1. Introduction

In today's era of rapid technological advancement, scientists are actively developing innovative energy solutions to address the threats of climate change and resource depletion [

1]. The acceleration of industrialization and the resulting global population growth have driven the development of urban areas, posing challenges to providing convenient and livable environments for people [

2]. As an indispensable part of modern society, transportation profoundly impacts economic efficiency and the sustainable development of society [

3]. Automobiles, airplanes, and trains not only offer fast and convenient transportation but have also become an essential part of modern society. However, the energy demands of these modes of transport have emerged as a major challenge today [

4]. The advent of mass vehicle production triggered an explosive growth in global transportation, accompanied by significant greenhouse gas emissions. This not only posed a serious threat to the Earth's ecological environment but also raised concerns about the depletion of limited energy resources [

5]. The energy demands of human society have continued to grow at an increasing rate. This situation has compelled countries around the world to reconsider their approaches to energy usage, strengthen the development and application of environmental technologies, and promote environmental protection and energy sustainability [

6]. The development of renewable energy, improvement of energy efficiency, and advancement of transportation technologies have become key components in achieving green mobility, while also reducing the pressure on the Earth's resources [

7]. With the rapid advancement of technology, energy management in transportation will continue to be a focal point of technological innovation and sustainable development [

8]. Future vehicle research will primarily focus on three major directions: battery electric vehicles (BEVs), hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) [

9]. Among these, BEVs are considered one of the primary global development objectives. In response to the energy crisis and environmental challenges, major automotive manufacturers are progressively adjusting their research and development directions, actively promoting innovations in new energy technologies. This shift not only demonstrates a commitment to sustainable development but also significantly reshapes the competitive landscape of the automotive industry [

10].

Recently, automotive manufacturers and governments worldwide have actively committed themselves to developing new energy vehicles. This has made the evolution from traditional internal combustion engine vehicles to HEVs a prominent trend. Major automakers have successfully developed hybrid vehicles with dual power outputs by combining internal combustion engines with electric drive motors [

11]. This system utilizes two or more power sources to drive the vehicle and can flexibly switch between them under various conditions, thereby achieving optimal performance across different driving scenarios [

12]. This technology not only extends the driving range of vehicles but also reduces energy consumption, bringing hybrid vehicles closer to the performance level of new energy vehicles. This development direction holds great promise for achieving energy-saving and carbon-reduction goals, offering a more forward-looking and environmentally friendly transportation solution to support sustainable development in the future [

13]. According to previous studies, the primary goals of optimizing energy and power systems are energy conservation and cost reduction. In this context, energy management strategies and power system design have become two critical considerations in related research. Among them, energy management strategies play a pivotal role in the optimization of energy and power systems [

14]. Through proper energy management, the system can more effectively utilize the conversion between different energy sources, thereby achieving more energy-efficient and environmentally friendly operation. The design of the electrical/power system directly affects the performance of the hybrid energy system. [

15]. Selecting appropriate power components, energy storage devices, and power transmission network structures ensures the coordinated operation of the entire system, achieving optimal performance [

16].

The power system of BEVs can be divided into two main configurations: (1) single-motor drive and (2) multi-motor drive. The single-motor configuration features a simplified structure and the use of high-performance electric motors, which makes it more challenging to balance vehicle performance with improved energy efficiency [

17]. Multi-motor drive systems can be further categorized into two types based on the number of motors: (1) four-motor distributed drive and (2) dual-motor coupled powertrain [

18]. The four-motor distributed drive system features individual motors assigned to each wheel, with each wheel delivering power independently through separate reducers or drive shafts, or alternatively, integrating motors directly into the wheels as hub motors [

19]. In contrast, the dual-motor coupled powertrain employs two motors to achieve multiple driving modes. Through an ingeniously designed mechanical coupling mechanism, the system efficiently allocates power between the two motors, significantly enhancing motor utilization. Compared to conventional single-motor setups, this configuration achieves superior overall performance [

20].

According to previous studies, optimization of a vehicle's energy management system primarily aims at reducing overall energy consumption and lowering costs to enhance overall efficiency and system performance. Energy management system strategies can mainly be categorized into two types: (1) rule-based (RB) strategies and (2) optimization-based strategies [

21]. Rule-based strategies can be further divided into two main types: (1) deterministic rules and (2) fuzzy logic rules [

22]. Deterministic rules involve predefined control strategies based on engineering experience to manage switching between different operational modes of the powertrain and distributing power among various energy sources [

23]. In contrast, fuzzy logic rules employ a set of predetermined yet flexible control strategies, allowing more adaptable handling of uncertainties and complexities within the system. Decisions and controls are executed through fuzzy logic, enabling dynamic adjustments to operational modes and power allocation between different energy sources [

24]. Optimization-based strategies can be mainly classified into two categories: (1) real-time optimization and (2) global optimization [

25]. Real-time optimization involves dynamically allocating power between the engine and electric motor based on current power demands, ensuring the minimum equivalent consumption and minimal power losses at each moment. An example of this approach is the global grid search (GGS) [

26]. Global optimization utilizes optimal control principles to improve fuel consumption and power loss across an entire driving cycle, dynamically optimizing power allocation among energy sources to achieve overall optimal vehicle performance. Examples include methods such as dynamic programming (DP) [

27] and genetic algorithm (GA) [

28]. To thoroughly investigate vehicle energy efficiency, this research primarily focuses on two main areas: the powertrain system and the control strategy. Regarding powertrain design, recent commercially available vehicles exhibit highly similar system architectures, with multi-power-source configurations emerging as the mainstream design. In terms of control strategies, theory-based controls have already achieved considerable success in various engineering applications. Currently, bio-inspired heuristic algorithms, such as the whale optimization algorithm (WOA), are gradually becoming a popular trend in the field of optimization methods [

29].The WOA compared with other heuristic algorithms, demonstrates superior problem-solving capabilities and computational efficiency. It is feasible for energy management involving multiple control variables, thereby enhancing the performance of hybrid power systems and showcasing its significant potential in vehicle control applications [

30].

To effectively validate the practical operation of the energy management system, a HIL system is utilized to perform real-time computation, bridging the gap between the simulation phase and actual vehicle implementation. This approach helps identify data errors and enhances system fault tolerance. In this research, the dual-motor drive simulation platform is divided into two parts: the vehicle control unit (VCU) and the vehicle platform. An Arduino DUE microcontroller and a Ti C2000 microcontroller are employed to construct a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) platform, enabling analog and digital input/output signal conversions through signal processing. The FTP-75 (Federal Test Procedure 75) driving cycle is used as a basis for analyzing the performance characteristics and inter-system response relationships, including torque, rotational speed, optimization management, and overall vehicle energy efficiency.

3. Energy Management Strategy

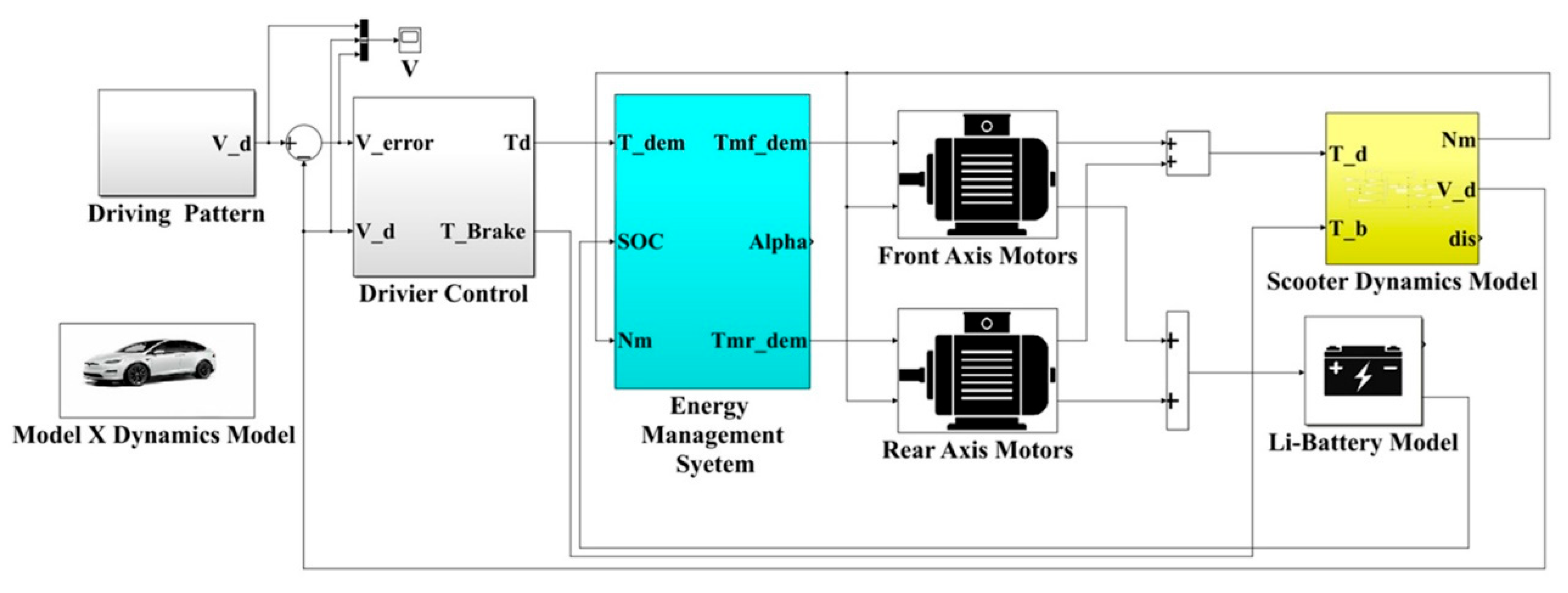

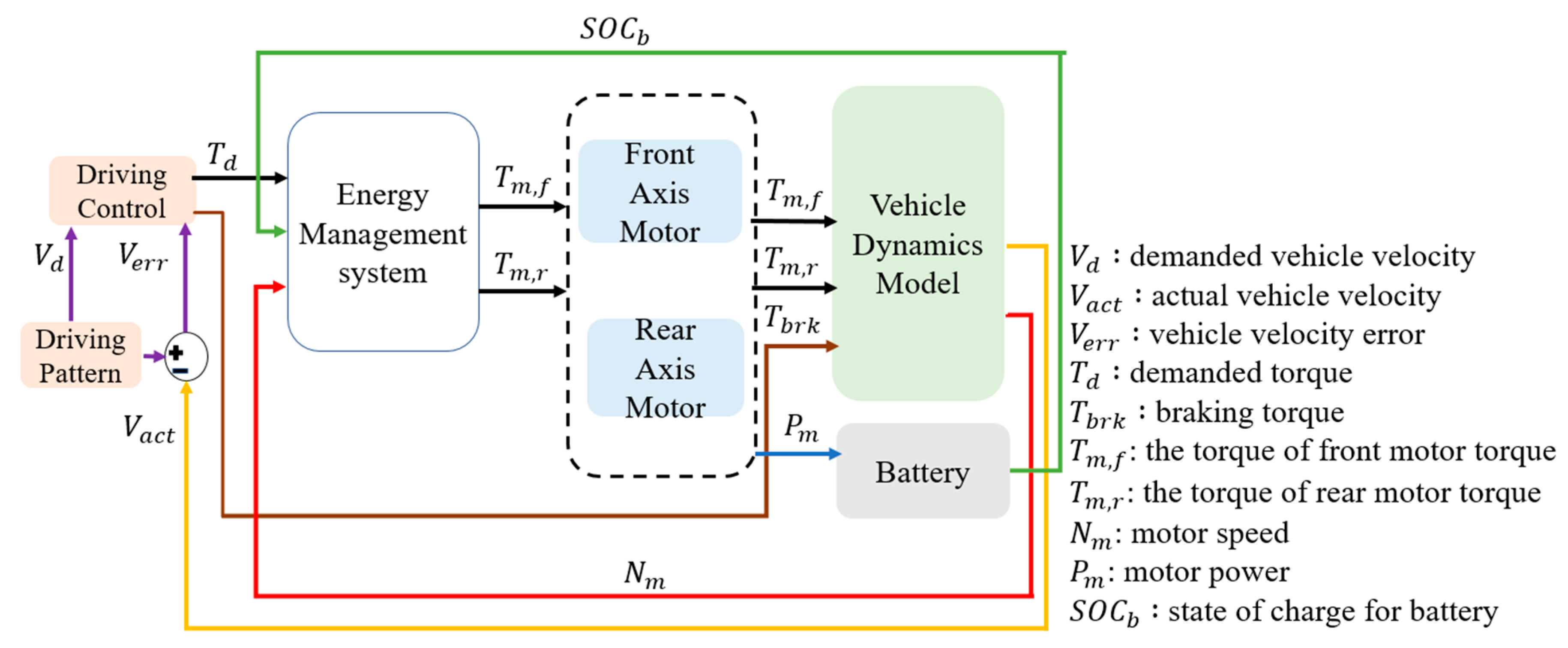

This study adopts an energy management strategy to calculate the optimal motor efficiency range and determine the best power distribution ratio. Simulation verification is conducted using the FTP-75 driving cycle, and the control architecture of the energy management system is illustrated in

Figure 8. First, the driving cycle model provides the target vehicle velocity for simulation. The actual vehicle velocity is then calculated through the vehicle dynamics model. The vehicle velocity error, obtained by subtracting the actual velocity from the demanded vehicle velocity, is used as the input to the PI controller. The PI controller outputs the demanded torque, which is sent to the energy management model to determine the power distribution between the dual drive motors. Meanwhile, the braking torque is used to command the braking force and is sent to the vehicle dynamics model to perform vehicle braking. The energy management model uses the actual motor speed from the vehicle dynamics model to calculate the optimal torque distribution, sending control commands to the front and rear axis motors for execution. Finally, the motor outputs are integrated into the vehicle dynamics model to compute the actual vehicle velocity.

