Introduction

Plastics products pervade most compartments in the environment (soil, sediment and surface waters) due to the massive production and inefficient recycling and waste disposal activities (Atugoda et al., 2023; Avio et al., 2017). Plastics are generally perceived as an inert material, safe and inexpensive materials resulting in a wide range of applications (cars, furniture, households) and an inevitable material for food containers and clothing. The inadequate disposal management of these plastic materials contributes to their release in the environment finding their way in both freshwater and marine ecosystems worldwide. It is estimated that only 9% of plastic materials are recycled with 19% destined for incineration and the remainder in landfills (OECD, 2022). In addition, it was estimated that 20-25 % of plastic waste ends up in uncontrolled dumpsites and ultimately released in adjacent terrestrial and aquatic environments. Polypropylene (PP) is used for face masks, which was massively used during the COVID-19 pandemic and significantly contributed to the already growing plastic contamination problem (Zimmermann et al., 2019; Plastic Europe, 2023). PP and polyethylene (PE) along with polystyrene and polyvinyl represents the most commonly plastic material and they are often detected in various ecosystems (Argeswara et al., 2021). Weathering and degradation of plastics are relatively slow process leading to the gradual breakdown of plastic debris into microparticles (<5 mm-1 µm) and nanoparticles (1-1000 nm). Nanoplastics (NPs) are considered more dangerous to organisms since they can easily pass through biological barriers finding their way in various organs and absorbed in cells by various mechanisms such as phagocytosis and pinocytosis (Antunes et al., 2025). The reported levels of nanoplastics in wastewaters and rivers from largely populated area were between 0.1-100 µg/L (Junaid et al., 2024; Gagné et al., 2024; André et al., 2025). Maximum concentrations reached the upper µg/L range (500-1000 µg/L) in some cases. It appears that most plastic nanoparticles were from domestic plastic waster emissions and street runoffs among urban sites, while in rural sites, the contribution results from aquaculture, agriculture and road runoffs from tire wear materials.

The cnidarian

Hydra vulgaris Pallas, 1766 is a sensitive invertebrate of the benthic community for the toxicity assessments of miscellaneous chemicals and liquid mixtures (Cera et al., 2020; Farley et al., 2024). Hydra is commonly found in tropical and temperate freshwaters attached to various substrates such as rocks, tree barks and plants. It is a relatively simple organism composed of two layers of cells forming a head with 5-7 tentacles attached to tubular body (5-10 mm long) attached to a solid substrate (

Figure 1S). The head comprises the tentacles and the mouth for food intake and exudation of detritus and nondigested material at tubular body. The tubular body is composed of 2 parts composed of the mouth and digestive system at the upper end and the lower body for reproduction where polyps offsprings emerge from the body. They feed on small invertebrates such as copepods and water fleas. They are solitary and sessile organisms and reproduce asexually most of the time. These organisms have remarkable regenerative abilities, growing and reproducing without significant aging. Reproduction occurs through a budding process at the lower part of the tubular body (

Figure 1S) with a population doubling time of 4-5 days depending on the experimental conditions such as temperature, media composition and feeding rates (Farley et al. 2024). One attractive feature of the hydra resides in its sensitivity towards contaminants, often better than salmonids, and is considered a viable alternative to fish bioassays. There is a pressing need to reduce/replace fish for toxicity assessments needed for compliance surveillance and monitoring of complex effluents and leachates in the environment. Toxicity is usually measured by a series of morphological changes following the severity of toxic effects. Reversible (sub-lethal) morphological changes consist of antennae shortening (at least more than one third its original length) with budding at the tip of the antennae. If toxicity reaches lethal levels, severe antennae and body compression forming a tulip-like appearance is observed and indicates irreversible (death) damage. Because of the small size of hydra, biomarkers assessment studies are wanting at the present to understand changes at the molecular level that precedes morphological changes. A quantitative polymerase chain reaction methodology has been recently developed to understand the sublethal effects of various emerging contaminants before the onset of morphological changes (Auclair et al., 2024a and b). This toxicogenomic platform involves gene expression for oxidative stress (superoxide dismutase, catalase), DNA repair (8-oxoguanine excision), damaged protein recycling (ubiquitination and autophagy), neural activity (dopamine decarboxylase and neuronal cell repair) and differentiation (under circadian rhythm). Plastics NPs are well recognized to induce oxidative stress and increased protein ubiquitination in exposed organisms leading to lipid peroxidation, DNA damage and the removal of denatured proteins (Antunes et al., 2025; Acar et al., 2024). NPs were shown to induce protein denaturation leading to ubiquitin tagging for removal by the proteasome-ubiquitin pathway in cells (Gagné et al., 2013). The above studies revealed that important changes in gene expression are at play before the onset of morphological changes in hydra. The sublethal effects of plastic nanoparticles are not well understood in aquatic invertebrates and merits investigation for the protection of the aquatic benthic community.

The purpose of this study was therefore to examine the sublethal toxicity of PENPs and PPNPs to Hydra vulgaris. The PE and PPNPs were of the same size range (50-70 nm) to minimize size related effects. Given that PE and PP are non-polar aliphatic polymers, their toxic properties should be similar for NPs of similar size at the nanoscale (null hypothesis). The toxic properties were examined at the morphological changes (shortening of tentacles and budding) and at the gene expression levels from the physiological targets described above. An attempt was made to relate gene expression changes with toxicity effects based on morphological observations.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and nanoplastic preparation

The plastic nanoparticles (NPs) were purchased from CD Bioparticles (New York, USA). DiagpolyTM polyethylene nanoparticles (PENPs) with a diameter of 50 nm (polydispersity index <0.1) were purchased as 1% concentration (10 mg/mL) in the suspension media composed of 0.1% Tween-20 and 2 mM NaN3. This suspension contained 1x1014 NPs/mL. DiagPoly™ Polypropylene nanoparticles (PPNPs), 50 nm (PDI < 0.2), supplied at 10 mg/mL in the same suspension media and contained the same number of NPs as with PENPs. The vehicle thus contains Tween 20 and NaN3 from which is considered the solvent control (vehicle). The highest exposure concentration of 10 mg/L therefore contained 0.0001 % Tween 20 and 2 µM NaN3 and constitute the vehicle control. No sublethal and lethal morphological changes were observed for the vehicle. Preliminary experiments were performed to evaluate the solubility of based on turbidity measurements at 600 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy IV, Biotek instrument). A 100 mg/L and 10 mg/L solution was prepared in the hydra exposure media and allowed to stand for 1 and 96h at room temperature in the absence of hydra. Then 200 µL of the suspension was collected in clear microplates and measured at 600 nm.

