Introduction

Silver nanoparticles (nAg) are on of the most used nanomaterial in our economy because of their various properties of commercial interest (Gottardo et al., 2021; McGillicuddy et al, 2017). They are used in electrical appliances (washing machines), paints, cosmetics, deodorants/soap, plastic food packaging and clothes because of their antifouling biocidal properties (Walters et al. 2014). It is estimated that the production of nAg is between 450-500 tons per year (Zhang et al., 2016), which can ultimately contaminate the environment (Bolaños-Benítez et al., 2020). The ever-increasing marketing of nAg containing materials will likely result in the development of more complex nano-device or nanomaterials. Recently nAg was attached to carbon walled nanofibers (nAg-CWNT) producing more complex nanomaterials with perhaps inadvertent emergent toxic properties that may not be entirely explained but their individual components. NAg-CWNT composites are currently used to improve electrical conductivity, enhance tensile strength, hardness and elastic properties of materials for various commercial applications. For example, they are used in electric motors, sensing devices, tear-resistant clothes and armor. They introduce semi-conductor or conductive films in coatings, plastics, flat screen displays and electromagnetic wave shielding and lithium battery anodes. These novel applications of nAg-CWNT composites contribute to the increased contamination of aquatic and soil ecosystems through solid waste disposal sites and municipal/industrial wastewaters.

Hydra vulgaris Pallas, 1766 has been used as a model organism for medical and environmental studies since the 1950’s (Fatima et al., 2024; Vimalkumar et al., 2022; Cera et al., 2020). Hydra is the equivalent of anemones family (Cnidaria phylum) in freshwater. It is a simple organism composed of tubular body for digestion and reproduction and a head (mouth) equipped with 7 tentacles (

Figure S1). The size of hydra is between 2-10 mm long with the base usually attached to a solid substrate (branches, stones and vegetation) and the tentacles for catching and immobilization of prey for nourishment. Their food consists of small microcrustaceans such as water flea and copepods. The hydra is usually unisexual although some species are hermaphrodites. This organism has remarkable regenerative abilities continuing to grow and reproduce without significant aging making a convenient model for regenerative studies for the medical community. Hydra reproduces by budding forming polyps producing offsprings throughout its life with doubling time every 4-5 days depending on media composition, temperature and feeding regime (Ghaskadbi 2020). The sublethal and lethal toxicity of various environmental pollutants, drugs and effluents manifests by characteristic and successive changes in morphology as the severity (irreversible) of effects increases: tentacle retraction and budding (reversible), loss of tentacles (reversible), contraction of tubular body (tulip) and desintegration (

Figure S1). The formation of tulip and desintegration stages are considered lethal and irreversible while the first manifestations are reversible. Because of the small size of Hydra (2-10 mm), sublethal effects investigations at the molecular level are more difficult in environmental toxicological investigations. Quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRTPCR) is a well established highly sensitive and specific methodology to quantitative the levels of mRNA transcripts for the early molecular effects of xenobiotics. In the attempt to refine this bioassay to investigate the mode of action of chemicals and mixtures, a qRTPCR methodology was developed to target key physiological targets for nanomaterials (ref) such as oxidative stress (superoxide dismutase and catalase), protein synthesis (elongation factor 1), protein salvage and autophagy (ubiquitin-proteosome salvage pathway, regeneration and growth (serum response factor 1), and oxidized DNA repair (8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylases) (

Table 1). Indeed, nanomaterials were found to increase protein damage leading to ubiquitinoylation for the proteasome salvage pathway and autophagy in fish and mussels (Auclair et al. 2023, 2021). These effects were seemingly specific to nanomaterials since the dissolved fraction of nAg (dissolved Ag) did not produced these effects within the concentration range tested. The development of rapid and sensitive biomarkers at the gene expression should provide a more detailed understanding of the nanoecotoxicity of complex nanomaterials such as nAg-CWNT that precedes changes in morphology in hydra.

The purpose of this study was therefore to examine the toxicity of nAg-CWNT composites in Hydra vulgaris at both the morphological and gene expression levels. Gene expression was analyzed using the very sensitive and quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase gene expression methodology. Moreover, the toxicity of 2 composites differing in Ag contents (10 and 50% nAg on the CWNT fibers) were examined and compared with nAg and CWNT alone in the attempt to highlight novel emergent toxicity properties in more complex nanomaterials/composites. The null hypothesis statement is that the toxicity of nAg-CWNT composites could be explained by the levels of nAg or CWNT alone.

Table 2.

Physico-chemical characteristics of the nanosilver composites.

Methods

Sample Preparation

The nanocomposites of silver and carbon nanotubes, CWNT and nAg were purchased at US Research Nanomaterials (Houston, TX, USA). The CWNT were composed of graphene oxide multiwalled (5-10 nm inside and 55 nm outside diameter) between 10-30 um long. The citrate coated nAg was spheric with 20 nm diameter. The nAg-CWNT composites consisted of 10 % nAg-90% CWNT and 50% nAg-50% CWNT by weight. The samples were purchased as 3% water dispersion and diluted to 1 mg/mL in 1 mM CaCl2 containing 0.4 mM tris aminoethane sulfonate (TES) buffer pH 7.4 (hydra medium). These samples were prepared for transmission electronic microscopy analysis using an image software (Image J) and energy X-ray dispersive spectroscopy (Electron microscopy service laboratory, Polytechnic Institute, Montreal University).

