Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

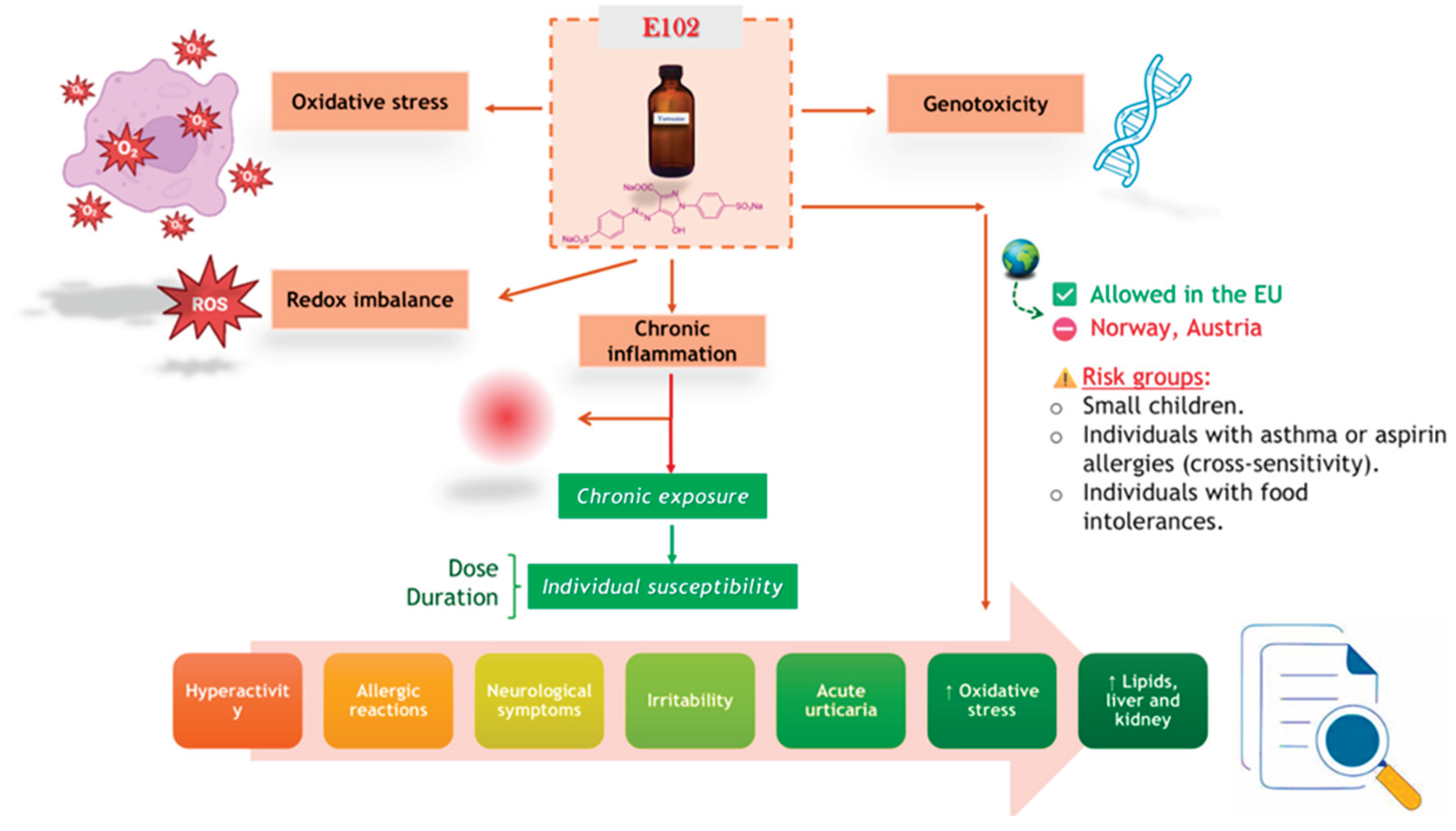

2. Health Implications of Tartrazine Exposure

3. Oxidative Stress Induced by Tartrazine

4. In Vitro Studies on Tartrazine Toxicity

5. Tartrazine Toxicity in Experimental Animal Models

6. Conclusions

7. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rehman, K.; Ashraf, A.; Azam, F.; Hamid Akash, M.S. Effect of Food Azo-Dye Tartrazine on Physiological Functions of Pancreas and Glucose Homeostasis. Turk. J. Biochem. 2019, 44, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leulescu, M.; Rotaru, A.; Pălărie, I.; Moanţă, A.; Cioateră, N.; Popescu, M.; Morîntale, E.; Bubulică, M.V.; Florian, G.; Hărăbor, A.; et al. Tartrazine: Physical, Thermal and Biophysical Properties of the Most Widely Employed Synthetic Yellow Food-Colouring Azo Dye. J Therm Anal Calorim 2018, 134, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.T. Azo Dyes and Human Health: A Review. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev 2016, 34, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroziewicz, Z.M.; Siemiątkowski, R.; Łata, M.; Dowgiert, S.; Sikorska, M.; Kamiński, J.; Więcław, K.; Grabowska, H.; Chruściel, J.; Mąsior, G. Long-Term Health Effects of Artificially Colored Foods in Adults and Children: A Review of Scientific Literature on Attention Deficits, Carcinogenicity, and Allergy Risks. J. Educ. Health Sport 2024, 76, 56522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, P.; Shetti, P.P.; Paranjape, R.; Shetti, P.P. Techniques for Detection and Measurement of Tartrazine in Food Products 2008 to 2022: A Review. J Chem Health Risks 2024, 14, 721–729. [Google Scholar]

