1. Introduction

Microplastics (MPs), plastic particles smaller than 5 mm [

1], have emerged as significant environmental pollutants, particularly in aquatic ecosystems. MPs originate from diverse sources, including urban runoff, wastewater discharges and agricultural practices [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The presence of MPs in freshwater environments poses significant threats to various organisms, including

Daphnia magna, a widely used model organism in ecotoxicological research due to the ecological importance and sensitivity to environmental changes [

7,

8].

D. magna is particularly vulnerable to MPs because it filter-feed on microalgae and other small particles [

9,

10]. The ingestion of MPs can adversely affect feeding efficiency, digestion, growth, reproduction, and survival of

D. magna populations [

11,

12,

13,

14], potentially impacting population dynamics and community structures in aquatic ecosystems [

9,

15]. These observations highlight the urgent need to investigate the underlying biological mechanisms driving the effects [

9,

16,

17,

18].

While the physiological and individual-level effects of MPs are increasingly well-documented [

14], knowledge about their molecular impacts, particularly on gene expression and epigenetic modifications, remains limited. Emerging evidence suggests that MPs may influence the epigenetic landscape of

D. magna. Recent studies have begun investigating the role of DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in response to environmental stressors, including MPs exposure [

18,

19,

20].

Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, can regulate gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence, potentially leading to adaptive or maladaptive stress responses to environmental pollutants [

21,

22,

23]. Examining global DNA methylation (5-mC) and hydroxymethylation (5-hmC) in

D. magna exposed to MPs could reveal how these pollutants induce epigenetic changes that affect gene expression and compromise organismal health and fitness [

24,

25]. Moreover, such epigenetic modifications are increasingly recognized as sensitive biomarkers of environmental stress, aiding in the assessment of MPs impact on aquatic organisms [

26,

27].

This study investigates the epigenetic and gene expression responses of D. magna to polyethylene (PE) and polystyrene (PS) MP exposure, focusing on global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation, as well as stress- and development-related gene expression. The findings aim to provide novel insights into the molecular mechanisms of MP pollution effects, enhancing understanding of MPs' ecotoxicological impacts and informing future conservation and management strategies.

2. Results

2.1. Microplastic Ingestion by D. magna

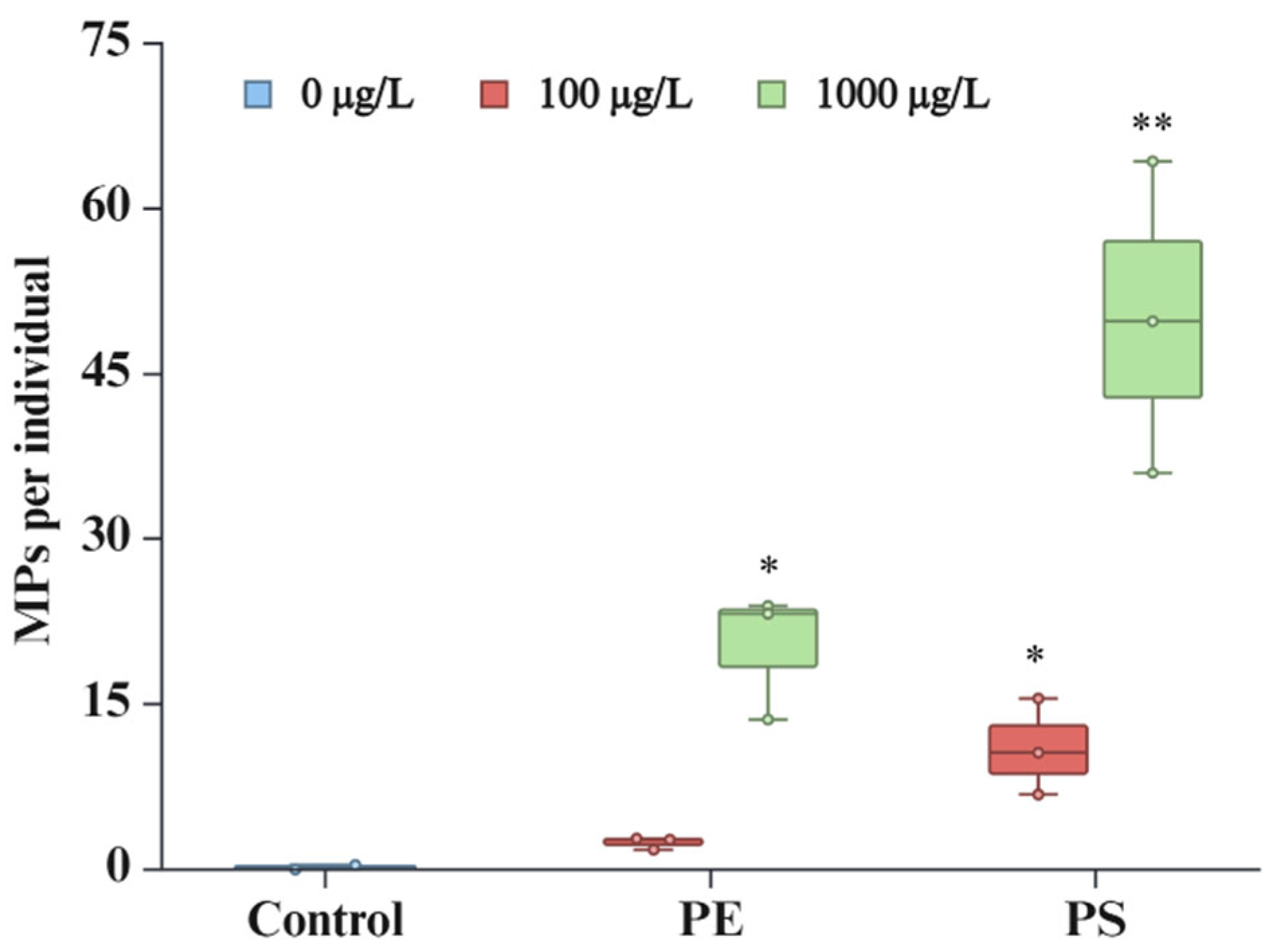

Microplastic ingestion by

D. magna was systematically assessed under varying concentrations of PE and PS particles (

Figure 1). Under control conditions, minimal ingestion was observed, with an average of 0.18 particles per individual, indicative of baseline contamination. Exposure to 100 µg/L of PE resulted in a marked increase in ingestion rates, with an average of 2.44 particles per individual. This rate escalated significantly at a higher concentration of 1000 µg/L PE, reaching 20.24 particles per individual. A similar trend was observed for PS exposure: at 100 µg/L, the average ingestion rate was 11.03 particles per individual, which increased dramatically at 1000 µg/L, peaking at 50.03 particles per individual.

