3.4. RSM and DFA Analysis

The previously described experimental methodology was implemented using response surface methodology (RSM), following a structured approach. Initially, the factors influencing the response variables were identified, and the corresponding experiments were conducted. In the subsequent stage, the optimal values for each response variable were determined. A tailored RSM design was developed to maximize operational time (

), distance traveled (

), and energy efficiency in kilometers per ampere-hour (

: km/Ah), using the steepest ascent technique. The consolidated data presented in

Table 2 summarize the outcomes obtained for each combination of factors and include additional performance indicators such as mean power and energy consumed in ampere-hours (Ah), enabling a more comprehensive analysis of the vehicle’s behavior under varying experimental conditions.

Notably, the experiment recorded a maximum operational time of 1.12 hours, a maximum distance of 24.63 km, and a peak efficiency of 2.82 km/Ah, all achieved under the conditions of Trial E5. Likewise, the minimum energy consumption was recorded at 6.98 Ah in Trial E1. Additionally, to validate the optimal points identified through RSM, the desirability function approach was applied as a complementary technique. This allowed for the simultaneous evaluation of multiple objectives, reinforcing the reliability of the proposed solution and ensuring a balanced optimization between performance, autonomy, and energy efficiency of the electric racing vehicle.

Table 2.

Data collected

| Experiment |

Battery |

Weight

(Kg) |

Mode |

Time

(h) |

Mean

Power

(W) |

Distance

(km) |

Mean

Speed

(km/h) |

Energy

Consumed

(Ah) |

Efficiency

(km/Ah) |

| E1 |

2 |

76 |

9 |

0.61 |

568.49 |

13.91 |

22.92 |

6.98 |

1.99 |

| E2 |

2 |

76 |

9 |

0.72 |

529.76 |

16.14 |

22.42 |

8.60 |

1.88 |

| E3 |

2 |

76 |

7 |

0.78 |

462.83 |

17.56 |

22.54 |

8.17 |

2.15 |

| E4 |

1 |

76 |

7 |

0.71 |

528.16 |

17.62 |

22.44 |

9.33 |

1.89 |

| E5 |

1 |

66 |

5 |

1.12 |

361.69 |

24.63 |

22.09 |

8.73 |

2.82 |

| E6 |

1 |

66 |

7 |

0.79 |

449.95 |

19.81 |

25.01 |

7.57 |

2.62 |

| E7 |

1 |

76 |

5 |

0.99 |

363.49 |

21.34 |

21.58 |

7.88 |

2.70 |

| E8 |

1 |

86 |

5 |

0.94 |

402.57 |

20.41 |

21.76 |

8.19 |

2.49 |

| E9 |

1 |

86 |

9 |

0.72 |

544.83 |

16.48 |

22.74 |

8.75 |

1.88 |

| E10 |

2 |

66 |

5 |

1.08 |

356.25 |

23.45 |

21.65 |

8.44 |

2.78 |

| E11 |

2 |

86 |

9 |

0.86 |

495.86 |

18.37 |

21.48 |

9.69 |

1.90 |

| E12 |

2 |

66 |

7 |

0.90 |

422.77 |

21.09 |

23.40 |

8.34 |

2.53 |

| |

|

|

Mean |

0.86 |

457.22 |

19.23 |

22.50 |

8.39 |

2.302 |

To perform the response surface analysis, the input variables were codified using the standard transformation

, which centers and scales each factor around its midpoint. Specifically, battery type (

) was coded as

, pilot weight (

) as

, and power mode (

) as

. This transformation ensures that all input factors are scaled to a comparable range and centered around zero, facilitating the fitting of second-order polynomial models. The codified dataset, used as input for the response surface modeling process, is summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3.

Data codified

| Experiment |

x1 |

x2 |

x3 |

y1 |

y2 |

y3 |

| E1 |

1 |

0.08 |

1 |

0.61 |

13.91 |

6.98 |

| E2 |

1 |

0.08 |

1 |

0.72 |

16.14 |

8.60 |

| E3 |

1 |

0.08 |

0 |

0.78 |

17.56 |

8.17 |

| E4 |

-1 |

0.08 |

0 |

0.71 |

17.62 |

9.33 |

| E5 |

-1 |

-0.92 |

-1 |

1.12 |

24.63 |

8.73 |

| E6 |

-1 |

-0.92 |

1 |

0.79 |

19.81 |

7.57 |

| E7 |

-1 |

0.08 |

-1 |

0.99 |

21.34 |

7.88 |

| E8 |

-1 |

1.08 |

-1 |

0.94 |

20.41 |

8.19 |

| E9 |

-1 |

1.08 |

1 |

0.72 |

16.48 |

8.75 |

| E10 |

1 |

-0.92 |

-1 |

1.08 |

23.45 |

8.44 |

| E11 |

1 |

1.08 |

1 |

0.86 |

18.37 |

9.69 |

| E12 |

1 |

-0.92 |

0 |

0.90 |

21.09 |

8.34 |

This article introduces a method for identifying the optimal configuration for multiparameter optimization, aiming to maximize time, distance, and energy efficiency. The approach is based on a 2×3×3 factorial design involving three factors: Battery (), Weight (), and Power Mode (), and employs response surface methodology (RSM) to model the system’s behavior.

