The transition toward electric mobility is accelerating globally, driven by a need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve urban air quality, and reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

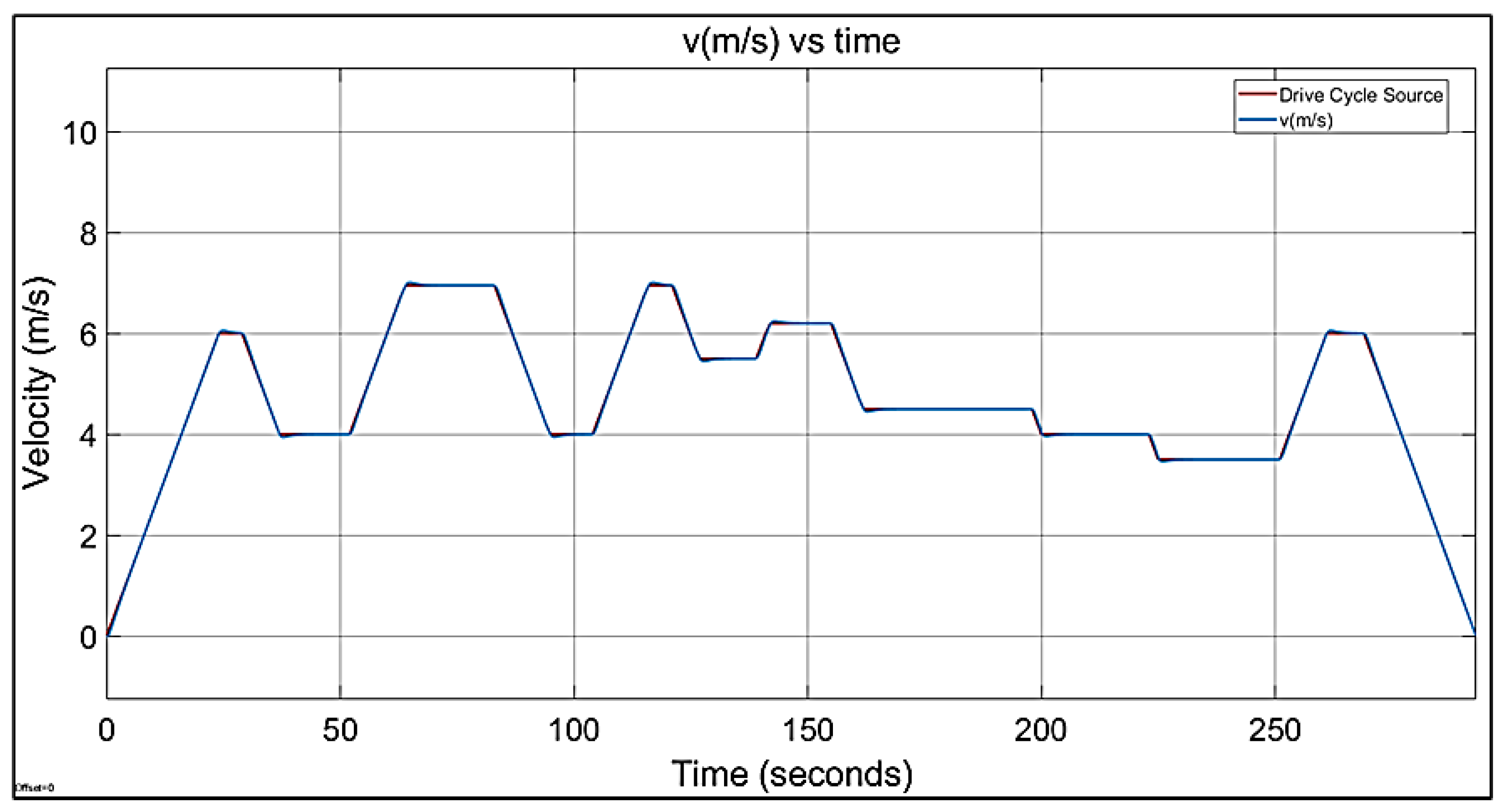

The Shell Eco-marathon competition provides a platform for academic teams to explore innovations in vehicle design under strict regulatory and performance constraints. This study focuses on the Urban Concept category, which emulates real-world driving conditions such as stop-and-go traffic and packaging constraints like passenger cars.

Despite increasing interest, detailed documentation of EV powertrain solutions that are both cost-effective and performance-validated remains limited. This project addresses that gap by delivering a fully documented electric drivetrain that integrates motor, transmission, battery, and control systems within competition constraints.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), electric vehicles (EVs) are expected to account for over 30% of global vehicle sales by 2030 (IEA, 2024). In this context, there is increasing pressure on engineers and designers to develop powertrains that are not only energy-efficient and reliable but also lightweight, cost-effective, and practical for real-world, low-speed applications such as micro-EVs and delivery vehicles.

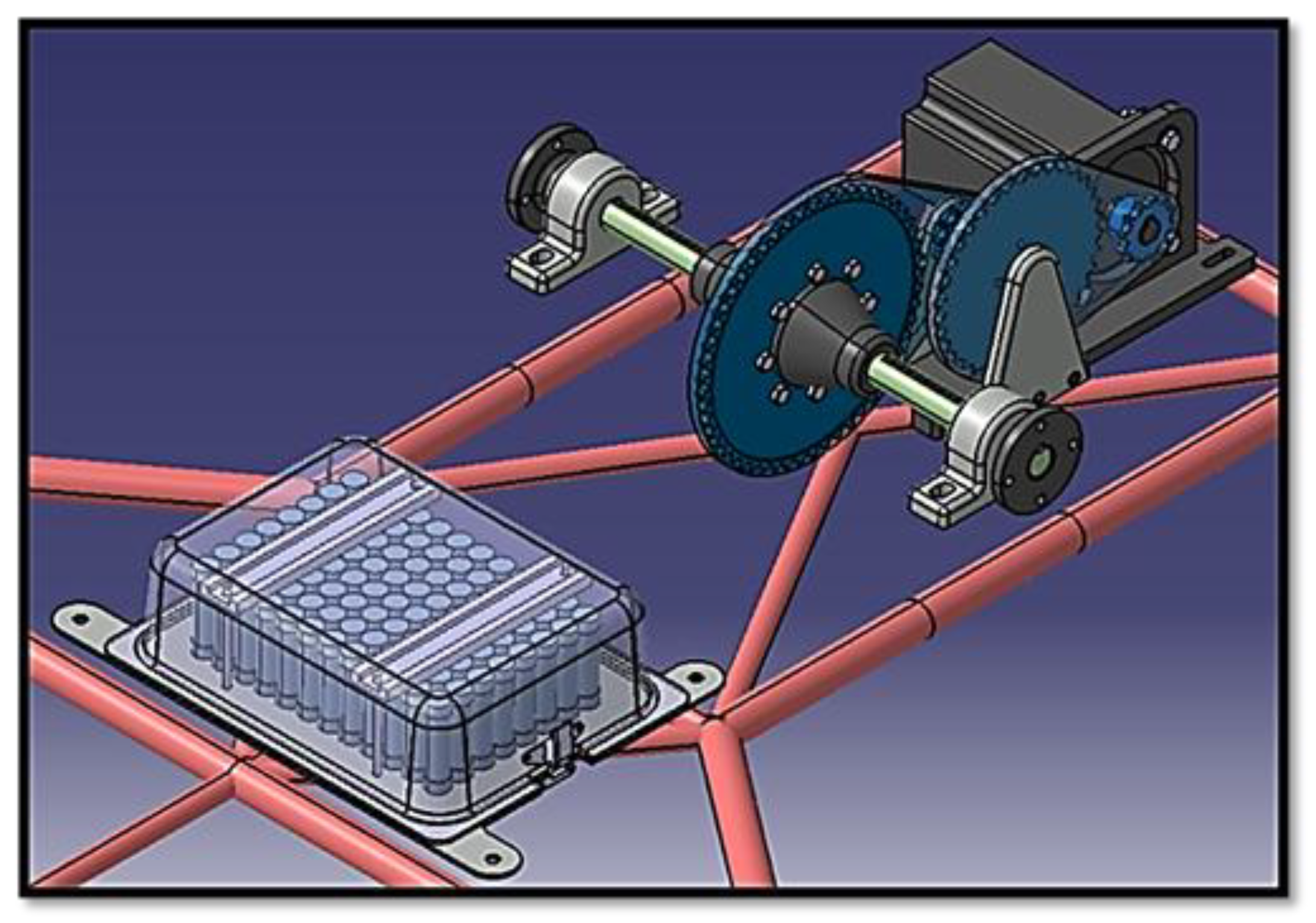

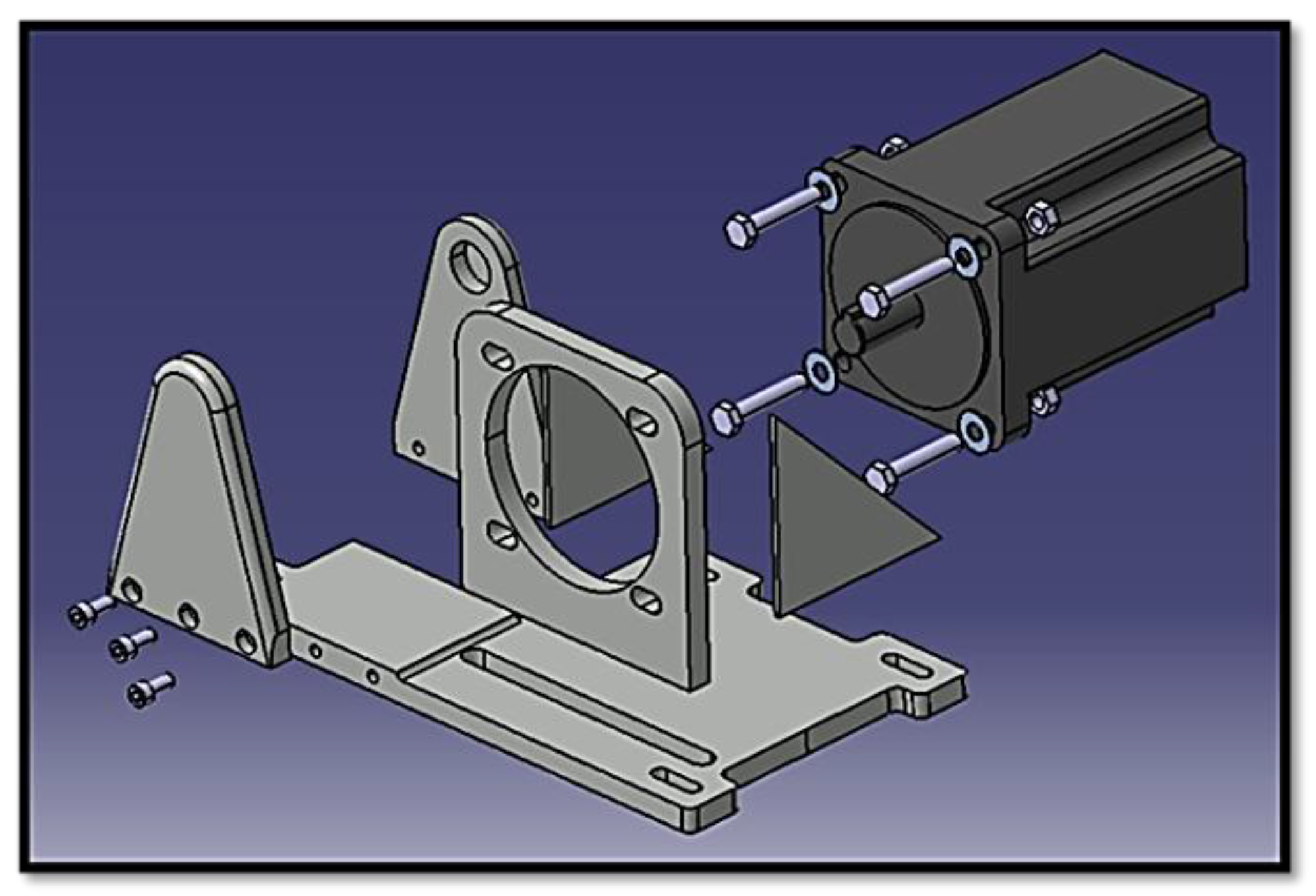

Within this environment, student teams are encouraged to balance innovation, safety, and manufacturability. The BA Momentum team from Coventry University undertook the development of an open-source, electric Urban Concept vehicle with critical design constraints: a 48 V voltage cap, a total budget of £13,500, and a tightly packaged lightweight chassis. These parameters mirror trade-offs seen in commercial micro-mobility solutions.

Research Gap and Motivation

While past research has addressed EV component selection and lightweight body design (Cichoński et al., 2014; Maria Maia Marques Líbano Monteiro et al., 2021); few studies offer an integrated drivetrain solution combining rigorous selection methodology, simulation-driven validation, and practical packaging for constrained environments. Moreover, there is a lack of detailed documentation on low-voltage drivetrain architectures optimized for both energy efficiency and manufacturability within academic projects.