These findings underline a clear concentration-dependent accumulation of MPs by

D. magna, with ingestion rates significantly increasing at higher concentrations of both PE and PS particles. Similar with our results, previous studies have also reported an increase in MPs accumulation in

D. magna with increasing concentration of MPs [

28,

29,

30,

31]. A notable observation is the higher ingestion rate of PS particles compared to PE particles under the same concentration conditions. This tendency may be attributed to differences in the physiochemical properties of PE and PS, which could influence the interaction between particles and

D. magna. These findings underscore the need for further research into the role of MPs material properties in determining ingestion and accumulation dynamics in aquatic organisms.

The density of PS MPs, approximately 1.05 g/cm³ [

32] is notably higher than that of PE MPs, which ranges from 0.88 to 0.96 g/cm³ [

33]. This difference allows PS MPs to remain suspended in the water column, whereas PE MPs are more prone to floating on the water surface. The buoyancy disparity influences the likelihood of ingestion, as

D. magna, which primarily feed below the water surface, are more likely to encounter suspended PS particles [

13,

17]. Similarly, Luangrath et al. (2024) observed higher bioconcentration of polylactic acid (PLA) MPs (1.24 g/cm³) compared to PE MPs (0.95 g/cm³) in

D. magna exposed to MPs [

30].

In addition, PS MPs exhibit a stronger tendency to aggregate, a characteristic attributed to their hydrophobic nature and capacity to form strong interactions with organic matter and microorganisms in the marine environment [

34,

35,

36]. This aggregation leads to the formation of larger clusters , increasing the likelihood of encounter and ingestion by filter feeders like

Daphnia [

37]. Moreover, the interaction of MPs with organic matter enhances the bioavailability as the adsorption of nutrients and the development of biofilms on MPs make them more attractive to the filter feeders. [

17,

31,

38]. In contrast, PE MPs typically remain as smaller, less aggregated particles, which may reduce their likelihood of being consumed by

D. magna [

39,

40].

Despite regular stirring of the medium during the exposure experiments (every 8h) to ensure an even distribution of particles, the physiochemical characteristics of the MPs differentially affected their ingestion by D. magna.

2.2. Epigenetic Responses to Microplastic Exposure in D. magna

Global DNA methylation (5-mC) and DNA hydroxymethylation (5-hmC) are pivotal epigenetic modifications involved in regulating gene expression, mediating cellular stress responses, and facilitating adaptation to environmental changes [

41,

42]. These epigenetic markers have been linked to various environmental exposures, including heavy metals such as lead, antimony, and arsenic [

43,

44], airborne particulate matter (PM10) [

45], and crude oil spills [

46]. In this study, 5-mC and 5-hmC levels were analyzed to evaluate the epigenetic responses of

D. magna to MP exposure. The ability of

D. magna to reproduce asexually make it an invaluable model for studying epigenetic dynamics [

47,

48].

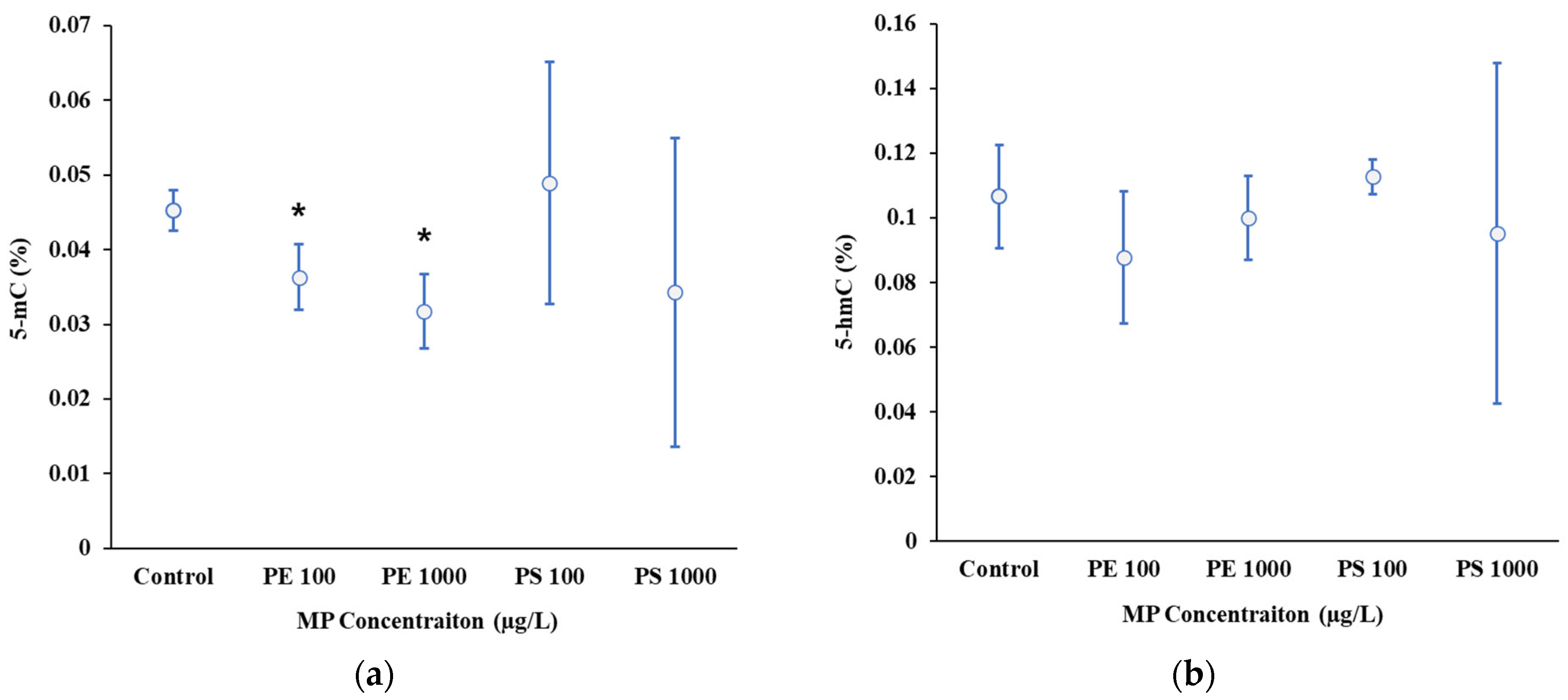

The results in this study indicate that exposure to MPs, specifically PE and PS, resulted in changes in DNA methylation levels in

