Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

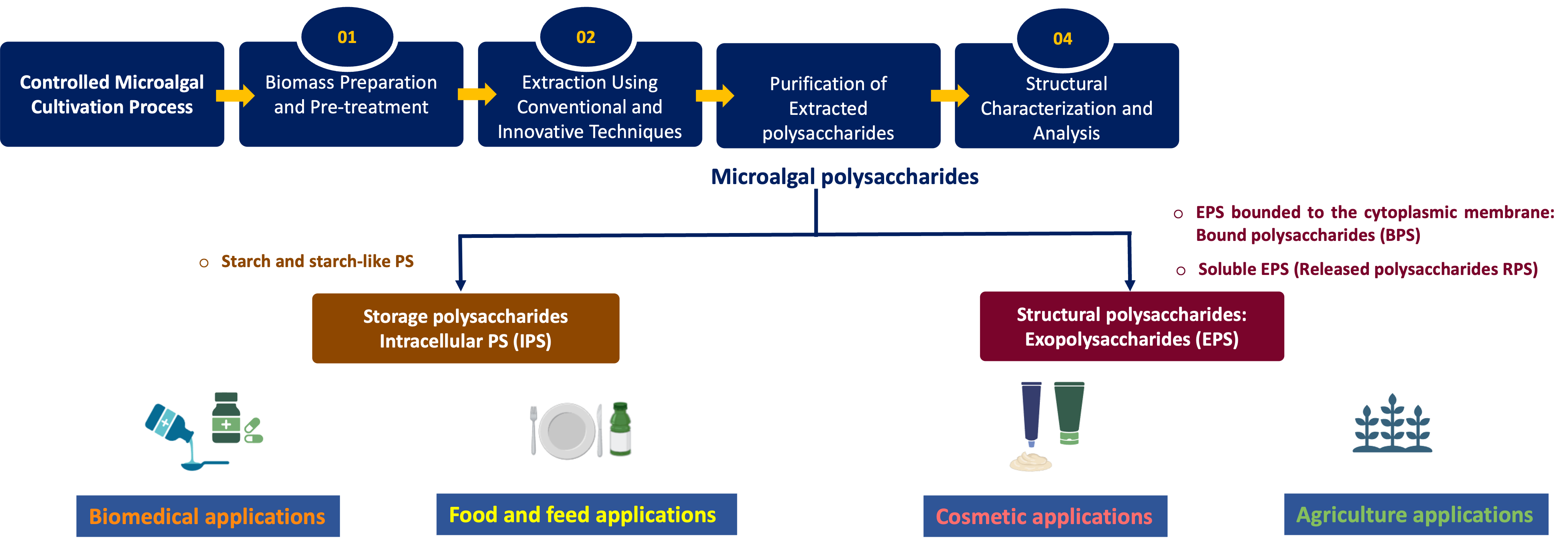

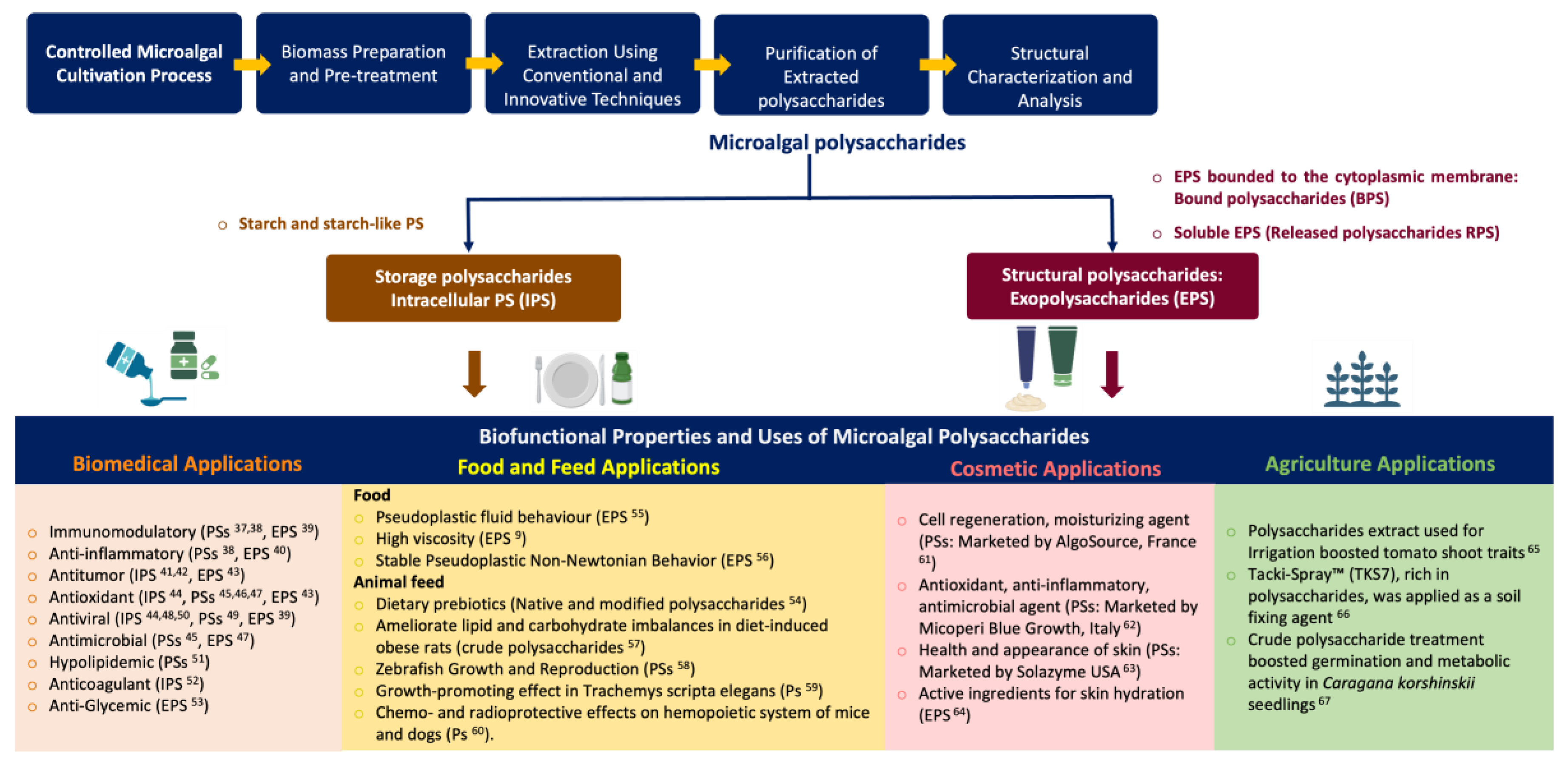

1. Introduction

2. Composition and Structure

3. Properties of EPS of Interest for Skin Care Products

3.1. Techno-Functional Properties of Microalgal EPS

3.2. Microalgal EPS Bio-Activities

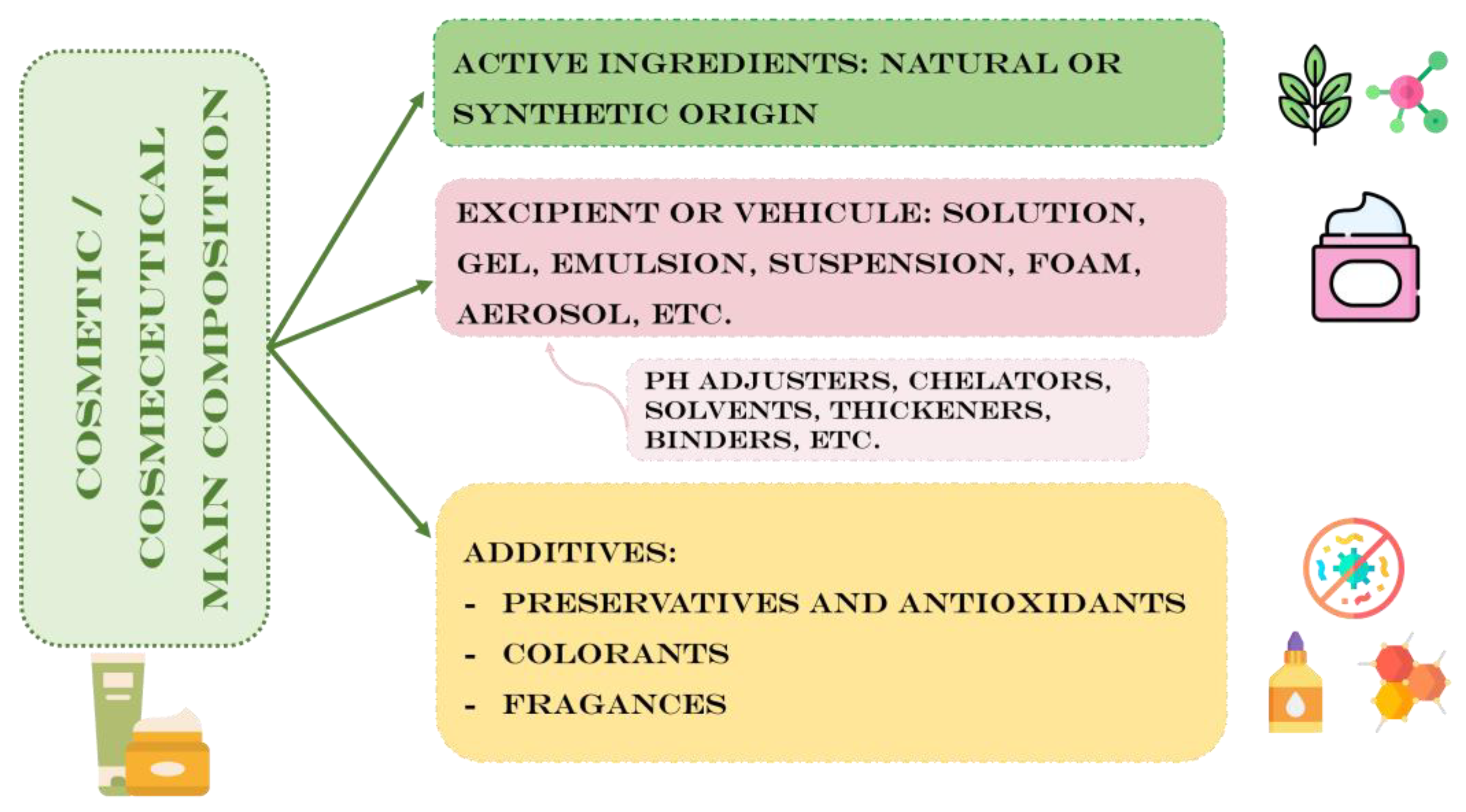

4. Microalgae and Cyanobacteria Exopolysaccharides: Cosmetic Properties and Potential Uses

5. Patents Claiming the Use of Microalgal and Cyanobacterial EPS in Skin Care

6. Challenges and Expected Developments

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, J. A. V.; Lucas, B. F.; Alvarenga, A. G. P.; Moreira, J. B.; De Morais, M. G. Microalgae Polysaccharides: An Overview of Production, Characterization, and Potential Applications. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Morgado, M.; Amador-Espejo, G. G.; Pérez-Cortés, M.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J. A. Microalgae and Cyanobacteria Polysaccharides: Important Link for Nutrient Recycling and Revalorization of Agro-Industrial Wastewater. Applied Food Research 2023, 3, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Philippis, R. Exocellular Polysaccharides from Cyanobacteria and Their Possible Applications. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 1998, 22, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnabosco, C.; Santaniello, G.; Romano, G. Microalgae: A Promising Source of Bioactive Polysaccharides for Biotechnological Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Barrow, C. J.; Puri, M. Multiproduct Biorefinery from Marine Thraustochytrids towards a Circular Bioeconomy. Trends in Biotechnology.

- Nguyen, D. T.; Johir, M. A. H.; Mahlia, T. M. I.; Silitonga, A. S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Nghiem, L. D. Microalgae-Derived Biolubricants: Challenges and Opportunities. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 954, 176759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakhu, S.; Sharma, Y.; Sharma, K.; Vaid, K.; Dhar, H.; Kumar, V.; Singh, R. P.; Shekh, A.; Kumar, G. Production and Characterization of Microalgal Exopolysaccharide as a Reducing and Stabilizing Agent for Green Synthesis of Gold-Nanoparticle: A Case Study with a Chlorella Sp. from Himalayan High-Altitude Psychrophilic Habitat. J Appl Phycol 2021, 33, 3899–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.; Athiyappan, K. D.; Balasubramanian, P. From Algae to Medicine: Unveiling the Therapeutic Potential of Microalgal Exopolysaccharides. In Microbial Biotechnology: Integrated Microbial Engineering for B3—Bioenergy, Bioremediation, and Bioproducts; Elsevier, 2025; pp 271–305. [CrossRef]