Designing a high-efficiency electric powertrain for Shell Eco-marathon Urban Concept vehicles requires a system engineering approach that spans motor selection, drivetrain configuration, battery optimisation, and simulation-driven validation. Literature in this area highlights the engineering challenges and evolving best practices in developing low-voltage, lightweight electric vehicles under cost and regulatory constraints.

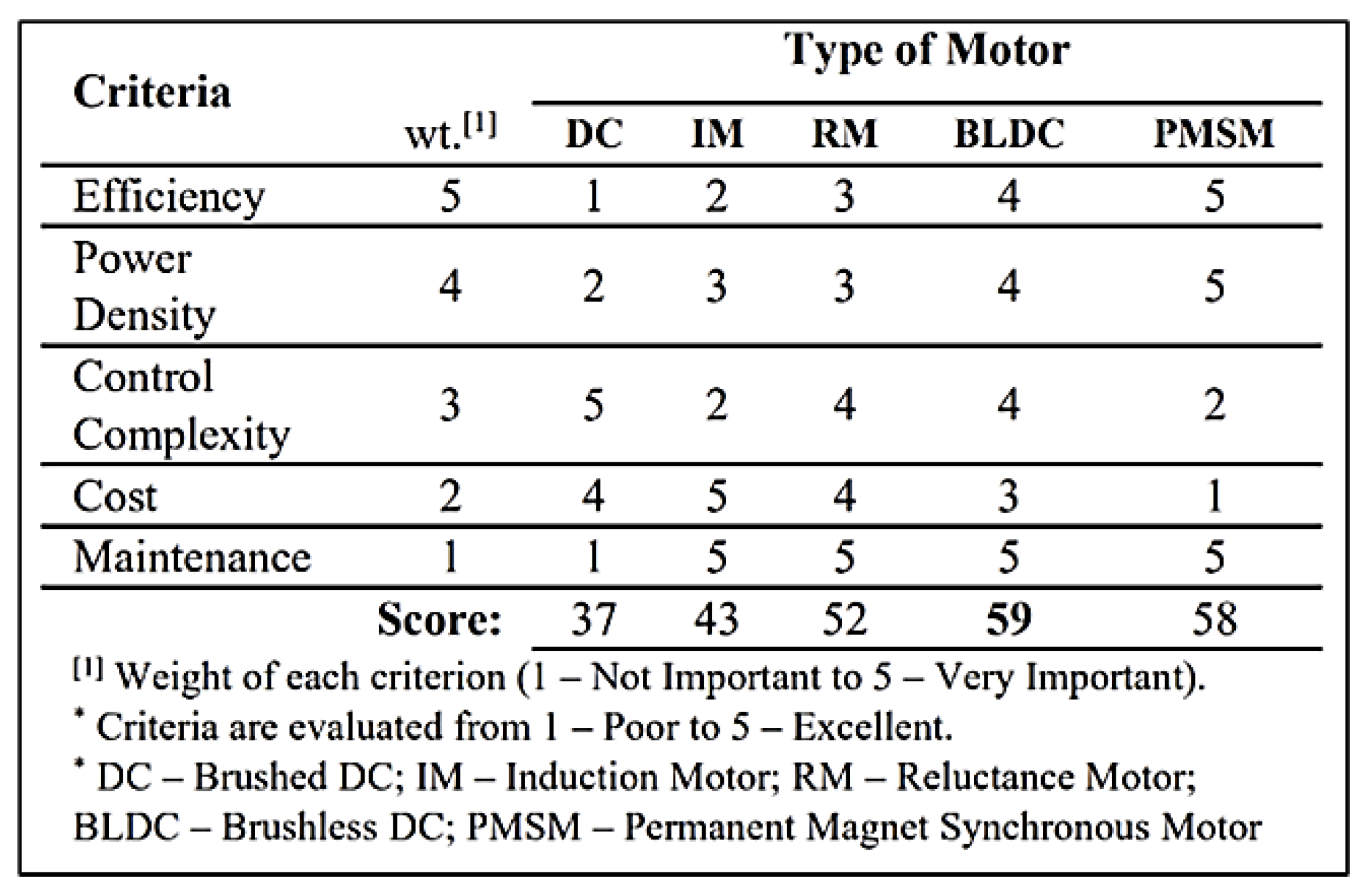

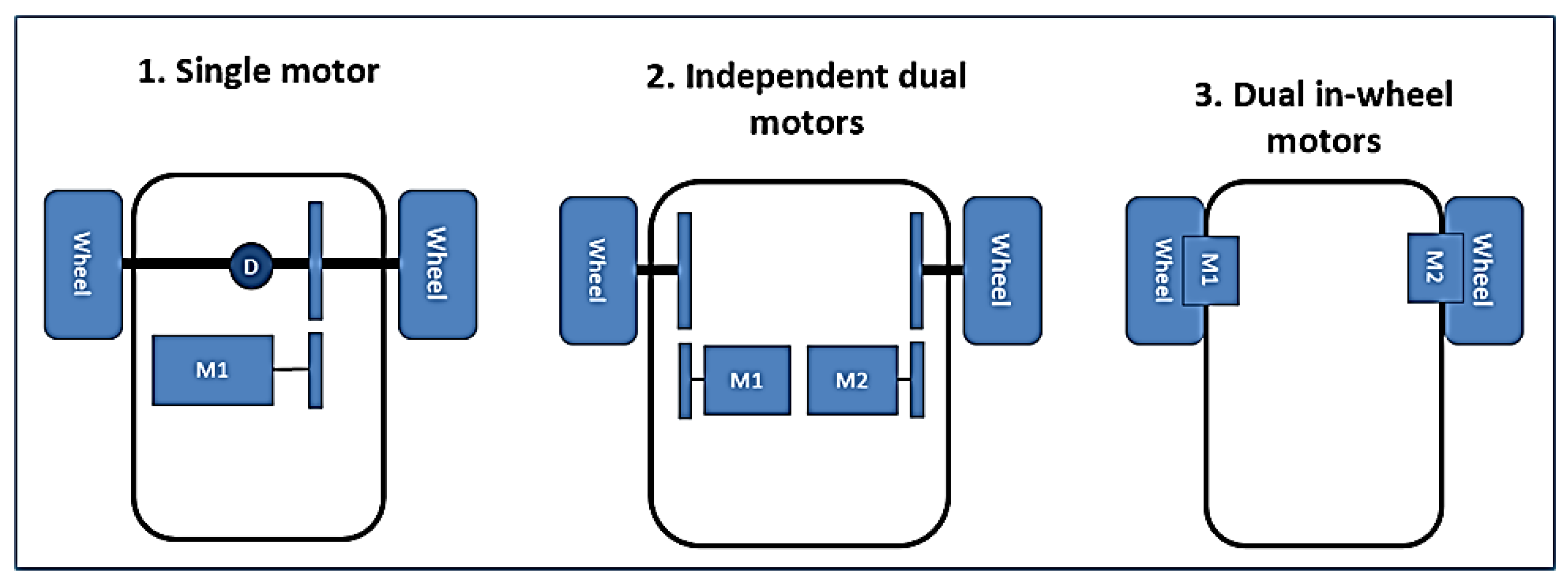

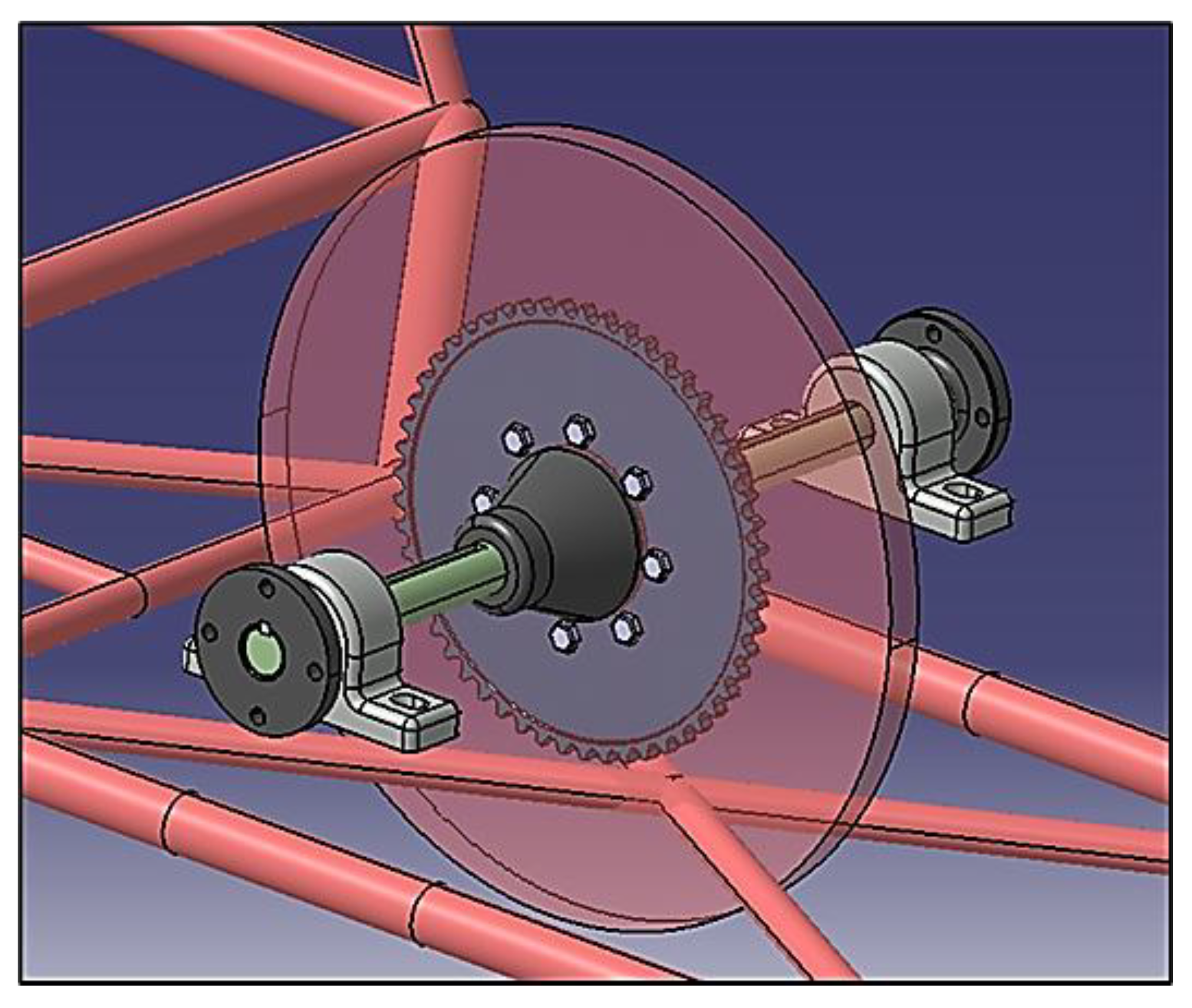

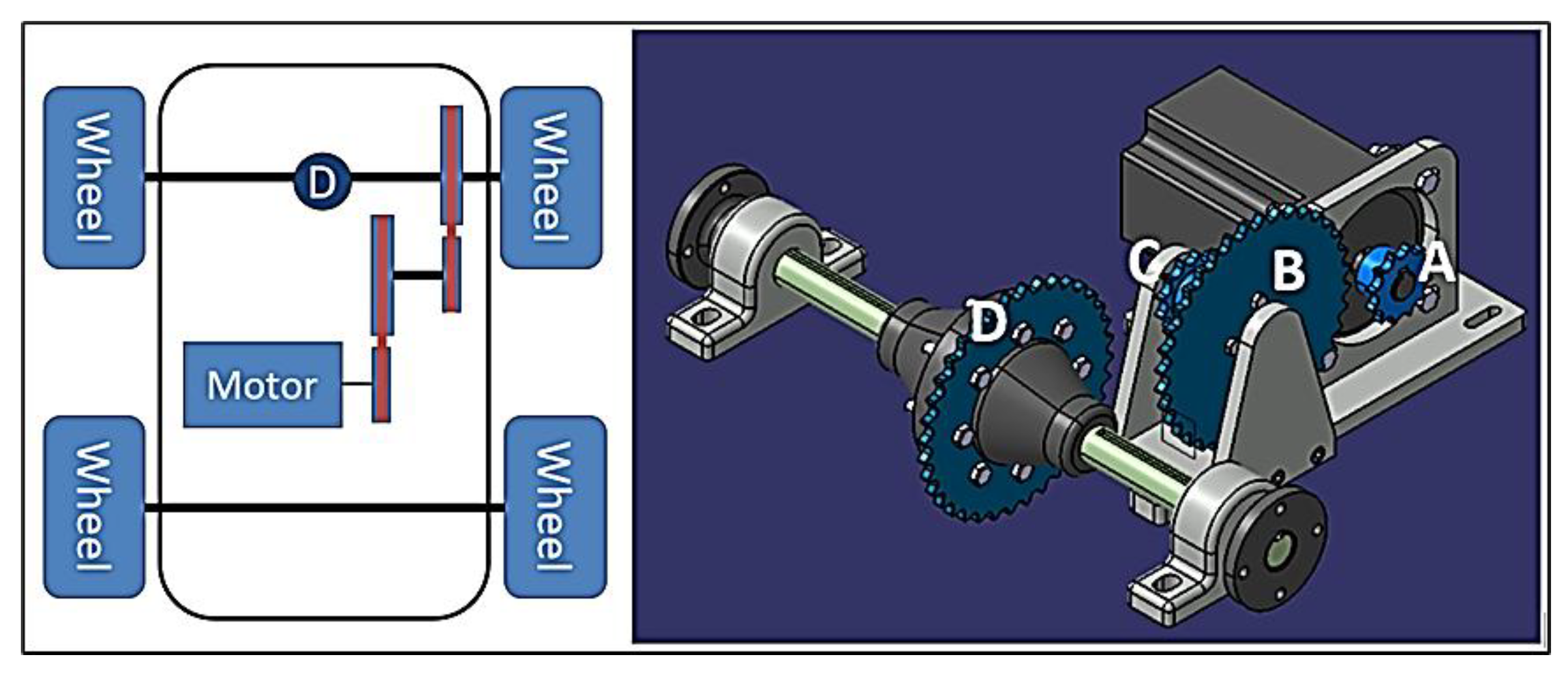

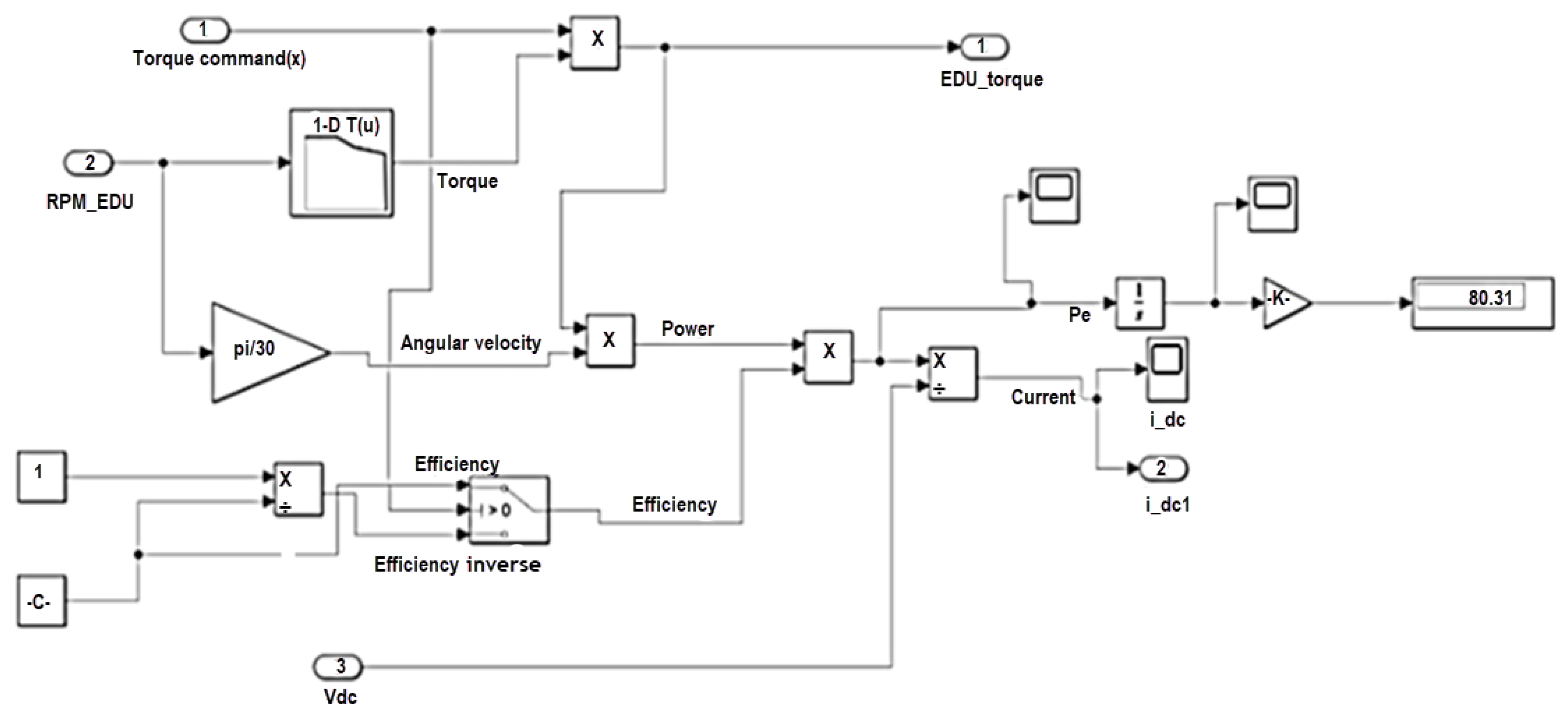

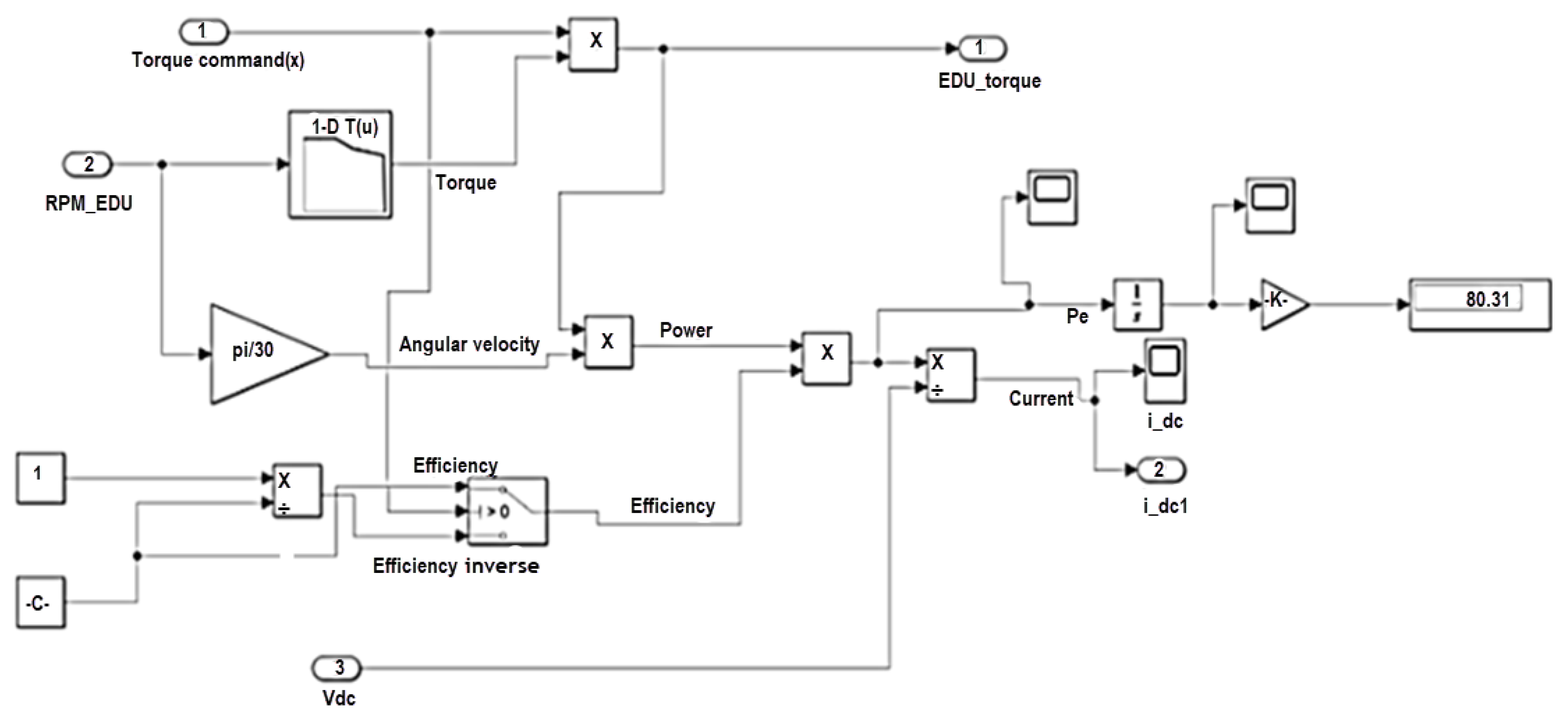

Motor selection is one of the most critical factors influencing drivetrain performance as shown in

Figure 1. Brushless DC (BLDC) motors are commonly adopted due to their high efficiency (>90%), compact form factor, and simple control requirements (Bhatt, Mehar and Sahajwani, 2018). In a comparative study by Monteiro et al. (2021), five motor types brushed DC, induction, reluctance, BLDC, and PMSM were evaluated using multi-criteria analysis. (Maria Maia Marques Líbano Monteiro

et al., 2021) conducted a comprehensive evaluation of motor types and concluded that BLDC motors provide an optimal balance between efficiency, cost, and reliability for student-built competition vehicles as shown in

Figure 1 below. The five motor types evaluated were brushed DC motors, induction motors, reluctance motors, BLDC motors, and PMSMs. Based on key criteria including efficiency, power density, control complexity, cost, and maintenance requirements, BLDC motors achieved the highest overall score. However, the study also indicated that if cost is not a limiting factor, Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) can outperform BLDC motors, making them the preferred option for applications prioritizing maximum performance.