D. magna. Significant decreases in DNA methylation were observed at higher concentrations of PE (100 and 1000 µg/L), indicative of a hypomethylation response (

Figure 2a). These finding contrast with the study of Song et al. (2022), which demonstrated no significant changes in global DNA methylation in

D. magna exposed to PE fragments (16.68 ± 7.04 µm; 4.35 mg/L).

A decrease in DNA methylation, or hypomethylation, is commonly associated with increased gene expression and activation of stress response pathways (Athanasio et al., 2018). The hypomethylation observed in

D. magna exposed to PE MPs may reflect a stress response mechanism. Similar epigenetic changes have been reported in response to environmental pollutants like heavy metals, where global DNA methylation decreases as organisms reallocate resources to cope with stress, potentially at the expense of growth and reproduction [

21,

50,

51].

The interplay between DNA methylation and oxidative stress is critical for understanding the biological impact of MPs. Oxidative stress, induced by MPs, can influence DNA methylation patterns as a cellular response to environmental stressors. Tang et al. (2019) demonstrated that PE MPs upregulate genes involved in oxidative defense mechanisms, such as thioredoxin reductase (TRxR), which play a critical role in mitigating reactive oxygen species (ROS). This oxidative stress may contribute to the observed hypomethylation in

D. magna exposed to PE MPs [

53].

In contrast to PE, exposure to PS MP particles at both 100 and 1000 µg/L did not result in significant changes in DNA methylation levels in this study (

Figure 2a). This lack of significant change may result from a counterbalance between hyper- and hypomethylation, as suggested by Jeremias et al. 2018 [

22].

Environmental stressors like MP exposure can induce transgenerational changes in

D. magna, potentially affecting the resilience of subsequent generations to future environmental challenges. For instance, Jeremias et al. (2018) [

22] demonstrated that salinity stress -induced hypomethylation in DNA could be inherited by offspring. Similarly, MPs may influence DNA methylation patterns that affect

D. magna's ability to adapt and survive in polluted environments [

18].

DNA hydroxymethylation, a distinct epigenetic modification implicated in gene regulation, showed notable variability in the PS 1000 µg/L [

54] (

Figure 2b). While not statistically significant, this increased variability suggests potential effects of high PS concentrations on hydroxymethylation patterns. Further investigation is warranted to validate these trends and address experimental variability [

55,

56].

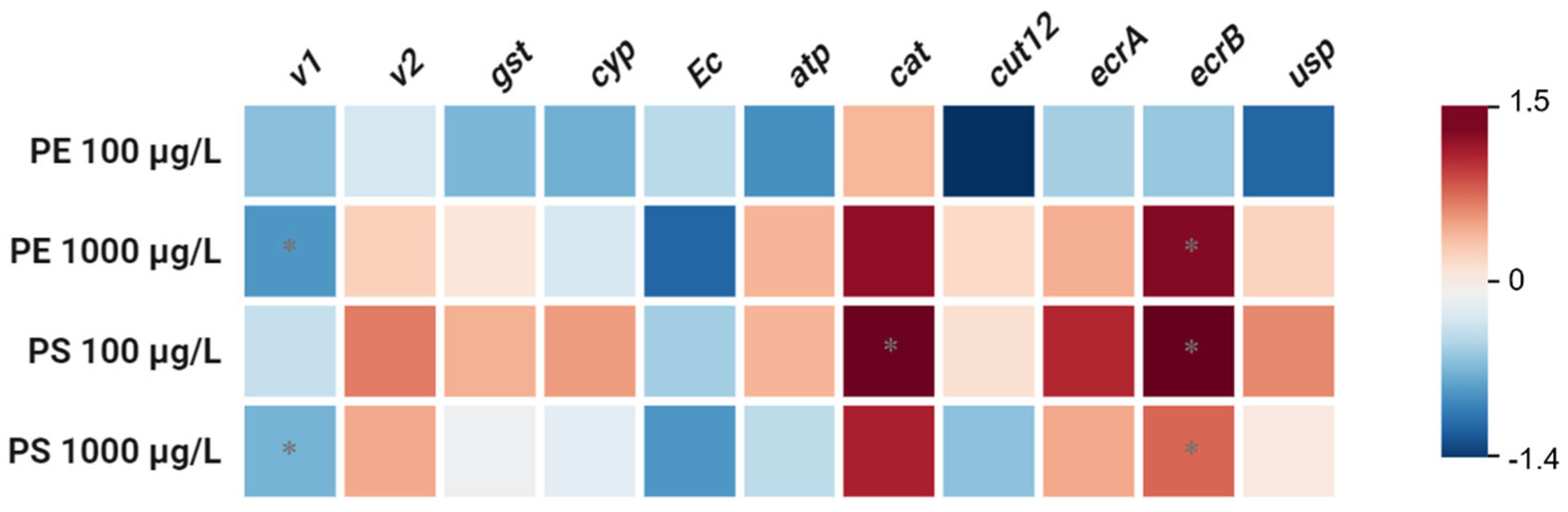

2.3. Transcriptional Response to MP Exposure in D. magna

To elucidate the biological impact of MP exposure, we assessed the transcriptional responses of a panel of genes (

v1, v2, gst, cyp, atp, cat, cut12, ecr-b, usp). Significant downregulation of

v1 and upregulation of

ecr-b were observed in

D. magna exposed to high concentrations of both PE and PS MPs (1000 µg/L;

P < 0.05) (

Figure 3). These transcriptional changes are indicative of a stress response associated with the presence of high concentrations of MP particles.

The downregulation of the

v1 gene suggests a potential stress response mechanism triggered by MP exposure. The

v1 gene is noteworthy, as it is associated with physiological processes such as growth, development, and metabolic pathways regulating vitellogenin (Vtg) synthesis, which is a precursor to yolk proteins critical for reproduction. This downregulation suggest that

D. magna may be reallocating resources from reproductive functions to cope with the stress induced by MP exposure. This resource reallocation aligns with the observed decrease in DNA methylation, further supporting the hypothesis of a stress-response mechanism prioritizing survival over growth and reproduction [

51].