- Arad, S. (Malis); Levy-Ontman, O. Red Microalgal Cell-Wall Polysaccharides: Biotechnological Aspects. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2010, 21, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delattre, C.; Pierre, G.; Laroche, C.; Michaud, P. Production, Extraction and Characterization of Microalgal and Cyanobacterial Exopolysaccharides. Biotechnology Advances 2016, 34, 1159–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, G.; Delattre, C.; Dubessay, P.; Jubeau, S.; Vialleix, C.; Cadoret, J.-P.; Probert, I.; Michaud, P. What Is in Store for EPS Microalgae in the Next Decade? Molecules 2019, 24, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Philippis, R.; Colica, G.; Micheletti, E. Exopolysaccharide-Producing Cyanobacteria in Heavy Metal Removal from Water: Molecular Basis and Practical Applicability of the Biosorption Process. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 92, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.; Vasconcelos, V.; Pierre, G.; Michaud, P.; Delattre, C. Exopolysaccharides from Cyanobacteria: Strategies for Bioprocess Development. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanniyasi, E.; Patrick, A. P. R.; Rajagopalan, K.; Gopal, R. K.; Damodharan, R. Characterization and in Vitro Anticancer Potential of Exopolysaccharide Extracted from a Freshwater Diatom Nitzschia Palea (Kütz.) W.Sm. 1856. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 22114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laroche, C. Exopolysaccharides from Microalgae and Cyanobacteria: Diversity of Strains, Production Strategies, and Applications. Mar. Drugs 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaignard, C.; Laroche, C.; Pierre, G.; Dubessay, P.; Delattre, C.; Gardarin, C.; Gourvil, P.; Probert, I.; Dubuffet, A.; Michaud, P. Screening of Marine Microalgae: Investigation of New Exopolysaccharide Producers. Algal Research 2019, 44, 101711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, S.; Torres, C. A. V.; Sevrin, C.; Grandfils, C.; Reis, M. A. M.; Freitas, F. Extraction of the Bacterial Extracellular Polysaccharide FucoPol by Membrane-Based Methods: Efficiency and Impact on Biopolymer Properties. Polymers 2022, 14, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Gallón, S. M.; Alpaslan, E.; Wang, M.; Larese-Casanova, P.; Londoño, M. E.; Atehortúa, L.; Pavón, J. J.; Webster, T. J. Characterization and Study of the Antibacterial Mechanisms of Silver Nanoparticles Prepared with Microalgal Exopolysaccharides. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 99, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, O. N.; Bobby, Md. N.; Kondi, V.; Halder, G.; Kargarzadeh, H.; Ikbal, A. M. A.; Bhunia, B.; Thomas, S.; Efferth, T.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Palit, P. Comprehensive Review on Recent Trends and Perspectives of Natural Exo-Polysaccharides: Pioneering Nano-Biotechnological Tools. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 265, 130747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheirsilp, B.; Maneechote, W.; Srinuanpan, S.; Angelidaki, I. Microalgae as Tools for Bio-Circular-Green Economy: Zero-Waste Approaches for Sustainable Production and Biorefineries of Microalgal Biomass. Bioresource Technology 2023, 387, 129620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. C.; Attar, S. B.-E.; Sanchez-Zurano, A.; Ciardi, M.; Morillas-Espana, A.; Ruiz-Martínez, C.; Fernandez, I.; Arrabal-Campos, F. M.; Pontes, L. A. M.; Cardoso, L. G.; de Souza, C. O.; Acien, G.; Assis, D. de J. Exopolysaccharides as Bio-Based Rheology Modifiers from Microalgae Produced on Dairy Industry Waste: Towards a Circular Bioeconomy Approach. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules.

- CN110818814A. https://patents.google.com/patent/CN110818814A/en.

- Liberti, D.; Imbimbo, P.; Giustino, E.; D’Elia, L.; Silva, M.; Barreira, L.; Monti, D. M. Shedding Light on the Hidden Benefit of Porphyridium Cruentum Culture. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Muthuraj, M.; Bandyopadhyay, T. K.; Bobby, Md. N.; Vanitha, K.; Tiwari, O. N.; Bhunia, B. Engineering Strategies and Applications of Cyanobacterial Exopolysaccharides: A Review on Past Achievements and Recent Perspectives. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 328, 121686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafana, A. Characterization and Optimization of Production of Exopolysaccharide from Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. Carbohydrate Polymers 2013, 95, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, M. G.; Santos, T. D.; Moraes, L.; Vaz, B. S.; Morais, E. G.; Costa, J. A. V. Exopolysaccharides from Microalgae: Production in a Biorefinery Framework and Potential Applications. Bioresource Technology Reports 2022, 18, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J. B.; Kuntzler, S. G.; Bezerra, P. Q. M.; Cassuriaga, A. P. A.; Zaparoli, M.; Da Silva, J. L. V.; Costa, J. A. V.; De Morais, M. G. Recent Advances of Microalgae Exopolysaccharides for Application as Bioflocculants. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.-T.; Go, R.-E.; Lee, H.-M.; Lee, G.-A.; Kim, C.-W.; Seo, J.-W.; Hong, W.-K.; Choi, K.-C.; Hwang, K.-A. Potential Anti-Proliferative and Immunomodulatory Effects of Marine Microalgal Exopolysaccharide on Various Human Cancer Cells and Lymphocytes In Vitro. Mar Biotechnol 2017, 19, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, P.; Matulová, M.; Molitorisová, M.; Kazimierová, I. Chlorella Vulgaris α-L-Arabino-α-L-Rhamno-α,β-D-Galactan Structure and Mechanisms of Its Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Remodelling Effects. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concórdio-Reis, P.; David, H.; Reis, M. A. M.; Amorim, A.; Freitas, F. Bioprospecting for New Exopolysaccharide-Producing Microalgae of Marine Origin. Int Microbiol 2023, 26, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R. Production and Characterization of Exopolysaccharides from Salinity-Induced Auxenochlorella Protothecoides and the Analysis of Anti-Inflammatory Activity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CN108559006A. https://patents.google.com/patent/CN108559006A/en?oq=CN108559006A.