The factor Mode () was found to be statistically significant for the response variable total_time_hours, with a p-value below the 0.01 threshold. While Weight () was not significant on its own, its interaction with Mode () showed a significant effect ().

After evaluating four candidate models—first-order (FO), first-order with two-way interactions (FO + TWI), full second-order (SO), and a combined model with principal and quadratic effects on selected factors (FO + PQ(, ))—the FO + TWI model was selected as the optimal specification for the response variable total_time_hours. This model balances statistical accuracy with numerical stability and interpretability, avoiding issues of coefficient aliasing present in the full second-order model.

The decision is supported by the model’s statistical performance: an adjusted of 0.842 and a global p-value of 0.0098 indicate strong explanatory power. Furthermore, the power mode () was statistically significant (), and the interaction between weight and mode () was also significant (). These findings validate the inclusion of interaction terms in the model, supporting its use in response surface optimization and canonical analysis.

Table 4.

Estimated coefficients and model fit statistics for the selected model (FO + TWI) for total_time_hours

Table 4.

Estimated coefficients and model fit statistics for the selected model (FO + TWI) for total_time_hours

| Term |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

p-value |

| Intercept |

0.8062 |

0.0287 |

<0.001 ***

|

|

0.0137 |

0.0219 |

0.5582 |

|

0.0030 |

0.0325 |

0.9302 |

|

-0.1837 |

0.0309 |

0.0019 **

|

|

-0.0242 |

0.0379 |

0.5514 |

|

0.0489 |

0.0386 |

0.2608 |

|

0.1316 |

0.0390 |

0.0198 *

|

| Model statistics: |

| Multiple R-squared |

0.9282 |

| Adjusted R-squared |

0.8420 |

| F-statistic (df = 6, 5) |

10.77 |

| Model p-value |

0.0098 |

Following the comparative evaluation of four candidate models for the response variable total_distance_km, the model combining first-order effects with quadratic terms for pilot weight and power mode (FO + PQ(, )) was selected as the most appropriate specification. While the full second-order model exhibited a slightly higher adjusted (0.8951), it suffered from aliasing issues that precluded reliable canonical analysis and optimal path tracing. In contrast, the FO + PQ model offered a robust balance between statistical accuracy and model simplicity, achieving an adjusted of 0.8346 and a global p-value of 0.0043.

Crucially, the quadratic effect of pilot weight () was statistically significant (), confirming the presence of nonlinearity in the response surface. The inclusion of curvature improves the model’s ability to capture relevant behavioral patterns of the system, without overfitting or compromising interpretability. These findings support the selection of the FO + PQ model for analyzing the factors that influence the vehicle’s travel distance, and for optimizing performance within the response surface methodology (RSM) framework.

Table 5.

Estimated coefficients and model fit statistics for the selected model (FO + PQ(, )) for total_distance_km

Table 5.

Estimated coefficients and model fit statistics for the selected model (FO + PQ(, )) for total_distance_km

| Term |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

p-value |

| Intercept |

17.4903 |

0.7748 |

<0.001 ***

|

|

0.1303 |

0.4364 |

0.7754 |

|

-1.3822 |

0.6306 |

0.0709 .

|

|

-2.5223 |

0.5868 |

0.0051 **

|

|

2.2512 |

0.7774 |

0.0275 *

|

|

0.6693 |

0.8853 |

0.4783 |

| Model statistics: |

| Multiple R-squared |

0.9098 |

| Adjusted R-squared |

0.8346 |

| F-statistic (df = 5, 6) |

12.1 |

| Model p-value |

0.0043 |

For the response variable , corresponding to the vehicle’s energy efficiency measured in kilometers per ampere-hour (km/Ah), four candidate models were evaluated: the first-order (FO), the first-order with two-way interactions (FO + TWI), the full second-order (SO), and a reduced second-order model including principal effects and quadratic terms for selected factors (FO + PQ(, )). Although the full SO model showed a high unadjusted (0.9349), it suffered from multicollinearity and aliasing issues, limiting its applicability for canonical analysis and numerical optimization.

After evaluating performance and interpretability, the FO + PQ(

,

) model was selected as the most appropriate specification for modeling

, as shown in

Table 6. This model attained the highest adjusted

(0.8553) among all valid specifications, with a statistically significant overall fit (

). Notably, both the Weight (

) and Power Mode (

) factors had significant effects (

and

, respectively), reinforcing the relevance of these variables. The inclusion of curvature through quadratic terms improved model accuracy without introducing singularities, enabling a valid canonical analysis and identification of a stationary point. This makes the FO + PQ(

,

) model particularly suitable for optimizing vehicle energy efficiency under the response surface methodology (RSM) framework.

Table 6.

Estimated coefficients and model fit statistics for the selected FO + PQ(, ) model for efficiency_km_per_ah

Table 6.