Recent developments have introduced axial flux motors with higher power density and thermal efficiency (Shao et al., 2021; Hao et al., 2022). However, their integration into student prototypes remains limited due to cost and manufacturing complexity. Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) are also gaining traction, offering smoother torque profiles and better performance under variable loads, particularly in multi-speed or urban stop-and-go conditions (Simon Fekadeamlak Gebremariam and Tebeje Tesfaw Wondie, 2023).

Motor layout and powertrain configuration also significantly impact vehicle performance. While multi-motor systems like quad in-wheel motors enable advanced control and regenerative braking (Taha and Aydin, 2022), they introduce substantial challenges in terms of weight, complexity, and unsprung mass (Deepak et al., 2023). Most academic and competition-based designs favour single or dual-motor setups, which are easier to implement and maintain. Centralized motor configurations remain the most practical for student teams, offering an efficient compromise between system simplicity and energy efficiency (Łebkowski, 2017).

In-wheel motor technology was studied extensively by Jneid and Harth (2023). In an in-wheel motor drivetrain, electric motor is installed inside the wheel and drives the wheel directly without the need of driveshaft, differential or transmission, which results in high efficiency due to the lack of mechanical losses from these components. The absence of these components also reduces weight and frees up more space for passengers and batteries, which increases the practicality of the vehicle. With individual motors controlling each driving wheel, performance can be enhanced through precise torque control. However, the drawback of this motor configuration is the unsprung mass it adds up to, since the motors are installed inside the wheels, which increases the driven element mass, hence the overall inertia of the vehicle. In addition, the simpler mechanical layout of the drivetrain means that it requires a more complex electronic control system.