- Borjas Esqueda, A.; Gardarin, C.; Laroche, C. Exploring the Diversity of Red Microalgae for Exopolysaccharide Production. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Philippis, R.; Sili, C.; Paperi, R.; Vincenzini, M. Exopolysaccharide-Producing Cyanobacteria and Their Possible Exploitation: A Review. Journal of Applied Phycology 2001, 13, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, I. A.; Dias, R. R.; Do Nascimento, T. C.; Deprá, M. C.; Maroneze, M. M.; Zepka, L. Q.; Jacob-Lopes, E. Microalgae-Derived Polysaccharides: Potential Building Blocks for Biomedical Applications. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2022, 38, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ji, L.; Yuan, Y.; Rui, D.; Li, J.; Cheng, P.; Sun, L.; Fan, J. Recent Advances in Polysaccharide-Dominated Extracellular Polymeric Substances from Microalgae: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 302, 140572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Kim, S. M. Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activities of Polysaccharides Extracted from Green Alga Chlorella Ellipsoidea. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 95, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, S.; Gato, A.; Lamela, M.; Freire-Garabal, M.; Calleja, J. M. Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Activities of Polysaccharide from Chlorella Stigmatophora and Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Phytotherapy Research 2003, 17, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, J. H.; Kim, S. J.; Ahn, S. H.; Lee, C. K.; Rhie, K. T.; Lee, H. K. Antiviral Effects of Sulfated Exopolysaccharide from the Marine Microalga Gyrodinium Impudicum Strain KG03. Marine Biotechnology 2004, 6, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barboríková, J. Extracellular Polysaccharide Produced by Chlorella Vulgaris—Chemical Characterization and Anti-Asthmatic Profile. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardeva, E.; Toshkova, R.; Minkova, K.; Gigova, L. Cancer Protective Action of Polysaccharide, Derived from Red Microalga Porphyridium Cruentum —A Biological Background. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2009, 23 (Suppl. S1), 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Wang, Z.-J.; Xie, D.; Sun, X.; Yang, W.; Zhao, X.; Xu, N. Characterization and Potential Antitumor Activity of Polysaccharide from Gracilariopsis Lemaneiformis. Marine Drugs 2017, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Ren, Y.; Chen, F. Characterization of Exopolysaccharides Produced by Microalgae with Antitumor Activity on Human Colon Cancer Cells. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhu, S.; Yin, H.; Wang, M.; Tang, J. Sugar Compositional Determination of Polysaccharides from Dunaliella Salina by Modified RP-HPLC Method of Precolumn Derivatization with 1-Phenyl-3-Methyl-5-Pyrazolone. Carbohydrate Polymers 2010, 82, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amna Kashif, S.; Hwang, Y. J.; Park, J. K. Potent Biomedical Applications of Isolated Polysaccharides from Marine Microalgae Tetraselmis Species. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2018, 41, 1611–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Jia, S.; Wu, Y.; Yan, R.; Lin, Y.-H.; Zhao, D.; Han, P. Effect of Culture Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties and Antioxidant Activities of Polysaccharides from Nostoc Flagelliforme. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 198, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.; Yang, S.; Wan, J.; Su, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. Optimization for the Extraction of Polysaccharides from Nostoc Commune and Its Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2015, 52, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, M.; De Morais, R.; Bernardo De Morais, A. Bioactivity and Applications of Sulphated Polysaccharides from Marine Microalgae. Marine Drugs 2013, 11, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoyo, S.; Jaime, L.; Plaza, M.; Herrero, M.; Rodriguez-Meizoso, I.; Ibañez, E.; Reglero, G. Antiviral Compounds Obtained from Microalgae Commonly Used as Carotenoid Sources. J Appl Phycol 2012, 24, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandezcorona, A.; Nieves, I.; Meckes, M.; Chamorro, G.; Barron, B. Antiviral Activity of Spirulina Maxima against Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2. Antiviral Research 2002, 56, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Ai, C.; Chen, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhong, R.; Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Zhao, C. Physicochemical Characterization of a Polysaccharide from Green Microalga Chlorella Pyrenoidosa and Its Hypolipidemic Activity via Gut Microbiota Regulation in Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdoub, H.; Mansour, M. B.; Chaubet, F.; Roudesli, M. S.; Maaroufi, R. M. Anticoagulant Activity of a Sulfated Polysaccharide from the Green Alga Arthrospira Platensis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—General Subjects 2009, 1790, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyaningsih, I.; Prasetyo, H.; Agungpriyono, D. R.; Tarman, K. Antihyperglycemic Activity of Porphyridium Cruentum Biomass and Extra-Cellular Polysaccharide in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 156, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, V. P. B.; De Souza, E. L.; De Albuquerque, T. M. R.; Da Costa Sassi, C. F.; Dos Santos Lima, M.; Sivieri, K.; Pimentel, T. C.; Magnani, M. Freshwater Microalgae Biomasses Exert a Prebiotic Effect on Human Colonic Microbiota. Algal Research 2021, 60, 102547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, O. N. Purification, Characterization and Biotechnological Potential of New Exopolysaccharide Polymers Produced by Cyanobacterium Anabaena Sp. CCC 745. CCC 745. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, N.; Pal Singh, D.; Singh Khattar, J. Optimization, Characterization, and Flow Properties of Exopolysaccharides Produced by the Cyanobacterium Lyngbya Stagnina: Exopolysaccharides from Lyngbya Stagnina. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013, 53, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.-T.; Huang, Z.-R.; Jia, R.-B.; Lv, X.-C.; Zhao, C.; Liu, B. Spirulina Platensis Polysaccharides Attenuate Lipid and Carbohydrate Metabolism Disorder in High-Sucrose and High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats in Association with Intestinal Microbiota. Food Research International 2021, 147, 110530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekar, P.; Palanisamy, S.; Anjali, R.; Vinosha, M.; Elakkiya, M.; Marudhupandi, T.; Tabarsa, M.; You, S.; Prabhu, N. M. Isolation and Structural Characterization of Sulfated Polysaccharide from Spirulina Platensis and Its Bioactive Potential: In Vitro Antioxidant, Antibacterial Activity and Zebrafish Growth and Reproductive Performance. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 141, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-X.; Liu, X.-Y.; Xiao, Z.; Huang, Y.-F.; Liu, B. Antioxidant Activities of Polysaccharides Obtained from Chlorella Pyrenoidosa via Different Ethanol Concentrations. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2016, 91, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Q. , Lin, A.P., Sun, Y., Deng, Y.M. Chemo- and Radio-Protective Effects of Polysaccharide of Spirulina Platensis on Hemopoietic System of Mice and Dogs. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 2001, No. 22, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Algosource. http://www.algosource.com.

- Micoperibeg. http://www.micoperibg.eu.

- Solazyme. http://solazymeindustrials.com.

- Givaudan. https://www.givaudan.com/fragrance beauty/active-beauty/products/hydrintense.

- Rachidi, F.; Benhima, R.; Sbabou, L.; El Arroussi, H. Microalgae Polysaccharides Bio-Stimulating Effect on Tomato Plants: Growth and Metabolic Distribution. Biotechnology Reports 2020, 25, e00426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-H.; Li, X. R.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, R. L.; Hur, J.-S. Rapid Development of Cyanobacterial Crust in the Field for Combating Desertification. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Rossi, F.; Colica, G.; Deng, S.; De Philippis, R.; Chen, L. Use of Cyanobacterial Polysaccharides to Promote Shrub Performances in Desert Soils: A Potential Approach for the Restoration of Desertified Areas. Biol Fertil Soils 2013, 49, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guehaz, K.; Boual, Z.; Abdou, I.; Telli, A.; Belkhalfa, H. Microalgae’s Polysaccharides, Are They Potent Antioxidants? Critical Review. Arch Microbiol 2024, 206, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, R.; Vidal, R.; Pandeirada, C.; Flores, C.; Adessi, A.; De Philippis, R.; Nunes, C.; Coimbra, M. A.; Tamagnini, P. Cyanoflan: A Cyanobacterial Sulfated Carbohydrate Polymer with Emulsifying Properties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 229, 115525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaerts, T. M. M.; Gheysen, L.; Foubert, I.; Hendrickx, M. E.; Van Loey, A. M. The Potential of Microalgae and Their Biopolymers as Structuring Ingredients in Food: A Review. Biotechnology Advances 2019, 37, 107419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulong, V.; Rihouey, C.; Gaignard, C.; Bridiau, N.; Gourvil, P.; Laroche, C.; Pierre, G.; Varacavoudin, T.; Probert, I.; Maugard, T.; Michaud, P.; Picton, L. Exopolysaccharide from Marine Microalgae Belonging to the Glossomastix Genus: Fragile Gel Behavior and Suspension Stability.