3.1. Rule-based Control Strategy

Rule-based control (RBC) is implemented using the Stateflow model in MATLAB/Simulink® to develop the energy management strategy. Based on different driving demands, corresponding power distribution modes are established, as detailed in

Table 3. When the input signals meet the predefined state conditions, the system outputs the corresponding power distribution results. These rules are primarily formulated based on the researcher’s engineering experience and the operational efficiency of individual components, enabling control over mode switching under various driving conditions [

37]. In this study, the RBC strategy defines four operating modes, as shown in

Table 3. The mode determination is based on the demanded vehicle velocity, demanded torque, and battery SOC. The modes are defined as follows:

Ø System Ready Mode: When the driver’s demanded torque is 0 Nm, the system enters the ready mode, and the commanded motor torque output is also set to 0 Nm.

Ø Low Load Mode: When the demanded torque is greater than or equal to 0.1 Nm, the vehicle enters the low load mode. In this mode, the demanded torque is shared between the front and rear axis motors with a distribution ratio of 3:7.

Ø High Load Mode: When the actual vehicle velocity exceeds 50 km/h, the system switches to high load mode. In this mode, the demanded torque is allocated to the rear axis motor, which primarily propels the vehicle.

Ø Safety Mode: When the demanded torque is 0 Nm and the battery SOC reaches 0, the system enters the safety mode.

Ø These control rules ensure appropriate power allocation and system response under various operating conditions.

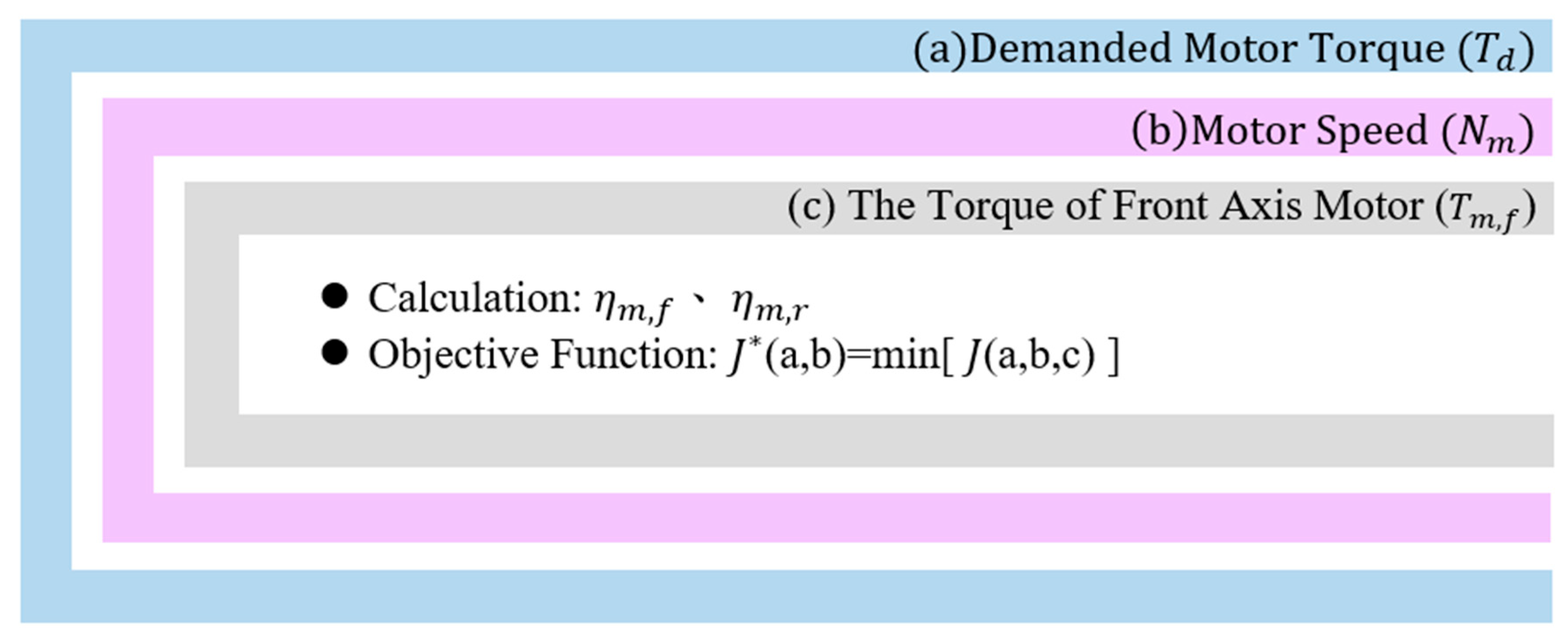

3.2. Global Grid Search Method

In the computational process, system model parameters such as total demanded power, motor speed, and physical constraints are established to construct an optimized power distribution model for control system parameter analysis. This approach effectively simplifies the control model to meet the real-time computing requirements of the HIL system. To obtain the optimal control model parameters, a GGS method is used to find the best parameter solution. By first inputting the necessary parameters such as the demanded torque, drive motor speed and performing discretization, an objective function is defined to identify the optimal power distribution algorithm. The goal is to minimize power consumption, and the minimum value is determined as expressed in Equation (9):

Where

is the efficiency of the front axis motor;

is the efficiency of the rear axis motor;

is the input power the front axis motor;

is the input power the rear axis motor;

is the optimal cost function;

is penalty value. The output power of the front and rear axle motors are calculated as shown in Equations (10) and (11):

By substituting Equations (10) and (11), the result is shown in Equation (12):

The

represents the penalty value, when the conditions of a grid search exceed physical constraints, a large penalty value is assigned:

In studies related to the front and rear motor power ratio, it has been observed that when electric vehicles require more acceleration and high-speed operation, the importance of the front-axle motor may increase [38, 39]. The GGS method selects the optimal power distribution by minimizing power consumption based on the vehicle’s real-time operating status and control variables, while also taking vehicle performance requirements into account. This enables the vehicle to achieve the most efficient energy management at different operating points, thereby improving overall energy utilization. The strategy process is as follows:

Ø The GGS search method involves three nested loops used for globally searching discretized values of demanded torque and motor speed.

Ø The program uses "if-then-else" conditional statements to evaluate various possible operating modes and then calculates parameters such as the efficiency and torque of the front and rear axis motors.

Ø Based on the concept of minimum power consumption, the power consumption under different conditions is calculated. For a fixed motor speed and demanded torque, the minimum power consumption under different dual-motor torque distributions can be used to determine the optimal power distribution ratio.

Table 4 lists the relevant parameters for the front and rear axle motors. Based on the design of the optimal objective function, the power distribution ratios are defined according to Equations (14) and (15):

Where is the power distribution ratio 0~1).

Under the same minimum motor power consumption strategy, the optimal motor power consumption is identified using the optimal power distribution loop shown in

Figure 9. The discretized variables include the required torque, motor speed, and the front rear axle motor power distribution ratio α, which are used to perform a global search. By calculating the electric power consumption of the front and rear axis motors under different variable conditions, an optimal two-dimensional power distribution map can be derived. The calculation is expressed in Equation (16):

3.3. Whale Optimization Algorithm

In this study, a heuristic optimization algorithm inspired by the foraging behavior of whales, is utilized. WOA simulates the process by which whales search for food perceiving information such as sound and scent in their surroundings to determine the direction and distance of prey, then taking corresponding actions. The algorithm mimics these behaviors to search for optimal solutions [

40]. One of the most remarkable features of whales is their unique hunting method known as the bubble-net feeding method. This feeding behavior typically occurs near the ocean surface, where whales create bubbles to trap prey. They form these bubble nets along circular or figure-eight-shaped paths. During the upward spiral, a whale dives to a depth of approximately 12 meters and begins creating spiral-shaped bubbles around the prey, eventually swimming upward to capture it. The dual-spiral strategy involved in this behavior includes three distinct stages: spiral ascent, surface tail slapping, and the capture cycle. Bubble-net feeding is a unique and specialized behavior among whales, and the WOA is modeled after this spiral bubble-net hunting strategy to achieve optimization objectives [

41]. The strategy process is as follows:

Ø Initialization: In this stage, initial parameters are set and the initial positions of the whales are generated. To prevent the algorithm from falling into local optima, the whales are uniformly distributed throughout the search space. The initial positions are defined by Equation (17):

Where is the lower bound of the control variable being searched; is the upper bound of the control variable being searched; is the dimensional size of the control variable.

2. Surround prey: The whale identifies the position of the prey and encircles it. In the WOA, it is assumed that the current best solution is the target prey or is close to the optimal solution [

42]. Once the best search formula is defined, other search agents will attempt to update their positions toward the best one. This behavior can be expressed by the following equation:

Where

is the current number of iterations;

is the step coefficient;

is the weighting coefficient;

is the spatial vector between the whale and the current best prey position;

is the position of the current best solution;

is the current position. Whenever a better solution appears during each iteration, an update is required.

,

and

are calculated as follows:

Where decreases linearly from 2 to 0 during the iteration process; the current iteration number; is the maximum number of iterations; is the random vector within the range [0, 1].