The upregulation of the

ecr-b gene, which is involved in ecdysone receptor signaling pathways, suggests a potential adaptation or compensatory mechanism in response to MP exposure. Molting, a pivotal process in crustacean growth, is predominantly regulated by the ecdysteroids, with the cytochrome P450 subfamily member Cyp314 playing a critical role in synthesizing the molting hormone ecdysone. This hormone is subsequently converted into its active form, 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E), which is regulated by the ecdysone receptor,

ecr-b. The ecr-b gene plays a crucial role in crustacean development, including molting and adaptation to environmental stressors [

57]. The upregulation of

ecr-b observed in MP-exposed groups suggests an adaptive response aimed at enhancing resilience to MP-induced stress. This response aligns with the critical role of

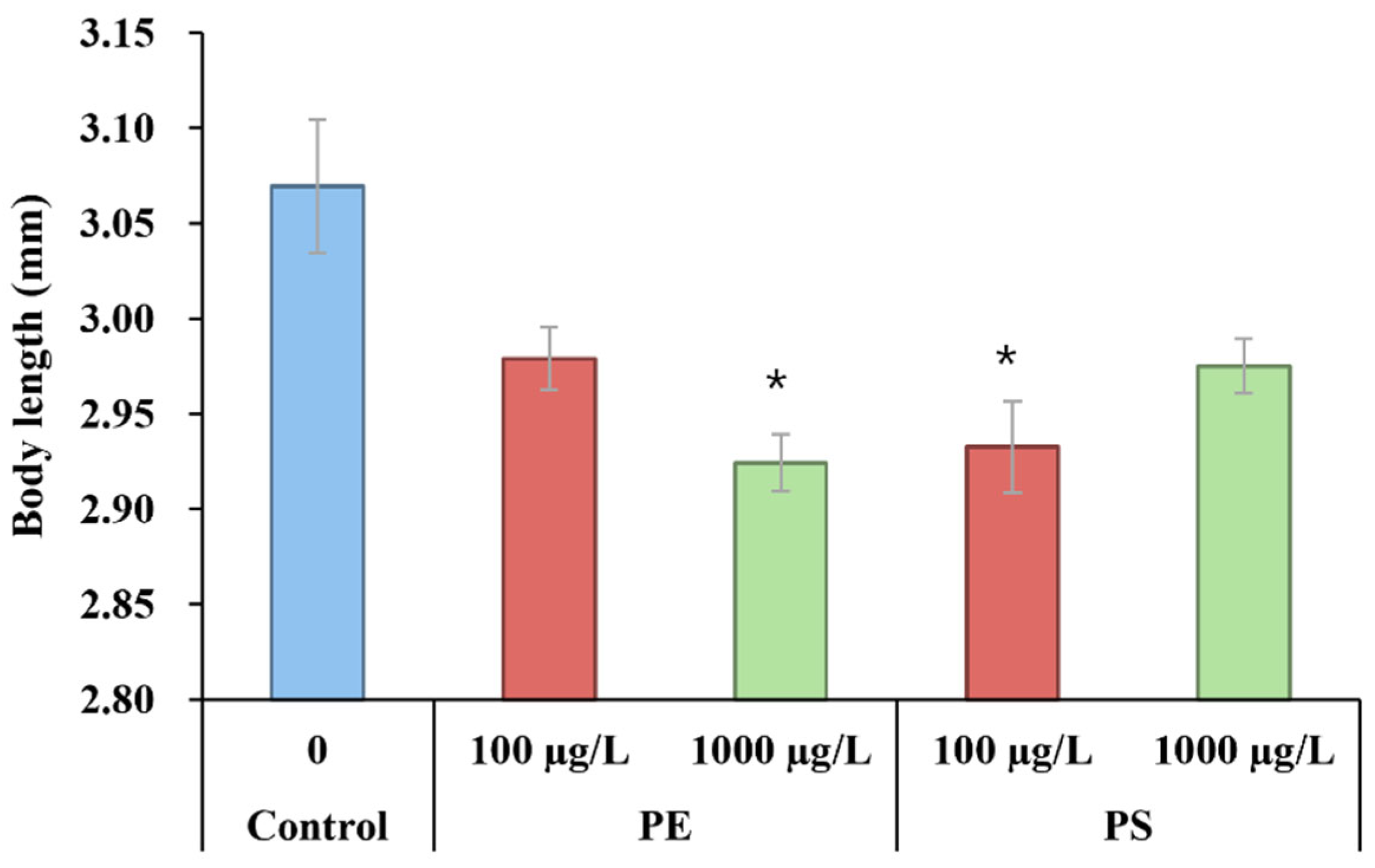

ecr-b in facilitating molting and stress adaptation. However, despite this upregulation, body length in MP-exposed groups—particularly in the PE 1000 µg/L and PS 100 µg/L groups—was significantly reduced (

Figure 4). This discrepancy indicates that while

ecr-b upregulation may support molting and stress resilience, the inability of

D. magna to allocate sufficient resources for growth under MP-induced stress results in smaller body size. Resource reallocation may prioritize survival and stress adaptation mechanisms over growth, as observed in previous studies on stress responses in aquatic organisms [

58]. In addition, Genes like

cut12, responsive to 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E), are responsible for producing cuticle proteins essential for the formation of the new exoskeleton [

59], but did not show significant changes in the expression. This lack of significant change in cut12 expression suggests that while the molting process is partially supported by

ecr-b upregulation, other factors or gene expressions critical for exoskeleton development may remain unaffected, potentially limiting the organism's growth and structural integrity.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Microplastic Ingestion by D. magna

To evaluate the effects of MPs on D. magna, each experimental vessels were each stocked with 25 neonates less than 24 hours old, with experiments conducted in triplicate. D. magna were exposed to two concentrations of PE and PS MPs (100 µg/L and 1000 µg/L) over a 7-day period. A control group, free of MPs exposure, was included for comparison. Each vessel contained 500 mL of M4 medium, which was refreshed every 48 hrs to maintain optimal water quality. The vessels were gently stirred every 8 hrs to ensure uniform suspension of MP particles.

Chlorella vulgaris (a freshwater alga provided by Aquanet, South Korea) was daily added at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells mL-1 to provide a consistent food source.