- Estevinho, B. N.; Mota, R.; Leite, J. P.; Tamagnini, P.; Gales, L.; Rocha, F. Application of a Cyanobacterial Extracellular Polymeric Substance in the Microencapsulation of Vitamin B12. Powder Technology 2019, 343, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattom, A.; Shilo, M. Production of Emulcyan by Phormidium J-1: Its Activity and Function. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1985, 31, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US5250201A. https://patents.google.com/patent/US5250201A/en.

- Borah, D.; Rethinam, G.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Rout, J.; Alharbi, N. S.; Alharbi, S. A.; Nooruddin, T. Ozone Enhanced Production of Potentially Useful Exopolymers from the Cyanobacterium Nostoc Muscorum. Polymer Testing 2020, 84, 106385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Hayashi, K.; Maeda, M.; Kojima, I. Calcium Spirulan, an Inhibitor of Enveloped Virus Replication, from a Blue-Green Alga Spirulina Platensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radonić, A.; Thulke, S.; Achenbach, J.; Kurth, A.; Vreemann, A.; König, T.; Walter, C.; Possinger, K.; Nitsche, A. Anionic Polysaccharides From Phototrophic Microorganisms Exhibit Antiviral Activities to Vaccinia Virus. Robert Koch-Institut, Biologische Sicherheit , 2011. 3 January. [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, K.; Tanida, Y.; Hata, K.; Hayashi, T.; Hashim, I. I. A.; Higashi, T.; Ishitsuka, Y.; Kondo, Y.; Irie, T.; Kaneko, S.; Arima, H. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Novel Polysaccharide Sacran Extracted from Cyanobacterium Aphanothece Sacrum in Various Inflammatory Animal Models. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2016, 39, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, J.; Konstantinidou, A.; Kabaivanova, L.; Georgieva, A.; Vladov, I.; Petkova, S. Examination of Exopolysaccharides from Porphyridium Cruentum for Estimation of Their Potential Antitumour Activity in Vitro. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2022, 75, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavian, Z.; Safavi, M.; Azizmohseni, F.; Hadizadeh, M.; Mirdamadi, S. Characterization, Antioxidant and Anticoagulant Properties of Exopolysaccharide from Marine Microalgae. AMB Expr 2022, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhliariková, I.; Matulová, M.; Capek, P. Structural Features of the Bioactive Cyanobacterium Nostoc Sp. Exopolysaccharide. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 164, 2284–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Baranwal, M.; Pandey, S. K.; Reddy, M. S. Hetero-Polysaccharides Secreted from Dunaliella Salina Exhibit Immunomodulatory Activity Against Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Indian J Microbiol 2019, 59, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.; Tadda, M. A.; Zhao, Y.; Farmanullah, F.; Chu, B.; Li, X.; He, Y. Microalgae Bioactive Carbohydrates as a Novel Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Source of Prebiotics: Emerging Health Functionality and Recent Technologies for Extraction and Detection. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 806692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, V.; Oliveira, R.; Dias, A. C. P. Microalgae and Cyanobacteria as Sources of Bioactive Compounds for Cosmetic Applications: A Systematic Review. Algal Research 2023, 76, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, M. S.; Muizzuddin, N.; Arad, S.; Marenus, K. Sulfated Polysaccharides from Red Microalgae Have Antiinflammatory Properties In Vitro and In Vivo. ABAB 2003, 104, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanekiyo, K.; Lee, J.-B.; Hayashi, K.; Takenaka, H.; Hayakawa, Y.; Endo, S.; Hayashi, T. Isolation of an Antiviral Polysaccharide, Nostoflan, from a Terrestrial Cyanobacterium, Nostoc f Lagelliforme. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; You, W.; Huang, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, W. Isolation and Antioxidant Property of the Extracellular Polysaccharide from Rhodella Reticulata. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 26, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challouf, R.; Trabelsi, L.; Ben Dhieb, R.; El Abed, O.; Yahia, A.; Ghozzi, K.; Ben Ammar, J.; Omran, H.; Ben Ouada, H. Evaluation of Cytotoxicity and Biological Activities in Extracellular Polysaccharides Released by Cyanobacterium Arthrospira Platensis. Braz. arch. biol. technol. 2011, 54, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny Cristian Díaz Bayona; Sandra Milena Navarro GallónSandra Milena Navarro Gallón; Andres Lara EstradaAndres Lara Estrada; Jhonny Colorado-Rios; Lucía Atehortúa G. ; Alejandro Martinez Martinez. Activity of Sulfated Polysaccharides from Microalgae Porphyridium Cruentum over Degenerative Mechanisms of the Skin. International Journal of Science and Advanced Technology 2012, 2, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, Y.; Jia, S. Emulsifying, Flocculating, and Physicochemical Properties of Exopolysaccharide Produced by Cyanobacterium Nostoc Flagelliforme. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2014, 172, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, M. F. D. J.; De Morais, A. M. M. B.; De Morais, R. M. S. C. Influence of Sulphate on the Composition and Antibacterial and Antiviral Properties of the Exopolysaccharide from Porphyridium Cruentum. Life Sciences 2014, 101, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M. H.; Abou-ElWaf, G. S.; Shaaban-De, S. A.; Hassan, N. I. Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Exopolysaccharide Secreted by Nostoc Carneum. International J. of Pharmacology 2015, 11, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, A. B.; Omarsdottir, S.; Brynjolfsdottir, A.; Paulsen, B. S.; Olafsdottir, E. S.; Freysdottir, J. Exopolysaccharides from Cyanobacterium Aponinum from the Blue Lagoon in Iceland Increase IL-10 Secretion by Human Dendritic Cells and Their Ability to Reduce the IL-17+RORγt+/IL-10+FoxP3+ Ratio in CD4+ T Cells. Immunology Letters 2015, 163, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabelsi, L.; Chaieb, O.; Mnari, A.; Abid-Essafi, S.; Aleya, L. Partial Characterization and Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of the Aqueous Extracellular Polysaccharides from the Thermophilic Microalgae Graesiella Sp. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016, 16, 210. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016, 16, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, O. N.; Muthuraj, M.; Bhunia, B.; Bandyopadhyay, T. K.; Annapurna, K.; Sahu, M.; Indrama, T. Biosynthesis, Purification and Structure-Property Relationships of New Cyanobacterial Exopolysaccharides. Polymer Testing 2020, 89, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, R. M.; Adessi, A.; Caldara, F.; Codato, A.; Furlan, M.; Rampazzo, C.; De Philippis, R.; La Rocca, N.; Dalla Valle, L. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Exopolysaccharides from Phormidium Sp. ETS05, the Most Abundant Cyanobacterium of the Therapeutic Euganean Thermal Muds, Using the Zebrafish Model. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risjani, Y.; Mutmainnah, N.; Manurung, P.; Wulan, S. N.; Yunianta. Exopolysaccharide from Porphyridium Cruentum (Purpureum) Is Not Toxic and Stimulates Immune Response against Vibriosis: The Assessment Using Zebrafish and White Shrimp Litopenaeus Vannamei. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Riofrío, G.; García-Márquez, J.; Casas-Arrojo, V.; Uribe-Tapia, E.; Abdala-Díaz, R. T. Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Effects on Tumor Cells of Exopolysaccharides from Tetraselmis Suecica (Kylin) Butcher Grown Under Autotrophic and Heterotrophic Conditions. Mar. Drugs 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drira, M.; Elleuch, J.; Ben Hlima, H.; Hentati, F.; Gardarin, C.; Rihouey, C.; Le Cerf, D.; Michaud, P.; Abdelkafi, S.; Fendri, I. Optimization of Exopolysaccharides Production by Porphyridium Sordidum and Their Potential to Induce Defense Responses in Arabidopsis Thaliana against Fusarium Oxysporum. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, X.; Alves, A.; Ribeiro, M. P.; Lazzari, M.; Coutinho, P.; Otero, A. Biochemical Characterization of Nostoc Sp. Exopolysaccharides and Evaluation of Potential Use in Wound Healing. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 254, 117303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwal, T.; Baranwal, M. Scenedesmus Acutus Extracellular Polysaccharides Produced under Increased Concentration of Sulphur and Phosphorus Exhibited Enhanced Proliferation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhliariková, I.; Matulová, M.; Košťálová, Z.; Lukavský, J.; Capek, P. Lactylated Acidic Exopolysaccharide Produced by the Cyanobacterium Nostoc Cf. Linckia. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 276, 118801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gongi, W.; Gomez Pinchetti, J. L.; Cordeiro, N.; Ouada, H. B. Extracellular Polymeric Substances Produced by the Thermophilic Cyanobacterium Gloeocapsa Gelatinosa: Characterization and Assessment of Their Antioxidant and Metal-Chelating Activities. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.-N.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.-L.; Xiang, W.-Z.; Li, A.-F. Exopolysaccharides from the Energy Microalga Strain Botryococcus Braunii: Purification, Characterization, and Antioxidant Activity. 2022.