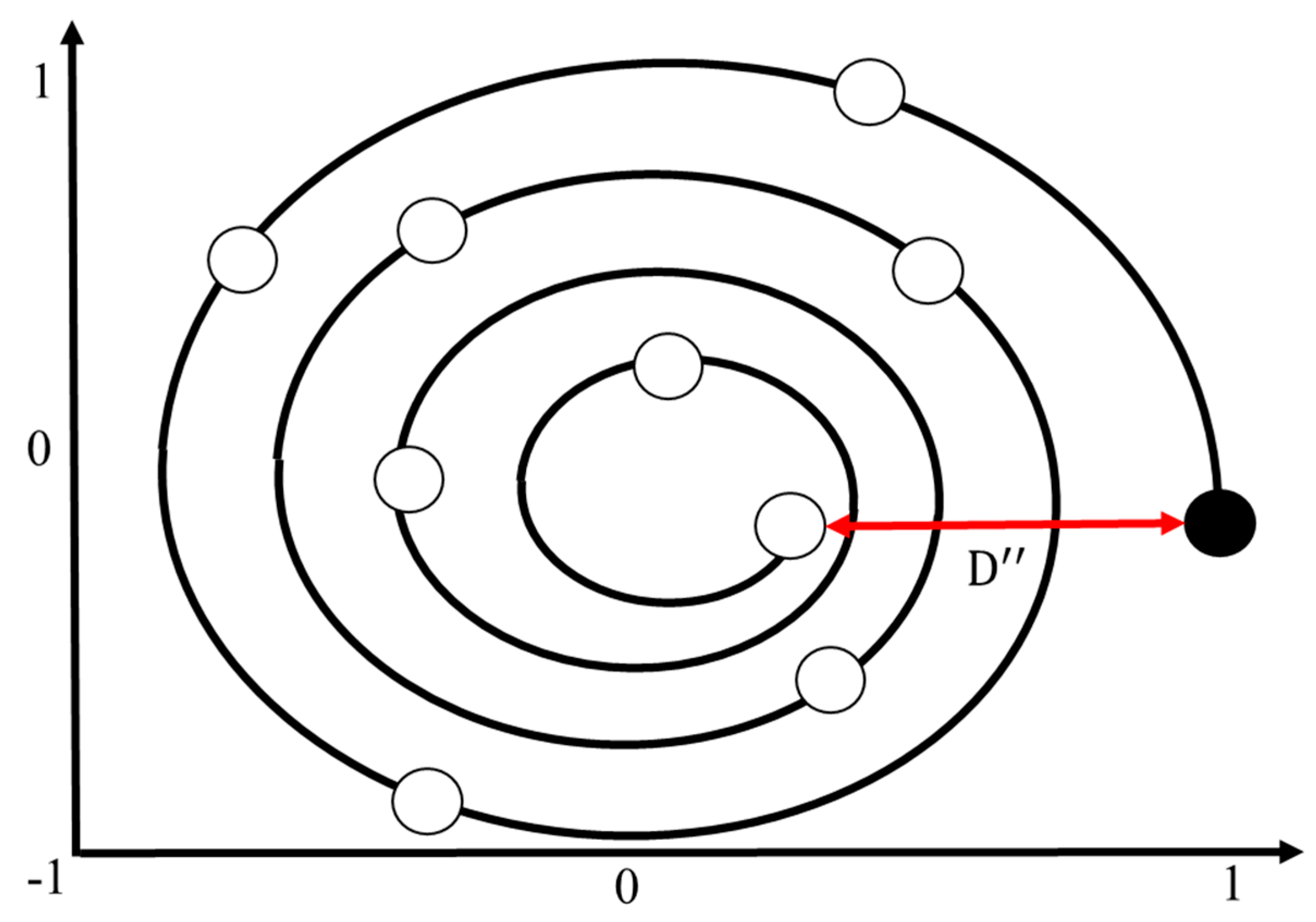

3. Bubble-net attacking method: There are two methods for modeling the whale's bubble-net feeding behavior: (1) the shrinking surround mechanism, and (2) the spiral position update [

43]. As shown in Equation (20), this behavior is achieved by gradually decreasing the value of

. It is important to note that the range of

also decreases along with a, where

is a random value within the interval [−

,

]. By setting

as a random number between −1 and 1, the new position of a search agent can lie anywhere between its original location and the current best position. When

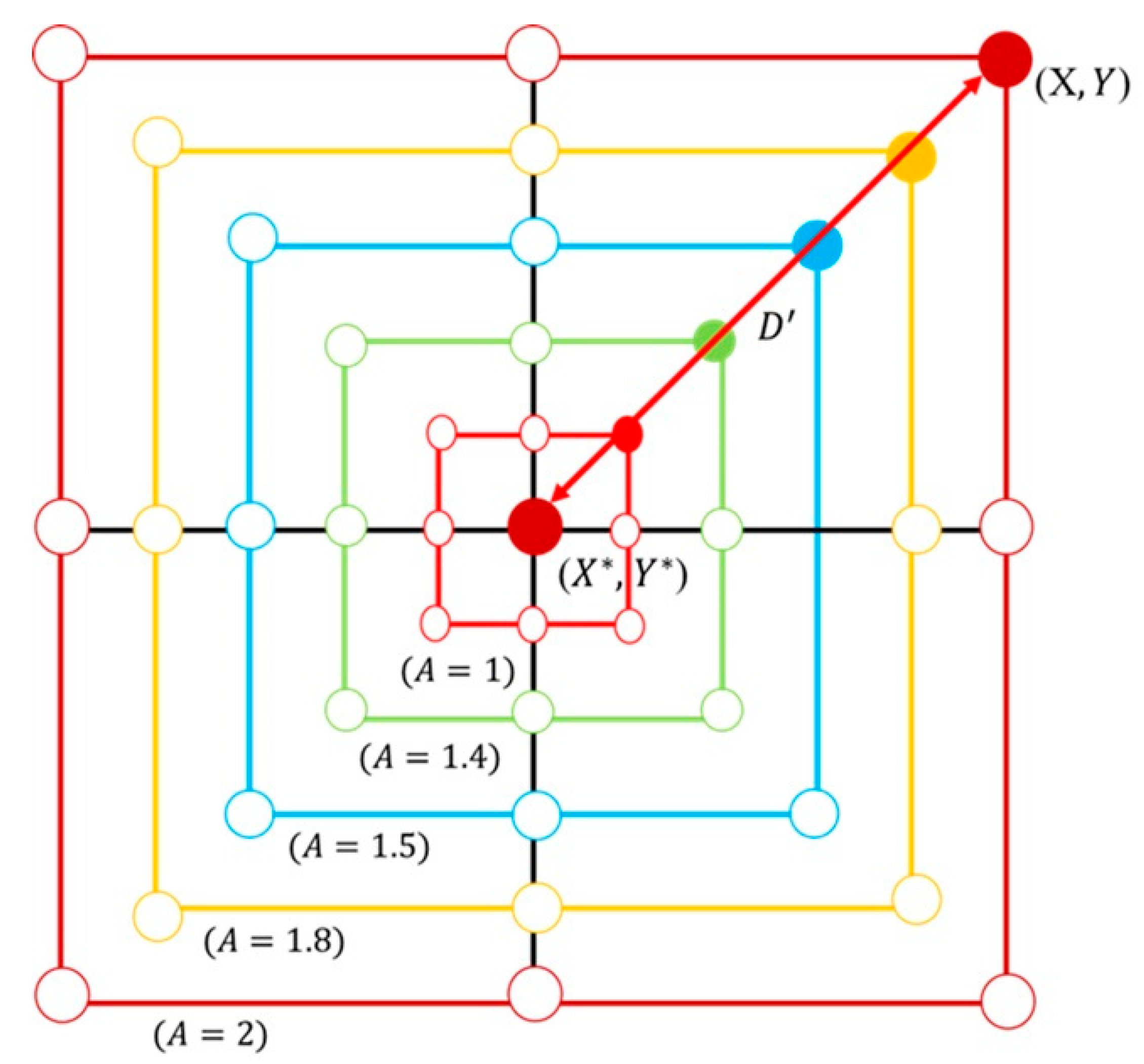

, it illustrates all possible locations in 2D space between (X, Y) and (X* ,Y*), which essentially simulates the behavior of surround and hunting prey. Whales generate spiral-shaped bubble nets through their blowholes to trap prey, making it difficult for the prey to escape. They then move along this spiral bubble path to complete the hunt [

44]. Based on the position of the best-identified prey, the whale generates a spiral bubble pattern and updates its position accordingly using Equation (22), as shown in

Figure 10. The spiral position update is expressed by Equation (23):

Where is the spatial vector between the whale and the current best prey position; is a constant that defines the shape of the spiral bubble-net, and it is set to 1 in this study; is a random number between [−1, 1].

4. Search for prey: In addition to using the bubble-net method, whales also exhibit random prey-searching behavior during foraging, as illustrated in

Figure 11. This behavior is based on a variable

vector, where whales perform random searches relative to each other’s positions. In this method, when

is greater than 1 or less than -1, it drives the search to move away from the current location. Unlike the bubble-net method, this search mechanism does not rely on the best solution found so far, but rather updates positions based on randomly selected search agents [

45]. This mechanism involves an

vector magnitude greater than 1, as represented in Equations (24) and (25):

Where is the current random position of the whale population; is the position vector between the whale and a randomly selected prey.

5. Record the current highest profit until the search stopping condition is met: WOA continuously updates the optimal solution through iterative searching (i.e., minimizing the objective function defined in this study). Once the search stopping condition is met, the algorithm outputs the optimal solution; otherwise, it returns to steps (2), (3), and (4) to continue the computation until the stopping condition is satisfied or the computation is complete [

46].

Figure 11.

Search diagram of the whale prey.

Figure 11.

Search diagram of the whale prey.

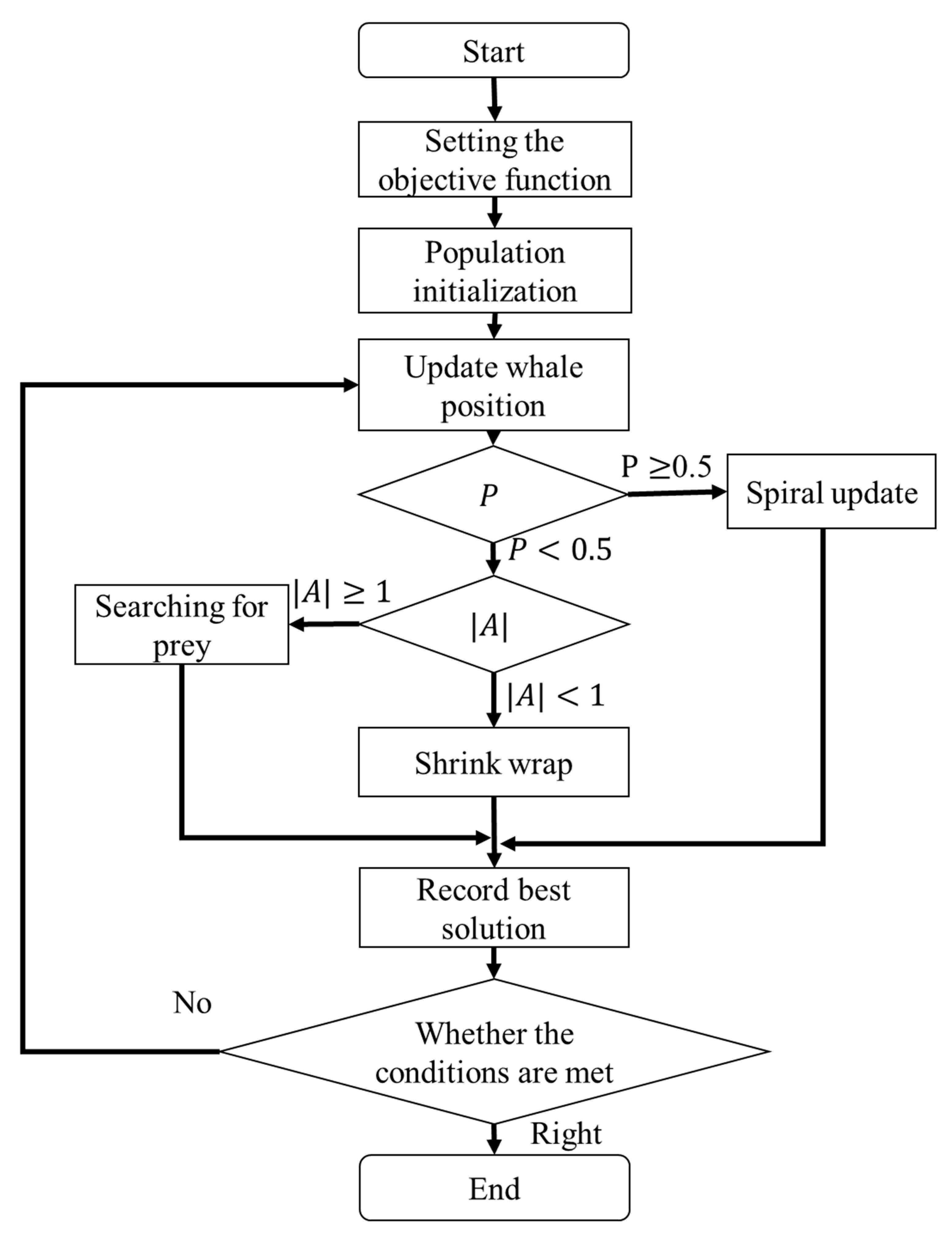

This study introduces two optimization methods for control strategies. Although the core computations differ in terms of the mathematical equations used during their respective search processes, both aim to optimize the same objective function, and the control variables used are identical to those in the GGS approach, as referenced in the GGS power distribution ratio formula. In the WOA, key control parameters typically include population size and the number of iterations. These parameters significantly affect the algorithm’s performance and convergence speed. In general, their values are adjusted according to the characteristics and requirements of the problem being addressed. In this study, vehicle energy efficiency simulations are conducted using MATLAB/Simulink®, with a sampling time of 0.01 s. The main focus is to compare the impact of different control strategies on vehicle energy efficiency rather than on the optimization of algorithm parameters themselves. Based on simulation results, using a larger population size yields better outcomes. The parameter settings are shown in

Table 5.