After the exposure period, seven D. magna individuals per replicate were collected for mRNA extraction, and another seven were used to measure global DNA methylation (5-hmC) and hydroxymethylation (5-hmC) levels. All samples were immediately frozen at -80 °C for subsequent molecular analysis. These stored samples were used to analyze gene expression and investigate epigenetic changes in D. magna. The expression levels of genes involved in stress response and development were measured to assess the impact of MPs exposure on D. magna at the molecular level. Gene expression levels were measured for genes involved in stress response and development, including Vitellogenin 1 (v1), Vitellogenin 2 (v2), Glutathione-S-Transferase (gst), Cytochrome P450 (cyp), ATPase Na+/K+ (atp), Catalase (cat), Cuticle Protein 12 (cut12), Ecdysone Receptor B (ecr-b), and Universal Stress Protein (usp). Remaining organisms were used for body length measurements and stored at -20 °C for MP ingestion analysis.

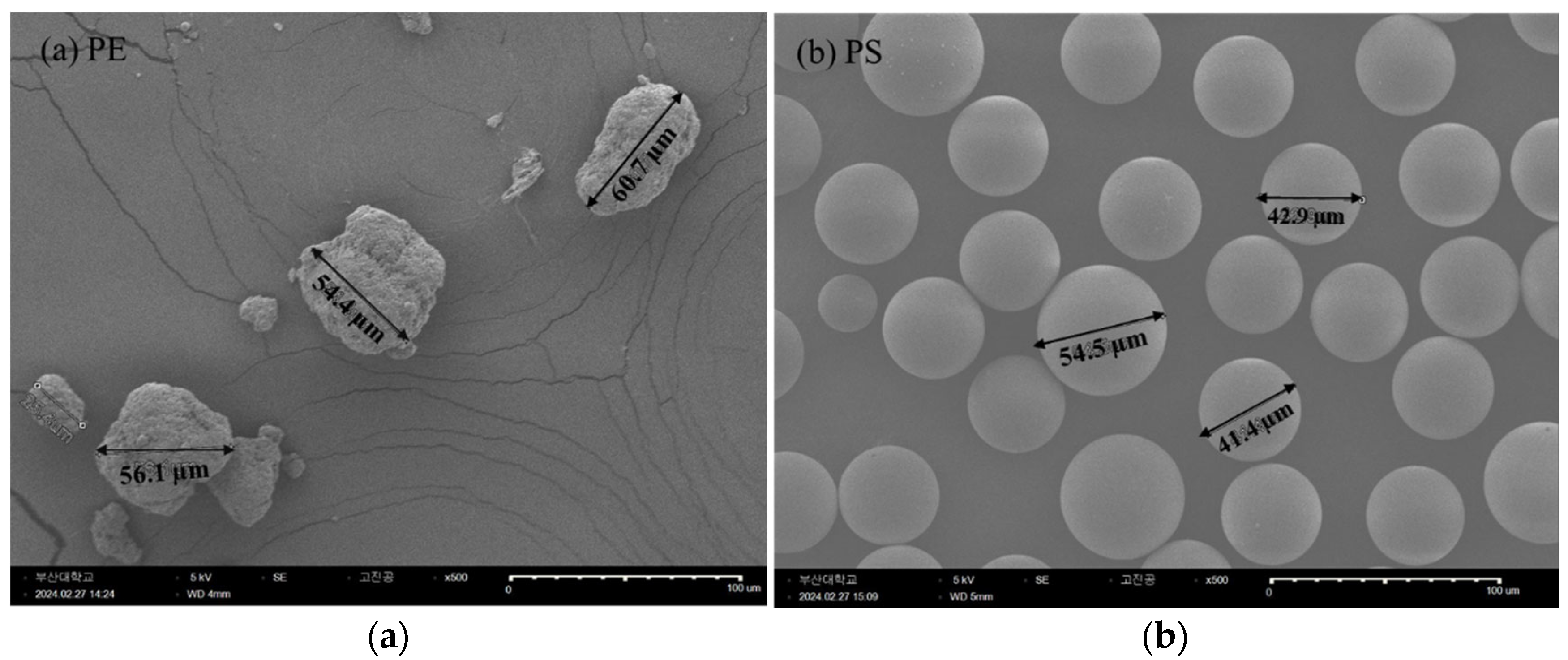

Standard pristine PE and PS MPs were selected to investigate the polymer-specific effects of MPs. Both types of MPs were chosen to have similar physical characteristics to minimize variability attributed to shape (refer to

Figure 5). PE MPs, with a mean particle size of 40−48 µm, were procured from Sigma Aldrich (CAS No. 9002-88-74), while PS MPs, with a mean particle size of 38−48 µm were sourced from the Korea Institute of Analytical Science. Zeta potential (mV) of the MPs was measured using a Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) analyzer (Zetasizer Nano ZSP, Malvern, England) to characterize their surface charge. This systematic approach ensured consistency across experiments and allowed for robust analysis of the effects of PE and PS MPs on

D. magna at molecular, physiological, and behavioral levels

3.2. Test Organisms

The D. magna test clones used in this study were provided by the Korea Institute of Toxicology (KIT), South Korea, in 2021 for research purposes. The daphnids were cultured under controlled conditions of a 16-hrs light and 8-hrs dark cycle at a temperature of 20 ± 1 °C, in accordance with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Test Guideline 211 (OECD, 2012). The organisms were maintained in Elendt M4 medium, with a pH of 7.8 ± 0.2 and water hardness of 250 ± 30 mg L-1 CaCO3. Chronic exposure experiments were conducted using third-brood female neonates, all of which were less than 24 hrs old at the time of exposure.

3.3. Gene Expression Analysis (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from D. magna whole-body tissue samples utilizing the Total RNA Kit (Cosmogenegech co, Ltd., South Korea). RNA quantity and quality were assessed with a Nano-drop spectrophotometer. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was perfomred using M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (Cosmogenegech co, Ltd., South Korea), followed by PCR amplification using a Bio-Rad thermal cycler. Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was conducted on an AriaMx Real-time PCR System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) with the EvaGreen Q Master mix (Cosmogenegech co, Ltd., South Korea). Primers were designed using Primer3plus (refer to Table 1) and based on sequences obtained from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. Primer sets were synthesized by Cosmogenetech (Seoul, South Korea) and optimized for qRT-PCR conditions to ensure high efficiency and sensitivity. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and mean values were calculated. Control reactions, including those without RT and template, were included to rule out DNA contamination. The housekeeping reference gene β-Actin was utilized for normalization of gene expression levels.

