, R. A critical analysis of LEED, BREEAM and DGNB as sustainability assessment methods for retail buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66. [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Embodied carbon mitigation and reduction in the built environment – What does the evidence say?. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 687–700. [CrossRef]

- Onososen, A.; Musonda, I. Barriers to BIM-Based Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Buildings: An Interpretive Structural Modelling Approach. Buildings 2022, 12, 324. [CrossRef]

- Ebeh, C. O.; Okwandu, A. C.; Abdulwaheed, S. A.; Iwanyanwu, O. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) in Construction: Methods, Applications, and Outcomes. International Journal of Engineering Research and Development 2024, 20(8), 350-358. https://ijerd.com/paper/vol20-issue8/2008350358.pdf,(accessed on 28.07.2025.).

- Parece, S.; Resende, R.; Rato, V. Stakeholder Perspectives on BIM–LCA Integration in Building Design: Adoption, Challenges, and Future Directions. Build. Environ. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dodoo, A.; Gustavsson, L.; Sathre, R. Lifecycle carbon implications of conventional and low-energy multi-storey timber building systems. Energy Build. 2014, 82, 194–210. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Maurya, K.K.; Mandal, S.K.; Mir, B.A.; Nurdiawati, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Life Cycle Assessment in the Early Design Phase of Buildings: Strategies, Tools, and Future Directions. Buildings 2025, 15, 1612. [CrossRef]

- Anyanya, D.; Paulillo, A.; Fiorini, S.; Lettieri, P. Evaluating sustainable building assessment systems: a comparative analysis of GBRS and WBLCA. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

| Year | Num of Certification | Num of LCA Reporting | LCA reporting Ratio |

| 2016 | 1,639 | - | - |

| 2017 | 1,765 | 6 | 0.34% |

| 2018 | 2,000 | 38 | 1.90% |

| 2019 | 2,169 | 118 | 5.44% |

| 2020 | 2,324 | 241 | 10.37% |

| 2021 | 2,383 | 377 | 15.82% |

| 2022 | 2,319 | 448 | 19.32% |

| 2023 | 2,509 | 565 | 22.52% |

| 2024 | 2,381 | 576 | 24.19% |

| Total | 19,489 | 2,369 | 12.16% |

| Number of Buildings (Total 100) | ||

| Building Type | Residential | 20 |

| Non-residential | 38 | |

| Office | 33 | |

| School | 6 | |

| Hotel | 2 | |

| Retail | 1 | |

| Structural Type | RC | 76 |

| RC+S | 10 | |

| SRC | 14 | |

| Material Category | Examples | Functional Role |

| Concrete (Ready-mixed) | Normal-strength, high-strength concrete | Primary structural component |

| Structural Steel | Deformed bars, welded wire mesh, H-beams, columns, steel framing | Structural reinforcement and system (steel buildings) |

| Metal Finishes | Aluminum & steel plates | Non-structural finishes, facade |

| Cement & Bricks | Mortar cement, solid bricks | Masonry walls, partitions |

| Wood | Structural timber, plywood | Structural timber, Internal reinforcement, finishes |

| Glass Products | Single-pane, double-pane, Low-E glass | Windows, facades |

| Insulation Materials | EPS, XPS, glass wool, urethane foam | Thermal insulation |

| Gypsum Board | Drywall panels | Interior wall finishes |

| Sand and Gravel | Fine aggregate, coarse aggregate | Concrete mix, bedding material |

| Stone Materials | Natural stone, marble, granite | Exterior and interior finishes |