Aquatic toxicity assessment with Hydra vulgaris

The exposure to PP and PENPs to

Hydra vulgaris followed a standard methodology based on previous studies (Blaise and Kusui, 1997; Blaise et al., 2018; Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020). Hydras were reared in crystallization bowls containing 100 mL of the Hydra medium composed of 1 mM CaCl

2 containing 0.4 mM TES buffer pH 7.5.

Artemia salina brine shrimps were used as the food source and they were fed every 2 days during maintenance. The shrimps were rinsed in Hydra media (centrifugation 100 ppm 5 min, resuspension in Hydra medium) before adding them to the hydra to remove excess of salts. A 16h/8h day/dark cycle at 20-22

oC was used and the hydra doubling time was 4.5 days. Hydra were not fed 12h prior to the initiation of the exposure experiments. Adult hydras (n=3) were placed in each of three wells in 12-well microplates in 4 mL of the Hydra medium. They were exposed to increasing concentrations PENPs and PPNPs (0, 0.3, 0.6, 1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 mg/L) for 96 h at 20

oC. On a particle basis, the exposure concentrations were 3, 6, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 x10

9 particles/mL. Two other microplates were prepared for replication to ensure sufficient amount of hydra for gene expression analysis. Following the 96h exposure period, the morphology of hydra was observed on 4-6 X stereomicroscope and lethal and sublethal toxicity were measured (# of hydra presenting the morphological alterations in

Figure 1S). The lethal concentration that kills 50 % of the hydra (LC50) and the sublethal effect concentration of 50 % of the hydra (EC50) were determined using the Spearman-Karber method (Finney, 1964). The morphological changes for lethal (tulip and disintegrated body) and sub-lethal (budding and shortening of tentacles) effects were determined using at 6X stereomicroscope. Morphologically unaffected hydras were collected for gene expression analysis at some of the exposure concentrations. Hydra were harvested with a 1 mL pipet and immediately transferred in RNA later solution (Millipore Sigma, ON, Canada) and stored at -20

oC for gene expression analysis.

Gene expression analysis

Gene expression analysis was determined by a newly developed quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRTPCR) for

Hydra vulgaris (Auclair et al., 2024a). A total of 9 hydra (3 wells) was sufficient for RNA extraction and purity analysis using the NanoDrop spectrometer. RNA integrity was confirmed by solid phase (tape) electrophoresis system (Agilent RNA ScreenTape Assay (cat # 5067-5576, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was conducted following the reported levels of gene targets from Auclair et al. (2024a) and are described (

Table 1). HPRT, RPLPO, Efα were selected as possible reference gene for norrmalisation with baseline RNA levels. Data analysis was performed using CFX Maestro software package (Bio-Rad). The data were expressed as relative mRNA levels to controls.

Data analysis

The exposure experiments were repeated twice with three microplates comprising 3 hydras per well and 3 replicate wells per exposure concentration was used. Gene expression data was expressed as effect threshold concentration (mg/L) and defined as follows: effect threshold = (no effect concentration x lowest significant effect concentration)1/2. The gene expression data were analyzed using a rank-based analysis of variance followed by the Conover-Iman test for differences from the controls. Relationships between gene expression data for each plastics (PENPs, PPNPs) were determined using the Pearson-moment procedure. The gene expression data were also analyzed by discriminant function analysis to seek out similarities (or difference) between the effects from PENPs and PPNPs and determine the genes whose expression best discriminate between PP and PE. Significance was set at p < 0.05. All the statistical analyses were conducted using SYSTAT (version 13, USA).