Hydra Toxicity Assessments

The assays were performed using standardized methodology for the cnidarian

Hydra vulgaris and attenuata (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020; Blaise and Kusui, 1997). The hydra were cultivated in crystallization bowls containing 200 ml of the hydra media. They were fed with fresh suspensions of Artemia salina each day as previously described giving a doubling time of 4-5 days. For the exposure step, adult hydra (3 individuals per 4 mL in 24 well microplates in triplicates) were plated in the hydra medium. They were exposed for 96 h at 20

oC to increasing concentrations of two nAg-CWNT composites as 0, 1.56, 3, 6, 12, 25, 50 and 100 ug/L as total Ag added corresponding to 1.56 to 100 ug/L of CWNT for the 50% nAg-CWNT composite and to 14-900 ug/L CWNT for the 10% nAg-90% CWNT composite. For nAg, the hydra were exposed to same concentration range of Ag for the nanocomposites and for CWNT to 27, 56, 112, 225 and 450 ug/L. No signs of precipitation were observed visually for the CWNT and using the reported absorption at 480 nm for nAg and nAg-CWNT composite (Selvam et al., 2023). Following 96-h exposure, the lethal and sublethal concentrations were determined using a 4-6 X stereomicroscopes. The 96h hydra bioassay determines the lethal (the lethal concentration that kills 50% of the hydra-LC50) based on severe morphological changes such as loss of antenna/tentacles and severe contraction of the tube-like body reminescent of a tulip flower (

Figure S1). These changes are considered irreversible since the organisms do not recuperate and lead to mortality. The sublethal toxicity determines the effect concentration where 50 % of the hydra (EC50) exhibit the following reversible morphological changes: tentacle shortening with bud formation at the head (

Figure S1). The hydra was not fed during the exposure concentration. Given that the exposure time encompasses the reproduction period (appearance and release of polyps) of 4-5 days, this assay could be considered chronic. The surviving hydra (with no morphological alterations) were resuspended in RNAlater solution and stored at -20

oC until gene expression analysis as described below.

Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from N=6 hydra using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, On, Canada). RNA concentration and purity were assessed at 260 and 280 nm with the NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ON, Canada), and RNA integrity was verified using the TapeStation 4150 system (Agilent) with the Agilent RNA ScreenTape Instrument (cat # 5067-5576, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, USA). Reverse transcription was performed with the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen), ensuring the complete removal of genomic DNA, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting cDNA samples were stored at -80 °C for quantitative real-time RTPCR analysis.

All qPCR determinations used the following commercial kit SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). For each selected primer pair (

Table 1), a calibration curve (starting cDNA concentration: 10 ng, 8 serial dilutions) was generated, with PCR efficiency values ranging between 95% and 115%, and the limit of quantification was determined. Each reaction was run in duplicate and consisted of 5 µL cDNA, 6.5 µL of 2× SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad), 300 nM of each primer, and DEPC-treated water (Ambion) up to a total volume of 13 µL. Cycling parameters were as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 10 s for HPRT, RPLPO, EF1, DDC1, SRF, and OGG; 95 °C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 56 °C for 10 s for CAT and MANF; and 95 °C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 56 °C for 30 s for MAPCI3. Two housekeeping genes were used for normalization (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) with the following genes: hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) and 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0-like RPLPO. Amplification specificity was verified using a melting curve profile analysis. A no-template control (NTC) was included on each plate. Gene expression analysis was performed using CFX Maestro (Bio-Rad).

Data Analysis

The 96h LC50 and EC50 obtained from each the bioassay in hydra, were determined using the Spearman-Karber method (Finney, 1964). Toxicogenomic data were normalized against control Hydra and were reported as effect thresholds (ET) as defined: threshold = (no effect concentration x lowest significant effect concentration)1/2 in µg/L. The gene expression data were submitted to an analysis of variance following Levene’s test for normality and variance homogeneity. Critical difference from the controls was determined using the Fisher Least Square difference test. Relationships between toxicity (LC50 and EC50) and gene expression data (ET) were determined using the Pearson moment correlation test. The biomarker data were also analyzed by hierarchical tree to determine similarity of effects between the nanocomposites, nAg and CWNT using the squared correlation coefficient (1-r2) as the metric distance. Discriminant function analysis was also determined to identify key gene expression changes describing best discriminated the 2 nAg-CWNT composite, nAg, CWNT and control hydra. Significance was set at p < 0.05. All the statistical analyses were conducted using SYSTAT (version 13.2, USA).