Estimated coefficients and model fit statistics for the selected FO + PQ(, ) model for efficiency_km_per_ah

| Term |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

p-value |

| Intercept |

2.1302 |

0.0897 |

<0.001

|

|

-0.0052 |

0.0506 |

0.9211 |

|

-0.2329 |

0.0730 |

0.0189 *

|

|

-0.2938 |

0.0680 |

0.0050 **

|

|

0.1626 |

0.0900 |

0.1210 |

|

0.1178 |

0.1025 |

0.2942 |

| Model statistics: |

| Multiple R-squared |

0.9211 |

| Adjusted R-squared |

0.8553 |

| F-statistic (df = 5, 6) |

14.00 |

| Model p-value |

0.0029 |

The ANOVA results, summarized in

Table 7, were used to validate the statistical significance and predictive capacity of the selected models for each response variable. For operational time (

total_time_hours), the first-order model with two-way interactions (FO + TWI) provided the best trade-off between model complexity and interpretability, showing statistically significant main effects, a high adjusted

of 0.842, and a global model p-value of 0.0098.

In contrast, for distance traveled (total_distance_km) and energy efficiency (efficiency_km_per_ah), the models that combined first-order terms with quadratic effects in weight and power mode (FO + PQ()) were selected. These models captured relevant nonlinearities without coefficient aliasing, enabling the application of canonical analysis. Both models showed strong explanatory power, with adjusted values of 0.8346 and 0.8553, respectively, and global p-values below 0.005. The significance of the quadratic term in the distance model () further validated the presence of curvature in the response surface.

Table 7.

ANOVA for the selected models for each response variable

Table 7.

ANOVA for the selected models for each response variable

| Effect |

Df (Time) |

F (Time) |

Df (Distance) |

F (Distance) |

Df (Efficiency) |

F (Efficiency) |

| FO(, , ) |

3 |

17.09 |

3 |

16.86 |

3 |

21.55 |

| TWI(, , ) |

3 |

4.45 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| PQ(, ) |

— |

— |

2 |

4.95 |

2 |

2.69 |

| Residuals |

5 |

— |

6 |

— |

6 |

— |

| p-value (FO) |

|

0.0046 ** |

|

0.0025 ** |

|

0.0013 ** |

| p-value (TWI) |

|

0.0709 .

|

|

— |

|

— |

| p-value (PQ) |

|

— |

|

0.0536 .