3.4. Global DNA methylation (5-mc) and DNA hydroxymethylation (5-hmc) Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the whole-body tissues of D. magna using the LaboPass™ Tissue Genomic DNA Isolation Kit Mini (Cosmogenegech co, Ltd., South Korea). DNA integrity and concentration were evaluated using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. Global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation levels were assessed using the MethylFlash Global DNA Methylation (5-mC) ELISA Easy Kit and the MethylFlash Global DNA Hydroxymethylation (5-hmC) ELISA Easy Kit (Colorimetric), following the manufacturer's protocols (Epigentek Group Inc., NY, USA). In brief, 1–8 μL of DNA (equivalent to 100 ng) was introduced into the assay wells. The DNA was then incubated at 37 °C for a period of 90 minCapture and detection antibodies were subsequently applied, and absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm. A standard curve was created using the optical density (OD) values of positive samples, allowing quantification of methylation and hydroxymethylation levels.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA). Homogeneity of variances and normality of data were evaluated using Levene’s test and the Shapiro-Wilk test, respectively, at a significance level of p < 0.05. Differences among multiple treatment groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). For comparisons between two groups, Student’s t-test was employed to assess statistical significance (p < 0.05).

3.6. Microplastic Ingestion by D. magna

3.6.1. Sample Preparation

To identify and quantify MPs accumulated in D. magna, 8-11 of individuals were collected per condition. The collected organisms were stored in a freezer, upon to the sample preparation of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis. To isolate MPs ingested and accumulated by D. manga, the samples were digested using a 30% H2O2 solution at 60 °C to remove organic matter. The digested samples were filtered through Anodisc filters (Al2O3, pore size 200 µm) using a vacuum infiltration device. The filters were stored in a desiccator to remove residual moisture prior to FTIR analysis.

3.6.2. Micro-FTIR Analysis

Identification and enumeration of the MPs collected on the 25 mm Anodisc filter (Al2O3, 0.2 µm pore size, Whatman) were conducted using µ-FTIR spectroscopy (Nicolet iN10MX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, US), following previously established. Chemical image mapping was used to automatically generate spectral information by scanning 16 sectors of the filter area simultaneously. The analysis covered a wavelength range of 1300–4000 cm⁻¹, with a collection time of 3 seconds (16 scans), an aperture size of 60 × 60 µm, and a resolution of 8. Spectra were acquired from the entire area of a 25 mm Anodisc filter where MPs were collected. A background spectrum of the pristine Anodisc filter was collected at the reference position of the sample holder. Analysis was performed on a quarter of the filter area individually, and the data from all four quarters were summed up to present MPs amount in the corresponding sample. The acquired spectra from the entire area of Anodisc filter were correlated with MPs reference spectra in the library (e.g., PE and PS), with each being presented with a false-color image based on the matching hierarchy to the corresponding reference spectrum. After examining individual IR spectrum of the particles with false-color images, particles meeting both the criteria of having a representative IR peak of the reference and over a 65% matching rate to the reference, were identified and counted as MPs.

The limit of the detection (LOD) for particle size in micro-FTIR is 20 µm, due to the limit of lateral resolution of the IR source. The limit of the quantity (LOQ) of the micro-FTIR is determined by optimal condition for counting MPs particle on one filter and the distribution of particles deposited on the filter. Manual counting becomes challenging for particle numbers exceeding a few hundred. Thus, the LOQ is few hundred particles per filter.

Contamination of MPs in chemicals, filters and other lab consumables were minimized by using glassware for sample storage. Regular blank tests were conducted during the experiment, confirming the absence of MPs.

4. Conclusions

This study highlights the profound impact of MPs pollution, specifically PE and PS, on freshwater zooplankton D. magna, demonstrating the potential of MPs to disrupt physiological, epigenetic, and transcriptional processes. MP ingestion showed concentration-dependent pattern, with PS particles accumulating at higher rates, likely due to the physicochemical properties such as density and aggregation behavior. Epigenetic analyses revealed significant reductions in global DNA methylation levels in response to PE exposure, suggesting hypomethylation as a stress response. Although no consistent changes in DNA hydroxymethylation were observed, the variability seen in PS-exposed groups warrants potential effects that merit further investigation. Transcriptional analysis underscored the complex molecular responses to MP exposure, with the downregulation of the v1 gene, associated with compromised reproductive capacity, and the upregulation of ecr-b, linked to molting and stress adaptation. These responses reflect adaptive mechanisms employed by D. magna to cope with environmental stressors. However, despite these adaptations, the observed reduction in body size across MP-exposed groups underscores a resource trade-off that may ultimately compromise organismal fitness.

Overall, the study highlights the intricate interplay between microplastic exposure, epigenetic alterations, and gene regulation in aquatic organisms. These findings highlight the pressing need for further research to elucidate the long-term and transgenerational effects of MPs, alongside robust efforts to mitigate plastic pollution and its ecological consequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Im.; methodology, H.Im. and J.Lee.; data curation, J.Lee.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Im.; writing—review and editing, J.Lee., J.Oh., S.Jeong. and J.Song.; supervision, S.Jeong.; funding acquisition, J.Oh. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Programs through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1A6A1A03039572 and NRF-2022R1I1A1A01065515).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Programs through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1A6A1A03039572 and NRF-2022R1I1A1A01065515).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MP |

Microplastic particle |

| PE |

polyethylene |

| PS |

polystyrene |

| TRxR |

Thioredoxin reductase |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscope |

| RT-PCR |

Real-time PCR |

| DLS |

Dynamic Light Scattering |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

References

- Dekiff, J.H.; Remy, D.; Klasmeier, J.; Fries, E. Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Microplastics in Sediments from Norderney. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 186, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, A.K.; Corsi, S.R.; Mason, S.A. Plastic Debris in 29 Great Lakes Tributaries: Relations to Watershed Attributes and Hydrology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10377–10385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, A.R.; Chadwick, D.D.A.; Eagle, L.J.B.; Gould, A.N.; Harwood, M.; Sayer, C.D.; Rose, N.L. Microplastic Burden in Invasive Signal Crayfish (Pacifastacus Leniusculus) Increases along a Stream Urbanization Gradient. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.; Bose, K. Microplastics: An Overview on Ecosystem and Human Health. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2024, 3691–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liao, H.; Wei, M.; Junaid, M.; Chen, G.; Wang, J. Biological Uptake, Distribution and Toxicity of Micro(Nano)Plastics in the Aquatic Biota: A Special Emphasis on Size-Dependent Impacts. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, T.; Johnson, M.; Nathanail, P.; MacNaughtan, W.; Gomes, R.L. Freshwater Microplastic Concentrations Vary through Both Space and Time. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricant, L.; Edelstein, O.; Dispigno, J.; Weseley, A. The Effect of Microplastics on the Speed, Mortality Rate, and Swimming Patterns of Daphnia Magna. J. Emerg. Investig. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cui, Y.; Wen, M.; Ji, G. Toxic Effects of Methylene Blue on the Growth, Reproduction and Physiology of Daphnia Magna. Toxics 2023, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaibachi, R.; Callaghan, A. Impact of Polystyrene Microplastics on Daphnia Magna Mortality and Reproduction in Relation to Food Availability. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canniff, P.M.; Hoang, T.C. Microplastic Ingestion by Daphnia Magna and Its Enhancement on Algal Growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemec, A.; Horvat, P.; Kunej, U.; Bele, M.; Kržan, A. Uptake and Effects of Microplastic Textile Fibers on Freshwater Crustacean Daphnia Magna. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.; Guilhermino, L. Transgenerational Effects and Recovery of Microplastics Exposure in Model Populations of the Freshwater Cladoceran Daphnia Magna Straus. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rist, S.; Baun, A.; Hartmann, N.B. Ingestion of Micro- and Nanoplastics in Daphnia Magna – Quantification of Body Burdens and Assessment of Feeding Rates and Reproduction. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 228, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Long, Y.; Xiao, W.; Liu, D.; Tian, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y. Ecotoxicology of Microplastics in Daphnia: A Review Focusing on Microplastic Properties and Multiscale Attributes of Daphnia. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlino, M.; Sarà, G.; Mangano, M.C. Functional Trait-Based Evidence of Microplastic Effects on Aquatic Species. Biology 2023, 12, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Na, J.; Song, J.; Jung, J. Size-Dependent Chronic Toxicity of Fragmented Polyethylene Microplastics to Daphnia Magna. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isinibilir, M.; Eryalçın, K.M.; Kideys, A.E. Effect of Polystyrene Microplastics in Different Diet Combinations on Survival, Growth and Reproduction Rates of the Water Flea (Daphnia Magna). Microplastics 2023, 2, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Kim, C.; Na, J.; Sivri, N.; Samanta, P.; Jung, J. Transgenerational Effects of Polyethylene Microplastic Fragments Containing Benzophenone-3 Additive in Daphnia Magna. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Guan, Z.; Jiang, L.; Tang, K. The Impact of Microplastic Pollution on Ecological Environment: A Review. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2022, 27, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strepetkaitė, D.; Alzbutas, G.; Astromskas, E.; Lagunavičius, A.; Sabaliauskaitė, R.; Arbačiauskas, K.; Lazutka, J. Analysis of DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation in the Genome of Crustacean Daphnia Pulex. Genes 2016, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Kang, J.; Jacob, M.F.; Bae, H.; Oh, J.-E. Transgenerational Effects of Benzotriazole on the Gene Expression, Growth, and Reproduction of Daphnia Magna. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 323, 121211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeremias, G.; Barbosa, J.; Marques, S.M.; De Schamphelaere, K.A.C.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.; Deforce, D.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Pereira, J.L.; Asselman, J. Transgenerational Inheritance of DNA Hypomethylation in Daphnia Magna in Response to Salinity Stress. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 10114–10123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litoff, E.J.; Garriott, T.E.; Ginjupalli, G.K.; Butler, L.; Gay, C.; Scott, K.; Baldwin, W.S. Annotation of the Daphnia Magna Nuclear Receptors: Comparison to Daphnia Pulex. Gene 2014, 552, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asselman, J.; De Coninck, D.I.M.; Vandegehuchte, M.B.; Jansen, M.; Decaestecker, E.; De Meester, L.; Vanden Bussche, J.; Vanhaecke, L.; Janssen, C.R.; De Schamphelaere, K.A.C. Global Cytosine Methylation in Daphnia Magna Depends on Genotype, Environment, and Their Interaction. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, J.; Gonçalves Athanàsio, C.; Shams Solari, O.; Brown, J.B.; Colbourne, J.K.; Pfrender, M.E.; Mirbahai, L. Pattern of DNA Methylation in Daphnia: Evolutionary Perspective. Genome Biol. Evol. 2018, 10, 1988–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.H.; Marsit, C.J.; Kelsey, K.T. Global Methylation in Exposure Biology and Translational Medical Science. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Vieira, L.; Silva, M.J.; Ventura, C. The Effect of Nanomaterials on DNA Methylation: A Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, A.; Boardwine, A.J.; Hoang, T.C. Accumulation, Depuration, and Potential Effects of Environmentally Representative Microplastics towards Daphnia Magna. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, B.; Sabatini, V.; Antenucci, S.; Gattoni, G.; Santo, N.; Bacchetta, R.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Parolini, M. Polystyrene Microplastics Ingestion Induced Behavioral Effects to the Cladoceran Daphnia Magna. Chemosphere 2019, 231, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangrath, A.; Na, J.; Kalimuthu, P.; Song, J.; Kim, C.; Jung, J. Ecotoxicity of Polylactic Acid Microplastic Fragments to Daphnia Magna and the Effect of Ultraviolet Weathering. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 271, 115974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, C.; Brennholt, N.; Reifferscheid, G.; Wagner, M. Feeding Type and Development Drive the Ingestion of Microplastics by Freshwater Invertebrates. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidtmann, J.; Elagami, H.; S. Gilfedder, B.; H. Fleckenstein, J.; Papastavrou, G.; Mansfeld, U.; Peiffer, S. Heteroaggregation of PS Microplastic with Ferrihydrite Leads to Rapid Removal of Microplastic Particles from the Water Column. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2022, 24, 1782–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okutan, H.M.; Sağir, Ç.; Fontaine, C.; Nauleau, B.; Kurtulus, B.; Le Coustumer, P.; Razack, M. One-Dimensional Experimental Investigation of Polyethylene Microplastic Transport in a Homogeneous Saturated Medium. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Paul-Pont, I.; Hégaret, H.; Moriceau, B.; Lambert, C.; Huvet, A.; Soudant, P. Interactions between Polystyrene Microplastics and Marine Phytoplankton Lead to Species-Specific Hetero-Aggregation. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 228, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhon, E.G.; Mukhanov, V.S.; Khanaychenko, A.N. Phytoplankton Exopolymers Enhance Adhesion of Microplastic Particles to Submersed Surfaces</Strong>. Ecol. Montenegrina 2019, 23, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, S.; Henry, T.; Gutierrez, T. Agglomeration of Nano- and Microplastic Particles in Seawater by Autochthonous and de Novo-Produced Sources of Exopolymeric Substances. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 130, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, J.; Stippkugel, A.; Lenz, M.; Wirtz, K.; Engel, A. Rapid Aggregation of Biofilm-Covered Microplastics with Marine Biogenic Particles. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20181203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Md.A.; Shammi, M.; Tareq, S.M. The Deciphering of Microplastics-Derived Fluorescent Dissolved Organic Matter in Urban Lakes, Canals, and Rivers Using Parallel Factor Analysis Modeling and Mimic Experiment. Water Environ. Res. 2024, 96, e11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O.S.; Farner Budarz, J.; Hernandez, L.M.; Tufenkji, N. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Aquatic Environments: Aggregation, Deposition, and Enhanced Contaminant Transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1704–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frère, L.; Maignien, L.; Chalopin, M.; Huvet, A.; Rinnert, E.; Morrison, H.; Kerninon, S.; Cassone, A.-L.; Lambert, C.; Reveillaud, J.; et al. Microplastic Bacterial Communities in the Bay of Brest: Influence of Polymer Type and Size. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Fan, Y.; Zeng, H.; Liu, J.; Meng, H.; Bai, D.; Peng, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Tissue-Specific 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine Landscape of the Human Genome. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Gao, H. Hydroxymethylation and Tumors: Can 5-Hydroxymethylation Be Used as a Marker for Tumor Diagnosis and Treatment? Hum. Genomics 2020, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, Y.; Iwai-Shimada, M.; Nakai, K.; Tatsuta, N.; Mori, Y.; Aoki, A.; Kojima, N.; Takada, T.; Satoh, H.; Jinno, H. Global DNA Methylation in Cord Blood as a Biomarker for Prenatal Lead and Antimony Exposures. Toxics 2022, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellez-Plaza, M.; Tang, W.; Shang, Y.; Umans, J.G.; Francesconi, K.A.; Goessler, W.; Ledesma, M.; Leon, M.; Laclaustra, M.; Pollak, J.; et al. Association of Global DNA Methylation and Global DNA Hydroxymethylation with Metals and Other Exposures in Human Blood DNA Samples. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, M.; Pourpak, Z.; Naddafi, K.; Nodehi, R.N.; Nicknam, M.H.; Shamsipour, M.; Rezaei, S.; Ghozikali, M.G.; Ghanbarian, M.; Mesdaghinia, A. Effects of Airborne Particulate Matter (PM10) from Dust Storm and Thermal Inversion on Global DNA Methylation in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) in Vitro. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 195, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Jeong, J.; Park, M.-S.; Ha, M.; Cheong, H.-K.; Choi, J. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations between Global DNA (Hydroxy) Methylation and Exposure Biomarkers of the Hebei Spirit Oil Spill Cohort in Taean, Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiner, N.; Radersma, R.; Vasquez, L.; Ringnér, M.; Nystedt, B.; Raine, A.; Tobi, E.W.; Heijmans, B.T.; Uller, T. Environmentally Induced DNA Methylation Is Inherited across Generations in an Aquatic Keystone Species. iScience 2022, 25, 104303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, R.; Van Damme, K.; Gosálvez, J.; Morán, E.S.; Colbourne, J.K. Male Meiosis in Crustacea: Synapsis, Recombination, Epigenetics and Fertility in Daphnia Magna. Chromosoma 2016, 125, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasio, C.G.; Sommer, U.; Viant, M.R.; Chipman, J.K.; Mirbahai, L. Use of 5-Azacytidine in a Proof-of-Concept Study to Evaluate the Impact of Pre-Natal and Post-Natal Exposures, as Well as within Generation Persistent DNA Methylation Changes in Daphnia. Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macha, F.J.; Im, H.; Kim, K.; Park, K.; Oh, J.-E. Effect of Cresol Isomers on Reproduction and Gene Expression in Daphnia Magna. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 893, 164910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandegehuchte, M.B.; De Coninck, D.; Vandenbrouck, T.; De Coen, W.M.; Janssen, C.R. Gene Transcription Profiles, Global DNA Methylation and Potential Transgenerational Epigenetic Effects Related to Zn Exposure History in Daphnia Magna. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 3323–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Wang, X.; Yin, J.; Han, Y.; Yang, J.; Lu, X.; Xie, T.; Akbar, S.; Lyu, K.; Yang, Z. Molecular Characterization of Thioredoxin Reductase in Waterflea Daphnia Magna and Its Expression Regulation by Polystyrene Microplastics. Aquat. Toxicol. 2019, 208, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.D.; Matsuura, T.; Kato, Y.; Watanabe, H. Caloric Restriction Upregulates the Expression of DNMT3.1, Lacking the Conserved Catalytic Domain, In. genesis 2020, 58, e23396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.D.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosker, T.; Olthof, G.; Vijver, M.G.; Baas, J.; Barmentlo, S.H. Significant Decline of Daphnia Magna Population Biomass Due to Microplastic Exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.-T.; Fueser, H.; Trac, L.N.; Mayer, P.; Traunspurger, W.; Höss, S. Surface-Related Toxicity of Polystyrene Beads to Nematodes and the Role of Food Availability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 1790–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Cai, J.; Sultan, Y.; Fang, H.; Zhang, B.; Ma, J. Effects of Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics on Reproduction, Oxidative Stress and Reproduction and Detoxification-Related Genes in Daphnia Magna. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 254, 109269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Gu, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z. Artificial Light Pollution with Different Wavelengths at Night Interferes with Development, Reproduction, and Antipredator Defenses of Daphnia Magna. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Kwak, K.; Chung, W.-J.; Choi, K. Determination of mRNA Expression of DMRT93B, Vitellogenin, and Cuticle 12 in Daphnia Magna and Their Biomarker Potential for Endocrine Disruption. Ecotoxicology 2011, 20, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).