Results

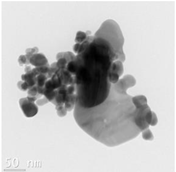

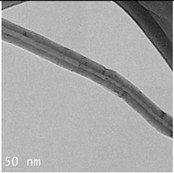

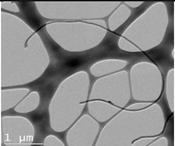

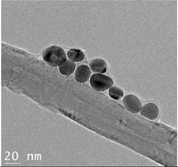

The CWNT, nAg and their composites were examined by TEM analysis (

Table 1). Citrate coated nAg and CWNT were included as a proxi for the nAg-CWNT composites at the same supplier. In the Hydra medium, nAg is mostly found in aggregated form with some evidence of coalescence. The aggregates were relatively stable of water since the total measured levels corresponded to 80-105 % of the nominal concentration in aquarium water based on spectrometric analysis of 1 mg/L stock solution after one hour. This suggests that Hydra were mostly exposed to the particulate form of nAg in this study. For the carbon walled nanotube (CWNT), 10-30 µm long fibers were generally well dispersed (not aggregated) with an inside diameter of circa 8-10 nm and outside diameter of 50-60 nm for the multiwall or carbon sheets. The CWNT suspensions were surprisingly stable as no evidence of precipitation was found over one week at 20

oC. For the 10%nAg-90%CWNT composite, nAg was attached at the surface to the CWNT as monomers covered with a thin carbon film. Non-attached nAg was also found and were mostly in aggregated state as with citrate coated nAg. For the 50% nAg-50%CWNT, the same pattern was observed. Based on image analysis, it was estimated that 30-40 % of nAg was attached to the carbon fibers with the rest present as nAg aggregates.

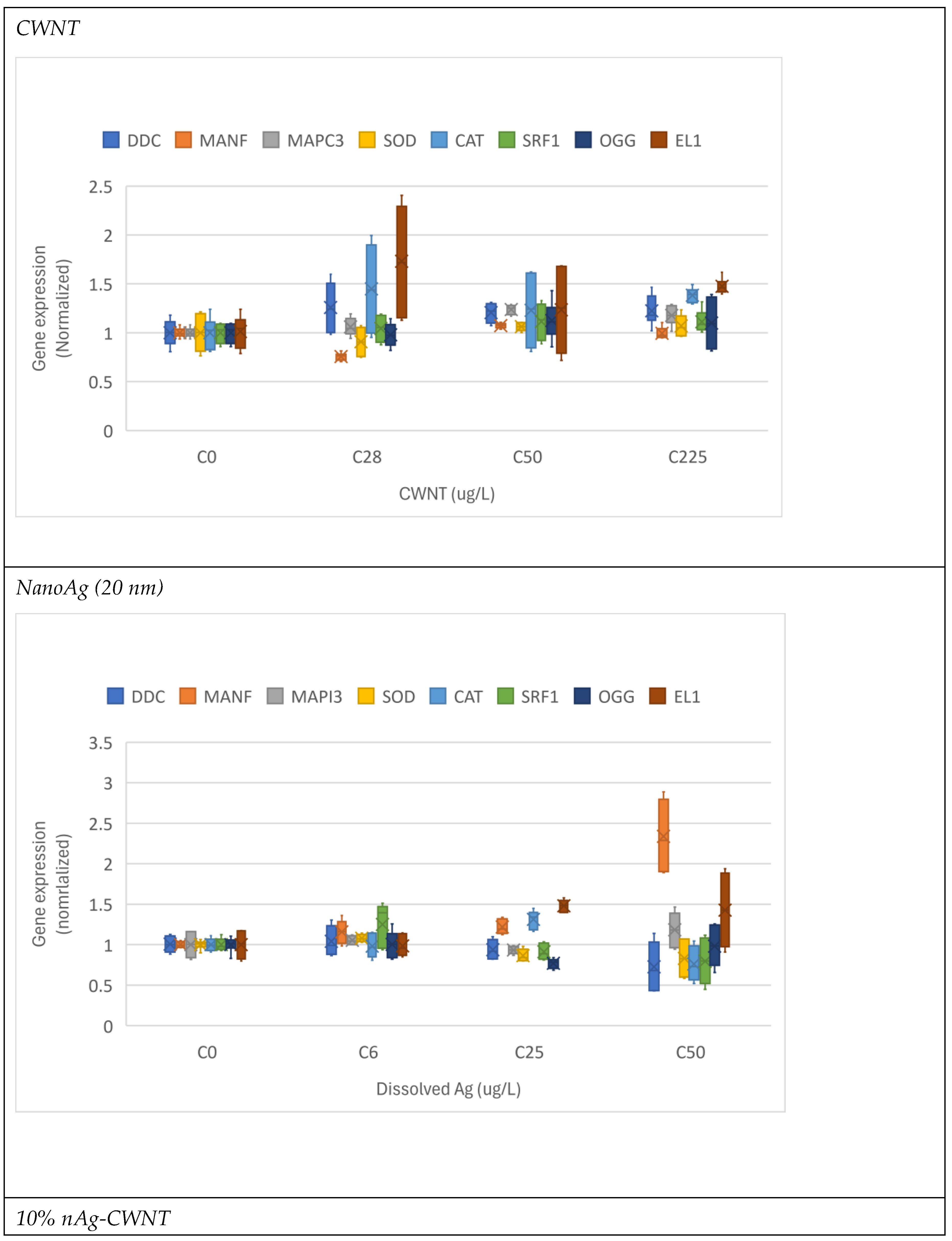

The toxicity and changes in gene expression were determined in hydra for the various states of nAg and CWNT (