|

|

0.1465 |

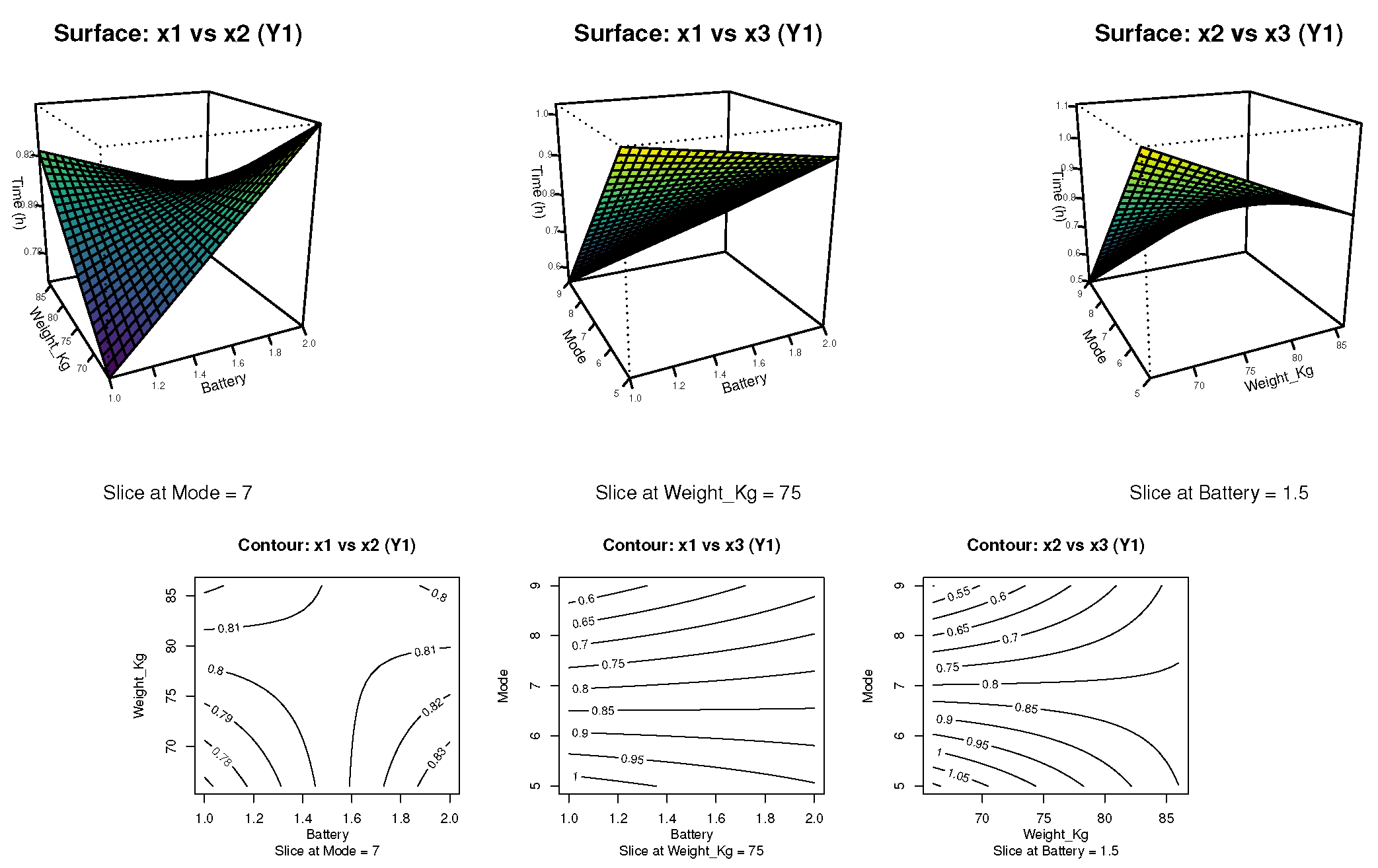

Figure 5 presents the two-dimensional (2D) contour plots and three-dimensional (3D) surface graphs derived from the selected FO + TWI model for the response variable

(operational time). These visualizations illustrate how combinations of battery type (

), pilot weight (

), and power mode (

) influence vehicle endurance. The 2D contour plots reveal several trends: at a fixed power mode (N7), operational time increases modestly as pilot weight decreases, particularly with intermediate battery types; at a constant weight of 75 kg, operational time declines with increasing power mode, showing a clear advantage in favor of low-power configurations (e.g., N5); and, when holding the battery constant at a midrange value (

), longer operational times are concentrated in the low-weight, low-power region, suggesting an interaction effect between

and

.

The 3D response surfaces confirm these patterns by highlighting a clearly defined optimal zone: maximum operational time is achieved when the pilot weight is minimized (66 kg) and the power mode is set to N5. Among the three factors, the power mode () exerts the most substantial influence on the response, as evidenced by the steeper gradients along that axis. The effect of pilot weight, although less pronounced, remains consistent with the direction of maximum ascent identified in the RSM optimization. Additionally, the overall smooth and gently curved surfaces indicate the absence of significant second-order effects, supporting the adequacy of the FO + TWI model in capturing the response behavior without requiring quadratic terms. These graphical insights not only validate the statistical model but also offer practical guidance for configuring the vehicle to extend its operational autonomy under energy-conserving conditions.

Figure 5.

Response surface and contour plots for the response variable (operational time), based on the FO + TWI model. Source: Author’s own elaboration

Figure 5.

Response surface and contour plots for the response variable (operational time), based on the FO + TWI model. Source: Author’s own elaboration