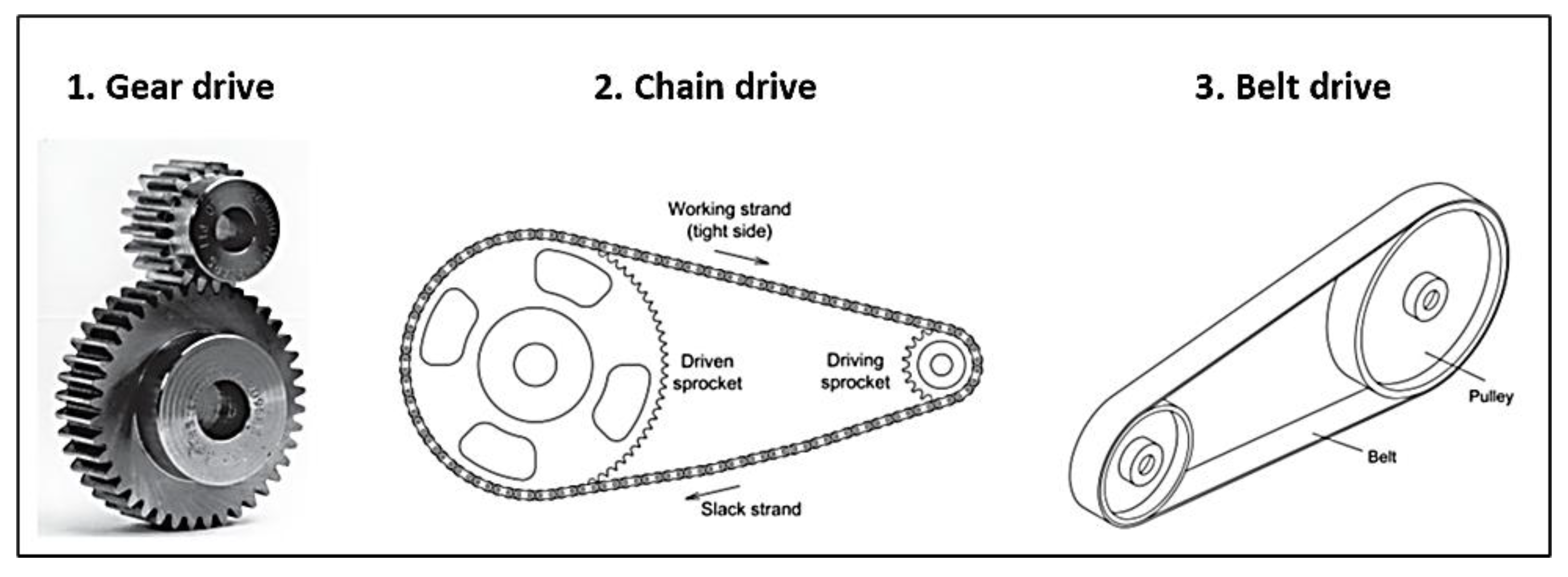

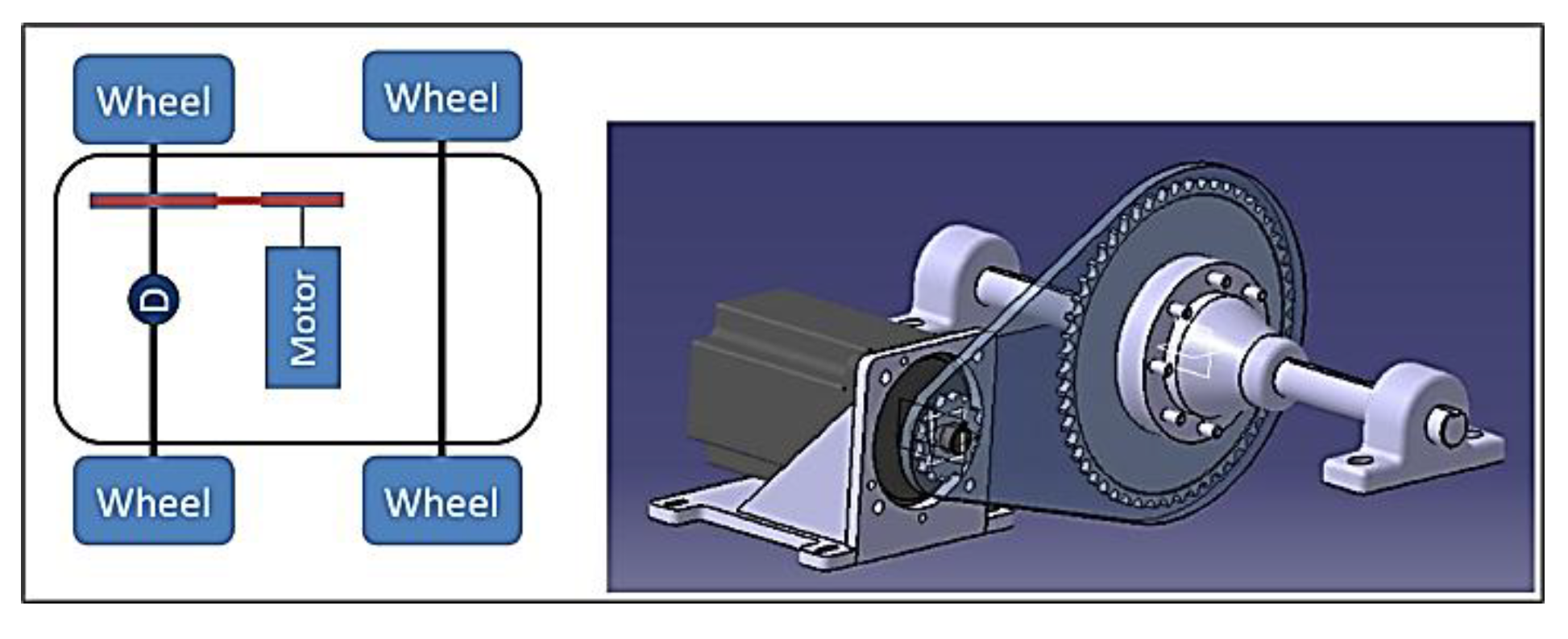

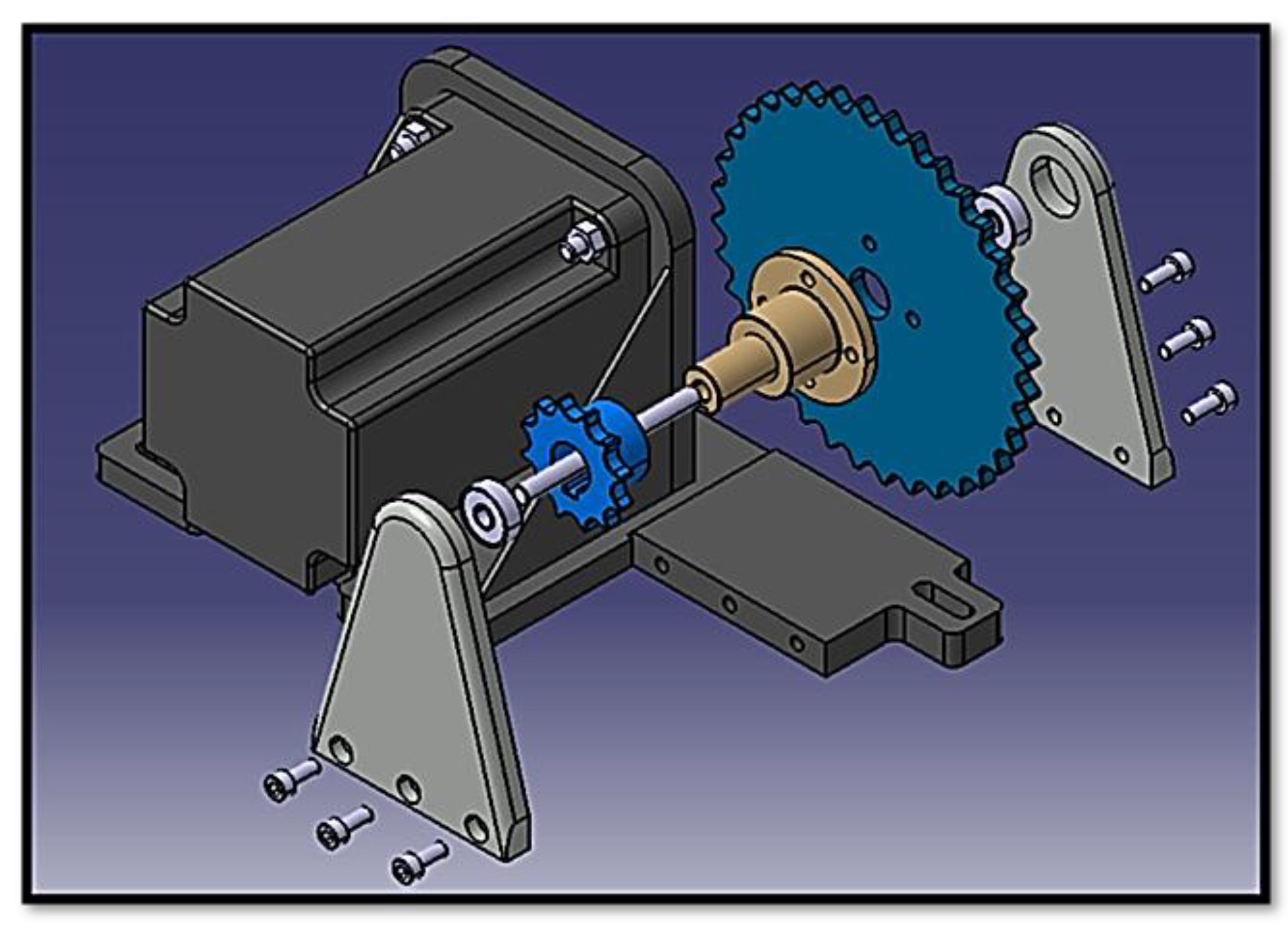

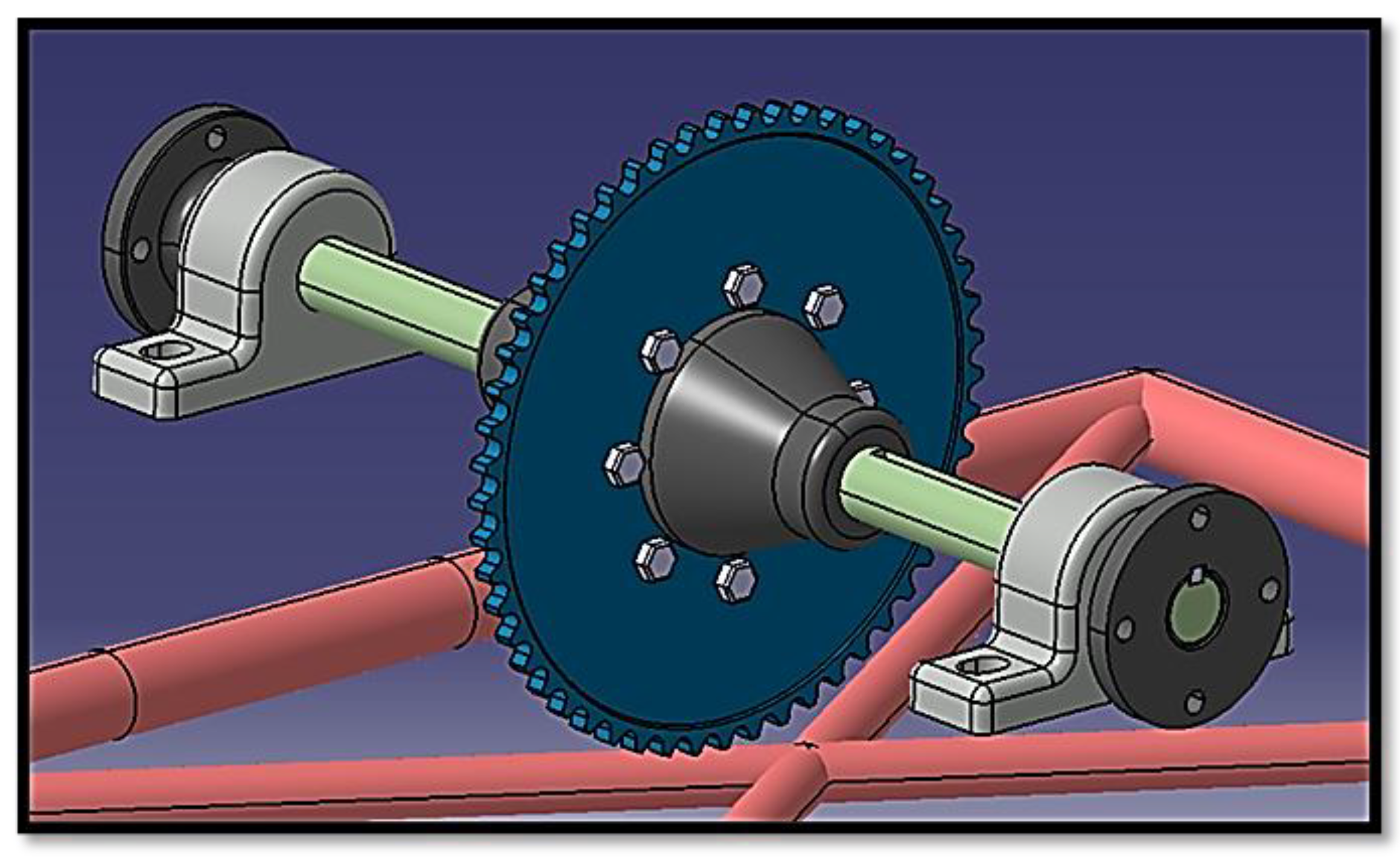

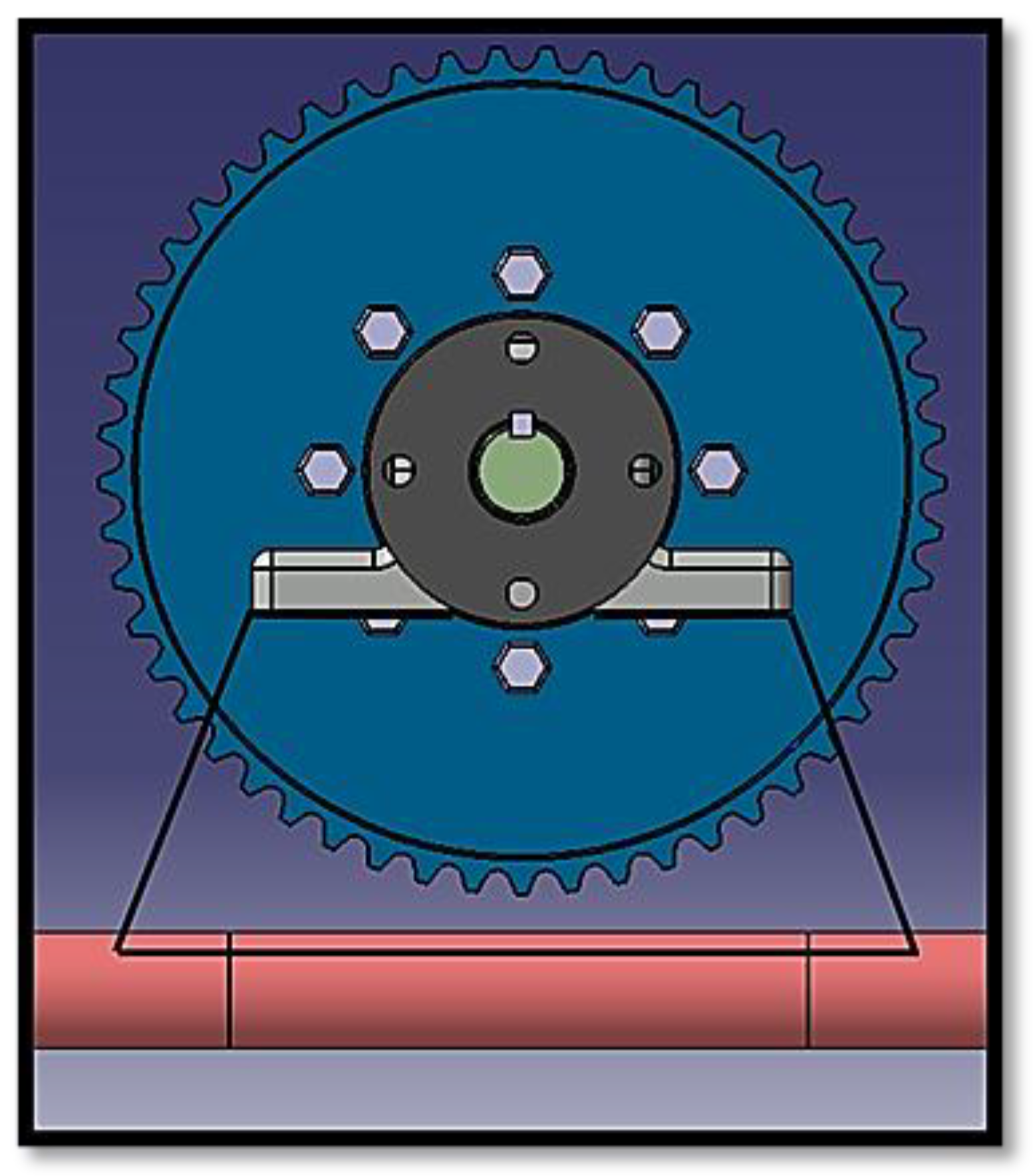

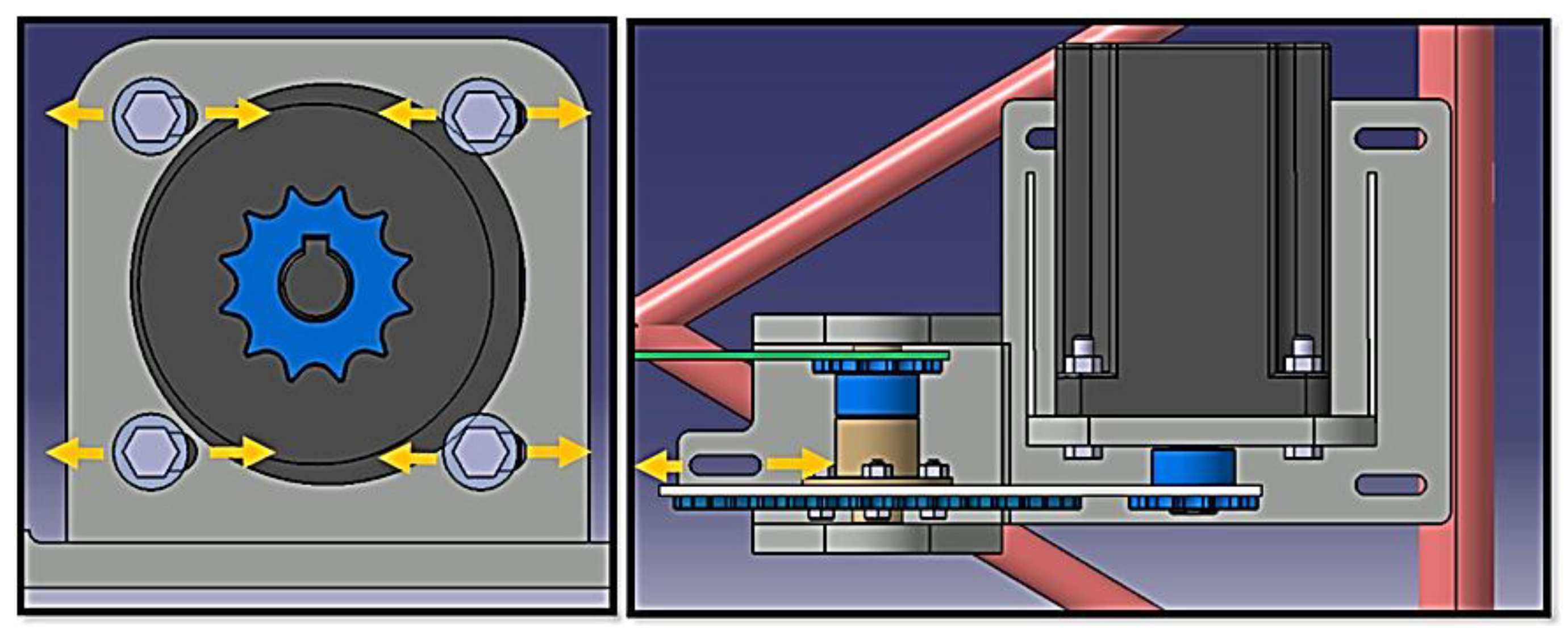

Drivetrain design choices, particularly the type of mechanical transmission, play a central role in overall energy efficiency. Examples of drivetrain designs from other Shell Eco-marathon teams were studied in this section.

A team from the Silesian University of Technology in Poland conducted a comparative study (Cichoński et al., 2014) on drivetrain designs on their Urban Concept vehicle using MATLAB software. Two designs were involved in the study.

By running the drivetrains from the speed of 0 to 30 km/h at constant torque of 4 Nm and 9 Nm, it was found that the in-wheel motor design performed better in efficiency throughout the measuring range in both scenarios.

Gear drives provide the highest efficiency approximately by 99.9% but are less suitable for rapid prototyping due to fabrication constraints (Hatletveit and Aasland, 2018). Chain drives, widely used in Shell Eco-marathon vehicles, offer mechanical efficiency of around 98% and allow for easy modification of gear ratios (Smit et al., 2023). Adaptive chain tensioning, as investigated by (Dai et al., 2022), can further enhance drivetrain efficiency under variable loads. Hybrid transmission designs, such as those combining belt and gear stages, are emerging as viable alternatives for micro-mobility applications (Jacoby et al., 2015). Spicer et al. (2001a) experimentally demonstrated that doubling sprocket ratios increased chain efficiency by 2–5%, and quadrupling chain tension improved it by 18%. Meanwhile, belt systems showed 34.6% higher frictional losses compared to chain drives under equivalent preload (Friction Facts, 2012).