Figure 1). For CWNT, the exposure concentration ranged from 28 to 225 µg/L with no appearance of any signs of toxicity based on morphological changes (Table 3). Exposure to CWNT generally increased gene expression with the exception of MANF showing non-monotonic decrease gene expression at the lowest exposure concentration (28 µg/L) and their levels returned to control levels for the higher concentrations (50-225 µg/L). Most genes were significantly increased at a threshold concentration of 105 µg/L with the exception of MANF as explained above SOD and SRF1. For citrate-coated nAg, only sublethal effects (EC50) based on reversible morphological changes were obtained with a EC50=9 µg/L. The following genes were increased by this form of silver at threshold concentration of 12 µg/L: MANF, CAT and EL1. SOD and OGG gene expression were significantly suppressed at this threshold while no effect on SRF1 gene expression. For the 10% nAg-90% CWNT composite, the lethal (LC50) and sublethal toxicity (EC50) was at 320 and EC50 8.2 µg/L as Ag (or 2600 and 74 µg/L as CWNT). DDC, CAT transcripts (mRNA) were significantly induced at a threshold concentration of 8.5 µg/L Ag (76.5 µg/L as CWNT) while EL1 was induced at threshold concentration of 4.2 µg/L Ag (or 38 µg/L CWNT). Decreased gene expression was found for MANF (4.2 µg/L as Ag or 38 µg/L as CWNT), MAPC3l (4 µg/L as Ag), OGG (4.2 µg/L as Ag) and SOD (8.5 µg/L as Ag). SRF1 transcript levels were significantly decreased at 3 µg/L only after covariance analysis with either CAT or EL1 gene expression as the covariate. For the 10% nAg-90% CWNT composite, DDC was significantly correlated with CAT (r=0.83), SRF1 (r=0.71) and EL1 (r=0.67). SOD gene expression was correlated with OGG (r=0.74) and MANF (r=0.60). CAT transcript levels were significantly correlated with EL1 (r=0.62). EL1 transcripts were correlated with MANF (r=-0.51) and SRF1 (r=0.49).

Table 3.

Toxicity and gene expression changes.

Table 3.

Toxicity and gene expression changes.

| Éléments |

CWNT

(µg/L)

|

nAg

(µg/L)

|

10% nAg-90%CNT

(Ag;CNT µg/L)

|

50 % nAg-50%CNT

(µg/L)

|

| DDC |

<28(+) |

35(-) |

ND |

<3 (-) |

| MANF |

<28(-) |

35(+) |

8.5;76.5(-) |

8.5(+) |

| MAPCI3 |

37(+) |

35(-) |

4.2;38 (-) |

<3(-) |

| SOD |

ND |

35(-) |

8.5;76.5(-) |

ND |

| CAT |

<28(+) |

12(+) |

ND |

<3(-) |

| SRF1 |

ND |

ND |

<3(-) |

8.5 (-) |

| OGG |

ND |

12(-) |

ND |

8.5(-) |

| EL1 |

<28(+) |

12(+) |

4.2;38(+) |

4.2(+) |

Hydra

LC50

EC50

|

>450

>450

|

>100

9(6-13)2

|

321(22-41)

8.2(7-9.5)

|

78(67-92)

8.5(5.7-12.6)

|

| # genes affected |

5/8 |

7/8 |

4/8 |

6/8 |

For the 50% nAg-50% CWNT composite, the lethal (LC50) and sublethal (EC50) were 78 µg/L and 8.5 µg/L as silver (corresponding to the same CWNT concentrations). MANF and EL1 were significantly induced at a threshold concentration of <3 and 85 µg/L as Ag and CWNT respectively. MAPC3l, SOD and OGG were significantly decreased at a threshold concentration of 8.5 ug/L as Ag and CWNT. CAT gene expression was significantly reduced at the lowest exposure concentration of 3 µg/L. SRF1 transcript levels were significantly decreased at 12 µg/L only after covariance analysis with either CAT or EL1 gene expression as the covariate. Correlation analysis revealed DDC gene expression was correlated with EL1 (r=-0.59). SOD gene expression was significantly correlated with MANF (r=0.72), CAT (r=0.87), SRF1 (r=0.77) and EL1 (r=0.74). CAT transcription was significantly correlated with SRF1 (r=0.59), MANF (r=0.7) and EL1 (r=0.73). El1 gene expression was correlated with MANF (r=0.81).