- Toucheteau, C.; Deffains, V.; Gaignard, C.; Rihouey, C.; Laroche, C.; Pierre, G.; Lépine, O.; Probert, I.; Le Cerf, D.; Michaud, P.; Arnaudin-Fruitier, I.; Bridiau, N.; Maugard, T. Role of Some Structural Features in EPS from Microalgae Stimulating Collagen Production by Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Bioengineered 2023, 14, 2254027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, F. B.; Guermazi, W.; Chamkha, M.; Bellassoued, K.; Salah, H. B.; Harrath, A. H.; Aldahmash, W.; Rahman, M. A.; Ayadi, H. Bioactive Potential of the Sulfated Exopolysaccharides From the Brown Microalga Halamphora Sp.: Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Antiapoptotic Profiles. Analytical Science Advances 2024, 5, (9–10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbaoui, A.; Khelifi, N.; Aissaoui, N.; Muzard, M.; Martinez, A.; Smaali, I. A Novel Bioactive and Functional Exopolysaccharide from the Cyanobacterial Strain Arthrospira Maxima Cultivated under Salinity Stress. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2025, 48, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehouri, M. Marennine et Exopolysaccharides de La Microalgue Bleue Haslea Ostrearia : Potentiel d’application Cosmétique et Pharmaceutique, 2024. https://semaphore.uqar.ca/id/eprint/3199/.

- Vazquez-Ayala, L.; Angel-Olarte, C. D.; Escobar-García, D. M.; Rosales-Mendoza, S.; Solis-Andrade, I.; Pozos-Guillen, A.; Palestino, G. Chitosan Sponges Loaded with Metformin and Microalgae as Dressing for Wound Healing: A Study in Diabetic Bio-Models. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US9095733B2. https://patents.google.com/patent/US9095733B2/en.

- ES2718275T3. https://patents.google.com/patent/US8277849B2/en.

- EP3398606A1. https://patents.google.com/patent/EP3398606A1/fr.

- US20240358628A1. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20240358628A1/en?oq=US20240358628A1.

- EP2265249A1. https://patents.google.com/patent/EP2265249A1/en?oq=EP2265249A1.

- US12268772B2. https://patents.google.com/patent/US12268772B2/en?oq=US12268772B2.

- FR2102020. https://hal.science/hal-03506901v1.

- Br102012004631a2. https://patents.google.com/patent/BR102012004631A2/en?oq=BR102012004631A2.

- FR2982152A1. https://patents.google.com/patent/FR2982152A1/en?oq=FR2982152A1.

- US20200232003A1. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20200232003A1/en?oq=US20200232003A1.

- BRPI1004637A2. https://patents.google.com/patent/BRPI1004637A2/en?oq=BRPI1004637A2.

- CN105685766A. https://patents.google.com/patent/CN105685766A/en?oq=CN105685766A.

- Michaud, P. Polysaccharides from Microalgae, What’s Future? aibm 2018, 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofoli, N. L.; Lima, A. R.; Rosa Da Costa, A. M.; Evtyugin, D.; Silva, C.; Varela, J.; Vieira, M. C. Structural Characterization of Exopolysaccharides Obtained from Porphyridium Cruentum Exhausted Culture Medium. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2023, 138, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargouch, N.; Elleuch, F.; Karkouch, I.; Tabbene, O.; Pichon, C.; Gardarin, C.; Rihouey, C.; Picton, L.; Abdelkafi, S.; Fendri, I.; Laroche, C. Potential of Exopolysaccharide from Porphyridium Marinum to Contend with Bacterial Proliferation, Biofilm Formation, and Breast Cancer. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Bhatia, S.; Gupta, U.; Decker, E.; Tak, Y.; Bali, M.; Gupta, V. K.; Dar, R. A.; Bala, S. Microalgal Bioactive Metabolites as Promising Implements in Nutraceuticals and Pharmaceuticals: Inspiring Therapy for Health Benefits. Phytochem Rev 2023, 22, 903–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A. M.; Gonçalves, M. C.; Marques, M. S.; Veiga, F.; Paiva-Santos, A. C.; Pires, P. C. In Vitro Models for Anti-Aging Efficacy Assessment: A Critical Update in Dermocosmetic Research. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus /Species / Strain | EPS | Activity | Reference | Potential cosmetic use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirulina platensis | Calcium spirulan (Rha, Rib, Man, Fru, Gal, Xyl, Glu, GlcA, GalA, sulfate, and calcium) |

Antiviral: replication inhibition of several enveloped viruses |

[76] | Antimicrobial (active ingredient/preservative) |

| Porphyridium sp | Main sugars: Xyl, Glc, Gal Glycoproteins and sulfate |

In vitro: Inhibition migration of polymorphonuclear leucocytes In vivo: Inhibition induced cutaneous erythema |