In this study, the defined parameters are applied to the WOA for computation. The process begins with Step 1, which involves initializing the whale population, calculating fitness, updating whale positions, handling boundary conditions, and generating initial positions. In Step 2, the algorithm checks whether the maximum number of iterations has been reached. If not, it proceeds to Step 3, where a probability-based decision is made. Based on the value of

, the algorithm selects a behavior mode: if

0.5, the spiral position update is performed; if

0.5, it proceeds to Step 4. In Step 4, the algorithm determines the step coefficient based on the relative distance between the whale and the prey using the value of

. If

1, the whale performs a search for prey; if

1, the whale engages in shrinking surround behavior. Finally, the best solution is selected based on the optimal fitness value, and the process returns to Step 2 to continue the iterations until the stopping condition is met. The WOA flow is illustrated in

Figure 12.

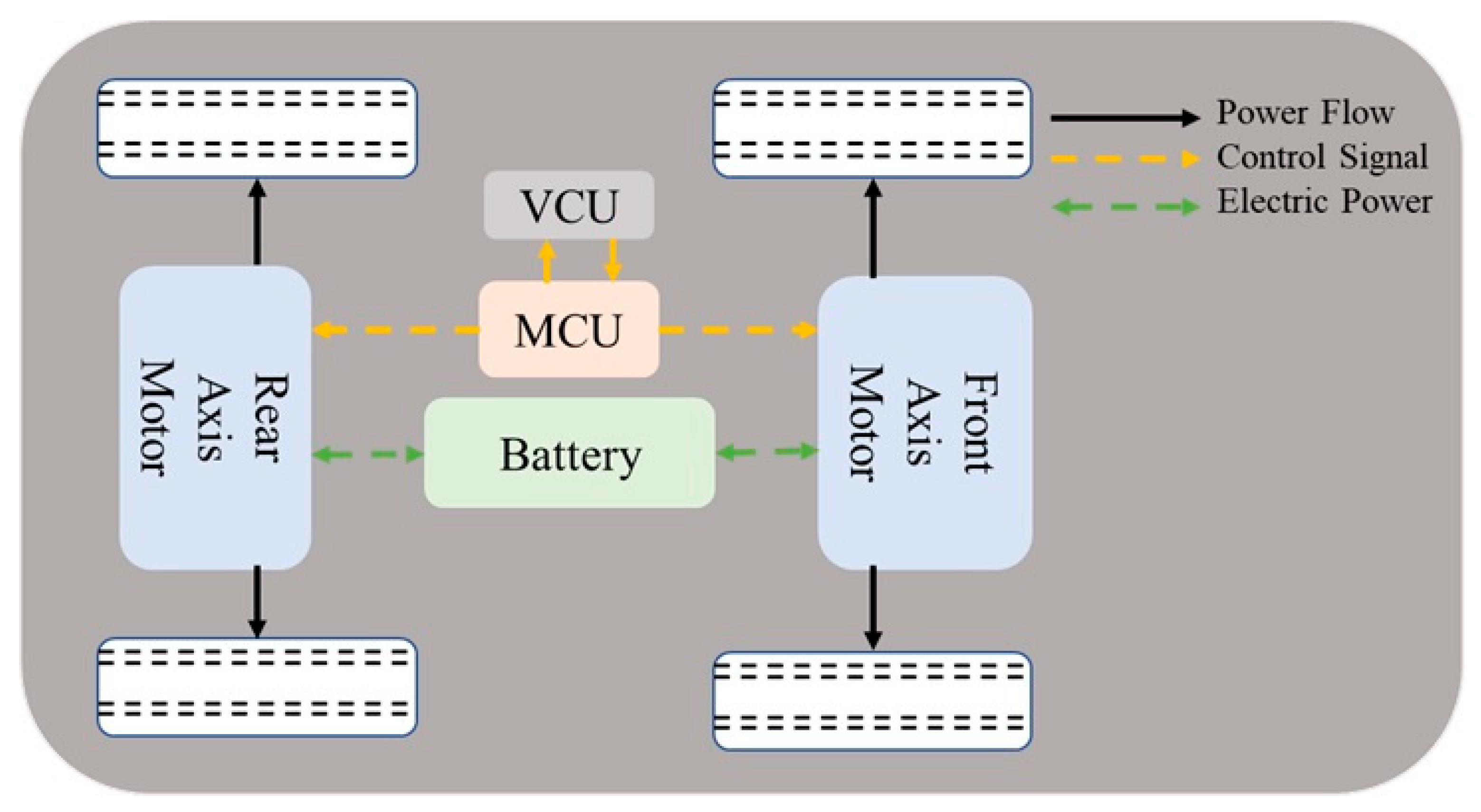

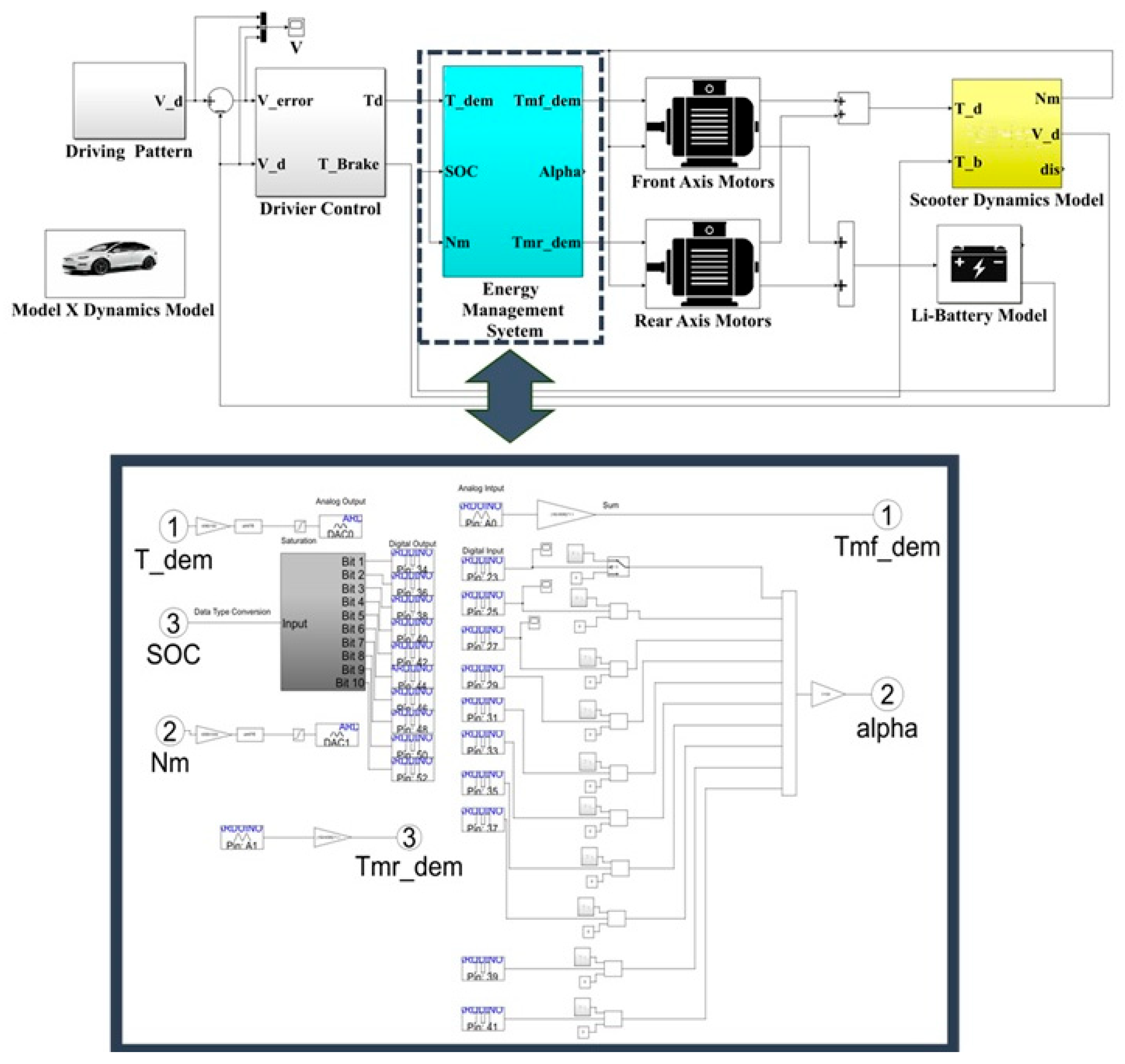

Figure 1.

System architecture of the dual-motor drive system.

Figure 1.

System architecture of the dual-motor drive system.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the vehicle simulation platform software.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the vehicle simulation platform software.

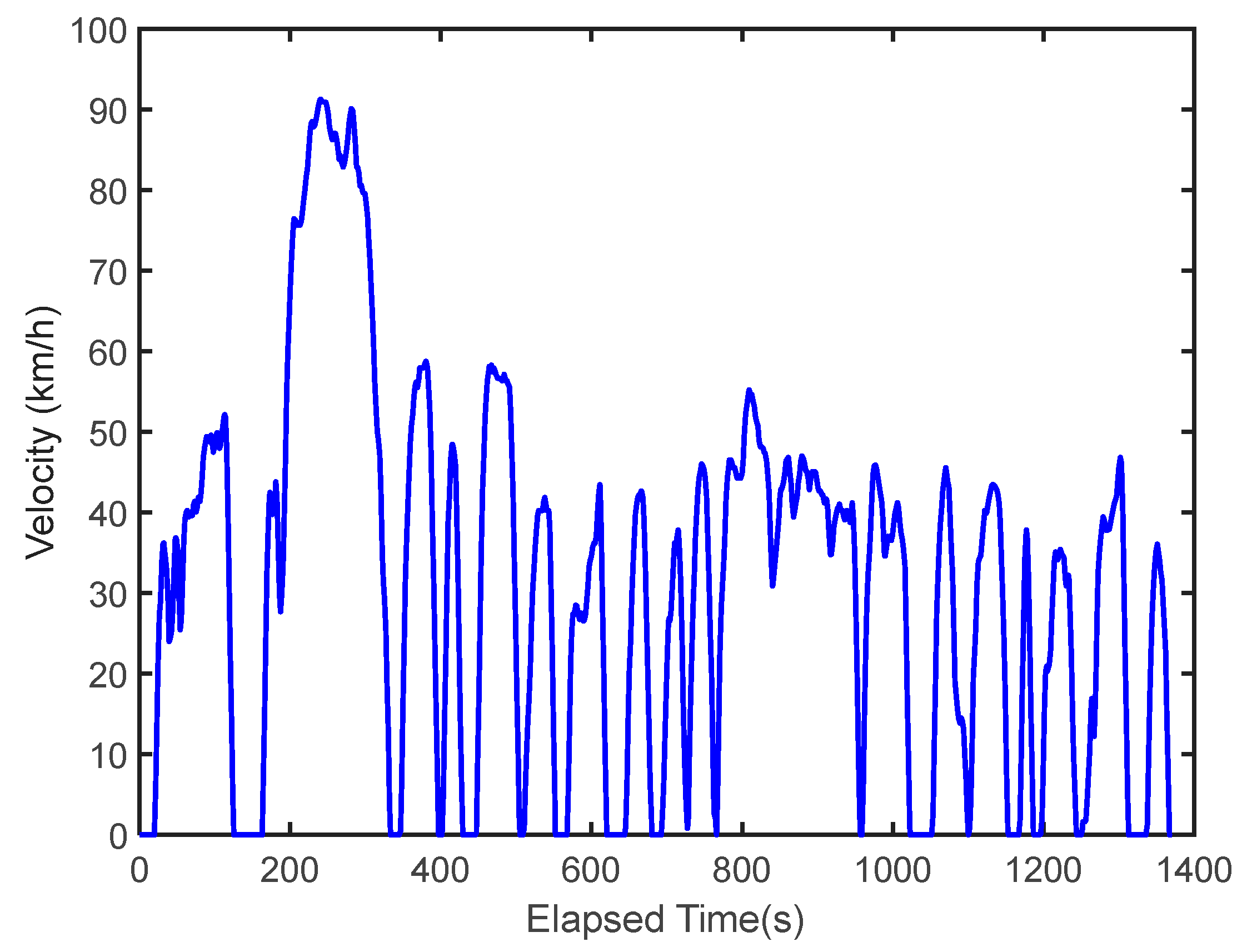

Figure 3.

FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 3.

FTP-75 driving cycle.

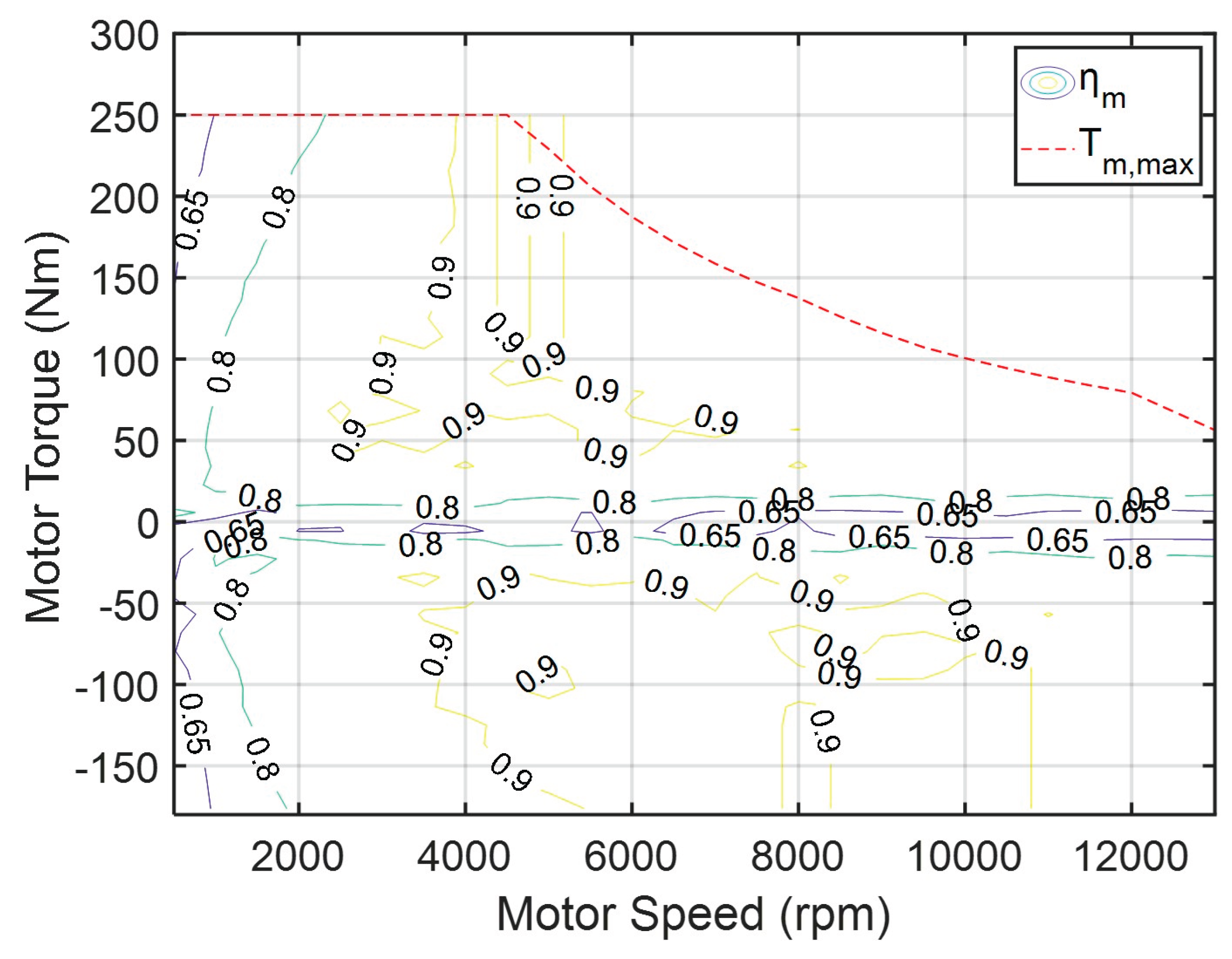

Figure 4.

Efficiency curve of the drive motor.

Figure 4.

Efficiency curve of the drive motor.

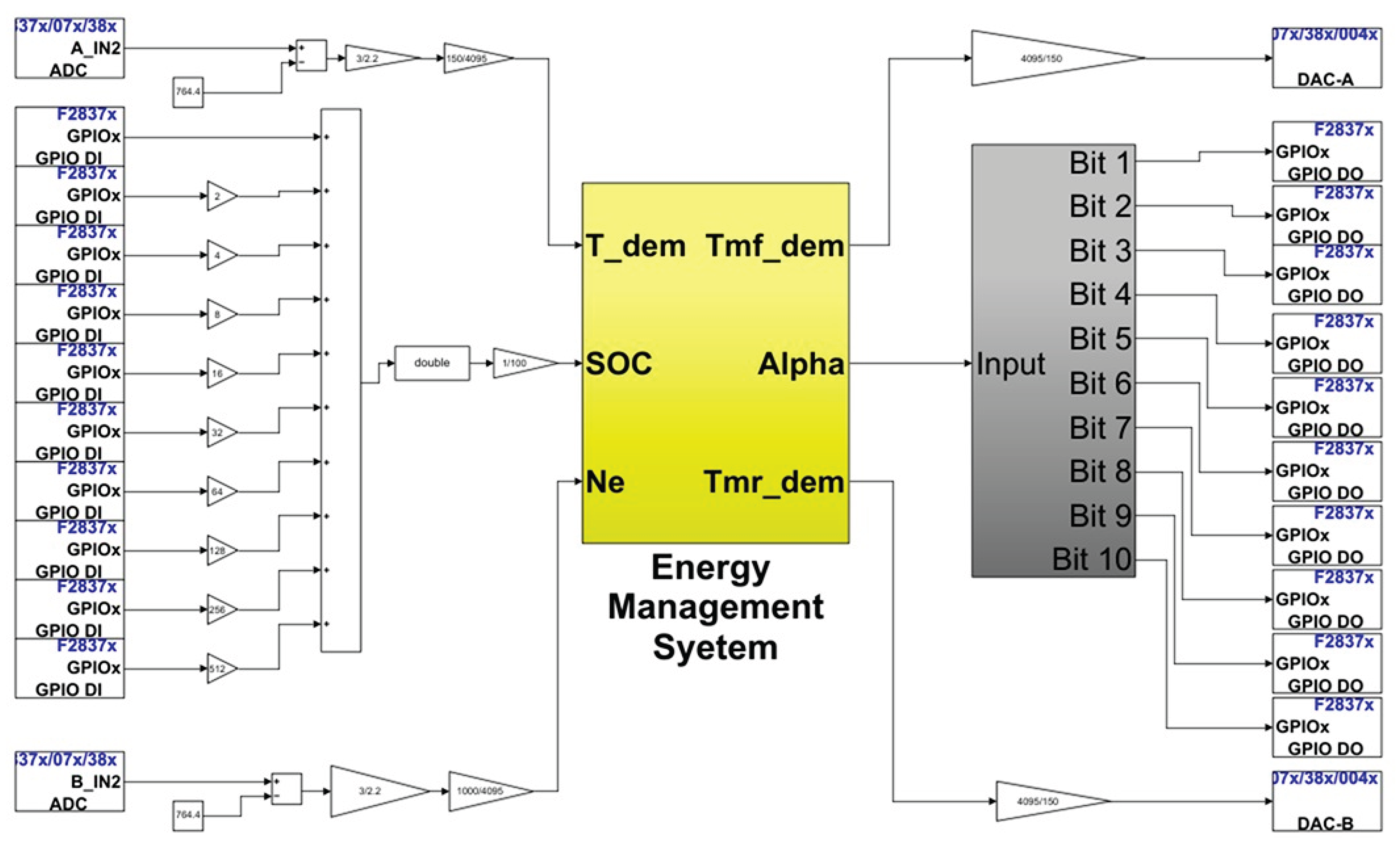

Figure 5.

Real-time model software of the VCU.

Figure 5.

Real-time model software of the VCU.

Figure 6.

Real-time model software of the vehicle platform.

Figure 6.

Real-time model software of the vehicle platform.

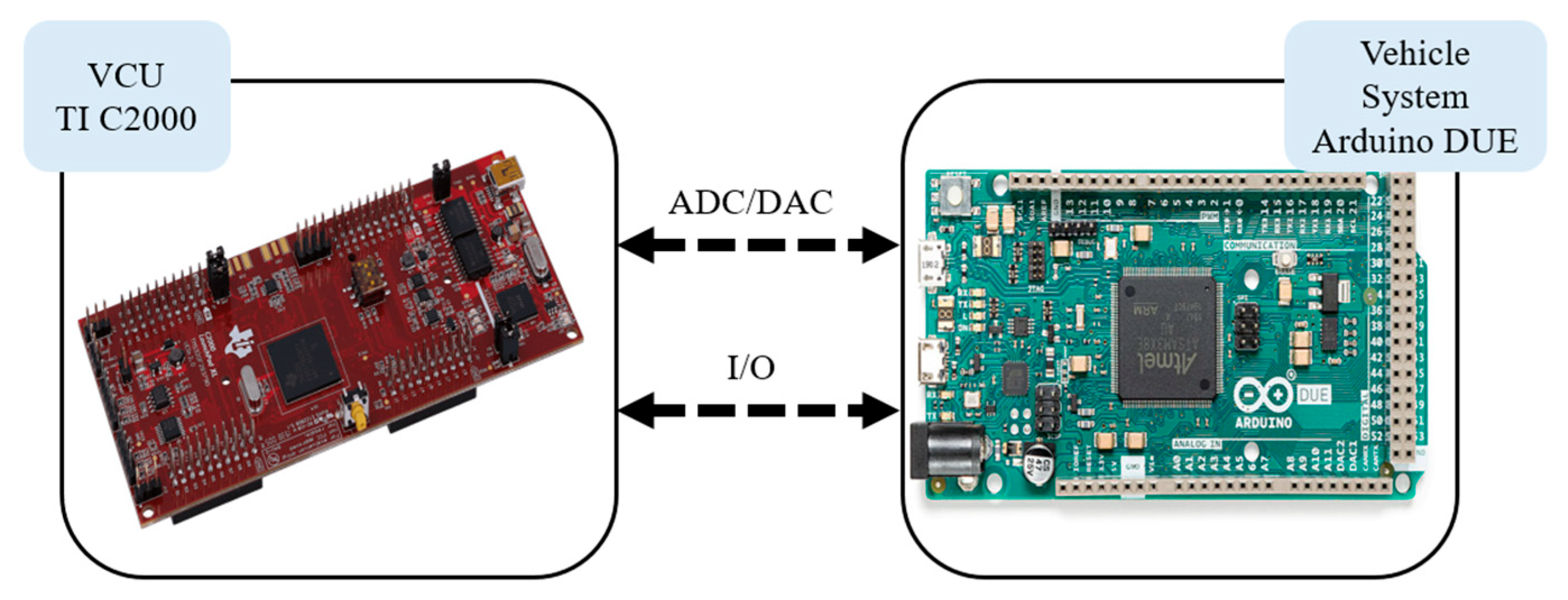

Figure 7.

System architecture of the HIL using the Arduino DUE and Ti C2000.

Figure 7.

System architecture of the HIL using the Arduino DUE and Ti C2000.

Figure 8.

Control architecture of the energy management system.

Figure 8.

Control architecture of the energy management system.

Figure 9.

Optimal power distribution loop for the front and rear axis motors.

Figure 9.