- Mehedi, N.; Ainad-Tabet, S.; Mokrane, N.; Addou, S.; Zaoui, C.; Kheroua, O.; Saidi, D. Reproductive Toxicology of Tartrazine (FD and C Yellow No. 5) in Swiss Albino Mice. Am J Pharmacol Toxicol 2009, 4, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barciela, P.; Perez-Vazquez, A.; Prieto, M.A. Azo Dyes in the Food Industry: Features, Classification, Toxicity, Alternatives, and Regulation. Food Chem. Toxicol 2023, 178, 113935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehrei, F. Role of Microorganisms in Biodegradation of Food Additive Azo Dyes: A Review. Afr J Biotechnol 2020, 19, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aali, R.; Yari, A.R.; Ghafuri, Y.; Behnamipour, S. Health Risk Assessment of Synthetic Tartrazine Dye in Some Food Products in Qom Province (Iran). Curr Nutr Food Sci 2024, 20, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/food-additives-contaminants-jecfa-database/Home/Chemical/3885 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Vander Leek, T.K. Food Additives and Reactions: Antioxidants, Benzoates, Parabens, Colorings, Flavorings, Natural Protein-Based Additives. Encycl. Food Allergy 2024, 862–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, B. Influence of Food Additives and Contaminants (Nickel and Chromium) on Hypersensitivity and Other Adverse Health Reactions - A Review. Pol J Food Nutr Sci 2009, 59, 287–294. Available online: https://journal.pan.olsztyn.pl/pdf-98219-30948?filename=30948.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Pestana, S.; Moreira, M.; Olej, B. Safety of Ingestion of Yellow Tartrazine by Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Challenge in 26 Atopic Adults. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2010, 38, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banc, R.; Filip, L.; Cozma-Petruț, A.; Ciobârcă, D.; Miere, D. Yellow and Red Synthetic Food Dyes and Potential Health Hazards: A Mini Review. Bulletin of University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca. Food Science and Technology 2024, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, B.J. The Behaviour of Three Year Olds in Relation to Allergy and Exposure to Artificial Additives. University of Southampton, Doctoral Thesis, 2004. Available online: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/465625/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Tuormaa, T.E. The Adverse Effects of Food Additives on Health: A Review of the Literature with Special Emphasis on Childhood Hyperactivity. J. Orthomol. Med 1994, 9, 225–243. Available online: https://orthomolecular.org/library/jom/1994/articles/1994-v09n04-p225.shtml (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Feketea, G.; Tsabouri, S. Common Food Colorants and Allergic Reactions in Children: Myth or Reality? Food Chem 2017, 230, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.E.; Lofthouse, N.; Hurt, E. Artificial Food Colors and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Symptoms: Conclusions to Dye For. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.M.; Reboredo, F.H.; Lidon, F.C. Food Colour Additives: A Synoptical Overview on Their Chemical Properties, Applications in Food Products and Health Side Effects. Foods 2022, 11, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, K.S.; Rowe, K.J. Synthetic Food Coloring and Behavior: A Dose Response Effect in a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Repeated-Measures Study. J Pediatr 1994, 125, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visweswaran, B. Oxidative Stress by Tartrazine in the Testis of Wistar Rats. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci 2012, 2, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Desoky, G.E.; Wabaidur, S.M.; Alothman, Z.A.; Habila, M.A. Regulatory Role of Nano-Curcumin against Tartrazine-Induced Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis-Related Genes Expression, and Genotoxicity in Rats. Molecules 2020, 25, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Lv, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, Q.; Zou, Y.; Li, X. Tartrazine Exposure Results in Histological Damage, Oxidative Stress, Immune Disorders and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Juvenile Crucian Carp (Carassius Carassius). Aquatic Toxicology 2021, 241, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xu, Y.; Lv, X.; Chang, X.; Ma, X.; Tian, X.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Kong, X. Impacts of an Azo Food Dye Tartrazine Uptake on Intestinal Barrier, Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Response and Intestinal Microbiome in Crucian Carp (Carassius Auratus). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021, 223, 112551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhkim, M.O.; Héraud, F.; Bemrah, N.; Gauchard, F.; Lorino, T.; Lambré, C.; Frémy, J.M.; Poul, J.M. New Con-siderations Regarding the Risk Assessment on Tartrazine. An Update Toxicological Assessment, Intolerance Reactions and Maximum Theoretical Daily Intake in France. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007, 47, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyat, L.; Essawy, A.; Sorour, J.; Soffar, A. Tartrazine Induces Structural and Functional Aberrations and Genotoxic Effects in Vivo. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T. Reproductive and Neurobehavioural Toxicity Study of Tartrazine Administered to Mice in the Diet. Food Chem Toxicol 2006, 44, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelker, L. Oxidative Stress, Free Radicals, and Cellular Damage. Studies in Veterinary Medicine 2011, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaamy, A.M.Z.; Al-Zubiady, N.M.H. Study on Toxic Effect of Tartrazine Pigment on Oxidative Stress in Male Albino Rats. Biochem Cell Arch 2021, 21, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar]