[85] | Anti-inflammatory |

| Nostoc flagelliforme | Nostoflan (Glc, Gal, Xyl, and Man) |

Potent anti-herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) activity | [86] |

Antimicrobial (active ingredient/preservative) |

| Arthrospira platensis | Calcium spirulan | Antiviral: Inhibition of orthopoxvirus and other enveloped viruses |

[77] | Antimicrobial (active ingredient/preservative) |

| Rhodella reticulata | Deproteinized EPS | Antioxidant | [87] | Antioxidant |

| Arthrospira platensis | Methanolic and aqueous EPS extracts (composition not reported) |

Antibacterial Antioxidant |

[88] | Antibacterial (preservative) Antioxidant |

| Porphyridium cruentum | Main sugars: Xyl, Gal, Glu | Inhibition of the collagenase, elastase, and hyaluronidase activity | [89] | Antiaging |

| Nostoc flagelliforme | 41.2 % Glc, 21.1 % Gal, 21.0 % Man, 2.5 % Fru, 3.6 % Rib, 1.7 % Xyl, 0.6 % Ara, 3.0 % Rha, 0.9 % Fuc, and 4.3 % GlcA | Strong emulsion-stabilizing capacity | [90] | Emulsifier and stabilizer |

| Porphyridium cruentum | Carbohydrates and uronic acids Main sugars: Gal, Glu, and Ara; Minor: Man, Fuc, Xyl, Rha |

Antibacterial and antiviral activities High viscosity values at low shear rates |

[91] | Antibacterial (preservative) Rheological agent |

| Nostoc carneum | Xyl, Glu, and uronic acid | Antioxidant Pseudoplastic fluid behavior |

[92] | Antioxidant Gelling and emulsifier agent |

| Cyanobacterium aponinum | GalA/Fuc/3-OMe-GalA/Glc/Ara/Gal/Man/Rha in a molar ratio of 24:24:17:16:10:4:3:2 | Production of immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 | [93] | Anti-inflammatory |

| Graesiella sp. | Carbohydrate (52 %), uronic acids (23 %), ester sulfate (11 %), and protein (12 %) Carbohydrate fraction: Glc, Gal, Man, Fuc, Rha, Xyl, Ara, and Rib |

Scavenging activity | [94] | Antioxidant |

| Anabaena sp. CCC 745 | Heteropolysaccharide composed of Glc, Xyl, Rha, and GlcA | Antioxidant Pseudoplastic fluid behavior |

[55] | Antioxidant Rheological agent |

| Anabaena sp. CCC 746 | Main monosaccharides Glc, Xyl, and GlcA | Antioxidant Scavenging activity Pseudoplastic fluid behavior |

[95] | Antioxidant Rheological agent |

| Phormidium sp ETS05 | Xyl, Rha, Glc, Man, Ara, GlcN, GalA, and GlcA | Anti-inflammatory activity | [96] | Anti-inflammatory |

| Porphyridium cruentum | Glc and carboxylic acid compounds | Immune response against vibriosis | [97] | Antibacterial (preservative) |

| Tetraselmis suecica | Glc (23–37%), GlcA (20–25%), Man (2–36%), Gal (3–25%) and galactoryranoside (5–27%), GalA, (0.1–3%), Ara (5%), Xyl (0.3–3%) and Rib, Rha and Fuc (1%) | Antioxidant | [98] | Antioxidant |

| Porphyridium sordidum | Gal (~40%), Xyl (~30%) and Glu (~30%) | Plant antifungal activity | [99] | Antifungal (preservative) |

| Nostoc sp | α-Rib, α-Glc, α-LAra, α-Xyl, α-LRha, β-Man, β-Gal, GalA, and β-LFuc | Fibroblast proliferation and migration | [100] | Wound healing Skin barrier repair |

| Scenedesmus acutus | Octa-saccharides | Antioxidant | [101] | Antioxidant |

|

Chlorella sorokiniana, Chlorella sp., Picochlorum sp |

Sulfated EPS |

Antioxidant |

[80] |

Antioxidant |

| Nostoc cf. linckia | Dominant neutral saccharides, Glu, Gal, Xyl, and Man, and minor amounts of Rha, Fuc, and Ara | Antioxidant | [102] | Antioxidant |

| Gloeocapsa gelatinosa | Man (~22%), Xyl (~9%), Ara (~10%) GalA (~7%), and GlcA (~8%), Rha (~12%), Fuc (~40%) | Free radicals’ scavenger Antioxidant Metal chelating activity |

[103] | Antioxidant Chelating agent |

| Botryococcus braunii | HMW heteropolysaccharides: uronic acid (7.43–8.83%), protein (2.30–4.04%), and sulfate groups (1.52–1.95%). Gal (52.34–54.12%), Glc (34.60–35.53%), Ara (9.41–10.32%), and Fuc (1.80–1.99%) |

Antioxidant | [104] | Antioxidant |

| Porphyridium cruentum (CCALA415) | Neutral monosaccharides: D- and L-Gal, D-Glc, D-Xyl, D-GlcA, and sulfate groups | Anti-inflammatory Antioxidant Enhancement of wound closure |

[23] | Anti-inflammatory Antioxidant Skin barrier repair |

| Porphyridium cruentum, Chrysotila dentata, Pavlova sp., Diacronema ennorea, Glossomastix sp., Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Synechococcus sp. |

P. cruentum EPS: Gal (44%), Xyl (39%), and Glc (14%). C. dentata, Pavlova sp., D. ennorea, P. tricornutum, and Synechococcus sp. EPS: Gal (26–38%) and Ara/Xyl (36%/17%), Rha/Glc (47%/11%), Rha/Ara (33%/17%), Glc/Ara (42%/13%), and Glc/Fuc (38%/ 24%), respectively. Glossomastix sp. EPS Fuc/Rha/ GalA (40%/31%/21%) |

MMP-1 inhibition Stimulation of collagen production in cell lines CDD-1059Sk and CDD-1090Sk |

[105] | Stimulation of skin collagen production (preventing ageing) |

| Auxenochlorella protothecoides | Gal (42.41 %) and Rha (35.29 %) | Inhibition of the inflammatory response in lipopolysaccharide induced RAW264.7 cells | [31] | Anti-inflammatory |

| Halamphora sp | Xyl (40.55%), l-Gal (13.25%), d-Gal (13.00%), Glc (9.95%) and ribitol (9.82%) | Antimicrobial activity | [106] | Antimicrobial (preservative) |

| Glossomastix sp | Rha and Fuc as major monosaccharides and Gal, GalA and GlcA as minor monosaccharides | Anti-settling stabilizers | [71] | Rheological agent |

| Arthrospira maxima | Heteropolymer, with Man, Xyl, and GlcA | Antibacterial activity Antioxidant |