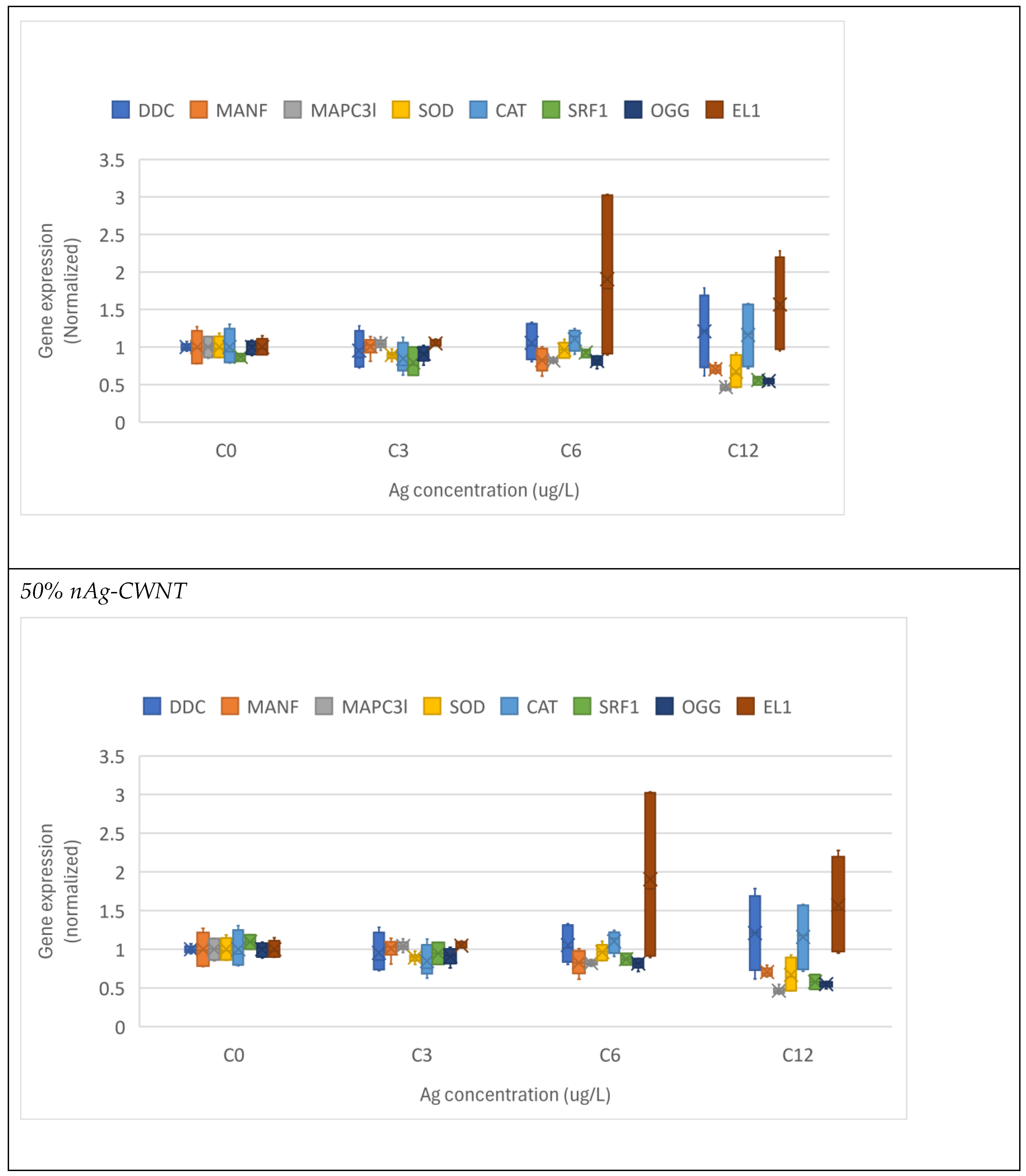

In the attempt to gain a global understanding of the toxic effects of nAg-CWNT composites, an hierarchical and discriminant function analysis was performed. A hierarchical tree analysis was performed between the gene expression thresholds and lethal/sublethal toxicity data (