- El-Desoky, G.E.; Abdel-Ghaffar, A.; Al-Othman, Z.A.; Habila, M.A.; Al-Sheikh, Y.A.; Ghneim, H.K.; Giesy, J.P.; Aboul-Soud, M.A.M. Curcumin Protects against Tartrazine-Mediated Oxidative Stress and Hepatotoxicity in Male Rats. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017, 21, 635–645. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28239801/ (accessed on 18 July 2025). [PubMed]

- Ramos-Souza, C.; Nass, P.; Jacob-Lopes, E.; Zepka, L.Q.; Braga, A.R.C.; De Rosso, V.V. Changing Despicable Me: Potential Replacement of Azo Dye Yellow Tartrazine for Pequi Carotenoids Employing Ionic Liquids as High-Performance Extractors. Int. Food Res. J 2023, 174, 113593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amchova, P.; Siska, F.; Ruda-Kucerova, J. Safety of Tartrazine in the Food Industry and Potential Protective Factors. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Fondriest Gentry, A.; Schwartz, R.; Bauman, J. Tartrazine-Containing Drugs. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 1981, 15, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K. Sensitivity to Tartrazine. Br Med J 1982, 285, 1597–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, C.R. Diet and Disease. J. Nutr. Ther. 1988, 226–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, I.L.D.; Bertges, L.C.; Assis, R.V.C. Prolonged Use of the Food Dye Tartrazine (FD&C Yellow N° 5) and Its Effects on the Gastric Mucosa of Wistar Rats. Braz J. Biol 2007, 67, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skypala, I. Other Causes of Food Hypersensitivity. In Food Hypersensitivity: Diagnosing and Managing Food Allergies and Intolerance; 2009; Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781444312119#page=219 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Bush, R.K.; Taylor, S.L. Reactions to Food and Drug Additives. Middleton’s Allergy: Principles and Practice: Eighth Edition 2014, 2–2, 1340–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitkreutz, J.; Tuleu, C. Pediatric and Geriatric Pharmaceutics and Formulatio. Modern Pharmaceutics: Fifth Edition, 2016; 2–2. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/b14445-32/pediatric-geriatric-pharmaceutics-formulation (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Rovina, K.; Siddiquee, S.; Shaarani, S.M. A Review of Extraction and Analytical Methods for the Determination of Tartrazine (E 102) in Foodstuffs. Crit Rev Anal Chem 2017, 47, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezgin, A. Food Additives : Colorants Food Additives : Colorants. In Science Within Food: Up- to - Date Advance s on Research and Educational Ideas. Researchgate 2018, 122, 87–94. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322404775_Food_Additives_Colorants (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Sharma, R.; Bamola, S.; Kumar Verma, S. Effects of Acid Yellow 23 Food Dye on Environment and Its Removal on Various Surfaces-A Mini Review. IRJET 2020, 7, 4550–4573. [Google Scholar]

- Koop, B.L.; Maciel, A.G.; Soares, L.S.; Monteiro, A.R.; Valencia, G.A. Natural Colorants. Natural Additives in Foods. 2022, pp. 87–122. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-17346-2_4 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Athira, N.; Jaya, D.S. Effects of Tartrazine on Growth and Brain Biochemistry of Indian Major Carps on Long-Term Exposure. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res 2022, 6, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, A.A.; Awad Hegazy, A.; Haliem, W.A.; Haliem, R.A.; Mamdouh El-Bestawy, E.; Mohammad, G.; Ali, E. Brief Overview about Tartrazine Effects on Health. Eur. Chem. Bull 2023, 12, 4698–4707. [Google Scholar]