Optimal power distribution loop for the front and rear axis motors.

Figure 10.

Update diagram of the spiral position.

Figure 10.

Update diagram of the spiral position.

Figure 12.

Flowchart of the WOA.

Figure 12.

Flowchart of the WOA.

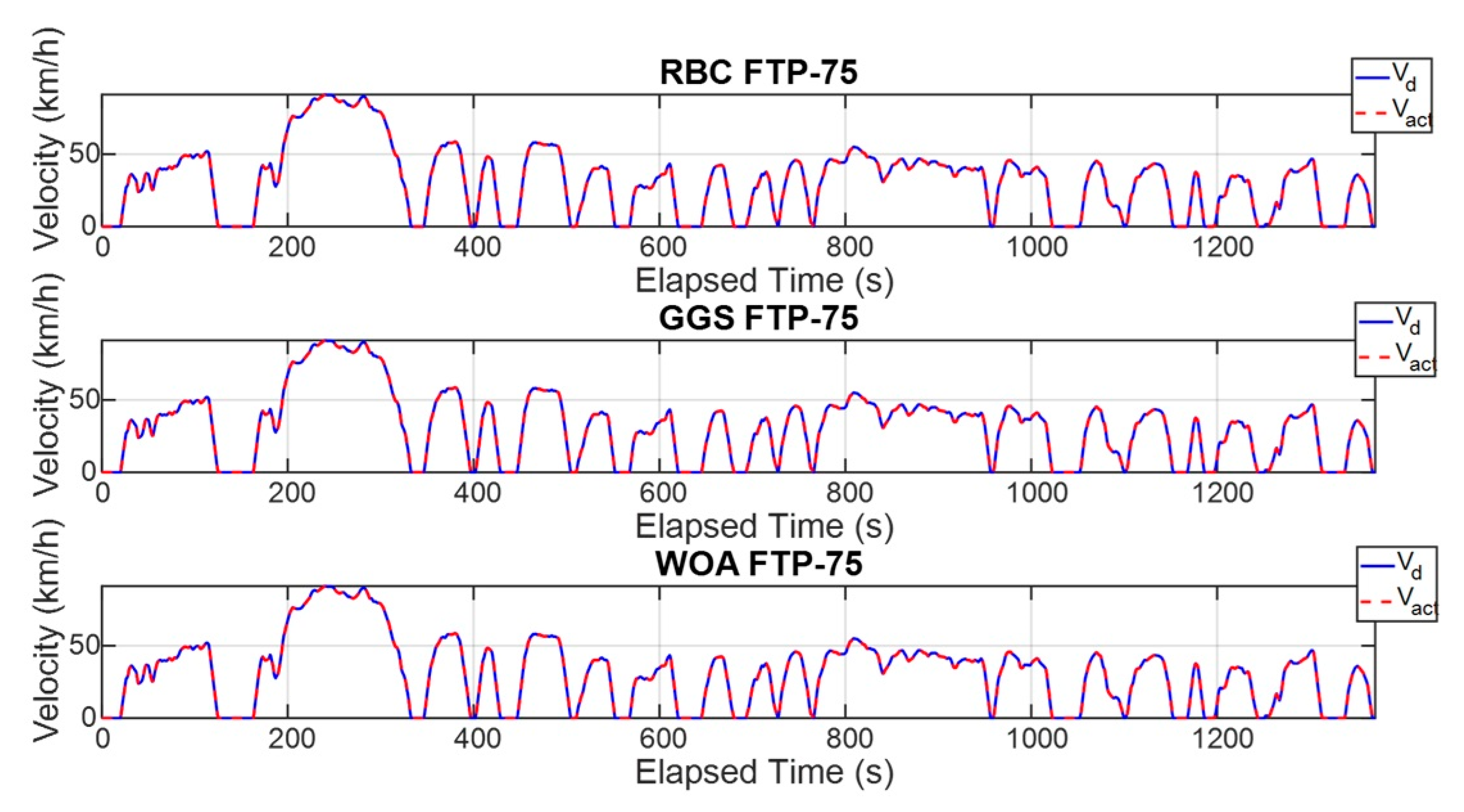

Figure 13.

Vehicle velocity for single FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 13.

Vehicle velocity for single FTP-75 driving cycle.

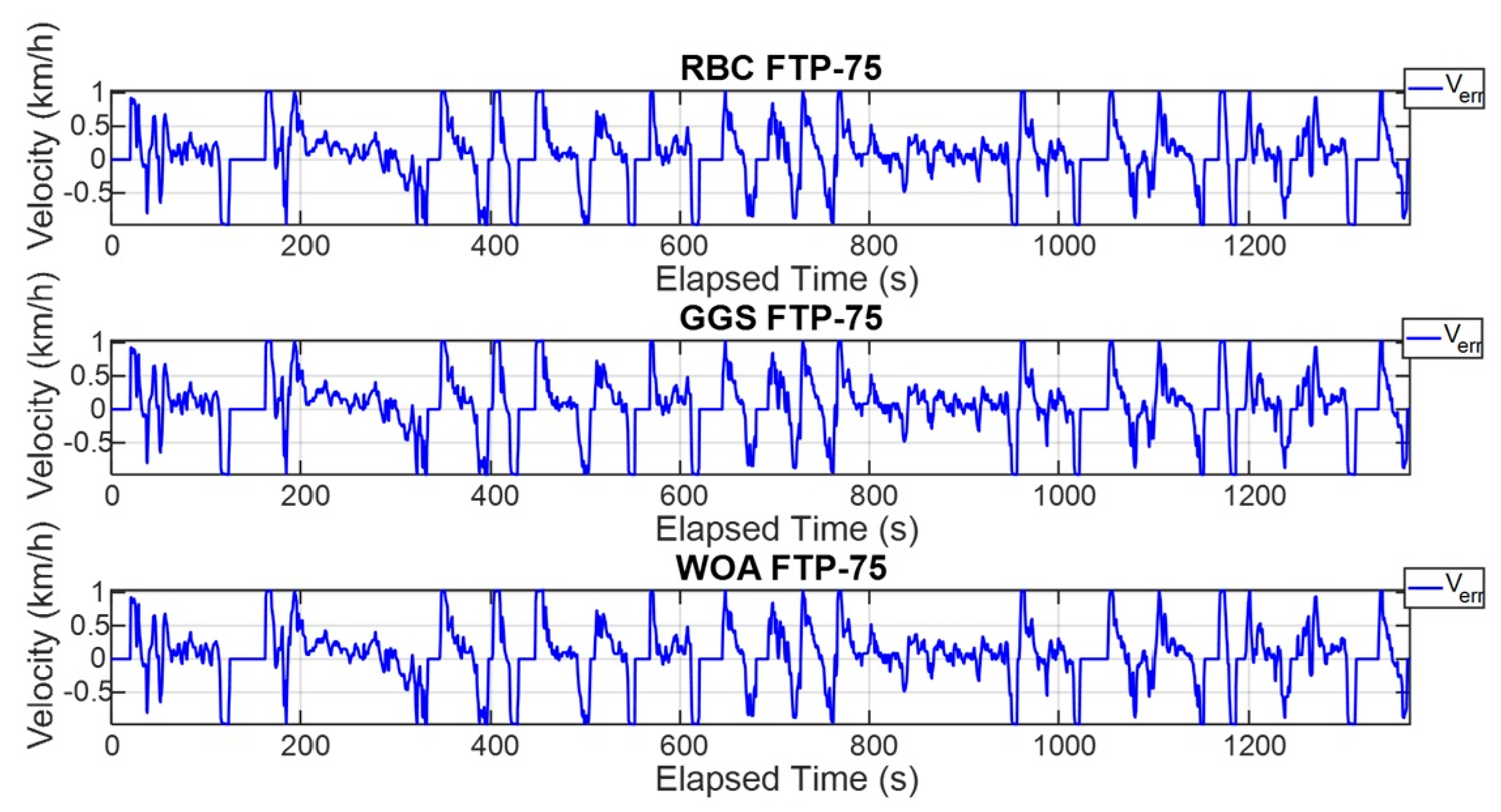

Figure 14.

Vehicle velocity error for single FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 14.

Vehicle velocity error for single FTP-75 driving cycle.

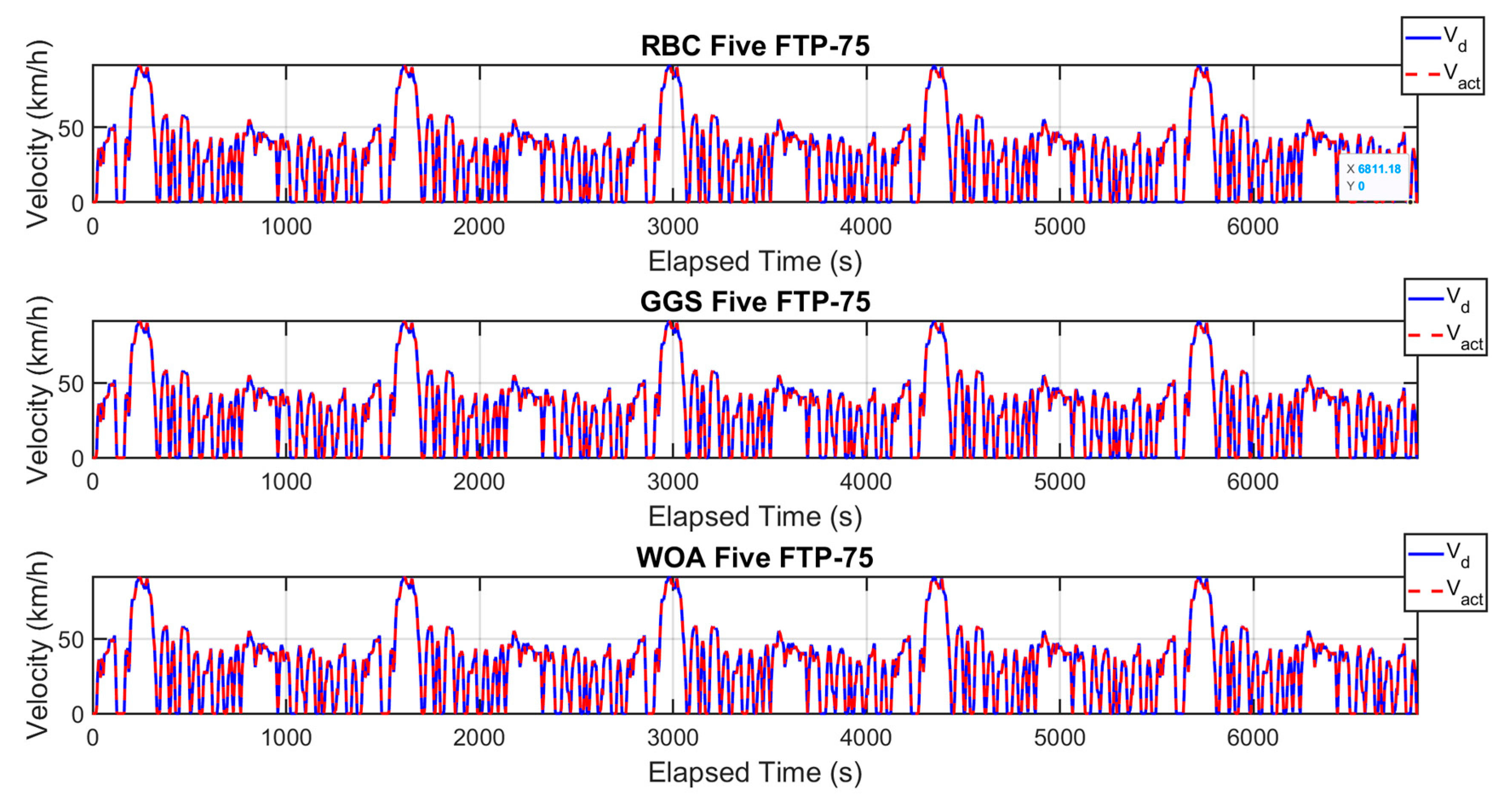

Figure 15.

Vehicle velocity for five FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 15.

Vehicle velocity for five FTP-75 driving cycle.