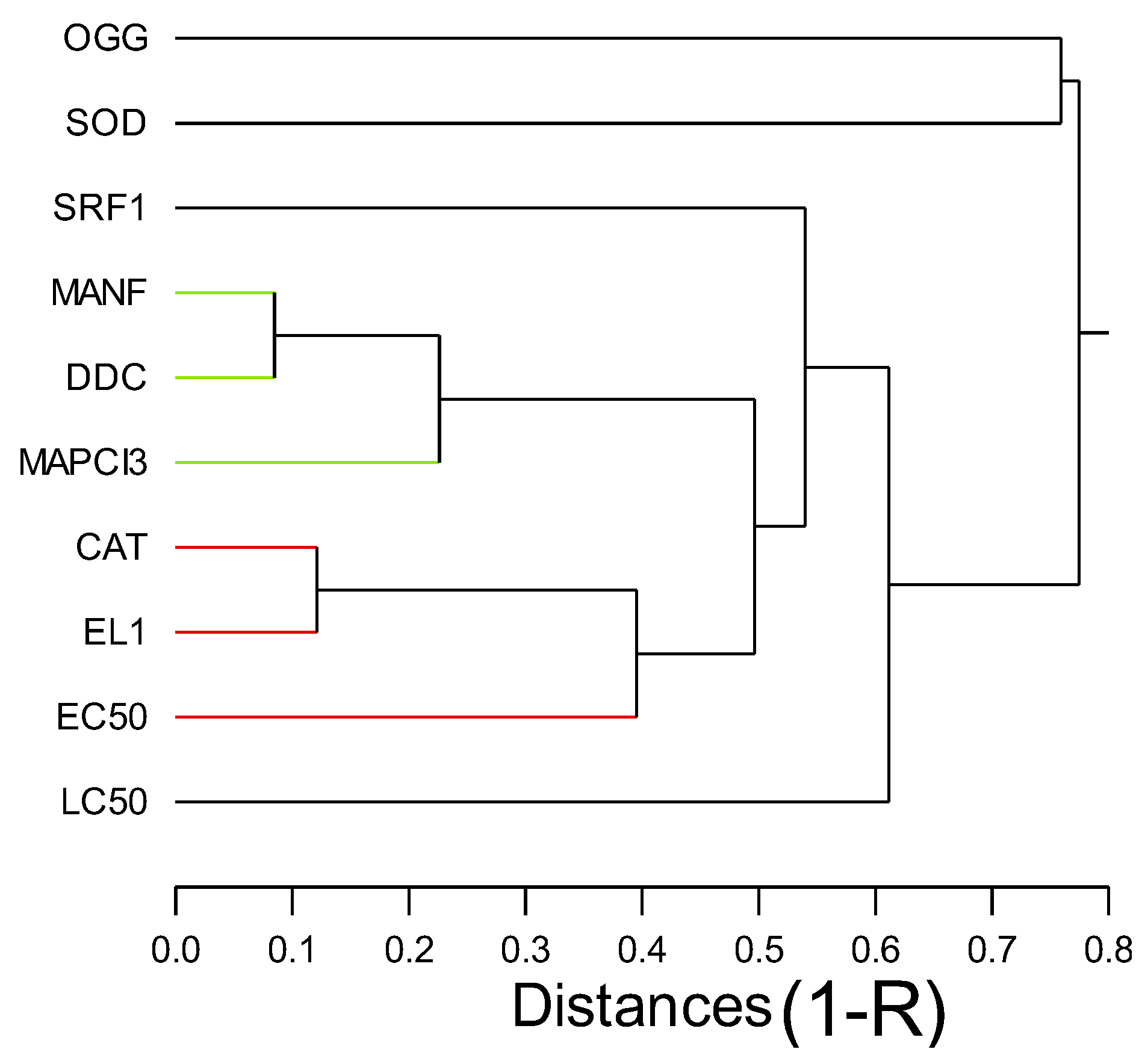

Figure 3). The analysis revealed that the lethal toxicity (LC50) was not related to gene expression changes but the sublethal toxicity (EC50) was significantly related to gene expression changes for CAT and EL1 cluster (i.e. EL1 and CAT were significantly related with each other). Moreover, DDC, MANF, MAPC3l and SOD transcript levels formed a cluster with significant associations with each other but a weaker link with the EC50. The concentration-response data for the 8 genes were examined using discriminant function analysis to determine the similarities in the toxicity responses between CNT, pure nAg and nAg-CWNT composites (Figure 4). The analysis revealed that the effects of pure nAg and CWNT were mostly discriminated by the x axis with following gene expression changes (DDC>SOD>CAT) mainly involved in oxidative stress and neuroactivity (Dopa decarboxylase). For the nAg-CWNT composites, there responses differed from single nAg and CWNT by the 2 component on the y axis with the following gene expression changes (EL1>SOD>SRF1) suggesting changes in protein synthesis activity, oxidative stress and regeneration. Although SRF1 changes were generally decreased by the exposure concentrations, CAT and protein synthesis (EL1) for the 50% nAg-CWNT composite. The same results were also observed for the 10%nAg-CWNT composite suggesting that SRF-1 signaling was not only related to exposure concentration of nAg-CWNT components but to oxidative stress and protein synthesis as well.