- Pay, R.; Sharrock, A. V.; Elder, R.; Maré, A.; Bracegirdle, J.; Torres, D.; Malone, N.; Vorster, J.; Kelly, L.; Ryan, A.; et al. Preparation, Analysis and Toxicity Characterisation of the Redox Metabolites of the Azo Food Dye Tartrazine. Food Chem Toxicol 2023, 182, 114193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, A.A.; Fawzia, S.E.-S. Toxicological and Safety Assessment of Tartrazine as a Synthetic Food Additive on Health Biomarkers: A Review. Afr J Biotechnol 2018, 17, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, C.; Shen, J.; Yin, H.; An, X.; Jin, H. Effect of Food Azo Dye Tartrazine on Learning and Memory Functions in Mice and Rats, and the Possible Mechanisms Involved. J Food Sci 2011, 76, T125–T129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, D.; Barrett, A.; Cooper, A.; Crumpler, D.; Dalen, L.; Grimshaw, K.; Kitchin, E.; Lok, K.; Porteous, L.; Prince, E.; et al. Food Additives and Hyperactive Behaviour in 3-Year-Old and 8/9-Year-Old Children in the Community: A Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nettis, E.; Colanardi, M.C.; Ferrannini, A.; Tursi, A. Suspected Tartrazine-Induced Acute Urticar-ia/Angioedema Is Only Rarely Reproducible by Oral Rechallenge. Clin Exp Allergy 2003, 33, 1725–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Caldas, L. De; Caldas Marmo, F.; da Costa, P.V.; Viana Jacobson, L.S. Hormesis in Tartrazine Allergic Responses of Atopic Patients: An Overview of Clinical Trials and a Raw Data Revision. Environ Dis 2020, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, B.M.; Araújo, T.M.T.; Ramos, J.A.B.; Pinto, L.C.; Khayat, B.M.; De Oliveira Bahia, M.; Montenegro, R.C.; Burbano, R.M.R.G.; Khayat, A.S. Effects on DNA Repair in Human Lymphocytes Exposed to the Food Dye Tartrazine Yellow. Anticancer Res 2015, 35, 1465–1474. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25750299/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Boussada, M.; Lamine, J.A.; Bini, I.; Abidi, N.; Lasrem, M.; El-Fazaa, S.; El-Golli, N. Assessment of a Sub-Chronic Consumption of Tartrazine (E102) on Sperm and Oxidative Stress Features in Wistar Rat. Int Food Res J 2017, 24, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, K.A.; Abdel Hameid, H.; Abd Elsttar, A.H. Effect of Food Azo Dyes Tartrazine and Carmoisine on Bi-ochemical Parameters Related to Renal, Hepatic Function and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Young Male Rats. Food Chem Toxicol, 2010, 48, 2994–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Golli, N.; Bini-Dhouib, I.; Jrad, A.; Boudali, I.; Nasri, B.; Belhadjhmida, N.; El Fazaa, S. Toxicity Induced after Subchronic Administration of the Synthetic Food Dye Tartrazine in Adult Rats, Role of Oxidative Stress. Recent Adv Biol Med 2016, 02, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinoz, E.; Erdemli, M.E.; Gül, M.; Erdemli, Z.; Gül, S.; Turkoz, Y. Prevention of Toxic Effects of Orally Administered Tartrazine by Crocin in Wistar Rats. Toxicol Environ Chem 2021, 103, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozougwu, J.C. Physiology of the Liver. IJRPB, 2017, 4, 13–24. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/38598619/Physiology_of_the_liver?auto=download (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Kiran, T.R.; Otlu, O.; Karabulut, A.B. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Health and Disease. J. Lab. Med 2023, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosieny, N.A.; Mona, E.; Ahmed, S.M.; Zayed, M. Toxic Effects of Food Azo Dye Tartrazine on the Brain of Young Male Albino Rats: Role of Oxidative Stress. Zagazig J Forensic Med 2020, 19, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wopara, I.; Adebayo, O.G.; Umoren, E.B.; Aduema, W.; Iwueke, A. V.; Etim, O.E.; Pius, E.A.; James, W.B.; Wodo, J. Involvement of Striatal Oxido-Inflammatory, Nitrosative and Decreased Cholinergic Activity in Neurobehavioral Alteration in Adult Rat Model with Oral Co-Exposure to Erythrosine and Tartrazine. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Seeni, M.N.; El Rabey, H.A.; Al-Hamed, A.M.; Zamazami, M.A. Nigella Sativa Oil Protects against Tartrazine Toxicity in Male Rats. Toxicol Rep 2018, 5, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhakim, Y.M.; Moustafa, G.G.; Hashem, M.M.; Ali, H.A.; Abo-EL-Sooud, K.; El-Metwally, A.E. Influence of the Long-Term Exposure to Tartrazine and Chlorophyll on the Fibrogenic Signalling Pathway in Liver and Kidney of Rats: The Expression Patterns of Collagen 1-α, TGFβ-1, Fibronectin, and Caspase-3 Genes. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2019, 26, 12368–12378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velioglu, C.; Erdemli, M.E.; Gul, M.; Erdemli, Z.; Zayman, E.; Bag, H.G.; Altinoz, E. Protective Effect of Crocin on Food Azo Dye Tartrazine-Induced Hepatic Damage by Improving Biochemical Parameters and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Rats. Gen Physiol Biophys 2019, 38, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgayed, S.S. Toxicological and Histopathological Studies on the Effect of Tartrazine in Male Albino Rats. IJABE 2016, 10, 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- Erdemli, Z.; Altinoz, E.; Erdemli, M.E.; Gul, M.; Bag, H.G.; Gul, S. Ameliorative Effects of Crocin on Tartrazine Dye–Induced Pancreatic Adverse Effects: A Biochemical and Histological Study. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021, 28, 2209–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haridevamuthu, B.; Murugan, R.; Seenivasan, B.; Meenatchi, R.; Pachaiappan, R.; Almutairi, B.O.; Arokiyaraj, S.; M. K, K.; Arockiaraj, J. Synthetic Azo-Dye, Tartrazine Induces Neurodevelopmental Toxicity via Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis in Zebrafish Embryos. J Hazard Mater 2024, 461, 132524. [CrossRef]