Results

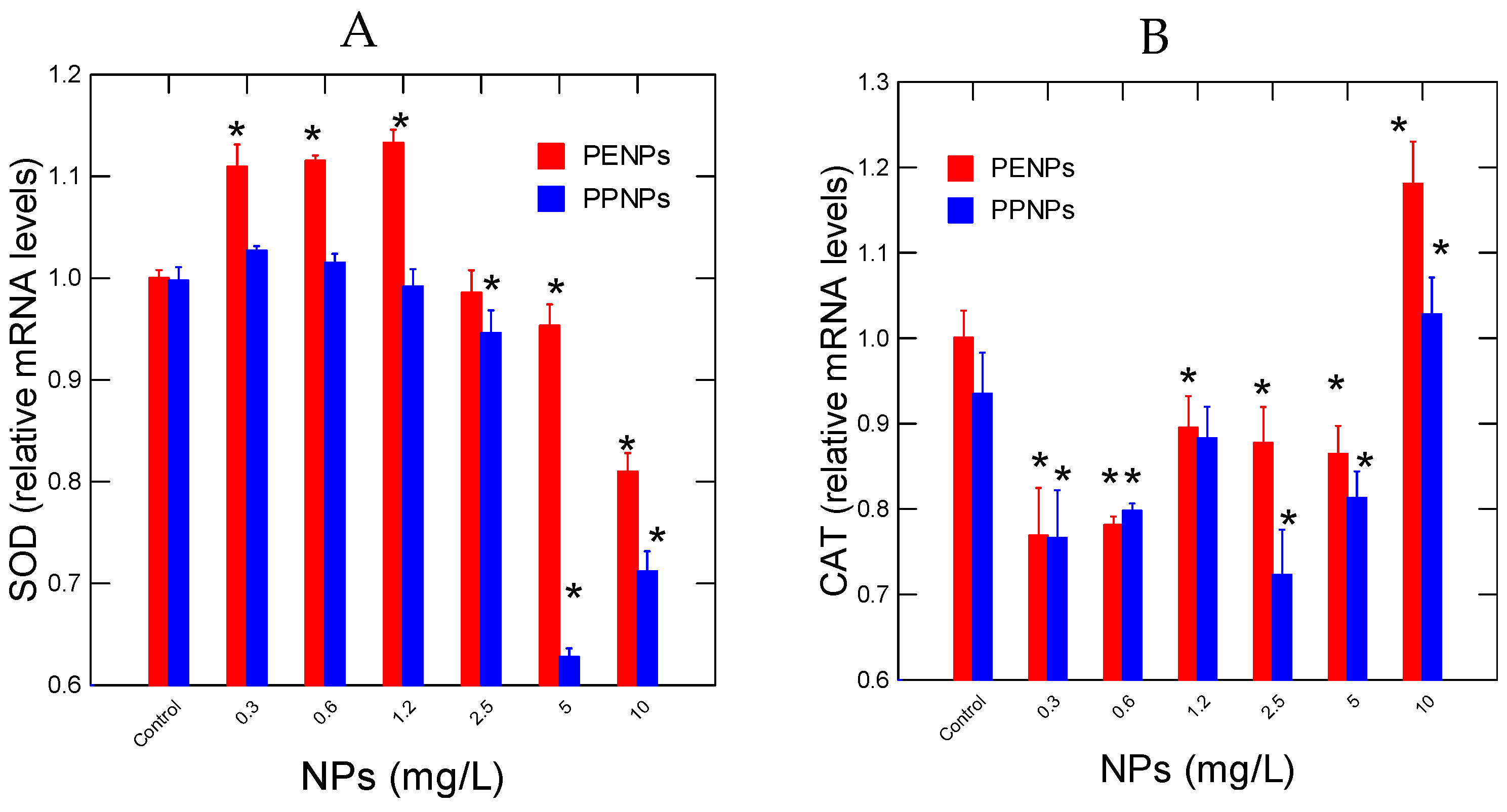

No evidence of NPs loss was observed based on turbidity measurements in the incubation and precipitation. The toxicity of PE and PP NPs in hydra revealed no lethal effects for concentrations up to 10 mg/L. Sublethal effects were observed for PPNPs with an EC50 =7 mg/L. The effects of PENPs and PNPs on oxidative stress were examined by CAT and SOD gene expression (

Figure 1). For PENPs, an increase in SOD activity was observed at 0.3-1.25 mg/L with a gradual decrease at higher concentrations (

Figure 1A). For PPNPs, decreased SOD gene expression occurred at a threshold concentration of 1.8 mg/L, which is below the EC50 value of 7 mg/L. The expression of CAT gene expression followed a biphasic response to both PENPs and PPNPs (

Figure 1B). CAT gene expression was decreased at low concentrations between 0.3-5 mg/L followed by an increase at 10 mg/L. SOD and CAT was negatively correlated only for PENPs (-0.71) (

Table 2).

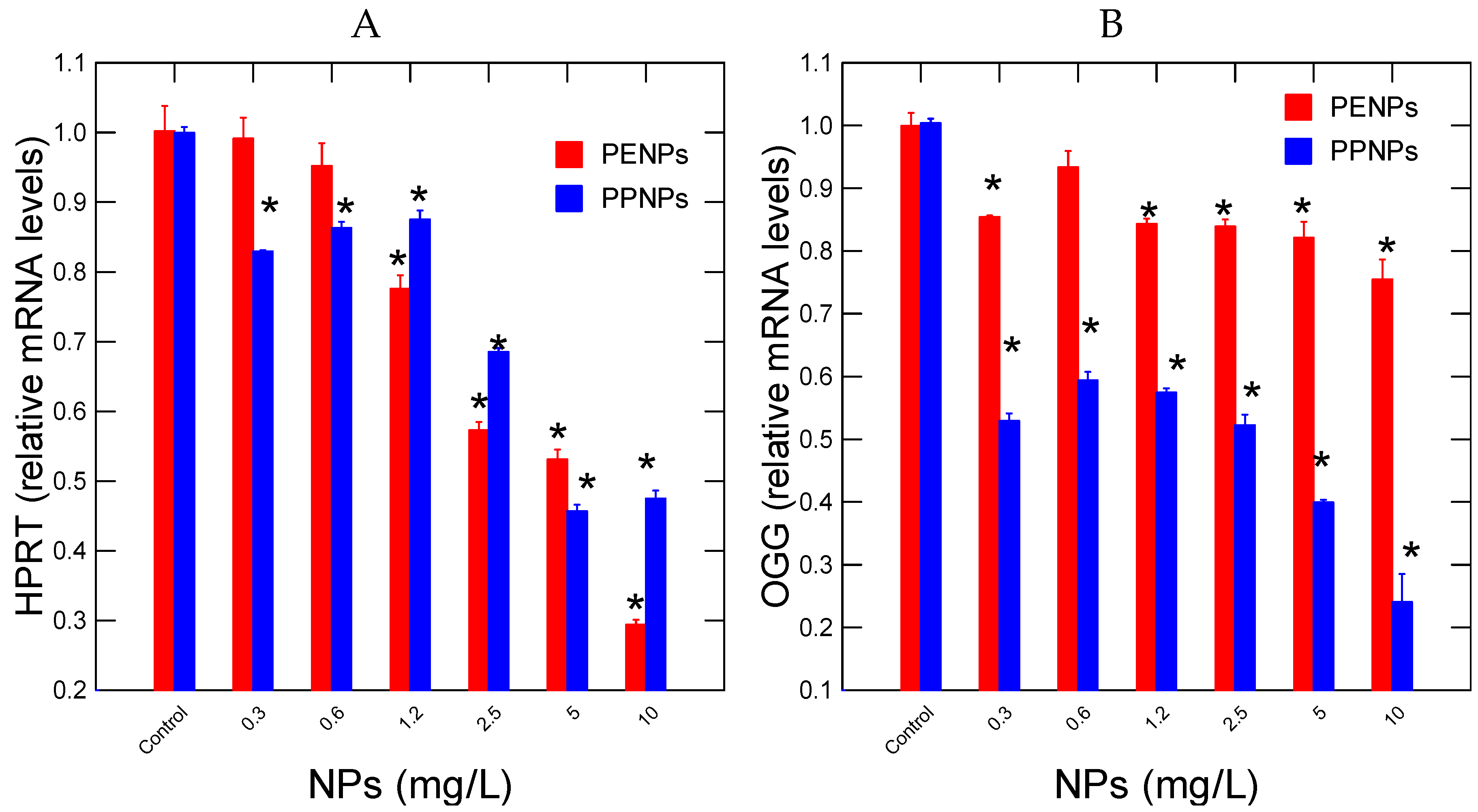

Changes in purine salvage pathway (HPRT) and repair (8-oxo-guanosine) were determined in hydra exposed to plastic NPs (