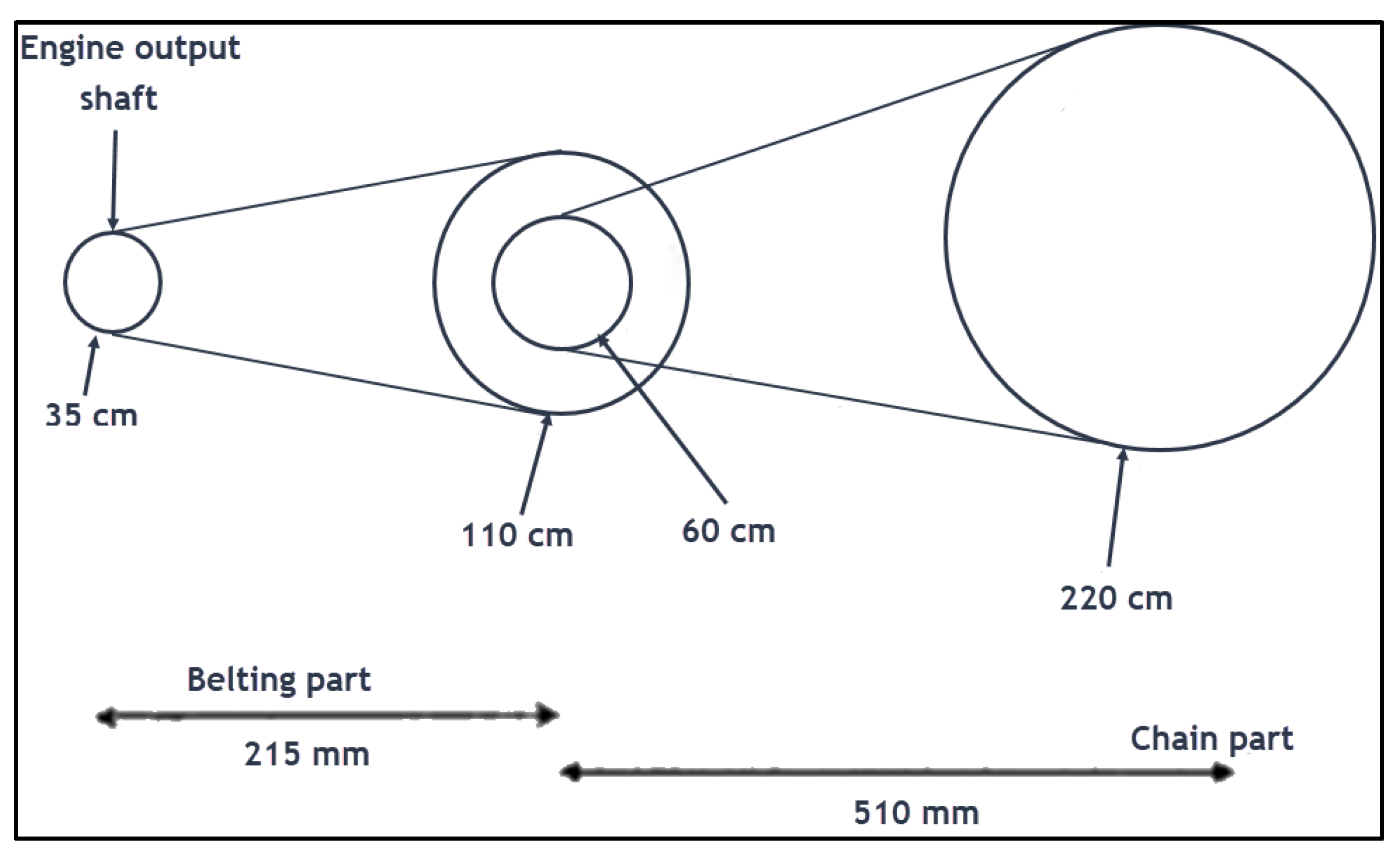

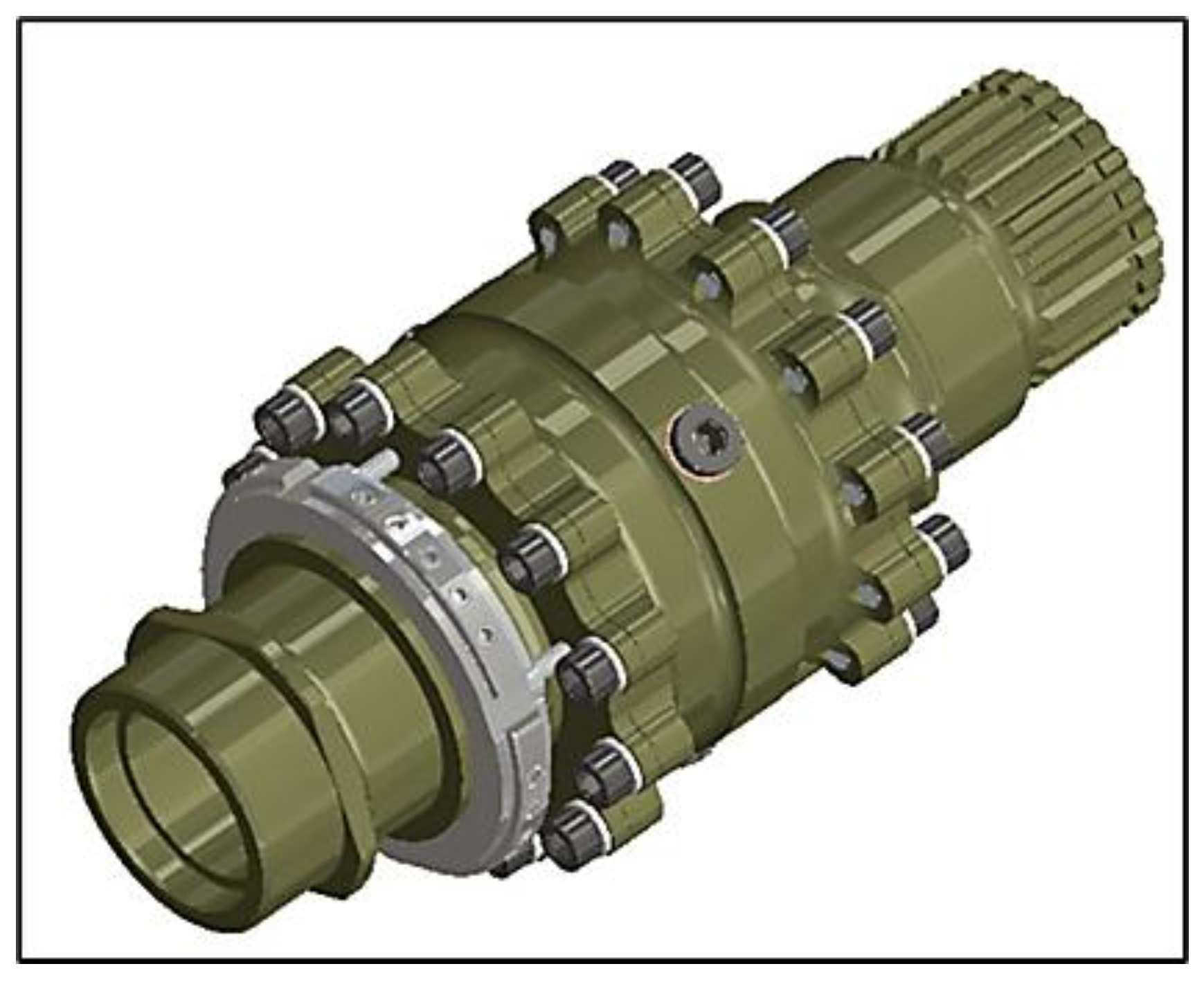

Multi-stage transmissions offer a promising middle ground. The PETRONAS University of Technology team addressed chain breakage issues by introducing a hybrid drivetrain with a belt stage for high-torque loads followed by a chain stage for moderate-speed transmission (Haron, 2011). Their design reduced strain on the chain and allowed better durability under dynamic loads. Dai

et al. (2022) also demonstrated how adaptive chain tensioning can further improve drivetrain efficiency under variable loading. It was mentioned that the vehicle equipped with chain drive system from previous year suffered from chain breakage, as the chain was connected directly to the engine output shaft and transmission, and the direct load from the engine exceeded the load capacity of the chain. To address the issue, the team designed a two-stage transmission – the first stage being a belt system which had the ability to sustain the high rotation speed and torque directly from the engine, whereas the second stage being a chain system that was more reliable at lower rotation speed and torque. A diagram of their design was given in

Figure 2.

In a study by Spicer et al. (2001), frictional losses in a bicycle chain drive were analysed through experimentally measuring its efficiency. It was found that chain drive efficiency increased with tooth ratio and chain tension, results from their experiments showed a 2-5% increase in efficiency when doubling the sprocket ratio, whilst quadrupling the chain tension raised efficiency by 18%. The maximum efficiency recorded was 98.6%. Even though the belt was less efficient than the chain in low load application because of the high pretension required in belt, it was found that belt could have less frictional losses if the pretension remained under 40lbf.