- Floriano, J.M.; Rosa, E. da; do Amaral, Q.D.F.; Zuravski, L.; Chaves, P.E.E.; Machado, M.M.; De Oliveira, L.F.S. Is Tartrazine Really Safe? In Silico and Ex Vivo Toxicological Studies in Human Leukocytes: A Question of Dose. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2018, 7, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasdaran, A.; Azarpira, N.; Heidari, R.; Nourinejad, S.; Zare, M.; Hamedi, A. Effects of Some Cosmetic Dyes and Pigments on the Proliferation of Human Foreskin Fibroblasts and Cellular Oxidative Stress; Potential Cytotoxicity of Chlorophyllin and Indigo Carmine on Fibroblasts. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022, 21, 3979–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, A.; Pohjanvirta, R. In Vitro Estrogenic, Cytotoxic, and Genotoxic Profiles of the Xenoestrogens 8-Prenylnaringenine, Genistein and Tartrazine. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 27988–27997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haverić, A.; Inajetović, D.; Vareškić, A.; Hadžić, M.; Haverić, S. In vitro Analysis of Tartrazine Genotoxicity and Cytotoxicity. G& A 2017, 1, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, A.; Macharia, J.M.; Szabó, I.; Gerencsér, G.; Molnár, Á.; Raposa, B.L.; Varjas, T. The Impact of Tartrazine on DNA Methylation, Histone Deacetylation, and Genomic Stability in Human Cell Lines. Nutrients 2025, 17, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, V.; Katti, P. Developmental Toxicity Assay for Food Additive Tartrazine Using Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryo Cultures. Int J Toxicol 2018, 37, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.L.; Li, K.; Yan, D.L.; Yang, M.F.; Ma, L.; Xie, L.Z. Toxicity Assessment of 4 Azo Dyes in Zebrafish Embryos. Int J Toxicol 2020, 39, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Ranjan, S.; Yadav, A.; Verma, B.; Malhotra, K.; Madan, M.; Chopra, O.; Jain, S.; Gupta, S.; Joshi, A.; et al. Toxic Effects of Food Colorants Erythrosine and Tartrazine on Zebrafish Embryo Development. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci 2019, 7, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, D.D.; Bich-Ngoc, N.; Paques, C.; Christian, A.; Herkenne, S.; Struman, I.; Muller, M. The Food Dye Tartrazine Disrupts Vascular Formation Both in Zebrafish Larvae and in Human Primary Endothelial Cells. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linskens, A. The Long Term Effects of Tartrazine (FD&C Yellow No. 5) on Learning, Cognitive Flexibility, and Memory of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos into Adulthood. Available online: https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/sites.uwm.edu/dist/8/202/files/2018/06/Linskens_paper_LM_Seymour_2018-1lxiur8.pdf (accessed on 24 Jul 2025).

- Meena, B.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, S. Effects of Sub-Chronic Exposure of the Food Dye Amaranth on the Biochemistry of Swiss Albino Mice (Mus Musculus L.). IJISRT 2017, 21, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, S.; Hossain, M.S.; Neshe, S.A.; Rashid, Md.M.O.; Tohidul Amin, M.; Hussain, Md.S. Tartrazine Induced Changes in Physiological and Biochemical Parameters in Swiss Albino Mice, Mus Musculus. Marmara Pharm J 2017, 21, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.M.; El-Lethey, H.S. The Potential Health Hazard of Tartrazine and Levels of Hyperactivity, Anxiety-Like Symptoms, Depression and Anti-Social Behaviour in Rats. Am. J. Sci 2011, 7, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, J.N.; Muhammad, G.A. Sub-Acute Toxicity Study on Tartrazine in Male Albino Rats. DUJOPAS 2022, 8, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Desoky, G.E.; Wabaidur, S.M.; AlOthman, Z.A.; Habila, M.A. Evaluation of Nano-Curcumin Effects against Tartrazine-Induced Abnormalities in Liver and Kidney Histology and Other Biochemical Parameters. Food Sci Nutr 2022, 10, 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemli, M.E.; Gul, M.; Altinoz, E.; Zayman, E.; Aksungur, Z.; Bag, H.G. The Protective Role of Crocin in Tartrazine Induced Nephrotoxicity in Wistar Rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 96, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iroh, G.; Weli, B.O.; Adele, U.A.; Briggs, O.N.; Waribo, H.A.; Elekima, I. Assessment of Atherogenic Indices and Markers of Cardiac Injury in Albino Rats Orally Administered with Tartrazine Azo Dye. J Adv Med Pharm Sci 2020, 22, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaamy, A.; Merza Hamza, N.; Masikh Zebalah Al-Daamy, A.; Marza Hamza Al-Zubiady, N. Study of The Toxic Effect of Tartrazine Dye on Some Biochemical Parameters in Male Albino Rats. Sci. J. Med. Res. 2020, 4, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Elhakim, Y.M.; Hashem, M.M.; El-Metwally, A.E.; Anwar, A.; Abo-EL-Sooud, K.; Moustafa, G.G.; Ali, H.A. Comparative Haemato-Immunotoxic Impacts of Long-Term Exposure to Tartrazine and Chlorophyll in Rats. Int Immunopharmacol 2018, 63, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, I.; Sevastre, B.; Mireşan, V.; Taulescu, M.; Raducu, C.; Longodor, A.L.; Marchiş, Z.; Mariş, C.S.; Coroian, A. Protective Effect of Blackthorn Fruits (Prunus Spinosa) against Tartrazine Toxicity Development in Albino Wistar Rats. BMC Chem 2019, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himri, I.; Bellahcen, S.; Souna, F.; Belmakki, F.; Aziz, M.; Bnouham, M.; Zoheir, J.; Berkia, Z.; Mekhfi, H.; Saalaoui, E. A 90-Day Oral Toxicity Study of Tartrazine, a Synthetic Food Dye, in Wistar Rats. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2011, 3, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sakhawy, M.A.; Mohamed, D.W.; Ahmed, Y.H. Histological and Immunohistochemical Evaluation of the Effect of Tartrazine on the Cerebellum, Submandibular Glands, and Kidneys of Adult Male Albino Rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019, 26, 9574–9584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd, B.E.; Naby, E.; Shalaby, R.A.; Fouda, F.M.; Ebiya, R.A. Evaluation of biochemical effects of tartrazine and curcumin in male albino rats. World J. Pharm. Res 2022, 11, 1472–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Product examples | References |

| Food products | TZ is widely used to impart an intense yellow color in various food products such as bread, beverages, cereals, peanuts, candies, jellies, chewing gum, flavored chips, creams, ice cream, yogurts, cakes, instant desserts, soups, sauces, jam, flavored rice, and pasta, but due to its potential side effects, there is a growing tendency to replace it with natural pigments like annatto or beta-carotene. |

