Submitted:

10 May 2023

Posted:

10 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Growth Rate Inhibition and Cell Size Changes

2.2. Cellular Response Evaluation

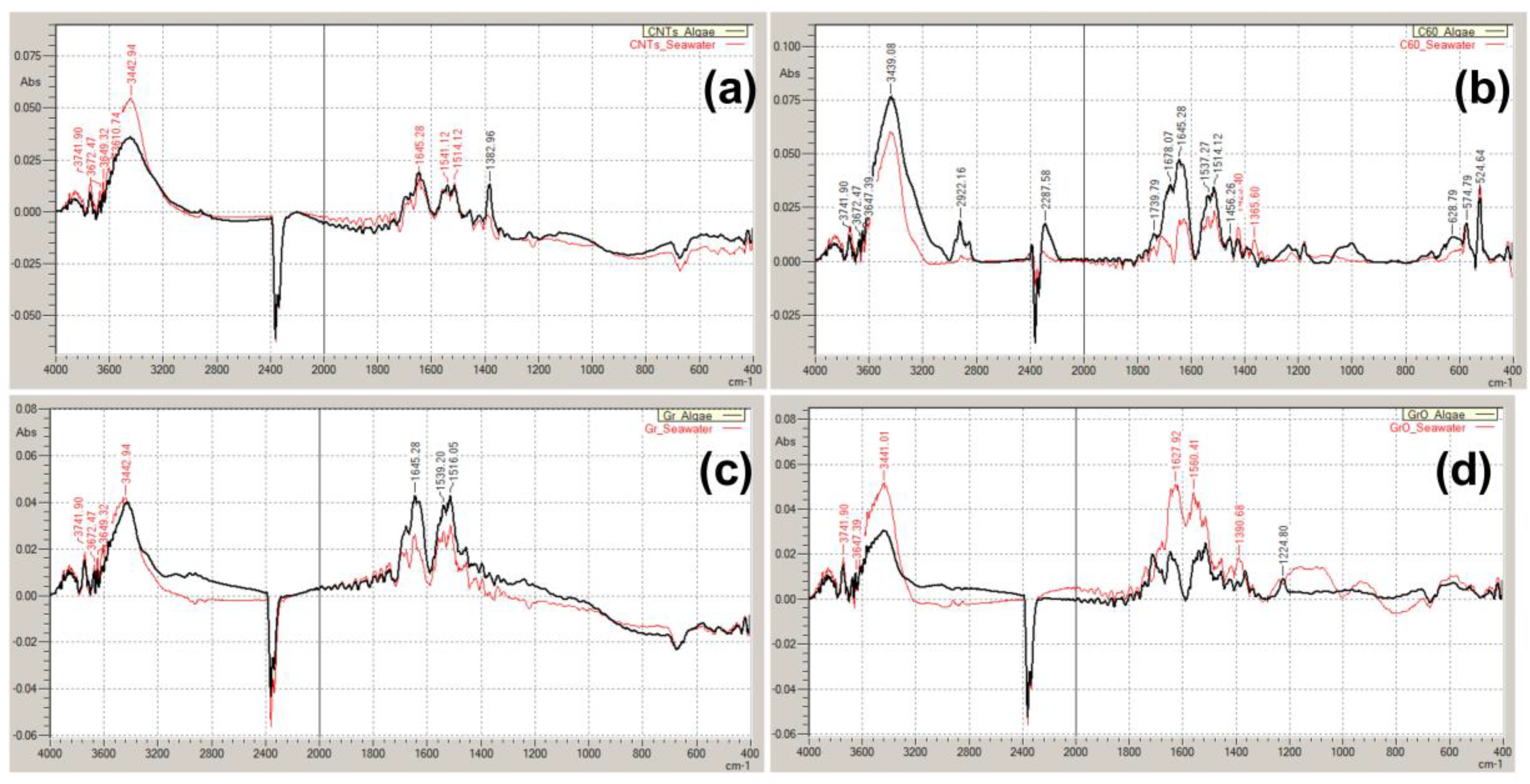

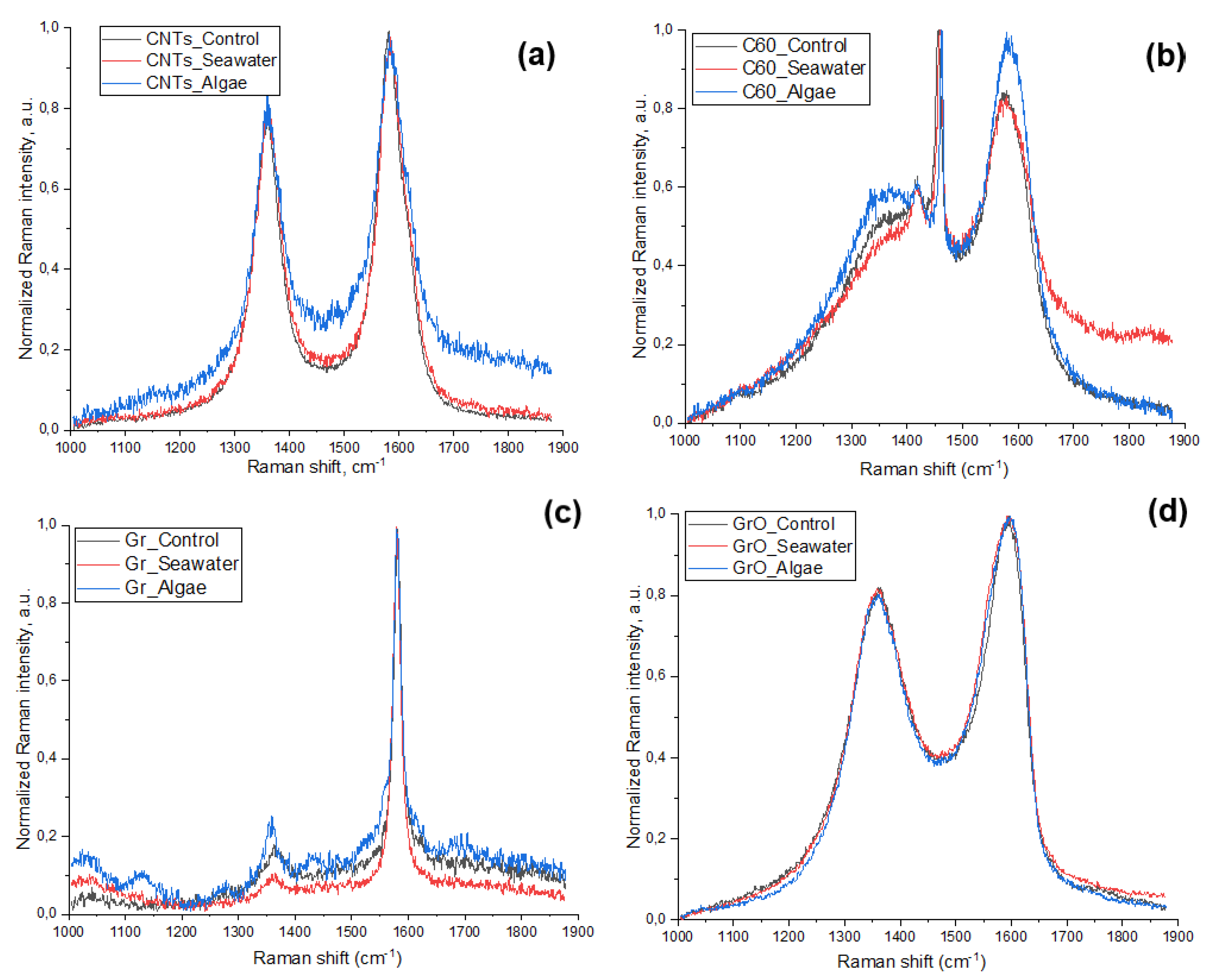

2.3. Particle Biotransformation Assessment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Nanoparticles

4.2. Microalgae Culture

4.3. Experimental Desigh and Sample Preparation

4.4. Flow Cytometry: Cell Count, Staining Protocols, and Post Processing

4.5. Microscopy

4.6. FTIR and Raman spectroscopy

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jordan, C.C.; Kaiser, I.; Moore, V.C. 2013 nanotechnology patent literature review: Graphitic carbon-based nanotechnology and energy applications are on the rise. Nanotech. L. & Bus. 2014, 11, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, S.K.; Srivastava, R. Drug delivery with carbon-based nanomaterials as versatile nanocarriers: progress and prospects. Frontiers in Nanotechnology 2021, 3, 644564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-N. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials for Energy Conversion and Storage: Applications in Electrochemical Catalysis; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 325. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R.; Militky, J. Nanotechnology in textiles: theory and application; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; et al. Production, structural design, functional control, and broad applications of carbon nanofiber-based nanomaterials: A comprehensive review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 402, 126189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, D.; et al. Carbon-based nanomaterials for biomedical applications: a recent study. Frontiers in pharmacology 2019, 9, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; et al. Applications of carbon-based conductive nanomaterials in biosensors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 136183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makvandi, P.; et al. Biofabricated nanostructures and their composites in regenerative medicine. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2020, 3, 6210–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; et al. Carbon-based nanomaterials for bone and cartilage regeneration: a review. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2021, 7, 4718–4735. [Google Scholar]