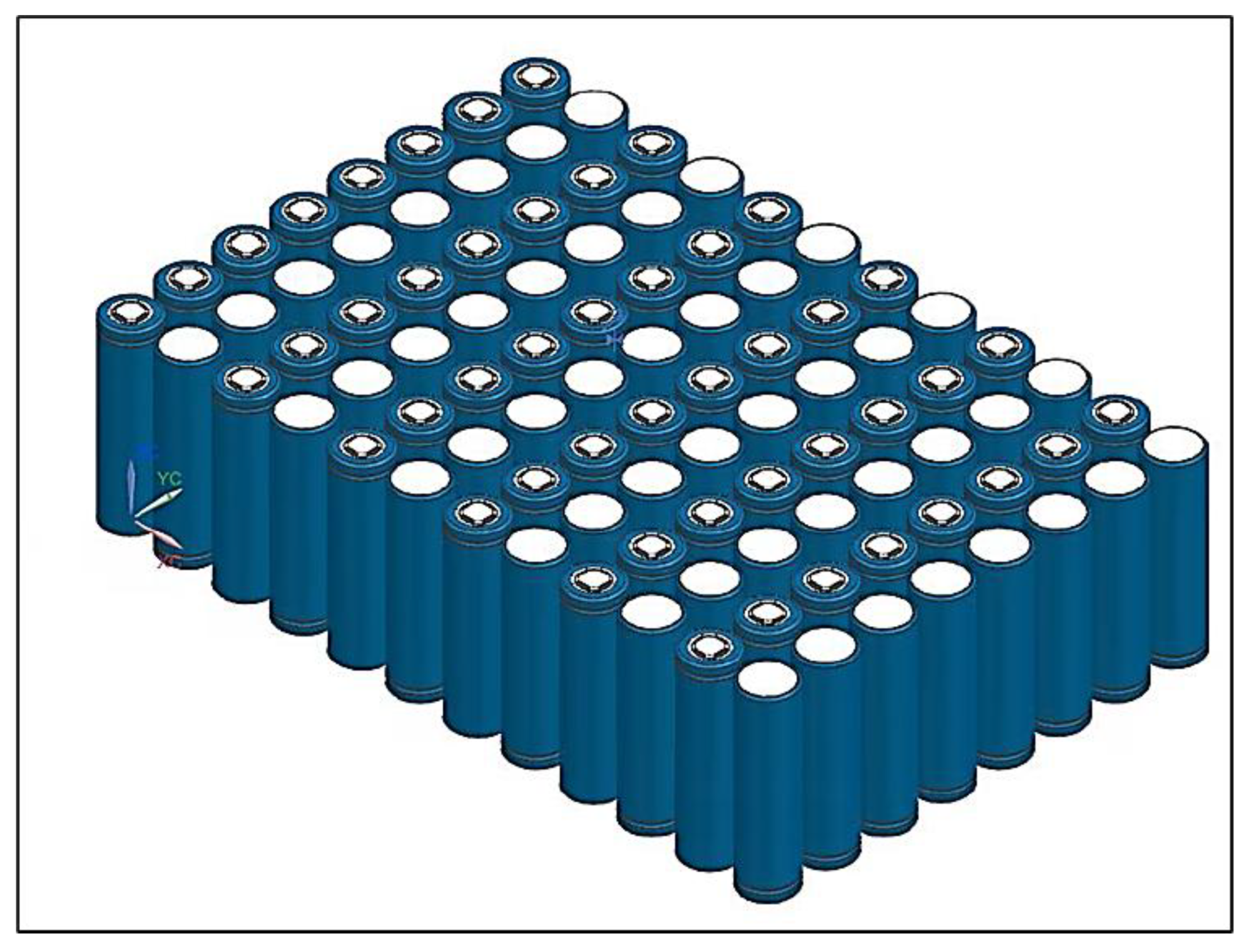

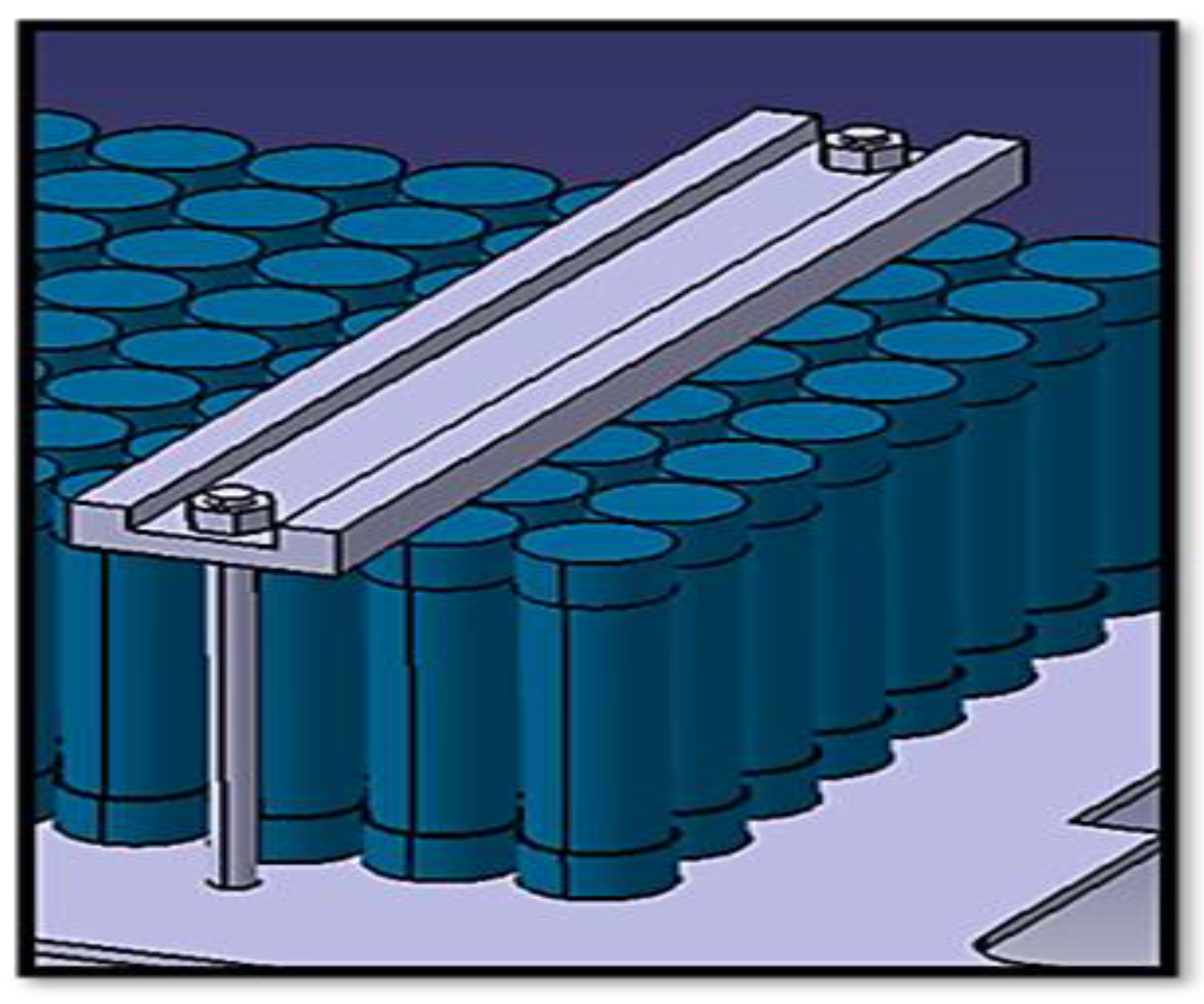

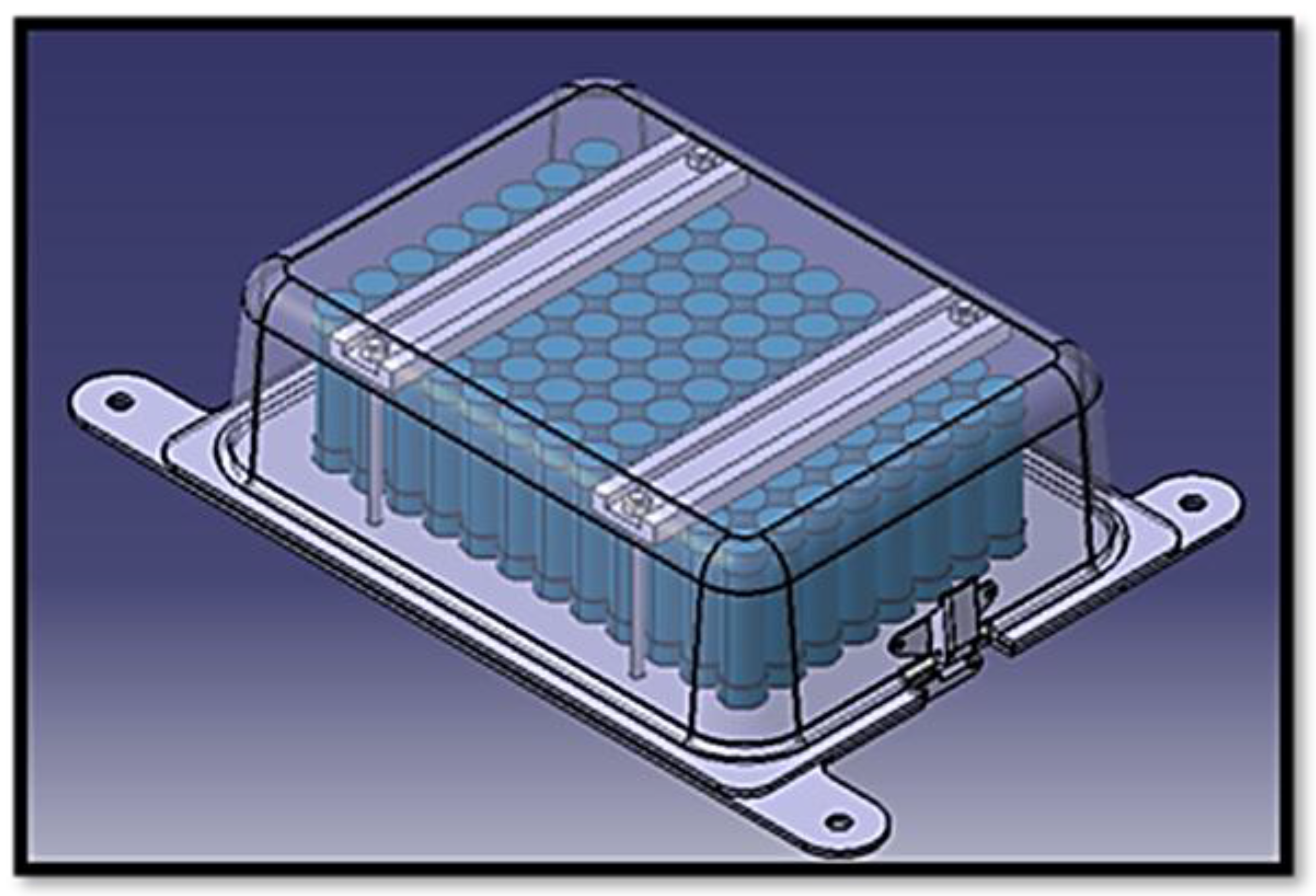

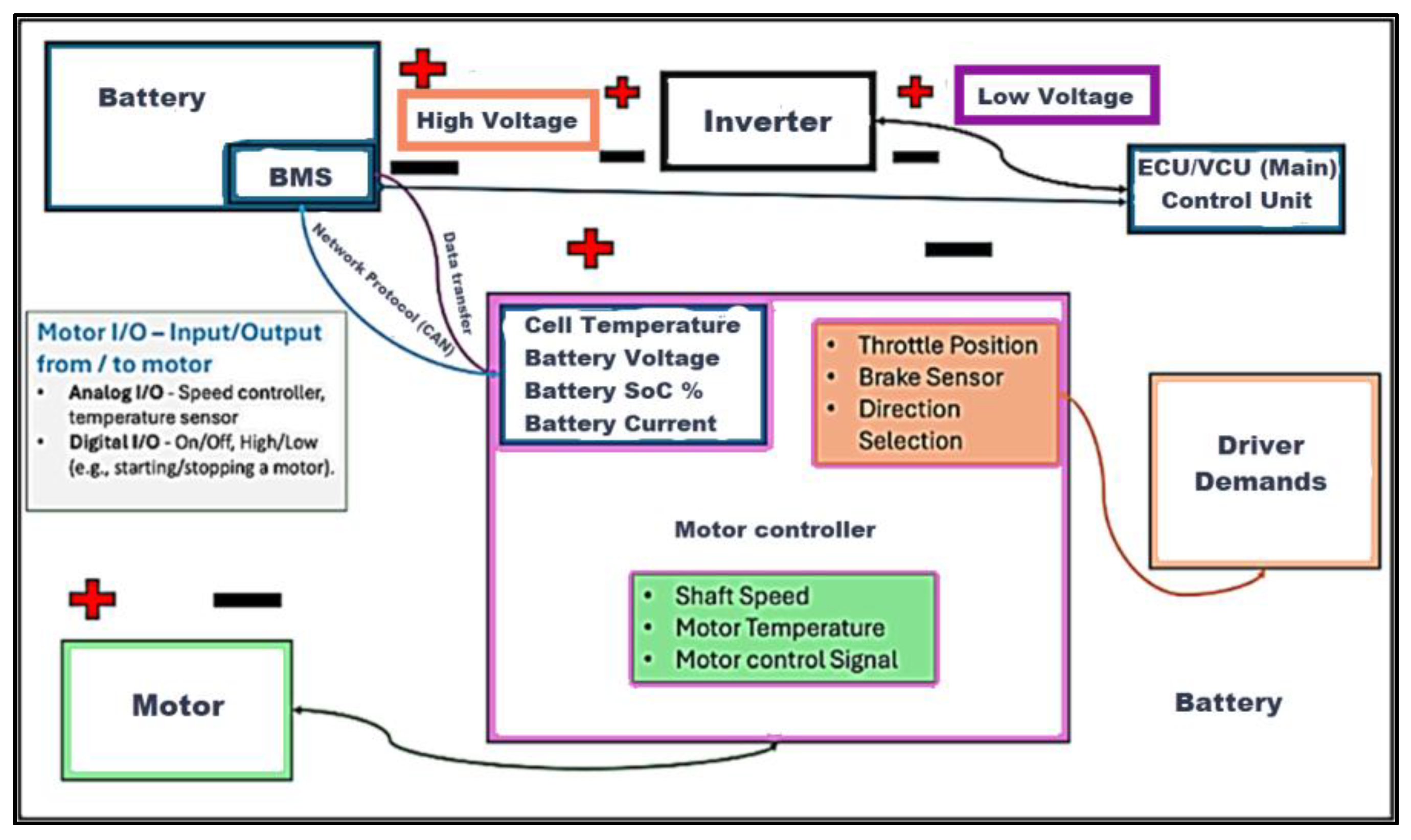

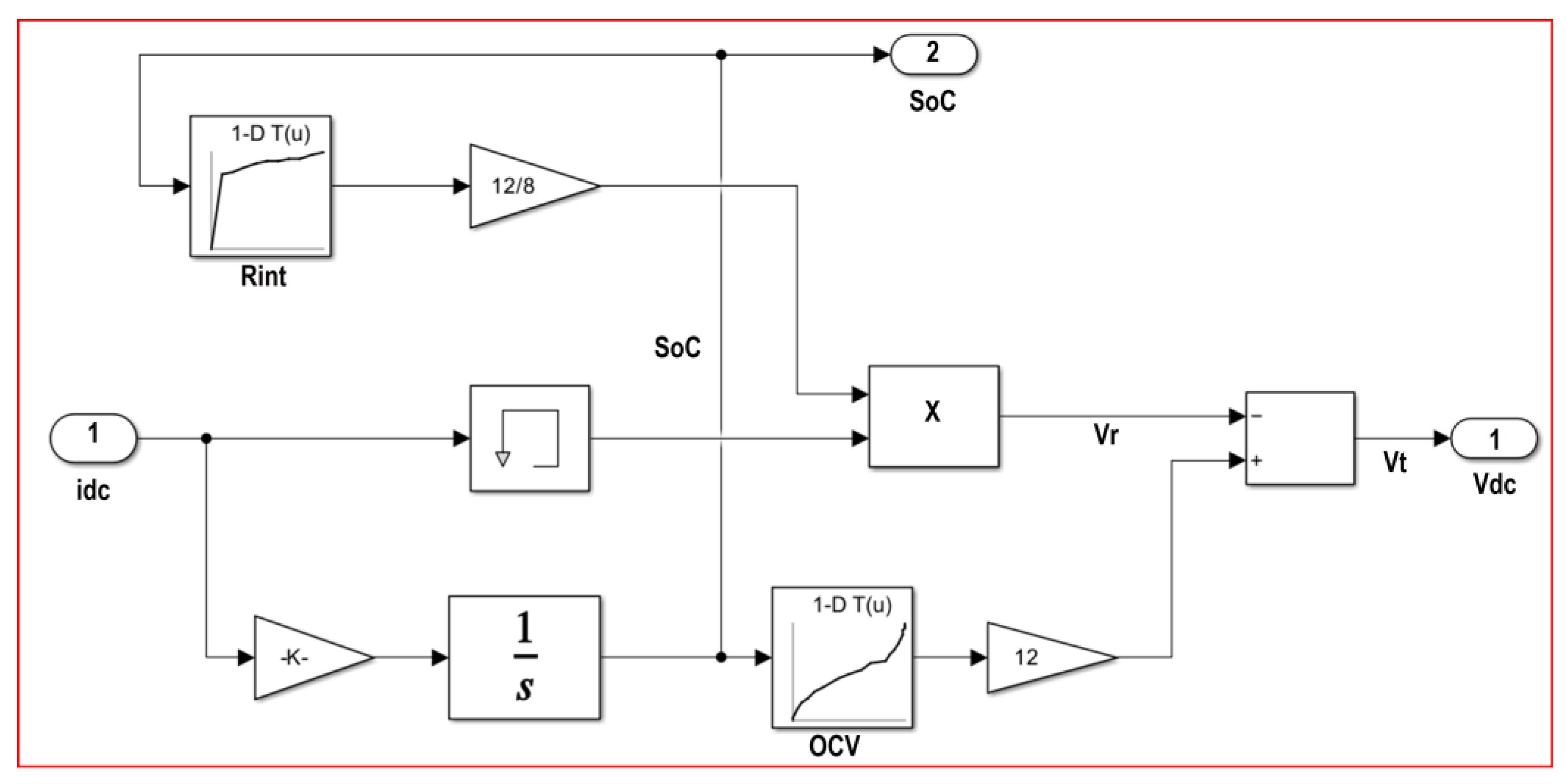

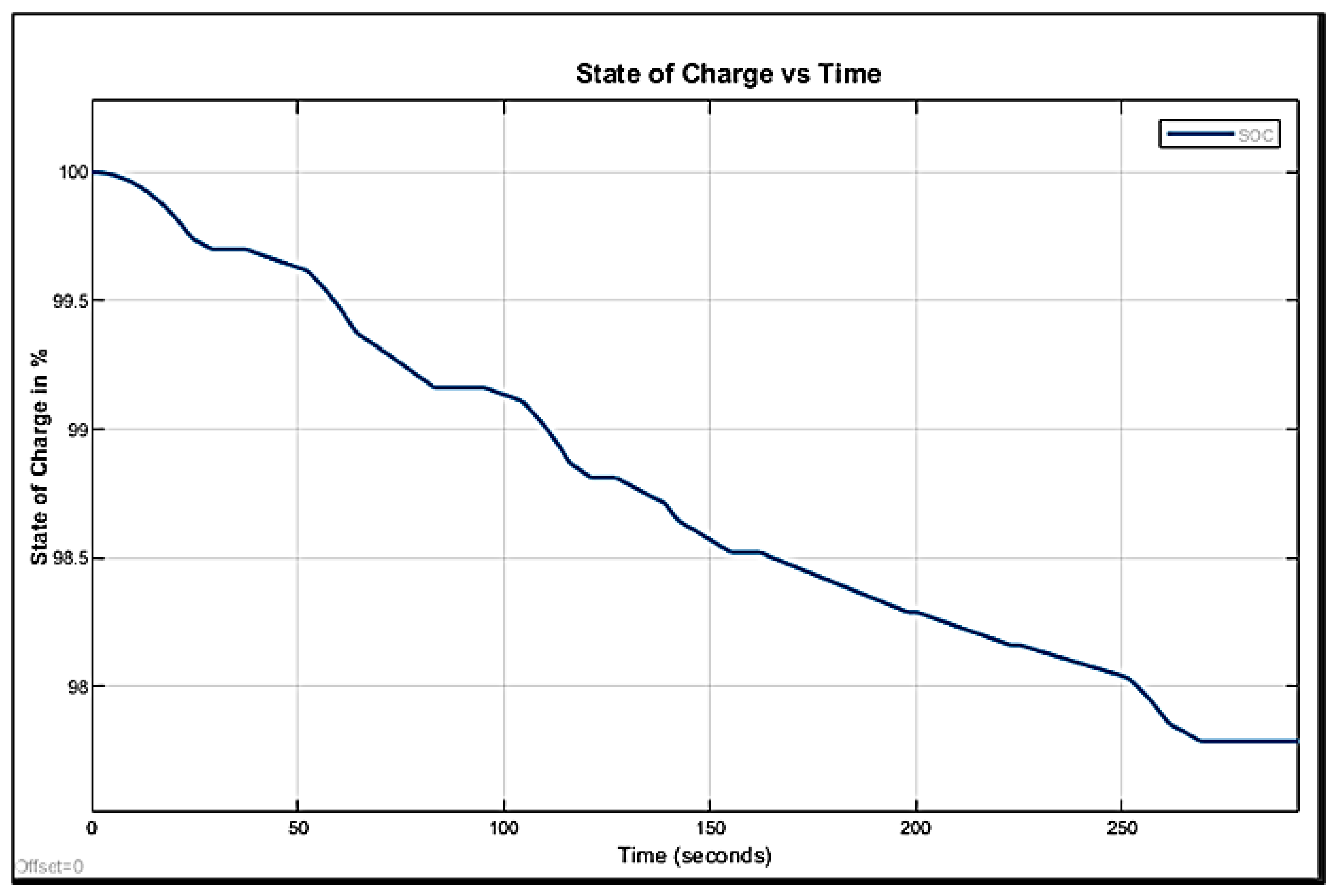

Battery selection and modelling are equally crucial. Lithium-ion cells, such as the Molicel P28A, are widely chosen for their high discharge rates and energy density. (Zhang et al., 2018) and (Patil et al., 2020) emphasize that accurate modelling of state-of-charge (SoC), internal resistance, and thermal effects is essential for predicting battery behaviour and range. Thermal modelling, although often excluded from student projects due to complexity, can significantly improve the fidelity of energy simulations. Battery management system (BMS) design, safety tray construction, and compliance with voltage limits (<60V) are also key design considerations in competition settings (Tu et al., 2024).