Discussion

Based on the LC50, the lethal toxicity of the tested compounds were CNWT (>450 µg/L) ~ nAg (>100 µg/L) < 10% nAg-90%CWNT (321 µg/L)<50% nAg-CWNT(78 µg/L). Moreover the EC50 was more closely related to gene expression changes, revealed that the nAg-CWNT composites were more closely related to changes in gene expression. In a previous study, the LC50 of single walled NT was between 1-10 mg/L corroborating the present findings (Blaise et al., 2008). In another the toxicity of humic acid coated CWNT was not toxic at 10 mg/L in Hydra (Coa et al., 2017). This suggests that the observed toxicity mainly arise for the nAg and nAg-CWNT composites in the present study. In respect to nAg (20 nm diameter), the LC50 and EC50 was >100 and 9 µg/L respectively. The toxicity of larger citrate coated nAg (50 nm), the LC50 and EC50 were respectively 56 and 22 µg/L suggesting some difference albeit at the same order of magnitudes (Auclair and Gagné, 2022). The reported levels of free Ag+ was 4 and 2.6 µg/L for the LC50 and EC50 respectively, which are close to the observed EC50 for the nAg-CWNT composites. The lower toxicity of citrate coated nAg in the present study could be explained by the aggregation state. The sublethal toxicity (EC50) were closely associated to EL1 and CAT gene expression suggesting impacts at the oxidative stress and protein synthesis levels. Changes in gene expression occurred at threshold concentrations sometimes reaching <3 µg/L suggesting that impacts occur before appearance of morphological changes. This was also observed following discriminant function analysis where genes involved in oxidative stress (SOD, CAT), protein synthesis (EL1), dopamine neural activity (DDC) and regeneration (SRF1) where the genes that best discriminated the toxic effects of the nAg-CWNT composites, nAg and CWNT. (Hoffmann and Kroiher, 2001). In adult Hydra, the abundance of SRF transcripts varies during the day. The pacemaker of this diurnal rhythm is the feeding regime. Expression of SRF1 occurs in the ectodermal layer and in the endodermal epithelial cell mass and I-cells of the body. Expression of SRF1 ceases when I-cells differentiate into nerve, nematocytes or gland cells. This suggests that either the feeding regime or cell regeneration and differentiation is decreased in hydra exposed to the nAg-CWNT composites. On the one hand, exposure to large microplastic (<400 µm) within the size range of the tube length of the CWNT (10-30 µm) were found to reduce feeding rates in hydra (Murphy and Quinn, 2018). On the other hand, exposure to small polymethylmethacrylate plastic nanoparticles (40 nm) had no effect on hydra feeding activity albeit at relatively high concentration of 10-40 mg/L (Venâncio et al, 2021). Decreased algal feeding activity was also observed in Daphnia magna exposed to 3.9 mg/L CWNT after 48h with fiber length >1µm based on clay particle size effects on algal feeding (Stanley et al., 2016). This suggests that CWNT fibers length in the microplastic scales could also contribute to feeding rates and perhaps towards SRF1 gene expression.

The appearance of rod-like nanocrystals stimulated neural activity in Hydra (Malvindi et al., 2008). Exposure to quantum rods but not spheres induced an unexpected Ca2+-dependent tentacle-writhing behavior that relies of tentacle neurons. Dopamine signaling is involved in awake/activity periods in Hydra and tentacular regeneration (Omond et al., 2022; Markova et al., 2008). Flatworms and hydra exposed to neurotransmitters involved in wakefulness in vertebrates (acetylcholine, dopamine, glutamate and histamine) increased activity time from periods of inactivity. Conversely, sleep inducing neurotransmitters (adenosine, GABA and serotonin) increased resting times. Exposure to CWNT induced DDC gene expression (involved in the conversion of dopamine from L-DOPA) while this effect was lost with the nAg-CWNT composites. However, gene expression involved in regeneration (SRF1) was significantly decreased after correction with either CAT or EL1 gene expression in hydra exposed to the nAg-CWNT composites (ANCOVA p<0.01 for concentration and CAT or EL1 as the covariate) where SRF1 gene expression was correlated with dopamine production (DDC), oxidative stress (SOD, CAT) and protein synthesis (EL1). N-arachidonoyl dopamine accelerated tentacle formation in both the gastral and basal fragment of the body (Margova et al., 2008). This is in keeping with a previous study showing the dopamine synthesis inhibitors and antagonists decreased hydra regeneration and growth (Ostroumova and Markova, 2002). However, the lipid analogue docohexanoyl dopamine complex was shown to induce morphological abnormalities of the gastric part of the body by the formation of single ectopic tentacle (Ostroumova et al., 2010). Since docohexanoic acid and dopamine alone did not produce these effects, it was considered that the doxohexanoyl complex of dopamine altered tissue regeneration and growth.

In conclusion, the toxicity of nAg-CWNT composites were shown to induce sublethal morphological changes at concentration below those for nAg and CWNT alone suggesting that the tube-like presentation of nAg could induce sub-lethal toxicity in hydra. Sublethal effects were associated to oxidative stress (CAT) and protein synthesis (EL1) while lethality involved a broader subset of genes involved in additional genes such as dopamine activity (DDC), MAPC3l and MANF. SRF1 gene expression was highly correlated with oxidative stress biomarkers and dopamine signaling and its expression readily decreased following covariance analysis. The data suggests that nAg-CWNT composites introduce changes at the gene expression levels and morphological changes that are not solely explained by nAg or CWNT alone.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Hibah Quichach and Maxime Gauthier for tissues preparation, RNA extraction and qPCR assays are dully recognized. The analysis of PGEs in the hydra medium was examined by Patrice Turcotte and Christian Gagnon. This work was funded by the chemical management plan of Environment and Climate Change Canada.

References

- Auclair J, Gagné F 2022. Shape-Dependent Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles on Freshwater Cnidarians. Nanomaterials (Basel) 12, 3107. [CrossRef]

- Auclair J, Turcotte P, Gagnon C, Peyrot C, Wilkinson KJ, Gagné F. 2023. Investigation on the Toxicity of Nanoparticle Mixture in Rainbow Trout Juveniles. Nanomaterials (Basel). 13, 311. [CrossRef]

- Auclair J, Peyrot C, Wilkinson KJ, Gagné F. 2021. The geometry of the toxicity of silver nanoparticles to freshwater mussels. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 239m 108841. [CrossRef]

- Blaise, C., Kusui, T., 1997. Acute toxicity assessment of industrial effluents with a microplate-based Hydra attenuata assay. Environ. Toxicol. Water Qual. 12, 53–60.