[107] | Antibacterial (preservative) Antioxidant |

| Microalgae or cyanobacteria | EPS preparation and main composition | Application / Potential use | Applicant / Patent number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthrospira spirulina or Spirulina platensis and Spirulina maxima | Sulfated polysaccharide comprising from 2% to 60% by weight, based on the total weight of the polymer, of a rhamnose unit | Cosmetic skin moisturizing product compatible with cutaneous tissues (skin, scalp) Compositions with the appearance of a white or colored compositions in any form, such as ointment, milk, lotion, serum, paste, foam, aerosol or stick |

L’Oréal SA FR2982152A1 |

[118] |

| Several microalgal and Cyanobacteria strains; for example, Chlorella sp., Dunaliella sp., Tetraselmis sp., Anabaena sp, Aphanizomenon sp., Arthrospira sp., Nostoc sp., Isochrysis sp., Phaeodactylum sp., Skeletonema sp., Thalassiosira sp., Nannochloropsis sp., Porphyridium sp., among others | An EPS of wet, non-dialyzed and non-lyophilized origin added at 0.1-10% (wt) to the cream formulation EPS composition not mentioned |

Cosmetic formulation for topical use on human hair, skin, mucous membranes and nails Microalgal EPS as an enhancer of rheology, stability and sensory properties. Base cream for the addition of microalgal extracts as antioxidant, surfactant, emulsifier, emollient emulsifier; preservative and antimicrobials |

Univ Fed Do Parana BR102012004631A2 |

[117] |

| Genus Parachlorella | Isolation and precipitation with an alcohol, ii) drying and forming a film, iii) contacting with water and forming a gel, air drying EPS average size of between 0.1 and 400 microns EPS composition not mentioned |

Skin care compositions for wrinkle reduction and for improving the health and appearance of skin | Solazyme Inc Algenist Brands Inc US9095733B2 |

[110] |

| Parachlorella kessleri, Parachlorella beijerinckii or Chlorella sorokiniana | EPS composition: 15-55 mole percent of rhamnose, 3-30 percent of moles of xylose, 1-25 mole percent of mannose, 1-45 mole percent of galactose, 0.5-10 mole percent of glucose and 0.1-15 mole percent of glucuronic acid | Skin care products to deliver cosmeceutical ingredients such as carotenoids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, moisturizing polysaccharides, superoxide dismutase, etc. | Algenist Holdings Inc ES2718275T3 |

[111] |

| EPS from PUFA-producing microalgae fermentation waste liquid of Schizochytrium sp., or Cryptidnodinium koushii, or Crypthecodinium cohnii SD401, or Nannochloropsis sp |

Disc centrifuge separation, micro-filtration in ceramic membrane, ultrafiltration (30 kDa) to concentrate (50-70% solids), vacuum-drying (moisture 1%). 71-73 % EPS, 9.-11% peptide and protein, 3-4 % monosaccharide content | Formulation EPS as wall material in emulsions of DHA, Tween 80 and gelatin solution protected against oxidation, spray-dried in microcapsules | Qingdao Institute of Bioenergy and Bioprocess Technology of CAS CN108559006A |

[32] |

| Parachlorella, Porphyridium, Chaetoceros, Chlorella, Dunaliella, Isochrysis, Phaeodactylum, Tetraselmis, Botryococcus, Cholorococcum, Hormotilopsis, Neochloris, Ochromonas, Gyrodinium, Ellipsoidion, Rhodella, Gymnodinium, Spirulina, Cochlodinium, Nostoc, Cyanospira, Cyanothece, Tetraselmis, Chlamydomonas, Dysmorphococcus, Anabaena, Palmella, Anacystis, Phormidium, Anabaenopsis, Aphanocapsa, Cylindrotheca, Navicula, Gloeocapsa, Phaeocystis, Leptolyngbya, Symploca, Synechocystis, Stauroneis, and Achnanthes, preferably Parachlorella kessleri. | Isolation of microalgal EPS from the culture medium, drying at 40-180 °C to form a film insoluble in water, homogenizing the film into particles, formulating the particles into a non-aqueous material, oil phase of an oil-in-water emulsion, generating 0.1-50 microns particles EPS composition not mentioned |

Topical personal care products, or by injection into skin or a skin tissue and wrinkle reduction |

TerraVia Holdings Inc EP3398606A1 |

[112] |

| Parachlorella sp | Capsular exopolysaccharide obtained by separating the exopolysaccharide producing microalgal cells from the culture medium, heating the microalgal cells to release the cellular capsule, and removing the insoluble solids to produce an aqueous solution containing the EPS EPS composition not mentioned |

Vehicle for personal care products | KUEHNLE AGROSYSTEMS Inc US20200232003A1 |

[119] |

|

Glossomastix sp, Chrysotila dentata, Pavlova sp, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Synechococcus sp |

New depolymerized exopolysaccharides (30-100 kDa) and method of obtaining consisting on: pretreatment by high pressure (2.7 kbar), freeze-drying, depolymerization by acid hydrolysis onto cationic resins (Amberlityst® 15 DRY) in batch or in continuous mode EPS composition not mentioned |

Product to increase the production of collagen and/or hyaluronic acid, to delay the effects of skin aging | Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique CNRS, Univ. Nantes, La Rochelle Univ., Sorbonne Univ., Univ. Clermont Auvergne, Univ. Rouen Normandie FR2102020 |

[116] |

| Chlorella sp | Precipitation, centrifugation, purification, and freeze-drying 131.79 kDa EPS, mainly comprises xylose, mannose and ribose |

Antioxidant activity (DPPH, hydroxyl, ABTS radicals and superoxide anions) | Xiangtan University CN110818814A |

[22] |

| Cyanobacteria of the genus Synechococcus CCMP 1333, Synechococcus PCC 7002, and Cyanothece Miami BG 043511 | EPS isolation, drying milling to a size of between 400 microns and 0.1 microns to prepare exopolysaccharide particles; and annealing the EPS particles EPS composition not mentioned |

Topical personal care products, cosmetics for improving the health and appearance of skin, and wrinkle reduction composition | Heliobiosys, Inc. US20240358628A1 |

[113] |

| Cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis | Enhancer of rheology, stability and sensory properties and antioxidant EPS freeze-dried or wet, dialyzed or non-dialyzed 0.1-10% (wt) of the cream formulation EPS composition not mentioned |

Novel products with antioxidant, antiaging, healing, oil-reducing, antiacne, rheological and sensory properties | Univ Fed Do Parana BRPI1004637A2 |

[120] |

| Cell wall-less microalgal strain Chlorophyceae class or Volvocales order, Chlamydomonadaceae family, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii |

Concentration by lyophilization or by tangential flow filtration IMAC-enriched microalgal culture supernatant comprises between 1 μg/L and 0.1 g/L of protein and between 0.001 mg/L and 10 g/L of carbohydrates |

Cosmetic or cosmeceutical composition for wound healing or skin damage repair, increased proliferation of fibroblasts for the treatment of skin aging, photoaging and cutaneous senescence | Greenaltech, S.L Gat Biosciencies SL US12268772B2 |

[115] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).