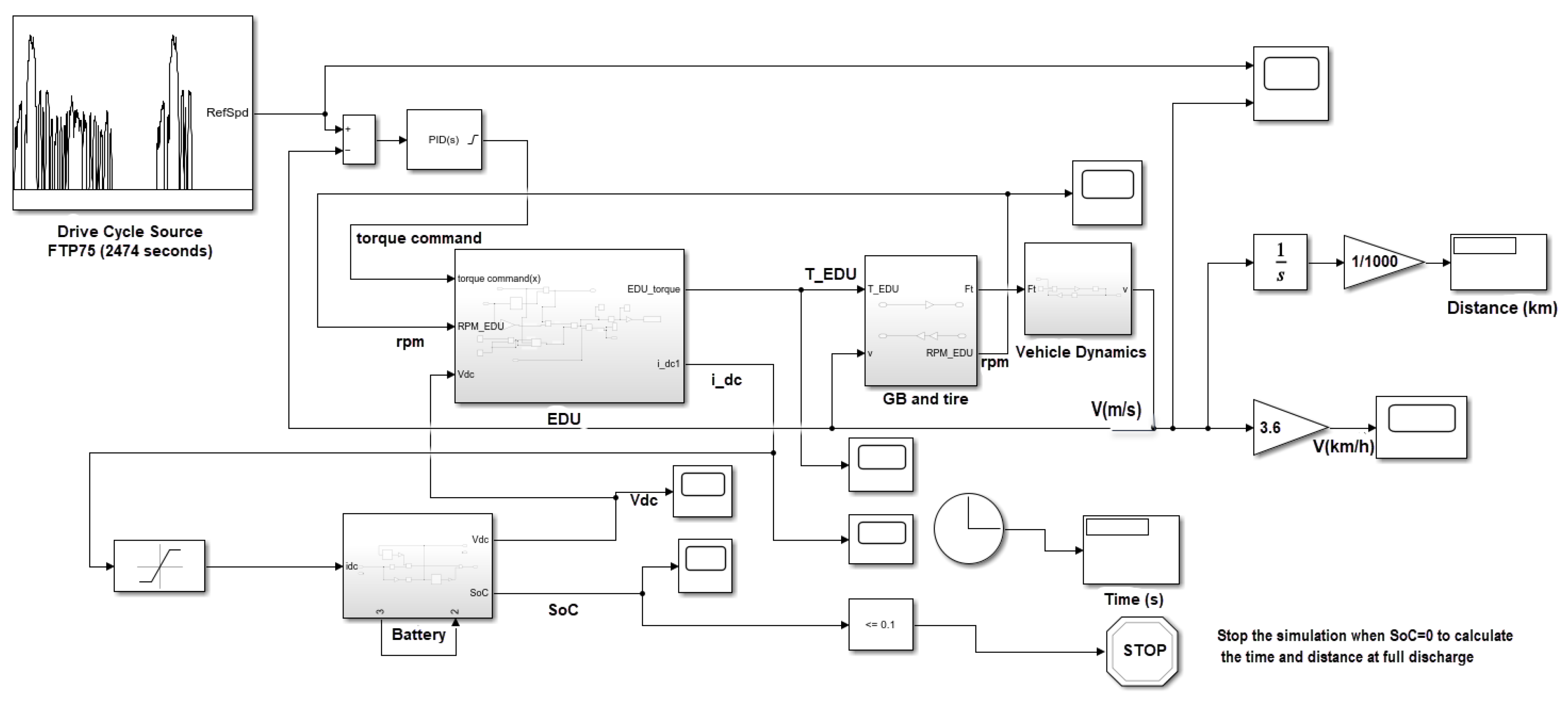

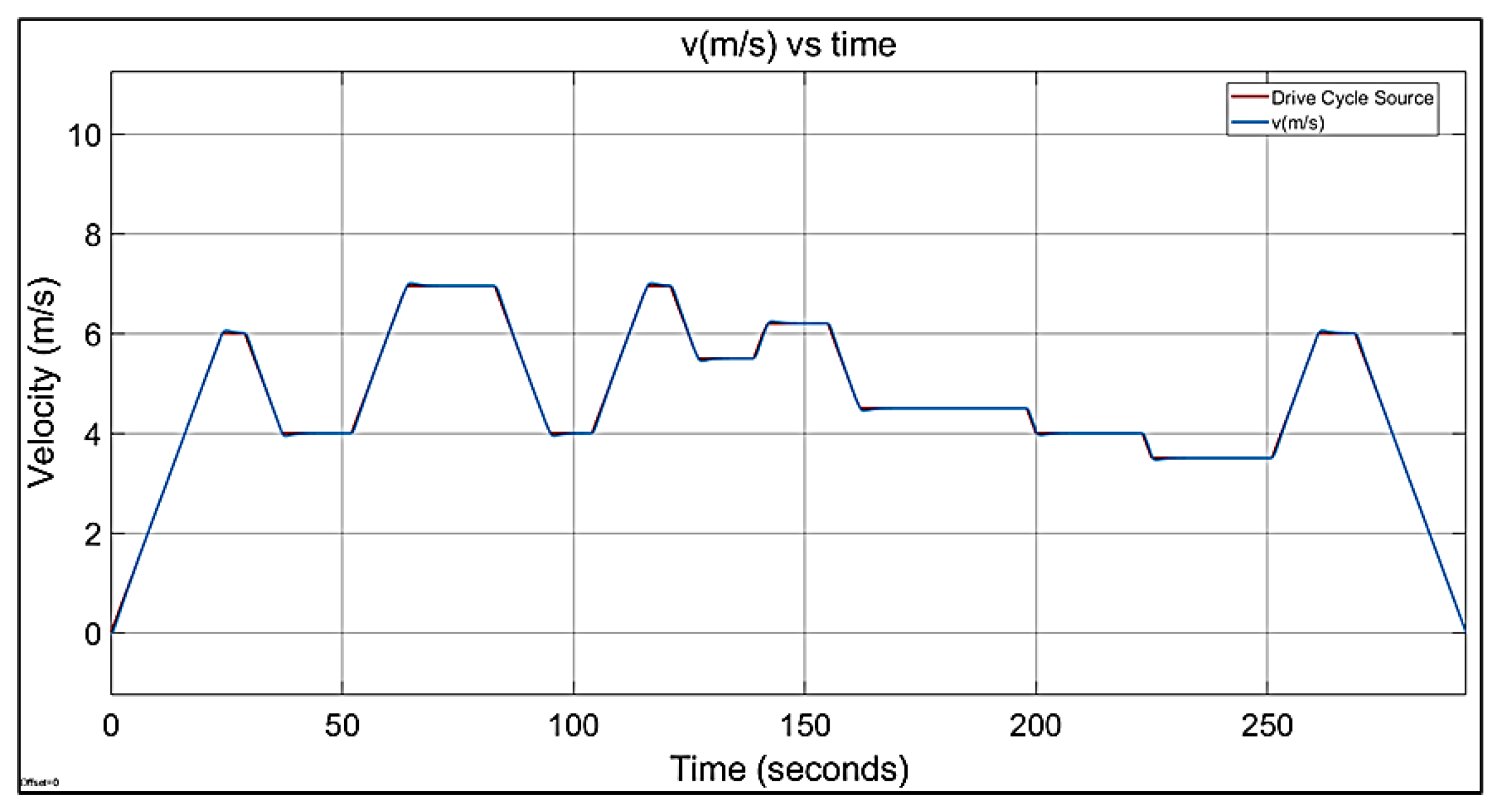

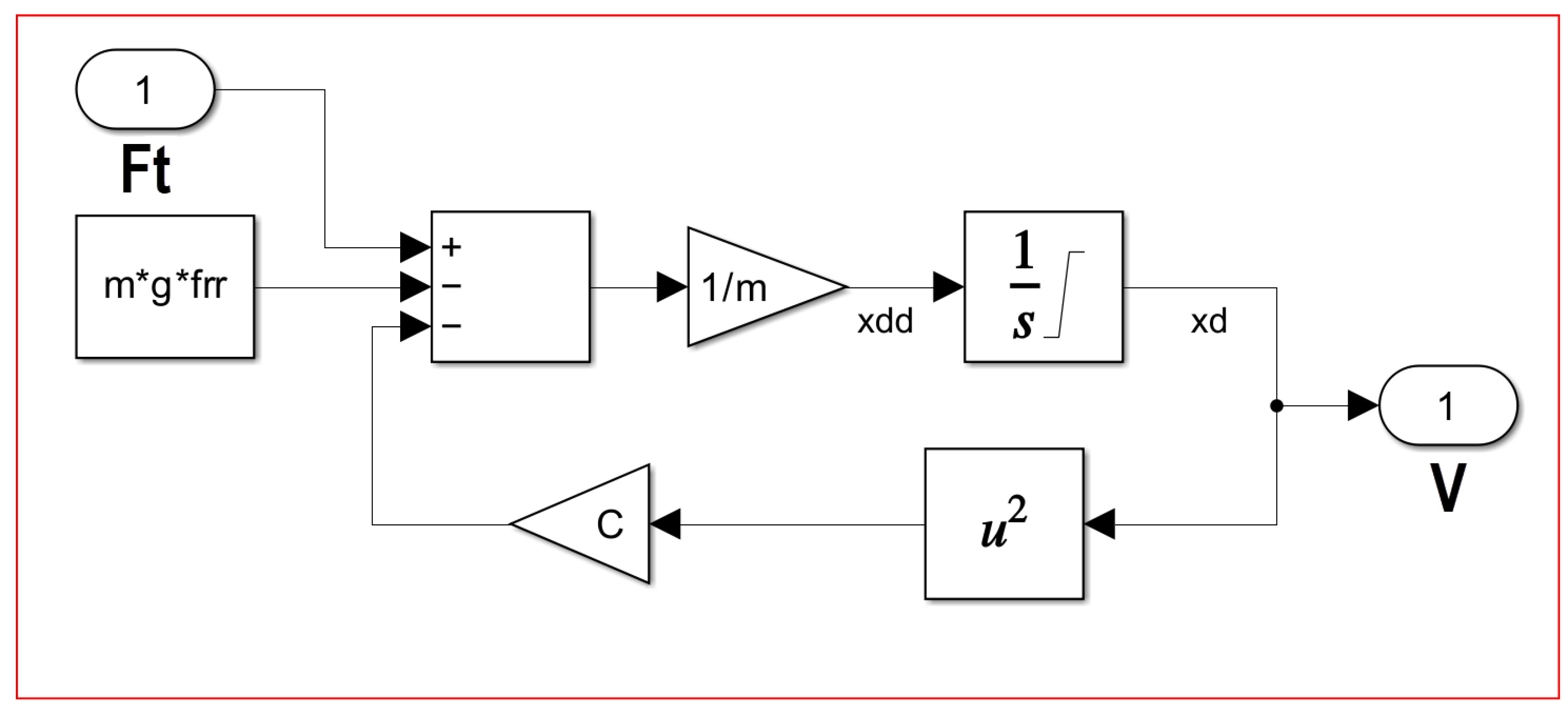

Simulation frameworks—especially those built in MATLAB/Simulink enable rapid development and performance validation of electric powertrain systems. (Wang et al., 2023) presented a multi-domain simulation model incorporating motor control, battery depletion, and dynamic load estimation. Studies such as (Tashen et al., 2024) show that simplified but well-calibrated simulation models can predict real-world performance to within 5% accuracy. (Khorrami, Krishnamurthy and Melkote, 2003) also highlight the value of including nonlinear motor behaviour and regenerative braking in control system simulations to improve response and energy management.

In summary, recent literature supports the use of BLDC motors, chain-driven single-motor configurations, and modular lithium-ion battery systems for Shell Eco-marathon vehicles and related applications. The emphasis on system integration, modular simulation, and component-level validation reflects a maturing field that balances academic rigor with real-world constraints. While more advanced technologies—such as axial flux motors, adaptive transmissions, or real-time thermal modelling show promise, they remain out of reach for many student-led teams due to budget and complexity. The current study builds on these findings, implementing a validated, cost-effective drivetrain architecture optimized for Shell Eco-marathon constraints. Its methodology grounded in recent research and supported by simulation offers a transferable framework for future developments in low-speed electric mobility, including last-mile delivery vehicles and urban micro-EVs.