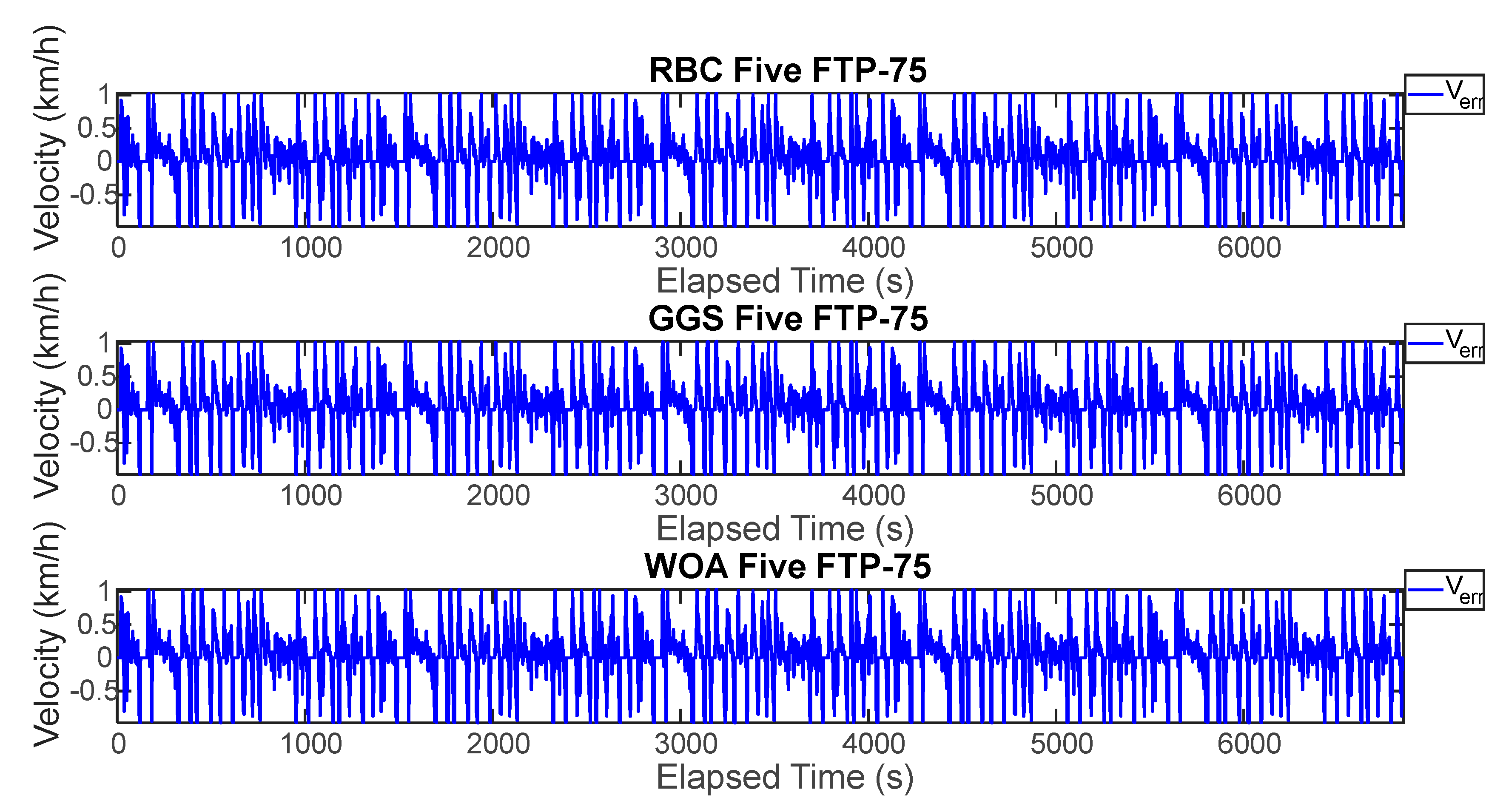

Figure 16.

Vehicle velocity error for five FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 16.

Vehicle velocity error for five FTP-75 driving cycle.

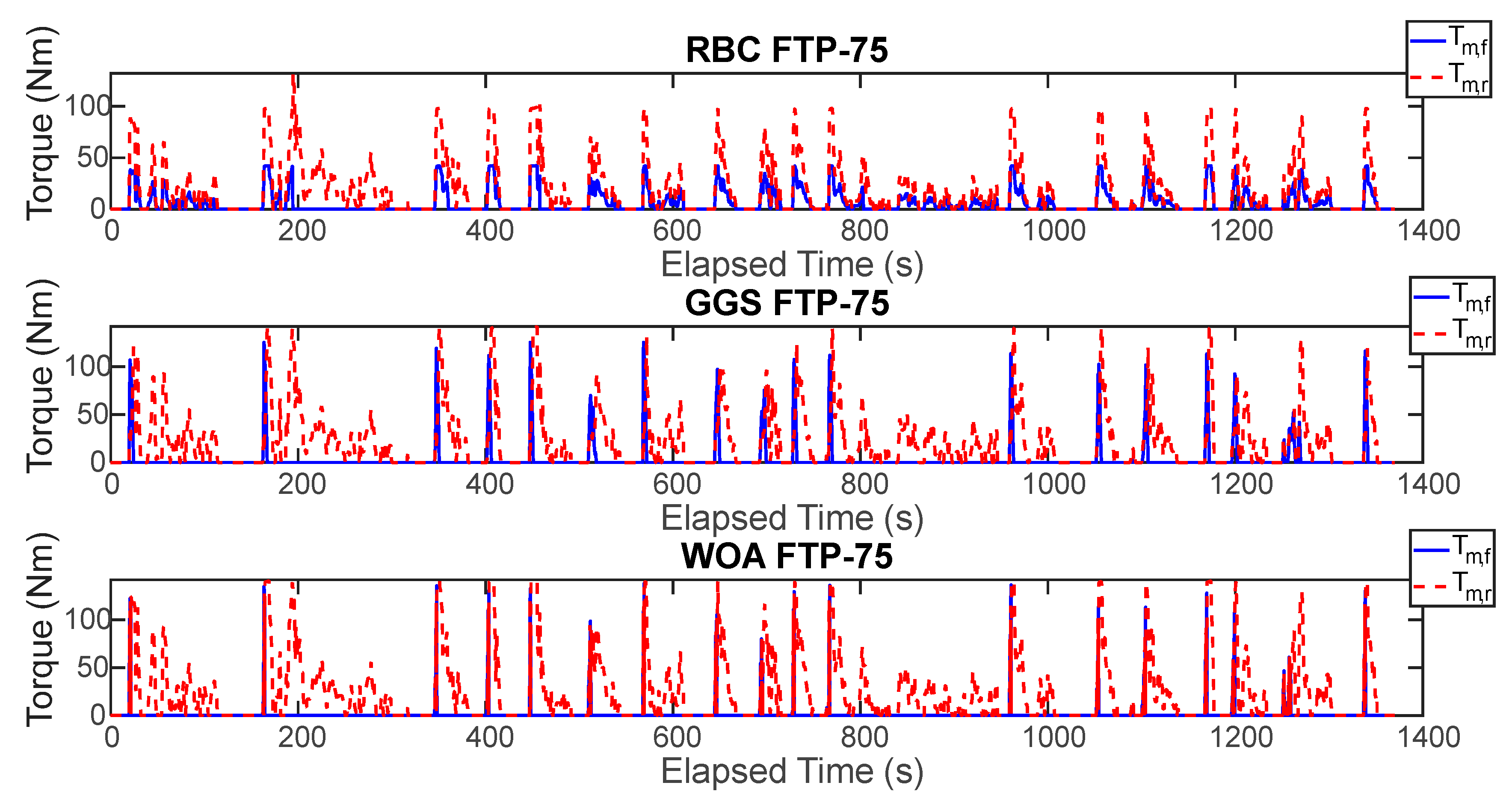

Figure 17.

Torque output of the front and rear axis motor for single FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 17.

Torque output of the front and rear axis motor for single FTP-75 driving cycle.

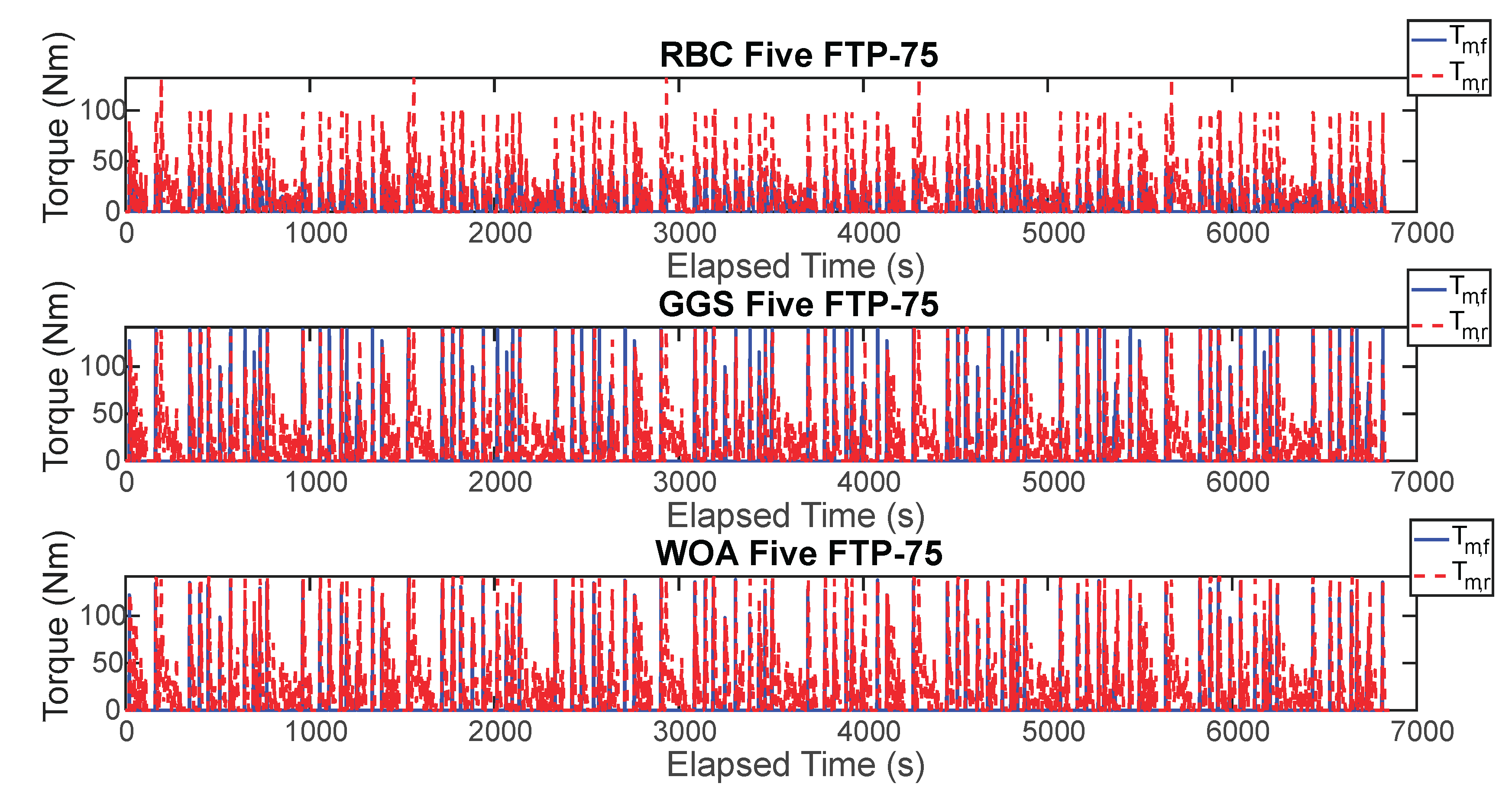

Figure 18.

Torque output of the front and rear axis motor for five FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 18.

Torque output of the front and rear axis motor for five FTP-75 driving cycle.