Figure 2). For PENPs, the gene responsible recycling guanine and inosine in the purine salvage pathway (HPRT) was significantly reduced at a threshold concentration of 0.88 mg/L For PPNPs, the purine salvage pathway was significantly reduced at the lowest concentration of 0.3 mg/L. This suggests that in both cases, DNA turnover was decreased upon exposure of NPs. For PENPs, correlation analysis revealed that HPRT gene expression was correlated with CAT (r=-0.43) and SOD (r=0.72). For PPNPs, correlation analysis revealed that HPRT gene expression was related with SOD (r=0.89). In respect to OGG gene expression involved in the repair of 8-oxoguanosine adducts, the gene expression was decreased at the lowest exposure concentration for both NPs (

Figure 2B). The intensity of inhibition was stronger for PPNPs than PENPs with 2- and 1.2-fold inhibitions respectively. Correlation analysis revealed that OGG gene expression was correlated with HPRT gene expression (r=0.72) for PENPs. For PPNPs, correlation analysis revealed that OGG gene expression with SOD (r=0.63) and HPRT (r=0.87).

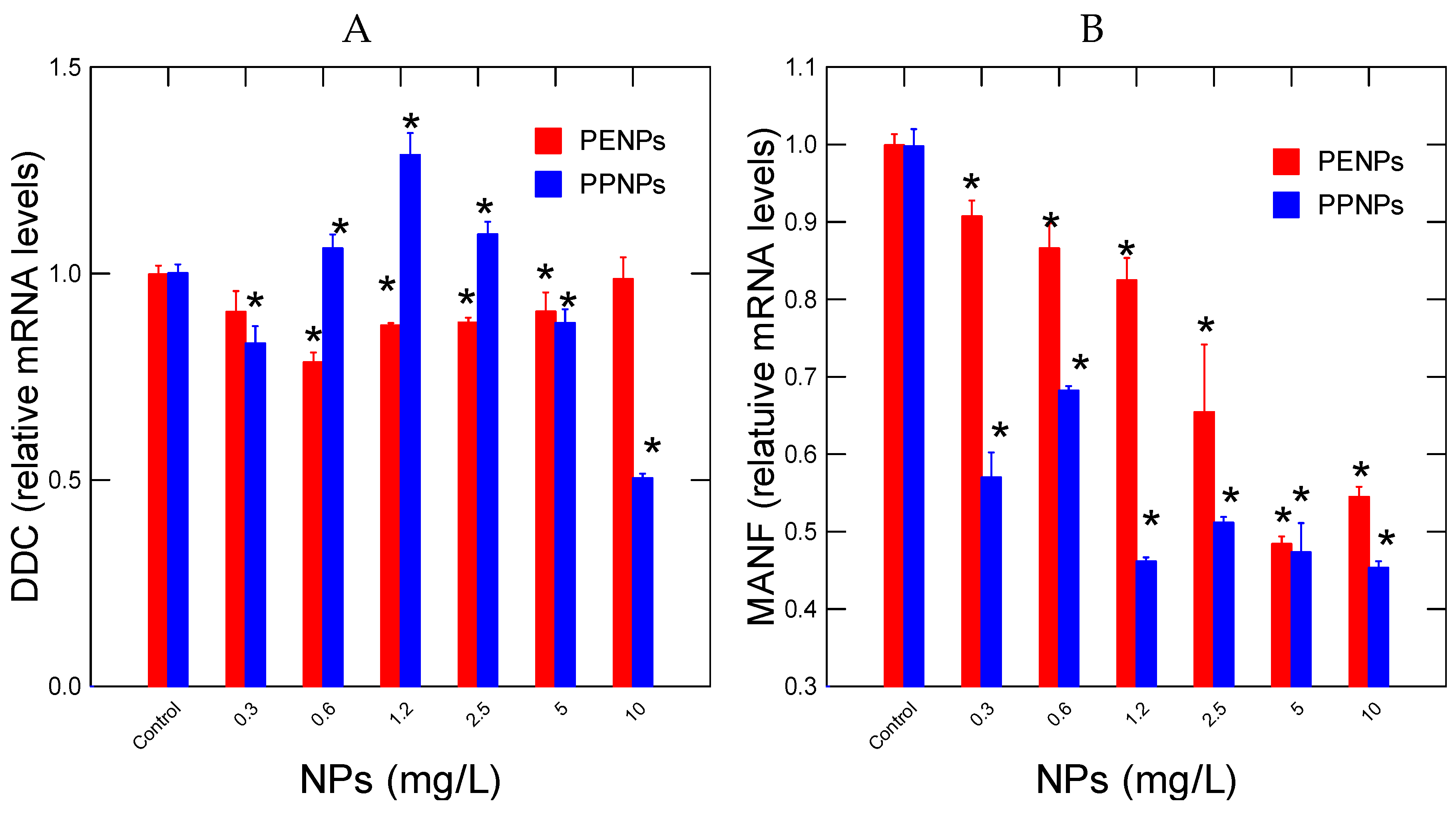

Neural activity was followed in hydra by measuring changes in DDC and MANF gene expressions involved in dopamine decarboxylase (L-DOPA→ dopamine) activity and cell repair of damaged dopaminergic neurons respectively (

Figure 3). For PENPs, DDC gene expression was initially decreased at low exposure concentrations and returned to control levels at 10 mg/L (

Figure 3A). Correlation analysis revealed that DDC gene expression was correlated with CAT gene expression (r=0.52). For PPNPs, the expression of DDC was significantly increased at concentrations up to 2.5 mg/L followed by a significant decrease at 5 and 10 mg/L. Correlation analysis revealed that DDC gene expression was correlated with CAT (r=-0.4), SOD (r=0.55), HPRT (r=0.56) and OGG (r=0.46). The levels of MANF involved in neural cell repair were also evaluated (

Figure 3B). MANF gene expression was readily decreased for all exposure concentration for both PE and PPNPs. For PENPs, MANF gene expression was significantly correlated with SOD (r=0.57), HPRT (r=0.85) and OGG (r=0.69). For PPNPs, gene expression of MANF was significantly correlated with SOD (r=0.51), HPRT (r=0.76) and OGG (r=0.92). This suggests that cell repair activity of MANF involved oxidative stress and the oxidation of (8-oxoguanosine adduct formation).