- Blaise C, Gagné F, Férard JF, Eullaffroy P 2008. Ecotoxicity of selected nano-materials to aquatic organisms. Environ Toxicol 23, 591-598.

- Bolaños-Benítez V, McDermott F, Gill L, Knappe J 2020. Engineered silver nanoparticle (Ag-NP) behaviour in domestic on-site wastewater treatment plants and in sewage sludge amended-soils. Sci. Total Environ 722, 137794.

- Cera A, Cesarini G, Spani F and M, Scalici 2020. Hydra vulgaris assay as environmental assessment tool for ecotoxicology in freshwaters: a review Marine and Freshwater Research 72, 745-753.

- Côa F, Strauss M, Clemente Z, Neto LLR, Lopes JR, Alencar RS, Filho AGS, Alves OL, Castro VLSS, Barbieri E, Martinez DST 2017. Coating carbon nanotubes with humic acid using an eco-friendly mechanochemical method: Application for Cu(II) ions removal from water and aquatic ecotoxicity Sci Total Environ 607-608, 1479-1486.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada Canada,2020. Sublethal and lethal evaluation with the Hydra attenuata – Method for aqueous solutions. Q0404E2.

- Fatima, J., Ara, G., Afzal, M., & Siddique, Y. H. (2024). Hydra as a research model. Toxin Reviews, 43(1), 157–177. [CrossRef]

- Finney DJ 1964. Statistical method in biological assay. Hafner Publishing Company, 668 pages.

- Ghaskadbi, S., 2020. Hydra: a powerful biological model. Resonance, 25 (9), 1197–1213.

- Gottardo S, Mech A, Drbohlavová J, Małyska A, Bøwadt S, Riego Sintes J, Rauscher H. 2021. Towards safe and sustainable innovation in nanotechnology: State-of-play for smart nanomaterials. NanoImpact 21, 100297.

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408.

- Hoffmann U, Kroiher M 2001. A possible role for the cnidarian homologue of serum response factor in decision making by undifferentiated cells. Dev Biol 236, 304-315.

- Malvindi MA, Carbone L, Quarta A, Tino A, Manna L, Pellegrino T, Tortiglione C 2008. Rod-shaped nanocrystals elicit neuronal activity in vivo. Small 4, 1747-1755.

- Markova LN, Ostroumova TV, Akimov MG, Bezuglov VV 2008. [N-arachidonoyl dopamine is a possible factor of the rate of tentacle formation in freshwater hydra]. Ontogenez 39, 66-71.

- McGillicuddy E, Murray I, Kavanagh S, Morrison L, Fogarty A, Cormican M, Dockery P, Prendergast M, Rowan N, Morris D 2017. Silver nanoparticles in the environment: Sources, detection and ecotoxicology. Sci Total Environ 575, 231-246.

- Murphy F, Quinn B 2018. The effects of microplastic on freshwater Hydra attenuata feeding, morphology & reproduction. Environ Poll 234, 487-494.

- Omond SET, Hale MW, Lesku JA 2022. Neurotransmitters of sleep and wakefulness in flatworms. Sleep 45, zsac053.

- Ostroumova TV, Markova LN 2002. The effects of dopamine synthesis inhibitors and dopamine antagonists on regeneration in the hydra Hydra attenuata. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 32, 293-298.

- Ostroumova TV, Markova LN, Akimov MG, Gretskaia NM, Bezuglov VV 2010.

- [Docosahexaenoyl dopamine in freshwater hydra: effects on regeneration and metabolic changes] Ontogenez 41, 199-203.

- Selvam S. Menon N, Satheesh A, Cheriyathennatt S, Kandasamy E 2023. Evaluation of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube-Silver Nanocomposite: A Fluorescence Spectroscopic Approach. Journal of Fluorescence. [CrossRef]

- Stanley JK, Laird JG, Kennedy AJ, Steevens JA 2016. Sublethal effects of multiwalled carbon nanotube exposure in the invertebrate Daphnia magna. Environ Toxicol Chem 35, 200-204.

- Venâncio C, Savuca A, Oliveira M, Martins MA , Lopes I 2021. Polymethylmethacrylate nanoplastics effects on the freshwater cnidarian Hydra viridissima, J Hazard Mater. 402,123773.

- Vimalkumar K, Sangeetha S, Felix L, Kay P, Pugazhendhi A 2022. A systematic review on toxicity assessment of persistent emerging pollutants (EPs) and associated microplastics (MPs) in the environment using the Hydra animal model. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 256, 109320.

- Walters CR, Pool EJ, Somerset VS. 2014. Ecotoxicity of silver nanomaterials in the aquatic environment: a review of literature and gaps in nano-toxicological research. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 49, 1588-1601.

- Zhang C, Hu Z, Deng B 2016. Silver nanoparticles in aquatic environments: physiochemical behavior and antimicrobial mechanisms. Water Res. 88, 403-427.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).