[2,35,37,40,41,42,43,45] |

| Pharmaceuticals | TZ is used as a coloring excipient in multivitamins, gelatin capsules, tablets, syrups, and pediatric medicines, but in some cases it may cause allergic reactions or asthma in sensitive individuals. | [33,36,38,39,40] |

| Non-food products | TZ is also present in non-food products such as soaps, cosmetics, shampoos, hair conditioners, pastels, crayons, and stamp dyes. It may cause hypersensitivity reactions upon skin contact. | [25,34,44,45] |

| Experimental organism | n= | About species | Dose | Time | Method of administration | Sample | Effect | References |

| Rats |

18 | Young male albino rats (28 days, 60–80 g) | 320 mg/kg tartrazine in 1 ml distilled water, daily | 4 weeks | oral gavage | Brain | ↓ GPx ↑ MDA |

[59] |

| 50 | Wistar male albino rats | 7.5 mg/kg | 90 days | Diets containing dry mass | Liver | ↑ MDA ↓ GSH |

[30] | |

| Serum | ↓ SOD ↓ CAT ↓ GPx |

|||||||

| 24 | Male Wistar rats (10–12 weeks, 180–200 g) | 2, 6, 10 mg/kg (erythrosine + TZ 50:50 mix) | 6 weeks | oral gavage | Brain tissue | ↑ MDA ↓ GSH ↓ CAT ↑ ACHe. |

[60] | |

| 18 | Male albino rats | 10 mg/kg (+3.75 mg/kg sulfanilic acid) | 8 weeks | oral administration | Serum, liver and kidney tissue homogenate | ↑ MDA ↓GSH ↓ SOD ↓ CAT ↓ GR |

[61] | |

| 18 | White albino rats of either sex | Low (10 mg/kg) and high (50 mg/kg) doses | 15 and 30 days | oral administration | Serum | ↓ SOD |

[1] | |

| 30 | Sprague-Dawley male albino rats (150-200 g) | 75 mg/kg | 90 days | Oral administration by orogastric gavage | Hepatic and renal tissue homogenate | ↑ MDA ↓ GSH ↓ SOD ↓ CAT |

[62] | |

| 18 | Male albino rats (10–15 weeks, 190–250 g) | 400 mg/kg | 30 days | oral administration | Serum | ↑ MDA ↓ GSH ↓ SOD ↓ CAT ↓ GPx |

[29] | |

| 40 | Female Wistar albino rats (225–250 g) | 500 mg/kg | 21 days | oral gavage | Tissue homogen ates |

↑ MDA ↑ SOD ↑ TOS ↓ GSH ↓ CAT ↓ TAS |

[63] | |

| 40 | Adult female Wistar rats (225–250 g, 8–10 weeks) | 500 mg/kg | 3 weeks | oral gavage | Tissue homogenates | ↑ MDA ↑ TOS, ↓ GSH ↓ SOD ↓ CAT ↓ TAS |

[56] | |

| 30 | Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (120-150 g) | 200 mg/kg | 60 days | oral administration | Tissue homogenate | ↑ MDA |

[64] | |

| 40 | Female Wistar rats, (225–250 g) | 500 mg/kg | 3 weeks | oral gavage | Tissue homogenate | ↑ MDA ↑ TOS ↓ GSH ↓ TAS ↓ SOD ↓ CAT. |

[65] | |

| 20 | Male Wistar rats, (130 ± 40 g) |

300 mg | 30 days | oral administration | Tissue homogenate | ↑MDA ↑CAT ↑GST |

[55] | |

| 36 | Young male albino rats (60–80 g) | low doses of TZ 15 mg/kg bw | 30 days | oral administration | Liver tissue homogenate | ↑ MDA ↓ CAT ↓ SOD |

[54] | |

| high doses were 500 mg/kg bw | ↑ MDA ↓ CAT ↓ SOD ↓ GSH |

|||||||

| 40 | Sprague–Dawley rats (70 ± 10 g) |

175, 350, and 700 mg/kg bw | 30 days | oral gavage | Brain tissue | ↓GSH ↓SOD ↑MDA |

[48] |

| Cell Type | Concentration Tested | Tests Performed | Key Findings | References |

| Human lymphocytes | 0.25 – 64.0 mM | MTT assay, alkaline comet assay | No cytotoxicity; genotoxic at all doses; partial DNA repair. | [52] |

| Human leukocytes | 5 – 500 μg/mL | Trypan Blue viability, Micronucleus test, Comet assay, Cytogenetics, In silico | No cytotoxicity/mutagenicity; DNA damage at ≥70 μg/mL; supported by in silico models. | [67] |

| Human foreskin fibroblasts | 10, 100, 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 μg/ml for various dyes | MTT assay, ROS, lipid peroxidation, LDH | TZ: no effect; indigo carmine/chlorophyllin cytotoxic at high doses | [68] |

| Yeast assay, MCF-7 breast cancer cells | Not specified (short-term) | Estrogenic activity, LDH release, micronucleus test | 8-PN showed the strongest estrogenic effect, followed by TZ and genistein; all exhibited low cytotoxicity and no genotoxicity. | [69] |

| Human lymphocytes, GR-M melanoma cells | 2.5, 5and 10 mM | Chromosome aberration, CBMN assay, trypan blue test | No genotoxicity in lymphocytes; low cytotoxicity in lymphocytes; high cytotoxicity in melanoma cells | [70] |

| HaCaT | 20 µM, 40 µM și 80 µM | qRT-PCR Alkaline Comet Assay |

Upregulated DNMT and HDAC genes with increased DNA fragmentation, indicating epigenetic and genotoxic effects. | [71] |

| HepG2 | ||||

| A549 |

| Experimental model | n= | Method of administration | Time | Dose | Analysis | Effect | Ref. |

| Zebrafish | |||||||

| Zebrafish embryo |

20/concentration | Exposed to E3 medium with varying TZ concentrations in Petri dishes | 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, 168 hpf |