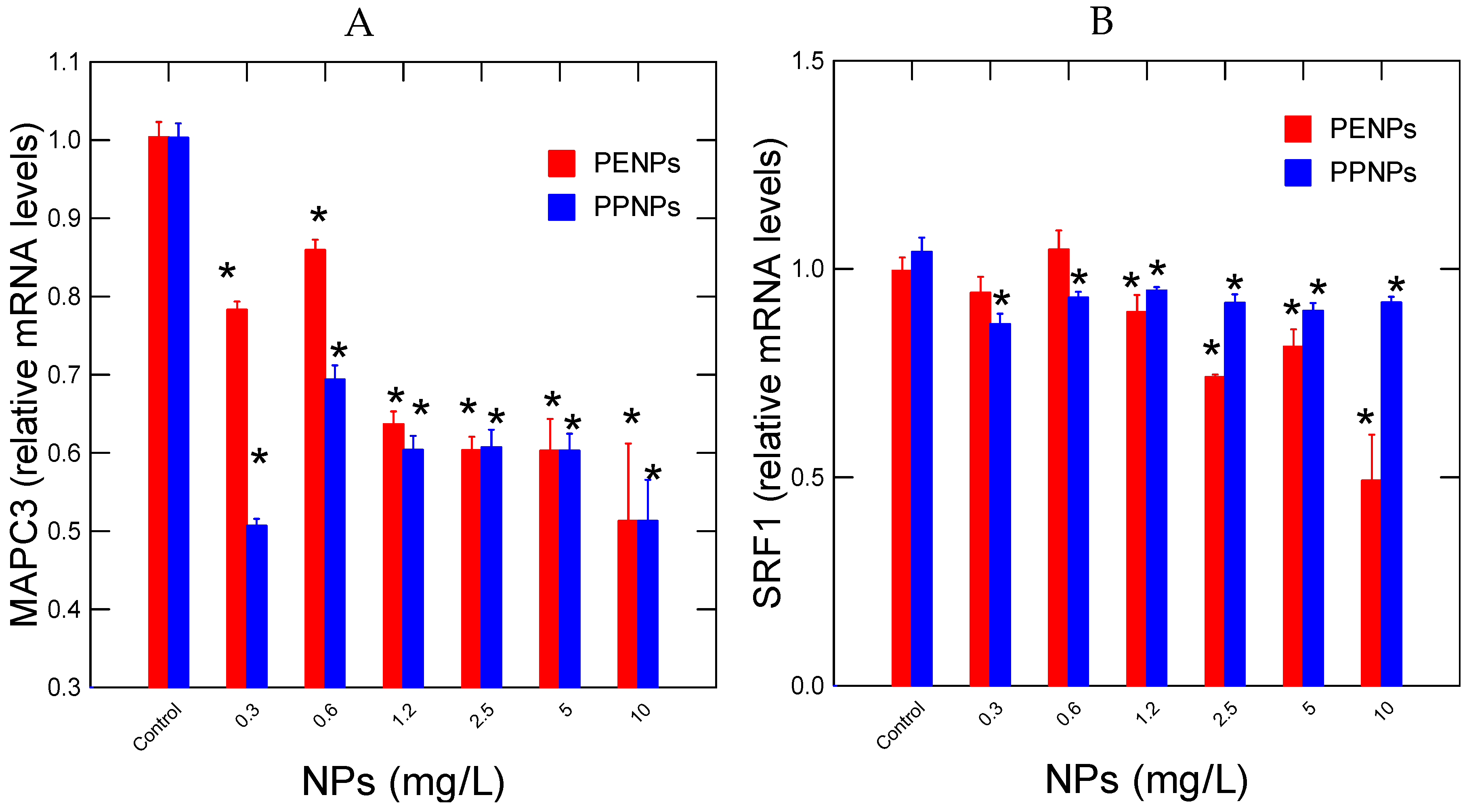

The expression of damaged protein salvage pathway (MAPC3) and differentiation (SRF1) in hydra exposed to PENPs and PPNPs were examined (

Figure 4). Both PENPs and PPNPs were able to decrease gene expression for in MAPC3 at the lowest exposure concentration of 0.3 mg/L (

Figure 4A). Correlation analysis revealed that MAPC3 mRNA levels were correlated with HPRT (r=0.86), OGG (r=0.86) and MANF (r=0.79) for PENPs. For PPNPs, MAPC3 levels were correlated with HPRT (r=0.67), OGG (r=0.88) and MANF (r=0.9). Gene expression of SRF1 was decreased at 1.2 and 0.3 mg/L for PENPs and PPNPs respectively (

Figure 4B). The decrease was stronger for PPNPs compared to PENPs. Correlation analysis revealed that SRF1 gene expression for PENPs was significantly correlated with CAT (r=-0.43), SOD (r=0.7), HPRT (r=0.81), OGG (r=0.6), MANF (r=0.63) and MAPC3 (r=0.76). For PPNPs, SRF1 was correlated with HPRT (r=0.54), OGG (r=0.67), MANF (r=0.53) and MAPC3 (r=0.72).