| Tiles | Ceramic tiles, porcelain tiles | Flooring, wet area finishes |

| Paint and Wall Covering | Emulsion paints, wallpapers | Interior finishing |

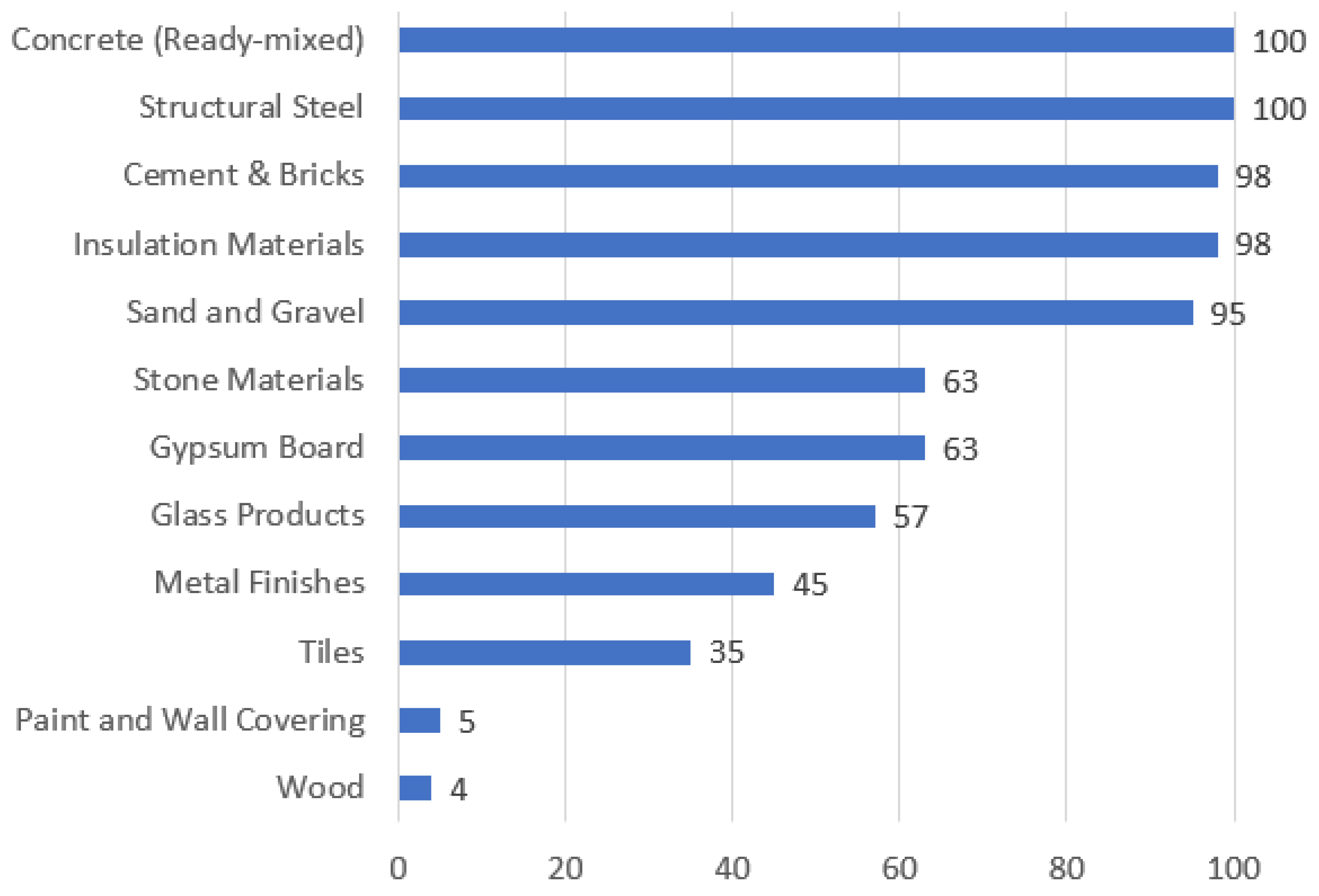

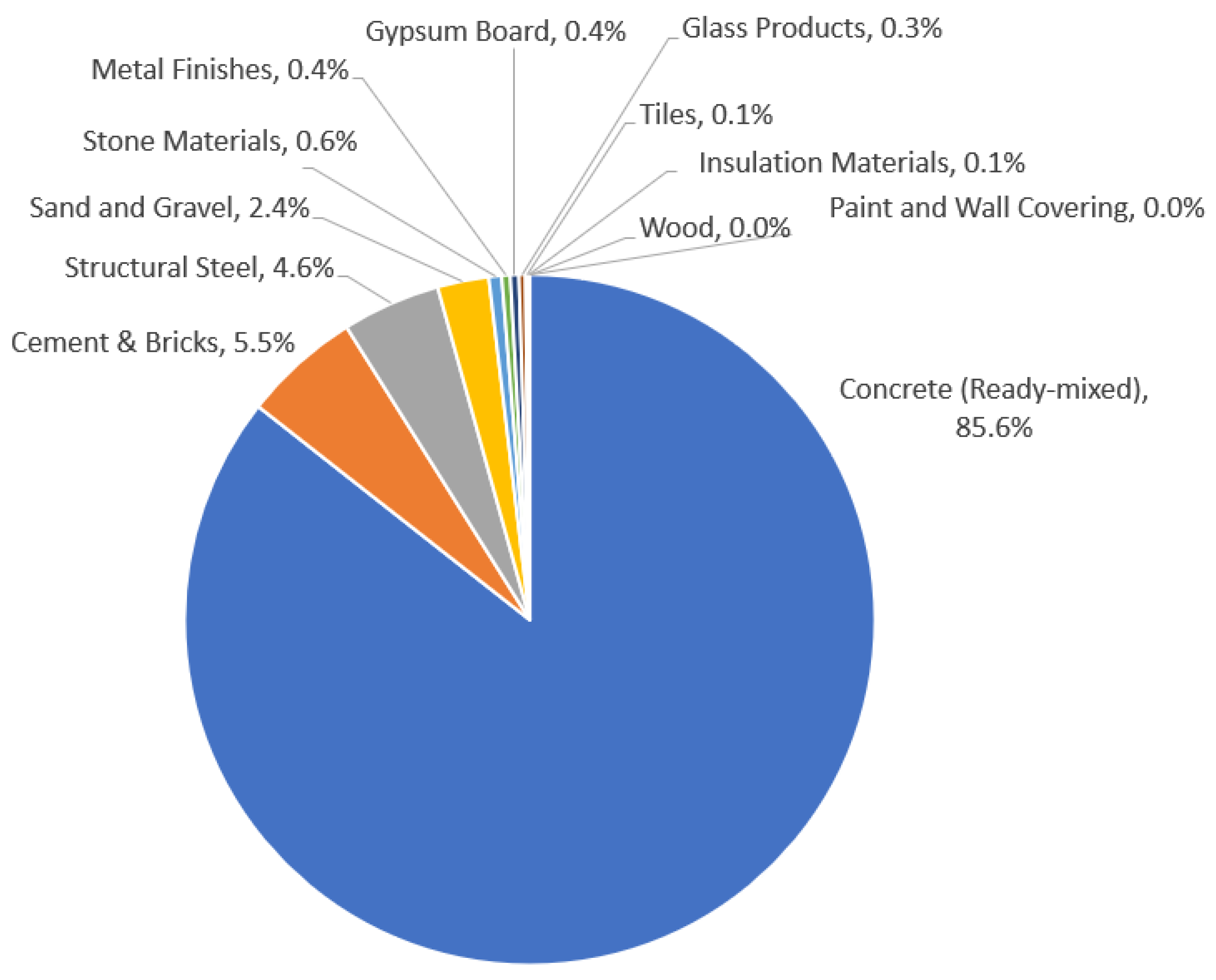

| Material Category | Number of LCA Reports using the Material Category |

Mass Balance Average Ratio |

|

| 1 | Concrete (Ready-mixed) | 100 | 85.6% |

| 2 | Structural Steel | 100 | 4.6% |

| 3 | Metal Finishes | 45 | 0.4% |

| 4 | Cement & Bricks | 98 | 5.5% |

| 5 | Wood | 4 | 0.0% |

| 6 | Glass Products | 57 | 0.3% |

| 7 | Insulation Materials | 98 | 0.1% |

| 8 | Gypsum Board | 63 | 0.4% |

| 9 | Sand and Gravel | 95 | 2.4% |

| 10 | Stone Materials | 63 | 0.6% |

| 11 | Tiles | 35 | 0.1% |

| 12 | Paint and Wall Covering | 5 | 0.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).