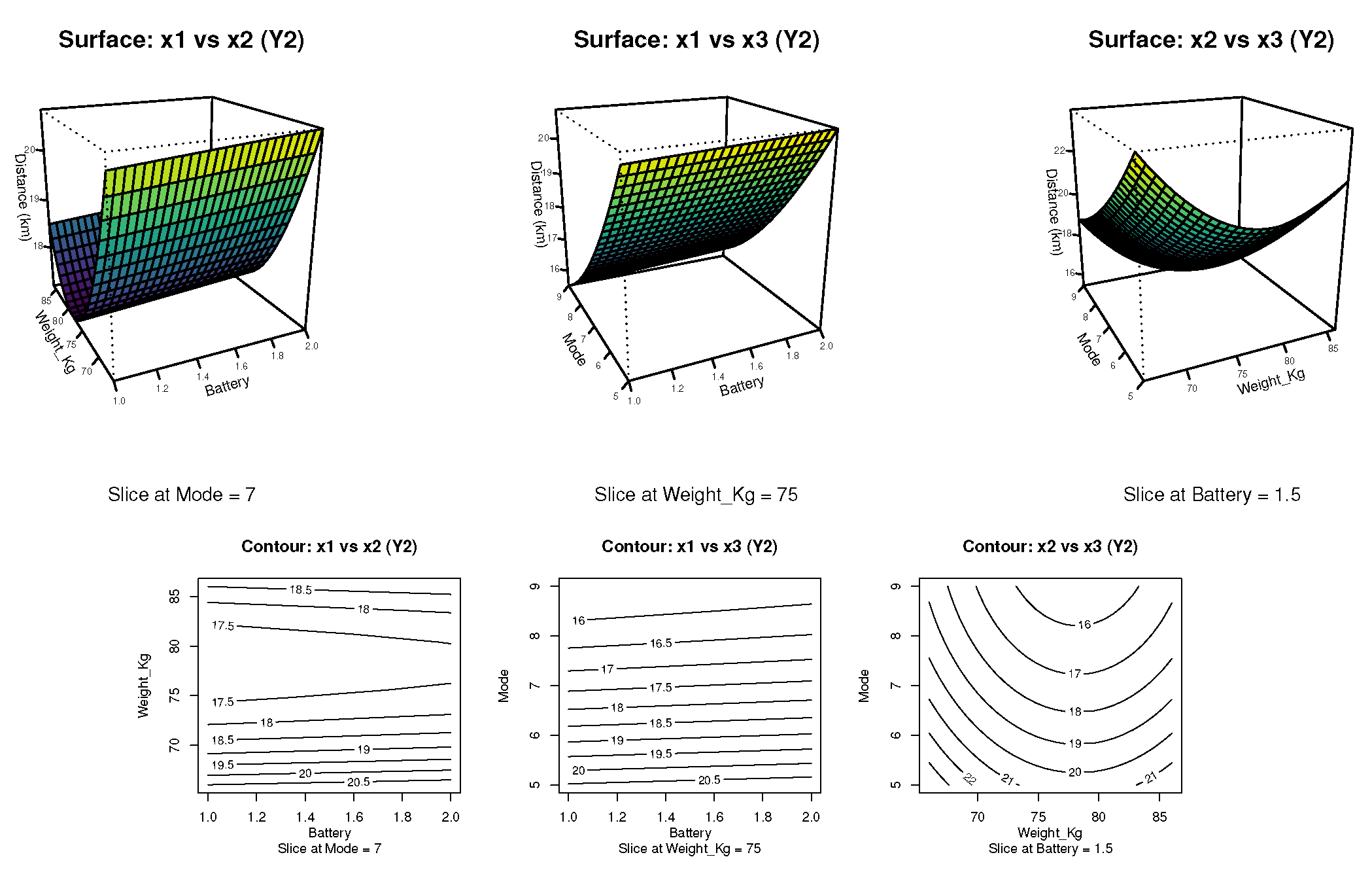

The graphical analysis presented in

Figure 6 corresponds to the response surface and contour plots derived from the selected FO + PQ(

) model for the variable

(distance traveled). In the contour plots, it is evident that maximum distances are achieved at low pilot weights and low power modes (N5), with intermediate to high battery types. Specifically, in the

vs

projection, operational modes held constant at N7 reveal increased distances with lighter pilots and higher-capacity batteries. The

vs

plot, with fixed weight (75 kg), confirms that increased power mode reduces travel range. The

vs

plot clearly shows a curved interaction, justifying the inclusion of quadratic terms.

The 3D surface plots reaffirm the trends observed in the contours and highlight the non-linear nature of the response. Particularly, the curved surface along the and axes illustrates a quadratic interaction that impacts the distance outcome. The optimal zone is confirmed to be located in the region combining a light pilot (66 kg), low power mode (N5), and a battery type close to 2.0. These visual insights validate the model selection and guide decision-making for maximizing distance performance in electric vehicle operation.

Figure 6.

Response surface and contour plots for the response variable (distance traveled), based on the FO + PQ() model. Source: Author’s own elaboration

Figure 6.

Response surface and contour plots for the response variable (distance traveled), based on the FO + PQ() model. Source: Author’s own elaboration