- Yogeswari, B.; et al. Role of carbon-based nanomaterials in enhancing the performance of energy storage devices: Design small and store big. Journal of Nanomaterials 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.-y.; et al. Design and synthesis of carbon-based nanomaterials for electrochemical energy storage. New Carbon Materials 2022, 37, 59–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; et al. Recent advances in MOF-derived carbon-based nanomaterials for environmental applications in adsorption and catalytic degradation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 427, 131503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.C.; Rodrigues, D.F. Carbon-based nanomaterials for removal of chemical and biological contaminants from water: A review of mechanisms and applications. Carbon 2015, 91, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.E.; et al. Recovery of rare earth elements by carbon-based nanomaterials—a review. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftekhar, S.; et al. Porous materials for the recovery of rare earth elements, platinum group metals, and other valuable metals: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022, 20, 3697–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotia, A.; et al. Carbon nanoparticles as sources for a cost-effective water purification method: A comprehensive review. Fluids 2020, 5, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madima, N.; et al. Carbon-based nanomaterials for remediation of organic and inorganic pollutants from wastewater. A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2020, 18, 1169–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; et al. Heavy metal removal from aqueous solution by advanced carbon nanotubes: critical review of adsorption applications. Separation and Purification Technology 2016, 157, 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shojaei, T.R.; et al. Applications of nanotechnology and carbon nanoparticles in agriculture, in Synthesis, technology and applications of carbon nanomaterials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 247–277. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.; et al. Toxicity studies on graphene-based nanomaterials in aquatic organisms: Current understanding. Molecules 2020, 25, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, N.B.; et al. Nanoparticles in the aquatic environment: Usage, properties, transformation and toxicity-A review. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2019, 130, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Gupta, S.M.; Sharma, S. Carbon nanotubes: Synthesis, properties and engineering applications. Carbon Letters 2019, 29, 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; LGao; Sun, J. Production of aqueous colloidal dispersions of carbon nanotubes. Journal of colloid and interface science 2003, 260, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, B.; Kumar, R. Structure, properties and applications of fullerenes. International Journal of Nanotechnology and Applications 2008, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alargova, R.G.; Deguchi, S.; Tsujii, K. Stable colloidal dispersions of fullerenes in polar organic solvents. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2001, 123, 10460–10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, Q. Ambient water and visible-light irradiation drive changes in graphene morphology, structure, surface chemistry, aggregation, and toxicity. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49, 3410–3418. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; et al. Colloidal properties and stability of aqueous suspensions of few-layer graphene: Importance of graphene concentration. Environmental Pollution 2017, 220, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, Y.; Chihara, M. MORPHOLOGY, ULTRASTRUCTURE AND TAXONOMY OF THE RAPHIDOPHYCEAN ALGA HETEROSIGMA-AKASHIWO. Botanical Magazine-Tokyo 1987, 100, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţucureanu, V.; Matei, A.; Avram, A.M. FTIR spectroscopy for carbon family study. Critical reviews in analytical chemistry 2016, 46, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baykal, A.; et al. Acid functionalized multiwall carbon nanotube/magnetite (MWCNT)-COOH/Fe 3 O 4 hybrid: synthesis, characterization and conductivity evaluation. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials 2013, 23, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Pan, C. Enhanced electrochemical capacitance of nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes synthesized from amine flames. Soft Nanosci. Lett 2011, 1, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indeglia, P.A.; et al. Physicochemical characterization of fullerenol and fullerenol synthesis by-products prepared in alkaline media. Journal of nanoparticle research 2014, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, R.; Bag, D.S.; Nigam, I. Synthesis and evaluation of swelling characteristics of fullerene (C60) containing cross-linked poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) hydrogels. Advanced Materials Letters 2014, 5, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, M.; Richter, E.; Subbaswamy, K. Structural and vibrational properties of fullerenes and nanotubes in a nonorthogonal tight-binding scheme. The Journal of chemical physics 1996, 104, 5875–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Groth, S.; Cataldo, F.; Manchado, A. Infrared spectroscopy and integrated molar absorptivity of C60 and C70 fullerenes at extreme temperatures. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2011, 413, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obreja, A.C.; et al. Isocyanate functionalized graphene/P3HT based nanocomposites. Applied Surface Science 2013, 276, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykkam, S.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of graphene oxide and its antimicrobial activity against klebseilla and staphylococus. International Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Research 2013, 4, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, Y.-y.; et al. Flexible free-standing graphene-like film electrode for supercapacitors by electrophoretic deposition and electrochemical reduction. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2014, 24, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardol, P.; Forti, G.; Finazzi, G. Regulation of electron transport in microalgae. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics 2011, 1807, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.X.T.; et al. Toxicity of metals and metallic nanoparticles on nutritional properties of microalgae. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2020, 231, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, V.C.; et al. Biological interactions of graphene-family nanomaterials: an interdisciplinary review. Chemical research in toxicology 2012, 25, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardo, T.; et al. Determination of elemental distribution in green micro-algae using synchrotron radiation nano X-ray fluorescence (SR-nXRF) and electron microscopy techniques–subcellular localization and quantitative imaging of silver and cobalt uptake by Coccomyxa actinabiotis. Metallomics 2014, 6, 316–329. [Google Scholar]