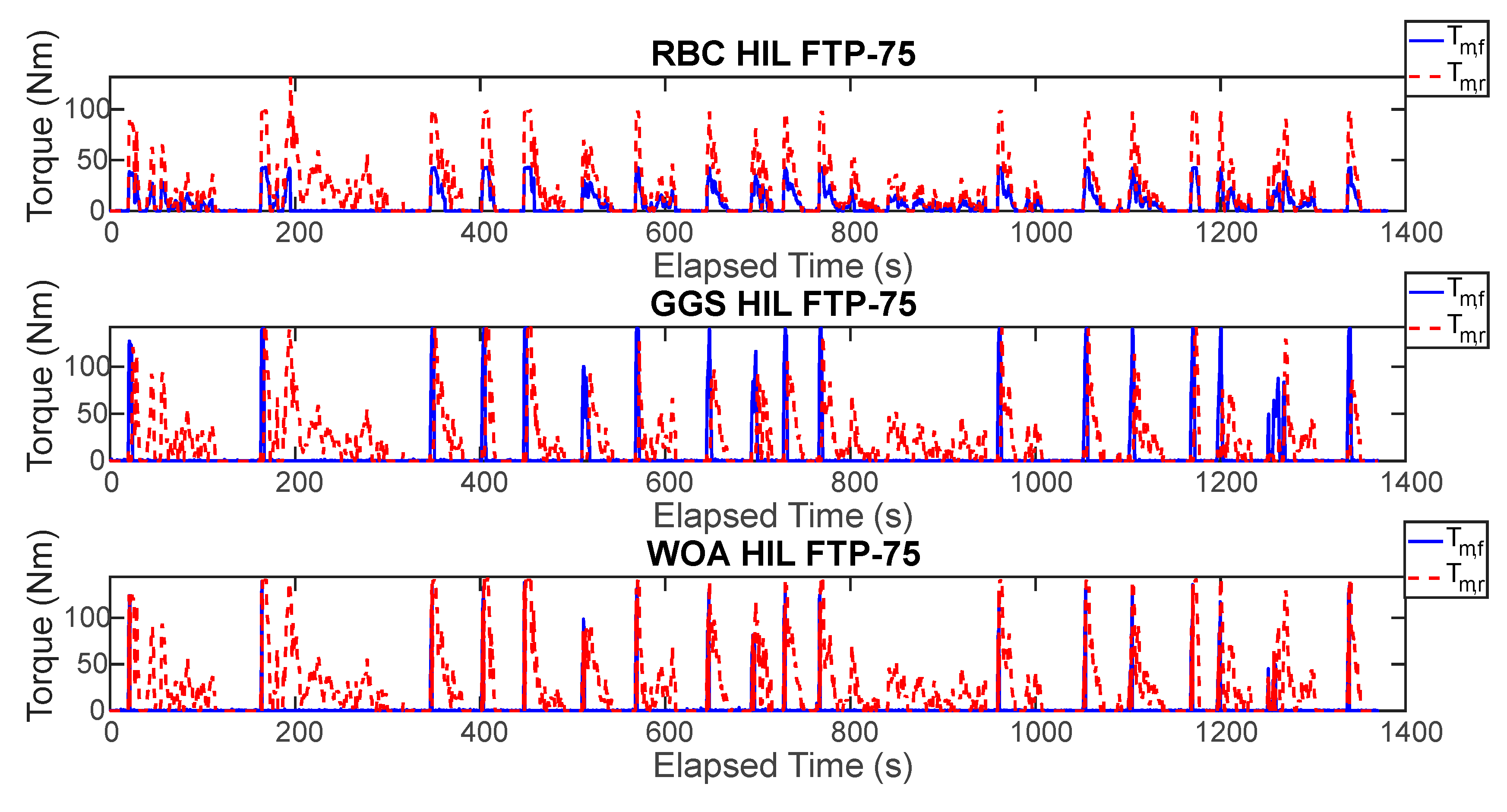

Figure 19.

HIL output results under different control strategies for single FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 19.

HIL output results under different control strategies for single FTP-75 driving cycle.

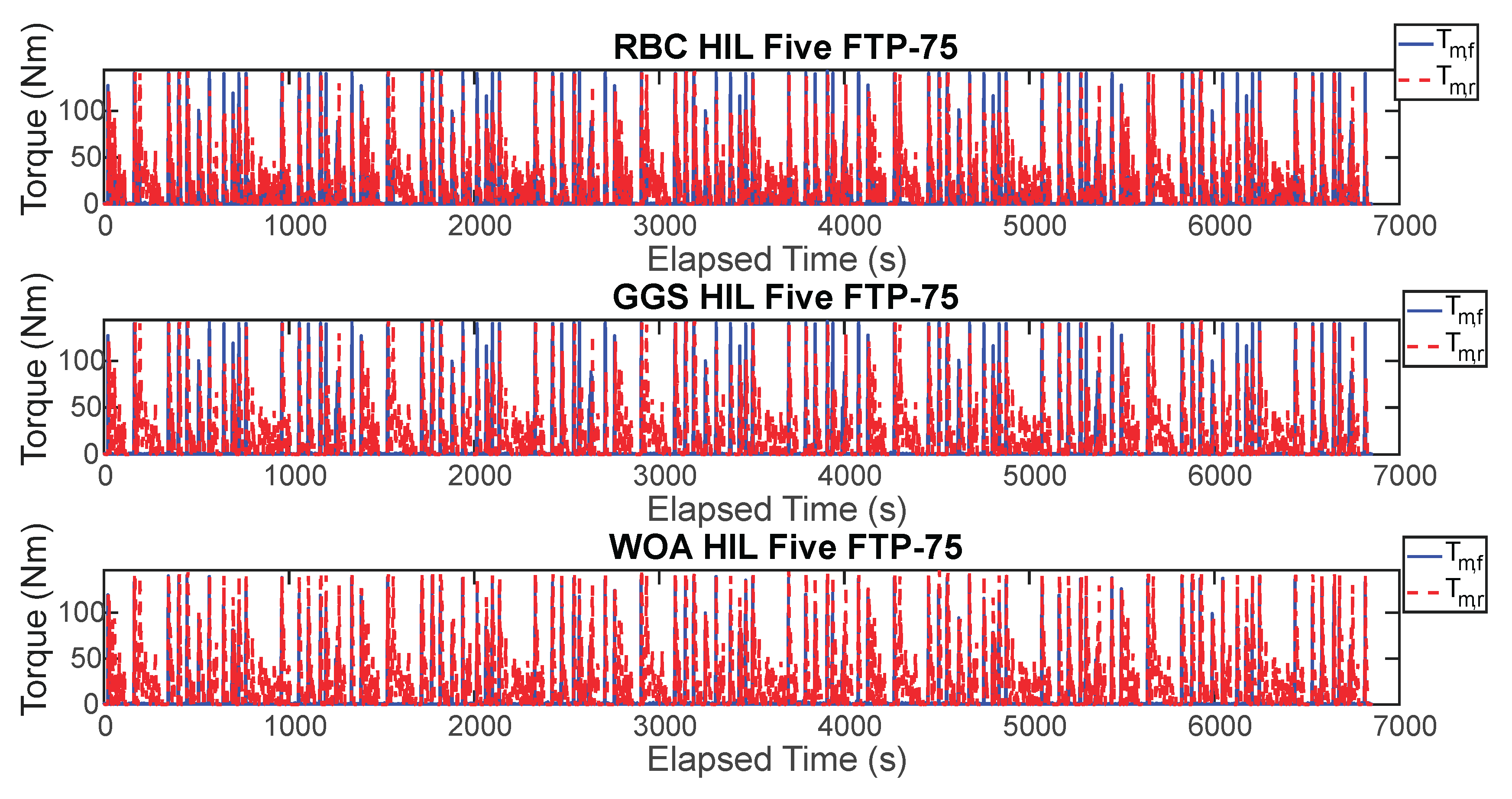

Figure 20.

HIL output results under different control strategies for five FTP-75 driving cycle.

Figure 20.

HIL output results under different control strategies for five FTP-75 driving cycle.

Table 1.

Specification of the electric vehicle.

Table 1.

Specification of the electric vehicle.

| Item |

Specification |

| Drive Motor |

Type |

Permanent Magnet Synchronous |

| Maximum Output Power |

250 kW*2 |

| Maximum Output Torque |

250 Nm@4,750 rpm |

| Energy Storage Battery |

Type |

Lithium-ion Battery |

| Rated Voltage |

432 V |

| Maximum Capacity |

64.58 kWh |

| Vehicle Parameters |

Vehicle Mass |

2373 kg |

| Aerodynamic Drag Coefficient |

0.24 |

| Frontal Area |

3.5 m2

|

| Tire Radius |

0.275 m |

| Rolling Resistance |

0.01 |

| Final Drive Ratio |

9.78 |

| Road Friction Coefficient |

0.95 |

Table 2.

Signal Conversion of the Arduino DUE and Ti C2000 microcontroller.

Table 2.

Signal Conversion of the Arduino DUE and Ti C2000 microcontroller.

| Range |

Arduino DUE |

Conversion |

Ti C2000 |

| -- |

Digital |

Analog |

-- |

Digital |

Analog |

| Min. |

0 |

0.56 V |

DAC |

0 |

0 V |

| Max. |

4095 |

2.76 V |

4095 |

3 V |

| Min. |

0 |

0 V |

ADC |

0 |

0 V |

| Max. |

4095 |

3.3 V |

4095 |

3 V |

Table 3.

Power distribution mode of the RBC.

Table 3.

Power distribution mode of the RBC.

| Mode |

Condition |

Action |

| System Ready |

Nm |

Nm; Nm |

| Low Load |

Nm |

;

|

| High Load |

50 km/h <

|

Nm;

|

| Safety |

= 0 Nm and SOC = 0 |

Nm; Nm |

Table 4.

The relevant parameters of the GGS for the front and rear axis motors.

Table 4.

The relevant parameters of the GGS for the front and rear axis motors.

| Parameter |

Value |

|

0 : 50 : 250 |

|

0 : 500 : 13000 |

|

0 : 0.1 : 1 |

Table 5.

Parameter settings of the WOA.

Table 5.

Parameter settings of the WOA.

| Parameter |

Value |

|

50 |

|

340 |

|

[0, 1] Random Value |

|

1 |

|

[–1, 1] Random Value |

|

)] |

Table 6.

Table 6. Energy Efficiency comparison of grid sizes for GGS.

Table 6.

Table 6. Energy Efficiency comparison of grid sizes for GGS.

| Grid Size |

Energy Efficiency (km/kWh) |

| 1 |

3.94008 |

| 0.5 |

3.94126 |

| 0.2 |

3.94221 |

| 0.1 |

3.94261 |

| 0.01 |

3.94361 |

| 0.005 |

N/A |

| 0.001 |

N/A |

Table 7.

Comparison of energy efficiency for different WOA iteration counts and whale population sizes.

Table 7.

Comparison of energy efficiency for different WOA iteration counts and whale population sizes.

| |

Count |

10 |

100 |

200 |

300 |

400 |

| Size |

|

| 10 |

3.87261 |

3.87987 |

3.88092 |

3.88101 |

N/A |

| 25 |

3.87666 |

3.88024 |

3.88093 |

3.88101 |

N/A |

| 50 |

3.87822 |

3.88045 |

3.88097 |

3.88102 |

N/A |

| 100 |

3.87824 |

3.88045 |

3.88097 |

3.88102 |

N/A |

| 150 |

3.87824 |

3.88045 |

3.88097 |

3.88102 |

N/A |

Table 8.

Energy efficiency comparison of WOA with 300 and 400 iterations.

Table 8.

Energy efficiency comparison of WOA with 300 and 400 iterations.

| |

Count |

300 |

320 |

340 |

360 |

380 |

| Size |

|

| 10 |

3.88102 |

3.88113 |

3.88129 |

N/A |

N/A |

Table 9.

Energy efficiency comparison of the pure simulation.

Table 9.

Energy efficiency comparison of the pure simulation.

| Strategy |

Energy Efficiency (km/kWh) |

Improvement Rate (%) |

| RBC |

3.5585 |

-- |

| GGS |

3.9188 |

9.1 |

| WOA |

3.9063 |

8.9 |

Table 10.

Energy efficiency comparison of the HIL simulation.

Table 10.

Energy efficiency comparison of the HIL simulation.

| Strategy |

Energy Efficiency (km/kWh) |

Improvement Rate (%) |

| RBC |

3.7510 |

-- |

| GGS |

3.9137 |

4.2 |

| WOA |

3.8991 |

3.8 |