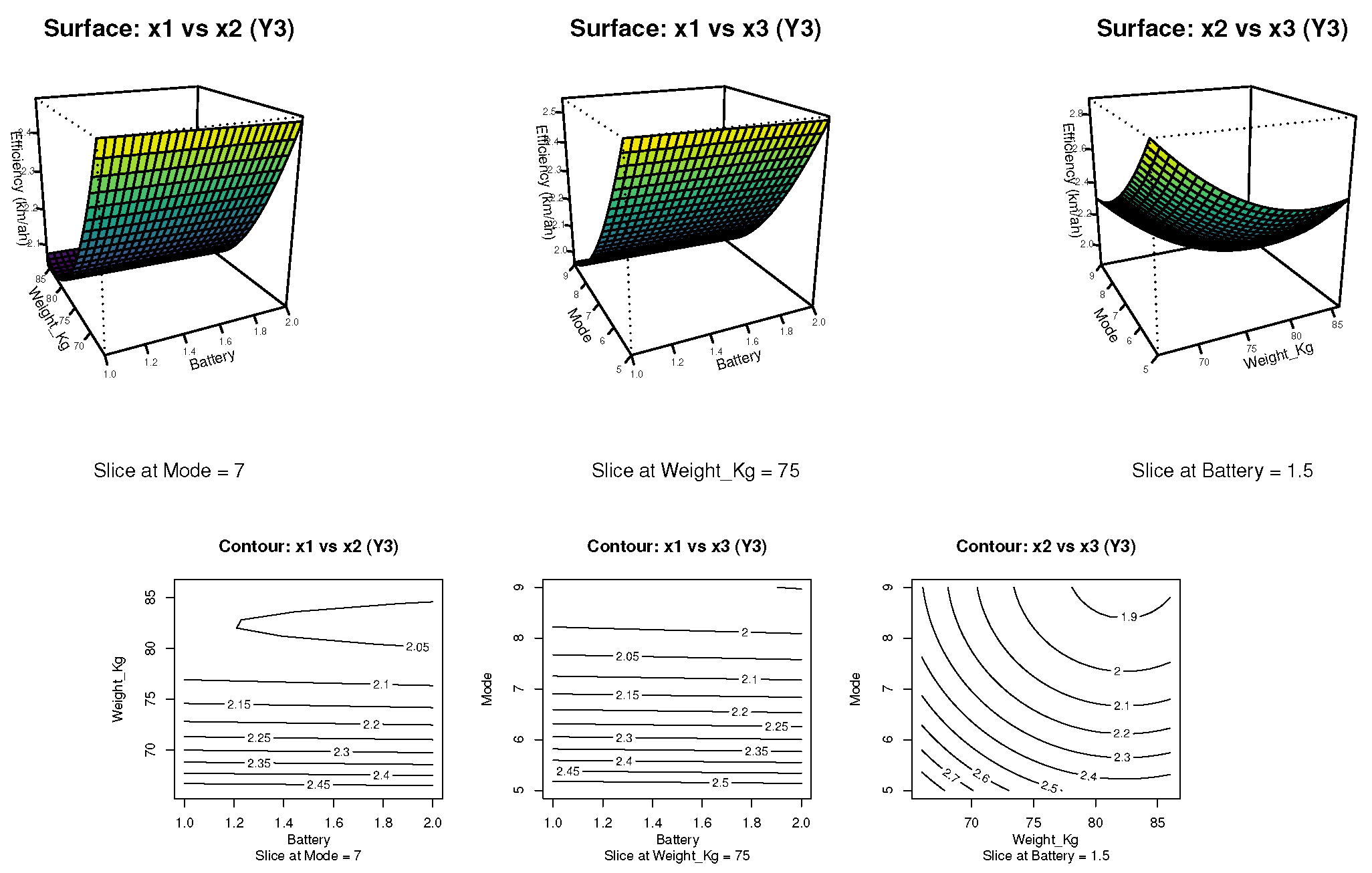

The figures present the 2D contour and 3D surface plots for the response variable , which represents the energy efficiency of the electric vehicle in km/Ah. These plots were generated based on the selected FO + PQ() model and allow for the visualization of interactions among battery type (), pilot weight (), and power mode ().

The contour plots reveal that maximum efficiency is achieved with lower pilot weights (66 kg) and conservative power settings (mode 5). The surface plots reinforce this finding by displaying increasing efficiency gradients in those regions. These visualizations support the use of this model to identify optimal zones for energy-saving operation strategies in electric vehicles.

Figure 7.

Response surface and contour plots for the variable (energy efficiency), based on the FO + PQ() model. Source: Author’s own elaboration

Figure 7.

Response surface and contour plots for the variable (energy efficiency), based on the FO + PQ() model. Source: Author’s own elaboration

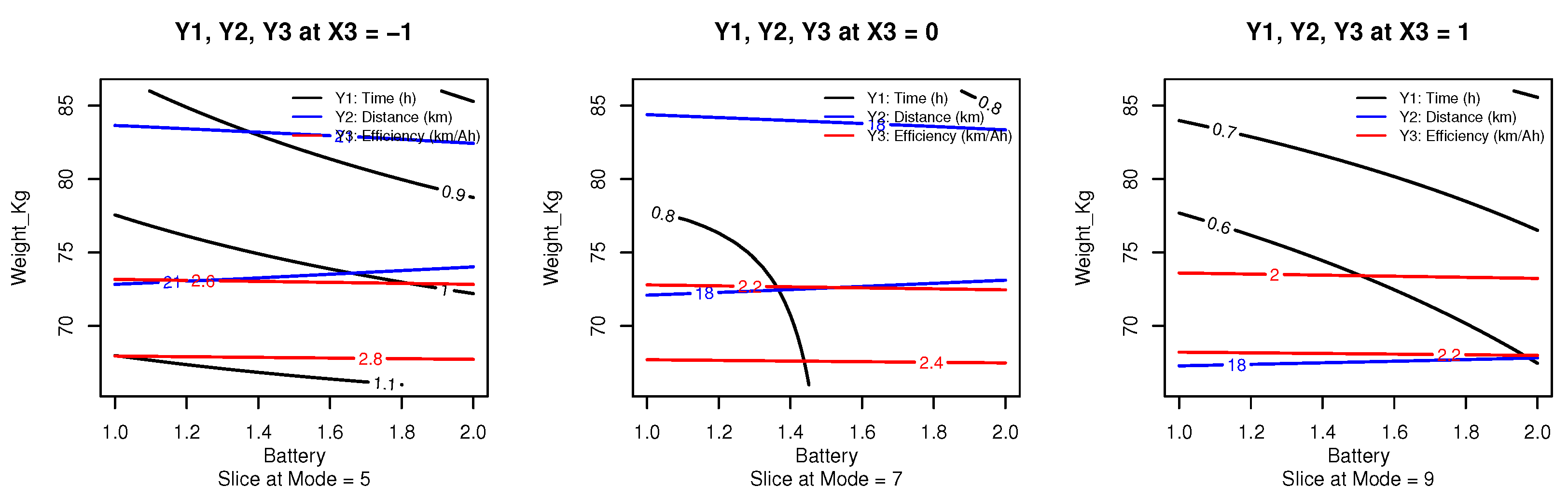

Figure 8 illustrates the simultaneous contour plots for the three response variables: operational time (

), total distance traveled (

), and energy efficiency (

), as functions of battery type (

) and pilot weight (

). The plots are stratified by three fixed levels of the power mode factor (

), corresponding to coded values of

, 0, and 1, which translate to real settings of N5, N7, and N9, respectively. This multi-response graphical optimization approach enables the identification of regions in the experimental domain where the performance of all three responses is jointly favorable.