- Ameri, M.; et al. Aluminium triggers oxidative stress and antioxidant response in the microalgae Scenedesmus sp. Journal of plant physiology 2020, 246, 153114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenfield, M.A.; et al. Aluminium, gallium, and molybdenum toxicity to the tropical marine microalga Isochrysis galbana. Environmental toxicology and chemistry 2015, 34, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Humic acid alleviates the ecotoxicity of graphene-family materials on the freshwater microalgae Scenedesmus obliquus. Chemosphere 2018, 197, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazeem, L.J.; et al. Toxicity effect of graphene oxide on growth and photosynthetic pigment of the marine alga Picochlorum sp. during different growth stages. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 4144–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Z.F.; et al. Systematic and Quantitative Investigation of the Mechanism of Carbon Nanotubes' Toxicity toward Algae. Environmental Science & Technology 2012, 46, 8458–8466. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; et al. Interactions between graphene oxide and plant cells: Regulation of cell morphology, uptake, organelle damage, oxidative effects and metabolic disorders. Carbon 2014, 80, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, F.; et al. Are Carbon Nanotube Effects on Green Algae Caused by Shading and Agglomeration? Environmental Science & Technology 2011, 45, 6136–6144. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Spivack, A.J. Menden-Deuer, S. pH alters the swimming behaviors of the raphidophyte Heterosigma akashiwo: implications for bloom formation in an acidified ocean. Harmful Algae 2013, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouara, A.; et al. Carboxylic acid functionalization prevents the translocation of multi-walled carbon nanotubes at predicted environmentally relevant concentrations into targeted organs of nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 6088–6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, R.B.; et al. Detection of single walled carbon nanotubes by monitoring embedded metals. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts 2013, 15, 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Pikula, K.; Johari, S.A.; Golokhvast, K. Colloidal Behavior and Biodegradation of Engineered Carbon-Based Nanomaterials in Aquatic Environment. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, M.; et al. Protein bio-corona: critical issue in immune nanotoxicology. Archives of toxicology 2017, 91, 1031–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikula, K.; et al. Individual and Binary Mixture Toxicity of Five Nanoparticles in Marine Microalga Heterosigma akashiwo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; et al. Is hydrodynamic diameter the decisive factor?-Comparison of the toxic mechanism of nSiO2 and mPS on marine microalgae Heterosigma akashiwo. Aquatic Toxicology 2022, 252, 106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; et al. Microplastics impacts in seven flagellate microalgae: Role of size and cell wall. Environmental Research 2022, 206, 112598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matcher, G.; Lemley, D.A.; Adams, J.B. Bacterial community dynamics during a harmful algal bloom of Heterosigma akashiwo. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 2021, 86, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD, Test No. 201: Freshwater Alga and Cyanobacteria, Growth Inhibition Test. 2011.