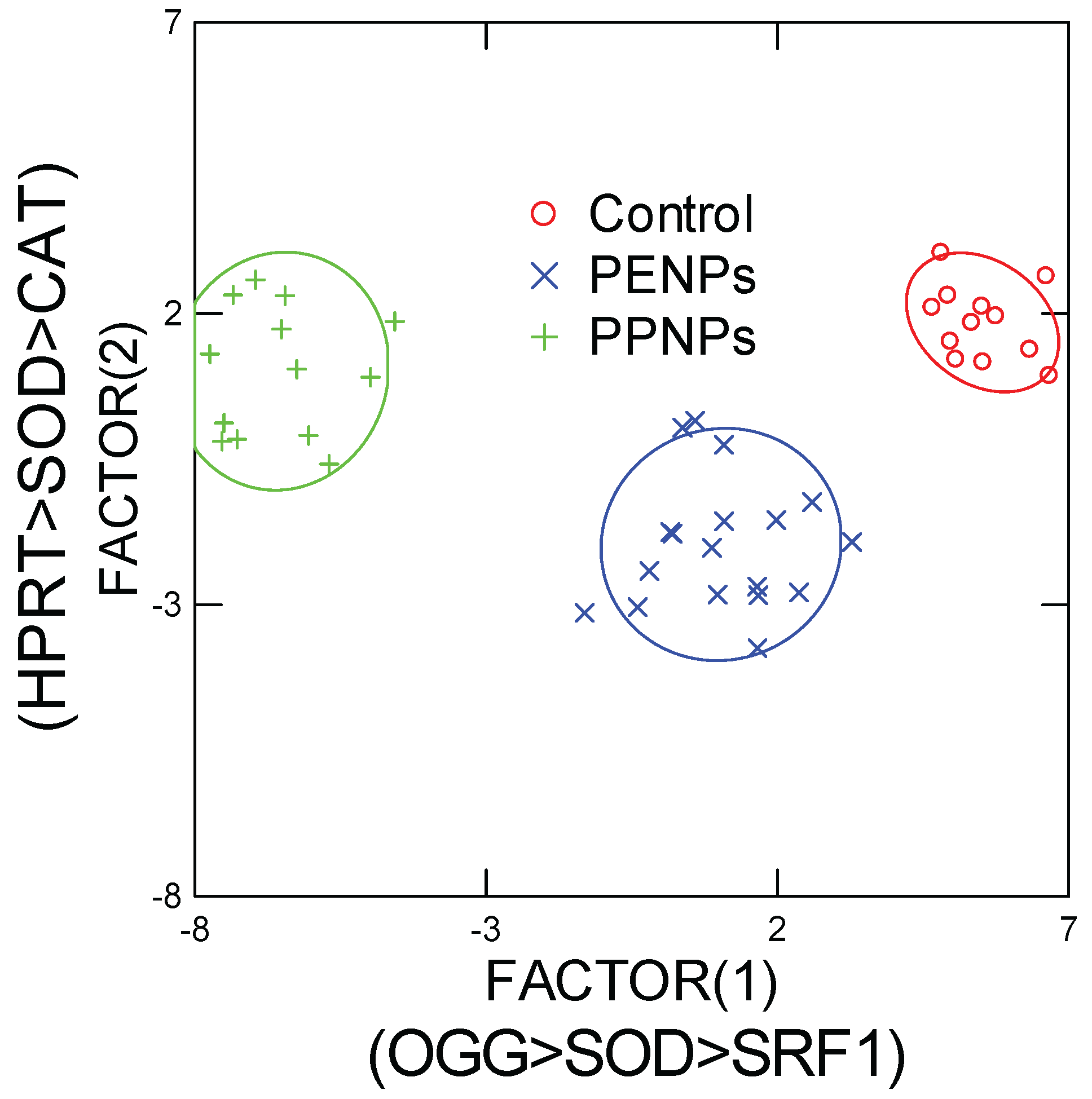

In the attempt to gain a global understanding of gene expression changes induced by PENPs and PPNPs and to test the null hypothesis (i.e., the toxic effects of PENPS and PPNPs are identical), a discriminant function analysis was performed (

Figure 5). The analysis revealed that the effects of each plastic nanoparticles were readily discriminated (100 % efficiency) from each other based on DNA repair (OGG), SOD and SRF1 gene expressions (component 1 of x axis). HPRT and CAT gene expressions were also involved (y axis) but the discrimination was not clear on this axis. This suggests that oxidative stress (SOD involved in the production of H

2O

2 from oxygen radicals), reparation of oxidized DNA and cell differentiation were the main molecular events involved in the difference between PENPs and PPNPs. It was noteworthy that PENPs were closest to controls suggesting less toxicity compared to PPNPs in keeping for the observed stronger responses in gene expressions and the manifestation of sublethal morphological changes (EC50 of 7.1 mg/L).

Discussion

Plastic nanoparticles were reported to induce oxidative stress in various organisms (Hara et al., 2024). Indeed, exposure to aged polyethylene terephthalate micro and nanoplastic particles led to elevated reactive oxygen species formation in granulocytes and hyalunocytes (hemocytes) in Mytilus edulis. The particle concentration range was in the order of 101 to 105 particles/m. In Hydra, PENPs increased the expression of SOD at low concentrations (0.3-1.2 mg/L) followed by inhibitions at higher concentrations. CAT gene expression was only induced at the highest concentration of 10 mg/L. In another study with yeast, PE teraphtalate nanoplastics caused oxidative stress and induced cell death (Kaluc et al., 2024). PENPs induced gene expression involved in oxidative stress (including Yap1, GPX1 and CTT1) and produced lipid peroxidation at concentrations between 2 – 5 mg/L. Evidence of stress at the levels of glucose deprivation, osmotic stress and heat shock proteins were also observed based on the upregulation of MSN2 and MSN4 transcription factors. The study also revealed that autophagy had a protective role against PENPs. This is consistent with the hydra responses where MAPC3 gene expression involved in protein denaturation salvage and autophagy was downregulated both PE and PPNPs.