To construct these plots, predictions were generated from the fitted RSM models for each response, and contour lines were overlaid within the same coordinate space using distinct colors: black for , blue for , and red for . The graphical superposition reveals that the most desirable operating region—where all three responses reach high levels—is located near the lower bounds of pilot weight and battery capacity, particularly when operating in mode N5. These findings reinforce the optimization results obtained via canonical path analysis and desirability function maximization, validating mode N5 as the most energy-efficient and autonomous configuration under lightweight operating conditions.

Figure 8.

Superimposed contour plots for the response variables (operational time), (travel distance), and (energy efficiency), at three fixed levels of power mode . Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Figure 8.

Superimposed contour plots for the response variables (operational time), (travel distance), and (energy efficiency), at three fixed levels of power mode . Source: Author’s own elaboration.

In addition to the contour superposition method used for graphical multi-response optimization, individual optimizations were carried out for each response variable by evaluating the fitted RSM models over a fine grid of experimental conditions. This approach allowed for the identification of the optimal settings of the control factors—battery type (), pilot weight (), and power mode ()—that maximize each response individually within the defined experimental region.

For operational time (), the optimal condition was found at the lowest tested values of battery capacity (1.0), pilot weight (66 kg), and power mode (N5), yielding a maximum estimated value of 1.129 hours. Similarly, the optimal travel distance () was achieved under the same lightweight and low-power conditions, but with the highest tested battery capacity (2.0), resulting in a maximum estimated distance of 24.446 km. In the case of energy efficiency (), the optimal configuration coincided with that of , at minimum battery size (1.0), minimum pilot weight (66 kg), and low power mode (N5), yielding a predicted value of 2.942 km/Ah. These individual optimization results support the suitability of lightweight configurations and conservative power settings for maximizing both autonomy and energy performance in electric vehicles.

Finally, a multi-response optimization was performed using the desirability function approach, which allows for the simultaneous maximization of all response variables by transforming them into a common scale of desirability ranging from 0 (completely undesirable) to 1 (fully desirable). Individual desirability functions were defined for each response variable, aiming to maximize operational time () with a target of 1.2 hours, total distance () with a target of 24 km, and energy efficiency () with a target of 2.8 km/Ah. The global desirability was computed as the geometric mean of the three individual desirabilities across all experimental combinations.

The optimal solution identified through this method corresponds to the configuration with codified factor levels , , and , which in the original units translates to a battery size of 1.0, a pilot weight of approximately 66 kg, and power mode N5. In this setting, the predicted values were hours, km, and km/Ah, resulting in a high overall desirability score of 0.945. This result confirms the consistency of the previous optimization methods, reinforcing the suitability of low-weight and low-power configurations for maximizing the electric vehicle’s performance across multiple criteria.

The integrated analysis of optimization strategies, including contour-based visual exploration, individual RSM model predictions, and composite desirability evaluation, provided a comprehensive and convergent understanding of optimal operating conditions for maximizing electric vehicle performance.

In individual optimization of each response variable, the three models independently identified the lowest pilot weight (66 kg) and the lowest power mode (N5) as the ideal conditions to maximize operational time (), total distance traveled () and energy efficiency (). However, differences emerged in the battery configuration: while the smallest battery type (1.0) yielded the best results for and , the longest distance () was achieved with a higher capacity battery (2.0). This indicates a trade-off between energy efficiency and storage capacity, where larger batteries favor extended range but may compromise efficiency and lightweight dynamics.

The contour superposition method, visually represented in the comparative plots, revealed a common favorable region in the design space—low values of battery (1.0–1.2), weight (66–70 kg), and power mode (N5). This region visually aligns with the numerically derived optima, confirming the validity of the response surface methodology (RSM) in identifying multiobjective trade-offs. The overlay of response surfaces also demonstrated that, despite differing optimal battery choices in some objectives, a feasible zone of convergence exists where all three responses perform satisfactorily.

Lastly, the composite desirability optimization further confirmed this convergence. The best compromise solution was found at (Battery = 1.0), (Weight = 66 kg), and (Mode = 5), with predicted values of 1.121 hours for , 23.71 km for , and 2.90 km/Ah for . This combination yielded a high overall desirability score of 0.945, reinforcing its status as the optimal balance between endurance, range, and energy efficiency.

All three methods - individual optimization, graphical contour intersection and desirability function - coincide in identifying the low pilot weight and low power mode as universally favorable. While the optimal battery varied slightly (battery type 1.0 for and ; type 2.0 for ), the desirability function favored the lighter configuration, aligning with the goal of energy-efficient operation. This alignment across methods highlights the robustness and reliability of the proposed modeling framework for informing sustainable electric vehicle design decisions.