- Guillard, R.R.; Ryther, J.H. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (cleve) Gran. Canadian journal of microbiology 1962, 8, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouhan, R.S.; et al. Nanomaterial resistant microorganism mediated reduction of graphene oxide. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2016, 146, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikula, K.S.; et al. Toxicity assessment of particulate matter emitted from different types of vehicles on marine microalgae. Environmental Research 2019, 179, 108785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, L.C.; et al. Measuring cell death by propidium iodide uptake and flow cytometry. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols 2016, 2016, pdb. prot087163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; et al. DNA staining for fluorescence and laser confocal microscopy. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 1997, 45, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; et al. Microalgal microscale model for microalgal growth inhibition evaluation of marine natural products. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; et al. Toxic effects of microplastic on marine microalgae Skeletonema costatum: interactions between microplastic and algae. Environmental pollution 2017, 220, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; et al. Evaluating the effects of allelochemical ferulic acid on Microcystis aeruginosa by pulse-amplitude-modulated (PAM) fluorometry and flow cytometry. Chemosphere 2016, 147, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabnis, R.W.; et al. DiOC(6)(3): a useful dye for staining the endoplasmic reticulum. Biotechnic & Histochemistry 1997, 72, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Grégori, G.; et al. A flow cytometric approach to assess phytoplankton respiration, in Advanced Flow Cytometry: Applications in Biological Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Baruah, P.; Chaurasia, N. Ecotoxicological effects of alpha-cypermethrin on freshwater alga Chlorella sp.: Growth inhibition and oxidative stress studies. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2020, 76, 103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, N.M.; et al. Development of an improved rapid enzyme inhibition bioassay with marine and freshwater microalgae using flow cytometry. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2001, 40, 469–480. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, N.M.; Stauber, J.L.; Lim, R.P. Development of flow cytometry-based algal bioassays for assessing toxicity of copper in natural waters. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry: An International Journal 2001, 20, 160–170. [Google Scholar]

| Duration of exposure | Toxicity descriptor | CNTs, mg/L | C60, mg/L | Gr, mg/L | GrO, mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth rate inhibition | |||||

| 96 h | NOEL | 1 | 25 | 5 | 5 |

| EC10 | 1.52 (0.99–2.25) | 34.57 (9.54–63.90) | 13.80 (8.52–20.51) | 8.22 (4.84–12.90) | |

| EC50 | 18.98 (15.92–22.49) | 414.0 (218.10–1431) | 159.40 (137.10–192.60) | 76.77 (66.82–87.68) | |

| 7 days | NOEL | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EC10 | 1.37 (0.98–1.89) | n/a | n/a | 34.39 (24.69–44.08) | |

| EC50 | 13.41 (11.52–15.53) | n/a | n/a | 118.0 (109.30–129.10) | |

| Cell size change | |||||

| 96 h | NOEL | 10 | 10 | 25 | 25 |

| 7 days | NOEL | 50 | 25 | 25 | 10 |

| Endpoint | Duration of exposure | CNTs, mg/L | C60, mg/L | Gr, mg/L | GrO, mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esterase activity change | 3 h | 25 | 25 | 50 | 25 |

| 24 h | 50 | 25 | 50 | 50 | |

| Membrane potential change | 3 h | <1 | 50 | 10 | 10 |

| 24 h | <1 | 50 | 50 | 25 | |

| ROS generation change | 3 h | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 |

| 24 h | 25 | 10 | 50 | 10 |

| Sample | Size | Purity | Synthesis or manufacturer information |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNTs | Diameter: 6-13 nm; Length: 2.5-20 µm |

> 98% (main trace metals: Al - 10000 ppm, Co – 2652 ppm) | Batch Number: MKCM1457; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| C60 | Diameter: 0.8 nm | > 95.5% (oxide C60) | Batch Number: 120722; Modern Synthesis Technology (MST), Saint-Petersburg, Russia |

| Gr | Thickness: 3-10 nm; Diameter: 0.5-10 µm |

> 99% | Type #1, CAS#: 1034343-98-0; Modern Synthesis Technology (MST), Saint-Petersburg, Russia |

| GrO | Diameter:10-100 µm | Carbon: 46%; Oxygen: 49%; Hydrogen: 2,5%; Sulfur: 2,5% | CAS#: 1034343-98-0; Modern Synthesis Technology (MST), Saint-Petersburg, Russia |

| Endpoint | Fluorescent Dye or Registered Parameter | Duration of microalgae exposure before the measurement | Dye concentration / Duration of Staining | Emission Channel / Band Width, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth rate inhibition | PI | 96 h, 7 days | 15 µM/20 min | 610/20 |

| Cell size change | Forward scatter intensity (size calibration kit F13838 by Molecular Probes, USA) | 96 h, 7 days | – | FSC |

| Esterase activity change | FDA | 3, 24 h | 50 µM/20 min | 525/40 |

| Membrane potential change | DiOC6 | 3, 24 h | 0.5 µM/20 min | 525/40 |

| ROS generation change | H2DCFDA | 3, 24 h | 50 µM/30 min | 525/40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).