In respect to genotoxicity, gene expression in OGG was downregulated by both PENPs and PPNPs and the inhibition was stronger with the more toxic PPNPS as with MAPC3 above. This suggests that decreased DNA repair activity are also associated with toxicity in hydra. In HepG2 cells exposed to various types of NPs, the toxicity of PETNPs and PVCNPs were more toxic than PSNPs of similar sizes. Toxicity was produced by oxidative stress and inhibition of expression of DNA-repair genes in the p53 signaling pathway (Ma et al., 2024). The reasons of the different toxicity between types of plastics are unclear but it appears that the aliphatic nature of the plastic have a role in toxicity. For example in hydra, the toxicity of polypropylene was higher than polyethelene nanoparticles based on morphological changes with an EC50 =7 mg/L. The sublethal toxicity of 50 nm PSNPs were 3.6 mg/L (Auclair et al., 2020) suggesting that PSNPs was somewhat more toxic than PPNPs of similar size. This suggests that not only aliphatic properties of plastic NPs are associated to toxicity in hydra. The toxicity of various plastic leachates to macrophage cell viability was investigated the cell viability and gene expression levels (Islam et al 2024). The size distribution of plastic nanoparticles leaching from the plastic materials were between 50 and 440 nm size range and were irregular in shape. All types were able to reduce cell viability in a concentration dependent manner and PP, PS and high density PE were more toxic than polyethylene methacrylate and polyethylene teraphtalate based on cell viability. This suggest that the plastic made from more polar compounds (esters) are seemingly less toxic than less polar plastic materials such as polyethylene, polystyrene and polypropylene nanoplastics. It is noteworthy to note that polypropylene contamination was increased from the improper disposal of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Hyallela azteca amphipods, 10-day exposure to either polyethylene and polypropylene microparticles results in decreased survival with 4.64 x 104 microplastics/mL and 71.43 microplastics/mL, respectively (Au et al., 2015). This corroborates the hydra toxicity data showing that PPNPs were more toxic than PENPs. The study also showed that microplastic fibers were more toxic than particles and resided for longer periods of time in the digestive system of the amphipods. Although leachates from commercial plastics materials contain both nanoparticles and plasticizers, the toxicity of polyethylene, polystyrene, and polypropylene leachates were investigated in Dunaliella tertiolecta algae (Schiavo et al., 2021). Polypropylene and polystyrene reduced viability and growth at the lowest concentration of the leachate (3.1 %). All leachates were able to induce oxidative stress in alga but only PP leachates produced genotoxic effects in keeping with reduced DNA repair activity. Interestingly, GC-MS analysis revealed the absence of low molecular weight organic compounds usually found in plastics (plasticisers and flame retardants). This indicates that the polymeric materials (i.e., high molecular weight polymers and nanomaterials) and perhaps the associated metals/metalloids were responsible for toxicity.

The observed biphasic responses in DDC activity and decreased gene expression in MANF involved in the repair of dopaminergic neuronal cells suggest that these plastic nanoparticles are neurotoxic as well. DDC activity was increased at low exposure concentrations suggesting that the hydra were in wake and feeding state; conversely decreased DDC gene expression at higher exposure concentration suggests that hydra were in sleep/resting state. Polyprolylene microplastics were shown to reduce acetylcholinesterase activity in Artemia salina shrimps suggesting impacts on the nervous systems (Jyavani et al., 2022). In another study with zebrafish, exposure to PSNPs (70 nm diameter) lead to altered locomotor circadian rhythms in addition to oxidative stress (Sarasamma et al., 2020). This also led to disruptions in locomotor activity, aggressiveness, shoal formation and predator avoidance in fish exposed to 1.5 mg/L PSNPs. While dopamine, glutamate and histamine are associated to the awake phase were feeding takes place, serotonin, melatonin and GABA neurotransmitters are involved in sleep/resting phase of hydra (Kanaya et al., 2020; Omond et al., 2022). The SRF1 gene is involved in the pacemaker/circadian cycles during the day (Hoffman and Koiher, 2001). SRF1 is involved in the differentiation of I-cells into nerve cells, nemotocytes and gland cells. In adult hydra, the abundance of SRF transcript varies during the day where its expression decreases 4h after feeding and is re-expressed after12h. The decrease in SRF1 by PP (0.3 mg/L) and PENPs (1.2 mg/L) suggests that the circadian rhythm of hydra is disrupted by these nanoplastics where stronger effects at lower concentration with PPNPS, producing sublethal morphological changes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, exposure of hydra to PPNPs led to sublethal morphological changes in hydra and PENPs had no effects. Both plastic materials were able to elicit changes in the expression of genes involved in oxidative stress, DNA repair activity, dopamine metabolisms and cell repair in dopaminergic neurons, protein-ubiquitin pathways (autophagy) and cell differention. The severity of the responses were greater with PPNPs leading to sublethal toxicity compared to PENPs. The following genes followed a biphasic response with increased gene expression at low concentrations: SOD (PENPs) and DDC (PPNPs). CAT expression was repressed at low concentrations but was significantly increased at the highest concentration (10 mg/L) for bith PENPs and PPNPs. It is concluded that these plastic nanoparticles could produced oxidative stress, decreased DNA repair and protein salvaging leading to altered circadian rhythms at environmentally relevant concentrations in urban area.

Supplementary Material

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Canadian plastic initiative of Environment and Climate Change Canada. The helpful assistance of Maxime Gauthier for the extraction of RNA, production of cDNA for qPCR reaction is noted.

References

- Acar U, İnanan BE, Zemheri-Navruz F 2024. Ecotoxicological effects of polystyrene nanoplastics on common carp: Insights into blood parameters, DNA damage, and gene expression. J Appl Toxicol 44, 1416-1425. [CrossRef]

- André C, Smyth SA, Gagné F. The peroxidase toxicity assay for the rapid evaluation of municipal effluent quality. Water Emerg Contam Nanoplastic, In press.

- Antunes JC de S, Sobral P, Branco V, Martins M 2025. Uncovering layer by layer the risk of nanoplastics to the environment and human health. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 28, 63-121. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2024.2424156.

- Argeswara J, Hendrawan IG, Dharma IGBS, Germanov E 2021. What's in the soup? Visual characterization and polymer analysis of microplastics from an Indonesian manta ray feeding ground. Mar Pollut Bull 168, 112427. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112427.

- Atugoda, T., H. Piyumali, H. Wijesekara, C. Sonne, S. S. Lam, K. Mahatantila, and M. Vithanage. 2023. Nanoplastic Occurrence, Transformation and Toxicity: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 21, 363–381. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01479-w.