0, 0.1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 75, 100 mM | Developmental anomalies (heart rate, edema, tail distortion, hatching, mortality) observed via bright field microscopy. | Control embryos hatched normally; ≥10 mM caused early hatching with deformities and ≥40 mM increased mortality. | [72] |

| 25 embryos/well | Embryos exposed in 6-well plates with E3 medium supplemented with TZ | 3-4 h post-fertilization to 4 dpf | 0, 5, 10, 20, 50 g/L | Zebrafish embryo toxicity and vascular defects. | Dose-dependent vascular defects: hemorrhage, edema, small eye, vessel abnormalities. | [75] | |

| 20 | Exposed in E3 medium | 72 hours (hpf) | 5-100 mM (various concentrations) | Developmental and cardiac toxicity parameters | TZ caused dose-dependent drops in survival, hatching, cardiac/yolk sac edema, spinal defects, and heart rate. | [73] | |

| 9 | Exposure via aquatic media | 6 months to a year | 22 μM | Behavioral tests: T-maze test, cognitive flexibility, memory, learning, perseverance, consistency in choices. | Learning, memory, and flexibility impaired; task completion and perseverance reduced. | [76] | |

| 100 | Exposed to varying erythrosine and TZ levels in embryo water. | Up to 10 dpf | Erythrosine: 0.001–0.1%; TZ: 0.01–0.5% | Biochemical and genetic analyses | High TZ (≥0.5%) boosted hatching (55% at 48 hpf, 100% at 72 hpf) and triggered SOD1 expression via OS. | [74] | |

| Mice | |||||||

| KunMing mouse (20 ± 2 g) | 40 | Oral gavage | 30 days | 175–700 mg/kg body mass | Behavioral (Step-through, Morris maze) and biochemical tests | TZ negatively affects learning and memory in mice, increasing escape time and reducing reaction time in tests. | [48] |

| Male Swiss albino mice (4 weeks) | 15 | Oral administration | 72 days | 100 mg/kg | Hematological analyses | Increased red blood cell count, WBC count, and hemoglobin | [77] |

| 200 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | Increased red and WBC counts, hemoglobin, platelet volume, and MCV | |||||

| 200 mg/kg | |||||||

| Swiss albino mice (25-30g) |

15 | Oral administration | 25 days | 200mg/kg | Physiological and biochemical analyses | No effect on cholesterol; increased bilirubin and creatinine | [78] |

| 400 mg/kg | Increased total cholesterol, triglycerides, bilirubin, and creatinine | ||||||

| Rats | |||||||

| Sprague–Dawley rats (70 ± 10 g) |

40 | Oral gavage | 30 days | 175, 350, 700 mg/kg body mass | Behavioral tests: Open-field test. Biochemical analyses |

TZ increases activity and anxiety in rats, also causing histopathological changes in the brain. | [48] |

| Male Wistar rats (40-50 g) | 45 | Dissolved in tap drinking water | 16 weeks | %, 1% (low dose) and 2.5 % (high dose) | Behavioral tests: Open field behaviour test Elevated plus maze test Light-Dark transition task Forced swim test Social interaction test |

The study highlights the harmful effects of TZ on anxiety and depression, highlighting the risks of long-term exposure to food dyes on mental health. | [79] |

| Young male albino rats (28 days old, 60-80g) | 18 | Oral gavage | 4 weeks | 320 mg/kg TZ in 1 ml distilled water, once daily. | Neurobiological and histological analysis: Brains were harvested and analyzed for histological changes. |

TZ has a neurotoxic effect, evidenced by histological changes such as neuronal apoptosis and vascular congestion. | [59] |

| White albino rats of either sex | 18 | Oral administration | 15 and 30 days | Low dose: 10 mg/kg High dose: 50 mg/kg |

Biochemical, hormonal and histological analyses | TZ disrupts glucose balance, damages pancreas, alters endocrine function. Increases glucose, lipase; decreases insulin, Ca, Mg |

[1] |

| Male albino rats | 18 | Oral administration | 8 weeks | 10 mg/kg (+3.75 mg/kg sulfanilic acid) | Biochemical and histological | Caused liver and kidney dysfunction with lesions. Increased cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, VLDL, ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin, creatinine, urea, uric acid. Decreased HDL, total protein. |

[61] |

| Wistar male albino rats | 50 | Diets containing dry mass | 90 days | 7.5 mg/kg | Biochemical and histological analyses | TZ raised lipids, liver enzymes, kidney function. Increased total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, ALT, AST, ALP, LDH. |