3.5. Discussion

The optimization and modeling approach presented in this study integrates both graphical and numerical strategies to determine the optimal operational conditions for a pilot-controlled electric vehicle, combining experimental data with statistical modeling. The combination of individual response surface models (RSM), graphical contour superposition, and a global desirability function provided a robust framework for multicriteria decision-making across endurance, distance, and energy efficiency.

This study employed a systematic

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and

Desirability Function Approach (DFA) to optimize the performance of an electric racing vehicle, focusing on maximizing output while minimizing energy consumption. Our findings provide valuable insights into the complex interplay among battery type, vehicle mass, and power mode selection in optimizing electric racing vehicle performance. For EV performance, this combined approach enables a thorough evaluation, ensuring that selected solutions—such as those prioritizing low vehicle weight and conservative energy use to maximize endurance, range, and energy efficiency are consistently identified across different analytical perspectives, including individual optimization, graphical contour intersection, and the overall desirability function [

22]. This consistent identification across methodologies reinforces the robustness and reliability of the proposed modeling framework for sustainable EV design decisions [

23].

The experimental results demonstrated that the combination of the lowest battery capacity (1.0), minimum pilot weight (66 kg), and lowest power mode (N5) yielded the highest overall performance in terms of operational time, distance traveled, and energy efficiency. This configuration was confirmed by both individual optimization of each response variable and a global desirability score of 0.945. These results suggest that, under controlled experimental conditions, lightweight configurations combined with conservative power settings significantly enhance the energy efficiency and overall endurance of electric racing vehicles. This optimal point provides a clear guideline for configuring race vehicles aimed at maximizing autonomy without compromising measurable distance or consumption metrics.

The optimization of electric racing vehicles for endurance and energy efficiency involves addressing several key areas across vehicle architecture, powertrain control, energy storage, and thermal management. In the powertrain, Continuously Variable Transmissions (CVT) have been shown to outperform fixed-gear transmissions (FGT) in lap time, despite increased mass and potential efficiency losses, by keeping electric motors operating within optimal efficiency zones [

24,

25]. Motor sizing is also critical; in-wheel motor double-axle (IWM-DA) configurations offer superior acceleration, while single-axle (IWM-SA) designs balance performance and control [

25,

26]. Switched Reluctance Motors (SRM) are gaining interest due to their high torque density and robust design, with control strategies focused on minimizing torque ripple [

23,

27]. For induction motors, loss-minimizing algorithms that optimize the d-axis stator current reduce energy losses during operation [

28].

Battery and energy management strategies are equally important. Vehicles using CVTs benefit from larger-capacity batteries [

25], while improvements in electrode structure—such as optimizing thickness and porosity—can increase lithium-ion battery energy density by over 50% [

29]. Efficient thermal management, employing systems like air cooling, liquid cooling, phase-change materials, or Peltier devices, is essential to ensure performance and extend battery life [

30,

31]. Charging optimization strategies based on telemetry data and RSM can significantly reduce recharge times while controlling thermal rise [

32]. Finally, vehicle mass reduction continues to be a priority for optimizing performance, as supported by findings on mass-energy correlations in electric racing [

33,

34].

From individual optimization of each response variable, it was evident that the configuration that yields the maximum operational time (), the distance traveled () and the energy efficiency () consistently involved the use of a light battery (Battery type 1.0), the lowest pilot weight (66 kg), and the lowest power mode (Mode 5). An exception occurred in the distance optimization, where the highest value was achieved using a Battery type 2.0. This discrepancy suggests a trade-off between energy efficiency and energy capacity, confirming that while lighter batteries enhance efficiency and duration, greater range may benefit from increased stored energy.

The graphical method using contour plot superposition (

Figure 8) supported these findings, visually revealing a convergence region where all three objectives perform optimally under similar low-level factor settings. This graphical consistency with the numerical optimizations strengthens the argument for using RSM and contour plots as complementary tools for validating and refining vehicle performance models during early stage design and calibration.

Furthermore, the application of the global desirability function yielded an optimal configuration identical to the one predicted by individual analyzes: Battery type 1.0, Weight 66 kg, and Mode 5. The predicted performance at this configuration was 1.121 hours of operation, 23.71 km of total distance, and 2.90 km/Ah in energy efficiency, with a global desirability score of 0.945. This reinforces the consistency and reliability of the methodology employed.

These findings are consistent with recent studies in the field of electric vehicle performance optimization. For instance, in the work of [

35], the mechanical and structural configuration of an electric competition vehicle was explored, highlighting the importance of weight and structural optimization to improve vehicle behavior under dynamic and static loading conditions. Additionally, the study by [

32] emphasized the integration of telemetry in real-time to refine battery performance prediction, revealing the significance of battery selection and control strategy for racing scenarios. Similarly, the application of machine learning for telemetry-based efficiency optimization, as demonstrated in the work by [

34], underlines the growing relevance of predictive modeling to support electric vehicle design and usage decisions.

The proposed methodology provides a replicable and data-driven framework for optimizing electric vehicle performance through experimental modeling and statistical analysis. It bridges design, operation, and data-based decision-making, aligning with emerging trends in sustainable, intelligent, and competitive electric mobility development.