- Au SY, Bruce TF, Bridges WC, Klaine SJ 2015. Responses of Hyallela azteca to acute and chronic microplastic exposures. Environ Toxicol Chem 34, 2564–2572.

- Auclair J, André C, Roubeau-Dumont E, Gagné F. 2024a. Ecotoxicity of a Representative Urban Mixture of Rare Earth Elements to Hydra vulgaris. Toxics 12, 904. [CrossRef]

- Auclair J, Roubeau-Dumont E, Gagné F 2024. Lethal and Sublethal Toxicity of Nanosilver and Carbon Nanotube Composites to Hydra vulgaris-A Toxicogenomic Approach. Nanomaterials (Basel) 14, 1955. [CrossRef]

- Auclair J , Quinn B, Peyrot C, Wilkinson KJ, Gagné F 2020. Detection, biophysical effects, and toxicity of polystyrene nanoparticles to the cnidarian Hydra attenuata. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 27, 11772-11781.

- Avio, C. G., S. Gorbi, and F. Regoli. 2017. Plastics and Microplastics in the Oceans: From Emerging Pollutants to Emerged Threat.” Mar Environ Res 128, 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Blaise C, Kusui T 1997. Acute toxicity assessment of industrial effluents with a microplate-based Hydra attenuata assay. Environ Toxicol Water Qual 12, 53–60.

- Blaise C., Gagné F., Harwood M., Quinn B. and H. H. 2018. Ecotoxicity responses of the freshwater cnidarian Hydra attenuata to 11 rare earth elements. Ecotoxicol and Environ Saf 163, 486-491.

- Cera A, Cesarini G, Spani F and M, Scalici 2020. Hydra vulgaris assay as environmental assessment tool for ecotoxicology in freshwaters: a review Marine and Freshwater Research 72, 745-753.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada 2020. Sublethal and lethal evaluation with the Hydra attenuata – Method for aqueous solutions. Q0404E2.

- Farley G, Bouchard P, Faille C, Trottier S, Gagné F. 2024. Towards the standardization of Hydra vulgaris bioassay for toxicity assessments of liquid samples. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 290, 117560. [CrossRef]

- Finney DJ 1964. Statistical method in biological assay. Hafner Publishing Company, 668 pages.

- Gagné F, Smyth SA, André C. 2024. Plastic Contamination and Water Quality Assessment of Urban Wastewaters. J Environ Toxicol Res 1, 14.

- Gagné F, Auclair J, Turcotte P, Gagnon C 2013. Sublethal effects of silver nanoparticles and dissolved silver in freshwater mussels. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2013;76(8):479-90. [CrossRef]

- Junaid M, Liu S, Liao H, Yue Q, Wang J 2024.Environmental nanoplastics quantification by pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in the Pearl River, China: First insights into spatiotemporal distributions, compositions, sources and risks. J Hazard Mater. 2024 Sep 5:476:135055. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.135055.

- Hara J, Vercauteren M, Schoenaers S, Janssen CR, Blust R, Asselman J, Town RM 2024. Differential sensitivity of hemocyte subpopulations (Mytilus edulis) to aged polyethylene terephthalate micro- and nanoplastic particles. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 286, 117255. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117255.

- Hoffmann U, Kroiher M 2001. A Possible Role for the Cnidarian Homologue of Serum Response Factor in Decision Making by Undifferentiated Cells, Dev Biol 236, 304-315.

- Islam MS , Gupta I, Xia L, Pitchai A, Shannahan J, Mitra S 2024. Generation of Eroded Nanoplastics from Domestic Wastes and Their Impact on Macrophage Cell Viability and Gene Expression. Molecules 29, 2033. doi: 10.3390/molecules29092033.

- Jeyavani J, Sibiya A, Bhavaniramya S, Mahboob S, Al-Ghanim KA, Nisa Z-U, Riaz MN, Nicoletti M, Govindarajan M, Vaseeharan B 2022. Toxicity evaluation of polypropylene microplastic on marine microcrustacean Artemia salina: An analysis of implications and vulnerability. Chemosphere 2022 Jun:296:133990. [CrossRef]

- Kaluç N, Çötelli EL, Tuncay S , Thomas PB 2024. Polyethylene terephthalate nanoplastics cause oxidative stress induced cell death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng 59, 180-188. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2024.2345026.

- Kanaya HJ , Park S, Kim J-H, Kusumi J, Krenenou S, Sawatari E, Sato A, Lee J, Bang H, Kobayakawa Y, Lim C, Itoh TQ 2020. A sleep-like state in Hydra unravels conserved sleep mechanisms during the evolutionary development of the central nervous system. Sci Adv 6: eabb9415. [CrossRef]

- Ma L, Wu Z, Lu Z, Yan L, Dong X, Dai Z , Sun R, Hong P, Zhou C, Li C 2024. Differences in toxicity induced by the various polymer types of nanoplastics on HepG2 cells. Sci Total Environ 918:170664. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170664.

- OECD. 2022. Global Plastics Outlook - Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options 2022. OECD. [CrossRef]

- Omond SET, Hale MW, Lesku JA 2022. Neurotransmitters of sleep and wakefulness in flatworms. Sleep 45, zsac053.

- Plastics Europe. 2023. Plastics - the Fast Facts 2023. Plastic Europe.

- Sarasamma S , Audira G, Siregar P, Malhotra N, Lai Y-H, Liang S-T, Chen JR, Chen KH-C, Hsiao CD 2020. Nanoplastics Cause Neurobehavioral Impairments, Reproductive and Oxidative Damages, and Biomarker Responses in Zebrafish: Throwing up Alarms of Wide Spread Health Risk of Exposure. Int J Mol Sci 21, 1410. [CrossRef]

- Schiavo S, Oliviero M, Chiavarini S, Dumontet S, Manzo S 2021. Polyethylene, Polystyrene, and Polypropylene leachate impact upon marine microalgae Dunaliella tertiolecta. J Toxicol Environ Health A 84, 249-260. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2020.1860173.

- Zimmermann L, Dierkes G, Ternes TA, Völker C, Wagner M 2019. Benchmarking the in Vitro Toxicity and Chemical Composition of Plastic Consumer Products. Environ Sci Technol 53, 11467-11477. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).