[30] |

| Female Wistar albino rats (225–250 g) | 40 | Oral gavage | 21 days | 500 mg/kg | Biochemical analyses and histopathological examinations | Increased AST, ALT, ALP indicating liver damage. | [63] |

| Male albino rats (65–80 g) | 12 | Oral administration | 7 weeks | 7.5 and 75 mg/kg | Biochemical and histopathological analyses | Study showed harmful lipid, biochemical changes and liver-kidney damage. Increased cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, VLDL, ALT, AST, ALP, creatinine, urea, uric acid. |

[80] |

| Male Wistar albino rats (200–250 g) | 40 | Oral administration | 50 days | 7.5 mg/kg | Biochemical and histopathological analyses | TZ impaired liver/kidney, altered histology, lipids, glucose. Increased ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, urea, uric acid, creatinine, protein, cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL; decreased HDL. |

[81] |

| Adult female Wistar rats (225–250 g, 8–10 weeks old) | 40 | Oral gavage | 3 weeks | 500 mg/kg | Biochemical and histopathological analyses | TZ caused degenerative and metaplastic changes in ileum and colon epithelium. | [56] |

| Wistar albino rats (146–153 g) | 20 | Dissolved in 1 ml of distilled water | 30 days | 7.5 mg/kg b.wt. | Biochemical, histological and ultrastructural analyses | TZ raised AST, ALT, ALP, uric acid, urea, creatinine, reduced antioxidants, and caused liver and kidney damage. | [26] |

| Male Wistar rats (10–12 weeks old, 180–200 g) | 24 | Oral gavage | 6 weeks | 2, 6, 10 mg/kg (50:50 erythrosine-TZ) | Behavioral (open field test, forced swimming test, tail suspension test), biochemical and enzymatic analyses | Increased nitrite, TNF-α; worsened anxiety and depression. | [60] |

| Sprague-Dawley male albino rats (150-200 g) | 30 | Oral administration by orogastric gavage | 90 days | 75 mg/kg | Biochemical, genetic, immunohistochemical, histology analyses | Increased AST, ALT, urea, creatinine; liver and kidney damage. | [62] |

| Female Wistar albino rats (225–250 g) | 40 | Oral gavage | 21 days | 500 mg/kg | Biochemical and histopathological analyses | TZ caused kidney glomerular collapse, inflammation, congestion. | [82] |

| Albino rats (~0.2 kg) | 63 | Oral administration | 30 and 60 days | 7.5 mg/kg | Biochemical and histopathological analyses | TZdamages heart, raises nHDL and creatine kinase, increasing cardiovascular risk. | [83] |

| Male rats (10–15 weeks old, 190–250 g) | 18 | Oral administration | 30 days | 400 mg/kg | Biochemical analyses | Increased ALT, AST, ALP, urea, uric acid, creatinine; decreased Na, K, Ca. | [84] |

| Adult male Sprague Dawley albino rats | 30 | Oral administration | 90 days | 1.35 mg/kg | Hematological, immunological, and histopathological analyses | Decreased hemoglobin, RBC, PCV%, platelets; increased WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes. | [85] |

| Female Wistar rats (225–250 g) | 40 | Oral gavage | 3 weeks | 500 mg/kg | Biochemical and histopathological analyses | Increased total cholesterol, glucose, triglycerides, LDL, VLDL; decreased HDL. | [65] |

| Albino Wistar rats | 20 | Oral administration | 7 weeks | 75 mg/250 mL water 100 mg/250 mL water |

Biochemical, hematological and histopathological analyses | TZ damaged liver, kidneys, spleen; no change in cholesterol, triglycerides, ALT. Increased AST, creatinine, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes. |

[86] |

| Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (120–150 g) | 30 | Oral administration | 60 days | 200 mg/kg | Biochemical, histological and physiological analyses | Subchronic TZ affects liver and kidney parameters and induces OS. Increased ALT, AST, urea, total protein. |

[64] |

| Male and female Wistar rats (170–200 g) | 30 | Oral administration | 13 weeks |

5 mg/kg | Hematological and histopathological analyses | no effect | [87] |

|

7.5 mg/kg |

Decreased platelets; increased neutrophils, basophils, and mean platelet volume. | ||||||

| 10 mg/kg | no effect | ||||||

| Adult male albino rats (120–150 g) | 40 | Oral gavage | 30 days | 7.5 mg/kg bw |

Histopathological and Immunohistochemical analyses | TZ causes structural damage in cerebellum, glands, kidneys, with edema, congestion, neuron vacuolization, and cell deformation. | [88] |

| 15 mg/kg bw |

ChatGPT a spus: Edema, dilated perineural spaces, and degenerating Purkinje cells. |

||||||

| 100 mg/kg bw | Severe Purkinje cell degeneration, gray matter vacuolization, edema, nuclear pyknosis, vessel engorgement, increased astrocytes. |

||||||

| Male Wistar rats (130 ± 40 g) | 20 | Oral administration | 30 days | 300 mg | Biochemical and histopathological analyses | Increased transaminases, LDH, creatinine, uric acid, kidney proteins; decreased total protein, albumin, globulin; HDL unchanged. | [55] |

| Young male albino rats (Rattus norvegicus), 60–80 g | 36 | Oral administration | 30 days | Low dose: 15 mg/kg bw | Biochemical analyses | Increased ALT, AST, ALP, total protein, albumin, globulin, creatinine, urea; decreased serum cholesterol. | [54] |

| High dose: 500 mg/kg bw | Increased ALP, total protein, albumin, creatinine, urea | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).